Batwara:

Partition and the City of Amritsar by

Pitamber P. Sahni

Diploma in Architecture (1999)

Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Gurgaon, India

Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science in Architecture Studies

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2003

© 2003 Pitamber P. Sahni. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Degree of MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY

JUL 0 2 2003

LIBRARIgES

Signature of Author Department of Architecture May 22, 2003 Certified by JJu in Beinart Professor of Architecture Thesis Advisor Accepted byIu\i-+l

Beinart

Chairman, Department Comt tee on Graduate StudentsReaders:

Alice H. Amsden

Barton L. Weller Professor of Political Economy Department of Urban Studies and Planning Heghnar Watenpaugh

Assistant Professor of the History of Architecture Department of Architecture

Batwara:

Partition and the City of Amritsar

)y Pitaiber P. Sahni

Submiitted to the Department of Architectutire inl

Partial FulfiInent of the Requiremen ts for the

Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies

ABSTRACT

The Partition of British India into the two dominions of India and Pakistan on August 1 5th 1947 left in its wake the largest human migration of the twentieth century with the transfer of twelve million people across two newly formed borders. The boundary line, demarcating Indian and Pakistani territory, was created 17 miles to the west of Amritsar awarding the city to India. Amritsar, a flourishing commercial and cultural center, thus, became a border city overnight on the Indian side. Mass religious emigration ensued clearing the city's Muslim population of over 184,000 people coupled with the immigration of a huge Hindu-Sikh population from Pakistan over a period of a few months.

This thesis explores how Partition affected the city of Amritsar. Its metamorphosis from a viable commercial and cultural center to a city that shows a decline in population post-partition for the first time since its inception is partially explained by its proximity to the International Border, its vocational and demographic shifts and its official label as a transit city. The thesis documents communal migration, both inter- and intra-city, from March 1947 to the mid 1950s with the arrival of Hindu and Sikh refugees from West Punjab. This thesis then cross-references Amritsar with Lahore, a border city in Pakistan to explore how and why Partition affected that city differently. Amritsar is finally then seen through the lens of rising Sikh nationalism in the 1980s and its effect on the urban fabric. This thesis concludes with general inferences that can be drawn from the experiences in Amritsar as a case study of a city transformed by an unplanned and immediate forced resettlement.

Thesis Supervisor: Julian Beinart Title: Professor of Architecture

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost I would like to thank my Advisor, Julian Beinart for his guidance through the thesis. His patience and criticism have been instrumental in shaping this document to make it what it is. Additional thanks to my readers, Alice Amsden and Heghnar Watenpaugh for their encouragement and key observations that have taken this document further than I thought possible. Finally, I would like to express

my gratitude to Ian Talbot from Coventry University for his interest, time and articles.

I would like to thank all those in Amritsar who offered me their time and support - the Rampal family for taking me in and showing me their city in January of 2003, Professor Balwinder Singh and Gopal Johri from GNDU for their assistance in procuring theses and making sense of the governmental maze; and finally, Amandeep Sandhu from the Town Planning Office for her help in obtaining the requisite maps and information.

To Edna Bhandari, Kasturi Lal Sharma and Basant Lal, thank you for letting me into your lives and

speaking to me about them.

In Delhi, the offices of Gurmeet Rai and DKS - Poonam, Leon and Smita, thank you for your help

with the ground-work. To the staff at the National Archives, I salute your unbending ways.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge all those who supported me through this endeavor; my family

and friends in Delhi, New York and London, and all those here at MIT who made coming here an all the -1

To my grandparents

Who made the move and survived.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONEIntroduction

11CHAPTER TWOBeginnings I Amritsar: Pool of Nectar

19

CHAPTER THREEExodus I March - August 1947

39

CHAPTER FOUR.Arrival I August 1947 - Mid 1950s

CHAPTER FIVEExplication I Amritsar

93 AnalyzedCHAPTER SIXReflection

119EPILOGUE

125APPENDIX

I Interview Transcripts 127CREDITS I Illustrations and Tables

139

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ONE Introduction

Fig. 1. Map of Post-Partition India showing India, West Pakistan and' East Pakistan.

The Partition of British India, also known as the Batwara or "divide" was a turning point in the history of the Indian subcontinent. The "greatest human migration in history"' saw the movement of 12 million people across the newly formed border between India and Pakistan and an estimated loss of one to two million lives in the process. This movement was sited on the West

by the division of the state of Punjab - west Punjab being apportioned to Pakistan and the East awarded to India. In addition, Partition divided the state of Bengal, with the West granted to India and the East to Pakistan2 (Fig. 1).

Politicians on both sides intended the creation of two independent nations to be a glorious moment in time. However, Partition, designed to prevent communal upheaval3, quickly led to the severest of bloody and contested territorial clashes between the Hindu/Sikh and Muslim communities on both sides of the border.

Punjab as a state was particularly problematic in any discussion where Partition and the creation of Pakistan were suggested. The state in its entirety could not be handed over to India or Pakistan due to the significant inter-mixing of the communities

-not only within the cities, but in the entire central tract of the state. The added factor of a significant Sikh population, a third major religious group, made the division all the more complex.

The city of Amritsar epitomizes one such communally contested space within this central tract. Prior to Partition in 1947 into the two dominions of India and Pakistan, Amritsar was a thriving metropolis with a fine-grained religious fabric spread throughout

the city; Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs inhabited the city living adjacent to each other, often in the same localities. According to the 1941 Census of India, Amritsar was dominated by three major religious groups - Muslims accounted for close to 48 percent of the total, Hindus made up approximately 35 percent, while the Sikhs consisted of 16 percent of the population of the city.

Prior to 1947, Amritsar was a major commercial and cultural center with a cosmopolitan population. Its location along the Grand Trunk Road, the principal trading route that ran from Kabul in Afghanistan right up to Calcutta in Bengal ensured its commercial viability within the state of Punjab. Amritsar was one of the three major cities in the state based on the size of its population - the other two being Lahore and Delhi.4

In August 1947, with the creation of the International Boundary 17 miles to its west (Fig. 2), Amritsar witnessed a massive transformation of its population. The city changed drastically from a community of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs prior to Partition to a seemingly homogenous society of Hindus and Sikhs through the exodus of the entire Muslim community and the arrival of Hindu and Sikh refugees post-Partition. This changed the population into a coarse-grained religious and social demographic that spread itself to inhabit every corner of Amritsar.

THESIS QUESTION

This thesis poses the following question: Fig 2 Map of Punjab showing the new

How did Partition affect the city of Amritsar? boundary line and the location of Amrtisar

Prior to Partition, Amritsar lay in the central tract of Punjab. I hypothesize that the transformation of Amritsar into a border city 12

as a repercussion of its proximity to the dividing line between the two dominioris led to the immediate decline of the city due to a number of reasons. I further infer that this was a common feature throughout the border district in cities in both countries - India and Pakistan.

METHODOLOGY

Few texts exist which document the growth of the city of Amritsar. Anand Gauba's work is the one of the principal texts which traces the growth of the city and has been referenced for its urban history from 1577 to 1947. A number of texts document the general conditions in East and West Punjab in the run-up to Partition and the years immediately following and have been quoted throughout this thesis - Satya Rai and Dr. Kirpal Singh are the most notable authors who have contributed significantly to documenting post-Partition Punjab. There is, however, little documentation of the growth of Amritsar in particular through the early days of Post-Partition India. Scarce government documents, refugee stories, and newspaper articles from 1947 are some of the main sources of information used to make sense of this city under siege.

To gain insight into the city and study the population shifts the city underwent, three people were personally interviewed in Amritsar in January 2003. Out of these, two were refugees and one was a witness to the shifting communal tides within the city. They

are all present residents of Amritsar.

Edna BhandAri: A resident of the city since 1941, Edna Bhandari

arrived in India from England in 1936. She first came to Lahore where she lived for five years before moving to Amritsar with her

husband, an Indian lawyer whose family was part of the elite in Amritsar. She witnessed the change in the city through the events of 1947 and beyond. She is currently 90 years of age.

Kasturi Lal Sharma: A refugee at the age of twelve, Kasturi Lal Sharma arrived in Amritsar with his parents and siblings from rural Sialkot in Pakistan a few days after Partition was declared. He and his family were one of the thousands of refugee families who settled in Amritsar in the first wave of arrival. They moved to the walled city and settled down in one of the evacuee properties left behind

by the fleeing Muslim families. He still lives at the same property

with his extended family.

Basant Lal: Basant Lal moved to Amritsar with his parents in 1956 from Peshawar, Pakistan as a ten year old boy. He and his family represent the second wave of refugees that populated Amritsar in the 1950s rather than immediately after the 1947 Partition. They

settled down in a new suburb of the city, outside the walls along the Grand Trunk Road. The creation of these new localities in the outskirts of the city by biradiris (kinship groups), who made the move to India collectively, is typified in his story. He is currently a doctor living and practicing in the same locality as where he first moved when he came to Amritsar.

It should be noted here that the refugees interviewed had made the move to Amritsar when they were very young. Yet, these interviews show a remarkable clarity of events - an indication that possibly, their memories are not entirely their own. Perhaps their memories have been shaped partly by what they experienced, but also by stories recounted to them by their elders. Thus, the memories recounted are dual voices speaking - their own generation's as well as their parents'. Therefore there is a certain lack of objectivity in the process - a feature however, that, I argue is to be expected when

Fig. 3. Kasturi Lal Sharma (seated, center) surrounded by his family at his home in Moti Ram Katra, Amritsar.

talking of severely traumatic events.

These three stories characterize the myriad faces that represent the city. They have little in common save for the fact that they witnessed the events of 1947 either in India or in Pakistan and that they all made Amritsar their home as a direct or indirect result of Partition.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Chapter two of the thesis, "Beginnings", describes the urban history of Amritsar from its inception in 1577 to March of 1947

-the beginning of major communal riots in -the city. It traces the city's urban growth through the rule of the Sikh gurus and Misls, the Mughals, Maharaja Ranjit Singh and finally the British. In

addition, this chapter documents the political development in the state of Punjab which caused and subsequently affected growing Hindu/Sikh-Muslim tension and the rising demand for a separate Muslim state.

Chapter three, "Exodus", details the evacuation of the entire Muslim population of Amritsar between March to August of 1947 after the certainty of the creation of the Muslim state of Pakistan is realized. Communal shifts of population in the city are documented through a series of maps depicting inhabitation zones and clusters of the Muslim community within the city.

Chapter four, "Arrival", maps the Hindu and Sikh refugee communities which migrated from West Punjab into India. Through 0 the lens of refugee accounts and newspaper articles, the location of the Hindu and Sikh communities within the city is discussed along with the governmental infrastructure that supported the rebuilding of Amritsar. The East Punjab Government's policies of Urban Renewal

in the walled city are highlighted through a case study of the neighborhood of Moti Ram Katra to emphasize the role of the state in shaping the rehabilitation of the city. Finally, a shifting religious demographic and its repercussions on decline of industry within the city are analyzed.

The principal reasons for Amritsar's decline as a city are elaborated upon in the penultimate chapter, "Explication". Upon further examination of the issue one finds that the decline of Amritsar was peculiar to Amritsar itself; that Lahore, located just 26 miles away on the Pakistani side, experienced a different fate. While Amritsar suffered a period of decline, Lahore saw an upsurge in population in the immediate years following Partition. The reasons for this disparity are analyzed and conclusions are made to explain this inconsistency. Finally, Amritsar is seen through the lens of rising Sikh nationalism in the 1980s and the identity of the city reverts back to its primary identity as the holiest site of the Sikhs

-its germination point in the late 1 6th century. Through this time, the issues of memory in the city and the lack of a physical memorialization of Partition are raised and its motives questioned.

"Reflection", the final chapter, brings to light general conclusions which can be drawn from the experiences of Amritsar that can be applied to cities that undergo sudden and severe transformation by an unplanned and immediate forced resettlement.

NOTES

' Corruccini, Robert S. and Kaul, Samvit S., Halla: Demographic Consequences of the Partition of the Punjab, 1947, University Press

of America. 1990, pl.

2 East Pakistan gained independence from Pakistan in 1971 after a Civil War. It is presently known as Bangladesh.

3 Corruccini, Robert S. and Kaul, Samvit S., Halla: Demographic Consequences of the Partition of the Punjab, 1947, University Press

of America. 1990, pl.

4 As of the Census of 1941, Delhi had the largest population of close

to 918,000 people; Lahore was second with 671,659 inhabitants while Amritsar ranked third in the state of Punjab with 376,824 residents. Out of these three cities, Amritsar was the only one which showed a decline in population in the Census of 1951.

TWO

Beginnings

Amritsar: The Pool of Nectar

"I'm Mrs. Edna Bhandari wife of Mr. Ramesh Chandra Bhandari, Barrister at Law. I'm 90 years old and I've

been a resident of Amritsar for the last 64 years... not of

Amritsar... Lahore... let me say India. I came out to India in 1936. First I was living in Lahore and then I

moved to Amritsar probably in 1940-1941 - something like that. So I was here all through the days of the

Partition...all through the riots... all through the

refugees..."

- Interview respondent Edna Bhandari, Bhandari

House, Court Road, Amritsar, January 19, 2003.

The Partition of India and Pakistan and the resultant division of the states of Punjab and Bengal left its mark on the hearts and minds of millions of people forced to abandon their homes for the sake of a new homeland that was officially appropriated to be theirs based solely on their religious beliefs.

What is central to the story in Punjab is the fact that the process of Independence from close to a century under British rule is not remembered as joyous an occasion as one would expect. The word 'independence' is seldom used to describe that traumatic period

in history for Punjab. 'Partition' and the painful memories of its events are what are ingrained in the hearts and memories of people. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonancel explains to some extent the recounting of memories of refugees who made the move across the border at the time. The situation refugees were forced to bear; to have to choose between two incompatible beliefs and/or actions is not uncommon. Over a brief period in time a neighbor from a different religious entity had turned into the enemy. Over a brief period of time what was for centuries your home was no longer officially yours. Over a brief period of time your country was no longer your own.

Edna Bhandari's confusion concerning Amritsar, Lahore and India with what is India and what is not is proof of the fact., The two cities of Lahore and Amritsar, both within Punjab and separated by a mere 26 miles, were once part of the same state but came to represent two different countries and two different peoples.

As a result of Partition Amritsar came to be sited just 17 miles from a newly created border between the two dominions of India and Pakistan. The city underwent a dramatic metamorphosis as a direct result of the divide. While these changes primarily took place from

March 1947 onward, the history of the city and the politics of the BATALA

region left certain warnings as to what to expect in the years to come.

The setting of the piece, so to speak, created the story. - , SRTS

THE SETTING

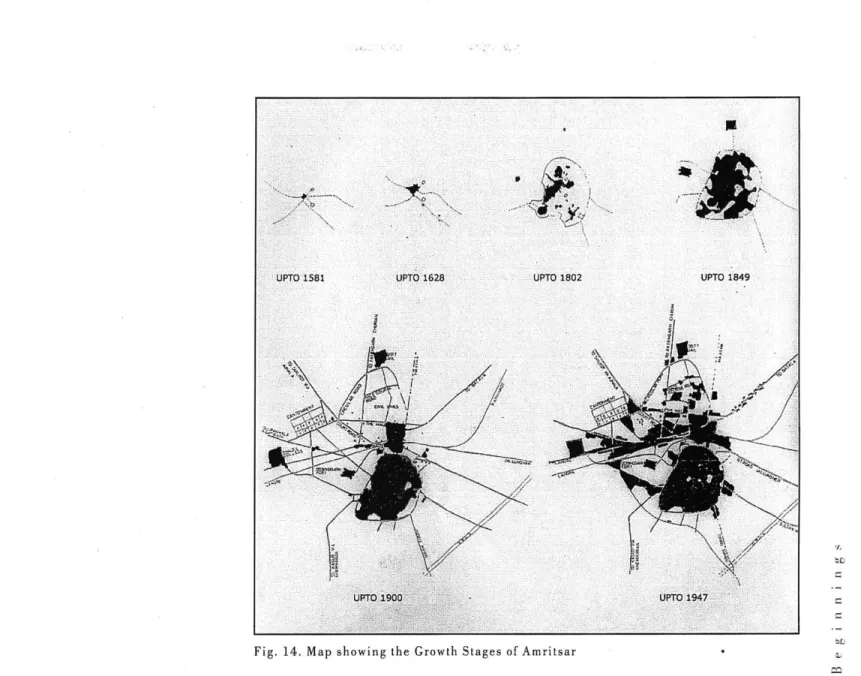

The city of Amritsar - literally meaning 'pool of nectar' has a rich and varied history. From its inception in the late 1 6th century

a

to the present day, the city has undergone a great deal of change. Fig. 4. The site for the city of AmritsarEstablished by the fourth Sikh Guru, Guru Ram Das in 1577, the specific site of Amritsar (Fig. 4) was chosen for a number of 20

SANTOKH

SAR

RAMDAS SAROVAR

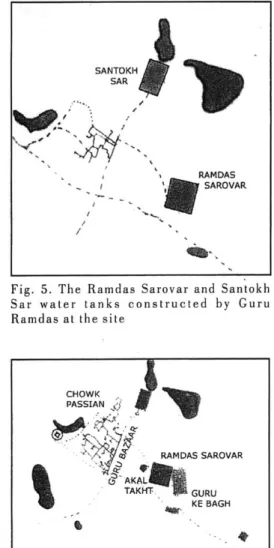

Fig. 5. The Ramdas Sarovar and Santokh Sar water tanks constructed by Guru

Ramdas at the site

Fig. 6. Ramdaspur Development upto 1628

reasons. Traditionally, cities have located themselves alongside water resources and Amritsar was no exception. Situated between the rivers Ravi and Beas on either side along a principal trade route, the site was approximately 26 miles east of the city of Lahore.

The Sikh gurus laid the foundation of what would come to be known as the Golden Temple as early as 1573 with the construction of two water tanks by Guru Ramdas ( Fig. 5). After his death, his son Guru Arjan Dev completed the construction of the tanks and concerned himself with the expansion of the town. He built his residence which came to be known as Guru Ka Mahal alongside this tank. At that time, the city was known as Ramdaspur (named after Guru Ramdas) and soon attracted a small settlement to locate itself right next to Guru Ka Mahal. The plan for the Hari Mandir (later to be known as the Golden Temple) was conceived by Guru Arjan Dev which he decided would be built in the middle of the tank.

Located on the principal trade route and now the home of the Sikh Guru, Ramdaspur (Amritsar) came to attract traders from the areas surrounding Punjab. The traders were organized by Guru Arjan Dev into locating themselves on particular streets according to their caste and trade.2

The settlement of these trade families in the immediate vicinity of the Hari Mandir led to the natural formation of a trade street which came to be known as Guru Ka Bazaar3 (Fig. 6). This street is still in existence in Amritsar and is one of the principal markets of the walled city even today.

Amritsar under the Sikh Misls

The Mughals had by now been in India from the early 1500s. The third emperor Akbar - known for his religious tolerance among Hindus and Muslims - had great respect and shared a cordial

relationship with Guru Arjan Dev. Upon Akbar's death and his son Jahangir's ascension to the throne, matters changed. Growing animosity between the Sikhs and the Mughals led Jahangir to sentence Guru Arjan Dev to death.

Growing Sikh-Mughal tension due to Guru Arjan Dev's killing led to the militarization of the Sikhs by Guru Arjan Dev's son, the sixth Guru - Guru Hargobind. He built a small fortress to the west of the city and created a small army. The guru also formed the Akal

Takht4

which was the political seat of the Sikhs formed largely due to the introduction of the Mughals into the city of Ramdaspur. He, however, had to leave Amritsar in 1628 due to the might of the ruling Mughals and was never to return.

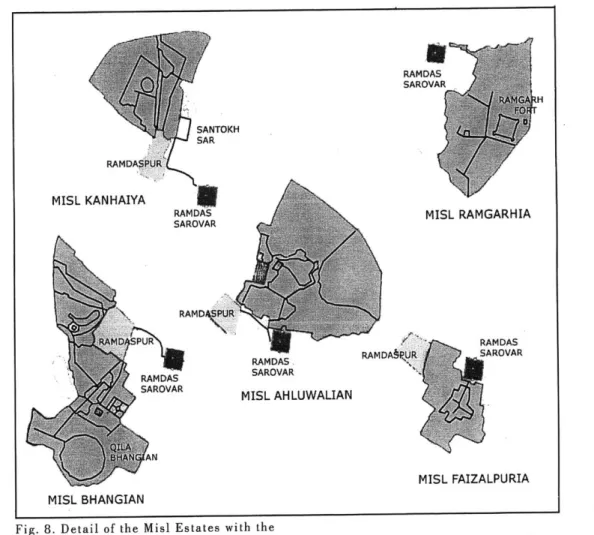

The next hundred years saw a period of anarchy in the city. After the death of the last Sikh guru in 1708, the city came under siege of the Mughals and the invading Afghans. The Sikhs organized their military forces into an army known as the Dal Khalsa. This army had 12 branches or misls. Each misl was considered equal to the other. The Sikh Misls established their independent sovereignty in Punjab and retained joint control over the city of Amritsar. The Sardars or heads of the Misis gained influence and occupied the areas surrounding the temple. They established their estates or katras and fortified them with walls. Each katra became the territory of that particular misl. The katras were, however, not interconnected. They all radiated out from the temple as its starting point. The underlying idea of this approach was that in order to go from one katra to the other, one would have to go first to the Hari Mandir and then enter the other katra, thus physically, spatially and experientially

reinforcing the Hari Mandir as the originator and organizing force of the city5 (Fig. 7, 8).

The physical growth of the city took off during this period. Land was given for free in the katras to attract prospective settlers.

RAMDAS SAROVAR * SANTOKH SAR MISL KANHAIYA MISL RAMGARHIA PUR4 RAMDAS SAROVAR RAMDAS SAROVAR RAMDAS. SAROVAR MISL AHLUWALIAN MISL FAIZALPURIA MISL BHANGIAN

Fig. 8. Detail of the Misl Estates with the katras demarcated in them.

Fig. 7. Misl Estates around Ramdaspur

(1764-1802)

23

RADAS

Amritsar as a city became a poly-nuclear system with the katras soon expanding. Within each nucleus, growth was however, relegated to a linear pattern along the principal commercial street with offshoots in either direction for the residential enclaves.

From the early 1800s to the middle of the century Amritsar came under the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh who took over Amritsar in 1803. Up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the misls had grown considerably in Punjab. However, this growth had been accompanied with jealousy and rivalry between the Sardars of the misis. Serious infighting between them rendered Amritsar weak and left it open for Ranjit Singh's army. Two Misis that were extremely powerful and influential at this time were the Ramgarhia Misl and the Ahluwalian Misl - both of which had established their katras in the city. In 1803, following the death of the leader of the Ramgarhia Misl - Sardar Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, "a contract of friendship (was) signed between the Ramgarhia family and Ranjit Singh in Amritsar before the Granth (Sikh holy men). Ranjit Singh stamped the papers with his open palm dyed with saffron... went to the Ramgarh fort and succeeded in capturing it with his artillery"6.

Amritsar Under Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Under Maharaja Ranjit Singh's reign, the city of Amritsar developed considerably. Although Lahore remained his political capital, Ranjit Singh made Amritsar the spiritual and commercial center of his empire. He encouraged a great number of the nobles from his Lahore court and big merchants to settle in Amritsar. As a

e

result, the development of the katra continued further. New katraswere developed by the king's courtiers in and around the existing katras of the misis. Some new katras that were formed in this period 24

Fig. 9. Development of the Walled City under Maharaja Ranjit Singh showing the new katras.

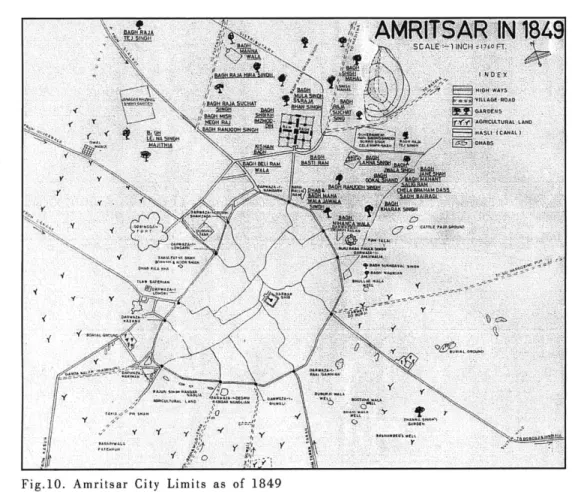

are Katra Karam Singh, Katra Hakima, Katra Mil Singh and Katra Sher Singh (Fig, 9). In addition to the development of the katras, Amritsar also saw the building of the Gobindgarh Fort in the North West and the Rambagh Gardens in the North. Amritsar began to thrive as a center for trade and commerce. Its location on the Grand Trunk Road was fully exploited.

It was only in, 1821 that the actual walls of the city came into being. Massive double walls were erected by the Maharaja to defend the city from future attack. The Hari Mandir which from now came to be known as the Golden Temple was renovated and covered with copper plates. Amritsar was further reinforced as the Sikh religious center.

In the early 1850's the population of Amritsar was enumerated as 100,466 with the Muslims accounting for approximately 40,000 of those inhabitants.7 This number was partly due to an influx of Kashmiri Muslims since the 1830s. They formed about half of the Muslim population of Amritsar. The balance of the Muslim populace came during the reign of the Maharaja.

"Thus one could find Muslim traders and shopkeepers in the heart of the old city like Bazaar Sheikhan adjoining Guru Bazaar. But Muslims in general had

mostly settled in the outermost quarters of the city, close to the wall like katras Khazana, Hakiman, Karam Singh, Garbha Singh. Relatively speaking, the Hindus and Sikhs who together constituted only a little more than half the population of Amritsar, were mostly the older inhabitants

of the place. These localities clustered around the nucleus and in old Amritsar in large numbers"'

GOBINDGARH FORT

Fig.10. Amritsar City Limits as of 1849 showing the development outside the Walled City

Fig. 11. Map showing the development within the Walled City as of 1849.

Amritsar Under British Rule

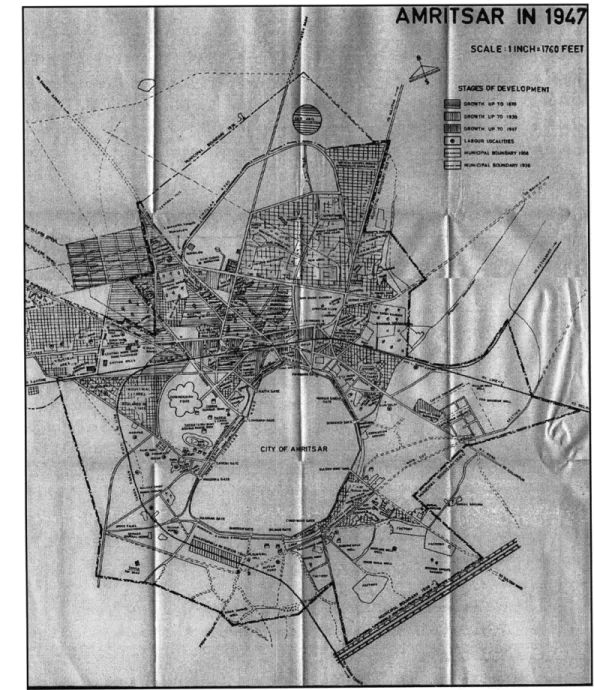

The British arrived in Amritsar in 1849 when they annexed Maharaja Ranjit Singh's sphere of influence. The army cantonment was established soon after in the extreme north west of the north zone 9. It was during this time period that Amritsar saw maximum growth (Fig. 12, 13).

The Kashmir famine of 1883 caused a further influx of Kashmiri Muslims to the city. There was a paralleled growth in terms of trade and commerce as well as the spread of the city. With the arrival of the Kashmiris, the carpet trade began to flourish in Amritsar after the 1880s. 0 Wool played an important role in terms of exports at the time. Amritsar also became the primary center of trade in India of grains and flour in the twentieth century." In addition, Amritsar became an important manufacturing center for textiles, leather and

iron and steel work right up until 1947.

In terms of city growth, the entire area north of the walled city was developed by the British. Amritsar's location along the trade route of the Grand Trunk Road made it a prime location for colonial administrative units, providing a route to other parts of Punjab and the sub-continent." Industry had located sporadically along the Grand Trunk Road towards the west of the city leading to Lahore. The labor colonies mostly congregated near the industry to the west of the city. Slums sprang up alongside the highway, the railway corridor and the wall.' 3

In terms of demographic locational splits, "the posh

localities [north] were dominated by Christians and Hindus while Muslims managed to settle on the outskirts

[west] or in the slum-like low lying areas"4

Fig. 13. Map showing the developments within the Walled City as of 1947

Fig. 12. Amritsar City Limits as of 1947 showing the development outside the Walled City

28

Fig. 14. Map showing the Growth Stages of Amritsar

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN. PUNJAB

In the following years, as can be expected, the politics of the region affected the city of Amritsar considerably. Prior to 1909, there was no guaranteed representation of minorities within the provinces. The right of representation granted to the Muslims in 1909 which spread to other minorities in 1919 led to the rise of communal consciousness". Punjab was one of the only regions that had a major Muslim population - 57% according to the 1941 census in the entire state. Sir Malcolm Darling, the Assistant Commissioner of Punjab at the time, wrote in his article "At Freedom's Door" that "nowhere is communal feeling potentially so dangerous and so complicated as in the Punjab...complicated because there is a third and not less

obstinate party - the Sikhs".

The Muslims were in actual fact, the majority in the region, however, economically, the non-Muslims dominated. In addition to the non-Muslims owning more than half of the total industrial establishments in Punjabl6 , the Sikhs were the biggest land owners in the central districts. Over and above agriculture, money lending was the most important commercial activity in the province which was entirely 'in the.hands of the Hindus and the Sikhs.

The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms(1919) and The Indian Act(1935) The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919 which granted reservations for communities for representation set off a chain of events that would lead to the demand for a separate Muslim state.

The reservation of seats for Muslims and Sikhs in the Punjab assembly

brought in its wake nation-wide agitation and intensified the struggle for freedom, however, creating along with it a divide between the

communities1 7

. The establishment of the Akali Party of the Sikhs in 1920 and the Unionist Party - a party of land-holders (primarily Muslim - with a few Hindu and Sikh representatives) in 1923 was a direct result of the Reforms. The Muslim League had already been established in India in 1906.

Apart from the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms, the Indian Act of 1935 is seen as the "starting point" of proceedings that led to the Partition of India in 1947.18 The Act sought to maintain the unity of India by federating the total number of princely states (close to 600 of them) together with the eleven British provinces and providing a method of self-governance to the latter. This first part of the Act remained unresolved due to the breaking out of the Second World War in 1939. The second half of the Act though, which spoke of self-governance for the British provinces had a major impact on the changing face that was to become India and Pakistan and was put into force.

The Act proposed to give power, in each of the British Provinces, to an Indian Cabinet and ministry responsible to an elected legislature. Power was still to be retained in the hands of the Governor who was appointed by the British to preserve peace and protect the minority communities. In order to protect the minorities, the Imperial British government provided separate electorates for the minority communities. Introduced in 1892 for the Muslims, by 1935 this had extended itself to Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians and Europeans. Among the provinces controlled by the British were the provinces of Punjab and Bengal with a majority Muslim population of 57% in the case of Punjab and 54% in Bengal19.

The immediate repercussion of this was the reinforcement of a communal divide in India. With the establishment of separate electorates based on religious lines, there was a newfound

reexamination of the political debris of India. Authority which had been long fought for on the very site of the subcontinent over centuries between the Hindus and the Sikhs on one side and the Muslims on the other in the avatars of the Hindu Kings and Sikh Gurus and the Mughals was being translated into the present and being fought for all over again. India seemed to have become a land of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims who were suddenly seeing the differences between their communities in a new light.

THE RISE OF MUSLIM SEPARATISM

Separate electorates were the germination seed for the idea of a separate state for Muslims. However, this is true for the demand for a Sikh state as well. The Muslim League called for a consolidated North-Western State consisting of Punjab, North West Frontier, Baluchistan and Sind for the Muslim electorate.2 0

This would have, however, led to the division of the Sikh population. The idea of a territorial rearrangement of the province that would consolidate the Sikh population to counter this move was suggested. Proposals and counter-proposals flew back and forth between the Sikh and the Muslim political parties right up till 1943 when the Pakistan Scheme o was being fervently discussed at the All - India level. The demand for a separate Sikh state would become a major issue later in April of 1947 in the run-up to Independence in August.

The idea of an actual separate state for the Muslim community, however, only came about in March 1940 when the Muslim League proposed the establishment of Muslim-majority states in the North

a

West and North East of India. It was further in 1946 that the proposal for that being one sovereign state with an eastern and western wing was actually made formally.2'THE PUNJAB ELECTIONS OF 1946

Elections were held in 1946 in which the Muslim League under the leadership of Mohammad Ali Jinnah2 2 fared extremely well. They captured 79 out of the 86 seats reserved for Muslims, The Congress captured 51, the Panthic Akali Sikhs 22 and the Unionists and Independents garnered 10 each. Thus, the Muslim League established itself as the largest single party in the Punjab Assembly. However, it wasn't enough to form a government. The diametrically opposite politics of the League when compared to those of the Congress, Akalis and the Unionists made a coalition with any of them impossible. As a result, the Congress, Akalis and the Unionists got together to form a coalition government under the leadership of Malik Khizr Hayat Khan.

The ongoing tension that ensued in Punjab was a direct result of the Muslim League being left out of the ruling government. They were determined to establish "undiluted Muslim rule" over Punjab". To maintain peace in ever increasing volatility, on January 2 4th of 1947 the ruling government imposed a ban on the Muslim National Guard and the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh"14

- both extreme right-wing political parties of the Muslim and Hindu community respectively. The League saw this as an affront to their civil liberties and was supported by the Communist Party in its agitation following the ban.

The movement was at its most intense in Lahore and Amritsar. The population of Amritsar at that time was 376,824 out of which 184,055 were Muslim, 134,000 were Hindu and 58,769 were Sikh . The Muhammadan Anglo Oriental College in the city became the headquarters of the agitation. Large processions went out daily from the college. The Khair-ud-Din Masjid, the largest mosque in the city, was another rallying point. While the Muslim rallies in the city were

predominantly peaceful, the Sikhs saw them as an attack on a friendly government that formed a barrier to the creation of Pakistan26. The flying of the Muslim League flag on public buildings in the city caused further Sikh resentment. Due to the extent and severity of the agitation, the ban had to be lifted four days later on the 28th of January.

By February, a couple of weeks later, the situation was at its worst. The League's agitation particularly against the Unionists was at its peak. The declaration by the British Government on the 20 th of February stating the transfer of power to India further intensified the League's struggle to get their demand for a separate state agreed upon. The death of a Sikh constable four days later on the 2 4 h of February by a Muslim mob in Amritsar led the Akali Leader Master Tara Singh to claim that the League was fighting a communal rather than a political campaign.27

He demanded that the state of Punjab be returned to its earlier rulers - the Sikhs - to avoid a civil war.

Further agitation between the Muslims on one side and the Hindus and Sikhs on the other forced the resignation of the Khizr Hayat - led government a week later on the 3rd of March.

Thus, we see the trajectory of the growth of a city from its early origins as the birthplace of Sikhism into a fiercely contested o urban space in 1947 between the Muslims on one side and the Hindu and Sikh communities on the other. The contestation was a direct repercussion of the rise in demand for a separate Muslim state. Where traditionally, the different communities had enjoyed close civic and emotional ties, that very site had been transformed into an area of dispute. It was to wreak havoc in the city of Amritsar in the months to come.

NOTES

Festinger L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance Theory developed by Leon Festinger (1957) is concerned with the relationship among cognitions. Two cognitions are considered

consonant if one follows from cr fits the other. The theory states that when two cognitions are dissonant, and are experienced as an unpleasant drive state, the individual is motivated to reduce it by

either changing cognitions to make one consistent with the other, by adding one cr more consonant cognitions to reduce the

magnitude of dissonance or by altering the importance of the dissonant cognitions.

2 The Duggals settled in Gali Duggalan (lane of the Duggals), the Uppals in Gali Uppallan and so on.

3 Market of the Guru

' Seat of the Akalis

5 The katra had a definite settlement pattern which was universal

throughout the city. Each had a small bazaar for food and other essential commodities. The katra was the site for each Sardar to build his own haveli. All katras had one principal street off of which there was unplanned and unsystematic growth of the katra. This was the principal street with its head at the vicinity of the Hari Mandir (Golden Temple). The unplanned growth of the katras gives Amritsar its present configuration of narrow and winding streets on account of them being essentially pedestrian at this time.

6 Datta, V.N., Amritsar- Past and Present, Amritsar: The Municipal Committee, 1967. p2 3

7 Gauba, Anand. Amritsar: A study

in

Urban History, Jalandhar: ABS Publications, 1988. p2 58 Ibid p2 5

9 Ibid p4 4

10 Ibid p320

" Ibid p320

12 Purewal, Navtej K., Living on the Margins: Social Access to

Shelter in Urban South Asia, Ashgate, 2000. p4 6 13 Ibid p57

14 Ibid p57

15 Singh, Kirpal. The Partition of the Punjab, Publication Bureau Punjabi University Patiala. Second Edition 1989, p5

16 Ibid p6

" Rai, Satya M., Partition of the Punjab: A Study of its effects on the Politics and Administration of the Punjab (I) 1947-56, New

York: Asia Publishing House. 1965. p3 3

18 Philips, C.H. and Wainwright, Mary Doreen (ed.), The Partition

of India: Policies and Perspectives 1935-1947, M.I.T. Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1970.

19 Philips, C.H., The Partition of India 1947: The twenty-fourth

Montague-Burton lecture on International Relations, Leeds University Press, 1967. p5

o 20 Rai, Satya M., Partition of the Punjab: A Study of its effects on

the Politics and Administration of the Punjab (I) 1947-56, New

E- York: Asia Publishing House, 1965. p3 6

21 Pandey, Gyanendra, Remembering Partition, Cambridge

4- University Press, 2001. p2 1

22 Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer by profession, joined the All

India Congress in 1906. He moved to the Muslim League in 1913 while still serving with the Congress. Early in his political career he was chiefly concerned with achieving independence for a united India. He however, became increasingly worried that

36

British oppression might be replaced by Hindu oppression upon Independence. He resigned from the Congress in 1919 and turned his focus to Muslim interests. By the late 1930s Jinnah had

become the leader of the Muslim League and was the architect of the idea of a partition of the country. In 1940 the League adopted the 'Lahore Resolution' which called for separate autonomous

states in Muslim-majority areas of India. Upon Partition, Jinnah became the first President of Pakistan.

2 3Rai, Satya M., Partition of the Punjab: A Study of its effects on the Politics and Administration of the Punjab (I) 1947-56, New York: Asia Publishing House, 1965. p 41

24 The RSS. Literally meaning 'National Volunteer Group' 25 Census of India 1941

26 Talbot, Ian, Locality and Partition: The Muslims of Amritsar and

the 1947 Division of the Punjab

27 Ibid.

THREE Exodus

March - August 1947

"In March the riots started in Amritsar between the

Hindus and the Muslims... we stood on the roof of the Bhandari Bungalow [on Court Road, outside the walled city] and the whole sky was lit up with red. So many [sic], I should say, a quarter of Amritsar city was in flames at that time... there was a lot of trouble. In 3 or

4 days the army came in and the curfew was put on for a

number of days. No one could move out - whether you

had food, whether you didn't have it - that was no

concern of theirs. Gradually things calmed down a bit.

Life went on, but not normally at all."

-Interview respondent Edna Bhandari, Bhandari House, Court Road, Amritsar, Janauary 19, 2003.

The period from March to August of 1947 saw a period of intense unrest and conflict in Amritsar between the Hindu and Sikh r communities versus the Muslims. It was during this period that the

entire Muslim population of the city was forced to evacuate and leave o

behind their properties in a city they had once called their own. The following chapter shall further document the political scenario in the state and the country as a whole and shall speak of reasons

for the Muslim emigration. It shall then reference these political movements and events in terms of the Muslim relocation and intra-city migration that followed in the intra-city of Amritsar itself.

It would be erroneous to say that the change in Amritsar's city form as a result of Partition started after Partition itself. The resignation of the Khizr Hayat Government in March of 1947 unleashed a wave of communal tension in Punjab. The Akali leader Master Tara Singh was incensed by the resignation of Khizr Hayat succumbing to pressure from the Muslim League. The idea of "Muslim Raj (Rule)" in Punjab went a step further by this show of strength of the League in Punjab politics. The unsheathing of his sword on the steps of the Punjab Assembly building in Lahore' in response to the resignation of the government is seen as the catalyst for the violence in Punjab that was to ensue. Khushwant Singh in his article "Lahore, Partition and Independence" equates Master Tara Singh's unsheathing of his sword and his cries of "Pakistan Murdabaad" (Death to Pakistan) to 'hurling a lighted matchstick into a room full of explosive gas'. 2 Violent calls for Sikh rule made by the President of the Shiromani Akali Dal,3 Giani Kartar Singh on the evening of the resignation further instigated a Sikh community concerned about the prospect of being an under-represented minority in a power struggle between the Muslims and the Hindus.

Lahore as the provincial capital of the state of Punjab greatly influenced the fortunes of Amritsar. Due to its proximity to the city, (Fig. 15) repercussions of events taking place there were easily felt in the entire region. Therefore it would be prudent to establish the situation in Lahore due to the ripple effect it would have in the state. The first riots of this period started in Lahore. A group of Hindu students clashed with police outside Government College followed

by an attack on a police station the morning following Khizr Hayat's

Fig. 15. Map of Undivided Punjab

superimposed on the current boundaries of

India and Pakistan showing the locations

of Amritsar and Lahore

resignation.4 A group of about two to three hundred Hindus and Sikhs undertook a procession in the Anarkali bazaar of Lahore denouncing the creation of Pakistan and forcibly hauling down Muslim League flags from Muslim shops.5 The afternoon saw the burning of Hindu business establishments in the walled city in Lahore. A curfew was enforced but, by the 6th of March, many Hindu properties in the walled city had already been torched in retaliation while most of the casualties were Sikhs. The Muslim attacks in Lahore were primarily on Hindu property and not on the Hindus themselves. Hindus however, responded with bomb-throwing and stray stabbings.6 Out of 82,000 houses in the Lahore Corporation Area, 6000 houses were burned down during these disturbances.7 It is estimated that three thousand perished in the violence in West Punjab in the spring of 1947.

Through the following months, large masses of Hindus and Sikhs were now fleeing Lahore and much of the Muslim-majority areas in West Punjab. To try and arrest the exodus of Hindus and Sikhs from Lahore, the Tribune, a major newspaper in Punjab ran the following editorial on its front page in May:8

To Lahore citizens:

1. Don't run away from Lahore like cowardly deserters. Stay at your posts and defend your sweet homes. Get back immediately to your houses, if you have left them. 2. You may remove your womenfolk and

children, clothes and valuables to safe places, but YOU should on no account leave your houses. You should consider them your castles and fight like soldiers from there, determined to save civilization

3. Those who flee betray and weaken those who stick to their guns. Not a single able-bodied man should leave Lahore.

The Partition Council would pass a resolution later on 2nd

August to contain the exodus and encourage people to return to their homes on both sides of the border.9

CONTRASTING METHODS OF VIOLENCE

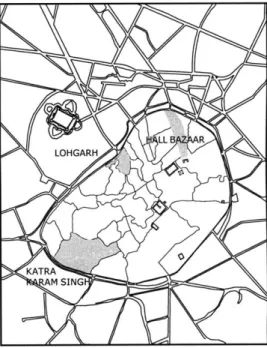

Amritsar was directly affected by the unrest in Lahore 26 miles away. Rioting had begun in the city on the 5th of March and soon

became more serious than the situation in Lahore. Large swaths of the Hindu commercial areas in Hall Bazaar, Katra Karam Singh and Lohgarh were seriously hit (Fig. 16). Shops were systematically looted and burned by Muslims from neighboring localities. The Muslim National Guard, whose banning by the Khizr Hayat government along with the RSS, had been the precursor to the events of March was seen as a major role player in orchestrating the violence in Amritsar against the Hindu and Sikh community.'0 The Golden Temple was used as a sanctuary to house approximately 50,000 people who had been rendered homeless or were afraid for their lives. Alongside the attacks on Hindus and Sikhs, four thousand Muslim shops and homes were destroyed within a single week in March 1947 within the walled city of Amritsar." The torching of Hindu and Sikh businesses by the Muslim community can be understood to some degree by the prevalent social dynamics of the time. The Hindu and Sikh community were, generally speaking, wealthier than the Muslims. The Muslim community in the city consisted mostly of the artisans, craftsmen and industrial labor force

Fig. 16. Hall Bazaar, Katra Karam Singh and Lohgarh within the Walled City

in the iron and steel works and leather and tannery industries. The Hindu and Sikh community, in contrast were the wealthier land owners and traders of the city. It is argued that this torching of commercial establishments was symbolic of the Muslim antagonism towards the non-Muslims - the poor pillaging the shops and warehouses of the rich." The attack seemed more class oriented; religion just added fuel to the fire.

The attacks in Amritsar and Lahore prove this to a large extent. The major areas that were continually burnt in Amritsar were the markets of the Hindu and Sikh community - most notably in Hall Bazaar, at the northern edge of the walled city of Amritsar (Fig. 15). Lahore, likewise saw large-scale burning of Hindu and Sikh shops and homes. The June 22nd attack on Shahalmi, a Hindu and Sikh trading stronghold in the walled city of Lahore, in which a majority of the locality was razed to the ground, is seen as a major turning point in the mass exodus of Hindus and Sikhs from the city."

The attacks on the Muslims by the Hindus and Sikhs were, in sharp contrast, seen to be more personal and physical in nature. The greater incidences of Hindu and Sikhs assaults on Muslims personally could be linked to the concept of 'pollution'." Talbot, in his book "Freedom's Cry" writes about the perception of Muslims by Hindus as 'unclean' - only to be eradicated by death. The Muslims on the other hand regarded the Hindus as infidels thus, not a motivating factor for attacking on grounds of impurity. These, however, are theories of motivation - and no theory 'fits' neatly as a reason for the nature of inter-sectarian violence in Punjab. What does come across is the marked difference in the ways that the Hindu, Sikh and Muslim communities were targeted in Amritsar.

As of May 16, 1947 a total of 209 people had been killed and 422 injured between March 5 and May 16 in the Amritsar riots.'"

Lahore and Amritsar were, however, not the only cities to experience 43

communal strife - all of Punjab's major cities - Lahore, Amritsar, Multan, Jhelum and Rawalpindi reported major damage. Hindus and Sikhs were particularly targeted in these attacks. In Rawalpindi and Multan, the attacks were fiercer, more sudden, and more savage than ever. In the rural areas attacks were launched by large mobs of Muslim peasants who banded together from several hamlets and villages to destroy and loot Sikh and Hindu shops and houses in their area. 16 There were heavy casualties prompting a considerable exodus of refugees towards Central and East Punjab and Delhi. By the end of April 1947, the official estimate of refugees in Punjab was 80,000 people.'7

The Rawalpindi massacres as they came to be known brought a flood of refugees into Amritsar and a fleeing Hindu and Sikh population took refuge in the walled city. However their injection into the city fabric had a peculiar effect. Upon arrival, they brought with them stories, some accurate and some exaggerated, of intense atrocities committed against their communities by the Muslims. The city saw the militarization of the Sikhs and their subsequent call to arms to 'claim the city that was rightfully theirs'. In a letter from Sir Evan Jenkins, the then Governor of Punjab between 1946-47, to Lord Mountbatten on 9 April, 1947, he mentions the establishment of a 'war fund' and the large scale manufacturing of kirpans18

(swords)

by the Sikh community in Amritsar. Exaggerated reports of the

violence in Rawalpindi along with the above contributed to the cease of normal community existence in Amritsar.

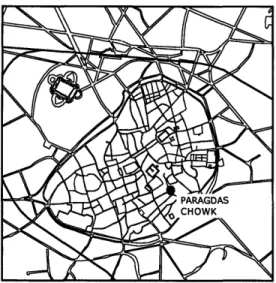

Fig. 17. Paragdas Chowk located half-way between the Golden Temple to its left and Gilwali Gate to the right

Fig. 18. (Clockwise from top) Hall Bazaar, Chowk Lachmansar and Qila Bhangian

PARAGDAS CHOWK

The Partition of the Punjab was a territorial issue in every sense of the word. This was played out at all levels - both nationally and at the city level. A classic case where this was played out was in Chowk Paragdas - barely three hundred meters from the Golden Temple in the heart of the walled city of Amritsar (Fig 17).

The incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees from the Rawalpindi massacres had settled down in the areas surrounding Paragdas Chowk after the resident Muslims had evacuated the area following disturbances in the city on the 7th of March. The Paragdas Mosque

located at the Chowk had been burnt by the Hindu-Sikh mob during that riot and was situated in the midst of the newly occupied Hindu-Sikh localities, though on its right it still had a vast Muslim dominated stretch ending at the Gilwali Gate (Fig. 17). On Friday, April 11h, a congregation of four to five thousand Muslims authorized

by the Deputy Commissioner of Police approached the burnt-down

mosque under police protection to offer prayers. After offering prayers, riots broke out between the Muslims and the Sikhs in which nineteen persons were killed and more than sixty injured.' 9 The riots also saw the burning of Hindu and Sikh houses in several areas including Qila Bhangian, Chowk Lachhmansar, Chowk Chira and Hall Bazaar (Fig 18).

The Paragdas Chowk incident is indicative to understanding the social dynamics of the city at the time and how it translated itself into a physical manifestation in terms of appropriation of civic space in the city. The event came to represent the fracture of a heterogeneous community across an entire city-scape.

Paragdas Chowk, a locality which had, prior to the communal tensions of the era, been one with an intermixed religious community saw itself transformed from that to one which was primarily Hindu

and Sikh due to their arrival en masse from Rawalpindi. Through the last transformation, the religious icon of the space [the mosque] had been destroyed for all practical purposes. The basic aim of the "communal war of succession "20 and the ensuing ethnic cleansing that was going on all through Punjab at the time was to make it impossible for a rival community to continue living in a territory claimed for the majority. Therefore, the re-appropriation of the destroyed mosque as an Islamic icon seemed to be absolutely necessary to the Muslim community - with due reason.

It is important to note that the case of Amritsar was all the more peculiar because of the fact that there was no clear majority or minority in the city. Hindus and Sikhs were seen as one community; all the texts of the time refer to the population of the city as Muslims and non-Muslims - the distinction between the Hindus and the Sikhs appears to be unnecessary and superfluous according to many authors of that era. History seems to ignore the differences between the Hindu and the Sikh community as far as the problem in Punjab at the time was concerned. Amritsar prior to partition in the 1941 census showed a Muslim population that comprised close to 48% of the total city's people. The issue of majority and minority therefore played itself out not in terms of the city in its entirety but instead in the localities of the city that were predominantly Hindu, Muslim or Sikh or intermixed as the case may be.

Up until this time, the Hindu and Muslim communities had

resided side by side. They found themselves sharing the same katras in the walled city. Some katras ended up being dominated by one community over the other in terms of numbers; however this domination seems to be more a by-product of occupation rather than conflicting religious beliefs themselves. Relationships between the Muslim community and non-Muslims were cordial; social interaction 46

was commonplace. One refugee interviewed said that "they attended each other's marriage ceremonies".21

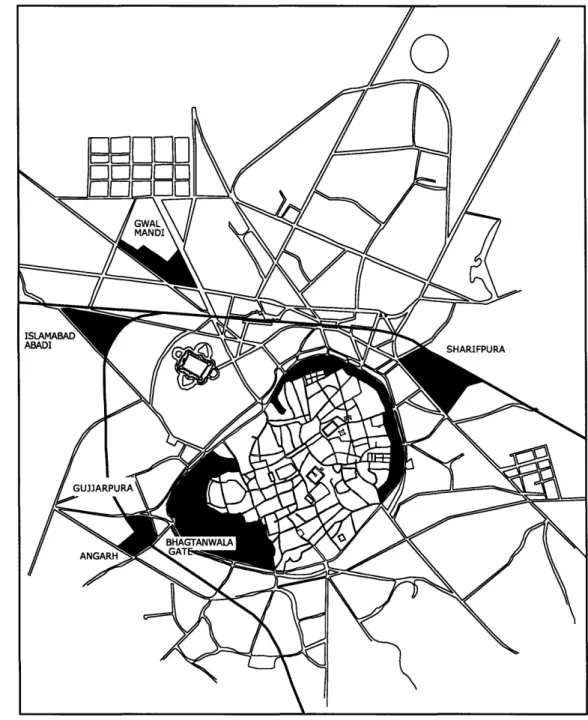

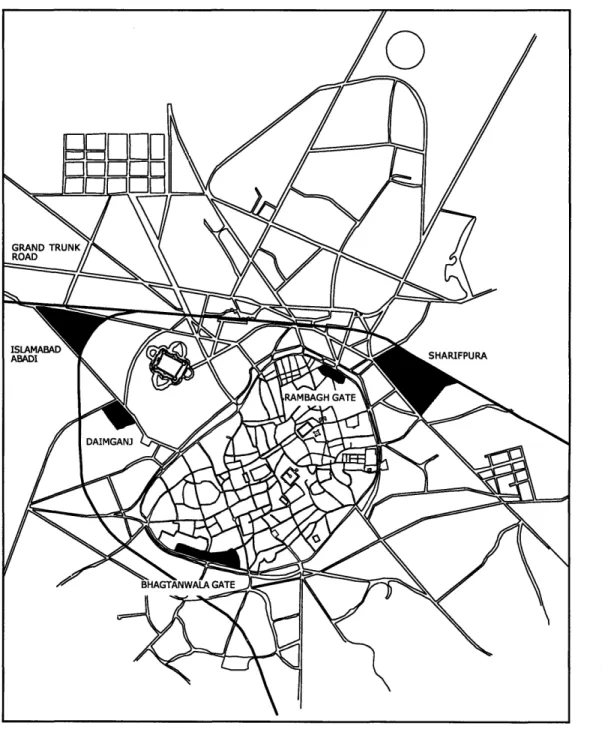

INTRA-CITY MUSLIM RELOCATION

Once the tensions in the city had risen to such a heightened state, the Muslim community evacuated their previously established isolated pockets (Fig. 19) within the walled city to larger enclaves. They moved to the areas around Chowk Farid, Kucha Dabgaran, Rambagh Gate and Bhagtanwala Gate within the walled city. Some Muslims also ventured out to the suburbs of the city - such as Daimganj, Risalpur and Sharifpura (Fig. 20). Sharifpura's location is telling in that it is bounded by the Grand Trunk Road on the south and the Railway line connecting Amritsar to Lahore on the north. As

of March 1947, this was the largest Muslim cluster in the city with a

population of close to 25,000 people. This siting of the Muslim cluster would prove beneficial in the months to come when it would be time to evacuate the city. The numbers would also increase.

Risalpur, one of the sites of the Muslim relocation, came under attack by the Sikhs on May 2 4th. The Sikhs used grenades and trucks

against the Muslim community here killing many witnesses in the Paragdas Chowk case.2 2 One argument is that the attack had another

purpose though; one more psychological rather than physical 3 . It

made it clear to the Muslim community that guaranteed safety was not to be found outside the city; the suburbs were as unwelcoming

to the community as were the confines of the walled city.

Fig 19. The principal Muslim inhabited clusters within the walled city as of March 1947. The clusters shown represent a majority of Muslim inhabitants in those

particular areas. The Hindu and Sikh

majority areas were closer to the core of the city in the surroundings of the Golden Temple and towards the North and

North-West of the city outside the City Walls.

Fig 20. Muslim intra-city clustering into new and existing Muslim majority clusters with the density of these isolated pockets intensified.

Fig. 21. Map of Pre-Partition Punjab showing Muslim Majority areas in the entire state.

Fig 22. The Radcliffe Award (closeup) in the state of Punjab showing the location of the line with respect to Amritsar and Lahore.

THE PARTITION PLAN AND THE BOUNDARY COMMISSION

The riots had shown that Punjab was particularly problematic in any discussion where Partition and the creation of Pakistan were suggested. The entire state could not be handed over to one side over the other due to the significant inter-mixing of the communities - not only within the cities, but in the entire central tract of the state (Fig. 21).

It was the Partition Plan put forward by the Governor-General of India Lord Mountbatten on the 3rd of June that made the actual

Partition of India a certainty. Included in the plan was the note that the details of the partition of Punjab and Bengal were to be worked out by separate Boundary Commissions on the basis of contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims, and not on the basis of the existing district, tehsil or thana administrative units. The plan was agreed upon by all the communities in India and by Mohammad Ali Jinnah on behalf of the Muslim nation in India.

The Boundary Commission set upon their task and used the 1941 census as a referencing tool in order to ascertain Muslim and non-Muslim majorities. Until the Boundary Commission had been put into effect, the provisional boundaries based on the census were to be used. Therefore, the Muslim majority area was to comprise of the Lahore division (excluding district Amritsar), Rawalpindi and Multan divisions. The non-Muslim area was to consist of Ambala and Jullundur Divisions in addition to Amritsar district of Lahore Division.

The Punjab Boundary Commission was set up on the 30th of

June overseen by Sir Cyril Radcliffe.26 It was expected that the o

Commissions" would give their decisions by the 1 5th of August, 1947 - the date set for Independence.