Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

Stopping Biologics in IBD-What Is the Evidence?

Edouard Louis, MD, PhD, from the Department of Gastroenterology, CHU Liège University Hospital, Liège, Belgium

Abstract

Biologic treatments have revolutionized the way we treat inflammatory bowel disease patients (IBD). Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) antibodies are superior to conventional therapies to achieve sustained remission without steroids and mucosal healing. The objective of IBD treatment has evolved from symptom alleviation to a combination of absence of symptoms and intestinal healing. Nevertheless, biologics are expensive and are associated with an increased risk of infections and possibly skin cancers. Therefore, the duration of these treatments may be questioned, and stopping them may be contemplated by some patients and clinicians, while it is sometimes even imposed by some jurisdictions across the world. In the present paper, I highlight the recent literature about outcomes after biologics withdrawal, patients' profiles associated with these outcomes, monitoring after withdrawal, and results of retreatment. We also introduce the concept of biologic treatment cycles in IBD.

Key Words: inflammatory bowel disease, biologic treatment, treatment withdrawal, disease relapse, biomarkers Supported by: This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation

program under grant agreement No. 633168—BIOCYCLE (PHC-13-2014).

Conflicts of interest: E. Louis has received research grants from Takeda, Pfizer; educational grants from

Abbvie, MSD, Takeda; has received speaker fees from Abbott, Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Ferring, MSD, Chiesi, Falk, Takeda, Hospira, Janssen, Pfizer; has been on the advisory board for Abbott, Abbvie, Ferring, MSD, Mitsubishi Pharma, Takeda, Celltrion, Celgene, Hospira, Janssen; has been a consultant for Abbvie.

INTRODUCTION

Biologics have revolutionized the way we treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Their ability to induce sustained remission and mucosal healing is superior to the conventional therapies, including immunomodulators.1-3 They have changed our conception of what can be achieved as a therapeutic objective. We

have thus gone from treating to alleviate symptoms to treating to normalize quality of life and induce intestinal healing to prevent the development of complications and the need for surgical resection. This has recently been very well formalized in the treat-to-target concept, which probably currently represents the best treatment strategy for IBD.4 However, biologics can't cure IBD, and therefore continuous treatment has been the rule to

avoid relapse and disease progression. Particularly, on-demand treatment, which was first tried with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) in the late 90s, proved to be ineffective and even deleterious for the patients through the appearance of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) in a significant proportion of patients, leading to acute infusion reaction and loss of response.5 In this setting, we may ask ourselves what would be the rationale to contemplate

stopping this kind of therapy. A comparison is often made with other chronic diseases, like diabetes or hypertension, where stopping therapy would never be considered. The aim of this review is to highlight recent literature emphasizing the potential consequences of long-term biologic treatment, including the risk of side effects, costs, disease evolution after biologic withdrawal, subgroup analyses indicating some low-risk and high-risk populations, and response to resuming biologic therapy. Finally, from this bulk of evidence may emerge the concept of cycles of biologic treatment aimed at a timely but time-limited use of biologics still compatible with a sustained steroid-free remission and absence of tissue damage progression. Very few data are available for biologics other than anti-TNF, and our review will mainly focus on anti-TNF. We are not considering here the situations where there is an obvious lack of efficacy and benefit for the patients or where treatment intolerance or toxicity should prompt treatment cessation.

ACHIEVEMENTS OF BIOLOGICS IN IBD

Biologics are superior to placebo to induce and maintain remission in IBD refractory to conventional therapies, including immunomodulators.1-3 They have shown an ability to heal the intestinal mucosa and to decrease the

risk of surgery and hospitalization.6,7 They also improve quality of life and are associated with an increased

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

They are usually well tolerated, and the majority of patients don't experience any relevant side effects. Prospective and retrospective studies have shown a superior efficacy compared with immunomodulators for all these end points.

Biologics are also nowadays considered safer, particularly than purine analogues, for which a significant increase in the risk of cutaneous and urinary tract cancers and lymphomas has consistently been reported.9,10

Thus it seems that today biologic treatments fit best with the concept of treat-to-target and are most appropriate to achieve sustained remission without steroids and decrease or suppress tissue damage progression, which is the priority in IBD.

REASONS FOR WITHDRAWAL

Biologics also have some drawbacks, and these drawbacks may call for withdrawal despite the assets described here above. These drawbacks may be categorized in different classes: patients' preferences and perception, biology of the disease and loss of response, side effects and risks, and finally costs.

Very few data are available on patient preference regarding withdrawal or continuation of biologic therapy. This is a field where specific studies are awaited. We can only analyze indirect evidence or generalities about treatment perception by patients suffering from chronic diseases. Adherence to long-term treatment in chronic disease is usually weak.11,12 Although adherence rate may be influenced by some demographic and sociologic

characteristics, it is thought to be mainly governed by a balance between perceived need for therapy and fear about toxicity13 In a patient who has been in mid- long-term remission under a biologic treatment, the perceived

need may decrease while the fear for toxicity may increase, leading to a trend to stop therapy. Even if patients' education may help to decrease this trend, it will not completely disappear. The need to go to the hospital or to an infusion clinic or even the need to inject a drug subcutaneously may reinforce this trend, although recent data have suggested higher adherence to injectable biologic therapy compared with oral immunomodulators in IBD, potentially linked to a higher perceived need with biologics.14

The impact of biologics on the biology of the disease process and the pathways of inflammation has not been adequately studied. Nevertheless, a change in the biology of inflammation has been observed over the disease course15 and is a potential reason for loss of response in patients still having high trough levels of the drug, no

ADA, and no complication.16 Such a change in the inflammation process may also explain why some patients

nonresponding or losing response to anti-TNF may become responders later on.17 The development of

paradoxical inflammation in some patients has also been described18 as a potential sign of change of the

biological process of the disease. Some patients may also develop rapid clearance of the therapeutic antibody and antidrug antibodies while still being treated without interruption.19 Whether timely planned therapeutic windows

would allow prevention of such evolution is unknown but should be tested. Even if treatment cessation has been shown to be immunogenic, it was in some specific circumstances, including on-demand treatment, or after treatment secondary failure or side effects. Whether the same effect would be observed in case of long-term sustained remission and whether it would occur more often than when continuing the drug have still to be demonstrated. Particularly, in the STORI trial, among the patients relapsing after infliximab withdrawal and being retreated with infliximab, no one developed ADA.20 Likewise, in a prospective cohort of infliximab-treated

patients, the development of ADA was mainly observed during the first year of treatment, highlighting the fact that this tends to be an early phenomenon and that beyond this stage, the risk seems significantly lower.21

Another aspect to consider is the need for constant immu-nomodulation in IBD. IBDs were initially described as chronic relapsing diseases with alternating periods of clinical flare and remission. As clearly illustrated by the natural history after "curative" ileo-caecal resection in Crohn's disease (CD), up to 40% of the patients may experience no relapse over an 8-year period of time, thus showing the absence of the need of constant immune-modulation in some CD patients.22 The currently available biologics are able to put a subset of patients in

longstanding clinical and endoscopic remission, thereby mimicking what can be achieved with "curative" surgery. It is therefore possible that after having reached a state of prolonged clinical and endoscopic remission, a subset of patients may conserve this state without treatment for a prolonged time. This has been suggested in several withdrawal studies with either immunomodulators or biologics where 20%-40% of the patients did not experience relapse over follow-up of several years.23

Even if biologics were revealed to be globally very well tolerated and reasonably safe, some patients may experience mild to moderate side effects, and some long-term risks are well established. Even if mild to moderate side effects are not sufficient to decide treatment withdrawal, they may interfere with quality of life, and in a holistic approach, they would be an argument for treatment withdrawal. Among these mild to moderate side effects, best documented are skin lesions. Skin lesions under anti-TNF have been documented in up to 20% of patients.24

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

They include dry skin, itching, and more severe lesions like psoriasiform and eczematiform eruptions or palmo-plantar pustulosis. Some of these manifestations may respond to local treatment, but they also can be very debilitating and can be an argument for treatment withdrawal in 2%-5% of patients.25

Other side effects often put forward by the patients, like fatigue, tiredness, and muscular or joint pain, are much more difficult to substantiate, and there is no evidence that treatment withdrawal would improve the situation, although some of these symptoms have been associated with higher biologic trough levels in patients in remission.26 Again, from the patients' perspective, they may represent an argument to contemplate biologic

withdrawal. Well-established long-term risk includes the risk for severe and opportunistic infections,27 whereas

the increased risk of melanoma and other skin cancers has recently been questioned.28 The risk of severe and

opportunistic infection, including intracellular bacteria and tuberculosis, has been very well documented in registries and real-life practice. Appropriate screening, preventive measures, and vaccination programs may decrease this risk, but these programs are not infallible and adherence to them is imperfect.29

Although the risk of melanoma may be lowered by preventive measures and regular surveillance, these are sometimes difficult to apply and not very well followed by young patients who may want to enjoy all aspects of modern life including travel and sun exposure. The risk of lymphoma has been once suspected but never fully demonstrated, and more recently has been associated with purine co-treatment. An increased risk of solid tumors has never been firmly demonstrated with biologics.30

The problem of cost is probably not something we should discuss on an individual basis, but rather at a general health care policy level. Nevertheless, in some jurisdictions or for some patients for whom insurance or national health care coverage is absent or insufficient, cost at the individual level may become an issue. From this point of view, and even if the advent of biosimilars has significantly decreased the cost, biologics' cost remains much higher than for immunomodulators, particularly purine analogues. This is a complex issue, as most available data mainly concern direct costs and are based on models and not real-life data.31 These data showed a

cost-effectiveness for anti-TNF in CD and more recently in ulcerative colitis (UC), but when considering long-term maintenance, cost-effectiveness was not guaranteed beyond 1 to 4 years of treatment. Hence in some European countries, the continuation of an anti-TNF beyond 1 year of therapy has to be strongly justified to get reimbursement. What real-life data have recently shown is that biologics nowadays represent a big part of the direct cost in IBD care, around two-thirds in CD and one-third in UC32 Particularly in CD, where the direct cost

of management has not globally increased over the last decade, the cost of biologics has actually replaced the cost of hospitalizations and surgeries, which has decreased. This is good news for patients and the society, but it emphasizes the fact that the cost of biologics is significant for the health care system and that the most appropriate use of them is important. While earlier use of biologics in a growing number of IBD patients has been advocated to increase sustained steroid-free remission and decrease the risk of tissue damage progression,33

to keep cost at a reasonable level, we may question the duration of therapy. It is probably a better use of available money to treat a significant proportion of IBD patients earlier but for a limited period of time than to treat the most severe patients later, without hope of treatment discontinuation because the disease is too severe and tissue damage accumulation strongly impacts patients' quality of life.

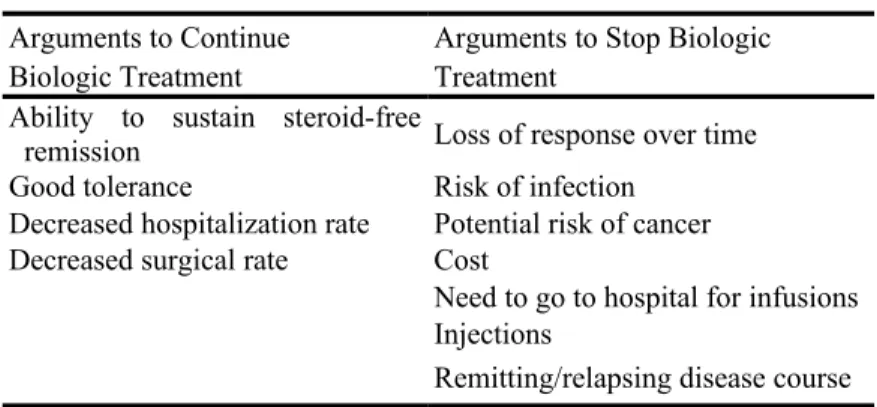

Arguments to stop or to continue biologic treatment in patients in sustained steroid-free remission are illustrated in Table 1.

CONSEQUENCES OF WITHDRAWAL

There is no published controlled trial comparing biologic continuation with withdrawal in patients with sustained remission, although several are currently ongoing. However, the data coming from prospective cohorts suggest an increased risk of relapse when compared with historical cohorts of patients who were continuously treated. In UC, this is confirmed by a retrospective comparison of stoppers vs non stoppers within a unique cohort of patients.34 In patients continuously treated with anti-TNF, the annual rate of secondary loss of response has been

estimated at 10%-15%.35 In different prospective cohorts of patients in whom anti-TNF was stopped while in

sustained remission, the relapse rate was around 40% at 1 year and 50% at 2 years.36-41 The same numbers were

observed in CD and UC patients. Retreatment with the same biologic, most often infliximab, has been associated with variable success, going from below 50% with a high risk of infusion reaction to almost 90% success.42-15

This heterogeneity may reflect the heterogeneity of the cohorts and the retreated patients. In cohorts where biologic therapy was electively stopped while the patient was in sustained steroid-free remission, the response rate to resuming the same treatment was usually very high and the development of ADA, when it was measured, was very rare.20,42-45 This may reflect the selection of a subgroup of patients who are the best responders to this

biologic therapy, as already suggested by their longstanding stable remission. Those patients are probably not prone to developing ADA against the considered biologic.

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

Interestingly, in other diseases and with other biologies, genetic predispositions have been demonstrated to be associated or not with the development of ADA.46,47 On the contrary, more infusion reactions and lower success

rates were reported from a cohort incorporating patients having stopped infliximab because of loss of response, because of side effects, on their own decision, and not necessarily in sustained remission.44,45

Another aspect that may have influenced the relapse rate and the response to retreatment is the immunomodulatory cotreatment. This has mainly been associated with a better response rate to retreatment and less infusion reactions, maybe also partly reflecting less ADA development.44

One important aspect to consider is the rate of early surgical resection after relapse. This was low in CD,20,36-38

whereas a colectomy rate around 20% among the relapsers was reported over 1 year in UC40 This emphasizes the

fact that the consequences may be more severe in UC than CD.

TABLE 1: Arguments to Stop or Continue Biologic

Treatment

Arguments to Continue Arguments to Stop Biologic

Biologic Treatment Treatment

Ability to sustain steroid-free

remission Loss of response over time

Good tolerance Risk of infection

Decreased hospitalization rate Potential risk of cancer

Decreased surgical rate Cost

Need to go to hospital for infusions Injections

Remitting/relapsing disease course

Very few reports were published on the long-term outcome after withdrawal. The long-term follow-up of the STORI cohort was recently reported.48 It showed that only 20% remained free of biologics, surgical resection,

and new complex perianal lesions over a median follow-up of 7 years. However, the majority of patients who resumed infliximab or another biologic treatment remained under this biologic treatment without major complications over time. Only around 20% of the patients over 7 years required surgical resection or developed complex perianal disease. Overall, the high rate of remission after resuming treatment, the low rate of ADA development (at least over the short term) and infusion reaction, and the relatively low rate of long-term major complication may counterbalance the relatively high rate of relapse after withdrawal and make it possible to contemplate such withdrawal, at least in a subset of patients.

IN WHICH PATIENTS TO STOP/HOW TO DECIDE

Globally, the clinical results after withdrawal of biologics may seem unsatisfactory as the relapse rate seems to be by far superior to the one observed in continuously treated patients. However, in several prospective as well retrospective cohorts, consistent risk profiles were disclosed.20,36-41,49 Among the most broadly confirmed factors

were the presence of mucosal healing, normalization of the CRP, and lowering of fecal calprotectin in CD. Other predictors seem more specific to particular cohorts, including sex, age, duration of disease, and previous failure of immunomodulators. Another interesting predictor for a favorable outcome after stopping was a low trough level of infliximab. This was shown both in multivariable (but not univariable) analysis in STORI20 and in

another independent French-Israeli cohort.50 In the STORI trial, the low-risk group, representing one-fourth to

one-third of the patients, had a 10%-15% risk of relapse over 1 year, which is very close to the risk of relapse in the patients continuing infliximab scheduled maintenance in historical cohorts.20 Interestingly, also in STORI,

the risk factors of short-term relapse were different from those of long-term major complication development.20, 48 Apart from some specific clinical or demographic characteristics, the factors predicting short-term relapse

were mainly surrogate markers for ongoing disease activity despite clinical remission (endoscopic lesions, fecal calprotectin, CRP), while the factors predicting long-term major complications (surgical resection, new complex perianal disease) were the presence of upper gastro-intestinal tract lesions, lower hemoglobin, and higher white cell count, the last probably reflecting inefficacy, insufficient dosage, or low adherence to the immunomudulator. If confirmed in prospective controlled studies, these parameters may help to stratify patients and contribute to decision-making as whether to continue or stop biologics. On the contrary, no consistent predictor of relapse was found in UC, where even mucosal healing was not associated with a lower risk of relapse.40

steroid-Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

free remission is a complex one, which has to take into account benefit/ risk and benefit/cost balance.36

Predictors of short-term relapse and long-term complications are only a few of the elements that should be integrated in this decision-making process. The parameters potentially involved in the decision-making process have recently been reviewed, and it was proposed to integrate them in a multidimensional figure to help decision-making.36

Among others, important parameters include patient history, including previous surgeries, disease severity, and treatment failures; the current disease situation, including intestinal healing; the age of the patient; the risk profile for side effects; treatment tolerance; comorbidities; and, last but not least, patient preference. This last point, albeit highly subjective, is important to take into account. Clinical practice highlights the fact that priorities may differ from patient to patient, some privileging safety and fearing above all drugs' side effects, others privileging the full disease control and accepting some degree of treatment-related risk.51 Examples of

patients' profiles in whom the treatment could be stopped or should be continued are illustrated in Table 2. To these medical aspects should be added the jurisdiction and health care insurance system, in the context of which this decision has to be made. Indeed, the money globally available to manage IBD patients and the cost of specific medical or surgical procedures in specific jurisdictions may determine different optimal strategies. Ultimately, when a decision has to be made, the difficulty will be to weigh the different parameters to select a balanced and appropriate option. To this end, mathematical models, integrated in clinical decision support system like the ones used in other chronic diseases, may reveal what is necessary. 52,53

HOW TO MANAGE POSTWITHDRAWAL/WHICH TREATMENT TO RESUME AND HOW

As highlighted in the previous paragraph, the relapse rate after biologic withdrawal is approaching 40%-50% over 1-2 years. In the published prospective cohorts, most of these patients have been retreated with the same biologic. Results of this retreatment have varied, some patients not responding very well and some even requiring surgical resection. There are thus at least 2 important questions here: first, is it possible to predict clinical relapse to potentially retreat the patients before it occurs, thereby avoiding the deleterious consequences?; second, what is the best retreatment option? Very few data have been published on the longitudinal follow-up of patients in whom a biologic has been stopped. In the STORI trial, blood C-reactive protein (CRP) and fecal calprotectin were measured every 2 months after infliximab withdrawal.54 A significant

increase in CRP and fecal calprotectin was observed in future relapsers up to 4-6 months before the relapse.

TABLE 2: Examples of Patient Profiling to Take Decision of Biologic Continuation or Withdrawal While in Sustained Clinical Remission

Profile Favoring Treatment Continuation Profile Favoring Treatment Withdrawal

Medical reasons

Young patient with previous extensive or complicated

Crohn's disease (abscess, stricture, surgical resection...) Older patient* with Crohn's disease without previous complication or surgeryand without endoscopic lesion or elevation of CRP or fecal calprotectin Patients with previous complex perianal Crohn's disease Older patienta with ulcerative colitis with previous distal colitis

Patient with previous extensive ulcerative colitis Patient with mild-moderate side effects of the biologic treatment

Crohn's disease patient with persisting endoscopic lesions or

elevated CRP and/or fecal calprotectin Patients with comorbidities increasing the risk of infection

Patients with prior surgeries Patient with absence of residual trough level

Nonmedical reasons

Patient fearing more complications of the disease than the

side effects of treatment Absence of drug reimbursement by insurance or health care system

Patient with low adherence to treatment

Patients having difficult access to infusion center

aThere is no strict, uniformely accepted threshold, but infection and cancer risks certainly increase beyond 60 years of age.

This elevation of fecal calprotectin has been confirmed in a more recent prospective cohort, and it occurred a median of 3 months before the relapse.42 This may suggest that regular monitoring of these biomarkers may help

to select patients for early retreatment. A limitation to this monitoring is the absence of specificity of an isolated elevation of fecal calprotectin. Hence, the significance and the relevance of an elevation of calprotectin in 2 successive measurements may be higher.55

As far as the best retreatment option, here also prospective controlled data comparing retreatment strategies are lacking. Should one favor the same biologic, or switch? Should one re-induce or simply resume maintenance

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

treatment? Should the re-induction scheme be similar to the first induction?56, 57 All these important questions,

among others, are without clear answer. Also, the optimal retreatment scheme may differ if one preventively retreats the patient based on an elevation of the biomarkers or if one retreats the patient after a clinical relapse. The only thing that has been suggested is that the better outcome when patients were retreated with the same biologic, essentially infliximab in the available data, was seen when retreatment was combined with an immunomodulator, particularly when this immunomodulator was also maintained between the 2 infliximab treatment sequences.44,57

CONCEPT OF CYCLES OF BIOLOGIC TREATMENT

The biologics currently available to treat IBD, as well as the ones currently in phase 2 or 3 trials, don't have the ability to cure the disease. The genetic predisposition and probably some immunological, microbiome, and barrier function disturbances are still present and may trigger a relapse over time. Therefore, in most of the cases, the biologic withdrawal will not be definitive but rather for a variable period of time between 2 cycles of biologic therapy. Whether this temporary withdrawal is beneficial for the patient and cost-saving for the health care insurance or health care system may depend on the duration for which the drug can be stopped and the frequency of development of complications, and our ability to avoid them by proactive monitoring and early retreatment in case of elevation of biomarkers suggesting a high risk of clinical relapse. At this moment, this kind of temporary interruption of biologic treatment should be reserved for patients having reached full mucosal healing and having had an uncomplicated disease history thus far,49 because the priority in the management of

IBD is still the full control of the disease, preventing the long-term consequences of disease activity, including abscesses, fistula, and fibrotic strictures in CD and cancer in CD and UC.4

Whether it would make sense to repeat temporary interruptions over time in patients in full clinical and endoscopic remission with a new cycle of therapy with biologics is speculative. No data are available with such successive interruptions and cycles of treatment. However, the multiplication of available therapies to treat IBD and the advent of effective monitoring tools to detect preclinical disease activity may make us more comfortable in the future with such a strategy as the main fears are the loss of response following a temporary interruption on the one hand and tissue damage progression on the other.

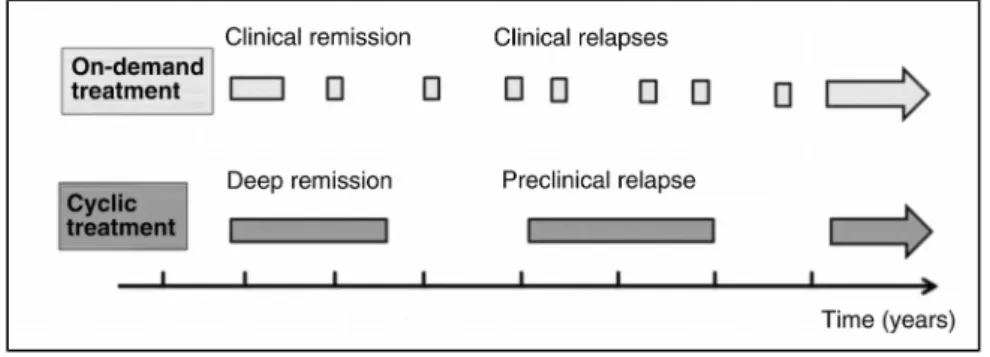

The concept of cycles of biologic treatment and its comparison with on-demand treatment are illustrated in Figure 1.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the high level of benefit associated with biologic treatment in IBD, long-term safety, cost, and natural history of IBD justify contemplation of treatment withdrawal. Current evidence suggests a high risk of early relapse after withdrawal and highlights the fact that this strategy can't be generalized.

FIGURE 1. On-demand vs cycles of biologic treatment. The first and undisputable aim of IBD treatment is full

disease control. The idea of cyclic treatment is to aim at the lowest biological use still compatible with full disease control. Treatment withdrawal is only contemplated when sustained remission without steroids and with mucosal healing has been achieved (deep remission). The patient is then proactively monitored with biomarkers. The treatment is restarted for a new cycle when biomarkers indicate an increased risk of relapse (preclinical relapse).

Nevertheless, low-risk patients have been identified, and retreatment appears safe and effective in the vast majority of them, suggesting that some kind of biologic treatment cycles could be contemplated in those patients. While the results of the ongoing controlled trials are eagerly awaited to confirm outcomes and predictors,

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

stopping biologics should be reserved in patients having reached prolonged steroid-free clinical and endoscopic remission and without previously accumulated tissue damage in CD and in patients with strong risks associated with treatment continuation in UC.

REFERENCES

1. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383-95.

2. Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392-400.

3. Walters TD, Kim MO, Denson LA, et al. Increased effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:383-91. 4. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease

(STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-8.

5. Rutgeerts P, D'Haens G, Targan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:761-9.

6. Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn's disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1825-34.

7. Olivera P, Spinelli A, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Surgical rates in the era of biological therapy: up, down or unchanged? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:246-53.

8. Louis E, Löfberg R, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab improves patient-reported outcomes and reduces indirect costs in patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease: results from the CARE trial. J Crohns

Colitis. 2013;7:34-43.

9. Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617-25.

10. Bourrier A, Carrat F, Colombel JF, et al. Excess risk of urinary tract cancers in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther. 2016;43:252-61.

11. Severs M, Mangen MJ, Fidder HH, et al. Clinical predictors of future nonadher-ence in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1568-76.

12. Testa A, Castiglione F, Nardone OM, Colombo GL. Adherence in ulcerative colitis: an overview. Patient

Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:297-303.

13. McHorney CA, Spain CV. Frequency of and reasons for medication non-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008. Health Expect. 2011;14:307-20.

14. Michetti P, Weinman J, Mrowietz U, et al. Impact of treatment-related beliefs on medication adherence in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: results of the global ALIGN study. Adv Ther. 2017;34:91-108. 15. Veny M, Esteller M, Ricart E, et al. Late Crohn's disease patients present an increase in peripheral Th17

cells and cytokine production compared with early patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:561-72.

16. Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, et al. Changes in serum trough levels of infliximab during treatment intensification but not in anti-infliximab antibody detection are associated with clinical outcomes after therapeutic failure in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:238-45.

17. Brandse JF, Peters CP, Gecse KB, et al. Effects of infliximab retreatment after consecutive discontinuation of infliximab and adalimumab in refractory Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:251-8.

18. Wendling D, Prati C. Paradoxical effects of anti-TNF-α agents in inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev Clin

Immunol. 2014;10:159-69.

19. Qiu Y, Chen BL, Mao R, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: loss of response and requirement of anti-TNFα dose intensification in Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:535-54.

20. Louis E, Mary JY, Vernier-Massouille G, et al. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn's disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:63-70.e5; quiz e31.

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

21. Ungar B, Chowers Y, Yavzori M, et al. The temporal evolution of antidrug antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Gut. 2014;63:1258-64.

22. Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, et al. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn's disease.

Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956-63.

23. Lémann M, Mary JY, Colombel JF, et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled withdrawal trial in Crohn's disease patients in long-term remission on azathioprine. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1812-8.

24. Cleynen I, Van Moerkercke W, Billiet T, et al. Characteristics of skin lesions associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:10-22.

25. Rahier JF, Buche S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Severe skin lesions cause patients with inflammatory bowel disease to discontinue anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:1048-55.

26. Brandse JF, Vos LM, Jansen J, et al. Serum concentration of anti-TNF antibodies, adverse effects and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission on maintenance treatment. J Crohns

Colitis. 2015;9:973-81.

27. Minozzi S, Bonovas S, Lytras T, et al. Risk of infections using anti-TNF agents in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:11-34.

28. Mercer LK, Askling J, Raaschou P, et al. Risk of invasive melanoma in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics: results from a collaborative project of 11 European biologic registers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:386-91.

29. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:443-8.

30. Bonovas S, Minozzi S, Lytras T, et al. Risk of malignancies using anti-TNF agents in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:35-54.

31. Bodger K, Kikuchi T, Hughes D. Cost-effectiveness of biological therapy for Crohn's disease: Markov cohort analyses incorporating United Kingdom patient-level cost data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:265-74.

32. van der Valk ME, Mangen MJ, Leenders M, et al. Healthcare costs of inflammatory bowel disease have shifted from hospitalisation and surgery towards anti-TNFα therapy: results from the COIN study. Gut. 2014;63:72-9.

33. D'Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660-7.

34. Fiorino G, Cortes PN, Ellul P, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis is associated with increased risk of relapse: a multinational retrospective cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 2016;14:1426-32.el.

35. Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760-7.

36. Torres J, Boyapati RK, Kennedy NA, et al. Systematic review of effects of withdrawal of immunomodulators or biologic agents from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1716-30.

37. Gisbert JP, Marín AC, Chaparro M. The risk of relapse after anti-TNF discontinuation in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:632-47.

38. Kennedy NA, Warner B, Johnston EL, et al. Relapse after withdrawal from anti-TNF therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: an observational study, plus systematic review and meta-analysis. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:910-23.

39. Clarke K, Regueiro M. Stopping immunomodulators and biologics in inflammatory bowel disease patients in remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:174-9.

40. Farkas K, Lakatos PL, Nagy F, et al. Predictors of relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission after one-year of infliximab therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1394-8.

Status : Postprint (Author’s version)

41. Steenholdt C, Molazahi A, Ainsworth MA, et al. Outcome after discontinuation of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission: an observational Danish single center study. Scand J

Gastroenterol. 2012;47: 518-27.

42. Molander P, Färkkilä M, Salminen K, et al. Outcome after discontinuation of TNFα-blocking therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in deep remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1021-8.

43. Brooks AJ, Sebastian S, Cross SS, et al. Outcome of elective withdrawal of anti-tumour necrosis factor-α therapy in patients with Crohn's disease in established remission. J Crohns Colitis 2015;11:1456-62.

44. Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, et al. Early trough levels and antibodies to infliximab predict safety and success of reinitiation of infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1474-81.

45. Felice C, Pugliese D, Guidi L, et al. Retreatment with infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: tolerability and effectiveness of different re-induction regimens. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(Suppl 1):P363.

46. Link J, Lundkvist Ryner M, Fink K, et al. Human leukocyte antigen genes and interferon beta preparations influence risk of developing neutralizing anti-drug antibodies in multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90479. 47. Ungar B, Haj-Natour O, Kopylov U, et al. Ashkenazi Jewish origin protects against formation of antibodies

to infliximab and therapy failure. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e673.

48. Reenaers C, Nachury M, Bouhnik Y, et al; on behalf of GETAID. Long-term outcome after infliximab withdrawal for sustained remission in Crohn's disease. UEG Journal. 2015;(Suppl 5):OP93.

49. Gisbert JP, Marin AC, Chaparro M. Systematic review: factors associated with relapse of inflammatory bowel disease after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:391-405.

50. Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Ungar B, et al. Undetectable anti-TNF drug levels in patients with long-term remission predict successful drug withdrawal. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:356-64.

51. Thompson KD, Connor SJ, Walls DM, et al. Patients with ulcerative colitis are more concerned about complications of their disease than side effects of medications. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:940-7.

52. Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:1223-38.

53. Moja L, Kwag KH, Lytras T, et al. Effectiveness of computerized decision support systems linked to electronic health records: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:el2-e22. 54. de Suray N, Salleron J, Vernier-Massouille G, et al. Close monitoring of CRP and fecal calprotectin levels

to predict relapse in Crohn's disease patients. A sub-analysis of the STORI study. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(Supp 1):P274.

55. Zhulina Y, Cao Y, Amcoff K, et al. The prognostic significance of faecal calprotectin in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:495-504.

56. Gagniere C, Beaugerie L, Pariente B, et al. Benefit of infliximab reintroduction after successive failure of infliximab and adalimumab in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:349-55.

57. Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Garciá-Sánchez V, et al. Evolution after anti-TNF discontinuation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter long-term follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:120-31.