HAL Id: hal-02597967

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02597967

Submitted on 15 May 2020HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

stakeholder engagement

T. van Ingen, C. Baker, L.F. van der Struijk, I. Maiga, B. Kone, S. Namaalwa,

L. Iyango, B. Pataki, I. Zsuffa, T. Hein, et al.

To cite this version:

T. van Ingen, C. Baker, L.F. van der Struijk, I. Maiga, B. Kone, et al.. Report on stakeholder analysis and strategies for stakeholder engagement. [Research Report] irstea. 2010, pp.235. �hal-02597967�

Draft Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Strategies for Stakeholder Engagement, V2, Dec09 1

Report on Stakeholder Analysis

and Strategies for Stakeholder

Engagement

Deliverable 2.1 Report 3 Date 08/04/10 Lead Author:

Trudi van Ingen (Wetlands International)

Contributors:

Chris Baker (Wetlands International); Luiz Felipe van der Struijk;

Idrissa Maiga and Bakary Kone (Wetlands International Mali);

Susan Namaalwa, Lucy Iyango (Uganda); Beata Pataki, Istvan Zsuffa (Hungary); Thomas Hein, Peter Winkler and Gabi Weigelhofer (Austria);

Stefan Liersch (Germany);

Mutsa Masiyandima, Sylvie Moradet and Edward Chuma (South Africa);

David Matamoros, Gina Garzia (Ecuador) Tom d’Haeyer (Soresma)

Report of the WETwin project: www.wetwin.net

Document Information

Title Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Strategies for Stakeholder Engagement Lead author Trudi van Ingen (Wetland International)

Contributors

Chris Baker; Luiz Felipe van der Struijk; Beata Pataki; Istvan Zsuffa; Stefan Liersch; Idrissa Maiga; Bakary Kone; Thomas Hein; Peter Winkler; Gabi Weigelhofer; Susan Namaalwa; Lucy Iyango; Mutsa Masiyandima; Sylvie Moradet; David Matamoros; Gina Garzia; Tom d’Haeyer

Deliverable number D2.1

Deliverable description Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Strategies for Stakeholder Engagement

Report number D2.1_R3

Version number Final

Due deliverable date Project month 4 (February 2009) Actual delivery date Project month 18 (April 2010)

Work Package WP2

Dissemination level PP (programme participants only) Reference to be used for

citation

WETwin Stakeholder Analysis and Strategies for Stakeholder Engagement

Cover picture Fishing in the Inner Niger Delta by L. Zwarts

Prepared under contract from the European Commission

Grant Agreement no 212300 (7th Framework Programme)

Collaborative Project (Small or medium-scale focused research project) Specific International Cooperation Action (SICA)

Start of the project: 01/11/2008 Duration: 3 years

Acronym: WETwin

Full project title: Enhancing the role of wetlands in integrated water resources management for twinned river basins in EU, Africa and South-America in support of EU Water Initiatives

CONTENTS

Summary ... 6

1 Aim of this report ... 11

1.1 Introduction to WETwin ... 11

1.2 Importance of stakeholder participation ... 13

1.3 Stakeholder analysis and engagement strategies development process in WETwin ... 14

1.4 Purpose of this document... 16

2 Stakeholder analysis... 18

2.1 Steps and tools for stakeholder analysis... 18

2.2 Local context and issues of study site wetlands and river basins ... 20

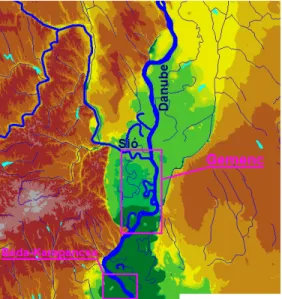

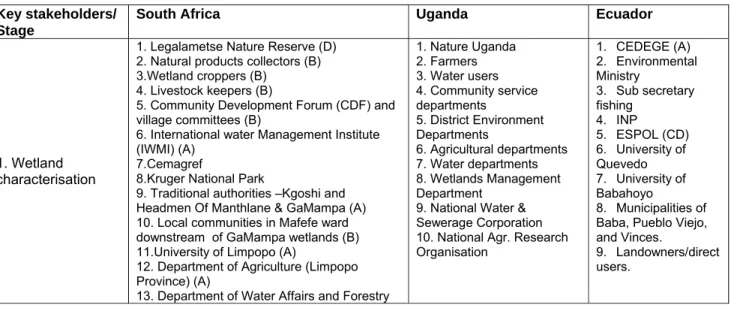

2.2.1 South Africa case study site: 21 2.2.2 Uganda case study sites: 23 2.2.3 Mali case study site: 26 2.2.4 Ecuador case study site 31 2.2.5 Germany case study site: 34 2.2.6 Hungary case study site: 37 2.2.7 Austria case study site: 41 2.2.8 Discussion on scope, issues and context 43 2.3 Identified stakeholders ... 44

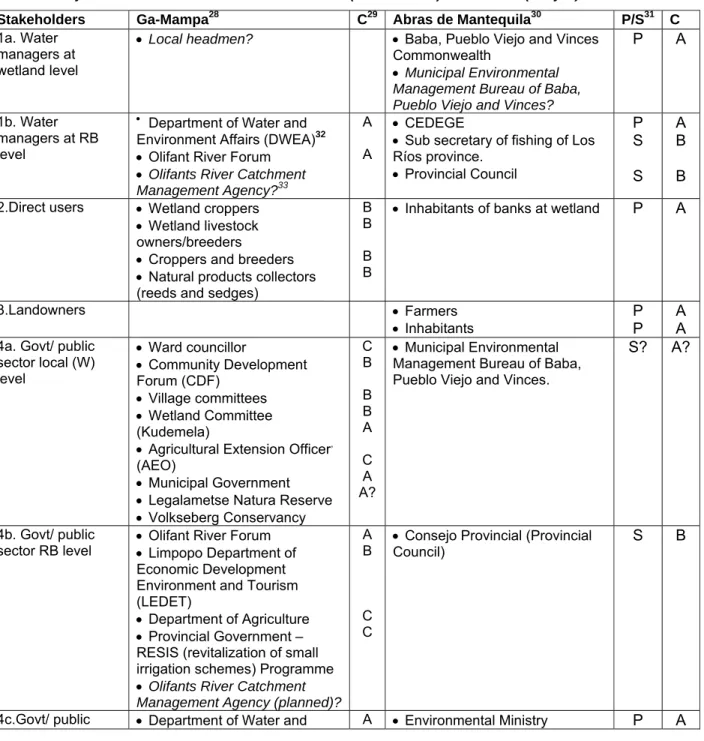

2.3.1 Importance of identifying all stakeholders 44 2.3.2 The importance of identifying stakeholders at different management levels 45 2.3.3 The importance of identifying the specific roles and interests of women 45 2.3.4 Stakeholders identified at the different study sites 46 2.3.5 Discussion on stakeholder identification 47 2.4 Identification of key stakeholders ... 48

2.4.1 Identification of key stakeholders by assessing influence and importance 48 2.4.2 Discussion on identification of key stakeholders 60 2.5 Characteristics, interests, challenges and possible contributions of key stakeholders ... 61

2.5.1 South Africa 61

2.5.2 Uganda 64

2.5.4 Ecuador 74

2.5.5 Germany 76

2.5.6 Hungary 77

2.5.7 Austria 79

2.5.8 Discussion on characteristics, interests, challenges and actions to undertake for key

stakeholders at wetland, river basin and connecting levels 80

2.6 Interrelationships and (possible) conflicts of interests between key stakeholders ... 81

2.7 Summary conclusions and recommendations on stakeholder analysis ... 86

3 Stakeholder engagement strategies... 88

3.1 Steps in developing a stakeholder engagement strategy... 88

3.2 Different stages identified in the WETwin process ... 89

3.3 Key stakeholders to engage in each stage ... 92

3.4 Level of participation of each stakeholder in each stage... 93

3.5 How to engage stakeholders and required actions ... 95

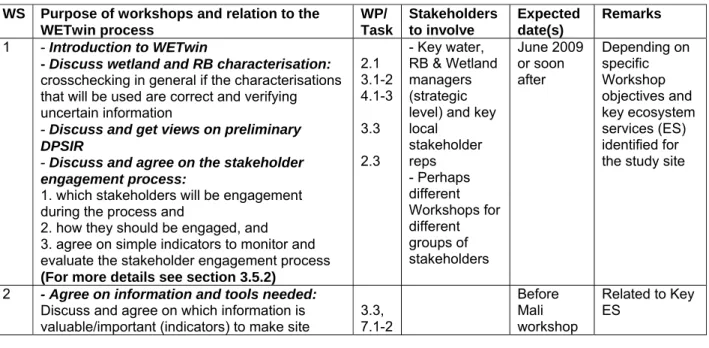

3.5.1 Stakeholder workshops 96 3.5.2 Planning for the future 97 3.6 Stakeholder engagement strategies and plans ... 98

3.6.1 Stakeholder engagement matrix 98 3.6.2 Stakeholder engagement plans 103 3.7 Preliminary conclusions and recommendations for engagement strategies and plans... 104

4 Monitoring and evaluation of stakeholder engagement ... 105

4.1 Purpose ... 105

4.2 Issues to explore and monitor ... 105

4.3 Issues to evaluate ... 107

4.4 How to monitor and evaluate the stakeholder engagement process ... 108

5 List of references ... 110

Annex 1: Summary of South Africa case study ... 112

Annex 2: Summary of Uganda case study... 135

Annex 4: Summary of Ecuador case study ... 178

Annex 5: Summary of Germany case study ... 190

Annex 6: Summary of Hungary case study ... 198

Annex 7: Summary of Austria case study ... 208

Annex 8: DFID influence and importance matrix ... 219

Annex 9: GOPP Participation Analysis Matrix ... 221

Annex 10: Main issues, ecosystem services and trade-offs ... 222

Annex 11: WETwin conceptual framework... 224

Annex 12: Trade-off analysis and Pareto-optimal solutions ... 228

Annex 13: Different levels of participation ... 229

Summary

Introduction to WETwin

To enhance the recognition of the role of wetlands in basin scale water resources management the WETwin project was initiated, aiming to improve drinking water and sanitation services of wetlands; to improve wetland community services while conserving or improving good ecological health; to adapt wetland management to changing environmental conditions; and most importantly, to integrate wetlands into river basin management. For this purpose case study wetlands and their river basins in Africa, South Africa and Europe are ‘twinned’. Thus knowledge and expertise on wetland and river basin management are exchanged. Management solutions are worked out for the case study wetlands with the aim of supporting the achievement of the above objectives. Knowledge and experience gained from these case studies will be summarised in generic guidelines aiming to support achieving project objectives on a global scale.

Importance of stakeholder participation

WETwin puts a lot of emphasis on stakeholder participation as part of the research process, to ensure the constructive engagement with the entire spectrum of societal actors throughout the project life cycle. It considers stakeholder participation as a cross-cutting continuous process throughout the project. Stakeholder analysis and the development of an engagement strategy have been conducted in each developing country case study wetland selected. In the European study wetlands only the stakeholder analysis took place.

Report purpose

This document is the report of the stakeholder analysis and engagement strategy development process that took place during the first year of the WETwin project. It sets out the methodology and gives an account of the stakeholder analysis results and established engagement strategies, and site specific recommendations for further stakeholder engagement of three European and four Southern “twinned” case study sites.

An effort has been made to summarise the information of these seven sites in a comparable format so that in addition a preliminary comparative analysis could be made that can form the basis for further analysis, monitoring and evaluation, and for learning lessons during WETwin that can feed the process of developing generic guidelines for stakeholder engagement. Also recommendations on how the stakeholder process can be monitored and evaluated are given.

Hence, this document should be considered as a baseline and “working” document, whose content should be adapted over time.

Methodology

Guidelines and a standard framework or principles were developed to guide the process of stakeholder analysis and the strategic engagement of key stakeholders in all phases of the project and beyond. The actual stakeholder analysis and the development of a stakeholder engagement strategy were undertaken in the different sites by the case study / Wetland Leaders1 and their subcontractors.

A standard framework and principles for analysis and engagement strategies were provided to create consistency in the methodology so that as much as possible a large degree of comparability between the project sites was achieved. This provides a firmer basis for developing generic guidelines. At the

1 “Wetland Leaders” are ” responsible and overseeing the work done, the timely delivery of reports, the budget and expenses, etc. at the case study sites”

same time the framework provided sufficient opportunity to develop site specific strategies for stakeholder engagement. The general principles facilitated comparison and analysis.

Stakeholder analysis

The stakeholder analysis guidelines provided partners with a standard strategy, steps and tools to identify and analyse stakeholders, their interests, characteristics and their interrelationships. This provided the basis to make informed decisions on which stakeholders to engage in what way in each stage of the WETwin process and beyond.

Because WETwin is dealing with stakeholders at wetland and river basin levels, it is important to consider the following types of stakeholders:

1. Those who are important to engage during WETwin because they are important and/or influential in relation to the identified WETwin issues, e.g. local wetland users, managers and authorities, research institutes;

2. Those who are influential during and after WETwin, e.g. river basin agencies (whether only advisory or with decision taking power) and other institutes influencing the water management or water regime at local and/or downstream level (“decision makers”)

3. Those who should apply or could be instrumental in spreading the outcomes of WETwin (decision support toolbox, site specific management solutions, generic guidelines), e.g. river basin agencies, national authorities dealing with water resources, existing local platforms/fora, NGOs, traditional authorities, women (organisations), etc. (“end users”)

The first type of stakeholders has been identified in all study sites, but needs reviewing in relation to the specific WETwin issues. However, more attention still needs to be given to identifying and engaging the other two types of stakeholders, especially at river basin level.

Most case study sites are part of, or using information of, already existing projects, programmes or studies that might have had another focus. This made it in some cases complex to identify and engage key stakeholders related to the site specific key WETwin issues. As a result at some sites too many key stakeholders have been identified, and therefore the risk exists that efforts are spread too broadly and thinly. With the limited funds available for stakeholder participation it is crucial to prioritise and plan this carefully in the most functional and cost-effective way, so that sufficient funds will be left for the stakeholder participation at the final stages of the project, when for implementation of follow-up activities and sustainability need to be agreed and planned.

In other cases people do not want to interfere with existing stakeholder engagement or decision making processes and are therefore too hesitant to approach or engage certain key stakeholders. In these cases important stakeholders might be overlooked or not sufficiently engaged.

Stakeholder engagement

The stakeholder engagement guidelines were developed to ensure the systematic and constructive engagement of stakeholders throughout WETwin and beyond, by guiding WETwin partners on how and when to engage stakeholders in problem analysis, research design, implementation, the development of decision-support related deliverables and the best approach to share the results and their implications.

WETwin is primarily a research and not an implementation project, although at the same time for the Southern sites a WETwin intention is to find local management solutions. In addition to having to engage different types of stakeholders at wetland and river basis level, this makes it difficult to narrow down to stakeholders that really need to be engaged in relation to the issues or wetland services investigated, and to make choices about the level of engagement. Because perceptions, understanding and/or external circumstances might change it is recommended to review the choice of stakeholders and level of engagement in relation to the issues or wetland services investigated and make this subject to continuous monitoring and adaptation during the life-time of WETwin. This

would ensure most cost-effective use of resources for stakeholder engagement during WETwin and generate suggestions for stakeholder engagement after WETwin at the case study sites.

Another area of concern is the focus on the wetlands level, which is logical from the perspective of the Wetland Leaders. However, as a result river basin level and political stakeholders are too casually engaged. They participate sometimes at workshops, but no commitment or active engagement is asked. Perhaps it is assumed that it is not appropriate for WETwin to ask for commitment before there are any results. However, WETwin is about integrating wetlands and wetland ecosystem cervices into river basin management. In the end it are especially the river basin managers and politicians that should implement the generic guidelines developed for this purpose by WETwin. The chances of this happening are much higher when they are more actively engaged during the development of the generic guidelines. Therefore it is highly recommended to ask for a more active engagement of river basin and political level actors as soon as possible. Although it would be good to obtain their commitment for implementation of the generic guidelines, they might be reluctant to give that commitment at this stage. Nevertheless, it is important to engage them in the development of the generic guidelines, and take their issues, concerns and suggestions into account. It is also necessary to get into discussion with them about the effects of decisions taken about developments upstream (e.g. as in the case of Ecuador building a dam that is going to divert water to another river basin) and how negative effects can be mitigated or avoided. The development of generic guidelines could highly benefit from the practical inputs of this level of stakeholders and will make the generic guidelines more useful to them with a higher chance of being implemented. At the same time this would serve the sustainability of WETwin results.

In more than one site there is mistrust between local users and management authorities and a negative attitude of local communities or certain government institutes. These can have a negative effect on WETwin results and need to be addressed and confidence restored before (compromise) solutions can be found. Likewise good communication to and with stakeholders is important. These issues need to be addressed in the stakeholder engagement plans as well.

Especially at the “Southern” case study sites the process would benefit from engaging women (associations) more than is the case now, especially when dealing with domestic water use and sanitation issues. In some cases little or no attempt seems to be made to engage women or women groups, or only for part of the process even if identified as an important engagement platform.

Monitoring, learning, adapting and the generic guidelines

It is important to explore and learn from the process on how to engage stakeholders for integrating wetland management into river basin management. The purpose of monitoring and evaluating the stakeholder engagement process is on the one hand to ensure continuous constructive engagement of stakeholders throughout WETwin, and on the other hand to develop generic guidelines on how stakeholders at different levels can be engaged to integrate wetland management into river basin management.

The whole process shows that a good stakeholder identification and analysis is not an easy process and that it is even more complicated to put it in a standard format to enable a comparative analysis, because of the differences in context and focus of the different study sites. However, now that this has been established it is worthwhile to invest in monitoring, evaluating and drawing conclusions for the generic guidelines about the three types of key stakeholders mentioned above in relation to integrating wetlands in river basin management.

In relation to stakeholder participation the study sites could learn from each other, by identifying common factors for success as well as common factors for failure (generally the best source for learning). In addition, during WETwin the case study sites could be compared on these factors for success and failure in relation to stakeholder engagement. Conflict management and handling

conflicting interests is such an issue. Some wetlands sites are more advanced than others in resolving conflicting interests and finding management solutions (remaining conflicts are mainly externally induced). For the generic guidelines it would be interesting to learn from this stakeholder engagement process: how have they managed to come to compromise solutions? What were the key factors for success, why? Who were the key stakeholders, why?

In all study sites to a greater of lesser extent there are stakeholders who are not directly interested in the effects their decisions or actions have on (downstream) wetlands or wetland ecosystem services, but whose actions or decisions do have influence (e.g. dams or irrigation schemes). In those cases, for the generic guidelines, WETwin could be a test case on how to engage these stakeholders and get them committed to take the effects of their actions and decisions into account and to avoid or to mitigate negative effects. During WETwin actions go engage those stakeholders more actively could be monitored and the successfulness of these actions evaluated.

It could also be that decisions that have negative effects on wetlands are taken because important and influential stakeholders are not aware or have only little knowledge of wetlands and the ecosystem services they provide, and their importance for the livelihoods of people. WETwin could be a test case to investigate if lack of awareness is a factor in taking negative decisions and if awareness raising about the services and associated values wetlands provide is necessary (especially for “decision takers”).

Where traditional management systems exist or existed it might be interesting to assess what can be learned from this that might be useful for WETwin, e.g. what the institutional arrangements and key stakeholders are or were; what worked and why, and what can be learned from it. For this purpose local “headmen”, “masters” or other traditional leaders are important stakeholders to consult.

What needs to be monitored is if the choices made regarding the selection of key stakeholders and the stakeholder engagement strategy are getting WETwin closer to its end goal. External circumstances might change or assumptions might be wrong: a lot can interfere with what was planned. If things are not going as planned, or not giving the expected (intermediate) outcomes, the question needs to be posed “why not” and what needs to be adapted or improved. Certain activities or even the strategy might need to be adapted. Then a new cycle of “trial, error and learning” starts. For this reason this report, and the study site stakeholder reports, should be considered as a baseline that will need adaptation, and not as an end report. Likewise it is important to identify, learn from and document when something goes very well and what the factors of success are.

The following issues are important to monitor/reflect on e.g. every 6 months at each case study site, to be able to adapt the process of stakeholder engagement during WETwin. Subsequently the same issues can be compared between sites and evaluated to draw conclusions on stakeholder engagement for the generic guidelines:

1. Choice of key stakeholders: the essential stakeholders to engage out of: • different categories,

• the three types of stakeholders (direct wetland users and managers; “decision makers” and “end users of WETwin results”) and

• different levels (wetlands, river basin and political).

2. Level and way of engagement: most functional (i.e. cost-effective) level and way of engagement for different key stakeholders.

3. Addressing problems and obstacles: most important obstacles for successful stakeholder engagement that need to be addressed; and best strategies to address these problems, obstacles and conflicts of interest between stakeholders (within and between levels).

4. Communication, information supply, transparency: most effective communication strategies to ensure stakeholders’ contentment and collaboration.

5. Assumptions: which assumptions about stakeholder engagement have proven to be valuable and true and which ones not?

6. External circumstances: what are (changing) external circumstances with a big impact and what is a good way to react in relation to stakeholder engagement?

7. Sustainability: best strategies to ensure sustainability, i.e. for the use of decision support tools, management solutions, generic guidelines.

8. Factors of failure and success: what can be concluded about factors of failure and success in relation to stakeholder engagement?

This stakeholder engagement monitoring process shouldn’t be seen as an extra burden for reporting purposes, but as a help to stay alert on the stakeholder engagement process and assess if the chosen strategy is effective and to adapt the engagement strategy or plan if necessary. Also, it shouldn’t be complicated, but simple and focused: a matter of staying alert and having open eyes and ears at formal and informal interactions with stakeholders for the above issues, and reflect and report on these.

It is important to agree with key stakeholders on a set of simple indicators of successful stakeholder engagement, related to the above mentioned issues. At the final stages of WETwin these could be evaluated with stakeholders to draw lessons for the local sustainability plan and for the generic guidelines.

Sustainability

It is imperative to consider sustainability throughout WETwin in relation to its different types of stakeholders. The discussion about long term sustainability should be a continuous area of dialogue with key stakeholders to reach an agreed position by the project end. Only then embedding in stakeholder institutions and planning processes can be reached.

Furthermore outputs (publications, tools) need to be adapted and made accessible at the different user levels, i.e. strategic/decision making level and local user and management level. Capacity building (for all levels) to use the tools or guidelines need to be ensured and considered from the onset. This also stresses the need for engaging the stakeholders that need to implement the management solutions and generic guidelines (“end users”) and the ones who should provide the right conditions (“decision takers”).

Stakeholders can’t be separated from the institutions they function in, their composition, legal status, etc. E.g., to what extent local management committees have any real management power depends on to what extent they have a formal/legal status. Therefore, to ensure institutional sustainability, there should be a close collaboration and synergy between WETwin Work Package 2 (dealing with stakeholder participation) and Work Package 4 (dealing with the institutional setting: existing policies and legislation, institutional set-up, key wetland services dealt with, etc.).

1 Aim of this report

1.1 Introduction to WETwin

Wetlands provide important services for local communities (food, drinking water, wild products, etc.). Also wetlands play an important role in water regulation, purification and, depending on its management, the prevention or spreading of water-borne diseases.

Wetlands play a key role in providing drinking water and adequate sanitation. Yet, at the current pace, the Millennium Development Goals for adequate sanitation and drinking water are missed with half a billion people worldwide. It is expected that the increased incidence of droughts, increased water consumption and waste water production only further increase the distance-to-target.

Evidence exists that wetlands are very sensitive towards changes in water allocation, nutrient loading, land-use and economic developments within the entire river basin. Moreover, many wetlands are vulnerable to climate change. As a result, healthy wetlands are the best indicator for a successful integrated water management.

Despite international protection such as through the Ramsar Convention (Global) and Natura 2000 (European Union), many wetlands are not managed wisely and are as a consequence threatened. Several guidelines exist on sustainable wetland management. Yet, these are insufficiently implemented.

As a conclusion, the wise management of wetlands is crucial to maintain its ecosystem services. As wetlands are key elements of a river basin, wetland management affects river basin services, and river basin management influences wetland services. Hence, a need exists to integrate wetlands into river basin management.2

Although the services and functions provided by wetlands are more and more recognised, as well as the influence of upstream activities on downstream areas, wetlands are often overlooked in river basin scale integrated water resource management. To enhance the recognition of the role of wetlands in basin scale water resources management, the WETwin project was initiated.

WETwin aims to:

▪ Improve drinking water and sanitation services of wetlands;

▪ Improve the community services while conserving or improving good ecological health; ▪ Adapt wetland management to changing environmental conditions;

▪ Integrate wetlands into river basin management.

For this purpose case study wetlands in Africa, South Africa and Europe are ‘twinned’ (see figure 1-1). This means that knowledge and expertise on wetland and river basin management is exchanged. Knowledge interchange is implemented through staff exchange between partners and through actively involving the actual operational case studies’ decision-makers in twinning workshops. Locally, stakeholders are also actively involved. Finally, networking with international wetland and river basin platforms also contribute to the global exchange of expertise on wetland management. Management solutions are worked out for the case study wetlands with the aim of supporting the achievement of the above objectives. Knowledge and experience gained from these case studies will be summarised in generic guidelines aiming to support achieving project objectives on a global scale.3

2 Source: WETwin leaflet

Figure 1-1: WETwin case study sites

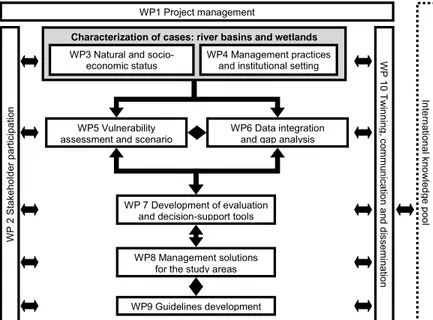

Activities are grouped under thematic Work Packages (WP, see figure 1-2). The work plan departed from the initial characterisation of the selected case studies. Hence, the natural and socio-economic status was assessed in WP3, as well as management practices & institutional settings in WP4, and existing stakeholder structures in WP2. Based on a comparative analysis, data gaps are filled. The developed database is made available afterwards to wetland and/or river basin management authorities (WP6). For each WP a “Work Package Leader” and for each case study site a “Wetland Leader” is responsible and overseeing the work done, the timely delivery of reports, the budget and expenses, etc.

In WP7, a modular and flexible decision-support toolbox is developed, based on locally available tools, which allows to quantify wetland functions and services (WP7); to assess the wetlands’ vulnerability towards climate change, demographic growth, agricultural production and changes in water demand (WP5); and to quantify the impact of management options on the targeted wetland functions and services (WP8).

Given the wide diversity of case studies, the toolbox consists of instruments at different levels of complexity. In order to support decision-makers on wetland and river basin management, the toolbox outputs are translated into ‘policy-tailored’ performance indicators and thresholds values. Case-specific best-compromise solutions are worked out for the case study wetlands with emphasis on the trade-off between drinking water and sanitation services, ecological health and livelihood services. To cope with the vulnerability to future changes, sustainable adaptation strategies are designed as well, with active engagement of stakeholders.

Conclusions will be summarized in a generic guideline, which is aimed to be compatible with RAMSAR, the EU Water Framework Directive, the Millennium Development Goals and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.

Figure 1-2: Work Package flow scheme

1.2 Importance of stakeholder participation

The EU Water Framework Directive (2000) states that “In getting our waters clean, the role of citizens

and citizens' groups will be crucial”: According to this Directive there are two important reasons for

public participation. The first is that the decisions on the most appropriate measures to achieve the objectives of a river basin management or wetland management plan will involve balancing the interests of various groups. It is therefore essential that the process is open to the scrutiny of those who will be affected. The second reason concerns the implementation. The greater the transparency in the establishment of objectives, of measures, and of standards, the greater the care stakeholders will take to implement the plan in good faith, and the greater the power of citizens to influence the direction of environmental protection, whether through consultation or, if disagreement persists, through complaints procedures and courts.

The Water Framework Directive’s Common Implementation Strategy document on Public Participation (2003) identifies several advantages of stakeholder or public participation:

WP 2 Sta keh o lder p art ic ip ati on In te rn atio na l kn ow le d ge poo l WP1 Project management WP 1 0 Tw in ni n g , co m m un ic ati o n an d d is semi natio n

Characterization of cases: river basins and wetlands

WP6 Data integration and gap analysis WP3 Natural and

socio-economic status WP4 Management practices and institutional setting

WP 7 Development of evaluation and decision-support tools WP5 Vulnerability

assessment and scenario

WP9 Guidelines development WP8 Management solutions

for the study areas

Box 1-1 Definitions

Stakeholders are any individuals, groups of people, institutions (government or non-government) organisations or companies that may have a relationship with the project/programme or other intervention at stake. They may – directly or indirectly, positively or negatively – affect or be affected by the process and/or the outcomes. Usually, different sub-groups have to be considered because within a certain group interests may be different (adapted from EU Project Cycle Management Manual, 2001).

Public participation is an approach allowing the public to influence the outcome of plans and working processes, used as a container concept covering all forms of participation in decision-making (WFD Guidance Document No.8 – Public Participation in Relation to the WFD).

• Increased public awareness

• Better use of knowledge, experience and resources from different stakeholders • Increased public acceptance through a more transparent decision-making process • Reduced litigation, delays, and inefficiencies in implementation

• A more effective learning process between the public, government and experts.

1.3 Stakeholder analysis and engagement strategies development process in WETwin WETwin puts a lot of emphasis on stakeholder participation as part of the research process. With Work Package 2 (WP2), on Stakeholder Participation, WETwin aims to ensure the constructive engagement with the entire spectrum of societal actors throughout the project life cycle. It considers stakeholder participation as a cross-cutting continuous process with linkages to all work packages throughout the project.

To mobilize and strengthen the capacities of the local actors in the WETwin project process the following generic issues are explored through stakeholder engagement:

• Relations between (competing) water demands, sanitation, hydrology, ecology, socio-economic activities, sustainability of resources and biodiversity

• Roles and responsibilities of the different actors involved (elected officials and communities, technical services, government services, providers and support structures) and relations between them

• Cultural, organisational and institutional barriers that prevent public participation (link with WETwin WP4).

• Integrated water resources management, role and importance of wetlands, relations with water supply and sanitation wetland functions and valuation, linkages between wetland and river basin.

• Attention regarding gender issues, such as the role of women in water management, wetland wise use and domestic water use.

The approach is to stimulate discussion by stakeholders on the issues, so that awareness is developed/ raised by the stakeholders’ discussions and agreement on approaches and issues achieved in a participatory way.

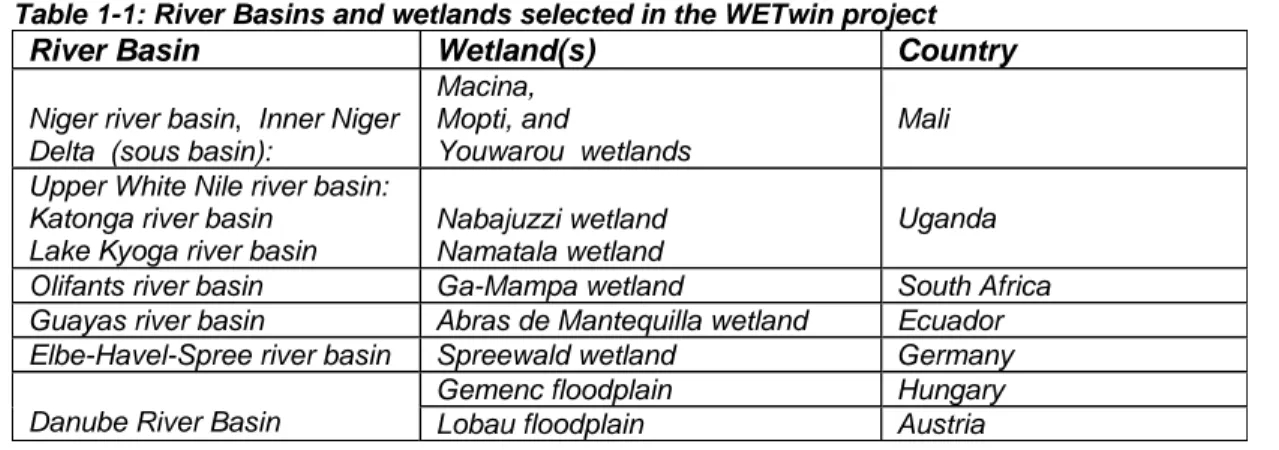

Stakeholder analysis and the development of an engagement strategy have been conducted in each developing country study area selected in the WETwin project (see table 1-1). In the European study areas only the stakeholder analysis took place.

Table 1-1: River Basins and wetlands selected in the WETwin project

River Basin Wetland(s) Country

Niger river basin, Inner Niger Delta (sous basin):

Macina, Mopti, and

Youwarou wetlands

Mali Upper White Nile river basin:

Katonga river basin Lake Kyoga river basin

Nabajuzzi wetland Namatala wetland

Uganda Olifants river basin Ga-Mampa wetland South Africa Guayas river basin Abras de Mantequilla wetland Ecuador Elbe-Havel-Spree river basin Spreewald wetland Germany

Gemenc floodplain Hungary Danube River Basin Lobau floodplain Austria

Stakeholder participation is a complex and delicate process: it usually involves balancing between, and finding compromise solutions, for the often conflicting interests, needs and aspirations of different stakeholders with different levels of decision taking power. This generally requires investing human and financial resources, facilitation skills, and time. In the context of WETwin, stakeholder participation is even more complicated. Not only is the project dealing with 7 “twinned” project sites, at each project site, one also needs to analyse and engage stakeholders at two different levels: at wetland and river basin level. Furthermore two southern countries have more than one site: Mali with three sites in the Inner Niger Delta and Uganda with two wetlands. As a consequence stakeholder analysis needed to take place at ten wetland sites, and the related river basins, and engagement strategies developed for the seven southern wetlands.

To guide the process, guidelines and a standard framework or principles for stakeholder analysis and for the strategic engagement of key stakeholders in all phases of the project and beyond were developed for the WETwin project4. The actual stakeholder analysis and the development of a stakeholder engagement strategy were undertaken in the different sites by the case study / Wetland Leaders and their subcontractors.

The stakeholder analysis guidelines provided partners with a standard strategy, steps and tools to identify and analyse stakeholders, their interests, characteristics and their interrelationships. This provided the basis to make informed decisions on which stakeholders to engage in what way in each stage of the WETwin process and beyond.

The stakeholder engagement guidelines were developed to ensure the systematic and constructive engagement of stakeholders throughout WETwin and beyond, by guiding WETwin partners on how and when to engage stakeholders in problem analysis, research design, implementation, the development of decision-support related deliverables and the best approach to share the results and their implications.

A standard framework and principles for analysis and engagement strategies were provided to create consistency in the methodology so that as much as possible a large degree of comparability between the project sites was achieved. This provides a firmer basis for developing generic guidelines. At the same time the frameworks provided sufficient opportunity to develop site specific strategies for stakeholder engagement. The general principles facilitate comparison and analysis.

The Ga-Mampa wetland (photo: M. Masiyandima)

Most case studies sites are connected or embedded in existing projects, where community based management or planning may already be practised. Also, stakeholder participation might be practised in government planning cycles. In those cases these existing practices needed to be taken into account into the WETwin stakeholder analysis and planning for engagement strategies. Stakeholder participation is also dependent on existing policies, institutional set-up, and the key wetland services dealt with. Therefore the resulting level and way of stakeholder engagement differs from one case study site to another.

1.4 Purpose of this document

This document is the report of the stakeholder analysis and engagement strategy development process that took place during the first year of the WETwin project. It is based on the stakeholder analysis and engagement reports received from the seven case study sites (four Southern and three European sites).

An effort has been made to summarise the information of these seven reports in a comparable format so that instead of only giving an account of the case study stakeholder analysis results and engagement strategies, some preliminary comparison and analysis could take place about the engagement of stakeholders at wetlands and river basin level in endeavours to integrate the two. The study site specific stakeholder reports are given in annex 1-7. Site specific discussions about the stakeholder analysis and engagement strategies are given in boxes and each section will end with more general discussions and comments on the subject.

In addition recommendations on how the stakeholder process can be monitored and evaluated are given, on the one hand to ensure continuous constructive engagement of stakeholders throughout WETwin and beyond (the main objective under WP2 of WETwin), and on the other hand to develop generic guidelines for stakeholder engagement at the wetland, river basin and political level to relate river basin and wetland management in a more integrated way (so to feed into Deliverables under WP9).

Therefore, although this document is mostly an account of the results of the stakeholder analysis and engagement process in the different project sites in the first year, it should not be considered an end-product but as a “working” document and a baseline for analysis, learning, comparison and adaptation. Guidelines and manuals for stakeholder participation in general and for wetlands management (Ramsar, 2003) exist, but WETwin offers the unique opportunity to develop guidelines on how stakeholders at different levels could be engaged to integrate wetland management into river basin management.

A preliminary comparative analysis has been undertaken for this report. This can form the basis for further analysis, monitoring and evaluation, and for learning lessons during WETwin that can feed the process of developing generic guidelines for stakeholder engagement.

The preliminary conclusions and the recommendations in this report are based on the information provided in the study site stakeholder reports and the interpretation of the author based on her experience with multi-stakeholder processes in other southern areas. Because the author is not familiar with all study sites it might be that some information is not correct or that some of the recommended actions already take place but that the author was not aware of this.

2 Stakeholder

analysis

Nowadays it is widely accepted that active commitment and collaboration of stakeholders are essential for wise use and management of wetlands.5 Local people have a rich knowledge base and experience of making a living in a complex environment, and are likely to come up with appropriate solutions to problems.6 They also have the strongest vested interest in good management as they are the main beneficiaries of services and main losers when management at wetland to basin level goes wrong. Furthermore, other stakeholders like managers, politicians, government and public sector agencies, private sector, CSOs, etc., also have an important or influential role in wetland or river management. Therefore, to be effective, a good stakeholder analysis is essential to underpin engagement.

A stakeholder analysis entails identifying all stakeholders likely to affect or to be affected by the project or intervention and the subsequent analysis of their interests, problems, potentials, interrelationships, etc,7 It also entails a system for collecting information about groups or individuals who are affected by decisions, categorizing that information, and explaining the possible conflicts that may exist between important groups and areas where trade-offs may be possible.8

The conclusions of a stakeholder analysis are important to identify the key actors/stakeholders, and to design a strategy for meaningful and (cost) effective stakeholder engagement. It can also help in the design of an intervention or project itself, i.e., a good stakeholder analysis does not only give the foundation for a stakeholder’s engagement strategy but also for targeting interventions and approaches to take.

The stakeholder analysis guidelines developed for the case of WETwin provided the framework for the basic information needed on stakeholders at all study sites and the steps and tools to obtain this information.

This chapter will describe, compare and discuss the results of the stakeholder analysis done in the project sites in the different countries. It is based on the stakeholder analysis and stakeholder engagement reports from the study sites. These reports are compiled per country in annexes 1-7. 2.1 Steps and tools for stakeholder analysis

The Wetland Leaders were requested to go through the following steps and provide for each step the required output:

1. Give a brief description of the local context: geographic scope; WETwin and site specific issues that will be addressed, etc. This information was important to be able to scope and focus on the essential issues and the related key stakeholders. Also other contextual information was important, like to what extent the study site areas are part of another existing programme or study and if some form of stakeholder engagement already exists.

2. Identify and list all stakeholders (primary & secondary) and their interests based on the predetermined focus, with the help of a list of potential types of stakeholder groups provided in the guidelines (see section 2.3). Each stakeholder (sub) group should also be identified as primary or secondary stakeholder, i.e. those directly affected or those who are intermediaries in the delivery process (see box 2.1). The Wetlands Leaders were also requested to pay

5 Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2003) 6 Dodman & Koopmanschap (2005) 7 EU (2001)

special attention to the role and interests of women with their specific roles in domestic water use, use of specific wetland services and (often lack of) involvement and role in water management.

3. Identify key stakeholders with the help of the Influence/Importance matrix of all stakeholders (see annex 8). Key stakeholders are those who can significantly influence, or are important (whose priorities are addressed) to the success of the project or project related outcomes. 4. Identify the main characteristics of key stakeholders with the help of the GOPP9 Participation

Analysis Matrix (see annex 9). With this tool the main characteristics of the key stakeholders, their interests in WETwin, possible contributions they can make to WETwin, challenges that need to be addressed and actions required for engaging key stakeholders could be tabled. Ideally, this should have been defined and agreed upon with the key stakeholders themselves, as well as their influence and importance, for instance at a special workshop (see also section 3.3).

5. Identify and give an overview of interrelationships between actors/stakeholders, especially: • existing formal and informal platforms and networks that can be used for WETwin

purposes,

• power relations and

• existing and potential conflicts (especially related to resource use, and access to and ownership of resources and ecosystem services)

This could be done with the help of tools like Venn diagram’s and network mapping.10

6. The Wetland Leaders were also asked to provide a preliminary agreement/plan for stakeholder engagement throughout the different phases (and after) the WETwin process, indicating which key stakeholders should be involved in each WETwin phase and thereafter. With the help of the stakeholder engagement guidelines this was developed further into a

9 Goal Oriented Project Planning

10 Ingen, van & D’Haeyer: WETwin guidelines for stakeholder analysis (2009)

Box 2-1 Definitions:

Primary stakeholders are those ultimately affected, either positively (beneficiaries) or negatively (for example, those involuntarily resettled). Primary stakeholders should often be divided by gender, social or income classes, occupation or service user groups. In many projects, categories of primary stakeholders may overlap (e.g. women and low-income groups; or minor wetland users and ethnic minorities).

Secondary stakeholders are the intermediaries in the aid delivery process. They can be divided into funding, implementing, monitoring and advocacy organisations, or governmental, NGO and private sector organisations. In many projects it will also be necessary to consider key individuals as specific stakeholders (e.g. heads of departments or other agencies, who have personal interests at stake as well as formal institutional objectives). Also note that there may be some informal groups of people who will act as intermediaries. For example, politicians, local leaders, respected persons with social or religious influence. Within some organisations there may be sub-groups which should be considered as stakeholders. For example, public service unions, women employees, specific categories of staff. This definition of stakeholders includes both winners and losers, and those involved or excluded from decision-making processes.

Key stakeholders are those who can significantly influence, or are important to the success of the project. Influence refers to how powerful a stakeholder is; 'importance' refers to those stakeholders whose problems, needs and interests are the priority of the intervention - if those important stakeholders are not engaged effectively then the project cannot be deemed a 'success'.

more elaborate stakeholder engagement strategy including in what way each of the key stakeholders should be engaged, and to what level each key stakeholder should participate, e.g. being informed, being consulted or more actively involved (see chapter 3).

In case parts of this information already existed through previous surveys and reports, the Wetland Leaders had to check on and collect lacking information, and put everything together in the requested format.

This chapter summarises and discusses the most important information selected from the stakeholder analysis reports from the study sites (for details of each study site see annex 1-7). Because in some cases (countries) only one wetland site is considered and in others more (up to three sites in the Inner Niger Delta in Mali) and because the amount of previous documentation differs in each case, the elaborateness of the information also differs. Nevertheless as far as possible some comparison has taken place and some preliminary conclusions drawn.

Most stakeholder analysis reports were based on previous stakeholder studies done in the context of other projects or programmes. Therefore the WETwin stakeholder analysis reports were often provided in different formats (see annexes). As a result in many of the tables in this chapter the placing of the stakeholder in a certain category is an interpretation of the author of this report.

2.2 Local context and issues of study site wetlands and river basins

In this section (2.2) the scope, main issues and other contextual information of each study site is summarized.

The main issues, ecosystem services and trade-offs identified in the study areas identified at the start of WETwin are indicated in annex 10. Table 2-1 shows the major issues identified at the different study sites at the beginning of WETwin.

Table 2-1: major issues in study areas

Box 2.2: required contextual information

Scope:

Where the wetland is located (geographic location), population size and other facts that might be of interest/important to know.

Focus:

WETwin does not deal with all issues of the wetland management, but with specific issues. Therefore, to be able to select the most relevant stakeholders, it is important to mention which issues.

Other important contextual information:

In most cases the case studies did not start from scratch but are embedded, an extension or an addition to already longer existing projects or studies. In that case this should be shortly described.

WETLAND-COUNTRY climate change and

variability regulation water quantity

nutrient re tention / waste w ater discharge nature conse rvation / restoration dr in king water su pply sanitation / hea lth agricultural water supply pro vision of material for co mm un ity well-being SPREEWALD – GERMANY X X X LOBAU – AUSTRIA X X X X GEMENC - HUNGARY X X X X ABRAS DE MANTEQUILLA- ECUADOR X X X X X NABAJUZZI & NAMATALA-UGANDA X X X X X

INNER NIGER

DELTA-MALI X X X X X X

GA-MAMPA- SOUTH

AFRICA X X X X

2.2.1 South Africa case study site:

River Basin: Olifants rivier Wetland(s): GaMampa (For details see annex 1)

Scope: The wetland study site on which the main focus falls within the Olifants River Basin is the Ga-Mampa wetland of the Mohlapetsi River catchment. It is located between 24° 05' - 24° 20' S and 30° 00' - 30° 25' E in the Limpopo province of South Africa. The Mohlapetsi River originates in the Wolkberg Mountains and is one of the tributaries of the Olifants River. The wetland covers approximately 1 km2 in a total area of 490 km2 at the confluence with the Olifants River. Although only a small tributary, the Mohlapetsi is perceived as important for the hydrology and hence water resources of the Olifants River. The general perception is that this tributary makes a significant contribution to the flow of the lower Olifants, particularly in the dry season. The area falls within the Lepele Nkumpi Municipality, Capricorn District of the Limpopo Province, part of the former Homeland of Lebowa. The majority of people living there are of the Pedi tribe.

The catchment surrounding the wetland comprises relatively natural grassland vegetation, contained within a National Reserve. It is predominantly rural, with a low population density. The total population in the immediate area surrounding the wetland is estimated at about 1700 people. All villages are located and agricultural activities occur in close proximity to the valley bottom and in the wetland. The main sources of livelihoods in the valley come from smallholder agriculture, both in irrigation schemes and in the wetland, and social transfers from the government. In addition to agriculture, the wetland is used for livestock grazing, collection of raw material for craft and building and collection of edible plants. Water is abstracted from the wetland for domestic and irrigation use. Issues:

• The main pressures on the wetland arise from its increasing use for agriculture (in the past 10 years half of the original natural wetland area has been encroached by agricultural plots). This is related to increasing population in combination with limited land availability, which is even worsened by the degradation of neighbouring small-scale irrigation schemes.

• This situation has led to potential tensions between the local community and external stakeholders (sector government departments, local government and environmental lobbyists).

Drainage canal in Ga-Mampa leading to the desiccation of the wetland (photo: M. Masiyandima)

• Depletion of organic matter with potential impacts on morphometry of the wetland and pattern of flow

• Increased erosion of the river bank • Decreased biodiversity

• Reduced capacity for flood attenuation and flow generation • Diminished nutrient assimilative capacity

The study under which stakeholder analyses activities were implemented sought to:

• Analyse trade-offs between the provision of livelihood services (cropping, natural resources collection) versus water regulating services (river flow regulation, flood prevention) as well as • Assess the cumulative effects of the impact of wetland use for livelihoods at river basin level Other contextual information

Data was collected as part of three MSc research projects. These three MSc research were complemented by additional search and analysis of documents available from the worldwide web. The initial stakeholder analysis (2005) was undertaken as the first step of a broader research project seeking to support decisions on wetland management. It was motivated by the need to understand the factors underlying what can be seen as an unsustainable use of the wetland. It was a component of the IWMI11 project of Wetlands, Livelihoods, and Environmental Security.

The second analysis (2006) looked at the interface between wetland policies, laws, and institutions, and local community-based natural resource tenure of wetlands. It was a component of the IWMI project on sustainable Management of Inland Wetlands in Southern Africa.

The main objective of the last study (2009) was to characterise the wetland management policies in South Africa and their implementation on the ground in relation with the Ramsar convention recommendations on wise use of wetlands.

2.2.2 Uganda case study sites:

River Basin: Upper White Nile

Wetland(s): Nabajjuzi and Namatala wetlands (For details see annex 2)

Figure 2-2: Location of the Masaka (Nabajjuzi) and Mbale (Namatala) wetlands in Uganda

Specific research activities under WETwin for the Upper White Nile River Basin are conducted on two sites: the Namatala and Nakayiba-Nabajjuzi wetland systems in Eastern and Central Uganda. Both are near major towns (Mbale and Masaka, respectively) and play an important role in processing wastewater and providing drinking water for the human population. Each one of the towns (both around 70.000 inhabitants) has small laboratories being run at the water treatment plants of the National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC).

Nabajjuzi wetland

Scope: The Nabajjuzi wetland system lies South west of Central Uganda in Masaka district. The system covers 12 sub-counties with a population of 380,000 people living in these sub counties. The Nabajjuzi system is made up of both permanent and seasonal wetland types dominated by papyrus. Crested cranes, white egrets and ibises are some of the birds that frequent it. It has important social and cultural values as it is a source of raw material for crafts and mulching, domestic and livestock water. Its hydrological and physical values are: effluent/sewerage purification, storm water storage, water table discharge/recharge for the surrounding wells and sediment trapping.

Issues:

The population has had a lot of negative impact in the catchment area and on the wetland itself. Before 2005, the wetland was threatened by changes in land-use and major development projects (cultivation in the core wetland area, settlements, soil erosion from deforestation in the river basin). After recognising its critical vital functions, WD together with other stakeholders embarked on a restoration initiative for the Nabajjuzi wetland. All destructive activities were ceased in order to protect the wetland, mainly as a source of water and for sewerage/wastewater purification and storm water storage. Wetlands Division and Masaka District Local Government (MDLG) are preparing to develop a Community Based Wetland Management Plan (CBWMP), for which important input can be provided trough WETwin.

WETwin focus:

• Drinking water supply

• Negative impact of population on catchment and wetland

Tannery treated effluent discharges into the Nabajuzzi wetland (photo: P. Isagara)

Scope: The Namatala system is located south of Mbale Municipality and composed of tributary wetlands of Nashibiso and Masanda, and joining a flood plain with a tributary wetland north of Mbale. Namatala wetland is a very big system that is shared among six districts of Mbale, Pallisa, Tororo, Budaka, Butaleja and Manafwa. It drains into the Mpologoma wetland system. The population in the sub-counties adjacent to the wetland is about 656,299 people. Mbale can be taken as a reference for this wetland system. A management plan was developed but has not been fully implemented yet. Issues:

Important threats exist from changes in land use and major development projects: soil erosion, sewage from Mbale and industrial wastewaters. An additional important contribution of the project can consist of the evaluation of sustainability of proposed management options under changing environmental conditions (climate change).

WETwin focus:

• Nutrient retention • Wastewater discharge

Rice paddies in the Namatala wetland (photo: R. Kaggwa)

Other contextual information for both wetlands:

Both wetland systems play an important role in providing drinking water and processing wastewater. Foreseen interventions include:

• Series of field studies to investigate the hydrological, drinking water supply potential and wastewater purification capacities of the wetlands.

• Stakeholder involvement to improve wetland management.

• Development of decision support tools to facilitate generation of new management solutions. • Analysis of technical, organizational and institutional factors.

In both study sites these activities are integrated with/into already existing efforts by the respective districts and other agencies work, e.g.:

• in Nabajjuzi Nature Uganda has an Environment and Education Programme with Wetlands as one of the aspects,

• in Namatala which is an import bird area it has a Biodiversity Monitoring project.

• For the Districts it is mainly, awareness, sensitization, compliance monitoring and wetland restoration exercises.

2.2.3 Mali case study site:

River Basin: Inner Niger Delta

Wetland(s): Macina, Mopti and Youwarou wetlands (For details see annex 3)

Figure 2-3: Location of the Inner Niger Delta in the Upper Niger basin

The Inner Niger Delta (IND), a large inland flood plain of 30,000 km2 is one of the four major hydrologically distinct components of the Niger Basin. It has international importance for biodiversity and forms a vital part of a regional ecological network, with 3 to 4 million resident or migratory water birds from almost all parts of the African-Eurasian Flyway.

The IND is also critically important for the livelihood support of one million people that depend on the Delta resources and ecosystem. However three-quarters of them live below the poverty level and the region has the lowest social indicators in Mali. Regionally the low level of development and advanced state of degradation of natural resources, as a result of climatic disturbances, human pressure and upstream development, exposes the Delta's population to acute food insecurity. This jeopardizes the balance of the ecosystem in the area as people over-exploit its resource base. Furthermore the IND's location downstream of the Upper Niger means that it is subject to development decisions further upstream; therefore the status of the IND is integrally linked to the effects of water resource management, agriculture and industry.

The Inner Niger Delta (photo: L. Zwarts)

Water supply in the IND is largely directly from the river and waste disposal is often discharged directly into the river. Although pollutant concentrations in the Niger are low, point source gives rise to some highly localized effects; measured data suggest a strong link between these sources and human health. Among diseases encountered in the basin, 80% are linked to drinking water supply and sanitation conditions. The main pollution sources that contribute to these problems are as follows:

a) Human waste disposal: Many medium to large size settlements in and on the edge of the IND have basic sanitary systems that result in solid and liquid domestic wastes and sewerage water being discharged directly into the Delta. Mopti town is one such settlement where it is estimated that 15,000 m2/day domestic wastes are discharged;

b) Industrial waste disposal. These wastes are generally dumped in the Niger River and especially in the Inner Niger Delta, resulting in degraded water quality in some localities which negatively impacts ecosystem health. This creates the conditions where human health can suffer due to contamination of water supply, promotion of conditions for water-borne disease and effects on the population and quality of fish that used for human consumption.

c) Irrigation wastewater disposal. The discharge of irrigation water into the IND can create significant water quality problems in localized areas. These waters carry the fertilizers and pesticides applied to crops which become more concentrated as the water passes through the agricultural system losing water through evaporation. For instance in Office du Niger (Macina) it is recorded that in 1994 6,000 and 4,000 t of urea and phosphates were used to fertilize 47,000 ha of rice fields. As result eutrophication phenomena have been observed with proliferation of invasive weeds (Pistia stratiotes, Eichornia crassipes and Salivinia molesta).

d) Irrigation water management. The irrigation channels of the Office du Niger are inefficient resulting in widespread leakage and ponding of water. For instance nowadays 25,000 m2 water is needed to irrigate 1 ha of rice instead of 15,000 m2 in the past. Associated with this are outbreaks of diseases such as bilharzias, malaria etc.

Rice cultivation in the Inner Niger Delta (photo: B. Kone)

WETwin interventions will take place in Macina (A), Mopti (B) and Youwarou (C) sites in the IND.

(A) Macina wetland

Scope: The area covered by the project on the Macina site is: Macina, Kolongo and Kokry rural districts. The landscape of the rural districts is flat and is made of plains favorable to rice farming and livestock keeping. Macina is an irrigated rice farming area, corresponding to the onset of the IND. In the area the farming system is linked to the management of the Markala dam which takes 3% and 16% of the Niger River discharge during high and weak flood respectively. The year is divided into three climatic periods: dry and cold season, October-February, dry and hot season, March to June and a rainy season, July to September.

Macina rural district is located between the Niger River and the IND. The rural district has 29,585

inhabitants (DRPSIAP, 2007) of Bambara and Marka ethnics, farmers, Bozo and Somono fishermen and Fulani and Diawando cattle breeders. The landscape of the rural districts is flat and made of plains favorable to rice farming and livestock keeping. The district is mostly located in the Niger River valley and stretches along its East part. The landscape is marked by strong human and agriculture pressure. Wild fauna is scarce due to easy access by hunters to the forests during the dry season. Fish fauna is also decreasing and only intensification of fishing effort allow Bozo and Somono to be in business. Nowadays, most of them have become farmers, cattle breeders or are in business.

Kokry rural district: the area covers 80 km² with a total population of 12,058 inhabitants. The

population is made of Bambara, Bozo, Minianka, Peul, Songhoi, Mossi and Dogon. The district is widely irrigated by the Niger River and irrigation channels of the “Office du Niger”. It is located in savanna-Sahelian zone with a flat landscape. The vegetation is a typical savanna-Sahelian one. The economy of the district is based on farming, fishing and cattle breeding. The agricultural production is based on rice, garden vegetables and dry crops.

Kolongo rural district: according to statistics (DRPS, 2007) the district has 28,984 inhabitants.

“Office du Niger” through its Macina department strongly supports development of the district. The landscape is flat and made of floodable plains. The vegetation is made of trees and thorny bushes. Issues:

• It is classified as a high pollution agricultural area. For example, the “Office du Niger”, that is managing the area has used in 1994 5,939 t of urea and 4,055 t of phosphate on 47,000 ha of irrigated area. Also, Zinc sulfate has been used the same year for solving soils deficiency.

• Eutrophication phenomena are perceptible, e.g. invasion of aquatic weeds such as Water Jacinth and Salvinia.

• Water borne diseases in this area are cholera and diarrhea and vector borne diseases are malaria and schistomiasis.

Other contextual information

Beforehand, the Macina zone was not part of Wetland International (WI) projects in the IND, but now it is a site of interest for the WI Wetlands and Livelihood Programme (WLP) through which WETwin is cofounded. Information was gathered from literature reviews for socio economic, hydrologic, water quality, water borne and vector borne diseases data and from previous studies carried out by WI – Mali for ecological data.

(B) Mopti wetland

Scope:

The Mopti wetland is stretching from Mopti Urban to Konna district.

Mopti urban: Since 1995, Mopti urban has grown and expanded to Sevare and Banguetaba and

other neighbouring villages. Mopti is both headquarters of Mopti Region and “Mopti Circle”12. The district is located at the confluence of the Bani and Niger Rivers. It covers 125 km². Mopti is a township inhabited by Bozo, Peul, Bambara, Dogon, Mossi, Sarakolle, Songhoi, Tamasheq , Bobo, Samog and Minianka. Fulani dialect is the most spoken language followed by Bozo. The total population is estimated to be about 100,000 inhabitants. The economy of the district is based on: agriculture, fishing and livestock breeding.

Konna site: Konna rural district is bordered East by Dangol Bore district, North by Ouroube-Doude district, West by Dialloube district and South by Borondougou district. It is located 55 km from Mopti and made of 28 villages. The population is estimated to be 29,857 inhabitants. Ethnics are Peul, Bozo, Rhimabes, Marka, Somono, Dogon, Sonrhai, and Bambara. The most spoken languages are Peul and Bozo. The climate is Savanna-Sahelian; the difference between temperatures (day and night) is huge (20-45˚). The total rainfall varies between 250 to 450 mm and is unequally distributed in time and space. Three seasons are encountered: a rainy season June-October favorable to dry crops, a dry and cold season, November to February, favorable to vegetable farming and a dry and hot season, March to June. There are two types of soils: sand-silt laden soils favorable to rainy