HAL Id: tel-01326580

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01326580

Submitted on 4 Jun 2016HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Dissecting mechanisms underlying increased

TLR7-mediated IFNα production in pDCs in

physiological and pathophysiological settings : between

sex differences and HIV-1-HCV co-infection

Morgane Griesbeck

To cite this version:

Morgane Griesbeck. Dissecting mechanisms underlying increased TLR7-mediated IFNα production in pDCs in physiological and pathophysiological settings : between sex differences and HIV-1-HCV co-infection. Immunology. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, 2015. English. �NNT : 2015PA066444�. �tel-01326580�

Thèse de Doctorat de l’Université Pierre et Marie Curie

Ecole doctorale : Physiologie, Physiopathologie et Thérapeutique (ED394)

Spécialité : Immunologie

Présentée Par

Morgane GRIESBECK

Pour Obtenir le grade de

Docteur de l’Université Pierre et Marie Curie

Sujet de Thèse

Dissecting mechanisms underlying increased TLR7-‐mediated IFNα

production in pDCs in physiological and pathophysiological settings:

Between sex differences and HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection

Soutenue le 2 juin 2015 devant le jury composé de:

Professeur François LEMOINE Président

Docteur Marc DALOD Rapporteur

Docteur David DURANTEL Rapporteur

Docteur Jean-‐Philippe HERBEUVAL Examinateur

Docteur Arnaud MORIS Examinateur

Professeur Brigitte AUTRAN Directeur de these Professeur Marcus ALTFELD Co-‐directeur de thèse

Acknowledgment/Remerciements

To my two co-‐mentors, Pr. Brigitte Autran and Pr. Marcus Altfeld

Dear Marcus, I would like to express my deepest and sincere gratitude to you. It has been a pleasure to work with you from day one. I learned a lot scientifically and humanely. You allowed me to discover many techniques and to participate to international conferences. You taught me to write a grant proposal and scientific articles but also to stay focused. Our discussions were always invigorating. Thanks for having been a dedicated mentor all along.

Dear Brigitte, I would like to thank you for your trust and guidance. Your optimism during the last doubtful months of PhD kept me motivated. I am also grateful for your understanding regarding my trips to Boston. I learned a lot in the past year or so from a clinical perspective and it broadened my thoughts as a researcher.

To the members of my PhD committee

I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Marc Dalod and Dr. David Durantel for the careful review of my manuscript and Pr. François Lemoine for chairing my PhD committee. I also thank Dr. Arnaud Moris for his participation and for being so welcoming on this day back in 2012 at Keystone when I introduced myself as his future (but coming from nowhere) collaborator on autophagy. I would like to particularly thank Dr. Jean-‐Philippe Herbeuval for spending time discussing the organization of the present manuscript. The passion with which you always talked about pDCs and type I IFNs was so very refreshing.

To Judy Chang

You were the first to inspire me to do a PhD and you made it possible. You provided unlimited support in so many instances. I knew I could always rely on you. You taught me everything I know about flow cytometry. You spent time reading over my writings, helping me preparing oral presentations, until I felt confident enough. I loved our discussions. You too were a dedicated mentor to me.

To all the Altfeld’s lab past and present members

Phil, thanks for your precious help. I will always be up for one hazelnut pastry (or two) at Tatte Mike, please stay as you are and stop “freaking out”

Eileen, thanks for your always insightful comments. Your scientific dedication is inspiring.

I would like to thank Stephanie Jost, Christian Korner, Wilfredo Garcia-‐Beltran, Nienke Van Teijlingen, Angelique Hoelzemer, Christine Palmer, Erin Doyle, Robert J. Lindsay and so many others. It was such a pleasure working with you. I also thank Gloria Martrus, Susanne Ziegler, Heike Hildebrandt and Anaïs Chapel for welcoming me at the HPI.

Aux membres de l’équipe du Pr. Autran et aux équipes partenaires

Un énorme merci à ma collègue et amie Zineb Sbihi. Comme je te le dis tout le temps, je ne sais pas comment j’aurais fait sans toi.

Merci à Amandine Emarre et Guislaine Carcelain de m’avoir aidé à surmonter les moments de stress.

Merci à Amélie Guihot, Chiraz Hamimi, Assia Samri, aux filles du T4/T8 et à tous les autres, pour avoir rendu la vie au laboratoire plus agreeable.

Merci à Véronique Morin, Anne Oudin et Rima Zoroob pour m’avoir accueillie dans votre laboratoire de biologie moléculaire et surtout pour m’avoir aidé pour mes expériences de silencing!

Merci à mes collaborateurs du projet HepACT-‐VIH en particulier à Christine Blanc et Michèle Pauchard, au Dr. Marc-‐Antoine Valantin et au Dr. Bottero.

Merci à Catherine Blanc et Aurélien Corneau pour m’avoir épaulé et pour leur aide sur la plateforme de cytométrie

To all the other significant persons I crossed paths with during these almost four years and to my friends

In particular I would like to thank Julie Boucau for our girls and paint nights in Boston and for being an outstanding troubleshooter, to Sylvie LeGall for interesting discussion, to Armon Sharei and Filippos Porichis for critical technical support, Lise Chauveau and Nikaïa Smith for their dedication to silence IRF5 in pDCs.

À ma famille

Maman, sans toi je n’en serais pas là. Ton amour inconditionel est ma plus grande force. Papa merci de t’être si bien occupé de ta grande (et pas toujours très débrouillarde) fille Boubi, merci de me soutenir dans tous mes projets et de croire en moi

Un gros bisou à mes soeurs, Manon et Alix. Je souhaite que nous restions toujours présentes les unes pour les autres

Camille, Titouan et Cathy, merci d’avoir rendu ces moments loin de Georgio plus doux.

Merci à mon papy, mon parrain Michel, à mes tantes Martine et Christine, à mes cousins et cousines, à ma grand-‐mère

Louloute, tu es notre petit rayon de soleil à tous

Une pensée pour toi, Mamie. Je vous garde dans mon coeur, toi et Papy Roland.

Les moments partagés avec vous tous sont les plus précieux à mes yeux. Je vous aime tous profondément.

Georgioyin yév mér éndanikin

Im hokis, gayankis métch bidi chi mornam jamanagnéré vor miyasin antsousink .Ge chénoragalém kéz vor inzi héd jébdatsir amén ourakh adénéré, yév sirdés jébdétousir téjvar jamanagnéré. Chad ourakh yev hébardém amén inchmov vor miyasin gazmétsink.

Méndz chénorhagaloutchiyoun Séllayin, Robinin yev Claudioyin vor kovés nérga gétsan yév tsérkernin pats inzdi

“Tout est mystère et la clé d’un mystère est un autre mystère”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Table of Contents

Résumé de la thèse

... 19

Preface ... 21

Introduction

... 23

I. Orchestration of the multifaceted functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells around IFNα production

... 25

1.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: “Professional producers of IFNα” ... 25

1.1. General characteristics of the plasmacytoid dendritic cells ... 25

1.2. Features of a uniquely powerful IFNα secretion capacity ... 28

1.3. pDC-‐like models ... 30

2.

pDC functions ... 31

2.1

Major role in the orchestration of immune responses following pathogen sensing ... 31

2.2.

Cytotoxic functions of pDCs ... 35

2.3.

Tolerogenic function of pDCs ... 35

II. Regulation of the TLR7/IFN pathway in pDCs ... 37

1.

Fine tuning of type I IFN responses ... 37

1.1. The type I IFNs family and the IFNα subtypes: Between redundancy and specificities ... 37

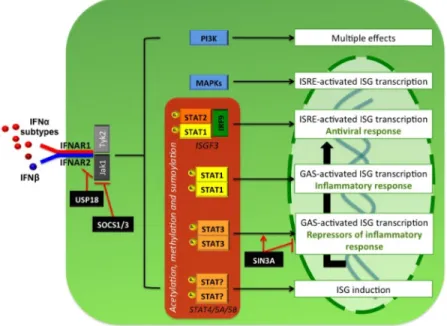

1.2. The canonical type I IFN-‐induced signaling pathway or Jak-‐STAT pathway ... 39

1.3.

Modulation of type I IFN signaling ... 40

1.4. Stochastic nature of ISGs expression ... 41

2. Regulation of the TLR7/TLR9 pathway in pDCs ... 42

2.1. Signaling through endosomal TLR7 and TLR9 ... 42

2.2. Endosomal trafficking ... 43

2.3. pDC-‐specific inhibitory receptors ... 44

3. The interferon regulatory factor 5 ... 45

3.1.

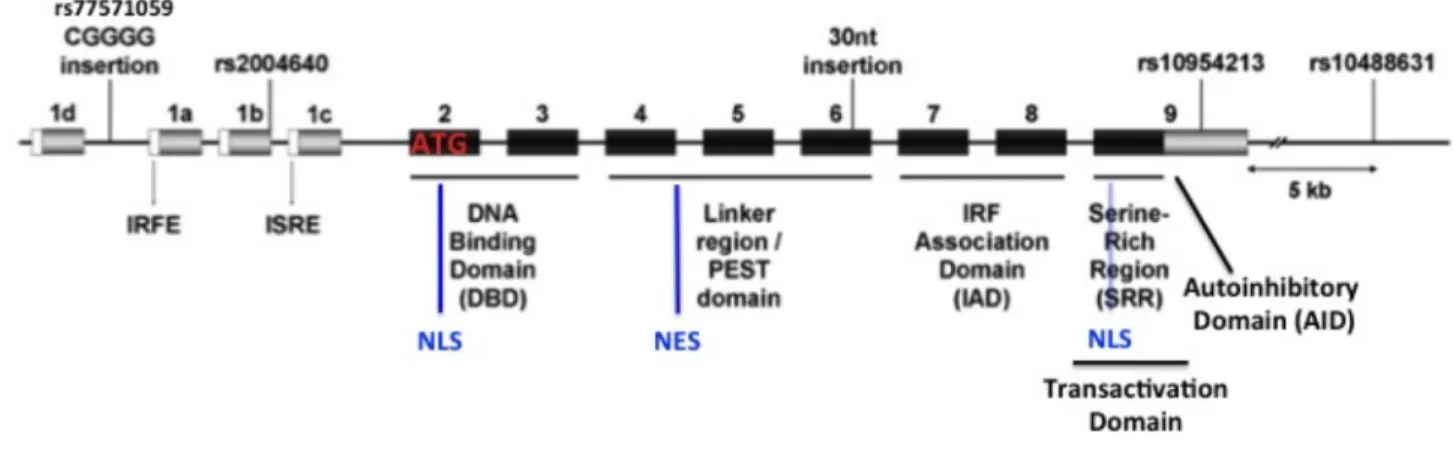

Alternative promoter splicing of IRF5 Gene ... 45

3.2. IRF5 isoforms and cell-‐type specific expression pattern ... 46

3.3. IRF5 activation ... 47

3.4. IRF5 Polymorphism ... 48

3.5. IRF5 functions ... 49

4. Central role of the interferon regulatory factors family in the regulation pDC TLR7/9 responses ... 50

III. Disease-‐promoting type I IFNs ... 53

1. Protective role of type I IFNs ... 53

2. Dichotomic role of type I IFNs in viral infection: Insights from the LCMV model ... 54

3. Deleterious effect of type I IFNs in systemic lupus erythematosus ... 55

IV. Detrimental role of IFNα in chronic HIV-‐1 infection ... 57

1. Immune activation and inflammation as drivers of HIV-‐1 disease progression ... 57

1.1. Phases of HIV-‐1 infection ... 57

1.2. Clinical relevance of HIV-‐1-‐mediated immune activation and inflammation in the context of antiretroviral therapy ... 58

2. Innate sensing of HIV-‐1 and IFNα response ... 60

2.1 TLR7-‐dependent recognition of HIV-‐1 by pDCs as a major driver of IFNα production in HIV-‐1 infection 60

2.2. HIV-‐1 recognition by non-‐pDCs and contribution to IFN response and/or immune activation ... 60

2.3. ISGs induction ... 62

3. Dynamics of pDC in HIV-‐1 infection ... 62

3.1. Susceptibility to HIV-‐1 infection and depletion of pDCs in the peripheral blood in HIV-‐1 infection ... 62

3.2. Rapid and significant recruitment of pDCs to lymph nodes ... 64

3.3. Rapid and long-‐lasting accumulation of pDC in the gut ... 64

3.4. Skewed maturation and persistently IFNα-‐secreting phenotype of pDCs in HIV-‐1 infection ... 65

4.

Role of type I IFN in HIV-‐1-‐mediated chronic immune activation ... 66

4.1. Persistent type I IFN signaling as a characteristics distinguishing pathogenic versus non-‐pathogenic SIV infection ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

4.2. Mechanisms underlying deleterious effect of IFNα ... 68

5. Modulation of type I IFNs responses in HIV-‐1 infection ... 72

5.1. Insights from specific models of infection ... 72

5.2. Targeted modulation of type I IFN signaling in vivo ... 73

V. Sex differences in IFNα and HIV-‐1 infection ... 76

1.

Mechanisms underlying sexual dimorphism in immune responses ... 76

1.1. Sexual dimorphism in immune responses ... 76

1.2.

Modulation of immune responses by estrogen signaling ... 76

1.3. Modulation of immune responses by X-‐linked factors ... 80

2.

Sex differences in the natural course of HIV-‐1 infection ... 80

2.1. Sex differences in HIV-‐1 acquisition and transmission ... 81

2.2. Sex differences in Viral Load and Immunopathology ... 82

3. Sex differences in the production of IFNα ... 84

V. HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection ... 86

1.

Natural course of HCV infection ... 86

1.1. HCV tropism ... 86

1.2. Immune dysfunction in chronic HCV infection ... 86

2.

HCV sensing and IFN induction ... 88

2.1. Innate sensing of HCV ... 88

2.2. pDC sensing of HCV and IFNα production ... 90

2.3. Importance of TLR7 signaling ... 91

2.4. Crosstalk between type I and type III IFNs in HCV infection ... 92

2.5. Mechanisms of HCV interference with the type I IFN response ... 93

3.

HCV treatment outcome and IFNα signaling ... 94

3.1. PegIFNα2/RBV as HCV treatment ... 95

3.2. Association between the pre-‐activation of the IFN pathway and refractiveness to pegIFNα/RBV ... 95

3.3.

Impact of the IFNL polymorphism on HCV treatment ... 96

3.4. IFNα signaling in IFN-‐free regimen ... 97

4.

pDCs in HCV infection ... 98

4.1. Reduced numbers of circulating pDCs in chronic HCV infection and trafficking to the liver ... 98

4.2. pDCs impairment in chronic HCV infection ... 98

4.3. pDCs and PegIFN/Rib treatment ... 99

5.

Increased burden in HCV-‐HIV-‐1-‐coinfection ... 99

5.1. Epidemiological data on the reciprocal effect of HCV and HIV-‐1 on disease progression and mortality 99

5.2. Increased immune activation and inflammation in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infected individuals ... 100

6. Accelerated hepatic fibrosis in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection ... 102

6.1. Evaluation of liver fibrosis in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection ... 102

6.2 Mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis ... 103

6.3 Role of pDCs in liver fibrosis ... 104

6.5. Hepatic fibrosis as a driver of systemic immune activation and inflammation in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection….104

7. Sex differences in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection ... 105

Hypothesis and specific aims

... 111

Results

... 113

Study n°1 ... 115

Study n°2 ... 155

Methods

... 205

Discussion, Presentation of supplementary data and Perspectives

... 215

I. IRF5 as a mediator of increased pDCs IFNα response in females ... 217

1.

Results obtained ... 217

2.

Contribution of IRF5 isoforms and polymorphisms to its role in the transcription of IFNα ... 217

3. How ERα may regulate IRF5 expression and potential role of X-‐chromosome ... 219

4.

Potential role of IRF7 ... 221

5.

Unresolved questions on sex differences in pDC IFNα response and requirements of pertinent models for further studies ... 221

II. Altered IFNα responses and increased inflammation impacts HCV disease severity in ART-‐treated

HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infected patients ... 222

1.

Results obtained ... 222

2. Biological interpretation of the association between ISGs and fibrosis severity ... 223

3. Clinical relevance of our findings and limitations of our study ... 224

III. Relevance of pDC-‐derived type I IFNs as therapeutic target for HIV-‐1 infection ... 225

1. Contribution of pDC-‐derived IFNs in immune responses ... 225

1.1. Evolutionary perspectives ... 225

1.2. Respective role of pDCs and non-‐pDCs cells in type I IFN production during viral infection ... 226

2. Potential of type I IFN inhibition in HIV-‐1 therapeutic strategies ... 227

2.1.Timing and duration: Key consideration for therapeutic blockade of type I IFNs in pDCs in HIV-‐1 infection 2.2. Targeted blockade of type I IFNs action ... 227

2.3. Functional blockade of pDCs ... 228

2.4. Models for in vivo validation ... 231

3. Therapeutic potential of type III IFNs ... 231

IV. Open questions on pDCs and type I IFNs: What I would be interested in studying next ... 232

REFERENCES

... 237

Annexes

... 267

List of abbreviations

3C Chromosome conformation capture 4E-‐BP 4E binding protein

α-‐SMA α-‐smooth-‐muscle actin

ADAR-‐1 Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA-‐1 Ag Antigen

AGM African green monkeys

AIDS Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome ALT Alanine transaminase

AMP Antimicrobial peptide AP-‐1 Activator protein 1

AP-‐3 Adaptor-‐related protein complex 3 APC Antigen-‐presenting cell

APOBEC Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-‐like APRI Aspartate aminotransferase-‐to-‐platelet ratio index

Arm Armstrong strain of LCMV ART Antiretroviral therapy AST Aspartate aminotransferase ATF5 Activating transcription factor 5 AZT Azidothymidine

Bcl2A1 Bcl2-‐related protein A1 BCR B cell receptor

BDCA Blood dendritic cell antigen

Blimp-‐1 B lymphocyte-‐induced maturation protein BLNK B cell linker

BLOC Biogenesis of lysosome-‐related organelle complexes BM Bone marrow

BMI Body mass index BrdU Bromodeoxyuridine

BST-‐2 Bone marrow stromal antigen 2 BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

BTLA B and T lymphocyte attenuator CBP CREB-‐binding protein

CCL C-‐C motif ligand

CCR C-‐C chemokine receptor CD2AP CD2-‐associated protein cDC Conventional dendritic cells

CDC Centers for disease controls and prevention CDLN1 Claudin-‐1

CEB1 HECT And RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 5 ChemR23 Chemerin receptor 23

ChIP Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Cl13 Clone 13 strain of LCMV

CLP Common lymphoid progenitors CMP Common myeloid progenitors CMV Cytomegalovirus

CNS COP9 signalosome

COP9 Constitutive photomorphogenesis 9 CTCF CCCTC binding factor

CTL Cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocyte

CXCL C-‐X-‐C motif ligand

CXCR C-‐X-‐C chemokine receptor

DAA Direct-‐acting antiviral Dap12 DNAX activation protein 12 DBD DNA binding domain DC Dendritic cell

DCIR Dendritic cell immunoreceptor Dcp2 mRNA-‐decapping protein 2

DC-‐SIGN Dendritic cell-‐specific ICAM-‐3-‐grabbing non-‐integrin DHEA Dehydroepiandrosterone

DHEAS Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate Dock2 Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 DR Death receptor

DS Degree of skewing

DSIF DRB sensitivity-‐inducing factor dsRNA/DNA Double-‐stranded RNA/DNA DUSP1 Dual specificity phosphatase 1 E1 Estrone

E2 17β-‐oestradiol E3 Estriol

EC Elite controller ECM Extracellular matrix EGF Epidermal growth factor

EI2AK Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-‐alpha kinase eiF Eukaryotic translation initiation factor

EIF4EBP-‐1 eIF4E-‐binding protein 1 EMP Endothelial microparticule ER Endoplasmic reticulum ER Estrogen receptor

ERE Estrogen responsive element FcγRII Fc-‐gamma receptor II

FISH Fluorescent in situ hybridization Flt-‐3 Fms-‐related tyrosine kinase 3 Flt-‐3L Fms-‐related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand FOXO3 Forkhead box protein O3

FPR3 Formyl peptide receptor 3 FSW Female sex worker

GALT Gut-‐associated lymphoid tissue GAS Gamma interferon activation site GAT1 GATA binding protein 1

GI Gastrointestinal

GM-‐CSF Granulocyte-‐macrophage colony-‐stimulating factor GPER1 G protein-‐coupled estrogen receptor 1

GrB Granzyme B

GWAS Genome-‐wide association study

H3K9me2 Histone mark histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation HAART Highly active antiretroviral treatment

HAT Histone acetyltransferase HCV Hepatitis C virus

HCVcc Cell-‐culture-‐adapted strains of HCV HDAC Histone deacetylase

HEV High endothelial venules HIV-‐1 Human immunodeficiency virus HMGB1 High mobility group B1

HSC Hematopoietic stem cells HSC Hepatic stellate cells

HSD Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase HSP Heat shock protein

HS/PC Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell HSV Herpes simplex virus

I/R Ischemia/reperfusion IAD IRF association domain

ICAM-‐1 Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 ICOS-‐L Inducible T cell co-‐stimulator ligand

IFIT Interferon-‐induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 IFN Interferon

IFNAR IFNalpha receptor

IGF1 Insulin-‐like growth factor 1 IKK IκB kinase

IL Interleukin

ILT-‐7 Immunoglobulin-‐like transcript 7 Indel Insertion/deletion

iNKT Invariant Natural Killer T cell

IDO Indoleamine-‐pyrrole 2,3-‐dioxygenase IDU Intravenous drug user

IFI16 Gamma-‐interferon-‐inducible protein 16 IP-‐10 Interferon γ-‐inducible protein 10 IPC IFN-‐producing cells

IRAK IL-‐1 receptor-‐associated kinase IRES Internal ribosomal entry site IRF Interferon regulatory factor

IRFE Interferon regulatory factor binding element ISG Interferon-‐stimulated genes

ISGF3 ISG factor 3

ISP ISG-‐encoded protein

ISRE IFN-‐stimulated response element

ITAM Immunoreceptor tyrosine-‐based activation motif

Jak1 Receptor-‐associated protein tyrosine kinases Janus kinase 1 JFH-‐1 Japanese fulminant hepatitis-‐1

JNK c-‐Jun N-‐terminal kinase KC Kupffer cells

LAG3 Lymphocyte activation gene 3

LAMP Lysosomal-‐associated membrane protein LAP LC3-‐associated phagocytosis

LBD Ligand-‐binding domain LC Langerhans cells

LC3 Microtubule-‐associated protein 1A/1B-‐light chain 3 LCMV Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

LEAP-‐2 Liver expressed antimicrobial peptide-‐2 LFA Lymphocyte function-‐associated antigen

LILRA4 Leukocyte immunoglobulin-‐like receptor subfamily A member 4 LNA Locked nucleic acid

LN Lymph Node LPS Lipopolysaccharide

MAKK6 Mitogen-‐activated protein kinase kinase 6 MAM Mitochondrial-‐associated membrane MAPK Mitogen-‐activated protein kinase

MARCH1 Membrane-‐associated RING finger protein 1 MAVS Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein Mda-‐5 Melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 MEF Mouse embryonic fibroblast

MEKK1 Mitogen-‐activator protein kinase/extracellular signal-‐regulated kinase (ERK) kinase 1 MFI Mean fluorescence intensity

MHC Major histocompatibility

MIP Macrophage inflammatory protein miR MicroRNA

MMP Matrix metallopeptidase MSM Men who have sex with men MT Microbial translocation

mTOR Mammalian target of rapamycin Mx myxovirus resistance gene

MyD88 Myeloid differentiation primary response gene NCOR2 Nuclear corepressor 2

NDV Newcastle disease virus NASH Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis NELF Negative elongation factor NES Nuclear export sequence

NFATc2 Nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-‐dependent 2 NF-‐κB Nuclear factor-‐kappa B

NHP Non-‐human primate NK Natural killer

NKR-‐P1A NK cell surface inhibitory protein P1A NLRP3 NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 NLS Nuclear localization sequence

NNRTI Non-‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

NRTI Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors OAS 2’, 5’oligoadenylate synthetase

OASL1 2ʹ′-‐5ʹ′-‐oligoadenylate synthase-‐like protein 1 OCLN Occludin

ODN Oligodeoxynucleotide

p70S6K Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, 70kDa, polypeptide 1 PACSIN-‐1 Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons 1 PAMP Pathogen-‐associated molecular pattern

PBMC Peripheral blood mononuclear cell PCR Polymerase chain reaction

pDC Plasmacytoid dendritic cell PD-‐1 Programed death receptor 1 PDGF Platelet-‐derived growth factor PD-‐L1 Programmed death ligand 1

PECAM-‐1 Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1

PEST Proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine (S), and threonine (T)-‐rich pegIFN Pegylated interferon

PHH Primary hepatocyte PI Protease inhibitor

PI3K Phosphoinositide 3-‐kinase

PIAS1 Protein inhibitor of activated STAT1 PKC Protein kinase C

PKR Protein kinase, IFN-‐inducible dsRNA dependent PLSCR1 Phospholipid scramblase 1

PLT Platelet

PP2A Protein phosphatase 2A PrEP Pre-‐exposure prophylaxis

PRMT1 Protein arginine methyl-‐transferase 1 PRR Pattern recognition receptor

PSGL1 P-‐selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 RA Rheumatoid arthritis

RAG Recombination activation gene

RAGE Receptor for advanced glycation end-‐products RANKL Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-‐B ligand RBV Ribavirin

RIG-‐I Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene I RLR RIG-‐I-‐like receptor

RM Rhesus macaques ROS Reactive oxygen species RPS28 Ribosomal protein S28

Runx2 Runt-‐related transcription factor 2 SAMHD1 SAM domain and HD domain 1 SCHL11 Schlafen 11

SETB1 SET domain bifurcated 1

SHP-‐1 SH2 domain containing tyrosine phosphatase 1 Siglec-‐H Sialic-‐acid-‐binding immunoglobulin-‐like lectin SIN3A SIN3 transcription regulator homologue A siRNA Small interfering RNA

SIV Simian immunodeficiency virus

Slc15A4 Solute Carrier Family 15 (Oligopeptide Transporter) Member 4 SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus

SM Sooty mangabeys

SMART Strategies for management of anti-‐retroviral therapy SNP Single nucleotide polymorphism

SOCS Suppressor of cytokine signaling Sp1 Specificity protein 1

SRC-‐1 Steroid receptor coactivator 1 ssRNA Single-‐stranded RNA

STAT Signal transducer and activator of transcription STI Structured treatment interruption

STI Sexually transmitted infection STING Stimulator of interferon genes sTNFR Soluble TNF receptor

SUMO Small ubiquitin-‐related modifier SVR Sustained virological response Syk Spleen tyrosine kinase

TAB2 TAK1-‐binding protein 2

TAK1 Transforming growth factor-‐β-‐activated protein kinase 1 TBK1 TANK binding kinase 1

TCR T cell receptor

TE Transient elastography

TGFβ Transforming growth factor beta

Tim3 T cell immunoglobulin mucin family member 3 TIMP Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase

TIR Toll/IL1 receptor TLR Toll-‐like receptor

TNF Tumor necrosis factor TPO Thrombopoietin

TRAF Tumor necrosis factor-‐associated factor

TRAIL Tumor necrosis factor apoptosis-‐inducing ligand TRIF TIR-‐domain-‐containing adapter-‐inducing IFNβ Treg Regulatory T cells

TREM Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells TREX1 Three prime repair exonuclease 1

TRIM Tripartite motif-‐containing protein Tyk2 Tyrosine kinase 2

UBE2N Ubiquitin-‐conjugating enzyme E2N

UBE2V1 Ubiquitin-‐conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 UNC93B1 Unc93 (C. Elegans) Homolog B

USA United states of America USP18 Ubiquitin-‐specific peptidase UTR Untranslated region

VCAM-‐1 Vascular cell adhesion molecule-‐1

Viperin Virus inhibitory protein, endoplasmic reticulum-‐associated, IFN-‐inducible VL Viral load

VSV Vesicular stomatitis virus WISH Women’s interagency HIV study XBP-‐1 X-‐box binding protein 1

XCI X-‐chromosome inactivation

List of figures

Introduction

Figure 1 pDC morphology

Figure 2 pDC development in the bone marrow Figure 3 Diversity of IFNAR signaling

Figure 4 Regulation of TLR7/9 pathway in pDCs Figure 5 IRF5 gene structure

Figure 6 Role of IRF5 in the modulation of B cell function

Figure 7 Deleterious role of pDC-‐derived IFNα in SLE pathogenesis Figure 8 Evolution of clinical parameters during HIV-‐1 infection Figure 9 HIV-‐1 restriction factors

Figure 10 IFN response and immune activation in pathogenic versus non-‐pathogenic SIV infection Figure 11 Mechanisms underlying dichotomous role of IFNα in HIV-‐1 infection

Figure 12 Mechanisms of action of ERs

Figure 13 Sex differences throughout the course HIV-‐1 infection

Figure 14 Plasma levels of IFNα, peripheral pDCs numbers and clinical parameters during HCV infection Figure 15 Innate sensing of HCV in hepatocytes and pDCs

Figure 16 Crosstalk between IFNα and IFNλ signaling in HCV-‐infected liver

Figure 17 Mechanisms underlying accelerated progression to fibrosis in HIV-‐1-‐HCV co-‐infection

Methods

Figure M1 Principle and workflow of the QuantiGene® FlowRNA Assay

Figure M2 Validation of the QuantiGene® FlowRNA Assay to the study of pDC IFNα pathway

Figure M3 Comprehensive evaluation of TLR7-‐mediated cytokine induction in pDCs from single-‐cell analysis Figure M4 Utilization of the QuantiGene® FlowRNA Assay to quantify IRF5 mRNA levels simultaneously in

multiple PBMCs subsets

Discussion

Figure D1 Supplementary data on sex differences in TLR7/IFNα pathway in pDCs

Figure D2 Association between ISGs levels, IFNAR1 expression and IL28B polymorphism in HCV-‐HIV-‐1 co-‐ infected patients

List of tables

Table 1 Characteristics of pDC-‐like cell lines

Table D1 Fold change in normalized expression of IFN genes upon IRF5 recombinant protein delivery compared to control in sorted pDCs stimulated for 2hours with CL097

Résumé de la thèse

Les interférons de type I (IFN-‐I) peuvent être produits par toutes les cellules mais les rares cellules dendritiques plasmacytoïdes en sont les principales cellules productrices. Ils induisent de nombreux effets antiviraux et immuno-‐modulateurs. Un nombre croissant d’études rapporte leur rôle délétère dans certaines maladies auto-‐ immunes et dans différentes infections virales. L’IFNα orchestre de nombreux mécanismes pathogéniques dans l’infection par le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine de type 1 (VIH-‐1). Bien que les traitements antirétroviraux ont largement contribué à l’amélioration de la qualité de vie des individus infectés par le VIH-‐1, ces derniers sont enclins au développement de maladies non-‐liées au SIDA telles que les maladies cardiovasculaires ou hépatiques. Les défauts d’activation immunitaire et d’inflammation persistant chez ces patients et particulièrement ceux liés au dysfonctionnement de la voie de l’IFNα pourraient être en cause. En l’absence d’une cure fonctionnelle, les stratégies visant à décroître les niveaux d’activation immunitaire et d’inflammation, notamment en ciblant la signalisation de l’IFNα sont pertinentes. Cependant, les mécanismes moléculaires associés à un effet immuno-‐modulatoire donné ne sont qu’incomplètement compris. L’étude de modèles physiologiques et pathophysiologiques peut fournir des informations cruciales sur les moyens d’exploiter la signalisation de l’IFNα dans un but thérapeutique.

Les objectifs de ma thèse se déclinent en deux axes :

1. Identification des mécanismes responsables de la production d’IFNα plus importante chez les femmes par rapport aux hommes : Contribution du facteur régulateur interféron 5 (IRF5)

Les pDCs de sujets sains féminins produisent plus d’IFNα en réponse à la stimulation du récepteur Toll-‐like 7 (TLR7) que les pDCs de sujets sains masculins. Les mécanismes impliqués dans cette différence n’ont été que partiellement identifiés. Des études précédentes ont révélé l’implication de la voie de signalisation du récepteur à l’œstrogène alpha (ERα). La voie de signalisation de TLR7 des pDCs s’organise autour de la famille des facteurs régulateurs interféron (IRFs). En particulier, IRF7 est connu pour son rôle essentiel dans l’induction de la transcription de l’IFNα. Des parallèles pathophysiologiques avec le lupus systémique erythémateux (SLE), une maladie autoimmune dont la prévalence est plus importante chez les femmes et associée à une activation de la voie de l’IFNα, nous ont conduit à étudier le rôle d’IRF5. En effet, des polymorphismes du gène IRF5, reliés à une expression d’IRF5 et une activation de la voie de l’IFNα accrues, sont associés au SLE. Nos résultats montrent que les pDCs de sujets sains féminins expriment plus d’IRF5 que les pDCs de sujets sains masculins, alors qu’il n’y a pas de différence d’expression d’IRF7. En outre, l’augmentation de l’expression d’IRF5, naturelle ou induite expérimentalement, est associée à une production plus forte d’IFNα. Finalement, nous montrons que, par rapport à des pDCs de souris sauvages, les pDCs de souris dont l’expression du gène ESR1 (codant pour ERα) est

invalidée spécifiquement dans les cellules dendritiques ou dans le compartiment hématopoïétique expriment significativement moins d’IRF5 et montrent par ailleurs un défaut de production d’IFNα en réponse à TLR7. Nous démontrons ainsi un mécanisme par lequel la plus forte expression d’IRF5 dans les pDCs chez les sujets sains féminins, sous le contrôle d’ERα, participe à leur production plus élevée d’IFNα en réponse à TLR7.

2. Comparaison de la voie de l’IFNα/TLR7 dans les pDCs et des niveaux d’activation immunitaire et

d’inflammation chez des patients co-‐infectés par le VIH-‐1 et le virus de l’hépatite C et des patients mono-‐ infectés par le VIH-‐1 sous traitement antirétroviral

La co-‐infection par le virus de l’hépatite C (VHC) est aujourd’hui l’une des principales causes de mortalité parmi les individus infectés par le VIH-‐1. Bien qu’il n’y ait pas de consensus, différentes études ont rapportés des niveaux accrus d’activation immunitaire et d’inflammation chez les individus co-‐infectés par le VIH-‐1 et le VHC par rapport aux individus mono-‐infectés par le VIH-‐1. L’inflammation est un des facteurs contribuant à la fibrose hépatique. Tant le VIH-‐1 que le VHC activent et altèrent la voie de signalisation des IFN de type I et de TLR7 associée aux pDCs. La contribution de ces diverses effets sur la réponse finale des pDCs reste à déterminer. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que l’activation immunitaire chronique plus élevée observée chez des individus co-‐ infectés par le VIH-‐1 et VHC pourrait être due à un dysfonctionnement de la voie de TLR7/IFN-‐I dans les pDCs. Nous n’avons pas observé de différence d’activation des pDCs et cellules T mais un plus fort épuisement de ces cellules chez les individus co-‐infectés à fibrose minime ou modéré que mono-‐infectés. À l’opposé, les patients co-‐infectés ont une plus d’inflammation. La voie de TLR7/IFN-‐I dans les pDCs reste plus activée chez les patients infectés par le VIH-‐1 sous traitement antirétroviral suppressif par rapport aux donneurs sains, comme déterminée par les niveaux d’IRF7 et de STAT1 phosphorylés. Enfin, l’analyse du transcriptome des pDCs révèle une signature de gènes stimulés par l’IFN plus forte chez les patients co-‐infectés que mono-‐infectés, qui est associée à la sévérité de l’infection. Les traitements anti-‐VHC sont aujourd’hui recommendés uniquement pour les patients (co-‐infectés ou mono-‐infectés par le VHC) dont le stade de fibrose est relevé. Nos données suggèrent que les patients co-‐infectés par le VIH-‐1 et le VHC, même à fibrose minime, pourraient bénéficier d’un traitement plus précoce.

Ce travail de thèse met donc en lumière des mécanismes associés à une plus grande production d’IFNα associée à une inflammation et/ou activation immunitaire délétères et identifie de nouvelles cibles thérapeutiques pour la moduler la voie de l’IFNα.

Preface

One can say that sex differences and co-‐infection with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-‐1) and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a surprising association and one would be right on many aspects. However, taking closer look shows otherwise.

Type I IFNs are fascinating. Discovered in 1957, more than half a century ago, for their antiviral properties, there is still plenty we do not know about them. They can be produced by virtually any cell type, but a rare population of immune cells, known as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), are recognized as the professional producers of type I IFNs. The identification of the various immunomodulatory functions of type I IFNs mark the cornerstone in our current understanding of their role in immune responses. Their signaling pathways, both upstream and downstream of type I IFN production, could almost be seen as labyrinths given the complexity and the multiple crossroads that can lead to common outcomes. Rather type I IFNs signaling in the current state of knowledge should be considered as a gamebook, in which the narrative branches along various paths, ultimately leading to multiple stories. Indeed, while type I IFNs are the subject of a steadily extensive research, which has uncovered multiple molecules, pathways and effects associated to type I IFNs, one major question remains to be answered. What guide, molecularly speaking, drives a given effect? Or are type I IFNs-‐driven immune responses inherently indistinctly induced?

Increasing evidences have highlighted a detrimental role of type I IFNs in various viral infections. Notably, pioneering work in HIV-‐1 infection has highlighted the dichotomous role of IFNα. HIV-‐1 infection remains a global concern. Although the development of effective antiretroviral treatment has tremendously improved the quality of life in the HIV-‐1 infected population, they continue to suffer from increased morbidity. In the past decades, the main cause of morbidity has shifted from AIDS-‐related events to non-‐AIDS related events including cardiovascular and liver diseases. Importantly, IFNα-‐driven immune activation and inflammation also contributes to the development of non-‐AIDS related events. In the absence of functional cure, strategies aimed at decreasing immune activation and inflammation and in particular strategies targeting IFNα signaling are relevant. Physiological and pathophysiological models can provide critical insights on how type I

Introduction

I.

Orchestration of the multifaceted functions of plasmacytoid dendritic

cells around IFNα production

1.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: “Professional producers of IFNα”

1.1. General characteristics of the plasmacytoid dendritic cells

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) were first referenced as an "enigmatic plasmacytoid T cells" in the paracortical area of reactive lymph nodes in 1958 by Lennert and Remmele. They were then partially characterized in the early 1990s as a rare subset of human peripheral blood leukocytes responsible for high level interferon (IFN)α production but were identified as a subset of dendritic cells (DC) only in the late 1990s. pDCs are relatively quiescent, as suggested by the low rate of incorporation of the DNA base analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and their turnover is rapid (about 2 weeks) 1,2. The combination of quiescence and short half-‐life of pDCs may be a contributing factor towards the small percentage they represent in the immune system 2. Indeed, pDCs circulate in the peripheral blood of adults and neonates where they represent about 0.1-‐0.5% of the human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)3. They reside primarily in the lymphoid organs (lymph nodes (LNs), tonsils, spleen, thymus, bone marrow, and Peyer’s patches) in the steady state, entering the LNs from the blood3. Only small numbers of pDCs are found in peripheral tissues in non-‐inflammatory conditions with the exception of kidneys, intestine and fetal liver3. pDCs are small (8-‐10μm) and display the morphology of secretory lymphocytes: they are round with a large cytoplasm, have an extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and do not exhibit dendrites as found on conventional DCs (cDCs) as shown in Figure 1 1

.

They undergo morphological changes upon stimulation with interleukin (IL)-‐3 and CD40L or with viral stimulation.pDCs are characterized by the absence of expression of the lineage markers of T lymphocytes (CD3), B lymphocytes (CD19), natural killer (NK) cells (CD56) and monocytes (CD14 and CD16). They express high levels of B cell marker B220/CD45RA, high levels of the alpha chain of the IL-‐3 receptor (CD123) and low levels of major histocompatibility (MHC) class II molecules. pDCs also express CD4 and several adhesion molecules including CD31, CD43, CD44, CD47, CD62L, CD99, and CD162 (also known as SELPLG, CLA) that may play an important role in the tethering and rolling of pDCs on endothelial cell. Homologs of human pDCs have been identified in mice 4. pDCs can be identified thanks to the expression of specific lineage markers such as blood dendritic cell antigen

Figure 1 : pDC morphology

Transmission electron microscopy of pDCs shows a nuclei with marginal heterochromatin and a cytoplasm containing well-‐developed rough endoplasmic reticulum, small Golgi apparatus, and many mitochondria. From [1]