Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

[DEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

COPING

WITH

CHILE'S

EXTERNAL

VULNERABILITY:

A

FINANCIAL

PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.Caballero

WORKING

PAPER

01-23

MAY

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection at

OFTECHNOLOGY

AUGl

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Econonnics

Working

Paper

Series

COPING

WITH

CHILE'S

EXTERNAL

VULNERABILITY:

A

FINANCIAL

PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.Caballero

WORKING

PAPER

01-23

MAY

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from the

Social

Science Research

Network

Paper

Collection

at

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Departnnent

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

COPING

WITH

CHILE'S

EXTERNAL

VULNERABILITY:

A

FINANCIAL

PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.Caballero

WORKING

PAPER

01-23

MAY

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network Paper

Collection at

http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.taf

?abstract_id=XXXXXX

Coping

with

Chile's

External

Vulnerability:

A

Financial

Problem

05/11/2001

Ricardo

J.

Caballero'

Abstract

With

traditionaldomestic

imbalances

longunder

control, theChilean

business cyclehas

been,

and

most

likely will continue to be, primarily triggeredby

external shocks.Most

imporiantly, Chile's external vulnerability isprimarily

a

financialproblem.

A

decline inthe

Chilean

terms-of-trade,for example,

is associated toa

decline in realGDP

that ismany

times larger thanone

would

predict in thepresence of

perfect financial markets.The

financial natureof

this excessive sensitivityhas

two

centraldimensions: a sharp

contraction in Chile'saccess to internationalfinancial

markets

when

itneeds

it themost;and

an

inefficient reallocationof

this scarce access acrossborrowers during

externalcrises. In this

paper

I characterize this financialmechanism

and

argue

that Chile'saggregate

volatilitycan

be

reduced

significantlyby

fostering the private sector'sdevelopment

of

financial instruments that are contingenton

Chile'smain

externalshocks.

As

a

first step, the CentralBank

or

IFIsshould

issuea

benchmark

instrumentcontingent

on

theseshocks.'

MIT

and

NBER.

e-mail: caball@mit.edu; http://web.mit.edu/caball/www.

Prepared

for theBanco

Central de Chile. Iam

very grateful toAdam

Ashcraft,Marco

Morales

and

especiallyClaudio

Raddatz

for excellent research assistance,and

toHerman

Bennett

forI.

Introduction

and Overview

With

traditionaldomestic imbalances

longunder

control, the Chilean business cycle hasbeen,

and

most

likely will continue to be, primarily triggeredby

external shocks.Most

importantly, Chile's external vulnerability is primarily a financial problem.

A

decline in theChilean terms-of-trade, for

example,

is associated to a decline in realGDP

that ismany

times larger than

one

would

predict in thepresence

of perfect financial markets.The

financial nature

of

this excessive sensitivity hastwo

central dimensions: a sharpcontraction in Chile's access to international financial

markets

when

itneeds

it themost;

and

an inefficient reallocationof

this scarce accessacrossborrowers

during external crises.I argue that Chile's

aggregate

volatilitycan be

reduced

significantlyby

fostering theprivate sector's

development of

financial instruments that are contingenton

themain

externalshocks

facedby

Chile.As

a first step, the CentralBank

or IFIscould

issue abenchmark

instrument contingenton

these shocks.The

essence ofthemechanism

through which

externalshocks

affect the Chileaneconomy

can

be characterized as follows: First, there is a deteriorationof

terms-of-trade that raisesthe

need

for external resources if the realeconomy

is to continue unaffected, but thistriggers exactly the opposite reaction

from

international financiers,who

pullback

capital inflows. Alternatively, ashock

directly to the financialmarkets

facedby

emerging

economies

reduces capital inflows immediately.Second,

once

external financialmarkets

fail to

accommodate

theneeds

ofdomestic

firmsand

households, these agents turn todomestic

financial markets,and

tocommercial banks

in particular. Again, this increase indemand

is notmatched by

an increase in supply asbanks

—

particularly resident foreigninstitutions

-

tightendomestic

credit, opting instead to increase their net foreign asset positions.The

costsof

thismechanism

are large.Widespread

financial constraints are binding duringthe crisis,

when

major

forced adjustments are needed.The

sharp decline indomestic

assetprices,

and corresponding

rise inexpected

returns, is drivenby

theextreme

scarcity infinancial resources

and

their high opportunity cost.Even

the praised rise inFDI

thatoccurred

during themost

recent crisis is asymptom

of

these fire sales ofdomestic

firms.The

fact that this investment takes theform

of

control-purchases rather than portfolio orcredit flows simply reflects

some

of the underlyingproblems

that limit Chile's integration to international financial markets:weak

corporategovernance and

other "transparency"standards. Finally, the costs

do

notend

with the crisis, as financially distressed firms are illequipped

tomount

aspeedy

recovery.The

latter oftencomes

not only with the costs ofaslow recovery

inemployment

and

activity, but also with aslowdown

in the processof

creative destructionand

productivitygrowth.

In the U.S., the lattermay

account

forabout

30%

of the costs ofan average

recession (see Caballeroand

Hammour,

1998),which

isprobably

a very optimisticlower

bound

fortheChileaneconomy."

^ This decline in collateral is probably one ofthe reason why, paradoxically, the sharp reductions in

domestic rates that took place in Chile during 1999

came

with a reallocation of domestic loans towardlargefirms and awayirom small firms, rather than the other

way

around. See Caballero (1999) and theMoreover,

this type of financial crisis has different real effects across firm size.On

one

end, large firms are directly affected

by

externalshocks

butcan

substitutemost

of their financialneeds

domestically.They

are affected primarilyby

demand

factors.On

the other, smalland

medium

sized firms (henceforth,PYMES)

arecrowded

outand

are severelyconstrained

on

the financial side.Together

withconsumers,

they are the residual claimantsofthe external-domestic financialcrunch.

This diagnosis points in the direction of a structural cure

based

on

two

building blocks.The

firstone

deals with the institutions required to foster Chile's integration to international financialmarkets

and

thedevelopment

ofdomestic

financial markets.The

second

one,most

important in the long transition createdby

the unavoidableslow

natureof

theabove

process, is to design an appropriate international liquiditymanagement

strategy.The

lattermust

beunderstood

interms

broader

than just themanagement

of

international reservesby

the central bank,and

include thedevelopment

of

financialinstrumentsthat facilitate the delegation ofthis taskto the private sector.

It is this

second

setof

cures that I focuson

in this paper, with an effort to formulatesolutions that

maximize

the role playedby

the private sector in achieving them.' Thissector has large

comparative advantages

in thedevelopment

of financial instruments,perhaps

with a little"nudge"

from

the CentralBank

and

international institutions.Chief

among

these, is the creation of abenchmark

"bond"

that ismade

contingenton

themain

externalshocks

facedby

Chile. This instrumentshould

facilitate the private sector's pricingand

creationof

similarand

derivativecontingent financial instruments.Section II describes the essence

of

the externalshocks

and

the financialmechanism

atwork.

Section III follows with a discussion of theimpact

of

thismechanism

on

the realside of the

economy

and

the differenteconomic

agents. SectionIV

sketches a policyproposal,

and

SectionV

concludes.SeeCaballero (1999)for a discussion ofthe structural reforms aimed at improving integration andthe

development offinancial markets.

More

importantly, Chile is in the process of enacting a major capitalmarkets reform, including the removal of a series of obstacles to its full integration to international

II.

The Shock

and

the Financial

System

In this section I illustrate the

mechanism

though

which

externalshocks

affect the Chileaneconomy.

A

deterioration in a country's terms-of-trade should lead to an increase ininternational

borrowing,

but inemerging

economies

thisshock

has typically led to capitaloutflows.

A

shock

directly to financialmarkets can

generate thesame

result: anextreme

scarcity of financial resources for the

economy.

As

agents are turnedaway

from

foreign lenders, theyturn to residentbanks

tomake

up

the difference. This increase indemand

isnot

met by

an increase in supply,however,

asbanks

(likeeveryone

else) readjust theirportfolios

toward

foreign assets.I organize

my

discussionof

the roleplayed

by

each of

these ingredientsaround

demand

and

supply factors affecting thedomestic banking system

-

thebackbone

of the Chileanfinancial system.

An

overview

of the Chilean financial institutions is presented inBox

1.Moreover,

I focuson

themost

recent cyclical episode, as thechanging

natureof

theChilean financial

system

makes

older data lessrelevant.//.1

The

External

Shock

and

itsImpact

on Domestic

Financial

Needs

The

triggerof

themechanism

is illustrated in Figure 1. Panel (a)shows

the pathof

Chile'sterms-of-trade

and

the spread paidby

prime

Chilean instrumentsover

the equivalent U.S.Treasury

instrument. It is apparent that Chilewas

severely affectedby both

at theend

ofthe 1990s. Panel (b) offers a bettermetric to

gauge

themagnitude of

these shocks.Taking

the quantities

from

the1996

currentaccount

as representativeof

those thatwould

have

occurred

in theeconomy

absentany

real adjustment, it translatesthem

into the dollarlosses associated to the deterioration in terms-of-trade

and

interest rates. Starting in 1998,Box

1:

The

Chilean

Banking

Sector

Banks

are an important source of financingfor Chilean firms.

The

composition of financing (table A.l) is similar to that ofadvanced European economies. Unlike the

latter, and

much

like the US, the maturitystructure of Chilean bank loans is

more

concentrated on the short end:

57%

of totalloans, and

60%

ofcommercial loans, have a maturity of less than 1 year." Insummary,

Chilean banks look like Europeans in termsof their relative importance but like

US

banks in theirfocus onshort maturities.^

Relative

importance:

Loans

versus

other instruments.

TableA.l:

The

relativeimportanceofbank

loans. Sourceof financing Loans Equity Bonds Stock Flows

43%

51%

54%

33%

3%

16%

Note: Participations built using the stocks at December

2000. Flows were computed as the difference in stocks

betweenDecember 1999andDecember 2000except forthe

flow ofnew equity, which was built using information on

equityplacement duringthe period.

Composition

of

Loans.

Besides being relatively important

compared

to markets as sources of funds, Chilean

banks concentrate most of their activity on

firms.

Commercial

loans represent around60%

of total bank loans (see Table A.2).Adding

trade loans, about70%

oftotalbank

credit supply isdirectedtofirms.

'' Computed using the stock

of loans in December 1999. Source Stiperintendenda de Bancos e Institiidoties Fitianderas.

^ In Germany, for example, more that 70% of the commercialloansarelongterm. In contrast,in the

US

short term loans account for about 60% of non-residentialloans.TableA.2: Compositionofloansbyuse. Typeof loan Fraction oftotalloans

Commercial

60%

Residential

15%

Consumption

10%

Trade

10%

Other

5%

Source: Superintendencia deBancose Instituciones Financieras.

Composition

of

commercial

loans

by

firm

size.Chilean banks concentrate their lending

activity on large firms, at least

when

proxied by the average size of loans.

Around

65%

of commercial loans werewritten for amounts above

US$

1.The

relative importance ofdifferentloan sizes

is summarized inTableA.3.

TableA.3:

The

relative importanceof different loansizes.Loan size Fraction ofcommercial

loans

Large

64%

Medium

14%

Micro

22%

Note: Large:allloansabove 50,000LIF(around US$ 14millions(endof1999dollars));Medium: loans between 10,000 and50,000UF(US$ 280,000and US$ 1,400,000); Micro: loans below 10,000 UF (US$ 280,000).

Source: Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones

Financieras.

Banks

versus other

financialinstitutions.

Banks

in Chile are importantwhen

compared

with other financialinstitutions as well. Table A.4 compares

the total assets ofbanks, pension funds,

and insurance companies*. Bank's total

assets represent the

60%

of the grandTotal assetsisthesumoffinancial andfixedassets.

Fixedassets are notincludedforinsurance

companies.Nevertheless, fixedassetsrepresenta

total.

TableA.4:

Banks

andotherfinancialinstitutions. Relative asset level

Bank

s60%

Pensio n Funds30%

Insurance companie s10%

Note: Ratios basedon thestock ofassetsat December 2000.

Sources: Superintendencia deBancose Instituciones Financieras,Superintendenciade Valores y Seguros.

Domestic

and

Foreign banks.

Banks

owned

by internationalconglomerates represent a significant

share of credit supply in Chile. Table A.5

shows

that loans by foreign banksrepresented around

40%

oftotal loans. It is important tonotethatChileanBanking

Law

does not recognize subsidiaries offoreign banks as part of their

main

headquarter, therefore in practice the distinction between domestic and foreign

banks is just a matter of ownership.

Reflecting the withdrawal

from

domestic loans by foreign banks described in themain

text, the bottom ofthe tableshows

that difference in the portfolio

composition of domestic and foreign

loans attheendof 1999.

TableA.5: Domestic

and

ForeignBanks

Domestic Foreig n Relativeimportance

(%

totalloans)58%

42%

Portfoliocomposition Loans80%

67%

Securities11%

14%

Foreignassets6%

15%

Reserves3%

4%

Note: Ratios based onDecember1999values.

Source:SuperintendenciadeBancose Instituciones

Figure 1: ExternalShocks

(a)TenreofTradeandSoveragn Spread (b)TermsolTrade andInterestRateellecl (fixed quantities)

Efefe^

[SI S3

Notes: Preliminary datausedfar1999and2000. Tlieyearly Figure for2000 wascomputedmultiplying the3 quarters cumulative valueby4/3. (a) Tenns-of-trade isthe ratioofexports price index and import price indexcomputed by the Central Bank. The

sovereignspreadwasestimatedasthespreadofENERSlS-ENDESAcorporate bonds.Tliespreaddata for1996wasestimatedb\'the

authorusinginformationfromtheCentralBank ofChile, (d)TJietenns-of-tradeeffectwas computedasthe differencebenveen the

actual terms-of-tradeandthetenns-of-tradeat1996quantities.Tlieinterest rale effectwascomputedinsimilarfashion Source:BancoCentral deChile.

How

should Chilehave

reacted to this sharp decline in nationalincome,

absentany

significant financial friction (aside

from

thetemporary

increase in the spread)?Theory

suggests the

answer

depends

on

the persistenceof

the terms-of-trade shock: likeindividuals, countries should largely

smooth

the effectof temporary

income

shocks

butmore

or lessaccommodate

the effectof permanent

income

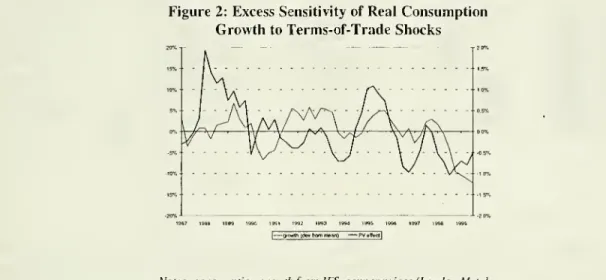

shocks. Figure 2 hints theanswer.

The

thin line depicts the pathof

actualconsumption growth,

while the thick lineillustrates the hypothetical path of Chile's

consumption

growth

if itwere

perfectly integrated to international financialmarkets and

terms-of-trade the onlysource ofshocks.^There

aretwo

interesting features in the figure. First, there is a very high correlationbetween

Chile's business cycleand

shocks

to its terms-of-trade.Second,

and

more

importantly for the

argument

in this paper, the actual response of theeconomy

is beingmeasured

on

the left axis while that ofthe hypothetical is beingmeasured

on

theright axis.Since the scale in the

former

is ten times larger than thatof

the latter, it is apparent thatthe

economy

over-reacts to theseshocks

by

a significant margin. In practiceshocks

to theterms-of-trade are simply too transitory, especially

when

they are drivenby

demand

as inthe recent crisis, to justify a large

response

of the real sideof

theeconomy.^

The

income

^ Consumption growth is very similarto

GDP

growth for this comparison. Adding the income effect ofinterest rate shocks would not change things too

much

as these were very short-lived. I neglect thepresence of substitution effects because there is no evidence of a consumption overshooting once

effect that is

measured

in panel (b) of Figure 1 should in principle, but itdoes

not inpractice, translate almost entirelyin increased

borrowing

from

abroad.Figure2: ExcessSensitivity ofReal Consumption

Growth

toTerms-of-TradeShociisNotes:consumptiongrmvtfifromIFS.copperprices(London Metal

Exchange) fromDatastream,copperexportsfromMin.de Hacienda.

Returning

to the recent crisis, panel (a)of

Figure 3 illustrates that international financialmarkets

did notaccommodate

this increase indemand

for foreign resources as capitalflows actually declinedrapidly

over

the period. Panel (b)documents

that while the centralbank

offset part of this declineby

injectingback

some

of its international reserves, itclearly

was

not nearlyenough

to offsetboth

the decline in capital inflowsand

the rise inexternalneeds.

8

The

price ofcopper has trends and cycles at different frequencies, some of which are persistent (seeMarshall and Silva, 1998). But there seems tobe no doubt that the sharp decline in the price ofcopper during the current crisiswas mostlythe result ofa transitory

demand

shock brought about by the Asiancrisis. As the latter economies have begun recovering, so has the price of copper. I would argue that

conditional on the information that the current shock was a transitory

demand

shock, the univariate process used to estimate the present value impact of the decline in the price of copper in Figure 2, overestimates the extent ofthis decline. The lower decline in future prices is consistent with this view.The

variance of the spot price is 6 times the variance of 15-months-ahead future prices. Moreover, the expectations computed from theAR

process track reasonably well the expectations implicit in futuremarkets but for the very end ofthe sample, when liquidity premia considerations

may

havecome

into play.Figure3: CapitalFlowsandReserves

B,0O0

(a)Capital^tcouit exceptReserves

6000 [ 4000 '- "" 1000 r " hi.-- J (b)Balance otPayrrerrts r

—

TT-im

1999 StXMSource:BancoCentraldeChile

How

severewas

themismatch

between

the increase in Chileandemand

for financialresources

and

thechange

in their supplyby

the internationalcommunity?

One

answer

appears in panel (a) of Figure 4,

which

graphs the actual currentaccount

(the light bars)and

the currentaccount

with quantities fixed at1996

levels (thedark

bars). This exercise highlights that at itsworst

time, the actual currentaccount

deficitwas

almost$4

billionsmaller than

what

one

would

have

predicted using only the actualchange

interms-of-trade.

Moreover,

this dollar adjustment underestimates the quantity adjustment behind it,asthe deterioration

of

terms-of-trade typicallyworsens

the currentaccount

deficit forany

path ofquantities.

The

importance

ofthis price-correctioncan be

seen in panel (b),which

graphs the actual current

account

(again with light bars),and

the currentaccount

fixed at1996

prices(dark bars). Clearly, the lattershows

a significantly larger adjustment than theformer.

Figure4:

The

Current Account(a)CurertAxoirtandCuralPccoirtat1996qiBitrties (b)CurrerlAccout(actualanJin1996prices)

I

i

I1

I1

^

[oCuTg^AmmBCAte, al96l>a;<ha\

[CimrtAi^irrtnUSSIC^rcrtAg(mmUSSMI|

Notes:(a)Thecurrentaccountal1996quantitieseachyear was computedbymultiplyingthe1996quantitiesbyeachyear'sprices.

Thelatterare theprice ofexports,imports,andspreadofENERSISbonds.Theothercomponentsofthecurrentaccount werekeepi atcurrentvalues, (b)Thecurrentaccountin1996priceswascomputedfi-xingtheprices while usingeachyear'squantities.Source: BancoCentral deChile.

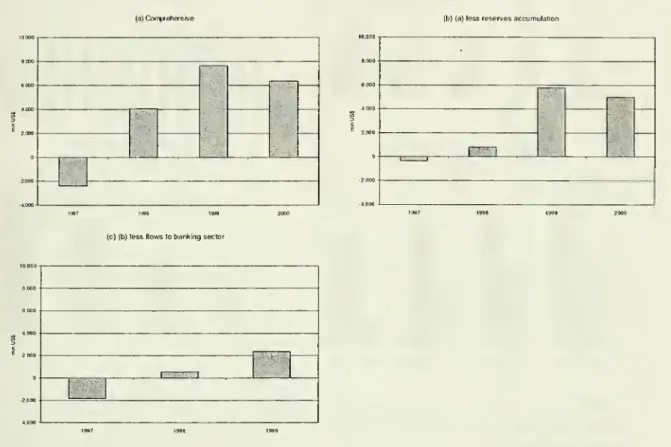

Figure 5 reinforces the

mismatch

conclusionby

reporting increasingly conservativedescribes the path

of

thechange

indemand

for resourcesstemming from

the decline interms-of-trade, increase in spreads,

and

the decline in capital inflows. Panel (b) subtractsfrom

capital inflowsthe reduction in reserveaccumulation by

the central bank, while panel(c) subtracts further the decline in capital inflows to the

banking

sector.During

1999, thisincrease in financial

needs

rangesfrom

justunder $8

biUionon

the highend

toabout

$2.5billion

on

thelow

end. Regardlessof

theconcept

used, themismatch

is large, creating a potentially large surge in thedemand

for resourcesfrom

thedomestic

financial system.The

differencebetween

panel (b)and

(c), as well as the next sectionmore

extensively,show

that the latter sector not onlydoes

notaccommodate

this increase indemand,

butworsen

the financial stress.Figure5:

The

IncreaseinPotentialFinancialNeeds(a)Conpfehensrve (b) (a)lessreservesaccumulation

:

\'V.V^\

(c) (b)lessHowstobankingsector

;•,..

Notes: Theincreaseinpotentialneedscorrespondtothesum oftheterms-of-tradeeffect,the interestrateeffect,andthedecline in capital inflows. Both the lenns-of-trade,andthe interestrate effectsaremeasuredat 1996quantities. Thedecline in capitalflows

correspondsto thedifference ofthecapitalaccountexceptreseri'eswithrespecttoits1996value.Relativeto (a),panel(b)subtracts

fromcapitalflowsthenetchangein CentralBankreser\'es.Panel(c)subtractstopanel(b) the netincrease inflowstothebanking

sector. Source:BancoCentraldeChile

To

conclude

this section. Figure6

shows

that it is not only the external sector that putspressure

on

thedemand

for resourcesfrom

resident banks. Panel (a)and

(b) carries therelatively

"good"

news.

The

former

panelshows

that issues ofnew

equityand

corporatebonds

do

not decline very sharply, although they hide the fact that the required returnon

these instruments rose significantly.

The

latter panel illustrates that while theAPPs

increased their allocation of funds to foreign assets during the period, this portfolio shift

occurred mostly

against public instruments.However,

this declineprobably

translated intoa large

placement

ofpublicbonds

on

some

othermarket

or institution thatcompetes

withthe private sector, like

banks

(see the discussion below). Panel (c),on

the other hand,indicates that retained earnings, a significant source of investment financing to Chilean

firms declined significantly

over

the period, puttingmore

pressureon

thedemand

forfinancial resources.' Finally, panel (d) illustrates that

workers

didnot helpaccommodating

the financialbottleneck either, asthe laborsharerose steadily

throughout

the period.Figure6: OtherPressuresonChileanFirms

(a)Changeinthe slock of corporatedebtandnewequity (b)AFPholdings as fraction ofGDP

-S1000 J;

1

i S 1 5»,.-eV

^

tffl+ii'Tl

i-i

III

199T

|DN»i* gqjty emiiBOriiBChangcinouBlandngcorporaled

(c)RetainedEarnings

IpPiiMicBFinancialQCprnpanigsQFonriCFi|

(d)Labor share

'

'-).-^2^;^^

iDFVjw/OperattCTi Stech/Total

|

Notes:(a)Source:BolsadeComerciode SantiagoandSuperintendenciade Valores y Seguros. Equity emissions arevaluedat issue price, anddeflated using CPl The stock ofcorporate debt outstanding was also deflated according to CPI. The values were

transformedintodollarsusingthenominalexchangerateinthebase monthoftheCPlindex:December1998(432pesos perdollar), (b)Source: Superintendencia deAFP. Thevalues are expressed as fraction oftheannual

GDP

oftherespective year,(c)Thedataonretainedearnings isfrom Bolsa de Comerciode Santiago (Santiago Stock Exchange) andcorrespond to the stocks of retained earning reportedinthebalance sheets ofallthesocietiestradedinthatexchange.Itexcludesinvestmentsocieties,pensionfunds,and insurance companies.The marginal valuewascomputedasthedifference inthestockattandt-1properly deflated, (d) Source: BancoCentral deChile.

The

bottom

line of this section is clear: during external crunches, Turnsneed

substantial additional financialresourcesfrom

resident banks.11.2

The

(Supply)

Response

by

Resident

Banks

'Before

thecrises, in 1996,thestockof retained earnings represented a

20%

oftotalassets for themedianfirm. Similarly, the difference between profits and dividendpayments, a measure ofthe flow of retained

earnings, represented arounda

50%

oftotal capitalexpendituresforthemedian firmin 1996.How

did residentbanks respond

to increaseddemand?

Panel (a) in Figure 7shows

thatfarfrom accommodating

this increase,domestic

loangrowth

actuallyslowed

down

sharplyduring the late 90s,

even

as deposits keptgrowing.

This tightening can also be seen inprices in panel (b)

through

the sharp rise in the loan-deposit spread during the earlyphase

of the recent crisis.

Moreover,

while spreads started to fallby

1999, therewas

a strongsubstitution

toward prime

firms thatmakes

it difficult to interpret this decline as aloosening incredit standards (see below).

Figure 7:

The

CreditCrunch

(a)Loans andDeposits:BankingSystem (b)InterestRate Spreads {Annual%)

s s s s s s

t i i

Hi'

iS S 8 8 i i S i

2r -• 5 3

Notes:(a)Loansincludes commercial, consumption, trade,andresidential(housing)loans.Itdoesnot includeresidentialloans with equityemission ("letrasde credito").Deposit includes sightdepositsandtimedeposits. The values were expressedin dollarsof

December 1998 multiplying the Figures in pesos ofDecember 98 by the average nominal exchange rale in that month (472

pesos/dollar),(b)}Theunderlying30-dayinterestrates are nominalwhilethe90-365arereal(toafirst order, this distinctionshould

not matter forthe spreads).

Sources:BancoCentral,andSuperintendenciadeValores y Seguros.

The

main

substitutes for loans in banks' portfolios arepubbc

debtand

external assets.Panel (a) in Figure 8

shows

it is the latter thatwas

behind

theslowdown

in loans.The

central

bank

policy of fighting capitaloutflows

seems

tohave been only

temporarilysuccessful(see the reversal during the last quarter

of 1998)

indoing

so. Instead, the rise ininterest rates during the

Russian

phase of

the crisisseems

tohave succeeded mostly

inslowing

down

the decline in banks' investment in public instrument,and encouraged

substitutionaway

from

private lending.Banks,

rather thansmooth

the lossof

externalfunding, exacerbated it

by becoming

partof

the capital outflows. In fact, while panel (b)illustrates that the

banking

sector alsoexperienced

a large capitaloutflow

during thisepisode, panel (c) reveals that

much

of

the netoutflow

was

notdue

to a decline in theirinternational credit lines or inflows, but rather

due

to anoutflow

toward

foreign depositsand

securities.Figure8: CapitalOutflowsbythe Banking System (a)InvestmenlinDomeslicandExternalAssetsBankingSystem

(b)Netcaprta) inftovfi tobankingsedor

*<f** * *"'^»* =?-'^ -^^ ^.<^*c»f»^*(*<*'',<'4># q^

##

(P#/V^

s^V^'^'/V*^**c,'*'y/y^":^=,<*'^'^/^j**'j^S'*'-^'^^"y^ (c)CompositbnofForeignAssets BankingSystemE -Foreigo secunfrca[

Notes:(a)Domesticassetsinclude CentralBanksecuritieswithsecondarymarketandintermediatedsecurities. Externalassetsare thesum of depositsabroadandforeignsecurities. Depositsabroadconsistmainlyon sightdeposits of Chilean banksonforeign banks. Foreignsecuritiesconsistmainlyinforeign bonds,(b) Tiiespreadreported isthe differencebetween the90-365 daysloan interest rate (real)andthe interest rateofoneofthecentralbankbonds.- thePRBCwithmaturityin90days.

Sources:BancoCentralandSuperintendencia de Bancos.

While most

residentbanks

exhibited this pattern tosome

degree, it is resident foreignbanks

thattook

the leadand

made

themost

pronounced

portfolio shifttowards

foreignassets. This is apparent in panels (a)

and

(b) in Figure 9,which

present the investment indomestic

and

foreign assets across foreignand domestic

(private) banks, respectively.While

allbanks

increased their positions in foreign assets, foreign banks' trend ismore

pronounced.

Moreover, domestic banks

"financed" a larger fraction of their portfolio shiftby

reducing other investments ratherthan loans. Thisconclusion isconfirmed

by

panel (c),which

shows

the paths of the loans to deposit ratios for foreign (dashes)and domestic

(solid) banks."'

"*

This figureexcludes two banks(BHIF andSantiago)that changed from domestic toforeign ownership

during theperiod. The changein statistical classification took place in

November

1998 for Banco BHIF,and in July 1999 for Banco de Santiago. In the case ofBanco de Santiago, the takeover operation took

place in

May

1999 byBancoSantander(the largest foreign bankin Chile). Assumingthat thetwo banks were going tomerge, theChilean banks regulatoryagency (Superintendencia de Bancos) asked Bancode Santiago to reduce its market presence (the two banks had a joint presence equivalent to29%

of totalloans). The banks finally decided not to merge and therefore their joint market presence have remained

unaltered so far. Most likely the confusion created by the potential participation limits did not help the

creditcrunch Chile experiencedatthetime.

Figure 9:

Comparing

Foreignand DomesticBank

Behavior(a)InvestmentinDomesticandExternalAssets' ForeignBanks (b)InvestmentinDomestK:and ExiemalAssets:DomestcBanks

i.sc

I

Ejteiral • -- DotTiBBti:|

(c)Loans over Deposits domestic andforeignbankse Santiago xceptBHIFand ... ' " •--'-N.s^ •• "-^ -.^

___._/

—

\

: \._ I i I i 1 i ^ p OnnMsiic Ftmt(tfi|Notes: Domestic banks do not include Banco del Estado. (a), (b) Domestic assets include Central Bank securities with

secondarymarketandintermediatedsecurities.Externalassets arethesumofdepositsabroad andforeignsecurities.

All Figuresare expressed in dollars by multiplying the series in constantpesos ofDecember98 by the average nominal

exchangerateofthatmonth(472pesos/dollar), (c)Ratiosof Loans overdepositshave been normalizedtooneinMarch1996.

Deposits includesightandtimedeposits. Loansincludecommercial, consumption,trade, andresidential(housing)loans. The

nvobanksthatchangedstatistical classificationfromdomestictoforeignduringthe lastyears ---BancoBHIFch inNovember

1998and Bancode SantiagoinJidy1999--were excludedfromthesample. Theinformationusedtoseparate thesetwobanks

isfromtheBolsa de ValoresdeSantiago (Santiago Stock Exchange).

The

question ariseswhether

it is not the nationality but other factors (e.g., riskcharacteristics)

of

thebanks

thatdetermined

the differential response.While

this iscertainly a

theme

tobe explored

more

thoroughly, theevidence

inFigure 10 suggests thatthis is not the case. Panel (a)

shows

that foreignbanks

did not experience a rise in net foreigncurrency

liabilities thatcould account

for additional hedging.When

compared

withdomestic

banks, they did not experience a significantly sharper rise innon-performing

loans as is indicated

by

panel (b), orwere

affectedby

a tighter capital-adequacy constraintin panel (c).

Figure 10: RiskCharacteristics ofForeignand Domestic

Banks

(a)ForeignCurrency Assels andLiabilities:ForeignBanks (b)Nonperforming toans aspercentageoltotalloans:domestic and foreignbanks \

»n

mi

1—

^B

^9

SSi^3

6% -'—

^M

i

H!

^n

i:H| jHj 07\|h

ilH

—

'B

—

nn

lODomeslgBForcigr (c)Basle IndicatorE -OcnvstEPtHalc 8anlu

Notes: (a)Foreign assetsinclude foreignloans, depositsabroadandforeignsecurities. Foreignliabilitiesincludefttndsborrowed

fromabroadanddepositsinforeign currency, (b)

ROE

isthe ratiooftotal profitsovercapitalandreserves(aspercentage),(c)Basleindexcorrespondsto thecapitaladequacyratio.DomesticprivatebanksdonotincludeBancodelEstado. Source:Superintendencia deBancose InstitucionesFinancieras.

Foreign

banks

usually playmany

useful roles inemerging

economies

but theydo

notseem

to

be

helping tosmooth

externalshocks

(at least in themost

recent crisis). It is probablythe case that these banks' credit

and

risk strategies are being dictatedfrom

abroad,and

there is

no

particular reason to expectthem

tobehave

too differentlyfrom

other foreign investors during these times.In

summary,

during1999

-perhaps

theworst

full year during the crisis—banks

seem

tohave reduced

loangrowth

by about

$2

billion dollars," while the increase in financialneeds

by

thenon-banking

private sector estimated in Section II.1was

about $2.5 billions(see figure 5c).

Although

there aremany

general equilibriumissues ignored in these simplecalculations, it is

probably

not too far-fetched toadd

them

up and conclude

that thefinancial

crunch

was

extremely large,perhaps around

$4.5 billion dollars (about6%

ofGDP)

inthat single year."

A

numberclose totwobillion dollarsisobtained fromthedifferencebetween theflow of loansduring 1999 (computedasthechangein thestock ofloansbetween December 1999 andDecember 1998) andthe

flow of loans in 1996 (computedin similarmanner).

III.

The

Costs

The

impact of the financialcrunch

on

theeconomy

is correspondingly large. Itsignificantly

worsens most

aggregate indicators,and

it particularly hurts smalland

medium

size firms.///.1

The

Aggregates

Figure 2 already

summarized

the first-orderimpact

of

the financialmechanism,

with adomestic

business cycle that ismany

timesmore

volatile than itshould

be with perfectcapital markets. This "excess volatility"

was

particularlypronounced

in the recentslowdown,

as isillustratedby

panel (a) in Figure 1 1.The

paths ofnationalincome

(solid)and domestic

demand

(dashes) not onlyappear

tomove

together, but the latter adjustsmore

than the former, implying that the largely transitory terms-of-tradeshock

is notbeing

smoothed

over

time. Panel (b) illustrates the sharp rise in theunemployment

ratethat

followed

and

that has yet tobe

undone

(asof

May,

2001).Figure 11: Chilean Output,

Demand,

andUnemployment

(a)Nationalincome and DomesticDemand (b)Unemptoymentrate

Notes: (a)Seriesare seasonally adjustedandannualized. Source:BancoCentraldeChile, (b)Source: INE.

Aside

from

the directnegativeimpact

of

theslowdown

and any

additional uncertainty thatmay

have been

createdby

the untimely discussionof

anew

laborcode,

the buildup

inunemployment

and

its persistencecan

be

linked totwo

additional aspectsof

the financialmechanism

described above. First, in the presenceof

an external financial constraint thereal

exchange

rateneeds

a largeradjustment

forany

given decline in terms-of-trade.'^As

a result

of

this, a big share of theadjustment

fallson

the labor-intensive non-tradablesector, asillustrated in panel (a) of Figure 12.

Second, going

beyond

the crisisand

into therecovery, the lack of financial resources

hampers

job

creation, aphenomenon

that isparticularly acute in the

PYMES

(see below). Panel (b) suggests that thiscould

beimportant

by

illustrating that investment (solid line) suffered adeeper

and

more

prolonged

'"

The larger real exchange rate adjustment corresponds to the dual of the financial constraint. See

Caballeroand Krishnamurthy(forthcoming).

recession than the rest of

domestic

aggregatedemand

(dashed

line).While

notshown

here, the costs of financial constraints during the

recovery

can

extend

beyond

theunemployment

cost as they also depressone

of themain

engines of productivitygrowth:

the restructuring process. If the U.S. isany

indication of the costs associated to thisslowdown

in restructuring -- possibly a very optimisticlower

bound

for the Chilean costs—

thismechanism

may

add

a significant productivityloss thatamounts

toover

30%

of

theemployment

cost ofthe recession.''Figure12: Transmissionof theShock toOtherSectors

(a)GDPtradeableandnon-tradeablesectors (b)Evolution o(domesticdemand ' ---. . ,', -

-'

^

/~ ^^\

25000^

—

^

^

^

—

-^^---^

™» i ,»»> ^ ,0000 SOOO |- -HEST^—FBkF]Notes:(a)Preliminary dala usedfor year 2000. Series are seasonally adjustedandwere normalizedtoMarch 1996=1. Tradeable sector includes agriculture, fishing, mining, and manufacturing. Non-tradeable sector includes electricity, gas and water, construction, trade, transport and telecommunications, and otherservices, (b) Seriesare seasonally adjusted, andannualized. Source:BancoCentral deChile.

Given

the increase in spreads as the external constraint tightens, arbitrage dictates that thestock

market

must

also decline sharply in order to offer significant excess returns to thosewilling to

buy

these assetswhen

most

foreign investors are not. Panel (a)of

Figure 13illustrates this v-pattem. Panel (b) illustrates that foreign direct investment

(FDI)

increasedby

almost $4.5 billion during 1999,and

created abottom

to the fire saleof domestic

assets.

While

FDI

is very useful since it provides external resourceswhen

they aremost

scarce, its presence during the crisis reflects the severe costs

of

the external financialconstraint as valuable assets are sold at

heavy

discounts.13

SeeCaballeroand

Hammour

(1998).Figure 13: Fire Sales

(a)ValueotChileanslocks (index) (b)Foreign DirectInveslmenI(FDt)

1

^fe

&fep

.,

Notes:(a)IGPAisthegeneral stock price index oftheSantiago StockExchange.Sources:Bloombergand BancoCentralde Chile (b)Onlyconsiderstheflows ofFDI fromabroad(excludestheflowsofFDI associated with investmentsmadeby Chileanresidentsin foreigncountries).Source:BancoCentraldeChile.

111.2

The Asymmetries

The

realconsequences

of the externalshocks

and

the financial amplificationmechanism

are felt differently across firms

of

different sizes.Large

firms are directly affectedby

the externalshock

butcan

substitute their financialneeds

domestically.They

are affected primarilyby

priceand

demand

factors.The

PYMES,

on

the other hand, arecrowded

outfrom

domestic

financialmarkets

and

become

severely constrainedon

the financial side.They

are the residual claimants—

and

to a lesser extent, so are indebtedconsumers

—

of

the financialdimension

ofthemechanism

described above.Figure 14 illustrates

some

aspectsof

thisasymmetry,

starting with panel (a) thatshows

thepath of the share

of

"large" loans asan

imperfectproxy

for residentbank

loansgoing

to large firms.Together

with panel (b),which

shows

a sharp increase in the relative sizeof

large loans, it hints at a substantial reallocationof domestic

loanstoward

relatively largefirms. In the policy sectionI will

argue

thatsome

ofthis reallocation is likely tobe

sociallyFigure 14:Flight-to-Quality

(a)Shareoflarge loansin tolalloans (b)Averagesize of smallandlargetoans

i ^ i I *

Ei

Notes: (a)Tiieshare of large loansintolalloanswascomputedusinginformationonthedecomposition ofthestock of loans by loan size.Itwasassumedthatloans largerthan50000UF(around dollarsatthecurrentexchangerate)wereentirelyassignedto largefirms.Theshare of large firmsintotalloanswasthencomputedastheshare of loans greaterthe50000UFinthe totalstockof

loans, (b)Small loans are thosebetween400 and10000 UF(dollars);large loansare those greater than50000UF. The average

sizecorrespondstothestockofloansineachclassdivided bythenumberofdebtors.

Source: SuperintendenciadeBancose InstitucionesFinancieras.

The

next figure looks at continuing firms fi"om the FECUs.''^ Despite allof

these firmsbeingrelatively largepubliclytraded

companies,

one can

already see important differencesbetween

the largestof

them

and

"medium"

size ones. Panel (a) in Figure 15shows

thepath of

medium

and

large firms' bank-liabilities (normalizedby

initial assets) during therecent

slowdown.

It is apparent that larger firms fared better asmedium-sized

firmssaw

their level of loans frozenthroughout

1999.Perhaps

more

importantly, since thesum

of

loans to

medium

and

large firms rose during this period while total loans declinedthroughout

the crisis, the contractionmust have been

particularly significant in smallerfirms (thosenot inthe

FECUs).

FECU

is the acronym for Ficha Estadistica Codificada Uniforme, which is thename

of thestandardized balance sheetthatevery public firm in Chileis requiredto report tothe supervisor authority (Superintendencia de Valoresy Seguros) on a quarterlybasis. Ourdatabase contains the information on

thosestandardizedbalance sheets for every public firm reportingtothe authoritybetweenthe first quarter of1996 and thefirst quarter of 2000.

Figure 15:

Bank

DebtofPubliclyTraded

FirmsBy

Size(a)Bankliabilitiesofmediumandlarge lirms

Notes.- (a)Thedata source istheFECI!reportedbyalllistedfirmsto theChilean stockmarket

regulatory agency: Superintendeiicia de Valores y Seguros. The sample includes allfirms that continuously reported informationbetweenDecember1996andMarch2000. Withinthissample, themedium(since they are largerthan firms outside thesample) sizefirms are thosewith total assetsbelowthemedianleveloftotalassetsinDecember1996. Theseriescorrespondto the total stock ofbank liabilitiesatallmaturitiesexpressed in 1996pesos, dividedby the total levelof

assets in December1996). Thenominalvaluesweredeflated using the CPl. The totallevel of

assets in December 1996 was 788millions ofdollars for the groupofmedium size firms, and

59,300millions of dollarsforthegroup oflargefirms.

In

summary,

despite significant institutionaldevelopment over

the lasttwo

decades, theChilean

economy

is still very vulnerable to external shocks.The

main

reason for thisvulnerability

appears

tobe

adouble-edged

financialmechanism,

which

includes a sharptightening ofChile's access to international financialmarkets,

and

a significant reallocationof resources

from

thedomestic

financialsystem

toward

larger corporations, publicbonds

and,

most

significantly, foreignassets.IV.

Policy

Considerations

and

a

Proposal

The

previous diagnostic points at the occasional tightening of an external financialconstraint

—

especiallywhen

terms-of-trade deteriorate—

as the trigger for the costlyfinancial

mechanism.

IV. 1

General

Policy

Considerations

If this

assessment

is correct,it callsfor a structural curebased

on

two

building blocks:a)

Measures

aimed

atimproving

Chile's integration to international financialmarkets

and

thedevelopment

ofdomestic

financial markets.b)

Measures

aimed

atimproving

the allocation offinancial resources during timesof

external distressand

across statesof

nature.While

in practicemost

structural policiescontain elementsof both

building blocks, I focuson

(b) as the guiding principle of thepobcy

discussionbelow

because

(a), at least as anobjective, is already broadly

understood

and

Chile is alreadymaking

significant progressalong this

dimension

thought its capitalmarket

reform.'^That

is, I focus primarilyon

theinternational liquidity

management

problem

raisedby

the analysisabove.'^International liquidity

management

is primarilyan

"insurance"problem

with respect tothose (aggregate)

shocks

that trigger external crises.Of

course

solutions to thisproblem

must have

a contingent nature.The

first step is to identify a—

hopefully small—

setof

shocks

that capture a large shareof

the triggers to themechanism

described above. In thecase

of

Chile, terms-of-tradeand

theEMBI-i-

probably

represent agood

starting point, butthe particular index

chosen

is a central aspectof

the design thatneeds

tobe

extensivelyexplored before it is

implemented.

The

second

step is to identify the ex-post transfers (perhapstemporary

loans rather thanoutright transfers) that are desirable.

At

abroad

level these are simply:i)

From

foreigners to domestics.ii)

From

less constraineddomestics

tomore

constrained ones.At

a generic level these transfers are clear, but in practice there is great heterogeneity inagents'

needs

and

availability, raising the information requirements greatly. It is thushighly desirable to letthe private sectortake

over

the bulkof

the solution,which

begs

thequestion of

why

is it that this sectorisnot alreadydoing

asmuch

as isneeded.

The

answer

to this question

most

likely identifies the policygoals with the highest returns.'^Here,

I usetheconcept of"structural policies"incontrast toex-post(discretionary) interventions.

'*

SeeCaballero (1999)forgenera] policyrecommendationsfortheChilean economy,includingmeasures

type(a).

My

objectivein thecurrent paper isinstead tofocusand deepen thediscussion of a subset ofthosepolicies,adding an implementation dimensionas well.

The

main

suspectscan be

grouped

intotwo

types: supplyand

demand

factors.Among

the supplyfactors, there are at least threeprominent

ones:a)

Coordination problems.

The

absence of

a well-definedbenchmark

around

which

themarket can be

organized.b)

Limited "insurance"

capital.These

may

be

due

to structural shortages ordue

to a financial constraint (in the sense thatwhat

is missing is assets thatcan be

crediblypledged by

the "insurer," rather than actual funds during crises).A

closely relatedproblem,

but with coordination aspects as well, is that an insufficientnumber

ofparticipants in the miarketraises theliquidity

and

collateral risk facedby

the "insurers. " c)Sovereign

(dual-agency)problems.

While

contracts are signedby

private parties,government

actions affect thepayoffsof these contracts.'^Among

thedemand

problems,one

should consider at least three sourcesof

underinsurance:

a)

Financial

underdevelopment.

This

leads to a private undervaluationof

insurancewithrespect to aggregate shocks.

The

latter depresses effective competition fordomesticallyavailable external liquidityat times ofcrises, reducing the private (but not

the social) valuation ofinternationalliquidity during thesetimes.'^ b)

Sovereign problems.

Implicit (free) insurance.c)

Behavioral problems.

Over-optimism.

In

my

view,domestic

financialunderdevelopment

is still aproblem

in Chile,which

givesrelevance to

demand

factor (a) and, primarilythrough

it, to supply factor (b) as it reducesthe size

of

the effectivemarket.The

remedy

to thisproblem,

however, should be pursued

through

financialmarket

reforms

rather than with extensive liquiditymanagement

strategies. Similarly,demand

factor (c)seems

tobe

a pervasivehuman phenomenon

(see forexample

Shiller 1999), but thisis tobe

dealt with apublic educationcampaign.

Having

said this, all these

problems

justifysome

limitedamount

of

centralized liquiditymanagement,

although thismust

be

done

with great care not to generate a sizeabledemand-(b)

type problem,which

is otherwise not likely to be present inany

significantamount

in the caseof

Chile.'^Ifthese conjectures are correct, they leave us with supply-(a)

and

supply-(c) as themain

issues to deal with.

At

today'sadvanced

level (foremerging

economies

standards) inChile's institutional

development,

I believe that supply-(c) is not a serious concern, exceptfor issues that

concern

exchange

ratemanagement.

As

I will discussbelow,

this exceptionis an important consideration in

my

claim that, at least fornow,

the "internationalization ofthe

peso"

isnot likely to fullyresolveChile's underinsuranceproblem.

Thus,

my

proposal

below

has supply-(a) as itsmain

concern."

See,e.g.,Tirole (2000).'^

See Caballeroand Krishnamurthy(forthcoming).

"

See Caballeroand Krishnamurthy(2001).IV.2

A

concrete proposal:

Issuing

a benchmark-contingent-instrument

The

basic proposal is extremely simple:The

CentralBank

or, preferably,one

ofthe IFIsshould issue a financialinstrument

-a

"bond"

fornow—

contingenton

theshocks

identifiedin step one. Ideally,

and hence

the role playedby

a reputable first issuer, thisbond

shouldbe free of other risks.

The

issue shouldbe

significantenough

to attract the participation ofinternational institutional investors

and hence

generate its liquidity.While

some

of thedesired insurance

may

be achieved directlyby

thisbond,

itsmain purpose

is simply tocreate the market.

With

the basic contingency well priced, it shouldbe

substantiallysimplerfor the private sector to engineer its

own

contingent instruments.It is important to realizethat the

contingency

generated via thismechanism

addresses onlythe

expected

diiferentialimpact

ofthe aggregateshocks

contained in the index. Individualagents will generate heterogeneity in their effective

hedging through

their net positionsrather than

through

achange

in the specific contingency.'" Other,more

idiosyncraticunderinsurance

problems

are also welfare reducing but are lessconnected

with aggregatestabilization,

which

is theconcern

in thispaper.''While

in principle the question ofhow

responsive shouldbe

thecontingency

to theunderlying insurance factors or indices is irrelevant since the private sectorshould be able

to

develop

the derivativemarkets

thatcan

generateany

slope theymay

need, financialconstraints

and

liquidity considerations suggest otherwise.With

thelatterconsiderationsinmind,

it is desirable tomake

thebond

contingency

very "steep," so as tominimize

theleverage

and

derivative instruments required to generate an appropriateamount

ofinsurance for large crises.

The

counterpart will probablybe

a very limited insuranceof

small

and

intermediate shocks,which

shouldbe

fine since theseshocks

seldom

triggerthefinancial amplification

mechanism

highlightedin thispaper.How

much

insurancedoes

thecountry

need?

This question is noteasy

toanswer

as itinvolves

many

general equilibrium considerations, but a very conservativeanswer

for afull-insurance

upper

bound

should

notbe

very farfrom

the partial equilibrium answer.Crises

deep

enough

to trigger thecomplex

scenarios experiencedby

Chile recently areprobably

once

in adecade

events,and

according toour

estimates earlieron

the shortfall ofresources is

about

5 billion dollars a year, lasting for atmost

two

years (recessions longerthan this are

most

likely the result ofthedamage

createdby

the lackof

insurance, ratherthan the direct effect ofthe external shocks).

But

the required insurance is only a fraction^° See

Shiller's (1993) seminal work on promoting the creation ofmacro-markets as a mechanism for

insuring microeconomic risks. While

much

ofhis reasoning applies in the context I have discussed aswell,

my

ultimate focus ison theequilibrium (macro)-benefits ofmicroeconomicinsurance with respect tomacroeconomic shocks, rather than on the direct microeconomic welfare enhancing features of such

insurance. ^'

Also, insurance against aggregate shocksis morelikely tosupport a market instrument as its solution, asopposed tomoreexpensive(lessliquid)individuallytailoredinsurancecontracts.

of

this shortfall since all that isneeded

is that these resourcesbe

lent, not transferred. Ifwe

conservatively

assume

that theaverage

spreadon

Chilean external debt risesby

400

basispoints, the required insurance is effectively

200

millions per crisis year (with the loancommitment

or credit line).Gathering

all these factors puts the fair price of full-insuranceat

around

40

millions a year.Of

course

prices for this typeof

insurance arenever

fair, butthe point of this "back-of-the-envelope" calculation is that the

amounts

involved are notlarge.

The mapping from

theabove

tothe sizeof

the contingentbond

issues requireddepends

on

the slope of the contingency,

amount

of insurance required (full insurance is highlyunlikely to be optimal),

and

other design issues.Of

course, thebenchmark bond

should

represent only a small fraction of the total

amount,

as hopefully the private sector willfollow behind, but it

cannot be

too smalleither, since itneeds

tobe

liquidenough from

theoutset.

All the

above

refers to the insurancebetween

foreignersand

domestics, but there is also aneed

to create a substantialamount

of domestic

insurance.Large

corporations with betteraccess to international financial

markets

should be able to profitfrom

arbitraging theiraccess to smaller

domestic fums,

rather thanmove

inward

toborrow

in thedomestic

markets

during timeof

distress, as ithappened

in the recent episode.Probably

thedomestic

banking

system

isthe natural institution to administer this side of the contingentstrategy,

which

willprobably

require regulatorychanges

toaccommodate

thisnew

roleefficiently.

The

question ariseson

whether

thedevelopment

ofsuch contingency

hasany obvious

advantage over

the admittedly simpler strategyof

"internationalizing the peso;" that is, ofplacing

abroad

bonds

denominated

in Chilean pesos. This is the strategy currently beingpursued, with the support

of

a recentWorld Bank

issuance forUS$

105

million." Inmy

view, while the

shocks

indexing thecontingency

will in all likelihood put pressureon

theexchange

rate,and hence

thepeso-bonds

serve a role similar to the contingent instrumentsI

have

proposed, there is a clear disadvantage in them:The

Chilean authorities largelycontrol the value

of

the peso,and

therefore thiscontingency

is unlikely to appeal theinsurers (or

bond

holders) asmuch

as anexogenous

contingency.Moreover,

and

somewhat

paradoxically, apeso-denominated

bond

may

not onlybe

subjected to a higherpremium

due

to the riskof

CentralBank's

manipulationof

theexchange

rate, but itmay

also not

prove

a veryeffective insurancemechanism

if, forexample,

the authorities decideto

dampen

anexchange

rate depreciationthat is riskingan

inflation target.'^The

disadvantage of the contingentbond,

on

the other hand, is that it ismore

difficult to^^

The

bond wasfloated in

May

31, 2000,foran amountof$55,000nnillion ofChilean pesos.The

bondshave5 years of maturity(toberepaidon June4"^,2005), acouponof6.6%, and areindexedtoChilean

inflation. Mostofthe issuewas acquiredby Chilean institutional investors(75%),whiletherest was

placed

among

international investors. Chase Manhattan International Ltd,New

York,actedas directorbank.

^^

The

socalled "fearoffloating"(CalvoandReinhart 2000).