Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

11

I

UbWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

COUNTERVAILING

POWER

IN

WHOLESALE PHARMACEUTICALS

Sara

F.

Ellison

Christopher

M.

Snyder

Working

Paper

01

-27

July

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Mennorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

at

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

COUNTERVAILING

POWER

IN

WHOLESALE PHARMACEUTICALS

Sara

F.

Ellison

Christopher M.

Snyder

Working

Paper

01

-27

July

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

at

Countervailing

Power

in

Wholesale

Pharmaceuticals

Sara

Fisher Ellison ChristopherM.

Snyder

M.I.T.

George

Washington

UniversityJuly 19,

2001

Abstract: There

are anumber

of theories in the industrial organization literature explaining the conventionalwisdom

thatlargerbuyersmay

have

more

"countervailingpower"

than small buyers,in that they receive

lower

pricesfrom

suppliers.We

test the theories empirically using dataon

wholesale

pricesfor antibiotics soldthrough variousdistributionchannels—

chainand independent

drugstores, hospitals,

HMOs

—

in the U.S. during the 1990s. Price discountsdepend

more on

theability to substitute

among

alternative suppliers thanon

sheerbuyer

size. In particular, hospitalsand

HMOs,

which

can

use restrictive formularies toenhance

their substitution opportunitiesbeyond

those available for drugstores, obtain substantiallylower

prices.Chain

drugstores only receive a small size discount relative to independents, atmost

two

percenton

average,and

then onlyforproducts forwhich

drugstoreshave

some

substitution opportunities(i.e., notforon-patentbranded

drugs).Our

findings areroughly

consistent with collusionmodels

of countervailingpower

and

inconsistent with bargainingmodels and have

implications for recentgovernment

proposals to

form

purchasing

alliances to reduce prescription costs.JEL

Codes:

L43, L65,

D43,

C78

Ellison:

Department

ofEconomics,

M.I.T.,50

Memorial

Drive,Cambridge,

MA

02142;

tel. (617)253-3821;

fax. (617)253-1330;

email sellison@mit.edu. Snyder:Department

ofEconomics,

George

Washington

University,2201

G

StreetN.W., Washington

DC

20052,

tel. (202)994-6581,

fax. (202)994-6147,

emailcmsnyder@gwu.edu.

Ellison thanks theHoover

Institutionand

the Eli Lilly grant to theNBER

for support.Snyder

thanksMIT

and

theRSSS

at the Australian National University for support.The

authors are grateful for helpfulcomments from

Maura

Doyle,Glenn

Ellison,Werner

Guth, Margaret

Kyle,Wallace

Mullin, Ariel Pakes, LarsStole,JeffreyZwiebel,

and seminar

participants attheUniversity of Adelaide, Australian National1

Introduction

Galbraith (1952) suggested that large buyers

have

anadvantage

in extracting price concessionsfrom

suppliers.He

called thiseffectthecountervailingpower

oflarge buyersbecause

he foresaw

it as countervailingthe

market

power

oflarge suppliers. It haslong been

the conventionalwisdom

in the business press that

such

a buyer-size effectexists.'The

conventionalwisdom

was

recentlyin evidence in the

enthusiasm

over collectivepurchasing

websites, thebest-known

ofwhich

was

Mercata,

which

sold items at a pricewhich

declined asmore

customers

signedup

to purchase.As

a columnistwrote soon

afterMercata'

s launch:It's an old idea:

Round

up

abunch

ofpeople

who

promise

tobuy

an itemand

thengo

to themanufacturer

or distributorand

work

out avolume

discount.But add

theInternet, with millions of potential

customers

and

the ability tomodify

prices everysecond,

and

you've

got themakings

of a dramatic transformationin retailing(Boston

Globe, July 11, 1999).

The

subsequent

closureofMercata and

failure of other similar business ventures(MobShop,

LetsBuylt) suggests the

importance

ofunderstanding the sources of buyer-size effects ratherthansimply

accepting theconventionalwisdom

thatsuch

effects exist.The

economics

literature offersa

number

oftheorieson

thesources of buyer-sizeeffects.The

theoriescan

be roughly

dividedintotwo

categories, those involving amonopoly

supplierand

those involvingcompeting

suppliers.^The

first category includesmodels

inwhich

themonopoly

supplier bargains with buyersunder

symmetric

information as inHorn

and

Wolinsky

(1988), Stoleand Zwiebel

(1996b),Chipty

and Snyder

(1999),and

Chae

and Heidhues

(1999a,1999b)

and

inwhich

itmakes

take-it-or-'See, e.g., an article on the power of large cable operators to extract price discounts from program suppliers

(Cablevision, February 1, 1988), an article on thepower ofWal-Marttoextract price discountsfrommanufacturers

{The Guardian (London), July 25, 2000), and thescore ofother business press sources exhibiting the conventional

wisdomcited inScherer andRoss (1990) and Snyder (1998).

^Whilethiscategorizationcapturesthe theories thatturnouttoberelevanttoourparticularempirical application,

itis not exhaustive. The technology ofwarehousing and distribution

may

be such that largebuyers arecheaper tosupply perunit thansmall, inwhich caselargebuyers wouldbeexpected topaylowerprices than smallfor a broad

range ofsuppliermarketstructures (see, e.g.,Lottand Roberts 1991 andLevy 1999). Size discounts in Katz(1987)

and Scheffman and Spiller (1992) can be thought ofas involving potential supplier competition, arising from the threat ofbackward integration by a largebuyer.

leave-it offers

under asymmetric

information as inMaskin

and

Riley (1984).The

models

sharethe

common

implication that there exist conditionsunder

which

buyer-size discountsemerge

inequilibrium with a

monopoly

supplier.The

second

category suggests that competitionamong

suppliers

may

be

crucial for the buyer-size effect to emerge. In thesupergame

framework

ofSnyder

(1996, 1998), tacitly-colluding supplierscompete

more

aggressively for the business oflarge buyers

and

are forced to chargelower

prices to large buyers to sustain collusion.Buyer-size discounts

do

notemerge

with amonopoly

supplier but rather require multiplecompeting

suppliers.

The

two

classes of theories, insum, have

contrasting implications forwhether

thebuyer-size effect

emerges even

with amonopoly

supplier (as in the first class) orwhether

instead thebuyer-size effect only

emerges

if buyers are able to substituteamong

competing

suppliers (asin the

second

class).These

contrasting implications provide the basis of the empirical testswe

conduct

in thispaper

using datafrom

the pharmaceutical industry. In particular,we

studywholesale prices

charged

by

pharmaceuticalmanufacturers

to various buyers including chaindrugstores,

independent

drugstores, hospitals,and

healthmaintenance

organizations(HMOs)

forantibiotics.

Our

data provide aunique

opportunity to test the theories sincewe

observe

buyersof different sizes

—

chain drugstores are larger than independents—

purchasing

drugs providing different substitution opportunities.At

one

extreme, drugstorescannot

substituteaway

from

adrug produced

by

abranded manufacturer

withan unexpired

patent; insuch

markets, drugstoreseffectively face a

monopoly

supplier.At

the other extreme,once

a patent expireson

adrug

and

several generic manufacturers enter, drugstorescan

freely substituteamong

thecompeting

generics.

Another

source of variance in our datais in the substitution opportunities acrossbuyers.By

issuing restrictive formularies, hospitalsand

HMOs

can

controlwhich

drugs

their affiliateddoctors prescribe, effectively allowing their

purchasing

managers

to substituteamong

branded

drugs with similarindications fordrugs

on

patentand between branded and

generic manufacturersamong

multiple genericmanufacturers

and

insome

states can substitutebetween branded and

generics for off-patent drugs, but otherwise

need

to fill the prescriptions theircustomers

bringin as written.

Using

these sources of variation,we

can

identify instances inwhich

buyershave

good

substitition opportunities, large size, both, or neither,and can

therefore isolate the effectthat

each

hason purchase

price.While

we may

have an academic

interestin the sources of countervailingpower

and

may

have

been

fortunate that the pharmaceutical industry provides agood

setting to explore theacademic

question,

our

findings about countervailingpower

in pharmaceuticalshave

policy implications aswell.

The

U.S. federalgovernment

and

individual stateshave designed

anumber

ofbills with thegoal of reducing prescription

drug

costsby

aggregating buyers intolarge health careprocurement

alliances.

At

the federal level, a core proposition of the Clinton health carereform

planwas

that large savings

would

come

from

the formation ofbuyer

alliances{White

House

Domestic

Policy

Council

1993).More

recently, alaw

enacted inMaine

was

based

on

the idea that thecountervailing

power

of an intrastate alliancewould

reduce drug

costs.Maine

Governor

Angus

King

stated:If the [pharmaceutical] industry

can

consolidateand

increase itsmarket power,

socan

we.

We're

going

to bargainon

behalf of50

percent ofour

citizensand

we

think that they deserve thesame

consideration as other groups that get discountsbased

on

their

volume

{New

York

Times,May

12, 2000).Other

stateshave

considered similar legislation or are taking part in discussions about interstatepurchasing

alliances.^The

success ofsuch

proposalssucceeding

hingeson

the nature ofcoun-tervailing

power.

Ifsize alone is not sufficient forcountervailingpower

but suppliercompetitionis also required,

forming

large alliancesmay

not result in substantiallylower

prices unless thepurchasing

manager

can

induce supplier competitionby

being willing to substituteone drug

for'lowa.

New

Hampshire, Washington and West Virginia have created intrastate purchasing cooperatives for theelderly. Vermont and Maryland have considered similar programs to Maine's {New York Times, April 23, 2001).

WestVirginia, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina,

New

Mexico, and Washington collaboratedon a multistateanother.

Consumers

may

oppose

the resulting restriction of choice(similar to themuch-publicized

dissatisfaction with the restriction of choice

and

careby

HMOs),

as noted in the following storyabout a congressional inquiry into the cost savings

from

jointprocurement

by

theDepartment

ofDefense

and

Veterans Administration:'The

driving expectation is that, as thetwo

agenciesbuy

more

ofa particular drug,their leverage . . . will permit

them

to exact discountsfrom

drug

manufacturers,' thereport said.

VA

and Defense

officials said the auditdoes

not take into accountsome

negative consequences, including the likelihood that a joint contract with a single

drug

maker

might

forcemany

patients tochange

medications{Boston

Globe, July 5, 2000).Our

resultsshow

that largebuyers

(chain drugstores) receiveno

discount relative to smallbuyers (independent drugstores)

on

antibiotics with unexpired patents—

antibiotics forwhich

drugstores

have

no

substitution opportunitiesand

thus effectively facemonopoly

suppliers.For

off-patent antibiotics

—

antibiotics forwhich

drugstoreshave

some

substitution opportunites—

chain drugstores receive a statistically significant but small discount relative to independents,

at

most

2%.

Much

larger discounts areobserved

in thecomparison

of hospitalsand

HMOs

to drugstores.While

it is unclearwhether

hospitalsand

HMOs

can

be

characterized asbeing

largeror smaller than drugstores

on

average, it is clear that theyhave

better substitution opportunitiesdue

to their use of restrictive formularies. Hospitals'and

HMOs'

discounts are asmuch

as athird

on

branded

drugs thathave

expiredpatents.These

aredrugs forwhich

hospitalsand

HMOs

can

substitute generics freely; drugstorescan

do

so only to amore

limited extent. Hospitalsand

HMOs

receive discounts of asmuch

as10%

forbranded

drugs with unexpired patents,presumably because

theycan

use the abilitytopurchase

a therapeuticallysimilar substitutewhile

drugstores cannot.

The

implication of our findings foreconomic

theory is that, at least for the wholesalean-tibiotics market,

models

focusingon

competitionamong

suppliers (e.g.Snyder

1996,1998)

areStole

and Zwiebel 1996b; Chipty and Snyder

1999;Chae

and Heidhues

1999a,1999b)

or othermodels

involving amonopoly

supplier(Maskin

and

Riley 1984).The

implication ofour

findingsfor policy is that absent the ability to

be

restrictive,drug purchasing

alliances are not likely togain

much

from

their increased size."*The

fact that hospitalsand

HMOs

receive substantial discounts relative to drugstores is wellknown.

Indeed, the discountswere

the focus ofa high-profile antitrust case in the 1990s.^Our

results

go

beyond

merely

documenting

the presence ofhospital/HMO

discounts:we

provide formal estimates of themagnitude

ofthe discounts,an

analysis ofhow

the discounts vary withthe

market

structure of suppliers, ameasure

of the discountsdue

tobuyer

size alone,and

acomparison

ofthe relativeimportance

ofthe various effects.Our

paper

is part of a larger empirical literaturedocumenting

the existence of buyer-sizeeffects

and

countervailing power.The

literature includes case studies,^ interindustryeconometric

studies,^

and

intraindustryeconometric

studies.^While

these papersdocument

the existence abuyer-size effect, they

do

not provide amore nuanced

test of the sources of those effects, aswe

do.

There

is also a related literatureon

bargainingbetween

buyersand

suppliers in health caremarkets.^

The

focus ofmuch

of this literature is the welfare effects of themonopsony

power

of insurers.

Two

exceptions are CongressionalBudget

Office (1998)and Sorensen

(2001).The

CBO

studieshow

ameasure

ofbuyer

discounts (thedifferencebetween

the lowest price received ''An alternative isfor states simplytoregulate drugprices ratherthan engage in voluntarynegotiations. Indeed,theMainelawcitedabovehasaprovisiontriggeringpricecontrolsifgrouppurchasing doesnotresult insubstantially lower prices. See Dranove and Cone (1985)for a study ofthe effect ofprice regulation on hospital costs.

^SeetheNovember 1997symposiumontheBrand

Name

PrescriptionDrugsAntitrust Litigationin theNovember 1997 issueofthe International Journal oftheEconomics ofBusiness (Freeh, ed., 1997).*See Adeiman (1959) and

McKie

(1959).''See Brooks (1973); Porter (1974); Buzzell, Gale, and Sultan (1975); Lustgarten (1975);

McGuckin

and Chen(1976); Clevengerand Campbell (1977); LaFrance (1979); Martin (1983); and Boulding and Staelin (1990).

^Chipty (1995) findsthat largecable operatorschargelowerprices tosubscribers,possiblyreflectinglowerinput

pricespaid toprogram suppliers.

'See Pauly (1987, 1998); Staten, Dunkelberg, and

Umbeck

(1987); Melnick et al. (1992); Brooks, Dor, andby

any non-government

buyer, reportedunder

theMedicaid

drug

rebateprogram,

and

the averageprice offered to drugstores) varies with the presence of substitution opportunities.

Our

datahave

the virtue of allowing us to identifywhich

type ofbuyer

received the discountsand

thepervasiveness of the discounts

on

average foreach

type of buyer, rather than a single reportedextreme.

More

importantly, there isno

informationon

buyer

size in theCBO

data, so theycannot conduct

the tests involving buyer-size discounts,one

of themain

focuses of our study.The

closestpaper

to ours is concurrent researchby

Sorensen

(2001).His

objective, as is ours,is totest

among

various theories of countervailingpower.

His

results arebroadly consistent withours

though

for a different class of health care expenditure: hospital services.He

findssome

evidence

that large insurers obtain discounts for hospital services, but the size effect is small.More

significantis thediscount obtainedby

insurancecompanies

that are able tochannel

patientsto lower-priced hospitals. In both

our

paper

and Sorensen

(2001), substitution opportunities area

more

important source of countervailingpower

than sheer size.One

difference isour

findingofan interaction

between

sizeand

substitution opportunities,an

interactionwhich

is insignificantin

Sorensen

(2001);however,

themagnitude

ofthe interaction effect inour

results is small.This

detail aside, our papers

can

be

viewed

asbeing

complementary,

providingsome

comfort

in therobustness of the results

and

their applicabilitybeyond

the particularmarket

studied in eitherpaper

individually.Finally, there is an experimental

paper

of relevance. Ruffle(2000)

shows

that larger buyersare

more

likely to use a strategy ofdemand

withholding

to extractlower

prices in a repeatedposted-offer market.

Our

paper

is also part of the literatureon

pharmaceuticals, specifically pharmaceuticalpric-ing.'*'

The

most

closely relatedpaper

on

pharmaceutical pricing isMoore

and

Newman

(1993),one

ofafew

studies oftheeconomic

effects ofrestrictive forrnularies."They

find that restrictive'°See,e.g..Caves,Whinston, andHurwitz(1991);Grabowski and Vernon(1992);Grilichesand

Cockbum

(1994);Baye, Maness, andWiggins (1997); Ellisonet al. (1997);Scott Morton (1997); and Ellison and Wolfram (2000).

formularies

lower

retail expenditureson

drugs butdo

notlower

overall health care expendituresbecause

of input substitution.Our

finding that restrictive formulariesappear

to allow hospitalsand

HMOs

to extract price concessions is related, but our analysis is at thewholesale

ratherthanretail level.

2

Background

2.1

Theory

As

noted in the Introduction, there are anumber

of theoretical paperswhich

show

buyer

sizeconfers countervailing

power

even

with amonopoly

supplier(Maskin and

Riley 1984;Horn and

Wolinsky

1988; Stoleand Zwiebel 1996b; Chipty

and Snyder

1999;and

Chae

and

Heidhues

1999a, 1999b).'^

While

all ofthesemodels

are ofinterestforthe general question ofthe sourcesof countervailing

power,

some

arenotrelevant for our empirical exercise.For

instance, inMaskin

and

Riley (1984), buyers differ not somuch

in size as in the intensity of theirdemand;

size isendogenously determined

by

the size of thebundle

selected.At

least in the short run, the sizeof our buyers, for

example

drugstores, isexogenous,

determined

by

thenumber

of stores inthe chain

and

thenumber

ofcustomers

ateach

store. Also, it is unreasonable toimagine

thatdrugstores, hospitals, or other distribution channels

would

integratebackward

in themanufacture

of drugs, so

Katz

(1987)and Scheffman and

Spiller (1992) are not relevant in the presentcontext.

The

models

of bargainingunder

symmetric

information ofHorn

and

Wolinsky

(1988),Stole

and Zwiebel

(1996b),Chipty and Snyder

(1999),and

Chae

and

Heidhues

(1999a,1999b)

are potentially relevant, though,

and

we

willreview

them

briefly.For

simplicity,we

willreview

Chipty

and Snyder

(1999) as representative of the literature.'^'^There is an additional literature on the effectofbuyer sizeon supplier price when downstream firms compete

(Horn andWolinsky 1988 and Tyagi 2001) which

we

will not treat indetail here.'^Hom

and Wolinsky (1988), Stole and Zwiebel (1996b), and Chipty and Snyder (1999) all share the insightConsider

amarket

with amonopoly

supplierand

three equal-sizedbuyers

having

inelasticdemand

for q units of ahomogeneous

good. LetV{Q)

be

the total joint surplus of buyersand

supplier generated

by

trade ofQ

units.Normalize

the surplusfrom

no

trade for all parties tobe

zero.Suppose

the supplierengages

in independent, simultaneousNash

bargains witheach

buyer

over the transferprice.Each

buyer

conjectures that other buyers bargain successfully withthe supplier in equilibrium. Referring to Figure 1, the object ofnegotiation

between

the supplierand

a givenbuyer

is the marginal surplusA

—

B; assume

a transfer price is agreedupon which

results in an equal division of this surplus,

A-B

Suppose

two

of the three buyersmerge

or otherwiseform

an alliance allowingthem

tobargain as a single unit.

The

unmerged

(small)buyer

continues to obtain surplus given inexpression (1).

The

merged

(large)buyer

bargainsover

surplusA

—

C,

and

obtains half of thisin equilibrium.

Assuming

an

equal division of surplusbetween

the subsidiaries of themerged

buyer, after algebraic manipulation each

can

be

seen to obtainUA-B^B-^^^

(2)

2

V

2 2 ^Merging

effectively allows the buyers to bargainover

inframarginal surplus5

—

C

as well as the marginal surplusA

—

B.

Whether

largebuyers

obtainlower

prices than smalldepends on

therelative values of expressions (1)

and

(2). Ifthe joint surplus function isconcave

as in PanelA

ofFigure 1, then the inframarginal surplus

B

—

C

exceeds

the marginal surplusA

—

B,

implying

and Wolinsky (1988) to allow for

n

buyers and decompose the change in surplus into several components. Stole and Zwiebel(1996b) assumecontracts arenon-binding, appropriate giventheirfocus on intra-firmbargainsbetween workers and managers.One

virtue ofStole andZwiebel's (1996b) framework is that equilibrium is guaranteed to exist,while itmay

not in theconvex casein Chipty and Snyder (1999), though thenon-existence problemin Chiptyand Snyder has since been resolved by Raskovitch (20(X)). The relationship between these papers and Chae and Heidhues (1999a, 1999b) isdiscussed below.

(2)

exceeds

(1), in turnimplying

a subsidiary ofthemerged

buyer

obtainsmore

surplusand pays

a

lower

price than the small.We

have

thusdemonstrated

the existence of cases—

namely

caseswith concave

surplus functions—

inwhich

largerbuyershave

countervailingpower

even

against amonopoly

supplier.The

theorydoes

not guaranteesuch

an

outcome, however;

in theconvex

case in Panel

B

a subsidiary of themerged

buyer

obtains less surplusand pays

a higher pricethan the small.

Unfortunately, the

symmetric

bargainingmodels have

notbeen extended

tomultiple suppliers,soitisdifficulttodeterminethecomparative-static effectof

an

increasein thenumber

of supplierson

price discounts for large buyers. Stoleand Zwiebel (1996a)

show

that their extensiveform

game

generates thesame

allocation as theShapley

value; soone

way

toproceed

would

be

to

compute

theShapley

value in the multiple supplier/multiplebuyer game,

recognizing thelack of

an

extensive-form foundation for theShapley

value in this extension.As

shown

in theAppendix,

theShapley

value calculationsproduce

ambiguous

results: the surpluspremium

thatsubsidiaries of large buyers obtain relative to small

may

increase or decrease as thenumber

ofsuppliers increases.

This

result leadsus to suspect thatbargainingmodels

may

notproduce

robustcomparative

statics resultsconcerning

the effect ofmore

competitive suppliermarket

structureson

the discounts offered to large buyers.Given

theexistence of countervailingpower

forlargebuyersdepends

cruciallyon

theconcavityofthe surplus function, it is

worth

askingwhat

theshape

ofthe surplus function is in themarket

for

wholesale

pharmaceuticals.The

source of concavitycan

be

eitheron

the cost side,from

diseconomies

of scale, oron

the benefit side, sayfrom

negativedemand

externalitieswhich

reduce the value of the product as

more

units are sold.''' It is unlikely that pharmaceuticalmanufacture

exhibits substantialdiseconomies

of scale. It is possible that antibioticshave

aform

of negativedemand

externality, in that resistancesmay

be

more

likely to develop forwidely

'"^SeeChipty and Snyder(1999) for adiscussion offactors producing concavity/convexity in the cabletelevision industry, and an exampleofatest forconcavity/convexity ofthe surplus function.

prescribedantibiotics,

though

we

suspectthatsuch

effectsmay

notproduce

strongconcavities.As

Chae

and Heidhues

(1999a,1999b) show, however,

bargainingmodels

withmonopoly

supplierscan

stillproduce

buyer-size effects in theabsence

of concavities ifthere are risk averse partiesinvolved in the negotiations. Therefore, there

remain a

priorigrounds

to test the bargainingmodels

in the particular context ofthe pharmaceutical industry.In the

second

category of models, theexistenceof buyer-size discounts isrelated to theprocessof competition

among

suppliers.Snyder

(1996,1998) examines

theabilityofcompeting

suppliersto sustain collusion in the presence ofbuyers of varying sizes.'^

For

expositional purposes, herewe

will consider a simplified treatment ofSnyder

(1998), inwhich

buyers

arriveon

themarket

sequentially in

each

of an infinitenumber

of periodsindexed

by

i.'^A

buyer

arriving in periodt has

demand

for St units of the good,each

unitproviding itwith

value v.Assume

StG

[s,s] isindependently

and

identically distributed according todistribution functionF.

The

homogeneous

product is

produced by

N

suppliers,which

have

constantmarginal

and

average cost c<

v,and

which

set pricespu

simultaneouslyeach

period.The

suppliersmay

sustain collusion inthe

supergame

with threats oflow

future prices aspunishment

for undercutting.The

logic ofRotemberg

and

Saloner (1986) suggests that it is difficult for suppliers to collude duringbooms

since the benefit

from

undercutting is large relative to the loss of future (average) profits.The

benefit of undercutting can

be reduced

by

colludingon

alower

price duringbooms.

The

same

intuition holds here: collusionis difficult

when

facinga largebuyer

and

priceneeds

tobe

reduced,resulting in

buyer

discounts.As

a corollary of Proposition 1 inSnyder

(1998), itcan be

shown

that if the following'^Elzinga andMills (1997) presenta staticmodelofduopolycompetitionin whichgreater substitutabilitybetween

products leads to lower prices. Unlike Snyder (1996, 1998), their model does nothave comparative statics results

on buyer size.

'*Adrawback ofthis model is that suppliers

may make

essentially simultaneous sales tobuyers of various sizeseach period in practice (although Scherer and Ross 1990, p. 307, discuss the case of government procurement

auctions fortetracycline in the mid 1950s, which

may

bebettercharacterized as sequential). Snyder (1996) showsthatthesame effects arise in amodel in which buyers of varioussizes purchase simultaneously each period.

conditions hold:

^

<

r^

(3)where

E{x)

—

J^

xdF{x)

is the expectations operatorand

5e

(0, 1) is the discount factor, thenthere exists 5*

e

(s,s)such

that the collusive price in the extremal equilibrium (the equilibriummaximizing

suppHer

profit), p*{st) equalsv

for St<

s*and

declines with St for St>

s*.That

is,buyers smaller than a cutoff are

charged

themonopoly

price; buyers largerthan the cutoff receivean

increasingly large discount. Condition (4) is clearly violated ifN

=

1; in this(monopoly)

case there is

no

problem

of sustaining collusion.The

supplier chargesv

per unit to all buyersregardlessofsize, sothere are

no

sizediscounts.At

theotherextreme, asA'^grows

withoutbound,

eventually condition (3) is violated

and

the only equilibrium involves marginal cost pricing,and

hence

no

discounts for largebuyers. Insum,

as depicted in Figure 2, the collusionmodels imply

that

buyer

sizedoes

not confer countervailingpower

when

facing amonopoly

or sufficientlycompetitive suppliers but

does

forsome

intermediatenumber

of suppliers.The

testable differencebetween

the bargainingand

collusionmodels

iswhether

large buyersreceive a discount

even

inthepresence of amonopoly

seller.An

additional testableimplication ofthe collusion

models

is that large-buyer discountsshould

increase asone

moves from monopoly

to

more

competitive suppliermarket

structures.2.2

Institutional Details

Much

of our empirical strategy hingeson

the existence of different substitution opportunitiesacross types of buyers

and

drugs,which

essentially provides us with variation in thetiveness of the supply side.

The

difference in these substitution opportunitiesstem mainly

from

two

sources: the closeness ofa drug's therapeutic indications to other drugs'and

theinstitutionalconstraints

on

certain buyers' ability to switchbetween

therapeutically similar drugs. In there-mainder

of this subsection,we

will discuss the nature ofsubstitution opportunities inwholesale

pharmaceuticals relevant to our empirical

work;

further detailcan be

found

inElzinga

and

Mills(1997)

and

Levy

(1999).Consider

an illustrativeexample.

Suppose

CVS,

a large chain of retail pharmacies, isnego-tiating with Eli Lilly over the price they will

pay

topurchase

theirdrug

Prozac at thewholesale

level.

They know

thatsome

customers

willcome

in off the street with prescriptions forProzac

that

need

tobe

filled,and

there is littleCVS

cando

at that point to alter the prescription.(The

decision has already

been

made

by

a physician at another locationwho

is difficult to contactand

over

whom CVS

hasno

control.) Eli Lillyknows

thisand views

itself(roughly) as amonopolist

in that transaction. In contrast, a hospital or

HMO

can

enter into negotiationswith

Eli Lillywith the ability to threaten credibly that they will not

purchase

Prozac.The

difference is thata hospital

can

induce or require its physicians to prescribe Paxil or Zoloft instead,drugs with

similar therapeutic properties to Prozac's, ifEli Lilly

does

not offer it favorable contract terms.In other

words,

Eli Lillywould

view

itself ascompeting

against the manufacturers of Paxiland

Zoloft inthis transaction.

Not

onlydo

hospitalsand

HMOs

have

the abilitytomake

such

threats,it is standard to carry through

on

them, resulting inwhat

isknown

as a restrictive formulary, alist of

approved

drugs that affiliated physiciansmay

prescribe.The

ability for purchasers to threatenand

make

such

substitutions varies not just with thetype of purchaser (e.g., drugstore versus hospital or

HMO),

but alsowith the drug.Some

drugs,for instance, are therapeutically

unique

and

must

be

includedon

restrictive formularies.At

theotherextreme, all purchasers

can

fairly easily substituteone

generic for another for an off-patentdrug

with multiple generics.'^ 17It

may

beslightly easier for a hospital tomake

generic-genericsubstitutions over time thanadrugstorebecauseFinally, the case of substituting a generic for a

branded

drug, or vice versa, ismore

compli-cated. Hospitals

and

HMOs

have

excellent substitution opportunities, again using themechanism

of the restrictive formulary.

The

substitution opportunities for drugstores,however,

depend

on

state regulation.

Some

states("mandatory")

mandate

that the drugstoremust

fill the prescriptionwith a generic unless the

customer

specifically requests, or the doctor explicitly notes, that thebranded drug be

dispensed. Inmandatory

states, drugstores' ability to substitutebetween branded

and

generic is constrained.Other

states ("permissive") allow the drugstore tochoose

whether

todispense the

branded

or generic ifneither is explictly requested and/or prescribed. In permissivestates, the drugstore has

some

abilityto substitutebetween branded and

generics.Even

in thesestates, thereis a limit to the ability to substitute

between branded

and

generic: thebranded

pricewill typically

be

higher than the generic since the drugstoremust

carry thebranded

product toserve those

customers

who

bring in a prescription explicitly specifying thebranded

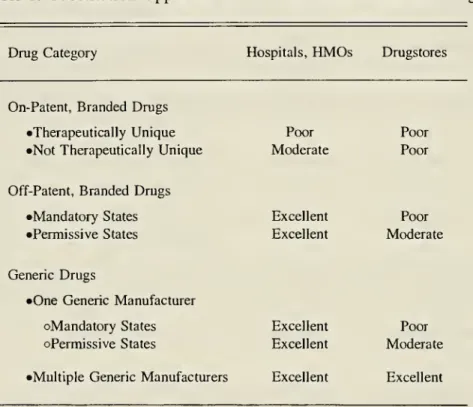

drug.'*Table

1summarizes

the variation in subsitution opportunitesby

type of purchaser, type ofdrug,

and

type of state.Since

our data are collected at the national level,we

willhave

to thinkof drugstore sales as reflecting an average across the different legal

regimes

and

cannot exploitthe variation in that dimension.'^

Note

that during the period our datawere

collected, roughlytwelve states

had

mandatory

substitution laws,and

thirty-eight stateshad

permissive substitutionlaws.

Since our study focuses

on one

therapeutic class, antibiotics, afew

words

shouldbe

saidabout

how

itmight

differfrom

other therapeutic classes. First, the product space is denselypopulated for this class

of

drugs,meaning

that it often is the case that a physician willhave

many

good

alternatives for treating a specific infection. Substitution opportunitiesabound. This

a relatively transient patientpopulationwould not

know

thatthesize,shape,and color ofa tablet wasdifferent thantheonedispensed afew months ago.

'^SeeHellerstein (1998) formore detail on the institutions involving generic substitution.

''Forthe largest chains,itwouldbeappropriatetoaverage acrossstates in anyeventsincetheynegotiate centrally

for thedrugs they retail in stores located throughoutthe country. Forchains or storesoperating in a single state (or

multiple statessharing a

common

legal regime),state-level data would be useful ifitexisted.istrue notjust acrossdifferent drugs butalso

between

branded and

generic versionssince genericpenetration is unusually high in this class.

While

some good

substitution opportunitieswere

importantforour

empiricalexercise,we

were

hoping

to identifysome

therapeuticallyunique drugs

as well, i.e.,drugs

where

even

hospitalsand

HMOs

were

essentially facingmonopoly

supply.An

exhuastive searchconvinced

us that theysimply

did not exist in the case of antibiotics.We

did identify afew

thathad

tobe

includedon most

formularies, forexample

vancomycin,

a last resort antibiotic for methicillin-resistant 5.aureus, but all

were

availablein genericform

orfrom

multiple sources.^*^We

are thereforeunableto exploit variation in substitution opportunities

from

that particular source given the category ofpharmaceutical

we

study.Finally, the issue of

drug

resistancecan complicate formulary

decisions involving antibiotics.One way

to mitigate theproblem

ofbacteriabecoming

resistant to certain antibiotics is to rotatesimilar antibiotics

through

theformulary periodically.The

effect that thispracticemight have on

our analysis is

simply

to decrease the degree towhich

a purchasercan

freely substitute relativetoother therapeutic classes

whose

substitution opportunitiesappear

similar.3

Data

The

data setwe

use toexamine

wholesale

pricing patterns covers virtually all prescriptionan-tibiotics^' sold in the

United

Statesbetween

September

1990

toAugust

1996. Itwas

collectedby

IMS

America,

a pharmaceuticalmarketing

research firm,and

it containsmonthly

wholesalequantities

and

revenuesfrom

transactionsbetween

manufacturers or distributorsand

retailers ofvarious types.

The

data are aggregatedup

to the level of type of buyer.IMS

refers to the type-°We consulted a numberof sources in an attempt to construct a measure oftherapeutic uniqueness. The most

useful was Nettleman and Fredrickson (2001), a handbook intended to teach

new

physicianshow

to prescribeantibiotics. All ofthecompounds that weresuggested to be therapeutically unique turned out tobeoffpatent and

thusto havegeneric substitutes.

^'Ourdata also contain asmall numberofantifungals and antivirals.

ofpurchaser as a "channel ofdistribution,"

and

we

will oftendo

so as well.The

data setcomes

intwo

parts.From

September 1990

toDecember

1991, the data arereported

by two

types ofbuyer: drugstoresand

hospitals, the hospital category covering allnon-federal facilities, i.e., all private

and

nonfederalgovernment

hospitals.From

January 1992

toAugust

1996, the data ismore

refined: drugstores are partitioned into chain drugstores,indepen-dent drugstores,

and

foodstores; the hospital (nonfederal facility) category is retained;and

fournew

categories are introduced—

federal facilities, clinics,HMOs,

and longterm

care—

leading toeight types ofbuyer.^^

We

used

thedata to createtwo

samples.We

createdlongsample spanning

September

1990

toAugust 1996

containing just drugstoresand

hospitalsby

aggregating chaindrugstores,

independent

drugstores,and

foodstores for theJanuary

1992

toAugust 1996

periodto

make

a consistent drugstore series.We

created a shortsample spanning January 1992

toAu-gust

1996

using five of the eightbuyer

types:HMOs,

hospitals, chain drugstores,independent

drugstores,

and

foodstores.We

also included an aggegrate drugstore category (thesum

ofchaindrugstores,

independent

drugstores,and

foodstores)in the shortsample

alongwith

thecomponent

types.

In the

dimension

of product characteristics, the data are quite disaggregated, at the level ofpresentation for

each

pharmaceutical product.A

presentation is a particular choice ofpackaging

and dosage

for a drug, forexample,

150

mg

coated tablets in bottles of 100, or25

ml

of5%

aqueous

solution in a vial for intravenous injection.A

drug

will oftenbe

sold inmany

presentations simultaneously.

Since

the prices reportedby

IMS

in these data willbe

central toour

analysis, it is important^^Federal facilitiesareall typesoffederal government hospitals,nursing homes, andoutpatient facilities. Clinics

include outpatient clinics, urgent care centers, and physician offices. The

HMO

category includes prescriptionsdispensed at

HMO-owned

hospitals and drugstores,not prescriptions dispensed elsewhere but paid forbyanHMO

drugbenefit. The

HMO

channel ofdistribution, then, reflects only a small portion oftheinfluence thatHMOs

and othermanaged care have had on pharmaceutical purchasing. Chain drugstores are in chains offour or more stores.Independent drugstores are owned independently or are in chains not qualifying for thechain drugstore category.

Foodstores aredrugstores located in a foodstore. Longterm care includes nursing homes and convalescent centers

and retail drugstores with more than halfoftheirsales to nursing homes.

Home

health care is not included in thiscategory.

to explain exactly

what

they contain.These

prices are transactions prices, not list prices.They

reflectthe deals negotiated

between

the retailerpurchasing

thedrug

and

thedrug's manufacturer,even

ifthe transaction occurs through a wholesaler. Ifa purchaser negotiates a discount with themanufacturer

and

then purchasesthrough

a wholesaler, they are given a"chargeback"

to reflecttheirdiscount.

Our

data account for chargebacks.Second,

further discounts aresometimes

giventopurchasersin the

fonn

ofrebates.Rebates

are secret, so our datado

not contain them.Such

anomission might have

the potential to seriously biasourresults,but discussion with dataspecialistsat

IMS

and

amarketing

executive at a pharmaceutical firmhave

given us confidence thatwe

understand the nature

and

direction of the bias.It is our understanding

from

these discussions that rebates are not given systematically, saybased

on

aformula depending on volume,

but rather are negotiatedon

acompany-by-company

basis.

During

the period of timecovered

by

our

data, rebates to drugstoreswere

rare.When

rebates

were

given to drugstores, theywere

given for purchasesmediated

by

apharmacy

benefitmanager.

In otherwords,

the priceswe

have

for drugstorepurchases should

be

a fairly accuratereflection of the prices paid

by

drugstores for the portion of theirpurchases

notmediated

by

apharmacy

benefitmanager.

A

biasmay

stillremain

in the drugstorerevenue

variable: omittingrebates results in an overestimate of revenue, akin to considering all drugstore sales to

be

non-mediated

sales,when

only a portion of the saleswould

be non-mediated,

the restmediated

and

possibly reflecting a discount.

Since

we

only use revenues asweights

in theweighted

leastsquares procedure,

and

our results, aswe

discuss below, are quite robust to differentweighting

schemes,

including not weighting at all,we

do

not think secret rebates substantially affectsour

results for drugstores.

Secret rebates,

however,

aremore

pervasive in hospitaland

HMO

sales.Our

prices for hospitalsand

HMOs

would

thusbe

overstatements of the true prices paidby

hospitalsand

HMOs.

This

issue will lead to a bias in our results, understating the discounts that hospitalsand

HMOs

can

extractrelative todrugstores.We

will discussthisbias again in theresultssection, butnote that despite it,

we

find very large discounts for hospitalsand

HMOs

relative to drugstores.For

our

regression analysis,we

have

defined anumber

of variablesand have

included shortdescriptions of

them

inTable

2.A

few

ofthem

need

additional explanation.BRANDED

isa

dummy

variable equalingone

formanufacturer

m

sellingdrug

i ifmanufacturer

m

is the originator ofdrug

i.ONPAT

is aduinmy

variable equalingone

ifno

genericshave

entereddrug

iat

time

t.To

be

precise, a patentcould

have

expired withno

generic entry, but forour purposes,it is generic entry, not patent expiration per se, thatis relevant.

Table

3 presents descriptive statistics for the variableswe

use in the analysis.The

tablecontains

two

sets ofdescriptive statistics,one

for the longsample

with the aggregatebuyer

typesand

one

for the shortsample

with the finerbreakdown

ofbuyer

types.Note

thatNUMGEN

and

ONEGEN

areonly defined for off-patent observations—

hence

thesmallernumber

of observations for thosetwo

variables—

and

theaccompanying

descriptive statistics are thus conditionalon

the observation being off-patent.Considering

the descriptive statistics forprices, itis interesting tonotethatcomparing

averageprices across channels,

both

in the longsample

and

the short sample,does

not reveal largedifferences. Controlling for the

mix

of productspurchased

througheach

of these channels willturn out to

be

important. In particular, hospitals tend tobe

both restrictive purchasers as well aspurchasers of

more

expensive

presentations.The

regression analysis will look at pricedifferencesacross

common

presentations to control for the different mix.Another

interesting feature of thedataisthe relativelysmall fractionof observations

(11%)

fordrugs stillon

patentand

the relativelylarge

mean

ofnumber

of generic competitors (16.8) across off-patent observations. This featureis in part an artifact of the structure of the data:

once

acompound's

patent expiresand

thereis generic entry,

each manufacturer

of thecompound

accounts for a separate observation.This

feature is also

due

to the higher generic penetration of antibiotics relative tomany

other typesof drugs.

Many

of themost

popular

antibiotics are quite old.Old

antibioticsdo

not necessarilybecome

obsolete asnew

ones

enter the market; the available variety, in fact, is an important toolfor

combating drug

resistance.4

Methods and

Results

In order to study empirically the factors that give rise to countervailing

power

and

distinguishamong

various theories,we

willwant

to seehow

priceschange

across different supplyregimes

and

with differentbuyer

sizes. In other words,we

will regress prices (insome

form)

on

a seriesof

dummy

variableswhich

identifythe fourmain

circumstancesunder

which

adrug

is purchased:the

drug

isbranded and

stillon-patent, thedrug

isbranded

but has generic competitors, thedrug

isgeneric but there is only

one

genericmanufacturer

(single-source generic),and

thedrug

is genericand

there are multiple generic manufacturers.We

includedummy

variablesand

interactions todescribe

each

of those four circumstancesand

thenomit

the constant, for ease of interpretation.One

would

alsowant

to include drug, presentation, manufacturer,and

time fixed effects;we

estimate a differenced

model which

accounts for those fixed effects as well as allcombinations

ofthem.

An

additional virtue ofthe differenced specification is that the coefficients are readilyinterpretable. In

sum,

we

estimate a base regression inwhich

thedependent

variable is thedifference in price paid by, for instance, drugstores

and

hospitalsand

the regressors aredummy

variables forcategories of

drug

as described above.To

be

precise, thedependent

variable for thehospital-drugstore regression is

A^Pm^t

=

In {PRICE,,j,m,t,H)-

In{PRICEij^m,t,D).In addition to

examining

the differencebetween

prices paidby

hospitalsand

drugstores,we

lookalso at the difference

between

chainand independent

drugstores,HMOs

and

drugstores,and

HMOs

and

hospitals.We

denote thosedependent

variables as A*^^, A'^^,A^^,

respectively.The

regressionscomparing

price differencesbetween

chainand independent

drugstores give usa fairly clean

comparison

ofthe relativeimportance

ofsizeand

restrictiveness aswe

look acrosscoefficients.

The

regressionscomparing

drugstores to hospitalsand

HMOs

areless cleanbecause

we

do

nothave

informationon

relative size, but these results will still provide informationon

the

importance

of restrictiveness.We

can, of course, control for other covariates in a regressionframework, such

as atime

trend,

which

we

do

insome

specifications. Finally, note that the observations are at the levelof presentation-drug-manufacturer,

and

we

discusshow

toaccount

for the detail of our data incomputing

standard errors below.Table

4

presents resultsfrom

our base regressions.The

firstcolumn

seeks to explain thedifference in prices

paid

by

chain drugstoresand independent

drugstores.Chain

drugstoresand

independent

drugstores should notdiffer intheir restrictiveness—

neithercan be

restrictive against on-patentbrand-name

drugsand

theycan

be

onlyslightly restrictiveagainst off-patentbrand-name

drugs or single source generics, but both

can

be

restrictive against multiple source generics.The

onlydifference is that chain drugstores will tendto

be

large-volume buyerswhereas independent

drugstores will not. Recall that the

dependent

variable is the log ofthe differencebetween

pricespaid

by

chainand independent

drugstores.The

interpretation, therefore, of the 0.002 coefficientestimate

on

ONPAT

x

BRANDED

is that chain drugstorespay

0.2%

more

forbranded

on-patentdrugs than

independent

drugstores do.The

coefficient is not significantly differentfrom

zero,and

given its small standard error,one

shouldconclude

that the effect is precisely estimated tobe

about zero.This

result takenon

itsown

would

tend to castdoubt

on

the relevance of thebargaining

models

in our market. In the face ofmonopoly

supply, large buyers are not able toextract

any

discount at all. Strikingly, the prices theypay

seem

not toeven

reflecttransactions-cost savings

from high-volume

transactions, a portion ofwhich

would

presumably be

passedthrough to the buyer.

The

nexttwo

coefficients represent supplyregimes

inwhich

drugstoresmight

have

limitedability to substitute,

depending on

the state laws.For

the off-patentbranded

drugs, the chainsreceive a small

(0.3%)

but statistically significant discount.The

discount for the single sourcegenerics is larger (1.7%), but only marginally significant.

These

results providesome

tentativesupport for the

dynamic

models

of countervailingpower

in this setting—

holding other factors fixed, as the supplyregime

becomes

slightlymore

competitive, large buyers are able to extractsmall discounts

from

the sellers relative to small buyers.Finally,

somewhat

surprisingperhaps

is the essentially zero coefficienton

the fourth interTaction, indicating that chains receive

no

discounton

multiple source generics.Our

first instinctwould

be

to believe that thedynamic

models

would

predict larger buyer-size effects in thissit-uation,

one

of greater supply competition. It is the case,however,

that if competition is fierceenough

among

suppliers toapproximate

perfect competition,which

may

be

the case for multiplesource generic drugs, then discounts given to large buyers

would

simply

reflect cost differences.The

first coefficient in thisregression implied that cost differenceswere

negligible,which

would

be

consistent with the zero coefficient here. Overall, the results of this regression indicate thatchain drugstores are not receiving substantial discounts relative to independents, either in the

presence or

absence

of restrictiveness.Small

discounts arebeing

extractedwhen

the supplyregime

is slightlycompetitive.The

second

and

thirdcolumns

ofTable4

present the results for the difference in prices paidby

hospitalsand

drugstores. In these regressions,we

have

little information about the relativesizesofthe competitors, but

we

do

know

thathospitalshave

greater substitution opportunitiesdue

totheir abilitytouserestrictive formularies.

To

reiteratethemain

pointsfrom

Section 2, certainlyfor

any

off-patent drug, hospitals, unlike drugstores,can

choose

to stock either thebranded

orgeneric

and

do

notneed

to stock both.For

on-patent drugs, hospitalsmay

have

less discretion,but they

can

choose

to eliminate adrag

from

their formularies if close substitutes existwhereas

drugstores clearly cannot. In other words, these regressions

comparing

hospitaland

drugstoreprices will provide a test of

how

important restrictiveness is.The

resultsfrom

the shortsample

(starting inJanuary

1992)and

thelongsample

(goingback

toAugust

1990)

do

not differ inany

appreciableway,

sowe

will focuson

thelong sample. All fourcoefficient estimates are highly significant

and

are negative,meaning

hospitals receive significantdiscounts relative to drugstores in all circumstances.

The

smallest discountsoccur

for on-patentdrugs,

about

10%,

consistent with hospitals being able to exercise only limdted restrictiveness inthat case.

For

off-patent drugs,where

hospitalscan always be

restrictive, discounts are steeper,including a

35%

discount for the off-patentbranded

drugs.Branded

manufacturersknow

steepdiscounts are necessary to

keep

theirdrugs

on

formularies in the presence of generics. Notably,formultisource generic drugs, hospitals still receive a sizeable discount,

15%,

despite drugstores'ability also to

be

restrictive in thatone

circumstance.One

possible explanation is that althoughdrugstores

can

be

restrictiveagainstmultisourcegenerics, they arereluctant toswitch manfacturersonce

one

ischosen because

theircustomers might complain

aboutchanges

in the size, shape,and

color of the drug.The

hospital population,being

more

transient,would

notbe

as sensitveto

changes over

time. Itseems

unlikely,however,

that this effectwould

be

importantenough

toaccount

for a15%

discount.The

fourthcolumn

ofTable

4 compares

prices paidby

HMOs

and

drugstores.HMOs

would

be

similar to hospitals in their restrictiveness despite theHMO

channel

containing datafrom

on

siteHMO

pharmacies.Not

surprisingly, then, the resultswe

obtainfrom

this regression are similar to theones

for hospitalsand

drugstores, but the discounts are not asdeep and

thecoefficients are not as significant. Interestingly, the

HMO

discount for multisource generic drugs isonly4%,

compared

with15%

for hospitals relative to drugstores.The

HMO

patient population, especiallyone

purchasingfrom

anon

sitepharmacy,

would

be

more

permanent

thanone

at ahospital, so the smaller discount is consistent with the explanation in the

above

paragraph.Recallthatifanything, theseresults are likelyto understatethe true discount given tohospitals

and

HMOs

relative to drugstoresbecause

hospitalsand

HMOs

may

receive secret price discountsnot reflected in our transactions prices.

Finally, the fifth