Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 135 The Politics of Retirement: Joel and Ethan Coen'sNo Country for Old Men after

September 11 Arne De Boever

Abstract: This essay shows that Joel and Ethan Coen‘s No Country for Old Men develops a critique of the ways in which the Bush government turned final control into an ultimate political value after the September 11 terror attacks. It suggests that such a response operates within a theological assumption that is dismantled in the film‘s representation of the confrontation between hit man Anton Chigurh and sheriff Ed Tom Bell. Crucially, this confrontation takes place at the moment when the sheriff is about to retire. The essay argues that it is through the counterintuitive representation of this retirement as a political act that No Country for Old Men proposes other ways of governing after September 11.

Résumé: Dans cet article, je démontre que le film des frères Coen, No Country for Old Men, contient une critique de la réponse du gouvernement de Georges Bush aux attaques terroristes du 11 septembre, plus particulièrement du retour du nationalisme, du suspens de certaines libertés civiques, de la généralisation des techniques de surveillance et ainsi de suite. Comme le montre bien le film, une telle réponse est basée sur la croyance théologique en la possibilité d‘assurer une sécurité et un contrôle absolus. L‘article démontre que le film déconstruit cette croyance à travers sa représentation de la lutte entre le tueur à gages Anton Chigurh et le shérif Ed Tom Bell, que le film situe au moment même où le représentant de la loi est sur le point de prendre sa retraite. Selon moi, c‘est à travers la représentation de cette retraite que No Country for Old Men montre la possibilité d‘une autre politique après les événements du 11 septembre.

Keywords: No Country for Old Men, Joel and Ethan Coen, September 11, security, terrorism, retirement, Hannah Arendt, Giorgio Agamben, The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 136 One day humanity will play with law just as children play with disused

objects, not in order to restore them to their canonical use but to free

them from it for good. – Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception

1/ Introduction

In the prologue to The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt famously states the project of her book to be ―to think what we are doing‖ (Arendt 5). Arguing that modern times have saddled human beings with an impoverished notion of work that reduces all of their

activities to ―making a living‖ (Arendt 5), only in order to then take their labor away from them, her book proposes to provide the analytical categories for a richer understanding of our doings. These categories turn out to be labor—―the activity which corresponds to the biological process of the human body‖ (Arendt 7)—, work—―the activity which corresponds to the unnaturalness of human existence‖ and ―provides an ‗artificial‘ world of things‖ (Arendt 7)—, and action—―the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter‖ and ―corresponds to the human condition of plurality‖ that is ― the condition of all political life‖ (Arendt 7). These analytical categories can of course be challenged, but that does not take away any of the conceptual force of Arendt‘s project— a project that gains new resonance today, in the midst of an economic crisis in which human activities once again risk to be reduced to ―making a living.‖

In a later passage in the book, Arendt restates her general argument, but now she adds to it a fourth category that might strike one as surprising in this context, namely the category of play. ―The same trend to level down all serious activities to making a living is manifest in present-day labor theories,‖ Arendt writes in 1958, ―which almost unanimously define labor as the opposite of play.‖

As a result, all serious activities, irrespective of their fruits, are called labor, and every activity which is not necessary either for the life of the individual or for the life process of society is subsumed under playfulness. In these theories, which by echoing the current estimate of a laboring society on the theoretical level sharpen it and drive it into its inherent extreme, not even the “work” of the artist is left; it is dissolved into play and has lost its worldly meaning. The playfulness of the artist is felt to fulfill the same function in the laboring life process of society as the playing of tennis or the pursuit of a hobby fulfills in the life of the individual. … From the standpoint of “making a living” every activity unconnected with labor becomes a “hobby.” (Arendt 127-128)

To be sure, this passage should not be misread as a plea for ―play‖ or for ―hobbies.‖ What Arendt criticizes is the fact that activities that are being called ―play‖ or ―hobbies‖ are

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 137 thereby stripped from their seriousness: their ―worldly meaning‖ is dissolved under the sovereignty of labor as the only serious and meaningful human activity. In a footnote on page 127, Arendt points out that underlying the opposition between labor and play that she analyzes, is the ―real‖ opposition between necessity and freedom, with labor being linked to necessity and play to freedom. Again, it goes without saying that play is not Arendt‘s idea of freedom. If anything, her book challenges the construction of freedom as play and insists instead on freedom‘s ―work,‖ more precisely on the ―action‖ that is the condition of all political life.

Given all of this, one might be puzzled by how a more positive notion of play, or of what in this context one could also more generally call ―non-work,‖ appears in the

philosophy of Giorgio Agamben (see, for example, the epigraph of this essay), who mentions Arendt‘s The Human Condition in the opening pages of his bookHomo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life as one of the major influences in his thought (cf. Agamben 3). (The other influence he mentions is Michel Foucault‘s work on biopolitics, which has received much more critical attention so far.) This raises important questions not only about the notions of work and play in both Arendt and Agamben, but also about the relevance of these notions for the two major issues that underlie their thought, namely that of the human and that of politics. The challenge that Arendt and Agamben pose to those reading in their tracks would then be to uncover the link between work/non-work, the human, and politics so as to understand better the human condition today.

This essay will engage with these questions through a reading of No Country for Old Men, Joel and Ethan Coen‘s faithful film adaptation of Cormac McCarthy‘s novel by the same title. Taking its cue from a political cartoon that parodies the film‘s official poster, the essay analyses No Country for Old Men as a political film that targets the ways in which the Bush government responded to the September 11 terror attacks, by declaring a state of exception—by heightening nationalist discourse, suspending civil liberties, extending surveillance mechanisms, and so on—in the hope that final security could ultimately be achieved. The film‘s representation of the confrontation between the retiring sheriff Ed Tom Bell (played by Tommy Lee Jones) and the hit man Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) reveals such a hope to be theological, and suggests moreover that it inspires a work of justice that is profoundly misled and produces the opposite of what it hopes to produce.

This essay argues that No Country for Old Men works through such a theological practice of justice not in order to abandon it altogether but in order to ―retire‖ it: in order to lead it into a realm of ―non-work‖ from where it could be practiced otherwise. From this perspective, it is the film‘s retiring sheriff who will provide the key to the film‘s politics. As will soon become clear, however, the sheriff‘s retirement cannot be disentangled from the retirement of the other characters in the film: Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a retired welder; Carla Jean Moss (Kelly Macdonald), Llewelyn‘s wife who works at Walmart but is declared

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 138 ―retired‖ by her husband after he finds a satchel full of money (the declaration can be read as an instance of tragic irony, since Carla Jean will be ―retired‖ or ―killed‖ by Chigurh at the end of the film); and Anton Chigurh, the hit man who at the end of the film is the only one who is still standing (―el ultimo hombre,‖ ―the last man,‖ to recall Llewelyn‘s words early on in the film)—the only one who is not retired, but whose prime activity consists in ―retiring‖ or ―killing‖ other living beings. It is by analyzing the film‘s serious play with the theme of retirement that No Country for Old Men‘s ―worldly meaning‖ (Arendt 128) as a work of art—its significance for human beings in the world of today--can be revealed.

2/ “You Can’t Stop What’s Coming”

If one does a quick Google search for images of No Country for Old Men, the first few results are likely to include a political cartoon by R.J. Matson, first published inThe New York Observer, that borrows heavily from the film‘s official poster (cf. Matson 2008). The left half of the image features the Republican heavy-weights George Bush senior, John McCain, and John Warner—the three of them grouped together above the film title. The right half of the image is filled by one of the film‘s taglines: ―You Can‘t Stop What‘s Coming.‖ The immediate message of the cartoon is clear: McCain is being told by Bush and Warner that he is too old for the job of president. The cartoon could also be read more broadly, however, as a critique of the policies of George Bush junior, who was president when this cartoon as well as McCarthy‘s novel and the Coen brothers‘ film first appeared. Indeed, any of the film‘s other taglines—―There Are No Clean Getaways,‖ ―There Are No Laws Left,‖ and ―Nothing You Fear … Can Prepare You For Him‖—could serve just as well to sum up the ways in which the Bush government responded to the September 11 terror attacks.

―What‘s Coming‖ in the film‘s official poster (Figure 1)—and the political cartoon preserves this part of the original image—appears to be a tiny, darkened figure running in the foreground, carrying what looks like a gun in the left hand, and a briefcase in the right. Judging from the film, this figure is more than likely Llewelyn Moss, a sympathetic, all-American Vietnam veteran who comes upon a satchel full of money while he is hunting in the desolate landscape of West Texas, close to the US-Mexican border. It is the money of a drug deal gone wrong. Moss decides to hold on to the money, but both the Mexican drug sellers and the American buyers are on his tracks. As if things weren‘t complicated enough, the Americans also hire a hit man called Anton Chigurh in order to get their money back. No Country for Old Men comes to revolve around the struggle between Moss and Chigurh, a struggle that ends abruptly a while before the end of the film, when Llewelyn is killed by the Mexican drug dealers. This makes for an at first sight uncomfortable series of closing

scenes, in which the film appears to continue beyond its central storyline for much longer than it should. However, in the wake of this initial discomfort there quickly emerges the question of whether the struggle between Moss and Chigurh was really the central story of

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 139 the film, or if there was, perhaps, another story going on whose significance was eclipsed by the struggle between Moss and Chigurh that took up most of the viewer‘s attention.

Figure 1: No Country for Old Men (Miramax 2007)

Before turning to this other story, a few more words about the political cartoon. Like several of the Coen brothers‘ other characters, Chigurh is the embodiment of an unstoppable ―drive‖—beautifully evoked at the beginning of the film when a handcuffed Chigurh steps into a police car that speeds away on an empty desert road—: a man who continues even when all available roads are blocked, and who belongs to an almost superhuman realm of endurance. It might thus turn out that ―what‘s coming‖ in the film is not the tiny Moss running in the foreground of the film poster, but Chigurh, the embodiment of a principle of evil by which Moss as well as everyone else in the film becomes hunted and haunted. Starting with the monologue that opens the film, Chigurh is presented as a figure of an unnamable terror against which one is ultimately incapable of protecting oneself. What constitutes the particularly terrorizing aspect of Chigurh is not so much that his ―work‖ consists of the fact that he puts people forever out of work; it‘s that he does this not in order to make a living, but out of principle. In the end, the satchel full of money is only of

secondary importance to Chigurh; it‘s what he was hired to retrieve, but it does not constitute the meaning of his life. What counts, for him, is not so much the money, as the killings that his being hired to retrieve the money makes necessary. Killing people is the

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 140 quasi-monastic ―rule‖ according to which Chigurh lives (as Carson Wells, a hit man hired to hunt Chigurh, puts it). Neither labor nor play, death is the principle of Chigurh‘s life, the motor or drive of his operations.

Such a figure of a categorical imperative gone AWOL (the only reason why

Immanuel Kant could put forward the categorical imperative as a moral standard is because the imperative presupposes, as Kant‘s examples in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals abundantly make clear, the value of life; cf. Kant 31-33) becomes highly resonant in a time—today—and place—the United States—when the protection against the sudden and supposedly irrational death of terror, and specifically suicide bombing, has become the government‘s main occupation. If the suicide bomber, as Talal Assad in a recent book On Suicide Bombing explains, already challenges the value of life that is pivotal to the Western philosophical, moral, and political tradition, at least the suicide bomber‘s imperative can still be constructed as hypothetical (they blow themselves up because of the promise of the seventy-two virgins in the afterlife; they blow themselves up because of America‘s role in international politics; they blow themselves up out of resentment against the Western, capitalist world; and so on). Chigurh represents a more extreme figure of this construction: a man who does not kill because of anything that is exterior to himself, but because he must do so, because that is the reason of his life.

Given that the political cartoon replaces Chigurh in the film‘s official poster by Bush, McCain, and Warner, the cartoon‘s suggestion might be that these three men are the ―real‖ terrorists against which humanity should be guarded, the ―rogues‖ (cf. Derrida) who are coming and cannot be stopped. Such an interpretation only reinforces the immediate reading that the cartoon invites, namely that these men are ultimately unfit for governing. That it is high time they get out, and make room for change.

Get out is indeed what these old men ended up doing. On November 4 th 2008, the American people voted the Democratic senator Barack Obama into power. When, on January 20 th 2009, Bush‘s vice president Dick Cheney was brought onto the stage of Obama‘s inauguration in a wheelchair, it did indeed appear as if the reign of these old men was finally over (shortly afterwards, however, Cheney would return out of his retirement as one of the harshest critics of America‘s new president, leaving no opportunity unexplored to undermine Obama‘s newly instituted authority). To the relief of many, Obama from his very first days in office embarked on an aggressive politics to undo some of the most devastating measures that his predecessor had put into place, thus bringing about some of the much-needed political change that was the platform on which he was elected (some of the president‘s other decisions, however, have already cast doubt on the actual extent of this political change).

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 141 In this final sense, ―what‘s coming‖ in the political cartoon might also be Obama: either the tiny figure running in the foreground (carrying a gun to fight the war on terror and a satchel full of money to buy out America‘s banks…), or also the spectral Chigurh,

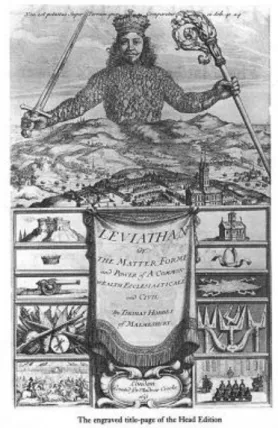

towering over the desolate landscape of West Texas, as some superheroic counter-figure to Chigurh—a figure that, of course, can never be completely disentangled from its criminal counterpart. (The sovereign and the criminal are indeed, related, as Michel Foucault in his 1974-1975 lecture course entitled Abnormal points out; cf. Foucault 93) In this context, and beyond the film poster‘s obvious references to the Western and the horror film, one may also want to consider the striking similarity of the film‘s poster to the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes‘ study of sovereignty (Figure 2), in which a creaturely Leviathan rises above the landscape, wielding a sword in the left hand and a scepter in the right, thus bringing together in a single sovereign figure (made up of many) Chigurh‘s spectral appearance in the background, and Llewelyn running in the foreground, carrying a gun in his left hand and a satchel full of money in his right.

Figure 2. Frontispiece of the 1651 edition of Hobbes‘ Leviathan (Hobbes 2).

Whatever the case may be, the political cartoon perceptively invites one to consider Joel and Ethan Coen‘s film No Country for Old Men not only as a story set in West Texas in the 1980‘s, but also against the background of recent and current political events,

specifically as a story about the struggle between terror and government that continues to take place today, after Obama‘s election. How should governments deal with terror? What is the government‘s relation to terror, what is the relation between state terror and the terror of suicide bombing? What should be the philosophical, ethical, and political values according

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 142 to which one governs in a time of terror? In what follows, it is shown how No Country for Old Men addresses these questions through its representation of a struggle that has remained out of this essay‘s focus so far, namely the confrontation between Chigurh and sheriff Ed Tom Bell. This essay argues that the story of the sheriff and of his retirement at the time when he is confronted with Chigurh holds the key to the film‘s politics, a politics that otherwise risks being eclipsed by the disturbing outcome of the struggle between Moss and Chigurh.

3/ The Sheriff and Chigurh

The main characters of No Country for Old Men are not only Moss and Chigurh, but also sheriff Ed Tom Bell. If the film appears to revolve around the struggle between the first two, this essay argues that their relation needs to be extended so as to include the third figure of the sheriff, whose relation to Chigurh is at least as important, or even more important (given that Moss dies a while before the end of the film), than Moss‘ relation to Chigurh. It is perhaps difficult to notice upon a first viewing, but the sheriff has both the first and the last word in No Country for Old Men. The film begins with a moving monologue in which the sheriff (who will only appear in the film a while later) recalls the men who have

preceded him as sheriffs in West Texas—he mentions both his father and his grandfather— and reflects upon the differences between their times and his. Whereas back then, some sheriffs did not even need a gun to maintain law and order, in Bell‘s time even a gun risks not being enough to protect one from the evil that is out there. A gun might save one‘s body, the sheriff suggests, but it cannot save one‘s soul—and it is one‘s soul that is at risk if one ventures out into the world of today. These thoughts, which are initially spoken over people-less images of West Texas, come to accompany the scene of Chigurh‘s arrest, thus creating the suggestion that Chigurh is a figure of the soul-threatening evil that the sheriff‘s

monologue evokes. (This is confirmed by Chigurh‘s first killing in the film, which follows shortly after his arrest and constitutes the most brutal scene in the film.)

Although the viewer might not entirely realize it yet, the sheriff—he who is supposed to preserve the peace in West Texas—is thus introduced in the film not as the strong arm of the law, but as a highly precarious figure who is profoundly disturbed by Chigurh. In the face of terror, the sheriff emerges as a figure of a heightened vulnerability, a vulnerability that becomes all the more pressing because the sheriff also represents the law and order that are supposed to keep us safe. In the figure of the sheriff, it appears to be law and order themselves that are under threat, faced with a terror that the humanist presuppositions upon which they are built can barely contain. As Judith Butler in a similar context has noted, this raises the question of how government is going to respond to such destabilizing terror and to the sense of heightened vulnerability that it produces. In her opinion, ―final control is not, cannot be, an ultimate value‖ (Butler xiii) when it comes to responding to terror, because control is inevitably disrupted by other processes that traverse it, and of which it is a part.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 143 Something of Butler‘s point about the impossibility of final control shines through in No Country for Old Men‘s closing scene, which features the sheriff‘s face, looking strangely childlike and intensely aged at the same time, at a loss after the sheriff has just recounted two dreams about his long-dead father to his wife. The first, which involved his father giving him money which he then lost, he can barely remember; the second, however, featured his father riding ahead of him on a mountain pass into the cold, dark night,

shielding a light and fixing a fire up ahead to receive the sheriff whenever he would get there. This light and fire can easily be read as the light and fire of justice: as the dream of final control that is projected up ahead, with the sheriff‘s long-dead father protecting it until the sheriff will get there himself, in other words: until the sheriff himself will have died. One does not have to be a psychoanalyst to understand the dream‘s significance: only in death will the sheriff‘s work of justice be completed. Final justice is not a part of this world.

It is no coincidence that this dream comes to the sheriff in the early days of his retirement, after he has given up on the quest for justice because he feels ―overmatched‖ by the world of today. Indeed, this is one of the ways in which No Country for Old

Men establishes a link between the particular kind of politics towards it gestures and the sheriff‘s retirement. As the sheriff explains it in a conversation towards the end of the film, ―I always felt that when I got older, God would come into my life. He didn‘t.‖ This

confession reveals the theological assumption behind the sheriff‘s life-long work of justice, namely the fact that he operates within the belief—or more precisely, on the basis of a ―feeling‖—that when he got older, God would step in, presumably to complete the work of justice that the sheriff as a young man took up. God did not step in, however, and this radical absence of transcendence brings into sharp relief not only the fact that the sheriff‘s work, even though he is retiring, is hardly done—an unfinishedness that is arguably the condition of all retirement; for which one of our works are ever really completed during our life-time?—, but also the bitter failure of all of the sheriff‘s life-long attempts at preserving law and order. One gets the distinct sense that the confrontation with Chigurh, which is the broader context within which the story of the sheriff‘s retirement is being told, leaves the sheriff defeated: disillusioned with the project of justice to which he has dedicated his life— in vain.

However, this vanity only depends upon the theological assumption that the work of justice could somehow be completed once and for all. Indeed, if one of the mottos of truth and justice cited in the film is ―to dedicate oneself daily anew,‖ the sheriff responds that he will dedicate himself twice daily, or even thrice daily, not realizing that such multiple dedications are not going to solve the problem. It is precisely this theological dedication to truth and justice, a dedication that operates in the assumption that final truth and justice will ultimately be realized, that the film‘s representation of the sheriff‘s retirement, of his

becoming retired, allows the viewer (and perhaps also the sheriff) to work through. In this sense, Chigurh can be read along more positive lines as the active agent of such retirement, as the one who retires; retirement thus reveals itself in the film as a kind of premature death,

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 144 a dying without dying that only anticipates an even more radical falling out of work that will arrive when the sheriff meets his father again. It is part of the magic of film that it allows the viewer to experience this without actually dying, through the encounter with the otherwise horrific figure of Chigurh. Although Chigurh‘s final ―victory‖ over Moss might be

disturbing, especially given the fact that the seemingly last good man (another ―ultimo hombre‖) in West Texas, sheriff Ed Tom Bell, is retiring, it may actually be necessary to read these two figures together, with Chigurh as the agent of a retirement that actually teaches the viewer something about the sheriff‘s work of justice in response to figures of terror such as Chigurh.

Such a reading is suggested by the close affinity, and intimacy even, between the sheriff and Chigurh that No Country for Old Men develops. Continuing the references to Judith Butler‘s work earlier on, one might say that the close connection between the sheriff‘s heightened vulnerability and the terror of Chigurh reveal something important about the relation between government and terror. Consider, first of all, a number of scenes in which this connection is established. There is, to begin with, the sheriff‘s voice at the beginning of the film, which accompanies the images of Chigurh‘s arrest. This initial

weaving together of the figures of Chigurh and the sheriff is further developed later on in the film, when the sheriff visits Llewelyn Moss‘ trailer home in search for Moss and his wife, Carla Jean. Chigurh has visited the trailer only minutes before, and the Coen brothers have the sheriff sit down in the same exact spot where Chigurh had been sitting (which is almost the exact same spot where, the evening before, Moss joined his wife on the couch). Like Chigurh, the sheriff sees himself reflected in the dark glass of Moss‘ television, their mirror images perfectly overlapping if one were to superimpose these two shots. When the sheriff pours himself a glass of milk from the bottle that stands sweating on the living room table— a sign that the sheriff and his colleague, deputy Wendell (Garret Dillahunt), only just missed their man—this mirroring of images goes beyond the level of reflection, and Chigurh enters into the sheriff‘s constitution, thus further undermining any easy opposition of Chigurh and the sheriff, and instead exposing a certain affinity, intimacy, or similarity even between both, as well as between what these two figures stand for: government and terror.

This contamination of these two categories that are all too easily constructed as opposites becomes uncannily clear through the fact that the sheriff, even though he appears to be at a complete loss in the confrontation with Chigurh, nevertheless seems to understand some profound things about Chigurh and his mode of operation. In a conversation with Moss‘ wife Carla Jean later on in the film, the sheriff talks about a man who was paralyzed by an accident involving a captive bolt pistol—a kind of air pressure gun that is used to put cattle to death. As he is explaining how this type of gun works—by firing a piece of metal into the animal‘s skull that is then sucked back into the gun, leaving no bullet nor exit wound—, the viewer realizes that this is Chigurh‘s signature weapon. The film (unlike McCarthy‘s book; cf. McCarthy 105-106) leaves it unclear whether the sheriff actually realizes this as well; but No Country for Old Men rises above the limitations of its

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 145 characters‘ understanding, and reveals an intimate connection between the sheriff and

Chigurh.

Finally, towards the very end of the film, after Moss has been killed in a motel room in El Paso, the sheriff returns to the scene of the killing and finds the lock cylinder of the motel room door blown out—a sure sign, as by then the viewer knows, that Chigurh has visited the premises. There follows a magisterial, expressionist series of shots in which both the sheriff and Chigurh are shown to be reflected—and possibly see each other reflected as well—in the copper inside of the blown-out lock, with the sheriff standing outside of the door, and Chigurh inside. Given that this reflection occurs in the inside of a lock that has been blown out, the door (which can thus no longer be closed) represents a threshold in disintegration, a border that is no longer a border, where the sheriff practically fuses with Chigurh and vice versa. Given this fusion, it is perhaps no surprise, then, that when the sheriff finally steps into the room, Chigurh turns out to be gone; but he remains spectrally present, as the sheriff repeats one of his signature gestures—making sure that he does not get any of Moss‘ blood on his boots—when he leaves the room.

Even though the sheriff might not realize it, No Country for Old Men thus reveals to its viewers a strange contamination between government and terror that is also one of the Leitmotivs in a film that came out just a year after No Country for Old Men, and whose central madman according to Michael Wood‘s review essay in The London Review of Books, ―resembles the slouching killer of the Coen brother‘s No Country for Old Men‖: the Joker (Heath Ledger) in Christopher Nolan‘s The Dark Knight. ―This is what happens,‖ the Joker explains in a memorable confrontation with Batman, ―when an unstoppable force [―You Can‘t Stop What‘s Coming‖] meets an immovable object‖: they will not kill each other; instead, ―you and I are destined to do this forever.‖ Earlier on in the film, the Joker puts it even more emphatically: ―I don‘t want to kill you. What would I do without you? You complete me.‖ Of course, the ―immovable‖ outlaw Batman hardly resembles the precarious sheriff from No Country for Old Men. But in this case as well, the film reveals the

contamination between two opposite forces, and raises the challenge of how it might become possible to escape the peculiar deadlock of such a situation.

Many have noted that this is also the political deadlock in the post-September 11 world, in which an ever-increasing state violence confronts an intensified terror by which it is contaminated. As the Bush government‘s response to the September 11 attacks has shown, the attempt to completely control terror only ends up producing more terror: even conservative scholars now agree that the US is less safe today than it was before the September 11 attacks. The very idea that government could ever be completely done with terror, in the sense that final control and justice would have been achieved, is—as No Country for Old Men makes its viewers realize—a theological assumption that risks to produce precisely the opposite of what it attempts to bring about. In No Country for Old

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 146 Men, it is the sheriff‘s retirement—a term that is, significantly, associated with Chigurh as well—that provides a way out of this deadlock, by having the sheriff realize the essentially unfinished, human nature of a work of justice that cannot be completed through divine intervention.

One could argue that it is in this insight that the sheriff from No Country for Old Man and Batman from The Dark Knight ultimately do meet. For what does the viewer witness at the end of The Dark Knight other than Batman‘s retirement? Taking on the secret of prosecutor and ―white knight‖ Harvey Dent‘s corruption, ―dark knight‖ Batman retires from his role as the messianic savior, a retirement that revitalizes the civil spirit of Gotham‘s citizens who, following the example of Dent‘s incorruptibility, will from now on work together to make Gotham into a safer place. The film exposes, of course, the dark secret that makes this revitalization of civil spirit possible—the secret of Dent‘s corruption. Thus, it risks to undermine in the real world precisely that for which the fiction of the film allows. However, The Dark Knight also leaves the viewer with something else, which can be found in No Country for Old Men as well, namely the politics of an ―act of retirement‖—a phrase that rings false given the passivity usually associated with retiring; but this is precisely the association that is being drawn into question—that manages to break with government‘s deadlock relation to terror. It is the politics of such an act that is under investigation here.

4/ The Politics of Retirement

In both No Country for Old Men and The Dark Knight, the viewer thus witnesses an act of retirement that has a profound effect on one‘s conceptualization of justice, and more specifically of the work of justice—of the government‘s ways of dealing with terror. Although in The Dark Knight, it appears at first sight that the politics of the film can be reduced to the revitalization of civil spirit that Batman‘s taking on the burden of Harvey Dent‘s dark secret produces, the film also exposes such a secret and draws the viewer‘s attention to the superhero‘s act of retirement and its political significance. It is not the revitalization of civil spirit through ideology that is the politics of the film, but this act of retirement—the act in which Batman withdraws from exercising his messianic power. The film breaks with the politics it projects to instead draw attention to a politics of retirement.

This essay has argued that a similar politics can be found in No Country for Old Men. By exposing the theological assumptions behind sheriff Ed Tom Bell‘s life-long work of justice—his expectation that when he grew older, God was going to step in to finish the job—, the film draws attention to Bell‘s retirement and invites the viewer to rethink the work of justice through its representation of this retirement. The work of justice is indeed a work to which one dedicates oneself daily anew, but without the theological promise of final justice being accomplished at the end of the line. To practice justice otherwise, as a work that turns final control into its ultimate value (to recall Judith Butler‘s reflection on

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 147 September 11 once more), is bound to have adverse effects and to produce only more of (or intensified instances of) the terror that escapes it. This is not a cynical message that would lead to the abandonment of justice; retirement is, in this sense, not the same as ―non-work.‖ Retirement in No Country for Old Men functions as site for the viewer to think through another kind of work, another way of practicing justice that would liberate government and terror from the deadlock in which they have arrived. In this sense, an otherwise horrific figure such as Chigurh might reveal itself to be an active agent of the retirement that the film is inviting one to think: a limit-figure who invites one to imagine the work of justice, as well as the work of government, from an impossible position, as a position from which power is always partly withdrawn.

In The Dark Knight, such a withdrawal leads to a revitalization of civil spirit. In the film, this revitalization depends on the ideological projection of Harvey Dent as the incorruptible white knight who carries all the hopes of Gotham city; but the suggestion remains that such a revitalization might also be possible when this secret is exposed, once the audience has left the cinema, and has reentered into the world. It is not difficult to read the politics of retirement represented in bothThe Dark Knight and No Country for Old Men allegorically, as the representation of a situation in which civil spirit—let us call it ―the power of the people‖—would be revitalized through the withdrawal of executive power. In her recent book Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People, Dana D. Nelson has admirably shown how the rise of executive power in the US— culminating in the messianic, superhero-figure of Obama—has steadily undermined the power of the people, an evolution that is captured most succinctly, perhaps, in George Bush junior‘s post-September 11 admonition to the American people ―to go shopping‖ while the government would deal with the situation at hand. Like the American economy, American democracy has become eroded, and it may require an act of retirement from the executive in order for the principles of the American constitution to be restored.

Such an act of retirement might become especially necessary when faced with the inhuman terror embodied by Chigurh that escapes the limits of law and order‘s humanist presuppositions. It is this type of terror, which, as was discussed above, lies one step beyond the terror of suicide bombing, that the sheriff as a representative of law and order confronts in No Country for Old Men. When, at the end of the film, Chigurh is the only one who is still going—―el ultimo hombre,‖ ―the last man standing,‖ even after he has become involved in a bad car accident—, one realizes that this man, like the Joker in The Dark Knight,

represents a force that cannot be stopped, that will go on being even if the world were to perish (― pereat mundus … fiam!,‖ as Friedrich Nietzsche writes in On the Genealogy of Morals; Nietzsche 108). As the Joker explains, as long as such an unstoppable force meets an immovable object, the battle of these two forces will continue, forever. Both The Dark Knight and No Country for Old Men suggest, however, that an act of retirement might be able to change something to the immovable object confronting the unstoppable force, in such a way that it might be able to dismantle that unstoppable force more effectively,

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 148 paradoxically by no longer pursuing it with the same intensity, and outside of the theological assumption that final control will ultimately be achieved. It is in this way that government may be able to liberate itself to a certain extent from the terror by which it has become contaminated.

In closing, it should be clear that such a liberation does not return one to some pure notion of government that would somehow be free from terror. Indeed, if there is one figure of retirement in No Country for Old Men—in addition to the retired welder Llewelyn Moss, his retired wife Carla Jean, and the retiring sheriff Ed Tom Bell—, it is without a doubt Chigurh himself, who practices retirement actively and has turned the killing of people into the rule of his life. Chigurh is, like the Joker, an extreme figure of retirement, in which government risks to become absent altogether and enter into the realm of a certain death. It is part of the power of No Country for Old Men, however, that it allows one to pass through such extremes without losing one‘s life, thus experiencing—if only for a brief moment— government‘s most radical outside: the outside in response to which power today attempts to govern, but has not yet learned to govern in the proper way.

All of this does not mean, of course, that the three Republicans represented in the political cartoon discussed above should somehow have triumphed over Obama. It doesn‘t mean that George Bush junior and Dick Cheney should somehow be restored to power. The essay challenges, rather, Cheney‘s repeated attempts since Obama was inaugurated to return from his retirement—his refusal to learn from the ways in which he was removed from power. It is from this removal, from a certain temperance of and withdrawal from power, that much can be learned—by anyone in power, including Obama—in a precarious time of terror of all kinds.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998.

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998. Assad, Talal. On Suicide Bombing. New York: Columbia UP, 2007.

Butler, Judith. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso, 2004.

Coen, Joel and Ethan Coen. No Country for Old Men. Burbank: Miramax, 2008. Derrida, Jacques. Rogues: Two Essays on Reason. Trans. Pascale-Anne Brault

and Michael Naas. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2005.

Foucault, Michel. Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1974-1975. Ed. Arnold I. Davidson. Trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Picador, 2003.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 2 (2009) 149 Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Trans. Mary Gregor.

Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

Matson, R.J. ―No Country for Old Men.‖ The New York Observer, Feb. 20 th

2008.http://politicalhumor.about.com/od/johnmccain/ig/John-McCain-Cartoons/No-Country-for-Old-Men.-1ke.htm

McCarthy, Cormac. No Country for Old Men. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Nelson, Dana D. Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morals. Trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale. New York: Vintage, 1989.

Nolan, Christopher. The Dark Knight. Burbank: Warner, 2008.

Wood, Michael. ―At the Movies.‖ http://www.lrb.co.uk/v30/n16/wood01a.html Arne De Boever did his doctoral studies in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. He has published articles on Durs Grünbein, W.G. Sebald, and Giorgio Agamben and is co-editor of Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. This essay is part of a larger work-in-progress in which he explores the relations between politics, the poetic, and various kinds of non-work.