in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

0-03-Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Current

Account

Deficits

in

the Euro

Area.

The

End

of

the

Feldstein

Horioka

Puzzle?

Olivier

Blanchard

Francesco Giavazzi

Working

Paper

03-05

September

17,

2002

RoomE52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be downloaded

without

charge

from

the SocialScience Research Network

Paper

Collection atMASSACHUSETTSINSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY

End

of

the

Feldstein

Horioka

Puzzle?

Olivier

Blanchard

and

Francesco

Giavazzi*September

17,2002

In 2000-2001, the current account deficit of Portugal reached

10%

ofGDP,

up

from2-3%

atthestartofthe 1990s. Forecasts areforthesedeficitsto continue in the

8-9%

range for the indefinite future. Greece is not farbehind. Its current account deficit in 2000-2001

was

equal to6-7%

ofGDP,

up

from1-2%

in the early 1990s,and

again, the forecasts are for deficits toremain high, in the

5-6%

range.This is not the first time that

some

of the smallmember

countries ofthe

European Union

run large current account deficits. In the early 1980s,Portugal for

example

ran deficits in excess of10%

ofGDP.

But

thesedeficitshad

a very different flavor: Portugal thenwas

still reeling from its 1975revolution, from the loss ofits colonies,

and

from the second oil shock; thegovernment was

running alargebudget

deficit, inexcess of16%

ofGDP. The

"MITand

NBER,

andBocconi,NBER

andCEPR,

respectively.We

thank the Brook-ingsPanel and our discussants for their very useful comments.We

thank the staffs of the the central banks ofGreeceand Portugal, and in particular Isaac Sabethai, Pedro Portugal, and Luisa Farinha for their help.We

thank Pierpaolo Benigno, Rudi Dorn-busch, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, Philip Lane, Franco Modigliani, Thomas Philippon,and Jaume Ventura fordiscussions and comments, and Battista Severgnini for excellent researchassistance.

Current Account Deficits

current account deficits werewidely perceived as unsustainable,

and

indeed they turned out to be:Between

1980and

1987, theescudowas

devalued by60%, and

thecurrentaccount deficiteliminated. In contrast, Portugaltodayisnotsufferingfrom largeadverse shocks; theofficial budgetdeficithas been reduced since the early 1990s (although with

some

signsof relapse in 2002, as current estimatesimply that Portugalmay

exceed the limitsimposed

by the Stability Pact),and

financial marketsshow no

sign of worry.The

fact that Portugaland

Greece are eachmembers

ofboth theEuro-pean

Union

and

of theEuro

area, and, in each case, the poorestmembers,

suggests a natural explanation for these current account deficits.

They

areexactly

what

theory suggestscanand

shouldhappen

when

countriesbecome

more

closely linked ingoods

and

financial markets.To

the extent that they are the countries with higher rates ofreturn, poor countries should see an increase in investment.And

to the extent that they are the countries with higher growth prospects, they should also see a decrease in saving. Thus,on

both counts, poor countries should run larger current account deficits.Symmetrically, richercountries should run larger current accountsurpluses.

The

purposeofour paper istoseewhetherthishypothesisindeed fitsthefacts.

We

conclude that it does, with saving rather than investment as themain

channel throughwhich

integration affects current account balances.We

proceed infour steps.First,

we

use a workhorseopen

economy model

toshow

how, for poorercountries, goods

and

financialmarket

integration are likelyto lead both toa decrease in savingand an

increase in investment,and

so, to alarger current account deficit.We

also discusshow

other, less direct, implications of the process ofintegration, such as domesticfinancial liberalization, are likelytoreinforce the outcome.

Second,

we

look at the panel data evidence from theOECD

since 1975.We

document

thatthe recent evolutionofPortugaland

Greeceisindeed partsteadily increased since the early 1990s.

And

currentaccount positions havebecome

increasingly related to the levelofoutput per capita of the country.Thisevolution isvisiblewithin the

OECD

asa whole, butisstrongerwithinthe

European

Union,and

stronger still within theEuro

area.The

chan-nel appearsto be primarily through a decrease in saving

—

typically private saving—

ratherthan through an increase in investment.Third,

we

return to the cases ofPortugaland

Greece.We

concludethat the recent history of thetwo

countries is largely consistent with the find-ings of the panel data regressions.Lower

private saving—

due

to both in-ternaland

external financial market liberalization but alsoto futuregrowth prospects—

and, toalesserextent, higher investment, appeartobe themain

drivers of the largercurrent account deficits.

We

end

by takingup two

issues raised by our findings. First,we

relateour resultstothelarge

body

of research triggered by the "Feldstein-Horioka puzzle"—

the finding of a highcross-country correlation between savingand

investment.

We

show

that, consistent with our findings, this correlationhas substantially declined over time, especially within the

Euro

area.At

least for this last group ofcountries, the Feldstein-Horioka fact appears to be largely gone. Second,

we

discuss whether the current attitude of benign neglect vis a vis the current account inEuro

area countries is appropriate,or whether countries such as Portugal

and

Greece should worry and take measures to reduce their deficits.We

conclude that, to a first order, they should not.1

Current

Account

Balances

and Economic

Integration

A

country that wants toborrow

from the rest of the worldmust

take intoaccount two elements: the interest rate;

and

the price cuts it will need tomake

to generate sufficient export revenues to repay the debt in the future.Current Account Deficits

a flatter cost ofborrowing, clearly

makes

itmore

attractive to borrow.In-creased goods

market

integration, i.e. amore

elasticdemand

for thecoun-try's goods, decreases future required price cuts

and

so has a similar effect.Thus, in response to increased integration, borrower countries will

want

toborrow

more.And,

by asymmetric

argument, lender countrieswillwant

tolend more.

The

distribution of current account balances will widen.1The

purpose of the

model

below is to formalize this argument.The

model

isstraightforward; but it will be useful in organizing the empirical

work and

discussing

some

ofthe policyand

welfare issues later on.21

A

classicexampleoftheeffectsofeconomicand monetaryintegrationisthat ofPuerto Rico's integration with the rest of the United States in the early postwar period.An

equally classic analysis ofwhat happened—

an analysis made feasible by the fact that statisticsonflowscontinuedtobecollectedevenafterintegration—

canbefoundinIngram[1962]. Between the early 1950s andthesecond part ofdecade, asa result ofincreased financial integration between the island and the rest of the United States, net private capitalinflowsintoPuerto Ricofrom therestoftheU.S.jumpedfrom3 to11%ofPuerto Rico's

GDP

per year. Onehalfofthese inflowscameintheformof directinvestment,one halfin theformoflong-termborrowing by localbanks; bothofthesesources of external financinghad been virtually non-existent upto the mid-50s. Investment increased from 16 to20%

ofGDP. Thecurrent account deficit between Puerto Rico and the rest ofthe United States, widened even more, reaching, by 1958, a stable level of 12 per cent ofGDP

per year, and reflecting not only an increasein investment, but also adecrease in saving. Inalateressay,Ingram [1973] usedtheexperience ofPuerto Ricotosuggest that a European monetary union would free member states from the link between national savingandinvestment. Ourpaper can beseen ascheckingIngram'shypothesis.An

earlymodelof the evolutionofthe currentaccount alongtheselineswasdeveloped by Fischer and Frenkel [1974].An

overlappinggeneration version was later analyzedby Dornbusch [1983].Think

of a group ofn

countries trading goods and assetsamong

them-selves (forconvenience,

we

shallsometimes

refertothisgroupof countries as the "world" butwhat

we

have inmind

is the set of countries in the trading group).Each

country produces itsown

good, but households in each countryconsume

thesame

composite good.Households live for

two

periodsand

maximize: log(G)+

log(Q

+1)

where:

and

their intertemporal budget constraint isgiven by:Q

+

((1 +.r)/?)"1

C

(+1=

P

tY

t+

{(l+

x)R)-1

P

t+iY

w

P

isthepriceofthegood

produced by the country, in termsofconsump-tion.

R

isthe interest ratein termsof the compositeconsumption

good, theconsumption

interest rate forshort.The

parametera

is the elasticity ofsubstitutionamong

goods, and, tosatisfy the Marshall-Lerner condition, is

assumed

to be greater than one.The

parameterx

is awedge

between the worldconsumption

interest rateand

the rate at which a country can borrow(We

are considering here a borrower country).For thetime being,

we

take production as exogenous. Thus,movements

in the current account reflect only savingdecisions.

pe-Current Account Deficits

riod is given by:

Ct

=

2

{PtYt

+

W+*)

Pt+lYt+l)Define ca as the ratioofthecurrentaccount balanceto national income.

Then,

ca isgiven by:The

three terms in the expression in brackets on the right give thede-terminants ofthecurrent account balance:

•

Output

growth.The

first term is equal toone

plus the rate ofgrowthofdomestic output.

The

higher output is next period relative to this period, the largerthe current account deficit.•

The

interest rate.The

secondterm

givesthe effectofthe interestratefaced by the country.

The

higher theconsumption

interestrate, orthe higher the wedge, themore

expensive it is to borrow, the lower the current account deficit.•

The

rate ofchange in the terms oftrade.The

thirdterm

is equal to one plusthe rate ofchange ofthe price ofthedomesticgood

in termsofconsumption.

The

larger the fall in the price ofthe domesticgood

required next period to sell domestic

goods

and

repay the debt, themore

expensive it isto borrow, the lower the current accountdeficit.The

expression aboveprovides the right startingpoint toshow

the effectof integration on thecurrentaccount balance of acountrythat, like Portugal

and

Greece, is poorer than its trading partners, but catching up.Assume

Current Account Deficits

lookingat toworldvariables.

Assume

alsothatall other countries are fully integrated, thus facing thesame

interest rateR

(with no wedge).Under

these assumptions,sum

the first-order conditions for thecon-sumer's problem (l/Cf

=

R(\/Ct+\)) over countries.Use

the fact that aggregateconsumption

is equal toaggregate income, to get:/r

1=

yr/Yr

+1=

i/(i+

<7*)

where

Y*

is the average world level ofoutput,and

g* is the world rate of output growth.Noting that the

demand

for thegood

produced in a given country isgiven by:

Pi

=

(Yt/YtT

1/a

and

correspondingly forPt+i,we

can express the current account as:m

t=-(1

-——(——

)2 1

+

x

1+

g*So, ifoutputgrowthin thecountry

we

are consideringexceedstheoutput growth ofits trading partners,and

the borrowingwedge x

is not too large,the country will run a current accountdeficit.

Using thisexpression,

we

cannow

return tothe effectsof integration on the current account balance. For countries such as Greeceand

Portugal, economic integration hashad

threemain

dimensions: the SingleEuropean

Market, which mostly affected the product market; the integration of finan-This assumptioniseasilyrelaxed

—

atsomecostinthe algebra. Relaxingitintroducesanadditional effect,thedependenceofthe slope of thesupply offundson n,thenumber

oftrading partners: Thelarger n,the smaller theeffectofborrowing bythecountryonthe equilibrium consumption interest rate,sothe flatter thesupply offunds tothe country. Thisprovides anotherdimensionofintegration,namely asanincrease in n.

Current Account Deficits

cial marketswithin the

European

Union;and

finally,monetary

union, with the adoption of theEuro

in the late 1990s. All three channels have clearly•worked in the direction of potentially widening the current account deficits

of these countries:

• Since the early 1990s, the single

European

market has led to anin-creasein <j, the elasticity of

demand

facingdomesticgoods

within theEuropean

Union:Beyond

the elimination oftariffsand

a sharperenforcementofcompe-tition rulesacross the

European

Union, factorssuch asthe harmoniza-tion ofsafety requirements for products, the extension of distribution networks, have ledtogoods

beingcloser substitutes (either in product or geographic space),and

thus to a higher elasticity ofdemand

foreach good.4

As

a result, goodsmarket

integration hasreduced theadversetermsof tradeeffectacountry faceswhen

itneedsto generatea current account surplus to repay the debt: this hasmade

borrowingmore

attractive.Going

back to the expression above for the current account,assume

that the country

we

are looking at has a higher growth rate than itstrading partners, so it is running a current account deficit. Then, the higher a, the larger the size ofthe deficit.

• Financial integration has led to a decrease in the

wedge x

within theEuropean

Union.Beyond

the elimination ofcapitalcontrolsand

otherexplicitbarrierstofinancial flows, theharmonizationoffinancialmarket ruleshasreduced

4

In ourspecification, a was formallyintroduced asa taste parameter. Think instead ofour specification of utility asa reducedform reflecting the higher substitutability of products,for whateverreason.

regulatory uncertainty faced

by

foreign lenders,and

has improved the transparency ofinformation on potential borrowers:Thanks

to the "single passport" legislation (the 1993EU

InvestmentServices Directive which addressed the cross-border activities of all

types of financial firms), an

EU

bank

that wishes todo

business inanother

member

stateno

longer needs tosetup

a full subsidiaryand

besubjectto local regulation

and

supervision: Itcando

business there opening a branch, or, evenmore

simply, operating directly from itshome

base where all the key aspects ofitssolvency, liquidity,and

risk aresupervised by itshome

regulator. In parallel, theharmonizationof firms' reportingrequirements has improved information and decreased the risk faced by foreign lenders.Also, as emphasized by Gourinchas

and

Jeanne [2002], by increasingthe cost of expropriation of foreign lenders

and

investors, financial integration has also decreased the risk of expropriationand

thus therisk

premium

they required.•

Monetary

union has led to a further decrease in .t within theEuro

area.

Monetary

union has eliminated currency risk.While

foreign exchangerisk

among

EMS

countries certainlydiminished after the currencyre-alignments of the early 1990s

—

as these realignments eliminated themost

obvious cases of overvaluation—

the cost incurred bysome

in-vestorsand

financial institutions during theERM

crises of 1992-93 remained in thememory

ofmarket participants. This lingeringuncer-tainty

was

only really eliminated in the late 1990s, as adoption of theEuro became

a near certainty.Elimination ofcurrency risk increases the relative importanceof other elements of risk: Credit risk has

become

themost

importantCurrent AccountDeficits 10

implication that the relativequality ofunderlyingcredits, rather than

judgments

about thestabilityand

volatility ofthe currency, drivesse-curities prices. All of this obviously makes,the "national" dimension

of capital flows increasingly fuzzy.

Monetary

union has also led to largerand

deeper markets for specificfinancial instruments, such as the

market

forEuro

bonds;we

shall seeexamples ofthis

when we

return to the cases ofPortugaland

Greecelater.

So

farwe

havefocused only on saving, but it is straightforward tointro-duce investment

and

build on this simple structure.The

results can easilybe

summarized

in words:• Allow production to

depend

on capital,and

take a country which ispoorer in the sense of having less capital,

and

thus a higher marginal product of capital than the others.How

much

investment will take place willdepend on

both the costofborrowing,and on

theevolutionofthe terms of trade: the lower the relative price ofdomestic goods

in the future, the less attractive it is to invest in the production of domestic goods.

Then, very

much

for thesame

reasonseconomic

integration is likely to lead to a decrease in saving, it is likely to lead to an increase ininvestment. Rather obviously, to theextent that financial integration

leads to a lower cost of finance, investment will increase.

And

to the extent that goods market integration leads toan

increase in theelasticityof

demand

for domesticgoods, investment will also increase:The

higher the elasticity ofdemand,

the smaller the decrease in priceneeded to sell the additional output in the future,

and

so themore

attractive investment this period.

and

indirectly, to a larger current account deficit than was the casein our

model

above. Directly, as the increase in investment is onlypartly offset by an increase in saving. Indirectly, to the extent that higher investment leads to higher expected growth, (an increase in

g

relative to g*), higher real income in the future,and

so lower savingthis period.

• Poorercountries are poorer not only because they havelower capital,

but alsobecause they have lowertotal factor productivity. Again, the evidenceis that both goods

and

financial market integration are likely to lead, in particular through higher competition, to an increase in total factor productivity.5To

the extent that this is the case, this is likely to improve growth prospects in poorer countries,and

lead to a further decrease in saving.• Financial integration often comes, at least in part, with domestic

fi-nancial liberalization.

New

instruments, forexample more

flexiblemortgages,

may

be introduced.To

the extent that this is the case,and that domestic financial liberalization leads to lower saving, the

effect

on

integration on the current account will be reinforced.To

summarize:Both

financialand

goods market integration are likelytolead, in the poorercountries, to both adecrease insaving

and

an increaseininvestment,

and

so to adeterioriation ofthe current balance.How

much

of the adjustment takes place through lower saving,how much

through higher investmentdepends,among

otherfactors,on

therelative roles of capitaland

TFP

inexplainingdifferences in incomeper capita across countries,and

therelative rolesof financial integration

and

financial liberalization.Seefor example the findings ofarecent McKinsey report on France, Germany, and

Current Account Deficits 12

2

The

Widening

of

Current

Account

Balances.

Panel

Data

Evidence

Having

laiddown

a simple frame,we

now

return to the data, not only forPortugal

and

Greece butfortheOECD

in general,and

theEuropean Union

and

theEuro

area in particular.To

organize the discussion,we

typically present results for four groups ofcountries:•

"OECD

minus", i.eallOECD

countriesexceptMexico,Turkey,Korea, CentralEuropean

countries(The

Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary,and

Poland),and

Luxembourg

—

22 countries in all.The

reasons forremoving those countries vary.

The

mechanisms

behind theevolu-tion of current account deficits in Mexico, Turkey,

and

Korea, threemuch

poorer countries, are likely to be different from those in thericher

OECD

countries.Data

for CentralEuropean

countriesonly ex-ist from 1990 on, so the countries cannot be usedwhen

constructing a balanced panel (we shall briefly report the results from unbalanced panel regressions below).And

theeconomy

ofLuxembourg

is highlyidiosyncratic; in particular,

Luxembourg

reportsconsistentcurrentac-count surpluses ofthe order of

30%

ofGDP.

•

"European

Union

-', or

EU

for short, the group ofEuropean Union

countries, again excluding

Luxembourg

—

so 14 countries in all.The

rationale for looking at this subgroup of

OECD

countries is obvious.Ifintegrationisthe basic force behind the wideningofcurrent account balances, one

would

expect theeffectof the SingleMarket

tobemuch

stronger for

EU

countries than forOECD

countries in general. • "Euro area", orEuro

for short, the countriesnow

in theEuro

area,minus

Luxembourg,

so 11 countries in all. (Greece, which joined inisequally obvious.

With

the fixingof parities in 1999,and

theshift tothe

Euro

atthe end of the 1990s,onewould

again expect thedegreeof integrationto be stronger forEuro

countriesthan forEU

or a fortioriOECD

countries in general.• "Euro minus", the set ofcountries in the

Euro

area,minus

Portugal and Greece, 9 countries inall.The

reason forlookingat thissubgroupis simply to see

whether

the resultsfor theEuro

area aredue to these two countries or hold even in the rest oftheEuro

area.To

start. Figure 1 reports the standard deviations of the cross-countrydistribution ofthe ratio of current account balances to

GDP

foreach year.For current account balances

—

and, later, savingand

investment—

we

use data from theEuropean

Commission

database, calledAMECO

(which stands for"Annual

Macroeconomic

Database ofDG

Ecfin").These

arebased on national

income

accounts and, post 1995, on theESA95

EU

ac-counting system.

The

numbers

are not always equal to those published by theOECD,

which appear sometimes basedon

other sources (forexample

the

OECD

current account data for Greece are basedon

Bank

of Greece data, which are constructed usingbank

settlementdata rather than tradedata).

The

differences can benon

negligible: In 2000, the current accountdeficitofGreece

was

4.5%

accordingtotheEU,

7%

accordingtotheOECD.

But

the differences are mostly level differences,and

the conclusions below are roughly unaffected by which serieswe

use.6A

largerissueiswhether weshouldlookat thecurrentaccount balanceorthechange inthe net foreignassetpositionofthecountry—

which,inprinciple, includes revaluations ofassetsandliabilities. Becauseof themeasurementissuesassociatedwithavailableseries forchangesinnetforeign assets,weprefertouse theseriesforthecurrentaccountbalance. For thesetofcountrieswelook at, the general evolutionswedescribebelowarerobust toEuro [» en Union

19"J0 19^0 19^0 20uO

Figure1a. StandardDeviations.OECD.EUandEURO, 1975-2000

EuroareaminusinandPn

19*70 19

-80

Figure la reports results for each of the first three groups described above.

The

timeseries have threecharacteristics:•

The

results are similar across the three groups; indeed, there is noevidence of stronger widening of balances for either the

Euro

area or theEU

than for theOECD

as a whole.•

There

is a sharp but temporary increase in the standard deviation inthe early 1980s.

•

There

is a steady increase in the standard deviation since the late1980s, leading to a

more

than doublingofthestandard deviation over the last 15 years.A

further look at thedata suggests a sharpdifference between the shortlived increase of the early 1980s

and

the steady increase later on.The

in-creaseoftheearly 1980s isentirelydueto largedeficits injusttwo

countries.The

first is Portugal.We

briefly discussed the episode in the introduction, a period of very large unsustainable deficits,due

to the aftermath of therevolution, the loss ofcolonies, the second oil shock,

and

aloss ofcontrol offiscal policy.

The

second is Ireland, where the combination of the oil shockand

a fiscal expansion (with fiscal deficits exceeding12%

ofGDP)

also ledto very large and unsustainable current account deficits.

The

point thatnearly all ofthe action in the early 1980s

comes

from thesetwo

countries isshown

in Figure lb, which plots the standard deviation forEuro

countries,with

and

without Portugaland

Ireland.When

thetwo

countries are left out, the peak of the early 1980s is fully gone,and

the standard deviationrises

more

or less steadily from the early 1980s on, with a sharper increasein the 1990s.

whether oneuses currentaccount balances orchangesin net foreignasset positions. For

Current Account Deficits 15

The

next step is to try to explainwhich

countries have been runninglargerdeficits,

and

which countries havebeen

running larger surpluses.Ba-sic growth theory,

and

theopen

economy

model

presented in the previoussection, suggest exploring the relation between thelevel ofoutput per capita

and

the current account balance. Countries that are poorer havemore

po-tential for catch-up, either through capital accumulation, or technological progress (for empirical evidence

on

convergence within theOECD,

see forexample

Barroand

Sala-i-Martin [1992]).Economic

integrationmakes

iteasier for these countries to borrow,

and

thus to run larger current accountdeficits.

We

take a first pass at the data in Figure 2.The

figure is a set ofscatterplots ofthe time average of the ratio ofthe current account deficit

to

GDP

against the time average ofoutput per capita, fortwo

subperiods, 1985-1994and

1995-2001,fordifferentgroup

ofcountries.Output

per capitaisconstructed as

PPP

GDP

per capita in 1985 dollars, using the data from Hestonand

Summers

up

to 1992,and

extrapolated using realGDP

growthrates thereafter.

The

choiceof1985 as a startingdate isto avoidtheepisode of the early 1980swe

saw

earlier.The

firsttwo

panels give scatterplotsand

the regression line for

OECD

minus, the secondtwo

forEU, and

the thirdCunvnt

Account Deficits 16OECD

minus

1985-1994CA/GDP

=

-1.8+

0.09Y/N

(t=

1.5)R

2=

0.01 1994-2001CA/GDP

=

-6.8+

0.49Y/N

(t=

5.2)R

2=

0.13EU

1985-1994CA/GDP

=

-1.9+

0.12Y/N

(t=

2.0)R

2=

0.03 1994-2001CA/GDP

=

-11.8+

0.94Y/N

(t=

10.2)R

2=

0.48EURO

1985-1994CA/GDP

=

-2.8+

0.23Y/N

{t=

3.4)R

2=

0.10-13.5

+

1.10Y/N

(i=

11.0) J?2=

0.58 1994-2001CA/GDP

=

The

figureand

associated regressions havetwo

striking features:•

There

isa substantial strengthening of therelation betweenthecurrentaccount

and

output per capitafrom the first tothe second subsample.Except

for theEuro

area, the coefficient is typically insignificant for1985-1994; it

becomes

much

largerand

very significant in 1995-2001.•

The

increase isstrongerfortheEU

than fortheOECD

asawhole,and

stronger for the

Euro

areathan

for theEU

(although the differencebetween

EU

and

theEuro

areais neither statistically oreconomicallysignificant).

Both

features are verymuch

consistent with the idea that integrationis an important factor behind current account evolutions. Integration

was

higher to start with within the

EU

or theEuro

area,and

has continued at a higher pace.To

look at the relation further,we

run the followingspecification:

(CA/Y)

it

=

at+

bt(^2#) +

X

u

p

+

eltThe

specification is largely standard (for recent surveysand

extensions of the literature ofthe determinants of current accounts, see forexample

Debelle

and

Faruqee [1996] orChinn and

Prasad [2000]. ):The

ratio ofthe current account balance to output in year t for country i

depends

on acommon

time effect, on the level ofincome

per capitain year t for countryi relative to the average level of

income

per capita in year t for the group of countrieswe

are looking at,and

on other control variables included inthe vector

Xu-

The

onlynon

standard aspect ofthe specification,and

the one central to our exploration here, is thatwe

allow the effect of the levelof

income

percapita, to vary from year to year.In our basic specification,

we

usetwo

controls (in addition to the timeeffects).

The

first is thedependency

ratio, constructed as the ratio of pop-ulation to the labor force: Other things equal,we

expect a country with arelatively higher

dependency

ratio to save less.The

second is the rate of growth of output from year t—

1 to t, to capture cyclical effects ofmove-ments

in outputon

the current account.The

theorywe

saw

earliersuggeststhat integration

may

also affect the elasticity of the current account with respect to cyclicalmovements;

for this reason,we

also allow the effect of output growth to vary from year to year.(The

results are nearly identical ifwe

use themeasure

ofthe output gap constructed by theOECD,

amea-sure which aims at capturingcyclical

movements

in output).The

period of estimation runs from 1975 to 2001.The

starting yearisconstrained by the availability of comparable data on saving, whichwe

usewhen

we

analyzethe

components

ofthecurrent account separately below.The

simplestway

topresentourresultsisby plottingthesetofestimatedEURcf EUROMlfjUS

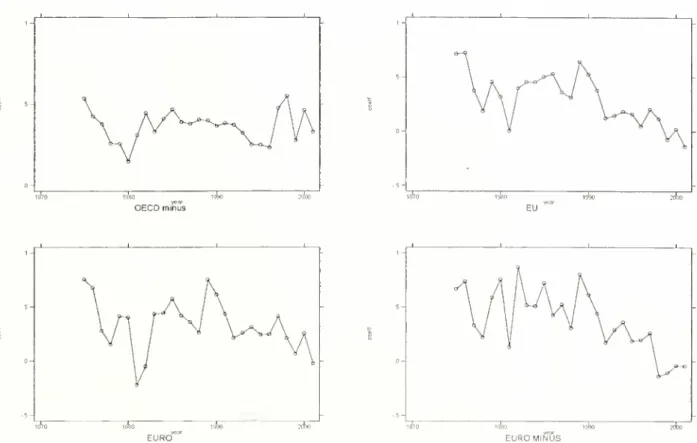

• Figure 3a

shows

the results forOECD

minus.The

coefficient is nearly always positive, but there isno

obvious trend. In other words, the widening of current account balances does not appear to reflect an increaseddependence

of the current account on the level ofincome.• Figure

3b

does thesame

for theEU.

There, the evolution of thees-timated coefficients resembles the evolution of the standard deviation

earlier.

The

high deficits of the early 1980s in both Portugaland

Ire-land,two

relatively poor countries leads to a temporary increase inthe coefficient.

And

one also sees the steady increase in the coeffi-cient from thelate 1980son.By

themid-1990s, thecoefficient is both statisticallyand

economically significant. For example, the estimatedcoefficient of0.2 in 2000 implies, that, other things equal, for a

coun-trywith an

income

per capita40%

below the averageEU

level (whichis roughly the case for Portugal

and

Greece), the ratio ofthe current accountbalance toGDP

should be 8 percentage points lowerthan theEU

average. (In 2000-2001, the current account for theEU

was

ex-actlybalanced.The

deficit for Portugal was, aswe

have seen, roughly10%

ofGDP).

• Figure 3c does the

same

forEURO.

The

coefficients look verymuch

the

same

asfortheEU;

thisis not a greatsurprise, given that the largeoverlap between the

two

groups of countries. Figure 3d finallyshows

theresults forthe

EURO

minus,tocheck the influenceofPortugaland

Greece.

The

increaseisactually largerin the 1990swhen

Portugaland

Greeceare leftout, with the coefficient reaching 0.35 in 2001.

In short, Figure 3 suggests that, for the

EU,

the widening of current account positions can be largely accounted for by an increaseddependence

on

output per capita.The

effectseems

weaker, if present at all, for theCurrent Account Deficits 19

How

robust are theseresults?We

haveexplored anumber

ofalternative specifications:•

Income

per capitamay

be apoor

proxy forwhat

we

are trying tocapture.

While

convergence ofincome per capita appears to hold forthe set of countries

we

are looking at,some

of the poorer countriesmay

have a bleak future.Some

rich countriesmay

be appealing toforeign investors, for reasons having to

do

both with expected returnand

with risk characteristics; think forexample

ofthe United States,and

its long string ofcurrent account deficits. (Thistheme

has been explored, boththeoreticaland

empirically,by

Ventura [2002]and

Lane

and

Milesi-Ferretti [2001b].)Thissuggests replacingoutput per capitain ourregressionsbythe ini-tial net asset position ofthe country,

and

again interact its coefficientwith time.7 Presumably, if a country has been borrowing steadily in

the past, so itsasset position is negative, it has characteristics which are attractive to foreign investors. Further financial

and

economicin-tegration are then likely to allow for

more

foreign inflows,and

thuslarger current account deficits.

Figure 4

shows

the setofestimatedcoefficientsfrom aregression usingforeign assets per capitain 1990 (rather thanincome percapita).

The

variable for net foreign assetscomes

fromLane and

Milesi-Ferretti [2001a]and

ismeasured

in millionsof dollars. (Regressionsusingeither foreign assets per capitain 1980, or foreign assets per capita for eachyear, give very similar results.) Becausethe level offoreign assets can be positive or negative,

we

cannot use thesame

normalization as forincome per capita;

we

use instead the difference between the level ofFor more on therelation between foreign asset positionsand incomeper capita, see

Current Account Deficits

20

foreign assets for country i in year t

and

the average level across the relevant group of countries in year t.The

main

conclusionswe

draw

from the four panels are two:

The

coefficients aretypically positive: Countries which haveborrowed

in the past tend to run current account deficits. This conclusion has

beenwell

documented

byothers.But

there isnoevidence of a strongerrelation

between

the financial asset positionand

the current account balance. FortheOECD

minus,thecoefficientsaretypically significant,but

show no

trend.And

fortheEU

and

theEURO,

thetrendisclearlythe other way, with a steady decrease in the coefficient over time. •

The

currentaccountreflectsnotonly thebehaviorofprivatesavingand

investment, but also of public saving. Unless Ricardian equivalence

holds, public savingislikelytoaffecttotal saving,

and

thus the current account.And

one ofthemain

evolutions of the 1990s has been, as aresult of Maastricht, a strong

improvement

in the fiscal position ofmost

European Union

countries.With

this motivation,we

haveexplored a specificationadding another control variable to the basic specification, the ratio of structuralpri-mary

balances (as constructed by theOECD)

toGDP

for each yearand

each country.The

results are easy to summarize. For all four groupsofcountries, thecoefficienton

the fiscal variableis tightlyesti-mated,

and

very significant. For theOECD

as a whole,an

increase inthe structuralprimary balanceof

1%

ofGDP

leadstoanimprovement

inthe current account of0.2%.

The

estimates are nearly identical forthe

EU

and

theEURO.

But

the time series ofestimated coefficientson output per capita is nearly identical tothat inFigure 3 (and so,

we

do

not reportthem

here). Inother words, the increasedwidening does not appear tocome

from diverging evolutions of public saving across• Accession countries, that is the countries from Central

and

EasternEurope

which are candidates to join theEU,

should provide anex-cellent test ofour hypothesis:

They

are poorer that the currentEU

members,

expect togrow

fast after joining theEU

and, inprepara-tion to entry, have undergone

some

internal liberalizationand

have started to removesome

barriers to economic integration.The

prob-lem with thesecountries isthe availability ofdata, which do not start until the early 1990s.When

we

includethem

in the regressionsre-ported above, re-run over

much

shorter samples, the results tend to confirm those presented above. This ishardly surprisingly, sincemost

accession countrieshave ran largecurrent accountdeficits inthe 1990s

(the average ratio of thecurrent account balance to

GDP

for the pe-riod 1993-2001was -3.6%

for the Czech Republic,-4.9%

for Hungary,-3.6%

for Poland,and

-9%

for the Slovak Republic).We

finally turn to whether the increased dependence ofcurrent account balances on output per capita reflectsan increaseddependence

ofsaving, or an increaseddependence

of investment.To

do

so,we

simply run the basic specification, replacing the ratio ofthe current account to

GDP

first by the ratio ofsaving toGDP,

and

then by the ratio ofinvestment toGDP.

The

four panelsofFigure5show

the resultsof the saving regression.We

draw

two conclusions:• For the

OECD

as a whole, there is notmuch

evidence of a significant effectofoutput per capitaon saving,and

noevidence of a trend.Sav-ingappearsunrelated tothe levelofincomepercapita.

The

coefficienttends to be negative (lower outputper capita leading to lower saving)

for

most

of the 1980s, close tozeroformost

ofthe 1990s, and the valuefor 2001 is roughly equal to the value for 1975.

EURCr*

ofa trend. After a sharp decline in the 1970s, the coefficient steadily increasesover time, bothinthe 1980s

and

the 1990s. Interestingly, thecoefficientchangessign:

At

thestartofthesample, savingisnegativelyrelatedto income per capita

—

asign opposite tothat predicted by the standardopen

economy

growth model. It turns positive in the late 1980s, turning larger in theEuro

area than in theEU.

Integration per se does not easily explain the change in sign, and this suggests the presence of otherfactors atwork, such asfinancial developmentorfinancial liberalization: Poorercountries haveintroduced

new

financialinstruments

and

institutions, which have led to a decrease in saving.This,

combined

with integration, has led to larger current accountdeficits.

The

four panels of Figure 6show

the results of thesame

exercise, thistime for investment.

They

suggest two conclusions.•

The

coefficient is typically negative:A

lower income per capita isassociated with higher investment, the sign predicted by thestandard model.

•

There

is however no evidenceofa trend, of amore

negative effect ofincome per capitaon investmentover time (There is a steady decrease in the coefficient starting in the mid-1990s, but this is too small

and

too recent to qualify as a trend). In short, the increased

dependence

ofcurrent account balances

on

income per capitareflects, for themost

part, an effect through saving than an effect through investment.

The

importance of the effect through saving suggests the relevance of trying to separate theeffectsof integrationand

internal financial liberaliza-tion.With

this in mind,we

have explored the effects of introducing as an additional control the ratio ofM3

toGDP,

a ratio which is often taken as a proxy for the stock ofdebt instruments available to firms and households.EUROMliJuS

and

thus asaproxy for financialdeepening(seeforexampleKing and

Levine[1993] for a use ofthis ratio as a

measure

offinancial development instan-dard growth regressions).

The

resultsshow

that current account balancesare strongly negatively related to the ratio of

M

3 toGDP,

suggesting thatinternal financial liberalization does play an independent role in determin-ing the cross-countrydistribution ofcurrent account balances.

The

effect isboth statistically and economically significant:

An

increase in the ratio ofM3

toGDP

of30 percentage points(aswas, forexample, the casein Greecein the 1990s) is estimated to lead to a decrease in the ratio of the current account to

GDP

ofabout 1.2 percentage points.But

introducingthisaddi-tional control doesnot significantlyaffect the coefficients

on

relativeincome

percapita.

Paneldata regressionsonly gosofar,

and

one often hasa better sense of the underlyingmechanisms

by lookingat individual countries. This iswhat

we

do

in the next section, wherewe

return to the experience of Portugaland

Greece.3

Back

to

Portugal

and

Greece

3. 1 Portugal

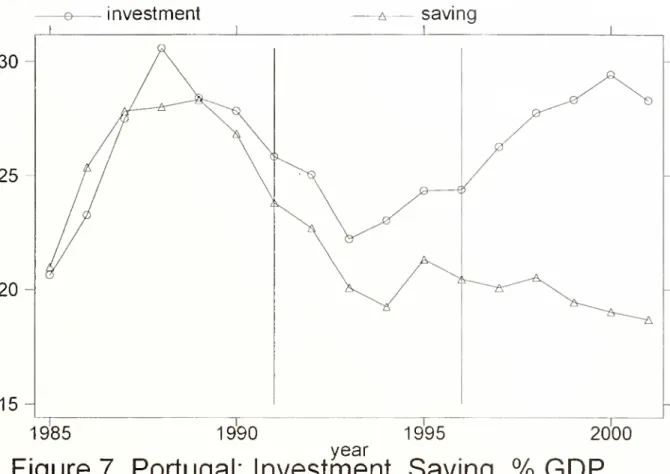

Figure 7

shows

the evolutionofPortuguese investmentand

saving, as ratiosto

GDP,

from 1985 to 2001. It clearlyshows

the steadily increasingdiver-gence between investment

and

saving,and

the resulting steadily increasing currentaccount deficit, starting in the 1980s.In trying to assess

how much

ofthechangein the current accountdeficit isdue

to a change in saving or to a change in investment, onemust

becareful in the choice of a base period.

The

early 1990swas

a period of low growth for cyclical reasons,and

so is not the right base period. Thus, inpresenting

numbers

in Table 1,we

divide time in three subperiods: 1985-1991 (1985 is the first year post-stabilization, following the largefiscaland

Current Account Deficits 2^

currentaccountdeficits

we

discussedearlier, 1991 isthelastyearofsustained growth), a periodwith an average growth rateof 5.1%; 1992-1995, a period oflow growthand

sounusually low investmentand

saving, a period with an average growth rate of 1.5%;and

1996-2001, a period of sustained growth, with an average growth rate of3.5%. Finally, toshow

recent evolutions,we

alsopresent

numbers

for2000and

2001, yearswith growthratesof3.3% and

1.9%

respectively. In reporting changes in the last column,we

report thedifference between the

numbers

for 2000-2001and

thenumbers

for1985-1991, theperiod

we

take as the base period.Table

1.Current

Account

Balance,

Investment,

and

Saving,

asratios

to

GDP,

percent.Portugal 1985-2001

1985-1991 1992-1995 1996-2001 2000-2001

A

Current account 0.6 -2.0 -7.0 -10.0 -10.6 Investment 25.3 22.8 26.6 28.1 -2.8 Saving 25.9 20.8 19.5 18.1 -7.8 ofwhich Public saving 4.6 2.3 2.6 2.4 -2.2 Private saving 21.3 18.5 16.9 15.7 -5.6 of which Household saving 9.2 8.3 5.7 5.4 -3.8 Corporate saving 12.1 10.2 11.2 10.3 -1.8A:

Difference between2001-2000

and

1985-1991. Source:European

Commission, Statistical

Annex

ofEuropean Economy,

Spring 2002.The

breakdown

of privatesavingcomes from

theDireccao General deEstudos

ePrevisao.

1985

1990

1995

year

Figure

7.

Portugal:

Investment,

Saving.

%

GDP

Current Account Deficits 25

saving, are adjusted for inflation.

More

specifically, basedon

information about the composition of debt by currency denomination,we

add

to theofficial

number

for public saving anamount

equal to inflation times the proportion of the public debtdenominated

in domestic currency times the debt.(The

adjustment matters verymuch,

as inflation hasdecreased froman

average14%

over 1985-199 to7%

over 1992-1996,and

to3.5%

since; the averageratioofpublicdebtdenominated

indomestic currencyhas remainedstable

around

50%).We

subtract a similaramount

from private saving,and

so leaveunchanged

the officialnumber

for the current account. Thisamounts

to the assumption that the public debt is held domestically; in theabsence ofseries on domestic

and

foreign holdings of public debt, there isno

obviously better feasible adjustment.8How

toallocatetheinflation adjustmentofprivatesavingbetween

house-hold versus corporate savingismuch

more

difficult.9 Itdepends

forexample

on whether

government

bonds

are heldby

householdsor financialintermedi-aries,

and

in the secondcase,on

the type ofliabilities issued by theseinter-mediaries. Further adjustments should also be

done

for nominal corporatebonds

and

other nominal liabilities, and, on the other side, for mortgagesand

otherhousehold nominal liabilities.We

couldnot obtain sufficientdata todo

these adjustments. Thus,we

use a simple rule:We

subtract thefull inflation adjustment on

government

debt from household saving: ThisEstimates from the Bank ofPortugal for the 1990s indicate that the proportion of

government debt held by non-residentholders remained low until the mid 1990s (when

the inflation adjustment matters most): 10% in 1990, 17% in 1996. Since then, the proportionhasincreasedsteadily, reaching

47%

in 2001.For a recent explorationofthe minefields associatedwith the construction of

econom-icallymeaningfulseries forhouseholdsavingintheUnitedStates,seeGaleandSabelhaus [1999].

implicitly assumes that public debt is held (directly, or indirectly through intermediaries with nominal liabilities) by households rather than

corpora-tions. Again, in the absence of relevant data, there is little choice than to

make

that assumption. Finally,we make

no

further adjustment to adjustfor other nominal liabilities.

Figure 7

and

thenumbers

in Table 1 suggest four conclusions:•

The

increase in the current account dates back to the late 1980s, but has accelerated in the second half of the 1990s. Using 1985-1991 as the base period, the current account deficit has increased by10.6%

ofGDP.

•

The

increase in the current account deficit isdue

for less than one third to an increase in investment.The

ratio of investment toGDP

has increased by 2.8 percentage points relative to 1985-1991.The

increaseis

much

larger ifwe

compare

the ratioto itsvaluein theearly1990s (an increase of 5.3%), but

much

of that increase is cyclical, reflecting the period of low growth ofthe early 1990s.•

The

increase in the current account deficit is due formore

than twothirds to a decrease in saving.

The

ratio of saving toGDP

hasde-creased by about

7.8%

ofGDP

relative to its 1985-1991 value. •The

decrease in saving reflects primarily a decrease in private saving.Public saving has decreased

by

2.2% ofGDP,

relative to 1985-1991;private saving has decreased by 5.6%. (Inflation accounting is

impor-tant here. Absent the inflation correction, public saving

would

show

a riseof

3.1%

and

the shift in private saving would lookmuch

larger,-10.1%)

the government debt held domestically was held either by households or by financial institutionswithnominal liabilitiesontheliability side.

Current Account Deficits

27

•

The

decrease in private saving reflects primarily a decrease in house-hold saving.The

ratioofhousehold saving hasdecreased by 3.8%, theratio ofcorporate savingby 1.8% (absent inflation correction, house-hold saving

would

show

a decrease of 8.3%.)We

now

look atsome

aspects ofthe story behindthese numbers.Take

the decrease inhousehold

saving

first.From

1995 to theend

of 2001, household debt has increased

from

40%

to93%

ofGDP.

Most

ofthis increase has taken the form ofeither mortgages or

consumer

loansfrom banks.At

theend

of 2001, mortgages represented39%

of totalbank

loans tothe non-financial private sector,and

76%

oftotal loans to households.Why

has there been such an increase in household debt?We

could notfindsubstantivechangesinthe types ofmortgages or loansofferedby banks.

The

decrease in interest ratesmust

be a central part ofthe story: Short-term nominal interest rates have decreased verymuch,

from16%

in 1992,to

around

4%

in 2001 (for theEuro

area as a whole, thenumbers

are11%

and

4%). Shortterm

real interest rates (measured as nominal interest ratesminus

realized inflation, using theGDP

deflator) have decreased from6%

in 1992 to roughly zero in 2001 (this is

more

than for theEuro

area as a whole,where

the rate has decreased7%

toaround 3%;

due in part to the Balassa-Samuelson effect, inflation is higher in Portugal than the averagefor the

Euro

area).Why

the low interest rates? Apart from the declinedue

tofactorscom-mon

to theOECD,

much

of it is clearly traceable to financial integration,and

the reduction ofcountry riskdue tomembership

in theEMU

first,thenadoption ofthe Euro.

The

single currency has reduced country risk by low-eringthe probability that Portugal might face a liquiditycrisisand

thusbe

forced to stop servicing its external debt. Looking at the balance sheets of banks shows that Portuguese banks have financed this increased credit

econ-omy, participation in the

Euro

has offered domesticbanks

easier accessto interbank loans from banks in other Euro-area countries.The

main

instru-ment

for raisingfunds abroad has been the issuance of international bonds through subsidiaries of Portuguese banks having their head office abroad: the yearly flow ofnew

internationalbond

issues through these subsidiariesincreased from one half of 1 million euro in 1998 to 5 billion in 2000.

The

maturity of these

bonds

(whose legal status is generally that of "subordi-nated debt") is between 3and

5 years,and

the currency ofdenomination isthe euro.

Looking

at the capital accountmakes

clear that foreign borrowing bydomestic banks has indeed played a central role in the

way

Portugal has financed its current accountdeficit.Looking

at stocks, the net foreign debt position ofPortuguese banks has increased from 9 billioneuro in 1999 to 24billion in 2001.

Looking

at flows, in 2000, the increase in grossindebtedness ofresident Portuguesebankswas

equal to17.4%

ofGDP,

the increasein net indebtednesswas

equal to 10.7%—

so larger than the currentaccountdeficit in thatyear (we are not singlingout banks arbitrarily here: all other grossportfolio

and

investmentflows are small in comparison.)Turn

now

toinvestment

Given the growth in

mortgage

loans, one would have expected thein-crease in investment to reflect disproportionately an increase in housing investment. Curiously, this is not the case. For

most

of the 1990s, hous-ing prices have increased at a rate only slightly higher than inflation.And

residentialinvestment hasremained a nearly constant fraction oftotal fixedinvestment, 21-23%.

We

haveno

explanation for that fact.Another

apparently puzzlingdevelopment,in viewof thetheorysketchedin Section 1, isthe poor performanceofforeign direct investment.

Net

FDI, whichhad

been an important source ofcapital inflows following Portugal's entryintotheEU

in 1985,turned negativein 1995and

hasremainednegativeCurrent Account Deficits

29

since then. Here, lookingat grossflows helps solve the puzzle:

• Negative net

FDI

since 1995 istheoutcome

ofarapid increase inbothinflows

and

outflows, butmore

soin outflows than inflows:• In the late 1980s, following

EU

accession,FDI

into Portugalhad

in-creased rapidly, reaching

4%

ofGDP

in 1990.But

then, the inflowsslowed down,

coming

to a near standstill in 1995. Since 1995, theinflows have increased again. In 2000, they stood at twice their 1990

level (in dollars), the previous peak.

• Outflows, however,

which had

been roughly unaffectedby

EU

acces-sion, have increasedeven faster, reaching, in 2000,5%

ofGDP.

Most

ofPortuguesedirect investmentabroad takes the form ofacquisitions,

and

much

of it,40%

ofall outflows, goes to Brazil—

direct investmentin other

EU

countries is only15%

ofall outflows.Our

interpretation ofthis fact is that it is,somewhat

paradoxically,the result of financial integration within the

Euro

area,and

of therole information plays in direct investmentflows.

Our

guess, basedon the largevolume

of issuesofEuro bonds by

Portuguese firms, is thatEuropean

direct investment in a country such as Brazil is carried outmainly through Portugal, which presumably has a comparative ad-vantage in understanding business in that country. This comparative advantage isnot new.

What

is new, following the Euro, is the abilityof Portuguese firms to raise funds in a Euro-wide capital market to finance their foreign acquisitions.

We

see theimage

thatcomes

out ofour descriptionofPortugueseevolu-tions as consistent with that

from

panel data regressions. It isone in whichintegration, especially financial integration (and integration rather than do-mestic financial liberalization) hasled to lowersaving,

and

toa lesserextent to higher investment, both leading to largercurrent account deficits.There

is however an alternative view ofthe current account deficit inPortugal, one based on loss ofcompetitiveness

and

overvaluation. It points to the decline in exports,due

to their unfavorable specialization: In 1995, onefourth oftotalexportswereaccountedforbyclothingand

footwear,some

of the products

most

exposed to competition from developing countries. Itsuggests that the rate at which Portugal joined the Euro, together with nominal rigidities, led to

an

overvalued exchange rate,and

in turn acurrent account deficit.Separating out the role of overvaluation

and

themechanisms

we

have focused on in this paper is far from obvious, both conceptuallyand

empir-ically.

But

we

see the overall evidence in favor of overvaluation as weak.First, lookingat it from the trade balanceside,

most

ofthe current accountdeficit is the reflection ofan unusually high growth rateofimports, rather than an unusually low growth rate of exports. Second, one would expect overvaluation,

and

so a lowdemand

for domestic goods, to be associated with unusually lowGDP

growth; this has not been the case. Third, the index of Portuguese unit labor costs, relative to 22 industrial countries (ascomputed

by theEU, European Economy,

Spring 2002, 1991=100),was

109.4 in 1995, 103.8 in 1998,

and

is 108 in 2002.(The

U.S. index from thesame

source, auseful comparison, increased in those yearsfrom 100 to 130).This suggests that overvaluation is at

most

a minor factor in explaining Portuguese current account deficits.3.2 Greece

Figure 8

shows

the evolution ofGreek

investmentand

saving, as ratios toGDP,

from 1981 to 2001. It shows that the divergence between investmentand

saving ismore

recent than in Portugal, dating back only to themid

1990s.

-©—

investment

30

25

20

15

1980

1985

1990

year

1995

2000

choice of a base period. Just as Portugal, Greece

went

through a recession in the mid-1990s, and using that period as the basewould

be misleading. Thus, in presenting numbers,we

divide time in three periods: 1981-1991 (1991 is the last year of sustained growth), with an average growth rate of 2.5%; 1992-1995, a period of slow growth, with an average growth rate of 0.8%,and

1996-2001, a period of sustained growth, with an average growthrate of3.5%.

To

show

recent evolutions,we

also presentnumbers

for 2000and

2001.When

reportingchanges,we

compare

thenumbers

for 2000-2001for those for 1981-1991.

Greeceisone ofthe countriesfor whichthe

numbers

reported by theEU

and

bytheOECD

differthe most.There

arebasicallytwo

time series forthe Greek current account balance.One

is the series reported by theBank

ofGreece,

and

usedby theOECD,

and

isbasedon informationon

internationaltransactionscollectedby commercialbanks.

The

other, usedin the national accountsand

by theEU,

isderivedfrom customsinformation.Both

sourceshave

become

less reliableover time: thefirstbecausethe removal ofcurrencyrestrictions has reduced the information available tocommercial banks; the

latter because of the gradual elimination of

custom

controls on intra-EUtrade.

We

report thetwo

sets ofnumbers

in the firsttwo

lines of Table2, but, for consistency with the

numbers

for the other variables, base therest ofour analysis (and Figure 8) on the

EU

numbers.While

the levels of the deficit according tothetwo sources arevery different, thechangein thedeficit isessentially the same: a widercurrent account deficitofaround

3%

ofGDP

(3.5% accordingto theEU, 2.5%

according to theOECD.)

The

numbers

in the table are adjusted for inflation in thesame way

asfor Portugal.11 Again, the adjustment mattersa lot:

The

inflation rate has"Estimates fromtheBankofGreece indicatethat, untilthemid-1990s, theproportion ofgovernment debt heldbynon-resident holderswaslow. It hasrecently increased, from

Current Account Deficits 32

decreased

from

18%

for 1981-1991, to12.5%

for 1992-1995,and

5%

since1996 (it stands around

3%

today); Gross public debt increased from50%

in1985 to

100%

ofGDP

in 1992,and

it has remained above100%

since.Table

2.Current

Account

Balance,

Investment,

and

Saving,

asratios

to

GDP,

percent.Greece 1981-2001

1981-91 1992-95 1996-2001 2000-01

A

Current account (EU-Nat

Def) -0.9 -0.2 -3.3 -4.4 -3.5 Current account(OECD-

BoG)

-4.0 -1.4 -4.6 -6.5 -2.5 Investment 22.9 19.7 21.3 23.0 0.1 Saving 22.0 19.5 18.2 18.6 -3.4 ofwhich Public saving 1.4 2.2 3.8 5.3 4.3 Private saving 21.0 17.3 14.4 13.3 -7.7 ofwhich 1995 1997 2000 Household saving 6.8 7.6 6.7 Corporate saving 10.7 7.0 6.4A

: Difference between2001-2000

and

1981-1991. Sources.European

Commission, Statistical

Annex

of"European

Economy"

, spring 2002.The

breakdown

of private saving between householdand

corporate saving wasgiven to us by the

Bank

of Greece.Figure 8

and

thenumbers

in Table 2 suggest four conclusions:•

The

increase in the current accountdeficitdoes notreflect an increasein investment.

The

ratio ofinvestmentin 2000-2001 isthesame

as inand later the

Euro

area, wasaccompanied

by an investmentboom

isonly the result of an inappropriate comparison with the recession of the early 1990s

and

the sharp fall in capital formation thathappened

then.

•

By

implication, all the increase in the current account deficit can be traced to a decrease in saving.The

current account deficit hasin-creased by 3.5%. Saving has decreased by

3.4%

•

The

decrease in saving ismore

than fully accounted for by an evenlarger decrease in private saving. Private saving has decreased by 7.7%, while public savinghas increased by 4.3%. This isverydifferent

from Portugal. There, as

we

saw

in Table 1, both privateand

public-saving have decreased. In Greece the swing in (inflation adjusted)

private saving has been twice as large as in Portugal but has been

partly offset by the increase in (inflation adjusted) public saving. •

The

decomposition between corporateand

household saving can onlybe

made

from 1995 on.Based

on this information, it appears thatmuch

of the decrease in private savingcomes

from a decrease inre-tained earnings, rather than a decrease in household saving, (again, the inflation correction is important here, as the inflation decreased from 9%, in 1995 to about

3%

in 2000,and

thedebt-to-GDP

ratioremained around 100%.

Absent

the inflation correction, the ratio of household saving toGDP

shows

a decline ofabout6%

from 1995 to2000).

We

now

look atsome

aspects ofthe story behind these numbers. There has indeed been a clear shift of firms from internal finance toshare issues.

The

flow ofcapital raised in thestock market went from zeroin 1995-1996 to