CONTRIBUTION OF FRONTAL CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW MEASURED BY 99mTc-BICISATE SPECT AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTION DEFICITS TO PREDICTING TREATMENT OUTCOME IN ALCOHOL-DEPENDENT PATIENTS

Texte intégral

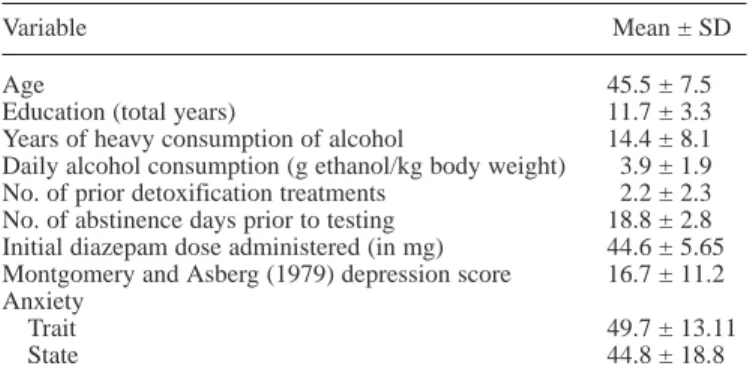

(2) 348. X. NOËL et al.. capacity to coordinate storage and manipulation of information (i.e. working memory). Coincidently, Collette et al. (1999, 2001) examined brain substrate involved in several executive functions. Inhibition processes were related to an increase of metabolism bilaterally in the middle and inferior frontal gyrus (Collette et al., 2001). Manipulation of information in working memory induced activation mainly bilaterally in the middle frontal gyrus and in the left parietal area (Collette et al., 1999). More recently, we conducted a SPECT study in another group of recently detoxified alcoholic subjects (Noël et al., 2001) in order to explore the relationship between inhibition and working memory deficits and cerebral blood flow (CBF) of regions of interest selected on the basis of the PET studies of Collette et al. (1999, 2001). In our study, we explored 20 uncomplicated alcoholic inpatients toward the end of a detoxification programme and 20 control subjects. The results confirmed the existence of deficits affecting inhibition and working memory. In addition, we showed that deficits affecting inhibition processes are specifically correlated with regional CBF (rCBF) in both the bilateral inferior (left and right BA 47) and the median frontal gyrus (BA 47; BA10) but not with a region of reference (occipital/cerebellum). Furthermore, working memory deficits were correlated with the bilateral median frontal (left and right BA10/46) but not with the bilateral parietal area (left BA 7). The aim of the present follow-up study was to examine whether inhibition and working memory deficits (on the Hayling test and the Alpha-span task), assessed when chronic alcoholics had completed a detoxification treatment, along with CBF for their respective regions of interest (measured at the same period with a 99mTc-Bicisate SPECT procedure), can predict a 3-month period of abstinence. SUBJECTS AND METHODS Subjects Alcoholic inpatients were recruited from the Alcohol Detoxification Program of the Brugmann hospital (Noël et al., 2001) and underwent medical, neurological, and psychiatric examinations at the time of selection. They were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Reasons for exclusion were the presence of diagnosis on Axis 1 of DSM-IV other than alcohol dependence, a history of significant medical illness, head injury resulting in loss of consciousness for more than 30 min that would have affected the central nervous system, medication that could influence cognition, and overt cognitive dysfunction as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., 1975). All reported consuming ≥560 g of alcohol weekly for 2 of the 3 years preceding entry into the study. To increase the reliability of anamnestic information, the patient and the family were interviewed separately. The detoxification regime was composed of B vitamins and a standardized fixed reducing course of diazepam. Twenty patients, who had entered the outpatient care programme with the goal of maintaining abstinence, were recruited. After a minimum of 7 days after the last dose of detoxification medication, neuropsychological and SPECT evaluations were conducted. Subjects were abstinent from alcohol for a minimum of 14 days and a maximum of 22 days.. Table 1. Demographic and clinical variables of alcoholic patients Variable. Mean ± SD. Age Education (total years) Years of heavy consumption of alcohol Daily alcohol consumption (g ethanol/kg body weight) No. of prior detoxification treatments No. of abstinence days prior to testing Initial diazepam dose administered (in mg) Montgomery and Asberg (1979) depression score Anxiety Trait State. 45.5 ± 7.5 11.7 ± 3.3 14.4 ± 8.1 3.9 ± 1.9 2.2 ± 2.3 18.8 ± 2.8 44.6 ± 5.65 16.7 ± 11.2 49.7 ± 13.11 44.8 ± 18.8. n = 22.. They were then reinterviewed 2 months later to determine whether they had relapsed, relapse being defined as more than four drinks/day, more than 4 days drinking/week, or situations requiring a new detoxification treatment. The Montgomery and Asberg (1979) depression rating scale and the State–Trait Anxiety Questionnaire (Spielberger, 1993) were used to evaluate severity of depression and anxiety. Clinical and demographical data are presented in Table 1. Neuropsychological assessment Subjects performed the Alpha-span task (Belleville et al., 1998) and the Hayling test (Burgess, 1997). We added abstract reasoning (Progressive Matrices of Raven; Raven, 1960), and an episodic verbal measure [California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT): Delis et al., 1987, 1988]. All tests were performed between 1 and 2 h before the imagery procedure. The Alpha-span task (Belleville et al., 1998) investigates the ability to manipulate information stored in working memory by comparing the recall of information in serial order (involving mainly a storage component) and in alphabetical order (involving storage and manipulation of information). First, a classical word-span task was given to assess the span level of each subject. After the span measurement, the subject was asked to repeat word sequences in two different conditions: direct recall and alphabetical recall. In both conditions, the number of words to be recalled corresponded to the subject’s span minus one item. For example, if subjects performed a span size of five words, they were asked to recall groups of four words in serial and alphabetical order. In the direct condition, the subject performed an immediate serial recall of ten sequences of words. In the alphabetical condition, the subject was asked to recall ten sequences of words in their alphabetical order. Performance was assessed by comparing the performance in alphabetical recall with that in serial recall. In addition, a score was derived for each subject as follows: [(score in direct condition – score in alphabetical condition)/ direct condition] × 100. This represents the reduction in performance in the alphabetical relative to the direct recall condition shown by each subject. The Hayling task (Burgess, 1997, French adapted version, Meulemans et al., 2001) assesses the capacity to suppress (inhibit) an habitual response. The test consisted of two sections (A and B) of 15 sentences each, in which the last word was missing. Sentences were read aloud by the experimenter..

(3) CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW AND ALCOHOL TREATMENT OUTCOME. In section A (initiation/automatic) subjects were asked to give the word that made sense. In section B (inhibition), participants were asked to give a word that made no sense at all in the context of the sentence. These responses were scored 3 if the word made sense of the sentence, 1 if, although not making sense, it was semantically connected to the sentence and 0 if it made no sense at all. In both sections, subjects were asked to reply as quickly as possible and performance was measured by the time taken to respond (latency). The Raven’s Progressive Matrix (Raven, 1960) is a multichoice test of reasoning ability that is intended to make few demands on the subject’s verbal skills. Each of the 60 items contains an incomplete figure. The subject’s task is to select the response that best completes the stimulus figure from the six to eight alternatives presented beneath. The CVLT (Delis et al., 1987, 1988 consists of five learning trials of a 16-word target list. The mean number of words correctly recalled in the five trials was calculated. Brain SPECT procedure Cerebral imaging was done with 99mTc-Bicisate (Neurolite; Dupont Pharma) using a gamma camera (Sopha DSX rectangular) equipped with a high-resolution parallel collimator. The energy window was set to 140 KeV ± 10%. A syringe containing the 740 Mbq dose in a small volume (± 1 ml) was placed on the bed, and counted for 1 min just before injection to get the. 349. injected dose, and then under the patient’s head to measure the cranial attenuation. The bolus was injected via an antecubital vein catheter and a 150 × 1 s dynamic acquisition was performed using 128 × 128 matrix size. After this equilibrium period, CBF distribution was measured by SPECT: the camera performed a 64-step 360° rotation. Each projection (128 × 128 matrix) had a 15 s preset time. Reconstruction was performed by filtered back projection using a Hann filter (cut-off 1 Ny) without attenuation correction. Sagittal slices were rotated to horizontalize the y-axis (see Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) and summed by 3 to obtain six 14 mm slices centred on each stereotactic coordinate. For dynamic processing, a cerebral region was drawn and a 150 × 1 s curve derived. After a short uptake period, a plateau was reached. The mean value between 60 s and 90 s after the maximum was compared to the injected dose and corrected for cranial attenuation. For slice processing, all regions took the form of a cube: 3 × 3 pixels area and 3 pixels depth of slice. The size of one pixel is 4.6 mm; therefore, each side of the regions of interest was ~14 mm. The regions of interest were selected from data showing that the inhibition process of the Hayling test involves bilateral BA 10 and BA 47 (Collette et al., 2001), and that the manipulation of information in working memory involves bilateral BA 10/46 and left BA 7 (Collette et al., 1999, see Fig. 1). Since no relationship has been found between occipital lobe metabolism, inhibition and working memory (Collette et al., 1999, 2001),. Fig. 1. On the left side, sagittal view of the brain showing our localizations of regions of interest for both the Alpha-span and Hayling tests in a normal subject. On the right side, sagittal view of the brain showing activation in black for performance of the Alpha-span and Hayling tests (data from Collette et al., 1999, 2001). Reproduced from Nöel et al., 2001..

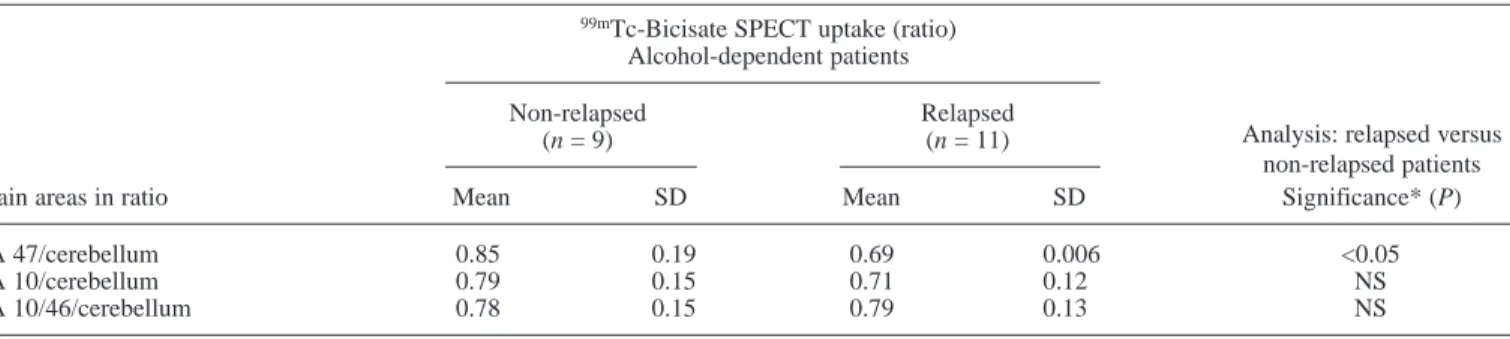

(4) 350. X. NOËL et al.. bilateral CBF (mean CBF of left and right occipital regions of interest) measured in BA 19 was our region of reference. Moreover, in the SPECT study conducted with the detoxified alcoholics selected in the present work, the rCBF in the bilateral inferior (BA47) and the median (BA 10) frontal gyrus had been correlated with inhibition performance measured by the Hayling test (Noël et al., 2001). Therefore, these and the BA 10/46 were selected in this study. SPECT imaging data were evaluated by semiquantitative analysis and calculated as the ratio of mean cortical regions of interest activity to mean cerebellar activity. We chose cerebral activity to normalize the data, because it was reported that CBF did not change in alcoholics unless cerebral degeneration occurred (Gilman et al., 1990; Melgaard et al., 1990). Statistics Pearson’s product-moment correlation, two-tailed Student’s test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc analyses (Newman–Keuls test) with an α level of 0.05 and χ2-test were applied. Correction for multiple comparisons was realized using the Bonferroni correction. All analyses were performed using SPSS 8.0. (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). RESULTS Nine of the alcohol-dependent patients had not relapsed during the 3-month period; 11 relapsed. These two groups did not differ in age; the mean age (± SD) of the non-relapsed patients was 42.1 ± 7.5 years, whereas that of the relapsed patients was 48.6 ± 6.6 (t = 2.53, df = 18, P = 0.053). They also did not differ in gender (χ2 = 1.8, df = 1, P = 0.2), nicotine use (t = 0.04, df = 18, P = 0.97), duration of alcohol misuse (t = –0.09, df = 18, P = 0.93), number of previous detoxifications (t = 0.04, df = 18, P = 0.97), amount of ethanol consumed the month prior to admission to the detoxification programme (t = 0.94, df = 18, P = 0.35), state anxiety (t = 0.7, df = 18, P = 0.49), trait anxiety (t = –0.69, df = 18, P = 0.5), or depression (t = –0.24, df = 18, P = 0.82). Neuropsychological measures On the Alpha-span task, the t-test was used to compare the verbal span size of relapsers (mean ± SD = 4.1 ± 0.6) and abstainers (4.3 ± 0.67). The analysis revealed that the two groups had comparable span size [t(1,18) = –0.87, P = 0.39]. Furthermore, performances on the serial and alphabetical conditions were analysed by means of a two-way ANOVA 2 groups (relapsers, abstainers) × 2 conditions (serial, alphabetic recall). The analysis revealed a main effect of condition [F(1,18) = 111.7, P < 0.001] and of group [F(1,18) = 5.7, P < 0.05]. A significant interaction between group and type of recall was also found [F(1,18) = 8.4, P = 0.01]. Post-hoc analysis revealed that abstainers had a higher score than relapsers on the alphabetical but not on the serial condition (Fig. 2). Finally, the manipulation score differed significantly between both groups [t(1,18) = 2.4, P < 0.05] indicating that relapsers showed a larger performance decrease between serial and alphabetical recall than abstainers. On the Hayling test, the average response latencies (sum of latencies across 15 trials in seconds) in section A were 12.3 ± 0.7 and 12.5 ± 0.8 for abstainers and relapsers. Fig. 2. Comparisons between performances on the serial and the alphabetical recall of the Alpha-span test in abstainers and relapsers. Results are presented as mean ± SD. *Post hoc analysis indicated alcoholic subjects performing less well only in alphabetic recall (P < 0.05).. respectively. The same measure in section B was 59.1 ± 35.8 and 92.8 ± 40. The 2 (group) × 2 (section) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of section [F(1,18) = 111.7, P < 0.001] and a tendency towards a group effect [F(1,18) = 3.8, P = 0.07]. The interaction between these two factors also failed to reach significance [F(1,18) = 3.9, P = 0.07] Concerning part A, both the abstainers and the relapsers always gave the correct response. On section B (see Table 2), relapsers gave more expected words (error score 3) [t(1,18) = –3.1, P < 0.01] and gave fewer unrelated words (error score 0) [t(1,18) = 2.24, P < 0.05] than abstainers. Nevertheless, they did not give more words semantically linked to the expected word (error score 1) [t(1,18) = –0.9, P = 0.37]. The overall error scores (sum of score 0, 1 and 3) were 6.4 ± 2.8 and 9.5 ± 3.3 for abstainers and relapsers, respectively. A t-test revealed that relapsers showed a higher overall error score than abstainers [t(1,18) = –2.24, P < 0.05]. On the CVLT, abstainers and relapsers recalled 10.1 ± 3.3 and 9.4 ± 2.1 correct words respectively. The performance of the two groups did not differ significantly [t(1,18) = 0.61, P = 0.55]. The scores on the PM 38 were 38.3 ± 10.1 for alcoholics who relapsed and 37.9 ± 6.1 for those who did not. Here again, there was no significant difference between the two groups [t(1,18) = 0.11, P = 0.9]. Global CBF uptake The mean + SEM brain uptake, strongly related to global CBF, was 7.65 + 1.59%. It should be noted that the total brain uptake of 99mTc-Bicisate in our sample is quite similar to the mean brain uptake data for normal subjects reported by Dupont Pharma, the manufacturer, and other studies (Friberg, 1994; Pupi, 1994). Thus, differences between our sample of.

(5) CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW AND ALCOHOL TREATMENT OUTCOME. 351. Table 2. Average number of errors made by participants on the Hayling test Abstainers (n = 9) Errors No. of errors scoring 3 No. of errors scoring 1 No. of correct responses (score 0). Table 3.. 99m. Relapsers (n = 11). Mean. SD. Mean. SD. Significance (P). 0.1 6.1 8.5. 0.3 2.5 2.8. 0.81 7 5.4. 0.6 2.2 3.3. <0.01 NS <0.05. Tc-Bicisate SPECT brain ratio in 20 alcohol-dependent patients who did or did not relapse 2 months after hospital discharge 99m. Tc-Bicisate SPECT uptake (ratio) Alcohol-dependent patients. Non-relapsed (n = 9). Relapsed (n = 11). Brain areas in ratio. Mean. SD. Mean. SD. Analysis: relapsed versus non-relapsed patients Significance* (P). BA 47/cerebellum BA 10/cerebellum BA 10/46/cerebellum. 0.85 0.79 0.78. 0.19 0.15 0.15. 0.69 0.71 0.79. 0.006 0.12 0.13. <0.05 NS NS. *Post hoc t-test with Bonferroni correction. NS, not significant.. alcoholic participants and normal subjects appear to characterize rCBF distribution, but not global brain perfusion. Regional CBF measures These are shown in Table 3. In order to compare the CBF measured in BA 47, BA 10 and BA 10/46 in relapsers and abstainers, t-tests were computed, revealing that relapsers had lower CBF in BA47 than abstainers. The two groups did not differ with regard to the CBF measured in BA 10 and 10/46. DISCUSSION The objective of this follow-up study was to assess in alcoholic subjects whether the capacity to inhibit and to manipulate information stored in working memory and related brain activity, measured during a period of a detoxification programme, could predict short-term alcohol relapse. It appeared that, 2 months after hospital discharge, >50% of the alcoholics (11 out of 20) had resumed consuming significant doses of alcohol. This percentage is in general agreement with abstinence rates documented in other studies (Hunt et al., 1971; O’Malley et al., 1992; Volpicelli et al., 1992). Those who relapsed showed, in the period of the detoxification, a significantly poorer performance, on the Alpha-span task and on the Hayling test, than those who did not. In contrast, the two alcohol-dependent subgroups did not significantly differ on episodic memory and abstract reasoning tasks. Relapsers also showed lower 99mTc-Bicisate SPECT uptake in the bilateral middle frontal gyrus area (BA 47). These results are in accordance with those of previous studies showing that relapsers performed worse than abstainers on neuropsychological testing (Abbott and Gregson, 1981; Fabian and Parsons, 1983; Parsons et al., 1990). However, our data suggest that the inhibition and working memory deficits. constitute a better predictor of short-term alcohol relapse than multi-determined tasks (involving executive and nonexecutive functions, e.g. PM 38 and free recall of CVLT). This observation, of lower executive (inhibition and working memory) abilities in alcoholic subjects who relapse 2 months after discharge from a detoxification programme than in those who did not, has led us to formulate some clinical proposals. First, these results are consistent with Tiffany’s (1990) view that executive or non-automatic functions are crucial to control ‘largely automatic’ drug-use behaviours and consequently to prevent alcoholic relapse. The question could also be formulated in terms of the control to action model developed by Norman and Shallice (1980). This model distinguishes two control to action mechanisms. The first, called contention scheduling, is involved in routine situations in which actions are triggered automatically. The second, called the Supervisory Attentional System (SAS), is a separate mechanism at the highest level of control of action, coping with novelty. This mechanism is required in situations where the routine selection of an action is unsatisfactory, and is involved in the genesis of plans and willed actions. In alcoholism, the repeated consumption of alcohol leads to the development of reflexive actions and thoughts. These reflexes may be triggered by external (e.g. smell of alcohol) or internal cues (e.g. stress, withdrawal signs), and lead to the consumption of alcohol. The inhibition of these automatic responses appears to depend on the SAS. In this context, deficits affecting the SAS represent a main risk factor of relapse in alcoholics. However, the precise relationship between SAS (executive) deficits and alcohol relapse is far from clear and represents an exciting challenge for further investigations. An interesting speculation could be that individuals with SAS deficits may lack the mental resources required to appraise accurately high-risk situations, and they may fail to generate and implement coping strategies that could play an important role in, at least,.

(6) 352. X. NOËL et al.. delaying relapse into addiction and thus preventing harmful recurrence of alcohol consumption (Monti et al., 1989; Cooper et al., 1992). More specifically, inhibition, defined as the capacity to suppress a dominant response, and working memory, that provides the means to hold information in a short-term store for further processing, appear to be critical for activity in everyday life, such as planning daily activities, following a conversation, maintaining and realizing projects or balancing a checkbook, etc. For example, in everyday life, one needs to cope with the unexpected, and show imagination, or creativity requiring the inhibition and coordination of dual tasks. Our results differ from those of Morgenstern and Bates (1999), who showed that executive deficits did not predict poor response to treatment. However, the participants in this latter study were alcoholic patients who participated in a 12step programme and had entered residential or intensive day treatment at a private hospital-based chemical dependency treatment programme. In contrast, most of our patients were included in an individual support therapy but did not benefit from any residential or day treatment. It might be argued that the real impact of executive function deficits on adaptation abilities might, at least partially, be attenuated by a structured environment. Indeed, residential or intensive day treatment or Alcoholics Anonymous sessions could be helpful for planning new activities and for resisting acquired reflexive patterns of thought and action. In our imagery data, relapsers also showed lower 99mTcBicisate SPECT uptake in the bilateral middle frontal gyrus area (BA 47) than those who did not relapse. According to a recent review, the existence of a link between executive functioning and the frontal lobes is now well established (Collette and Van der Linden, 2002). Indeed, some prefrontal areas are activated when normal subjects perform various tasks that explore the central executive of working memory. More specifically, BA 47 has been shown to be involved in inhibition processes as assessed by the interference condition of the Stroop test (i.e. naming the font colour of letters that spell a colour word different from the colour-to-be-named) (George et al., 1994; Taylor et al., 1997; Bush et al., 1998). Also, the Hayling task has been used to study inhibition processes (Nathaniel-James et al., 1997; Collette et al., 2001). Unlike the Nathaniel-James et al.’s (1997) study, which found no supplementary activation when the inhibition condition was compared with the initiation condition, Collette et al. (2001) found the activity of the middle and inferior frontal areas did increase during the inhibition condition. However, in this study, the inferior frontal area (BA 45/47) was already activated when subjects had to initiate a response highly constrained by the context. According to Tompson-Schills et al. (1997), this area is involved in generic semantic retrieval operations, such as the selection and evaluation of a semantic response. Both the initiation and inhibition condition require the evaluation of the appropriateness of the other proffered responses, compared to the expected response. This matching process is more demanding in the inhibition condition than in the initiation condition, since, in the latter, a single correct response exists whereas, in the former, subjects have to choose among a set of appropriate responses the one that is the least related to the sentence. To summarize, our results suggest that a low capacity of inhibition (assessed by means of the Hayling test) as well. as a low capacity to coordinate storage and manipulation of information (assessed by means of the Alpha-span task), and decreased CBF in the inferior frontal gyrus, are related to early relapse in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. Of course, the present findings are quite tentative and further investigation is needed to explore the precise relationship between executive/SAS functions, their neural basis and the processes of alcoholic relapse. Acknowledgements — The authors thank A. M. Moat for his help with the English and all the psychology assistants and social workers for their help in managing data collection.. REFERENCES American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn, revised. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC. Abbott, M. W. and Gregson, R. A. M. (1981) Cognitive dysfunction in the prediction of relapse in alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 43, 230–243. Adams, K. M., Gilman, S., Koeppe, R., Kluin, K. J., Brunberg, J. A., Dede, D., Berent, S. and Kroll, P. D. (1993) Neuropsychological deficits are correlated with frontal hypometabolism in positron emission tomography studies of older alcoholic patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 17, 205–210. Allsop, S., Saunders, B. and Phillips, M. (2000) The process of relapse in severely dependent male problem drinkers. Addiction 95, 95–106. Beatty, W. W., Katzung, V. M., Nixon, S. J. and Moreland, V. J. (1993) Problem-solving deficits in alcoholics: evidence from the California Card Sorting Test. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 54, 687–692. Belleville, S., Rouleau, N. and Caza, N. (1998) Effects of normal aging on the manipulation of information in working memory. Memory and Cognition 26, 572–583. Bergman, H. (1987) Brain dysfunction related to alcoholism: some results from the KARTAD Project, in Neuropsychology of Alcoholism: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment, Parsons, O. A., Butter, N. and Nathan, P. E. eds, pp. 21–44. Guilford Press, New York. Brewer, C. and Perrett, L. (1971) Brain damage due to alcohol consumption: an air-encephalographic psychometric and electroencephalographic study. British Journal of Addiction 66, 170–182. Brown, S. A., Vik, P. W., Patterson, T. S., Grant, I. and Schuckit, M. (1995) Stress, vulnerability and adult alcohol relapse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56, 538–545. Burgess, P. W. (1997) Theory and methodology in executive function research. In Methodology of Frontal and Executive Function, Rabbit, P. ed., pp. 81–116. Psychology Press, Hove, East Sussex. Bush, G., Whalen, P. J., Rosen, B. R., Jenike, M. A., McInerney, S. C., Rauch, S. L. (1998) The counting Stroop: an interference task specialized for functional neuroimaging. Validation study with functional MRI. Human Brain Mapping 6, 270–282. Collette, F. and Van der Linden, M. (2002) Brain imaging of the central executive component of working memory. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews 26, 105–125. Collette, F., Salmon, E., Van der Linden, M., Chicherio, C., Belleville, S., Degueldre, C., Delfiore, G., and Franck, G. (1999) Regional brain activity during tasks devoted to the central executive of working memory. Cognitive Brain Research 7, 411–417. Collette, F., Van der Linden, M., Delfiore, G., Degueldre, C. and Salmon, E. (2001) The functional anatomy of inhibition processes investigated with the Hayling task. NeuroImage, 14, 258–267. Commings, C., Gordon, J. R. and Marlatt, G. A. (1980) Relapse: prevention and prediction. In The Addictive Behaviors: Treatment of Alcoholism, Drug Abuse, Smoking and Obesity, Miller, W. R. ed., pp. 291–321. Pergamon Press, New York. Cooper, M. L., Russell, M., Skinner, J. B., Frone, M. R. and Mudar, P. (1992) Stress and alcohol use: moderating effects of gender, coping,.

(7) CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW AND ALCOHOL TREATMENT OUTCOME and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 101, 139–152. Dao-Castellana, M. H., Samson, Y., Legault, F., Martinot, J. L., Aubin, H. J., Crouzel, C., Feldman, L., Barrucand, D., Rancurel, G., Féline, A. and Syrota, A. (1998) Frontal dysfunction in neurologically normal chronic alcoholic subjects: metabolic and neuropsychological findings. Psychological Medicine 28, 1039–1048. Delis, D. C., Kramer, J. G., Kaplan, E. and Ober, B. A. (1987) The California Verbal Learning Test. The Psychological Corporation, New York. Delis, D. C., Freeland, J., Kramer, J. G. and Kaplan, E. (1988) Integrating clinical assessment with cognitive neuroscience. Construct validation of the California Verbal Learning Test. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46, 123–130. Erbas, B., Bekdik, C., Erbengy, G., Enunlu, T., Aytac, S., Kumbasar, G. and Doan, Y. (1992) Regional cerebral blood flow changes in chronic alcoholism using Tc-99m HMPAO SPECT: Comparaison with CT parameters. Clinical Nuclear Medicine 17, 123–127. Fabian, M. S. and Parsons, O. A. (1983) Differential improvement of functions in recovering alcoholic women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 92, 87–95. Folstein, M. R., Folstein, F. E. and McHugh, P. R. (1975) Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12, 189–198. Friberg, L. (1994) Retention of 99 mTC-Bicisate in the human brain after intracarotid injection. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 14 (Suppl. 1), S19–27. Gansler, D. A., Harris, G. J., Oscar-Berman, M., Streeter, C., Lewis, R. F., Ahmed, I. and Achong, D. (2000) Hypoperfusion of inferior frontal brain regions in abstinent alcoholics: a pilot SPECT study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61, 32–37. George, M. S., Ketter, T. A., Parekh, P. I., Rosinsky, N., Ring, H., Casey, B. J., Trimble, M. R., Horwitz, B., Herscovitch, P. and Post, R. M. (1994) Regional brain activity when selecting a response despite interference: a H2015 PET study of the Stroop and emotional Stroop. Human Brain Mapping 1, 194–209. Gilman, S., Adams, K. and Koeppe, R. A. (1990) Cerebellar and frontal hypometabolism in alcoholic cerebellar degeneration studied with positron emission tomography. Annals of Neurology 28, 775–795. Glenn, S. W., Errico, A. L., Parsons, O. A., King, A. C. and Nixon, S. J. (1993) The role of antisocial, affective, and childhood behavioral characteristics in alcoholics’ neuropsychological performance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 17, 162–169. Goldman, M. S. (1990) Experience-dependent neuropsychological recovery in alcoholics: a task component strategy. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 49, 142–148. Harper, C. and Bumberg, P. (1982) Brain weights in alcoholics. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 45, 838–840. Hua, J., Rourke, S. B., Patterson, T. L., Taylor, M. J. and Grant, I. (1998) Predictors of relapse in long-term abstinent alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 59, 640–646. Hunt, W. A., Barnett, L. W. and Branck, L. G. (1971) Relapse rates in addiction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology 27, 455–456. Jernigan, T. L., Butter, N. and DiTriaglia, G. (1991) Reduced cerebral grey matter observed in alcoholics using magnetic resonance imaging. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 15, 418–427. Jones, B. T. and McMahon, J. (1994) Negative and positive alcohol expectancies as predictors of abstinence after discharge from a residential treatment program: a one-month and three-month followup study in men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55, 543–548. Joyce, E. M., Rio, D. E. and Ruttimann, U. E. (1995) Decreased cingulated and precuneate glucose utilization in alcoholic Korsakoff’s syndrome. Psychological Medicine 20, 321–334. Kessler, R., McGonagle, D. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, G. U., and Kendler, K. S. (1994) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51, 8–19. Knight, R. G. and Longmore, B. E. (1994) Cognitive impairments in alcoholism. In Clinical Neuropsychology of Alcoholism, Muller, D. and Code, C. eds, pp. 234–236. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hove, East Sussex. Kril, J. and Harper, C. G. (1989) Neuronal counts from four cortical regions of alcoholic brains. Acta Neuropathologica 79, 200–204.. 353. Kril, J., Halliday, G. M., Svoboda, M. D. and Cartwright, H. (1997) The cerebral cortex is damaged in chronic alcoholics. Neuroscience 79, 983–998. Melgaard, B., Henriksen, L., Ahlgren, P., Danielsen, U. T., Sorensen, H. and Paulson, O. B. (1990) Regional cerebral blood flow in chronic alcoholics measured by single photon emission computerized tomography. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 82, 87–93. Meulemans, T., Steyaert, M. and Vincent, E. (2001) Evaluation des déficits d’inhibition chez les patients traumatisés crâniens à l’aide du test de Hayling. Poster presented at: Journées de Printemps from the Société de Neuropsychologie de Langue Française May 18–19, Lyon, France. Miller, W. R., Westerberg, V. S., Harris, R. J. and Tonigan, F. S. (1996) What predicts relapse? Prospective testing of antecedent models. Addiction 91, 155–171. Montgomery, S. A. and Asberg, A. (1979) A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 134, 382–389. Monti, P. M., Abrams, D. B., Kadden, R. M. and Cooney, N. l. (1989) Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Coping Skills Training Guide. Guilford Press, New York. Morgenstern, J. and Bates, M. E. (1999) Effects of executive function impairment on change processes and substance use outcomes in 12-step treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60, 846–855. Nathaniel-James, D. A., Fletcher, P. and Frith, C. D. (1997) The functional anatomy of verbal initiation and suppression using the Hayling test. Neuropsychologia 35, 559–566. Nicolas, J. M., Catafau, A. M., Estruch, R., Lomena, F. J., Salamero, M., Herranz, R., Monforte, R., Cardenal, C. and Urbano-Marquez, A. (1993) Regional Cerebral Blood Flow-SPECT in chronic alcoholism: Relation to neuropsychological testing. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 324, 1452–1459. Noël, X., Paternot, J., Van der Linden, M., Sferrazza, R., Verhas, M., Hanak, C., Kornreich, C., Martin, P., De Mol, J., Pelc, I. and Verbanck, P. (2001) Correlation between inhibition, working memory and delimited frontal areas blood flow measured by 99m TC-Bicisate SPECT in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol and Alcoholism 36, 556–563. Norman, D. A. and Shallice, T. (1980) Attention to action: willed and automatic control of behavior. Center for human information processing (Technical Report No. 99). In Consciousness and Self-regulation, Davidson, R. J., Scartz, G. E. and Shapiro, E. eds, pp. 1–18. Plenum Press, New York. O’Malley, S. S., Jaffe, A. J., Chang, G., Schottenfeld, R. S., Meyer, R. E. and Rounsaville, B. (1992) Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 55, 950–957. Parker, E. S., Parker, D. A. and Hodford, L. C. (1991) Specifying the relationship between alcohol use and cognitive loss: the effects of consumption and psychological distress. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 52, 366–373. Parsons, O. A. (1998) Neurocognitive deficits in alcoholics and social drinkers: a continuum? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 22, 954–991. Parsons, O. A., Sheaffer, K. W. and Glenn, S. W. (1990) Does neuropsychological test performance predict resumption of drinking in posttreatment alcoholics? Addictive Behaviors 15, 297–307. Pishkin, E., Lovallo, W. R. and Bourne, L. E. (1985) Chronic alcoholism in males: cognitive deficit as a function of age of onset, age and duration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 9, 400–406. Poldrugo, F. and Forti, B. (1988) Personality disorders and alcoholism treatment outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 21, 171–176. Pupi, A., De Cristofaro, M. T., Passeri, A., Castagnoli, A., Santoro, G. M., Antoniucci D. et al. (1994) Quantitation of brain perfusion with 99mTc-bisicate and single SPECT scan: comparison with microsphere measurements. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 14 (Suppl. 1), S28–35. Raven, J. (1960) Guide to the Standard Progressive Matrices. H. K. Lewis, London. Smith, M. E. and Oscar-Berman, M. (1992) Resource-limited information processing in alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53, 514–518..

(8) 354. X. NOËL et al.. Spielberger, C. D. (1993) State–Trait Anxiety Inventory. Les Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée, Paris. Sullivan, E. V., Mathalon, D., Zipursky, R. B., Kersteen-Tucker, Z., Knight, R. T. and Pfefferbaum, A. (1993) Patterns of regional cortical dysmorphology distinguishing schizophrenia and chronic alcoholism. Psychiatry Research 46, 175–199. Talairach, J. and Tournoux, P. (1988) Co-planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain: 3-Dimensional Proportional System: An Approach to Cerebral Imaging. Thieme, Stuttgart. Tarnai, J. and Young, F. L. (1983) Alcoholic’s personalities: extrovert or introvert? Psychological Reports 53, 123–127. Taylor, S. F., Kornblum, S., Lauber, E. J., Minoshima, S. and Koeppe, R. A. (1997) Isolation of specific interference processing in the Stroop task: PET activation studies. Neuroimage 6, 81–92. Tiffany, S. T. (1990) A cognitive model of drug urges and drug use behavior: role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review 97, 147–168. Tompson-Schills, S. L., D’Esposito, M., Aguirre, G. K. and Farah, M. J. (1997) Role of left inferior prefrontal cortex in retrieval of. semantic knowledge: a reevaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94, 14792–14797. Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Hitzemann, R., Fowler, J. S., Overall, J. E., Burr, G. and Wolf, A. P. (1994) Recovery of brain glucose metabolism in detoxified alcoholics. American Journal of Psychiatry 151, 178–183. Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Overall, J. E., Hitzemann, R., Fowler, L. S., Pappas, N., Frecska, E. and Piscani, K. (1997) Regional brain metabolic response to Lorazepam in alcoholics during early and late alcohol detoxification. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 21, 1278–1284. Volpicelli, J. R., Alterman, A. I., Hayashida, M. and O’Brien, C. P. (1992) Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 876–880. Walker, R. D., Donovan, D. M., Kivlahan, D. R. and O’Leary, M. R. (1983) Length of stay, neuropsychological performance, and aftercare: influences on alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51, 900–911..

(9)

Figure

Documents relatifs

Abstract Levels of support for just world beliefs among young adults (N = 598) from four ex-Yugoslavian countries—Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the former Yugoslav Republic

Plus souvent éloignés de l’emploi, les sortants de contrats aidés du secteur non marchand considèrent davan- tage le passage en contrat aidé comme un moyen de se rapprocher du

represent heterogeneous freezing (e.g. K ¨archer and Lohmann, 2003; Khvorostyanov.. Vali Title Page Abstract Introduction Conclusions References Tables Figures ◭ ◮ ◭ ◮ Back

At higher altitudes the distinction between distant- transported and local Pinus pollen is also sometimes pos- sible on the basis of the stomata record (Fig. 5 a, b, c): Zeneggen

In contrast to the optical birefringence, the dielec- tric permittivity of Py4CEH in the quasistatic limit is char- acterized by a positive dielectric anisotropy in the

We study the problem of learning the optimal policy of an unknown Markov decision process (MDP) by reinforcement leaning (RL) when expert samples (limited in number and/or quality)

In this analysis, the most important result is the significant effect of the font type: Word recognition error rate decreased on average from 0.46 for the Courier font to 0.32 for

Features C# O’Caml Features C# O’Caml classes √ √ inheritance ≡ sub-typing? yes no late binding √ √ overloading √ 3 early binding √ 1 multiple inheritance 4 √