Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Internal Report (National Research Council of Canada. Institute for Research in

Construction), 1998-10-01

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC : https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=aef0e7e6-3be2-4deb-9831-415e00aacafe https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=aef0e7e6-3be2-4deb-9831-415e00aacafe

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/20331371

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Study of the Occupant's Behavior during the Ambleside Fire in Ottawa

on January 31, 1997

S F R

T H I National Research Conseil national

R 4 2 7

191

Council Canada de recherche= CanadaBLDG COP. :?

no. 771

Octobel

Study of the Occupant's

Behavior during the Ambleside

Fire in Ottawa on January

31,

11997

Guylene Proulx, Michael

J.Ouellette and Patrice Leroux

Kim R. Bailey, Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario

Internal Report No. 771

Date of issue: October 1998

t e r n a l r e p o r t ( I n s t i t u t e f ANALYSE CISTT/ICIST NRC/CNRC I R C Ref 5 e r Rec:eivwd an: 11-04-98 I n t e r n a l r e p o r t .

Study of the Occupants' Behaviour

During The Ambleside Fire

in Ottawa, Ontario on 31 January 1997

by Guylene Proulx, Ph.D., Michael

J.Ouellette. B.S.E., Patrice Leroux

National Research Council of Canada

and

Kim R. Bailey, P.Eng.

Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario

Internal Report No. 771

.

. .. . . . . .. . , -, , ,-.

..

;I _ & I' &; ?:Z-

..,. . .. .."

-

STUDY OF THE OCCUPANTS' BEHAVIOUR

DURING THE AMBLESIDE FlRE

IN OTTAWA, ONTARIO, ON

31

JANUARY

1997

Guylene Proulx, Ph.D., Michael J. Ouellette, B.S.E., Patrice Leroux, National Research Council of Canada

and

Kim R. Bailey, P. Eng., Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario

TABLE OF CONTENTS

... LIST OF FIGURES

...

III... LIST OF TABLES ... III

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ... ... iv

1.0

INTRODUCTION...

1

2.0

STUDY OBJECTIVES... I

3.0

THE FlRE INCIDENT...

2

3.1

The Building...

5. .

3.2

Voice Commun~cat~on System...

7

4.0

RESEARCH STRATEGY...

8

4.1

The Questionnaire...

85.0

QUESTIONNAIRES ANALYSIS...

95.1

Questionnaires Returned...

95.2

Interviews...

10

6.0

OCCUPANT PROFILE...

I0

6.1

Length of Stay...

1

7.0

FlRE SAFETY KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCE ...I 1

7.1

False Alarms...

12

8.0

ACTIONS PRIOR TO EVACUATION... I2

8.1

Fire Incident...

13

8.2

Activity at Time of Initial Awareness...

I3

8.3

Attempt to Obtain Additional Information...

I4

9.0

ATTEMPTED EVACUATION... 15

9.1

Groups Who Separated... 16

. .

9.2

Condition in the Corridor...

17

9.3

Return to Apartment or Seek Refuge... 18

9.4

Use of Elevator and Stair ...20

10.0

REMAINED IN BUILDING...

21

10.1

Stay. Return or Take Refuge in an Apartment... 22

...

10.2

Reasons for Staying in Building22

...10.3

Number of Occupants in Apartments22

...

10.4

Protective Actions while in Apartment22

...

10.5

Use of Balcony and Windows23

...11.0

INFORMATION ON FIRE SAFETY23

12.0

COMPARISON OF OCCUPANTS UP TO AND OVER65

YEARS OLD... 23

13.0

DISCUSSION... 25

13.1

Evacuation Procedure...

25

. .

...

13.2

Occupants' Age and Characteristics26

...

13.3

Impact of this Fire Experience on Occupants' Attitude27

. . ....

13.4

Questionnaire Limrtations27

14.0

CONCLUSIONS...

28

...

14.1

Some Negative Factors28

...

14.2

Factors that Positively Impacted on the Fire Incident29

15.0

RECOMMENDATIONS...

30

16.0

REFERENCES...

31

APPENDIX A Fire Emergency Procedure as Found in the Tenant Binder APPENDIX B The Questionnaire

iii

LlST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Movement of the Two Occupants in the Apartment of Fire Origin ... 4

Figure 2: Typical Floor Plan of the Ambleside Building ... 5

Figure 3: Picture of the East Side of the Ambleside Building

...

6...

Figure 4: Time to Start Evacuation 15 Figure 5: Floor at Which Smoke was Encountered in Stairwells...

20LlST OF TABLES Table 1: Age Distribution of Respondents

...

I 0 Table 2 Respondents with Limitations...

11Table 3: Length of Stay in the Building

...

I I Table 4: Source of Information on Fire Safety...

12...

Table 5: Initial Awareness of the Emergency 13 Table 6: Activity at Time of Initial Fire Awareness...

14. . . Table 7: Cue ln~t~atlng Evacuation

...

16Table 8: Smoke Colour

...

17. . . . Table 9: Distance of Vls~bll~ty

...

18Table 10: Number of Floors Travelled before Returning Home

...

19Table 11: Number of Floors Travelled before Seeking Refuge

...

19Table 12: Reasons for Staying in Apartment

...

22Table 13: Number of Occupants per Apartment

...

22...

Table 14: Cue Initiating Evacuation for Occupants Up to and Over 65 Years Old 24... Table 15: Different Behaviour for Respondents Up to and Over 65 Years Old 24

STUDY OF THE OCCUPANTS' BEHAVIOUR

DURING THE AMBLESIDE FIRE

IN OTTAWA, ONTARIO, ON 31 JANUARY 1997

Guylene Proulx, Ph.D., Michael J. Ouellette, B.S.E., Patrice Leroux, National Research Council of Canada

and

Kim R. Bailey, P. Eng., Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On 31 January 1997, a fire occurred in a 25-storey highrise apartment building located in Ottawa, Ontario. The building contains 296 condominium-apartments owned mainly by senior citizens. The fire started in an apartment on the 6th floor and rapidly burned through the apartment entrance door to migrate into the corridor. One of the two elderly occupants of the apartment of fire origin called 911 at 16:34. The local fire department arrived on location at 16:39 and extinguished the fire within 10 minutes.

Upon their arrival, the fire department asked for an announcement to be made on the building voice communication system instructing residents to evacuate the buildicg. This message was clear for 95% of the occupants including occupants with hearing

limitations. Following this message most occupants attempted to evacuate. A small proportion of occupants who judged themselves physically unable to evacuate decided to stay in their apartments and "protect in place". All the occupants located above the fire floor mentioned encountering smoke conditions during their evacuation. Just over half (54%) of the occupants who attempted to evacuate managed to escape. Among the 53 occupants who were unsuccessful in their attempt to evacuate, 55% returned to their apartment and 45% had to seek refuge in someone else's apartment.

Two of the evacuees had to be treated for smoke inhalation. Following the evacuation, two seniors had heart attacks, one of whom died 10 days after the fire. The two occupants of the apartment of fire origin were taken to the hospital. The woman suffered from smoke inhalation and severe burns. She succumbed to her injuries 2%

months later on 15 April 1997.

The fire incident resulted in many interesting findings regarding the occupants' behaviour. The impact of the voice communication system, the occupants' age and characteristics, as well as the occupants' attitudes toward evacuation, as a result of the fire, are noteworthy and are discussed in this report.

The National Research Council of Canada in collaboration with the Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario decided to study the occupants' behaviour during this fire to document this event. A questionnaire, sent to every unit, was used to gather data. The results show that occupants had different rationales to explain their decisions to protect in place or to attempt to evacuate. Implications for codes, training and education are discussed.

ETUDE DU COMPORTEMENT DES OCCUPANTS PENDANT

L'INCENDIE DU 1081 AMBLESIDE A OTTAWA, ONTARIO

LE 31 JANVIER 1997

par

Guylene Proulx, Ph.D., Michael J. Ouellette, B.Sc., Patrice Leroux, Conseil national de recherches du Canada et

Kim R. Bailsy, Ing. P., Bureau du commissaire aux incendies de I'Ontario

Le 31 janvier 1997 avait lieu un incendie dans un immeuble de grande hauteur de 25 etages a Ottawa en Ontario. Le batiment contenait 296 appartements en

copropriete occupes principalement par des personnes agees. L'incendie a debute dans un appartement du 6ieme etage pour se propager rapidement dans le corridor principal de I'immeuble en brclant de part en part la porte d'entree du logement. Une des deux personnes agees de I'appartement oh I'incendie a debute, telephonait au 91 1 a 16:34 pour les aviser du fsu. Les pompiers sont arrives rapidement sur place a 16:39, le feu etait circonscrit puis eteint en moins de 10 minutes.

A leur arrivCe sur les lieux, les pornpiers demandaient qu'on diffuse un message sur le reseau de communication phonique pour demander aux occupants d'evacuer le batiment. Ce message transmis par le reseau de communication etait clair pour 95 % des occupants, incluant les occupants ayant un handicap auditif. Suite a ce message, la majorite des occupants tentaient d'evacuer le batiment. Quelques residents ont

toutefois juges qu'ils etaient incapable physiquement d'evacuer le batiment et decidaient de rester dans leurs appartements et de prendre des mesures de protection. Tous les occupants situes au-dessus de I'etage de I'incendie ont rencontre de la fumee pendant leur tentative d'evacua:ion. Un peu plus de la moitie des occupants (54 %) qui ont tente d'evacuer reussissaient a sortir sans aide. Parmi les 53 occupants qui n'ont pas reussi a evacuer, 55 % song retournes a leur appartement et 45 % ont dO demander un refuge dans I'appartement d'un voisin.

Deux des personnes qui ont tente d'evacuer ont dO etre traite pour inhalation de fumee. Suite a I'evacuation, deux residents ages ont subit des crises cardiaques ; I'un d'eux est decede 10 jours apres I'incendie. Les deux residents, un homme et sa femme, de I'appartement ou I'incendie a debute ont ete amene a I'hBpital. La dame a ete

hospitalise aux soins intensifs a cause de brclures et d'inhalation de fumee. Deux mois apres I'incendie, le 15 avril 1997, elle decedait des suites de cet incendie.

Le comportement des occupants pendant cet incendie est particulierement interessant a etudier. _'impact de I'usage du systeme de communication phonique, Sage et les caraderistiques des occupants, ainsi que I'attitude des occupants face

I'evacuation suite 5 cet incendie, sont des elements majeurs discutes dans ce rapport. Le Conseil national de recherches en collaboration avec le Bureau du

comrnissaire aux ircendies de I'Ontario ont decide d'etudier le comportement des occupants pendant cet incendie afin de documenter cet evenement tragique. Un

questionnaire a ete distribue a tous les residents pour obtenir les donnees de I'etude. Les resultats dernontrent les differents raisonnernents des occupants selon qu'ils decidaient de rester dans leur apparternent et de prendre des rnesures protectrices ou de tenter d'evacuer le batirnent. Les implications de ces resultats pour la legislation et la formation sont discutees.

STUDY OF THE OCCUPANTS BEHAVIOUR

DURING THE AMBLESIDE FIRE

IN OTTAWA, ONTARIO, ON 31 JANUARY

1997

Guylene Proulx, Ph.D., Michael J. Ouellette, B.S.E., Patrice Leroux, National Research Council of Canada

and

Kim R. Bailey, P. Eng., Oftice of the Fire Marshal of Ontario

1.0

INTRODUCTION

The study of occupants' behaviour during a fire incident is one of the best ways to learn about the impact of human factors on the circumstances and outcomes of a fire. The victims of a fire are prime witnesses; they can easily describe their perception of the event, their interpretation and their reactions during the fire. The information gathered during a human behaviour study leads to an understanding of the conditions in the building at the time of the fire. The information also helps to explain the behaviours of different occupants during the event and the rationale behind their actions.

On the day of the fire at 1081 Ambleside Drive, Ottawa, an agreement was established between the Office of the Fire Marshal of Ontario (OFM) and researchers at the National Fire Laboratory of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) to collaborate on an effort to study the occupants' behaviour during this fire. Both groups agreed on the importance of gathering human behaviour data from this fire as quickly as possible.

Fire statistics for the Province of Ontario showed that between 1989 and 1993, a total of 32 fatalities occurred during fires in residential buildings higher than five storeys in building height. Among the fatalities, thirteen were over 65 years old, which

represents 41% of the fatalities.

The results of this study will be used to develop recommendations to improve fire safety in highrise apartment buildings. This work will help to define better evacuation procedures, training and education programs and changes in the regulation and codes of practice. Dissemination of the results will be accomplished through scientific

publications, conferences, magazines and presentations to specific groups. These results will also be used to verify the NRC computer model FiRECAMm [I], which is used to assess occupants' risk to life from fires.

2.0

STUDY OBJECTIVES

A human behaviour study is a unique way to gather essential information about a traumatic situation such as a fire. One advantage of this kind of study is that it is

results will facilitate the work of investigators and researchers who need to understand the overall building and occupant performance during this fire to develop

recommendations to prevent a similar situation from being repeated.

The general objective of this study was to gather information on the actual behaviour of the occupants who were in the building at the time of the fire incident. I: is very important to identify what went wrong during this fire as well as what went right. The occupants are the best individuals to explain the danger they were exposed to, their

understanding of the situation, and their actions during the fire.

To meet this objective, the following information on occupant perception and behaviour was obtained for this study:

the method by which occupants became aware that something unusual was happening in the building

once aware of a fire in the building, the first actions undertaken by the occupants

the time at which the occupants left their apartment unit

smoke and lighting conditions the occupants encountered during their evacuation

the impact that the information provided over the voice

communication system had on the occupants' decision to evacuate or remain in their apartment

the conditions that forced occupants to discontinue attempts of evacuation through exit stairwells and seek refuge in an apartment smoke conditions on the different floors of the building

the actions occupants undertook to ensure their safety

Variables such as gender, age and physical limitations are identified in the study as parameters that can play a role during a building evacuation.

3.0

THE

FIRE INCIDENTOn January 31, 1997, in the late afternoon, a fire started in Apartment 602 on the 6th floor at 1081 Ambleside Drive in Ottawa, Ontario. At the time of the fire, the two occupants, a husband and wife, aged 80 and 82 years old were in the apartment. As the description of the chronology of actions by the occupants may have changed through many reiterations, the description given here may vary slightly from some other reports on the fire.

The husband was in the living room when he heard the apartment smoke alarm activate. His wife was in the kitchen preparing supper. He went to investigate and discovered smoke pouring out from the closet in the entrance foyer. He slid open the closet door to discover extensive burning. He called to his wife to warn her, but she may not have heard because of her poor hearing. He ran to the master bedroom to use the phone to call 91 1. In the bedroom there was smoke so he opened the patio door to ventilate the room. After calling 91 1 (his call was received at 16:34) he attempted to

come back into the hall to reach his wife but the smoke was too dense and hot, forcing him to retreat to the bedroom balcony. The woman, who was using a walker to assist her movement, moved from the kitchen to the living room, where she collapsed. The occupants' movement can be followed in Figure 1

The fire spread from the closet to the foyer area of the apartment and burned through the closed tubular-core wood apartment entrance door and spread into the 6th floor main corridor. The fire directly impinged on the entrance door of Apartment 603 directly opposite the apartment of fire origin. The fire spread extended to approximately 17 m down the corridor before being extinguished by the fire department.

Smoke damage to the 6th floor corridor was extensive, with some units close to Apartment 602 also receiving some smoke damage. There was no significant smoke damage to other areas of the building.

According to Environment Canada, on 31 January 1997, the temperature at 16:OO was -8.6"C with ElNE winds of 13 kmlh and at 17:OO the temperature had risen slightly to -8.4"C with ElNE winds of 11 kmlh. Sunset was at 17:lO. At the time of the fire, heavy snowflakes were falling for a total accumulation of 8.2 cm of snow on the day.

The Ottawa Fire Department received a 91 1 notification of the fire at 16:34 and arrived at the scene at 16:39 with an aerial vehicle and a pumper truck initially.

Additional back-up units were dispatched after the fire was confirmed by the first units on site. The initial 91 1 phone call came from the occupants of the apartment of fire origin, followed shortly after by a 91 1 call from the neighbour across the hall in Apartment 603.

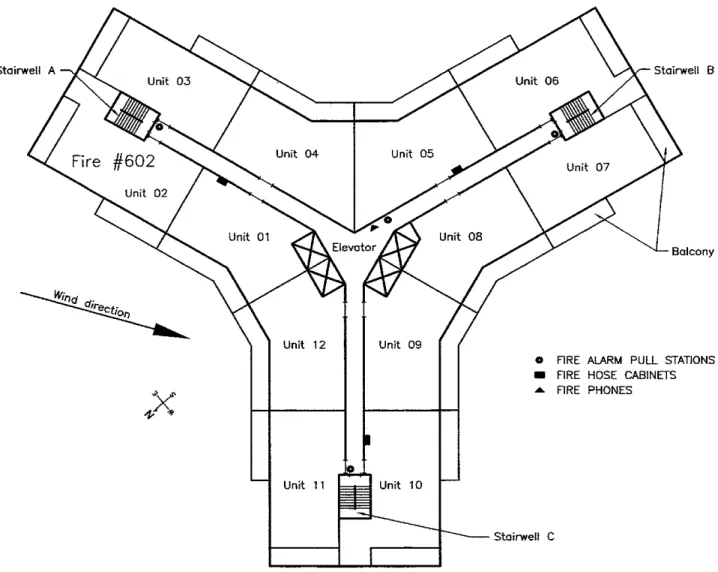

The initial fire department units accessed the 6th floor from Stairwell A, see Figure 2. They encountered flames and smoke in the main corridor and noticed flames coming through the doorway of Apartment 602. The fire department attached a hose to the 5th floor hose standpipe and extended it up Stairwell A to the 6th floor. Fire

suppression operations extinguished the fire in the corridor and in Apartment 602 at 16:46. Both occupants of Apartment 602 were found by the fire department and evacuated. The occupants were taken to the ground floor and life support procedures started on the woman. The remainder of the 6th floor was searched by the fire

department and three remaining occupants were found and evacuated. Smoke ventilation and clean-up operations were then started.

The two occupants of the apartment of fire origin were taken to the hospital. The woman suffered from smoke inhalation and severe burns. She succumbed to her injuries 2% months later on 15 April 1997. Two other evacuees had to be treated for smoke inhalation and two seniors had heart attacks, one of whom died 10 days after the fire.

3.1 The Building

The 1081 Ambleside Drive building was built in 1973. The building, constructed

of reinforced concrete, comprises 25 storeys plus 3 basement levels. Figure 2 shows

the "Y" shape floor plan of the building with the four elevators in the central core. Each

wing of the building has 4 apartments, for a total of 12 apartments per floor except for the

first floor, which has 8 apartments and the building lobby. Each of the three wings

terminate in exit stairwells, designated A, B and C.

0 FIRE ALARM P U U STATIONS

I FIRE HOSE CABINETS

A FIRE PHONES

Figure 2: Typical Floor Plan of the Ambleside Building

In total, the building has 296 luxury condominium-apartments, each having one or two exterior balconies, as seen in Figure 3. The three basement levels contain

6

indoor pool, a laundry room, storage rooms, service and mechanical rooms as well as

three parking levels.

Figure

3:Photograph of the East Side of the Ambleside Building

Each floor is provided with a

2h fire-rated floor separation. The corridors and

stairwell separations are constructed using gypsum wallboard on steel studs. Walls

separating apartments are constructed using concrete or gypsum wallboard on steel

studs. Stairwell doors are a

1%h rated hollow metal type in hollow metal frames.

Apartment entrance doors are

oftubular-core wood construction, approximately

45mm

thick, in hollow metal frames. The apartment and stairwell doors are provided

withself-

closing devices and latching hardware.

A

hose standpipe

isprovided

atthe mid-point of each wing to feed hose cabinets

on each floor. Water-type fire extinguishers are provided in each hose cabinet All

below-grade floors are sprinklered as well as the garbage mom and refuse chute.

A

hydrant is located within

90m of the main building entrance.

The building has a single-stage fire alarm system equipped

withheat detectors in

the service rooms, storage moms and refuse chute access moms on each floor.

Stairwells are provided with both heat and smoke detectors. Manual pull stations are located at all exit doors, including each door accessing the three exit stairwells, and at the elevator lobby on each floor. The fire alarm system is audible through speakers that are provided throughout all floor areas and in each apartment. These speakers are also used as part of the building voice communication system. The fire alarm is silenced during voice communication use. Fire alarm activation shuts down the building's recirculating ventilation system and prevents elevator operation except by use of over- ride and manual recall switches. Battery-powered smoke alarms are provided in each apartment and are maintained by apartment occupants.

A fire alarm audibility survey was conducted by the Office of the Fire Marshal after the fire to sample alarm levels in the 6"'floor suites. The minimum audibility level within the bedrooms of the apartments with the bedroom door open was 55 dBA, with the bedroom door closed, 46 dBA and by the suite alarm speaker, 87 dBA. Ambient sound levels were approximately 35 dBA.

An emergency generator provides power to emergency systems in the building, which includes two elevators, fire alarm system, voice communication system, two standpipe booster pumps and emergency lighting.

The building had an approved fire safety plan, with a copy of the fire emergency procedures supplied to each tenant as part of their Tenant's Binder (see Appendix A). The building was in compliance with the 1992 Retrofit Section 9.6 of the Ontario Fire Code.

3.2 Voice Communication System

The building was equipped with a voice communication system with speakers throughout the building and in each apartment. During the summer of 1996, a new alarm system had been installed that was tested monthly with first a message provided through the voice communication system followed by the test of the alarm.

The fire safety plan stated that upon hearing the fire alarm and after checking that the fire was not in their unit, occupants were expected to await further instructions to be provided through the voice communication system. If the evacuation was judged

necessary by the fire department, instructions regarding which floor should evacuate and which stairwell should be used would be given through the voice communication system (see Appendix A).

It is the Resident Manager's assignment to operate the voice communication system. In his absence his assistant who also resides in the building would take over the responsibility to operate it.

On the afternoon of the fire, the Resident Manager recalls giving out 4 or

5 messages over the voice communication system. Only the first message was given before the arrival of the fire department. The order to evacuate was given by the fire

department after an assessment of the situation. The exact wording of each message was not recorded but here is the general content of each message:

1. There is a fire on the 6th floor. The fire department is on its way. 2. All occupants should evacuate using stairwells B and C.

3. Occupants should not evacuate through stairwell A.

4. Occupants who have not started to evacuate should remain in their units

4.0 RESEARCH STRATEGY

In order to gather information on human behaviour during the Ambleside fire, two data-gathering methods were used. First, face-to-face interviews were carried out with the occupants of the fire floor, the 6th floor, and the floor above, to obtain detailed accounts of the event by the occupants closest to the fire. Second, all the other building occupants received a questionnaire at their door.

This two-fold research strategy offers the advantage of reaching all the occupants in a short period of time, while providing data that is easy to code and analyze. The combination of the detailed account of the closest witnesses and an extensive quantity of information from all the other occupants through the questionnaire gives a complete overview of the event. This strategy is cost-effective in terms of time and staff required for interviews, data analysis and documentation of the results.

4.1 The Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by the Ofice of the Fire Marshal (OFM) in late 1996 to obtain data from occupants of residential building fires in the province of Ontario. Input from an NRC survey [2], an OFM survey used for the 2 Forest Laneway, North York fire in 1995, and other OFM sources, was used to develop this questionnaire.

Only one questionnaire was distributed to each apartment. Consequently, a completed questionnaire may describe the behaviour of one or more occupants of an apartment. In this report, the number of respondents to a question corresponds to 1 person per questionnaire returned where an answer was provided. It is, however, not known if all the occupants in the apartment would have answered each question the same.

The questionnaire comprises 53 questions with a number of sub-questions presented under six headings (see Appendix B). The questions are general enough that the questionnaire can be used without any change in almost any multi-unit residential fire.

he

use of this questionnaire will allow the researchers at the OFM to gather a large bank of information on human behaviour during highrise residential fires. Three main styles of questions are used131.

A majority of questions are close-ended questions such as "Did you use the exit stairs? Yes D No U". Some are close-ended questions with anumber of options to choose from. A few other questions are open-ended, allowing the respondent to describe something in a few words, such as in the question "Describe briefly what you typically do when you hear the fire alarm". Usually the respondent has

only one line to answer the open-ended questions. This design offers sufficient flexibility for the respondent while keeping later coding and scoring of the answers simple.

5.0 QUESTIONNAIRES ANALYSIS

The returned questionnaires were coded, scored and input into a data sheet. Data was entered into a spreadsheet and checked by two persons to ensure accuracy. A coding manual was developed.

The data was analyzed using the software packages

SPSS

for Windows version 6.01 and Excel version 5.0.SPSS

is a very powerful statistical software package for social sciences, which can perform a multitude of statistical analysis [4]. Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize the results and look at frequency distributions, percentages and means.The results presented specify the "percent" or the "valid percent". The percent refers to the overall percentage of people in a category with respect to the total number of returned questionnaires. The valid percent, however, represents the percentage of the total number of people who have answered a specific question excluding all the missing answers. The valid percent is usually the most meaningful result to consider in studies using a questionnaire to gather information. In this report, the percentages presented are usually the valid percent based on the total number of respondents who answered a specific question.

5.1 Questionnaires Returned

The 1081 Ambleside Drive building has a total of 296 apartments. These are condominium apartments and in most cases the owners are living in the apartment. At the time and had registered their departure with the building superintendent so

questionnaires were not delivered to these apartments. Replies to the questionnaire could then be expected from 265 units, excluding the unit of fire origin.

A total of 213 questionnaires were returned. This represents a return rate of 80% which is excellent for this kind of study, where a return rate of 30 to 50% is usual [2, 5, 61.

This exceptional return rate ensures the internal validity of the research. Consequently, the study results can be generalized with confidence to the entire building population for the human behaviour of occupants in the building during this fire.

The questionnaires were distributed to 265 units, during the week following the fire. Most questionnaires were returned within two weeks. Of the 213 questionnaires returned, 76 or 36% mentioned that they were not at home during the fire. A total of 137 questionnaires from occupants who were at home during the fire were used in the final analysis. This represents a 72% return rate from persons in the building (or who did not indicate their absence) at the time of the fire. This large number of completed

5.2 Interviews

A total of 12 face-to-face interviews were carried out during the week following the fire. The occupants who agreed to be interviewed were at home during the fire. Five of them resided on the 6th floor, the fire floor, and 4 were from the 7th floor. These interviews provided detailed descriptions of the fire development and the smoke

condition from the closest witnesses to the fire. Three other occupants from other floors asked to be interviewed instead of filling out the questionnaire.

After the interview, a questionnaire was filled out for each of the interviewed occupants according to the information provided. These questionnaires were analyzed with all the other questionnaires.

6.0 OCCUPANT PROFILE

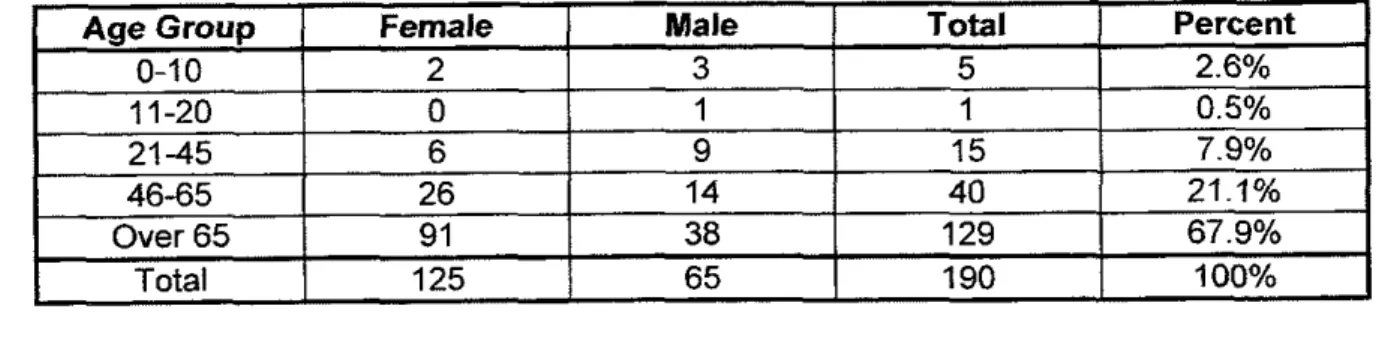

The first section of the questionnaire considered the occupant profile. There were few children or teenagers living in the building or visiting the building at the time of the fire. Over two-thirds of the respondents were over the age of 65 years old, which is representative of the overall population of the building.

The questionnaires returned represent 190 occupants who were in the building at the time of the fire, 125 or 66% were females and 65 or 34% were males. The age distribution of the respondents is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1: Age Distribution

of

RespondentsOf the 133 respondents to Question A4 (see Appendix B), 85 or 64% were alone in their apartment at the time of the fire. Out of this group, 63 or 74% were occupants over 65 years old, of which 54 or 86% were women and 9 or 14% were men. Also, 22 respondents up to 65 years old were alone at the time of the fire, of which 13 or 59% were women and 9 or 41 % were men.

A total of 43 respondents or 23% reported having limitations, as presented in Table 2. This is higher than the general Canadian population where, according to Statistics Canada, 15% of the people having perceptual, physical or intellectual

limitations are living in private households [7, 81. This high proportion of occupants with limitations is probably due to the fact that 68% of the respondents were over 65 years

old. A total of 37 females and 6 males reported a limitation. There were no pregnant women among the respondents.

TABLE 2: Respondents with Limitations

6.1 Length of Stay Limitation Hearing

Mobllity

Vision Other Multiple TotalA majority of the respondents had been living at the Ambleside building for more than 10 years at the time they answered the questionnaire, as shown

in

Table 3.TABLE 3: Length of Stay in the Building Female 6 17

-

-3 6 5 37 Male 1 1 0 3 1 67.0 FIRE SAFETY KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCE

Fire safety knowledge varied from one individual to the other. The questionnaire provided 8 options for sources of information: "Building Management", "School", "Fire Department", "Office", "Brochure", "Lecture", "Public Service Announcement" and "Other". Respondents could choose one or all sources that were applicable. Table 4

sums up the sources of fire safety information identified by the respondents.

Valid Percent 7.4% 17.6% 17.6% 57.4% 100% Number of Yea=

Less than 1 year 1 to 5 years 5 to 10 years Over 10 years Total Frequency 10 24 24 78 136

TABLE 4: Source of Information on Fire Safety

A total of 107 respondents (88%) to Question E4 indicated being aware of the evacuation procedure for the Ambleside building. This procedure was described by 91 respondents as "upon hearing the fire alarm, wait for instructions coming through the voice communication system and follow insfrucfions".

Sixteen or 12% of the 130 respondents to Question E7 (see Appendix B) had previously experienced a fire. Of these. 2 respondents had been in the war in Europe and 1 had been a volunteer firefighter. Another 12 respondents had been in a residential fire, among which 7 mentioned experiencing a fire that occurred at the Ambleside

building in the 1980s. Apparently that fire was quickly contained and no evacuation was necessary.

7.1 False Alarms

The fire alarm bells were activated regularly in the building due to false alarms or fire alarm testing. Only two people out of 112 respondents were not aware of such alarms. During the last year, 41 respondents or 37% mentioned that they were aware of 12 incidences of false or test alarms or more, while 23 or 21% said the alarm had been activated frequently.

According to the building management, a new alarm system had been implemented during the summer of 1996. At the time of installation the new alarm system was tested often. In the 5 months prior to the fire, the fire alarm was regular!y tested each month.

8.0 ACTIONS PRIOR TO EVACUATION

This section contains a detailed analysis of the initial actions of the respondents prior to their attempt to evacuate. It examines the circumstances of the initial awareness stage and the information available to the occupants.

8.1 Fire Incident

To identify how occupants were made aware of the fire incident, respondents could choose one or several of seven options provided in Question B1 (see Appendix B). The majority of the building occupants were first made aware that something unusual was happening by the sound of the fire alarm, as presented in Table 5. Out of

135 respondents to this question, 53 or 39% mentioned the fire alarm alone while a total of 94 or 70% included the fire alarm as one of the sources notifying them of the

emergency. The second means by which occupants indicated they were most often alerted was by the voice communication system. A total of 57 or 42% indicated the voice commun~cation system along with at least one other source and 18 or 13% identified the voice communication system only. A number of occupants mentioned other multiple sources including fire trucks (6%) or noise in corridor (4%).

Interestingly, the 10 respondents who mentioned having hearing limitations, 9 females and 1 male, were all notified of the emergency by hearing the fire alarm. Among them, 8 said the voice communication was clear and it was the cue to start the evacuation for 6 of them.

TABLE 5: Initial Awareness of the Emergency

8.2 Activity at Time of Initial Awareness

Table 6 shows the activities of the respondents at the time they became aware of the fire. Most of the 133 respondents to this question (B2) were awake preparing

supper, watching television or doing some leisure activities such as reading, knitting or listening to music.

14

TABLE 6: Activity a t Time o f initial Fire Awareness

8.3 Attempt t o Obtain Additional Information

When occupants first became aware of the emergency, 39 or 30% out of 132 respondents to Question 83 (see Appendix B), attempted to obtain more

information. Of these, 22 contacted neighbours, 3 dialled 91 1 and 14 did not mention what they did to obtain additional information. A majority of respondents, 93 or 70%, did

not attempt to obtain additional information, as they were waiting to receive instructions from the voice communication system.

Valid Percent 29.3% 26.3% 18.0% 3.0% 2.3% 21.1% 100% Activity Watching TV Leisure Cooking Cleaning Sleeping Other Total

Information was provided through the voice communication system. The

messages were clear for 124 or 95% of the 130 respondents to this question

(B4).

The 116 respondents to Question 85, "What information were you given ..." could choose one or more of five options. A total of 87 respondents recalled hearing the information "There is a fire emergency", 80 heard "Leave immediately", 77 heard "The fire is on floor x", 38 heard "Further information will be provided" and 11 heard "Stay in your apartment". It should be noted that although it appears that fewer respondents heard the voicecommunication messages as the fire progressed this was not the result of a deterioration of the system but was probably the result of people having already evacuated the

building or standing outside on their balconies. Frequency 39 35 24 4 3 28 133

A total of 86 or 75% out of 114 respondents, indicated that they were not told how to determine if it was safe to leave and 89 or 83% out of 107 respondents, were not told

how to protect in place.

The large majority of the 123 respondents, 110 or 89% followed instmctions provided through the voice communication system. The instructions provided over the voice communication system were judged useful for 70 or 64% of the 109 respondents to Question B7.

9.0 ATTEMPTED EVACUATION

After going through each questionnaire, it is clear that a majority of the respondents attempted to evacuate the building. In fact, 114 or 83% of the

137 respondents attempted to evacuate their apartment that afternoon. As presented in Figure 4, 76 respondents indicated a time at which they started their evacuation. Of these. the largest group of respondents (26 or 34%) indicated waiting about 5 minutes before starting to evacuate after having been alerteb to the fire. o f the respondents, 24 specified starting their evacuation when instructed over the voice communication system, which was approximately 5 to 8 minutes after the fire alarm sounded. This time could be determined as this message was issued after the fire department arrival, on an order from the platoon fire chief.

Minutes

FIGURE 4: Time to Start Evacuation

Among the 117 respondents who identified the cue that prompted their movement, 97 respondents identified voice communication messages in addition to some other cue. Only 5 respondents indicated that they started to evacuate after hearing only the fire alarm. Respondents could choose one or all 8 options to answer

16

TABLE 7: Cue Initiating Evacuation

Before starting to evacuate, 89 or 82% out of 110 respondents took the time to get dressed, putting on a coat, mitts and boots, and 25 or 23% picked up belongings such as purse, wallet or keys. The majority of the 116 respondents to Question C7,

112 or 97%. took the time to ensure that their main apartment door was closed upon leaving. It is not known if this action was to prevent the smoke from entering their apartment, to prevent burglars from entering or if they check door closure out of habit. All apartment entrance doors were equipped with self-closing devices to automatically shut the doors.

Amongst the 43 respondents who mentioned having a limitation or disability, a majority of them (31 or 72%) attempted to evacuate the building while 12 or 28% did not make such an attempt. Of the six respondents with limitations located below the fire floor, all attempted to evacuate and 4 of them managed to escape the building. Above the fire floor, a total of 25 people with limitations attempted to evacuate and only 5 were successful. These successful evacuees were all located between the 6th and 15th floors of the building. Two were females with mobility limitations, 1 female had hearing

limitations and 1 man and 1 woman had other limitations.

9.1 Groups Who Separated

Of the 48 cases of people who indicated that they were with others when they were made aware of the fire, all but one evacuated as a group. During evacuation, 7 respondents mentioned being separated from their companion. In 5 cases, it was in stairwells where groups were separated due to others entering the stairwell. In 2 cases, adults lost children who went ahead of them. Some older residents indicated that staying in a group became difficult when they were overtaken by faster evacuees in the

stairwells. One female specified she became separated from her group "because of the crowd in the stairwell and the heavy black smoke encountered around the 8th floor". She also lost consciousness in the stairwell and was rescued by the Resident Manager, his assistant and other residents.

Some 25 or 23% of the 107 respondents to Question C9 (see Appendix B)

indicated that someone took a leading role during the evacuation giving instructions A few occupants received assistance from the fire department while evacuating.

9.2 Conditions i n the Corridor

According to 11 1 or 95% out of 11 7 respondents, the lights were on in their corridor. Among the 6 respondents who said that the lights were not on, 2 were located on the fire floor and 1 was right above the apartment of fire origin. Two groups from the 19th floor saw grey or black smoke in the corridor and indicated that the lights were off. Also, a mobility impaired person who saw black smoke on the 20th floor indicated that the lights were off. Lack of lighting on the floors may have been due to fire damage or more likely by smoke obscuration in the corridor.

Responses to Question C11 "Did you see EXIT signs?" should be analyzed with care. A total of 99, or 88% out of 112 respondents, reported seeing exit signs, while 13 or 12% said they did not see exit signs. It is possible that some respondents mentioned seeing exit signs only because they knew that exit signs were there even though they may not have noticed them specifically that day. Inversely, some

respondents may say that they did not see exit signs because they did not consciously notice any exit sign even though they may have seen them. Among the 6 respondents who said the lights were off in their corridor, 2 said they did not see exit signs, 2 said they saw exit signs and 2 did not answer that question.

The majority of respondents who attempted to evacuate encountered smoke during their evacuation movement. In fact, 102 or 85% out of 120 respondents to Question C12 (see Appendix B) indicated there was some smoke in the corridor. All of the 18 respondents who did not encounter smoke in the corridor during their evacuation were located below the tire floor.

Among the 25 respondents to Question C12 located below the fire floor, 7 or 27% indicated seeing smoke in their corridor. Three of them who were located on the 4thfloor mentioned perceiving grey or light smoke in their corridor while 4 respondents on the 5th floor said they saw grey or black smoke in their corridor.

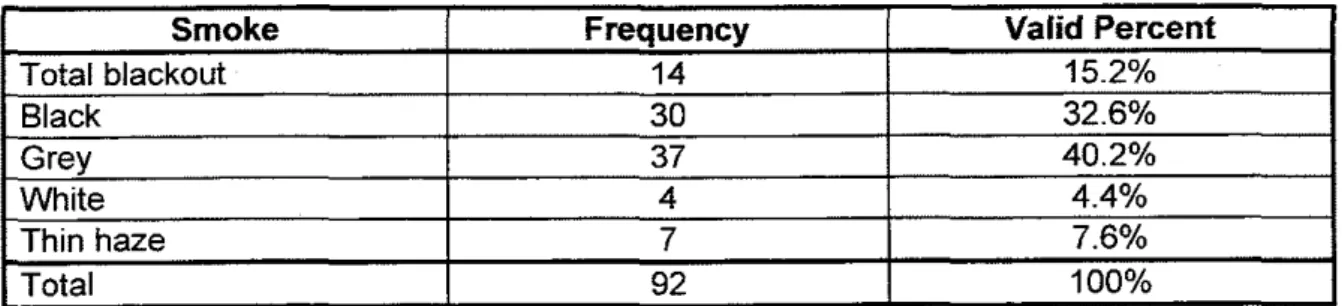

The colour of the smoke encountered in the corridor by the 92 respondents to Question C12(a) vaned from a "total blackout" to "thin haze", as presented in Table 8. The respondents' description of the smoke colour and their movement under these conditions, indicates that most were prepared to move through a certain amount of smoke to evacuate the building.

TABLE 8: Smoke Colour

Smoke Total blackout Black Grey White Thin haze Total Frequency 14 30 37 4 7 92 Valid Percent 15.2% 32.6% 40.2% 4.4% 7.6%

.

100%Among the 102 respondents who mentioned encountering smoke in the corridor, 36 or 35% were from Wing A, the wing of fire origin, 37 or 36% from Wing B and 29 or 29% from W~ng C. There were significantly more occupants in Wings A and B reporting total blackout or black smoke than in Wing C.

There is a relationship between the smoke colour described and the distance of visibility. Some 74 respondents specified how far they could see through smoke, as presented in Table 9.

TABLE 9: Distance o f Visibility

The 33 respondents who answered that they could see "nothing at all" or "little" in the corridor were in units located on all floors of the building from the 4th floor through the 25th. The 22 respondents who said they could see between 40 to 60 feet were able to see the exit stairwell door from their apartment entrance door when they started to evacuate. These respondents were located on the lst, 4th, 8th to 12th, 16th to 19th. 21st, 22nd and 24th floors. Distance 0

-

Nothing at all little 1 to 9 feet 10 to 39 feet 40 to 60 feet TotalOnly 5 or 4% out of 117 respondents to Question C13 indicated that they

encountered heat in the corridor. One respondent who was located on the fire floor went through smoke and heat to evacuate. Another respondent on the 14th floor and 1 on the 21st who encountered heat in their corridor took refuge in a neighbouts apartment. One respondent on the 20th floor who encountered heat returned home and only 1

respondent from the 19th floor who encountered heat on her floor went ahead into the stairwell to evacuate.

Out of 137 respondents, 114 or 83% attempted to evacuate the building during the fire. Of these 114, only 61 or 54% managed to escape, 4 of them being helped in the stairwells by the firefighters and 2 by the Resident Manager. The 53 or 46% of the respondents who were unsuccessful in their attempt to evacuate had to return to their own apartment or to seek refuge in someone else's apartment.

Frequency 15 18 13 6 22 74

9.3

Return to Apartment or Seek RefugeValid Percent 20.3% 24.3% 17.6% 8.1% 29.7% 100%

The 29, or 25% of 114 respondents, who decided to return to their apartment after an initial attempt to evacuate, said they went back because of the smoke condition either in the corridor or in the stairwell. The respondents who returned to their unit had their apartment on Floors 3,

5,

7 to 10, 12 to 21, and 23 to 25. All the respondents whodecided to return home had dressed in winter clothing for the evacuation. A total of 16 respondents went to look in the stairwell before deciding to return home. The other 13 respondents went down a number of floors before turning back up to return home as presented in Table 10. It is interesting to note that the 4 respondents who travelled down more than 6 floors before turning back up to go home were all females, alone and over 65 years old.

TABLE 10: Number of Floors Travelled before Returning Home

-- - -

Another 24, or 21% out of 114, respondents had to seek refuge in someone else's apartment after starting their evacuation. The reasons given for seeking refuge were the smoke conditions and the fact that they thought they could not make it back to their own apartment. These apartments of refuge were found on Floors 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12,

14. 15. 16 and 17. For 1 of the respondents it is not known how many floors were

Floors Travelled 2 down I 2 up 3 down I 3 up 4 down 1 4 up 5 down 15 up 6 down 1 6 up 8 down 18 up 10 down 110 up 14down 114 up Total . .

travelled or where he took refuge. six of the respondents took refuge in a neighbour's a~artment on the same floor. The other 17 respondents travelled a number of floors

Frequency 1 1 5 2 1 1 1 1 13

down before seeking refuge as presented in

able

11. It can be noted that the person who travelled down 8 floors went back up 3 floors before seeking refuge, another one who travelled 11 floors down went back up 1 floor before seeking refuge.TABLE 11: Number of Floors Travelled before Seeking Refuge Floors Travelled 4 down 5 down 6 down 8 down 10 down I I down 13 down Total Frequency 3 5 2 1

-

2 3 1 179.4 Use o f Elevator and Stair

Only one respondent mentioned using the elevator. This respondent was part of a group of 2 that was located on the 4th floor. They saw the fire from their apartment window, went into the corridor to pull the fire alarm and then left by the elevator. They probably triggered the fire alarm within 1 or 2 minutes of the first 91 1 call and before the fire department's arrival on location. Some other occupants may have tried to call the elevator but all 4 elevators were recalled to the ground floor of the building upon fire alarm activation.

Among 119 respondents to Question C17 (see Appendix

B),

I 0 0 or 84% said they used the stairwells. Out of 100 respondents to Question C18, 24 or 24% mentioned they used more than one stairwell to attempt to evacuate. It is not known which of the three stairwells they used.Most respondents to the questionnaire, 86 or 82% out of 105, said there was smoke in the stairwells. Smoke was encountered at different levels from the 4th floor to the 25th floor. Among the respondents, 19 or 18% mentioned not seeing smoke in the stairwells. Of these, 15 entered a stairwell below the fire floor, 2 entered a stairwell on the 7th floor, 1 on the 10th floor and 1 on the 21st floor.

0 5 10 15 20 25

Floor

Among the 80 respondents who encountered smoke in the stairwells and

answered Question C19(b) 'What was your response?" the largest group of respondents (27 or 34%) said they "Kept going down". Another 25 or 31%, "Reversed direction, and went up stairs". in addition, 9 respondents (1 1%) indicated "Sought refuge", 8

respondents (10%) "Changed stairs, and reached outside by alternate exit stair". Many selected more than one option as 6 respondents (7%) selected "Kept going down" and "Sought refuge", 2 respondents (3%) "Reverse direction" and "Sought refuge", 2 (3%)

"Change stairs" and "Reverse direction", and 1 (1%) "Kept going down" and "Reverse direction".

Out of 102 respondents to Question C20, 7 or 7% mentioned that they encountered heat in the stairwell. Of the 6 respondents who mentioned a location,

2 indicated heat on the 10th floor and 1 respondent at each of the following floors: 8, 11, 14 and 20. It is not known when and in which of the three stairwells these respondents were located when they encountered heat.

10.0 REMAINED IN BUILDING

Amongst the 137 returned questionnaires it can be concluded that occupants of 76 apartments either chose or were forced to remain in the building during the fire. Respondents who hung around on the ground floor lobby or who were directed to the party room by the fire department are not considered as having remained in an apartment in the building.

10.1 Stay, Return or Take Refuge in an Apartment

A total of 23 or 19% out of 122 respondents to Question D l (see Appendix B) indicated that they made the decision to stay in their own apartment during the fire. These occupants never attempted to evacuate the building. Of these, 12 indicated having a limitation or disability. Although some had a look in the corridor, they never dressed to leave or go to the stairwell. These respondents were located on floors 5, 6, 8 to 11, 1 3 t o 15, 1 7 t o 19and23to25.

As presented in Section 9.3 of this report, an additional 24 respondents or 21%, mentioned that they took refuge in someone else's apartment after an attempt to evacuate. Also, a total of 29 or 25% out of 114 respondents returned to their own apartment after an initial attempt to evacuate and consequently stayed in the building during the fire.

10.2 Reasons for Staying in Building

Amongst the options offered to Question D3 "What was your reason for staying in the building during the fire?" most of the 76 respondents to this question chose more than one reason. Table 12 shows the tabulated responses.

22

TABLE 12: Reasons for Staying i n Apartment

It appears that all respondents understood that there was an actual fire in the building. Among the options offered, a majority of respondents identified that they tried to leave but could not because of the smoke encountered. Some respondents added that they could not manage the stairs due to a limitation, while others indicated that staying in an apartment was the best thing to do.

Reason Tried to leave, but had to return Smoke in corridor

Told to stay

Didn't know what else to do Didn't know it was a real fire Other

10.3 Number of Occupants

in

ApartmentsFrequency 51 42 15 9 0 14

A majority of the respondents who stayed in the building were in groups, as presented in Table 13. Out of 76 respondents to Question D4, a total of 49 respondents (64%) were in groups, which varied in size from 2 to 15 persons. The other

27 respondents (36%) were alone in their apartment during the fire. Of those persons home alone 1 man was aged 46-65,4 men were over 65 years old, 3 women were aged 46-65 and 19 women were over 65 years old. There were respondents home alone on every floor above the fire floor, except on the 7th, 12th, 15th and 22nd floor.

TABLE 13: Number of Occupants per Apartment

10.4 Protective Actions while i n Apartment

For those respondents who stayed in an apartment during the fire, 62 or 63% out of 99 respondents indicated sealing the main apartment door. Of the 62 respondents who specified what they used to seal the door, 55 or 89% used a towel, 6 or 10% used a towel and tape, and 1 used tape only. Regarding the apartment ventilation,

7 respondents mentioned that they sealed it off. These respondents were located on the 6th, 7th, loth, 16th, 18th, 24th and 25th floors. Two specified that they used cardboard

Valid Percent 35.5% 40.8% 13.2% 10.5% 100% Number 1 person 2 to 4 persons 5 to 9 persons 10 to I 5 persons Total Frequency 27 31 10 8 76

and tape to seal the ventilation, 2 others turned off the bathroom vent and 1 used paper to prevent the smoke from entering.

Smoke migrated into apartments through the entrance door of 55 or 56% of the 99 respondents to Question D7 and through ventilation openings of 22 or 36% out of 61 respondents. In most cases, this smoke migration occurred before towels, cardboard and tape were put in place.

10.5 Use of Balcony and Windows

All the apartments had one or two balconies. In total, 58 or 54% out of

108 respondents mentioned using their balcony. In most cases, the occupants did not stay on the balcony for a long time. Respondents had a choice of 4 options to answer the Question D9(b) 'Why did you go out onto the balcony?". Typically, respondents ticked more than one option; 21 stepped out to watch the fire department, 25 to escape the smoke and 17 to obtain information.

1 1 0 INFORMATION ON FIRE SAFETY

A majority of 96 or 80% of 120 respondents felt that they had adequate fire safety knowledge to prepare for this emergency.

Opinions are split on what occupants should do in a future fire. Out of

128 respondents, 67 or 52% would react in the same way as they did during this fire. The other 61 or 48% would do things differently, which in most cases is to stay in their apartment and protect in place. Many mentioned they would not follow voice

communication instructions anymore.

Out of 125 respondents, a majority of them (101 or 81%) said they would like to obtain more information on fire safety. Most of them would like receiving information through more than one means; 49 indicated "Brochure", 42 "Fire Safety Lecture" and 28 "Video".

12.0 COMPARISON OF OCCUPANTS UP TO AND OVER 65 YEARS OLD

Among the 129 respondents aged over 65 years old, 54 females and 9 males were alone in their unit at the start of the fire. It is interesting to compare the behaviour of these older occupants to occupants alone up to the age of 65. There were

22 occupants up to the age of 65, 13 females and 9 males, who were also alone in their apartment at the time of the fire. The occupants who were alone were specifically selected because they were not influenced by other occupants and had to decide for themselves the best course of action.

There is no significant difference between respondents alone up to and over the age of 65 regarding the time they took before attempting to evacuate the building. Both groups usually started to evacuate when instructed by the voice communication system

and estimated it took them an average of 5 to 10 minutes to start. A total of

21 respondents up to the age of 65 and 50 respondents over 65 years old indicated the cues that initiated their movement. The cues identified are similar for the two groups, as presented in Table 14.

TABLE 14: Cue Initiating Evacuation for Occupants Up to and Over 65 Years Old

The activities respondents engaged in before they started to evacuate are not significantly different according to the age of the occupants. A majority decided to get dressed before leaving, which represents 62% of respondents up to 65 years old and 58% for the ones over 65. The second favourite activity was to get belongings; this was the answer for 15% of the respondents up to 65 and 19% over the age of 65.

There is a significant difference between the two groups regarding the following behaviour: staying in their own apartment, returning to their own apartment after an attempt to evacuate and looking for a refuge in someone else's apartment. Table 15 presents the frequency of these behaviours for the two groups.

TABLE 15: Different Behaviour for Respondents Up to and Over 65 Years Old

There are significantly more respondents over

65

years old who decided to stay in their apartment after receiving fire cues than younger respondents. To Question@I

"Did you stay in your apartment during the fire?",

19%

of the respondents over65

answered yes while only9%

of the respondents up to65

said the same.Question

C14

asked, "Did you return to your apartment?". It implied that the occupant had made an attempt to evacuate. Among the respondents over65,22%

mentioned that they returned to their apartment, while only9%

of the respondents up to65

said the same. There is also a significant difference between age groups for the behaviour of seeking refuge in someone else's apartment. A total of8

respondents up to the age of65

(representing36%

of this group), said they had to seek refuge while only1 1

respondents over the age of65,

which represents18%

of that group, sought refuge. Interestingly, the percentage of respondents who were alone and managed to escape by themselves is very comparable for people up to or over65

years old,46%

and41

% respectively. The percentage of occupants alone who escaped by themselves is also comparable for those whose apartments are above the fire floor: 7 or 32% up to65

years old and17

or27%

over65

years old.13.0 DISCUSSION

This fire incident resulted in many interesting findings regarding the occupants' behaviour. The impact of the evacuation procedure for this building, which advised occupants to follow voice communication instruction, the age and characteristics of the occupants, as well as the impact of this fire experience on occupants' attitudes toward evacuation and fire safety are noteworthy. It is also important to comment on the limitations of the questionnaire used in this research.

1 3 . Evacuation Procedure

The evacuation procedure for this building was that upon hearing the fire alarm, occupants were to investigate to ensure that the fire was not in their own apartment, then to wait for instructions coming through the voice communication system. Consequently, it is not surprising that most occupants waited to receive instructions before initiating their evacuation. In fact, only

4.3%

of respondents initiated evacuation based solely onhearing the building fire alarm. This confirms the 0bse~ation made in a number of evacuations that most occupants treat the sounding of a fire alarm as a warning and wait for further information over the voice communication system, or from other means,

before starting to evacuate.

The building occupants prefer this practice of waiting for voice communication instructions before starting to evacuate because it can prevent them from evacuating unnecessarily if the alarm activation is provoked by a false alarm or a test of the system. This procedure implies, however, that in the event of a fire there will be a delay between the time when the alarm is activated and the time at which occupants receive the

instruction to evacuate. This time delay is a result of the building management or the fire department investigating and assessing the situation before the evacuation order is given through the voice communication system. This investigation and assessment time can be a few or many minutes.

In the case of the Ambleside fire, it is assumed that the fire alarm was activated 1 or 2 minutes after the first 91 1 call, which was at 1634, and the message to evacuate was probably issued at around 16:40, 1 minute after the arrival of the fire department at 16:39. These times suppose a 5-minute delay between the fire alarm sounding and the evacuation order. From the time the message was issued, occupants spent maybe another 2-3 minutes getting dressed and finding their belongings before leaving their apartment. In the best case, it can be assumed that occupants started their evacuation 7 to 8 minutes after the alarm activation. A time delay of 5 to 10 minutes to start

evacuation was confirmed by the questionnaire respondents.

For occupants to start their evacuation a good 10 minutes into the fire could be risky unless the building is very well pressurized and nobody opens doors on the fire floor that would let smoke spread to other locations, such as the stairwells. The procedure of waiting for instructions from the voice communication system, that is becoming very popular in highrise buildings, implies that the time at which occupants start their evacuation is late into the fire event.

Most fire scenarios predict that a fire that has burned free for 10 minutes emits quantities of smoke, heat and toxic gases that can impede egress. Suite separations will usually provide a means of fire containment for a period of time of typically 10 to

20 minutes. After that, it may be difficult for occupants on the fire floor to leave their apartments. Doors accessing exit stairwells will usually provide 20 to 30 minutes of fire protection to occupants in the stairwells unless occupants movement and fire

suppression activities allow smoke to propagate into them. For these reasons, at some stage of fire development, it may be safer to instruct occupants to stay in their unit and protect in place unless they are at immediate risk.

13.2 Occupants' Age and Characteristics

A different outcome to this fire might have been expected because of the large number of senior occupants and the numerous people with limitations in the building. The results of this study, however, tend to demonstrate that seniors and people with limitations who are living independently do not behave much differently from younger occupants.

The study results show that respondents up to and over the age of 65 are similar in their reactions to the fire while assessing the situation, performing some preparatory actions and in their timing to start evacuation. There are, however, a few differences in behaviour for the two groups. It appears that older occupants were fairly reasonable in their assessment of the situation and of their capacity to evacuate the building. Many made the early decision to stay in their apartment, believing that they were not in a physical condition to reach ground level. Other seniors attempted to evacuate but decided after descending a few floors to return to their apartment. Older occupants appeared reluctant to seek refuge in neighbours' apartments. Younger respondents tended to pursue further their attempt to evacuate and had the tendency to seek refuge in a neighbour's apartment when the conditions worsened.