Ownership Structure, Debt, and Private Benefits in Controlled Firms

Hubert de La Bruslerie1

11/01/2011

Abstract

Controlled firms are in a framework where private benefits create a buffer between public earnings and economic profitability. We focus on debt leverage in the type II agency conflict between the controlling shareholder and outside investors. We use a simple discrete model comparing the capital ownership stake of the controlling shareholder with that of the outside investors in a framework without and with debt.

The paper highlights that debt is a governance variable, as it can moderate private benefits or, conversely, help diversion. Debt appears in some situations as a disciplinary tool in the conflict between outside and controlling shareholders. It may self-regulate the two parties involved in a control contract. The setting of joint ownership between the controlling shareholder and outside investors depends on the perceived level of private benefits. It has a connection with future earning management. The key terms of agreement between the two parties are the stakes of equity capital as wished by each one and the leverage ratio.

Keywords: private benefits, control, debt leverage, asymmetry of information, corporate governance

JEL: G30, G32, G34

1

Professor of Finance, DRM UMR CNRS, University Paris Dauphine, Place du Mal de Lattre, 75116 Paris, France. Mail :hlb@dauphine.fr. The author wants to thank P. Six for his comments.

Ownership Structure, Debt, and Private Benefits in Controlled Firms

Introduction

The literature on corporate governance places further emphasis on the economic control of the firm by a group of shareholders, the so-called "controlling shareholder". This type of corporate governance creates type II agency conflicts, as distinguished from the traditional agency problems between managers and shareholders. Private benefits appear as the cost levied by the dominant shareholder and associated with the concentration of power and control. The outside investors follow a rationale of diversifying their wealth; they are compensated by the final public profit but undoubtedly they have less access to information about the firm than controlling shareholders. Though outside shareholders have asymmetrical information, as compared with controlling shareholders, they are not precluded them from anticipating the risk of expropriation. They integrate this risk into their own assessment of the firm’s value.

The analysis of private earnings as compensation for the activity of control by dominant stockholders is not limited to legal and institutional external determinism. Here, we suppose an initial situation of control and do not question the comparative efficiency of controlling ownership and diffused ownership. A group of shareholders assumes control of the firm, and for them, the balance between private benefits and specific costs is positive. Private benefits are therefore seen as an implicit contract, the terms of which must be “agreed” upon between controlling and outside shareholders. Are there “internal” limits to the private appropriation of which outside investors are aware? We try to identify the circumstances under which self-enforcing limits on private benefits exist, focusing particularly on the role of debt. Following Jensen (1986), the disciplinary role of debt has been outlined in agency conflict, but only in the context of type I agency conflicts. Autoregulated mechanisms will rely on two observable decisions made by the dominant shareholders: their percentage of equity ownership and the debt leverage ratio of the firm.

In this article, we develop a discrete time model to identify the condition to develop self-regulating mechanisms in the agency conflict between controlling and outside shareholders. The asymmetry of information between the two agents should be acknowledged because, for

instance, private benefits are only estimated by outside investors. Debt is involved in agency conflict because it is often easier for the controlling shareholder to modify the leverage ratio than to modify his share of capital. Does debt help to expropriate value from the outside investors to the controlling ones? Alternatively, does it limit expropriation? Hereafter, we will look at the role of debt by making a distinction between the situation of a firm without debt and a leveraged firm.

Compared with Liu and Miao (2006), who use a risk-neutral approach, we take into account risk aversion and the asymmetry of information. The communication of conditioning information by the controlling shareholder is analyzed in that context. We consider forecasts of earnings to be endogenous, as outside investors are exposed to two kind of information asymmetry, regarding the eventuality of expropriation and the possibility of biased future earnings. Similar to John and Kedia (2003), this paper shows that the two problems ensuing from the concentration of power by a controlling group, one being the existence of private benefits and the other being the choice of debt structure, are linked in a framework of financial governance.

The previous literature focuses mainly on the controlling investor’s optimal behavior. Only a few papers have developed an analysis of debt and private benefits in a context of an implicit contract of control where the outside investors have to agree to invest in the firm’s equity. The outside investors are not naive and know that information may be biased. The equilibrium occurs when the two stakes of sought capital sum to one.

We highlight the interrelations between controlling and outside shareholders as well as the balance that results between them. The overarching result of the paper is that debt is also a governance variable, as it can moderate private benefits or, conversely, help diversion. The following developments will outline that, contrary to Leland and Pyle (1977), the stake of capital held by the controlling shareholder no longer is an appropriate indication of the future profitability of the economic project. We show that the perspectives of economic profitability may be strategically biased by the controlling investor to influence outside investors to invest more or less in equity capital. Self-balanced relationships between future earnings management and the expropriation of private benefits may develop in the context of the low ownership of the controlling shareholder.

We show that an asymmetry of information is necessary to get a joint ownership equilibrium between the two categories of shareholders in a private benefits context. We identify cases where there is a complementarity between the stake of capital and the appropriation rate as well as other cases where the rational is based on a substitution effect. The share of capital when crossed with the leverage ratio may signal situations in which debt has a disciplinary effect. It may also identify opposite situations where debt enhances expropriation by the controlling shareholder. The outside investors, looking at both the share of capital held by the controlling shareholder and the leverage ratio, can identify whether they stand in a disciplinary context or an expropriation-enhancing context. Debt appears in some situations as a disciplinary tool in the conflict between outside and controlling shareholders. The setting of joint ownership depends on the perceived level of private benefits. It has a connection with future earnings management, and the key parameters in achieving that equilibrium are the stake of equity capital and the leverage ratio.

We will develop a step-by-step analysis, considering first the simplest case of the absence of debt; the case for indebtedness is introduced thereafter. This paper is divided into three sections. After a review of the existing literature, the second section presents the model and describes the situation of a stylized firm without debt. Section III analyzes the more general situation of a controlled firm with debt and highlights the conditions of reaching an equilibrium with joint ownership.

1 - Review of Literature

The empirical evidence that a dispersed ownership system and protecting financial market regulations are not the only archetypes to dominate world finance was first outlined by Shleifer and Vishny (1986), La Porta et al. (1998, 1999, 2000), and Faccio et al. (2002, 2003). Corporate governance focus is now largely directed toward the analysis of the economic control of firms by a group of dominant shareholders. The economic control is different from the purely political and legal majority of voting rights, which is based on laws or external regulations. The existence of a controlling group of shareholders moves into the background the agency conflict between managers and shareholders, which was historically privileged in the literature. Managers and controlling shareholders share the same goals and have the same access to the firm’s true private economic information. They make the firm’s strategic

decisions and appropriate for themselves a part of the gross economic profit. Like managers, controlling shareholders do not have a rationale of diversification of the idiosyncratic risk on an atomized market. Both are exposed to the specific risk of the firm—precisely, the risk of failure—far more than the other investors are.

In the dominant shareholder system, private earnings are seen as a way to reward the activity of control. The appropriation of a part of the economic cash flow by the controlling shareholders may appear in large holding companies, in pyramidal groups, and in small or medium firms that open their capital to the public through IPOs (Bebchuk, 1999, Faccio et al., 2002, Claessens et al., 2002). Within industrial groups or pyramidal structures, it is easier to extract benefits using transfer pricing or “tunneling” (Johnson et al., 2000). The characteristics of the appropriation of private benefits has been empirically studied by Leuz et al. (2002), Liu et al. (2002), and Dyck and Zingales (2004). In a global comparison, Bhattacharya et al. (2003) also found the existence of private benefits among controlling shareholders. However, outside investors are aware of such opportunism and demand a higher stock return. Bhattacharya et al. insist on the opacity of the profit announced by the firm and identify a link between asymmetry and trustworthiness of information. Generally, the rationale for appropriation at the expense of outside shareholders is characterized by opacity and the absence of negotiation on what should be its optimal or "normal" level. An implicit contract defines the monitoring and control activities and evaluates the level of its remuneration from a consideration of costs and shared benefits (Hofstetter, 2006). The specific reward to controlling shareholders can be determined from the extra profit in relation to what would have resulted from a situation of an absence of control. The appropriation becomes diversion when it takes place out of the context of a contractual measure of performance. This is why legal systems consider private benefits negatively and why they try to protect outside investors (Roe, 2000, 2002). The economic legitimacy of rewarding the function of strategic control exercised by the group of dominant shareholders must be analyzed in the setting of an implicit contract with the outside shareholders who also benefit from this activity. As shown by Leland and Pyle (1977), the percentage of stake of capital own by a dominant shareholder who has control and better information is an indication of the economic profitability of the firm. The concept of “equilibrium valuation schedule” that they develop is similar to a joint implicit economic contract.

Indebtedness is traditionally seen as disciplinary in agency conflicts. The role of debt should be analyzed because it will involve third parties, such as banks or other creditors. Debt imposes limits on the behavior of controlling shareholders, and its amount is publicly known by the outside investors. This external limitation will interfere in the process of the appropriation of private earnings. The literature on the role of debt with private benefits is not extremely large. Jensen (1986) first identified the disciplinary role of debt within the traditional managers-shareholders agency conflict. The debt contract is identified as the safest security that, under any circumstances (i.e., independently of corporate laws protecting equity holders), imposes limits on the behavior of the firm. Debt is as the “safest security” for outside investors because of the asymmetry of information enjoyed by creditors (Myers and Majluf, 1984). From a theoretical point of view, a default of payment transfers the control from the borrower to the lender (Grossman and Hart, 1982 or Aghion and Bolton, 1992). Excessive debt exposes the firm to a risk of financial distress. The toughest power of negotiation of banks and other creditors imposes ex ante limits on the use of debt by managers and shareholders who will support important costs of liquidation (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994). On the other hand, the relationship between debt leverage and control is seen as being positive for managers to protect their control (Harris and Raviv, 1988) or to allow a “risk-shifting effect” (Zhang, 1998, Heinrich, 2000). Debt enhances the economic power of the controlling shareholders without modifying the structure of ownership. Debt policy has also been analyzed in the traditional manager entrenchment context. It is linked with the investment decision taken by managers who fear takeovers and want to retain power (Zwiebel, 1996). Studying the traditional agency conflict between managers and shareholders, Morellec (2004) or Lambrecht and Myers (2008) use a real-option model to link investment and debt financing decisions. They document a limitation in negative NPV investment and the setting of an optimal debt policy.

Following another approach, Harris and Raviv (1990), Zhang (1998), Filatotchev and Mickiewicz (2006), and Almeida and Wolfenzon (2006) addressed the problem of debt leverage within the controlling–outside shareholders conflict and in a context of information asymmetry. In a continuous-time setting, Liu and Miao (2006) examine the controlling shareholder’s optimal choice of capital structure. In a risk neutral and complete markets world, this decision is shown to be linked with ownership concentration and private benefits diversion. The interaction between debt and ownership structure has been analyzed in a global governance framework by John and Khedia (2003). They show that the regulation

mechanisms (i.e., manager’s incentive through stock ownership, monitored debt and takeovers) will interact. Their conclusion leads to proposals of empirical tests.

There are many empirical works concerning the relations between debt and corporate governance. Kim and Sorenson (1986), Agrawal and Mandelker (1987), and Berger, Ofeck and Yermak (1997) for American firms; Friedman et al. (2003) for Asian firms; Boubaker (2007) for French firms; and Holmen et al. (2004) for Swedish firms all find evidence of a positive relationship between debt and control. Recently, considering U.S. firms, Nielsen (2006) empirically documented a trade-off between a levered financial structure and a weak shareholding. These results suggest that debt will help in expropriation because it gives more power on economic resources. However, the conclusions are not unanimously univocal. Faccio et al. (2003) moderate the former idea. In the United States, debt seems to play an effective, disciplinary role in governance. In Europe, the companies at the bottom of a pyramid, who are seen as more vulnerable, are not particularly indebted. On the other hand, in Asia, the situation is different, with strong pressure on the firms in the pyramid. However, excessive debt leverage exposes the firm to failure, a situation where both public and private earnings for the control group are lost. Berger et al. (1997) showed that entrenched managers will use relatively less debt. Grullon et al. (2001) for American firms or Brailsford et al. (2002) for Australian firms conclude in favor of a nonlinear complex relation between control and debt, positive at the beginning but turning negative at a certain point of control. For the latter, the inside shareholders will try to avoid a loss of control linked to a risk of financial distress, so they will limit the debt ratio of the controlled firm. The category of family firms is a subset of controlled firms with specific features. Many empirical studies underline the importance of control incentives (Anderson et al., 2003, Doukas et al., 2010). Family firms prefer debt financing as a non-dilutive security.

2- Private benefits in a no-debt context

2.1 Setting of the model

We refer to a discrete model of choice. The cash flows are perpetuities. The following notations will be used:

VE: Economic assets invested at time t=0 e

r~ : Economic return on invested capital

kC: Risk-adjusted discount rate used by the controlling shareholder (in an debt context kCL) kO: Risk-adjusted discount rate used by the outside investors (kC>kO because of an underdiversification of investment by the controlling investors; in a debt context the variable is kOL)

VC: Controlling shareholder’s wealth

VO: Outside investors’ wealth (proportional to the value of the firm) i: Interest rate of the debt

D: Debt considered as perpetuities (i.D: annual amount of paid interest)

α: Stake of equity capital held by the controlling investor (It is supposed above the minimum threshold αmin giving control of the firm)

λ: Leverage ratio of the economic invested capital λ =D/VE. This is the share of economic capital financed with debt

s: Appropriation rate

The expropriation is set proportional to the economic capital VE. This setting is in line with the cost of appropriation, which is supported by the controlling shareholder. Diversion is privileged when a positive profit occurs even whether the profit return is lower than the targeted appropriation rate. In such a situation, the firm is wholly captured by the controlling shareholder. This rule ensues from a situation where the power belongs to the controlling shareholder. It is the counterparty of the cost of control supported by when building his control.

However, interest expenses are the utmost priority. They are paid proprietarily in any situation. The creditor will seize the firm and its assets in the event of a default. We assume that the debt contract is enforceable and has a better protection than the equity contract.1 From a practical point of view, courts are more effective in enforcing debt contracts because those rights are simpler to define (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Modigliani and Perotti, 2000). Action in court does not need to be initiated by multiple creditors. The legal obligation is an obligation to each creditor. If one sues the firm, the other will benefit from the result of the action. Moreover, debt financing is largely bank financing. Banks are more used to monitoring the firm and investigating their books and are more effective in claiming

repayment than small independent outside shareholders. Debt holders have the deterrent power of the bankruptcy protection, which can be, for theoretical, empirical and practical reasons, different and more effective than the outside shareholders’ protection. Therefore, the bank or the creditor knows that it is rational for the controlling shareholders to give priority to the interest payments before direct appropriation because, in a case of bankruptcy, they would lose their long-term stream of cash flow and their share of equity. The eventuality of default is taken into account in the model in the situation of an indebted firm. Finally, we do not account for taxation.2

The appropriation costs are exposed at the beginning as an investment for building a situation of control by a given blockholder. They have to be analyzed as certain and are a kind of preliminary investment to set up a situation of control and the capacity to divert private benefits. The latter are perpetuities and will last except in the event of a default of the firm. This appropriation cost C(.) derives from initial choice of α and s. The private benefits are subtracted from the raw cash flow of the firm, but after the interest expenses. This priority means that the controlling shareholder will invest in a long-term position of control and looks at long-term private benefits. He does not want to hasten a default by seizing benefits too early or by taking amounts that are too great.

The variable c

( )

α

;s corresponds to proportional annual cost of appropriation. It is the proportion of initial appropriation cost per unit of economic assets or per invested equity. In the case without debt, we haveC(

VE;α

;s)

=(VE/kC)c( )

α

;s ); in the case of an indebted firm,(

S s)

S k c( )

sC ;

α

; =( / CL).α

; . S is the amount of equity capital such that VE=S+D. As of the cost of appropriationC( )

α

;s , c( )

α

;s is a decreasing function withα

and an increasing function with s :( )

;( )

; 0; 0 , > < ≡ ∂ ∂ α α α α α α c s c s c ,( )

;( )

; 0; 0 , > > ≡ ∂ ∂ s s s s c c s s c α α .The time schedule of decisions is as follows: t=0: the firm invests in economic assets VE,

t=1: A blockholder sets up a situation of control; he buys or builds a stake of equity capital α. He determines his appropriation rate s and the firm leverage λ. He supports the appropriation cost C(.).

t=2: The outside investors considers to buy or to hold a stake (1-α) of the equity. They look at the values of α and λ. An economic contract of control is set up if they accept to hold a jointly agreed quantity (1-

α

).t=3: The economic return is observed and gives access to a perpetual cash flow.

t=4: First interests are paid (if any); then, the controlling shareholder takes his private benefits, and public earnings are displayed; the latter is then shared between shareholders according their percentage of capital.

2.2 Situation of the controlling shareholder

The uncertain nature of the economic profitability is binomial: re with a probability d

re+x with aprobability (1-d).

The value rE is positive, as x is. The target private cash-flow is VE.s. The case that is privileged in the analysis is rE <s< rE+x (case b in Table 1). In the situation where the economic return is lower than the appropriation rate, the controlling shareholder will seize all of the economic cash flow. The value of the firms becomes null for the outside investors in the market, because the net public earning are null. The controlling shareholders will first cover their private cost of appropriation (after payment of interest expenses).3

Choices d (1-d) (a) s< re < re+x

[

]

C E C E E C k c V k s r s V V = . +α

.( − ) − . (.)[

]

C E C E E C k c V k s x r s V V = . +α.( + − ) − . (.) (b) re <s< re+x[ ]

C E C E E C k c V k r V V = . − . (.)[

]

C E C E E C k c V k s x r s V V = . +α.( + − ) − . (.) (c) re < re+x < s[ ]

C E C E E C k c V k r V V = . − . (.)[

]

C E C E E C k c V k x r V V = . + − . (.)Table 1 Controlling shareholder’s payoffs – Without debt

(VE: value of the invested assets; d: probability of economic return rE, 1-d: probability of economic return rE+x; s: private appropriation rate; c(.) annualized cost of appropriation, kC: risk-adjusted cost of capital)

The situations corresponding to cases (a) and (c) are choices of level of s, which are not relevant. In the case (a), the controlling shareholder has payoffs, which are ex ante below the case (b) choice. We see that (1-α).s+ α rE <rE is always true when s<rE. In case (a), the derivatives with regard to

α

are positive in any of the two binomial states, and we get positive dE(U)/dα

. It leads to a corner solution with a full ownership by the controlling investors and, consequently, no expropriation.4 If s is designed to be in the case (c), the optimum expected value with regard to αfollows the sign of -cα. It is positive and leads toα=100%. The variables is not relevant in the setting. In both situations (a) and (c), full ownership is better than a total private appropriation s, as the former will not yield the burden of negative cost c(.). The controlling shareholder’s best solution is then to get case (a) and (c)’s payoffs being fully owner without any cost.5

The only rational choice opening the way to outside investors is the one corresponding to the (b) case. Then, a risky event may happen when the economic return is too low and yield only a return rE. The expected wealth is as follows:

[

]

C E C E E C E E C k c V k s x r s V d k r V d V E( )= . +(1− ) . +α

.( + − ) − . (.) (1)To get the optimal choice, we derive with relation to α and s, which are the two decisions variables of the controlling shareholder. Because of the uncertain cash flows, we need to consider the expected utility of a risk-averse investor. To set the choice of α, we outline the first derivative: . . ) ( ) ( ' ). 1 ( . ) ( ' . ~ ). ~ ( ' ) ( [ − − + − + − = = + − C E C E E C E C C C k c V k s x r V V U d k c V V U d d V d V U E d V U dE α α

α

α

(2)The FOC gives (see annex A):

) / )( )( ' / '' .( 1 ) / ( ) ).( ' / '' )( 1 ( ) ( 1 * 2 C E E C E E E k V s x r U U d k V s x r U U d d c s x r x − + − − + − + − + − = α α . (3)

This formula mixes terms with positive and negative signs.6 The optimal stake of capital α* should be between 0 and 1. It may have a solution in this interval, but this depends on the value of the parameters. The optimum α* is a maximum of E[U(.)], with d2E[U(.)]/dα2 being negative (see Annex A).

The derivative of α* with regard to s has the following sign (see annex A):

− − + − + − = ) / )( ' / '' ( 1 ) ( 2 . ) / )( ' / '' )( 1 ( sgn * sgn C E E C E k r x s d U U V k V U U d d c x ds dα α . (4)

The sign of this may be positive or negative.7 It identifies the two opposite rationales of entrenchment and substitution according to value of x (i.e., the perspectives of important future economic profit). If dα/ds is positive, the controlling shareholder is in a self-limitation rationale, where an increase in the capital goes with an increase in the expropriation rate. The rationale of substitution (dα/ds<0) occurs when the involvement in the firm goes along with either a larger stake of capital or through a direct private appropriation.

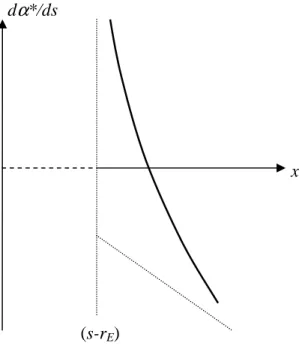

The equation (4) shows that with increasing values of the uncertain future economic profit x, the sign of the derivative dα*/ds is infinitely negative. At the point where x=(s-rE), the derivative is infinitely positive (see Figure 1). By definition of the (b) case in Table 1, only the values of x above (s-rE) should be considered.

Figure 1. Controlling shareholder’s derivative between the optimal share of capital and the appropriation rate (No debt, s: appropriation rate, rE: economic return in the low state of the world, x increase of economic return on asset in the favorable state of the world).

At the downside limit, the asymptotic positive derivative means we are in a situation of total appropriation (s=rE+x). The derivative dα*/ds is infinite. It leads to α=100%. Then, a very strong expropriation will be self-limited because the full ownership of the firm by a shareholder will result in a useless expropriation compared to ownership.8 Taking the derivative of the equation (3) with regard to x,

− − + − − + − − = ) / )( ' / ' ' ( 1 ) ( 2 . ) / )( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( ) ( sgn * sgn C E E C E E k V U U d s x r k V U U d d c s r dx d α α . (5)

Its sign is not clearly defined.9 We cannot draw clear information on the perspectives of economic profitability x from the value of α. If x stands at the lower limit of the case (b), the derivative is infinitely negative. If x is very large, the second term of the RHS is null, and the derivative is then positive. A change of sign occurs at some point. This conclusion is not in line with Leland and Pyle (1977)’s seminal article. In our very simple setting, the stake of

x d

α

*/dscapital invested by the entrepreneur or the controlling shareholder is no more a sufficient signal of the quality of the economic project. The introduction of a situation control and private benefits will trouble the expected positive relationship.

We now estimate the optimal choice of the controlling shareholder with regard to his appropriation rate s. . . ) 1 ( ) ( ' ). 1 ( . ) ( ' . ~ ). ~ ( ' ) ( [ − − − + − = = − + C s E C E C s E C C C k c V k V V U d k c V V U d ds V d V U E ds V U dE

α

(6)As a result, the optimal choice is (see annex B)

) 1 ( ) ( ) / )( ' / '' )( 1 .( 1 ) / ).( ' / '' ( ) 1 )( 1 ( * 2

α

α

α

α

− − + − − − − − = E E C E C E s r x r k V U U d k V U U d d c s . (7)The direct appropriation of private benefits by the controlling shareholder is not certain. To occur, the value s* should belong to the interval between 0 and 1. We see from (7) that the appropriation rate is an inverse function of x. A rise in the perspective of future economic profitability will lessen the appropriation rate. It means that s*, if it were observable by outside investors, would be a reliable signal of the economic perspectives of the firm. The second derivative, d2E(U)/ds2, is negative (see Annex B). The optimal setting s* is a maximum. We calculate the partial derivative at the optimum from equation (8):

− − − − − = x k V U U d d k V U U d d c d ds C E C E s ) / )( ' / '' )( 1 ( 1 ) 1 )( / )( ' / '' )( 1 ( . 2 sgn * sgn

α

α

. (8)We cannot conclude on the sign of ds*/dα.10 In a controlled and unindebted firm, the sign of the relation between α and s is undetermined. We cannot read the variation of s by following the value of the stake of capital held by the controlling shareholder. A useful signal should give valuable information regarding the behavior of the controlling investor. The variable α is an improper signal to identify either moderate or extreme situations of expropriation.

In a no-debt framework, the relationship between the stake of capital and the appropriation rate follows two possible rationales according the sign of the derivative dα/ds. A positive sign indicates a complementarity framework, and a negative one indicates a substitution scheme.

The first one signals an entrenchment effect if blockholders increase both their power through a stake of capital and private benefits. The substitution will correspond to a self-balancing effect between the two. An increase in private benefits will be balanced by a decrease in the benefits drawn by shareholding. This balancing effect may also signal an entrenchment framework. A logic of increasing private appropriation may develop behind a decrease of the stock ownership if we are in a negative ds*/dα context. A strong diversion may be hidden by a diminution of the held stake of capital.

In an unindebted firm, the stake of capital α is not a useful signal to assess the appropriation rate of the controlling shareholder. Similarly, we cannot infer anything from α about the future perspectives of profitability x.

2.3 Situation of outside investors

The outside investors have imperfect information on the uncertain future economic profitability. They receive possibly biased information from the controlling investor based on an optimistic outlook of economic returns, such as x’=x+b. The information bias is supposed to be an optimistic one (b>0).11 The outside investors are also exposed to moral hazard from the controlling investor and fear expropriation. Looking at case (b), outside investors are not certain of private benefits expropriation. They know that there is probability p for the firm to be looted. A double illusion may develop on the forecasted economic profitability of the firm and on the expropriation behavior of the controlling shareholder. Minor shareholders cannot identify the relation (7) of the controlling shareholder, who sets his expropriation rate.12 In particular, they do not know x. However, they are not naive, and they know that ds*/dx’ is negative even if x’ is biased with regard to x. This derivative is equal to -

α

/(1-α

). The outside investors know that the controlling shareholder may hide his appropriation by issuing a strong positive bias b. They are aware that the controlling shareholder is potentially a diverter and that they have biased information on the firm’s future profitability. The probability that the controller is a diverter also depends on the size of the bias: p=p(b) with dp/db<0. The controlling shareholder sets up global communication policy encompassing economic information and the image he gives regarding whether he is a diverter.The outside investors will forecast the expropriation rate with equation (7) but using x’, so s=s*’(x’). The expected value of the expropriation on the probability to be a diverter is

E(s ;x’) = p.s. The risk-adjusted discount rate of the payoffs received by the outside investors is kO. It is lower thankC because they can diversify their wealth in portfolio.

Choices d (1-d) prob non-expropriation (1-p) (b) re < re+x’

[

]

O E E O k r V V = .(1−α

).( )[

]

O E E O k x r V V = .(1−α

).( + ') prob expropriation p (b) re <s< re+x’ 0 = O V[

]

O E E O k s x r V V = .(1−α

).( + '− ) (c) re < re+x’ < s VO =0 VO =0Table 2 - Outside investors’ payoffs - Without debt

(VE: value of the invested assets; d: probability of economic return rE, 1-d: probability of economic return rE+x; s: private appropriation rate; p: probability of private appropriation by the controlling shareholder, kO: risk-adjusted cost of capital)

The equivalent for case (a) of Table 1 is not relevant here and does not appear in Table 2. The case (c) is also not relevant because if he expropriates, the controlling shareholder will support costs, which leads him to own 100% of the shares. Outside investors know that the controlling shareholder is rational and will privilege case (b) if he intends to appropriate private benefits.

The decision variable for outside investors is the stake of share they accept to buy, (1-α). The expected value is

[

]

[

]

O E E O E E O E E O k x r V d p k r V d p k s x r V d p V E ) ' ).( 1 ( . ) 1 )( 1 ( ) 1 .( ) 1 ( ) ' ).( 1 .( ) 1 ( ) ( + − − − + − − + − + − − =α

α

α

. (9)O E E O E E O E E O O O k s x r V p V U d k x r V p V U d k r V p V U d d V d V U E d V U dE ) ' ( ) ( ' ) 1 ( ) ' ( ) 1 )( ( ' ). 1 ( . ) 1 )( ( ' . ) 1 ( ~ ). ~ ( ' ) 1 ( )] ( [ − + − + + − − + − = − = − + + + −

α

α

. (10)Recalling that the variance of the expropriation rate is var(s) = s2.p.(1-p), we get the FOC solution (see Annex C):

(

( ' ) ( ( ) ') var( ))

) 1 ( ' '' ) 1 ( ' ) 1 ( ) 1 ( )* 1 ( s x s r p d ps x d k V U U ps d x d r dp E O E E + + − − − − − − − + − = −α

. (11)The numerator is positive. It has a lower value of (1-d)(rE+x’-s), which is positive in case (b). The sign of the denominator depends on (x’-ps). It means a positive investment in the firm by outside shareholders if x’, the expected economic profit, is large and the expected expropriation is low. A sufficient participation constraint is (x’-ps)>0. The invested share of capital is an inverse function of var(s), which is a measure of the (perceived) expropriation risk. The minor investors will also be pushed to invest with x’, that is, with the size of the optimistic bias in economic profitability. The question is far from simple because a discretionary bias in economic return will enhance x’ but will also lower the optimal perceived s*’ by a factor -

α

/(1-α

) and will decrease the perceived variance of s. Its global effect in (11) is unknown.If p equals 1, the value (1-α)* becomes negative if s is larger than x’ (see Annex C). It means that the threshold x’ in the expropriation rate s should not be passed if the controlling shareholder wants to attract outside investors. If we suppose that x’ is limited by rE, which means that the upside eventuality for economic return is 2rE, the value of (1-α)* is negative if the expropriation is certain.13 Such a situation means that outside investors will not hold any stocks of the firm. The sought stake of capital satisfying equation (11) becomes null once it is over values of p belonging to the interval [0,1]. We draw the conclusion that (1-α)* is decreasing with the probability of expropriation, p (and if x’>s). It is largely intuitive. If the information bias b included in x’ is large, s is low by equation (7) of the controlling

shareholder. We can define a situation where the demand for stocks is boosted if the controlling shareholder hides his private appropriation behind an optimistic economic return.

The outside shareholder’s wealth is an inverse function of the probability of expropriation.14 As a result, the controlling shareholder can play on the latter, as it is perceived by the minor shareholders. He can issue p’<p if he wants to rise the outside demand for stocks. It can be done as we know that the probability p(.) is negatively related to x by equation (7).

In a situation without any debt, the Cournot equilibrium between the supply and demand of stocks between the controlling shareholder and the outside investors is not certain and given. In a situation of moral hazard with an expropriation risk from the controlling shareholder, the way to converge is to play on the value of b, which is exogenous in the model and is in the hands of the controlling shareholder. With transparent information on rE and on the economic risk d, the variable α is not a sufficient signal. It does not help. A bias in information on the optimistic eventuality will activate a risk in appropriation, as s and thus the demand function of the outside investors can be manipulated.

Conversely, in a situation of perfect information with no expropriation and perfect transparency (s=0 and b=0), the solutions for the major and minor shareholders are strictly convergent only if they have the same cost of capital, kO=kC. It means that no diversification premium is asked by shareholders who are atomistic and who diversify their investments. Then, any shareholder will stay in the case (a) as identified in Table 1. No categories of shareholders appear, and they are all equally treated. This is the perfect atomistic shareholder paradigm. As soon as a situation of concentration of capital and control appears, kC is different from kO and (at least) an exogenous variable should be used to ensure the convergence between offer and demand of shares between the two categories of shareholders. These variables are the expropriation rate s, or the information bias b, or both. Transparency and the absence of expropriation will lead to a suboptimal setting in situations of concentrated capital and controlled firm.

The firm chooses a debt level D. We introduce here three states for the economic return before interest expenses:

re with a probability d re+x with a probability (1-d)/2 re+3x with a probability (1-d)/2.

The economic returns rE and x are positive. The private benefits are set as a percentage of the economic capital, VE.s. The interest expenses are i.D, with D being the amount of debt. Equity capital is S and is equal to VE – D. If the raw economic cash flow is lower than the interest expenses, the firm goes bankrupted, the creditor will take the assets and the shareholders have a null wealth. 0 0 ) . ~ ( 0 . ~ − < = − < ⇒ = CL E E E Er iD V r i V V

λ

(12) withλ

=D/VE et 1/λ

=1+S/D. 3.1 Controlling shareholderThe cost supported to extract private benefits is proportional to the invested assets:

(

S s)

V k c( )

sC ;

α

; =( E/ CL)α

; . The table of the payoffs identifies three cases according to the joint setting of s andλ

by the controlling shareholder. The leveraged adjusted cost of equity capital is kCL. It is larger than the fully equity-financed firm’s cost of capital kC. It is increasing with the leverage ratio. Table 3 gives the payoff for a controlling shareholder with indebtedness. In such a situation, the equity investment is not VE but only S. To assess the shareholders’ resulting wealth VCL, we need to account for leverage, which enhances the shareholders’ invested capital by a coefficient (VE/S) =VE/(VE-D)=1/(1-λ). As a result, VCL in Table 3 cannot be strictly compared to VC in Table 1. The leverage coefficient will multiply any of the VCL values in Table 3. In each cases (a), (b) or (c), when optimizing versus α or s, this coefficient has no incidence. It can be ignored in the optimization but not in the value formulas.(a) i.λ < re < s+i.λ< re+x < re +3x

[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k i r V V (.) . ) . ( . − − = λ[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k s x i r s V V (.) . ) . .( . − − + − + =λ

α

[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k s x i r s V V (.) . ) 3 . .( . − − + − + =λ

α

(b) re < i.λ < re+x< s+i.λ< re+3x CL E CL k c V V =− . (.)[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k x i r V V (.) . ) . ( . − + − = λ[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k s x i r s V V (.) . ) 3 . .( . − − + − + =λ

α

(c) re < re+x < i.λ< re+3x< s+i.λ CL E CL k c V V =− . (.) CL E CL k c V V =− . (.)[

]

CL E CL E E CL k c V k x i r V V (.) . ) 3 . ( . − + − =λ

Table 3 Controlling investor’s payoffs – With debt

(VE: value of the invested assets; d: probability of the lower economic return rE, x and 3x increase in the economic return in the moderate and the favorable states of the world; s: private appropriation rate; i: interest rate;

λ

: leverage ratio of debt D over the invested assets; c(.) annualized cost of appropriation, kC: risk-adjusted cost of capital)The two cases (a) and (b) are the result of a double decision on the expropriation rate, s, and the debt leverage,

λ

. Case (a) deals with a moderate debt level and means that no default occurs, but the outside investors face a possibility of losing their investment with a null public value of the firm (VOL=0). The debt leverage is capped by the value rE/i. There, the two payoffs, each corresponding to a probability (1-d/2), can be merged. Case (b) relies on a larger debt that yields a possibility of default for the creditors. A situation of no payment to the outside shareholders and null share value is identified. A third eventuality is distinguished with a positive payoff for both the outside and the controlling shareholders with probability (1-d/2). Case (c) occurs when a strong leverage leads to important eventualities of default where the controlling shareholder loses his invested cost of control. A high level of interest payments leads to an expropriation of raw profit only benefiting the controlling shareholder.We notice that the case (a) with debt is similar to the case (b) without (see above Table 1). The relevant case that will be analyzed later is the one with a default event, that is, rE <i.λ < rE+x < s+i.λ < rE+3x (case b). In the event of a low economic return, the firm fails because it

cannot afford the interest expenses. If the economic return is larger than this cost, the controlling shareholder looks for private appropriation. This one comes before the public earnings delivered to the shareholders. The controlling shareholder appropriates all of the net economic return if it is lower than his target appropriation rate. The firm’s value for the minor investors is then null.15

The case (c) is a nonconsistent choice. Here, the variable s appears not directly but indirectly through the appropriation cost function c(.). The expected wealth rises with

α

and declines with expropriation s. It leads to an optimal “corner” solution without minor investors and without private benefits. Then, the costs of expropriation are null, and the optimal debt ratio is (rE+3x)/i (case c, favorable eventuality). In the situation corresponding to case (c), the unique shareholder’s wealth is null in any of the three probability states.3.1.1 Case (a)

The case (a) described in Table 3 for an indebted firm is similar to the standard case of a firm without debt (case b in Table 1). We get the same results by replacing x by 2x and rE by rE-i.λ. We can merge the two eventualities resulting from middle and large economic returns:

(

)

[

]

CL E CL E E CL E E CL k c V k s x i r s V d k i r V d V E( )= . − .λ

+(1− ) . +α

.( − .λ

+2 − ) − . (.) . (13)Case (a) does not show any loss of assets due to default with regard to the creditors. We draw the conclusion that the optimal choices can be derived from the formulas of the above section. In such a situation, debt is a source of funding that reduces shareholders’ invested equity. The leverage is riskless in case (a): the economic context provides a cash flow increasing by an average value 2x and will in any of the three economic states cover the interest expenses. Debt will reduce the net profit by a certain factor -i.λ. We take the above formulas and adapt them:

) / )( 2 )( ' / '' .( 1 ) / ( ) 2 ).( ' / '' )( 1 ( ) 2 ( 2 1 * 2 CL E E CL E E E k V s i x r U U d k V s i x r U U d d c s i x r x − − + − − − + − + − − + − = λ λ λ α α . (14) From (4),

− − − + − + − = ) / )( ' / ' ' ( 1 ) 2 ( 2 . ) / )( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( 2 sgn * sgn CL E E CL E k r x i s dU U V k V U U d d c x ds d λ α α . (15)

The relevant interval for values of x is limited downside by 2x>(s-rE+i

λ

). Equation (15) defines a decreasing relationship similar to Figure 1. The conclusion is the same: we cannot separate the two rationales of complementarity and substitution between private benefits and explicit capital shareholding. The derivative is decreasing with x. It changes value from a positive derivative to a negative derivative. A result similar to (5) holds. Following the displayedα

*, we cannot infer anything on the firm’s future profitability from it. The derivative of kCL with regard to λ, kCL/λ, is positive. We recall that the derivative cα is negative. − − + − − − + − − + − + − = ) )( ' / ' ' .( ) 2 ( ) )( ' / ' ' .( . ) ).( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( . ) )( 2 ).( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( 2 . . 2 sgn * sgn , / E CL E E CL E CL E E CL V U U d k s i x r V U U d k i V U U d d k c V s i x r U U d d i k c xi d d λ λ α α λ λ λ α . (16)

The derivative of α* with regard to λ has an undetermined sign.16 Debt will favor block ownership by the controlling shareholder in some cases and will not in other cases. For values of the upside potential of economic return x above (s-rE+i

λ

), the derivative dα

/dλ

is strictly decreasing from +∞ to -∞. It is decreasing for lower values of x (see Figure 2). However, we cannot say that it starts from a positive sign or a negative sign. The rationale between debt and capital shareholding balances between complementarity (positive sign) and substitution (negative derivative) from the controlling shareholder’s point of view.When the controlling shareholder is not certain of covering the sum of interest expenses and his appropriation (x below s-rE+i

λ

), he will refrain from holding stock and favor debt. The substitution effect is strong. When the situation is certain, he will maximize his wealth by both sides: appropriation and public earnings. As a result, a complementary phase appears. In the end, when the economic return is very high, high debt will discourage stock holding.Figure 2 Controlling shareholder’s derivative between the optimal share of capital and the leverage ratio

(With debt; case (a) choices; s: appropriation rate, rE: economic return in the low state of the world, x increase of economic return on asset in the favorable state of the world)

We analyze the derivative versus the expropriation rate (adapted from equation 7):

) 1 ( ) ( ) 2 ( ) / )( ' / '' )( 1 .( 1 ) / ).( ' / ' ' ( ) 1 )( 1 ( * 2

α

λ

λ

α

α

α

− − − − + − − − − − = i r i x r k V U U d k V U U d d c s E E CL E CL E s . (17)The first term of s* is negative, the second is positive and the third is undetermined:

i V U U d k V U U d d k c d ds E CL E CL s − − − − = ) )( ' / '' .( ) ).( ' / '' )( 1 )( 1 ( . * /λ /λ α λ . (18)

The derivative at the optimal point s* shows an undetermined sign.17 If we suppose that we are in a context similar to the Modigliani-Miller (M-M) proposition II, we have a formalized

x d

α

*/dλ

>0(s-rE+i

λ

) dα

*/dλ

<0hierarchy between the cost of equity capital with and without debt.18 So, the derivative of the adjusted cost of capital is

) ( 1 1 ) ( , k i k i S V d dk k C C E CL CL − − = − = = λ λ λ . (19)

When α = 100%, the first term of (18) is positively infinite. The debt leverage is positively linked with private benefits, evidencing an infinite positive derivative. It means that, in a full 100% ownership (which means s=0), a small increase in debt sharply drives up the expropriation ratio. At this end, it signals expropriation for a fully held firm, which is contradictory. However, with shared ownership, the sign of the derivative may change. As a result, the leverage signal may correspond to another rationale. Leverage is a good signal on expropriation only when the firm is fully held. Otherwise, we cannot infer expropriation behaviors from the debt ratio.

With a very limited debt, the sign of the relationship is unknown. We cannot say anything looking at α or λ. This case is out of the scope of a default. Debt does not help in signaling, and we saw in the previous section that the ownership stake is no more a sound signal related to private benefits.

3.1.2 Case (b)

When looking at case (b), we acknowledge a probability of default, which is d. We recall that to get the controlling shareholder wealth comparable to the situation without any debt, we have to enhance the value VCL by a factor (VE/S) = 1/(1-λ). This coefficient can be ignored when calculating the FOC versus α or s.

The expected value is

[

]

[

]

− − + − + − + + − − = CL E CL E E CL E E CL k c V k s x i r s V d k x i r V d V E . .( 3 ) . (.) 2 ) 1 ( 2 1 ) ( λ α λ . (20) − − + − − + − − + − = + + + − CL E CL E E CL E CL E CL k c V k s x i r V V U d k c V V U d k c V V dU d V U dE α α α

λ

α

( 3 ) . ) ( ' 2 ) 1 ( . ) ( ' 2 ) 1 ( . ) ( ' ) ( [ . (21)The first-order condition gives (see Annex D)

(

)

) / )( 3 )( ' / '' ).( 1 ( 2 ) / ( ) 3 ).( ' / '' )( 1 )( 1 ( . 4 ) 3 )( 1 ( ) 1 ( ) )( 1 ( 2 1 * 2 CL E E CL E E E E k V s x i r U U d k V s x i r U U d d c s x i r d s d x i r d − + − + − − + − − + + − + − + + − + − − =λ

λ

λ

λ

α

α . (22)This value is a maximum for E[U(.)] because d2E[U(.)]/dα2 has same sign as –cαα,, which is

negative (see Annex D). The first term of (22) is negative (see Table 3- Case b). The two others are positive. The condition to get admissible shareholding (i.e., between 0 and 100%) depends on d. Ownership is decreasing with d, which makes sense. The sign of d

α

/dx is unclear. The stake of capitalα

* does not issue a sound signal regarding economic profitability.When calculating the partial derivative at optimum of

α

* vs. s, we get(

)

(

)

. ) / )( ' / ' ' ( 2 ) 3 ( 2 . ) / )( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( . 4 ) 1 ( ) )( 1 ( ) 3 )( 1 ( 2 1 sgn * sgn − − + − − + + − + − − + − + − + − = CL E E CL E E E k V U U s x i r k V U U d c s d x i r d s x i r d ds d λ λ λ α α . (23)The first term is negative (recalling that (rE-iλ+x) <s). The second term is positive (cα and

U’’negative). The third is positive. The sign of dα*/ds is unknown and depends on the relative positions of s and x. We have by definition of case (b), 2x>(s-rE+i

λ

). For values of x satisfying the condition, it gives a decreasing relationship similar to Figure 1. We cannot separate the two rationales for complementarity or substitution between private benefits andexplicit capital shareholding. The stake of capital is not a clear signal of expropriation. However, for high values of x, it involves an infinitely negative substitution signal.

Figure 3 Controlling shareholder’s derivative between the optimal share of capital and the appropriation rate (with debt, s: appropriation rate, rE: economic return in the low state of the world, x increase of economic return on assets in the moderate/favorable states of the world)

The partial derivative vs. λ is taken from (23):

(

)

[

]

− − + − − + − + − − + − − + = ) )( ' / ' ' ( . 2 ) 3 ( ) )( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( . 2 . . . 4 ) 3 ( 2 . ) )( ' / ' ' )( 1 ( . . 4 ) 1 ( ) 1 ( 2 1 sgn * sgn , 2 , E CL E E CL E E CL V U U k s x i r V U U d i k c s x i r V U U d k c i d i d d ds d λ α λ α λ λ λ α . (24)The second term has a denominator kCL,λ>0 and is positive. The three other terms are positive. We get the conclusion that in any case, debt will enhance the rational of complementarity or substitution between the stake of capital of the controlling shareholder and expropriation.

x d

α

*/dsDebt is a device tool in the rationale of expropriation. According to situations, it strengthens the rationale of complementarity, and in others, it moderates the substitution effect. We cannot assess whether it is per se a disciplinary tool.

Calculating the optimal choice versus s gives

− − − − = = CL s E CL E CL s E CL s E CL CL CL k c V k V k c V k c V V U E ds V d V U E ds V U dE (1 ) . , . , . ). ( ' ~ ). ~ ( ' ) ( [

α

. (25)The FOC is (see Annex D)

(

)

) 1 )( 1 ( ) )( 1 ( ) 3 ( ) 1 ( ) / )( 1 )( ' / '' ).( 1 ( 2 ) / ( ) 1 ).( ' / '' )( 1 )( 1 ( 4 * 2 α λ λ α α α − + + − − − + − + − − + − − − + = d x i r d x i r d k V U U d k V U U d d c s E E Cl E Cl E s . (26)Recalling that cs>0, the first term is negative. The second is positive, and the third has unknown sign. The value s* is a maximum. It may lie in the interval [0,1]. The full appropriation is not surely the optimal one. The derivative of s* vs. x depend on the sign of (1-3

α

). If his stake of capital is below 33%, the controlling shareholder will experience a positive ds*/dx. It means that he will seize more private benefits. To hide his expropriation, he may then lower the perspective of economic profitability x. This relationship means that earning management and expropriation are linked with a self-balanced effect. If the controlling shareholder exaggerates the future profitability by issuing an optimistic value of x’, the calculated value of his appropriation rate will be inflated. Then, the size and also the probability of appropriation as assessed by outside investors will rise. It will lead them to lower their investment (see below). As a result, a substitution mechanism develops between earning management and appropriation in case of limited ownership of the controlling shareholder.If the controlling shareholder holds more than 33% of the capital, the sign of the derivative is negative. He accepts being paid mostly with public profit. Because of the cost of appropriation, he will prefer to get direct earnings, and good profitability will discourage diversion. To hide diversion from others, he may then boost the announced economic profitability. Then, earnings management and appropriation will go in the same direction, as

optimistic economic return will lower the perceived value of the appropriation rate. As a consequence, the sign of the communication policy and of the bias may change. In certain circumstances, that is, with a block ownership below 33%, a negative information bias may eventually occur.

The paradoxical conclusion of the previous analysis is that x is a signal of the appropriation rate of the controlling investor. However, this signal differs according the threshold percentage of 33% of capital. Below that stake, it will induce increasing appropriation with increasing economic perspectives x. Above that limit, it will mean lower appropriation with increasing economic perspectives.

The derivative of s* versus the probability of default d is negative in case (b)19. This point is important and introduces a disciplinary effect of debt through the probability of default. Calculating the partial derivative of appropriation with regard to the debt ratio (see Annex D) gives

(

)

) 1 )( 1 ( ) 1 ( ) 1 ( ) )( 1 )( ' / '' ).( 1 ( 2 ) ( ) 1 ).( ' / '' )( 1 )( 1 ( 4 * , 2 ,α

α

α

α

λ

λ λ − + + − − − − + − − − + = d d d i V U U d k V U U d d k c d ds E CL E CL s . (27a)In the M-M proposition II context, the leveraged equity cost of capital kCL depends on the difference (rE - i).

(

)

) 1 )( 1 ( ) 1 ( ) 1 ( ) )( 1 )( ' / ' ' ).( 1 ( ) ( 1 1 2 ) ( ) 1 ).( ' / '' )( 1 )( 1 ( ) ( 1 1 4 * 2α

α

α

λ

α

λ

λ

− + + − − − − + − − − − − + − − = d d d i V U U d i r V U U d d i r c d ds E E E E s . (27b)Assuming a cost of equity capital following the M-M proposition II, the first term has positive sign.20 The second is negative, and the sign of the third term depends on

α

. For α=100%, the sign of the derivative is positive and becomes infinite. A condition for the third term to be negative isα

<(1-d)/(1+d). The disciplinary effect of debt will depend on the sign andmagnitude of the third term. When α is equal to zero, the derivative may be positive or negative according to the magnitude of the first term. A rationale of self-limitation of expropriation may develop for low equity stake of the controlling shareholder. Then indebtedness may limit private appropriation. From (27), we see that there is a value of α canceling the ds*/dλ derivative to zero. The rationale of self-limitation of expropriation with debt fades away above a given value of α. This value may not be in the interval of a 0 to 100% stake of capital. + − − + − − − − = i V U U i r V U U d d i r c dd d ds E E E E s 2 ) )( ' / '' ( ) ( 1 1 2 ) )( 1 ).( ' / ' ' ( ) 1 ( ) 2 )( ( 1 1 4 sgn * sgn 2

λ

α

λ

λ

. (28)The sign of d2s*/d