Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

HB31

.M415

TO,oLi—

DEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

ADJUSTMENT

WITH

THE

EURO.

THE

DIFFICULT

CASE OF

PORTUGAL

Olivier

Blanchard

Working

Paper

06-04

February

23,

2006

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science Research Network Paper

Collection at

1

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE IOF

TECHNOLOGY

MAR

2 22006

J

tLIBRARIES

Adjustment

within

the

euro.

The

difficult

case

of

Portugal

Olivier

Blanchard

*February

23,

2006

Abstract

In the second half of the 1990s, the prospect ofentry in the euro led to an

output

boom

and large current account deficits in Portugal. Since then, theboom

hasturned into a slump. Current account deficits are still large,and so are budget deficits. This paper reviews the facts, the likely adjustment intheabsenceofmajorpolicy changes,and examines policy options.

* Ithank JoaoAmador,Miguel Beleza,RicardoCaballero,VitorConstancio, RicardoFaini,

Francesco Franco, FrancescoGiavazzi, Vitor Caspar, RicardoHausmann, RaoulGalambade

Oliveira, Juan FranciscoJimeno, Abel Mateus, FernandoTeixeirados Santos,and Sergio Re-belofordiscussionsandcomments. IthankLionel Fontagne,PedroPortugal, andtheresearch

departmentattheBankofPortugal,fordataandother information. Iespecially thankMarta Abreu for herhelp throughoutthis project.

The

Portugueseeconomy

is in serious trouble: Productivitygrowth

is anemic.Growth

is very low.The

budget

deficit is large.The

current account deficit isvery large.

The

purpose

of this paper is to analyze the options available to Portuguesepolicy

makers

at this point.To

do

so however, thepaper

first returns to the past, thenexamines

thelikely adjustment processinthe absenceofmajor pohcy

changes,

and

finally turns to policy options.Section 1 reviews the past.

To

understand the situation today, onemust

go back at least to thesecond half ofthe 1990s. Triggeredby

thecommitment

by

Portugal to join the euro, a sharp drop in interest rates

and

expectations offaster

growth both

led toa decrease in privatesavingand

an increaseininvest-ment.

The

resultwas

highoutput growth, decreasingunemployment,

increasingwages,

and

fast increasing current account deficits.The

futurehowever

turned disappointing. Productivitygrowth went from

bad

to worse.The

investmentboom

came

toanend,and,with disappointedexpecta-tions, privatesaving increased. Fiscal deficits partlyreplaced private dissaving,

but not

by enough

to avoid a slump. Overvaluation, the result ofearlier pres-sureon

wages

during theboom,

imphed

that current account deficitsremained

large.

This is

where

Portugal is today. In the absence of policy changes, themost

hkelyscenario isoneof competitive disinflation, a period ofsustained high

un-employment

until competitiveness has been reestablished, the current accountdeficit

and

unemployment

arereduced.This process is analyzed in Section 2. Itis a process fraught with dangers,

both economic and

political,and one

whichcan easily derail. It

makes

itimperativeto thinkabout

what

policycan do.The

options are basically two.

The

firstand

obviouslymost

attractive one is to achieve a sustained increasein productivity growth,

and

make

sure it is not fully reflected inwage

growth

until

unemployment

and

thecurrent accountdeficitsarereduced.Given

thelowlevel of

income

per capitain Portugal relative to the topEU

countries, gettingcloser to the frontier

would

seem

achievable. Section3 focusesonwhich

reformsand

institutional changes aremost

likely to succeed.The

second is lowernominal

wage

growth. It is obviously less attractive thanachieving the required increase in competitiveness without a long period of

unemployment.

The

main

issue is that, in the currentenvironment

of already lowwage

inflation both in Portugaland

the rest of theEU,

such a strategy, if it is towork

fast enough,would

require a large decrease in thenominal

wage. Section 4 focuseson whether

and

how

it can be achieved.Section 5 concludes. In short, in the absence of policy changes, the adjustment

islikely tobe long

and

painful. Itcanbe

made

shorter,and

lesspainful. Higher productivitygrowth and

lownominal

wage

growth

arenot mutually exclusive,and

the best policy is probably tocombine

both. Fiscalpohcy

also has animportant

roleto play. Deficitreductionisrequired,but itspaceand

itscontentsmay

be

linked to reformsand wage

moderation.From

boom

to

slump,

and

current

account

deficitsFigure 1.

Unemployment

rateand

currentaccount

deficitPortugal, 1995-2007

CL

Q

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

—

Unemploymentrate—

CurrentaccountdeficitSource:

OECD

Economic Outlook

December

2005.The mimbers

for 2006and

2007

areOECD

forecasts.Figure 1 puts the current Portuguese

economic

situation insome

historicalaccount deficit (as aratio of

GDP)

since 1995.Two

periods clearlycome

out:Prom

1995 to 2001, a steady decrease inunemployment

and

a rapidlygrowingcurrent account deficit; since 2001, a steady increase in

unemployment, and

acontinuingcurrentaccount deficit,withthe forecastsbeingfor

more

ofthesame

until at least 2007.^

Start with the

boom.

It is clear thatits proximate cause oftheboom

was

par-ticipationintheERM

and

inthe constructionofthe euro.'^With

thereductionofinflation, the elimination ofcountryrisk,

and

access to theeurobond

market, Portuguesenominal

interestrates declinedfrom

16%

in 1992to4%

in2001; over thesame

period, real interest ratesdechned from

6%

toroughly0%.

Combined

with expectations that participation in the eurowould

lead to fasterconver-gence

and

thus fastergrowth

for Portugal, the resultwas

an increase inboth

consumption

and

investment.Household

saving dropped, investmentincreased.The

actualbudget

deficitdecreased abit.But

discretionaryfiscalpohcy was

ex-pansionary:

Prom

1995 to 2001, the cycHcally adjustedprimary

deficit—

which

adjusts for the effects oflower interest ratesand output growth

—

increasedby

roughly

4%.

The

resultwas

high output growth,and

a steady decrease inunemployment.

(Basicnumbers

for 1995 to 2001,and

for 2001 on, are given in Tables 1and

2 respectively. I decided to use

numbers

from theOECD

Economic

outlook database rather than nationalnumbers

to faciUtate comparisons with othercountries.)

With

lowunemployment, nominal wage growth was

substantially higher than productivity growth, leading togrowth

in unit labor costs higherthan in the rest of the euro area (an area

which

accounts for roughly70%

ofPortuguese trade).

The

result ofhigh outputgrowth

and

decreasingcompeti-tiveness (I shalldefine competitivenessas the inverse of unit labor costs relative to those in the euro area)

was

a steady increase in the current account deficit,from

close to0%

in 1995 tomore

than10%

in 2000.1. Methodological changes in the Labor Force Survey imply a break in theunemployment

series in 1998. It is estimated that, under the pre-1998 definition, the unemployment rate

would be roughly 1% higher than it istoday.

2. Formoredetails,seeforexampleConstancio[8], Fagan and Caspar[11]or Blanchard and

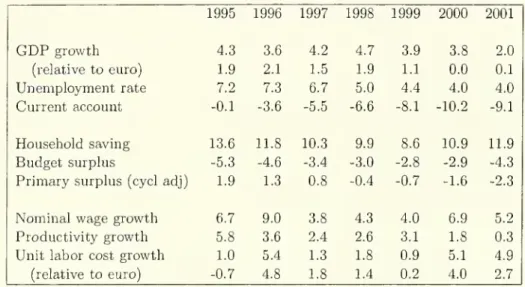

Table 1.

Macroeconomic

evolutions, 1995-2001 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001GDP

growth

4.3 3.6 4.2 4.7 3.9 3.8 2.0 (relative to euro) 1.9 2.1 1.5 1.9 1.1 0.0 0.1Unemployment

rate 7.2 7.3 6.7 5.0 4.4 4.0 4.0 Current account -0.1 -3.6 -5.5 -6.6 -8.1 -10.2 -9.1Household

saving 13.6 11.8 10.3 9.9 8.6 10.9 11.9Budget

surplus -5.3 -4.6 -3.4 -3.0 -2.8 -2.9 -4,3Primary

surplus (cycl adj) 1.9 1.3 0.8 -0.4 -0.7 -1.6 -2.3Nominal

wage

growth

6,7 9.0 3.8 4.3 4.0 6.9 5.2Productivity

growth

5.8 3.6 2.4 2.6 3.1 1.8 0,3Unit labor cost

growth

1.0 5.4 1.3 1.8 0.9 5.1 4.9 (relative toeuro) -0.7 4.8 1.8 1.4 0.2 4.0 2.7(Source:

OECD

Economic

Outlook

Database

December

2005. "Currentac-count":ratio of the currentaccount balance to

GDP.

"Householdsaving": ratio to disposableincome."Budget

surplus"and

"Cyclicallyadjustedprimary

sur-plus": ratios toGDP.

"Nominal

wage growth"

and

"laborproductivity" areforthe businesssector).

Should

thegovernment

haveaimed

to limit the size of theboom

and

the sizeof the current account deficit through tighter fiscal policy?

With

hindsight, theanswer is surelyyes. But, at the time, the answer

was

less obvious;• First, initial

unemployment

was

clearly above the naturalrate.While

anunemployment

rate of7.3%

in 1996 isnot highbyEU

standards, itwas

ahistoricallyhighrateforPortugal.Thus,

some

growth

inexcess ofnormal

growth

was

justified.By

theend

of the 1990s however,unemployment

had

clearlybecome

lower than the natural rate,and

excessgrowth

was

no

longer justified.• Second,

some

current account deficitwas

also clearly justified.A

lowerreal rate ofinterest

and

expectations of faster convergenceboth

justifyhigher private spending,be it

consumption and

investment.And

indeed, theboom

was

primarily drivenby

private spending. This does notby

itselfimply that the

government

should have just stoodby

(thiswould

impliesthatthe largecurrentaccountdeficitscould be seenaslargely be-nign, the manifestation ofthe advantagesof tighter financial integration into theeuro.'^

Whether

or not, givenexpectations atthe time, policyshould havebeen

tighteris

now

anacademic

question—

although animportant

and open academic

ques-tion.'' Starting in the early 2000s, the future turned out to be disappointing...

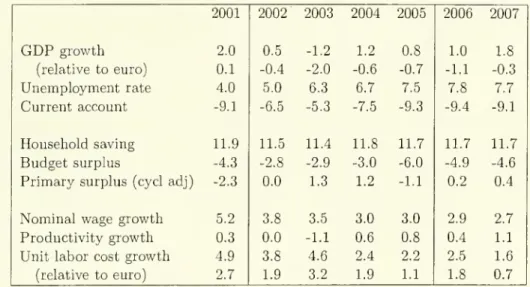

Table 2.

Actual

and

projectedmacroeconomic

evolutions, 2001-20072001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

GDP

growth

2,0 0.5 -1.2 1.2 0.8 1.0 1.8 (relative to euro) 0.1 -0.4 -2.0 -0.6 -0.7 -1.1 -0.3Unemployment

rate 4.0 5.0 6.3 6.7 7.5 7.8 7.7Current

account -9.1 -6.5 -5.3 -7.5 -9.3 -9.4 -9.1Household

saving 11.9 11.5 11.4 11.8 11.7 11.7 11.7Budget

surplus -4.3 -2.8 -2.9 -3.0 -6.0 -4.9 -4.6Primary

surplus (cycl adj) -2.3 0.0 1.3 1.2 -1.1 0.2 0.4Nominal

wage growth

5.2 3.8 3.5 3.0 3.0 2.9 2.7Productivity

growth

0.3 0.0 -1.1 0.6 0.8 0.4 1.1Unit

labor costgrowth

4.9 3.8 4.6 2.4 2.2 2.5 1.6 (relative to euro) 2.7 1.9 3.2 1.9 1.1 1.8 0.7Source

and

definitions:same

as Table 1.The

year 2001 is repeated forconve-nience.

The numbers

for2006

and 2007

areOECD

forecasts.3. Thiswasindeed theinterpretationGiavazziandIgavein[3].Ourdiscussant,PierreOhvier

Gourinchas [13], was moreworried aboutthe required adjustment. Hewasright.

4. Take a standard intertemporal open economy model, with tradables and non-tradables,

and a fixed exchange rate. Assume away all imperfections. Then, a decrease in the world

interest rate, or an increase in productivity growth will lead to an increase in consumption and investment, and so to a current account deficit. Iflabor supply is inelastic, the wage,

and with it the price of non-tradables will increase. Later on, as the country pays interest

on accumulated debt, thewagewill decrease, and withit thepriceofnon-tradables.Thereis

no reason for thegovernment to intervene. (A formalmodel along theselines ispresented by

Faganand Gaspar(ll]). Suppose howeverthatwagesadjust slowlytolabormarketconditions.

Then, the increase in demand will lead not only to a current accountdeficit, butalso to an

increase in output above its natural level. Suppose thegovernment can use fiscal policy to affect demand (because offinite horizons byprivate agents forexample). Should it maintain

outputatthe naturallevel,andinthe process eliminate the(partly desirable) currentaccount

deficit? Orshould it allowfor someincrease inoutputand somecurrentaccountdeficit? The

• Higher productivity

growth

did not materialize. Instead, it nearlyvan-ished, averaging

0.1%

per yearfrom

2001 to 2005.The

investmentboom

came

toanend.And,

becauseofhighaccumulated

debtand

worsefuture prospects, household saving increased.•

The

increase in private savingwas

partly oiTsetby

increasing public dissaving.The

actual deficit steadily increased, reaching6%

in 2005.After an

improvement

inthe early 2000s, the cychcallyadjustedprimary

deficit again turned negative in 2005.

The

ratio of debt toGDP,

using the Maastricht definition, reached66%

at theend

of2005.•

Lower growth and

thus lowerimport

demand

should have led to a de-crease in the current account deficit.But

thiswas

largely offsetby

a continuing increase in relative labor costs. True,nominal

wage

growth

decreased; butwhatever

competitive advantage thiswould

have givenPortugal

was

more

thanoffsetby

the decline in productivity growth.As

a result, unit labor costs have increasedby

another8%

since 2001. Be-cause Portugal is largely a price taker for its exports, export prices have not increasedverymuch,

ifat all; the imphcation is that profitability innon-tradables has dramatically decreased.^

•

The

effects ofovervaluationfrom

theboom

werecompounded

by

com-position effects in exports.A

large proportion of Portuguese exportsis in "low tech" goods, roughly

60%

compared

to an average of30%

for the euro area,

goods where

competition withemerging

economies isstrongest.^ Also, remittances have steadily decreased,

from

3%

in 1996(down from

10%

in the1980s...) to1.5%

today. Thissuggeststhat, intheabsenceofthe

boom-induced

overvaluation, the currentaccount balancewould

still have deteriorated.Lower consumption and

investmentdemand

have led to an output slump.Growth

was

negativein 2003,and

has averaged0.3%

since 2001.The

unemploy-5. Another logical possibility is that wages have increased much lessin the tradablesector

than forthe economyas awhole. Computations fromQuadros de Pessoalby PedroPortugal suggest howeverthatthishas notbeen thecase, atleast upto 2002 (thelatestdateforwhich

theinformation isavailable.) Bargained andactualwages havegrown atthesameratein the

textileor clothingsectors for exampleas intheprivate sector asa whole.

6. These numberscomefrom [17]. Formore onexport composition,see alsoCabral[6]. Some

othercomputationssuggest howeveralessdire picture. Forexample,computations byLionel

Fontagne ofthecorrelation ofexport shareswith China's export shares, usingdisaggregated

(HS6 level) sectoraldata, suggestthat thiscorrelationisnot higher for Portugalthanit isfor

Germany, reflectingthefactthat competitionwithemerging economiesinmediumtechgoods

ment

rate has increased back to 7.5%.As

a result of increases inrelative unitlabor costs

on

top of adversestructural trends, the current account deficit hassteadily increased, reaching

9.3%

in 2005.And

it increasingly reflects a largebudget

deficit, rather than low privatesaving or high investment.2

What

happens

next?

What

happens

next, absentmajor

policy changesand major

surprises'^, isa period of "competitive disinflation": a period of sustained high

unemploy-ment, leadingtolower

nominal

wage growth

until relative unit labor costshavedecreased, competitiveness has improved, the current account deficit has de-creased,

and

demand

and

output haverecovered.The

process isfamiliarfrom

exchangerate-based stabilizations (see forexample

Rebelo

and

Vegh

[15]),and from

the competitive disinflationmany

countrieswent through

inEurope

in the 1980sand

1990s in order to join the euro.The

evidence is that it is typically a longand

painful process. In our study of thecompetitive disinflation process in Prance [4], Pierre Alain

Muet

and

Icon-cluded that, starting

from

equal inflation athome

and

abroad, a20%

gap

incompetitiveness,

and

anunemployment

rateinitially2%

above thenaturalrate,it took four years to reduce the competitiveness

gap

to12%

(andby

then, theunerriployment

gap

was

still 1.2%), six years toreduceit to8%

(withan

unem-ployment

gap

still equal to0.8%).Are

there reasons to bemore

optimistic for Portugal, to think that, in theabsence of

major

policy changes, theunemployment

cost needed toreestablishcompetitiveness

would

belower?The

answer is probably not.One

can think ofthe eff'ects ofunemployment

on wages

and

thus oncompeti-tiveness as

depending

primarilyon two

elements (I shall keep theargument

inthe text informal.

A

formalmodel

is given inBox

1):•

The

first is reaiwage

rigidities, i.e. the effect ofunemployment

on therate ofchangeofrealwages.

The

weakertheeffect ofunemployment,

the slower the decrease inwages

for a givenunemployment

gap,and

thusthe

more

totalunemployment

isneeded to achieve a givenimprovement

in competitiveness.

Isthere

any

reasontobelieve thatrealwages

aremore

flexibleinPortugal than theywere

in Francein the 1980sand

1990s? I read theeconometric evidence as giving a negative answer.Based

on

the sharp adjustment in realwages

inthe early 1980s,some

researchershaveconcludedthatwages

were quite flexible in Portugal.

But

themain

cause of the adjustmentseems

to havebeen

thedevaluationswhich

took place atthetime,ratherthan a strong responseof

wages

to labormarket

conditions (see Diasetal [9]). Coefficients estimated over the

more

recent past suggestHmited

real

wage

flexibility.As

theeconometric evidenceismurky,

it isuseful tolookatthewage

bar-gaining institutional setup directly.

Such

a look suggests that, aswages

are typically above those set in sectoral bargaining, there is substantialroom

for firms to decrease wages, that there iswhat

Portugaland

Car-dosocall a substantial

"wage

cushion" (see [7].) It appearshowever

thatthis

wage

cushion hasbeen

partly usedby

firms in recent years; thissuggests that flexibihty is indeed smaller

today

than itwas

in the early 2000s.The

second isnominal

wage

rigidities. This expression is usedhowever

to describetwo

very different aspects ofwage

setting.The

first is the presence of lags in the response ofnominal wages

to prices—

and

of prices tonominal

wages.The

longer the lags, the slower theadjustment

ofwages

for a givenunemployment

gap, thus themore

unemployment

isneeded

toachieve a givenimprovement

incompetitive-ness. Empirical evidence suggests that, even if each lag is

smaU,

their joint presence can substantially increase theunemployment

cost of theadjustment.

The

second ishowever

asrelevant ormore

relevant today. Itcomes

fromthe fact that workers

may

be reluctant to acceptnominal

wage

declines.Indeed, in Portugal today, the labor law forbids "unjustified

wage

de-creases"and

in practice rules out decreases innominal

wages

foreco-nomic

reasons.The

evidenceon

wage

changesshows

indeed thepresenceofsubstantial

nominal

rigidity of this typein Portugal (see forexample

the histograms of

wage

changesby

year in [2],Box

2-5,and

Dickens etal [10] for an international comparison).

In a world of low inflation, this second constraint, if present, sharply

example

thatnominal

wages

areincreasing at2%

inthe euro area,and

that productivity

growth

in tradablesis thesame

in Portugaland

in thetherestoftheeuroarea.

Then,

themost which

canbe

achieved,i.e.nom-inal

wage

growth

of0%

onlyleads toan improvement

ofcompetitivenessof

2%

ayear.To

summarize,

real rigidities limit the speed ofadjustmentofthewage

tolabormarket

conditions.Nominal

rigidities further slowdown

and

may

even stopthe adjustment.

The

higher real ornominal

rigidities, the larger theamount

ofunemployment

needed

to reestablish competitiveness.What

can bedone

to alleviate theunemployment

cost of adjustment?One way

is to achieve higher productivity growth. Higher productivitygrowth

is clearly desirable

on

itsown

as it implies ahigher rate ofgrowth

ofGDP

percapita.

And

it willimprove

competitiveness so long as it is not fully reflected inwage

growth. This points to reforms in the goodsand

financial markets.Even

withdramaticreforms, productivitygrowth

isunhkelyhowever

to increase overnight.Thus, anotherand

potentiallymuch

fasterway

to reestablish compet-itiveness is to decreasenominal

wage growth

—

indeed, given the circumstances,to achieve a decrease in

nominal wages

—

without relying onunemployment

todo

thejob over time.Are

there otherways?

The

answer is basically no.Outmigration, the

main

mechanism

through which U.S. states return to lowunemployment

after an adverse shock, is not an option, at least on thescale inwhich

itwould

have to take place to solve theproblem

inPortugal.Fiscalpolicycouldinprinciplebe used toincreaseaggregate

demand

and

reduceunemployment.

This howeverwould

come

atthe cost of an even larger currentaccount deficit, and,

by

decreasingunemployment

and

thedownward

pressureon

wages,would

slowdown

or even stop theimprovement

in competitiveness.It

would

thusimply

largerand

longer lasting current account deficits. Thus, even leaving aside the facts that the ratio of public debt toGDP

is already highand

would

begetting higher, thiswould

onlypostpone

themacroeconomic

adjustment, not solve it. 1 shall later argue that fiscal policy can help as part

ofapolicy package.

The

pointmade

here is that,by

itself, itcannot solveboth

the competitivenessand

theunemployment

problems.In this context, let

me

takeup

briefly a proposition that hasappeared

insome

pohcy

discussions, the proposition that afiscal consolidation could, inthe cur-rent context, be expansionaryand

perhaps evenimprove

competitiveness.While

there are indeed circumstances inwhich

a fiscal consolidation can increasede-mand

in the short run,Ido

notbelieve that thisis the casefor Portugal today.The main

channelthrough

which

fiscal consolidation can increasedemand

inthe short run is

by

allowing for a dramatic reduction in interest rates. Thiswould

not be the case for Portugal, as thenominal

interest rate isdetermined

fortheeuro areaasawhole,

and

thereis,forthetime being, noriskpremium

on Portuguese bonds. Thus, whiledeficitreduction isneeded, itwould

be unwisetoexpectit to lead,

by

itself, to higherdemand

and

lowerunemployment.

For thesame

reason, itwould be

unwise to expect deficit reduction to lead to aboom

ininvestment,

and through

capitalaccumulation, to a substantialimprovement

in competitiveness.

Box.

Wage

and

pricedynamics

Consider a small country which is part of a

common

currency area (the euroarea),

and which produces and consumes

tradablesand

non-tradables.Assume

thewage

equation isgiven by:Aw

=

EAp

+

EAa

—

(3{u—

u)where

Ap =

aApjM

+

(1—

q)Ap7-Aa

=

aAaj\j -I- (1—

a)Aa7'

wliere

w

is the log of thenominal

wage, soAw

is the rate ofchange

of thenominal

wages;p

is the log of theconsumption

price deflator (itselfa weighted average ofthe price ofnan

tradablesand

the price of tradables); a is log pro-ductivitygrowth

(a weighted average of productivitygrowth

innon

tradablesand

tradable production);u and u

are the actualand

naturalunemployment

rates respectively;

E

denotes an expectation. (Amore

general,and

theoreti-callymore

appealing, formulation,would

assume

thatwages

follow an error correctionmechanism,

in which casean

error-correctionterm

would

appear

onthe right. Introducing such a

term

would

complicate the presentation but notchange

substantially the pointsmade

below.)The

equation therefore states thatwage

inflationdepends

on expected priceinflation, expected productivity growth,

and

theunemployment

gap, the devi-ation oftheunemployment

ratefrom

the actualrate.Assume

thathome

and

foreign tradables are perfect substitutes, so the rate ofchange

oftradables pricesis equal to the rate ofeurowage

inflationminus

the rate ofeuro productivitygrowth

(euro areavariables aredenoted byasterisks):Apr = Apf

=

Aw*

-

Aa^

Assume

that thenon-tradablesectorproduces under

constant returns tolabor,so the priceofnon-tradablesisgiven by:

Apiv

=

Aw

—

Aa/v

Finallydefine competitiveness as z

=

px

—

w +

ar, thepriceminus

unit laborcost in tradables, or equivalently z

=

w*

—

a^

—

w

+

ar, the inverseofrelativeunit labor costs.

The

question:How

much

unemployment

isneeded

to achievea given

improvement

in competitiveness?Assume

first that expectations are equal to actual values. In this case, theequations

above

yield:Az

=

-^

(u-

u) (1)1

—

a

The

change

incompetitivenessdepends

onlyon theunemployment

gap. It isin-dependent

ofthe evolution of productivityin tradablesand

non-tradables.The

coefficient (3 captures real

wage

rigidities.The

lower thatcoefficient, the larger theunemployment

needed

to achieve a givenimprovement

in competitiveness.Now

introducenominal

rigidities (oftype 1), i.e. lags in the response ofwages

toprices.

Maintain

for themoment

theassumption

that expected productivitygrowth

isequal to actualproductivity growth,and assume

both to be constantover time.

But assume

now

that expected inflation is equal to lagged inflation:EAp

=

Ap(-l)

In thiscase, the equations

above

yield:Az

=

aAzi-l)

-l3{u-u)

Compare

this equation witli the equation obtained absentnominal

rigidities.The

effect of a givenunemployment

gap

on competitiveness isnow

slower.This in turn implies that

more unemployment

isneeded

to achieve a givenimprovement

in competitiveness.Finally consider the effects of changes in productivity growth.

To

the extent that such changes are anticipated, equation (1)shows

they haveno

effect oncompetitiveness.

So

we must

lookat theeffectsofunanticipatedchanges. Definevi\!

=

Aapj—

EAa^,

vt

= Aar

—

EAar

and

v=

avj\r+

(1—

a)vT, so v isunanticipated aggregate productivity growth.

Assume,

for simplicity, thatexpectedinflationisequal toactual inBation. Then,the equations

above

imply:Az

=

[u—

u)+

1

-Q

For agiven

unemployment

gap, an unanticipatedincreaseinproductivityleadstoan increase in competitiveness. Thisin turn implies that less

unemployment

is

needed

to achieve agivenimprovement

in competitiveness.An

important implication is thatit doesnotmatter

whether

the unanticipatedincrease in overall productivity

growth

comes from

the tradables or thenon-tradablessector.

What

matters isv, notits composition.Vt and

v^

work however

in verydifferent ways, vt directlyimproves

competi-tiveness, but, fora given

unemployment

rate, hasno

furthereffecton

thewage,visi instead decreases the price of

non

tradables, which in turn decreases thewage, therefore

improving

competitiveness in the tradables sector. This alsoindicates

when

the equivalence breaksdown.

Ifwage

inflation isalready equaito zero for example,

and wage

inflation cannot be negative (the second type ofnominal wage

rigidity described in the text), productivitygrowth

innon-tradables sector

wiU

not befullyreflected inwage

inBation,and

thereforewiU

have

no

effect on competitiveness.3

Increasing productivity

growth

GDP

percapita(atPPP

prices) inPortugalis$16,4000.Thisisonly52%

ofGDP

per capita inthe top five

EU

members

($31,500). Given Portugal'smembership

in

both

theEU

and

the euro,onemight

think that this48%

gap would

be easytoreduce, that Portugal could achieve substantially higherproductivity

growth

than it currently does.*

A

2003McKinsey

study of productivity in Portugal [14] looks at the sources of this gap.Of

the48%

gap, it attributes16%

to "structural" (geographicand

other) factors,and

the rest,32%

to "non-structural" factorswhich

can becorrected

through

appropriate policies. If Portugal were able tomake

up

forexample

half ofthe non-structuralgap

in 10 years, thiswould

translate in anincrease in productivity

growth

of2.5%

a year.^Such

an increase in productivitygrowth

would

clearly increase thegrowth

rate ofGDP

percapita. Itwould

decreasethe current accountdeficitonlytotheex-tent thatit

improved

competitivenessinthe tradablessector, tothe extent thatwage

growth

was

less than productivitygrowth

intradables.Thismight

requirewage

agreements

limiting realwage

growth, but these are easier to achieve ifproductivity

growth

is high in the first place.Under

these conditions,antici-pations of higher income,

and

higher profitability could lead to an increase inconsumption

and

investmentdemand

and

output,and

thus reduceunemploy-ment

faster than under the adjustment path described earlier. In effect, thiswould

lookverymuch

like the scenariomany

had

inmind

inthe 1990s.Produc-tivity

growth

decreased rather than increased however,and

that scenario didnot play out. This time, ifproductivity

growth

actually increased, it would. Letme

look at the scenario inmore

detail,and

takeup two

issues.•

Would

itbebetterforthe increase inproductivitygrowth

totake placeinthetradablesector orin thenon-tradablesector?

The

perhapssurprisinganswer

is that, to afirst approximation, it does not matter.The

rccison is the following (the underlying algebra is given inBox

1):At

a givenwage and

unemployment

rate, higher productivity in trad-ables indeed translates directly into higher competitiveness. Ifthe price8. The evidence is that convergence is typically faster within

common

currency areas. Seeforexample Frankeland Rose [12].

9. Forcomparison's sake: Therate ofproductivitygrowth in Polandover thelast ten years

has been close to 4.8%. Poland's

PPP

GDP

percapita, about$10,000, isstill however lowerthan Portugal's.

oftradables is given

by

the worldmarket

however, this hasno

furthereffect on the price level,

and

thusno

further effect on the wage. Higher productivity in non-tradableson

the otherhand

leads to a lower price of non-tradables,which

leads (for a given realconsumption

wage) to alower wage. Thus, it improves competitiveness through the lower

wage

ratherthan

directlythrough higher productivityin tradables.The

argument

alsoshows

the limits of this equivalence result: If, forexample,

nominal

wage growth

is already equal to zeroand

cannot benegative, then,

improvements

in productivity in non-tradables haveno

effect on thewage,

and

thus no effecton

competitiveness.Still, even with this caveat, this equivalence is an important result. Im-proving productivityin the tradables sector,

where

largecompanies

aremore

likelytobe

involved,and

competition likelyto bestronger,may

be

much

harder than improving productivityinnon-tradables.Put

another way,improving

zoningregulations or redefiningthe hcensingprocessand

the division of tasksbetween

localand

national authorities,may

be asimportant

—

and

easier to achieve—

than helping createnew

high-techexporting firms.

Isitessentialfor Portugaltoimprove productivityin thehigh tech sector

and

increaseits share ofhigh-tech exports?The

answer is, I suspect,no. First,Portugal does not have an obvious comparative advantageinhigh-tech:

The

levelsofeducationand

R&D

spendingareboth

lowrelative toother

members

of theEU.

Labor market

institutions, in particular thehighlevel of

employment

protection, imply low labor mobility,and

thus alimited ability to reallocate resources as the high-tech frontiermoves

on.A

more

obviouscomparative advantage,and

onewhich

islikely toremain

for a long time, is in tourism.

Many

Portuguese balk at the idea of the Florida model, the scenario inwhich Europeans

come

to retire inPortugal.-^^

The

experience ofSpain suggests that this can be amajor

source ofprivate transfers (as retirees transfer funds

from

their countryoforigin).^^

The

"Floridamodel",asopposed

to traditional tourism, also10. Francesco Giavazzi has suggestedcallingitthe"Tuscanymodel", which isrelevant as well

and sounds more attractive. The relevant point is that higher income retirees bring larger transfers.

11. Thereare 180,000 foreignersoverthe ageof 65 inSpain; itissafe toassume mostofthem

are retirees. IfPortugal attractedthesame numberofretirees, and their pensionswere equal

comes

withderiveddemand

formany

products,forexample

sophisticatedhealth care. Facilitatingsuch a

development

through infrastructureand

coordination

seems

more

promisingthan startinganew

high-tech sectorfrom

scratch.What

canactuallybe done

toimprove

productivity?Inanswer

tothisquestion,onetypicallyhearsa longlitany ofreforms,

from

reformoftheeducation system,to

improvement

in thejudicial system, to deregulation ofthegoods

market, tochanges in labor

market

laws.How

does one gobeyond

these generalities?One

approach

is to useeconometrics to relategrowth

to anumber

ofmeasures

of institutions for abroad

cross section of countries, to seehow

Portugal fares,and

how

improvements

in the differentmeasures

would

increase Portuguese growth. Thisis theapproach

followed forexample by

Tavares [18], basedon

themeasures

of institutions developedby

Shleifer et al (forexample

[16])and by

others.

Another,

complementary,

approach

is to focuson

specific sectors, tomeasure

theproductivity

gap

with other countries,and

to try to identify theproximateand

deeper sources ofthis gap. This iswhat

the 2003McKinsey

study did. Itfocused

on

seven specific sectors. Letme

present its findings fortwo

ofthem,residentialconstruction,

and

tourism.'^I believe theygive a

good

sense ofwhat

reformsmay

be most

useful.•

The

study found

that productivity in residential constructionwas

only38%

ofthelevelinthebenchmark

country,in thiscasetheUnited

States.The

main

proximate causes behind this62%

gap were the lack ofstan-dardization in design

and

construction—

forexample

underutilization of prefabricated materials—

which

accounted for22%

(onethird ofthe gap);poor

projectdesign—

forexample

highlevelsofrework

—

which

accountedfor another

15%;

inefficient execution—

forexample

underutilization oflabor

and machinery

—

which

accounted for another10%.

What

were the deeper, institutional, causes?The

study concluded thatit was, first

and

foremost, informality, allowing small inefficient firmstosurvive,

and

preventing economies of scale from being exploited; zon-ingand

licensing rules, hmiting thenumber

oflarge scale developmentsonaverageto incomeper capitainPortugal, thiswould representprivate transfers of close to

2%

ofPortuguese GDP.12. The other sectors in the studyare food retail, retail banking, telecommunications, road

freight, and theautomotivesector. '

(15%

in Portugal versus70%

in the Netherlands for example)and

the associated economies ofscale were also important.•

The

study found that productivity in tourism (hotels)was

only44%

of thelevel in thebenchmark

country, in this casePrance.The main

proximate causesbehind

this56%

gap

were low occupationrates

(42%

versus59%

for France),and

a limited role of hotel chains(10-25%

versus34%

forPrance).The

deeper, institutional, causes,the study concluded, werelaborregula-tion,

making

itdifficultforhotelstoadjust toseasonalityand

shift-basedworking

schedules,and

zoningand

licensinglaws, limiting the scope forlarge resort formats,

and

limiting the role ofinternational chains.These

areonly case studies.But

theymake

a convincing case that reducingin-formality,

improving

zoningand

hcensing requirements, adaptingemployment

protection laws to allow seasonal industriesto use labor

more

efficiently,would

go

some

way

towards increasing productivity in both non-tradablesand

trad-ables.

Reforms

along theselines, rather than a high-tech plan,may

yield larger results in terms ofproductivitygrowth

and improved

competitiveness.Inthisparticular context,

how

essential are reforms in the labormarket?

There

are clear signs that the Portuguese labormarket

is dysfunctional:At

a given rate ofunemployment,

average duration ofunemployment

isverylong,evenby

Western

European

standards,and

flows inand

out ofunemployment

are verylow.

The main

cause appearsto be the high degree ofemployment

protection.To

the extent that productivitygrowth

depends

in large part on reallocation,thissuggests that reducing

employment

protection could be one of the keys to higher productivity growth.The

studyPedro

Portugaland

I did ofjoband

worker flows in Portugal [5] suggests

however

amore

nuanced

conclusion.We

found that job flows, that is the degree of reallocation of labor across estab-lishments, was, surprisingly, similar to that ofthe United States.

Worker

flowshowever, including

movements

inand

outofunemployment,

were unusuallylow.One

interpretation of these findingsis thatemployment

protectionmay

notim-pede

jobreallocation asmuch

asonemight

haveguessed. Itmay

however reducethe quality of

matches between

firmsand

workers,and

thusimply

alossofpro-ductivity, ifnotofproductivitygrowth.

My

(tentative) conclusionis that, while reform ofemployment

protection is highly desirableon

othergrounds

(such asa decrease in the average duration of

unemployment, and

better matching), itmay

notbe

essential for the issueat hand,namely

higher productivity growth.4

Decreasing

wages

Increasing productivity

growth

isnot easyand wiU

nothappen

overnight.'-^The

otherway

to reestablish competitiveness is to decreasenominal

wage

growth,or even, in thecurrent context ofalready low Portuguese

and

European wage

inflation, to actuallydecrease

nominal

wages.The

important

point hereis that,given productivity, thisdecrease in

wages

isneeded

toimprove

competitiveness.The

issueiswhether

itis achievedover timethrough

unemployment

orifunem-ployment

can be avoided,and

thesame

decrease achieved through a voluntaryand

coordinated reduction ofwages by

workers.The

traditionalway

to achieve such a reduction is through a devaluation. Ifsuccessful, a devaluation leads to an increasein thepriceoftradables,given the

nominal

wage

and

the price ofnon

tradables.Put

another way, it decreases thereal

consumption

wage

and

the relative price of non-tradables,and

increasesprofitability in.the tradables sector. Ifworkers can

be

convinced to accept thedecrease in the

consumption

wage,and

thus not to increasenominal wages

inresponse to the increase in the price of tradables, the devaluation is successful

and

competitiveness is improved. Thiswas

forexample

the case in Italy in1992,

where

awage

freeze,which had been

agreed to with unions before thedevaluation ofthe lira,

was

maintained after thedevaluation—

a devaluation inexcess of

30%.

Given

Portugal'smembership

inthe euro, devaluation is notan option however (and I believe getting unilaterally out of the eurowould

have disruption costswhich would

farexceedany

gainincompetitivenesswhich might

be obtainedin this way).The

same

resultcanbe

achieved however, at leaston

paper, through a decrease in thenominal

wage

and

the price ofnon-tradables, while the price of tradables remains the same. This clearly achieves thesame

decrease in thereal

consumption

wage,and

thesame

increasein therelative price oftradables.13. In the second half of 2003, a large drop in inflation in Chile was partly attributed to

reforms in the distribution sector [1] (through their effects on profit margins as much as on productivity). Iftrue, thiswould be aniceexampleofhowstructuralreformscan have rapid

macroeconomic effects. The evidence is however not overwhelmingthat this was the main

factor behindthe decrease in inflation.

The

question is:Can

it actually beimplemented?

Letme

take anumber

ofissues

and

objections:• Decreases in

nominal

wage

run into both psychologicaland

legalprob-lems. (Indeed, asindicated above, suchdecreeises

would

probablyrequire a modification ofexisting labor laws to be implemented).Could

there-quired

change

in relative pricesbe

achievedthrough

taxes rather thanthrough

wages?

The

answer

isyes,but only toaUmited

extent. Consider a balancedbud-get shift

from

payroll taxes toVAT.

Exporting

firms will benefit:They

pay

lessin payroll taxes,and

aresubject to the foreign, unchanged,VAT

rate.

Firms

selling tothe domesticmarket

will lose:They

pay

less inpay-rolltaxes, but

pay on

netmore

inVAT.

Such

ashift willtherefore achievean increase in competitiveness, without a

change

innominal

wages. Inpractice, the scope for such a

measure

to reestabhsh competitiveness islimited.

The

VAT

ratewas

recently increased in Portugalfrom

19 to21%.

The

increase required toimprove

competitiveness by, say20%

orso,

would

require ashiftin taxationand an

increase inVAT

ratesmuch

larger than isrealistic or feasible within the

EU.

•

Could

anominal wage

freeze—

which

hasbeen

used in other countrieson

occasion,and

is psychologically easier forworkers to accept—

ratherthan an actual decrease in

nominal

wages, be sufficient?The

answer

isthat, in the currentenvironment

oflow eurowage

inflationand poor

productivitygrowth

in Portugal, itwould

not achievemuch.

Take

theOECD

forecasts for 2006:Wage

growth

and

labor productivitygrowth

inthebusinesssectorfortheeuro areaareforecasttobe1.7%

and

1.0%

respectively, implying anincrease in unitlaborcostsof0.7%.Wage

and

productivitygrowth

in the business sector in Portugal are forecastto be

2.9% and

0A%

respectively, implying an increase in unit labor costs of 2.5%, thus a further increase in labor costs vis-a-vis the euroarea of 1.8%.

A

nominal

wage

freezewould

imply instead a decrease in relative labor costs of 1.1%.At

that rate, itwould

takeverymany

yearsto reestablish competitiveness in Portugal.

•

Can

workers be induced to accept a decrease innominal wages?

The

answermay

well be no.Unions

may

disagree with the diagnosis,and

thus disagree with the need to reestablish competitiveness.They

may

hope

for faster productivity growth.Many

years ofhighunemployment

may

beneeded

to convinceworkers oftheneed

for adjustment.There

are nevertheless three important points tomake

here.The

firstis, for given productivitygrowth, the adjustment of

wages

has tocome

sooner or later if competitiveness is to be improved; the question iswhether

theunemployment

costs can be reduced.The

second is thatpart of the

unemployment

costcomes from nominal

rigidities, not realrigidities. Coordinating

wage

adjustmentsand

thusreducing the role ofnominal

rigidities can decrease theunemployment

cost of theadjust-ment.

The

thirdis thatany

decrease innominal

wages

implies a smallerdecrease in real (consumption) wages.

Assume

tradable pricesremain

unchanged,

thatnon-tradableprices aresetby

amarkup

on

wage

costs,and

the share oftradables is roughly50%.

Then

a decrease innominal

wages

of20%

leads to a decrease inconsumption wages

of only 10%.The

reason is that the price ofnon-tradables decreases inproportion towages. Thisis still asubstantial decrease in real wages, but onlyhalf of the

nominal

decrease.Even

if workers accept thetwo

arguments

above, theymay

stillworry

that things

may

not turn out as expected.There

are at leasttwo

legiti-mate

worries:The

first is that firmsinthenon-tradable sectormay

increasetheir mar-gins rather than decrease their prices in line with labor costs, or simply that the passthroughfrom wages

to non-tradable pricesmay

be

slow,implying a larger decrease in real

wages

forsome

timethan

impliedby

the

computation

above."^'^An

apparentsolutionto thiswould

betocoordinatethedecreaseinwages

and

non-tradable pricessimultaneously. But,justlike pricecontrols, thisishkelyto create

major

distortions:The

reasonisthatproducersofnon-tradables use non-tradables as inputs inproduction,

and do

this in differentproportions. This

means

thatnon-tradable priceswilland

should declineindifferent proportions.

A

potentiahy better solution is an ex-post con-tingentadjustment

ofnominal wages

for inflation, ifinflation turns outto be higher (or, in this case, deflation turns out to be smaller) than expected.

The

secondworry

is that, even if competitiveness is improved, thede-14. In manycountries, theshift totheeuro hasbeenperceived byconsumers, rightorwrong,

to have led toan increasein marginsby firms. The samefears arelikely to be presenthere.

creasein real

wages

may

leadtoa largedecreaseinconsumption

demand,

and

thus to a decrease in outputand

tomore

unemployment,

at least in the short run.A

potential solution heremay

be acommitment

to usefiscal policy to sustain

demand

if needed. While, as discussed earher, afiscal expansion

would on

itsown

be both dangerous

and

counterproduc-tive, it can, as part ofa package of

wage

and

fiscalcommitments,

help deliverimprovements

in competitivenessand unemployment.

The

nominal

interest rate is setby

theECB

ineuros.To

the extent thatnominal

wage

decreases lead toanticipated deflation forsome

time, theywill lead to large ex-ante real interest rates,

which

will affectdemand

and output

adversely.This is an important difference with

what

happens

when

theadjust-ment

ismade

through a devaluation. In that case, thenominal

interest rate, post-devaluation, typicallydecreases—

as the probabihtyofanother devaluation has decreased.At

thesame

time, inflationand

expectedin-flation typically increase, reflecting the higher price ofimports.

On

bothcounts, the real interest rate is Ukely to decrease, not increa.se. Here,

because the adjustment is

made

through a decrease inwages

and

non-tradable prices, the effect goes the other way.This raises the question of whether,

on

those grounds, it is better tohave a large

nominal

wage

decrease at the start, or instead to achieve smaller rates ofwage

decrease over anumber

of years.The

answer isthat this channel strengthens the

argument

for a large early nominalwage

decrease.Take

theextreme

casewhere

thenominal

wage

decreasewere

unanticipated,and

the price of non-tradables did adjust towages

without lags. In that case, the deflation

would

be fully unanticipated,and

therewould

be no effect on ex-ante real rates. Neither of these twoassumptions

is hkely tobe

met, sothat there will, inany

case, besome

anticipated deflation.But

theargument

remains:The

more

front-loaded theadjustment, thelarger the unanticipated portionofthedeflation,the smaller the effecton

real interest rates.5

Conclusions

I started

by

arguing that Portugal faced an unusually tougheconomic

chal-lenge: low growth, low productivity growth, highunemployment,

large fiscaland

current account deficits.I then

examined

various policy clioices,from

reforms increasing productivity growth, to coordinated decreasesinnominal

wages,and

the use offiscalpolicyin this context. I

want

toend

on amore

positive note.There

is a large scopefor productivityincreases inPortugal,

and

aset ofreformswhich

couldachievethem.

A

decrease innominal wages

sounds exotic, but is thesame

in essenceas a successful devaluation. If it can be achieved, it can substantially reduce

the

unemployment

cost of the adjustment. FiscalpoUcy

can also help.While

deficits

must

be reduced,temporary

fiscal expansion could bepart ofan overallpackage, facilitating theadjustmentofwages.

The

challengeis there.But

so are the toolsneeded

tomeet

it.References

[1]

Banco

Central de Chile.Monetary

policy report.September

2004. [2]Banco

de Portugal.Annual

report. 2004.[3] Olivier

Blanchard

and

Francesco Giavazzi. Current account deficitsin theEuro

area:The

end

of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle? BrookingsPapers

onEconomic

Activity, 2:147-209, 2002.[4] Ohvier

Blanchard and

Pierre AlainMuet.

Pi'ance.Economic

Policy, pages12-56, April 1993.

[5] Olivier

Blanchard

and Pedro

Portugal.What

hidesbehind

anunemploy-ment

rate.Comparing

Portugueseand

U.S.unemployment.

American

Eco-nomic

Review, 91(l):187-207,March

2001.[6] Sonia Cabral.

Recent

evolution of Portuguese exportmarket

shares inthe

European

Union.Banco

de PortugalEconomic

Bulletin, pages 79-91,December

2004.[7]

Ana

Cardoso

and Pedro

Portugal. Contractualwages

and

thewage

cushionunder

different bargaining settings. Journal ofLabor

Economics, 2005.[8] Vi'tor Constancio.

European

monetary

integrationand

the Portuguesecase.

The

new

EU

member

states;Convergence

and

stability,October

2005. Carsten Detken, Vitor Caspar,and

Gilles Noblet, eds,ECB.

[9] Francisco Dias,

Paulo

Esteves,and

Ricardo Felix. Revisiting theNAIRU

estimates for the Portuguese economy.

Banco

de PortugalEconomic

Bul-letin, pages 39-48,

June

2004.[10] William Dickens, Lorenz Goette, Erica Groshen, Steinar Holden, Julian

Messina,

Mark

Schweitzer, JarkkoTurunen,

and

MelanieWard.

The

in-teraction oflabor

markets

and

inflation: Analysis ofmicro-datafrom

the internationalwage

flexibility project. 2005.mimeo ECB.

[11] Gabriel

Fagan and

Vitor Caspar. Adjusting to the euro area:Some

issuesinspired

by

the Portuguese experience.August

2005.mimeo. Banco

de Portugaland

ECB.

[12] Jeffrey Frankel

and

Andrew

Rose.An

estimate ofcommon

currencies ontrade

and

income. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2):437-466,May

2002.[13] Pierre Olivier Gourinchas.

Comments

on "current account deficits in theEuro

area:The

end

of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle?". BrookingsPapers

on

Economic

Activity, 2, 2002.[14]

McKinsey

Global Institute. Portugal 2010. Increasingproductivitygrowth

inPortugal.

McKinsey

Institute,November

2003. Lisbon.[15] Sergio

Rebelo

and

Carlos Vegh. Real effects ofexchange-based stabiliza-tion;An

analysis ofcompeting

theories.NBER

Macroeconomics

Annual, pages 125-174, 1995.Ben

Bernanke and

Juho

Rotemberg

(eds),MIT

Press,Cambridge.

[16]

Andrei

Shleifer, RafaelLa

Porta, FlorencioLopez

de Silanes,and Robert

Vishny.

Law

and

finance. Journal ofPoliticalEconomy,

106:1113-1155,1998.

[17]

Task

force oftheMonetary

PolicyCommittee

oftheEuropean

System

ofCentral Banks. Competitiveness

and

the exportperformance

oftheeuroarea.

June

2005. Occasional paper series,ECB.

[18] JoseTavares. Institutions

and economic growth

inPortugal:A

quantitativeexploration.

Portuguese

Economic

Journal, 3:49-79, 2004.MIT LIBRARIES