Desire thinking as a confounder in the relationship between

mindfulness and craving: Evidence from a cross-cultural validation of the

Desire Thinking Questionnaire

Nadia Chakroun-Baggioni a,b*, Maya Corman a,b, Marcantonio M. Spadac, Gabriele Casellic,d,e,

Fabien Gierski f,g

a Université Clermont Auvergne, Université Blaise Pascal, Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive, BP 10448, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France

b CNRS, UMR 6024, LAPSCO, F-63037 Clermont-Ferrand, France

c Division of Psychology, School of Applied Sciences, London South Bank University, London, United Kingdom

d Studi Cognitivi, Milano, Italy

e Sigmund Freud University, Milano, Italy

f C2S Laboratory (EA 6291), Reims Champagne-Ardenne University, Reims, France g Department of Psychiatry, Reims University Hospital, Reims, France

* Corresponding author at: Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive (LAPSCO), CNRS, UMR 6024, Université Clermont Auvergne, Université Blaise Pascal, 34 avenue Carnot, 63037, Clermont-Ferrand, France. E-mail address: nadia.chakroun@univ-bpclermont.fr (N. Chakroun-Baggioni).

Highlights

• The structure of the Desire Thinking Questionnaire is confirmed in a French sample. • Desire thinking is a confounder in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. • Interrupting desire thinking may be linked to a reduction of craving.

Abstract

Desire thinking and mindfulness have been associated with craving. The aim of the present study was to validate the French version of the Desire Thinking Questionnaire (DTQ) and to investigate the relationship between mindfulness, desire thinking and craving among a sample of university students. Four hundred and ninety six university students completed the DTQ and measures of mindfulness, craving and alcohol use. Results from confirmatory factor analyses showed that the two-factor structure proposed in the original DTQ exhibited suitable goodness-of-fit statistics. The DTQ also demonstrated good internal reliability, temporal stability and predictive validity. A set of linear regressions revealed that desire thinking had a confounding effect in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. The confounding role of desire thinking in the relationship between mindfulness and craving suggests that interrupting desire thinking may be a viable clinical option aimed at reducing craving.

Keywords: Confounding effect; desire thinking; French translation of the Desire Thinking

1. Introduction

Craving refers to the urgency to seek out and achieve a target, or practice an activity, in order to reach its desired effects (Marlatt, 1987). Craving can cause both physical and psychological suffering and has long been identified as an important contributor to behavioral loss of control (Addolorato et al., 2005). Indeed, craving is considered as one of the main symptoms, and therefore treatment targets, in addictive behaviors (e.g. O'Malley et al., 2002; Paille et al., 1995).

In the metacognitive model of addictive behaviours (Spada and Wells, 2005, 2006; Spada et al., 2009, 2013; Spada et al., 2015) it is argued that the duration, frequency and intensity of craving is dependent on the combination of automatic (conditioned) and voluntary cognitive processes. According to this model a variety of external and internal triggers may activate automatic associations that contain information about a desired target or activity (e.g. its positive consequences or a felt sense of deprivation) inducing craving. What makes craving escalate is a cognitive process termed ‘desire thinking’.

Desire thinking has been characterized by Caselli and Spada (2010; 2011; 2013; 2015; 2016) as a voluntary form of perseverative thinking which involves the elaboration of a desired target (an activity, object or state) at both verbal and imaginal levels. The imaginal component of desire thinking, termed imaginal prefiguration, refers to the allocation of attention to target-related information and to the tendency to anticipate positive imagery or positive target related memories. The verbal component of desire thinking, termed verbal perseveration, refers to prolonged self-talk about reasons for engaging in target-related activities and their achievement. Caselli and Spada argue that in the short term desire thinking helps to manage craving by shifting attention away from this experience and onto the elaboration of the desired target. However, in the medium to longer term, desire thinking brings to an escalation of craving as the desired target is perseveratively imagined but not

achieved. This, in turn, leads to the desired target being perceived as an increasingly viable route to attain relief from escalating distress.

Research supports the view that thinking about a desired target is closely linked to levels of craving (Green et al., 2000; Tiffany and Drobes, 1990) and may induce physiological changes similar to those occurring in direct experience (Bywaters et al., 2004; Witvliet and Vrana, 1995). Evidence has also emerged that desire thinking facets are active during episodes of craving in alcohol abuse (Caselli and Spada, 2010). In addition, desire thinking has been found to: (1) have a significant effect, in experimental conditions, on craving for alcohol use in both community and clinical samples (Caselli et al., 2013; Caselli et al., 2017); (2) predict, cross-sectionally, craving in alcohol abusers independently from level of alcohol use (Caselli and Spada, 2011); (3) predict, longitudinally, binge drinking in a community sample (Martino et al., 2017); and (4) vary proportionally across the continuum of drinking behaviour controlling for gender, age, negative affect and craving (Caselli et al., 2012a; Caselli et al., 2012b). Finally, a test on the possible structural overlap between desire thinking and craving measures has shown that craving-related items load on a different factor compared to desire thinking factors, sustaining only a moderate correlation between these two constructs (Caselli and Spada, 2011).

Mindfulness consists of awareness of the immediate experience, non-judgmental attention to the full experience of internal and external phenomena, moment by moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Research indicates that dispositional mindfulness, characterized by nonreactive awareness and acceptance, may allow individuals to tolerate, rather than avoid or deny, craving through an attitude of nonjudgment and openness towards this experience (Baer et al., 2006; Garland et al., 2010). Managing craving through mindfulness-based strategies has been demonstrated in studies investigating craving related to substance use (Bowen et al.,

2009; Witkiewitz et al., 2013) and food consumption (Alberts et al., 2010; Alberts et al., 2012; Forman et al., 2007).

Desire thinking and mindfulness can be considered as cognitive processes with differing foci with respect to their relationship to craving. Desire thinking is characterized by future oriented elaboration of a desired target in response to craving and therefore is believed to foster craving. Mindfulness, on the other hand, is centered on the acceptance of craving in the present moment and is believed to bring to its extinction. A key criticism of the mindfulness approach is that it does not explicitly conceptualize the possible inhibitory role of perseverative thinking (e.g. rumination, worry and desire thinking) in enacting a mindful stance (Wells, 2000). Indeed, according to the metacognitive therapy perspective on psychopathology (Wells, 2000) a mindfulness stance should be potentiated with ‘detachment’ so as to produce ‘detached mindfulness’. Detachment would involve the purposive commitment to not activating perseverative thinking styles, such as desire thinking, in response to a given trigger.

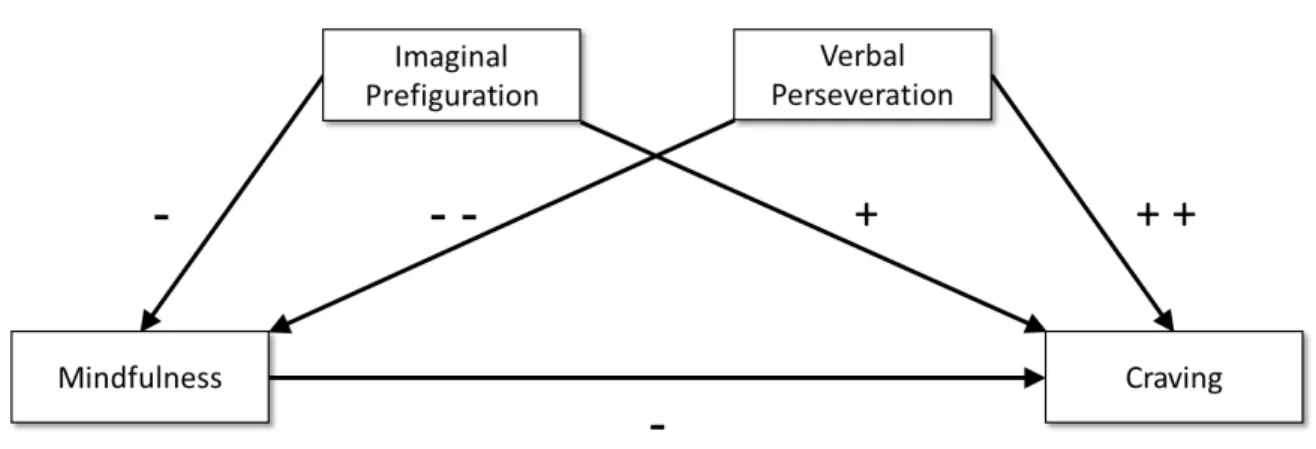

A key question that arises, therefore, is whether mindfulness alone is sufficient in reducing craving or whether its effect on craving may be inhibited (confounded) by the competitive cognitive process of desire thinking. If this were the case it is plausible to assume that the effect of mindfulness on craving would be confounded partially, or entirely, by desire thinking.

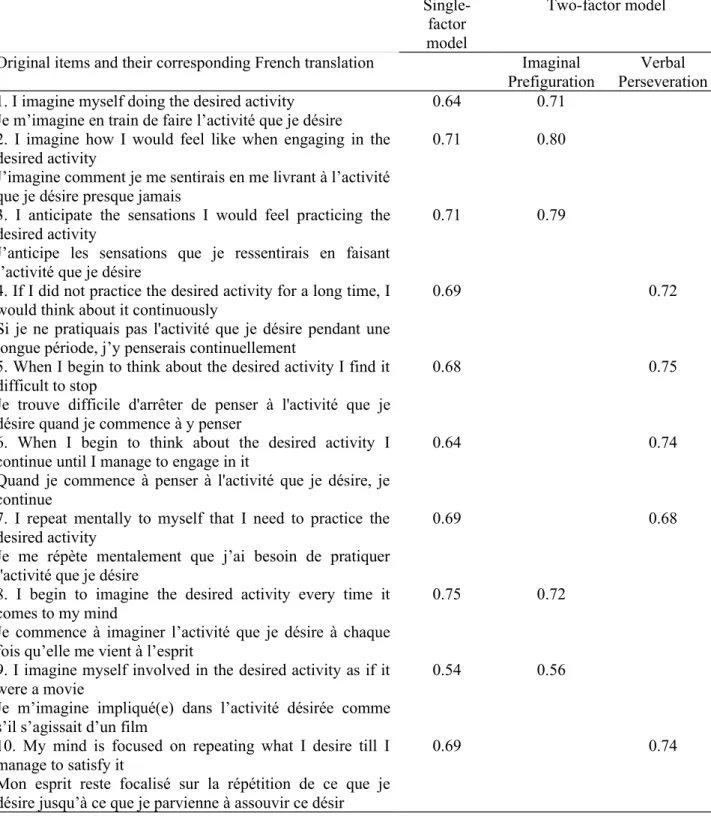

The aims of the present study were twofold. First, we wanted to validate a French translation of the Desire Thinking Questionnaire (DTQ; Caselli and Spada, 2011). Second, we wanted to investigate the associations between mindfulness, desire thinking and craving and test a model in which desire thinking had a confounding effect in the relationship between mindfulness and craving (see Figure 1). We thus hypothesized that: (1) mindfulness would be negatively correlated with craving; (2) desire thinking would be negatively correlated with

mindfulness; (3) desire thinking would be positively correlated with craving; and (4) desire thinking would be a confounder in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. The order of imaginal prefiguration and verbal perseveration was determined on the basis of the conceptual model of the relationship between desire thinking and craving (Caselli and Spada, 2015). In this model imaginal prefiguration represents a more distal predictor of craving that is partially mediated by the activation of verbal perseveration (Caselli and Spada, 2015; Martino et al., 2017). This assumes that decision-making processes and mental planning about target achievement (verbal perseveration) should have a stronger impact on craving than the multi-sensory elaboration of target-related information (imaginal prefiguration).

***Insert Figure 1 about here*** 2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

Undergraduate and graduate students from the University of Clermont-Ferrand, France, were invited to completed a survey on alcohol use. The recruitment information email outlined the purpose of the study (‘To investigate the relationship between thinking style and craving in alcohol users’) and reminded participants that they were under no obligation to participate and that all data provided would be anonymous. All participants provided online informed consent. No compensation was given.

We began by filtering-out participants who were abstainers (n = 116). Then we retained only those who fully-completed the survey (n = 457). Finally, multivariate outliers on the DTQ (n = 21) were discarded by computing Malahanobis distance (χ2 p value < 0.001).

The remaining sample consisted of 436 participants (277 females) with a mean age of 19.14 years (SD = 1.30; range = 18-26).

In order to establish test–retest stability, 69 participants (58 females), with a mean age of 20.0 years (SD = 1.69; range = 18-27) were recruited. They completed twice (with an interval of 6 weeks) the DTQ and provided socio-demographic details.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Desire Thinking Questionnaire (DTQ; Caselli and Spada, 2011)

The DTQ consists of two factors of five items each measuring components of desire thinking. The first factor deals with the perseveration of verbal thoughts about desire-related content and experience (verbal perseveration). The second factor assesses the tendency to prefigure images about desire-related content and experience (imaginal prefiguration). Participants were asked to rate, using a Likert-type scale, the intensity of their desire thinking for alcohol use in the last week. Higher scores on both factors and on the total score indicate higher levels of desire thinking. The Cronbach’s alphas of the original version were 0.83 for the total score and 0.78 for both factors.

2.2.2. Intensity of craving

Participants were asked to rate, using a Likert-type scale, the intensity of their craving for alcohol use in the previous week (from 0 = no desire to 10 = extreme desire).

2.2.3. Alcohol use and pattern of consumption

We used the French version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 1992), which consists of 10 questions regarding recent alcohol use, alcohol dependence symptoms and alcohol-related problems. The summary score ranges from 0, indicating no presence of problem drinking behavior, to 40 indicating marked levels of problem drinking behavior and alcohol dependence. The Cronbach’s alpha for the final sample was 0.79.

A modified version of the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (Mehrabian and Russel, 1978; Townshend and Duka, 2002) was used to establish the weekly level of alcohol use in units of

alcohol and a binge drinking score. This score was calculated on the basis of the information provided on speed of drinking (mean number of drinks per hour in a drinking session), the number of times drinking had occurred in the previous 6 months, and the percentage of drinking sessions that led to becoming drunk.

2.2.4. Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006)

The FFMQ is a 39-item questionnaire which assesses the following facets of mindfulness: observation of experience corresponding to the ability to observe experience, acting with awareness corresponding to the tendency to pay attention to one’s actions, non-judging of experience and non-reactivity to experience corresponding respectively to the capacity to accept thoughts and feelings without judgment or reaction, and describing with words corresponding to the ability to describe internal states. Participants were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale how the statements were true (1 = rarely true to 5 = very often or always true). The Cronbach’s alpha for the final sample was 0.83 (with 0.77 for non-reactivity; 0.79 for observation of experience; 0.86 for describing and acting with awareness and 0.88 for non-judgment).

2.3. Translation of the scale

The DTQ was translated into French in accordance with an internationally recommended procedure (Brislin, 1986). First, two French psychologists produced a French translation of the original English version of the DTQ (Caselli and Spada, 2011). The French translation was then translated back into English by a bilingual assistant professor blind to the original version. A comparison of the back-translation with the original English version of the DTQ revealed only minor discrepancies. The final version was then submitted to university students who reported no difficulty in understanding and completing the questionnaire.

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analysis were conducted in the R environment (R Core Team, 2014) using Psych (Revelle, 2015) and Lavaan packages (version 0.5-17; Rosseel, 2012). Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis analyses, as well as the Shapiro-Wilk’s test revealed that normality assumption of the data was not met. Analyses were therefore conducted with statistical analysis tools for non-normally distributed data.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were computed using a maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and a Satorra-Bentler (SB) scaled test statistic (Satorra and Bentler, 2010), which are robust to violations of multivariate normality. Factor loadings were examined using Comrey and Lee’s (1992) recommendations (i.e .> 0.71 = excellent, >0.63 = very good, > 0.55 = good, > 0.45 = fair and > 0.32 = poor). The overall goodness-of-fit of the DTQ was evaluated using the SB scaled χ2, the SB scaled χ2/degree of freedom (df) ratio, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with 90% confidence intervals, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Confirmatory factor analyses were performed in accordance with the procedure and criteria described in detail by Kline (2011). Conventional cut-offs for fitting indices were as follows: χ2/df <5 = good (Hooper et al., 2008); SRMR < 0.05 = good, between 0.05 and 0.10 = acceptable fit (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003); RMSEA<0.05 = good, between 0.05 and 0.08 = acceptable (Browne and Cudeck, 1992); CFI ≥ 0.90 = acceptable, although ideally ≥ 0.95 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Modification indices were also explored in order to identify parameter misfit.

Internal consistency was assessed using omega coefficients (Bentler, 2009), whereas test-retest reliability was assessed by using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; with its 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) among samples of students who responded twice to the questionnaires. Internal consistency values greater than 0.80 are considered as acceptable

(Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994), while ICC values were examined using the Chichetti (1994; cited in Hallgren, 2012) recommendations (i.e. >0.74 = excellent, > 0.60 = good, > 0.40 = fair).

To explore the links between mindfulness, desire thinking (imaginal prefiguration and verbal perseveration) and craving, we computed Spearman’s correlation coefficients and tested models using a set of linear regressions using the bootstrap technique with 1000 samples (MacKinnon et al., 2000). We adopted the 10% in change-in-estimate rule of thumb as a criterion for a confounding effect (Lee and Burstyn, 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

We tested the two-factor structure that was originally proposed by Caselli and Spada (2011). Results revealed adequate goodness of fit values: SB scaled χ2(34)= 150.60, p<0.001,

SB scaled χ2/df=4.43; SRMR=0.05; RMSEA=0.09 (90% IC: 0.07–0.10); CFI=0.94. Examination of the modification indices suggested that item 8 covaried with both factors. Accordingly, goodness of fit values for this model showed an increase: SB scaled χ2(33)= 119.29, p<0.001, SB scaled χ2/df=3.61; SRMR=0.04; RMSEA=0.08 (90% IC: 0.06–0.09);

CFI=0.95. However, this model leads to a significant decrease in loadings of this item: from

excellent (0.72) to poor (IP: 0.39; VP: 0.40). We therefore decided to not retain this model. Finally, we investigated whether items of the DTQ were related to a single underlying factor. Results suggested that a single-factor model did not account for the data as well as the two-factor model: SB scaled χ2(35)= 273.87, p<0.001, SB scaled χ2/df= 7.82; SRMR= 0.07;

RMSEA= 0.12 (90% IC: 0.11–0.14); CFI= 0.87; AIC= 10755. This was confirmed by the

Akaike Information Criterion, which was smaller for the two-factor model (AIC= 10576) than for the single-factor model (AIC= 10733).

Table 2 displays standardized factors loadings of the two models. They varied from fair to excellent on the single factor model and from good to excellent on the two-factor model (see Table 2). Spearman’s correlation coefficient between Imaginal Prefiguration and Verbal Perseveration factors was 0.64.

***Insert Table 1 about here*** 3.2. Internal consistency

Omega coefficients were 0.90 for the entire scale, and 0.84 for both factors, suggesting a good internal consistency.

3.3. Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability was evaluated among a sample of 69 participants with ICC. After an interval of 6 weeks, the ICC between the test and the retest were computed for total scores and factors scores. Results revealed an excellent test–retest reliability for the DTQ total score (ICC = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.50–0.83), the imaginal prefiguration factor (ICC = 0.73; 95%

CI: 0.55–0.84), and the verbal perseveration factor (ICC = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.54–0.84).

3.4. Correlation analyses

Spearman’s correlations revealed significant positive correlations between the DTQ factors and alcohol-related measures: the AUDIT total score (imaginal prefiguration factor:

rho = 0.20; p < 0.001; verbal perseveration factor: rho = 0.16; p < 0.001) the binge drinking

score (imaginal prefiguration factor: rho = 0.20; p < 0.001; verbal perseveration factor: rho = 0.15; p < 0.002) and the mean number of units of alcohol consumed by week (imaginal prefiguration factor: rho = 0.13; p < 0.01; verbal perseveration factor: rho = 0.12; p < 0.01).

We also investigated whether our measure of craving was correlated with alcohol-related measures. We found that craving was moderately but significantly coralcohol-related with the mean number of units of alcohol consumed by week (rho = 0.11; p < 0.05), the binge drinking score (rho = 0.13 p < 0.01) and the AUDIT total score (rho = 0.15; p < 0.01). Among AUDIT

items, the highest correlation was found with item 4 which evaluates impaired control over drinking (rho = 0.19; p < 0.001).

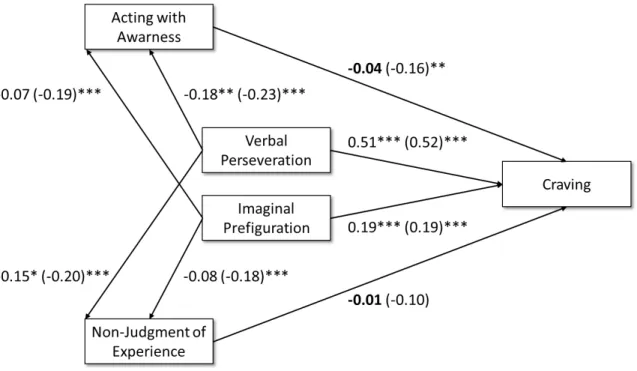

3.4. Testing the confounding effects

Spearman’s correlations revealed significant correlations between the measure of craving and three factors of mindfulness (observation of experience: rho = 0.19, p < 0.001; acting with awareness: rho = -0.19, p < 0.001 and non-judgement of experience: rho = -0.14 p = 0.004). We also observed, as predicted, that both factors of desire thinking were positively correlated with craving and negatively correlated with Acting with awareness and non-judgement of experience.

As hypothesized the effect of acting with awareness on craving [unadjusted effect (95% CI) = -0.159 (-0.26; -0.06), t = -3.15, p = 0.002] lost significance when controlling for the desire thinking factors [adjusted effect (95% CI)= -0.04 (-0.12; 0.03), t = -1.08; p = 0.28], and the effect of non-judgment of experience on craving [Unadjusted effect (95% CI) = -0.098 (-0.20; 0.01), t = -1.95; p = 0.052] dropped from marginally significant to non-significant [Adjusted effect (95% CI) = -0.01 (-0.08; 0.07), t = -0.07; p = 0.94]. Corresponding change-in-estimate (CIA) were of 75% for acting with awareness and 89% for non-judgment of experience. Figure 2 shows the non-adjusted and adjusted beta values of each variable in the model and their level of significance. The final model accounted for 44% of variance with imaginal prefiguration [Beta (95% CI) = 0.186 (0.09; 0.28), t = 3.89, p < 0.001] and verbal perseveration [Beta (95% CI) = 0.51 (0.42; 0.61), t = 10.65, p < 0.001] as the only significant predictors of craving.

***Insert Figure 2 about here***

In order to verify whether this confounding effect was not due to hazard we computed a random variable that followed a normal distribution and tested regression slopes between

recommendations. Results indicated no major changes in beta values and associated p values, and no significant decrease in CIA for both mindfulness variables (data not shown).

Finally, we tested the opposite model: i.e. whether mindfulness could be the confounder in the relation between desire thinking and craving. Results revealed that effect of verbal perseveration on craving [unadjusted effect (95% CI) = 0.523 (0.43; 0.62), t = 10.96, p < 0.001] and imaginal prefiguration on craving [unadjusted effect (95% CI) = 0.189 (0.09; 0.28), t = 3.97; p = 0.001] remained significant when controlling for the mindfulness factors [adjusted effect (95% CI) = 0.515 (0.42; 0.61), t = 10.65; p < 0.001; 0.186 (0.09; 0.28), t = 3.89; p < 0.001, respectively]. Corresponding change-in-estimate were of 0.53 % for verbal perseveration and of 0.01 % for imaginal prefiguration. Adjusted and non-adjusted standardized beta values with their respective p-values are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the psychometric properties of the French version of the DTQ, and explored the potential confounding effect of desire thinking in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. Our first objective was attained. In line with Caselli’s and Spada’s (2011) original version of the DTQ, confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the two-factor solution of the French DTQ, allowing for the distinction between imaginal prefiguration and verbal perseveration. The scale also evidenced a good internal consistency, test–retest reliability and predictive validity.

Our second objective was to test whether desire thinking may act as a confounder in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. We assumed that the presence of desire thinking may inhibit the effects of mindfulness on craving, in line with a metacognitive conceptualization of psychological disorder which emphasizes the combined role of mindfulness and discontinuation of perseverate forms of thinking (such as desire thinking) in tackling distressing states (Wells, 2000). The order of the desire thinking mediators was

chosen on the basis of a conceptual model of the relationship between desire thinking and craving (Caselli and Spada, 2015). Results confirmed our hypothesis with both imaginal and verbal perseveration components of desire thinking acting as confounders in the relationship between mindfulness and craving. These results may explain some of the inconsistencies of the literature concerning the effect of mindfulness on craving. In contrast a second model in which mindfulness was the confounder was far below the classical cut-off 10% in change-in-estimation.

The two factors of mindfulness we found to be associated with craving were acting with awareness (corresponding to a deliberate attentional focus on the current task rather than attending to other things) and non-judgment of experience (which refers to the acceptance of emotions without reacting). The underlying idea is that these mindfulness ‘stances’ or ‘dispositions’ should allow for the perception of craving as a transitory experience and therefore lead to its ‘extinction’. However, this does not appear to be the case if desire thinking is considered. Indeed, what appears to be the case is that desire thinking inhibits mindfulness (hence the negative correlation with mindfulness factors) and fosters craving (hence the positive correlation with craving) simultaneously cancelling out the relationship between mindfulness factors and craving. This finding lends support to the view that mindfulness alone may not be sufficient in managing distressing experiences and that it may need to be potentiated by the purposive interruption of perseverative thinking patterns (such as desire thinking).

The results from this study have clinical implications worth considering. For example, for both prevention and treatment programmes aimed at reducing vulnerability to craving it may be worthwhile to undertake mindfulness training, a technique of the third-wave of cognitive-behavioral therapy (Riley, 2012; Toneatto et al., 2007), as it could help people

be potentiated (or even replaced) by techniques which target directly the interruption of perseverative thinking, such as the attention training technique, detached mindfulness and the postponement of desire thinking (Wells, 2005; Caselli and Spada, 2015; 2016).

Three limitations to our study have to be mentioned. First, our measures were based on self-report. The disadvantage of this type of measurement is that it can be subject to errors. Second, craving was measured with a single-item intensity rating over the previous week. This can bring to biases, specifically focusing on the most salient occasion, or on the frequency of intensity of craving over the period. Studies have shown that neither single-item measures nor multiple-item scale methods appear to be better than the other (Gardner et al., 1998; Diamantopoulos et al., 2012). Moreover, we found that our measure was significantly correlated with several measures of alcohol consumption, including impaired control over drinking, which has been found to strengthen the relationship between self-administration of alcohol and craving (Wardell et al., 2015). Nevertheless, we acknowledge that it would be important, for future research, to verify if with this “global” single-item measure, respondents tend to ignore relevant aspects of craving when compared with a multi-item scale. And finally, this study employed a cross-sectional design and this prevents us from drawing conclusions about causality. Future studies may wish to employ a longitudinal design.

In conclusion, the findings from this study confirm the factorial structure of the DTQ in a French sample and emphasize the important role played by desire thinking in confounding (or limiting) the impact of mindfulness on craving, proposing an explanation for the contradictory results found in the literature concerning the association between mindfulness and craving. Further research should be conducted to assess the effect of interventions aimed at disrupting desire thinking and increasing mindfulness using clinical samples, longitudinal designs and more refined craving assessments.

Role of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributors

Chakroun-Baggioni and Gierski designed the study, undertook the statistical analysis, and conducted the survey process with Corman. Spada and Caselli contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation. Chakroun-Baggioni, Gierski and Corman wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

CATECH for the management and development of experimental applications.

References

Addolorato, G., Leggio, L., Abenavoli, L., Gasbarrini, G., 2005. Neurobiochemical and clinical aspects of craving in alcohol addiction: a review. Addict. Behav. 30 (6), 1209-1224.

Alberts H.J., Mulkens S., Smeets M., Thewissen R., 2010. Coping with food cravings. Investigating the potential of a mindfulness-based intervention. Appetite 55 (1), 160-163.

Alberts H.J., Thewissen R., Raes L., 2012. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite 58 (3), 847-851.

Babor, T.F., De la Fuente, J.R., Saunders, J., Grant, M. 1992. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Healthcare. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Baer, R.A., Smith, G.T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., Toney, L., 2006. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13 (1), 27-45. Bentler, P.M., 2009. Alpha, dimension-free, and model-based internal consistency reliability.

Psychometrika 74 (1), 137-143.

Bowen, S., Chawla, N., Collins, S.E., Witkiewitz, K., Hsu, S., Grow, J., Marlatt, A., 2009. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Subst. Abus. 30 (4), 295–305.

Brislin, R.W., 1986. The wording and translation of research instruments, in: W.J. Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W. (Eds.), Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 137-164.

Browne, M.W., Cudeck, R., 1992. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research 21 (2), 230-258.

Bywaters, M., Andrade, J., Turpin, G., 2004. Intrusive and intrusive memories in a non-clinical sample: The effects of mood and affect on imagery vividness. Memory 12 (4), 467-478.

Caselli, G., Spada, M.M., 2010. Metacognitions in desire thinking: a preliminary investigation. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 38 (5), 629-637.

Caselli, G., Spada, M.M., 2011. The Desire Thinking Questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Addict. Behav. 36 (11), 1061-1067.

Caselli, G., Ferla, M., Mezzaluna, C., Rovetto, F., Spada, M.M., 2012a. Desire thinking across the continuum of drinking behaviour. Eur. Addict. Res.18 (2), 64-69.

Caselli, G., Nikcevic, A.V., Fiore, F., Mezzaluna, C., Spada, M.M., 2012b. Desire Thinking across the Continuum of Nicotine Dependence. Addiction Research and Theory 20 (5), 382-388.

Caselli, G., Spada, M.M., 2013. The Metacognitions about Desire Thinking Questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. J. Clin. Psychol. 69 (12), 1284-1298.

Caselli, G., Soliani, M., Spada, M.M., 2013. The effect of desire thinking on craving: an experimental investigation. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 27 (1), 301-306.

Caselli, G., Spada, M.M., 2015. Desire thinking: what is it and what drives it? Addict. Behav. 44, 71-79.

Caselli, G., Gemelli, A., Spada, M.M., 2017. The experimental manipulation of desire thinking in alcohol use disorder. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 24 (2), 569-573.

Caselli, G., Spada, M.M., 2016. Desire thinking: a new target for treatment in addictive behaviors? International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 9 (4), 344-355.

Comrey, A.L., Lee, H.B., 1992. A first course in factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Erlbaum.

Diamantopoulos A., Sarstedt A.M., Fuchs C., Wilczynski P., Kaiser S., 2012. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (3), 434-449

Forman, E.M., Hoffman, K.L., McGrath, K.B., Herbert, J.D., Brandsma, L.L., Lowe, M.R., 2007. A comparison of acceptance- and control-based strategies for coping with food cravings: an analog study. Behav. Res. Ther. 45 (10), 2372-2386.

Gardner D.G, Cummings L.L., Dunham R.B., Pierce J.L., 1998. Single-Item Versus Multiple-Item Measurement Scales: An Empirical Comparison. Educational and Psychological Measurement 58 (6), 898-915.

Garland, E.L., Gaylord, S.A., Boettiger, C.A., Howard, M.O., 2010. Mindfulness training modifies cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms implicated in alcohol dependence: Results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. J. Psychoactive Drugs 42 (2), 177–192.

Green, M., Rogers, P., Elliman, N., 2000. Dietary restraint and addictive behaviour: The generalisability of Tyffany’s cue reactivity model. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 27 (4), 419-427. Hallgren, K.A., 2012. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview

and tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 8 (1), 23-34.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., Mullen, M., 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6 (1), 53-60.

Hu, L., Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1), 1-55.

Kabat-Zinn, J., 2003. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10 (2), 144-156.

Kline, R.B., 2011. Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling, in : Williams, M., Vogt, W.P. (Eds.), Handbook of methodological innovation in social research methods. Sage, London, UK, pp. 562-589.

Lee, P.H., 2014. Is a Cutoff of 10% Appropriate for the Change-in-Estimate Criterion of Confounder Identification? J. Epidemiol. 24 (2), 161-167.

Lee, P.H., Burstyn, I., 2016. Identification of confounder in epidemiologic data contaminated by measurement error in covariates. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16 (54), 1-18.

MacKinnon, D.P., Krull, J.L., Lockwood, C.M., 2000. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev. Sci. 1 (4), 173-186.

Marlatt, G.A., 1987. Craving notes. Br. J. Addict. 82 (1), 42-43.

Martino, F., Caselli, G., Felicetti, F., Rampioni, M., Romanelli, P. Troiani, L., Sassaroli, S., Albery, I.P., Spada, M.M., 2017. Desire thinking as predictor of craving and binge drinking: A longitudinal study. Addict. Behav. 64, 118-122.

Mehrabian, A., Russell, J.A., 1978. A questionnaire measure of habitual alcohol use. Psychol. Rep. 43 (3), 803-806.

Nunnally, J.C., Bernstein, I.H., 1994. Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill.

O’Malley, S.S., Krishnan-Sarin, S., Farren, C., Sinha, R., Kreek, M.J., 2002. Naltrexone decreases craving and alcohol self-administration in alcohol-dependent subjects and activates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Psychopharmacology 160 (1), 19-29.

Paille, F.M., Guelfi, J.D., Perkins, A.C., Royer, R.J., Steru, L., Parot, P., 1995. Double-blind randomized multicenter trial of acamprosate in maintaining abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol and Alcohol. 30 (2), 239-247.

R Core Team, 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

Revelle, W., 2015. Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. R package version 1.5.8, http://personality-project.org/r/psych-manual.pdf.

Riley, B., 2012. Experiential avoidance mediates the association between thought suppression and mindfulness with problem gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 30 (1), 163-171.

Rosseel, Y., 2012. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2), 1-36.

Satorra, A., Bentler, P.M., 2010. Ensuring positiveness of the scaled chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika 75 (2), 243-248.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., Müller, H., 2003. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online 8 (8), 23-74.

Spada, M.M., Wells, A., 2005. Metacognitions, emotion and alcohol use. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 12 (2), 150-155.

Spada, M.M., Wells, A., 2006. Metacognitions about alcohol use in problem drinkers. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 13 (2), 138-143.

Spada, M.M., Caselli, G., Wells, A., 2009. Metacognitions as a predictor of drinking status and level of alcohol use following CBT in problem drinkers: a prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 47 (10), 882-886.

Spada, M.M., Caselli, G., Wells, A., 2013. A triphasic metacognitive formulation of problem drinking. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 20 (6), 494-500.

Spada, M.M., Caselli, G., Nikčević, A.V., Wells, A., 2015. Metacognition in Addictive Behaviours: an overview. Addict. Behav. 44, 9-15.

Tiffany, S.T., Drobes, D.J., 1990. Imagery and smoking urges: the manipulation of affective content. Addict. Behav. 15, 531-539.

Toneatto, T., Vettese, L., Nguyen, L., 2007. The role of mindfulness in the cognitive-behavioral treatment of problem gambling. Journal of Gambling 19, 91-100.

Townshend, J.M., Duka, T., 2002. Patterns of alcohol drinking in a population of young social drinkers: a comparison of questionnaire and diary measures. Alcohol Alcohol. 37 (2), 187-192.

Wardell, J.D., Ramchandani, V.A., Hendershot C.S., 2015. A multilevel structural equation model of within- and between-person associations among subjective responses to alcohol, craving, and laboratory alcohol self-administration. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 124 (4), 1050-1063.

Wells, A., 2000. Emotional Disorders and Metacognition: Innovative Cognitive Therapy. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Wells, A., 2005. The metacognitive model of GAD: assessment of meta-worry and relationship with DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder. Cognit. Ther. Res. 29 (1), 107-121.

Witkiewitz, K., Bowen, S., Douglas, H., Hsu, S.H., 2013. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance craving. Addict. Behav. 38, 1563-1571.

Witvliet, C.V., Vrana, S.R., 1995. Psychophysiological responses to indices of affective dimensions. Psychophysiology 32 (5), 436-443.

Table 1: Standardized factor loadings of CFA models of the French version of the DTQ.

Single-factor model

Two-factor model

Original items and their corresponding French translation Imaginal Prefiguration

Verbal Perseveration 1. I imagine myself doing the desired activity

Je m’imagine en train de faire l’activité que je désire

0.64 0.71

2. I imagine how I would feel like when engaging in the desired activity

J’imagine comment je me sentirais en me livrant à l’activité que je désire presque jamais

0.71 0.80

3. I anticipate the sensations I would feel practicing the desired activity

J’anticipe les sensations que je ressentirais en faisant l’activité que je désire

0.71 0.79

4. If I did not practice the desired activity for a long time, I would think about it continuously

Si je ne pratiquais pas l'activité que je désire pendant une longue période, j’y penserais continuellement

0.69 0.72

5. When I begin to think about the desired activity I find it difficult to stop

Je trouve difficile d'arrêter de penser à l'activité que je désire quand je commence à y penser

0.68 0.75

6. When I begin to think about the desired activity I continue until I manage to engage in it

Quand je commence à penser à l'activité que je désire, je continue

0.64 0.74

7. I repeat mentally to myself that I need to practice the desired activity

Je me répète mentalement que j’ai besoin de pratiquer l'activité que je désire

0.69 0.68

8. I begin to imagine the desired activity every time it comes to my mind

Je commence à imaginer l’activité que je désire à chaque fois qu’elle me vient à l’esprit

0.75 0.72

9. I imagine myself involved in the desired activity as if it were a movie

Je m’imagine impliqué(e) dans l’activité désirée comme s’il s’agissait d’un film

0.54 0.56

10. My mind is focused on repeating what I desire till I manage to satisfy it

Mon esprit reste focalisé sur la répétition de ce que je désire jusqu’à ce que je parvienne à assouvir ce désir

Figure 1: Conceptual model of the confounding effect of desire thinking in the relationship

Figure 2: Test of model of desire thinking as a confounder in the relationship between Acting

with Awareness and Non-Judgment of Experience on Craving.

Parameter estimates are standardized coefficients of the adjusted model; values in parentheses are non-adjusted effects; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Supplementary Figure 1: Test of model of Mindfulness as a confounder in the relationship

between Verbal Perseveration and Imaginal Prefiguration on Craving.

Parameter estimates are standardized coefficients of the adjusted model; values in parentheses are non-adjusted effects; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.