Cyberspace and the Seas: Lessons to be Learned

by Raymond K. Joe

B.S., Humanities and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 M.Sc., Sea-Use Law, Economics, and Policy-Making London School of Economics and Political Science, 1993

S.M., Technology and Policy Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

JUN 21 1999

LIBRARIES

9%n

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF OCEAN ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OCEAN SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 1998

C 1998 Raymond K. Joe. All rights reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies

of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author: ...

Certified by: ...

PrAccepted by:...

A ccepted by: ...

Department of Ocean Ei eering August 21, 1998

J. D. Nyhart f an Engineering and Management Thesis Advisor

/ J. Kim Vandiver

Professor of Ocean Engineering Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies

Cyberspace and the Seas: Lessons to be Learned

byRaymond K. Joe

Submitted to the Department of Ocean Engineering on August 21, 1994 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in

Ocean Systems Management

ABSTRACT

With computer science technology and the Information Superhighway, or cyberspace, developing rapidly, information services and resources are playing an increasingly fundamental role in everyday life. The question of rights over information is

correspondingly becoming more complicated as well. Regulation over cyberspace is inconsistent, and continues to develop in piecemeal fashion, while the debate remains unsettled whether cyberspace should be regulated at all. Currently no overall legal design for cyberspace is in view. Meanwhile, recent studies report that self-regulation in

cyberspace has failed to protect even basic rights of privacy with respect to information. An investigation was made to evaluate the 1983 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as a prototype for a cyberspace legal regime. The provisions for the high seas were found to be readily adaptable for parallel rules for cyberspace. Likewise, the Part XI provisions concerning the deep sea bed, provided for a very detailed organizational

framework from which an international and coordinated management of information transactions in cyberspace may be pursued. The detailed provisions regarding settlement dispute were almost directly applicable to cyberspace, with little if any modification. A cyberspace legal regime modeled from the Law of the Sea would eliminate some of the jurisdiction, accountability, and enforcement difficulties of Internet regulation.

Thesis Supervisor: J. D. Nyhart

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In tro d u ctio n ... 6

I. Developing a Context: International Law, the High Seas, and Cyberspace... 11

II. Private International Laws of the Sea and Electronic Trade... ... 15

III. The Public International Law of the Sea... 22

IV. Reconfiguring the Law of the Sea for Cyberspace ... ... 28

General Provisions ... ... ... 28

Article 87. Freedom of the Internet... 28

Article 88. Reservation of the Internet for Peaceful Purposes ... ... 29

Article 89. Invalidity of Sovereignty over the Internet... ... 29

Article 91A. Nationality of Cybernauts ... ... 30

Article 91B. Nationality of Virtual Sites ... ... 30

Article 92A. Status of Cybernauts... ... 30

Article 92B. Status of Virtual Sites... 30

Article 94. Duties of the Virtual Nationality State... ... 31

Article 97. Penal Jurisdiction in Matters of Internet Incidents... ... 33

Article 27. Criminal Jurisdiction over Foreign Virtual Sites ... 34

Article 100. Duty to Cooperate in the Repression of Piracy ... 35

Article 101. Definition of Piracy... ... 35

Article 103. Definition of a Pirating System ... 36

Article 105. Seizure of a Pirating System... 36

Article 106. Liability for Seizure Without Adequate Grounds ... 36

Article 117/118. Duty of States to Cooperate and to Adopt with respect to their Nationals Measures for the Management of Cyberspace Resources ... 37

Part XI. Section 2. Principles Governing Cyberspace ... 38

Article 137. Legal Status of Cyberspace ... ... 38

Article 138. General Conduct of States in Relation to Cyberspace ... 38

Article 139. Responsibility to Ensure Compliance and Liability for Damage ... 38

Article 140. Benefit of M ankind... ... 39

Article 141. Use of Cyberspace Exclusively for Peaceful Purposes... .39

Article 142. Rights and Legitimate Interests of States ... ... 39

Article 144. Transfer of Technology... 39

Article 145. Protection of the Virtual Environment ... ... 40

Article 147. Accommodation of Activities in Cyberspace and in the Virtual Environment .40 Article 148. Participation of Developing States in Activities in Cyberspace... 40

Article Al. Costs To States Parties And Institutional Arrangements ... 41

Section 4. The International Cyberspace Authority ... ... 44

Subsection A . General Provisions ... 44 __

Article 156. Establishment of the International Cyberspace Authority... 44

Article 157. Nature and Fundamental Principles of the ICA... 44

Article 158. Organs of the ICA ... 44

Subsection B. The Assembly... ... 45

Article 159. Composition, Procedure and Voting ... 45

Article 160. Powers and Functions ... 46

Article A9. The Finance Committee... 47

Subsection C. The Council... ... 49

Article 161. Composition, Procedure and Voting ... ... 49

Article A3. Decision-M aking ... ... ... 51

Article 162. Powers and Functions... ... 53

Article 163. Organs of the Council... ... 55

Article 164. The Economic Planning Commission ... ... 56

Article 165. The Legal and Technical Commission... ... ... 56

Subsection D. The Secretariat ... 58

A rticle 166. The Secretariat ... ... 58

Article. 167 The Staff of the ICA ... 58

Article 168. International Character of the Secretariat ... ... 59

Article 169. Consultation and Cooperation with International and Non-Governmental Organizations... 59

Subsection F. Financial Arrangements Of The Authority ... 60

Article 171. Funds of the ICA ... ... ... 60

Article 172. Annual Budget of the ICA ... ... 60

Article 173. Expenses of the ICA ... ... 60

Article 174. Borrowing Power of the ICA ... ... 61

A rticle 175. A nnual A udit ... 61

Subsection G. Legal Status, Privileges And Immunities ... ... 61

Article 176. Legal Status... 61

Article 177. Privileges and Immunities ... 61

Article 178. Immunity from Legal Process ... 61

Article 179. Immunity from Search and Any Form of Seizure ... 62

Article 180. Exemption from Restrictions, Regulations, Controls and Moratoria ... 62

Article 181. Archives and Official Communications of the ICA ... 62

Article 182. Privileges and Immunities of Certain Persons Connected with the ICA... 62

Article 183. Exemption from Taxes and Customs Duties... ... 63

Subsection H. Suspension of the Exercise of Rights and Privileges of Members ... 63

Article 184. Suspension of the Exercise of Voting Rights... ... 63

Article 185. Suspension of Exercise of Rights and Privileges of Membership ... 63

Section 5. Settlement Of Disputes And Advisory Opinions ... 64

Article 186. Cyberspace Disputes Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of Cyberspace ... 64

Article 187. Jurisdiction of the CDC of the International Tribunal for the Law of C yb ersp ace ... ... 6 4 Article 188. Submission of Disputes to a Special Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of Cyberspace or an Ad Hoc Chamber of the CDC or to Binding Commercial Arbitration ... ... 65

Article 189. Limitation on Jurisdiction with Regard to Decisions of the ICA... 66

Article 190. Participation and Appearance of Sponsoring States Parties in Proceedings ... ... ... 66

Article 191. Advisory Opinions... 67 __ I

Part XV. Settlement of Disputes... ... 67

Article 287. Choice of procedure ... ... 67

Article 288. Jurisdiction ... 68

Article 290. Provisional measures... ... 68

Article 292. Prompt release of virtual sites and personnel ... ... 69

Article 297. Limitations on applicability of section 2 ... 69

Part XVI. General Provisions ... ... 70

Annex V . Conciliation ... ... 71

Annex VI. The International Tribunal for the Law of Cyberspace... 71

Article 14. Cyberspace Disputes Chamber ... ... 71

Article 19. Expenses of the Tribunal... 71

Article 25. Provisional measures... 71

Annex VII. Arbitration... ... ... 72

Annex VIII. Special Arbitration ... ... 72

Article 1. Institution of proceedings ... 72

Article 2. Lists of experts... 72

Article 5. Fact finding ... 72

V. The Proposed Legal Regime... ... ... 73

CONCLUSION... ... ... 79

Appendix A. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Part XV... 85

Appendix B. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Part XVI ... 95

Appendix C. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Annex V... . 97

Appendix D. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Annex VI ... 101

Appendix E. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Annex VII ... 113

INTRODUCTION

While law enables both the development of new technologies and their adoption by the public, the development of law generally lags behind technological progress. Internet law is no exception. In a very short period, the Internet has radically changed the way people communicate and function, both personally and professionally. To utilize and benefit better from the information superhighway, we must be able and willing to accommodate legally the changes brought by this fast-rising technology.

This paper attempts to examine security issues and law in cyberspace by looking to what is arguably the first global frontier, the high seas. The electronic frontier, though likened by some early enthusiasts to the "lawless" "Wild West" of American legend, is today more aptly compared to the high seas. Each has provided a means to close the isolating, geographic gaps between lands. For centuries, global information exchange was a primary function of the high seas. Functionally, the Internet has redefined the

boundaries of human interaction, specifically with respect to information communication. Like cyberspace, the high seas are a global commons. Both commons house great, global resources. Both exist outside of national jurisdictions. Both even have been plagued by cruising pirates.

In cyberspace, distance and physical barriers are effectively meaningless. When a computer network user-or, simply, user, or cybernaut-logs in to the Internet, (s)he becomes part of a network that extends globally with computers in perhaps the next room and in another country. A network is any group of people connected by computers to share information.2 The Internet is an interconnection of thousands of separate networks worldwide. It was developed by the US Federal government to link government agencies along with colleges and universities and has expanded to include thousands of companies

1 Churchill, R. R. and A. V. Lowe, The Law of the Sea, Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK, 1988: 2.

2 Unisys. "Information Superhighway Driver's Manual." URL: <http://www.unisys.com/Oflnterest/Highway/highway.html>.

and millions of individuals.3 The Internet is the working framework from which the Information Superhighway, or I-Way, has developed and continues to develop. Another term for the I-Way, coined in 1984 by William Gibson in his science fiction novel, Neuromancer, is cyberspace. We use it here to refer to the network of electronic computer networks that is fast becoming more and more a part of all our activities and interactions in the physical world, from providing the latest stock market figures to providing a means for family members to stay in contact over great physical distances. Finally, the term "virtual" is used in this paper to refer to the electronic environment configured by cyberspace in which we, through computers, visualize, manipulate, and interact with the information we are exchanging.4

Though, we may be far from realizing Gibson's Neuromancer world, in 1997, information technology (IT) was responsible for more than one-quarter of the United States' total real economic growth in each of the last 5 years; the overall inflation rate would have been 3.1 percent but growth in IT lowered it to 2.0; meanwhile, total

corporate investment in IT rose to 45 percent.5 Cyberspace is a developing vision for the future of the Internet, to extend its public availability to each individual home, to enable

electronic commerce, to provide health and medical information, to order take-out

restaurant food-the list is unbounded. We construct virtual mailboxes for our electronic correspondences, virtual classrooms for online education, virtual stores from which to shop, and virtual space in which to expand our electronic visions. Though almost

nonexistent five years ago, network commercialization includes personalized news report subscriptions, retail consumer goods and services, as well as database information

resources. As with physical goods, the value of information and information-based products and services changes depending on environment, region, or country.

3 Id.

4 Isdale, Jerry. "What is Virtual Reality? A Homebrew Introduction and Information Resource List." Version 2.1, Oct. 8, 1993. URL: <ftp://sunee.uwaterloo.ca/pub/vr/documents/whatisvr.txt>.

5 The Emerging Digital Economy, Chapter 1 The Digital Revolution, The United States Department of Commerce. URL: <http://www.ecommerce.gov/digital.htm>.

With the growth of electronic trade, consumers have been calling for regulation.6 Regulation, however, is complicated because it conflicts with the laissez-faire philosophy embraced by users at the Internet's inception. The laissez-faire principle that

characterized the formation of the Internet is reflected in the Internet's technological configuration of networks, the management of which has been decentralized, with little or no monitoring of information exchange. Without such monitoring, safeguarding

information from wrongful appropriation or use has been problematic. Regulation is further complicated by Internet technology itself. Who, for example, has property rights to what would be regarded in physical form as personal information when that information is created, transmitted, and stored electronically and access to it is only possible by

physical machines, computers and terminals that may not be owned by the person in question?7

To illustrate this further, consider perhaps the most pervasive use-to-date of the Internet: electronic mail, or email. Like the telephone before it, email has become a

standard means of communication. Email in fact is often a substitute for the telephone and, though their technologies are not the same, many parallels may be drawn: both

communicate information without a physical rendering or "hard copy"; both allow for real time exchange of information and information response; both can store information for later reproduction or re-transmission, etc. Legally, email has raised the issues of ownership and right to privacy. Through ownership of the computer hardware-databases and terminals--by which email messages are received and stored, private

companies are claiming proprietary ownership rights over email messages received by their employees. Through this ownership claim, some companies forbid personal email

messages, ostensibly to conserve computer resources, and employees are made aware that email messages are not secure or confidential.

6 Federal Trade Commission, "Conclusions," Online Privacy: A Report to Congress, June 1998. URL: <http://www.ftc.gov/reports/privacy3/conclu.htm>.

7 Branscomb, Anne Wells. "Chapter 5: Who Owns Your Electronic Messages?" Who Owns Information? From Privacy to Public Access.... New York: Basic Books, 1994: 92-103.

This claim goes against established conceptions of ownership and privacy in communications prior to the Internet. While a company might discourage personal telephone calls during regular business hours, an outright ban would likely be considered intolerable as unreasonable intrusion. Consider, for example, telephone calls, and email exchanges, after working hours. Ownership of office telephones and transmission cables are not recognized as a basis for ownership of the telephone conversations transmitted. Nor does infrastructure ownership automatically allow monitoring or intrusion into telephone conversations or telephone messages recorded on answering machines. The right to privacy on the telephone may be defended by an expectation of privacy in one's telephone conversations. This argument is nullified perhaps with respect to email, by corporate declarations to employees that email is neither a secure nor confidential means of communication. The controversy, however, does not end there: employees continue to claim and object to privacy invasion; conferences and political action movements continue to be mounted as well.

The telephone example illustrates that physical world analogues do exist for electronic scenarios. Moreover, discrepancies in a person's rights between the two environments are confusing, contentious, and counterproductive. Security issues involve privacy, property, and jurisdiction rights. Existing laws must be analyzed for their physical context in order to adapt or abandon them for cyberspace. Should, for example, national jurisdictions be recognized in any way at all? Likewise, while the appropriateness of property law for cyberspace may be clear in principle, the application of physically based definitions of property is not. We must be willing and able to create new legal constructs where our physically based ones are inapplicable. At the same time, the nonphysical nature of cyberspace is not in itself a justification to overturn settled questions of law; whenever it is contextually appropriate, the law of the physical world must be regarded at least as quasi-precedent in cyberspace. In other words, the efficient development and adoption of Internet law requires an engineering of sorts to extend our laws into cyberspace.

This paper suggests that the high seas provide a useful prototype towards that end, focusing on cyberspace security issues. Part I develops a context for discussion of

international law, the high seas, and cyberspace. Part II reviews the state of private international law with respect to high seas trade, identifying accountability and

enforcement as key issues for the developing utilization of the Internet for high seas trade, and electronic commerce in general. Part III discusses the public international legal regime for the high seas regime, its development, and specific provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOS) that may be useful for the development of cyberspace law. Part IV proposes a reconfiguration of the LOS to arrive at a regime for cyberspace law. Part V is a discussion of this reconfiguration before concluding with some general observations and recommendations.

I. Developing a Context: International Law, the High Seas, and Cyberspace

Natural law, orjus naturale, was widely held, by the Roman jurists of the Antonine age, to be rules that are rooted in man's nature, or the entirety of his mental, moral, and physical constitution.s As such, natural law exists whether or not it is

incorporated by a system of enacted law or State practice. According to the

intellectualism of the Renaissance and Reformation, natural law was deduced by rational intelligence, and considered of greater importance than State practice which may be characterized as the "voluntary law of nations."'

International law in general was reasoned to be based on principles of natural law. Likewise, freedom of the high seas was reasoned to be a natural right of man. In his Mare Liberum, Hugo Grotius, commonly regarded as the father of modern international law, drew on reasoned laws of nature to uphold the doctrine of the freedom of the seas against Portuguese claims to monopoly over trade in the Far East.10 Until the end of the 19t

century, the high seas were open to free and unrestricted use to all. The seas in general were largely subject to a laissez-faire regime, which allowed the then dominant European powers to pursue their main maritime interests in communication with their colonies and seaborne trade. 1"

Like the seas, communication is the fundamental facet of the information

superhighway. Advocate calls to maintain a libertarian cyberspace are remindful of long-held arguments for the freedom of the high seas as a natural right of man. The new freedoms of communication that underlie the innovation, or revolution, brought by the Internet have been based on a laissez-faire access. Early cybernauts made laissez-faire a working credo of the Internet. They imagined a space of unhampered freedom,

8 "Natural law," Black's Law Dictionary, 6th edition, West Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minn., 1991.

9 Churchill supra note 1 at 3. 10 Id.

11 Id. at 2.

unrestricted by government and unencumbered by laws. From this pioneer mentality grew the Internet expressions "the electronic frontier," "the information superhighway," and

"surfing the net." These images are drawn from the folklore of the untamed American

Wild West, of the open road or road-tripping mobility, and from surf culture, a modern derivative of sailing freely on the high seas.

While maritime trade on the high seas fostered a laissez-faire regime, the growth of electronic trade has promoted electronic security concerns that have spurred the Internet towards regulation. But the 20th century has also moved the law of the high seas towards regulation. Modern technologies have dramatically changed the use of the sea: the modern supertanker created a global, marine environmental pollution hazard; the continental shelf has became readily accessible and exploitable for its resources; trawlers and distant-water fishing fleets, including on-board processing plants, have jeopardized fisheries that before were considered inexhaustible. As a result, laws for the seas have developed following a more functional rather than strictly jurisdictional course.12 This

functionality has often taken the form of legal protections to ensure the preservation of the seas and all of its uses.

The 20th century also brought changes in the treatment of international law, including law for the seas. With the rise of political theories against absolute monarchies, international law became viewed more as voluntary obligations that States actually assumed rather than rationalized, absolute ideas about what States should or must do, regardless of their will.'13 As a reflection of this, Article 38 of the Statute of the

International Court of Justice directs the Court to apply international conventions, as well as international customary law, in deciding international disputes brought before it.14

12 Id. 13 Id. at 4. 14 Id.

An international convention establishes explicit rules that allow modification of duties and/or responsibilities of customary law; also known as a treaty, an international convention only binds those States that are parties to the treaty. An international convention often requires ratification, in addition to signature, by State parties; a multilateral convention may require a minimum number of ratifying States before the treaty enters into force. International convention and international customary law overlap where convention provisions embody customary law. International conventions and international customary law also overlap where convention provisions pass into customary law. Such provisions thus become binding on States that are not party to the convention but that act in manner evidencing belief that the rule at issue represents customary law.

Formally, two elements are required for a showing of international customary law: first, a general, consistent practice adopted by States; second, opiniojuris,15 a conviction

that the practice is either required or allowed by customary international law. Opiniojuris prevents 'rules' of comity from becoming rules of law. For example, red carpets for visiting heads of State or restraint in enforcing coastal State laws against foreign ships

passing through territorial waters both satisfy the first requirement and not the second. By contrast, continental shelf rights passed into customary law due to many State claims and the general belief that those claims are permissible in international law. In principle, international customary law is binding on all States. There is a presumption that States have assented, or consented, to that which States in general have assented. However, like rights created by convention, State consent ultimately determines State obligation;

customary law is binding unless a State can show that it is a persistent objector to the customary law at issue. In fact, a State is also bound by a rule that is not generally accepted if that State has consented to that rule.

The continued movement towards rigor in modern international law is evidenced today by the growth in importance and effectiveness of the United Nations (UN). This 15 Id. at 5-6.

increased UN significance was arguably heralded by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOS). The LOS represents over 14 years of work'6 and has been

described as "a monument to international co-operation ... [for which] the international community expressed its collective will ... on a scale the magnitude of which was unprecedented in treaty history."17

Such international cooperation and collective action is required to secure the Internet for electronic commerce. Technologically, continued advances should enable the Internet to provide faster access to more and more information at lower costs. This progress, however, has already resulted in a proliferation of incompatible network

systems. The Internet is developing not toward a unified space but toward a virtual chaos. If this continues, the costs of overcoming communication barriers may exceed the benefits of virtual participation. Individual entities-companies-may benefit greatly from this confusion but development of cyberspace itself would suffer. In a competitive

environment in which multiple actors participate in non-compatible ways, uniformity is typically achieved either by one player emerging as dominant-as did Microsoft-Intel and IBM-compatible personal computers-or by the creation of a public standard-such as the 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone. If one should prove more efficient or profitable than the others, a dominant data standard or network configuration could very well emerge from the chaos to satisfy compatibility concerns. However, competing national sovereignties, and the possibility of virtual escape from any or all of them, suggest that any legal guarantees in cyberspace will likely need to be created.'8

16

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. xix.

17 Id.

8 See "Conclusions," Online Privacy: A Report to Congress, Federal Trade Commission, June 1998.

URL: <http://www.ftc.gov/reports/privacy3/conclu.htm>. See also "LEAVING INDUSTRY TO

"REGULATE" ITSELF WILL WORSEN PRIVACY INVASIONS, EXPERTS SAY," Washington, DC, June 22, 1998. URL: <http://wwwjunkbusters.com/ht/en/nrlO.html>.

II. Private International Laws of the Sea and Electronic Trade

International law may be divided into two categories: public and private. Private international laws are concerned with individual entities, such as a citizen or a corporation. One example of private international law would be the treaties and customs by which countries recognize another country's passport and the treatment afforded foreign passport holders. Another example is the set of rules and regulations to which an individual is subject when conducting trade internationally. Electronic commerce has created security issues that are not unlike fundamentally those which have concerned international shippers since seaborne trade began. In fact, the methods that seaborne trade has used to answer security concerns on the high seas may be applied to electronic trade in cyberspace.

It is not surprising, therefore, that there has already been great movement towards paperless, electronic information transfer for shipping. For example, the Information Systems Agreement (ISA) represents 50 percent of all global ocean transportation volume, over 400 container ships and barges, more than 1.4 million TEUs, and more than 300 major port destinations. ISA members are major ocean carriers, including American President Lines, Crowley American Transport, Hapag-Lloyd, "K" Line, Maersk, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Orient Overseas Container Line, P&O Nedlloyd Containers, Sea-Land Services, Inc. and Yang Ming. ISA members use a single communications standard for Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), as well as a single software product for freight booking, document exchange and shipment tracking information.19

Obviously, the technology and services are available and in use. The transition to paperless shipping, however, has been slowed by customary shipping practices and the lack of well-developed law for electronic commerce. With respect to the first factor, education of the shipping community is required to replace old shipping practices, like

I

I.-post-departure filing of the Shipper's Export Declaration (SED), with new ones. If, for example, the American shipping community can make the transition to a standard pre-departure filing of SEDs, the United States' Automated Export System (AES) allows for a single filing of export documentation, compared to the traditional multiple filings of the same information to various government agencies.20 This elimination of paper processing

inefficiencies will save billions of dollars for businesses and governments.21 The present

global cost is estimated at $400 billion each year, or about 7% of the value of world trade.22 Still, less than 1% of all exports make use of the AES. Only 36% of freight forwarders and 32% of other exporters even plan to use the AES. Twenty-five percent of freight forwarders and 22% of other exporters have never even heard of the AES.23

Education of the public is thus a key component for integrating the Internet with the non-electronic world.

The second impedance to the establishment of paperless shipping-the lack of well-developed law for electronic commerce-cannot be addressed by education alone. The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) drafted a Model Law on Electronic Commerce (MLEC) in 1996; however, the MLEC remains a very bare framework which outlines the development that needs to take place for a robust, functional electronic commerce law. As an example of the complications that the

electronic frontier poses for law, we consider one of the most detailed provisions of the MLEC, Article 15: Time and place of dispatch and receipt of data messages.24 Traditional

Anglo-American contract law has a 'deposited acceptance' rule. This so-called 'mailbox

19 Information Systems Agreement, Common Multi-Carrier Information Exchange, URL:

<http://www.isaweb.com/>.

20 Buxbaum, Peter A., "AES: Boon or boondoggle?," The Atlantic Journal of Transportation, Issue #101, December 8, 1997, p. 1, 12A.

2 1

Woods, Charles A., Sharon A. Mazur, AUTOMATED EXPORT SYSTEM, Reducing Respondent Burden Through The Electronic Integration of Business and Government Information Requirements, URL: <http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/aes/arc.html>.

22 Bolero, URL: <http://www.

ttclub.nsf/ByKey/JMUS-3TCLCH?OpenDocument>. 23 Buxbaum, supra note 20.

rule' states that an offer is effectively accepted once the acceptance is properly posted. Meanwhile, an offer is revoked, not when the revocation is posted, but when it is

received.25 For contract offers and acceptances made virtually, MLEC Article 15 suggests that the posting or dispatch of a data message occurs when the data message enters an information system outside the control of the message originator.26

Time of virtual receipt of a data message is more complicated. In the case where the message receiver designates an information system, receipt occurs at the time when the data message enters that designated information system. If the data message is sent to an information system owned by the message receiver but not the designated one, receipt occurs at the time when the data message is retrieved by the addressee. If the message receiver has not designated an information system, receipt occurs when the data message enters the message receiver's information system.27

As for location, a data message is deemed to be electronically dispatched/received at the place where the originator/addressee has its place of business; or, if there is more than one business site, at the place of business which has the closest relationship to the underlying data transaction; or, if there is no business underlying the data transaction, at the principal place of business; or, if there is no place of business, at the

originator/addressee's habitual residence.28

The above configuration is precisely complex in order to establish accountability in the virtual plane. Accountability is an essential concern of security issues in cyberspace, where the medium's power to almost instantly duplicate and disseminate information is the very source of the difficulty to discern or assign accountability there. When international seaborne traders faced the issue of accountability on the high seas, they devised a shipping

24

UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce (1996), URL:

<http://itl.irv.uit.no/trade_law/doc/UN.Electronic.Commerce.Model.Law. 1996.html>. 25

Knapp and Crystal, Problems in Contract Law, 3d Ed., Little, Brown, and Company, 1993, p. 51-68.

26

UNCITRAL supra note 24. 27 Id.

instrument called a bill of lading (BOL). A BOL is a receipt for cargo. A clean BOL is issued when cargo is received undamaged, complete, in good order. An on board BOL is signed by the master of a vessel, or his representative, certifying that the cargo has been placed aboard. On board BOLs are usually required for the shipper to obtain payment from a bank in letter of credit transactions. An inland BOL documents the transportation of cargo between the port and the point of origin or destination. It generally contains information such as marks, numbers, steamship line, and similar information to match with a dock receipt.29

A BOL is also a contract for transportation between a shipper and the ocean carrier. In fact, the BOL is the pivotal contract in the international transaction of cargo.30

Unlike SEDs and other 'pieces of paper' that change hands in the shipping process, BOLs do not just convey information; they also prove cargo ownership. As such, they, and not just the information they convey, have value in and of themselves. BOLs are negotiable; they can be bought, sold, or traded.31

With an average consignment value of $37,500, the value of a single bill of lading (BOL) can be as high as $60 million.32 Legally, bills of

lading are a potential source of massive fraud. This is compounded in the case of an electronic BOL (EBOL) that as yet cannot be supported by established law. For example, there are no complete rules, or cases to look to for guidance, to distinguish a legitimate or forged EBOL if cargo ownership is in dispute.

The technical problem is simple: verification of ownership of the EBOL. One solution prototype is called Bolero. Bolero uses EDIFACT standard data messages and a

28 Id.

29 Ocean Bill of Lading, URL:

<http://www.tradecompass.com/library/books/terms/OceanBillofLading.html>.

30 The Legal Implications of Electronic Commerce in International Trade : The Electronic 'Bill of Lading,' The Bolero Project, URL:

<http://www.boleroproject.com/bolero.nsf/022225602d9467428025648a0027ced9/3e2468262cd738a8802 566110051692f?OpenDocument>.

31 Ocean Bill of Lading supra note 29.

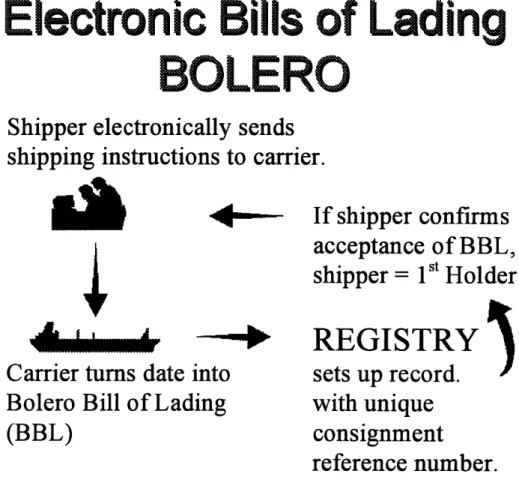

central registry records the Bolero Bill of Lading (BBL) holder at any given time. [see Figure 1.] To pass title, the BBL holder sends to the Registry a request to transfer the BBL title to a proposed new title holder. The Registry then passes this request to the proposed new title holder. If accepted, the Registry is notified and the Registry transfers title of the BBL to the new holder. Every message regarding the BBL is secured by a digital signature security system.33

The three main characteristics of digital signatures are integrity, authentication, and non-repudiation.34 Integrity ensures that data has been untouched since its signing. EBOLs demand data integrity to ensure that the content of the BOL is not altered.

Authentication provides proof of the data source, to verify the authenticity and identity of the BOL and its holder. Non-repudiation, in the context of Internet (or Intranet) security, is the ensuring that someone cannot deny involvement in an electronic transaction; for example, if someone were to send an electronic message stating acceptance of an EBOL title, the sender could not later deny that acceptance.

32

Nilson, Ake, "The paper bill of lading unravels with Bolero," URL: <http://www.ttclub.com/ttclub/bolero.html>.

33 Id.

34 Encryption and Digital Signatures, URL:

<http://www.frontiertech.com/Products/e-Lock/Document/elockoverview/4.HTM>.

Electronic Bills of Lading

BOLERO

Shipper electronically sends

shipping instructions to carrier.

Carrier turns date

Bolero Bill of Lad

(BBL)

If shipper confirms

acceptance of BBL,

shipper = 1st Holder

-

R REGISTRY

intn s.ts 1n rfeo.nrding

with unique

consignment

reference number.

Figure 1. THE BOLERO BILL OF LADING SYSTEM

While Bolero's communication and document management system would seem to have accomplished user accountability, the problem of accountability enforcement cannot be answered by technology alone. In the physical world, private international law, trade regulations and customary practices have provided the enforcement to realize this

accountability. To utilize Internet advantages for high seas trade, electronic Bolero BOLs have resorted to a required voluntarily assumption of binding legal responsibilities and obligations to compensate for the lack of established cyberspace law. Thus Bolero requires all users to agree to a legally binding regime established by a Bolero Rule Book.

The Rule Book sets out a multilateral contract that defines user roles and responsibilities to guarantee delivery, availability, and proper execution of users' particular instructions. The Rule Book also establishes a uniform liability policy to protect users' underlying business interests and promote user confidence in Bolero.35

Because accountability and its effective enforcement are fundamentally questions of security, it follows that security in general on the Internet may be accomplished in ways similar to that of electronic BOLs. This suggests that to address Internet security

concerns, we should consider a legally binding regime for cyberspace set out by a multilateral treaty, the goal of which is to establish legal accountability for cybernauts, including a consistent liability mechanism to address user concerns and promote user confidence. While the range of interests and concerns might discourage some from entertaining ideas for such development, we have already accomplished such a broadly issue-encompassing treaty for the seas.

35 "Completing the Puzzle," Introduction, The Bolero Service Business Requirements Specification, Version 1.0, 1997. URL:

<http://www.boleroproject.com/bolero.nsf/022225602d9467428025648a0027ced9/ed9lcf717f516f688025 6535004e00f8?OpenDocument>.

III. The Public International Law of the Sea

Public international laws involve international relations between independent countries, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOS). Because the Internet has developed as a frontier for independent, individual users, private

international laws may prove more germane for the development of Internet law than any public international law. This, however, does not diminish what the LOS may also

contribute. The LOS, after all, has immediate impact on individual users of the sea:36

fishermen, marine researchers, shippers, passengers, crew. In this Part, we examine the ways that international law has answered the legal challenges arising from security concerns on the high seas.

The first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was held in Geneva in 1958 and produced four conventions. The Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, the Convention on the High Seas, and the Convention on the Continental Shelf were largely based on customary law and, as such, drew wide support as generally accepted rules of law. The Convention on Fishing and Conservation of Living Resources was less popular because it went beyond customary practice.37 UNCLOS

failed to negotiate the breadth of the territorial sea, an issue which defeated an earlier 1930 conference to codify the international law of the sea, held by the League of Nations.38 In 1960, the second United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea

(UNCLOS II) also failed, by one vote, to answer the breadth of territorial sea question, as well as the related question of fishery limits.39 As formal statements embodying much

pre-existing customary law, the UNCLOS Conventions form the basic legal regime for the law of the seas. Formally, States party to those conventions are bound until they denounce them or until they become party to the LOS. At the same time, however, the UNLCOS 36 Churchill supra note 1 at 1-2.

3 7

Id. at 13. 38 Id. at 13-14. 39 Id. at 14.

Conventions' provisions are being replaced by LOS provisions as the LOS provisions pass into customary international law.

The third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) began in late 1973.40 The goal of UNCLOS III was to establish a "comprehensive regime

'dealing with all matters relating to the law of the sea, . . .bearing in mind that the

problems of ocean space are closely interrelated and need to be considered as a whole."'41 One hundred fifty States participated in the conference that became a political rather than a narrowly legal enterprise. Many interests were represented, most notably that of

developing States known as Group 77. Other interests included Western capitalist States, Eastern socialist States, land-locked and geographically disadvantaged States, archipelagic States, coastal and maritime States, and straits States. There were three committees. One was formed to work on a legal regime for the deep sea bed. Another addressed issues involving the territorial sea and contiguous zone, the continental shelf, the exclusive economic zone, the high seas, and fishing and conservation of living resources of the high

seas. The third committee handled preservation of the marine environment and scientific research. The resultant United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOS) of December 10, 1982 entered into force on November 16, 1994.42

Article 87 and 89 of the LOS codify the rule of customary law and a cornerstone of international law43: the high seas are open to all States and subject to no State's

sovereignty or jurisdiction. Freedom of the high seas includes freedom of navigation, freedom of overflight (by air), freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines, freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations as permitted by international law, 40

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. xxii.

41 Id. at xix.

42 Convention on the Law of the Sea, Oceans and the Law of the Sea, Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations. URL:

<http://www.un.org/Depts/los/losconvl.htm>. 43 Churchill supra note 1 at 165.

freedom of fishing, and freedom to conduct scientific research.44 Freedom on the high

seas is not perfect, however, as stronger States are often able to insist that their own preferences are honored by weaker States. For example, The United States and the United Kingdom carried out nuclear testing in the Pacific in the 1950s45 but such exercises

on the high seas, by, say, India or Pakistan, would likely not be tolerated by the international community today.

Public order is achieved on the high seas through accountability by nationality. In general, ships are granted nationality by a country whose flag the ship then flies. Each State sets its own requirements or conditions that a ship must meet to be granted nationality. While Article 91 of the LOS, as well as Article 5 of the High Seas

Convention, requires a "genuine link" to exist for a ship to fly the flag of a State, the legal requirement has had little effect in practice. Genuine link is difficult to establish where, for example, ships are owned by multinational companies. State adherence to this rule has been inconsistent. Countries that have complied, like Portugal, Norway, and France,

usually require some fixed proportion of the ship's owners and/or crew be nationals of the State for which a flag is sought.46 Countries that have not complied with the "genuine

link" requirement, like Liberia, Panama, Cyprus, and Singapore, are generally known as 'flag of convenience' or 'open registry' States. Flags of convenience may be attractive because they usually require lower fees, taxes, crew wage and manning levels, and sometimes even lower required compliance with international safety standards. Flags of convenience are also known to be unreliable in matters concerning pollution control and shipping safety, including crew qualification standards.47

44Article 87, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 31.

45 Churchill supra note 1 at 167. 46 Id. at 206.

47 Id.

_ ____

A ship is allowed to fly only one country's flag.4 8 If a ship holds more than one

State's flag, it will be considered a ship without a flag or nationality in any international dispute or conflict that may arise.49 This is significant because a ship enjoys the diplomatic protection of the country whose flag the ship flies. In fact, in general, a ship on the high

seas is under the exclusive legislative and enforcement jurisdiction of its flag State. A State becomes responsible for the ships that fly its flag. Under the LOS, Article 94, States have duties to keep a record of all ships that fly its flag, to effectively control their conduct on the high seas including their rendering of assistance to ships in distress, and to ensure their seaworthiness and safe operating conditions and practices in accordance with generally accepted international standards. Some duties of a flag State are quite specific. Article 113 and 114 of the LOS require a State to ensure compensation for submarine cables and pipelines that are damaged by ships or persons, respectively, under the State's jurisdiction; correspondingly, by Article 115 of the LOS, a State must also ensure that

ships are compensated if they must sacrifice an anchor or fishing gear in order not to damage a cable or pipeline

In the event of a collision or any navigation incident on the high seas, in general only the flag State may arrest or detain one of its own ships. Likewise, any penal or disciplinary proceedings against a crew member of a ship may be instituted only by authorities of the flag State, or the State of which the crew member is a national, though flag state jurisdiction is considered as primary in cases of concurrent jurisdictions.

Similarly, in matters concerning a master's certificate or license, only the issuing State may revoke or withdraw such certificates, after due legal process, regardless of the nationality of the certificate holder.

48 Article 92(1), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations,

New York, 1983, p. 31.

49 Article 92(2), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 31.

Unfettered freedom on the high seas and exclusive flag State jurisdiction over ships on the high seas are subject to a few restrictive rules. Slave trading and illicit traffic in narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances are prohibited on the high seas. Unauthorized television and radio broadcasting intended to be received by the general public, is also prohibited on the high seas, except for distress calls. By customary law since the era when European powers sought to protect their shipping links to their colonies, every State also

has a duty to act to suppress piracy.5 0 The LOS defines piracy as any illegal act of violence, detention, or depredation on the high seas, or outside any State's jurisdiction,

committed for private ends by the crew or passengers of a private ship or aircraft, against another ship or aircraft or its persons or property on board; piracy includes any intentional participation or facilitation of such acts.51 Any act of violence, detention, or depredation by a State vessel is, by definition, governmental action and not an act of piracy unless it is perpetrated by a crew that has mutinied and taken over the State ship. Piracy also requires that at least two ships-a pirate ship and a victim ship-be involved. Acts of violence, detention, or depredation involving a single ship are distinguished from piracy as hijacking. Thus a mutinying crew hijacks its own ship but only commits piracy when they attack another ship.

A State warship may board a foreign ship if the warship has reasonable ground to suspect that the foreign ship on the high seas is engaged in piracy or unauthorized, "pirate" broadcasting. If the suspicion proves true, in these two cases, the LOS grants

States both legislative and enforcement jurisdiction over the ship and those on board, in concurrence with flag State jurisdiction.52 Warships may also board a foreign ship suspected of slave trading but only a slave trading ship's flag State may arrest the slave

50 Churchill supra note 1 at 169. Article 100, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 33.

51 Article 101, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 34.

52 Article 105, 109, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 34, 35.

trading ship or those on board.53 If a slave escapes and takes refuge on board a ship, the slave becomes ipsofacto free. For a ship suspected of illicit drug traffic, only its flag State has jurisdiction, unless the flag State requests other States for aid.54 A warship may also

board a ship on the high seas if the warship reasonably suspects that the ship to be boarded is of its same nationality; the warship may board such a ship to verify its nationality.55 As in any case of a warship boarding based on suspicion, if the suspicions are without

reasonable grounds, the detained ship has the right to compensation for any resultant loss or damage sustained. A ship without nationality is not automatically subject to any State's jurisdiction but if a State does attempt to exercise jurisdiction over a ship without

nationality, by definition no other State has a right to object to such an exercise. At the same time, States of course would retain jurisdiction over any of their nationals on board.

53 Article 99, 110(l)(b), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 33, 35.

54 Article 108, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations,

New York, 1983, p. 35.

55 Article 110(1)(e), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, The Law of the Sea, United Nations, New York, 1983, p. 35.

IV. Reconfiguring the Law of the Sea for Cyberspace

In this Part, we draw upon the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

(LOS) to develop a legal regime for cyberspace that will better promote security in virtual

information transactions. From Part II, we settle on accountability and enforcement as the intermediary goals for reconfiguring the LOS for a cyberspace regime. We then devise virtual analogues for marine aspects of the LOS. For reference purposes, we retain the article numbers of the LOS from which we derived these proposed Internet provisions. Article numbers that begin with "A" were derived from The Agreement Relating to the

Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, that entered into force on July 28, 1996.56 Also note that for the

purposes of this construction, the term "virtual site" is meant to include any virtual interactive site including web pages or sites, multiple user dungeons, chat rooms, etc. "State Parties" means States which have consented to be bound by this regime and for which this regime is in force.

The first articles set out general principles of freedom and peaceful conduct for cyberspace, as well as the recognition of cyberspace as an environment outside the sovereignty of any State.

GENERAL PROVISIONS

Article 87. Freedom of the Internet

1. The Internet is open to all States. Freedom of the Internet is exercised under conditions laid down by this Convention and by other rules of international law. It comprises, inter alia:

a) freedom of navigation in cyberspace;

b) freedom to construct virtual sites.

56Oceans and the Law of the Sea, URL:

<http://www.un.org/Depts/los/losconvl.htm>.

2. These freedoms shall be exercised by all States with due regard for the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the Internet, and also due regard for the rights under this Convention with respect to activities in the Area.

Article 88. Reservation of the Internet for Peaceful Purposes The Internet shall be reserved for peaceful purposes.

Article 89. Invalidity of Sovereignty over the Internet

No State may validly purport to subject any part of the Internet to its sovereignty.

Articles 91 and 92 then establish a means of virtual accountability by establishing a nationality status to tag users of the Internet and the virtual sites constructed there. While this may seem repugnant to laissez-faire cyberspace purists, we do not require

conscription to this regime. By allowing the option to exist and act in cyberspace without nationality, these articles do not necessarily reduce the present degree of anonymity

available in cyberspace. At the same time, by the proposed regime, any unregistered use is without protection of a national State if a virtual incident should arise. The idea is to give

cybernauts and owners/operators of virtual sites the option for greater accountability and protection. Such concerns seem most relevant to electronic commerce, as described in the maritime context by the Bolero discussion. By the proposed regime, cybernauts could limit their use of the Internet as registered virtual nationals to electronic commercial transactions and other uses that affect or require security, remaining anonymous

otherwise. It is hoped that cyberspace activity can be configured in such a way to allow this kind of selective use.

_ __ L

Article 91A. Nationality of Cybernauts

1. Every State shall fix the conditions for the grant of its virtual nationality to

cybernauts, for the registration of cybernauts, and for the right to use the Internet as its virtual national. There must exist a genuine link between the cybernaut and the State.

2. Every State shall issue to cybernauts to which it has granted virtual nationality documentation to that effect.

Article 91B. Nationality of Virtual Sites

1. Every State shall fix the conditions for registration of virtual sites, and for the right of virtual sites to 'fly' its flag. There must exist a genuine link between the virtual site and the State.

2. Every State shall issue to virtual sites to which it has granted the right to fly its flag documents to that effect.

Article 92A. Status of Cybernauts

1. Cybernauts shall operate under the virtual nationality of one State only and, save in exceptional cases expressly provided for in international treaties or in this

Convention, shall be subject to its exclusive jurisdiction in cyberspace. A cybernaut may not change his/her virtual nationality, save in the case of a real change of registry.

2. A cybernaut which uses the Internet under the virtual nationality of two or more States, using them according to convenience, may not claim any of the virtual nationalities in question with respect to any other State, and may be assimilated to a cybernaut without virtual nationality.

Article 92B. Status of Virtual Sites

1. Virtual sites shall operate under the flag of one State only and, save in exceptional cases expressly provided for in international treaties or in this Convention, shall be subject to its exclusive jurisdiction in cyberspace. A virtual site may not change its flag, save in the case of a real transfer of ownership or change of registry.

2. A virtual site which operates under the flag of two or more States, using them according to convenience, may not claim any of the nationalities in question with respect to any other State, and may be assimilated to a virtual site without virtual nationality.

The duties of virtual nationality States as given in article 94 suggest that the most convenient "genuine link" between a cybernaut and a virtual nationality State is the cybernaut's physical nationality State. Still some cybernauts may prefer another State for its protective strength in international relations, or, as with maritime flags of convenience, for its lack of strict restrictions.

Article 94. Duties of the Virtual Nationality State

1. Every State shall effectively exercise its jurisdiction and control in administrative,

technical, and social matters over cybernauts using the Internet under its virtual nationality and over virtual sites flying its flag.

2. In particular every State shall:

a) maintain a register of its cybernaut nationals containing the names and particulars of cybernauts using the Internet under its virtual nationality, except those which may be excluded from generally accepted international regulations; and

b) assume jurisdiction under its internal law over each of its cybernauts in respect of administrative, technical and social matters concerning Internet use;

c) maintain a register of virtual sites containing the names and particulars of virtual sites flying its flag, except those which may be excluded from generally accepted international regulations; and

d) assume jurisdiction under its internal law over each virtual site flying its flag and over the network system operators and personnel in respect of administrative, technical and social matters concerning virtual sites.

3. Every State shall take such measures for its cybernaut nationals and for its virtual sites as are necessary to ensure security in cyberspace with regard, inter alia, to:

a) the construction, equipment, and technical integrity of cybernaut interfaces and virtual sites;

b) the manning of virtual sites, operating conditions, and the training of personnel,

taking into account applicable international standards and protocols; c) the use of information, the adherence to information integrity and security

measures, the maintenance of communication lines and connections, and the prevention of information corruption.

4. Such measures shall include those necessary to ensure that each cybernaut is fully conversant with and required to observe the applicable international regulations concerning information integrity and security and the prevention of information corruption.

5. Such measures shall include those necessary to ensure:

a) that each virtual site, before registration and thereafter at appropriate intervals, is surveyed by a qualified surveyor of virtual sites, and has available such

documentation as are appropriate for the safe navigation of the virtual site;

b) that each virtual site is under the charge of a network system operator and

personnel who possess appropriate qualifications;

c) that the network system operator and, to the extent appropriate, the personnel are fully conversant with and required to observe the applicable international

regulations concerning information integrity and security, the prevention of information corruption, and the management of communications and connections.

6. In taking the measures called for in paragraphs 3, 4, and 5 each State is required to

conform to generally accepted international regulations, procedures and practices and to take any steps which may be necessary to secure their observance.

7. A State which has clear grounds to believe that proper jurisdiction and control

with respect to a cybernaut or virtual site have not been exercised may report the facts to the cybernaut's or virtual site's virtual nationality State. Upon receiving such a report, the virtual nationality State shall investigate the matter and, if appropriate, take any action necessary to remedy the situation.

8. Each State shall cause an inquiry to be held by or before a suitably qualified person

or persons into every incident of Internet use involving its cybernaut nationals or involving a virtual site flying its flag, and causing serious injury to nationals of another State or serious damage to information originating from another State.

The national State and the other State shall cooperate in the conduct of any inquiry held by that other State into any such Internet incident.

Registration or licensing fees may ameliorate the burdens of registry for the State. Such fees, however, should not be great enough to deter registration. This concern then would join other access issues that already exist, as politicians espouse the vision of universal Internet access with little details for realizing such access for every man, woman, and child. In other words, virtual nationality should not be dismissed simply because of the infrastructure burdens that it would entail. Such burdens already exist and it seems unlikely that registry as an additional information service could not be likewise

accommodated by a given infrastructure/access solution.

To enforce accountability, jurisdiction is accomplished by Articles 97 and 27, modeled after customary law long-followed on the high seas. The proposed provisions grant jurisdiction to a State when information exchange in cyberspace directly results in physical consequences within territory that is under that State's sovereignty.

Article 97. Penal Jurisdiction in Matters of Internet Incidents 1. Cybernauts

a) In the event of an incident of navigation concerning a cybernaut on the Internet, involving the penal or disciplinary responsibility of the cybernaut, no penal or disciplinary proceedings may be instituted against such person except before the judicial or administrative authorities either of the virtual national State or of the

State of which such person is physically a national.

b) In disciplinary matters, the State that has registered the cybernaut shall alone be competent, after due legal process, to pronounce the withdrawal of such

registration, even if the holder is not a national of the State which issued the cyberspace registration.

c) No virtual arrest of a registered cybernaut, even as a measure of investigation, shall be ordered by any authorities other than those of the cybernaut's virtual nationality

State. (Physical arrest would necessarily involve the appropriate authorities of the physical location of the cybernaut.)

2. Virtual Sites

a) In the event of an incident of navigation concerning a virtual site on the Internet, involving the penal or disciplinary responsibility of the network system operator or of any other person in the service of the virtual site, no penal or disciplinary

proceedings may be instituted against such person except before the judicial or administrative authorities of the virtual site's flag State, or of the State of which such person is a virtual national, or of the State of which such person is a physical national.

b) In disciplinary matters, the State that has registered the virtual site shall alone be competent, after due legal process, to pronounce the withdrawal of such

registration. The State that has issued any network system operator's certificate of competence or license shall alone be competent, after due legal process, to

pronounce the withdrawal of such certificates, even if the holder is not a national, physical or virtual, of the issuing State.

c) No seizure of a registered virtual site, even as a measure of investigation, shall be ordered by any authorities other than those of the virtual site's flag State.

Article 27. Criminal Jurisdiction over Foreign Virtual Sites

1. The criminal jurisdiction of a State does not extend to a foreign virtual site to arrest any person or to conduct any investigation in connection with any crime committed in cyberspace, save only in the following cases:

a) if the consequences of the crime physically extend to the State;

b) if the crime is of a kind to physically disturb the peace of the country of the State; c) if the assistance of the local authorities has been requested by the network system

operator of a virtual site or by a diplomatic agent or consular officer of a virtual site's flag State; or

d) if such measures are necessary for the suppression of illicit traffic in narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances.

2. In the cases provided for in paragraph 1, the State shall, if the network system operator so requests, notify a diplomatic or consular officer of the virtual site's