To link to this article: DOI: 10.1016/j.msea.2011.06.044

URL :

ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2011.06.044

This is an author-deposited version published in:

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID: 5668

To cite this version:

Marder, Rachel and Chaim , Rachman and Chevallier, Geoffroy and

Estournès, Claude Densification and polymorphic transition of multiphase

Y2O3 nanoparticles during spark plasma sintering. (2011) Materials

Science and Engineering A, vol.528 (n° 24). pp. 7200-7206. ISSN

0921-5093

O

pen

A

rchive

T

oulouse

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers

and makes it freely available over the web where possible.

Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes.diff.inp-toulouse.fr

Densification

and

polymorphic

transition

of

multiphase

Y

2

O

3

nanoparticles

during

spark

plasma

sintering

R.

Marder

a,

R.

Chaim

a,∗,

G.

Chevallier

b,

C.

Estournes

baDepartmentofMaterialsEngineering,Technion–IsraelInstituteofTechnology,Haifa32000Israel bCNRS,InstitutCarnotCirimat,F-31602ToulouseCedex9,France

Keywords:

Sparkplasmasintering Phasetransformation Densification Y2O3

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Multiphase(MP)monoclinicandcubicY2O3nanoparticles,40nmindiameter,weredensifiedbyspark

plasmasinteringfor5–15minand100MPaat1000◦C,1100◦C,and1500◦C.Densificationstartedwith

pressureincreaseatroomtemperature.Densificationstagnatedduringheatingcomparedtothehigh shrinkagerateincubicsingle-phasereferencenanopowder.ThelimiteddensificationoftheMP nanopow-deroriginatedfromthevermicularstructure(skeleton)formedduringtheheating.Interfacecontrolled monoclinictocubicpolymorphictransformationabove980◦Cledtotheformationoflargespherical

cubicgrainswithinthevermicularmatrix.Thisresultedinthelossofthenanocrystallinecharacterand lowfinaldensity.

1. Introduction

Rapidsinteringanddensificationofceramicpowderstofull den-sityare nowadaysa routineprocedure, usingthespark plasma sintering (SPS) method.As wasnoted in many hot-press stud-iesincludingSPS,themaindensificationshrinkageofthepowder aggregatetakesplaceduringtheheatingbyparticlesliding,tothe close-packedarrangement[1–4].Furtherdensificationofthe pow-dercompactmaybeaccomplishedeitherbyplasticdeformation orbydiffusionalprocesses,attheparticlenecks.Nevertheless, dif-fusionalprocessesareinevitableduringthefinalstagesintering, whenisolatedporesformandcanbeeliminatedviabulkorgrain boundarydiffusion[5,6].Consequently,microstructureevolution duringtheSPSprocess,duetothechangeintheprocess param-eters,such astemperature,pressure,time,atmosphere, vacuum level, etc. mayaffectthe densificationmechanism. Many types ofphasetransformationsandtransitions associatedwithcrystal symmetrychangesinvolvechangesinthemicrostructureand mor-phology[7].Therefore,effectsofthephasetransformationsduring thedensificationbySPSmaybeofprimeimportancetothe densifi-cationprocess,aswellastothefinalphaseassemblageinthedense compact.Thephasecontentandassemblageoftenhavea consid-erableimpactonthefinalpropertiesofthesinteredceramic[8]. Inthisrespect,Takeuchietal.[9]investigatedthedensificationof

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+97248294589;fax:+97248295677. E-mailaddress:rchaim@technion.ac.il(R.Chaim).

submicrometersizetetragonalBaTiO3 powdersandfoundSPSto

beeffectiveforpreservationofthesubmicrometersizemetastable cubicBaTiO3atroomtemperature.Thepreservednanometricgrain

sizebySPSwasalsofoundtobeacauseforthecubicphase stabi-lizationatlowertemperatures[10,11].

Kumaretal.[12]tookadvantageofthehigheratomic mobil-ityneartheAnatasetoRutilephasetransformationtemperatureto enhancethedensificationoftheTiO2 nanoparticles.SPSof

mul-tiphaseTiO2 (70%Anatase and30% Rutile)with20-nmparticle

sizeat 62MPafor 5minand600◦C resultedincomplete phase

transformationtoRutile[13].Forcomparison,onlyannealingof the same precursor powder for 5min at 600◦C preserved the

multiphasecharacter ofthe powder.This exhibitstheeffect of theappliedpressureandpossiblytheelectricfieldonthephase transformationduringtheSPS.Fundamentalinvestigationofthe currenteffectonsolid-statereactivityduringSPSwasperformed onstackedMo–Si–Molayers[14].Nochangeinthereaction mecha-nismwasobserved,albeittheenhancedgrowthrateofthereaction productlayer(MoSi2),whichwasrelatedtotheenhancedmobility

orthechangeinthedefectconcentration.

The present paperfocuses on theeffect ofthe polymorphic phasetransitiononthemicrostructureanddensificationbehavior ofmultiphaseY2O3nanoparticlesduringtheSPS.

2. Experimental

Commercial pure (99%) multiphase (MP) Y2O3 nanopowder

(NeomatCo.,Riga,Latvia)withaverageparticlediameterof40nm

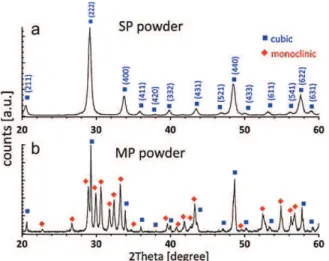

Fig.1.X-raydiffractionspectrafromtheY2O3nanoparticles.(a)Singlephase(SP)

cubic.(b)Multiphase(MP)cubic+monoclinic.

wasused.Asecondhighlypure(99.99%)nc-Y2O3powder(Cathay

AdvancedMaterials,China)with100%cubicphase,designatedas singlephase(SP),wasalsousedasareferencespecimen[15]. Con-stantamountofthepowdersamplewaspouredintothegraphite dieusinggraphitefoils(Grafoil)toseparatebetweenthepowder, thediewalls and theplungersurfaces.Thepowders were sin-tered(Dr.Sinter,SPS2080)atdifferentconditionsfor5–15minand 100MPaat1000◦C,1100◦C,and1500◦C.Thestartingtemperature

wasroomtemperatureforthe1000◦Ctreatment(designated‘cold

compaction’),but600◦Cforthe1100◦C and1500◦Ctreatments

(designated‘hotcompaction’).Theuniaxialpressurewasapplied eitherafewsecondaftertheprocessstartedorwhentheSPS tem-peraturewasreached.Inbothcases,thepressurewasincreased linearlywithtime,andheldconstantduringtheisothermal treat-mentattheSPStemperature.Theprocessdurationreferstothe isothermalSPStreatment.Aheatingrateof100◦C/minand

vac-uumlevelof3Pahasbeenused;thepulsedurationwas3.3ms.The SPSparameterswererecordedduringtheprocess.The tempera-turewascontrolledbyathermocouplefor‘coldcompaction’,while anopticalpyrometerwasusedabove600◦Cfor‘hotcompaction’

andathighertemperatures.Thefinalspecimendimensionswere 8mmindiameterand1.7–2.5mmthick.Theramdisplacements wereexpressedintermsofthelinearshrinkageandthetemporary relativedensity,followingthespecimenthicknessversustime, tak-ingintoaccountthethermalexpansion/shrinkagebehaviorofthe specimenandthegraphiteplungers[15].

Thephasecontentoftheas-receivednano-powdersandthe sin-teredspecimenswerecharacterizedbyX-raydiffractionusinga diffractometer(PhilipsPW3710)withmonochromaticCuKa

radi-ation (XRD),operatedat 40kVand 30mA.A scanningspeed of 0.5◦/minhasbeenused.Themicrostructureswerecharacterized

usingtransmission(TEM,FEITecnaiG2T20,operatedat200kV) andscanning(FEIE-SEMQuanta200,operatedat20kV)electron microscopes.Thespecimensfortheelectronmicroscopy observa-tionswereprepared bytheconventionalmethods.Thethermal stabilityofthenanopowderswascharacterizedusingdifferential scanningcalorimetry(Labsys1600,Setaram)upto1400◦CinArgon

atmosphere,ataheatingrateof5◦C/min.Thefinaldensityofthe

specimenswasdeterminedbytheArchimedesmethodfollowing ASTMstandardC20-92(±0.5%accuracy).

3. Results

X-raydiffractionspectrafromtheas-receivednanopowdersare showninFig.1.Thesinglephase(SP)Y2O3nanopowderwithcubic

symmetry(JCPDS41-1105)wascharacterizedindetailelsewhere [16](Fig.1a),whereasthemultiphase(MP)nanopowderrevealed polymorphswithcubicandmonoclinic(JCPDS39-1063) symme-tries(Fig.1b).Quantitative analysis ofthe spectrum inFig. 1b, assumingapowdermixture[17],resultedin30%cubicand70% monoclinicphaseinthenanopowder.Theseresultswerein agree-mentwiththe25:75cubictomonoclinicphaseratiodetermined byothers[18].

TEMobservationofthetwopowders(notshownhere)exhibited sphericalmorphologyforthemultiphasepowder,comparedtothe equiaxedpolyhedralshapeforthecubic,singlephasepowder[16]. Bothpowdersexhibitedlog-normalgrainsizedistributions,with averagegrainsizeof18±8nmand41±22nmforthesinglephase andthemultiphasepowders,respectively.

XRDspectrafromtheMPnanopowdercompacts,subjectedto SPSfor5minat100MPaandatdifferenttemperatures(Fig.2a), showedthe transformation of themetastable monoclinic poly-morphtothestable cubic phase tooccurat1100◦C. However,

further XRD characterization of the MP nanopowders sintered fordifferentdurationsat1000◦Cand100MPa(Fig.2b)revealed

the continuous nature of the phase transformation kinetics alreadyatthistemperature.Themonoclinictocubicpolymorphic phasetransformationwasnotcompleted,evenafter15minSPS duration.

Following the above phase transformation in the sintered specimens,thethermalstabilityofbothnanopowderswere char-acterizedbyDSC(Fig.3).Atthestagewherethefiner,cubicSP nanopowderwasrelativelystable,thecorrespondingcurvefrom

Fig.2.XRDspectraoftheas-receivedMPY2O3nanoparticles,aftersintering(a)for

Fig.3.DifferentialscanningcalorimetryfromnanocrystallineY2O3.(a)Singlephase

(SP)cubic.(b)Multiphase(MP)cubic+monoclinic.

theMPnanopowderexhibitedastrongexothermicpeakstarting at∼980◦C,withthemaximumaround1200◦C.Thisisin

agree-mentwiththeexpectedmonoclinictocubicphasetransformation reportedat∼950◦C[19],andinagreementwiththeXRDresults.

Therefore,specialattentionwaspaidtothisphasetransformation duringthedensificationbySPS.

Followingthedensificationbehaviorofthetwonano-powders, severalimportantfeatureswereobserved.First,averyrapid com-pactionoftheMPpowderwasdirectlyassociatedwiththepressure whenappliedatroomtemperature(Fig.4a);thisroom tempera-turecompactionwiththepressureincreasepersistedforallSPS temperaturesinvestigated.However,furtherdensificationat ele-vatedtemperaturesdependedonthefinalSPStemperature.Inthe 1000◦C‘coldcompaction’treatment(Fig.4a),thedensityincreased

Fig.4.Relativedensity–time–temperature–pressuredependenciesduringSPSof (a)MPand(b)SPY2O3nanoparticlesat1000◦Cfor5minand100MPa.

simultaneouslywiththepressureincreasefromroomtemperature (i.e.SPSstartingtime),andleveledat67%within2min,whenthe pressurereacheditsmaximumvalue(100MPa).Sincethe temper-aturewasincreasedonlyafter5minfromtheSPSstart(Fig.4a), theobserveddensificationatroomtemperaturecanberelatedto particlesliding withnegligiblecontributionfromthediffusional processes.However,negativeramdisplacementwasrecordedat ∼600◦Cduringheatingataconstantpressure.Thisdisplacement

couldbeassociatedwithacertaindecreaseindensity,butasitis ceasedwhentheSPStemperatureof1000◦Cwasreached,itcan

berelatedtothethermalexpansionmismatchesbetweenthatof thegraphiteplungersandtheclosepackednano-particlenetwork. Apparently,theclosepackednano-particlesundergosurface dif-fusionduringtheheatingtoformarigidskeleton.Insuchacase, therigidskeletonmayopposefurther shrinkageunderthe con-stantpressure;ifthethermalexpansionofthisskeletonishigher thanthatofthegraphiteplunger,negativeramdisplacementmay occur. (Negativedisplacement due tothermal expansionofthe graphitemold,plungersandspacersisusuallyobservedwiththe increasingtemperatureusingblankspecimens.)Thisaspectwillbe discussedlaterindetail.Thedensitydidnotchangesignificantly duringtheSPSisotherm.Inaddition,increaseintheSPSduration to10 and15minresultedinhigherdensitiesof74.6and76.0%, respectively.

DensificationoftheSPreferenceY2O3nanopowderwasrecently

investigatedindetailundersimilarSPSconditions[20].Someof theresultswillbeusedhereforcomparison.ThedensityoftheSP referencespecimenat1000◦Ctreatmentincreasedwiththe

pres-sureincreaseatroomtemperature(Fig.4b),althoughitleveledoff atamuchlowerdensityof42%.However,incontrasttotheMP nano-powder,furtherincreaseinthedensitywasobservedduring theheatingprocess.Densificationwasacceleratedaround∼680◦C

andreacheditsmaximumvalueof93%around∼880◦C,beforethe

finalSPStemperatureof1000◦Cwasreached.

TheheatingratetotheSPStemperatureof1100◦Cwasof‘hot

compaction’anddifferedfromthatat1000◦C.Inthisrespect,a

heatingpulsewasusedtoreach600◦Cwithin3minunderthe

holdingpressureof 2MPa(Fig.5a).Thiswasfollowed by heat-ingto1100◦Cforadditional5min.Thenthepressurewaslinearly

increasedto100MPa,resultingin simultaneousincrease inthe density to its final value of 66%; nofurther densification was observedattheSPSisotherm.Similardensities(i.e.63.4and62.8%) were reached with further increase of the SPS duration to 10 and15min,respectively.Comparisonbetweenthedensities mea-suredattwoSPSregimes,i.e.at1000◦Cand1100◦C,revealedthat

theapplicationofpressure atthebeginning (‘coldcompaction’) resultedinhigherdensities.

ThecorrespondingSPspecimenexhibitedsignificantincrease in the density during theheating process between800◦C and

∼1050◦C, underthe2MPa holdingpressure only(Fig.5b)[20]. The maximum displacement/(shrinkage)rate was10−2mms−1.

Thisindicated thehigh capillaryforces in theSPto drive den-sification,incontrasttotheMPpowder,wherenodensification was recorded during the heating up. A higher densification rate(1.5×10−2mms−1)wasmeasuredwhen the pressure was

increasedtoitsmaximumvalue.Afinaldensityof93%,whichis higherthanthatoftheMPspecimen,wasreached.

Thedensificationbehavior intheMPspecimenat1500◦C is

shown in Fig.6, as in the other experiments,a very fast den-sification rate(1.5×10−2mms−1)wasrecordedsimultaneously

with the pressure increase. However, in this ‘hot compaction’ experiment(i.e.,aheatingpulseto600◦Cwasappliedbeforethe

pressurewasincreased),densificationceasedwhenthemaximum pressurewasreached.Densitywasstagnatedduringfurther heat-ing upto 1350◦C, where anadditional rapid densificationrate

Fig.5.Relativedensity–time–temperature–pressuredependenciesduringSPSof (a)MPand(b)SPY2O3nanoparticlesat1100◦Cfor5minand100MPa.

theperiodofdensity stagnation(i.e.,between200and650sin Fig.6), thepressureexperiencedtwodisturbancesexpressedby adecreaseof8–10MPaintherecordedpressure.Thesedecreases inpressureoccurredaround1030◦Cand1280◦C,andwere

recov-eredat 1130◦C and 1350◦C, respectively. The second pressure

recovery(increase)wasresponsiblefortherepeatedincreasein densificationat1350◦C,aswasmentionedabove.Thesepressure

disturbancesareassociatedwithincreaseintheresistanceofthe nano-particlestoundergosliding,whetherduetotheformation ofarigidskeletonorjammingoftheagglomeratednano-particles. Ineithercase,thermalexpansionsofboththegraphiteplungers andthespecimentogetherwiththelackofplasticityinthe speci-men,introduceinternalcompressivestresses.Sincetheexternal pressureappliedinthesystemisregulatedtoremainconstant, itsactualvalueshoulddecreaseinordertobalancetheinternal

Fig.6.Relativedensity–time–temperature–pressuredependenciesduringSPSof MPcubicY2O3nanoparticlesat1500◦Cfor5minand100MPa.

Fig.7.SEMimageshowingthehomogeneousdistributionofthesphericalgrains throughoutthespecimensinteredat1100◦Cfor5minand100MPausing

multi-phaseY2O3nanoparticles.

thermalpressuresformed.Thismayleadtothedisturbancesand decreasesobservedinthepresentSPSexperiments.

SEMimagesfromthespecimenssinteredat1100◦Cfor

differ-entdurations(i.e.5min,Fig.7)showedhomogeneousdistribution ofmanysphericalshapegrainsthroughoutthematrixoftheMP Y2O3 nanoparticles.Thelargestdiameterofthesphericalgrains

was∼15mmafter5min,and∼60mmafter10mindurations,with verywidegrainsizedistributions.Thesesphericalgrainsexhibited alowvolumefractionofthespecimensevenafter15minof sinter-ingat1100◦C.Thesesphericalgrainswereabsentaftersintering

at1500◦C;aregularpolyhedralshape grainmicrostructurewas

observed.

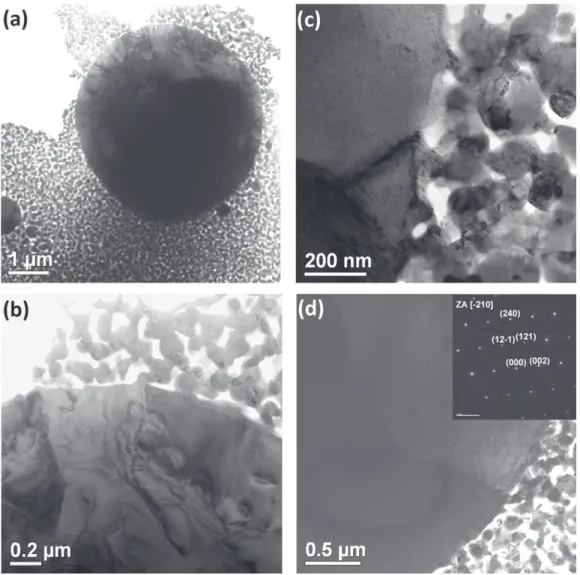

TEMimagesfromthespecimenssinteredatdifferent temper-aturesclearly revealedthe microstructureevolution duringthe SPS. First, at 1000◦C and 1100◦C, closeto the phase

transfor-mationtemperature,many polycrystallinesphericalparticles of submicrometerandmicrometer-sizeindiameterwereobserved withintheporousnanoparticlematrix(Fig.8a).Higher magnifica-tionprovedtheinternalstructureofthelargeparticles(Fig.8band c)tobecomposedofsub-grainsseparatedbydislocationnetworks; insomeoccasions,internalsubmicrometer-sizeporeswerealso observed.Thematrixwascomprisedofpartiallysintered nanopar-ticleswhichformedaporousnetworkresemblingthevermicular structure(theupperpartinFig.8b).Detailedexaminationofthe interfacebetweenthesphericalparticlesandthevermicular struc-turerevealedthattheformergrowontheaccountoftheporous nanoparticleskeleton(Fig.8c).Selectedareadiffractionpatterns confirmedthecubiccrystal symmetryof thesphericalparticles (Fig.8d).Therefore,itseemsthatthesphericalparticlespresent nucleationandinterface-controlledgrowthofthecubicgrainson theaccountofthemonoclinicnanoparticles.

Finally, TEM images from the 1500◦C treated specimen,

shown in Fig. 9, exhibit the micrometer size polyhedralshape grains with nanometric closed pores. Many grains were com-prisedofsub-grainsseparatedbydislocationnetworks(Fig.9b). A few nanometer size grains and closed pores were still visible along the sub-grain boundaries and at their corners (arrowed in Fig. 9b).This microstructure can beconsidered as analmostfullytransformedversionofthevermicular structure to thecubic grains. The microstructure evolution in the refer-ence single-phase cubic nanoparticle compactsduring the SPS were described in detail elsewhere [15,16,20]. At SPS temper-atures below 1100◦C, the nanometric character of the dense

Fig.8.TEMimagesshowingthe(a)nucleationandgrowthofthesphericalcubicY2O3grainsonaccountofthemultiphasenanocrystallinematrixat1000◦C.(b)Higher

magnificationof(a)showingthevermicularstructureofthematrixnanoparticles.(c)Theinterface-controlledgrowthofthesphericalcubicgrainsat1100◦C.(d)Selected

areadiffractionpatternconfirmedthecubicsymmetryofthesphericalY2O3grains.

compacts waspreserved. However, significant grain growthto micrometer-sizegrainswasobservedathighertemperatures[16]. The microstructural evolution associated withthe polymorphic phase transformationisthebasisfor theobserveddensification behavior ofthemultiphasenanoparticlesand willbediscussed below.

4. Discussion

Theobserveddensificationbehaviorofthetwonanopowders canbeexplainedbythemetastablenatureofthemonoclinic poly-morph.ThemonoclinicphaseisahighpressureversionofY2O3,

but can be retained in a metastable state at the atmospheric conditionswheninthenanoparticleform.Theseaspectsof poly-morphism,especiallyintheY2O3nano-particles,werediscussed

indetailelsewhere[19,21,22].Althoughbothpowdersexhibiteda closetonanocrystallineparticlesize(18-nmvs.41-nm),the sur-faceenthalpyofthemonoclinicpolymorphissignificantlyhigher (2.78Jm−2)thanthatofthecubicphase(1.66Jm−2)[19].

There-fore,thehighlyactivesurfacesofthemonoclinicnano-particles act as an efficient driving force for low-temperature sintering andneckformation.Thistypeofhighsinterabilityiswell char-acterized in transition alumina (g-alumina) and lead to rapid formationofa rigidporousskeletonbysurfacediffusionatlow

temperatures [23]; the resultant vermicular structure leads to low-densitysintered compacts.In this respect,consolidation of aluminananoparticlesbySPSshowedenhanceddensificationof the a-alumina compared to that of transition g-alumina [24]. Surprisingly, dense a-alumina was obtained at a considerably lowerSPStemperature,albeitoriginallywithalargerparticlesize. Thisbehaviorwasrelatedtog→aphasetransformationduring the SPS, which in turnled to the formation of the vermicular structure.

Thetheoreticaldensitiesofthecubic(c)andmonoclinic(m) Y2O3polymorphsare5.030gcm−3and5.468gcm−3,respectively [19]. Consequently, the polymorphic m→c phase transforma-tion is associated with∼8% volume increase. Nevertheless,the DSC results indicated the polymorphic transformation temper-ature to be around1000◦C, where a rigid skeleton of mY

2O3

hasbeendevelopedfairlywell.Ononehand,thekineticsofthis interface-controlled polymorphic phase transformation is more sluggish compared tothe SPSheating time scale, as evidenced byXRD analysis.Ontheotherhand, thepresenceof the nano-poreswithinthesphericalparticlesisanevidenceforaveryrapid interface-controlledprocess(i.e.nano-poreswerenotannealedby diffusion).Consequentlythechangeinthecompactvolume dur-ingtheheating,duetothephasetransformation,maybemarginal. SimilareffectswerereportedduringdensificationofSi3N4 with

Fig.9.TEMimagesshowingthe(a)micrometer-sizecubicgrainsformedat1500◦C.

Afewporesarevisiblealongthegrainboundaries.(b)Manysub-grainboundaries decoratedwithdislocationnetworksandnano-grainswerepresent(arrowed).

metallicsinteringadditivebySPS[25],wheresignificant shrink-ageoccurredbyparticlerearrangementandwhilealiquidphase wasformed.However,minorshrinkagewasobservedwhenphase transformationandgraingrowthviasolution-reprecipitationtook place.

Based on the microstructure developed in the multiphase nanoparticlecompacts,thefollowingprocessesmaybeconsidered. First, theapplication ofexternal pressure at roomtemperature enablesparticlesliding andrearrangement.Theearlyand rapid densificationstageceaseswhenreachingthemaximal pressure applied.Second,highlyreactivesurfacesof themnanoparticles enableenhancedneckformationandgrowthbysurfacediffusion duringtheheating.The partiallysinteredmnanoparticlesform a rigidand porous skeleton witha vermicular structure which opposesfurtherdensificationbyparticlesliding.Atandabovethe polymorphicm→cphasetransformationtemperature,nucleation ofthestablecphasetakesplace,homogeneouslythroughoutthe porousskeleton(thehomogeneous/heterogeneousnatureofthe nucleationeventwasnotinvestigatedhere).Furthergrowthofthe cubicnucleibythisinterfaced-controlledtransformationresults insphericalpolycrystallineparticles.Apparently,the8%volume

increaseaccompaniedtothetransformation,is notsufficientto overcomethevolumeconstraintsimposedonthegrowing spher-icalparticles withintherigid porousmatrix. Consequently,the elasticconstraintsmaybereducedbytheformationofdislocation networksandsub-grains,which,inturn,growontheaccountof them+cnanoparticles,attheirgrowingfront.Whentherapidly growingfrontofthesphericalparticlefacesalargecavityofthe vermicularstructure,itmaysurpassit,duetoinsufficienttimefor diffusion,resultinginoccludednano-pores.Athighertemperature, whenthephasetransformationisaccomplished,particlesliding, dislocationcreep,andgraingrowthmayberesponsibleforthelater stagedensificationclosetofulldensity.

Finally,theeffectofthevolumechangeduringthe polymor-phicphasetransformationtodensificationofthemultiphaseY2O3

nanoparticleswasnegligible.Nevertheless,themetastablenature andthehighsurface activityofthis polymorphwerethemajor causefortheformationofthevermicularstructure,whichinturn, inhibitedthedensificationduringtheheatingbySPS.The interface-controlledcharacterof thetransformation ledtotheformation ofverylargecubicgrains,responsibleforthelossofnanometric characterofthecompactsubjectedtodensification.

5. Summary

Sparkplasmasinteringofthemultiphasemonoclinicandcubic Y2O3 nanoparticles at 1000◦C exhibited limited densification

comparedtotherapiddensificationofthecubicsingle-phase coun-terpart.XRDofthemultiphasesinteredcompactsrevealedthatthe polymorphicmonoclinictocubicphasetransformationoccurred duringtheSPS around1000◦C, andwascompletedbyreaching

1100◦C.Themetastablemonoclinicphaseledtorapidneck

forma-tionduringtheheatingwhichresultedinavermicularnanometric matrixwithopenporositynetwork;thislimitedfurther densifi-cationofthemultiphasenanopowderandendedinverylowfinal densities.AtSPStemperaturesabovethepolymorphic transforma-tiontemperature,homogeneousnucleationofthesphericalcubic Y2O3grainswasobservedwithinthevermicularmatrix.This

inter-facecontrolledmonoclinictocubicphasetransformationresulted inthelossofthenanocrystallinecharacterofthecompact.SPSofthe multiphasenanoparticlesat1500◦Cshowedsimilardensification

behaviorasthepurecubicY2O3,resultinginadensemicrostructure

andcoarsemicrometer-sizepolyhedralshapedgrains. Acknowledgments

ThefinancialsupportoftheIsrael MinistryofScienceunder contract#3-3429isgratefullyacknowledged.WethankDr.Ori YeheskelfromNRC-NegevforsupplyingtheMPnanopowder. References

[1]S.-J.L.Kang,Sintering,Densification,GrainGrowth&Microstructure,Elsevier, Amsterdam,2005.

[2]J.Liu,D.P.DeLo,Metal.Mater.Trans.A32(2001)3117–3124.

[3]C.L.Martin,D.Bouvard,S.Shima,J.Mech.Phys.Solids51(2003)667–693. [4]R.Chaim,R.Reshef,G.Liu,Z.Shen,Mater.Sci.Eng.A528(2010)2936–2940. [5] E.Artz,M.F.Ashby,K.E.Easterling,Metall.Trans.A14A(1983)211–221. [6]R.Chaim,M.Margulis,Mater.Sci.Eng.A407(2005)180–187.

[7]D.A.Porter,K.E.Easterling,M.Y.Sherif,PhaseTransformationsinMetalsand Alloys,3rdedition,CRCPress,BocaRaton,2009.

[8]B.Li,X.Wang,L.Li,H.Zhou,X.Liu,X.Han,Y.Zhang,X.Qi,X.Deng,Mater.Chem. Phys.83(2004)23–28.

[9]T.Takeuchi,M.Tabuchi,H.Kageyama,Y.Suyama,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.82(1999) 939–943.

[10]X.Deng,X.Wang,H.Wen,A.Kang,Z.Gui,L.Li,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.89(2006) 1059–1064.

[11]J.Liu,Z.Shen,M.Nygren,B.Su,T.W.Button,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.89(2006) 2689–2694.

[12] K-N.P.Kumar,K.Keizer,A.J.Burggraaf,T.Okubo,H.Nagamoto,S.Morooka, Nature358(1992)48–51.

[13]Y.I.Lee,J.-H.Lee,S.-H.Hong,D.-Y.Kim,Mater.Res.Bull.38(2003)925– 930.

[14]U.Anselmi-Tamburini,J.E.Garay,Z.A.Munir,Mater.Sci.Eng.A407(2005) 24–30.

[15]R.Marder,R.Chaim,C.Estournes,Mater.Sci.Eng.A527(2010)1577–1585. [16]R.Chaim,A.Shlayer,C.Estournes,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.29(2009)91–98. [17]C.Suryanarayana,M.GrantNorton,X-rayDiffraction,APracticalApproach,

PlenumPress,NewYork,1998,pp.223–236.

[18]I.Halevy,R.Carmon,M.L.Winterrose,O.Yeheskel,E.Tiferet,S.Ghose,J.Phys. Conf.Ser.215(2010)012003.

[19]P.Zhang,A.Navrotsky,B.Guo,I.Kennedy,A.N.Clark,C.Lesher,Q.Liu,J.Phys. Chem.C112(2008)932–938.

[20]R.Marder,R.Chaim,G.Chevallier,C.Estournes,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.31(2011) 1057–1066.

[21]A.Camenzind,R.Strobel,S.E.Pratsinis,Chem.Phys.Lett.415(2005)193–197. [22]B.Guo,A.Harvey,S.H.Risbud,I.M.Kennedy,Phil.Mag.Lett.86(2006)457–467. [23]F.W.Dynys,J.W.Halloran,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.65(1982)442–448.

[24] R.S.Mishra,S.H.Risbud,A.K.Mukherjee,J.Mater.Res.13(1998)86–89. [25]G.H.Peng,X.G.Li,M.Liang,Z.H.Liang,Q.Liu,W.L.Li,ScriptaMater.61(2009)