Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la

première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Paper (National Research Council of Canada. Division of Building Research); no.

DBR-P-1062, 1982

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC :

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=afb15b1f-a12c-4baf-8091-75feb26e18d5 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=afb15b1f-a12c-4baf-8091-75feb26e18d5

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur.

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/40001700

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Fire safety of soft furnishings: an overview

).

1062

National Research

Conseil national

.

2

!

*

Council Canada

de recherches Canada

rn

IFIRE SAFETY OF SOFT FURNISHINGS

-

AN OVERVIEWby K. Sumi and M.V. D'Souza

Reprinted from Fire and Materials Vol. 6, No. 1,1982

p. 1 6 - 2 2

DB R Paper 1062

Division of Building Research

I Price $1 .OO

BLOC.

RES.

L I B R A R Y

83-

02-

0 0

B I B L I O T H ~ Q U E

Rech.

B?:im.

L r : I1

OTTAWA NRCC 20751SO

MMAIRE

On donne un a p e r s u , d ' u n p o i n t d e vue c a n a d i e n , d e s r i s q u e s d ' i n c e n d i e pos6s p a r l e s m a t 6 r i a u x d e rembourrage, pour m a t e l a s e t meubles p a r exemple, e t d e s s t r a t 6 g i e s m i s e s e n o e u v r e pour r 6 d u i r e l e nombre d ' i n c e n d i e s m o r t e l s . Des s t a t i s t i q u e s p r o d u i t e s pour l e Canada, l e s i t a t s - ~ n i s e t l e Royawne-Uni i n d i q u e n t qu'une r g d u c t i o n s u b s t a n t i e l l e d e s m o r t a l i t 6 s p a r l e f e u p e u t G t r e o b t e n u e p a r 1 1 a m 6 1 i o r a t i o n d e l a r g s i s t a n c e d e s m a t s r i a u x

B

l ' i n f l a m m a t i o n p a r l e f e u d e s c i g a r e t t e s , c i g a r e s , p i p e s e t a l l u m e t t e s . Es t t o u t a u s s i i m p o r t a n t e n m a t i g r e d e s 6 c u r i t 6 l e comportement p o s t - inflammation d e s m a t 6 r i a u x c a r c e l u i - c i d 6 t e r m i n e l a q u a n t i t 6 d e c h a l e u r , d e fumge e t d e gaz t o x i q u e s lib'erge. Des essaisd e comportement a u f e u d o i v e n t E t r e ex6cutC-s

2

p e t i t e G c h e l l e e tB

g r a n d e G c h e l l e , e t d e s m o d 6 l i s a t i o n s m a t h h a t i q u e s d o i v e n t 8 t r e 6 l a b o r 6 e s pour l a m i s e a u p o i n t d e s s t r a t s g i e s a c t u e l l e s e t f u t u r e s .Fire

Safety of Soft Furnishings-An Overview

K. Sumi and M. V. D'Souza

Fire Research Section, Division of Building Research, National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa KIA 0R6, Canada

The 6re risk posed by soft furnishings such as bedding materials and upholstered furniture and the strategies being developed to reduce the number of fire-related casualities are reviewed from a Canadian point of view. Statistics from Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom indicate that a substantial reduction in the number of fire deaths would be possible if the ability of assemblies of materials to resist ignition by smokers' materials, such as cigarettes and matches, d dbe improved. The post-ignition performance of furnishings

that results in generation of heat, smoke and toxic gases is also important from a safety point of view. A need exists for both full-scale and small-scale fire tests, and for mathematical modelling for present and future control shtegies.

INTRODUCTION Table 1. Fire death statistics 1979- The fire safety of furniture and furnishings is a subject

of growing interest because of increasing awareness of the risk posed by such items in the event of fire. It is clear that soft furnishings such as bedding materials and upholstered furniture can be easily ignited and can be involved in intense, short-duration fires with much smoke and toxic gas. The ignition and subsequent combustion characteristics of such components are therefore of great significance during the initial phase of fire and can determine whether a small one will con- tinue to grow.

The present paper examines statistical data in an attempt to determine the extent of the problem. Ig- nitability tests in use or under consideration for regu- lation of soft furnishings are reviewed, and results of recent research into other related aspects of furniture fire performance are discussed.

FIRE

DEATH STATISTICS: In Canada, the ten provinces, the two territories and

the Federal Government compile fire loss statistics on an annual basis. Through the adoption of the Manual of Uniform Practices for Collecting and Tabulating

I

Fire Loss Statistics1 four provinces are able to collect fire incidence data in much greater detail than was previously possible. Alberta, British Columbia, On- tario and Quebec use this system. In 1979 these provinces represented 82% of the total population and accounted for 7 6 % of the nation's fire deaths. Their detailed data for the have been used to characterize the role of furnishings in residential fires in Canada (Table 1). By definition, residential oc- cupancies include all buildings that provide sleeping accommodation, i.e., hotels, dormitories, mobile homes, one- and two-family residences, apartments and rooming houses. Institutions are classified sepa- rately.Table 1 indicates that 79% of the fire deaths in

Building fire deaths Total

Residential Institutional Other-known

Number of deaths

Alberta BC Ontario Quebec % of total

Residential, material first ignited

Total 49 108 181 100 100.0 Furniture and furnishings 27 46 50 22 33.1 Clothing, textiles 2 10 9 10 7.1 Flammable liquids 3 5 18 17 9.8 Others-known 11 28 33 30 23.3 unknown 6 19 71 21 26.7 Residential, furnishings first ignited

Total 27 46 50 22 100.0 Upholstered furniture 10 11 32 5 40.0 Bedding and mattress 17 20 16 11 44.1

Other 0 15 2 6 15.9

Residential, furnishings, source of ignition

Total 27 46 50 22 100.0 Smokers' materials 25 35 41 18 82.1 Open flames 2 3 2 0 4.8 Others-known 0 6 2 3 7.6 unknown 0 2 5 1 5.5

Canada in 1979 occurred in residential occupancies. In a significant proportion of these cases (33%) furniture and furnishings were identified as the materials first ignited, upholstered furniture, bedding and mattresses being the most common items initially involved (84%.

Smokers' materials were the source of ignition in 82% of the cases. In 27% of residential fire deaths, how- ever, the material first ignited was not determined. These statistics reveal that the scenario of residential fires in which furnishings are the items first ignited by smokers' materials accounted for at least 21% of Canadian fire deaths in 1979.

The scenario concept of fire safety planning was first introduced by Clarke and Ottoson in 1976.6 Using

I

16 FIRE AND MATERIALS, VOL. 6, NO. 1, 1982 @) Wdey Heydeo Ltd, 19822 " ~

/,g-yy

FIRE SAFETY OF SOFT FURNISHINGS-AN OVERVIEW

Table 2. Comparison of two worst fire deaths scenarios

% of fire Deaths

Item Ignition Canada US UK

Rank Occupancy ignited source (1979) (1971-75) (1970) 1 Residential Furnishings Smokers' 21 27 18

material

2 Residential Furnishings Open flame 1 5 3 data from files maintained by the National Fire Pro- tection Association they showed that the residential/furnishings/smoking scenario was by far the most significant cause of fire deaths in the US, with the residential/furnishings/open flame scenario rating a distant second. Table 2 suggests that such scenarios were also significant in Canada and the UK.7 Some caution should be exercised in interpreting these re- sults. however. because of differences in definitions in the three countries. In US statistics, for example, smokers' materials exclude matches, which are re- garded separately as open flames, whereas in the UK and Canada matches are included in the category. Some jurisdictions prefer to differentiate between bed- ding and mattresses while others do not.

~ndications are that a substantial reduction in the number of fire deaths will be possible by improving the ability of furniture and furnishings to resist ignition from small sources such as cigarettes and matches. Several countries have regulations in place or under consideration for assessing the smoulder resistance of mattresses and upholstered furniture. Although most of these tests are basically similar in concept, there are differences that will be discussed in the following section.

In the remainder of this presentation the words 'furniture and furnishings' are used to describe mat- tress plus bedding and upholstered furniture only, since these items are of principal interest in residential fire deaths. Other items normally regarded as furnish- ings, such as curtains, desks, wardrobes, cabinets and occasional furniture, are excluded from the discussion.

cal Bulletin 117 of the Bureau of Home ~urnishings." In Canada a test to determine the resistance to combustion of mattresses ignited by cigarettes was first issued in 1968 and revised as recently as 1979." This test is performed on a small-scale mock-up of the mattress assembly, using a single lighted cigarette as the ignition source. The acceptance criteria are that charring or melting of the specimen surface must not exceed 50 mm in any horizontal direction from the cigarette, and any combustion in the mattress assem- bly must cease 10 min after the cigarette has exting- uished. Ten such tests are conducted.

Studies performed by the Ontario Research Found- ation12 indicate that most currently produced mattres- ses can be made resistant to cigarette ignition if cotton felt, a prime component in most assemblies, is pre- vented from being in direct contact with the surface fabric. As most ticking fabrics used are relatively lightweight (< 150 g mP2), the ticking need not be fire retardant treated since a cellulosic fabric's ability to support smouldering type combustion on its own usu- ally becomes significant at weights above 600 g mP2.

Upholstered furniture

The development of ignitability tests for upholstered furniture has been hindered by the fact that a variety of materials are used in their manufacture and compo- nent geometries and constructions are vastly different. Many fabrics are a mixture of fibres. In addition to fibre composition, the variables known to influence combustion characteristics include fabric weight, con- struction method, backcoating, dye, sizing and other chemical finishes.13 Fabrics and filling materials made from natural substances are subject to a smouldering type of combustion. By comparison, synthetic fibres are primarily thermoplastic and tend to melt and shrink when subjected to smouldering ignition sources, but burn rapidly when exposed to flame.14 Table 3 lists, on a generic basis, the principal component ma- terials used in upholstered furniture.15-l8 These simple

PERFORMANCE TESTS FOR IGNITABILI'N Table 3. Upholstered furniture component materials Mattresses

A standard to assess the resistance of mattresses to smouldering combustion was first published in the US Federal Register in June 1972 and made effective a year later.' The method involves the exposure of the surface of a complete mattress, with and without '

sheets, to a total of 18 lighted cigarettes as the stan- dard ignition source. Acceptance is based on char : length only; it must not exceed 51 mm in any direction

,

from any cigarette. Sampling plans are used to deter- I mine the probability of obtaining acceptable mattres-(

ses from a given production unit.I The State of California has an additional require-

'

ment for non-flame retardant treated polyurethanefoam mattresses. Warning labels are required9 for polyurethane mattresses that do not meet the flame test for resilient cellular materials described in Techni-

% Total market Canada US US US UK Fabrics (1979)15 (1975)" (1977)'~ (1981)17 (1979)" Synthetic fibres: Total 70 35 46 63 62" Nylon 35 Polypropylene 20 Acrylic 15 Natural

fibres: Total 30 65 54 37 38a

Cotton 20

Cottonlacetate 10

Filling Material: (Canada, US, UK almost identical) -Flexible polyurethane foam used very extensively. -Depending on location, may be wrapped with polyester

fibre or cotton batting.

-Fire-retardant treated polyurethane and latex foams sel- dom, if ever, used.

a Estimated.

K. SUM1 AND M. V. D'SOUZA

divisions are useful because they indicate the type of performance tests needed.

In Canada the development of standard test methods pertinent to the fire performance of uphol- stered furniture has just begun. As both the US and UK have appreciable experience in this field, it is of benefit to review their procedures prior to developing future Canadian standards.

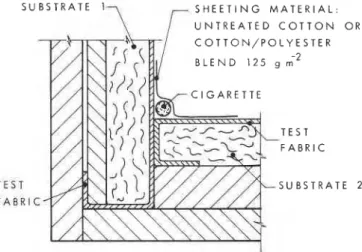

Most existing tests are based on evaluating the resistance of upholstered furniture to cigarette igni- tion. The principal methods under consideration in the US were developed by the National Bureau of Stan- dards (NBS),'~ by an industrial group called the Up- holstered Furniture Action Council (UFAC)19 and by the Department of Consumer Affairs' Bureau of Home Furnishings of the State of Calif~rnia.".~~ Consumer product safety commission proposed standard. The NBS method proposed by the US Consumer Product Safety Commision (CPSC)21 is di- vided into two parts: a fabric classification test and a furniture mock-up test. Using an apparatus similar to that depicted in Fig. 1, individual cover fabrics are assigned a ranking of A, B, C or D depending on the substrate used and the resulting char length when exposed to lighted cigarettes covered with a specified sheeting material. Acceptance criteria are summarized in Table 4. The choice of cotton batt and glass fib- reboard as substrates in the CPSC fabric test has been criticized on the basis that these materials are not commonly used and, further, that glass fibreboard can promote smouldering.13

In the second test of this method the ignition resis- tance of various parts of upholstered furniture items, reproduced in mock-up (Fig. 2) and using the actual material combinations of the furniture item, are meas- ured using lighted cigarettes as the ignition source. The failure criterion in this case is the development of char at any one location greater than 75 rnm from the cigarette. The acceptability of a given combination of materials may be extended to include all other cover fabrics of the given group by employing in the test a standard fabric representative of that group (see Table 4). In this manner the need to evaluate every combi-

SUBSTRATE 1 SHEETING MATERIAL:

UNTREATED C O T T O N OR T E S T FABRl E R C RATE 2

Figure 1. Miniature mock-up test apparatus as used in CPSC and UFAC tests.

Table 4. CPSC fabric classi6cation test (Fig. 1)

Acceptance Criterion

Char Apparent

Length Standard generic Rank Subarate (mm) fabric Listingq4 A 1. Cotton < 38" baW 2. Glass fibre- boardd B Glass fibre- <3V board C Glass 30-75b fibre- board D Glass fibre- >75b board any Class A fabric Cotton or cotton polyester blend, untreated (125 g m-2) Cotton twill, untreated (305 g m-') None, all fabrics must be tested Wool, wool blends Synthetics ( > 350 g m-') Synthetics, light weight cellulosics ( < 250 g m-2) Medium weight cellulosics (250-500 g m-2) Heavy weight cellulosics ( > 500 g m-2)

a All three of three replications. Any one of three replications. "Cotton batt: untreated, density 32 kg mM3. Glass fibreboard: thickness 25 mm, thermal conductivity 0.035 W m-' "C-'.

nation of fabric and filling material is avoided. It should be noted that the above does not apply to Class

D fabrics. Each Class D fabric must be evaluated with the construction material over which the fabric is intended to be used in production furniture.

The NBS study of reference 16 showed that most upholstered furniture available in 1975-76 was easily ignited by burning cigarettes and that such ignitions were clearly related to the type of cover fabric. The standard fabrics selected for groups B and C of the

ASSEMBLY OF FABRIC, F I L L I N G MATERIAL A N D INTERLINER, I ? W E L T E D G E

1

USED FAILURE C R I T E R I O N : CHAR LENGTH AT A N Y O N E L O C A T I O N GREATER THAN 7 5 r n r nFigure 2. Furniture mock-up test apparatus as used in CPSC test.

I

18 FIRE AND MATERIALS, VOL. 6, NO. 1, 1982FIRE SAFETY O F SOFT FURNISHINGS-AN OVERVIEW

CPSC method barely met the failure criteria for their respective classes. It was assumed, therefore, that most other Class B or C fabrics would provide better per- formance than that predicted by use of the respective standard materials. Generally, Class A fabrics were found to be acceptable with most constructions, while Class B fabrics required an interliner between cotton batt and cover fabric. Many Class C and most Class D fabrics were unacceptable when used with filling ma- terials available at the time, indicating the need for a heat dissipating medium beneath the fabric to resist ignition.

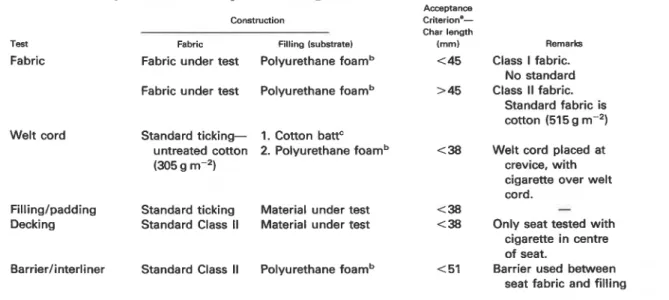

UFAC voluntary action program. The UFAC program, by comparison, evaluates individual component mater- ials for use in any item of furniture. This is done by exposing the test material in combination with stan- dard materials representative of the other components to lighted cigarettes. Several tests are needed, each employing a mock-up similar to that shown in Fig. 1 to rate fabrics, filling (padding), barrier (interlining), welt cord, loose cushion and decking materials. Table 5 summarizes the various requirements.

The essential difference between the CPSC and UFAC methods is that the latter does not assess actual combinations of materials, but rather will permit the use of materials based on successful component test- ing. Recent work1' indicates that this approach does not provide the same level of protection as that offered by the CPSC procedure.

In dividing fabrics into only two classes the UFAC fabric test is less critical than its CPSC counterpart. For example, of five fabrics tested by the UFAC method22 three were awarded a Class I rating and two a Class I1 rating. None was rated as Class A by the CPSC test; instead, one was placed in Class B, two in Class C, and the remaining two in Class D. Further, the fabric recommended by UFAC as a standard for Class I1 is rated by the CPSC test as a good Class D

material.16 Thus, the use of other Class I1 fabrics with acceptable barrier materials, as permitted by UFAC, would result in production furniture having less smoul- der resistance than that evaluated by the barrier test. California regulations. Since October 1975 the State of California has regulated the flammability of uphol- stered furniture sold in that State: using Technical Bulletins 11620 and 117'' to demonstrate compliance. Bulletin 117 prescribes flame tests for fabrics, and flame and cigarette tests for component filling materi- als. Generally, the flame tests involve application of a gas burner flame to the bottom edge of a vertical ,

specimen and criteria based on afterflame, afterglow, char length or weight loss are specified, depending on the type of material. The cigarette tests are also com- ponent material tests and for resilient cellular filling materials utilize an apparatus similar to that shown in Fig. 1. Acceptance criteria are based on char length or weight loss, depending on material type. Bulletin 116'O details requirements for determining the resis- tance of finished products or a mock-up of actual furniture components to cigarette ignition.

British regulations. The Upholstered Furniture (Safety)

regulation^^^

cite British Standard 5852, Part 1 (1979)24 for the assessment of the resistance of assemblies of covers and filling materials to ignition by (a) lighted cigarettes and (b) lighted matches. Indi- vidual items of furniture that currently do not meet the required standards must have warning labels ap- pended. Further, the sale of those items that do not satisfy the requirements of the cigarette test will be prohibited after December 1982. The implementation of a mandatory open flame test is being considered.In the British tests the ignition sources are placed at the junction of the seat and back surface of a mock-up assembly of actual cover and filling materials. The test Table 5. Sommary of UFAC test requirements (Fig. 1)

Construction Test

Fabric

Fabric Filling (substrate)

Fabric under test Polyurethane foamb Fabric under test Polyurethane foamb

Welt cord Standard ticking- 1. Cotton battC untreated cotton 2. Polyurethane foamb (305 g m-')

Fillinglpadding Standard ticking Material under test Decking Standard Class II Material under test

I

I

i

Barrierlinterliner Standard Class II Polyurethane foambI Acceptance Criteriona- Char length (mm) < 45 Remark Class I fabric. No standard Class II fabric. Standard fabric is cotton (515 g m-') Welt cord placed at

crevice, with cigarette over welt cord.

Only seat tested with cigarette in centre of seat.

Barrier used between seat fabric and filling

a All of three replications. Only char on vertical surface of interest.

Standard polyurethane foam of polyether type containing no inorganic fillers or flame retardants. Nominal 51 mm thick, 32.0 kg m-3 density.

"Treated cotton batting: nominal 51 mm thick, 32.0 kg m-3 density.

K. SUM1 AND M. V. D'SOUZA

combination passes the cigarette test if progressive smouldering or flaming of the components does not occur within one hour of the start of the test. A butane flame is used to simulate a lighted match in the open flame test; resistance criteria are the same as for the cigarette test. Progressive smouldering is defined as an exothermic, self-propagating oxidation that is not ac- companied by flaming.

The British procedure is simpler than any proposed in the US. The failure criterion is based on a fairlv liberal time period rather than on the distance of progressive smouldering. In the absence of a fabric classification test, every combination of fabric and filling must be tested, providing greater assurance of safety against accidental ignition, but at an increased cost to the consumer.

Discussion

Several test methods have been developed for deter- mining the resistance of mattresses and upholstered furniture to ignition by smokers' materials. The British procedure for upholstered furniture describes an ex- amination of every combination of fabric and filling material for both cigarette and flaming ignition. To date, only the portion dealing with cigarette ignition has been adopted. In contrast, the two principal US procedures address cigarette ignition only, using fail- ure criteria that appear to be more severe than those adopted in Great Britain. The CPSC proposal ex- amines combinations of actual materials in mock-up, using a fabric classification system to reduce testing costs. The industry proposed procedure entails compo- nent testing to determine an individual material's suitability.

The introduction of only a cigarette test in regula- tions will tend to encourage the use of synthetic ma- terials. Because many are easily ignited by flaming sources, the adoption of a match type ignition resis- tance test similar to that developed in Britain is almost essential.

POST-IGNlTION PERFORMANCE

The discussion to this point has centred on relatively small ignition sources and the probability that furnish- ings will be the first to ignite. Testing of assemblies of materials in the manner described is not adequate, however, for complete assessment of the fire hazard of these products. In the presence of larger sources of heat, fire characteristics such as flame spread, heat release, smoke density and toxicity of combustion products will contribute to the hazard. Major fires have demonstrated that one consequence of flaming ignition of furnishings is the short time from detection to attainment of untenable

condition^.^^

As the pre-flashover phase of an enclosure fire is dependent on a very large number of variables, de- velopment of representative exposure conditions for individual fire characteristic tests is difficult. In the past the study of the burning behaviour of furnishings has usually been conducted under full-size room con-

ditions using 'likely' ignition sources. Performance under the chosen set of conditions, however, cannot always be assumed to represent performance under other diverse conditions, making interpretation of re- sults difficult. The papers under review illustrate cur- rent test methods and possible approaches to the interpretation of results.

Mattresses

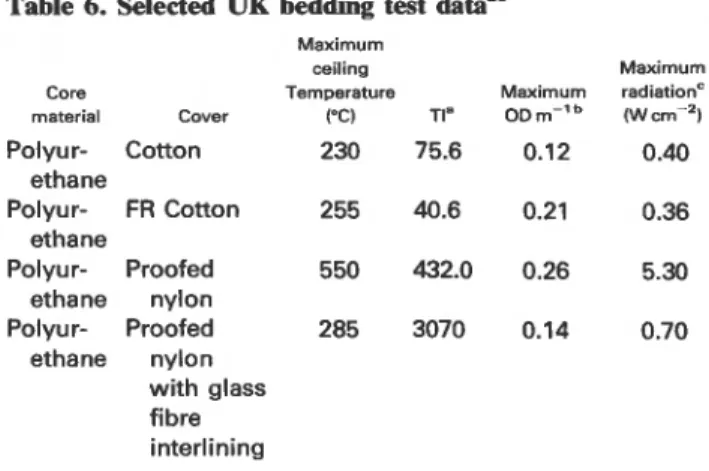

In Britain, Woolley et a1.26 found that the main area of risk in mattress fires involves the unmade part of the bed, represented in their tests by bedclothes folded back. They used a source consisting of four double sheets of newspaper placed on top of a bed in a room-corridor enclosure. Selected test results are shown in Table 6. The tests indicated that the growth of a fire, as represented by gas temperatures in a room, can be delayed by proper selection of mattress cover material and, in certain cases, by the use of protective interlinings. Standard polyurethane foam with a nylon cover represented the worst combination of materials, producing rapid h e growth, high radia- tive heat fluxes, and heavy smoke.

In the US, Davis2' employed a larger source, a trash-filled polyethylene wastebasket placed against the side of the bed, as the primary ignition source in tests run in a room enclosure. The set of arbitrary criteria selected (Table 7) may be considered individu- ally as upper limits for human tenability. The time taken to reach these criteria was used as the basis for hazard analysis (Table 8). Contrary to the conclusions of Woolley et a1.,26 Davis found that mattress core material and total fuel content, not cover material, were important variables in determining post-ignition behaviour. The test mattresses were classified in four groups ranging from those that did not cause any of the limits to be surpassed (such as fire-retardant treated cotton batting) to those that failed all con- straints (such as latex foam and some polyurethanes). The smoke tenability criterion was usually the first to be exceeded.

Table 6. Selected UK bedding test data"

Maximum

ceiling Maximum

Core Temperature Maximum radiationC

material Cover ('C) TIa OD m-lb (W cm?)

Polyur- Cotton 230 75.6 0.12 0.40 ethane Polyur- FR Cotton 255 40.6 0.21 0.36 ethane Polyur- Proofed 550 432.0 0.26 5.30 ethane nylon Polyur- Proofed 285 3070 0.14 0.70 ethane nylon with glass fibre interlining

a TI =Temperature index, defined in Table 9, as calculated by

present authors from data in ref. 26.

Smoke optical density per metre path length.

" Radiometer located 2 m from bed, 0.5 m above surface of bed.

FIRE SAFETY O F SOFT FURNISHINGS-AN OVERVIEW

Table 7. US room burn criteria2'

Room flashover:Heat flux at floor level s- 2.0 W cm-2 Tenability: Heat flux exposure in room <0.25 W cm-2

of origin at end wall

Gas concentrations CO, <8%

0, >14% COHB <25% Smoke obscuration <0.05 OD m-'

Upholstered furniture

In studying upholstered furniture, Woolley et al.14 de- veloped a series of seven flaming ignition sources they judged useful in specifying ignitability requirements for particular occupancies. In terms of calorific output these sources spanned the range from approximately that of a match to that of four double sheets of newspaper. Most assemblies of standard materials were easily ignited by the smallest source. Covers of fire-retardant treated cotton provided definite advan- tages in this regard, but interlinings did not.

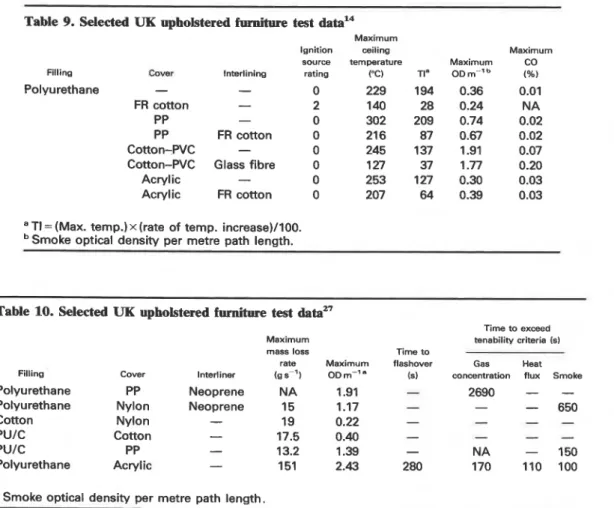

Full-scale burn tests were also conducted in the enclosure used for the mattress tests, employing the largest of the above seven ignition sources. To facili- tate comparison of rates of burning, Woolley et al. introduced the concept of a 'temperature index' (TI) based on the product of the maximum temperature in the room and the maximum rate of temperature in- crease. Data from tests with polyurethane filling are

Table 8. Selected US bedding test d a e

Time to Time to reach reach tenability criteria (s) flashover

criterion Gas Heat Filling Cover (s) concentration flux Smoke

Cotton PVC

-

-

-

-

Cotton Cotton --

- -

Polyurethane PVC and nylon-

710 670 450 Latex PVC and cotton 720 490 460 370 Neoprene Cotton --

-

280included in Table 9. Marked improvements in the rate of fire development were noted when flame-retardant covers and interlinings were used over conventional fillings. The amount of smoke produced varied consid- erably with the assembly.

At the National Bureau of Standards, BabrauskasZ7 opted for 18 double sheets of newspaper as the igni- tion source in evaluating several commercially availa- ble upholstered chairs in a room enclosure. He used the tenability criteria specified by Davisz5 to classify products in the four groups used in the mattress study, and found that the fire performance of the chairs deteriorated with increase in polyurethane foam con- tent. Chair geometry was also considered an important variable (Table 10). The author concluded that since none of the chairs tested was significantly resistant to ignition by a flaming source, a test to evaluate this characteristic was unnecessary.

Table 9. Selected UK upholstered f " test d a d 4

Maximum

Ignition ceiling Maximum source temperature Maximum CO Filling Cwar Interlining rating PC) TIe O D ~ - ' ~ (%)

Polyurethane

-

FR cotton PP PP Cotton-WC Cotton-PVC Acrylic Acrylic - FR cotton-

Glass fibre-

FR cottona TI = (Max. temp.)^ (rate of temp. increase)/100. Smoke optical density per metre path length.

Table 10. Selected UK upholstered furnitore test data2'

Time to exceed Maximum tenability criteria (s) mass loss Time to

rate Maximum flashover Gas Heat Filling Cover Interliner (g S-'1 OD m-la (s) concentration flux Smoke

Polyurethane PP Neoprene NA 1.91

-

2690- -

Polyurethane Nylon Neoprene 15 1.17-

--

650 Cotton Nylon-

19 0.22-

-

-

-

PU/C Cotton-

17.5 0.40-

-

-

-

PU/C PP-

13.2 1.39-

NA - 150 Polyurethane Acrylic-

151 2.43 280 170 110 100a Smoke optical density per metre path length.

K. SUM1 AND M. V. D'SOUZA

Discussion

It is clear that improvements in the post-ignition, pre-flashover performance of currently produced mat- tresses and upholstered furniture are desirable. Suita- ble standard test methods for assessing them are also needed for the benefit of both industry and regulatory authorities.

If the latter subject is of immediate concern, testing of mock-ups or actual items of furniture under full- size conditions can provide the necessary information, although the approach may be expensive and some- what limited in value. This will require the specifica- tion of a standard enclosure and exposure similar, for example, to that currently under development by ASTM for evaluating interior finish material~.~%p- praisal on the basis of ability to transcend any one of

various tenability criteria, as delineated by D a v i ~ , ~ ' is

attractive, especially as the critical levels of the various hazard components can be selected to suit a given occupancy.

A medium term solution that is not restricted to furnishing materials would be to develop a set of complementary small-scale reaction-to-fire tests whose results could be used collectively in analysing the total fire hazard presented by the product. The Interna- tional Standards Organization (ISO) fosters this course of action, but concedes that small-scale tests will never represent all situations encountered in the pre- flashover phase of a fire. Some form of validation testing will therefore be rewired.

sed independently. Such models, however, are not yet available for practical application.

CONCLUSIONS

(1) An appreciable reduction in fire deaths could be achieved by ensuring that upholstered furniture and bedding products are resistant to ignition by smokers' materials. Studies indicate that a signific- ant portion of currently produced furniture will probably not meet these requirements.

(2) Test methods for assessing the ability of assemb- lies of upholstery materials to resist ignition by smoker's materials have been developed and could be implemented as future Canadian standards with minimum modification.

(3) The post-ignition performance of furnishing ma-

terials warrants attention. In the absence of suita- ble bench tests, full-scale testing can be used for evaluation.

(4) The development of small-scale tests that will address the important fire characteristics of a pro- duct during the pre-flashover phase of a fire is judged to be of high priority.

(5) Mathematical analysis of fire growth is regarded as

indispensable in any future control strategy.

Acknowledgement

6f fire processes the m i s is a con&ibution fmm the Division of Building Re-

promise the long term, since and search, National Research Council of Canada, and is published with

their interaction with the surroundings can be addres- the approval of the Director of the Division.

REFERENCES

1. Association of Canadian Fire Marshals and Fire Commis- Saf. J. 2, 39 (1979).

sioners, Manual of Uniform Practices for Collecting and 15. E. Neilsen, Department of Consumer and Corporate Affairs,

Tabulating Fire Loss Statistics (1971). Ottawa, Canada, Private communication, (May 1980).

2. P. Seran, Office of the Fire Commissioner, Province of 16. J. J. Loftus, US Dept of Commerce, NBSlR 78-1438, (1978).

British Columbia, Private communication, (Febuary 1981). 17. Upholstered furniture flammability: Briefing paper,

3. R. R. Philippe, Office of the Ontario Fire Marshal, Private prepared by Fire and Thermal Burn Hazard Program Team,

communication, (July 1980). US Consumer Product Safety Commission (1981).

4. A. Tasiaux, Direction Generale de la Prevention des Incen- 18. R. P. Marchant, Furniture Industry Research Association,

dies, Gouvernement du Quebec, Private communication, Manual No. 17 (1979).

(February 1981). 19. Upholstered Furniture Action Council, Box 2436, High

5. K. A. MacMillan, Department of Labour, Alberta, Private Point, NC 27261, US (1979).

communication, (January 1981). 20. Technical Informatioh Bulletin No. 116, Bureau of Home

6. F. B. Clarke and J. Ottoson, Fire J. 70, 20 (1976). Furnishings, State of California Dept of Consumer Affairs

7. R. Baldwin, G. Ramachandran and D. S. Chandler, Proceed- (1 980)

ings, International Symposium Fire Safety of Combustible 21. Part 1633-Proposed standard fortheflammability (cigarette

Materials, University of Edinburgh, 179 (1975). ignition resistance) of upholstered furniture (PFF 6-81), US

8. Standard for the flammability of mattresses, No. FF-4-72: Consumer Product Safety Commission (1981).

US Federal Register, 38, 15095 (1973). 22. UFAC Voluntary Action Program Chair Tests, Guildford

9. Flammability information package, Bureau of Home Fur- Laboratories, Inc., Greensboro, NC 27408, US (1979).

nishings, State of California Dept of Consumer Affairs 23. The Upholstered Furniture (Safety) Regulations, HMSO,

(1980). (London) (1980).

10. Technical Information Bulletin No. 117, Bureau of Home 24. British Standards Institution, BS 5852: Part 1 (1979).

Furnishings, State of California Dept of Consumer Affairs 25. S. Davis, Proceedings, International Fire, Security and

(1980). Safety Conference, London (1978).

11. Method of test for combustion resistence of 26. W. D. Woolley, S. A. Ames, A. I. Pitt and J. V. Murrell, Fire

mattresses-cigarette test, National Standard of Canada Research Station, Research Note No. 1038, Borehamwood,

CAN2-4.2-M77, Method 27.7 (1979). Herts, UK (1975).

12. H. J. Campbell, Ontario Research Foundation, Private com- 27. V. Babrauskas, US Dept of Commerce, NBSTN 1103 (1975).

munication. 28. ASTM Committee E-5, Private communication (November

13. G. H. Damant and M. A. Young, Laboratory report No. 1980).

SP-77-6, Bureau of Home Furnishings, State of California Dept of Consumer Affairs (1977).

14. W. D. Woolley, S. A. Ames, A. I. Pitt and K. Buckland, Fire Received 18 June 1981

Thiii pablication i s being distributed by the Division of

B u i l d i n g R e s e a r c h of the National R e s e a r c l i Council of

Canada. I t should not be reproduced in whole or in p a r t without p e r m i s s i o n of the original poblisher. The Di-

vision would be glad to b e of a s s i s t a n c e i n obtaining

such permission.

Publications of the Division m a y b e obtained by m a i l - ing the a p p r o p r i a t e r e m i t t a n c e ( a Bank, Exprees, o r P o s t Office Money O r d e r , o r a cheque, m a d e payable to the R e c e i v e r G e n e r a l of Canada, c r e d i t NRC) to the

National R e s e a r c h Council of Canada, Ottawa. K1A OR6.

Stamps a r e not acceptable.

A l i s t of a l l publications of the Division i s available and m a y be obtained f r o m the Publications Section, Division of Building R e s e a r c h , National R e s e a r c h Council of