Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

31

415

dewe

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

Current

Accounts

in

the

Long

and

Short

Run

Aart

Kraay

Jaume

Ventura

Working

Paper

02-21

June

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

atMASSACHUSETTSINSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY

JUN

1

3

2002

'

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Current

Accounts

in

the

Long

and

Short

Run

Aart

Kraay

Jaume

Ventura

Working

Paper

02-21

June

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

atRevised

Draft

Current

Accounts

in

the

Long and

Short

Run

Aart

Kraay*

The

World

Bank

Jaume

Ventura

MIT,

CEPR

and

NBER

June 2002

Abstract:

Faced

withincome

fluctuations, countriessmooth

theirconsumption by

raising savings

when

income

is high,and

viceversa.How

much

ofthese savingsdo

countries invest at

home

and abroad?

In otherwords,what

arethe effects offluctuations in savings

on domestic

investmentand

the currentaccount?

Inthe longrun,

we

find thatcountries investthe marginal unit ofsavings indomestic

and

foreignassets inthe

same

proportionsas

intheirinitial portfolio,so

thatthelatteris remarkablystable. Inthe short run,

we

find thatcountries investthe marginal unitofsavings mostlyinforeign assets,

and

only graduallydo

they rebalancetheir portfolioback

to itsoriginalcomposition. This

means

that countries not onlytry tosmooth

consumption, butalsodomestic

investment.To

achievethis, theyuse

foreignassetsas

a buffer stock.*Thispaperhasbeenpreparedforthe2002

NBER

MacroeconomicsAnnual.We

aregrateful toourdiscussantsFabrizioPerriandEricvanWincoopaswell astothe participantsfor theirusefulcomments.

Theopinionsexpressed hereare the authors',and do notnecessarilyreflectthoseoftheWorldBank,its

Countries are subject to transitory

income

shocks such

aschanges

intheterms

oftrade, fluctuations in production, policyreforms, natural disasters,

and

many

others.There

isample

evidence

thatcountriesuse

theirassets to bufferorsmooth

the effects oftheseshocks

on consumption,

raising savingswhen

income

is highand

viceversa.1The

main

goal ofthispaper

is toimprove

our understanding ofthecombination ofassetsthatcountries

use

forthis purpose. In particular,we

ask:how

do

countriesallocatethe marginal unitof savings

between

domestic

and

foreign assets? Or,equivalently,

what

are the effects of fluctuations in savingson domestic

investmentand

thecurrent

account?

2The

traditionalview

is thatcountries invest the marginal unitofsavings inforeign assets. Underlying this

view

are theassumptions

that investment risk isweak

and

diminishing returns are strong.The

firstassumption ensures

thatcountries investtheirsavings only in

those

assetsthat offerthe highestexpected

return.The second

assumption

implies that investingany

fraction ofthe marginal unit ofsavings indomestic

capitalwould

loweritsexpected

returnbelow

that offoreign assets.Hence

the marginal unit ofsavings is invested in foreign assets,justifying thetraditional rule thatfluctuations in savings leadtofluctuations in the currentaccount

of roughlythesame

magnitude.While

theoreticallycoherent, this rulehas

been

consistently rejectedby

the data.The

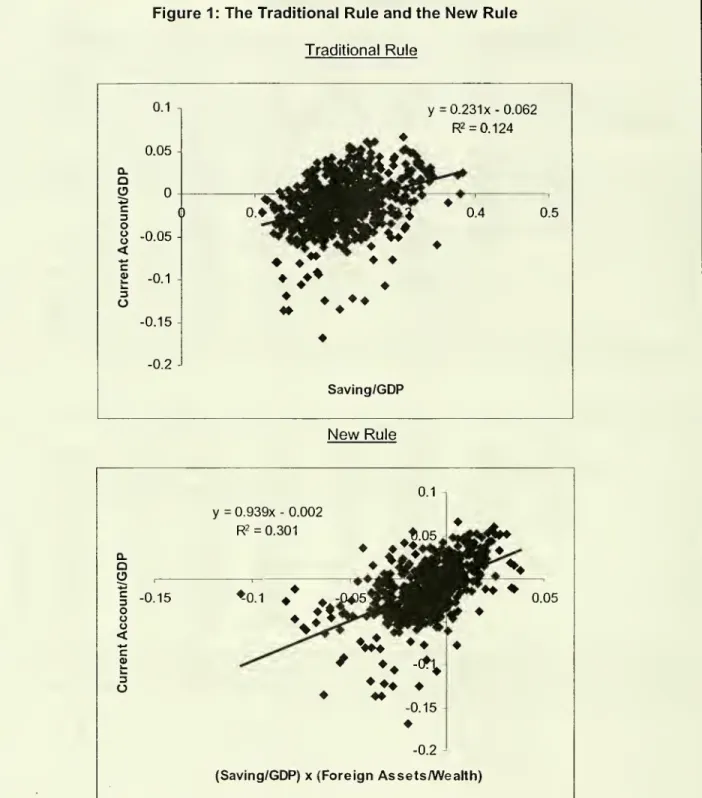

top panel of Figure 1shows

pooledannual

observations ofthe currentaccount

and

savingsfor21OECD

countriesover

thepast30

years.A

regression ofthecurrent

account

on

savings delivers a slope coefficientthat is positive butmuch

lowerthan one. This is nothing butthe

famous

resultofFeldsteinand

Horioka [1980] that fluctuations in savings leadto parallelfluctuations in investment,with onlyminor

effectson

the currentaccount.1

Forevidenceonconsumption-smoothing,see Deaton[1991]whowrites that"consumptionislessvolatile

than income,itfluctuates lessaboutitstrend,theamplitudeofitsbusinesscycle variationisless,andthe

varianceofitsgrowthrate islessthanthevarianceofthegrowthrateofincome"p.133-34.

2

Why

docountriesuseassetstosmooth consumption ratherthan simplybuyinsuranceabroad?Implicitinthisparagraph andbasicallyinallthat followsistheassumptionthatcountriesareunableor unwillingto

selltheiridiosyncraticrisk.Thisassumptionisa centraltenetofthe intertemporalapproachtothe current

In

an

earlierpaper,we

proposed

anew

view

thatcountries invest the marginalunit ofsavings as the

average

one

(Kraayand Ventura

[2000]). Thisiswhat

one

shouldexpect if, in contrasttothetraditionalview, investment riskis strong

and

diminishingreturns are

weak.

The

firstassumption

impliesthat countries are unwilling tochange

the composition oftheir portfolios, unless

shocks

have

large effectson

thedistribution of asset returns.The

second assumption ensures

thatthedistribution ofasset returnsis unaffected by the

way

countries investthe marginal unit ofsavings.Hence,

the marginal unitofsavings isinvested as theaverage

one, leading tothenew

rulethat fluctuations insavings lead tofluctuations inthe currentaccount

thatare equal tosavingstimesthe

share

offoreign assets in thecountryportfolio. Thisrule notonly istheoreticallycoherent, butit also providesasurprisingly

good

description ofthe data.The

bottom

panel of Figure 1shows

that a simple regression ofthe currentaccount

on

the interaction

between

savingsand

the shareofforeign assetsdelivers a slopecoefficientcloseto

one

and

a zero intercept. Moreover, this interactionterm by

itselfexplains

around

thirtypercent oftheobserved

variation in the currentaccount.3Hidden

in thebottom

panel ofFigure 1 there isa vast differencebetween

thepredictive

power

ofthenew

rule inthe longand

the shortrun. Figure2 illustrates thispoint. In thetop panel,

we

have

plottedtheaverage

currentaccount

over a thirty-yearperiod against the

average

ofsavings time theshare

of foreign assets during thesame

period.

The

new

ruleexplains about85

percentofthe long run oraverage

cross-country differences in current accounts. Inthe

bottom

panel,we

have

plotted the(demeaned)

currentaccount

foreach

countryand year

againstthe(demeaned)

interaction ofsavings

and

the initial share offoreign assetsin wealthforthesame

country

and

year.The

new

ruleexplains basicallynone

ofthe year-to-yearwithin-reality.Thequestionofwhythisissoisoneofthemostintriguingpuzzlesininternationalfinance.See

Lewis[1999]forasurveyoftheliteratureonthis topic.

3

Sinceforeignassetsconstituteasmallfractionofobservedcountryportfolios, thisviewimplies that

fluctuationsinsavingsshould mostlyleadtoparallelfluctuationsininvestment,andistherefore consistent withthe Feldstein-Horiokafinding.What wefound mostsurprisingaboutthis viewinourearlierpaperis

thatithassharplydifferentimplicationsforthe currentaccountresponsetoanincreaseinsavingsin

debtorandcreditorcountries.Since debtors bydefinitionhold morethantheirwealth indomesticcapital,

theyinvestat

home

morethantheincreaseinsavings,resultingina currentaccountdeficit. Incontrast, creditorcountries investathome

lessthanthe increaseinsavings,resulting inacurrentaccountsurplus.country differences in current accounts.

The

contrastbetween

thetwo

panels indicatesadiscrepancy

between

the longand

the short run behavior ofthecurrent account.4Isthe short-run relationship

between

savingsand

the currentaccount

just noiseorare there clearpatterns behind this cloud of points?

How

do

we

reconcile the apparentlyhaphazard

behaviorofthe currentaccount

in the shortrun with its neatbehaviorinthe long run?

The

main

contribution ofthis paper,we

think, is to provideclear

answers

to thesequestions.To

do

this, it is useful to startby

pointing outthatthenew

ruleembodies

theview

thatthe currentaccount

primarily reflects portfoliogrowth,i.e.

changes

inthe size ofthecountry portfoliowithout systematicchanges

in itscomposition.

The

empiricalsuccess

ofthenew

rulein thetop panelof Figure2

simplyreflectsthe observationthat thecomposition ofcountryportfolios

has

been

remarkably

stable in the long run. This is

shown

in Figure 3. Ifwe

want

tounderstand

why

thenew

rule

performs so

poorly inthebottom

panelofFigure 2,we

must

explainhow

and

why

in the short run increasesin savings lead mostlyto portfoliorebalancing, i.e. systematic

changes

inthe composition ofthecountry portfolio. Ifin additionwe

want

to reconcile thetwo

panels ofFigure2,we

must go

furtherand

also explainwhy

this short-runportfolio rebalancing is

undone

inthe long run.Our

hypothesis isthatthe pattern of portfolio rebalancing is consistentwiththeview

thatadjustment

coststo investment are important. Ifthis is the case,an

increasein savingsthat raisesinvestment

reduces

theexpected

return to capitaland

inducescountries to rebalancetheir portfolios

towards

foreign assets.Under

these

conditions,theshort-run current

account

surplus is largerthan theone

predictedby

thenew

rule.Once

savings returns tonormal, investmentdeclines,adjustment

costsdisappear

and

thecountry portfolio returnsgraduallytoits original composition.

Throughout

thisadjustment

process, the currentaccount

surplus is smaller than theone

predicted by4

We

alsonotedthisdiscrepancyinourearlierpaper, althoughitwasmuchlesspronouncedinthesmallersampleof13countriesand 23years(1973-1995)that

we

usedthere.Here,we

have been abletoextend oursampleto21 countriesand upto32years per country (1966-1997).Allthe resultsobtained inthethe

new

rule. In the long run, theshock does

not affectthecomposition ofthecountryportfolio

and

thenew

rule applies.With

thistheoretical pictureat hand,we

go

back

tothedatato searchforpatternsin thediscrepancies

between

theobserved

currentaccount

and what

thenew

rule

would

predict.When

we

do

this, the picturethatcomes

outfrom

thedata turns outto

be

clearand unambiguous: on

impact, countries rebalancetheir portfoliostowards

foreign assets

and

thenew

rulesystematically under-predicts the short-run effects ofincreases insavings

on

the currentaccount. Intheyearsthat follow, countriesrebalancetheirportfolios

back towards

their original composition. During this period,the

new

rulesystematically over-predictsthe currentaccount.We

findthat thewhole

adjustment

process

lastsabout

fiveyears. Overall, theevidence isconsistent with theview

thatadjustment coststo investment are important and, to avoid payingthem,

countries

use

foreign assets as a bufferstock tosmooth

fluctuations in investment.The

theory presented herecan

also reconciletwo

apparentlycontradictoryobservations

about

the relationshipbetween

the currentaccount

and

investment.On

theone

hand, the long run or cross-sectional correlationbetween

investmentand

thecurrent

account

isweak

(Penatiand Dooley

[1984],Tesar

[1991]).On

the otherhand,theshort run or time-series correlation

between

investmentand

the currentaccount

isconsistently negative (Glick

and Rogoff

[1995]).The

theory presented here predictsthat inthelong run, portfolio rebalancing issmall

and

the correlationbetween

thecurrent

account

and

investment shouldbe

positive in creditorcountriesand

negative indebtor ones.

We

show

thatthedata is consistent withthis predictionand

thattheweak

cross-sectional correlation isthe resultof pooling datafrom debtorand

creditorcountries.

The

theoryalso predicts thatin theshort run portfolio rebalancing isimportant

and

this introduces asource

ofnegative correlationbetween

thecurrentaccount

and

investment. This istrue in allcountries, regardlessofwhether

they are debtors orcreditors.We

present a simpledecomposition

ofthe cross-sectionaland

time-series correlations

between

the currentaccount

and

investmentthat illustrates thisThe

paper

isorganizedas

follows: Section I presents a stylizedmodel

thatencapsulatesthe

main elements

ofour portfolio-basedtheoryofthe currentaccount. Section IIuses

themodel

to studyhow

countries reacttoincome

shocks. Section IIIexamines

the empiricalevidence

and

interprets itfrom

thevantage

point ofthe theory.Section IVinvestigatesthe relationship

between

investmentand

the currentaccount. SectionV

concludes.I.

An

Intertemporal

Model

of

the

Current

Account

In this section,

we

presenta stylizedmodel

ofhow

the currentaccount

responds

totransitoryincome

shocks. Sincewe

stop short ofmodeling

the worldequilibrium

and

focus insteadon

a smallopen economy,

theseshocks

shouldbe

interpreted as country-specific or idiosyncraticrisk. Following thetradition ofthe

intertemporal approach,

we

simplyassume

that countries are unableor unwilling tosellthis riskin international markets. In particular,

we

adopt

the starkestform

ofthisview

by

assuming

that the onlyassetthat is traded internationallyis a non-contingent bond. 5The

model

captureswhat

we

think are the essentialelements

of aportfolio-based

theoryofthe current account. This theory is builtaround

theconcept

ofcountryportfolio

and

a simpledecomposition

ofthe currentaccount

that relieson

thisconcept.By

the country portfolio,we

referto thesum

ofall productive assets located within the country plus its netforeign asset position.The

latterconsist of thesum

ofall claimson

domestic

assets heldby

foreignersminus

thesum

of all claimson

foreign assets heldby domestic

residents. In our simple model, the only productive asset located within the country isthestock of capital,and

the net foreign asset position is simplythestockof5

TheintertemporalapproachwasdevelopedbySachs [1981, 1982],Obstfeld [1982],Dornbusch [1983],

Svensson andRazin [1983],Persson and Svensson[1985],andMatsuyama[1987],amongothers.

non-contingent

bonds

owned

by

the country.By

thecomposition ofthe countryportfolio,

we

refer totheshare

ofthe net foreign asset position in it.To

interprettheevolution ofthe current

account

it is usefulto breakitdown

intotwo

components

orpieces:

changes

in the sizeofthecountry portfolio,which

we

callportfolio growth;and

changes

inthecomposition ofthecountry portfolio, orportfoliorebalancing.6We

studya small country populated by acontinuum

ofidenticalconsumers.

There

is a singlegood

thatcan be

used

forconsumption

and

investment.Consumers

have access

totwo

investmentopportunities:foreign loansand

domestic

capital.The

instantaneous interest rate

on

foreign loansis p.To

produce

one

unitofcapitalone

unit ofthe singlegood

is required. Sincecapital is reversibleand

does

not depreciate, itsprice isequalto

one

and

its return isequal tothe flow ofproductionminus

operatingcosts.

The

flowof productiongenerated

byone

unit of capital is7idt+0-dco;

where

n and

a

are non-negative constants;and

co is aWiener

processes, i.e. itschanges

arenormally distributedwith E[dco]=0

and

E[dco2]=dt.That

is, theflow ofproduction isnormally distributedwith instantaneous

mean

n and

instantaneous variance o.The

operating costs, a, are

assumed

tobe

proportional totheaggregate

investment rate:1 rik

(1)

«=*-—

(teo)k dt

where

k istheaggregate

stock ofcapital at the beginningofthe period. Sincecapitaldoes

notdepreciate, this is also thestockofcapitalthatwas

used

in production in the previousperiod.Note

thatwe

aretreating the relationshipbetween

operating costsand

investment asa congestion effectornegative externality.

One

set ofassumptions

thatjustifiesthis relationship

would be

thatinvestment requiresa public input thatcosts A.perunit of investment

and

thegovernment

financesthis input by raising a taxa

on

capital.

There

mightbe

alternativeand more

compelling sets ofassumptions

that6

Implicitinthis decompositionistheassumptionthatassetpricerevaluations are small. Thismightbe a

deliverthis relationship.

The

reason

we

adopt

ithere is simplybecause

it provides atractable

and

effectiveway

tocapture the notion ofadjustment

coststo investment.7The

representativeconsumer

valuesconsumption

sequences

withthese preferences:(2)

EJlnce"

5'

dt (6>0)

Given

ourassumptions about

theflow ofproductionand

theoperating costs,the returnto capitalis

(Tt-a)dt

+

adco; and

the representativeconsumer's budget

constraint

can be

writtenas

follows:(3)

da = [((n-a)-(1-x)

+

px)a-c]-dt

+

(1-x)-a-a-dco

where

c, aand

xdenote consumption,

wealthand

theshare

offoreign loans in theportfolioofthe representative

consumer.

The

budget

constraintillustratesthe standardrisk-returntrade-offunderlying investmentdecisions.

Each

extra unit ofwealth investedin

domestic

capital ratherthan foreign loans increases theexpected

return towealthby

n-a, atthe cost ofraising the varianceofthis return by

a

2. Finally,we

assume

that it isnot possibleto short-sell thecapital stock, i.e. x<1

.

Solving the representative

consumer

problem,we

findthe optimalconsumption

and

portfoliodecisions:8(4) c

=

5•a7

Theq-theory postulates thatinvestmentraisesthe price ofinvestmentgoodsrelative toconsumption

goods, leavingthe productivityof capitalconstant.

We

instead postulate thatinvestment lowerstheproductivityof capital, leaving therelativepriceofinvestmentand consumption goodsconstant. Itis likely

thatinrealeconomies, bothsortsofadjustmentcoststoinvestment areimportant. SeeLucas[1967]foran

earlymodelthatconsiders both typesofadjustmentcosts;andCaballero [1997]andDixitandPyndick

[1994]fortwoexcellent expositions ofexistingmodelsofadjustment costsofinvestment.

(5) x

= 1-max<{

r~^'°

When

decidingtheirconsumption,consumers behave

as

inthepermanent-income

theory ofFriedman.

Equation (4)shows

thatconsumption

is a fixedfraction ofwealth

and

isindependent

oftheexpected

returnand

volatilityofavailable assets.When

deciding theirportfolio,consumers behave

as

inthemean-variance

theory ofMarkowitz

and

Tobin. Equation (5)shows

thattheshares

ofeach

asset in the portfoliodepend

onlyon

themean

and

variance ofthedifferent assetsand

noton

thelevel of wealth.The

kink in thedemand

forforeign assets isthe result ofthe short-sale constrainton domestic

capital, i.e. x<1.In equilibrium,the

demand

and

supply ofcapitalmust be

equaland

this impliesthat:

(6)

(1-x)a

=

k+

dk

The

lefthand

side of Equation (6) isthedemand

for capital. Sincewe

have

assumed

that onlydomestic

consumers

holddomestic

capital, thisdemand

isequal to theshare of theirwealth thattheseconsumers

want

to hold indomestic

capital, timeswealth.

The

righthand

side of Equation (6) isthe supplyof capital,and

consists ofthecapitalstock atthe beginning ofthe period plus the investment

made

during the period.This

completes

the description ofthe model.There

aretwo

state variables: kand

a;and

one

shock: dco.The

"new

rule"model

ofour previouspaper

obtains as thelimiting

case

inwhich

X—

>0. Inthis case,there areno

adjustment costs to investmentand

the only state variable isthe levelofwealth.Assume

that7i>p+A.(p-5). Thisparameter

restrictionensures

thattheeconomy

is productiveenough

so

thattheselling constraint

on

capital isnever

binding.Then,

it is straightforwardtouse

Equations (1)-(6) toobtainthe

dynamics

forthecapital stockand

wealth:9(7) (8)

dk

kda

a=x-

1 -2 k^ji-p-a

•—

ay

•dta

T

2 a+

p-8

dt+

—

-adco

aEquations

(7)-(8)provide the lawof motion ofthesystem from

any

given initialcondition

and sequence

of shocks.Our

next goal is touse

thisdynamical

system

tostudy

how

thecurrentaccount

responds

toincome

shocks.II.

Portfolio

Growth

and

Portfolio

Rebalancing

To

illustratethe model's implications,we

analyzethe behaviorofsavings,investment

and

the currentaccount

after atransitoryincome

shock.To

do

this, it isuseful firstto establish

some

notation. LetS

and

CA

be

savingsand

the current1

da

1 dfx-a)account

bothas

ashare

ofwealth, i.e.S=

and

CA

=

. Itfollowsthat,a

dt a dtalong

any

particularsample

paththatwe

consider, the currentaccount

can be

writtenas follows:

dx

(9)

CA

=

x-S

+

—

dt

Equation (9)

shows

that it is possibleto interpretthecurrentaccount

as

thesum

of

two

terms.The

firstone

measures

thechange

inthe stockofforeign assetsthatToderiveEquations(7)-(8),rememberthatinthelimitofcontinuous timedkdt=0.

would

keep

constantthecompositionofthe countryportfolioand

this iswhat

we

referto

as

portfoliogrowth.The

second term

measures

thechange

in thecompositionofthecountry portfolio

and

this iswhat

we

refer toas

portfoliorebalancing.To

develop

intuitionsabout

the interplaybetween

thesetwo

components

ofthecurrent account,

we

present next a series ofexamples.

In all ofthem,

we

assume

thefollowing

sample

pathforthe production shock:(10)

^

v

' dt

tel-co,^)

e-o

-1 tefTpT;,) (e>0)te[T

2,oo)That

is, the countryexperiences asequence

ofunexpected

productionshocks

equalto

edt

times thecapital stockfor a finite periodand

zero afterwards.We

refer tothe period [TLT2) asthe

shock

periodand

to (-^.T^and

[T2 ,°°)as

the pre-and

post-shock

periods, respectively.Figure

4

shows

the behavior oftheforeign asset position alongthissample

path.

Regardless

oftheinitial condition, duringthepre-shock period theshare

offoreign assets

converges towards

x*=

1+

1 \ 1 f i A

2-X

\{2-X

X

1 (n-

p)-

p+

5+

v7

K .The

a

simulation behind Figure 4

assumes

that thisvaluehas

been

reached by

t=0. Duringthe

shock

periodthe shareofforeign assets increases steadily, albeit at adecliningrate.

The

magnitude

ofthis increasedepends

on

X. High values ofX

implythat theeffects of increased investment

on

operating costs are largeand

provide a stronginducement

for investorsto rebalance theirportfoliostowards

foreign assets. Duringthe post-shock period, investment

and

operating costs decline.As

a result, theshare offoreign assets slowly returns to its pre-shock level.

We

nextstudy the implications ofthis behavior oftheshareofforeign assetsforthe current account.

Consider

firstthecase

inwhich

adjustment coststoinvestment are negligible,i.e.

A—

>0. Figure4

shows

that inthiscase

theshare

offoreign assets is constantdx

throughout.

As

a result, there isno

portfolio rebalancing, i.e.—

=

;and

the currentdt

account

is equalto portfoliogrowth; i.e.CA

=

x•S

.This isthe"new

rule"model

thatwe

analyzed

in our previous paper,and

its implicationsfora creditorand

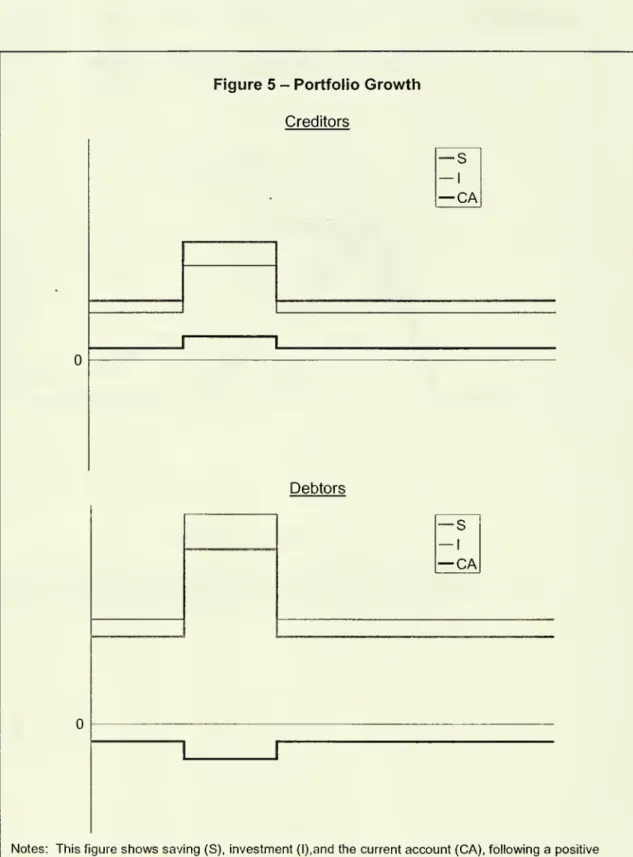

adebtor country are depicted in Figure 5.The

top panelshows

a creditor country, i.e. x*>0, whilethebottom

panelshows

adebtorcountry, i.e. x*<1. Both countries raisetheirsavings during theshock

period as a result ofthe standard"consumption-smoothing"

motive.Both

countries also investthese

marginal savingsindomestic

capitaland

foreign loansinthe

same

proportionsas

theiraverage

portfolio. Since theforeignassetshare

issmall in absolutevalue,

we

findthat in both countriesthe increase in investmentis ofthe

same

orderofmagnitude as

the increase in saving. But itis not exactlythesame,

and

this leads to different currentaccount

responses

in debtorand

creditorcountries.Inthe creditorcountry investment increases

somewhat

less than savingsand

thecurrent

account

registers asurplus. In thedebtor country investment increasessomewhat

more

than savingsand

the currentaccount

registers a deficit.This is themain

resultofour previous paper.Consider

nextthecase

inwhich adjustment

costs toinvestment areno

longernegligible, i.e. X>0. Figure 6

shows

thecase

ofa countrythat is neithera debtor nor acreditor.

By

choosing

thecase

x*=0,we

know

thatintheabsence

ofadjustment

costs,the current

account

would

be

zero before, duringand

aftertheshock. Figure 6shows

the behavior ofsavings, investment

and

the currentaccount

inthis case.The

countryraises its savings during the

shock

periodforthesame

"consumption-smoothing"

motive

as

before. Butadjustment

costsnow

discourage largeswings

in investment,and

this affectshow

these savings aredistributedbetween domestic

capitaland

foreign loans.

During the

shock

period,thecountryuses

most

of its increase in savingstopurchase

foreign loans, while investment increases only gradually.Consumers

rebalancetheirportfolios

towards

foreign assetsbecause

the increase in investmentraisesoperating costs

and

this lowerstheexpected

return todomestic

capital.The

portfolio-rebalancing

component

ofthecurrentaccount

is positiveand,as

a result, thenew

rule under-predicts the currentaccount

surplus in the shortrun. In the post-shockperiodinvestmentfalls slowly, but

remains

higherthannormal

forawhile. Sinceproductivity

has

returnedto its pre-shock level, savings return tonormal

and

thehigher-than-normalinvestment is

now

financedby

a sale of foreign loans.Consumers

rebalancetheir portfolios

back towards

theiroriginal compositionbecause

the declineininvestment lowers operating costs

and

this raisestheexpected

returntodomestic

capital.

The

portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe currentaccount

isthereforenegative and,

as

a result, thenew

ruleover-predictsthecurrentaccount

surplus inthemedium

run.As

time passes, the country portfolio returnsto itsoriginal compositionand

thenew

rule appliesagain inthe long run.This

example

clearlyshows

the roleofforeign loansas

a bufferstock tosmooth

thefluctuations in investment.

Without access

toforeign loans, countrieswould be

forced notonlyto invest all oftheirsavingsat

home

butalso todo

so

contemporaneously.

Access

toforeign loans permits countries atospread

theirdomestic

investment over time and, in thisway,

avoid paying highadjustment

costs.To

do

this, countriestemporarily placetheir savings inforeign loansand

slowly convertthem

intodomestic

investment.It is possibletodesign

more

complicatedexamples

inwhich

the currentaccount

exhibits richer

dynamics.

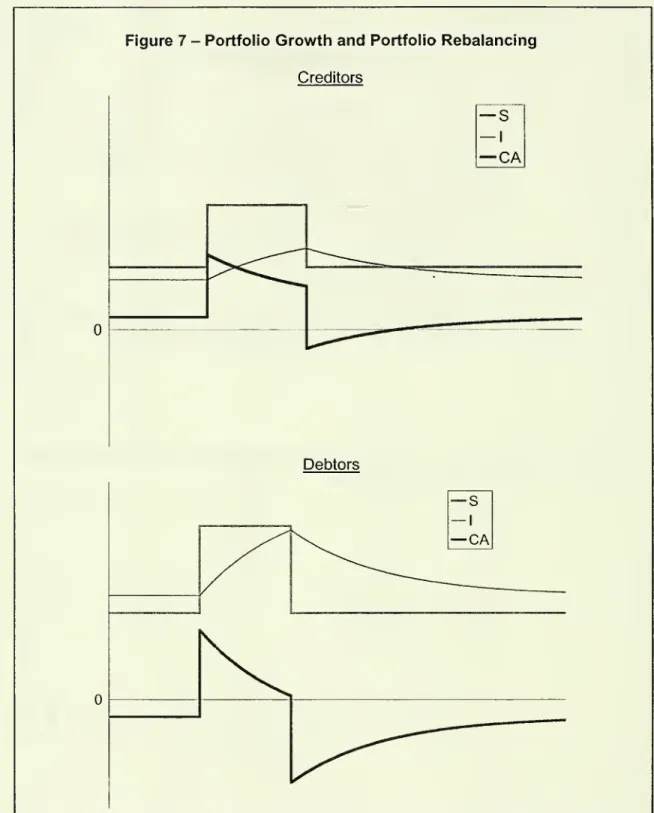

For instance, Figure 7shows

thecase

of positive adjustmentcosts in a creditor

and

a debtorcountry.One

can

interprettheseexamples

as a combinationof portfoliogrowthand

portfolio rebalancing along the lines oftheexplanationsof Figures

5

and

6.The

theorydeveloped

here thereforeequips uswith aclear picture of the factors that

determine

how

the currentaccount

reacts to increasesinsavings.

The

next stepistogo

back

to actualdataand

attemptto interpret itfrom

thevantage

point ofthetheory.III.

The

Process

of

Current

Account

Adjustment

In the introduction,

we

argued

that in the long runmost

ofthe variation incurrent

accounts

inOECD

countries isdue

to portfoliogrowth

effects, while in the shortrun, current

account

fluctuations primarilyreflectchanges

in the composition ofcountryportfolios orportfolio rebalancing.

We

made

this pointbased

on

theobservationthatthesimple interaction ofacountry's foreign asset

share

with its saving,averaged over

thepastthirtyyears,

proved

tobe

a verygood

predictor ofthe country'saverage

current account.

However,

thesame

interaction using annual dataproved

tobe

a verypoor

predictor ofyear-to-yearfluctuations in current accounts. Thiswas

shown

inthetwo

panelsof Figure2.10The

theorypresented

above

has

the potential to explain these observations. Inthe

presence

ofadjustment

costs to investment, thetheorypredicts that in theshort-run countries react totransitory

income

shocks by

raising savingsand

rebalancing theirportfolios

towards

foreign assets. Ifthese costs are sufficientlystrong, thetheorycan

therefore explain

why

the shortrun variation inthe currentaccount

isdominated by

portfolio rebalancing,

and

notportfolio growth.The

theoryalso predicts that in theaftermath ofthe

shock

countries graduallyrebalance theirportfoliosback

to theiroriginal composition. Therefore the theory

can

also explainwhy

thelong-run variationin the current

account

isdominated

by portfoliogrowth,and

not portfolio rebalancing.The

theoryalsohas

very clearpredictionsforthe patterns of portfoliorebalancingthat

we

shouldobserve

in the data.The

new

rule orportfoliogrowth

10

Ofcourse,onecould arguethatthisdiscrepancyinthe"between"and"within"resultsissimplydueto

muchgreatermeasurementerrorinthewithin-country variationincurrent accountsandportfoliogrowth

than inthebetween-countryvariation. Whilemeasurementerroris certainlypresent,

we

clearlydonotthinkitisthewholestory.

One

waytoseethisistonotice that(i) measurementerrorintheRHS

variableinour regressionwillbias theslopecoefficientdownwardby afactorequaltothe signal-to-noiseratio,and

(ii)measurementerrorinboththe

LHS

andRHS

variableswillbiastheR

2coefficientby afactorequaltotheproductofthe signal-to-noiseratios inthetwovariables. Since

we

observeaslopecoefficientofone-halfand an

R

2coefficientthatfallsfrom0.6 inthe"between" regressionto 0.03inthewithin regression, thisimpliesasignalto noiseratioofonly 0.5 intheRHS

variableand0.1 intheLHS

variable. Whilethere areclearlyvariousmeasurementissuesinourdata,we

finditimplausiblethatthe dataisasnoisyasthis calculationwouldsuggest.component

ofthecurrentaccount

under-predictsthe actual currentaccount

during theshock

period as countries rebalancetheir portfoliostowards

foreignassets,whilethenew

rule over-predictsthe currentaccount

aftertheshock

as countries rebalance theirportfolios

back towards

itsoriginal composition. In other words, acontemporaneous

increasein savings should

be

associatedwith a positive portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe current account,while past increases in savingsshouldbe

associated with negative values inthe

same

component.

Moreover, forthenew

ruletoapply inthe long run,these positive

and

negativecomponents

shouldbe

roughlyofthesame

magnitude. In thissection,we

show

that thedata is consistent with thesepredictions.

We

beginby

decomposing

observed

currentaccounts

into portfoliogrowthand

portfolio rebalancing

components.

As

in the theory, let Xctdenote

theshare

offoreignassets in theportfolio ofcountryc atthe beginning of period t,

and

letS

ctand

CAc

tdenote

gross national savingand

the currentaccount balance

as afraction ofGDP

during periodt.

We

measure

the portfolio-growthcomponent

ofthe currentaccount as

PG

ct=

xct•

S

ct, i.e. the net

purchases

offoreign assetsthatwould be observed

duringperiod t if a country

were

to distribute itssavingbetween

domestic

and

foreign assetsin the

same

proportionas

its existing portfolio atthe beginning ofthe period.We

measure

the portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe currentaccount

residuallyas

thedifference

between

the actual currentaccount

and

the portfolio-growthcomponent,

i.e.PR

ct=CA

ct-x

ct -Sct .To

implement

this decomposition,we

requiredataon

current accounts, savingand

theshareofforeign assets in country portfolios.We

obtain annual dataon

currentaccounts

in currentUS

dollarsfrom

the InternationalMonetary

Fund's InternationalFinancialStatistics.

We

measure

gross national saving as thesum

ofthe currentaccount

and

grossdomestic

investment in currentUS

dollars,and express

bothas a

fraction of

GDP

incurrentUS

dollars, obtaining investmentand

GDP

from

theWorld

Bank's

World

Development

Indicators.We

obtain dataon

theshare of foreign assetsin wealth

from

Kraay, Loayza,Serven and Ventura

(2000).We

restrictattention tothesetof21 industrial countriesfor

which

at least20

annual observationson

this variableare available

over

the period1966-1997 covered by

this dataset.With

dataon

savingand

the portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe currentaccount

in hand,we

estimate a series ofdynamic

linearregressions ofthe form:p q /

(11)

PR

d=a

c+£<|>

w

-PR

Cit_v+£Ycv-S

Ci,_ v+P

cZ

ct+u

ctv=1 v=0

where PRc

tand

S

ctare the portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe currentaccount

and

saving

as

described above; Zct isa vectorof control variables,and

Ud

is awell-behavederrorterm.

We

thenuse

the point estimates ofthe coefficientsto retrievethe impliedimpulse

response

function ofportfolio rebalancing in periodt+ktoan

increase insavingdPR

c•,lin period t, i.e. :

—

.

These

impulseresponses

provideus

with a picture ofhow

3S

ctcountries

change

thecomposition of their portfolios followingan

increase in saving.The

results offoursuch

regressions aresummarized

inTable

1.The

top panelofTable

1 reportsthe estimated coefficients,while thebottom

panel reportsthe corresponding impulseresponse

functions using the21 -countrysample

ofannual

observations.

The

estimated impulseresponse

functions are also plotted in thefourpanelsof Figure8.

We

begin byassuming

that all ofthe slope coefficients are thesame

acrosscountries. In our simplestspecification,

we

alsosetp=0

and

introduce5

lags ofsaving.11

The

results of thisspecification are reported in thefirstcolumn

ofTable

1. In this case, theimpulseresponse

function simply consists oftheestimated coefficientson

currentand

lagged saving.We

find a strong positivecontemporaneous

correlationbetween

savingand

thecurrent account.The

pointestimate of0.6can be

interpretedas the fraction of

an

increase in saving that,on

impact,would be

invested in foreignassets bya countrywith zero initialforeign assets. Thisfraction

would be

slightlyhigher (lower)in creditor(debtor) countries

because

ofthe portfolio-growthcomponent.

Sincethelatter

measures

thecurrentaccount

balancethatwould keep

the compositionoftheirportfoliosconstantfollowing

an

increase in saving, it is by construction positivein creditorcountries

and

negative in debtorones.The

subsequent

lags ofsaving all enter with negativecoefficientsthat are decreasing in absolute value and,with theexception ofthefirst lag, are notsignificantlydifferent

from

zero.These

coefficientscan be

interpreted as thefraction ofthe initialincrease in savingthat is reallocated

back towards domestic

assets ineach

ofthesubsequent

fiveyears. Interestingly, thesum

ofthe coefficientson

lagged saving is-0.09

which

is insignificantly differentfrom

zero. Thissuggests

thatthe initial shifttoward

foreign assets is largelyundone

in the nextfive years, with the bulk of thereadjustmentoccurring in thefirstyearfollowing the increase in saving. This pattern is

consistent with the predictions ofthetheory.

The

restofTable

1 reports avariety of robustnesschecks on

this basic result.We

begin by introducing lagged values ofthe portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe current account,and

findthat thefirstand second

lags are stronglysignificant,whilethird (and higher) lagsare not.12

Although

this slightly altersthe point estimatesofthecoefficients

on

currentand

lagged saving,we

find thattheshape

of impulseresponse

function isverysimilar tothat reported in thefirst regression.

The

main

differenceisthattheinitial shifttoward foreign assets is slightlysmallerthan before, at

50

percent ofthe increase in saving.

11

In unreportedresults,

we

findthatfifthandhigherlagsofsavingareinsignificantlydifferentfrom zeroinmostspecifications,andaddinghigher lags haslittleeffectonthe pointestimatesofthe coefficientsonthe

firstfivelags.

12

We

areassumingherethatthetimedimensionofour panelissufficientlylargethatwe

canobtain consistentestimatesofthe coefficientson thelaggeddependentvariableinthepresenceof fixed effects relyingon large-Tasymptotics.Remember

alsothatsavingisconstructedas investmentplus the currentaccount,andthelatteris highlycorrelated withthedependentvariableinEquation(11). Tothe extentthat

the portfolio-rebalancing componentofthe currentaccountismeasuredwitherrorsthatare persistentover

time,thiscould introduceacorrelation betweenthe residualsandcurrentandlaggedsaving. Inthe specifications withlagsofthedependentvariable,wetest foranddonotrejectthenullofnoserial

dependenceinthe residuals,andsowe canruleoutthispotentialsourceofbiasinourestimated impulse responses.

Inthe next

column

we

augment

the specification ofthe previouscolumn

with several additional control variables.To

the extent thatthere are othershocks

to returns thatchange

the desiredcomposition

of country portfolios,and

totheextentthat these are correlated with saving, thiswill bias our results in directionswhich

depend

on

the signsofthese correlations.For

example,

ifthere areglobalshocks which

raise savingand

investmentin all countries (suchas

changes

inworld interest rates),we

willbe

underestimating the size ofthe initial shifttowardforeignassets

when

savingincreases. Similarly, ifin countries

and

yearsinwhich

saving is high, factorsthatincrease the desired rateof

investment

(suchas

population or productivitygrowth),we

may

againbe

underestimating the shifttoward

foreign assets.To

controlforthesefactors,

we

introduceyear

dummies

tocapture global shocks, population growth,and

Solow

residuals as a proxyforproductivitygrowth.13The

thirdcolumn

ofTable

1reports the results of this

augmented

regression. Populationgrowth

and Solow

residualsenter significantlywith the

expected

negative signs,and

we

find a largershifttoward

foreign assetsthan before, with75

percent oftheinitial increasein savingallocated

toward

foreign assets.However,

thesubsequent

pattern ofadjustment isthesame

as

before, with the initial shifttoward

foreign assets being reversed in nextfew

years.

Inthefinal

column,

we

relaxtheassumption

thatthe slope coefficients inEquation (11) arethe

same

across

countries,and

instead estimate this equation separatelyforeach

country.Because

ofthefairly shorttime-series available foreach

country,

we

adopt

amore

parsimonious

lag structure, introducing onlytwo

lags ofthedependent

variableand

of saving,as

well as populationgrowth

and

Solow

residuals.We

reporttheaverage

and

standard deviation across countries oftheestimatedcoefficients in the last

column

ofTable

1. 14Notsurprisingly,

we

find thatthecountry-13

We

constructSolowresidualsasthegrowthinGDP

atconstantprices lessgrowthinemploymenttimesthe period averageshareoflabourin

GDP,

drawingthelattertwovariablesfromtheOECD

LabourForceStatisticsandNationalAccounts.

Inthepresenceofparameter heterogeneityacrosscountries, thepooled estimates reportedinthe

previoustwocolumnswill not deliverconsistentestimatesofaverage (acrosscountries)ofthese

parameterswhenthereisalaggeddependentvariable(PesaranandSmith (1995)). However,the

averageacrosscountriesoftheestimatedcoefficientswillprovideaconsistentestimateoftheaverage

by-country

parameters

aremuch

less preciselyestimated,and

the dispersion acrosscountries in the pointestimates is large. Nevertheless,

we

find results that arequalitatively

and

quantitativelyquite similar tothoseinthe previous columns.On

average, thefraction of

an

increasein savingthat is allocatedtoforeign assets is0.7,and

this initial shifttoward

foreign assets isquicklyundone

insubsequent

periods.One

drawback

oftheannual dataon which

we

have

reliedso

faristhat it is notinformative

about

theintra-yeardynamics

of savingand

the current account. For 12 ofthe countries in our

sample,

we

were

abletoobtain quarterlyobservationson

thecurrentaccount, investment

and

GDP

beginning in1980

orearlierfrom

theInternational Financial Statistics

and

theOECD

Quarterly National Accounts. Forthesecountries,

we

linearly interpolatethe annual dataon

theforeignasset shareand use

itto construct quarterly portfoliogrowth

and

rebalancingcomponents.

We

thenre-estimate Equation (11) using quarterly data, introducing eight lags of the portfolio

rebalancing

component

ofthe current account,and

eight lags of saving.We

do

nothave

quarterlydataon

population oremployment

growth required to introducethesame

control variablesas

inthe previous regressionswith annual data (Regressions 3and

4 inTable

1).We

therefore include only a setof perioddummies

and

realGDP

growth

as

controls.As

before,we

summarize

the results ofthese country-by-country regressionsby

computing

themean

and

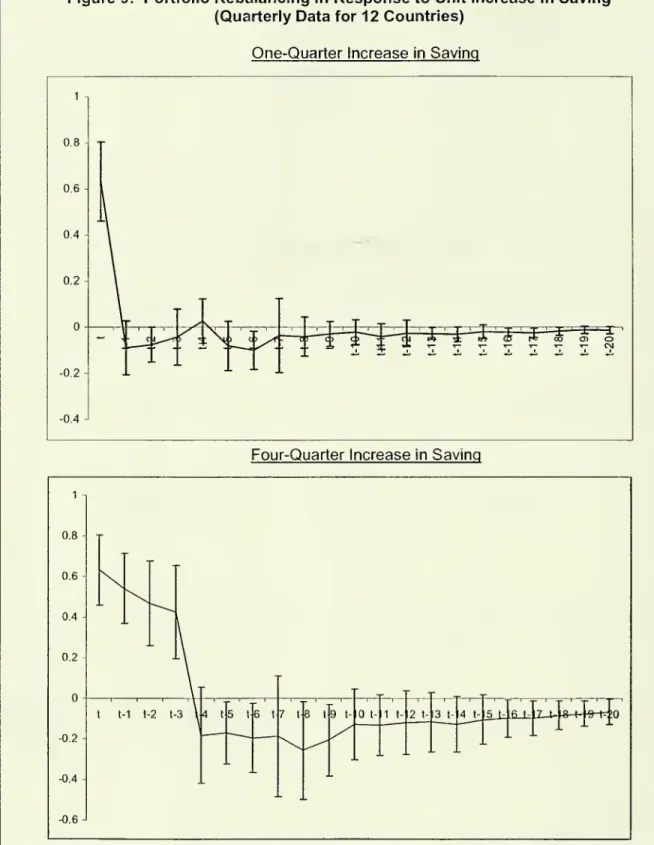

standarddeviation acrosscountries ofthe estimated impulse responses.As shown

in the top panel of Figure9,we

find thaton

impact, justover

60

percentofan

increase in saving thatlastsone

quarteris invested abroad. Beginning immediately inthe next quarter, this initialshifttoward

foreign assets beginsto

be

reversedas

countries run currentaccount

deficits. Ifwe

considerashock

tosaving that lastsfour quarters,the pattern that

emerges

is verysimilar to thatwe saw

in the annual data. This is

shown

inthebottom

panel of Figure 9. During theshock

period, countries run positive but declining current

account

surplusesas

theyuse

response.

We

findresults thatarequantitativelyquitesimilaracross allspecificationsdespitethis potentialsourceofbiasinthe estimates whichimpose parameter homogeneityacrosscountries.

foreign assets

as

a bufferstocktosmooth

investment. Insubsequent

years, countries run currentaccount

deficits inorderto restoretheir original pre-shock portfolios.To

sum

up,while portfolio growth explainsmuch

ofthe long-run variation incurrent accounts, portfolio rebalancing

dominates

in the short run. In all ofourspecifications,

we

find thatthe portfolio-rebalancingcomponent

ofthe currentaccount

follows a

remarkably

clearpattern.On

impact,up

tothree-quartersof ashock

to savingis invested

abroad as

countriesuse

foreign assetsas

a bufferstocktosmooth

investment intheface of adjustmentcosts. In

subsequent

periods, the initial increasein saving

produces

currentaccount

deficitsas

countries shifttheir portfoliosback

totheir original composition.

IV.

The

Current

Account

and

Investment

Over

the past20

years considerable empirical efforthas

been

devoted

todocumenting

the correlationsbetween

investmentand

thecurrent account.Two

stylized facts

have emerged.

First, cross-countrycorrelationsbetween

investmentand

the current

account

areweak

(Penatiand Dooley

[1984],Tesar

[1991]).Second,

withincountriesthetime-series correlation

between

investmentand

thecurrentaccount

isconsistently negative (Glick

and

Rogoff[1995]).We

document

thatthesetwo

stylizedfacts hold in our

sample

ofcountries in Figure 10. In the toppanelwe

plot long-runaverages

ofthe currentaccount

as afraction ofGDP

(on thevertical axis)against long-run investment rates (onthe horizontal axis) forthe21 industrial countriesin our sample.Across

countries,we

find a veryweak

negative correlationbetween

thetwo,with a coefficientof-0.036. Inthe

bottom

panel,we

plotthesame

two

variablesexpressed as

deviationsfrom

countrymeans,

pooling all available annualobservations. Withincountries, the correlation

between

investmentand

thecurrentaccount

is strongly negative, witha coefficient of-0.329.15Thisdifference

between

the correlationsbetween

the currentaccount

and

investment inthe long

and

shortrun are consistent with theview

ofthe currentaccount

proposed

in this paper.To

see

this, it is useful towritethecurrentaccount

and

investment

as

follows:(12)

CA

ct=x

ct -Sct+PR

ct(13) l

ct

=(1-x

el)-S

et-PR

elThese

equationsdecompose

the currentaccount

and

investment into theirportfolio-growth

and

portfolio-rebalancingcomponents.

The

key

observation toexplainthepattern ofcorrelations

between

the currentaccount

and

investment is thatthelong-run relationship

between

thesevariables isdominated by

their portfolio-growthcomponents,

while the short-run relationship isdominated by

the portfolio-rebalancingcomponents.

To

make

this statement precise,we

decompose

thecoefficientof aregressionofthe current

account

on

investment into thecontributions ofportfoliogrowth

and

portfolio rebalancing. Let pbe

this regression coefficientand

define PG_

Cov(xS,(1-x)l)

gnd

PR_

Cov(CA,l)Cov(x-S,(1-x)l)

Sjnceb=3

pg+b

prVar(l) P Var(l) Var(l) ' P P P

'

we

interpret (3PG

and

(3PR

as

the contributions of portfoliogrowthand

portfoliorebalancingtothe relationship

between

the currentaccount

and

investment.When

we

perform thisdecomposition

on

thebetween

estimatorin the top panelof Figure 10,

we

find that (3PG

=-0.041

and

(3PR

=0.005. Consistentwith thetheory,

portfolio rebalancing plays

no

role inthe long runand

the relationshipbetween

thecurrent

account

and

investment reflects only portfolio growth. Moreover, thetheorypredicts thatthecorrelation

between

thecurrentaccount

and

investment shouldbe

Thisisalmostexactlythesameastheaverageofcountry-by-countryestimates reportedinGlickand

Rogoff[1995],

negative in debtor countries

(where

x>1)and

positive in creditorcountries(where

x<1).The

intuition is simpleand

follows immediatelyfrom

thenew

rule: in debtorcountriesincreasesin saving

generate

even

greater increases in investment, leading to currentaccount

deficits, while in creditorcountriesthe increase in investment is less than thatofsaving, leading tocurrent

account

surpluses. Since oursample

ofcountries consistsofa mixture of

15

debtorand

6creditorcountries,we

should expectto find a negativebutnot especially strong correlation

between

investmentand

the currentaccount

in across-section thatpools all countries together. This is exactly

what

we

found

inthe toppanel ofFigure 10. But

when

we

divideour

sample

into debtorsand

creditorsand

compute

thecorrelations separately inthetwo

groups,we

shouldfind a negativecorrelation

among

debtorsand

a positive correlationamong

creditors. Figure 1 1shows

thatthis isthe case.

Of

course,we

have

onlya very smallsample

ofcreditorsand

debtors,

and so these

differences in slopes shouldbe

takenwith a grain of salt.Nevertheless,

we

notethatthey are consistentwiththe theory.When

we

perform thesame

decomposition on

thewithinestimator inthebottom

panel of Figure 10,we

findthat (3PG

=-0.014

and

pPR=-0.315. Consistentwith the theory, portfolio rebalancing is importantin theshort runand

this introduces asourceof negative correlation

between

thecurrentaccount and

investment. In thepresence

ofadjustment

costs, ashock

toincome

in a given period triggersan adjustment process

thatlastsfor

many

periods. In particular,a

positiveshock

toincome

raises savingcontemporaneously and

isfollowedby

several periods of portfolio rebalancing,as

countries

have

higherthannormal

investment financed by currentaccount

deficits inorderto restoretheir pre-shock portfolios.

The

oppositeoccurswhen

thereis anegative shock.

Thus

positiveshocks

triggera "ripple"effectofsubsequent

higher investmentand

lower current accounts,and

vice versafor negativeshocks. This"ripple" effect is a

source

of negative correlationbetween

investmentand

the currentaccount

within countries.V.

Concluding

Remarks

By

reconciling longand

short run data, thispaper

completes

theview

ofthecyclical behaviorofsavings, investment

and

the currentaccount

in industrialcountriesthat

we

firstproposed

inKraay

and Ventura

[2000].Faced

withincome

shocks,countries

smooth

consumption by

raising savingswhen

income

is highand

vice versa.In the short run, countries invest

most

oftheirsavings inforeign assets, only torebalance their portfolios

back

to their original composition in the nextfourto five years. Inthe long run, countryportfoliosare remarkably stable, thenew

ruleappliesand

fluctuations in savings lead'tofluctuationsin the currentaccount

thatare equal tosavings times the

share

offoreign assets in thecountry portfolio.By

usingforeignassets

as

abuffer stock, countriessmooth

investment inordertosave on

adjustmentcosts.

An

interesting implication ofthisview

of international capital flows isthatthestock offoreign assets

and

the currentaccount

aremore

volatilethanconsumption,

investment

and domestic

capital stock. Butthisdoes

notmean

that internationalcapitalflowsare afactor thatcontributesto

making

macroeconomic

aggregates

more

volatileorunstable.

To

the contrary, theview

presented heresuggests

that theabilitytopurchase

and

sell foreign assets allowscountries not onlytosmooth

theirconsumption,

but alsotheir investment. Foreign assetsand

the currentaccount

absorb

partofthevolatilityofthese other

macroeconomic

aggregates.References

Caballero, Ricardo,

"Aggregate

Investment," InJohn

B.Taylorand

MichaelWoodford,

Eds.,

Handbook

ofMacroeconomics,

Vol. 1B.Amsterdam,

The

Netherlands:Elsevier, 1999.

Deaton,

Angus.

Understanding Consumption.

Oxford:Clarendon

Press, 1992.Dixit,

Avinash

K.,and Robert

S. Pindyck,Investment

Under

Uncertainty. Princeton,NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Dombusch,

Rudiger, "Real Interest Rates,Home

Goods,

and

Optimal

ExternalBorrowing,"JournalofPolitical

Economy,

XCI

(1983), 141-153.Feldstein, Martin,

and Charles

Horioka,"Domestic

Savings

and

International Capital Flows,"Economic

Journal,XC

(1980), 314-329.Glick,

Reuven

and Kenneth

Rogoff, "Global versus Country-Specific ProductivityShocks

and

the Current Account," JournalofMonetary

Economics," 35

(1995),159-192.

Kraay, Aart,

and

Jaume

Ventura, "CurrentAccounts

inDebtor

and

Creditor Countries,"QuarterlyJournal of

Economics,

XCV

(2000), 1137-1166.Kraay, Aart,

Norman

Loayza, Luis Serven,and

Jaume

Ventura, "Country Portfolios,"NBER

Working

Papers, No. 7795, July2000.Lewis, Karen, "Trying to Explain

Home

Bias in Equitiesand Consumption,"

Journal ofEconomic

Literature,XXXVII

(1999),571-608.

Lucas, Robert E. "Adjustment

Costs

and

theTheory

ofSupply," JournalofPoliticalEconomy,

(1967)75, 321-334.Matsuyama,

Kiminori, "CurrentAccount

Dynamics

in a Finite Horizon Model," JournalofInternational

Economics,

XXIII (1987), 299-313.Meilon, Robert,

"Optimum Consumption

and

PortfolioRules

in aContinuous-Time

Model," Journal of

Economic

Theory, III (1971), 373-413.Obstfeld, Maurice,

"Aggregate

Spending

and

theTerms

ofTrade: IsThere

aLaursen-Metzler Effect?" QuarterlyJournal of

Economics,

XC

(1982), 251-270.Obstfeld Maurice,

and Kenneth

Rogoff,"The

IntertemporalApproach

tothe Current Account." InGene Grossman

and Kenneth

Rogoff, eds.,Handbook

ofInternational

Economics.

Amsterdam,

The

Netherlands: Elsevier, 1995.Penati, A.

and

M. Dooley, 1984. Currentaccount

imbalances

and

capital formation inindustrial countries, 1949-81,

IMF

StaffPapers

31, 1-24.Persson, Thorsten,

and

LarsSvensson,

"CurrentAccount

Dynamics

and

theTerms

ofTrade: Harberger-Laursen-Metzler

Two

Generations

Later," Journal of PoliticalEconomy,

XCIII (1985), 43-65.Pesaran,

Hashem

and

Ron

Smith, (1995). "EstimatingLong-run

Relationshipsfrom

Dynamic

Heterogenous

Panels". Journal of Econometrics.68

(1995) 79-113. Sachs,Jeffrey,"The

CurrentAccount

and

Macroeconomic

Adjustment

in the 1970s,"Brookings

Papers

on

Economic

Activity, 1 (1981), 201-268.,

"The

CurrentAccount

in theMacroeconomic

Adjustment

Process," .Scandinavian

Journal ofEconomics,

LXXXIV

(1982), 147-159.Svensson,

Lars,and Assaf

Razin,"The

Terms

ofTrade and

the CurrentAccount:The

Harberger-Laursen-Metzler Effect,"Journal ofPoliticalEconomy,

XCI

(1983),97-125.

Tesar, Linda, "Savings, Investment

and

International Capital Flows," Journal ofInternational

Economics,

XXXI

(1991), 55-78.Ventura,

Jaume,

"A PortfolioView

ofthe U.S. CurrentAccount

Deficits". BrookingsPapers on

Economic

Activity. (2001), July.Tabid:

PortfolioRebalancing

and Saving

(An nualData

for 21Countries)

Reqression 1 Rearession 2 Reqression 3 Reqression 4

Mean

SDof

Coef S.E Coef S.E Coef S.E Coef Coefs

CoefficientEstimates sy 0.598 0.096 0.504 0.080 0.746 0.079 0.691 0.286 sy(-1) -0.281 0.133 -0.611 0.102 -0.824 0.104 -0.767 0.383 sy(-2) -0.120 0.106 0.112 0.077 0.109 0.070 0.123 0.167 sy(-3) -0.120 0.095 -0.043 0.073 0.040 0.067 sy(-4) -0.102 0.103 -0.031 0.065 -0.063 0.061 sy(-5) -0.060 0.078 0.020 0.058 0.019 0.057 pr(-1) 0.754 0.056 0.845 0.057 0.837 0.216 pr(-2) -0.114 0.069 -0.081 0.066 -0.152 0.186 pr(-3) -0.031 0.049 -0.076 0.047 dq * -0.375 0.050 -0.390 0.198 dpop -0.684 0.188 -0.267 1.293 CountryEffects

Y

Y

Y

YearEffectsN

N

Y

ImpulseResponses t 0.598 0.096 0.504 0.054 0.746 0.059 0.691 0.286 t-1 -0.281 0.133 -0.231 0.096 -0.193 0.095 -0.179 0.222 t-2 -0.120 0.106 -0.119 0.058 -0.114 0.056 -0.111 0.142 t-3 -0.120 0.095 -0.122 0.060 -0.098 0.054 -0.088 0.106 t-4 -0.102 0.103 -0.102 0.042 -0.122 0.047 -0.059 0.076 t-5 -0.060 0.078 -0.039 0.028 -0.068 0.040 -0.038 0.063 t-6 -0.014 0.024 -0.040 0.037 -0.024 0.057 t-7 -0.003 0.020 -0.019 0.035 -0.018 0.048 t-8 0.000 0.016 -0.008 0.033 -0.014 0.041 t-9 0.001 0.012 -0.002 0.030 -0.013 0.036 t-10 0.001 0.009 0.001 0.027 -0.011 0.032Note: Thistable reportsthe results ofestimating Equation (11)inthepaper. Thefirstthreecolumnsassumeslope

coefficients are he

same

acrosscountries. The lastcolumnreportsthemean

andstandarddeviation acrosscountriesofcountry-by-countryestimates Standard errors fortheimpulseresponsesincclumns(2)and(3)are

simulated using500 drawsfromtheestimateddistributionof coefficients.

Figure

1:The

TraditionalRule

and

the

New

Rule

TraditionalRule

nationalsaving :rvations foran 0.1 -0.05 -Q.Q

O

0-*3 § ( g -0.05-<

£ -0.1 -3o

-0.15 --0.2y=0.231x-

0.062 R2= 0.124*

*

Saving/GDPNew

Rule

0.1 -y =0.939x-0.002R

2 =0.301 Ji.Q5,W"

*

0.05 5alth) § -0.15 *0.1*

^

-1W5*WM

1

^^^

**

£^

+

U

-<%-5

-0.15 --0.2(Saving/GDP)x (Foreign

Assets/W

Note: Thetopi

(gross national

unbalancedpar

bottom) panelplotsthe currentaccount balance as a shareof

GDP

againstgrosssaving interacted with the foreignassetposition),poolingallavailableannual obs«

leiof21