ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx

Available

online

at

ScienceDirect

www.sciencedirect.com

Case

study

A

Byzantine

connection:

Eastern

Mediterranean

glasses

in

medieval

Bari

Elisabetta

Neri

a,∗,

Nadine

Schibille

a,∗,

Michele

Pellegrino

b,

Donatella

Nuzzo

baIRAMAT-CEB,UMR5060,CNRS,universitéd’Orléans,3D,ruedelaFérollerie,45071Orléanscedex2,France bUniversitàdegliStudiA.Moro,ComplessoSantaTeresadeiMaschi,stradatorretta,70122Bari,Italy

i

n

f

o

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

Historiquedel’article: Rec¸ule3avril2018 Acceptéle14novembre2018 DisponiblesurInternetlexxx Keywords:

EgyptII Lithium Boron Sodaash

Recyclednatronglass SouthernItaly Typology

A

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

ThetransitionfromtheRomannatron-basedglassindustrytothemedievalash-basedtraditioninItaly inthelatterpartofthefirstmillenniumCEisstillpoorlydocumented.Thecompositionaldataofeighteen glassfragmentsexcavatedfromtheByzantinepraetoriuminBarisuggestthatthedevelopmentinthe southernpartofthePeninsuladiffersfromthatinthenorth.Analysesbylaserablationinductively coupledplasmamassspectrometry(LA-ICP-MS)identifiedthefirstsignificantgroupofglassesinItaly thatwereproducedinandimportedfromtheeasternMediterraneanduringthelasttwocenturiesof thefirstmillenniumCE.SomesamplesexhibitthecharacteristicsofearlyIslamicnatronandplant-ash glasses,whiletwospecimensaresimilarinmajorandtraceelementcompositiontopost-Romanglasses mostlikelymanufacturedinByzantineAsiaMinor.Theserepresenttheonlyknownvesselsmadefrom theByzantinehighlithium,highboronglassfoundsofarinthewesternMediterranean.Theanalytical resultsthusshowthatbeingunderByzantinehegemonywasadvantageousfortradeconnectionsinthe medievalMediterranean.

©2018LesAuteurs.Publi ´eparElsevierMassonSAS.Cetarticleestpubli ´eenOpenAccesssouslicence CCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Primaryglassmakinghasexperienceda significant diversifi-cation and numeroustechnologicalinnovationsin thelate first millenniumCE([1,2]andreferencestherein).Betweentheeighth andtwelfthcenturies,natron-typeglasswasprogressively repla-cedbyeithersoda-richplant-ashglassintheMediterraneanarea orpotash-richplant-ashglassincentralandnorthernEurope(e.g.

[3–7]).Thesetechnologicalchangestriggeredare-organizationof

theprimaryproductioninthattheglassindustrythatwasonce concentratedinonlyafewlocationsalongtheLevantinecoastand inEgyptmultipliedandbecameincreasinglydecentralised.While thesetechnologicaldevelopmentshavebeenextensivelystudied inthecontextofnorthernItaly,littleattentionhasbeenpaidto howthesouthoftheItalianPeninsulawasaffectedbythese trans-formations.Systematictypologicalandchemicalanalysesofglass artefactsfromnumeroussitesinnorthernItalyrevealedthe exclu-siveuseofPalestinianandEgyptiannatron-typeglassesuntilthe seventh century CE[8–14]. Thereafter, recycling of theseolder natron-typeglassesbecomesincreasinglycommon[9,11].Thefirst soda-rich plant-ash glasses appear in theVenetian areain the

∗ Correspondingauthors.

Adressee-mail:nadine.schibille@cnrs-orleans.fr(N.Schibille).

eighthtoeleventhcenturyCE,heraldingagradualtransitionfrom theuseofnatrontoplant-ashglasses[15].Venicemightinfacthave beeninstrumentalintheimportoftheearliestsoda-richplant-ash glasstotheItalianPeninsula,duetoitsstrongculturaland econo-miclinkwiththeeasternMediterranean[15].Incontrast,thereisno systematicstudyonmedievalglassfindsfromsouthernItaly. Jud-gingfromthesmallnumberofavailabledata,importedLevantine andEgyptiannatron-typeglassesaretheprincipalsourcesof sup-plyuntilthesixthcenturyCEasreflectedintheglassassemblages fromthelateantiquevillaofFaragola[16]andthecityofHerdonia

[17].Intheseventhtoninthcenturies,glassfindsinRome(Crypta Balbi),SalernoandSt.VincenzoalVolturnoconsistmainlyof recy-clednatronglass[18–21].Todate,nosoda-richplant-ashglasshas beenidentifiedamongearlymedievalglassassemblagesfrom sou-thernItaly,implyingaglassconsumptionmodelthatisprincipally dependentonrecycling.

Thispaperpresentsnewarchaeometricdataofglassfindsfrom medievalBaritore-assessthetradeanduseofglassinsouthern Italyduringaperiodwhenglassmakingchangeddramatically.The materialunderinvestigationcomesfromthepraetoriuminthecity ofBariinthesouthItalianregionofApulia.Barihadbeenhotly contestedbytheLombards,Byzantines,Arabs,Berbersand Nor-mansduetoitsstrategicpositionontheAdriaticSea[22–24].After theestablishmentoftheByzantineThemeofLongobardiainthe secondhalfoftheninthcentury,laterthecatepanateofItaly,Bari https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

1296-2074/©2018TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierMassonSAS.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Pourcitercetarticle:E.Neri,etal.,AByzantineconnection:EasternMediterraneanglassesinmedievalBari,JournalofCulturalHeritage (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

2 E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx

Fig.1. ByzantineBariandtheBasilicaofSanNicola.Leftpanel:PlanoftheByzantinecityindicatingthelocationofthepraetorium;rightpanel:magnifiedgroundplanof the12th-centurybasilica(bothadaptedfrom[28]).

becametheofficialresidenceoftheByzantinegovernor[25].During Byzantinerule,thecityandtheterritoryofBariwereengagedin extensivecommercialactivities.Potteryfindsshow,forinstance, thatthecitywasabletosustainavariedpotteryproduction,while atthesametimespecialisedceramicswereimported[26].Among thefindsrecoveredduringtheexcavationsatBariwerenumerous glassartefacts[27]thatprovideanidealcasestudytoexplorethe changingpatternsofsupplyduringthetransitionalperiodfrom natron-typeglassestoplant-ashbasedrecipes.Weanalysedthe chemicalcompositionofeighteensamplestodeterminethemain glasstypesthatwereusedinBariandtodiscusshowthesupply ofglasstothecitywasaffectedbythenewdevelopmentsinglass makingtechnologies.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Archaeologicalcontext

Theglassfindsunderinvestigationwererecoveredintheareaof thepraetorium,theseatoftheByzantineadministrationthatwas lateroccupiedbytheBasilicaofSanNicola.Excavationsconducted between1980and2000confirmedthelocationofthepraetorium andrevealedacomplexarchaeologicalsequencewiththreemain phases.Anearlydomesticphase,datingtothefourthtoseventh centurywasfollowedbyapublicbuildingconnectedtothe deve-lopment of the Byzantine praetorium in theninth to eleventh century.Finally,thecitadelwasbuiltinthesecondhalfofthe thir-teenthcenturyCEduringtheAngiòreign(1266–1302CE).Theglass

sampleswereretrievedfromthefirsttwophasesinfrontofthe sou-thernbell-toweroftheBasilicaofSanNicolaexcavatedin1982,and insidethecourtyardofabbotEliastothesouthofthebasilicaduring excavationsin1987(Fig.1).Inbothareas,theByzantinenine-to eleventh-centurystructureswerebuiltoveralateantiquephase ofoccupation[28].

2.2. Theglassartefacts

Eighteenglassartefactswereselectedfromatotalof eighty-sixfragmentsfoundinthepraetoriumofBari.Thesesampleswere selectedtocoverthetransitionalperiodfromnatrontoplant-ash glassesandtorepresenttheentirerangeoftypologicalcategories encounteredat thesite.Theirrelative number reflectsthe ove-ralloccurrence of theindividualtypesand in terms ofcolours, theyrange from colourless,toyellowish green and light green

(Table1).Thirteensamples(BA03,04,07–17)canbeattributed

totheByzantineperiodbetweenthereignsofemperorTheophilos (829–842)andtheKomnenoi(1005–1071)(Table1).The remai-ningfivesamples(BA01, 02,05,06,18)havea relativelywide chronologicalspanfromthefifthtotheeleventhcenturybasedon numismaticandceramicevidence[27]thatmayoccasionallybe refinedbasedontheglasstype(seebelow).

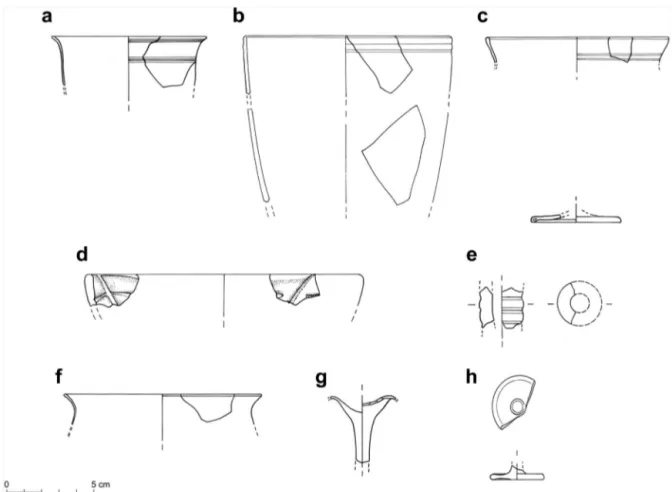

Most of the forms correspond to common domestic ware (goblets,cups,bottles)andlamps(Fig.2)oflateantiquetypologies thatarefoundallovertheMediterranean,includingsouthernItaly (e.g.[27,29–31]).Therearethreetypesofplainbeakers,Isings106b (BA02)witharoundededgeandagrooveddecorationunderthe

Pour citer cet article : E. Neri, et al., A Byzantine connection: Eastern Mediterranean glasses in medieval Bari, Journal of Cultural Heritage (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

AR

TICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No. of Pages 8 E. Neri et al. / Journal of Cultural Heritage xxx (2018) xxx–xxx Table1LA-ICP-MSdataoftheeighteenglasssamplesfromBari(includingtypologicalandarchaeologicaldata).Majorandminoroxidesincludingchlorine[wt%],andtraceelements[ppm].

Samples Colour Typology Context Archae.date Na2O MgO Al2O3 SiO2 P2O5 Cl K2O CaO TiO2 MnO Fe2O3 Li B

RomanSb BA03 Colourless Isings111 s.I,US117 9–11th 18.5 0.40 1.88 69.9 0.02 1.11 0.42 6.43 0.07 0.01 0.35 3.32 170

EgyptII BA04 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US117 9–11th 13.6 0.69 2.48 69.7 0.12 1.12 0.35 8.79 0.27 1.38 1.27 4.57 90.0

BA05 Lightgreen Goblet,Corinthiantype s.I,US112 5–11th 13.5 0.69 2.55 69.7 0.12 1.13 0.35 8.93 0.28 1.40 1.27 4.05 89.5 BA09 Lightgreen Smallbowl,linearimpressions s.I,US126 9–11th 15.3 0.53 2.31 68.9 0.07 1.16 0.62 9.78 0.28 0.02 0.90 4.09 71.9 BA10 Lightgreen Bottle,shortneck s.I,US117 9–11th 14.2 0.73 2.43 69.4 0.14 1.04 0.41 9.94 0.29 0.25 1.07 4.96 95.6 HLiB BA13 Yellow-green VariationIsings106b s.I,US117 9–11th 13.3 2.67 2.89 65.3 0.08 0.20 1.61 11.1 0.13 0.02 1.51 469 ###

BA17 Yellow-green Isings111 s.I,US3D-4E 9–11th 16.6 1.51 1.88 67.5 0.12 0.65 1.05 8.45 0.10 0.33 0.93 228 ###

Sodaash BA01 Colourless Isings106c s.I,US139 5–11th 11.6 3.18 1.67 70.0 0.34 0.85 2.15 8.35 0.09 1.16 0.51 5.36 87.8

BA07 Colourless Isings111 s.I,US117 9–11th 13.7 2.23 2.04 69.2 0.25 0.76 1.56 8.62 0.09 0.65 0.64 20.8 353

Natron recycled

BA02 Colourless Isings106b s.I,US130 5–11th 16.5 0.95 2.38 68.1 0.14 0.88 1.06 7.57 0.11 0.79 0.78 10.3 152

BA06 Colourless Goblet,Corinthiantype s.I,US112 5–11th 16.5 0.75 2.53 68.2 0.14 0.82 1.07 7.29 0.12 0.71 0.83 19.0 155 BA08 Lightgreen Goblet,localtype s.I,US117 9–11th 15.7 1.69 2.72 67.5 0.16 0.69 0.98 7.52 0.17 0.78 1.38 8.72 136

BA11 Colourless Isings111 s.I,US123 9–11th 17.4 0.75 2.36 68.2 0.11 0.98 0.65 7.38 0.13 0.79 0.78 6.42 153

BA12 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US117 9–11th 14.8 0.99 2.38 68.5 0.11 0.99 0.72 8.90 0.24 0.68 1.06 8.09 91.9

BA14 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US115 9–11th 16.2 0.88 2.46 67.7 0.17 0.85 1.10 8.07 0.14 0.82 0.88 10.8 151

BA15 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US115 9–11th 15.9 0.64 2.43 68.6 0.11 0.92 0.61 8.42 0.18 0.49 0.90 7.21 118

BA16 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US3D–4E 9–11th 16.7 0.71 2.59 67.9 0.14 0.75 1.02 7.41 0.11 0.76 0.81 9.24 151

BA18 Lightgreen Isings111 s.I,US19A 5–11th 17.8 0.82 2.30 67.6 0.12 1.08 0.62 6.68 0.19 0.97 0.94 5.11 169

V Cr Co Ni Cu Zn Ga As Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Ag Cd In Sn Sb Cs Ba La Ce Pr Nd Sm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb Lu Hf Ta W Pb Bi Th U 7.139.701.062.406.6515.22.4516.94.96471 4.9448.81.410.140.150.160.000.6961320.06127 5.299.211.124.530.910.240.760.130.760.160.430.060.440.071.130.070.0329.50.030.830.95 24.929.44.939.406.88128 4.402.315.40182 6.90187 4.010.560.100.190.010.351.20 0.07323 7.3313.71.596.291.360.351.020.171.110.240.670.100.660.113.990.210.097.610.011.521.19 24.629.94.939.516.89128 4.542.345.32185 7.16192 3.980.540.090.150.010.370.44 0.05327 7.4013.91.656.751.310.331.080.191.130.240.680.100.730.114.060.200.098.840.001.571.20 21.327.02.625.603.1713.83.290.794.70167 6.70226 4.000.120.090.060.010.31– 0.04155 7.3913.71.576.511.290.311.010.181.080.220.630.090.690.114.700.210.071.940.011.591.00 23.228.112.27.2744.144.83.491.444.71194 7.07207 3.960.330.280.110.023.123.14 0.06177 7.7314.21.666.541.330.331.070.181.100.230.660.100.700.114.370.200.0759.10.011.590.92 24.673.46.8573.46.6424.44.5730.991.1###5.0431.33.100.860.010.020.010.5555.2 61.579.68.2715.41.606.191.180.230.890.150.860.170.460.060.460.070.730.170.431.580.012.771.32 19.732.017.132.1265 43.22.8239.231.7###5.3042.91.941.450.410.050.0170.7313 16.9144 6.0911.41.224.911.020.250.780.130.840.170.490.070.460.070.990.120.24808 0.171.541.64 14.212.63.447.9038.931.83.112.5114.0413 6.1437.31.763.230.040.050.010.250.08 0.14230 6.5012.01.486.491.320.331.150.171.010.210.520.070.440.070.850.090.334.060.010.820.36 16.415.616.210.8110 37.53.0132.515.5393 5.7842.61.853.050.410.120.0213.35.82 1.57208 5.9911.01.315.261.060.260.930.150.890.190.510.070.480.071.030.130.36277 0.071.211.60 21.718.830.112.4935 59.73.4712.715.0474 6.8067.72.092.241.190.110.00259 18230.29274 7.3012.31.486.221.260.321.100.171.070.220.590.090.580.101.490.120.35###0.231.220.95 22.116.535.710.4###102 3.8718.723.0452 7.1767.22.562.141.580.130.00188 31190.62290 8.4114.31.736.811.430.361.140.181.060.230.630.080.640.091.490.120.52###0.221.481.01 25.948.735.639.5###108 4.1413.316.0416 7.7988.62.602.060.610.070.00216 17020.30294 8.5414.51.777.171.380.351.170.211.200.250.680.110.690.111.960.150.31###0.161.511.01 23.819.314.011.4607 42.83.3511.89.76450 7.2270.62.041.950.560.090.0079.814410.15284 7.4112.61.546.361.270.351.150.181.130.240.610.100.600.091.540.110.29581 0.071.110.98 22.827.974.311.1408 96.23.607.087.65268 6.95169 3.481.232.670.110.06259 13090.11225 7.5913.91.606.391.310.341.090.181.070.240.650.090.690.113.540.180.17###0.141.501.01 23.020.338.813.0869 66.73.6811.516.5483 7.1484.72.362.341.400.070.00371 14930.27295 7.7213.31.616.601.300.351.190.181.120.240.630.090.610.101.910.130.48###0.301.341.03 21.622.326.79.41930 62.53.479.8510.6321 6.88121 2.871.320.820.120.00261 16220.20232 7.4813.21.586.311.300.331.070.181.060.230.630.090.610.102.670.150.31###0.181.390.99 22.615.724.810.1###76.43.6517.521.6465 7.0663.12.262.221.210.110.00198 32860.54296 7.8713.61.616.541.330.351.080.191.100.230.630.090.580.091.430.120.59###0.241.371.07 26.426.446.312.7###50.73.7617.611.1456 7.47110 2.662.750.890.130.03123 26700.20354 7.8813.31.616.721.360.351.130.191.150.250.660.090.670.102.340.130.47###0.171.340.97

Pourcitercetarticle:E.Neri,etal.,AByzantineconnection:EasternMediterraneanglassesinmedievalBari,JournalofCulturalHeritage (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

4 E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx

Fig.2.SelectionofanalysedsamplesfromBariaccordingtoobjecttypes;a:Isings106btype(sampleBA02);b:Isings106c(BA01);c:Isings111(BA04);d:smallbowlwith linearimpressions(BA09);e:smallbottlewithashortneckandhorizontalrings(BA10);f:gobletofCorinthiantypeDav.12.716(BA05);g:stemmedgobletofCorinthian typeDav.12.718(BA06);h:gobletwithdiscoidbaseandsolidstem(BA08);(drawings:V.Acquafredda,M.Pellegrino).

rim,Isings106c(BA01)withunworkedrimandawheel-engraved decorationonthebody,andaconicalbeaker(BA13)withaconcave baserelatedtoIsings106b.Themostprevalentvesseltypesare stemmedgoblets,usedasdrinkingvesselsorlamps.Thesegoblets circulatedbetweenthefifthandtheeleventhcenturyCE,displaying somevariabilityinformbutwithoutanymajortechnicaland mor-phologicaldifferences [29,31].Theyusuallyhave simple shapes eitherconical(BA03,11,14,17),bell-shaped(BA04)or globu-lar(BA05),withroundededgesandatubularbasering(BA07, 12,15,16,18).AfewobjectsbelongtomedievalCorinthiantypes (BA05,06)([32]Fig.12.716,12.718) thathavepreviouslybeen identifiedinsouthernItalyinninth-toeleventh-centurycontexts

[33],whilea gobletwitha discoidbaseand solidstem (BA08) possiblyrepresentstheoutputofa localproduction,since limi-tedcomparable material is knownfrom southern Italy [34,35]. Theirchronologicaloccurrenceallowsustoconstrainthedatefor thesesamplestotheninth toeleventhcentury CE.Finally, two remarkablepieceshave theclosestparallelsintheearlyIslamic world.Onefragment(BA09)isasmallbowlwitharoundedrim andstraight walls,decoratedwithlinear impressionsthat have beenobtainedbytongs(Fig.2).Itisconsideredanunicuminthe archaeologicalrecordofsouthernItaly,whereasnumerousfinds withsimilarpatternshavebeenrecoveredfromseveralsitesin theeasternMediterraneandating totheninthtotenthcentury CE[27].Theothersample(BA10)belongstoasmallbottlewith ashort cylindricalridgedneck andhorizontal ringsaroundthe neck(Fig.2).Bottleswithsimilarmorphologicalfeatureswerequite commoninEgypt,Israel,Syria,IranandIraq[27].Hence,thesetwo vesseltypologiesappear tohavebeendevelopedinglass work-shopsoftheIslamiceastduringtheUmayyadandearlyAbbasid period.

2.3. Analyticalmethods

Thecleaned,butotherwiseunpreparedglassfragmentswere first inspected under the stereomicroscope to determine their colourandsubsequentlyanalysedbylaserablationinductively cou-pledplasmamassspectrometry(LA-ICP-MS)attheCentreErnest Babelon(CEB)ofIRAMATinOrléansusingaThermofisherElement XRcombinedwithaResoneticUVlasermicroprobe(ArF193nm). Theanalyticalset-upandprotocolaswellastheconversioninto fullyquantitativeresultshavepreviouslybeendescribedindetail

[36,37].Theanalyticalprecisionandaccuracyofthemeasurements

establishedbytherepeatedanalysisofCorningA,BandDandNIST 612aregivenasAppendixA,Supplementarymaterial(TableS1). Accuracyisgenerallybetterthan5%relativeformostmajorand minorelements,andbetterthan10%formosttraceelements.

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. Baricompositionalgroups

TheglassfindsfromBariareallsoda-lime-silicaglasses(Table1), the majority of which classify as mineral soda glass with low magnesium and potassium oxideconcentrations (<1.5%),while threesamples(BA01,07,13)haveelevatedlevelsofbothpotash andmagnesia(>1.5%)conventionallyattributedtotheuseofplant ashasthefluxingagent(Fig.3a)[38].Thestrontiumtocalcium ratios,aluminaandsodalevelsoftwoofthesesamples(BA01,07) areconsistentwithsoda-richplantashglassesfromtheeastern Mediterranean.Incontrast,sampleBA13,togetherwithsampleBA 17haveunusuallyhighstrontiumrelativetocalciumand excep-tionallyhighlithium and boronconcentrations (Fig.3b,c). The

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx 5

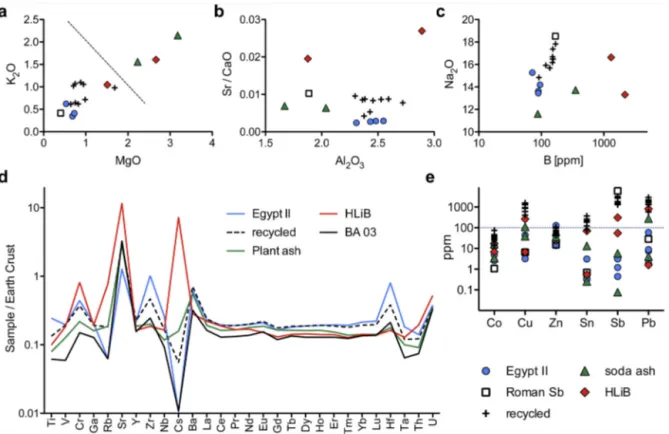

Fig.3.BaseglasscharacteristicsoftheglasssamplesfromBari;a:potashandmagnesiaconcentrationsseparatethenatron-typeglassesfromplantashglasses;b:strontium tolimeratiosversusaluminalevelsidentifydifferentrawingredients.ThelowstrontiumlevelsofEgyptIIarereflectiveofcalcareousrocksandthusacontinentalsilica source;c:sodaandboronlevelsdistinguishdifferentglassmakingrecipes;d:averagetraceelementpatternsofthefivedifferentglassgroupsfromBarinormalisedtothe meanvaluesoftheuppercontinentalearthcrust[39];e:elevatedlevelsoftransitionmetalspointtoahighincidenceofrecycling.

twosamplesalsoshowtraceelementpatterns(e.g.Cr,Rb,Cs,Th) thatdivergefromtheprofilesusuallyencounteredinnatron-type glassesofLevantineand/orEgyptianorigin(Fig.3d)[39], identi-fyingdifferentrawmaterials.SampleBA17exhibitsfurthermore clearsignsofrecyclingintheformhigherthanusualmagnesium andpotassiumoxideslevels(Fig.3a)andelevatedcopper,tin, anti-monyandlead(Fig.3e).

Themineralsodaglassescanbesubdividedbasedontheirmajor, minorandtraceelementcontents(Fig.3).Foursamples(BA04,05, 09,10)withmoderatelevelsofaluminiumoxide(about2.4%)and soda(about14%),highlevelsoftitanium,zirconiumandlime,and lowstrontium contentsareclearly affiliatedwithninth-century EgyptII[40].Ninesamples(BA02,06,08,11,12,14,15,16,18) showintermediatecompositionalcharacteristicswithlowerheavy elements,somewhathigherstrontiumtocalciumratiosandhigher sodaconcentrationscomparedtotheEgyptIIsamples(Fig.3a–c). Allninesampleshaveelevatedconcentrations(>100ppm)of cop-per,tin,antimonyandlead,andtoalesserextentcopperandzinc (Fig.3e)aswellaspotash(Fig.3a).Itisgenerallyacceptedthat recyclinghasanimpactonthebaselinelevelsofcolouring, deco-louringandopacifyingelementsduetotheaccidentalintroduction ofcolouredcullettotheglassmelt, inadditiontothe contami-nationwithfuelashandcomponentsinthefurnaceatmosphere suchaspotash[41,42].Hence,giventhesubstantial contamina-tionsthroughcolouring agents, more thanhalf of theanalysed glassesfromBariexhibitclearsignsofrecyclingandmixingof dif-ferenttypesofnatronbaseglassessomeofwhichwerepresumably colouredandopacified.Interestingly,thesamplesmadefromthis recycledglassrepresenteitherlateantiqueforms(Isings106and 111)orlocalproducts(BA06,08)[34].Judgingfromtherelatively lowstrontiumlevelsofsomeoftheserecycledglasses(BA12,15,

Fig.3b),itisreasonabletoassumethatpartoftheculletwasofthe EgyptIItype,whiletheelevatedcontentsofantimonysuggestthe recyclingofRomanglass(Fig.3e).

Onesample(BA03)differssharplyonaccountofitslowlevels ofsilica-relatedcontaminantssuchascalcium,traceandrareearth elements, concurrent with low potash and magnesiaand high soda contents (Fig.3).Thesefeatures together withhighlevels ofantimony(6132ppm)identifythissampleasRomanantimony decolouredglass(Table1).Typologically,thissamplebelongstothe Isings111familythatwasverycommonduringthelateRomanand earlymedievalperioduptotheeighthcenturyCE[43].Thefactthat thissamplewithavirtuallypristineRomanantimonyglass signa-tureandalateantiquetypologywasretrievedfroma ninth-to tenth-centurycontextsuggestseitherthatthisobjecthadsurvived intactorthatitwasresidualmaterialfromtheearlieroccupation atthesite.

Thechromaticscaleoftheglassfindsdoestosomedegree coin-cidewiththecompositionalgroups.AllEgyptIIsamplesshowa lightgreencolourindependentoftheironandmanganesecontents, thehighlithium/highboronglassesexpressamoreintense yello-wishgreencolour,possiblyduetotheverylowmanganesecontents insufficient toact successfully as decolorant, and the soda ash glassesarevirtuallycolourless(Table1).Thegroupofrecycledglass rangefromcolourlesstolightgreencontingentonthemanganese toironratiosandthelatter’soxidationstate.

3.2. GlassconsumptionandsupplyinmedievalBari

Thehighincidenceofeighth-toninth-centuryEgyptianglasses amongtheBariassemblageintheformofrecycledaswellaslargely unadulteratedEgyptIIfragmentsisremarkable,especiallywhen comparedtootherItaliansites.FindsofEgyptIIglassaregenerally rareoutsideofEgypt.However,somespecimenshavebeen iden-tifiedamong glassesfromSyria-Palestine[2,44,45]andin some isolatedcasesinItaly[20],Spain[46]andAlbania[47].The pre-senceoffoursamplesoftheEgyptIItypethathavenotundergone substantialrecyclingandmixingcanbeexplainedbytherelative

Pourcitercetarticle:E.Neri,etal.,AByzantineconnection:EasternMediterraneanglassesinmedievalBari,JournalofCulturalHeritage (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

6 E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx

Fig.4.Traceelementpatternsofthehighlithium,highboronglassfromBariincomparisonwithsimilarsamplesfromHisinal-Tinat[52].Averageswerenormalisedtothe meanvaluesoftheuppercontinentalearthcrust[39],standarddeviationsoftheHisinal-Tinatassemblagearegivenaserrorbars.HT040wassingledout,becauseitshows averysimilarREEprofiletothesamplesfromBari.

chronologyofthisprimaryproductiongroup.EgyptIIisattributed tobetweenthelastquarteroftheeighthandthefirstthree quar-tersoftheninthcenturyCE[40].Archaeologically,threeofthefour samplesfromBariaredatedtotheninthtoeleventhcenturyCE, whilethedateofsampleBA05(Table1)cannowberefinedto thelateeighthtoeleventhcenturyCEduetoitsEgyptIIsignature. TwooftheEgyptIIsamples,onebell-shapedgobletwithwhitetrail decoration(BA04),theotheraglobulargoblet(BA05),cannotbe unambiguouslyattributedtoaspecificsecondaryworkshop tradi-tioneven thoughthelatterisassociatedwithaCorinthiantype

[32].The othertwoEgyptII samples(BA09 and 10),however, representearlyIslamicvesseltypesfromtheninthtotenth cen-turysimilartosamplesfromtheeasternMediterranean,butscarce ornon-existentintheItalianPeninsula[27].Takentogetherthe differentpiecesofevidencepointtotheimportoffinishedglass artefacts,andpossiblyrawglass,fromIslamicEgyptintheninthor tenthcenturyCE.

ThetwoplantashglassesfromBari(BA01and07)havebeen producedfromhalophyticplants inlinewiththeeastern Medi-terraneansoda-richplantashglasstradition[1,7].Withmoderate magnesiumandpotassiumconcentrations(1.5%<MgO,K2O<3.5%)

andrelativelylowsilica-relatedimpuritiessuchasaluminium, tita-niumandzirconium(Fig.3,Table1),theirclosestparallelsarefound inSyria-Palestine[1].Thesetwosamplesthusprovidethefirstclear evidenceoftheimportofsoda-richplantashglassfromtheIslamic easttoByzantinesouthernItaly.Thisisreminiscentofthesituation innorth-easternItaly,wheresoda-richplantashglassesfromthe easternMediterraneanarrivedasearlyastheeight/ninthcentury

CE[10,15].ThetwovesselsfromBaricorrespondtolateantique

typologies(Isings106,111),andarchaeologicallytheyare attribu-tedtothefifthtoeleventhcentury(BA01)andtheninthtoeleventh century(BA07).Giventhesoda-richplantashsignature,however, thedateofsampleBA01canbeattributedtotheeighthcentury orlater,whenplantashglassesbegintospreadintheIslamiceast. ThisclearlyreflectsthelongevityofIsings106and111wellinto theearlyMiddleAges.

Anongoingeconomicandculturalexchangewiththeeastern MediterraneanissubstantiatedbythepresenceofByzantinehigh lithiumandhighboronglasses.Thehighlevelsoflithium,boronand strontiumreflectrawmaterialsthataredifferentfromknownfirst millenniumprimaryproductiongroupsinEgyptandtheLevant. Ithasbeenproposedthatamineralsodamighthavebeen extrac-tedfromtheboratelakesofcentralTurkeyfortheproductionof thesehighboronglasses[48],supportingthehypothesisofprimary glassmakinginAsiaMinor,asfirstproposedbyRobertBrill[49]. AprimaryproductionlocationinAsiaMinoralsoimpliestheuse ofdifferentsilicasources,whichmayexplainsomeoftheatypical

traceelementpatternsandincreasesinsilicarelatedcontaminants suchaschromium,nickel,thoriumandaboveallcaesium(Fig.3d). Inmostotherglassescaesiumoccursatvaluesbelow1ppm, whe-reasthehighboronglassesreachlevelsofCsinexcessof60ppm

(Table1)[50,51]thatisprobablylinkedtothesilicasource[52].

Furthermore,thereisevidenceoftwodifferenthighboron glass-makingrecipes,onebasedonmineralsoda,theotherusingaplant ashcomponent[49–51,53].Whilemineralsodaprobablyunderlies sampleBA17,sampleBA13withbothmagnesiumandpotassium oxidesinexcessof1.5%ismorelikelytheresultoftheadditionof plantash.Highboronglasseshaveseldombeenfoundoutsideof AsiaMinor,onlysomeisolatedexamplesareknownfromGreece, VeniceandRome[50].Intermsofthelithium,boronandstrontium levels,thetwosamplesfromBariresembleagroupofmiddleand lateByzantineglassesfromPergamon[50],andtenth-to twelfth-centurybraceletsfromHisinal-Tinat(Turkey)[51].However,the glassesfromPergamonhaveconsistentlyhigheraluminacontents (>5%)andclearlyrepresentadifferentprimaryproduction,while thebraceletsfromHisinal-Tinathavenotablylowertitaniumoxide andhigherREE(Fig.4).Althoughnotaperfectmatch,thetrace elementpatternofgroup3fromHisinal-Tinatandespeciallyof HT040arereasonablysimilartothetwosamplesfromBarito indi-cateachemicalandbyextensiongeographicalrelationship.What ismore,thehighboronglassesidentifiedtodate[49–51,53]tend tobehighlyvariable,whichisreflectedalsointhestandard devia-tionsoftheHisinal-Tinatbracelets(Fig.4).TheoutlierHT040was interpretedbytheauthorsasbeingpossiblytheresultofmixing two differentglasses[51].Asmentioned above, oursampleBA 17likewise showssigns ofmixingand recyclingintheformof elevatedcolouringelements.Thetwofragmentsrecoveredfrom ninth-toeleventh-centurycontextsinBariprovidethefirstclear evidenceforthecirculationofvesselsofthistypeofhighlithium, highboronglassinthewesternMediterranean.Itiswidely assu-medtobeaquintessentiallyByzantineglasstype,manufacturedin alllikelihoodinAsiaMinor[48,49,50],anditmaythusnotcome asasurprisethatithasbeenfoundinthecontextoftheByzantine ThemeofLongobardia,highlightingthestrongmateriallink bet-weensouthernItalyandByzantineAsiaMinor.Withalateantique typology(Isings106,111),thetwofragmentssupportsoncemore thesurvivaloftheseglasstypologiesintothelatefirstmillennium CE.

Thetypologicalandcompositionalcharacteristicsofthe medie-valglassesfromBaritestifytotheactiveexchangebetweenthe Byzantine province of southern Italy and the Byzantine heart-landontheonehand,andtheIslamicworldontheotherhand. EventhoughasignificantproportionoftheglasssupplyatBari wasevidently dependentonrecycled natron glassin line with

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx 7 othercontemporaryItaliansites(e.g.[8,11,20]),almosthalfofthe

glasses analysed correspond to raw glass produced in the late eighthcenturyorlater.Thishighoccurrenceoflatefirstmillennium glassimportsconstitutesanexceptionwithintheItalianPeninsula, whereamaximumof10%oftheglassrepresentsimported soda-richplantashglassfromtheeasternMediterranean[8–14,18–21]. Inthis,theglassassemblagefromBaridemonstratesclose paral-lelswithVenice,whereupto50%oflatefirstmillenniumfindsare soda-richplantashglassesfromtheLevant[15].Theproductiveand commercialset-upsuggestedbythepresentstudyoftheglasses fromBarihasasignificantparallelintheceramicfindsinsofaras theceramicstooareeitheroflocalproductionorimportedfrom theBalkansandtheAegean[26].Thehighproportionofimports ofvitreousmaterialatBarimayberelatedtothepresenceofthe Byzantinegovernorandothergovernmentofficialsthat strengthe-nedcommercialanddiplomaticrelationswiththeByzantineand Islamicterritoriesatlarge,especiallyafterthecitybecamethe capi-taloftheByzantinecatepanateofItalyinthetenthcentury.Infact, theChroniconBarensis(AnonymiBarensisChronicon,adann.1045, 1051and1062)reportshowthecityofBaribecametheepicentre ofmaritimetraffic,becausetheByzantineconqueststimulatedthe tradewithGreeceandtheeasternMediterranean.

4. Conclusion

ThestudyoftheglassfindsfromBariprovidesnewinsightsinto howgeo-politicalandtechnologicaldevelopmentsinthemedieval Mediterraneanshapetheproductionandsupplyofvitreous mate-rialsinsouthernItaly.ThegradualtransitionfromtheRomanglass industrythatusednatronasfluxingagenttomedievalash-based recipesisreflected,forinstance,inthesystematicrecyclingandthe presenceoflatefirstmillenniumglasstypessuchasIslamicEgypt II,easternMediterraneansoda-richplantashandByzantinehigh lithium,highboronglasses.Thevariabilityoftheglassfragments analysedsetsthearchaeologicalrecordofBariapartfromtherest oftheItalianPeninsulawiththepossibleexceptionofVenice.This showsthattheByzantineprovinceofLongobardiawasintegrated intoanextensivenetworkofexchangethatwascontrolledbyastill thrivingByzantineEmpire.

Acknowledgments

ThisprojecthasreceivedfundingfromtheEuropeanResearch Council(ERC)undertheEuropeanUnion’sHorizon2020research andinnovationprogramme(grantagreementNo.647315toNS). Thefundingorganisationhadnoinfluenceinthestudydesign,data collectionandanalysis,decisiontopublish,orpreparationofthe manuscript.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarymaterialrelatedtothisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,athttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009.

Références

[1]M.Phelps,GlasssupplyandtradeinearlyIslamicRamla:aninvestigationof theplantashglass,in:D.Rosenow,M.Phelps,A.Meek,I.C.Freestone(Eds.), ThingsthatTravelled:MediterraneanGlassintheFirstMillenniumCE,UCL Press,London,2018,pp.236–282.

[2]M.Phelps,I.C.Freestone,Y.Gorin-Rosen,B.Gratuze,Natronglassproduction andsupplyinthelateantiqueandearlymedievalNearEast:Theeffectofthe Byzantine-Islamictransition,J.Archaeol.Sci.75(2016)57–71.

[3]B.Velde,Glasscompositionsoverseveralmillenniainthewesternworld,in: K.Janssens(Ed.)ModernMethodsforAnalysingArchaeologicalandHistorical Glass,I,JohnWiley&Sons,Chichester,2013,pp.67–78.

[4]A.Shortland,L.Schachner,I.Freestone,M.Tite,Natronasafluxintheearly vitreousmaterialsindustry:sources,beginningsandreasonsfordecline,J. Archaeol.Sci.33(2006)521–530.

[5]K.H.Wedepohl,K.Simon,Thechemicalcompositionofmedievalwoodash glassfromCentralEurope,ChemieDerErde-Geochem.70(2010)89–97. [6]D.Whitehouse,ThetransitionfromnatrontoplantashintheLevant,J.Glass

Stud.44(2002)193–196.

[7]J.Henderson,S.Chenery,E.Faber,J.Kröger,Theuseofelectronprobe microa-nalysisandlaserablation-inductivelycoupledplasma-massspectrometryfor theinvestigationof8th–14thcenturyplantashglassesfromtheMiddleEast, Microchem.J.128(2016)134–152.

[8]G.Salviulo,A.Silvestri,G.Molin,R.Bertoncello,Anarchaeometricstudyof thebulkandsurfaceweatheringcharacteristicsofEarlyMedieval(5th–7th century)glassfromthePovalley,northernItaly,J.Archaeol.Sci.31(2004) 295–306.

[9]A.Silvestri,A.Marcante,TheglassofNogara(Verona):a ¨window ¨onproduction technologyofmid-MedievaltimesinNorthernItaly,J.Archaeol.Sci.38(2011) 2509–2522.

[10]A.Silvestri,G.Molin,G.Salviulo,RomanandmedievalglassfromtheItalian area:bulkcharacterizationandrelationshipswithproductiontechnologies, Archaeometry47(2005)797–816.

[11]M.Uboldi,M.Verità,ScientificanalysesofglassesfromLateAntiqueandEarly MedievalarcheologicalsitesinNorthernItaly,J.GlassStud.45(2003)115–137. [12]M.Verità,A.Renier,S.Zechin,Chemicalanalysesofancientglassfindings

exca-vatedintheVenetianlagoon,J.Cult.Herit.3(2002)261–271.

[13]M.Verità,M.Vallotto,AnalisichimicadirepertivitreidelIVsecolodCrinvenuti aSevegliano(Udine),QuaderniFriulaniArcheol.8(1998)7–19.

[14]A.Zucchiatti,L.Canonica,P.Prati,A.Cagnana,S.Roascio,A.C.Font,PIXEanalysis ofV–XVIcenturyglassesfromthearchaeologicalsiteofSanMartinodiOvaro (Italy),J.Cult.Herit.8(2007)307–314.

[15]M.Verità,Venetiansodaglass,in:K.Janssens(Ed.),Modernmethodsfor ana-lysingarchaeologicalandhistoricalglass,JohnWiley&Sons,Chichester,2013, pp.515–536.

[16]E.Gliozzo,M.Turchiano,F.Giannetti,I.Memmi,Lateantiqueandearlymedieval glassvesselsfromFaragola(Italy),Archaeometry58(2016)113–147. [17]E.Gliozzo,M.Turchiano,F.Giannetti,A.SantagostinoBarbone,Lateantique

glassvesselsandproductionindicatorsfromthetownofHerdonia (Fog-gia,Italy):NewdataonCao-rich/weakHIMTglass,Archaeometry58(2016) 81–112.

[18]I.C.Freestone,F.Dell’Acqua,EarlymedievalglassfromBrescia,Cividaleand Salerno,Italy:compositionandaffinities,in:D.Ferrari(Ed.)AttidelleVIII Gior-nateNazionalidiStudio:Ilvetronell’altomedioevo,AIHV;Imola,2005,pp.65-75. [19]P.Mirti,P.Davit,M.Gulmini,GlassfragmentsfromtheCryptaBalbiinRome:the compositionofeighth-centuryfragments,Archaeometry43(2001)491–502. [20]N. Schibille, I.C. Freestone, Composition, production and procurement

of glass at San Vincenzo al Volturno: an early medieval monas-tic complex in Southern Italy, PLOS One 8 (10) (2013) e76479, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076479.

[21]M.Sternini,IlvetroinItaliatraVeIXsecolo,in:D.Foy(Ed.)Leverrede l’AntiquitétardiveetduhautMoyenAge:typologie,chronologie,diffusion. Associationfranc¸aisepourl’archéologieduverre(huitièmerencontre, Guiry-en-Vexin18–19novembre1993).MuséearchéologiquedépartementalduVal d’Oise;Guiry-en-Vexin,1995,pp.243-289.

[22]V.vonFalkenhausenandG.Cavallo,IBizantiniinItalia,Milano,1982. [23]V.vonFalkenhausen,Baribizantina:profilodiuncapoluogodiprovincia(secoli

IX-XI),in:G.Rossetti(Ed.)Spazio,società,poterenell’ItaliadeiComuni,Liguori; Napoli,1986,pp.195-227.

[24]F.Bulgarella,Leterrebizantine,in:G.Galasso,R.Romeo(Eds.),Storiadel Mez-zogiornoII,IlMedioevo,Rome,1989,pp.453–460.

[25]M.R.Depalo,G.Disantarosa,D.Nuzzo,Introduzione,in:M.R.Depalo,G. Disan-tarosa,D.Nuzzo(Eds.)CittadellaNicolaiana-1:ArchaeologiaurbanaaBari nell’areadellaBasilicadiSanNicolaSaggi1982-1984-1987,Bari,2015,pp. 15-18.

[26]S.Airò,LeceramichediEtàmedievale:produzione,commercioeconsumoa BaritraVIIIetXIVsecolo,in:M.R.Depalo,G.Disantarosa,D.Nuzzo(Eds.) Cit-tadellaNicolaiana-1:ArchaeologiaurbanaaBarinell’areadellaBasilicadiSan NicolaSaggi1982-1984-1987,Bari,2015,pp.251-258.

[27]M.Pellegrino,Imanufattivitrei,in:M.R.Depalo,G.Disantarosa,D.Nuzzo(Eds.) CittadellaNicolaiana-1:ArchaeologiaurbanaaBarinell’areadellaBasilicadi SanNicolaSaggi1982-1984-1987,Bari,2015,pp.275-282.

[28]D.Nuzzo,M.R.Depalo,S.Airò,Archeologiaurbananella“Cittadellanicolaiana” diBari.NuovidatidalriesamedelleindaginideglianniOttantanell’areadel pretoriobizantino,TemporisSigna,Archaeologiadellatardaantichitàedel medioevo7(2012)79–106.

[29]G.Bertelli,LaproduzionevetrariadietàaltomedievaleinPuglia.Notizie preli-minari,in:C.Piccioli,F.Sogliani(Eds.),IlvetroinItaliameridionaleeinsulare. AttidelPrimoConvegnoMultidisciplinare(Napoli,5-6-7marzo1998),Napoli, 1999,pp.139-149.

[30]R.Giuliani,M.Turchiano,IvetridellaPugliacentro-settentrionaletraTardo AnticoeAltoMedioevo,in:C.Piccioli,F.Sogliani(Eds.),IlvetroinItalia Meridio-naleeinsulare.Ilconvegnomultidisciplinare,VIIGiornateNazionalidiStudidel ComitatoNazionaleItalianoAIHV(Napoli,6-7dicembre2001),Napoli,2003, pp.139-159.

[31]D.Stiaffini,Contributoadunaprimasistemazionetipologicadeimaterialivitrei medievali,in:M.Mendera(Ed.),Archeologiaestoriadellaproduzionedelvetro preindustriale,All’InsegnadelGiglio,Firenze,1991,pp.177–266.

Pourcitercetarticle:E.Neri,etal.,AByzantineconnection:EasternMediterraneanglassesinmedievalBari,JournalofCulturalHeritage (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.11.009

ARTICLE IN PRESS

G Model

CULHER-3512; No.ofPages8

8 E.Nerietal./JournalofCulturalHeritagexxx(2018)xxx–xxx [32]G.R.Davidson,CorinthXII:Theminorobjects,Objects.Princeton,(1952).

[33]S.Catacchio,Vetri,in:P.Caprino,F.Ghio,M.A.Sasso(Eds.)IlcomplessodiS. MariadelTempioLecce.Scavi(2011-2012),Galatina,2013,pp.137-152. [34]E.Andronico,VetridaReggioCalabria,BovaeLazzaro(MonteSanGiovanni),

in:A. Coscarella (Ed.) Ilvetro in Italia:testimonianze,produzioni, com-merciinetàbassomedievale:ilvetroinCalabria:vecchiescoperte,nuove acquisizioni:attiXVGiornatenazionalidistudiosulvetroAIHV,Università dellaCalabriaAulaMagna,9-11giugno2011,UniversitàdellaCalabria,2012, pp.131-150.

[35]C.Raimondo,IvetridelcastrumbizantinodiS.MariadelMare,in:A.Coscarella (Ed.)IlvetroinCalabria.ContribuzioneperunacartadidistribuzioneinItalia, SoveriaManelli,2003,pp.307-316.

[36]B.Gratuze, Glasscharacterization usinglaserablation-inductivelycoupled plasma-massspectrometrymethods,in:L.Dussubieux,M.Golitko,B.Gratuze (Eds.),RecentAdvancesinLaserAblationICP-MSforArchaeology,Series: Natu-ralScienceinArchaeology,Springer,Berlin,Heidelberg,2016,pp.179–196. [37]N.Schibille,A.Meek,B.Tobias,C.Entwistle,M.Avisseau-Broustet,H.DaMota,B.

Gratuze,ComprehensivechemicalcharacterisationofByzantineglassweights, PLOSOne11(2016)e0168289.

[38]C.Lilyquist,R.H.Brill,StudiesinEarlyEgyptianGlass,MetropolitanMuseumof Art,NewYork,1993.

[39]B.S.Kamber,A.Greig,K.D.Collerson,Anewestimateforthecompositionof weatheredyounguppercontinentalcrustfromalluvialsediments,Queensland, Australia,GeochimicaetCosmochimicaActa69(2005)1041–1058. [40]B.Gratuze,J.N.Barrandon,Islamicglassweightsandstamps-analysisusing

nucleartechniques,Archaeometry32(1990)155–162.

[41]I.C.Freestone,TherecyclingandreuseofRomanglass:analyticalapproaches, J.GlassStud.57(2015)29–40.

[42]S.Paynter,ExperimentsinthereconstructionofRomanwood-fired glasswor-kingfurnaces:wasteproductsandtheirformationprocesses,J.GlassStud.50 (2008)271–290.

[43]L.Saguì,B.Lepri,LaproduzionedelvetroaRoma:Continuitàediscontinuitàfra tardoanticoealtomedioevo,in:A.Molinari,R.SantangeliValenzani,L.Spera (Eds.)L’archeologiadellaproduzioneaRoma(secoliV-XV):Attidelconvegno internazionaledistudiRoma27-29marzo2014,Collectiondel’Écolefranc¸aise deRome516Roma,Bari,2016,pp.225-241.

[44]S.Fiorentino,T.Chinni,E.Cirelli,R.Arletti,S.Conte,M.Vandini,Consideringthe effectsoftheByzantine–Islamictransition:Umayyadglasstesseraeandvessels fromtheqasrofKhirbetal-Mafjar(Jericho,Palestine),Archaeol.Anthropol.Sci. 10(2018)223–245.

[45]I.C.Freestone,R.E.Jackson-Tal,I.Taxel,O.Tal,Glassproductionatanearly IslamicworkshopinTelAviv,J.Archaeol.Sci.62(2015)45–54.

[46]J.deJuanAres,N.Schibille,GlassimportandproductioninHispaniaduringthe earlymedievalperiod:theglassfromCiudaddeVascos(Toledo),PLOSOne12 (2017)e0182129.

[47]E.Neri,B.Gratuze,N.Schibille,Thetradeofglassbeadsinearlymedieval Illyricum:towardsanIslamicmonopoly,Archaeol.Anthropol.Sci.(2018)1–16. [48]M.Tite,A.Shortland,N.Schibille,P.Degryse,Newdataonthesodafluxusedin theproductionofIznikglazesandByzantineglasses,Archaeometry58(2016) 57–67.

[49]R.H.Brill,ChemicalanalysesoftheZeyrekCamiiandKariyeCamiiglasses, DumbartonOaksPapers59(2005)213–230.

[50]N.Schibille, LateByzantinemineralsodahigh alumina glassesfromAsia Minor:anewprimaryglassproductiongroup,PLOSOne6(4)(2011)e18970, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018970.

[51]C.Swan,T.Rehren,L.Dussubieux,A.Eger,High-boronandhigh-aluminamiddle Byzantine(10th–12thcenturyCE)glassbracelets:awesternAnatolianglass industry,Archaeometry60(2018)207–232.

[52]P.Degryse,GlassMakingintheGreco-RomanWorld:ResultsoftheARCHGLASS Project,LeuvenUniversityPress,2014.

[53][53]R.H.Brill,ChemicalAnalysesofEarlyGlasses,TheCorningMuseumof Glass,Corning,NewYork,1999.

![Fig. 1. Byzantine Bari and the Basilica of San Nicola. Left panel: Plan of the Byzantine city indicating the location of the praetorium; right panel: magnified ground plan of the 12th-century basilica (both adapted from [28]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6018468.150298/2.918.105.792.81.606/byzantine-basilica-byzantine-indicating-location-praetorium-magnified-basilica.webp)

![Fig. 4. Trace element patterns of the high lithium, high boron glass from Bari in comparison with similar samples from Hisin al-Tinat [52]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6018468.150298/6.918.171.737.82.310/element-patterns-lithium-comparison-similar-samples-hisin-tinat.webp)