Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Preventive

Veterinary

Medicine

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / p r e v e t m e d

Applying

participatory

approaches

in

the

evaluation

of

surveillance

systems:

A

pilot

study

on

African

swine

fever

surveillance

in

Corsica

Clémentine

Calba

a,∗,

Nicolas

Antoine-Moussiaux

c,

Franc¸

ois

Charrier

d,

Pascal

Hendrikx

e,

Claude

Saegerman

b,

Marisa

Peyre

a,

Flavie

L.

Goutard

aaCentredeCoopérationInternationaleenRechercheAgronomiquePourleDéveloppement(CIRAD),DépartementES,UPRAGIRs,TAC22/E,Campus

InternationaldeBaillarguet,34398MontpellierCedex5,France

bResearchUnitofEpidemiologyandRiskAnalysisappliedtoVeterinarySciences(UREAR-ULg),FundamentalandAppliedResearchforAnimalandHealth

(FARAH),FacultyofVeterinaryMedicine,UniversityofLiege,QuartierVallée2,AvenuedeCureghem,B-4000Liege,Belgium

cTropicalVeterinaryInstitute,FacultyofVeterinaryMedicine,UniversityofLiege,QuartierVallée2,AvenuedeCureghem,B-4000Liege,Belgium dInstitutNationaldelaRechercheAgronomique(INRA),LaboratoiredeRecherchessurleDéveloppementdeLélevage(LRDE),QuartierGrosseti,BP8,

20250Corte,France

eFrenchAgencyforFood,EnvironmentalandOccupationalHealthSafety(ANSES),31AvenueTonyGarnier,69394LyonCedex07,France

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received15January2015 Receivedinrevisedform 22September2015 Accepted1October2015 Keywords: Participatoryepidemiology Surveillance Evaluation Acceptability Non-monetarybenefits Corsica

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Theimplementationofregularandrelevantevaluationsofsurveillancesystemsiscriticalinimproving theireffectivenessandtheirrelevancewhilstlimitingtheircost.Thecomplexnatureofthesesystemsand thevariablecontextsinwhichtheyareimplementedcallforthedevelopmentofflexibleevaluationtools. Withinthisscope,participatorytoolshavebeendevelopedandimplementedfortheAfricanswinefever (ASF)surveillancesysteminCorsica(France).Theobjectivesofthispilotstudywere,firstly,toassessthe applicabilityofparticipatoryapproacheswithinadevelopedenvironmentinvolvingvarious stakehold-ersand,secondly,todefineandtestmethodsdevelopedtoassessevaluationattributes.Twoevaluation attributesweretargeted:theacceptabilityofthesurveillancesystemanditsthenon-monetary ben-efits.Individualsemi-structuredinterviewsandfocusgroupswereimplementedwithrepresentatives fromeverylevelofthesystem.Diagrammingandscoringtoolswereusedtoassessthedifferentelements thatcomposethedefinitionofacceptability.Acontingentvaluationmethod,associatedwithproportional piling,wasusedtoassessthenon-monetarybenefits,i.e.,thevalueofsanitaryinformation.Sixteen stake-holderswereinvolvedintheprocess,through3focusgroupsand8individualsemi-structuredinterviews. Stakeholderswereselectedaccordingtotheirroleinthesystemandtotheiravailability.Results high-lightedamoderateacceptabilityofthesystemforfarmersandhuntersandahighacceptabilityforother representatives(e.g.,privateveterinarians,locallaboratories).Outofthe5farmersinvolvedinassessing thenon-monetarybenefits,3wereinterestedinsanitaryinformationonASF.Thedatacollectedvia par-ticipatoryapproachesenablerelevantrecommendationstobemade,basedontheCorsicancontext,to improvethecurrentsurveillancesystem.

©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Theregularandrelevantevaluationofsurveillancesystemsis essentialtoestimatetheusefulness andthecorrect application ofthedata generated,and toensurethatlimited resourcesare

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:clementine.calba@cirad.fr(C.Calba),nantoine@ulg.ac.be (N.Antoine-Moussiaux),charrier@corse.inra.fr(F.Charrier),

pascal.hendrikx@anses.fr(P.Hendrikx),claude.saegerman@ulg.ac.be (C.Saegerman),marisa.peyre@cirad.fr(M.Peyre),flavie.goutard@cirad.fr (F.L.Goutard).

usedeffectivelytoprovidetheevidencerequiredforprotecting ani-malandhumanhealth(Hendrikxetal.,2011;Dreweetal.,2015). AccordingtotheHealthSystemsStrengtheningGlossarydeveloped bytheWorldHealthOrganisation(WHO),evaluationrefersto‘the systematicandobjectiveassessmentoftherelevance,adequacy, progress,efficiency,effectivenessandimpactofacourseofactions, inrelationtoobjectivesandtakingintoaccounttheresourcesand facilities that have beendeployed’ (WHO,undated). Applied to surveillance,thisincludestheassessmentofaseriesofevaluation attributessuchassensitivity,acceptabilityandtimeliness,using qualitative,semi-quantitativeorquantitativemethodsandtools (Dreweetal.,2012).Thecomplexityofsurveillancesystems,and http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.10.001

0167-5877/©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

thevariablecontextinwhichtheyareimplemented,entailtheneed forflexibleevaluationtoolsdesignedtotakeintoaccountthe opin-ionofeachstakeholder.Thiscanbeachievedbyusingflexibleand adaptablemethodsbasedonparticipatoryapproacheswithinthe evaluationprocess.

Participatoryapproachesrefertoarangeofmethodsandtools thatenablestakeholders,toa variableextent,toplay anactive roleinthedefinitionandintheanalysisoftheproblemstheymay encounter,andintheirsolution(Pretty,1995;Prettyetal.,1995; Johnsonetal.,2004;Marineretal.,2011;Peyreetal.,2014).Indeed, theuse of visualizationtools through participatoryapproaches leadstoopendiscussionbetween stakeholdersand encourages awide participation(Bradleyetal.,2002).Bytaking stakehold-ers’perceptions,needsandexpectationsintoconsideration,these approachescouldhelpustoachieveabetterunderstandingofthe system(Hoischen-Taubneret al.,2014).Thesemethodsmake it possibletocapturelocking pointsin thesystem, suchas com-municationand coordination between stakeholders, which can gounnoticed when using classical evaluation tools. Theuse of thesetoolsshouldgiverisetorealisticandcontext-adapted rec-ommendations.More importantly,thesetoolslead toenhanced acceptabilityoftheevaluation,toanimprovedfeelingof belong-ingtothesystem,andtoevenownershipoftheevaluationoutputs (Pahl-Wostl,2002).

Factorsusedtoassessthequalityof systemimplementation (e.g.,acceptability, communication),or the non-monetarycosts andbenefits ofsurveillance,are rarelyconsidereddespitetheir importancefordecisionmakersandtheirimpactonsystem perfor-mance(Calbaetal.,2015;Peyreetal.,2014).Acceptabilityrefers tothewillingnessofpersonsandorganizationstoparticipatein thesurveillancesystem,andtothedegreetowhicheachofthese usersisinvolvedinthesurveillance(Hoinvilleetal.,2013);ithas beenlistedbytheCentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention(CDC) asoneofthemainqualitiesofsurveillance(Germanetal.,2001). Thedecisiontoreportasuspectedeventisacriticalfunctionofan emerginginfectiousdiseasesurveillancesystem(Tsaietal.,2009). Inordertolimittheunder-reportingofsuspectedcasesandto iden-tifythebestwaystoimprovethecurrentsurveillancesystem,itis crucialtoassessthestakeholders’willingnesstoparticipateinthis system(Bronneretal.,2014).Non-monetarybenefitsrefertothe positivedirectandindirectconsequencesproducedbythe surveil-lancesystemandhelptoassesswhetherusersaresatisfiedthat theirrequirementshave beenmet(definitiondeveloped bythe RISKSUR1Consortium).Theobjectiveofthisworkwastodevelop

methodsandtoolsbasedonsociology,economicsandparticipatory approachestoassesstheacceptabilityofanimalhealthsurveillance systemsandtheirnon-monetarybenefitsthroughanestimationof theperceivedeconomicvalueofsanitaryinformation.

ApilotstudywasimplementedinCorsicainordertotestthe applicabilityofthesemethodsandtoolsinadevelopedcontext. ThecaseofAfricanswinefever(ASF)surveillanceinCorsicawas chosenfortwomainreasons.Firstly,currentfarmingpracticesare mainlybasedonatraditionalforest-pastoralsystem(outdoor free-rangebreeding)(Casabiancaetal.,1989),andonlyasmallnumber ofruralprivateveterinariansworkontheisland(personal com-munication,OscarMaestrini,INRA).Secondly, Corsicanbreeding systemsarethreatenedbytheendemicpresenceofASFinSardinia; thisquestionsthecurrentsurveillancesystemfacedwithincreased riskofintroduction,spreadandmaintenanceofASFthrough Cor-sica(Desvauxetal.,2014;EuropeanCommission,2011;Muretal., 2014a).Indeed,ASFhasbeenrecognizedtobeamongthemost dev-astatingofpigdiseaseswithseveresocio-economicconsequences

1 Risk-basedanimalhealthsurveillancesystems,EUproject(www.fp7-risksur. eu).

Fig.1. GraphicalrepresentationoftheAfricanswinefever(ASF)surveillancesystem inCorsica(France).

(Moennig,2000;Costardetal.,2013;Torreetal.,2013;Muretal., 2014b).

Originally,thesurveillancesystemtargetedbothASFand Clas-sical swinefever(CSF)but, duetotheincreasing threat,public authorities decidedtoredirectsurveillancetotarget principally ASF.Theobjectiveofthissystemistoensuretheearlydetection ofbothdiseasesbyusingapassivesurveillanceapproachbased onclinicalfindingswithintheentirepopulationofdomesticpigs andwildboars.Thesystemthusreliesonthewillingnessof stake-holderstoreportsuspicions,particularlygiventhefactthatitis impossibletoregularlyassessthehealthofeachanimal(Sawford, 2011).

2. Materialandmethods

2.1. Descriptionofthesurveillancesystemandtargetpopulation Our first approach consisted of identifying stakeholders involvedinthesurveillancesystem.Thesewerethendividedinto threelevels(Fig.1).Level1includedfarmersandhunters,whoare onthefrontlineofpassivesurveillance.Intheeventofasuspected caseofASFinfarmanimals,oramongthewildanimalpopulation, theyaresupposedtocontactthenextlevelinthesurveillance net-work(level2)whichcanbecomposedofprivateveterinarians,of “GroupementsdeDéfenseSanitaire”animalhealthgroups(GDS, associationoffarmers addressinghealth issues,officially recog-nizedbyFrenchlaw(Bronneretal.,2014)),oflocallaboratories,or ofwildlifeorganizations(hunters’federations,forexample).Any suspicionsmustbedeclaredtotheVeterinaryServices,atlocal, regional,andnationallevels.Thesestakeholdersrepresentthethird levelinthesurveillancesystem(level3).Theyareindirect con-tactwiththeauthoritiesinchargeofanimalhealthsurveillance coordination,theDirectorateGeneralforFood(DGAL),which is supervisedbytheFrenchMinistryofAgriculture,Agribusinessand Forest(MAAF).

Participantswerethusselectedaccordingtotheirroleinthe surveillance system (i.e., according to the level to which they belonged),andalsoaccordingtotheiravailabilityandwillingness toparticipate.UsingacontactlistprovidedbytheNational Insti-tuteforAgriculturalResearch(INRA),stakeholderswereidentified andindividuallycontactedbyphone.

Participantswereinterviewedusingfocusgroupsorindividual semi-structuredinterviews.Focusgroupsaredesignedtoexpose a groupof peopletocommonstimuli (Pahl-Wostl,2002).They areparticularlyimportantinassessingcomplexissuesthroughthe analysisofsocialprocessesanddiscussions(Pahl-Wostl,2002).The datacollectionprocessreliedoninterviewingrepresentativesat everylevelofthesurveillancesystem.Indeed,itiscommonin qual-itativeapproachestorelyon‘purposivesampling’tomaximizethe diversityofthedatacollected(i.e.,perceptionsandpointofviews) (GlaserandStrauss,1967;CorbinandStrauss,1990).Thequalityof thesampleisthereforeconsideredtobemoreimportantthanthe samplesizeinsuchapproaches(CôteandTurgeon,2002).Another objectivewastoreachtheoreticalsaturationwhichhasbecomethe goldstandardforhealthscienceresearch(Guestetal.,2006)and whichreferstothepointatwhichnonewinformationisobserved inthedata(Guestetal.,2006).

Theintentionwastoimplementfocusgroupswith(i)ten farm-ers(2groupsof5participants),and(ii)5hunters(onegroup)for level1;(iii)5privateveterinarians(onegroup),and(iv)3GDS tech-nicians(onegroup)forlevel2.Forotherstakeholders,theintention wastoimplementindividualsemi-structuredinterviews:with rep-resentativesfromeachlocallaboratory(twoinCorsica),andone representativeofawildlifeorganizationforlevel2;two representa-tivesofVeterinaryServicesatthelocallevel,andoneattheregional levelforlevel3.

InterviewswereconductedbetweenApril andJune 2014by ateamof2–3evaluators:onewasinchargeofleadingthe dis-cussion,andtheotherswereresponsibleforobservingparticipant behaviorandtakingnotes.Alloftheinterviewswererecordedwith theparticipantsconsentandweresubsequentlytranscribedinto textformatusingMicrosoftWordsoftware(MicrosoftOffice2010, Redmond,WA98052-7329,USA).

3. Assessmentofacceptability

Acceptabilityisrelevanttodifferentaspectsofthesurveillance system.Itfirstreferstotheactors’acceptanceofthesystem’s objec-tivesandofthewayitisoperates.Theacceptanceofthewaythe systemoperatesrefersto(i)theroleofeachactorandthe rep-resentationoftheirownutility,(ii)theconsequencesoftheflow ofinformationforeachactor(i.e.,changesintheiractivityandin theirrelationsfollowingasuspicion),(iii)theperceptionbyeach actoroftheimportanceandrecognitionoftheirownrolerelative tothatofotheractors,and(iv)therelationsbetween stakehold-ers.Trustisanotheressentialelementofacceptability;trustinthe systemandalsotrustinotherstakeholdersinvolvedinthesystem. Theseelementswereassessedusingacombinationof participa-torydiagramingandscoringtools,bothofwhichweredeveloped for,andadaptedto,thisspecificcontext.Threemaintoolswere implemented:(i)relationaldiagrams,(ii)flow diagrams (associ-atedwithproportionalpiling),and(iii)impactdiagrams(associated withproportionalpiling).Thesetoolswereimplementedwithall participants,either through focus groups orthrough individual semi-structuredinterviews.

3.1. Relationaldiagrams

Relationaldiagramsweredevelopedandusedtoidentify pro-fessional networks and interactions among stakeholders. The

participants’statusororganizationwasplaced inthemiddleof aflipchart.Facilitatorsthenaskedthemtolistthestakeholders andorganizationswithwhichtheyinteractedandtodescribethese interactions(i.e.,frequencyandreciprocity).

3.1.1. Flowdiagramsandproportionalpiling

Flowdiagramsweredevelopedandusedtoassessthe partici-pants’knowledgeoftheinformationflowinthecaseofsuspected ASFandtoidentifyhowtheinformationcirculated.Thediagrams weredevelopedbeginningwitharepresentationoflevel1 stake-holders(i.e.,farmersorhunters)forwhomparticipantswereasked toshow thecustomaryflow of information within thesystem, i.e.,towhichstakeholder,ororganization,thesuspicionwouldbe reported.Oncetheparticipantsconsideredthediagramtobe com-plete,proportionalpilingwasperformedtoquantifythelevelof trusttheyhadinthesystem(providingapercentage)andinthe otherstakeholdersinvolved.Thistechniqueallowedparticipants togiverelativescorestoanumberofdifferentitemsorcategories accordingtoonecriterion (Hendrickx etal.,2011).Themethod wasbasedonvisualization,butresultswererecordednumerically (Catleyetal.,2012).Facilitatorsaskedtheparticipantstodivide 100countersintotwoparts,onerepresentingtheirconfidencein thesystemandtheirlackofconfidence.Thecountersallocatedto confidencewerethenusedtospecifythelevelofconfidenceinthe actorsandorganizationsrepresentedinthediagram.

3.1.2. Impactdiagramsandproportionalpiling

Impactdiagrams,adaptedtoassessbothpositiveandnegative impacts of a specific event,are useful todocument the conse-quences as experienced directlyand indirectly bystakeholders (KariukiandNjuki,2013).Inthispilotstudy,thespecificeventwas asuspicionofASFinCorsica.Facilitatorsaskedtheparticipantsto listandexplainthepositiveandnegativeimpactsofasuspicionin theirownwork,organizationandrelations.Proportionalpilingwas thenimplementedonthediagrambyfirstdividingthe100counters betweenpositiveandnegativeimpactsaccordingtotheirweights, andthenbysplittingthecountersacrosstheidentifiedimpactsto assesstheirprobabilityofoccurrence.

4. OASISflashevaluation

OASIS is a standardized semi-quantitative assessment tool whichwasdevelopedfortheassessmentofzoonoticandanimal diseasesurveillancesystems(Hendrikxetal.,2011).Thistoolis basedonadetailedquestionnaireusedtocollectinformationto describetheoperationofthesystemunderevaluation.The infor-mationcollectedissynthesizedaccordingalistofcriteria(78in total),forwhichparticipantsprovidescores(from0to3)following ascoringguide.

TherearetwowaysofimplementinganOASISevaluation.One wayistocompletethequestionnairedirectlywithstakeholders throughinterviews;anotherway(‘OASISflash’)istocompletethe questionnairebasedontheavailabledocumentation.Duetotime constraints,itwasdecidedtoimplementanOASISflashevaluation. 5. Assessmentofnon-monetarybenefits

The economic value of sanitary information was assessed throughacontingentvaluationmethod(CVM)usingproportional pilingandwasimplementedthroughindividualsemi-structured interviewswithfarmers.Thismethodhasbeenusedbyeconomists tovaluechanges innatural resourcesandenvironments,and it is somewhatsimilartomethods usedin marketing toevaluate newconceptsforgoodsandproducts(Louviereetal.,2003).Ithas recentlybeenadaptedtotheevaluationofanimalhealth

surveil-lanceinSouthEastAsia(Delabougliseetal.,2015).Thismethod consistsofdirectinterviewsduringwhichfacilitatorsask individu-alswhattheywouldbewillingtopayforachange(Louviereetal., 2003);inthepresentstudy,theywereaskedwhattheywouldbe willingtopayforsanitaryinformationrelatedtoASF.

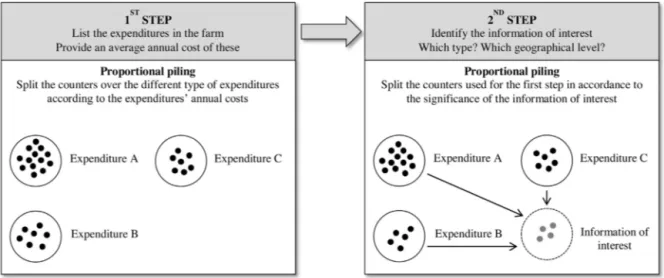

AspresentedinFig.2,thefirststepoftheprocesswasforfarmers toidentifyandtodrawupalistofthemainexpenditureitemsfor theirfarms.Facilitatorsaskedthemtogiveanaveragecostofthese expendituresforoneyear.Proportionalpilingwasthenusedfor theseexpendituresinordertorepresenttheircostswith100 coun-ters.ThesecondstepwastohighlightwhichinformationonASF wasofinteresttotheinterviewee:whichtypeofsanitary infor-mationandatwhich geographicallevel(e.g.,village,commune, region).Thisinformationwasthenaddedtothelistof expendi-tures;thefacilitatoraskedparticipantstodividethecountersused forthefirststepsoastorepresenttheirinterestinthisinformation andthentoexplaintheirchoice.

6. Dataanalysis

6.1. Assessmentofacceptability

Eachelementofacceptability wasassessed byanalyzingthe picturesof thediagramsand alsobyusing thetranscribed dis-cussions asstated inTable 1.The discussionswere transcribed usingMicrosoft Wordsoftware. The acceptability of the objec-tiveofthesurveillancesystemwasassessedusingthequalitative datacollectedduringtheelaborationoftheimpactdiagrams(i.e., discussions).The acceptability of theway thesystem operated wasassessed using all three diagrams (relation diagrams, flow diagrams,andimpactdiagrams)andusingthequalitativedata col-lectedwhilsttheywerebeingdrawn(Table1).Thetrustinthe systemasawholeandinotherstakeholderswasanalyzedonthe basisoftheproportionalpilingimplementedonflowdiagrams,and byanalyzingthequalitativedatacollectedduringthe implemen-tation.

Followingthisfirstanalysis,andinordertobeabletocompare resultsobtainedforeachlevel,qualitativedatawereconvertedinto semi-quantitativedata.Thus,evaluationcriteriaweredeveloped foreachelement.Eachcriterionwasassignedascoreasfollows: low(−1),medium(0),orhigh(+1).Thisscalefrom−1to+1was selectedinordertofacilitatetherepresentationoftheresults,using 0asacentralvalue.

Thefirststepoftheanalysiswasimplementedattheinterview level(i.e.,focusgrouporindividualsemi-structuredinterview)and thescoresobtainedwereusedtocalculatethearithmeticmeanfor eachlevelusingMicrosoftExcelsoftware(MicrosoftOffice2010, Redmond,WA98052-7329,USA).Accordingtothemeanvalue, theacceptabilityofeach elementwasdefined, ateach level,as low(−1to−0.33),medium(−0.32to+0.33),orhigh(+0.34to+1). Theseintervalswerechosenwiththeobjectiveofdividingthetotal distributionspaceintothreeequalparts.

6.2. Assessmentofnon-monetarybenefits

Farmerswereaskedtoprovidealistofthemainexpenditures withtheirassociatedcostsrepresentingtheirproductioncostsin thefarmforthelastyear.Proportionalpilingwasimplementedon expendituresandtheeconomicvalueofeachcounterwas calcu-lated.Thisvaluewasthenusedtoestimatetheeconomicvalueof sanitaryinformationandthewillingnessofparticipantstopayfor it.

6.3. ComparisonwiththeOASISflashevaluation

Sevenstakeholderswereinvitedtojointhescoringprocess:four representativesoftheVeterinaryServices(onefromthelocallevel, onefromthenationallevelandtwofromtheregionallevel),one representativeoftheanimalhealthassociation,onerepresentative ofthelocallaboratoryandoneprivateveterinarian.

Theassessmentofacceptabilitywasbasedon20criteria accord-ingtotheOASISflashmethod,whichcanbegroupedinto8main categories:theorganizationofthesurveillancesystem(e.g., exis-tenceofacharter),itsanimation(e.g.,meetingsfrequencies),and organization(e.g.,integrationoflaboratoriesinthesystem),the human and material resources, feedback to stakeholders, con-sequences of a suspicion, training provided, partnerships and stakeholdersensitization.

7. Results

7.1. Demographicsoftheinterviews

Atotal of16 actorswereincluded,ofwhich3 werewomen and 13 were men. Eight stakeholders were involved through focusgroups,and8throughindividualsemi-structuredinterviews (Table3).Threefocusgroupswereheld:onewith3farmers,one with3 representativesoftheGDS (including one woman),and anotheronewithtworepresentativesoftheVeterinaryServicesat theregionallevel(includingonewoman).Eightindividual semi-structured interviewswere implemented: 2 farmers/hunters, 3 hunters,oneprivateveterinarian,onerepresentativeofthelocal laboratory,andonerepresentativeofthelocalVeterinaryServices (woman).Focusgroupslasted between2and3hwhile individ-ualsemi-structuredinterviewslasted2honaverage.Inaddition,a totalof5individualsemi-structuredinterviewstargetingthe non-monetarybenefitswereimplementedwithfarmers(men),each lasting1h.

7.2. Acceptability

7.2.1. Implementationofthetools

Relationaldiagramswereeasilyimplementedwithmost stake-holders,andweremostlywell-understood.Thistoolwasagood waytointroducetheprocess.It allowedparticipantstodiscuss their work and the relations they have with other stakehold-ers.Theimplementationofthistoolwasmorecomplicatedwith ‘isolated’ participants(some hunters and farmers) due to their poor/inexistentprofessionalnetwork.

Flowdiagramsallowedthecollectionofinformationrelativeto participants’knowledgeaboutthesystemandtheidentification oftheformaland informal pathwaysfor transmissionof suspi-cioninformationwithinthesystem.Theimplementationofflow diagramswasalsomoredifficultwith‘isolated’participants.The implementationofproportionalpiling wasinitially complexfor participantstounderstandbutallofthemgainedaclear under-standingoftheapproach.Moreover,participantsspontaneously explainedtheirchoicesinthenumberofcountersallocatedtoeach stakeholderduringthecourseoftheactivities.Nonetheless,this toolcouldnotbeimplementedduringthefarmers’focusgroup. Indeed,theywerereluctantto‘evaluate’theidentifiedstakeholders throughtheproportionalpiling.

Impactdiagramswereproblematic,andnoteasilyunderstood byparticipants.Theyhadtroubleidentifyingpositiveimpacts fol-lowingasuspicion,mostlyduetothefactthattheywerefocusing moreonoutbreaksratherthanonsuspectedcases.Regardingthe proportionalpilingimplementedonthesediagrams,thefirststep oftheprocess(i.e.,dividingthecountersbetweenthepositiveand

Fig.2. Contingencyvaluationmethodassociatedwithproportionalpilingtoassesstheeconomicvalueoftheinformationofinterest.1ststep—proportionalpilingwas implementedonexpendituresandtheeconomicvalueofeachcounterwascalculated.2ndstep—theparticipantswereaskedtorepresenttheirwillingnesstopayfor sanitaryinformationbytackingcountersfromthealreadylistedexpendituresitemstoacirclerepresentinginformation.

Table1

Participatorymethodsandtoolsusedtoassesstheacceptabilityofanimalhealthsurveillancesystems.

Acceptabilityelements Associatedquestions Associatedparticipatorymethodsand

tools

Objective Istheobjective(s)ofthesurveillance

systeminthelinewiththe stakeholders’expectedobjective(s)?

Impactdiagram

Operation – –

Roleofeachactorandrepresentationofitsownutility Arestakeholderssatisfiedwiththeir duty?

Flowdiagram Consequencesofinformationflow Arestakeholderssatisfiedwiththe

consequencesofinformationflow?

Impactdiagramassociatedwith proportionalpiling

Perceptionbyeachactorofitsownrolerelativetootheractors’ Whatistheperceptionofeachactorof itsownrolerelativetootheractors’?

Flowdiagram

Relationsbetweenstakeholders Arestakeholderssatisfiedwiththe

relationstheyhavewithother stakeholders?

Relationaldiagram

Trust –

Inthesystem Dostakeholderstrustthesystemto

fulfilitssurveillanceobjective(s)?

Flowdiagramassociated withproportionalpiling Inotherstakeholdersinvolvedinthesystem Dostakeholderstrusttheother

stakeholderstofulfiltheirroleinthe system?

Flowdiagramassociated withproportionalpiling

negativeimpacts)waseasilyimplemented;whereas thesecond

step(i.e.,dividingthecountersbetweenthedifferentidentified

impacts)wasmore confusingforsomeparticipantsand it took

moretimeforthemtounderstandtheprocess.

7.2.2. Scoringcriteria

Basedontheanalysisofthequalitativedatagatheredduring

thediscussions,andtheanalysisofthediagramsandproportional

piling,scoringcriteriaforeachelementofacceptabilitywere

devel-oped(Table2).

Informationprovidedbyrelationaldiagramswasconvertedinto quantitativedata.Tomeasurethefrequencylevel,eacharrowwas associatedtoanumericalvalue:0forveryrare,2forrare,4for regularand6forverycommon(Table2).Thesameprocesswas implementedforreciprocity:0whentherewasnorelation,2when itwasone-sidedand4whentherelationwasmutual(Table2).

Nonetheless,‘theperceptionbyeachactoroftheimportance andrecognitionoftheirownrolerelativetootheractors’couldnot beassessedusingthecollecteddataduetothefactthatthiselement didnotappearspontaneouslyinasufficientnumberofinterviews. Thereforeithasbeenleftoutfromthepresentanalysis.

Table3

Demographicsoftheinterviewsimplementedfortheparticipatoryapproachesand fortheOASISflashevaluationtoolinthescopeoftheassessmentoftheAfrican swinefever(ASF)surveillancesystemacceptabilityinCorsica.

Evaluationprocess Participants NumberInterviewtype

OASIS VS—Nationallevel 1 Expertopinion

VS—Regionallevel 1 VS—Locallevel 1

GDS 1

Total 4

ParticipatoryapproachesFarmers 3 Focusgroupsdiscussion Farmers/hunters 2 Individualinterview Hunters 3 Individualinterview Privateveterinarian1 Individualinterview

GDS 3 Focusgroupsdiscussion

Laboratory 1 Individualinterview VS—Locallevel 1 Individualinterview VS—Regionallevel 2 Focusgroupsdiscussion

Total 16

7.2.3. Participatoryassessment

Elementsofacceptabilitywerescoredaccordingtothecriteria

Table2

Criteriadevelopedtoprovidescoresandlevelstotheelementsofanimalhealthsurveillancesystemsacceptability.

Acceptabilityelements Criteria Associatedscores

Objective Participantsdidnotidentifyanyobjective,ortheyidentified objectivesthatdidnotcorrespondtotheobjectiveofthe surveillancesystem

Weak −1

Theidentifiedobjectivewaspartiallycorrespondingtotheone ofthesystem

Medium 0

Theidentifiedobjectiveexactlycorrespondedtotheobjective ofthesystem

Good +1

Operation

Roleofeachactorandrepresentationofits ownutility

Participantsidentifiedonlynegativepointsrelativetotheir ownroleandutility

Weak −1

Therewasabalancebetweennegativeandpositivepoints Medium 0

Mostlypositivepointscameout Good +1

Consequencesofinformationflow Themajorityoftheconsequencesidentifiedwerenegative,or theweightofnegativeconsequenceswasmuchhigherthan theoneofthepositiveconsequences

Weak −1

Therewasabalancebetweenthepositiveandnegative impacts,ortherewasabalancebetweentheweightofpositive andnegativesimpacts

Medium 0

Mostlypositiveconsequenceswereidentified,orwhentheir weightwasmuchhigherthantheoneofnegativeimpacts

Good +1

Perceptionbyeachactorofitsownrole relativetootheractors’

Nocriteria – –

Relationsbetweenstakeholders Frequency+reciprocity

[0;3] Weak −1

[4;7] Medium 0

[8;10] Good +1

Trustinthesystem Numberofcountersallocatedforthetrustinthesystem

[0;33] Weak −1

[34;66] Medium 0

[67;100] Good +1

Fig.3.GraphicalrepresentationoftheacceptabilityoftheAfricanswinefever(ASF)surveillancesysteminCorsica.Level1—farmersandhunters;level2—privateveterinarians, animalhealthgroupsandlocallaboratories;level3—veterinaryservices(locallevelandregionallevel).

Theacceptabilityoftheobjectiveofthesurveillancesystemwas

consideredasmediumforlevel1(0.2)andforlevel2(0.33)(Fig.3).

Itwashighforlevel3(1)(Fig.3).Accordingtoparticipants, pas-sivesurveillanceseemedinsufficienttoreachtheobjectiveofearly detection.Theystatedthatoncethediseaseisactuallydetectedin pigsitisalreadytoolatetoprotectpigpopulationsfrominfection. Consequently,theintroductionofthediseasemustbeavoidedand harborsurveillanceand awarenesscampaigns targetingtourists shouldbereinforced.

Mostlevel1participants(6/8)understoodtheirroleinthe sys-temandacceptedit,includingthereportingofanyASFsuspicion. Thereforetheacceptabilityoftheirroleandutilitywashigh(0.4) (Fig.3).Theconsequencesoftheinformationflowseemedtoyield alowlevelof acceptability(−0.6)(Fig.3),butdifferedbetween

farmersandhunters.Thethreehuntersdidnotidentifyany conse-quencesfollowingasuspicionduetothefactthattheyhadnever experiencedanASFepidemic.Forallfarmers,theconsequences werenotwell-acceptedbecauseofregulatoryrestrictions tobe implementedonthefarm(i.e.,animalshavetobepenned), lead-ingtoincreasedfeedcosts.Inaddition,anddespitethefactthat ASFisnotazoonoticdisease,consumerconfidenceintheproduct couldbeaffected,causingdamagethroughouttheentiresector. However,respondentsanticipated that iftherewasa suspicion ofASFinCorsica,farmerswouldfacetheproblemtogether;this would probablygiverise tocollectiveeffortsand contributeto improvingthesector’sorganization.Satisfactionregardingthe rela-tionsbetweenstakeholderswasmedium(-0.2)(Fig.3).Allfarmers feltisolatedand‘completelyabandoned’byanimalhealthservices

(by private veterinarians, GDS and Veterinary Services). Farm-erscommentedthat ‘contactswiththeveterinariancorrespond tominimumrequirements’,2statingmorethanonce,andfinding

regrettable,that‘90%oftheinformationcamefromfarmers’.2Most

ofthehunters (fouroutof thefiveinterviewees,includingtwo farmers/hunters)hadaverypoornetwork,theirsolerelationsbeing withotherhunters.

Level2participantswerenotcompletelysatisfiedwiththeir role,theacceptabilityofthiselementwasthereforemedium(0) (Fig.3).Theprivateveterinarianhighlightedthefactsthatinthe caseofanASFsuspicion‘itisimpossibletocomplywithsafety stan-dardsimposedbyemergencyplans’.3Thelocallaboratorystated

that ‘the perception of each other’s roles in the system is not clear’.4GDStechniciansdescribedthedifficultiesofbeinga

moder-atorbetweenVeterinaryServicesandfarmers.Theconsequences of informationflow were consideredtobeof low acceptability (−1)(Fig.3).Level2participantshighlightedthatanASF suspi-cionwouldcauseanincreaseanddisorganizationoftheirworkload, leadingtoadecreaseinthesurveillanceofotherdiseases,evenif itcouldspuranincreaseincontactandcollaboration.The satisfac-tionoftherelationsbetweenstakeholderswaslow(−0.3)(Fig.3). Nonetheless,boththeprivateveterinarianandtheGDStechnicians complainedabouttherelationswiththeVeterinaryServicesatlocal level.TheystatedthattheVeterinaryServicesdidnotalways pro-videtherequiredinformation.However,theyhighlightedthatthis wasmostlyduetohumanconstraints.Althoughtheywereaware ofthepotentiallyimportantroleofwildlifeinthespread ofthe disease,theycomplainedaboutthelackofcollaborationbetween wildlifeandanimalhealthsectors.

Alllevel3participantsagreedonahighacceptabilityoftheir roleandutilityinthesystem(1)andexpressedmedium accept-abilityfortheconsequencesofinformationflow(0)(Fig.3).They statedthatasuspicion‘couldresultinfeedbackwhichwouldallow thesystemtobetestedandraiseawarenessamongstakeholders’5;

andcouldincrease contactandcollaborationbetween organiza-tions.Nonetheless,theystatedthatasuspicionwouldalsocause anincreaseanddisorganizationoftheirworkload.Thesatisfaction oftherelationsbetweenstakeholderswasmedium(0)(Fig.3).Also, therewasacertainlackofdirectcontactwithlevel1.

Thetrustoflevel1participantsinthesystemwaslow(−0.7) (Fig.3)andrangedfrom15to56%.Onehunterstatedthat ‘peo-plewilllistenifthere isa problem,but Iamnotsurethatany actionwillbetaken’.6Thetwootherhuntersinvolvedknew

noth-ingaboutthewayinwhichthesystemwasorganizedandoperated, thus theycouldnot draw theflow diagram. Theother partici-pantsshowedsomehesitationindrawingthesurveillancesystem scheme.Thetimetakentodo theexerciseandholdtherelative discussionsshowedthattheseactorswerenotveryfamiliarwith thesystembeyondtheirfarmenvironment.Fourfarmersdidnot completelytrustotherfarmers because‘someofthemwillhide it[suspicion],atleastinitially’7;anddidnottrustVeterinary

Ser-vicesatthelocallevelbecauseofbudgetconstraints,andatthe nationallevelbecause‘forthemCorsicaisjustadropintheocean comparedtoFranceasawhole’.Twofarmers/huntersdidnot com-pletelytrusthunterseitherbecauseoftheirlackofawareness,and didnottrustwildlifeorganizationsbecauserelationsbetweenthem wereminimal.

2Focusgroupwithfarmers,28thMay2014.

3Individualsemi-structuredinterviewwithaprivateveterinarian,6thJune2014. 4Individualsemi-structuredinterviewwithalocallaboratory,3thJune2014. 5Individualsemi-structuredinterviewwithVeterinaryServicesatthelocallevel,

12thJune2014.

6Individualsemi-structuredinterviewwithahunter,4thJune2014. 7Focusgroupwithfarmers,28thMay2014.

Forlevel2,thetrustallocatedtothesystemasawholewas medium(0)(Fig.3),about37%.Allparticipantsagreedthatthere wereproblemswiththelocallaboratoriesduetobudgetaryand humanconstraints,andtothedifficultiesinsendingsamplesto mainlandFrance.GDSrepresentativesstatedthattheydidnottrust allprivateveterinariansbecause‘they arenot interestedin the pigsector’.8 Eventheprivateveterinarianhighlightedthatmost

ofthemhadneverexperiencedASFinthefield,andcouldmissa suspicioncaseastheymightnotsuspectthisdisease.Theyagreed that‘thecriticalpointisthefarmers’,because‘theywillcallatthe lastmoment[incaseofsuspicion],theywilleventendtohideit’.

Forlevel3,thetrustallocatedtotheentiresystemwasmedium (0)(Fig.3),about40%.Again,locallaboratorieswereidentifiedasa criticalpointinthesystem,duetothesamereasonsstatedbylevel2 participants.VeterinaryServicesrepresentativeshadalackoftrust regardingfarmers,especiallyduetothespecificitiesofthe dom-inantfarming system(free-ranging). Indeed,as onerespondent highlighted,farmersdonotseetheiranimalseverydayandcan thereforetakesometimetonoticethatsomeanimalsaremissing. 7.2.4. OASISflashassessment

Atotaloffourstakeholdersjoinedthescoringprocess:three representativesfromtheVeterinaryServices(onefromeachlocal, nationalandregionallevel),andonerepresentativeoftheanimal health association (Table 3).Results from this evaluation high-lighteda moderateacceptabilitymostlydue tothemeasuresto beimplementedinsuspiciousfarms(i.e.,farmswithatleastone suspectedcaseofASF).

7.3. Non-monetarybenefits

Threeoutofthefivefarmersinterviewedshowedaninterestin sanitaryinformation(Table4),andmorespecificallyinASF.They wereinterestedinthisinformationattheregionallevel.They high-lightedthattheinformationwouldnotbethatusefulduetothefact thattheydonotknowhowtodealwithanepidemicofthis dis-ease.Nonetheless,theywereawareofitsrapidspread,andofthe highmortalityratesandthecurrentlackofavaccine.Theseactors showedawillingness-to-paybetween187D and5283D for infor-mationrelatedtoASFinCorsicaforayear(Table4),representing from1.76to4.13%oftheirfarmproductioncosts(Table4).

Thetwootherfarmerswerenotinterestedin sanitary infor-mationrelatedtoASF.Bothofthemsaidthatdiseases‘arepartof nature’andthatthereisnothingtodobuttowaitfortheendof apotentialepidemic,especiallyforASF.Thus,noneofthemwere readytoinvestinsanitaryinformation(Table4).

8. Discussion

Thispilotstudydevelopedandtesteda methodologyforthe implementation of participatory tools to measure acceptability andnon-monetarybenefitsusingqualitativeandsemi-quantitative data.Moreover,ithighlightedtheadvantagesandlimitationsof usingsuchapproaches.Bydirectlyassessingstakeholder percep-tionsandexpectations,arelationshipoftrustwasdevelopedwith theinterviewees.Thestakeholders’interestinASFandinthe exist-ingsurveillancesystemwasalsoraised.Participatorymethodsand toolsfurtherfacilitatedthediscussionaboutmonetaryaspectswith farmers.Thevisualizationtoolshelpedthestakeholderstodiscuss theirperceptionofthesurveillancesystem.Thesetoolsenabled collectionoffurtherinformationregardingthecontextinwhich stakeholdersoperateandcontributetosurveillance.Thankstothe

Table4

Resultsfromthecontingencyvaluationmethodimplementedwithfarmers,usedtoassesstheeconomicvalueofthesanitaryinformationofinterestinCorsica.NA—Not applicable.

Farmers Numberofanimals Listofexpenditures Costperyear(D) Economicvalueofthe information(D)with standarderror Economic valueofthe information(%) #1 40 NA NA 0 0 #2 85 Infrastructures 10,000 4.13 Deworming 1200 1700 Feed 30,000 (±150) Total 41,200 #3 100 Vaccination 200 1.76 Deworming 400 187 Feed 10,000 (±62) Total 10,600 #4 200 NA NA 0 0 #5 500 Vaccination 16,500 8.04 Deworming 13,200 5200 Feed 35,000 (±660) Total 64,700

involvementofrepresentativesfromalllevels,thelimitationsof

thecurrentsystemwerehighlighted.Nonetheless,the

implemen-tationofparticipatoryapproachesappearedtobetimeconsuming.

Timewasrequiredtomakeindividualcontactwithstakeholders,to

presenttheprojecttothemandtodefinetheirwillingnessto

par-ticipateinthestudy.Italsotooktimetodefineadateandtofind

aplacefortheinterview.Anotherconstraintwasrelated tothe

playfulaspectsoftheseapproaches,whichmighthaveappeared

tosomestakeholderstobelackinginearnestness(mainlyinfocus

groups).However,participantsgenerallywelcomedtheevaluation

processandtheuseofvisualrepresentationtoolswhichallowed

themtoclearlyrepresenttheirperceptionofthesystem.

Relationaldiagramswere a good wayto introduce the

pro-cess,allowingparticipantstotalkaboutsomethingtheyknowwell.

Nonetheless,theelaborationofthesediagramswasmore

compli-catedwith‘isolated’participants.Theydidnotunderstandhowto

buildtherelationaldiagramduetotheirlackofcontactwith

oth-ers.Theseresultsraisemoregeneralquestionsregardingtheway

inwhichsemi-structuredinterviewsshouldbeconductedwhenan

overallapproachofthetopicseemstricky.Indeed,inthepresent

case,itwasnecessarytoascertaintheabsenceofrelationswith

otherstakeholders.Onewaytodosocouldbetoprovide

partic-ipantswithexamples,askingthemtoconfirmthattheydo not

havecontactwithothers.This,however,wouldentailtheriskof

directingtheanswersgivenbytheintervieweesorofmakingthem

feeluncomfortableandimpedingthesmoothprogressofthe

dis-cussion.Also,theinformationprovidedbythesediagramsdidnot

allowaclearassessmentofthelevelofsatisfactionregarding

rela-tionsbetweenstakeholders.Indeed,thetoolallowedparticipants

totalkaboutthefrequency ofcontact withotherstakeholders,

butinfactitwouldhavebeenincorrecttoassimilatefrequency

ofcontactwiththelevelofsatisfaction.Insomerelationships,

con-tactmayberare,butsufficienttosatisfystakeholders.Inthiscase,

therewouldbeaneedtoimplementanadditionaltooltoassess

thelevelofsatisfaction,throughtheuseofsatisfactiontokenson

therelationaldiagramsforexample.

Theflowdiagramsweremoredifficulttoimplementwith

‘iso-lated’ participants also, who had no knowledge either on the

surveillancesystemor onthe stakeholdersinvolved init. Once

again,itwouldbenecessarytofindawaytoconductinterviews

thatwould ascertainthisisolation withoutinducingforced and

thereforeunreliableanswers.Moreover,participantsoftenshifted

duringdiscussionsfromthereferencingofasuspiciontothatof

aconfirmedASFoutbreak.Whenthisoccurred,thefacilitator

cor-rectedparticipantstokeepthemontherighttrack;nevertheless,

participantsoftenreiteratedthisconfusion.Pushingparticipants

inanotherdirectioncouldhaveraisedsomenegativefeelings,and

couldhaveledtoalackofinterestintheinterview.Therefore,some

degreeofconfusionbetweensuspicionandoutbreakinanswers

couldnotbeavoided.Wemaynotethattheparticipatoryprocess

allowstheinterviewertoidentifysuchconfusionsandtotakethese

intoaccountintheconclusions,somethingthatwouldbemore

difficulttoachievewithapproachesbasedonsystematic

question-naire.Theimplementationofproportionalpilingwasunderstood

andimplementedbymostparticipants.Nonetheless,participants

fromthefarmers’focusgroupsdidnotwanttoimplementit.This

mayhavebeenduetoapoorunderstandingofthetool’sobjective,

ortothefactthattheyperceiveditas‘achildishgame’.Itmayalso

havebeenduetothefactthatoneoftheparticipants,whoisdeeply

involvedinCorsicanpolitics,didnotwanttohandlethecounters

andmayhaveinfluencedtheothersinthisdirection.

Itwasdifficulttoimplementtheimpactdiagramsduetothe

factthatparticipantsdidnotwanttoidentifythepositiveimpacts

producedbyanASFsuspicion.Indeed,someparticipantsdenied

thatanypositiveimpactscouldbeidentifiedduetothefactthat

‘nothinggoodcanarisefromacrisis’.

Theanalysisofdiagrams,proportionalpilinganddiscussions

duringtheinterviewsallowedustodevelopscoringcriteriaforthe

previouslyidentifiedacceptabilitycriteria.Nonetheless,itwasnot

possibletodothisforonecriterion(i.e.,perceptionbyeachactor

oftheimportanceandrecognitionofhis/herownrolerelativeto

otherstakeholders).Thiselementwasthereforeexcludedfromthe

analysisaswecouldnotidentifyanyqualitativedatawithwhich

toassessit,makingitimpossibletodevelopevaluationcriteria.

BycombiningCVMwithproportionalpiling,wewereableto

assessthefarmers’interestinsanitaryinformationrelatedtoASF.

Themethodwaseasytoimplementandparticipantsreadily

pro-videdanestimationoffarmexpenditures.Thekindofinformation

soughtandthegeographicalareatargetedwereidentified,thus

allowinginformationtobecollectedonthefarmers’perceptionof

thedisease.Nonetheless,theuseofonly100countersfor

propor-tionalpilinghasledtoatendencytooverestimatetheeconomic

valueof the information. Thisoverestimation wasthus greater

whenthetotalexpenditureswerehigher.Onewayofimproving

thismethodwouldbetoincreasethenumberofcountersinorder

togainamoreaccurateestimationofthiseconomicvalue.Itwould

alsobevaluabletoidentifysomepointsoffactualcomparisonin

order togage the relevance of thefinal estimated

willingness-to-pay. Expendituresoninsuranceproducts couldbeusedas a

farminsurancemaybeinterpretedasameansofriskaversionand wouldallowabetterunderstandingofthefarmers’willingnessto payforsanitaryinformation(Shaiketal.,2006).

Thesemi-quantitativemethoddevelopedtoassesseach accept-ability criterion, although subjective, facilitated comparisons betweenthedifferentlevels.TheOASISflashmethodisalsobased onthistypeofsemi-quantitativescoring,butinvolvedonlyasmall sample ofstakeholders and didnotinclude level 1 representa-tives.Fewparticipantswereinvolvedinthispilotstudy,andthus somepointsofviewmaybemissing.Nonetheless,resultsfromthis pilotstudyallowedustocollectrelevantinformation regarding thecurrentsurveillancesysteminCorsica.Inthefuture,itwould benecessarytofindabalancebetweenthenumberofstakeholders tobeincludedandthetimeavailabletoundertakesuchastudy. Therecommendationsfromtheresearchteamwouldbetoinvolve atleastfifteen representativesfromlevel one(i.e.,farmers and hunters).

Qualitativeapproachesrelyon‘purposivesampling’to maxi-mizethediversityofthedatacollected(i.e.,perceptionsandpoint ofviews)(Bronneretal.,2014).Participantswereselectedinorder toachievethisdiversity,andtoreachthetheoreticalsaturationof thedata(Côteand Turgeon,2002).Thisstandard forqualitative researchwasnotachievedduringthispilotstudybecauseoftime constraints,andduetothelackofavailabilityofcertain stakehold-ers.Moreover,participantsfromalllevelswereselectedaccording totheiravailabilityandalsototheirwillingnesstoparticipateinthe study.Thismeansthatmostofthepeopleinvolvedinthisstudyhad aninterestinanimalhealth.Asthiswasapilotstudy,theremay alsohavebeenbiasesinthewaythequestionswereformulated andintheguidanceprovidedtostakeholders.Thelackof involve-mentofsurveillancebeneficiaries(i.e.,level1)intheOASISflash evaluationprocessmayalsobeasourceofbiasintheresults.

Thisstudyconfirmedthefindingsofotherstudieswhichshowed thatparticipatorymethodsandtoolsplayanimportantrolein help-ingresearchersanddecisionmakerstoreconnectwithfarmers,and togainabetterunderstandingofdiseasesfromalocalperspective (CatleyandAdmassu,2003).Nonetheless,duetothefactthat par-ticipatoryapproachesaremostlyusedindevelopingcountries,itis notcurrentlypossibletocomparetheresultsstemmingfromthis studywiththoseofotherresearchprojects.Resultsobtainedfrom thisfieldworkmightthusproviderealinsightsintostakeholder perceptions.Thecommunicationoftheseresultstodecision mak-ersshouldcontributeimprovedsurveillanceandcontrolstrategies (Catley etal., 2012).Indeed,this pilotstudy canbeconsidered asadevelopmentalevaluation,withlearninggoalsandnot judg-mentones(Dozoisetal.,2010).Thistypeofevaluationhasbeen recognizedasawayofsupportingadaptivelearning,leadingto adeeperunderstandingofstakeholders’problems,resources,and thebroadercontext(Dozoisetal.,2010).Theuseofparticipatory methodsandtoolsintheevaluationprocessledtothe empower-mentofstakeholders,thusimprovingboththeiracceptanceofthe evaluationandtheirfeelingofownership.Thiscouldimprovethe sustainabilityofhealthinterventions(Calbaetal.,2014).Several authorshighlightthat,besidesitschallenges,participatory eval-uationcanbeseen asa veryusefulapproach totheevaluation ofhealth preventionprograms as‘it strengthenscapacities and alliancesamongparticipants,fosterscommitmenttohealth pro-gramprinciplesandhasalsoprovedtobeausefuldecisionmaking tool’(RiceandFranceschini,2009;Nitschetal.,2013).

Althoughacceptabilityrepresentsanimportantconcerninthe evaluationprocess,limitationsexistregardinghowthisattribute shouldbeconsideredandevaluated(Aueretal.,2011).The partic-ipatoryapproachesdevelopedinthisstudyallowedthedifferent elementsbehindtheacceptabilitydefinitiontobeassessed.Since the information from all levels is critical for effective disease surveillance(Tsaietal.,2009),wemayconsiderthatthedata

col-lectedwiththisapproachgaverisetorelevantrecommendations fortheCorsicancontextthatcanbeimplementedtoimprovethe currentsurveillancesystem.

Moreover,economicevaluationshouldbeanintegral partof theevaluationofanimalhealthsurveillancesystems,evenifthis islikelytobeadifficultparttoachieve(Dreweetal.,2012;Drewe etal.,2015).Thebenefitsassessment,includingnon-monetary ben-efits, mustbepartofaneconomic evaluationprocess. Thisis a criticalpointfordecisionmakerswhoneedtomakechoicesbased onlimitedordiminishingresources(Dreweetal.,2012).Usinga CVMmethodtoassessnon-monetarybenefitscouldfilltheexisting gapsregardingtheeconomicevaluationofsurveillancesystems. Nonetheless,themethodimplementedthroughthispilotstudystill requiressomeadjustmentinordertobetterassessthe stakehold-ers’interestinsanitaryinformation,andthustoengagetheminthe surveillancesystem.

9. Conclusion

Socio-economicevaluationattributesarerarelyconsideredin theevaluationofanimalhealthsurveillance;thismaybedueto thelackofmethodsandtoolsavailablefortheirassessment.The present work providesaninitial step in thedirectionof filling thesegaps.Themethodology developed,basedonparticipatory approaches, allowed us to assess the acceptability of the ASF surveillancesysteminCorsica,andtocollectinformationrelative tothenon-monetarybenefitsofthissurveillanceforfarmers.

Inordertofurtherassessitsapplicability,theproposedmethod shouldbeappliedindifferentcontexts,targetingothersurveillance systemswithdifferentobjectives.

Conflictofinterest

Allauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoconflictsofinterest rele-vanttothispaper.

Acknowledgements

ThisreviewwasperformedundertheframeworkoftheRISKSUR project,fundedbytheEuropeanUnionSeventhFramework Pro-gramme(FP7/2007–2013)underthegrantagreementno310806. WewouldliketoextantourthankstoDrCasabianca(LRDEresearch unitDirector,INRACorte),OscarMaestrini(INRACorte),andtoall participantsfortheirimplicationinthiswork.Wearegratefulto AnitaSaxena DumondforreviewingtheEnglish.Wewould like tothankstheASForceproject(EC,FP7-KBBE-2012-6,Projectno 311931)fortheirhelpfulcollaborationsinCorsica.

References

Auer,A.M.,Dobmeier,T.M.,Haglund,B.J.,Tillgren,P.,2011.TherelevanceofWHO injurysurveillanceguidelinesforevaluation:learningfromtheAboriginal Community-CenteredInjurySurveillanceSystem(ACCISS)andtwo institution-basedsystems.BMCPublicHealth11,744.

Bradley,J.E.,Mayfield,M.V.,Mehta,M.P.,Rukonge,A.,2002.Participatory evaluationofreproductivehealthcarequalityindevelopingcountries.Soc.Sci. Med.55,269–282.

Bronner,A.,Hénaux,V.,Fortané,N.,Hendrikx,P.,Calavas,D.,2014.Whydofarmers andveterinariansnotreportallbovineabortions,asrequestedbytheclinical brucellosissurveillancesysteminFrance?BMCVet.Res.10,93.

Calba,C.,Goutard,F.L.,Hoinville,L.,Hendrikx,P.,Lindberg,A.,Saegerman,C.,Peyre, M.,2015.Surveillancesystemsevaluation:asystematicreviewoftheexisting approaches.BMCPublicHealth15,448.

Calba,C.,Ponsich,A.,Nam,S.,Collineau,L.,Min,S.,Thonnat,J.,Goutard,F.L.,2014. Developmentofaparticipatorytoolfortheevaluationofvillageanimalhealth workersinCambodia.ActaTrop.134,17–28.

Casabianca,F.,Picard,P.,Sapin,J.,Gauthier,J.,Vallée,M.,1989.Contributionà l’épidémiologiedesmaladiesviralesenélevageporcinextensif.Applicationà laluttecontrelemaladied’AujeszkyenRégionCorse.JournéesRecherches PorcinesFrance21,153–160.

Catley,A.,Admassu,B.,2003.Usingparticipatoryepidemiologytoassessthe impactoflivestockdiseases.In:FAO-OIE-AU/IBAR-IAEAConsultativeGroup MeetingonContagiousBovinePleuropneumoniainAfrica,12–14November 2003,FAOHeadquarters,Rome,Italy.

Catley,A.,Alders,R.G.,Wood,J.L.,2012.Participatoryepidemiology:approaches, methods,experiences.Vet.J.191,151–160.

Corbin,J.M.,Strauss,A.,1990.Groundedtheoryresearch:procedures,canons,and evaluativecriteria.Qual.Sociol.13,3–21.

Costard,S.,Mur,L.,Lubroth,J.,Sanchez-Vizcaino,J.,Pfeiffer,D.,2013.Epidemiology ofAfricanswinefevervirus.VirusRes.173,191–197.

Côte,L.,Turgeon,J.,2002.Commentliredefac¸oncritiquelesarticlesderecherche qualitativeenmédecine.Pédag.Méd.3,81–90.

Delabouglise,A.,Antoine-Moussiaux,N.,Phan,T.,Dao,D.,Nguyen,T.,Truong,B., Nguyen,X.,Vu,T.,Nguyen,K.,Le,H.,Salem,G.,2015.Theperceivedvalueof passiveanimalhealthsurveillance:thecaseofhighlypathogenicavian influenzainVietnam.ZoonosesPublicHealth,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/zph. 12212.

Desvaux,S.,LePotier,M.F.,Bourry,O.,Hutet,E.,Rose,N.,Anjoubault,G.,Havet,P., Clément,T.,Marcé,C.,2014.Pesteporcineafricaine:étudesérologiquedansles abattoirsenCorsedurantl’hiver2014.Bull.Epidémiol.63,19.

Dozois,E.,Blanchet-Cohen,N.,Langlois,M.,2010.DE201:APractitioner’sGuideto DevelopmentalEvaluation.TheJ.W.McConnellFamilyFoundationandthe InternationalInstituteforChildRightsandDevelopmenthttp://www. mcconnellfoundation.ca/en/resources/publication/de-201-a-practitioner-s-guide-to-developmental-evaluation.

Drewe,J.,Hoinville,L.,Cook,A.,Floyd,T.,Gunn,G.,Stärk,K.,2015.SERVAL:anew frameworkfortheevaluationofanimalhealthsurveillance.Transbound. Emerg.Dis.62,33–45.

Drewe,J.,Hoinville,L.,Cook,A.,Floyd,T.,Stärk,K.,2012.Evaluationofanimaland publichealthsurveillancesystems:asystematicreview.Epidemiol.Infect.140, 575–590.

EuropeanCommission,2011.CommissionImplementingDecisionof15December 2011amendingDecision2005/363/ECconcerninganimalhealthprotection measuresagainstAfricanswinefeverinSardinia,Italy.http://eur-lex.europa. eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX.32007D0012&from=EN(accessed 29.04.15.).

German,R.R.,Lee,L.,Horan,J.,Milstein,R.,Pertowski,C.,Waller,M.,2001.Updated guidelinesforevaluatingpublichealthsurveillancesystems.MMWR recommendationsandreports.Cent.Dis.ControlPrev.50,1–35. Glaser,B.,Strauss,A.,1967.TheDiscoveryofGroundedTheory.Strategiesfor

QualitativeResearch.TransactionPublishers,Hawthorne,New-York,pp.271. Guest,G.,Bunce,A.,Johnson,L.,2006.Howmanyinterviewsareenough?An

experimentwithdatasaturationandvariability.FieldMethods18,59–582. Hendrickx,S.,ElMasry,I.,Atef,M.,Aref,N.,ElZahraaKotb,F.,ElShabacy,R.,Jobre,

Y.,2011.AManualforPractitionersinCommunity-basedAnimalHealth Outreach(caho)forHighlyPathogenicAvianInfluenza.TheInternational LivestockResearchInstituteandtheFoodandAgricultureOrganizationofthe UnitedNations,pp.77.

Hendrikx,P.,Gay,E.,Chazel,M.,Moutou,F.,Danan,C.,Richomme,C.,Boue,F., Souillard,R.,Gauchard,F.,Dufour,B.,2011.OASIS:anassessmenttoolof epidemiologicalsurveillancesystemsinanimalhealthandfoodsafety. Epidemiol.Infect.139,1486–1496.

Hoinville,L.,Alban,L.,Drewe,J.,Gibbens,J.,Gustafson,L.,Häsler,B.,Saegerman,C., Salman,M.,Stärk,K.,2013.Proposedtermsandconceptsfordescribingand evaluatinganimal-healthsurveillancesystems.Prev.Vet.Med.112,1–12. Hoischen-TaubnerS.,BieleckeA.,SundrumA.,2014.Differentperspectiveson

animalhealthandimplicationsforcommunicationbetweenstakeholders.In:

SchobertHeike,RiecherMaja-Catrin,FischerHolger,AenisThomas,Knierim Andrea(Eds.)FarmingSystemsFacingGlobalChallenges:Capacitiesand Strategies,8–16.

Johnson,N.,Lilja,N.,Ashby,J.A.,Garcia,J.A.,2004.Thepracticeofparticipatory researchandgenderanalysisinnaturalresourcemanagement.Nat.Res.Forum 28,189–200.

Kariuki,J.,Njuki,J.,2013.Usingparticipatoryimpactdiagramstoevaluatea communitydevelopmentprojectinKenya.Dev.Pract.23,90–106.

Louviere,J.J.,Hensher,D.A.,Swait,J.D.,2003.Environmentalvaluationcasestudies. In:StatedChoiceMethods:AnalysisandApplications.CambridgeUniversity Press,pp.329–353.

Mariner,J.,Hendrickx,S.,Pfeiffer,D.,Costard,S.,Knopf,L.,Okuthe,S.,Chibeu,D., Parmley,J.,Musenero,M.,Pisang,C.,2011.Integrationofparticipatory approachesintosurveillancesystems.Rev.Sci.Technol.30,653–659. Moennig,V.,2000.Introductiontoclassicalswinefever:virus,diseaseandcontrol

policy.Vet.Microbiol.73,93–102.

Mur,L.,Atzeni,M.,Martínez-López,B.,Feliziani,F.,Rolesu,S.,Sanchez-Vizcaino,J., 2014a.Thirty-five-yearpresenceofAfricanswinefeverinSardinia:history, evolutionandriskfactorsfordiseasemaintenance.Transbound.Emerg.Dis., http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12264.

Mur,L.,Martínez-López,B.,Costard,S.,delaTorre,A.,Jones,B.A.,Martínez,M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno,F.,Mu ˜noz,M.J.,Pfeiffer,D.U.,Sánchez-Vizcaíno,J.M.,2014b. ModularframeworktoassesstheriskofAfricanswinefevervirusentryinto theEuropeanUnion.BMCVet.Res.10,145.

Nitsch,M.,Waldherr,K.,Denk,E.,Griebler,U.,Marent,B.,Forster,R.,2013. Participationbydifferentstakeholdersinparticipatoryevaluationofhealth promotion:aliteraturereview.Eval.Progr.Plan.40,42–54.

Pahl-Wostl,C.,2002.Participativeandstakeholder-basedpolicydesign,evaluation andmodelingprocesses.Integr.Assess.3,3–14.

Peyre,M.,Hoinville,L.,Haesler,B.,Lindberg,A.,Bisdorff,B.,Dorea,F.,Wahlström, H.,Frössling,J.,Calba,C.,Grosbois,V.,Goutard,F.,2014.Networkanalysisof surveillancesystemevaluationattributes:awaytowardsimprovementofthe evaluationprocess.In:InternationalConferenceonAnimalHealthSurveillance (ICAHS),LaHavane,Cuba.

Pretty,J.N.,1995.Participatorylearningforsustainableagriculture.WorldDev.23, 1247–1263.

Pretty,J.N.,Guijt,I.,Thompson,J.,Scoones,I.,1995.ParticipatoryLearningand Action:ATrainer’sGuide.InternationalInstituteforEnvironmentand Development,pp.267.

Rice,M.,Franceschini,M.C.,2009.Theparticipatoryevaluationofhealthy municipalities,citiesandcommunitiesinitiativesintheAmericas.In:Health PromotionEvaluationPracticesintheAmericas.Springer,pp.221–236. Sawford,K.E.,2011.AnimalHealthSurveillanceforEarlyDetectionofEmerging

InfectiousDiseaseRisks.PhdThesis.DepartmentofMedicalScience. UniversityofCalgary,Calgary,Alberta,pp.247.

Shaik,S.,Barnett,B.J.,Coble,K.H.,Miller,J.C.,Hanson,T.,2006.Insurability conditionsandlivestockdiseaseinsurance.In:Koontz,S.R.,Hoag,D.L., Thilmany,D.D.G.,Grannis,J.W.J.L.(Eds.),TheEconomicsofLivestockDisease Insurance:Concepts,IssuesandInternationalCaseStudies.CABIPublishing, pp.53–67.

Torre,A.D.L.,Bosch,J.,Iglesias,I.,Mu ˜noz,M.,Mur,L.,Martínez-López,B.,Martínez, M.,Sánchez-Vizcaíno,J.,2013.AssessingtheriskofAfricanswinefever introductionintotheEuropeanUnionbywildboar.Transbound.Emerg.Dis.62 (3),272–279.

Tsai,P.,Scott,K.A.,Pappaioanou,M.,Gonzalez,M.C.,Keusch,G.T.,2009.Sustaining GlobalSurveillanceandResponsetoEmergingZoonoticDiseases.National AcademiesPress.