Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Poultry Science, 83, December 12, pp. 2039-2043, 2004

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur.

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Maternal dietary ratio of linoleic acid to alpha-linolenic acid affects the

passive immunity of hatching chicks.

Wang, Y. W.; Sunwoo, H.; Cherian, G.; Sim, J. S.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

NRC Publications Record / Notice d'Archives des publications de CNRC:

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=9036eb1f-48db-4085-9377-4c6a6de5d38b https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=9036eb1f-48db-4085-9377-4c6a6de5d38bResearch Note

Maternal Dietary Ratio of Linoleic Acid to α-Linolenic Acid Affects

the Passive Immunity of Hatching Chicks

Y. W. Wang,* H. Sunwoo,† G. Cherian,‡ and J. S. Sim†

,1*Dietetics and Human Nutrition, McGill University, Macdonald Campus, Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada, H9X 3V9; †Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, T6G 2P5;

and ‡Department of Animal Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 97331-6702

ABSTRACT The objective of the current study was to examine the effect of dietary ratio of linoleic acid (LA) to α-linolenic acid (LNA) on the humoral immune response in laying hens and further on the passive immunity of their progeny. Thirty-two Single Comb White Leghorn laying hens, 24 wk of age, were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 diets that had LA-to-LNA ratios of 0.8, 5.4, 12.5, and 27.7, respectively, by changing the proportions of sunflower and linseed oils. After 5 wk on the experimen-tal diets, hens were immunized intramuscularly with 1 mg of BSA, followed by 2 boosters 2 and 6 wk later. Serum and egg yolk were obtained weekly from 0 to 6 wk following the first injection of BSA. One week after the second booster, fertile eggs were collected and incubated. The sera of 11-d-old embryos and hatchlings were

col-(Key words: linoleic acid to α-linolenic acid ratio, laying hen, hatching chick, total immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin G antibody)

2004 Poultry Science 83:2039–2043

INTRODUCTION

Humoral immune response is important in protecting chickens from infectious diseases and facilitating cell-me-diated immune responses to clear pathogens. One group of humoral mediators that accomplish the humoral im-mune responses is antibodies, which have 5 classes. The IgG is the major class of antibodies produced during the second humoral response (Nysather et al., 1976) and is the primary antibody circulating in the blood system. IgG protects chickens by neutralizing antigens and activating the complement system and is frequently involved in opsinization, aiding in the phagocytosis of antigens by macrophages (Nysather et al., 1976).

It has been reported that when broilers are fed a diet containing 12% fat, higher levels of α-linolenic acid (LNA) promote antibody production (Friedman and Sklan,

2004 Poultry Science Association, Inc. Received for publication April 23, 2004. Accepted for publication May 26, 2004.

1To whom correspondence should be addressed: jsim@afns. ualberta.ca.

2039

lected. All serum samples were stored at −20°C before analysis. The results showed that dietary LA-to-LNA ratio had no effect on the total IgG and BSA-specific antibody IgG concentrations in the serum or egg yolk of laying hens. Hatchlings from hens fed the diet containing the LA-to-LNA ratio of 12.4 showed lower (P < 0.05) BSA-specific IgG titer in the serum than those from hens given the diet containing LA-to-LNA ratio of 0.8. A lower (P < 0.05) total IgG concentration was observed in hatchlings from hens fed the diet containing LA-to-LNA ratio of 12.4 compared with those from hens fed diets containing 0.8 and 5.4 of LA-to-LNA ratios. It is suggested that the di-etary ratio of LA to LNA has no effect on laying hen humoral response but affects the passive immunity of hatching chicks.

1995). Increased production of total IgG has been ob-served in the serum and egg yolk of laying hens fed a diet that contained 5% added fat with a high level of LNA (Wang et al., 2000). Fritsche et al. (1991) reported that when pullets are fed a diet containing 7% fat, dietary LNA levels have no effect on antibody production. In these studies, different sources and levels of fat were applied and resulted in different amounts of dietary lino-leic acid (LA), LNA, and other fatty acids. Because satu-rated and monounsatusatu-rated fatty acids have been reported to exert different effects on the immune func-tions (Jeffery et al., 1997; Yaqoob, 1998), the diets used in previous studies might have produced confounding effects of fatty acids on chicken humoral responses. It is important to investigate the effect of LA-to-LNA ratio on chicken humoral immune response by defining the levels of other fatty acids.

A newly hatched chick is heavily reliant on maternally produced antibodies (passive immunity) for its own

im-Abbreviation Key:LA = linoleic acid; LNA= α-linolenic acid; PBST = PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20; WSF = water-soluble fraction.

WANG ET AL.

2040

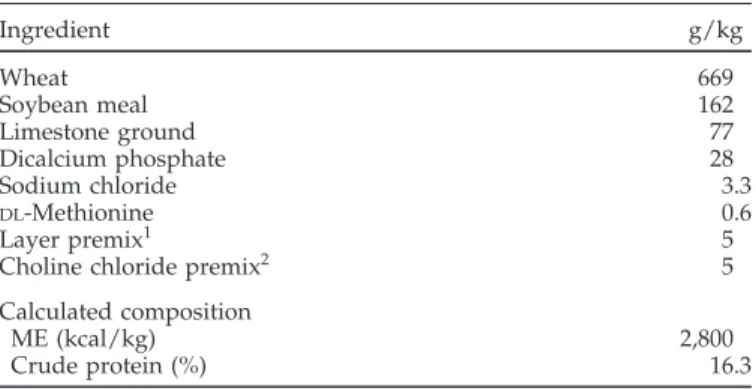

TABLE 1. Composition of laying hen basal diet

Ingredient g/kg Wheat 669 Soybean meal 162 Limestone ground 77 Dicalcium phosphate 28 Sodium chloride 3.3 DL-Methionine 0.6 Layer premix1 5

Choline chloride premix2 5

Calculated composition

ME (kcal/kg) 2,800

Crude protein (%) 16.3

1Layer premix provided per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 12,000 IU; vitamin D3, 3,000 IU; vitamin E, 40 IU; vitamin K, 2.0 mg; pantothenic acid, 14.0 mg; riboflavin, 6.5 mg; folacin, 1.0 mg; niacin, 40.0 mg; thia-mine, 3.3 mg; pyridoxine, 6.0 mg; vitamin B12, 0.02 mg; biotin, 0.2 mg; iodine, 0.5 mg; manganese, 75.0 mg; copper, 15.0 mg; zinc, 80.0 mg; selenium, 0.1 mg; iron, 100.0 mg.

2Choline chloride premix contained (per kg) 34 g of choline chloride (60%) and 966 g of wheat shorts.

mune defense before it becomes immunocompetent, which generally takes about 2 wk (Rose, 1972; Smith et al., 1994). All maternal Ig needed to protect hatching chicks must be present in the egg and transported from the yolk across the yolk sac into the circulation of the developing chicks (Brambell, 1969). IgG is the major Ig in the passive immunity of newly hatched chicks (Tressler and Roth, 1987; Kaspers et al., 1991). The question of whether dietary LA-to-LNA ratio affects maternal em-bryo transfer of total IgG and specific antibody IgG has been raised. Consequently, the primary objectives of the present study were to determine the effects of LA-to-LNA ratio in diet on serum total IgG and antigen-specific antibody IgG concentrations in laying hens as well as on the amounts of total IgG and specific antibody IgG in the circulation of embryos and hatching chicks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Birds and Diets

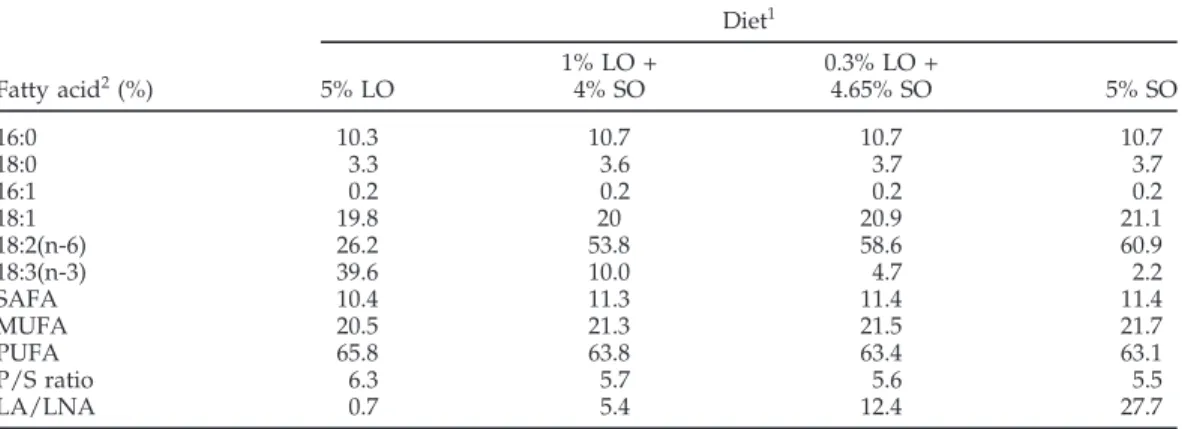

Thirty-two Single Comb White Leghorn laying hens, 24 wk of age, were assigned randomly to 1 of 4 treatments of 8 birds each and were housed in cages (2 hens/cage). The hens were previously fed a wheat-soybean meal based diet (Table 1). During the experiment, the same basal diet was applied and modified to have 5% (wt/wt) added fat in the form of a mix of varied proportions of sunflower and linseed oils. The 4 diets differed mainly in the amounts of LA and LNA and provided LA-to-LNA ratios of 0.7, 5.4, 12.5, and 27.7 (Table 2). Hens were given free access to the diet and water. The experiment was reviewed and approved by the University Animal Policy and Welfare Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines.

Immunization of Hens with BSA

After 5 wk of feeding experimental diets, hens were immunized with 1 mg BSA by injecting into 4 sites of the

breast muscle (2 on the left side and 2 on the right side). BSA was dissolved in PBS and Freud’s incomplete adju-vant emulsion (1:1, vol/vol) at a concentration of 1 mg/ mL. Boosters were given at 2 and 6 wk following the first immunization, respectively.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Blood samples (3 mL) were drawn once a week from 0 to 6 wk after the first immunization; the samples were collected from the wing vein into 5-mL tubes without EDTA. After clotting, the sera were collected by centrifug-ing at 250 × g for 10 min (Fritsche, et al., 1991) and kept at −20°C. Egg samples were taken on the last 2 d of each week. One week after the second booster immunization, hens were inseminated, and fertile eggs were collected and incubated. The sera of 11-d-old embryos and hatching chicks (n = 8/treatment) were obtained and stored at −20°C. All samples were analyzed for total IgG concentra-tion and BSA-specific IgG titer.

Isolation of the Water-Soluble

Fraction of Egg Yolk

Egg yolk IgG is contained in the water-soluble fraction (WSF). After separation from white albumin using a yolk separator, the egg yolk was gently rolled on a paper towel to remove the attached white and transferred to a graduated cylinder. The yolk volume was recorded, and the yolk was diluted (1:6, vol/vol) with acidified deion-ized water (pH 2.5; adjusted with 0.1 N HCl to a pH of 2.5), mixed well and kept at 4°C for 6 h or overnight. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected as WSF.

Antibody IgG Titer by ELISA

The method of ELISA described by Li et al. (1998) was used to measure BSA-specific antibody IgG titer in the

FIGURE 1.Effect of maternal dietary linoleic acid to α-linolenic acid ratio on BSA-specific antibody IgG in the circulation system of 11-d-old embryos and 1-d-11-d-old chicks. For each stage, main effects were ana-lyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. Differences among group means were evalu-ated using the method of least squares means test. Significance level was set at P < 0.05. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8).a,bValues that do not have a common letter are different (P < 0.05). In legend, 0.8, 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7 represent linoleic acid-to-α-linolenic acid ratios in laying hen diets. OD = optical density.

TABLE 2. Fatty acid composition of the experimental diets Diet1 1% LO + 0.3% LO + Fatty acid2(%) 5% LO 4% SO 4.65% SO 5% SO 16:0 10.3 10.7 10.7 10.7 18:0 3.3 3.6 3.7 3.7 16:1 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 18:1 19.8 20 20.9 21.1 18:2(n-6) 26.2 53.8 58.6 60.9 18:3(n-3) 39.6 10.0 4.7 2.2 SAFA 10.4 11.3 11.4 11.4 MUFA 20.5 21.3 21.5 21.7 PUFA 65.8 63.8 63.4 63.1 P/S ratio 6.3 5.7 5.6 5.5 LA/LNA 0.7 5.4 12.4 27.7

1LO = linseed oil; SO = sunflower oil.

2SAFA = saturated fatty acids; MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids; P/S ratio = the ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids; LA = linoleic acid; LNA = α-linolenic acid.

serum and egg yolk. Briefly, 96-well polystyrene plates2 were coated with BSA by adding 150 µL of BSA solution (30 µg BSA in 1 mL of coating buffer3) to each well and then incubating for 1.5 h at 37°C. The plates were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween-204 (PBST). An aliquot (150 µL) of each serum sample (diluted by 1:2,000 for the hen serum, 1:1,000 for the hatchling serum, and 1:100 for the 11-d-old embryo serum in PBS) or egg yolk WSF (diluted by 1:3,000 in PBS) was added in triplicate. The same volume of PBS was used as control. The plates were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C, washed with PBST, and incubated again for 1 h at 37°C with 150 µL of a 1:1,000 dilution of peroxidase conjugated goat antichicken IgG.5The plates were washed with PBST and

added per well with 150 µL of substrate solution, 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)4in phos-phate-citrate buffer6 containing 0.03% (wt/wt) sodium perborate. After a 30-min reaction, the absorbance of mix-ture was read at a wavelength of 405 nm using an ELISA reader in reference to the control. The optical density was used to express antibody titer.

IgG Concentration by Radial

Immunodiffusion

Total IgG concentrations in the serum and egg yolk were measured by the method of radial immunodiffusion (Li et al., 1998). Solution A was prepared by mixing 0.3 mL of rabbit antichicken IgG4 with 0.7 mL of barbital buffer4(50 mM sodium barbital and 10 mM barbital, pH 8.6) and incubating in a 56°C water bath. Solution B was prepared by mixing 70 mg of agarose4 with 4.6 mL of

barbital buffer and 0.4 mL of 0.35% (wt/vol) sodium

2Corning Inc., Corning, NY. 3Contained 1.59 g of Na

2CO3and 2.93 g of NaHCO3in 1 L of deionized distilled water, pH 9.6.

4Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO. 5Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX. 6Contained 9.6 g of C

6H8O7and 14.1 g of Na2HPO4in 1 L of distilled water, pH 5.0.

azide; the mixture was held in a boiling water bath until the agarose dissolved. Solutions A and B were mixed well, equilibrated at 56°C, and poured into the gap between 2 radioimmunodiffusion plates. Aliquots (6 µL) of serum (diluted by 1:10 for hen serum and 1:4 for hatchling serum in PBS), egg yolk WSF (diluted by 1:10 in PBS), and chicken IgG standard4 (0 to 1.4 mg/mL in PBS) were

added to 2.5-mm diameter wells of the gel. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 3 d. The diameter of the precipitation ring was measured. The concentration of the IgG sample was calculated with reference to the standard curve and expressed as milligrams per milliliter.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA using the GLM procedure of SAS software (SAS Institute, 1990). Differ-ences between treatment means were evaluated using the method of least squares means test after a significant main effect by ANOVA. Significance level was set at P < 0.05. The results are presented as means ± SEM.

FIGURE 2.Effect of maternal dietary linoleic acid to α-linolenic acid ratio on the total IgG in the circulation of 11-d embryos and 1-d-old chicks. For each stage, main effects were analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA, and differences between treatment means were analyzed using a least squares means test at a significance level of P < 0.05. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8).a,bValues that do not have a common letter are significant different (P < 0.05). In legend, 0.8, 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7 are the ratios of linoleic acid-to-α-linolenic acid in hen diets.

WANG ET AL.

2042

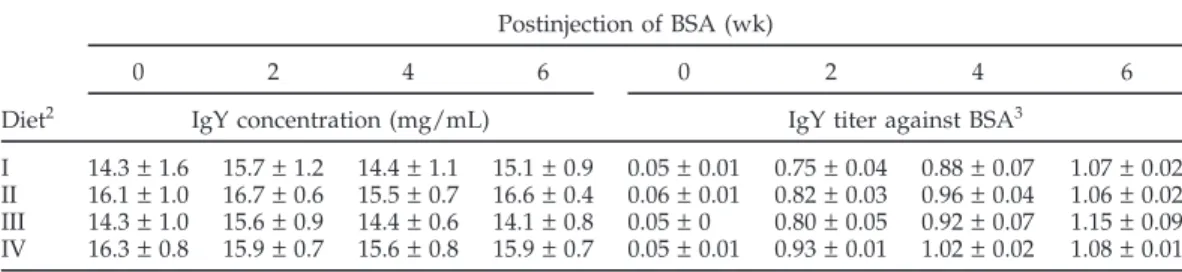

TABLE 3. Effect of dietary linoleic acid to α-linolenic acid ratio on serum IgG concentration and BSA-specific antibody IgG activity in laying hens1

Postinjection of BSA (wk)

0 2 4 6 0 2 4 6

Diet2 IgG concentration (mg/mL) IgG titer against BSA3

I 5.6 ± 0.9 9.8 ± 1.4 9.1 ± 1.3 9.4 ± 1.6 0.05 ± 0 0.50 ± 0.05 0.63 ± 0.12 0.97 ± 0.11 II 5.7 ± 0.7 11.0 ± 1.5 11.8 ± 1.2 11.5 ± 1.4 0.05 ± 0 0.74 ± 0.16 0.83 ± 0.09 1.09 ± 0.10 III 7.5 ± 1.3 9.6 ±. 2.2 8.7 ± 1.1 8.8 ± 2.1 0.06 ± 0.01 0.53 ± 0.09 0.66 ± 0.19 1.23 ± 0.04 IV 6.4 ± 1.3 9.7 ± 2.3 11.0 ± 1.4 9.6 ± 2.0 0.05 ± 0.01 0.69 ± 0.05 0.78 ± 0.09 1.20 ± 0.04 1Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). For IgG concentration and antibody IgG activity at each week, there was no significant effect of dietary linoleic acid to alpha-linolenic acid ratio by one-way ANOVA (P > 0.05)

2Diet I, II, III, and IV contained 0.7, 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7 linoleic acid-to-α-linolenic acid ratios, respectively. 3A dilution of serum by 1:2,000 in PBS was performed.

RESULTS

Primary immunization with BSA elevated total IgG in the serum by 75, 93, 28, and 52% for hens fed diets with 0.8, 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7 LA-to-LNA ratios, respectively. The first booster did not induce a further increase of the serum total IgG. The levels of egg yolk total IgG were not affected by primary immunization or the first booster. The IgG titers against BSA in the serum and egg yolk of the hens were not affected by the ratio of LA and LNA in the diets after primary immunization and the first booster (Tables 3 and 4).

After 11 d of incubation, BSA-specific IgG titer in the embryo serum did not show any difference across treat-ments (Figure 1). Total IgG levels in the embryo serum followed a pattern similar to the antibody IgG and were not different among treatments (Figure 2). Upon hatching, however, the IgG titer against BSA was higher (P < 0.004) in the serum of chicks from hens fed the diet containing LA-to-LNA ratio of 0.8 compared with those from hens fed the diet containing LA-to-LNA ratio of 12.4 (Figure 1). There were no differences in IgG titer against BSA among the hatchlings with maternal dietary LA-to-LNA ratios of 0.8, 5.4, and 27.7 and 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7, respec-tively. The serum total IgG was not different among the hatchings from hens fed diets containing 0.8, 5.4, and 27.7 LA-to-LNA ratios. However, chicks from these 3 treat-ments had higher (P < 0.02) serum total IgG

concentra-TABLE 4. Effect of dietary linoleic acid to alpha-linolenic acid ratio on egg yolk IgY concentration and BSA-specific antibody IgG activity in laying hens1

Postinjection of BSA (wk)

0 2 4 6 0 2 4 6

Diet2 IgY concentration (mg/mL) IgY titer against BSA3

I 14.3 ± 1.6 15.7 ± 1.2 14.4 ± 1.1 15.1 ± 0.9 0.05 ± 0.01 0.75 ± 0.04 0.88 ± 0.07 1.07 ± 0.02 II 16.1 ± 1.0 16.7 ± 0.6 15.5 ± 0.7 16.6 ± 0.4 0.06 ± 0.01 0.82 ± 0.03 0.96 ± 0.04 1.06 ± 0.02 III 14.3 ± 1.0 15.6 ± 0.9 14.4 ± 0.6 14.1 ± 0.8 0.05 ± 0 0.80 ± 0.05 0.92 ± 0.07 1.15 ± 0.09 IV 16.3 ± 0.8 15.9 ± 0.7 15.6 ± 0.8 15.9 ± 0.7 0.05 ± 0.01 0.93 ± 0.01 1.02 ± 0.02 1.08 ± 0.01 1Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). For IgY concentration and antibody IgY activity at each week, there was no significant effect of dietary linoleic acid-to-α-linolenic acid ratio by 1-way ANOVA (P > 0.05)

2Diets I, II, III, and IV contained 0.7, 5.4, 12.4, and 27.7 linoleic acid-to-α-linolenic acid ratios, respectively. 3

A dilution of egg yolk water-soluble fraction by 1:3,000 in PBS was performed.

tions than those from hens fed the diet containing an LA-to-LNA ratio of 12.4 (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Diets containing 5% added fat and varied ratios of LA to LNA (from 0.8 to 27.7) did not exert significant effects on serum and egg yolk total IgG concentrations in laying hens. This result differs from our previous study, which showed increases of total IgG concentrations in the serum and egg yolk after feeding hens with a similar basal diet containing 5% linseed oil compared with the same amount of sunflower oil or animal oil (Wang et al., 2000). In a study reported by Wang et al. (2000), the diets con-tained different levels of each saturated, monounsatur-ated, and polyunsaturated fatty acid. This finding may indicate that immunomodulatory effect of dietary LA-to-LNA ratio on serum and egg yolk total IgG concentrations could be modified by the nature of saturated and mono-unsaturated fatty acids in laying hens. The BSA-specific IgG titers in laying hen serum and egg yolk were also not affected by dietary LA-to-LNA ratio. A similar result has been reported by Fritsche et al. (1991), who found that when feeding pullets with a corn-soybean meal diet containing 7% (wt/wt) lard, corn oil, canola oil, or linseed oil, the ratio of LA to LNA did not affect serum antibody IgG titer against sheep red blood cells. Contradictorily, Friedman and Sklan (1995) reported that when broilers

were fed a soybean meal-corn-wheat diet containing 12% (wt/wt) of fat with low levels of LNA (ranging from 1.4 to 1.9%), the antibody IgG titer against BSA was decreased with the increase of LA-to-LNA ratio (11.8 to 30.8). The differences in chicken strains, ages, dietary ingredients, and levels of LA, LNA, and other fatty acids used make direct comparisons among these studies problematic.

It is very interesting that, upon hatching, the chicks from hens fed a diet with 12.4 of LA-to-LNA ratio had the lowest serum IgG titer against BSA. The total IgG concentration in hatchling serum followed a pattern simi-lar to that of IgG titer against BSA, indicating an associa-tion between BSA-specific antibody IgG and total IgG, or in other words, the amount of antibody IgG is transferred from the yolk to the embryo in proportion to total IgG. It has been demonstrated in previous studies that maternal antibodies cross the yolk sac intact (Kramer and Cho, 1970; Rose et al., 1974), which occurs via a selective, recep-tor-mediated mechanism (Brambell, 1969; Linden and Roth, 1978). The binding activity of IgG to the receptors on the yolk sac membrane reaches the highest in the third week of incubation (Tressler and Roth, 1987; Kaspers et al., 1991). In accordance with these findings, the present study showed that the transportation of total and anti-body IgG from egg yolk into the circulation of hatching chicks occurred mainly between 11 d of development and hatching (Figures 1 and 2). Results of the current study implicate that LA-to-LNA ratio may influence the binding activity of IgG-receptor on the yolk sac membrane and thus affect the maternal-embryo transfer of yolk IgG. It is also impossible to exclude the effect of egg yolk LA-to-LNA ratio on the half-life of IgG in the embryo, which alters the serum total and antibody IgG concentrations.

It is well established that passive immunity is critically important to newly hatched chicks in their early immune defenses while the chick’s immune system is developing (Rose, 1972; Smith et al., 1994). The increased total IgG and specific antibody IgG in the embryo circulating sys-tem during the incubation with the increased LNA or decreased LA-to-LNA ratio could benefit young chicks by improving the capability of immune defense and, thus, improve profitability in the chicken industry. More exper-iments are warranted to explore the mechanisms through which maternal LA-to-LNA ratio influences the total IgG and specific antibody IgG in the circulation of hatching chicks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Ottawa, Can-ada) for research funding support. We thank all staff in the Poultry Unit, University of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) for assistance in chicken care.

REFERENCES

Brambell, F. W. R. 1969. The transmission of immune globulins from the mother to the foetal and newborn young. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 28:35–41.

Friedman, A., and D. Sklan. 1995. Effect of dietary fatty acids on antibody production and fatty acid composition of lymphoid organs in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 74:1463–1469. Fritsche, K. L., N. A. Cassity, and S. C. Huang. 1991. Effects of

dietary fat source on antibody production and lymphocyte proliferation in chickens. Poult. Sci. 70:611–617.

Jeffery, N. M., P. Sanderson, E. A. Newsholme, and P. C. Calder. 1997. Effects of varying the type of saturated fatty acid in the rat diet upon serum lipid levels and spleen lymphocyte functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1345:223–236.

Kaspers, B., I. Schranner, and U. Losch. 1991. Distribution of immunoglobulins during embryogenesis in the chicken. Zen-tralbl. Veterinarmed. A 38:73–79.

Kramer, T. T., and H. C. Cho. 1970. Transfer of immunoglobulins and antibodies in the hen’s egg. Immunology 19:157–167. Li, X., T. Nakano, H. H. Sunwoo, B. H. Paek, H. S. Chae, and

J. S. Sim. 1998. Effects of egg and yolk weights on yolk antibody (IgY) production in laying chickens. Poult. Sci. 77:266–270.

Linden, C. D., and T. F. Roth. 1978. IgG receptors on foetal chick yolk sac. J. Cell Sci. 33:317–328.

Nysather, J. O., A. E. Katz, and J. L. Lenth. 1976. The immune system: Its development and functions. Am. J. Nurs. 76:1614–1618.

Rose, M. E. 1972. Immunity to coccidiosis: Maternal transfer in

Eimeria maxima infections. Parasitology 65:273–282.

Rose, M. E., E. Orlans, and N. Buttress. 1974. Immunoglobulin classes in the hen’s egg: The segregation in yolk and white. Eur. J. Immunol. 4:521–523.

SAS Institute. 1990. SAS User’s Guide: Statistics. Version 6.12. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC.

Smith, N. C., M. Wallach, C. M. D. Miller, R. Morgenstern, R. Braun, and J. Eckert. 1994. Maternal transmission of immu-nity to Eimeria maxima: ELISA analysis of protective antibod-ies induced by infection. Infect. Immun. 62:1348–1357. Tressler, R. L., and T. F. Roth. 1987. IgG receptors on the

embry-onic chick yolk. J. Biol. Chem. 262:15406–15412.

Wang, Y. W., G. Cherian, H. H. Sunwoo, and J. S. Sim. 2000. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids significantly affect laying hen lymphocyte proliferation and immunoglobulin G con-centration in serum and egg yolk. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 80:597–604.

Yaqoob, P. 1998. Monounsaturated fats and immune functions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 57:511–520.