Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Technical Paper (National Research Council of Canada. Division of Building

Research), 1964-03

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC : https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=9f745cee-0ea2-44f2-beae-7ad6f51e30f1 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=9f745cee-0ea2-44f2-beae-7ad6f51e30f1

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/20374149

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Prefabrication in Canadian Housing

,r,,rr'j#,rl

S e r T H I N 2 7 t 2 n o . 1 7 2 c ? B L D GNAITOI{AI RESEA.RCH

COUNCT],

CAT{ADA

DIVISION OF BUIIDING RESEARCH

PREFSBRICAfION

CAIIADIAS HOIJSISG

Platts

Technlcal

P a p e r N o . I 7 Z

of the

B u l l d i n 6 R e s e a r c h

OTTAWA

March 1964

R .

IN

by

n u .D t v i s l o n o f

PRET'ACE

Housing research ls one of the chlef responsibillties of the Divielon of Buildlng Research and this is reflected ln many of the projecte undertaken within the Divielon. Becauee of thie concern with houelngr the growth of prefabrication - the appllcation of factoty proc-e8aea to house constructlon - has been watched with particular intereat. Although this interest ls of long standing, it was not until 1959 that a start could be made ln an intenslve study to ascertain the position of prefabrication ln Ganadian houslng, In 1959, a country-wide survey of prefabricatlon in Ganada was begun but other preesing cornrnltments took precedence and it has not been poeslble to qomplete the report on the results of the survey unttl now.

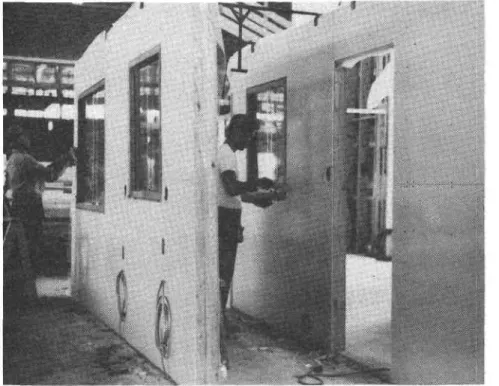

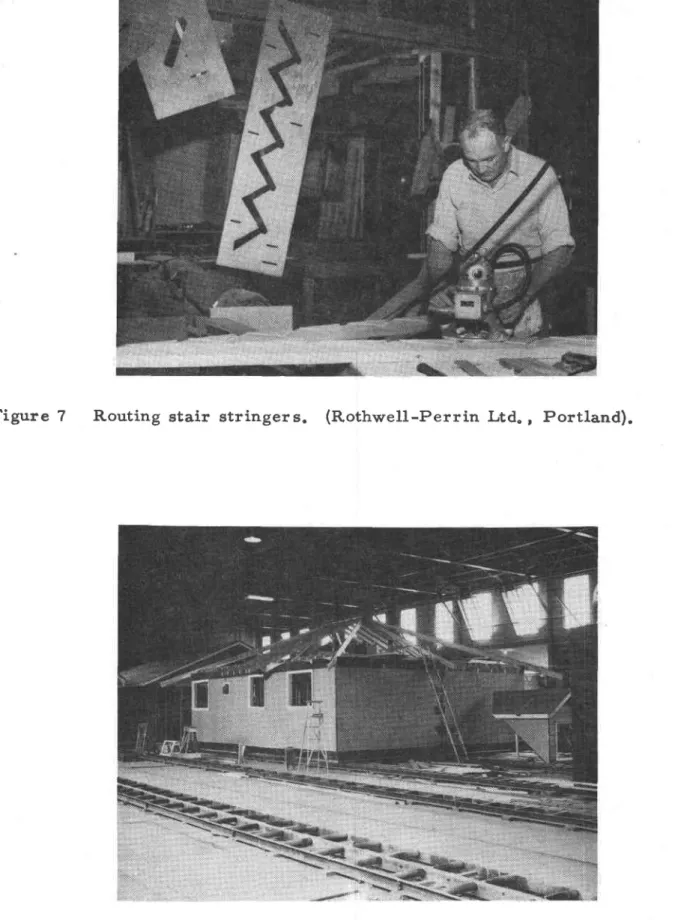

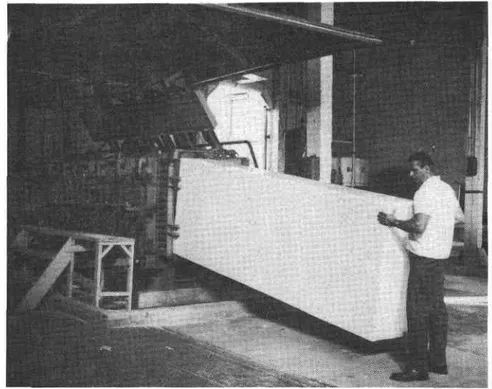

This report ls rnalnly based on inforrnatlon obtained by the author durlng hls vislte to prefabrlcatore. Thelr continuing co-operatlon and franknese ln dlscussion has been of ineetlrnable value in completing thla report. Appreclation ls also here recorded to the firmg that allowed the author to publleh photographs taken durlng Fome of his vielts. These photographs appear at the end of thls report.

This report attempte to define the present statue and evaluate the future role of factory houeing in Canada. Frorn the lnvestigations lt ls clear that several aspects of prefabricatlon ln Canada are worthy of further study by all concerned with thls irnportant development.

The author of this paper, a clvi.l englneer, ie a reaearch officer wlth the Housing Sectlon. Hls speclal concern since jolnlng the Divislon in lg5? has been with lnnovationa in the housing field, in which prefabricatlon now plays a slgnificant role.

Ottawa

March 1964 Robert F. Legget,D l r e c t o r .

ACKNOWI,EDGEMENTS

The broad study of the problems and potentlalg of prefabrr-cated houslng in Canada was made possible by the excellent co-operatlon extended by prefabrlcatore. Vlslts and dlscuseione wlth many ftrma in Ganada, and some in the unlted states and other countrles, provided much valuable lnforrnation. The author partlcularly wishes to thank the following flrms r

Alberta Trailer Ltd., Calgary Arctlc Unlts Ltd,, Toronto

Campeau Constructlon Ltd., Ottawa Canadian Gar Co. Ltd., Montreal Colonial Homes Ltd., Toronto

Eastern W'oodworkers Ltd.l New Glasgow Engineered Bulldlngs Ltd., Calgary

Greenall Brothers Ltd., Vancouver Halllday Go" Ltd., Burllngton

Halllday Craftsmen Ltd., Truro and Sprlnghilt N. O. Htpel Ltd. , Preston

Kent Component Hornes Ltd., Salnt John Larnlnex Products Ltd., Quebec

M and T Constructlon ttd,, Gander Metropolltan Homes Ltd.,'Wlnnipeg Minto Gonstructlon Ltd., Ottawa

Muttart Homes Ltd., Edrnonton and Toronto Natlonal Gomponent Bulldlngs Ltd., Ancaetef Nuway Buildlngs Ltd. I London

Pan-Abode Ltd., Vancouver

Portell Prefab Industrlee Ltd., Edrnonton Preclslon Prefab Products, Toronto

Quality Constructlon Co. Ltd., St. Bonlf,ace Rothwell-Perrln Ltd., Portland

M. F. Schurman Go. Ltd. , Sumrnerslde Styrene Industrles Ltd., Reglna

Sunnibllt Prefab Products Ltd., Toronto Therrnollte Plastics Ltd., Burnaby Tower Co. Ltd., Montreal

Treco Industrles Ltd., Quebec

l .

TABI,E Or. CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A GENERAL REYIEW

PROBLEN4,S AND TRENDS 3. I Flnanclng 3 . 2 L o c a l C o d e s 3 . 3 D i e t r i b u t l o n 3 . 4 L a b o u r 3 . 5 C o s t e 3 , 6 D e s i g n SHOP PRACTICE 4. L Plant Layout 4 . 2 A e e e m b l y J i g P r a c t l c e 4.3 Equlprnent INNOVATIONS

5. I Tranaportable Sectlon Syeterna and 5 . Z S t r e e e e d - S k i n S y e t e m s

5.3 Structural Sandwlch Syeteme

SUMT/ARY AND CONC LUSIONS

R.ET'ERENCES 7 7

9

l 3

1 6

zo

zz

3 0

3 1

3 3

3 6

3 9

40

43

47

5 n Moblle Homea5 t

7 . ( ii i )PREFABRIGATION IN CANADIAN HOUSING by

R. E. Platte

Prefabrlcation in Ganada today hae progressed from ite traditlonal role of supplying house packages for rural and small town areas to a place i-n the industry where it lncreaeingly affects general house construction. The factory is becoming a rnajor part of the complex

chain ttrat leads to tJxe completed houee. Its presence is simplifying the chain and rnodifying tb.e end product. Factory manufacture is changing the functions and relatlonships of the designer, rnanufacturer, labourer, aod distributor. The evolving patterne deeerve study by aLl concerned.

Leading buildere, building rnaterial manufactu.rers, and some large firms outside the building field are showing lncreasing intereet in factory house or component production. Accordingly the Divisioa of Building Research has expauded lte study of house manufacturrng to include observations on all leadlng prefabrication operations across tJxe country. The study has also involved eeveral important venturee fux the United States where conditiona are sirrrilar to present or anticipated conditions in Canada. A literature sufvey of prefabricationts erratic evolution on tJr,is contlnent since the I9ZOts proved to be a most important part of tJre study. It provided a reaeonable basie for the evaluation of the often conflictin"g irnplicatione of the present ventures and plans ia factory hous e production.

AltJrough prefabrication has made great advances, its present position in Canadian housebuilding ls still a rninor one, as is acknowledged by all concerned. Typical efforte in wood-frame prefabrication produce rrpackagesrr each of which compriee lees tJr"' half the house, and all told form only a small proportion of tJre total housing supply. These sirnple operations, however, can teach significant lessons. For example, house rnanufacturera can double the productivity of the labourer on the

z

-p o r t i o n t h e y m a n u f a c t u r e , s l r n p l y b y b r i n g i n g t h e m a n i n s i d e , s u p e r -v i s i n g h i m , a n d k e e p i n g m a t e r l a l s a n d j o b s o r g a n l z e d a n d a t h a n d . M e c h a n l z a t i o n d o e s n o t y e t p l a y a m a j o r r o l e . F u r t h e r , t h e p r e f a b r l -c a t o r l e a d s i n t h e i r n p o r t a n t b u s i n e e s o f b u i l d i n g h o u s e s i n w l n t e r . H e is also an experlenced teacher ln the slrnple uee of modular coordinatlon l n t h e d e s i g n a n d m a n u f a c t u r e o f h o u s e s .

W o o d - f r a m e p r e f a b r i c a t i o n s h o p e i n C a n a d a a r e n o t m o d e l s o f advanced technology, mechanizatlon or autornation. They are often, however, exarnples of improved efficlency of building, achieved through o r g a n l z a t l o n o f r n a t e r i a l s , m e n a n d Jobs, using shop cutting and aeeembly.

T h e b e g i n n l n g e o f t h e t r a n s l t i o n t o a b r o a d e r r o l e f o r P r e -fabrlcation in Canada are now flve to eight years old. Within that tlme m o s t l a r g e p r o j e c t b u i l d e r s l n C a n a d a h a v e s e t u p c e n t r a l p r e f a b s h o p s t h a t d u p l l c a t e t h e o p e r a t i o n s o f t h e e s t a b l l s h e d p r e f a b r i c a t o r e . T h e s e p r o j e c t b u i l d e r s a r e n o w , i n f a c t , p r o j e c t p r e f a b r i c a t o r s . T h e s e a n d o t h e r l a t g e r i n t e r e s t s a r e a b l e t o u s e a n d p r o r n o t e t h e n e w e r p r o d u c t s o f t e c h n o l o g y - a n d t o s e t u p m o r e d i r e c t l i n e s o f d i s t r i b u t i o n . S o r n e d e f i n i t i o n s r n a y b e u s e f u l . r t P r e f a b r l c a t i o n t r refers to a n y p r o c e s s t h a t t a k e s t h e b a s i c p i e c e s a n d r n a t e r i a l s o f b u l l d i n g i n t o s h o p s t o c u t a n d a s s e r n b l e t h e r n i n t o r n u c h l a r g e r c o r r r p o n e n t s , o f s i z e e l i m i t e d o n l y b y h a n d l i n g m e t h o d s . I n r e c e n t y e a r s t h e w o r d h a s n o t b e e n u s e d v e r y o f t e n l n N o r t h A m e r l c a b e c a u s e o f i t s u n f a v o u r a b l e association with ternporary wartlrne housing, but the popular alternative of rrhouse rnanufacturingrr (or usually lrhornerr manufacturing) ie vague. !rShop -rnanufactur e d I I or f rfactor y -rnanufactur e dl t ar e better terrn 6. B u t r t p r e f a b r i c a t l o n r r l s a n o l d a n d d i s t i n c t w o r d , i n t e r n a t l o n a l l y

r e c o g n i z e d a n d u s e d l n s e v e r a l l a n g u a g e s . I t i s u s e d l n t h i s r e p o r t . A t r p r e f a b r i c a t e d h o u s e r r h e r e r e f e r s o n l y t o h o u s e s w h e r e l n p r e f a b r i c a t e d c o m p o n e n t s r n a k e u p a t l e a s t t h e m a j o r p a r t o f t h e h o u s e s h e l l .

3

-Z. A GENERAL REVIEW

Prefabricatlon in Canada was not effectlvely begun until the early l940ls, although ventures in precutting garagee, cottages and s o m e h o u s e s h a v e b e e n a t t e m p t e d s i n c e t h e m l d d l e l 9 2 0 l s . E r n e r g e n c y houslng and veterans housing progranns during and irnmediately follow-lng $rorld War II encouraged many companies to try house prefabricatlon. Moet of theee firrns went out of buslness or reverted to summer cottage production by about L947" (Sumrner cottage production has remalned a large part of the prefabrication effort in Canada, accountlng probably for as rnany units as pernranent houses. Thls revlew deals only with permanent houses. ) Others among those firms have made sustalned attempts to compete lnthe postwar private house rnarket.. The aucc€ea-ful ones are now the trolderrr farnlliar names in Ganadlan prefabrlcatlon, such as Muttart Hornes, The Halllday Company, Eastern.Woodworkers, and Engineered Buildlngs Ltd.

A typical established prefabrlcator ln Canada evolved from a building rnaterlals dealer who firet began precutting cottage and garage packages. He may later have worked on wartlme barracks and sorre post-war lrternporarytr projects that are still in use, and then offered house packages for general sale to indlviduals or dealers. ' He alowly progres6ed to supplying houses for towns and rural areas, particularly to owner-builders. He later secured bullder-dealers and offered financing on the house package, but he continued to operate, and still does, primarlly in town and rural areas. In sorne areas he has been remarkably successful at thiet in many srnall towns, partlcularly in southern Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, he suppLies 60 to 90 per cent of the new house rnarket.

To these rrscattered-lotrr operations he brings many of the efficiencles of the project bullder in the citles, particularly those of rnass-buylng and rapid closlng-ln of the shell. He can often keep the cost of a rural or small town house close to the cost of a city project house, whereas the small local builder ln these areas rnay entail

4

-c o s t s o f $ 1 5 0 0 o r m o r e a b o v e p r o J e -c t h o u 6 e e . I . o r t h l s r e a s o n ' a n d also because of the convenience of a lrone-etopltmaterlals eupply and plannlng trpackagetr, the typlcal prefabrlcator in Ganada slowly built up hls market wtth tndividual owner-bullders and small builder-dealers

away from major centres.

He has faced rninor and major problerns ln doing this --especially local building codes and financlng -- but he has found this market to be remarkably steady, free frorn the severe fluctuations of project building. He rnay best be called an rropen-market prefabrlcatorrf.

There rnay be over 50 establiehed open-rnarket prefabri-cators across Canada, rnost of thern very emall, a few of the larger ones bullding 500 to ll00 houses a year. Together they produce well over 5000 houses a year, accounting for over 7% of the single family detached house supply.

The more extenslve u8e of prefabricatlon ln houslng began in the last five to eight years, as many of the larger project br.r.ilders in Canada becarne rrproject prefabrlcatorsl. These dupllcate the central shop faclllties of the long-established open-Frarket prefabrl-cators, but they rnanufacture house packagee for their own projects on developed land, selllng house and land together. The operations of the proJect prefabricators have not been thoroughly studied but they each rnay build frorn 200 to 800 houeeE a year, totalllng perhaps o v e r 5 0 0 0 h o u s e s a y e a t .

The positlon of house manufacturing in Canada then is r o u g h l y t h i s : p r e f a b r l c a t e d h o u s e s t o t a l s o r n e 1 1 , 0 0 0 h o u s e s a y e a r '

formlng about t5% of single-farnlly dwellings, This figure was probably only about 6 per cent just a few years ago. Comparisons wlth oLher countries are always interesting and rnay be used with caution to foretell the shape of things to come. Established prefabri-cators ln the U.S. supplied about 17 per cent of the single farnily h o u s e m a r k e t i n L 9 6 Z t a n d p r o j e c t b u i l d e r s a n d o t h e r s u s e d p r e f a b r l

5

-cation to form the maJor part of the house shell of apparently a further 18 per cent. In total, then, over 35 per cent of U.S. single farnlly housing is prefabricated. Sweden, wlth a populatlon of under 8 million and with much of her houslng in rnasonry and precast con-c r e t e , p r o d u con-c e s s o m e 8 0 0 0 w o o d p r e f a b s p e r y e a r ( o v e r 5 0 p e r con-c e n t of her slngle famlly dwellings) lncluding 2000 for export.

In additlon to the trrove of project builders to prefabrication, other changes have been occurring ln the past few years. The emall and medium builder, facing a buyerts market and increased cornpe-tition, has been turning more and more to the open-market prefabrl-cator for house packages and asslstance wlth financing and land

developrnent. These sporadic developments have given the eetablished prefabrlcators a foothold ln the larger towng and cities. Further, all builders now use prefabrlcated coffrponents ln their houges to an l n c r e a s l n g d e g r e e . ' W ' i n d o w a s e e m b l i e s h a v e , o f c o u r s e , b e e n

factory-made components for decadeso Even a small custorn builder, who rnay still recoil frorn the term |tprefabrr, happily uses prefab wlndows in all hls houses for the simple reason that he cannot make as good a product in the field. This aeems self evident, but it ie' only recently that low-cost houses have changed over to prefabricated cablnetry which le generally better than most made on site. It ie usually the high cost, htgh labour content ltems of the house shell that are lncreaslngly prefabricated. The use of prehung doors, and windows set lnto stub wall assemblies, is spreading slowly, whlle e n g i n e e r e d r o o f t r u s s e s h a v e b e c o m e s u r p r i e i n g l y p o p u l a r since rational testing and design criteria were evolved. Lower cost Iterrs such as blank waIl panels ln prefabricated form have been adopted to a much lesser extent by srnaller builders. By themselves, such panels offer little rnore than somewhat faster closing-in of the h o u s e .

The high-Iabour service items of the house -- plurnblng, wiring and, to a lesser extent, heatlng -- continue to escape rational

6

-prefabrication in thls country. Plumbing eepecially ls often requlred by local codes and the trades to be cut, fitted, installed a n d i n s p e c t e d o n t h e s i t e . ( T h e s e a s p e c t s a r e d l s c u s s e d i n S e c t l o n 3.2.1 Provlncial electrical authorlties will now often agree to factory lnspection of wiring jobs, thus allowlng prewired wall sections. (It ls not too long ago that codes and trades in sorne areas required electrlc ranges to be wired on the Job, paralleling the present situation in plurnbing. )

Despite the generally prosaic plcture of prefabricatlon ln Canada, sorne developments have taken place that have made North Amerlcan history of a sort. Slnce the rtall-factory housert of the transportable sectlon type ls currently rnuch dlscussed aB a means of allowing full prefabrlcatlon, it ls worth notlng that elnce 1947 Nuway Buildinge Ltd. has eupplied a steady rnarket in the London, Ontarlo, area with such unlte. More recently, the Canadlan Car Cornpany, Alberta Traller, and Klassen Constructlon successfully supplled, for the RCAf', perhape the largest proJects yet to use transportable section houses. The Tower Company Ltd., and later

other companles, have led ln the production of lightweight housee of stressed-skin plywood for the Far North, slnce about L946 (L, Zl. Muttart Homes was one of the flrst to sell house packages acrose a 3000-rnlIe sectlon of the continent. Engineered BulLdlngs Ltd. has long led in proJect prefabrication with unusual success in vertical integration of the whole buildlng procesa. Arctic Units developed one of the earller all-panellzed structural sandwlch northern houge systerns tn I957 (2). Other Canadlan flrms are well lnto promislng ploneerlng work with sandwich technlques for general housing. Sorne developmente ln prefabrlcatlon in Canada are illustrated in tr'igures I to lB.

7

-3. PROBT.TMS AND TRENDS

The rnany false starts and generally slow growth of prefabrl-cation can only be understood by revlewing the problems lnvolved. Thal the recent growth rate is not transitory is lndicated by the fact that rnost of these problems are rnoderating, while those facing site-builders are increasing. Some key problerns and the trends they have

shaped are here briefly reviewed. Thls revlew ehows the need for rnore intensive study in several areae.

3. I Flnanclng

Financlng has long been considered a rnaJor obstacle to the volume productlon and rnarketlng of prefabricated houses in North Amerlca. Interlm and final house financlng are usually the problerns, but capitalizatlon and production flnanclng are also critlcal factors in Canada.

Delays affect prefabrlcators conslderably rnore than site-builders, and delays are an accepted part of normal house financing. rn scattered-lot or owner-lot bullding, whlch has been the basls of rnost Canadlan prefabrlcation, a customer may well favour a prefabrl-cator lf he finds he can thereby obtaln the house he d,esiree in a

relatively short time. Thts selling point rnay be largely ellrninated by the flnancing delay. Even after the custorner securee his loan approval he may wait a rnonth to slx weeks before hls mortgage can be arranged. The custorner ls faced wlth a long wait ln any case and his lncentive for turning to the prefabrlcator is greatly reduced.

After the rnortgage is arranged and constructlon beglns, further derays of a day or two can occur at the several stages requiring

inspection under NHA financing, although these can be reduced if the builder gives a schedule of desirable inspection dates well in advance. Thls, of course, is difficult to do in scattered-lot bullding.

Conventlonal flnancing under Life Insurance and Trust Gornpanies can greatly reduce the inltial and construction delays,

8

-but this entails aome extra costs for the customer. Nevertheless, many open-rnarket prefabricators rely malnly on conventional

financlng because of tirne advantages, and also because the National Houslng Act appralsed value for establlshing the loan arnount ls often kept conslderably lower ln rural areas than ln cities. Although the loan-to-appraisal ratio for conventlonal loans (i.

"., outslde the NHA) ls set by law at only 60 to 67 per cent, the Trust and Llfe Insur-ance Cornpanies often reduce thls effect by allowing generoue appraisale in areas merlting their confldence. Established prefabrlcators have often found these companiee to be quite liberal in recognizing the valtdlty and stabllity of demand for houses in rural areas and small towns.

Prefabricators tle up far more money in their initial deliveryto the site than do other builders, since they lnclude more labour content and ship as much of the rnaterials and equlprnent as possible with the package to minirnize t}:e nurhber of trips. For this reason they are ln greater need of interlrn fJ.nanclng gchernes. Thls ie especially true where the owner does his own building and progresses slowly to the stages that allow constructlon payrnents. The situatlon ie aggravated by the fact that many or rnost Ganadian prefabricators have dlfflculty maintalning worklng capital and givlng short-terrn credlt to the dealer, unless imrnediate rrpackagerr payrnent is forth-coming.

T h e s e n e e d s c o m p r l s e o n e o f t h e s t r o n g e r r e a s o n s f o r t h e eetting up of a long-needed body in Canada - a countrywide house prefabrication association. In the flrst instance, an lndustry association can make representatlons for better utilization of the present flnancing schernes. One exernplary firrn has worked in this way to gain faater processing and hlgher rural valuations and loan Ievels under the National Housing Act. Secondly, perhaps a case for changes in the present national schernes can be well docurnented.

9

-For example, representations for lnterim financing have evidently never been made. Sweden allows immediate financing and the United States lnterlrn financlng, on delivery of the package, through both national and prlvate arrangements.

Alternatively, prefabricatore have often favoured the eetting up of subsidiary acceptance corporations to handle interlm and sometirnes final financing. National Hornes in the (J.S., (the l a r g e s t p r e f a b r i c a t o r , r n a k l n g s o m e Z O I 0 0 0 h o u s e s p e r y e a r )

credlted rnuch of lts early succesa to its acceptance corPoration (3). The few Canadian cornpanles uelng euch schernes find them costly, with their finance cornpany personnel invariably outnurnbering their factory management and sales staff. Agaln, a strong industry

associatlon could help by creating or associating wlth an acceptance corporation that would serve all members. Sorne building materials rnanufacturers wlll noW back such ventures. One growing

licen€e€-group of prefabrlcators in Canada is now arranging such flnancing with evident success"

3 . 2 L o c a l C o d e s

No one can know in what direction the house would have developed if it had not faced local administration of local codes at every stage in its evolution. No other ltrnaJor appliancelr hae faced such local restrictions. On the one hand the popular building Press has overrated the cost-raising effect of local codes on conventlonal wood-frarne or rrrasonry houslng. On the other hand, ln the few

countries using codes that are nationally adrninistered, and ln areag such as the Mldwest States where reglonal rnodel codes have been in effect, comparatively advanced prefabricated housing now dorni-nates (3). This progress has been rnade desplte the facts that these code reforms go back little more than a decade, and that geographlcal and other restrictive factors stltl operate. Other factors favourable t o p r e f a b r i c a t i o n a r e a l s o p r e s e n t , h o w e v e r , l n t h o s e s a m e a r e a s

l 0

-notably financing and labour advantages.

Discusslons wlth prefabrlcatore across Canada, who rnugt conslder local codee ln all planning and operations, lead to the

following observatlons. First, rnost local codes do not seriously cornplicate constructlon or raise the costs of conventional elte-built houses, nor of the typical partialJ.y prefabrlcated houses. second, they do restrict any atternpts to lncorporate further ltshop contentrl in prefabs in rnany areas. 3'lnally, local codeg and thelr

admlnlstrations are a rnajor block to aray systems that include innovatlone ln structure or rnaterials, especially where they rnust be rrrarketed throughout large areas to achleve econornlc volurne.

Exarnples can usefully lllustrate these points. Cornpanies have been prohlbited frorn prewlring thelr wall panels, and thus were unable to close and finish the panels, because of requirements of

on-site lnspectlon or, sometirnes, of installation by local electrlclans. More cornrnonlyr preaaaernblles of the rnost sirnple and rationar types of plurnblng are prohibited on the sarne grounds. One cornpany very slowly obtained acceptance for its prefinlshed unlts in several townships and has enjoyed stable rnarkets in these for sorne eixteen years' but ls still prohlbited frorn expanding its sales into adjacent townshipg because of lts ehop plurnbing. At least three larger pre-fabricators were produclng rnore advanced and prefinlshed houses in the late 1940ts and early l950ts than they do now. Local codes and labour influences forced thelr return to the typlcal furcornplete prefab as deecribed ln Section 3.4, with its very low shop content.

Several atternpts to rnarket separate prefabricated eervlce cores (kitchen-bath-utillty services) have been abandoned prirnarlly

becauee of restrictlons and differenceE in local codes, Sorne cornpanies have had gtressed skin plywood systems (section 5.2) prohibited

l l

-history of sound stressed skln panel design and performance that goes back at least to 1937 (4). Both early and recent atternpts to use

structural sandwlch panel partltlons and walls (Section 5, 3) were blocked by rlgid interpretation of local codes as typlfied by the repeated questlon rrWhere are the studs?rl

Concerning restrictions on rrrore routlne advancee, roof trusges are prohibited in several areas, or rnust be uneconornlcally p l a c e d a t l 6 i n . o . c o r r t b e c a u s e r o o f f r a m i n g i s a l w a y s o n 16 in. o.c. ll Prefabrlcated chirnneys are often reJected. A few Canadian

communities stlll prohtbit any prefabricated houses of any typ". A lnore quantitative survey, still incornplete, shows that the sltuation In the unlted States is even more severe than in Ganadal some 26 pet cent of the munlcipalities soirreyud ban prefabs outrlght I L4 per cent ban roof trusses; I9 per cent ban prefab flues; and 40 per cent ban any plumbing preassemblies (5). A11 these prefabricated components are at least equal in performance to their older counterparts.

Solutions to the lmpasee created by some local codes rnay not be possible under our congtltutlonal delegation of responsibilites -federal, provinclal and rnunlclpal (6). rrsolutionsil to date have been negatlve ones - prefabricators have generally sought markets in rural areaa and/or have kept thelr packages incornplete. All agree, how-ever, that the sltuatlon is lmproving slowty but the rate. of improvement can be accelerated if all approaches are properly used.

Probably the biggest lnfluence prolnotlng the local acceptance of advances ln house constructlon has been the Central Mortgage and Houeing Gorporatlon, the admlnistrator of the National Housing Act. In lte function of evaluating new corrrponents or systerns for acceptance for NHA financing, c. M. H. c. conelders technlcal adequacy prirnarliy, and accepts even completely prefinished systerns on the basis of factory inspection. The municipality or township has the final

authority, but some comrnunities consider C. M. FI. G. acceptance as evidence of engineerlng adequacy, and they rnay set aside their local

I Z

-s p e c i f i c a t i o n c o d e -s f o r -s u c h -s y -s t e m -s .

The National Bullding Code is slowly becorning a signiflcant agent in easlng local restrictions against prefabricated cornponents and systerns, o1d and new. Thls code which is an advisory docurnent is produced by an associate cornmittee rnade up of leading individuals frorn private industry, lndustry associations, research groups and others, under sponsorship of the National Research Gouncil. It has been adopted in whole or in part by cornrnunities including over half the countryrs populatlon, although many of these still retain the older vereions. It is widely recognized as a leadlng rnodel code. The Code is a perforrn€rnce code concerning such rnatters as loads, deflectlons, and therrnal requlrernente, and also includes specifications for

farniliar constructions and rnaterlals. It allows for alternative

systerns where engineering design or test shows their adequacy, at the discretlon of the local butldtng authority. Desplte this, prefabrl-cators operating in areas that have adopted the NBC contend that it has not yet resulted in greatly increased receptivlty to new cornponents or systerns. The local inspector rnay ignore the alternative systern clauses (or they may be deleted on adopting the code) because of hls adrnitted inability to evaluate design or test reports, Some rnodel codes in the U. s. A. include a service that evaluates and llsts new systerns as an ald to local authorities, but no such rnechanlsrn yet exlsts ln Canada,

, Facjng such an irnpasse, the prefabricator or dealer tnay . appeal to the local council, or preferably, to an Appeals Board if one exists. He rnay then appeal to the courte, (in the u.s. he often did, and nearly always won) but the delays involved rnake this quite

irnpractlcal. Hls appeal to local councils rnay be helped iJ he first obtains irnpartial engineering inforrnation on the question. This rnay be sought frorn consurtante or frorn university or research groups

1 3

-q u e s t i o n s , h e m a y a r r a n g e f o r f a c t o r y i n s p e c t i o n ance through some provlncial power authoritles. rules on plumblng matters, but the rise of actlve authorities such as the Ontario Water Reeources eventually fill thls need.

3. 3 Dlstrlbution

and apply for accept-No such authority provincial

Cornmlssion may

Geography sets lts own lirnits on the shape and scale of pre-fabrlcation ln Ganada. The countryls 4000-rnile rlbbon of population hae only a few dense clusters suitable for high volurne house factories. Even lf rnetropolltan rnarkets are rnuch better served by prefabricators than ls now the case, tt ie difficult to envisage that more than a few factoriee can achleve arurual volumee of even 5000 housee, for a decade or more. Thls dispersal of production mean6 that proper organlzation of marketlng and transpoptatlon arrangemente is critically lrnportant.

Transportatlon costs usually llmit a factoryle selllng radi.ue t o 2 0 0 t o 3 5 0 m l l e s . A n o r m a l t r a n s p o r t c h a r g e i s $1.00 per rnile for panellzed houses where one truck can carry one house. The

prefabrl-cator usually runs his own trucks. He cannot readily arrange return loads for eeveral reasons. The traller is often of speclal design and ls usually loaded in reverse sequence to minlrnize handling on site. It etays at the slte untll shell erection is complete (the drlver often acte as agent, and eupervieor of shell erectlon). The tractor unlt rnay aleo be required to stay at the job, particularly i.f it includes its own boorn crane to unload and erect the heavy components. Thus for every day on the road, Loaded, the rlg rnay sit on slte for a day and then return unloaded.

The prefabrlcator can reduce over-a11 transportation costs by locatlng near major materials sources and rnajor markets; by reduclng bulk (by panellzing, nesting, lnstalling lnsulation, etc. so a6 to rrehip less airrr); by lncorporatlng rrrore prefinishlng and servlcee to increase the value of the shlpped package; and by seeking co-operative

1 4

-arrangements to allow return loads. Equally lmportant, the prefabri-cator (or, better, his national a6sociation when it exists) should study the practicability of slrnplifying rates for the |tpiggybackrr rnethod of

shipping trailere by rall. Thls method should particularly suit pre-fabrication and extend its economic range quite markedly.

If buildersl costs were better clarified it would be apparent that transportation costs in close-by areas are lower for prefabri-cators than for emall bullders" A rnaterials supplier makes about 30 separate tripe per house for srnaller slte-builders. If the supplier becornes a prefabricator he rnakes one to four trips to the job" In the former case the bullder paid for the transportation and handling when he paid for hie materials, whether or not the charge was separately noted.

Field handling and assernbly will ultimately be considered as merely a part of rrdistributionrr ln the prefabrlcation industry. At present there are two views: the one contends that any prefab rnust be simple and ruggeC, adapted to manual handling by typical builders rrworking in the mudrr; the other that the shop package must be as corn-plete and prefinished as possible, with the field equipment and crews carefully chosen to sult it. Only the latter approach rnay allow the full potential of prefabrication to be realized. To this end, Canadian

prefabrlcators might well consider the use of truck-rnounted hydraulic boorn cranes (rnounted on the transport truck itself, between tractor and trailer). Theee cranes allow the use of prefinished panels, and also facilitate the erection of the two-storey row housing and apartrnent units that are becoming a large part of our housing supply (Section 3.61.

The complexlty of the prefabrlcatorls otgarrlzation for

distribution and erection varies from the extrernes of selling rnaterials to owner-builders, to cornplete vertical integration of all functions. The arrangernents are rnost important not only because of geography, but also because of the extreme fluctuations in the new house market.

1 5

-The most rudimentary structure for distribution involvea only the prefabricator and his customer, the latter normally having a building lot before he contacts the prefabricator. A surprising advantage in this is that this scattered-lot market is quite eteady through the years. It is very seasonal, howeveri allowing little winter production, and it is obviously lirnited in potential volurne. The buyef rnay build hirnself (or contract locally), but the prefabrl-cator often does the she[ erection. Thls approach involves the pre-fabrlcator in more hourg and problerns in sales and advisory eervicee than do other methods. At least two of the older rnanufacturers still

rely on this arrangement but both are rapidly turning to the following s c h e m e e .

The rnore advanced steps in distribution are not alwaye distlnct but all result in a wider baee for sales, and in diseociation of prefabricator from individual buyer. The prefabricator rnay firet

set up sales agents or dealers who arrange contacte and sales, ind advise on financlng, but they leave the erection to the buyer or the prefabricator. The latter often finds it difficult to use home-based

field crews for erection and finishing, because of the distances involved, and the fluctuation of building activity. He may then acquire rrdealer-builders" who fill this function. Surprisingly, he hae not usually turned to established builders for this, in Canada at least. He has

generally preferred to set up and train young builders as his dealer-b u l l d e r s , o r t o u s e r e a l - e s t a t e p e o p l e a s d e a l e r - c o n t r a c t o r s . M o r e recently, however, established builders in towns and citiee are them-selves approaching prefabricators to invite such arrangernents, as competition increases and attitudes change.

These arrangements allow high potential volurne over wide areas but often do little to establish year-round production, since building is still prirnarily on scattered lots for lndividual buyers who think in terrns of surnmer building. Large projects therefore attract

1 6

-t h e p r e f a b r i c a -t o r . H e h i m s e l f b e c o m e s a l a n d d e v e l o p e r o r p r o j e c t -p r e f a b r i c a t o r , o r h e t i e s i n w i t h e s t a b l i s h e d d e v e l o p e r s o r p r o j e c t b u i l d e r s ( o r , m o r e o f t e n , a p r o j e c t b u i l d e r b e c o m e s his own project-prefabricator, as noted earlier). This allows fulI winter production and increases total volume, and also atows planning at least one or two years ahead; all of this greatry helps the factory process. on the other hand project building can be particularly prone to

fluctuations in housing demand and rnoney supply, and by itself rnay not provide a stable base for factory housing.

Two points lndicate the better trends in distribution-organization for prefabricators. First, the most successful pre-fabricators in Canada rely heavily on their own land developrnent and project building (or achieve thle through tie-ins with others) but they also cultivate a substanti aL rnatket through scattered dealer -buildere. Second, several large organizations from outside the buildlng field which are now consldering venturee into factory housing, have been

discussing artangements with large land developers, and often with large rnaterials producers interested in such developrnent.

3.4 Labour

The status of the labourer directly affects the progrese of prefabrication, and prefabrication in turn affects the organization, tralning, and use of the labourer.

w h e r e w a g e s r i s e s o d o e s t h e u s e o f p r e f a b r i c a t i o n , a s i s demonstrated by severar areas such as the Mid-west united States and Sweden. These are areas of organized labour. In additlon to their generally high wage6 a most favourable factor for prefabrication is the full recognition given to an indoor -outdoor differential. rn much of the Mid-west area, for exarnple, the house rnanufacturerrs factory wages average perhaps $z.lo per hour near the larger citiesl field construction wages may average about $3" 50 per hour. with both shops and field fully unionlzed, the urltone have chosen to

L 7

-recognize a sharp dlfferential, allowing shop wages to be sorne 40 per cent under field wageso This recognizes better working conditions and the continulty of ernployrnent that is normally attendant upon shop

labour, and also its lower demands for e>cperience, skill, and reepon-sibllity.

]i[ith few exceptiong, house building labour in the shops or in the field is not unionized in Ganada, and the few cases of shop union-lzation have rarely resulted in high wages since the competing non-union field wages are low. The few instances of full labour organization in ehop and fleld do follow the pattern of higher wages in the field than in the shop.

Irr the factory the older tradee become blurred or cease to exist, and these changes will and rnust increase as new materiale and methods complement simple wood-frarne construction. In anticipation of cornlng unlonlzation, the prefabricators rnight well study and draw attention to the fact that the traditional distinction between rnlllwork trades does not work well in house manufacturing shops. The men rnust accept a reasonable arnount of overlapping on Jobs, with the lines between trades changed and often erased. Thls is partlcularly true in the srnaller shops whlch will. remain a Large part of the scene.

An excellent example was set by a recently eetabllshed prefabrication venture in the Unlted States. Before setting up the

factory the organlzers initiated discussions with a major rnillworking union and gained full agreement that all men be open to aI[ reasonable jobs, irrespective of traditional trade boundaries. The labour

position of that organization through its first several yearB has been rnost favourable.

The eseence of prefabrlcation ie productivity. Many countrles are recognlzing that the increasing population carinot be housed by tradltional fteld methods (?). J. Yan Ettinger, of Hollandrs Bouwcentrum, estirnates that ln the next 40 yeare world housing

1 8

-production must be raised from the present l0 million dwellings per year to about 36 rnillion per year (8). In the fac.e of the rising demand, a d e f i c i t o f s o m e 2 , 0 0 0 , 0 0 0 s k i l l e d w o r k e r e i s e > p e c t e d i n t h e U n i t e d States by 1970. The rising and reasonable tendency of labour to favour factory over the fleld, and to avoid lengthy apprenticeships for field skills, fits well with the recognition by rnost developed countries that only factory methods can rneet the housing demand. The use of pre-fabrlcatlon wlll incredse sharply, and because of their more extreme needs, the transition in rnany countries rnay be far more rapid than in Canada.

The productlvlty gaine attalnable through prefabricatlon result frorn two distinct factors:

(l) Sheltered, organLzed working conditions, and l?l Mechanlzation.

The flrst factor has been the prlrnary one in wood-frarne prefabrlcation in Canada. Surprisingly, taking the rnan lnto a shop, bringing

materials and directions to him, and allowing hirn to work in one area on proper tables, in itself can double his productivity as compared with fteld labour. Considering the cornponents of a typical wood-frame

prefab package ln Canada in all lts simplicity (precut floor joists and subfloor, prefabricated partitions and wall panels with sheathing or wall board on one face onlyr prehung doors and windowb usually ln place in the panels, and prefabricated roof trusses and gable endsi trim and finish rnaterlals packaged and partially precut) the total shop tlrne for this portion of the operation may be about 75 manhours.

About I00 mar*rour6 are used ln the field to aseemble these cornponents and piecee into the sirnple house shell, thus totalling some 175 rnan-hours. This can be compared with project-built houses of the early

I950rs when little or no precutting or prefabrication was used,. with the erecting of the same shell then taking about 350 rrranhours.

_ 1 9 _

'When

Canadlan plants progress toward more cornplete packages, adding wiring, sorne plurnbing assemblles, interior and exterior claddlng and sheathing, and rnoet of the cablnetry, the shop tirne approaches 200 rnanhours, with the productivity still depending primarily on the Itsheltered worklr factor rather than mech.anlzation. The full effects of rnechanization are not easy to establish, but they are indicated by the fact that this rnore complete package is rnade by a leading United Statee prefabricator in about I00 manhours.

Figure l9 reveals some simple, important facts about wood-frame prefabrication, facts that are not often appreciated. First,

even the sirnple rropen paneltr etage of prefabrication (c), with ite low shop content, can rernarkably increage productivity and control in house construction. Second, and equally important, the point is soon reached with wood frarne where further stages of prefabrication with increased lrshop contenttr do not automatically reduce total labour,

It must be emphasized that I'igure 19 does not ehow a fixed relationship between shop content and total labour, but merely showe the labour figures reported by a limited number of companies in

Canada. A company could achleve, ady, 40 per cent shop content and yet use total labour above the graph peak. Another might have lees than 20 per cent shop content and yet achieve total labour per house below the graph minimu.m. Organlzation and mechanizatlon in shop and field are as important as shop content itself.

Stagee (a), (b), (c), (d), and (f) of Flgure 19 are derived from figures given by some fifteen companies in Ganada fitting in or near these stages. Breakdowns and descriptions of operations were often not clearly stated, and the ranges shown are only approximate. Nevertheless the generar shape and poeition of the curve should be valid. stage (c) is roughly derived from two particularly advanced u. s. companies, with figures modified since their houses are on s l a b s . T h l s c l o s e d - p a n e l - a n d - c o r e s t a g e h a s n o t b e e n w e l l r n e a s u r e d

2 4

-but apparently can be well below others in total labour content - even below the trtransportable sectionlr housee of alrnost 100 per cent shop content (t). The irnplications of this are dlscussed in Section 5. I.

As is usual practlce in rneasuring house labour, the labour contents shown ln Figure 19 ref.er only to ilerection and finishinglt or rrshop and field assernblyrr, not to total rnanufacture. Obvlously the manufacture of lurnber and other rnaterials le not included, nor the factory labour ln such items as furnace, appliances, tubs, einks and electrical fixtures. Window manufacture ie also ornitted. Thue the actual lrshop contentrr ln the total rnanufacture of any house is much higher than shown. The graph shows only the builderts and prefabri-catorrs norrnal contribution. It applles to the houee proper, including floor but omitting basement, foundation, and gradlng (which would add 100 to 150 manhours). A11 cabinetry and finishing are lncluded. It ie a s s u r n e d t h a t n o r n a s o n r y o r o t h e r r l w e t t r p r o c e s s e s a r e u e e d e x c e p t painting (i. e., drpriall, prefab chimneys and wood or other manu-f a c t u r e d s i d l n g s a r e u s e d ) .

3 . 5 C o s t s

Constructldn cost is not yet the maJor factor influencing the larger housebullders toward prefabrication. Turnover, control of coets, tirne and quallty, and winter building advantages are factors of at least slrnllar importance. The cost posltion in wood-frarne housing is not accurately known or fixed but can be stated for the general case. The open-market prefabrlcator erectlng houses on scattered lots in rural and town areas can sell well below the usual b u i l d e r s l n s u c h a r e a s o T h e l a r g e r p r o j e c t - p r e f a b r l c a t o r s r n a y e e l l

slightly below rnost on-site project builders in their cornpeting areas near clties. The cornpetitlve rnargin is purportedly 10 to z0 per cent with the former, and 5 to l0 per cent (sornetirnea rnore) with the latter. As house building wages rise toward industrial wage revels the cost advantages of prefabrication wilr increase.

zr

-A common misconception is that greatly increased overhead costs are incurred in house prefabrication, cancelllng much of the savings from increased productivity. Although not well docurnented, It can be stated as an approxlrnation that the troverhead contentil in the cornplete chain of house production does not vary greatly with changes of rnethod, but is merely distributed dlfferently. rt can be at its highest when it is thought to be at ite lowegt - when the rrone man builderrrls the final part of the production chain. He may think that his overhead ls rronry the telephonel, but in paying for materials he payg eeveral overheads: taxes, accountlng, and plant runnlng and rental (ln warehouslng) of local retallers and reglonal distributors. These must stock great variety over long periode for the many emall buildere who want a llttle at a tLrne. In the conetruction itself he may uee llttle that can be called |tplantrt, but he pays trplant rentalr for the house and site while building, either in interest or in the loss of sale or rental income during the long period of construction. His

advantage is that he is not responsible for much of thls overhead - he incurs few rtfixed chargeetr - and so can readily e>qpand or shrinkto suit the market.

Overheads are difficult to ellrninate. Large builders and Iarge prefabricators comrnonly cut their material coste by 25 per cent (compared with srnall builders) by buying in carload lote directly from the manufacturer, but they then assutne a portion of the diEtributor-retailer overhead, in warehousing and handling. (They often then form their own r€tail subsidiary to proflt on rnaterial salee to others, but the resulting additional overheads are not a part of their houee

production costs. ) Operative builders avoid direct adminlstrative over _ head by contractlng rnuch of their site building to subcontractors, but the overhead is there: each subcontractor has his office, shop, and s t o r a g e c o s t s , w h i c h b e c o r n e p a r t of his price.

z z

-The prefabrlcator asEumee further direct overhead in plant running and rental, but thls for the most part merely dlsplaces other overheads. To allow shell prefabrlcatlon he erctends the ware-house and preparatlon areas ueed by larger builders, thus reducing time and overhead on slte for that portion. He may extend further to allow production of windows, doors, cablnetry, ducts, plumbing and even sorne ltbulldlng rn,aterlalstr, and in thls he incurs further over-heads - that are present in any case, normally under otherel

d l r e c t i o n ( 1 0 ) .

Whether bullt in factory or on site, wood-frarne construction costs form the best yardstick to evaluate the potential of new systerrrs. Thts yardstlck ls remarkably dlfflcult to equal. To cornpete against a cornpletely flnlehed wood-frame house, a ltnorrnal rnaintenancelr wall system (requiring repaintlng every few years) should cost about 80 cents to $1.00 per Bqrare foot; finished. The complete roof and ceiling rnay coet about 20 per cent more, and partltions rnay cost as llttle ae l/3 to t/Z ae much ae the gi.ven exterlor waII cogts. The trend to frrnainte-nance-freelr exterlor walls allows an eagier rnark for newer eysterne to compete with - about $t. 1O to $I.60 per square foot. The lower figure ie representatlve of the coet of wood frame with the plastic-coated rnetals, asbestos boards and wood products that are lncreasingly popular as house oidlnge; the higher flgure ls representative of wood-frarne with brlck veneer, at least in low-wage areas. Unless new eysterns offer significant advantages ln uE e over the durable and technically sound wood-frarne constructlons, they should be able to

corne close to these costs in volume productlon if they are to succeed. 3 . 6 D e s l g n

The terrn ttprefabricated houserr euggests a

shop-fabricated house. In practice, however, many prefabricated houees have little rnore than exterior walls built in the shop and these

2 3

-finlshed walls, even with windows, comprtse only some I0 per cent of the house construction. House rtbreakthroughsrr are always being promised on the basis of a new wall system alone. If the walls were made of air, the savings in cost would only be that I0 per cent.

Signiflcant savings can only be gained by prefabrlcating the cornpleted, p r e f i n i s h e d s h e l l a n d c a b i n e t r y a n d a t l e a s t 6 o r n e s e r v i c e 6 . N e v e r t h e -less the rnost tirne-honoured and sirnple method of classifying prefabri-cated house systems is by the approach to the exterior wall - to the eye the wall is the rnajor part of the house.

Durlng over forty yeare of prefabrication history, almost every innovator considering prefabricatlon has thought first of srnall, repeated rrrnodularrr wall panels, but usually turned to larger wall sections. The advantages of the fotrnet atet

(I) Standard panels of relatlvely small dlrnenslon can be cornbined in rnany ways to allow flexible design. ( Z ) T h e y c a n b e p r o d u c e d t o s t o c k s i n c e t h e i r u s e i s n o t

dependent on the buyere choice of a partlcular house ( F i g u r e t I ) "

(3) They are readily handled on site by one or two rnen, without the use of special equipment.

But the dlsadvantages are also clear and are usually crltical. Small panels require rnany joints which run right through the wall or

enclosure elernent tf the panels are reasonably prefinished (and no cladding is installed at the site). It ls difficult to rnake aLarge footage of joint for the house enclosure at a reasonable coet to meet the requirernents of protection against all elements, whlle giving pleasing appearance with protected, durable edges. One large

producer of. 4- by 8-ft panel houses found he could allow only 70 cents for each 8-ft vertical Joint, to rernaln cornpetitive with simple wood f r a m e .

2 4

-For the above and other reasonei , nearly every prefabrication venture has adopted the frroom wallrt or rrwhole wallrr approach, and thia choice is being repeated every year. The larger panels allow these advantage s:

(t) Joints are minirnLzed, occurring only at Large windows, d o o r s , o r c o r n e r s - n o m o r e j o i n t s a r e n e c e s s a r y t h a n with traditional construction.

( Z l G o s t s a r e r e d u c e d . W t t h n e a r l y e v e r y p r o d u c t i o n p r o c e s s it is cheaper to rnake something Latge than to rnake it small; every start and stop and every edging is costly. (3) The large panels are rxrore suited to the provieion of

cornplete interior and exterior finioh and the incorporation of wiring.

On the negatlve gide, larger panels are rnore easily damaged tf the prefabricator atternpts to handle them by hand on the job,

particularly if they are prefinished as ls desirable. This again brings up a baeic point in the approach to prefabricatlon. Should the prefab package be sirnple and rough, designed to fit the typical bullder wlth hls usual man-handling rnethods, or should lt include the optlrnurn amount of ehop finishing and be recognized as needlng a distlnct approach to site aseembly, including trained crews and proper equiprnent? Ae noted in Section 3. 4, only the latter approach seerns to hold real potentlal. The use of truck-rnounted boorn cranes should be e>cplored more fully ae Canadlan firrns progress toward far rnore complete prefinishing of their large panel systerns. One company found that such equiprnent reduced darnage to prefiniehed sectione by 80 to 90 per cent - while doubling the speed of erectlon.

Although large panel systems do not allow the flexibility of design wlth standard parts that srnall panels can allow, rnany have shown that rnore than adequate variety can be produced without decreasing the production efficieacy. The eeveral prefabrlcators

2 5

-winning Design Awards in Canada have used both srnall and Iarge panel systems. Many of the latter have evolved to a very

effective use of an ttopenlngs-and-fillersrr appf oach. Appropriate doors and windows are chosen from a family of standard |topeningll panels of wall height, and located wherever desired around the h o u s e p e r i r n e t e r . S o l i d w a l l t t f i l l e r l r p a n e l s a r e t h e n m a d e u p o f a

standard construction varying only in length, the lengths

pre-determined by the location of the rtopeningrr panele. In this way the relatively high-cost cornponents (windows, doors, patio doors,

certain trfeatureil panels) are of standard dimensions and rnanufacture, whlle the lower-cost solid wall sections can readily be rnade to

varying lengths. While simplifying design and manufacture, this approach has incidentally promoted a pleasing coherence of design i n s o r n e l a r g e p r o j e c t s .

Most prefabrlcators ln Canada ernploy rnodular coordi-nation in the deslgn and manufacture of houses. The minor rnodule of 4 in. and a major module of 16, 24, or 48 in. are used, with elements usually centred (in thickness) on the grid lines. A leader in rnodular u6age ls National Cornponent Butldings Ltd., an

independent Canadlan offshoot of the pioneering Precision-Built group of the IJ. S. A" Uslng roorn-slze walls and partitions with small standard components for intersections, doors and windows, N. C. B. ernploy rnodular planning and ingeniously rnarked jig tables to allow rapid yet flexible layout and production. This also allowe a rninirnurn of waste in frarne or sheet rnaterials" These modest but significant advantages are the main ones gained by the u e e o f l l r n o d u l a r l l i n a l r c l o s e d s y s t e m l l , L . € . , where componente are sized and detailed for use with thernselves and other known components, to forrn a rtsystemlr building. Most prefabrlcators p r o d u c e c l o s e d s y s t e r n s .

2 6

-Proponents of trrnodularrr contend that its maln advantages can only be obtalned in lropen systernslr, where one manls cornponents can fit with othersl cornponents to form anyonels bullding. rrOpen systernsrr are thus related to traditional building with rrbricks and sticksrr, but the terrn Itsystemll denotes larger parts, usually pre-fabricated, fixed together in predetermined positions. The wide-spread use of one adopted discipline of rrodular coordination could reduce the nurnber of "sizes of building components, resulting in rnuch higher production of each eize, reducing both manufacturing and distribution costs.

The feasibiltty of rropen systernrt production in building depends on resolving rnany questionsz siz'es, types and shapes of jointe, tolerances, devlations, posltion of the elernent or joint with respect to the grtd line (i. e. , doee a stud rnove off the line to allow for a wlndow, or vice versa), and allowance for the thickness of the components at corners and intersectione. In wood-frame housingr the recent and wldely publicized trUnicomrr system of modular

co-ordlnation attempts to allow open systern productlon of rnany standard parts. Although it does not resolve aI[ these proble:rrs, it becomee quite complex in trying to do eo, and rnost u6ers will quickly

eirnplify Unicorn by creating in effect their own closed systern. High-cost items such as windows, doors, and cabinetry, and parts such ae trusses, wlth large tolerances in erection, are produced for open sale, but systems of prefabrlcatlon in North America and Europe will

probably continue to evolve as lrclosed syetemslr for sorne tirne to corne. Other shell components can equal the value of exterior walls in their shop content and as proportlons of the house costs. The trend to low slope roofs and rrcathedrailr cellings allows the elirnination of ceilinge aB 6eparate structures, so that slngle panels can act as

corlbined roof-celling componente. These can rneet the basic crlterlon for prefabricationt they can be compact enoqgh, and include enough

2 7

-materlal, labour, and finishing, to be worth rnaking in the shop.

T h e y m a y b e o f s i m p l e f r a m e o r s t r e s s e d s k i n c o n s t r u c t l o n s p a n n i n g frorn exterior walls to a cenfre wall or a centre bearn, to allow open

planntng. The sloplng ceilings compllcate the partition construction

whereas flat roofs allow the use of roof -celling panels without this complication.

Panel partitions can be satlsfactory in rnuch sllrnrner

thicknesses than norrnil frarne partitions, if sound transrnission through

the partition and noise and vibration frorn the closing of doors is

con-trolled. The tightnesa of the panel joints may be as important, or rnore

lmportant, than the ma.ss of the panel ltself in controlling sound

trans-rnission. To control door closlng shock, it is best to let the door

assernbly be relatively independent of the partition by provlding rigid

framing frorn floor to ceiling.

As rnultlple-farnily housing becornes an increasing part of our

housing supply, prefabricators are adapting their systems to include such

units. European cornpanies prefabricate high-rise rnultiple housing as

a matter of course with their heavy concrete systernen The lightweight

systerns evolved for slngle-family houses in North Amerlca can.readily

form at least three-storey rnultiple housing, despite the added irnplications

of fire and sound as compared with the slngle-family house. Row housee

o f c r o s s - w a l l c o n s t r u c t i o n c a n , o f c o u r 6 e , u s e p r e c a s t p a n e l o r block

party walls to satisfy fire and sound questions. Frarne, stresaed-skln

or sandwich panels can then span between the party walls, as walls,

floors and roofs. These rlghtweight panels can also satisfy party wall

reguirements. In wood frarne, staggered studs with certain gypsum faces

form adequate party walls, easlly prefabricated. Stressed skin panels

can be faced with gypsum, and also sand filled if necessary, but the Pure sandwich panel cannot yet be econornically modified to rneet party wall requirernents"

2 8

-The profitable extension of prefabrication to rnultlple housing witl depend on special handling equiprnent, such as truck-rnounted cranes or light tower cranes; the typical rnethode

developed for frame houses will not sufflce.

There are few technlcal problerns in prefabricated house deslgn that are not shared by all housing. Deslgners should be farnillar with the fundamentals of building for the Canadian clirnate. Publications are available as introductions to these fundamentals. Technical questions raised by new rnateriale are discussed with such rnaterials in Section 5.

The one key elernent of particular importance to pre-fabricatlon is the through-wall joint. All building involves jolnts betwee.n rnaterials, but these usually extend through only one or two layers at any one point (except at wlndows, doors, etc. ). Ae the prefab becornes rrore completely prefinished, the Joint extende frorn lnside to outslde between the enclosure components. No layers are added to cover up. An adequate joint involves lnoney and tirne, and this fact alone forces the trend to large panels with a minimum of Joints. Many small-panel prefabricated houses have suffered frorn wind and rain infiltration through jolnts of faulty design or fit, or dried-out caulking. Gonslderation of the following points can allow slrnple through-wall joints of reasonabtre cost and adequate performance!

(I) Provide a joint seal near the lnside (warrn) face of the enclosure, allow the outer portion to be

relatively loose, and incorporate a widened charnber in the outer portion. This detail tends to stop

lnterior water vapour at a warm area (above the dew point), and allows any vapour passing the seal to escape freely, thus preventing condensatlon in the joint. Further, the detall follows the rrraln scf,eenrr