Photography as a Mirror in Alison

Bechdel’s Graphic Memoir Are You My

Mother?: A Comic Drama

Małgorzata Olsza

Abstract

In her 2006 graphic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, Alison Bechdel employs numerous family photographs to authenticate and comment on her complicated family history. Drawing on the use of photography in Fun Home, I examine the manner in which photography functions in Bechdel’s other graphic memoir, Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama (2012). The photographs of Alison and her mother that are carefully selected and incorporated into the structure of Are You My Mother? do not only function as documents. In fact, as I shall argue, they can be regarded as mirrors, or critical reflections on the role and presentation of the self in graphic memoir. In Are You My Mother?, photography often has an interrogative (and not simply referential or authenticating) function. Not so much caught up with discovering the truth about a particular family history, photography is used to expose the complexity of the narrative of the self.

Résumé

Dans son autobiographie graphique Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006), Alison Bechdel emploie de nombreuses photos de famille pour authentifier et livrer un commentaire sur son histoire de famille compliquée. Faisant appel à l’utilisation de la photographie dans Fun Home, j’examine la manière dont la photographie fonctionne dans l’autre autobiographie graphique de Bechdel, Are You My Mother?: A Comic

Drama (2012). Les photographies d’Alison et de sa mère qui ont été soigneusement sélectionnées et

incorporées dans la structure de Are You My Mother? ne revêtent pas uniquement une fonction documentaire. J’argumenterai qu’elles peuvent être perçues comme des miroirs, ou des réflexions critiques sur le rôle et la présentation de soi dans l’autobiographie graphique. Dans Are You My Mother?, la photographie remplit souvent une fonction interrogative (et non, simplement, une fonction référentielle ou d’authentification). Davantage que pour découvrir la vérité vis-à-vis d’une histoire familiale particulière, la photographie est utilisée pour mettre au goût du jour la complexité de la mise en récit de soi.

Keywords

Published in 2012, Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama tells the story of the author’s complex relationship with her mother. Like Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006), Bechdel’s tale of her personal and artistic growth and her relationship with her father, Are You My Mother? is a graphic memoir or, to use Gillian Whitlock’s term, an “autographics” (966). As Whitlock observes, “autographics” is a visual form of autobiography that, most importantly, points to “the subject positions that narrators negotiate in and through comics” (966). Autographics thus engages with shifting concepts and configurations of the self. Though their subject matter and main focus differ, Bechdel uses drawn photographs in both memoirs to problematize the narrativization of self, demonstrating that the truth of one’s life is constantly renegotiated. In them, photographs do not simply validate the telling, but rather help the protagonist-narrator Alison to reexamine her family history and her position within it.

In what follows, I examine the use of drawn photographs in Are You My Mother?, arguing that they function as mirrors that allow Alison to reflect (pun intended) on the narration and construction of self. Michael A. Chaney argues that in this life-writing genre, mirrors “prod us to wonder about matters of illustration and fidelity” (10) and invoke “ghostly structures of meaning lying beneath the visible surface, which in turn solicits a psychoanalytic approach to comics texts” (23-24). As “mirror[s] with a memory” (Holmes), photographs provide the means for Alison to examine herself diachronically, at different ages, and arrive at an understanding of herself as influenced by a complex relation with her mother. I begin by discussing the interactions between photography and graphic memoir, commenting on the use of drawn photographs in Fun

Home. These observations pave the way for a discussion of photography in Are You My Mother? in the

context outlined above.

Photography and the Graphic Memoir

A main question presents itself when considering the role of photography in memoirs and other forms of life writing: the possible authentication with which a photograph endows a nonfictional text, or its potential failure to do so. The question of authentication in photography, both as a medium and a visual product of that medium, however, is a complex one, especially when we pose it in the context of graphic memoir, in which drawing functions alongside or sometimes even in lieu of photographic images to narrate a particular story. When photographs are actually reproduced in graphic memoir (as is the case with, for example, Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1986, 1991) or David Small’s Stitches (2009)), the power of the real implied by the medium of photography affects the reader/viewer (Hirsch 30). As Susan Sontag observes, “[p]hotographs furnish evidence. … The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture” (175). While photographs may be deceitful insofar as they pose as transparent representations of the real, they nevertheless enjoy a documentary or authenticating status; readers readily approach them as having a supposedly unmediated relation to the real. As Roland Barthes puts it, “from the phenomenological viewpoint, in the Photograph, the power of authentication exceeds the power of representation” (89). Indeed, the photograph appears to explore and avow the documentary and the real, acting as an authentication authority (Roth 87).

This reading of photography, which focuses on the power of the medium and the referential aspect of the represented, downplays the mediating qualities of photography. However, when photographs are both reproduced and drawn in a graphic memoir, their status changes, since the “evidentiary truth of seeing” (Cvetkovich 114) implied by the real photograph is confronted with other visual and verbal representations of the same truth (as exemplified by, among others, the second volume of Maus (1991) or Lynda Barry’s

One! Hundred! Demons! (2002)). For example, Hirsch emphasizes that the juxtaposition of the photographed

and the drawn image exposes “the levels of mediation that underlie all visual representational forms” (25). While Hirsch makes it clear that mediation is an inherent aspect of creating images of all types, she also points out that this aspect becomes more transparent when a drawing is made to narrate alongside a photograph.

Because drawing in general implies artifice, when photographs are reproduced solely in the form of a drawing (as in both of Bechdel’s graphic memoirs), they tend to be read as “fictional,” and can thus serve to question the status of the graphic memoir as truthful (Pedri, “Graphic Memoir” 129). As Nina Ernst observes, “[t]he incorporation of photographs into the drawn cartoon universe assimilates the documentary with the aesthetic,” the real with “the distance created by drawn panels” (74). While the two media may function together to impart truth, there nevertheless remains a “distance” between the photographed and the drawn image; the latter is usually seen as belonging to a “secondary order of reality.” Drawn photographs endow graphic memoir with an additional narrative and structural dimension: they point to the tensions between “the documentary” and “the aesthetic,” which graphic memoir may help negotiate.

Indeed, in refuting the implications of its inherent fictionality, comics may also be studied in terms of visual evidence. In her discussion of documentary and nonfiction comics by Art Spiegelman, Joe Sacco, and Keiji Nakazawa, Hillary Chute argues that while drawing may appear to be at odds with the category of nonfiction, “in its succession of replete frames, comics calls attention to itself, specifically, as evidence. Comics makes a reader access the unfolding of evidence in the movement of its basic grammar, by aggregating and accumulating frames of information” (Disaster Drawn 2). The discussion of how real, real and drawn, and drawn photographs function in graphic memoir demonstrates that while photography fluctuates between its status as “evidence” and as a “product of mediation,” it should not be discussed in terms of rigid divisions between “authentication” and “aesthetic” because the graphic memoir by its nature is devoted to “the changing discourses of truth and identity” (Whitlock 966). Thus, it is more productive to focus on the unique forms of visualization and narrativization that graphic memoir offers, regardless of whether it incorporates real photographs, drawn photographs, or a combination of the two.

In Fun Home, photographs are drawn in a manner that suggests they were reproduced directly from a family album: some photographs are rendered with photographic corners, while others are drawn as if Alison were holding them in her hand. In both cases, however, they act as “the visual and emotional kernel out of which the story emerges” (Cvetkovich 115). Indeed, photographs in Fun Home may be read primarily as points of contact and points of transgression, as moments of identification and moments of difference that bring together and at the same time distance Alison from her father, Bruce. For example, when Alison examines the drawn photograph of her father and the one of herself, she states that the two are similar in relation to setting, lighting, and facial expressions. “It’s about as close as a translation can get,” Alison observes (120). When she looks at the photographs, she feels at once connected to and different from her father. This is particularly evident when Alison discovers the famous photograph of Roy (100-101), Alison’s childhood babysitter and family friend, and, as Alison comes to realize after discovering the photograph, Bruce’s secret lover. The photograph prompts a re-investigation of the Bechdels’ family history in a manner that is both evincible and personal. It offers “Alison occasions for introspection, as she rereads her past to discover untold family stories” (Watson 37-38), granting her the possibility to engage with her father’s double life, and to reflect on the nature of her complex relationship with him and the family trauma connected with his death and closeted life.

photographs she is able to consider the interplay between “the known and the unknown” (Sedgwick 3) that surrounds Bruce’s life as a closeted homosexual. She thus bends photography in order to elicit from it something more than the documentary. In this sense, photography does much more than simply provide visual evidence for what is being narrated. Drawn photographs in Fun Home serve as moments of reflection on the nature of the past (Chute, Graphic Women 200), revealing untruths or half-truths that overshadow Alison’s family life.

Bechdel also bends photographs in an explicitly formal manner, carefully drawing the photographs instead of inserting actual reproductions into the hand-drawn comics universe. Consequently, she defies the time distance between the events seen in the photographs and the moment in which they are re-contextualized in the memoir. In Fun Home, photographs are presented “as if lifted from the past into the present” (Saltzman 85). This is particularly evident when Alison is depicted holding a drawn photograph in her hand (100-101, 102, 120). In these instances, the past of the photographed moment combines with the present moment of (re)examination.

Indeed, the discussions of photographs in graphic memoir should not be limited to the binary opposition of truth/lie, because both autobiographies and photographs are “artificial representations of lives” (Dow Adams 5). Authentication is rarely the main concern of the graphic memoirist. Hence, the question of photographic authentication or lack thereof in an autobiographical text should give way to a study of “the deeper layer of complexity in the act of self-representation” (Haverty Rugg 2). In what follows, I propose to conceive the photograph in Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? as a mirror, an image that does not capture or document reality, but also reflects it back and distorts it in the process. In its role as mirror, the photograph thus functions to question the past in order to “open up new and troubled spaces of representation” (Whitlock 976).

The “Family Album” in Disarray: Creating a Photography-Based Narrative in Are

You My Mother?

Are You My Mother? was construed through an arduous process of reworking and restructuring. Commenting

on the difficulties associated with creating her second graphic memoir, Bechdel observes that, in a sense, she reworked and revised Fun Home’s aesthetics in order to “write about the problem of the self in relationship with the other” (“Public” 203). For example, intertextual references to modernist texts introduced in Fun

Home give way to reflections about the familial self as inspired by Donald Winnicott’s psychoanalytic theory.

Bechdel repeats after Winnicott that, “the father can be murdered, but the mother must be dismantled,” pointing to the fact that “out of necessity [Are You My Mother?] is more complicated” (Interview). The same holds true for the use of photography. The function of photography in Are You My Mother? expands upon the models adopted in Fun Home. Playing an equally critical role, photography comments on the self and the way in which it is caught up in the “tricky reversed narration” (Bechdel, Fun Home 232) of the past and the present.

As in Fun Home, the photographs in Are You My Mother? are drawn; however, at first sight, they do not feature as prominently in the latter’s story. For example, there are no header photographs at the beginning of each chapter as is the case in Fun Home; instead, visualizations of Alison’s dreams open each section of Are

You My Mother?. Likewise, fewer photographs are included in the chapters themselves and those that are

included are mostly of Alison and her mother, Helen, at different stages of their lives. In Are You My Mother?, the photographs in the family album – that “locus of trauma and conflict and a site of love, affection, personal storytelling, and production of subjectivity” (Sandbye) – are disorganized and, as Alison observes at one

point, “scattered about in different albums and boxes” (Are You 31). Alison, at once narrator and protagonist, is tasked with organizing the album. And, through the process of planning, arranging, and drawing a photography-based narrative, she reexamines herself and, by extension, her relationship with her mother (Bechdel repeats after Winnicott that the mother-child relationship greatly determines how we “relate to the outside world” (Are You 22)). As in Fun Home, Are You My Mother? presents Alison untangling while also adding to her family’s narrative, trying to simultaneously discover its hidden meanings and locate herself in a family history in which her life intertwines with that of her mother.

Respectively, if the “family archive” is the site in which subjectivity is produced (Sandbye), Bechdel (re)examines her family history through family photographs so to better understand herself. Photographs, as mirrors, reflect Alison’s story back to her (both as an independent entity and as a subject entangled in the family’s complex relationships). By doing so, photographs provide Alison with “an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal” (Sontag 177), which prompts her to examine her self-in-the-making. In Are You My

Mother?, the referential aspect of photography becomes self-referential in the double sense of the word: it

focuses on itself and calls attention to its artificial status.

Photography functions as a mirror from the very first chapter of Are You My Mother? in which Alison admits to herself that she “just need[s] to tell a story,” even though “it’s hard to figure out what the story is” (28). She recognizes that she has to look at herself in the type of a double perspective provided by a mirror, as both the subject and the object of the story/gaze, balancing between the two perspectives of autobiography. After talking to her mother Helen on the phone, Alison turns her attention to a photograph of her mother and herself as a baby. She confesses that she has “always been fascinated with the photo” (31) and only recently has come to realize that this particular image is a part of a larger whole. This discovery prompts her to engage with the photograph, creating (and, in the process, reflecting on) the story of the self.

With the turn of the page, the reader is presented with a two-page spread depicting a close-up of Alison’s drawing board with photographs and drawing utensils laying around in disarray (32-33) (fig. 1). The narrative framework provided in the captions confirms this initial impression of disorganization. Alison points out that while she had no way of knowing what the actual sequence of photographic shots looked like, she has “arranged them according to [her] own narrative” (32), adding that in her story “the rapport between mom and [herself] builds until [she] shriek[s] with joy” (33). In this sequence, Alison both tells a story, imposing her reading on the photographs, and openly acknowledges that it is but one of many possible stories. Acknowledging that a photograph can carry multiple meanings, Alison corroborates the theory that drawn photographs tend to be interpreted in a narrative context (Pedri, “Cartooning” 265). They are not referential or objective in the sense of the Barthesian “that-has-been” and “there-[it]-is” (113); instead, they function as more nuanced narrative elements. Photographs, Bechdel implies in Are You My Mother?, do not authenticate or confirm one’s knowledge of the self, but rather trigger narrative possibilities, propelling the process of self-(re)presentation.

Figure 1. Alison’s drawing board with the photographs and drawing utensils from: Bechdel, Alison. Are You My Mother?, 2012, p. 32-33.

ARE YOU MY MOTHER? by Alison Bechdel. Copyright © 2012 by Alison Bechdel. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt reserves all rights not specifically extended herein.

A closer look at the representation of the drawing board confirms such a stance. The act of creating an original and personal narrative out of the disorganized and forgotten images is accompanied by a metavisual commentary in the form of drawing utensils. The role and importance of a personal and, to a large degree, unverifiable narrative is both emphasized (the drawing tools and the drawing board are markers of creativity and subjective vision) and challenged (insofar as the same elements are signs of artificiality). In a telling arrangement, neither the photographs nor the drawing utensils dominate the page layout; they exist together on equal footing in a shared artistic space. The act of arranging the photographs can also be read as the act of organizing comics panels on the page “in the sequential continuum” (Groensteen, System 26). Alison, who is both a memoirist and artist, creates her narrative of self in response to the family photographs she reads, positioning it between truthfulness (what is really documented in the photographs) and critical self-reexamination (how she interprets the relation between herself and her mother from the perspective of an adult, an artist, and a psychoanalytic patient). She questions “the mythical status of photography as a particularly authentic medium” (El Refaie 138) and demonstrates that her narrative will be suspended between the real and the constructed, inasmuch as life is “all in the constructing, in the text, or the text making” (Bruner 27). Readers come to understand that the continuum she proposes may or may not be truthful. Indeed, the photographs should be read primarily in terms of creating a narrative of the self as Alison struggles to “physically remember the strewn pieces of her family drama” (Camden 99) and impose an order on them. Fluctuation between creativity and artifice also characterizes a second way of using photographs in Are You

photograph for each panel, with Bechdel posing as the character she wishes to draw. Such a practice, adopted also in the making of Fun Home, allows Bechdel to “create a relational space between her past selves and her present selves by using her own body to perform scenes from her autobiographical memory” (Rüggemeier 260). Here, too, memory joins performance to emphasize the tension between the real and the constructed, and ultimately expose the relational nature of the self. Consequently, similarly to Fun Home, this procedure introduces “the potential for slipping into ‘all the poses’ in acts of autographical identification” (Watson 38) that destabilize the very notion of autobiography. In this sense, Bechdel uses photography in a somewhat subversive manner; through it, she questions and expands her autobiographical self, performing the characters of others.

While she employed the same technique in Fun Home, the artist shows it explicitly only in Are You My

Mother?. Following a large panel depicting Alison experiencing an emotional breakdown after a phone call

with her mother (Are You 229), an older Alison is shown recreating the scene in front of a camera (Are You 233). The act of turning the camera lens on oneself is equivalent to directing the gaze on the self in the mirror, an act that relates to questions of focalization (Mikkonen 76). Alison evidently needs the outside frame of the photograph-as-mirror to zoom in on herself and her life story. Such a frame provides her with a clear focus, but it also grants her an equally needed distance, as Alison is able to look at herself simultaneously from within, as the subject, and from without, posing as the object. She subsequently ponders the possibility for “two separate beings to be identical – to be one…” (Are You 35). While she refers primarily to the relation between the child and the mother, she also reflects on the complex bond between the two selves and the perspectives they provide.

Different as they may be, both uses of photography in Are You My Mother? point to a reflective view of photographs as mirrors. Through photography, the self is simultaneously framed (there is a clear focus on the self, or selves) and questioned (as Alison performs different characters in her photographic stagings). Moreover, by arranging her photographic material (i.e. ordering it in accordance with her vision), Alison subtly demonstrates that her narrative, like other autobiographical narratives, “is not fixed but an evolving content in an intricate process of self-discovery and self-creation” (Eakin 3).

The Self in the Photographic Mirror

The concepts of mirror and mirroring, as formulated by Jacques Lacan and Donald Winnicott respectively, further inform Are You My Mother?. For one, in a chapter entitled “Mirror,” Bechdel refers to mirrors and mirroring to examine herself as caught up in “the contradictory dynamics” (Bauer 274) with her mother. Alison quotes Winnicott: “in individual emotional development the precursor of the mirror is the mother’s face” (213). The mother-as-a-mirror plays a crucial role in the formation of the child’s “coherent and authentic” (232) self because, as Alison repeats after Winnicott, “[w]hen I look I am seen, so I exist” (233). She then contrasts such a positive and self-empowering vision of the mirror with a more nuanced understanding of the mirror and its relation to the self as developed by Lacan. She contemplates the French psychoanalyst: “The ‘I’ is not nearly so solid, nor so easily apprehended, he implies. … The reflection in the mirror is you … but not exactly. … In this moment you identify with your image, your double, an unattainable ideal” (231-232). The mirror is conceptualized in a twofold manner. On the one hand, it helps one develop and strengthen their true self and, on the other hand, it provides an unrealizable, yet desired image of a coherent individual. In keeping with this paradoxical duality, Bechdel uses photographs as reflections that both challenge and consolidate the self.

The mirror/photography as challenging the self is first introduced when the “original mirror,” the mother, tells young Alison that she looks “pale” and “peaked,” and the girl starts to secretly use rouge (214). Faced with an unfavorable reflection of herself, young Alison wishes to somehow correct it. In a telling manner, instead of explicitly drawing the eight-year-old Alison with rosy cheeks, Bechdel reproduces in drawing a photograph of herself as a child. It is held by young Alison (only the hands are visible) who is correcting it with a red crayon so that it better reflects her mother’s ideal. Having failed to obtain reassurance, young Alison realizes that her true self is disappointing and, subsequently feels the need to conceal or enhance the defective self both in real life and in the existing images of herself.

At the same time, because of the perspective from which the reader looks at the photograph (one hand is holding the crayon and the other is holding the image), this scene may also be interpreted as a moment in which the artist in Alison “bends” reality to her vision, reflecting on the creation of the self-in-the-making. The act of retouching the photograph is the act of creating a narrative (Chaney refers to such self-referential practices in autobiographical comics as mise en abyme (23)) and, as such, it alludes to the two-page spread that gave rise to the entire memoir (32-33) (fig. 1). In both cases, Bechdel uses photographs as references to the real world, on which she later builds “narrative of the self” (Eakin 6). Through this practice, Alison comments on the photographic paradox, namely the fact that photographs combine a “built-in feeling of accuracy” with a “tendency to misrepresent,” which is viewed more “in terms of truth versus lie rather than fact versus fiction” (Dow Adams 3). The photograph is often assessed in terms of a black-or-white approach to reality, or in terms of binary oppositions (real/unreal, truth/lie, accurate/inaccurate), while, as Alison demonstrates, it should be seen as both fact and fiction. In the retouched photograph, Alison is both her real (factual) self and her idealized (fictional or “retouched”) self: the two visions of the self coexist in a single image. Bechdel repeats after Virginia Woolf, “let the biographer print … the known facts without comment; then let him write the life as fiction” (28). Photography sheds light on this life-writing duality. For one, her drawn photographs, “doubly descriptible” at their core, may be simultaneously read on the level of the represented (as fact) and on the level of the personal trace of the drawn (as fact as fiction) (Groensteen, System 125). They engage both evidence and mediation. Moreover, rather than depicting a photograph on its own, in two cases (32-33, 214), Bechdel combines the photograph with drawing utensils, thus pointing to the veracious and performative nature of her narrative of self.

A photograph depicting Alison at the age of twenty-four further questions and exposes the self as self in-the-making (226). Having just finished her karate training and wearing her Gi, she stands relaxed and half-self-conscious in front of the camera. In the accompanying caption, Alison observes, “in Donna’s [the photographer’s] mirror I am slack, lost, and oddly pretty” (226). The word “oddly” strongly suggests that she is able to recognize her own beauty in a mirror held by someone else. In a bittersweet admonition, however, Alison also points out that “[t]he photo is black and white, but my skin is tinted with retouching ink. My cheeks are pink like in my hand-colored school photos” (226). The marker of the original shame of the imperfect self, the rouge she applied to correct and “bend” her image, is present even in this older, and presumably more coherent, reflection. Alison admits that instead of coming to terms with how she looks and how she is seen by others (not only by her mother, but also by her lovers), she still questions her reflection, focusing on “the terrors it reveals about the self” (Chaney 20). Once again, Alison is holding the photograph in her hands. This time, however, the gesture may be interpreted in a twofold manner: (1) it is either Alison-the-character or (2) Alison-the-narrator that is looking at the photograph “in the present moment.” In any case, as in Fun Home, the photograph is presented simultaneously in the past and in the present (Saltzman 85). This photograph confronts Alison – both as character and narrator, the (former) “object of suffering” and the (present) “subject of artistic production” (Clewell 58) – with a self that is torn between criticism and

self-acceptance. As she points out, Donna titled it “Alison in-between” (Are You 226).

In the context of the entire narrative, the photograph functions as a moment of awakening; through it Alison comes to the realization that her mother has impaired her vision of self. Try as she might to self-correct it, and thus “cure herself” by means of art (Clewell 59), she will never be satisfied with the final image. Alison subsequently confronts her mother; in the following panels, she refuses to listen to Helen speak only about herself and hangs up on her, crying (229). For Heike Bauer, this scene is crucial for understanding the complex dynamics between the two women, as marked by “the dissonance between psychological insight and ongoing feelings of hurt and upset” (276). Alison examines her troubled self in the photographic mirror; however, this interest is not shared by Helen, because, as Alison further observes, “maybe the mother manages to be a mirror only part of the time. In such ‘tantalizing’ cases, some babies learn to withdraw their own needs when the mother’s are evident” (233). Indeed, realizing that her mother will dominate her, Alison learns to “withdraw.” Even though withdrawal may be seen as a failure of self-examination, Tammy Clewell points out that Bechdel “embrace[s] the messy neuroses of her everyday life not as symptoms of psychic disturbance to be resolved,” and ultimately defining “her identity as a graphic memoirist” (53) and as an artist.

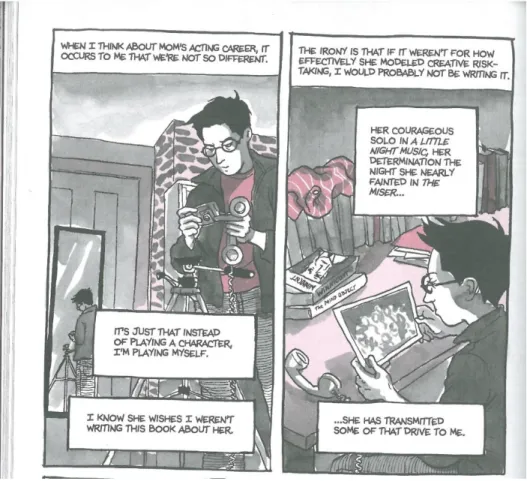

While both photographs of Alison, at the ages of eight and twenty-four, could be classified as Lacanian mirror-images of “self-alienation,” in the intricate narrative woven by Bechdel, a different layer of meaning is also present. In the greater context of the chapter “Mirror,” in which both photographs appear, readers learn that Alison’s mother has worn makeup since she was a teenager and that she “would not be seen without her ‘face’” (214). Alison thus realizes that her mother was also trying to hide her own insecurities behind a face she had invented or, at the very least, altered through makeup. It is strongly suggested that mother and daughter are united in their dissatisfaction with the self and the consecutive need to perform their enhanced self to the world. In the process of “doing and undoing the self in words and images” (Diedrich 184), Alison realizes that she and her mother are “not so different. It’s just that instead of playing a character, [she’s] playing [herself]” (234).

The notion of performing or playing the self also highlights two other points of intersection between Alison and her mother. For one, the reader is once again reminded of the photographic sequence in which Alison for the first time realizes that her narrative of self is performative, that it is subject to her vision (fig. 1). Secondly, it becomes clear that Alison and her mother share an interest in art. A photograph of her mother in an amateur theater group appears earlier on in the narrative (209). Drawn with attention to detail, it occupies a prominent position on the page (it takes up almost two-thirds of the page and is located at the bottom center). Such “site” on the page (Groensteen, System 34) testifies to the importance of the mother, her art, and her performance. This photograph reappears in one more important context, further suggesting that Alison believes that if it were not for her mother’s independence and interest in the arts, she probably would not be a cartoonist (234). A very reflective photographic sequence, which begins with Alison performing in front of the camera frames Alison’s realization that she and her mother are “not so different” (234). Alison is taking a reference photograph, recreating the painful moment when she hung up on her mother. In the next panel, she is pictured behind the camera, looking at the photograph she has taken (interestingly, a huge mirror is also seen behind her) and, finally, the sequence ends with her looking at the said photograph of her mother as a young actress in an amateur troupe (fig. 2). Similarly to other examples discussed above, this image also functions as a self-critical “metapicture” (Mitchell 35), that is an image “that is used to reflect on the nature of pictures,” drawing attention to the complexities of representation (Mitchell 57). The format and arrangement of the two panels (as vertical rectangles, they repeat the shape of the mirror behind Alison’s back; they also mirror one another on the two sides of the page) communicate a “symmetry” between two facing frames based on “oppositions”

and “correspondences” (Groensteen, Comics 50). The panel on the left represents Alison’s engagement with self. The mirror acts as a catalyst for a playful exchange of gazes, which, as mentioned above, points to being at once subject and object, performing and experiencing, being and appearing. It demonstrates that, to paraphrase Chaney, the self “is a construct that only becomes legible in partnership with fabular devices like mirrors” (22).

Figure 2. Alison at work on her memoir from: Bechdel, Alison. Are You My Mother?, 2012, p. 234.

ARE YOU MY MOTHER? by Alison Bechdel. Copyright © 2012 by Alison Bechdel. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt reserves all rights not specifically extended herein.

The panel on the right represents Alison’s engagement with Helen: she is studying and reflecting on the photograph of her mother as an actress. Together, the two panels both complete and oppose one another. In them, mother and daughter are next to one another and yet separate, ultimately invoking “a form of narrative closure that renders material the maternal void of feeling and fills it with cultural production” (Bauer 279). The void left by the mother renders the self both incomplete – the mother, as Alison observes, left in her “a lack, a gap, a void” (287). However, eventually, as Alison demonstrates in her memoir, she “has also given [her] the way out” through art (287-288).

Conclusion

A close examination of the use of photography in Are You My Mother? exposes the complexity of Bechdel’s personal narrative. In this graphic memoir, photographs present as a series of critical encounters with the self that begins with finding and interpreting early childhood photographs in the two-page spread (32-33), then critically reflecting on herself as a child and a young woman (214, 226), and ending with a critical reexamination of her relationship with her mother (209, 234). The photographs reflect a complicated

relationship between the two women, which was crucial for Alison’s development as an individual and an artist. The photograph as mirror in Are You My Mother? paradoxically provides Alison with an unattainable vision of self, but also allows her to stabilize the self through artistic practices. The duality of real and imagined self, the subject and the object, evidence and artificiality, truths and untruths expressed in and through the photograph demonstrates that, as Bechdel repeats after Virginia Woolf in the epigraph to Are You My Mother?, “nothing was simply one thing.”

Bibliography

Barry, Lynda. One! Hundred! Demons! Sasquatch Books, 2002.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Hill and Wang, 1982.

Bauer, Heike. “Vital Lines Drawn From Books: Difficult Feelings in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Are

You My Mother?” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 18 no. 3, 2014, pp. 266-281.

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Houghton Mifflin, 2006. ---. Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama. Houghton Mifflin, 2012.

---. Interview by David Larsen. 2012. The NZ Listener, 1 Sep. 2012,

http://www.noted.co.nz/archive/listener-nz-2012/interview-alison-bechdel/. Accessed 16 Oct. 2018.

---. “Public Conversation: Alison Bechdel and Hillary Chute.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 40, no. 3, 2014, pp. 203-219.

Bruner, Jerome. “Self-making and World-making.” Narrative and Identity: Studies in Autobiography, Self,

and Culture, edited by Jens Brockmeier and Donal Carbaugh, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2001,

pp. 25-37.

Camden, Vera J. “‘Cartoonish Lumps’: The Surface Appeal of Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?”

Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, vol. 9, no. 1, 2018, pp. 93-111.

Chaney, Michael A. Reading Lessons in Seeing: Mirrors, Masks, and Mazes in the Autobiographical

Graphic Novel. The UP of Mississippi, 2016.

Chute, Hillary. Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. Columbia UP, 2010. ---. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Harvard UP, 2016.

Clewell, Tammy. “Beyond Psychoanalysis: Resistance and Reparative Reading in Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?” PMLA, vol. 132, no. 1, 2017, pp. 51-70.

Cvetkovich, Ann. “Drawing the Archive in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 111-128.

Diedrich, Lisa. “Graphic Analysis: Transitional Phenomena in Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?”

Configurations, vol. 22, no. 2, 2014, pp. 183-203.

Dow Adams, Timothy. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. The U of North Carolina P, 2000.

Eakin, Paul Jones. Fictions in Autobiography: Studies in the Art of Self-Invention. Princeton UP, 1985. El Refaie, Elisabeth. Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures. The UP of Mississippi, 2012. Ernst, Nina. “Authenticity in Graphic Memoir: Two Nordic Examples.” The Narrative Functions of

Photographs in Comics, special issue of Image and Narrative, vol. 16, no. 2, 2015, pp. 65-83.

http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/814/619. Accessed 6 Nov. 2018.

Gardiner, Judith Kegan. “Queering Genre: Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and The

Essential Dykes to Watch Out For.” Contemporary Women’s Writing, vol. 5, no. 3, 2011, pp. 188-207.

Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. The University Press of Mississippi, 2007. Groensteen, Thierry. Comics and Narration. The University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

Haverty Rugg, Linda. Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. The U of Chicago P, 1997. Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Harvard UP, 1997.

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph.” The Atlantic Monthly, June 1859,

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1859/06/the-stereoscope-and-the-stereograph/303361/.

Accessed 15 Apr. 2019.

Mikkonen, Kai. “Focalisation in Comics: From the Specifities of the Medium to Conceptual Reformulation.” Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, p. 71-95.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. The U of Chicago P, 1995. Pedri, Nancy. “Cartooning Ex-Posing Photography in Graphic Memoir.” Literature and Aesthetics, vol. 22, no. 2, 2012, pp. 248-266.

---. “Graphic Memoir: Neither Fact nor Fiction.” From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to

pp. 127–153.

Roth, Michael. “Photographic ambivalence and historical consciousness.” History and Theory 48, 2009, pp. 82-94.

Rüggemeier, Anne. “‘Posing for all the Characters in the Book’: The Multimodal Processes of Production in Alison Bechdel’s Relational Autobiography Are You My Mother?” Journal of Graphic Novels and

Comics, vol.7, no. 6, 2016, pp. 254-267.

Saltzman, Lisa. Daguerreotypes: Fugitive Subjects, Contemporary Objects. The U of Chicago P, 2015. Sandbye, Mette. “Looking at the Family Photo Album: A Resumed Theoretical Discussion of Why and

How.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 6, no. 1, 2014, https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v6.25419. Accessed

10 Jan. 2019.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. U of California P, 1990. Small, David. Stitches: A Memoir. W.W. Norton, 2009.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Penguin, 1979.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Pantheon, 1986. ---. Maus: And Here my Troubles Began. Pantheon, 1991.

Watson, Julia. “Autographic Disclosures and Genealogies of Desire in Alison Bechdel’s Fun

Home.” Biography, vol. 31, no. 1, 2008, pp. 27-58.

Whitlock, Gillian. “Autographics: The Seeing ‘I’ of the Comics.” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 52, no. 4, 2006, pp. 965-979.

Małgorzata Olsza holds a Ph.D. in American Literature and an M.A. in Art History from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. Her research interests include comics, graphic novels, contemporary American art, and word and image. Her Ph.D. thesis was devoted to the poetics of the contemporary American graphic novel. She has published on contemporary graphic novels, comics, and the visual narrative in Polish Journal

for American Studies and Art Inquiry: Recherches sur les arts.