L

-3i

DEWEY

z)

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

AGENTS

WITH

AND

WITHOUT

PRINCIPALS

Marianne

Bertrand,

UChicago

&

NBER

Sendhii Mullainathan,

MIT

&

NBER

Working Paper

00-31

January

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can

be downloaded

without charge from the

Social

Science Research

Network

Paper

Collection at

http://www.ssrn.com

MASSACHUSETfsliSTITTJTr OF

TECHNOLOGY

NOV

8

2000

Agents with

and

without

Principals

Marianne

Bertrand

Sendhil

MuUainathan

*January

14,2000

Who

setsCEO

pay?Our

standardanswer to this question has been shaped by principal agent theory:shareholdersset

CEO

pay.They

use pay to limit the moral hazard problem caused by the low ownershipstates of

CEOs.

Through

bonuses, options, or long termcontracts, shareholders can motivate theCEO

tomaximize

firm wealth. In other words, shareholders usepay

toprovideincentives, a viewwe

referto as thecontracting view.

An

alternative view,championed

by practitioners such as Crystal (1991), argues thatCEOs

set theirown

pay.They

manipulate the compensationcommitteeand

hencethepayprocess itselftopay

themselveswhat

they can.The

only constraints they facemay

bethe availabilityoffunds ormore

general fears, suchas not wantingtobe singled outin the Wall Street Journalas beingoverpaid.

We

refer to this second viewas the

skimming

view. Inthis paper,we

investigatethe relevance of thesetwoviews.I

The

Effect

of

Takeover Threats

on

CEO

Pay

We

begin withsome

illustrativefindings from an earlier paper (Bertrandand

MuUainathan, 1999a). In themid

1980s, severalUS

states passed legislationmaking

hostile takeoversmore

difficult. These laws verylikelyreduced the

power

ofan important discipliningmechanism,

the threat ofbeingtaken overin caseof 'Bertrand: Department ofEconomics, PrincetonUniversity,CEPR

andNBER;

MuUainathan: Department ofEconomics, Massachusetts Institute ofTechnologyandNBER.

e-mail: mbertran@princeton.eduand mullain@mit.edu. Address: Marianne Bertrand, A-17-J-1, Industrial Relations Section, Firestone Library, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, US.A.;Sendhil MuUainathan, E52-380a, Department of Economics, MIT, 50 Memorial Drive Cambridge,MA

02142, USA.We

thank our discussant, George Baker,formany helpfulcomments.poor

management.

How

dowe

expectCEO

pay to respondtothis change in thelegal environment? Inthecontractingmodel, whereshareholdersset

CEO

pay,themain

effect ofthe anti-takeover laws shouldbe onpayforperformance. Shareholders, seeing the weakeningofone discipliningmechanism, should respond by

strengthening another, pay for performance. In the

skimming

model, on the other hand, themain

effectshould be on

mean

pay.CEOs

facing areduced threat ofa hostile takeover cannow

skimmore

resourcesfromtheir firm.

InBertrand

and

Mullainathan (1999a),using panel data on about 600firmsbetween 1984and

1991,we

studythe impact ofthe legislativechanges on the level of

CEO

payand

its sensitivity toperformance.We

focus on the adoption by states of Business Combination Statutes. These statutes impose a

moratorium

period (3 to 5 years) on specified transactions between the target and araider holdinga certain threshold

percentageofstock unlessthe boardvotes otherwise.

They

were adopted by several states at differenttimesthroughthe 1980s

and

early 1990s.The

staggering ofthe laws overtime allowsus to identify theeffect ofthelaws after controllingforyear

and

firmfixed effects.Forthefull sample,

we

foundan

increaseinmean

pay and

an increaseinpayforperformance (especiallyforaccountingmeasures ofperformance). Theseresults are intriguingbecause they aie consistentwith both

views of

CEO

pay.Mean

pay rises as theskimming model would

havepredicted butpay

forperformancealso rises asthe contracting

model

would

havepredicted.To

help resolvethisambiguity,we

lookmore

closelyatwhichfirmsexperienced the increasesinmean

payand

in payfor performance.We

focuson

how

firms with different corporategovernance are affected bythenew

laws.More

specifically,we

separate the firmsinour sampleintotwo groups based on whetherthe firmhasa large shareholder present or not. Largeshareholders are very oftenthought to bean effectivegovernance

mechanism and

are an easyway

tomeasure

corporate governance given the available data (Shleifer andVishny, 1986).

We

definealargeshareholderasanowner

who

has a block ofat leastfivepercent ofcommon

shares in thesample base year. Blocks that are

owned

by theCEO

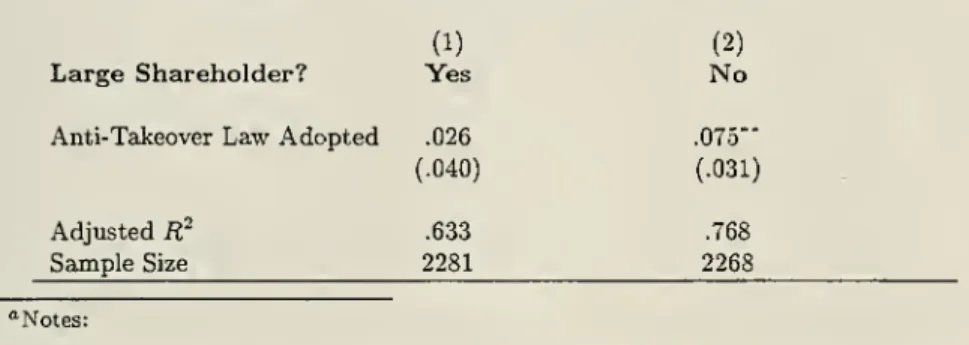

are, ofcourse,excluded.Table 1 reports our findings for

mean

pay.The

dependent Vciriable is the logarithm of totalCEO

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

Combination Statute, year fixed effects, firm fixed effects, a quadratic in

CEO

age, a quadratic inCEO

tenure, the logarithmoftotal assets

and

thelogarithm oftotalemployment.Column

(1) focuses on firmswith a largeshareholder. In thesefirms,we

see astatistically insignificcintincreasein

mean

payofonly2%

followingthelaws.Column

(2) focusesonfirmswithout alargeshareholder.For thesefirms, in contrast,

CEO

pay grew by (this time a statistically significant) 7.5%.The

increaseinmean

pay was actually quite heterogeneous. While firms without a large shareholder experienced a largeincrease, firms withalarge shareholderexperienced almost

no

increase.In Table 2,

we

similarly break apart the pay for performanceresults. Herewe

find the oppositeeffect.The

increaseinthesensitivityofpaytoaccountingperformanceisconcentratedamong

the firms with alargeshareholder. Firms without one

show no

increasein payforperformance.We

have justshown

that in response to the passage of anti-takeover legislation, firms with a largeshareholder increased

pay

for performance, while firms without a large shareholder increasedmean

pay.Thissuggest that the

two

models ofCEO

pay neednotbe contrasted. Instead, theymay

both betrueand

indeed

may

be quitecomplementary. This intuitionis reinforced inthe additional tests thatfollow.II

Further

Evidence

II.l

Are

CEOs

Rewarded

for

Luck?

InBertrand

and

Mullainathan {1999b),we

findtwo

further pieces of evidence. In thefirst test,we

examine

whether

CEOs

are rewarded for observable luck.By

luckwe

mean

changes in firm performance that arebeyond

theCEO's

control. Insimple agencymodels,pay should notrespond tolucksinceby definition theCEO

cannotinfluence luck. Tyingpay

to luck doesn't provide betterincentives (theCEO

can'tchangeluck),but merely addsrisk to the contract (Holmstrom, 1979).

Under

theskimming

view, onthe other hand,paywill becorrelated with lucksincethe

CEO

can use luckydollarsto pay herselfmore.To

empiricallyexamine

the responsiveness ofpay to luck,we

use three different measuresofluck. First,performance on a regular basis. Second,

we

use changes in industry-specific exchange ratefor firms in thetraded goodssector. Third,

we

use year-to-yeardifferences inmean

industry performanceto proxyfortheoverall economic fortunes of a sector. For all three measures,

we

find thatCEO

pay responds to luck. In factwe

find that, for allthree luck measures,CEO

pay is as sensitiveto a "lucky dollar" as toa "genereddollar."

Most

importantly,we

find thatCEO

pay

responds less to luckin the better governed firms. Similarlytoour takeoverresults,

we

find that thepresence ofalargeshareholder reduces theamount

ofpayfor luck. Qualitativelyequivalent resultsholdfor othergovernancemeasures such as thelevel ofCEO

entrenchment(measured as

CEO

tenure interacted with the presence of a large shareholder)and

board size. Again,improved governance leads to greater concordance with the contracting view, while

weakened

governanceleadstogreaterconcordance with the

skimming

view.II.2

Are

Stock

Options

Grants

Gifts?

The

secondtest presentedin Bertrandand

Mullainathan (1999b) focuses on the granting of stockoptions.Contract theory predictsthat

when

stock options are granted, othercomponents

ofpay should be adjusteddown

so thatCEOs

areleftindifferent betweenthepay packagecontaining optionsand

theonecontainingno

options. Supportersofthe

skimming

view, ontheotherhand,would

highlightthe factthat stock optionsdonotappear on balancesheets. Becauseofaccountingrules,firmsdonot chargetheirearningsforthe options they grant.

CEOs

can therefore pay themselves through option grants without affecting the company'sbottom

line. Ifshareholdersmainlylookat thisbottom

line,options grants areaneasyway

toskim withoutdrawing

unwanted

attention. Thus, theCEO

who

gives herselfoptions would not need to lower the othercomponents

of pay at all. Thus, while contracting predicts a charge foroptions,skimming

predicts littlecharge.

In the empirical test,

we

focuson

the question ofhow

the strength ofgovernanceinthe firm affects the chargeforoptions. Usingthesame

governance measuresasinthe previoustest,we

findthatpoorlygovernedon the board, the

CEO

is charged less for each dollar's worth ofoptions granted. Again,we

find greaterresemblanceto

skimming

in thepoorly governedfirms.Ill

An

Independent

Test

The

abovefindingspointtowardsthe coexistence ofskimming and

agencymodels. Inthis section,we

provideanotherindependenttest of thisidea

by

revisitingthe evidenceinAggarwal

and Samwick

(1999). Aggarwaland

Samwick's paperstartswiththe followingimportantprediction ofthe contractingmodel: thesensitivityofpay toperformance should decrease as the riskiness orvariance ofperformanceincreases. In support of

thatprediction,

Aggarwal and

Samwick

find thatthesensitivity ofpaytoperformanceislarger infirmswithlessvolatile stockprices.

In the context of

what

we

haveshown

before, a natural question arises:Does

the tradeoflf betweenperformance volatility

and

pay-performance sensitivity appear strongerin the better governed firms?We

testthishypothesis using a

CEO

compensation datathat covers792diflferentcorporations over the 1984-1991period, provided to us by

David

Yermack.

Compensation

datawas

collected fi-om the corporations'SEC

Proxy, 10-K,

and 8-K

filings. Other datawas

transcribed from the Forbesmagazine annual survey ofCEO

compensation as well as from

SEC

Registration statements, firms'Annual

Reports, direct correspondencewith firms, press reports of

CEO

hiresand

departures,and

stock prices published by Standard&

Poor's.Firms wereselected intothe sample onthebasis of their Forbes rankings. Forbesmagazinepublishesannual

rankingsofthe top500 firms on four dimensions: sales, profits, assets

and

market value.To

qualify for thesample acorporation

must

appearin oneof these Forbes 500rankings at leastfourtimes between 1984and

1991. In addition, the corporation

must

have been publicly traded forfour consecutive years between 1984and

1991.While

this data set covers a smaller set ofcompanies than theExecucomp

database (used byAggarwal

and

Samwick), it does containsome

informationon the structure ofcorporate ownership, whichisnot available in

Execucomp.

compensa-tion

and

the value of optionsgrantedinthatyear. Itisameasure

offlow compensation. UnlikeExecucomp,

Yermack's data doesnot containinformationonthe value of stock options

and

equityshares heldbyCEOs.

In practice,

we

use the logarithm of total compensation.We

use the real rate of return to shareholders (percentagechangeinthe real value of shareholder wealth, including dividend payments) as ourmeasure

ofperformance.

Our

riskmeasure

is based onthe sample varianceofdailystock returnsforthelast120 daysofthe fiscalyear. Following

Aggarwal and

Samwick,we

usethe cumulative distribution function(CDF)

ofthe variance ofreturnsinthe sample asourriskmeasure.The

smallestobservedvarianceinthesample has aCDF

value of0; thelargestobservedvariancehas aCDF

valueof I.We

followBertrandand

Mullainathan (1999a)and

split ouroriginalsampleintotwo

subsamplesoffirmsbased on whetherornot theyhave at leastoneblockof at least fivepercentof

common

shsiresinthesample base yecir (1984), whether the block holder is or is not a director.As

before,we

exclude blocks that areowned by

theCEO.

The

results forthe full sample,not reported here,match

the findings inAggarwal

and

Samwick

(1999).CEO

pay becomes

less sensitive to the rate of return to shareholders as the volatility of stock returnsincreases. InTable 3,

we show

how

the presenceofalargeshareholdermediatesthesefindings. Regressionsareestimated by

OLS. Each

regressioncontainsasindependent variablestheperformance measure, the riskmeasure

and

the interaction ofperformance withrisk. Thisinteraction termiswhat

cJlows us tounderstandthe effectofrisk

on

the pay toperformancesensitivity. Inaddition,we

include firm fixedeffects, yeaxfixedeffects, aquadraticin

CEO

ageand

aquadraticinCEO

tenure (but do not report these coefficients in the Table).Column

(1) focuses on firms with alarge shareholderpresent. Herewe

find support forthe contractingmodel. Highervariance

means

lowerpayforperformancesensitivity.Column

(2) focuses onthe firmswherethere is no large shareholder present. For this group, there is

no

relationship: the pay for performancesensitivity does not

depend

on the riskiness of the stock.Hence

the existing finding that the variance offirmsin theScimple.

IV

Synthesizing the

Empirical Findings

We

have so far laid out aset ofempirical facts that support the general claim that better governed firmsbehave according to the contracting

model

while worse governed ones behave according to theskimming

model.

A

key tomoving

forward will betodevelop amodel

that isconsistent withall thesefacts.A

veryfirstconcern thatneedstobe addressed iswhetherourfindingsrepresentaspuriousrelationship.The

apparentcorrelationbetweenthe use ofoptimalCEO

compensation contractsandthe presenceoflargeshareholdersmight not reflect a truedirect relationship. Instead,

skimming and

weak

governance might berelatedto eachotherthrough

some

thirdfactorthatwe

aie not observing or are not adequatelycontrollingfor.

But what

could thisthird factor be?Firm

sizemight be one example.Owning

5 percent ofthe shares ofalargeflrmismore

expensive so that large firmstypicallyhavelesslargeshareholders.We

can, ofcourse, appropriately control forsizein the abovetestsand

when

we

did so theresults did not change.The

deeperquestion, however, is

why

a third factor (such as size) would consistently lead tothe pattern ofresponsesthat

we

see. For example,why

would

larger firms (whichwould

be correlated with poorer governance)respondto takeoverlegislation with greater

mean

payand

lesspay forperformanceincreases, rewardtheirCEOs

more

forluck, chargetheirCEOs

lessforoptionsand

notaccountforvarianceinchoosingthepayforperformancesensitivity? Ifit isnot becauseofpoorergovernance,then

why?

Itis always apossibilitythatsome

unobserved factor drives our results.We

simply find it hard to point to any such factor that wouldintuitively

match

the consistent patterns thatwe

observe.Assuming

that these resultsareindeed about governance, the simplestway

toexplainthem

seemstobethrough a bargainingmodel.

Suppose

shareholdersand

theCEO

bargain over the pay package.Skimming

could then be

modeled

as the casewhere

theCEO

hasmuch

or all ofthe bargaining power. Contractingwould bethe casewhereshareholdershave

much

orallofthe power. Sucha bargainingmodel

wouldalsohaveWhile

intuitivelyappealing, thismodel

cannotmatch

the results above.To

seewhy, notethat the CoaseTheorem

appliesinthismodel.The

bargainingpower

oftheCEO

willonlydeterminehow much

averagepayshegets,not the structure ofher contract.

A CEO

withmore

bargainingpowerwill not chooseto getmore

pay forluck. She will alsohaveluck shocks

removed

from her pay but will simply expect ahigher averagecompensation. Similarly, there is

no

reason that shewould

want

to be chargedless foroptions grants. Shewill

want

to facethesame

chargeforoptions but merelytake a bigger compensation package overall.More

generally,the optimalcontractwill alwaysbe chosen withbargaining

power

simplydeterminingthe division ofrentsbetween the shareholdersand

theCEO.

An

alternative modeling approach could be to focus on the superior monitoring technology of largeshareholders.

Our

findingscould betheresult ofan optimalcontracting processwhereprincipalsalwayssetpay, whether governanceis

weak

or strong, but face different signal to noise ratioswhen

evaluatingCEO

effort. In firms with large shareholders, principals can

more

easily separateCEOs'

effort from other noisymovements

in firm performance. Such a view could potentially explainwhy

there ismore

pay for luck infirms without large shareholders.

One

would, however, need toassume

that observingmovements

in oilprices or in aggregateindustry shocks requires superior monitoring technology

and

cannot be done ecisily,for

example

by openingthe business section of the daily newspaper.The

monitoringmodel

cannot at all explain ourfindingson the impactoftakeoverthreats.Why

would

principals infirmswithoutlargeshareholders decide to give higherpay once

CEOs

areprotectedfromhostile raiders? Their monitoring technologymay

be weaker but they stillknow

the laws have been passed andshould react tothem. Similarly,thetrade-offbetweenincentivepay

and

varianceofpayareequallypuzzhng.Ifanything, it istheprincipals ofthe well governed

who

should careless aboutstockmarketprice volatility since they have access to better signals of effort.As

a whole, it is hard to imaginehow

differences inmonitoringalone could explain the array ofresults.

Thus

our findingssuggest that governanceis notjust about increased bargainingpower

or bettermon-itoring. Instead, they suggest that governance is about

who

has effective control. In contracting models,we

alwaysassume

thatsome

metaphorical principal controls the pay process.Even

when

governance isweak,this principalstill setspay (perhaps takingintoaccount a worse monitoringtechnology).

Our

resultssuggest thatabetter

model

ofgovernancewould

be onethat recognizes thatgood

governanceiswhat

allows shareholderstomaintaineffective controlof, forexample, the pay process.To

be concrete, consider the details of the pay process. In practice,CEO

pay is usually set via thecompensation committee. This

committee

may

cater to the interests of theCEO

or ofthe shareholders.When

governanceisgood, suchaswhen

thereisalarge shareholderpresent, thiscommitteemay

make

surethat the pay package looks optimalfromthe shareholders' perspective.

The

committee willrespond tothepassage of takeover legislation, or will be

more

reluctant to radse theCEO's

bonusjust because oil pricesrose andso on.

When

governanceisweak, however, this committeemay

bemuch

more

willingto cater totheCEO.

How

does the committee set pay then?

Even

though theCEO

has de facto control of this committee, she stillfacesconstraints.

The

committeemay

be quite reluctant toattractthe attention of shareholdersor ofotherimportant constituencies, such as labor unions or the business press. This places constraints not just on

how

much

can beskimmed

but alsoonhow

skimming

will takeplace. For example,more

can beskimmed

when

firms' performance is high as shareholdersmay

be paying even less attention to the firm.Pay

forluckthen naturally arises. Also, ifshareholders mostly pay attention to their company's

bottom

line, thecompensation committee will grant relatively

more

stock options as they are not charged directly againstearnings.

V

Conclusion

Thisdiscussion highlights asetofopen questionscis

we

move

forwardfromthe empirical regularitiesabove. First,we

need to better understandwhat

happenswhen

theCEO

has gained de facto control ofthe payprocess.

What

are the real constraints on pay setting? This will require amore

rigorous formalization of theskimming

view. Second,we

need to reinterpretwhat

corporategovernance actually does.We

need to reconceptualize governance asthe transfer ofdefacto control ofimportant decisions from theCEO

to theshareholders. Such a reconceptualization will haveapplications

beyond

executive compensation.Take

forexample

the decisionbyfirmstoadopttakeover protectionsuchaspoisonpills. Shouldwe

thinkthisdecisionis

made

with the interests ofshareholders ormanagement

inmind?

This question issomewhat

analogousto whether

we

thinkCEO

payis the result ofoptimalcontracting or skimming. Perhaps governanceplaysa central role in thisapplication too, with well governed firms using poison pills to raise bargaining

power

during takeover attempts

and

poorly governedfirmsusing poison pills toentrenchmanagement.

This finalexample

highlights thebroadervalue ofa reconceptualizationofgood

governanceasbeingwhat

givesCEOs

principals.

References

Aggarwal, Rajesh and

Samwick,

Andrew.

"The

Other Side ofthe Trade-off:The

Impact

ofRiskonExecutive Compensation." JournalofPolitical

Economy

, February 1999, 107(1), pp. 65-105.Bertrand,

Marianne

and

MuUainathan,

Sendhil. "Corporate Governance and E.xecutiveCompensa-tion? Evidence from TakeoverLegislation."

Mimeo,

PrincetonUniversity, 1999a.Bertrand,

Marianne

and MuUainathan,

Sendhil."Do

CEOs

Set TheirOwn

Pay?

The

Ones Without

PrincipalsDo."

Mimeo,

Princeton University, 1999b.Crystal, Graef. In Search ofexcess:

The

Overcompensation ofAmerican

Executives.New

York:W.W.

Norton Co., 1991.

Holmstrom,

Bengt.

"MoralHazard

and

Observability." Bell JournalofEconomics

. Spring 1979, 10(1),pp. 74-91.

Shleifer,

Andrei

and

Vishny,

Robert.

"LargeShareholdersand CorporateControl." Journalof PoliticalEconomy, June

1986,94(3), pp. 461-488.Table

1—

The

Impact

Anti-

Takeover

Legislationon

CEO

Pay:

The

Role

ofLarge

Shareholders"

DependentVariable: LogofTotal

CEO

Compensation(1) (2)

Large

Shareholder?Yes

No

Anti-Takeover

Law

Adopted .026 .075" (.040) (.031) Adjusted R- .633 .768Sample Size 2281 2268

"Notes:

1. "Large Shareholder" is a

dummy

variable thatequals 1 ("Yes") ifthe firm hasa strictly positivenumberofblocks of atleast fivepercent ofcommon

sharesinthebase year(1984), whether theblock holder isor is not adirector. Blocks ofat least five percent that are owned byCEOs

areexcluded.2. "Anti-TakeoverLawAdopted" isa

dummy

variablethatequals 1afterthe adoptionofan anti-takeoverlaw (BusinessCombinationStatute) bythe state the firmisincorporatedin. 3. Each regression includes as controls yearfixed effects, firm fixed effects, a quadratric inCEO

age, a quadraticinCEO

tenure, thelogarithm oftotal assets and the logarithm of totalemployment.4. '* denotessignificanceat the5%.

Table

2—

The

Impact

ofAnti-Takeover

Legislationon

Pay

forPerformance:

The

Role

ofLarge

Shareholders"

Dependent Vaxiable: LogTotaJ

CEO

Compensation(1) (2)

Large

Shareholder?Yes

No

Anti-Takeover

Law

Adopted .017 .085'" (.040) (.030) Anti-TakeoverLaw

Adopted* 1.126** .316Ace. RateofReturn (.582) (.584)

Ace. RateofReturn 2.352** 2.533***

(1.116) (1.08)

Adjustedi?^ .641 .782

SampleSize 2281 2268

"Notes:

1. "Large Shareholder" isdefined asinTable 1.

2. "Anti-TakeoverLawAdopted" isdefined as inTable 1.

3. AccountingRateofReturnistheratioofNet IncomeoverTotalAssets. Ithasbeendemeaned.

4. Eachregression includes as controls year fixed effects, accounting rate of return interacted with year fixed effects, firm fixed effects, aquadratric in

CEO

age, a quadratic inCEO

tenure, thelogarithm oftotal assets andthelogarithmoftotalemployment.5. '" denotessignificance at the 5%;'*" at the 1%.

Table

3—

The

Impact

ofRisk

on

CEO

Pay:

The

Role

of

Large

Shareholders"

Dependent Variable: Log of Total

CEO

CompensationLarge Shareholdei (1) •?

Yes

(2)No

Performance.003—

(.000) .001-— (.000) Performance*CDF

ofVariance -.004—* (.001) .000 (.001)CDF

ofVariance -.07 (.06) -.17'" (.05) SampleSize 2301 2025 "Notes:1. "Large Shareholder" isdefined asinTable1.

2. "Performance" isdefined as the realgrowthrate ofshareholderwealth (includingdividend payments) and ismeasuredinpercentagepoints.

3. Eachregressionincludes as controlsyearfixedeffects,firm fixedeffects,a quadraticin

CEO

ageandaquadraticin

CEO

tenure.4. *"* denotessignificanceat the1%;'*" atthe .1%.