HAL Id: hal-01617214

https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01617214

Submitted on 16 Oct 2017

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Filament: A Cohort Construction Service for

Decentralized Collaborative Editing Platforms

Resmi Ariyattu, François Taïani

To cite this version:

Resmi Ariyattu, François Taïani. Filament: A Cohort Construction Service for Decentralized

Col-laborative Editing Platforms. 17th IFIP International Conference on Distributed Applications and

Interoperable Systems (DAIS), Jun 2017, Neuchâtel, Switzerland. pp.146-16,

�10.1007/978-3-319-59665-5_11�. �hal-01617214�

Filament: a cohort construction service for

decentralized collaborative editing platforms

A. C. Resmi1 and Fran¸cois Taiani1,2

1

Universit´e de Rennes 1 - IRISA,2 ESIR, Rennes, France {rariyatt, francois.taiani}@irisa.fr

Abstract. Distributed collaborative editors allow several remote users to contribute concurrently to the same document. Only a limited number of concurrent users can be supported by the currently deployed editors. A number of peer-to-peer solutions have therefore been proposed to re-move this limitation and allow a large number of users to work collab-oratively. These approaches however tend to assume that all users edit the same set of documents, which is unlikely to be the case if such sys-tems should become widely used and ubiquitous. In this paper we discuss a novel cohort-construction approach that allow users editing the same documents to rapidly find each other. Our proposal utilises the semantic relations between peers to construct a set of self-organizing overlays to route search requests. The resulting protocol is efficient, scalable, and provides beneficial load-balancing properties over the involved peers. We evaluate our approach and compare it against a standard Chord based DHT approach. Our approach performs as well as a DHT based approach but provides better load balancing.

1

Introduction

A new generation of low-cost computers known as plug computers has recently appeared, offering users the possibility to create cheap nano-clusters of domestic servers, host data and services and federate these resources with other users. These nano-clusters of autonomous users brings closer the vision of self-hosted on-line social services, as promoted by initiatives such as ownCloud [4], or dias-pora [1]. But the initiatives so far primarily focused on the sharing and diffusion of immutable data (pictures, posts, chat messages), and offer much less in terms of real-time collaborative tools such as collaborative editors. In order to fill this gap, several researchers have proposed promising approaches [9, 22, 30] to realize decentralized peer-to-peer collaborative editors.

Most of these works, generally assume that all nodes in the system edit the same document, or the same set of documents, and typically propagate updates using a uniform broadcast primitive. This is unlikely to be the case in very large systems. Propagating changes about every document to the entire system is highly counter-productive and unnecessary. Instead we argue that users editing the same document should be able to first locate each other in order to exchange

updates between themselves. This finding procedure, which we term cohort con-struction, should be efficient, reactive to changes, and robust to failures.

A straightforward choice to realize such a cohort-construction mechanism consists in using a DHT (Distributed Hash Table) [25, 27, 31] to act as an in-termediate rendezvous point between nodes editing the same document. This choice is however sub-optimal: it adds an extra level of indirection in the doc-ument peering procedure, and creates potential hot-spots for nodes handling highly popular documents. It also uses a DHT in a context for which DHTs are typically not designed for: a decentralized collaborative editor will typically host fewer documents than nodes, leading to fewer keys than nodes being stored in the DHT, in contrast to a typical DHT, which is designed to handle the reverse situation, with more keys than nodes.

In this paper we propose Filament, a decentralized cohort-construction proto-col adapted to the needs of large-scale proto-collaborative editors. Filament eliminates the need for any intermediate DHT, and allows nodes editing the same docu-ment to find each other in a rapid, efficient, and robust manner by generating an adaptive routing field around themselves. Filament’s architecture hinges around a set of collaborating self-organizing overlays exploiting a novel document-based similarity metric. Beyond its intrinsic merits, Filament’s design further demon-strates how the horizontal composition of several self-organizing overlays can lead to richer and more efficient services. Simulation results show that in a net-work of 212 nodes, Filament is able to reduce the document latency by around

20% compared to a Chord-based DHT approach.

In the following, we first present the problem we address and our intuition (Sec. 2); we then present our algorithm (Sec. 3), and its evaluation (Sec. 4). We finally discuss related work (Sec. 5), and conclude (Sec. 6).

2

Background, Problem, and Intuition

2.1 Collaborative editing and cohort construction

Distributed collaborative editors allow several remote users to contribute con-currently to the same document. Most of the con-currently deployed distributed collaborative editors are centralized, hosted in tightly integrated environments and show poor scalability [2, 3] and poor fault tolerance. For instance, typical collaborative editors such as Google Doc [3] or Etherpad [2] are limited in the number of users they can support concurrently.

To overcome this limitation, several promising works have been proposed to host collaborative editing platforms in decentralized peer-to-peer architec-tures [9, 22, 30]. However, most of these approaches assume that all users in a system edit the same document. In a large community, this assumption is un-realistic, and users editing the same document need a mechanism to find each other. This is a particular case of peer-to-peer search, which has been exten-sively researched in the past both in unstructured [11, 12, 19, 23] and structured systems, in particular in DHT [25–27, 31]. Unstructured approaches have prob-abilistic guarantees: a resource might be present in the system, but it may not

RPS layer providing random sampling clustering layer gossip-based similarity clustering similarity link random link Alice Bob Carl Dave Ellie Alice Bob Carl Dave Ellie node

Fig. 1. Overlay Architecture

exchange of neighbors lists neighborhood optimization 1 2 Alice Bob Carl Dave Ellie Frank

Fig. 2. P2P neighborhood optimiza-tion

get found unless a flooding or exhaustive multicast strategy is used, which might be very costly in massive systems.

Structured approaches such as DHTs typically have deterministic guaranties in the sense that they are correct and complete, but they assume that the number of items to be stored is much higher than the number of storage nodes avail-able. This is in stark contrast to distributed collaborative platforms, in which the number of documents being edited is smaller than the number of users. Fur-thermore, these systems use consistent hashing techniques in which a node’s role in the system is independent of this node’s particular interests (in our case here documents), thus adding an additional layer of redirection. In case of a highly requested resource, DHTs use load-balancing techniques [16, 24] that typically use virtual nodes or modified hash function [10] to spread the load more evenly. These functions are however reactive, and well suited for content that is mostly read, but less suitable when interest in a document might vary rapidly.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel decentralized service that connects together users interested in the same document without relying on the additional indirection implied by DHTs, while delivering deterministic guaran-tees, contrary to the unstructured networks. Our solution exploits self-organizing overlays with a novel document based similarity metric and is proactively load balancing, in that nodes working on the same documents naturally add their resources to help route their requests to the corresponding document editing community (which we call a document cohort ) and more generally illustrate how an advanced behaviour can be obtained by combining several sub self-organizing overlays to create a routing structure that matches both the expected load and document interests of individual nodes.

2.2 Self-organizing overlays

Our proposal, called Filament, composes together several self-organizing overlay networks to deliver its service. Overlay networks connect computers (aka nodes or peers) on top of a standard point-to-point network (e.g. TCP/IP) in order to add additional properties and services to this underlying network [9, 25–27, 30]. A self-organizing overlay [14, 28] seeks to organize its nodes so that each nodes is eventually connected to its k closest other nodes, according to some similarity function. A self-organizing overlay typically uses a two-layer structure to organize peers (Figure 1). Each layer provides a peer-to-peer overlay, in which users (or

peers) maintain a fixed list of neighbors (or views). For instance, in Figure 1, Alice is connected to Bob, Carl, and Dave in the bottom RPS (Random Peer Sampling) layer, and to Carl and Bob in the upper layer (clustering).

RPS layer allows each peer to periodically obtain a random sample of the rest of the network and thus guaranties the convergence of the second layer (cluster-ing), while making the overall system highly resilient against churn and parti-tions. Peers exchange and shuffle their neighbors list in periodic gossip rounds to maximise the randomness of the RPS graph over time [15]. For efficiency, each peer does not however communicate with all its neighbors in each round, but instead randomly selects one of its neighbors in its RPS view to interact with.

The clustering layer implements a local greedy optimisation procedure that leverages both neighbors returned by the RPS, and current neighbors from the clustering views [14, 28]. A peer will periodically update its list of similar neigh-bors with new neighneigh-bors found to be more similar to them in the RPS layer. This guarantees convergence under stable conditions, but can be slow in large systems. This mechanism is therefore complemented by a swap mechanism in the clustering layer (Figure 2), whereby two neighboring peers (here Alice and Bob) exchange their neighbors lists (Step 1), and seek to construct a better neighborhood based on the other peer’s information (Step 2 in Figure 2).

In figure 2(1) the interests of each user is shown as a symbol associated with them. As we can see Frank, Alice, Bob and Carl share the same interests. So instead of a communication link to Ellie as shown in the random network, it is beneficial for Alice to have a communication link to Carl who shares the same interest as shown in Figure 2(2). Bob applies a similar procedure, and decides to drops Alice for Ellie.

3

System

In a large CE system, users editing the same document need to find each other in order to propagate modifications between themselves. Our approach Filament relies on a novel set of similarity metric, and exploits self-organizing overlays to allows the rapid, efficient, and robust discovery of document communities in large scale decentralized collaborative editing platforms. Each node in the system further maintains a specific view for each document it is currently editing, in order to rapidly propagate the edits: the aim of Filament is to fill this view as rapidly as possible. In addition to this we also need mechanisms that help the system react to changes, and reconnect nodes as required i.e. in cases where a new node joins the system or in cases where a new document is added to a node in the system.

3.1 System model

We consider a network consisting of a large number of nodes representing users N = {n1, n2, .., nN}. The network is dynamic: nodes may join or leave at anytime.

D1 helper overlay document view (cohort) fingers node Alice B C D E F G

Fig. 3. Overlay view

User n - n.id helper overlay list of documents 1 1 kn lh 1 lf

finger list 1 l Individual document view

Fig. 4. Illustration of the system model

existing network, such as the Internet, allowing every node to potentially commu-nicate with any other node as soon as it knows the other node’s identifier. Nodes are organized in a set of interdependent overlay networks (termed suboverlays in the following). For each suboverlay, individual node know the identifiers of a set of other nodes, which forms its neighbourhood (or view ) in this suboverlay. This neighbourhood can change over time to fulfil the overlay network’s objectives. Each node/user n is editing a set of zero or more documents (noted n.D) at a time according to their interests. For the sake of uniformity, both the node ids and document ids are taken from the same id space.

3.2 Filament

As mentioned previously, our approach makes use of a hierarchy of self-organizing overlays inorder to allow the rapid, efficient, and robust discovery of document communities. All the nodes in the system are part of several suboverlays as shown in Fig. 3. A helper overlay (H) is associated with each node. This helper overlay provide short distance routing links within the system, and relies on a document-based similarity function, i.e. a similarity function that uses the set of documents edited by individual nodes in order to compute whether two nodes are close or far. The helper overlay view is initially filled using random peers taken from Random Peer Sampling layer (RPS). As the system executes, n.H is progressively filled with nodes that are similar to but not identical to node n in terms of the documents they edit.

Each node in the system further maintains a specific view for each document it is currently editing, in order to rapidly propagate new edits on these docu-ments. (These edits can then be used to maintain a converged document state at each interested node using existing algorithms [9, 22, 30].) In Fig. 3 nodes Alice, B and C will form a document overlay as all of them are editing document D1. Likewise, the system should insure that a node takes part in all the document overlays pertaining to the documents it is currently editing.

In addition to the above helper and document overlays, each node maintains a set of fingers(F ), which acts as long distance links within the system, in order to create a small world topology, and provide fast routing. Similar to a traditional ring-based DHT, these links also help to rapidly locate collaborating nodes, and to avoid disjoint partitions. A simplified view of the system model is shown in

Table 1. Notations and Entities

n.id node identifier of node n

kn number of documents being edited by node n

n.D list of documents edited by node n depicted as

{dn

1, dn2, ..., dnkn}

n.H helper overlay associated with node n

n.F fingers of node n

n.view(d) set of collaborators for document d contained in node n

Fn[i] node which is the ithfinger of node n

l maximum size of the collaborators list associated with each

document

lh size of helper overlay

lf size of finger list

Fig. 4. It shows the overlays that are associated with a node in the system. Table 1 summarizes the notations that are being used in this paper.

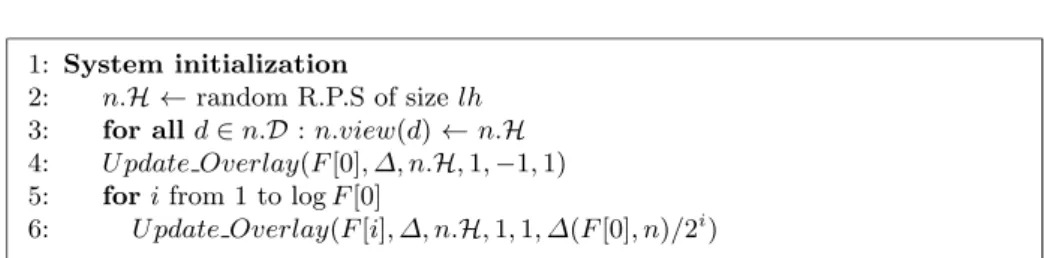

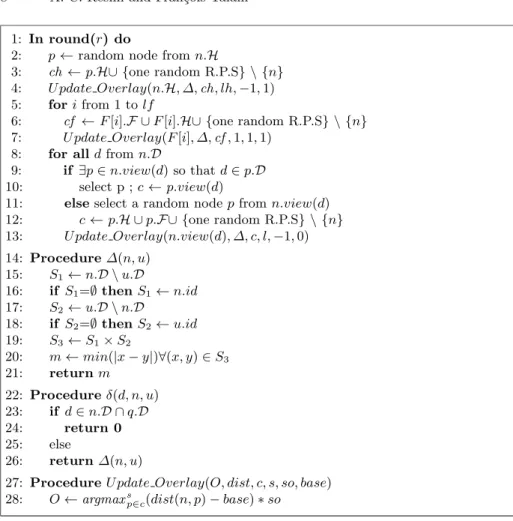

The basic algorithm behind our approach is shown with the help of Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. Figure 5 shows how the system is initialized while Fig.6 shows what the system does in each round.

The proposed algorithms hinge on a novel similarity metric based on docu-ment ids. This similarity metric is described in procedure ∆(n, u) in Fig.6. Each node n has a list of documents n.D associated with it. This list contains the documents that are being currently edited by that node.

Given two nodes and the list of documents being edited by that nodes, the similarity metric in our approach is the smallest distance between the non-identical documents contained by it. For example suppose node A is editing documents 5, 3 and 8 while node B is editing documents 3, 11 and 9 then the similarity between them is taken as 1 which is the difference between 8 and 9. The identical documents being edited by them are not taken into consideration here. The key to the faster convergence of our system is the novel similarity metric which helps in finding nodes which are similar but not identical in their interests.

The initialization stage is pretty straightforward. The helper overlay asso-ciated with each node is filled randomly using Random Peer Sampling. The number of nodes in the helper overlay is truncated to lh. The documents that each node is editing is also selected randomly. In the initial stage as we don’t know the collaborators, the helper overlay is used to fill all the document views associated with each node. The node which is the farthest in the helper overlay forms the first entry of the finger list. Based on how far this node is the other entries are also filled.

Figure 6 shows how our system progresses after initialization. All the sub overlays contained in the system follow the same generic procedure. In each cycle all the suboverlays get updated so as to reach an optimal stage. Procedure U pdate Overlay(O, dist, c, s, so, base) is used for updating the overlay networks. Six arguments are being passed to this function. Here O represents the overlay

1: System initialization

2: n.H ← random R.P.S of size lh

3: for all d ∈ n.D : n.view(d) ← n.H

4: U pdate Overlay(F [0], ∆, n.H, 1, −1, 1)

5: for i from 1 to log F [0]

6: U pdate Overlay(F [i], ∆, n.H, 1, 1, ∆(F [0], n)/2i) Fig. 5. Initialization

being updated. dist represents the function used for calculating the similarity between the nodes. s is the size of the resulting overlay. so is the sort order. This sorts the resulting array in ascending or descending order on the basis of similarity metric. base is used to get the nodes which are similar but non-identical. An important argument that is being passed to this function is c, which represents the candidate list that is used to update the overlay. This contains a list of nodes that can be used to update a given overlay. For generality we are truncating the candidate list to the desired size(s) of the resulting overlay. A good set of candidates can significantly affect the convergence speed of our system.

In each round, node n randomly selects a node p from its helper overlay and gets the neighbourhood information of p. p.H along with one randomly selected node in the system is used as the candidate list for the updation of helper overlay associated with node n. A random entry is added with the hope that the system converges faster. Measures are taken to remove n from the candidate list associated with updation of overlays associated with node n. The randomly filled helper overlay is modified as the simulation progresses so as to fill it with nodes similar to themselves but non-identical. Like wise the finger list is also updated with another set of carefully selected candidate list. Fingers helps in providing links to non-similar nodes or in other words they provide long distance routing links to nodes further away. They also helps in preventing disjoint clusters. The finger lists are used in cases where a node needs to find collaborators for a newly added document. A node can look in its finger list in order to find someone editing the newly added document or to find some one who might be editing a document similar to the newly added document. Individual document views are also updated in each round. If the current document view already has a node with that document then that node’s document view is used to update the document overlay or else a randomly selected node is made use of.

After a certain number of rounds the system kind of stabilizes i.e. all the document views gets filled. Procedure δ(d, n, u) helps when a new document gets added to a node or when a new node is added to the system. When a new document d gets added to a node n what we aim to do is to find the collaborators in a fast manner. Procedure δ(d, n, u) checks whether the document d which is newly added to node n is present in node u. If it is present then n uses the document view of u to find the collaborators for d. We can use U pdate Overlay(n.view(d), δ(d, −, −), n.F ∪ n.H, l, 1, 0) for this purpose. So if

1: In round(r) do

2: p ← random node from n.H

3: ch ← p.H∪ {one random R.P.S} \ {n}

4: U pdate Overlay(n.H, ∆, ch, lh, −1, 1)

5: for i from 1 to lf

6: cf ← F [i].F ∪ F [i].H∪ {one random R.P.S} \ {n}

7: U pdate Overlay(F [i], ∆, cf , 1, 1, 1)

8: for all d from n.D

9: if ∃p ∈ n.view(d) so that d ∈ p.D

10: select p ; c ← p.view(d)

11: else select a random node p from n.view(d)

12: c ← p.H ∪ p.F ∪ {one random R.P.S} \ {n} 13: U pdate Overlay(n.view(d), ∆, c, l, −1, 0) 14: Procedure ∆(n, u) 15: S1← n.D \ u.D 16: if S1=∅ then S1← n.id 17: S2← u.D \ n.D 18: if S2=∅ then S2← u.id 19: S3← S1× S2 20: m ← min(|x − y|)∀(x, y) ∈ S3 21: return m 22: Procedure δ(d, n, u) 23: if d ∈ n.D ∩ q.D 24: return 0 25: else 26: return ∆(n, u)

27: Procedure U pdate Overlay(O, dist, c, s, so, base)

28: O ← argmaxs

p∈c(dist(n, p) − base) ∗ so

Fig. 6. Filament

none of the nodes in the candidate list contains document d, then node n makes use of the similarity metric ∆ to find its collaborators.

4

Evaluation

4.1 Experimental Setting and Metrics

Unless otherwise indicated, the default network size is taken as 212. We assume

that the system has converged when all the document sub-overlays are filled i.e. all the nodes have successfully found collaborators for the documents they are currently editing. For generality, the value of l (document view) and lh (size of the help overlay) is taken as 10 in all the experiments. For all the network sizes, we assume that a total of 10 documents are there in the system. It is also assumed that each document is being edited by 10% of the network size number of nodes. The results obtained during the evaluation are shown in this section.

We assess the performance of our approach using two metrics:

– Document latency - captures the number of rounds it takes for the system to find l collaborators for a newly added document.

– Load associated with each node - measures the load associated with each node based on the communication cost associated with them. This is directly related to the number of times a node is accessed during simulation.

4.2 Baselines

The performance of our approach is compared against a chord-based DHT ap-proach. The main reason for this is that a DHT is commonly used in similar applications and they perform really well providing deterministic guaranties. The document id is hashed and based on the hash value obtained, a node gets selected. The collaborators list for that document gets stored in the selected node. So in order to find the collaborators for a document all we have to do is hash the document id and send a message to the corresponding node for the collaborators list. The main delay here is to find a node given its node id. Chord based topology helps in this by providing faster routing. Node ids are ordered in an ID space modulo 2t. We say that id a follows id b in the ring, if (a−b+2t) mod 2t< 2t−1; otherwise a preceeds b. Given an id a, its successor is defined as the nearest node whose id is equal to a or follows a in the ring. The notion of prede-cessor is defined in a symmetric way. Each node maintains two sets of neighbors, called leaves and fingers. Leaves of node n are its lh nearest successors. For each node n, its jthfinger is defined as successor(n + 2j), with j ∈ [0, t − 1]. Routing

in Chord works by forwarding messages in the ring following the successor di-rection, when receiving a message targeted at node k, node n forwards it to its furthest leaf or finger that preceeds successor(k). Fingers helps in reducing the number of nodes traversed to reach the destination node.

4.3 Results

All the results (Figs. 7-12 and Tables. 2-3) are computed with Peersim [21] and are averaged over 10 experiments. The source code is made available in http://armi.in/resmi/ce1.zip. The comparison to the baseline is done with the help of a base case setting. When shown, intervals of confidence are computed at a 95% confidence level using a student t-distribution.

Figure. 7 shows the convergence time of Filament with varying network sizes. As the network size increases the time taken for the system to converge also in-creases. We assume that the system is converged when all the document overlays are completely filled. From the graph it is clear that Filament works well for very large network sizes. Figure. 8 shows the cumulative frequency distribution of converged nodes for Filament in the base case. A small number of converged nodes causes a chain effect causing a larger number of nodes to converge in the following rounds. Thus once the nodes start converging, the system progresses towards convergence in a faster manner. Figure. 9 shows the number of nodes in

0 5 10 15 20 210 211 212 213 214 215

Convergence time (#Rounds)

Network size

Fig. 7. Convergence time of Filament for varying network sizes

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 CFD of converged nodes(in %) Round

Fig. 8. Cumulative frequency distribu-tion of converged nodes for Filament in the base case

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

#nodes in the document view of n

Round

Fig. 9. No: of nodes in the document view of n for Filament in the base case

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 210 211 212 213 214 215 Document latency Network size Filament DHT

Fig. 10. Filament vs DHT based on document latency

the document view of n when a new document is added to n and it tries to find l collaborators.

Figure. 10 shows how our approach fares compared to a chord based DHT approach. Our approach has lower document latency compared to a DHT. The document latency varies from 4.8 to 8.1 as the network size grows from 210 to 215 for Filament while it varies from 5.2 to 11.1 for DHT. DHT provides an additional level of indirection. The document id is used for hashing and the collaborator list associated with a document might be stored in a node which is not editing that document at all. More over DHT is not exactly an optimal solution in this scenario as the number of documents being edited is significantly smaller compared to the number of nodes in the system. The latency in the case of DHT is mainly associated with routing to the node with the collaborators list. Compared to this Filament shows a better performance with the help of document sub-overlays and finger list.

The Table. 3 shows the maximum, minimum and mean load associated with a node for both Filament and DHT when a new document is added to the system. When a new document is added to a node, the node tries to find l collaborators for that document. Inorder to do that, it has to exchange messages with other

Table 2. Filament vs DHT based on document latency

Network Size Filament DHT

210 4.8(±1.3) 5.2(±1.4) 211 5.6( ±1.2) 6.7(±1.3) 212 6.2(±1.1) 8.1(±1.2) 213 6.9( ±1.1) 9.3(±1.1) 214 7.6(±1.1) 10.2(±1.1) 215 8.1(±0.9) 11.1(±0.9)

Table 3. Load associated with nodes for Filament and DHT (in bytes)

Load Filament DHT Minimum 8 8 Mean 64 96 Maximum 176 880 0 5 10 15 20 210 211 212 213 214 215

Document Latency (#Rounds)

Network size D = 1 D = 5 D = 10 D = 20

Fig. 11. Effect of varying the number of documents for Filament

0 5 10 15 20 210 211 212 213 214 215

Document Latency (#Rounds)

Network size r = 2 % r = 5 % r = 10 % r = 20 %

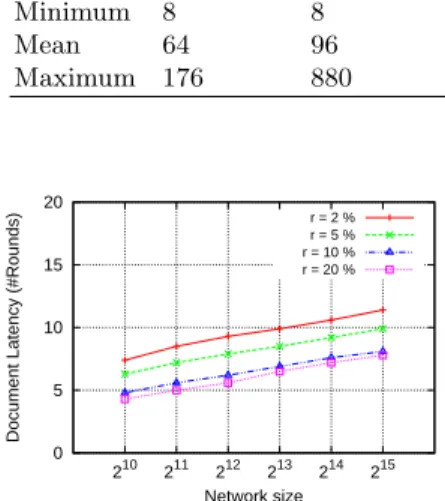

Fig. 12. Effect of varying the number of nodes editing a document

nodes. Here we assume that a single message has a size of 8 bytes which is the size of node id. The results show the case when a document d is added to a node that doesn’t contain it and 10 experiments are conducted with the same document id. The cumulative result is shown in the table. In the case of DHT the same node is getting accessed multiple times for the collaborators list of d while in the case of Filament the load is divided as all the nodes editing the document will have collaborators list in them. The average load associated with a node is slightly lesser for Filament. But the maximum load of DHT is very high which can lead to bottle necks in the network.

Effects of variants The Figure 11 shows the effect of varying the number of documents in the system. As we can see increasing the number of documents in the system helps it to converge in a faster manner. This is to be expected as the number of sub-overlays associated with each node increases with the increased number of documents. Making use of these additional sub-overlays, a node can optimize its neighbourhood and finger list. But there is also a disadvantage asso-ciated with this; the amount of overlays to be managed in each round increases leading to an increased load for the nodes.

Figure 12 shows the effect of varying the number of nodes editing a document or in other words the size of collaborators in the system. From the graph it is clear that as the number of nodes editing a given document increases it helps

the system to converge faster. This is mainly because we can easily get the information about the collaborators if more and more nodes are editing the same document.

5

Related Work

Researchers have been looking into peer-to-peer collaborative editing platforms [9, 13, 17, 18, 22, 30] for some time. Most of these approaches in decentralized peer-to-peer collaborative editing assume that all users in a system participate in the same edition which may not be the case in most systems. Search techniques to find collaborators in peer-to-peer system has been extensively researched in the past in both unstructured [11, 12, 19, 23] and structured overlays, in par-ticular in the context of Distributed Hash Tables DHTs [25–27, 31]. Most of the works assume a static network which is a rather strong assumption considering the rather dynamic nature of CE systems. DHTs typically provide determin-istic guaranties, but usually assume that the number of items to be stored is much higher than the number of storage nodes available. Furthermore, these systems use consistent hashing techniques in which a node’s role in the system is independent of this node’s particular interests. Unstructured approaches have probabilistic recall rate. Flooding or exhaustive multicast strategy is used in these systems but they are very costly. Works by Pascal et.al. [9, 22, 30] studies structured collaborative editing platforms and routing techniques.

Our problem is very similar to peer clustering. Publish/subscribe systems are mainly used for distributed and selective content delivery. Content based pub/sub systems and routing is an actively studied [5–8,29]. In pub/sub systems subscribers express their interest by registering subscriptions and they be notified of any events(issued by publishers) which match their subscription. The work by Voulgaris et al. [29], proposes Sub-2-Sub, a solution to implement a content based pub/sub system. Subscribers sharing the same interests are clustered to form a ring-shaped overlay network which is continuously updated continuously by analysing the interest of users. The work mainly focuses on interest clustering and the content dissemination. The TERA system [5] was designed with a general overlay (similar to Filament’s helper overlay) that is used to keep track of given topic ids used to maintain topic-overlays and perform topic based routing. The problem of building overlays for users with possibly intersecting interests was formalized in works like [8] and then used to define the Spidercast system [7]. In this case a single overlay is built but the connectivity between users interested in the same topic is guaranteed. Starting from this initial trend several other papers [6] have appeared in this same line of research. Many of these search and routing techniques can be adapted for CE systems but is not optimal because of the structural difference between CE and pub/sub systems.

6

Conclusion and Future Work

In this paper, we presented Filament, a novel cohort-construction approach that allows users editing the same documents to rapidly find each other. Filament utilises the semantic relations between peers to construct a set of self-organizing overlays which can be used to route search requests. The resulting protocol is efficient, scalable, and provides beneficial load-balancing properties over the involved peers. Simulation results show that in a network of 212nodes, Filament

is able to reduce the document latency by around 20% compared to a Chord-based DHT approach.

One aspect we would like to explore in future is to deploy Filament in a real system and see how it fares. A thorough analytical study of the behaviour of our approach is also intended.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the DeSceNt project granted by the Labex CominLabs excellence laboratory of the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR- 10-LABX-07-01).

References

1. diaspora, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diaspora_(software) 2. Etherpad, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etherpad

3. Google docs, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Docs,_Sheets,_and_

Slides

4. owncloud, https://owncloud.org/

5. Baldoni, R., Beraldi, R., Quema, V., Querzoni, L., Tucci-Piergiovanni, S.: Tera: Topic-based event routing for peer-to-peer architectures. In: Proceedings of the 2007 Inaugural International Conference on Distributed Event-based Systems. pp. 2–13. DEBS ’07 (2007)

6. Chen, C., Tock, Y.: Design of routing protocols and overlay topologies for topic-based publish/subscribe on small-world networks. In: Proceedings of the Industrial Track of the 16th International Middleware Conference. Middleware Industry ’15 (2015)

7. Chockler, G., Melamed, R., Tock, Y., Vitenberg, R.: Spidercast: A scalable interest-aware overlay for topic-based pub/sub communication. In: Proceedings of the 2007 Inaugural International Conference on Distributed Event-based Systems. pp. 14– 25. DEBS ’07 (2007)

8. Chockler, G.V., Melamed, R., Tock, Y., Vitenberg, R.: Constructing scalable over-lays for pub-sub with many topics. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing, PODC 2007, Portland, Oregon, USA, August 12-15, 2007. pp. 109–118 (2007)

9. Davoust, A., Skaf-Molli, H., Molli, P., Esfandiari, B., Aslan, K.: Distributed wikis: a survey. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 27(11), 2751– 2777 (2015)

10. DeCandia, G., Hastorun, D., Jampani, M., Kakulapati, G., Lakshman, A., Pilchin, A., Sivasubramanian, S., Vosshall, P., Vogels, W.: Dynamo: amazon’s highly avail-able key-value store. In: SOSP’07

11. Dorrigiv, R., Lopez-Ortiz, A., Pra lat, P.: Search algorithms for unstructured peer-to-peer networks. In: Local Computer Networks, 2007. LCN 2007. 32nd IEEE Con-ference on. pp. 343–352. IEEE (2007)

12. Gkantsidis, C., Mihail, M., Saberi, A.: Random walks in peer-to-peer networks: Algorithms and evaluation. Perform. Eval. 63(3), 241–263 (Mar 2006)

13. Gupta, A., Sahin, O.D., Agrawal, D., Abbadi, A.E.: Meghdoot: content-based pub-lish/subscribe over p2p networks. In: Middleware’04

14. Jelasity, M., Montresor, A., Babaoglu, O.: T-man: Gossip-based fast overlay topol-ogy construction. Comput. Netw. 53(13), 2321–2339 (Aug 2009)

15. Jelasity, M., Voulgaris, S., Guerraoui, R., Kermarrec, A.M., van Steen, M.: Gossip-based peer sampling. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 25 (August 2007), http://doi. acm.org/10.1145/1275517.1275520

16. Karger, D.R., Ruhl, M.: Simple efficient load balancing algorithms for peer-to-peer systems. In: Proceedings of the sixteenth annual ACM symposium on Parallelism in algorithms and architectures. pp. 36–43. ACM (2004)

17. Kermarrec, A.M., Triantafillou, P.: Xl peer-to-peer pub/sub systems. ACM Com-puting Surveys (CSUR) 46(2) (2013)

18. Lakshman, A., Malik, P.: Cassandra: a decentralized structured storage system. SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 44(2) (2010)

19. Lv, Q., Cao, P., Cohen, E., Li, K., Shenker, S.: Search and replication in unstruc-tured peer-to-peer networks. In: Proceedings of the 16th international conference on Supercomputing. pp. 84–95. ACM (2002)

20. Montresor, A., Jelasity, M., Babaoglu, O.: Chord on demand. In: P2P 2005 21. Montresor, A., Jelasity, M.: Peersim: A scalable p2p simulator. In: P2P 2009 22. Oster, G., Mond´ejar, R., Molli, P., Dumitriu, S.: Building a collaborative

peer-to-peer wiki system on a structured overlay. Computer Networks 54(12), 1939–1952 (2010)

23. Otto, F., Ouyang, S.: Improving search in unstructured p2p systems: Intelligent walks (i-walks). In: Proceedings of the 7thInternational Conference on Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning (IDEAL’06). Lecture Notes in Com-puter Science, vol. 4224, pp. 1312–1319. Springer (Sep 2006)

24. Rao, A., Lakshminarayanan, K., Surana, S., Karp, R., Stoica, I.: Load balancing in structured p2p systems. In: Peer-to-Peer Systems II, pp. 68–79. Springer (2003) 25. Ratnasamy, S., Francis, P., Handley, M., Karp, R., Shenker, S.: A scalable content-addressable network. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 31(4), 161–172 (2001) 26. Rowstron, A.I.T., Druschel, P.: Pastry: Scalable, decentralized object location, and

routing for large-scale peer-to-peer systems. In: Middleware. pp. 329–350 (2001) 27. Stoica, I., Morris, R., Karger, D., Kaashoek, M.F., Balakrishnan, H.: Chord: A

scalable peer-to-peer lookup service for internet applications. In: SIGCOMM ’01 28. Voulgaris, S., Steen, M.v.: Epidemic-style management of semantic overlays for

content-based searching. In: Euro-Par’05

29. Voulgaris, S., Rivire, E., Kermarrec, A.M., Steen, M.V.: Sub-2-sub: Self-organizing content-based publish subscribe for dynamic large scale collaborative networks. In: In IPTPS06: the fifth International Workshop on Peer-to-Peer Systems (2006) 30. Weiss, S., Urso, P., Molli, P.: Logoot-undo: Distributed collaborative editing system

on P2P networks. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 21(8), 1162–1174 (2010) 31. Zhao, B., Kubiatowicz, J., Joseph, A.: Tapestry: An infrastructure for fault-tolerant