Aufsätze

Abstract: In the analysis of redistribution, not only models based on the territory principle should be considered, but also functionally structured redistribution like collectively negotiated welfare benefits. Combining the methods of difference and agreement with process tracing the article shows that, in the Netherlands and Denmark, the high level of development of functionally ar-ranged redistribution explains the strong party effect on processes of retrenchment in pension; on the other side, the smaller room for manoeuvre for political parties in Germany and france can be linked to the dominance of territorially organized redistribution. Industrial relations and models of functional redistribution affect the influence of political parties on welfare state retrenchment. Keywords: Political parties · Welfare state · Industrial relations · Process tracing ·

Mill′s methods

How and why industrial relations influence

party effect upon welfare state retrenchment.

A comparison of the Netherlands, Denmark,

Germany and France

Christine Trampusch Published online: 09.03.2010 © Vs-Verlag 2010 Prof. Dr. C. Trampusch () University of Bern, Lerchenweg 36, 3000 Bern 9, schweizTel.: +41-(0)31-6313750 Fax: +41-(0)31-6318590

1 Introduction

Redistribution—the transfer of money and benefits from affluent to less affluent market participants—requires the existence of non-market institutions through which resources are distributed and risks are pooled amongst the members of a group (or between groups) (Polanyi 1944, p. 43–55). Redistribution constitutes a gesture of solidarity. It is based upon individual group members being prepared to make sacrifices for the good of the other members of that group. How much is redistributed within a welfare state depends not only upon market income, fiscal policy or upon the way in which benefits are claimed. The extent of redistribution is significantly determined by the social constitution of groups and redistribution coalitions.

In reference to Thomas Marshall′s differentiation between political, social and indus-trial rights, in terms of the constitution of groups, two typical models can be defined: (1) the ‘territorial model’, in which on the basis of political rights, social rights are created by the introduction of obligatory social insurance or of state welfare benefits, thus placing demands upon the state which organises the redistribution and distributes and administers resources. (2) The second model is a functional model. Here, redistribution takes place upon the basis of industrial citizenship, with trade unions implementing social progress through social benefits as agreed upon in collective bargaining agreements. The func-tional model is especially gaining in relevance in the area of pension policy. In a host of countries, trade unions and employers′ associations have negotiated sector-level agree-ments, which finance and regulate pensions (Trampusch 2007).

In comparative welfare state research, as practised within political science, the ques-tion concerning the extent of redistribuques-tion under welfare state policy, and how this extent can be explained, represents a focal point of current research. Within the context of cur-rent debate on whether a retrenchment process is taking place within welfare states, and thereby also a dismantling of redistribution policy and solidarity, many studies however focus solely upon redistribution, itself based upon the territorial model. State expenditure and benefits from state social insurance schemes and programmes are made the focus of attention. Accompanying this on the independent variable side is the investigation, within the political-administrative sphere, of the influence of actors and coalitions of territo-rial interest representation. The question is asked whether, and which (party) political actors reduce social welfare benefits. Within this context, case-oriented studies concern-ing reform processes in pension policy have drawn attention to the fact that the party effect varies in international comparison.

In this way, parties in the Netherlands and Denmark not only have greater influence upon pension policy compared to Germany and france, but reductions have also become easier to implement in recent years (Green-Pedersen 2001; schludi 2005; Conceição-Heldt 2006, p. 192; Green-Pedersen and Lindbom 2006; schulze and Jochem 2006; Pal-ier 2007).

By means of a case-oriented comparison between the Netherlands, Denmark, Ger-many and france, this article will illustrate that differing degrees of party effect in these countries are linked to differing degrees in the development of functional redistribution, in other words of pensions based on collective agreements. When analysing the current transformation of redistribution policy within welfare states, undertaking a

complemen-tary investigation into both the dependent variable as well as the independent variable side is recommended. Not only should the degree of development of functionally struc-tured redistribution be considered; it should also be investigated what effects pensions based on collective agreements have upon the reform process of state-organised redistri-bution policy.

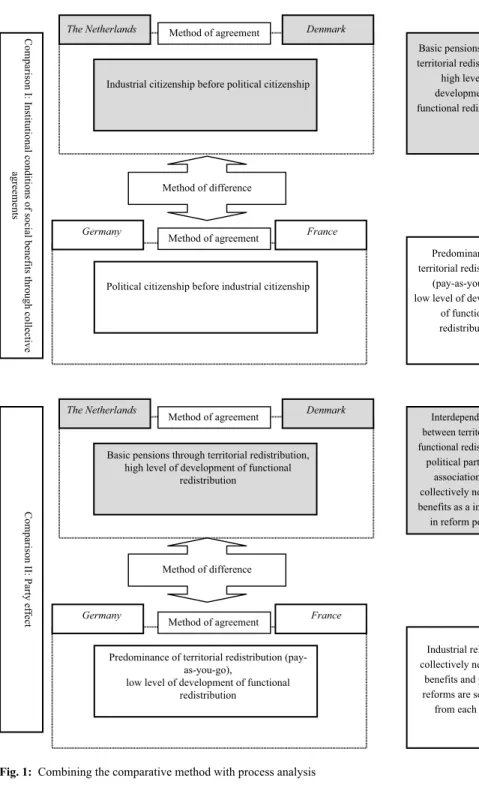

At the methodological level, this article links the combined application of the method of agreement and the method of difference (Mill 1874, p. 283–284; Skocpol and Somers 1980, p. 183) with within-case process tracing. It is based upon historical-institutional-ist argumentation. We will proceed in three steps: in the first, for the cases chosen, ter-ritorially as well as functionally structured redistribution is described in detail using the examples of state pension policy and of collective agreements on pension benefits. In both of the following steps, on the basis of a two-step country comparison, we will ana-lyse the relationship between functionally structured redistribution and party effect. The comparison illustrates the relevance of evolutionary paths and links a historical analysis of paths of political and industrial opportunity structures with current political reform preferences. The first step of the country comparison is historical. Beginning with Tho-mas H. Marshall′s differentiation between political and industrial citizenship, using the selected cases, we illustrate the thesis that the chronological sequence of the institution-alization of political and industrial citizenship is decisive for the degree to which redis-tribution is based upon the functional principle. In countries in which industrial rights were institutionalized and applied before political rights—such as Denmark and the Netherlands—functional redistribution models are more developed than in countries in which the sequence ran in exactly the opposite way, as in Germany and France. Building upon the relevance of the thesis of structuring effects of democratization processes and of institutionalization processes of industrial relations, in the second stage of the country comparison a second thesis is developed, of which the plausibility is in turn illustrated through the combined application of the method of agreement and the method of differ-ence: In countries in which the functional redistribution model is traditional, and is firmly established alongside territorially organised redistribution (Denmark, the Netherlands), parties and competition between parties determine the course of the retrenchment of state social policy more than in countries in which the functional principle plays a subordinate role (France and Germany).

this paper is structured as follows: the following (second) section places this article within the context of political science research into the welfare state. Emphasis is placed upon studies into party effects and into reform processes in pension policy in the four countries. The third section takes each county in turn and describes the pension system on the one hand, and pensions based on collective agreements on the other. The fourth section sets out the method of comparison. The two following sections then conduct the two-step country comparison. The fifth section clarifies why evolutionary paths of democratiza-tion and of institudemocratiza-tionalizademocratiza-tion of industrial relademocratiza-tions bear relevance to the emergence and development of functional redistribution, and verifies this using the four countries. The sixth section investigates the effects of institutions of functional redistribution on reform politics. The seventh section concludes and discusses how an historical-institutionalist analysis of the paths of political and industrial integration can be linked to newer concepts of incremental institutional change.

2 Retrenchment and redistribution: a view of comparative welfare state research

two debates constitute the focus of current research into the welfare state, as conducted within political science. First, the debate over whether, and to what extent retrenchment— and with it a reduction in redistribution policy and solidarity—has taken place. Secondly, there is the question of which political factors explain retrenchment processes or the absence thereof (starke 2006).

for a long time, the thesis of a reduction in redistribution policy and solidarity (van Oorschot 1998) stood opposed to the antithesis that retrenchment remains difficult and that welfare states can in no way be said to be on the path towards a residual social secu-rity model (Pierson 1994). In the meantime however, case-oriented, qualitative studies as well as quantitative aggregate data analyses have indicated that state social policy has experienced curtailments (starke 2006, p. 115). Palier (2007, p. 85) stresses the fact that over the last fifteen years, in the area of pension policy in numerous countries, measures have been taken to cut state expenditure. From case-oriented analyses on concrete reform measures in individual countries, it can be taken that in the pension policies of a host of countries, benefits were indeed cut, entitlements restricted and market-based schemes introduced (eg. Pierson 1994, p. 15; Green-Pedersen 2001; Korpi and Palme 2003; Palier 2006, 2007). In the meantime, even quantitative analyses concerning social expenditure and the distribution of income in OECD countries regard the retrenchment thesis as hav-ing been confirmed (Allan and Scruggs 2004; scruggs 2006), even if for example the study by Kenworthy and Pontusson (2005, p. 450) has shown that welfare states in the nineties redistributed more than in the eighties, which goes against the thesis of welfare state retrenchment.1 Despite heated debate concerning how one should define the

depend-ent variable (Green-Pedersen 2004), it is noticeable that the question of reductions in redistribution is analysed in particular by means of state social benefits.

If we pass from the dependent to the independent variable side, we notice that in the explanatory analysis of retrenchment processes, the relative influence of various politi-cal factors is often referred to, with the influence of politipoliti-cal parties and the competition between them as well as the relevance of institutional points of veto receiving particular consideration (cf. Huber et al. 1993; Green-Pedersen 2001; Bradley et al. 2003; Kittel and Obinger 2003; Korpi and Palme 2003; Allan and scruggs 2004; Amable et al. 2006). A point of focus in the debate is the question in how far (party) political actors exert their influence, and if they do, whether it is rather the left-wing parties, the christian-demo-cratic parties or the middle classes and parties representing them who are responsible for the scale of state social expenditure, and with it the extent of redistribution and solidar-ity (cf. in detail Emmenegger 2007; starke 2006). In this way, in their analyses of the determining factors of state redistribution policy, Korpi and Palme (2003) and Bradley et al. (2003) conclude that the strength of left-wing parties exerts decisive influence upon the scale of such policy, and that in countries where the Left is strong, cuts in social expenditure are difficult. There are studies, however, which show that social democrats 1 In their analysis however, Kenworthy and Pontusson (2005, p. 455) do not take into account the welfare programme which has remained the most comprehensive in expenditure terms, namely that of state pension schemes.

can conduct cuts in social expenditure more successfully than right-wing parties (Ross 2000; Kitschelt 2001; Green-Pedersen 2001). Allan and Scruggs (2004) and Amable et al. (2006) find that parties of the Right make deeper cuts.

Quantitative analyses therefore centre around the question of whether parties have an influence and if so, which parties influence retrenchment processes, and to what extent. In contrast, case-oriented studies have highlighted interesting results concerning the coun-tries in which parties exert a strong influence upon restructuring and in which ones they do not; due to consensus imperatives, the party effect is limited by non-party actors such as upper chambers or trade unions and pensioners′ associations. In this regard, the Neth-erlands and Denmark show themselves to be representatives of the former group, and France and Germany representatives of the latter. In his analysis of retrenchment proc-esses in the Netherlands and Denmark, Green-Pedersen (2001) demonstrates that political parties have been the driving force behind reductions in social expenditure. He attributes this to the structure of inter-party competition. In the case of Denmark, Green-Peder-sen (2006) and Green-PederGreen-Peder-sen and Lindbom (2006) confirm the party effect. AnderGreen-Peder-sen (2006) stresses the influence of competition between parties upon pension reforms in the Netherlands. Studies concerning France and Germany however show that the influ-ence of parties is less. In the case of France, Conceição-Heldt (2006, p. 150) and Palier (2007, p. 89–90) point to the influence of trade unions and their public protest actions. In the case of pension reforms in Germany on the other hand, schludi (2005) and schulze and Jochem (2006) have shown that parties are only capable of effecting reforms when they succeed in demanding the agreement of the upper chamber and of trade unions. Moreover, Myles and Pierson (2001) and Palier (2007) have proved that pension systems in France and Germany are difficult for parties to reform as ‘pay-as-you-go’, contribu-tion-financed systems (which dominate in those countries), combine with veto coalitions to offer resistance (Pierson 1994). By contrast, Denmark and the Netherlands belong to that group of countries in which a capital-funded system dominates the area of pension policy (Palier 2007).

The focusing of the redistribution debate upon state social policy and upon the influ-ence of political factors is surprising in as far as a host of studies have since appeared, which point out that countries in which state pension provision have traditionally been complemented by schemes existing at company or at sectoral level maintain these hybrid systems in the current transition phase (Haverland 2001; Myles and Pierson 2001; Brooks 2002; ebbinghaus 2006). Myles and Pierson (2001, p. 330) draw attention to the fact that welfare states which developed late, and in which the ‘pay-as-you-go’ system is far less developed, and which thus have a strong second and third pillar—such as the Neth-erlands, Denmark and Australia—find it easier in the current transition phase to extend capital-funded pensions further. In her quantitative study on pension reductions in 57 states, Brooks (2002, p. 500, 516) shows that reductions are higher in countries with com-pany pension schemes. In the case of the Netherlands, Haverland (2001) demonstrates that the multi-pillar system in that country is the result of contingent processes, however pension benefits based on industrial agreements are a decisive influence upon retrench-ment policy. Company pension schemes and pensions based on collective agreeretrench-ments indeed figure within current research. What is still missing however, are on the one hand systematic investigations into which mechanisms give rise to welfare state restructuring,

and under which conditions non-state collective models of pension provision influence this; on the other hand, it has yet to be analysed whether and how collectively negotiated pension schemes influence the party effect.

If we summarize the body of research into retrenchment processes, we can hold the following to be uncontested: (1) Retrenchment takes place internationally; (2) research investigates in particular the influence of political parties; (3) even in those countries selected for this study, reductions in pensions have taken place, whereby in the Neth-erlands and Denmark parties exert a greater influence than in France and Germany; (4) studies undertaken concentrate upon analysing the reductions in redistribution policy upon state social policy, in other words upon territorially organised redistribution; (5) in view of the independent variables, the main focus of attention falls upon the territorially organized interest representation. In the following sections, we will demonstrate that an analysis which includes industrial relations on the side of the dependent variable as well as on that of independent variables, represents a useful complement in the investigation of retrenchment processes in welfare states.

3 The functional redistribution model through collectively negotiated benefits

As discussed above, the present study, in reference to Marshall, differentiates between two redistribution models—redistribution based upon the territorial principle, and redis-tribution which is functionally organised. Through his concept of ‘social citizenship’ Tho-mas Marshall (1964) points out that welfare state redistribution has as a pre-condition the sequential institutionalisation of civil, political and social rights (‘civic citizenship’ ‘polit-ical citizenship’ and ‘social citizenship’). In differentiating between polit‘polit-ical and indus-trial rights (‘indusindus-trial citizenship’), Marshall (1964, p. 94) drew attention to that fact that due to collective agreements, so-called ‘social progress’ can be created not only through social rights (through legislation on minimum wages or an obligatory social insurance scheme), but also through industrial rights. According to Marshall (1964, p. 94), through collective bargaining agreements, trade unions are able to establish ‘a secondary system of industrial citizenship’—effectively ‘industrial’ rights—which stand ‘parallel and com-plementary to the system of ‘political citizenship’’.

Collective forms of social security—non-market institutions which organise redistri-bution—are therefore the result of the use of ‘political rights’ and of ‘industrial rights’. Social benefits through collective agreements can be interpreted as a model of redistribu-tion, offering a lesser degree of solidarity than state social policy, but which nonetheless redistributes more than is the case under purely market-based solutions. Nevertheless, social benefits through collective agreements do mean less redistribution and solidarity. In a system of social benefits through collective agreements, redistribution is no longer based upon the territorial principle, in which risk compensation is carried out with the help of national funds between sectors, trades and firms, but upon the functional princi-ple. According to this principle, the productivity of those firms participating in the collec-tive agreement determines first and foremost the degree of redistribution. This of course does not exclude—and which the case of the Netherlands shows in particular—that reg-ulation by collective contract or by legislation can increase potential redistribution. In

functionally organised redistribution, adherence to a collective agreement decides over redistributive benefits; in territorially organised redistribution, it is one′s nationality or place of residence, or whether the employment contract falls within the jurisdiction of national labour and social law, which is decisive. Within a territorial model, redistribution is linked to geographical jurisdiction, however not necessarily to nationality. In countries in which collective agreements on social benefits exist, a model is thus added to territori-ally organised redistribution and solidarity, and which is primarily borne by a functional coalition between trade unions and employers.

this study will attempt to analyse to what extent collective agreements on pension benefits are in place in the countries selected, as well as what traditions exist and the cur-rent level of development of such provision. Before that however, the individual pension systems will be examined.

A common element of the Danish and Dutch pension systems is that a relatively gen-erous basic pension and standard benefits comprise the central components of the first pillar, that of state pensions (Anderson 2006; Green-Pedersen 2006). The Dutch AOW system is financed from contributions from all incomes, is organised according to the capital principle and is indexed to the minimum income level. The Danish basic pen-sion is comprised of two elements: firstly from the Folkepenpen-sion, organised according to the pay-as-you-go, financed by taxes, which is linked to pre-conditions concerning one′s place of residence and linked to wage growth in the private sector; secondly, from a com-plementary, obligatory capital-financed system of pension provision (ATP), introduced in 1964 and in which contributions and benefits are calculated according to working hours and not to income. In both countries, the basic pension is the most important type of pen-sion for penpen-sioners (Frericks et al. 2006, p. 478–481). What is further common to both countries is that the second pillar is comprehensive, and comprised of pensions based on collective agreements, that is to say of pension provision schemes, which are regulated by sectoral collective agreements. In this way, territorial redistribution, as provided by the basic pension, is complemented by functional redistribution. Whilst in the Netherlands, such collective agreements on pensions have a long tradition, with participation to sector pension funds obligatory for firms since legislation dating from 1949, in Denmark (AMP) collective agreements on pensions were only introduced in 1991. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, Denmark did conclude public sector collective agreements with company pension provision (Green-Pedersen and Lindbom 2006, p. 252). In Denmark as well as in the Netherlands, the third element, or pillar, of pension provision exists in the form of individual, private and voluntary savings schemes.

A common characteristic of the french and German pension systems is that both systems are dominated by contribution-financed pension provision, obligatory for all employees. For a long time, the French system has comprised three pillars. The first pillar does not only comprise the contribution-financed basic state pension ( régime général), but also the contribution-financed, obligatory complementary pension, which is regulated by national collective agreements ( retraite complémentaire). The second pillar comprises voluntary, supplementary company pension funds ( retraite supplémentaire), which are capital-financed; the third pillar is made up of private provision (Veil 2004, p. 53). On average, pensioners have pension entitlement across 2.8 systems (Veil 2004, p. 53). The first and second pillars are contribution-financed. The complementary pension has been

obligatory since 1972 and is administered in the private sector by ARRCO ( Association des Régimes de Retraite Complémentaire). The German pension system on the other hand was dominated until recently by the obligatory public pension scheme ( Gesetzliche Rent-enversicherung). Company pensions were primarily available to public-sector employees and to better-paid employees in the private sector. Through the collective agreement of 1998, which was concluded in the chemical industry, collectively negotiated pension pro-vision made its way into manufacturing industry.2 finally in 2001, collectively negotiated

pension provision was further extended, next to private provision, through the Riester pension reform. In the same year, the metal manufacturing sector reached a collective agreement on pension provision.

thus in Germany, pension provision is based decisively upon the territorial redistribu-tion model. This is also the case in France, although the contriburedistribu-tion-financed, obligatory complementary pension ( retraite complémentaire) is based upon national, cross-sector collective agreements, which were concluded for the first time between 1947 and 1961, but which also include a risk compensatory element between various sectors (cf. Table 1). Furthermore, since 1972, participation in this complementary scheme has been obligatory for all employees and companies participating in the basic pension scheme. This means that for access to the redistribution model of the complementary pension, the fact that employment contracts fall within the jurisdiction of french social and labour law is deci-sive. Scheme access is not determined by the collective agreement. The aim of national collective agreements is much more to take account of the interests of employers and of employees. They set down decision-making powers of employers and of employees with regard to the fixing of contributions and benefits; however, this takes place across compa-nies, trades and sectors (ARRCO 2001). This can also be expressed in the following terms: In france, the state has co-opted a functional redistribution model and transformed it into a territorial one.

thus systems of collectively negotiated pension provision exist in all four countries; however, as table 1 shows, these differ vastly in terms of their structural characteristics.

the Netherlands has the most highly developed system of collective agreements on pension benefits, and Germany the least highly developed. Furthermore, the Dutch model is regarded as a prototype for a high-quality system of collectively negotiated pensions, founded upon solidarity, and composed of four collective social mechanisms—conven-tion, covenants, contractual agreements and coercion (Rein and turner 2001, p. 137). In Denmark and France, the levels of pension coverage are also very high.

What therefore are the reasons why in the Netherlands and Denmark functional redis-tribution enjoys relatively high status, whilst in france and in Germany, pension provi-sion is based upon the territorial principle? Before demonstrating that the differing mixes of territorially and of functionally organized redistribution can be related to institution-alization processes in industrial relations and to paths of democratization, let us describe the comparative method applied.

2 In the case of Germany, we consider the chemical and metal working sectors only. In the con-struction industry as well as in the public sector, wage-based pension provision has existed for many years.

Characteristic

Denmark

france

Netherlands

Germany

Extension (e.g. based on the ‘erga omnes principle’); in general Yes, but voluntary following demand of employers and trade unions. Pre-condition: law; “absence of extension” (traxler

1994 , p. 179) Yes, quasi-automatic ( ex-lege ); formal application by

employers and trade unions to Minister of

employ

-ment obligatory; “pervasive extension practice” (

traxler

1994

, p. 179)

Yes, upon application by employers via Ministry for Social

Af

fairs. Require

-ment: agreement must cover the majority of employees concerned; “limited exten

-sion practice” ( traxler 1994 , p. 179)

Yes, upon request by either employer or trade union via the Ministry for

employ

-ment; “limited extension practice” (

traxler

1994

,

p. 179)

Year of initial collective agreement/level/coverage

since 1991 (AMP: Arbejds-markedspensionerne ); last collective agreement 2004 (Jør gensen 2004 ); 93% of employees (Green-Pedersen 200 6 , p. 467); unemployed,

sick and certain wage groups (young persons and higher income groups) not covered (Immer

gut

2006

a

);

sectoral, administered by employers and trade unions; however employ

-ers′ representatives are in the majority in the pension funds (Immer

gut

2006

a

);

funds invest (Green-Peder

-sen 200 6 , p. 468); financial monitoring by economics Ministry . Since 1947, AGIRC for

white-collar employees; since 1961,

ARRCO for employees; 90% (Döring 2001 ); in 2000, ARRCO had 16.2 m contributory mem

-bers and 9.5 m pensioners (ARRCO

2001

, p. 1

1);

inter

-sectoral and national

collective agreements; fi

-nanced by pay-as-you-go; administered by employers and trade unions; state does not intervene in the admin. of schemes (L′Observatoire des retraites

2003

).

since introduction of col

-lective agreements; 91% of employees (

eIRO-NL

2004

);

in 2005, 829 pension funds in existence (incl. company pension schemes) (Immer

gut

2006

b

); obligatory; adminis

-tered by employers and trade unions; pensioners′ assocs. obtaining increasing rights of consultation (Kaar and Grünell

2004

); risks pooled

within each sector (Anderson 200

6

, p. 725).

Metal industry since 2001, last agreement in 2006; in 2006, 5% of employees drew the

Metallr

ente

—

200,000 employees and 11,000 companies (Ge

-samtmetall

200

7

).

Chemical industry: since 1998, last agreement in 2005; 4% of employees subject to the agreement use

Chemiepensionsfonds

(Chemiepensionsfonds 200

7

); in December 2003,

scheme included over 200,000 employees (BA

VC 2004 ). Table 1: able 1:

Characteristic Denmark france Netherlands Germany Legal obligation/extension

No legal obligation; no extension.

Since 1972, legislation re

-quires all employees insured under the basic scheme to also be insured in pension systems based upon collec

-tive agreements; extension through the 1972 act. Yes, legislation from 1949 requires companies to par

-ticipate in sectoral schemes; extension through the 1949 act. No formal obligation, however

Tarifvorbehalt

(collective agreement is a precondition for receiving governmental support for collectively negotiated pen

-sions); no extension.

Levels of benefit/pension

-able age

DC system, pension payable dependent on life expect

-ancy; women receive lower pensions (Green-Pedersen 200

6

, p. 470); pensionable

age 60 yrs.

DC System, pensions calculated on points system, points can also be accu

-mulated during periods of sickness or of unemploy

-ment; additional points awarded to employees with more than 3 children; pensions linked to wage level (Conceição-Heldt 200

6

, p. 172), points-related

pension being increased by 20% (L′Observatoire des Retraites

2003

); equal

benefits for all employees. Pensionable age under ARRCO is 65yrs. (60 yrs. in exceptional cases). Formerly DB system, but DC system gaining in impor

-tance; AOW + collectively negotiated pensions = 70%

of final salary (Immer

gut

2006

b

); Pensionable age 65

yrs.

DC system with minimum pensions; pensionable age 65 yrs.

Table

1:

Characteristic

Denmark

france

Netherlands

Germany

Financing structure/extent of state support

Capital-financed (Immer -gut 2006 a ); Employer 2/3,

employee 1/3 of monthly contribution (between 3% and 17% of gross earnings); tax exemption for contribu

-tions, however taxation deferred; In 2004, approx. 9% for most employees (Green-Pedersen

200

6

, p.

468).

financed by employer and employee (60:40

ARRCO);

contributions tax-exempt; Under

ARRCO, employee

contribution amounts to 7.5% of gross earnings (e

IRO-france

2004

).

Capital-financed, employer 2/3, employee 1/3; in 1998, employers contributed 6.7% of aggregate wages into collectively negotiated pen

-sions, employees contributed 2.3% of wages (Anderson 200

6

, p. 728); calculated

on net income above

AOW

pension (Immer

gut

2006b

);

contributions are tax-exempt; “comprehensive” fiscal aid (Anderson

200

6

, p. 728); In

2003, fiscal aid amounted to EUR 9.6 bn, or 21% of GNP

.

Metal industry: employer′s contribution

eu R 319 per employee p.a. ( Altersvor -sor gewirksame Leistun-gen

). Employers must use

this as deferred compensa

-tion.

They are allowed to

defer max. 4% of gross earnings; tax exemption and freedom to choose amount until 2008. Chemical industry: employer′s contribution EUR 319 per employee p.a. ( Altersvorsor

gewirksame Leistungen ). Employer also pays eu R 13 per eu R 100

deferred compensation, or same rule as in metal industry

.

Most recent developments

AMP

system serves as

accelerator for expansion of collectively negotiated social benefits, bringing trade unions to exercise wage moderation in order to collectively negotiated pensions (Øverbye

1998

, p.

185).

Current collective agree

-ment in force until 2008.

Increase in contributions and conflicts due to falls in share prices; collectively negoti

-ated pensions increasingly used for early retirement. In the 2005 wages round, the chemical workers′ trade union requested an auto

-matic contribution from employers.

so ur ce : O w n c om pl et io n o n t he b as is o f t he l ite ra tu re q uo te d i n t he t ab le Table 1: (continued)

4 The method: the linking of comparative method and process analysis

In this study, using a two-step comparison, we will combine Mill′s methods of difference and agreement, however without following the determinist causal concept linked with these methods. In the first comparison, the historical part of the study, we will investigate institutional conditions for functional redistribution arrangements (pensions based on col-lective agreements). In the second comparison, that concerning current process policy within welfare states, we argue that the extent of functional redistribution influences the party effect during the retrenchment phase. Both of these country comparisons are com-plemented by within-case analyses of the selected countries. The within-case analyses serve to contextualize the investigation historically along the lines of process tracing. In this way, it becomes clear that the objective of this comparative study is not to dem-onstrate causal effects, but rather to identify mechanisms. The aim is not to deduce or to falsify, but to proceed in an explorative, heuristic and inductive manner.

the method of agreement and the method of difference can be traced back to John stuart Mill (1874). If one applies these methods within the framework of causal analy-sis, differences in the dependent variable can be explained by differences in possible independent variables using the method of difference. The method of agreement on the other hand is applied in order to explain similarities between the dependent variable with similarities in independent variables. It should be remembered that Mill formulated his methods on the basis of a determinist and thus a static definition of causality. Whilst the method of difference seeks to identify sufficient conditions for a particular phenom-enon, the method of agreement contributes to determining necessary conditions. Both the method of difference and the method of agreement can be applied in a combined form, which not only Mill (1874, p. 283–284) indicated (‘indirect method of difference’ or ‘joint method of agreement and difference’), but also Ragin (1987, p. 39–42) and Skocpol and somers (1980, p. 183). Due to their determinist understandings of causality, Mill′s methods assume the absence of errors in measurement, of interaction effects as well as of monocausality (Lieberson 1991). The associated advantages and disadvantages as well as the suppositions and usefulness of Mill′s methods generally are the subject of much con-troversy within comparative political science (Jahn 2007, p. 17–18; Lieberson 1991).

Process analysis is of increasing relevance in comparative political science, where it is also used as a method of within-case analysis complementing qualitative or quantitative comparative studies in a meaningful way. The aim of process analyses is to reconstruct processes. Through this, false correlations or equifinalities (several conditions lead to the same result) can be detected, the influence of intervening variables upon relationships between independent and dependent variables can be examined more closely, and light can be cast upon sequential or situative interaction effects (Mahoney 2004, p. 88–90; Blatter et al. 2007, p. 157–166). Having been applied over time in numerous forms of emphasis, through contextualisation of evidence in time and space, process analysis pro-vides greater depth of focus. Process analysis therefore has less to do with the question of the causal effect, and more with the identification of causal mechanisms. It is not a matter of identifying the effect, which can be detected with a dependent variable due to the changes in independent variables, but rather of specifying those “recurring processes, which link certain causes to certain effects” (Mayntz 2002, p. 24).

In this comparison then, how should one implement the linking of the country com-parison with process analysis in concrete terms? Our analysis stresses the relevance of evolutionary development paths. We wish to demonstrate that, due to the creation of the associated arrangements for functional redistribution, patterns of institutionalization in industrial relations and of democratization can serve as historical course setters for cur-rent political reform processes, and influence the party effect within the present restruc-turing of welfare states. The analysis does not intend to exclude concurring explanations, but aims more at a configurative explanation, which intends to make the relevance of his-torical sequences plausible. Correspondingly, the choice of cases as presented is directed less at analysing particular explanatory factors. The case selection is more theory-ori-ented, and—consciously—according to the dependent variable: theory-oriented in as far as the selected cases each stand for two specific configurations of institutionalization in industrial relations and paths of democratization, allowing us to apply and develop further Marshall′s differentiation between political and industrial rights for the analysis of party effects; according to the dependent variable, because the cases were selected according to whether they show a tradition of functional redistribution (collectively negotiated pen-sion benefits) and whether they show a party effect in the present phase of restructuring. Nonetheless, it should be noted that case selection according to the dependent variable is very controversial in political science, as it is open to the problem of selection bias (ebbinghaus 2005).3

table 1 sets out the procedure followed in the two-step country comparison. In the comparison between both sets of countries, Denmark and the Netherlands on the one hand and france and Germany on the other, the method of difference has been applied in both steps. In the comparison between Denmark and the Netherlands and that between France and Germany, the method of agreement has been applied in each. To take Skocpol 1979, p. 37), the cases have been applied as mutual, configurative contrasts. This means that we have chosen two sets of cases, whereby in one the phenomenon we seek to understand (collectively negotiated pensions, party effect) can be observed (positive cases, skocpol 1979, p. 37), but not in the other (negative cases, Skocpol 1979, p. 37). Correspondingly, the logic behind this comparison lies in searching for similarities in the independent vari-ables within the positive cases by applying the method of agreement. We then confront the positive cases with the negative set, applying the method of difference. Further, in the negative cases, we examine—again by means of the method of agreement—whether the independent variables as found in the positive cases do not also appear in these. Process analysis has also been applied with regard to two aspects; firstly, this analysis is gener-ally process-analytical in character, in as far as the countries have been observed over a long period of time, and make a two-step comparison—historical and current process policy. Secondly, process analysis has been applied in the first comparison, the historical comparison, in order to demonstrate the relevance of sequences of democratization and of institutionalization in industrial relations in the establishment of collectively negoti-3 In this regard, the author agrees with ebbinghaus (2005, p. 144–145), who argues that selection

according to the dependent variable poses no problem as long as one does not seek to general-ize beyond the cases, but treats the cases as configurations representing complex development paths.

ated pensions. To conclude, we can say that this investigation complements a qualitative country comparison with within-case process analysis. In this way, the time factor is integrated into the analysis by means of historical contextualization and observation over time (Fig. 1).

5 Institutional conditions of social benefits through collective agreements

Collective agreements can allocate social benefits. This raises the question, under what conditions trade unions and employers′ organizations establish a system of collectively negotiated social benefits. With reference to Marshall′s differentiation between political and industrial citizenship rights, the following theses can be formulated: (1) the institu-tionalization sequence of political and industrial rights influences decisively the extent of collectively negotiated benefits (Ebbinghaus 1995, p. 66). (2) Societies in which indus-trial rights were institutionalized and applied before political ones show a greater extent of functionally organized redistribution than countries in which events evolved inversely. thus social rights can be institutionalized in different ways, and when analysing socie-ties′ levels of development with regards to social policy, industrial relations must not be overlooked.

According to ebbinghaus 1995, p. 56), political and industrial rights fulfil differing functions and mobilise in differing arenas. Whether associations use the political or the economic sphere, is influenced largely by historical institutionalization processes, espe-cially by the way trade unions and employers became integrated within political and economic spheres during the course of industrialization, of nation building, or the devel-opment of states. Where political rights were developed earlier than industrial ones, asso-ciations used the political sphere in order to realise their social policy demands. This had the effect of promoting state social insurance whilst delaying social benefits based on collective agreements. If however industrial rights were developed earlier than political ones, and associations used collective agreements in a comprehensive way to regulate the labour market, then this effectively slowed down the development of state social legisla-tion. For example, this led to collective agreements taking on a central function in social welfare, or expressed another way, territorially organized redistribution being comple-mented by functionally organized redistribution benefits. Expressed yet another way, in reference to Marshall and ebbinghaus, we can argue that the evolutionary sequence of the institutionalization of political and industrial rights establishes structures of opportunity, which decisively influence the social policy preferences of state and associations. The fol-lowing sets out to illustrate the plausibility of this chain of hypotheses using the countries selected with Mill′s methods of difference and agreement.

from comparative research into trade unions, industrial relations and welfare states, a host of indicators can be defined, with which we can operationalize the sequence of politi-cal and industrial integration (eg. Armingeon 1994; ebbinghaus 1995).

the sequence of the institutionalization of political and industrial integration can be ‘measured’ using the years in which the following rights were introduced (here I follow ebbinghaus 1995): With regard to political integration, the introduction of right to form associations, the first year in which at least 50% of the male population was entitled

Fig. 1: Combining the comparative method with process analysis Basic pensions through territorial redistribution,

high level of development of functional redistribution

Method of agreement

Method of difference

Predominance of territorial redistribution (pay-as-you-go),

low level of development of functional redistribution

Method of agreement

Interdependencies between territorial and functional redistribution,

political parties and associations use collectively negotiated benefits as a instrument in reform politics Industrial relations, collectively negotiated

benefits and pension reforms are separated from each other

The Netherlands Denmark

Germany France

Industrial citizenship before political citizenship Method of agreement

Method of difference

Political citizenship before industrial citizenship Method of agreement

Basic pensions through territorial redistribution, high level of development of functional redistribution Predominance of territorial redistribution (pay-as-you-go), low level of development

of functional redistribution

The Netherlands Denmark

Germany France

Comparison II: Party effec

t

Comparison I: Institutional conditions of social benefits through collectiv

e

agreement

s

to vote, the introduction of cabinet responsibility towards parliament, and the introduc-tion of proporintroduc-tional representaintroduc-tion are decisive. For industrial integraintroduc-tion, the following rights are of importance: the introduction of the freedom of association (right to form a trade union), of the right to strike, the year in which the first important national collec-tive agreement was reached and the introduction of statutory works councils or national labour conferences. As a further indicator for the sequence of political and industrial integration, we have used the voter turnout in the year in which the right to form a trade union was legally enacted. If this is high, then political integration can be said to have preceded industrial integration.

If we then compare the Netherlands, Denmark, france and Germany with regard to the sequence of institutionalization and use of political and industrial citizenship rights, the following thesis is plausible: namely, that a relationship exists between the stronger functional redistribution as observed in the Netherlands and Denmark in that in both countries, the creation and use of industrial citizenship rights preceded political ones, whereas in Germany and France political citizenship rights were used first (cf. Table 2). By applying the method of difference, one is able to establish a relationship between the differing extent of functional redistribution in Denmark and the Netherlands on the one hand, and france and Germany on the other, with different paths of democratization and institutionalization in industrial relations.

With reference to the independent variable, Denmark and the Netherlands, each dem-onstrating a developed system of sector-based, functional pension provision, are similar in such a way that with the aid of the method of agreement, the plausibility of the thesis, as formulated above, can be further strengthened. The first national collective agreement in Denmark was concluded in 1899, whilst a cabinet accountable to parliament was only introduced in 1901. In contrast, Denmark had already introduced freedom of associa-tion (right to form a trade union) in 1849, with in that year, only 4.7% of the populaassocia-tion participating in elections. In Denmark as in the Netherlands, the institutionalization of industrial integration preceded its political equivalent. The first national collective agree-ment in the Netherlands was concluded in 1907, proportional representation was only introduced as late as 1918. When in 1872 freedom of association was introduced, a mere 2% of the population took part in elections. A further similarity between both countries lies in the fact that the introduction of state pension insurance only took place following the conclusion of initial collective agreements on a national scale. State pension insurance was introduced in Denmark in 1922 and in the Netherlands in 1913. The conclusion of national collective agreements however had already been reached in Denmark in 1899 and in the Netherlands in 1907.

france and Germany, both demonstrating a less well developed system of sector-based pension provision, show a similarity in the independent variable, allowing us to apply the method of agreement in respect of this group. In both, political integration preceded industrial integration. In France, the first national collective agreement was achieved in 1919, thus 44 years after the reform of parliamentary government. When freedom of asso-ciation was introduced in 1884, 18.4% of the population already participated in elections. Political integration also preceded its economic equivalent in Germany. There, the first national collective agreement was reached in 1918, but as early as 1871, 50% of the male population was eligible to vote. When in 1918 freedom of association was introduced,

Denmark

Netherlands

france

Germany

timing of political integration and industrial integration

Industrial integration predates political integration

Industrial integra

-tion predates political integra-tion Political integration predates industrial integration Political integration predates industrial integration

Political integration a) freedom of association

a) 1849 a) 1855 a) 1884 a) 1869 b) Male suf frage (50%) b) 1849 b) 1896 b) 1848 b) 1871 c) Parliamentarianism c) 1901 c) 1868 c) 1875 c) 1919 d) Proportional representation d) 1918 d) 1918 d) 1919 d) 1919

Industrial integration a) freedom of

Association (right to form a trade union)

a) 1849 a) 1872 a) 1884 a) 1918 b) Right to strike b) 1849 b) 1872 b) 1864 b) 1918 c) Collective bar gaining c) 1899 c) 1907 c) 1919 c) 1918

d) Statutory works councils/national workers′ councils

d) 1936 1899: September Compro

-mise (two years before the introduction of parliamentary democracy)

d) 1919

d) 1936

d) 1920

Voter turnout in the year in which the right to form a trade union was legally enacted (freedom of association) (as a percentage of the population)

4.7

2.0

18.4

49.9

Year in which an obligatory public pension insurance scheme was introduced

1922

1913

1910

1889

Year in which an obligatory public sickness insurance scheme was introduced

1933

1929

1930

1883

timing of public insurance schemes and collective bargaining

Collective bar

gaining predates

public insurance schemes

Collective bar

gaining

predates public insur

-ance schemes

Public insurance schemes predate collective bar

gaining

Public insurance schemes predate collective bar

gaining so ur ce s: R ow s 2 a nd 3 : e bb in gh au s ( 19 95 ); r ow 4 : A rm in ge on ( 19 94 , p . 8 1, T ab le 3 .3 ); r ow s 5 a nd 6 : A lb er ( 19 87 , T ab le A 7) Table 2: t

49.9% of the population took part in elections. A further similarity between both countries can be seen in the fact that—in contrast to the Netherlands and Denmark—the introduc-tion of state pension insurance was introduced after initial naintroduc-tional collective agreements were reached. In France and Germany, state pension insurance was introduced in 1910 and 1889 respectively; the first national collective agreements in those countries were concluded in 1919 and 1918.

6 The relevance of collective agreements on benefits to party effect

Based upon Marshall′s differentiation between political and industrial citizenship rights, we can formulate conceptual considerations, allowing us to include collectively nego-tiated social benefits—and with it functionally defined redistribution—in the analysis concerning restructuring processes within welfare states. The differing paths that the development of collectively negotiated benefits and of functional redistribution took in the countries under investigation coincides with the differing paths taken by the formation of political and industrial integration. Whilst in the Netherlands and Denmark, where the territorial model offers merely a basic cover with standard benefits, industrial citizenship rights were institutionalized and applied before political ones; in france and Germany, where the territorial model is comprehensively organised and the ‘pay-as-you-go’ sys-tem dominates, the process was exactly the opposite. As a second thesis, the following deliberations are intended to examine whether also during the negative growth phase of welfare states, historical processes of institutionalization within both political and eco-nomic spheres have decisive influence upon preference formation with regard to the pub-lic-private mix. If so, this could go some way to explaining why in the Netherlands and Denmark the party effect is greater than in Germany and France.

As discussed above, case studies show that in Denmark and the Netherlands, the influ-ence of political parties upon pension policy reform is substantial, whilst parties in france and Germany are subject to strong consensus constraints, which limit their influence. following on from the differing evolutionary paths that institutionalization in industrial relations and democratization have taken in the four countries discussed here (with Den-mark and the Netherlands bearing similarities to each other as do france and Germany), we will now demonstrate that in Denmark and the Netherlands, the preference forming of state and of associations with regard to the public-private mix of social security took a different path than in France or in Germany. In the Netherlands and Denmark, both state and associations define collective agreements on pensions as being complementary to pension provision from the state. In contrast, employers and trade unions in Germany and France have for a long time given preference to territorial pension provision. This does not only lead to them massively resisting pension cuts as proposed by parties, particularly since systems financed by the ‘pay-as-you-go’ principle are generally associated with the forming of veto coalitions. It is also a consequence that at the politics level, systems of collectively negotiated pensions show themselves to be relatively separate from state pension policy reform.

For the 1970s and 1980s, a host of studies concerning the Netherlands draw attention to the fact that collective agreements on pensions have influenced restructuring processes

within the welfare state of the Netherlands (Haverland 2001; trampusch 2005). When the Dutch government began introducing comprehensive cuts within its social security schemes, employers and trade unions opened up the system of collective agreements to social benefits (Trampusch 2005). On the one hand, new benefits were introduced, such as industrial agreements on early retirement; on the other, cuts in state benefits were compensated by an extension of collectively negotiated benefits. The latter was especially evident in the collective agreements on pension provision (Caminada and Goudswaard 2005, p. 175–176). At the end of the 1980s, the Wages Policy Department of the Dutch Ministry for Social Affairs stated: “that the consequences of the reduction in state benefits … were largely compensated by collective agreements” (DCA 1989, p. 27). In the 1990s, collective agreements on social benefits became the subject of three-sided agreements concerning the reform of the welfare state (trampusch 2005). Recently, Cox (2001, p. 485) has seen the use of wages policy as a means to reform state social policy within the context of trade unions′ wage restraint. Further, he refers to the fact that collective agree-ments on social benefits financed by wage increases are also the result of strategic con-siderations on the part of the government: “Wage crowding and nonwage compensation are two mechanisms Dutch policymakers used to substantially alter labour-market rela-tions. The brilliance of the strategy is that wage restraint, an idea once used to legitimate the expansion of the Dutch welfare state, is now used to justify dramatic curtailments of social protection” (Cox 2001, p. 485). Such compensation for cuts in the state pension scheme cannot however be only attributed to the willingness on the part of employers and trade unions. Haverland′s analysis (2001) of pension policy reforms since the 1980s has also shown that Dutch social policy legislation heavily favoured this approach in as far as the law stipulates that the first and second pillars together must make up 70% of pension benefit.

As in the Netherlands, political parties in Denmark are also able to fall back on col-lective agreements in matters of pension reform. This serves to expand considerably their ‘competence’ in pension policy. Moreover, the Danish case shows four special charac-teristics: (1) the introduction of collectively negotiated pensions (the AMP system) was the result of an accumulation of contingent events; over time however, trade unions in particular have come to associate a strategic use with it (Green-Pedersen 2006, p. 479–84; Green-Pedersen and Lindbom 2006, p. 253–254). Whilst in the Netherlands therefore, state pension policy is coupled with collectively negotiated pensions through legisla-tion, and thus by the state, in Denmark it is of a more informal and contingent nature. (2) shortly after the introduction of collectively negotiated pension schemes, the government made means testing for basic pension provision more rigorous (Green-Pedersen 2006, p. 488). (3) Over recent years however, Danish pension policy has followed these cuts with relatively incomprehensive ones (Green-Pedersen 2006; Green-Pedersen and Lindbom 2006). In fact, collective agreements on pensions made the Danish pension system more solidarity-based. (4) Further, the evolution of collectively negotiated pensions are linked to wage policy, as in the Netherlands (trampusch 2007). Even if therefore in Denmark the extension of collectively negotiated pensions, which took place at the beginning of the 1990s, did not stem from any political master plan, it can be said nonetheless that wages policy and the possibility of devolving pension policy into industrial relations must have influenced the process of reform significantly. Furthermore, it is notable that ex post,

political actors and collective bargaining partners increasingly recognise in the collec-tively negotiated schemes a usefulness in terms of organisation and reform policy.

As is the case in the Netherlands and Denmark, collectively negotiated pensions are also firmly established in France, albeit functioning according to the territorial redistribu-tion principle. In France, no strategic coordinaredistribu-tion of collectively negotiated pensions and state pension policy is observable either. In contrast with the Netherlands, there is a very distinct separation between public and collectively negotiated pension benefits at the politics level (Conceição-Heldt 2006). Consequently, the government can only carry out reforms to the basic scheme and within the public sector (Veil 2005, p. 26), areas in which it has generally to contend with massive resistance and mobilisation potential on the part of trade unions (Conceição-Heldt 2006, p. 190–193). Nevertheless, it should be empha-sized that since the beginning of the 1990s, the government has promoted collectively negotiated pension schemes through various reforms, by improving the state′s promotion of these schemes (Conceição-Heldt 2006, p. 190–193). Despite this, with reference to reform politics, france displays no direct interconnection between state reform policy and industrial relations.

As regards German pension policy, numerous studies have made repeated reference to the high veto potential of trade unions, as well as to the separation existing between state pension policy and industrial relations at the level of reform politics (Hemericjk and Manow 2001; schludi 2005). However, change has become evident since the last pension reform. Collective agreements on pensions were introduced in Germany within the framework of the Riester pension reform of 2000/2001. This was instituted parallel to reductions in the state pension and to an extension of market-organised pension provi-sion. During the reform process, the trade union representing chemical workers, IG BCE (Industriegewerkschaft Bergbau, Chemie, Energie), emerged very strongly as an advo-cate of state support of collectively negotiated pension benefits. The reason however, as to why the government took up the option offered by IG BCE can principally be traced back to two factors. On the one hand, the later Federal Employment Minister Walter Riester had already laid much of the ground work as the then deputy leader of IG Metall, with his idea of a ‘wages fund’ to finance early retirement, when, as a representative of the executive circle of IG Metall, he spoke for collective agreements on social benefits. On the other hand, during the course of the Riester reform, and the wage negotiations of 2000 and 2001, a wages policy dynamic developed, which put IG Metall under pressure to open its collective agreements up to early retirement and to pension benefits, due to previous agreements reached by IG BCE.

By applying the combination of the methods of difference and of agreement, we can conclude the following: In the Netherlands and Denmark, reform politics show interde-pendencies between territorial and functional redistribution. Political parties, as well as employers and trade unions, use collective agreements at a time of reductions in territorial redistribution as a resource for functional redistribution. In Germany and France by con-trast, industrial relations are effectively separated from reforms to state pension policy. furthermore, in the Netherlands and Denmark, industrial rights were used before politi-cal ones, whereas in France and Germany, the opposite is true. Using the comparative method as a basis, we can conclude that the differing evolutionary paths of institutionali-sation in industrial relations, and of democratization in both groups of countries account

for the fact that in Denmark and the Netherlands, political parties′ room for manoeuvre is extended in the reform of territorial redistribution policy through collective agreements, but not in France or in Germany. Whilst in France and Germany, the preference formation of state and associations in the public-private mix has evolved such that employers and trade unions give preference to territorial redistribution rather than to the functional type (and correspondingly, act as firm veto actors in the reform of state pension policy), in the Netherlands and Denmark, functional redistribution is seen as having equal importance as territorial redistribution. To express this another way: as political parties in Denmark and the Netherlands are able to use industrial relations as a source of flexibility in the restructuring of state pension policy, their room for manoeuvre in pension policy is much greater than in Germany and France.

7 Conclusion

Within the analytical context of the differentiation between territorial and functional redistribution, in reference to Marshall, and by means of a case-oriented comparison between the Netherlands, Denmark, france and Germany, this study has shown that the level of development of functional redistribution—collectively negotiated pension provi-sion—explains the strength of the party effect upon the reduction of state redistribution policy. As its starting point, our analysis had the following four considerations: (1) with collective agreements on social benefits, state and associations can at the functional level complement territorially organised redistribution, as guaranteed through state minimum benefits and obligatory social insurance. For this reason, it is useful to present considera-tions as to what extent collective agreements can offer redistribution. (2) The extent to which social policy is also organised and financed by collective agreements (or expressed another way, a mix of functional and territorial redistribution), is influenced decisively by the evolutionary paths of democratization and of institutionalization in industrial rela-tions. (3) With regard to the dependent as well as to the independent variable, studies which attempt to explain the degree of redistribution should include industrial relations within their analysis. (4) Increased investigation of employers and trade unions may not only help to explain at what point collective agreements regulate and finance social ben-efits. If employers and trade unions conclude agreements which finance and organise redistribution by means of wages policy, this can also have effects upon reform politics and party effect within the reform of state-organised redistribution policy.

With reference to the influence as exercised by functional redistribution models and industrial relations upon party effect in retrenchment processes, two patterns become evident in the four countries examined: (1) In the Netherlands and Denmark, collective agreements on pensions are used strategically, not only by employers and trade unions, but also by government in reform processes concerning pension policy. (2) In France and Germany, the collectively negotiated pension schemes are relatively isolated from reform in public pension policy. Through the coupling of functional and territorial redistribution models in reform politics, Dutch and Danish political parties′ room for manoeuvre in times of pension reform is increased. In pension policy reform, collectively negotiated pensions allow them to achieve more than their German and French counterparts. This

study has argued that historical institutionalisation processes of political and industrial citizenship rights may function as switchmen ( Weichensteller) for differences in party effects.

The role and function of collectively negotiated social benefits within the current trans-formation of welfare states is expected to become the subject of further and deeper empir-ical analysis. Within the context of the present study, two questions arise: (1) Due to what driving forces do industrial relations become an agent of social order in times of cutbacks in territorial redistribution? (2) How can a historical-institutional analysis of evolutionary paths of political and industrial opportunity structures be linked in a meaningful way, to an analysis of current political reform preferences and interests, without falling victim to an illusion of continuity?

One way of approaching both of these questions could lie in analysing welfare state retrenchment processes as a phenomenon of incremental institutional transformation, and in so doing to develop concepts. These concepts would allow us firstly to differentiate between institutional change as change by reform and institutional change as change “by default” (streeck 2005). In the wider context, they would allow us to define more firmly what role politics has in institutional change. Institutional change can simply be linked to reform policy. The state accords mandatory authority and besides legislation, makes money available. It transfers state duties into the intermediary domain of associations, as voter preferences wish it to be so and/or because strategic interactions between political actors open up possibilities for this to happen. Institutional change can also occur “by default”, however. This means that change can also take place without the mobilisation of political resources and political action, as due to historical institutionalization proc-esses, industrial relations show a predisposition to transfer social security into the collec-tive agreements domain. Associations make industrial relations the source of institutional change. They exploit those behaviour domains inherent to industrial relations opportun-istically, by regulating social security themselves. Change “by default” means that the vested interests of associations and their collective creativity drive transformation. State and politics can hold back from wages policy and allow those things to happen which happen anyway, and simultaneously be a major driving force in state social policy for reforms and cuts. If this is so, collective agreements on social benefits show an interesting facet of the redefinition of the relationship between state and associations in the course of welfare cutbacks. Collectively negotiated benefits are a surprisingly creative response on the part of associations to the exhaustion of the state in its role as mediator between the interests of labour and of capital. The solution lies in associations taking over those state tasks to which they are particularly suited in industrial relations.

References

Alber, Jens. 1987. Vom Armenhaus zum Wohlfahrtsstaat. Analysen zur Entwicklung der

Sozialver-sicherung in Westeuropa. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Allan, James P., and Lyle Scruggs. 2004. Political partisanship and welfare reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science 48 (3): 496–512.