Deregulation in Japanese Gas Industries

by Masayuki Inoue

MASSACHUSETIS INSTITUTE

OF TFlO!NILOGY

SEP 0

5

1996

MASAYUKI INOUE Visiting Researcher,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research FEBRUARY ,1994

DEREGULA TI ON IN JA.PA.NESE GAS ZNDLUS TR IE'

- SIGNIFICANCE AND PROBLEMS OF GAS RATE DEREGULATION

CUSTOCERS--a.

P

- CONTrATS

-1. Introduction

2. The environmental charges surrounding natural gas in Japan (1)Current situation of primary energy supply

(2)Changing role of natural gas in energy policy

(3)The role of gas utilities to expand natural gas use 3. Deregulation trend in Japan

(1)Background of public utility regulation (2)Economic regulation and social regulation 4. Deregulation in gas utility industries

(1)Deregulation subject at issue

(2)Rate deregulation for industrial customers (a)Current gas rate structure

(b)Major background of rate deregulation

(c)Major advantages to deregulate gas rate for industrial customers (d)Significance of rate deregulation

(3)Noted point about rate deregulation

5. Deregulation in U.S. natural gas industry

(1)Regulatory structure and brief history of deregulation (2)Transition of rate deregulation

(3)Competitive rate-making in resale rate (4)Current situation of cross subsidization

(5)Major impacts on natural gas market by deregulation

- FIGURES AND

TABLES---

FIGURES

-FIGURE 1. COMPOSITION OF PRIMARY ENERGY SUPPLY IN JAPAN

FIGURE 2. TRANSITION OF PRIMARY ENERGY SUPPLY (INDEX: 1973=100)

FIGURE 3. SIGNIFICANCE OF NATURAL GAS IN JAPANESE ENERGY POLICY

FIGURE 4. PRODUCTION OF CITY GAS BY RESOURCE FUEL (PERCENTAGE)

FIGURE 5. SALES QUANTITIES BY CLASS OF SERVICE (PERCENTAGE)

FIGURE 6-1. TRANSITION OF SEASONAL LOAD CURVE IN "OSAKA GAS" FIGURE 6-2. TRANSITION OF DAILY LOAD CURVE IN "OSAKA GAS"

FIGURE 7-1. TRANSITION OF SEASONAL LOAD FACTOR IN "OSAKA GAS"

FIGURE 7-2. TRANSITION OF DAILY LOAD FACTOR IN "OSAKA GAS"

FIGURE 8. THE REDUCTION OF THE AVERAGE COST

FIGURE 9. GAS UTILITY INDUSTRY TOTAL SALES AND TRANSPORTATION VOLUMES

IN U.S.

FIGURE 10. TRANSACTION PATHS FOR NATURAL GAS PURCHASES

FIGURE 11. GAS UTILITY INDUSTRY AVERAGE PRICES BY CLASS OF SERVICE

FIGURE 12. REVENUE SHARE BY CLASS OF SERVICE IN GAS UTILITY INDUSTRIES

- TABLES

-TABLE 1-1. COMPOSITION OF PRIMARY ENERGU SUPPLY IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

TABLE 1-2. ENERGY DEPENDENCE ON IMPORT IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

TABLE 2. ANNUAL GROWTH RATE OF PRIMARY ENERGY SUPPLY IN JAPAN

TABLE 3. TRANSITION OF NATURAL GAS POSITION IN JAPANESE ENERGY POLICY

TABLE 4-1. THE NUMBER OF GENERAL GAS SUPPLY INDUSTRIES

BY CAPITAL AMOUNT AND NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES

TABLE 4-2. THE NUMBER OF GENERAL GAS SUPPLY INDUSTRIES

BY NUMBER OF CUSTOMERS

TABLE 5. THE COMPARISON OF LARGE GAS COMPANIES BETWEEN U.S. AND JAPAN

TABLE 6. TRANSITION OF GAS RATE SYSTEM IN JAPAN

TABLE 7. OUTLINE OF LOAD ADJUSTMENT CONTRACT SYSTEM

TABLE 8. MAJOR TRANSITION OF DEREGULATION POLICIES IN U.S. NATURAL

GAS INDUSTRIES

TABLE 9. MAJOR CHANGE IN INTERSTATE PIPELINE RATE DESIGN

TABLE 10. CUSTOMER REQUIREMENT BY END-USER SECTOR

TABLE 11. REVENUE REQUIREMENT BY RATE CLASS IN "BOSTON GAS"

TABLE 12. CUSTOMER CLASS REVENUE REALLOCATION IN "PROVGAS"

1. Introduction

In recent years , the circumstances surrounding Japanese city gas industries have been changing drastically. On one hand , as energy suppliers, natural gas, which has become major fuel resource for city gas, has obtained a more important place in energy policy. On the other hand, as public utilities, a new theory of economics and the economic reform process are requesting new regulatory framework instead of traditional one. Under such recognition, this study has three major purposes. The first purpose is to consider the significance of city gas deregulation in the context of drastic change in energy policy and in public utility regulation. The second is to discuss the expected advantages and noted point of rate deregulation for large industrial customers. The third purpose is to think about the implications from the

U.S. experience of deregulation in natural gas industry since 1970's.

Section 2. reviews the transition of Japanese energy supply structure and energy policy, focusing on LNG (liquefied natural gas). Section 3. deals with basic deregulation trend and its background in Japan. Section 4. focuses on rate deregulation for large industrial customers among some deregulation subjects. It also studies the current rate structure, background and expected advantages of rate deregulation, and noted point to prevent its possible disadvantage. Section 5. briefly

reviews the history of deregulation in the U.S. natural gas industries. Then, it extends to current situation of competitive rate-making and the major impacts on natural gas market by deregulation process. Section 6. deals with future problems for Japanese gas industries to struggle with.

It also attempts to mention some implications from U.S. the experience.

2. The environmental charges surrounding natural gas in Japan

(1)Current situation of primary energy supply

First of all, we will begin by considering the past trend of primary energy supply in Japan. FIGURE 1 shows that the composition of primary energy supply in Japan changed drastically after oil crisis I .

The oil dependence rate, which reached 77.4% in 1973, has declined to

56.7% in 1991, mainly because energy policy has converted to promote

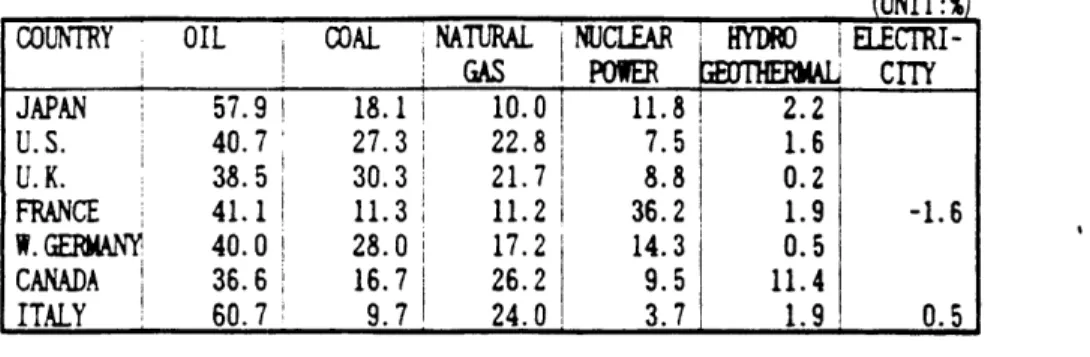

introduction of alternative fuels to oil. Compared to other developed countries, however, Japan is still much more dependent on oil,especially from the Middle East area and has a frail energy structure(TABLE 1-1,1-2).

FIGURE 1.

COMPOSITION OF PRIMARY ENERGY SUPPLY IN JAPAN

1955 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 89 91

FISCAL YEAR

i OIL D] COAL El NATURAL GAS E3 HTDRO D NUCLEAR [I OTHER (SOURCE)MITI.'GENERAL ENERGY STATISTICS'

TABLE 1-1. COMPOSITION OF PRIMARY ENERGY SUPPLY IN DEELOPED COUNTRIES(1989) (UNIT:%) COUNTRY OIL COAL NATURAL NUCLEAR YDRO

ELECTRI-GAS i POWER OTHEMAL CITY

JAPAN

57.9

18.1

10.0

11.8

i

2.2

U.S. 40.7 27.3i 22.8 7.5 1.6 U.K. 38.5 30.3 21.7 8.8 0.2 FRANCE 41.11 11.3 11.2 36.2 1.9 -1.6 W. GERMANY 40.0 28.0i 17.2 14.3 0.5 CANADA 36.6 16.7 26.2 9.5 11.4 ITALY 60.7 9.7 24.0 3.7 1.9 0.5 (SOUECE)OECD.' ENERGY BALANCE(1980-1989)'(NUTE)The figure '-1.6'.' 0.5' in electricity means export and iport.respectively.

TABLE 1-2. NERGY DEPNDENECE ON IMPORT IN DEVELODD MUNTRIES(1989) TOTAL DEPEDCE DEPEDDENCE DEPEDECE COUNTRY ENRGY ON OIL ON IWMORT ON STRAIT

OF IDFS JAPAN 83.9 58.2 99.7 61.7 U.S. 14.4 39.7 43.9 21.7 U.K. 2.3 39.0 -14.7 20.2 FRANCE 52.6 40.3 96.1 32.2 W. AN53.2 40.9 95.7 11.5

Meanwhile, natural gas has continuously increased its share in primary energy supply. In 1989 it reached to 10.0% and came up to 10.6%

in 1992. Though domestic natural gas , which exists mainly in Niigata

Prefecture, has long been used, it's very little in volume. It's not until 1969 that Japan started to introduce natural gas in earnest when Tokyo Electric Power Company and Tokyo Gas imported LNG from Alaska. At present approximately 95% of the total domestic demand for natural gas

is provided by LNG import. Therefore, the history of natural gas use as

one of the major energy resource is relatively shorter than other fuels

such as oil or coal. After oil crisis I , Japanese government has

introduced some promotional measures to reduce oil dependence and increase new energy resources. FIGURE 2, which was drawn as an index

assuming 1973=100, shows nuclear power and natural gas has increased

outstandingly. Furthermore, TABLE 2 indicates that natural gas has increased most rapidly among all energy resources after 1986. According to the Long-Term Forecast of Energy Demand announced in 1990 by Ministry

of International Trade and Industry (MITI), it is forecasted that

natural gas will have 10.9%, 12.0% share of total primary energy in

2000, 2010 , respectively.

FIGURE 2.

TRANSITION OF PRIMARY INERGY SUPPLY

(INDEX: 1973:100) 2.000 2.500 1.500 . /, 1.500 1.000 .1...- 2,000 ..0. .. ... 0 65 67 S9 71 73 75 77 79 Il 83 IS 7 Is 91

OIL CL AouaI s i m o aN iun Omn

(3TA CI)I.TG W.C PAATE FNW SU NISTIC

TABLE 2. ANNUAL GIE RATE OF PRIMARY ErY SUPPLY IN JAPAN

(SOURCE) Ministry of International Trade and Ind&rtry (MITI).

(2)Changing role of natural gas in energy policy

Next, past energy policy in Japan will be reviewed focusing on natural gas. The era before oil crisis I , can be classified into three periods. First period is 1945-51, when Japan was pursuing economic

recovery from the devastation of W.W.U . under priority production

system concentrating on the coal industry. The second period is 1952-61, when Japanese economy made steady growth under rationalization of coal industry and expanding oil use as major energy resource. The third is

1962-73, when Japan realized high economic growth. Energy policy at the

third period mainly aimed at stable and cheap oil supply corresponding to rapid increase of energy demand. Afterward, it was focused on the countermeasures of energy emergency and conservation during 1973-78, introduction of alternative energy for oil, best mixture of energy after

oil crisis II . As described above, major purposes of energy policy has

shifted very closely linked with economic growth phase.

Concerning natural gas, though its abundant reserves and

cleanliness have been highly regarded since LNG's introduction, its position in energy policy has remained low because of the contract rigidity and the price linkage with crude oil. As natural gas use expands, however, it has obtained more important position in energy policy. According to FIGURE 3, situation changes surrounding natural gas can be summarized as following three points. First, natural gas has been valued much more highly recently as a clean energy for global environmental problems including C02, instead of local pollution such as

NOX, SOX. Second, the utilizable area for natural gas has spread due to technological progress such as fuel cell and cogeneration. In addition to that, natural gas is expected to contribute easing tight supply-demand situation in electricity market through decentralized electric sites. Third, The Gulf War made us realize again strongly the necessity to reduce the dependence on Middle-East area. Though some new LNG

projects started in Middle-East area recently,there still exists

potential anxieties in the area. Japan's LNG import is now mainly

dependent on other areas; Indonesia 47.1%, Malaysia 18.5%, Brunei 13.9%, Austrailia 10.8% in 1991. Under these circumstances, the Committee for

Gas Fundamental Issues, formed under Advisory- Committee for

Energy,finally placed natural gas as one of the major energy resource in energy policy instead of other alternatives to oil (TABLE 3, ENDNOTE 1).

FIGURE 3. SIGNIFICANCE OF 1L&TURAL GAS IN JAPANESE ERY POLICY

1.Necessit to expand natuml mas ue so far

Environmental •oblem under Reduction of SOX the high econmic ro.wth

Sthrouh city gas

Oil crisis II -1nt Introduction of

alternative fuel for oil I

2. Necessity to exand natural ms use under the new ery enviroiment

TABLE 3. TRANSITION OF NATURAL GAS POSmNTI IN JAPANe S OGY POLICY

REPORT YEAR DECI iON ELA7 10 NATURAL GAS

Advisory Camittee for Energ(ACE) .Report 1967. 2 It' a ia'rtant to port dmstic natural s exploitation in t atof local econic develomnt.

It's i rtnt to introduce LNG i poitively.

ACE. Report

1

975. 8 Nxtualm am be higbly valued t retrain air pollution. 'Choice for stable supply diversit uer rwmourc.0to disperse mto w up ply are.SIt' a•rt to introduce U •t iwort ositively

ACE. Meetir~ for F udmental Ims. I977. 8 -Nat s am be hithly valed in t o t reserve Interi Report Ivariation of reave ram.•nvwirmmtal clealines.

ACE. Subcomittee for Suppl@y-Damd lames. 983. 8 -Naural a am cm be hidly valued in tarm o•upply stability

'Long trm perspective for supply & drd 983. 11 •a contol of cobution.u nvirw ta clmlinm . ' Revised lon-ter pmspective' 1987.10 It' a pproariate a rource fir city es ad power

am!eratim n in area,

ACE. Report 1990. 6 * Nstural cm a be hiahly valued in trm o cmatively SChallenge to no global ensyg t ' hi~u supply stability.2lowa r C2 • imi ni in fowil fuel.

ACE.Subomiitte for Urb a Enw . 992. 5 It es cm u to a ra bn atural s should be intrd d

Comitte fotar Fndenta Gas ~ mm. strIgly.

Intrim R ort Naturl abould be placd a one of the ~ mar ame•y

in Janebseuiyv olicy.

(SOURCE) Reports by Advisory Comittee for Ene

rwoutmity TA

Lnwomice ruivxw gm

w~w-Aa nstwrm] mpuL(3)The role of gas utilities to expand natural gas use

It is city gas industry which should have an important role to

expand natural gas supply to customers. Japanese gas industries can be classified into three kinds; general gas supply industries, community

gas supply industries, liquefied petroleum gas industries (ENDNOTE 2).

Among them , general gas industries mean so called "city gas

industries". The number of general gas supply industry is 246 in 1993. As TABLE 4-1 and 4-2 shows, they vary in scale very much in terms of capital amount, the number of customers and employees. The biggest 4 gas

companies Tokyo Gas, Osaka Gas, Toho Gas, Saibu Gas, whose franchise are

populated urban areas , containing 70% of the customers and 78% of

sales. TABLE 5 is comparing the scale between the U.S. LDCs and Japanese

city gas utilities.

TABLE 4-1. THE ?n R OF GNERAL GAS SUPPLY INDIThIES BY CAPITAL AWXIN AND NL~ER OF EIYEES (1992)

Nuer of employees -10 11- 61- I01-- 1 Total 50 100 300

:apital namunt ( l)

- 30 Killion 6 14 1 - - 21

30 - 50 million 6 26 3 35 50 --100 Killion 3 401 8 4 - 55

100 milliorr- 1 billion - 22 17 i II1 3 53

1 billiar - - - 12

Private Owned Total 13 102 29 I16 I 14 174

Public Ow[ed Total 30 32 7! 21 I 72

To ta 1 43 134 36i 18i 15 246 (SOURCE) JAPAN GAS ASSOCIATION. 'HANDs ON TIE GAS B• •ESS

TABLE 4-2. THE N1 M R OF (EERAL GAS SUPPLY

Il•IYIES BY NAB OF CUSZ S (1992) Omiship Privateily Publicly Total

Ownd Owned No. of cautmrs -1.000 2 1 3 1.001-2. 000 i 11 6 17 2.001-3. 000 19 i 12 31 3.001-4. 000 11 8 19 4.001-5.000 17 5 22 5.001-10.000 24 18 42 10.001--50.000 64 18 82 50.001-~100,000 8 3 11 100. 001-300.000 11 1 12 300.001~.5000 0 2 2 500.001.- 5 '- 5 Total 174 72 246

(U0 ) JAPAN GAS ASSOClATION

'BAM00 ON EW GAS ISlESS" TABLE 5. COFARISON OF LARGE GAS CDWANIES WTIEN U.S. AM JAPAN

NMberof Opfe19 pI raing GoSala outry Nam of tbhe Ca Y Ctome RIemI IO 1 Volme

(thousn (thoupmr 3)(thbom•r s)d M

SSoutbern California G 4.649 2.930.306 1. 333 406.621

.Pacific Gm Electric 3.500 2.951.442 304.597 651.569 U. S :Arkla Inc. 2.676 1.771.600 19. 100 402. 000

*Consolidated Ga 1.738 2.607.000 230.100 273.300

Distribution Co.

*"1MO0 GAS CO. 7.677. 6.309.014 286.290 264.375

JAPAN :OSAKA GAS CO. 5.552 5.007.220 283.926 215.053 *;.'m GAS CO. 1.433 1.369.44 52.019 55.455

S

SAIe GAS CD. 982 700,200 20,633 ,45.726 (OTE) l. tie fre of U.S is fr 1991(CT).ad that of Je i tfor 192(FT).

2.0peratinl Reyvemn and Op•atin •l m are amnvrtd aman f IS a 1124.80. .averaw adrbn rte in 1992•( .

3. Japm aW mie a volm is alcp lted by 1 cubic Mtnu 42.3 cubic feet .amaing that I cabic foot a 1.031 BI

(SOU 'RE'BR • S DI"ECm Y 1992-93 .WMRIE AM•ICA AD IlMIISI TIOL.GAS OI•ANIES

FIGURE 4.

PRODUCTION OF CITY GAS BY RESOURCE FUEL

(PERCENTAGE) iAl IUU 80 60 40 20 A I00 80 60 40 20 0 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1991 FISCAL YEAR

9 LNG.NG

0

COAL 0OIL O- OTHER(SOURCE)JAPAN GAS ASSOCIATION.

'HANDBOOK ON THE GAS BUSINESS'

Japanese city gas industries used coal and petroleum as a major materials to manufacture gas in 1950's and 1960's, respectively. As big gas companies, however, introduced LNG and developed a natural gas conversion since 1970's, natural gas shares including domestic one reached 77.1% of all industries and about 90% in big companies in 1991

(FIGURE 4). Of the whole Japanese LNG imports, electric utilities have

an overwhelming influence, occupying 73.7% in 1991. The share of gas utilities, however, has risen from 20.0% to 24.8% in 1991. Comparing the annual consumption growth rate during 1980-85, 86-91, they are 11.5%,

8.5% respectively for city gas utilities, in excess of 10.5%, 5.3% for

electric utilities. Under such a situation, Committee for Gas

Fundamental Issues p•inted out "City gas industries should play a major role to deliver natural gas to customers ".

3. Deregulation trend in Japan

(1)Background of public utility regulation

As we saw in Section 2, the obstacles to promote natural gas introduction are to stabilize natural gas price and to reduce business risk accompanied by long-term upstream contracts. On the domestic side, current regulatory framework should be reconsidered.

Public regulation, which is generally defined as "government intervention in national and industrial activity to achieve specific policy goals", sometimes includes macro-economic policy such as monetary

and fiscal policy in its wider definition. In the more narrow

definition, it means "restriction by government on industrial activity to achieve policy goals which can not be achieved by market mechanism,

by way of licence permit, authorization or informal administrative

guidance." Therefore, public regulation aims at achieving fairness and

efficiency , which are sometimes conflicting with each other, by

government intervention .

As to the public utilities such as electric, gas and water utilities, they have been regulated because their service have been

regarded as typically public, necessary and natural monopolies.

Government has allowed the monopolies in their franchise to pursue

economic efficiency on the one hand, having regulated strictly new

entry and pricing on the other hand. These regulatory policies have been generally successful because they have prevented destructive competition

and overlap investment and achieved well-balanced "fairness" and

"efficiency" to some degree, at least during the period when Japan has tried to catch up with the developed countries. In some fields, however, such as energy market for large industrial customers or power generating market etc., the basic ground like natural monopoly, economies of scale have been changing.

Therefore, it is the time to reconsider what should be left for market mechanism and what should be regulated by public authority. Some

of the reports by The Administrative Reform Council ("Rincho",

"Gyokakushin") have already shown such recognition related to

deregulation since 1983. In Dec.1988, Rincho reported that "Social and

economic circumstances have so greatly changed that traditional

regulatory policies and their role should be reconsidered". As to energy industries, it also pointed out "Energy demand is being diversified with

the rapid change of national life and industrial activity by

technological progress. Electric and gas rate structure should be

examined to make them more flexible , considering supply security and

equality among customers."

(2)Economic regulation and social regulation

It is necessary to classify current regulations according to their purposes to examine what should be deregulated. In general, they

Economic regulations aim to supplement market failure to raise economic efficiency. More concretely, they mean entry and price regulations in natural monopolistic industries. Social regulations are implemented to secure consumer safety , social equality, and to protect socially weak

people such as low income households. However , as the Gas Utility

Industry Law mainly aims at three goals, protecting public interest,

developing the industry soundly,securing consumer safety including

environmental pollution, actual regulatory policies are so complicated

by economic and social regulations that deregulation can not be applied

to them all uniformly. As to social regulations, they should be deregulated very prudently considering social goals. Some of them such as environmental regulation or product liability issues should be even

strengthened, far from being deregulated. What is currently strongly

requested in Japan is to reconsider economic regulations which has been implemented under the assumption of past technological conditions and market circumstances.

The new Coalition Government, started in July 1993, replacing the Liberal Democratic Party which had been in power 38 years since

1955, seems set to promote deregulation policies strongly. They are

expected to stimulate Japanese economy, which is suffering from probably

the longest recession after W.W.II . Normally , however, it takes time

for the result of deregulation to penetrate into the market. Therefore, they should be interpreted as the first step of the economic structural reform in the long run, not as short-term economic stimulus policy. The positive attitude of new Coalition Government to push deregulation policies can be significant not only to find new deregulation areas, but also to put them into practice, they had previously been only considered but not have been carried out.

Economic Reform Advisory Group (consultation committee of Prime Minister), which was established in October 1993 , is expected to make a long-term vision of the future Japanese economy. They suggested in the interim report that economic regulations should be basically eased. As

to the electric and gas industries , they suggested that current

regulation should be eased to give utilities more incentives by introducing more competition principle to gain consumer benefit (ENDNOTE

3).

Thus, it is none other than dynamically changing era that is demanding deregulation not only in electric and gas utilities, but also in whole Japanese economic system.

4. Deregulation in gas utility industries

(1)Deregulation subject at issue

Currently, the deregulation subjects at issue in city gas

industries are constituted of mainly , ( gas rate reform for large

industrial customers,

)franchise

reconsideration of city gasindustries, Z mutual usage of natural gas pipelines. Franchise expansion of city gas has not been discussed earnestly in order to protect small and medium companies in local areas and to avoid difficulties in settling the territory negotiation with LPG industries. Mutual usage of natural gas pipelines means releasing surplus capacity of pipeline and introducing contract transportation. This is so common in the U.S. already that 84% of the interstate pipeline is occupied by contract-transported gas. From now on, contract-transportation will be a key issue because natural gas demand in industrial sector is expected to grow rapidly and local small-sized and medium-sized gas companies will

receive more natural gas through pipelines from large gas companies.

By the way, deregulation is being considered in Electric

industries as well, and reconsideration of electricity selling system has an impact on city gas industries. At present with few exceptions, decentralized power generators or cogenerators in the factories are allowed to sell their surplus electricity only after their own consumption The Committee for Fundamental Policy Issues under the Advisory Committee for Energy has just suggested in the interim report Dec.1993, to promote electricity purchase by utilities through entry deregulation. For city gas companies, entry deregulation in power generating market can be a positive opportunity to expand natural gas use. However, there still exists many problems to solve such as how to

secure supply stability, how to set the price for surplus power, and how to impose generating responsibility for self generators or cogenerators. The following description is focused on easing rate regulation

for industrial gas customers, which is a typical and traditional

economic regulation. It also covers to its background, expected benefits, significance and points which should be noted.

(2)Rate deregulation for industrial customers (a)Current gas rate structure

Currently, city gas rates are regulated by MITI , which

supervises gas utilities through the Gas Utility Industry Law. The principles used to set gas rate are based on "cost-based-principle ",

"fair-return-principle", and "equality-principle among customers". Under such regulatory framework, city gas rate system has transformed from flat volumetric rate, declining block rate, single two-part rate,

plural two- part-rate (TABLE 6).

TABLE 6. TRANSITION OF GAS RATE SYSTEM IN JAPAN

and

RATE SYSIM

G APH

CHARACIERISTICS

Scharge

VoU11TRIC FLAT RATE

BLOCK RATE WITH

MINI chaIARGErge

mini"uschar ge

(Advantage)

* easy and simple to calculate gas rate under the uniform demnd structure

(Disadvantage)

* not reflecting load responsibility.

- difficult to encourage consuers to conserve enertg

usage volume

charge(

)e5at.vdA

usage volume

charge

SINGLE TID PART RATE minimum charge

* ainimu charge secures to collect demnd cost. * closer to arginal cost pricing .which is roved

most efficient in economic theory. (Disadvantage)

* irrationale during minim. usage obliption * The gap between declining long-temm argina cost

and actual rate level is expanding

(Advantage)

* imroves the c rrespondence between cost md rate. (Disadvantage)

* not reflecting cost differentials caused by different uage conditions

charge (Antar)

* improves the correspodence btween cost and rate. in single two-part rate.

(Disevaitage)

PLURAL 110 PARK RATE * • lacks catamer' incentives to conlerve energy. Sbecame rate table is applied after the fact. , , • mspondnmce between c mdity chbarge and demnd mini chare charge is distarted.

usage volume (SOURCE) Deryoku Shinpoha." Public Rate in Japn' etc.

At present, large city gas companies are adopting two sorts of rate menus ; general rate and load adjustment contract rate. General rate is defined as the rate when utilities supply gas responding to general public demand following to the authorization of Article 17 in the Gas Utility Industry Law. Gas rates are mainly classified into declining block rate system and part rate system. The single two-part-rat system was introduced in 1980 to improve the problems of

declining block rate. The first problem was that it lacks incentives to

conserve energy use during minimum charge. In addition to that, the relation between rate and cost was unclear. However, single two-part-rate system still had problems ; (1 expanding two-part-rates and declining

long-term marginal cost as a result of natural gas conversion.

®

notreflecting cost difference because the same demand charge and commodity charge are applied to different customer groups regardless of usage amount. Then finally, plural two-part-rate system was adopted by big gas utilities in 1990. Thus, past transition of gas rate system has been aiming at (A)improving the relation between cost and price, (B)raising

daily and seasonal load factor, and (C)dealing with increasing

competition in energy market.

Meanwhile, the load adjustment contract rate is defined as the rate which is authorized by Minister of International Trade and Industry

only when certain criteria such as demand scale and load factor are

satisfied. Therefore, it is a rate system which is most reflecting the

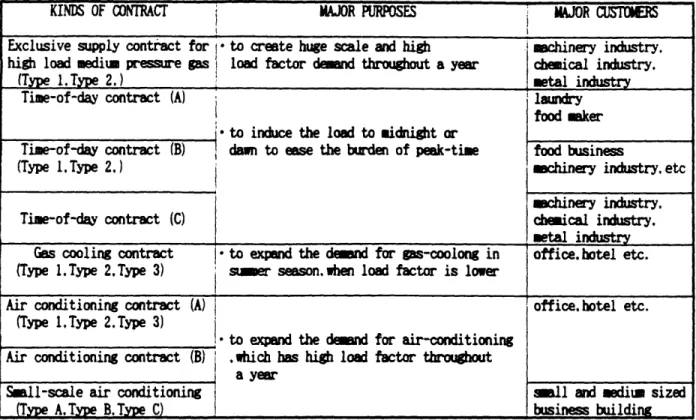

goals of above (A),(B),(C) (TABLE 7). This rate system was first

introduced in 1979 based on the report by the Advisory Committee for Energy to create large-scale and load adjustable demand as Industrial

LNG Contract System. As a result, natural gas demand from industrial

customers, especially Industrial LNG Contract System , which consumed

over 4 million cubic meter per year , has increased rapidly mainly

because it has become possible to set a price competitive with other fuels. After its introduction, the criteria of usage scale was lowered to 1 million cubic meter. Application was also widened to eight rate menus. Still, however, pricing has to be authorized case by case by the Minister according to provision, Article 20 in Gas Utility Industry Law, "General gas utilities is prohibited to supply gas other than supply rule authorized in Article 17, but this rule is not applied in special case where Minister approves it." So, load adjustment contract rate is

still an exceptional status in the rate structure. Furthermore, 4 of eight menus are comprehensively authorized, but the rest of them have to be done case by case. as to exclusive supply contract for high load

TABLE 7. OLTINE OF LDAD JUS•ENf CONTRACT SYSTEM

medium pressure contract, the authorized period is limited to just one

year , so even if renewal is practically automatic, the whole

authorization process is repeated every year.

Rate deregulation for large industrial customers, which is most hotly debated, means reforming the process from strict authorization to ex post facto report. If this deregulation policy would be implemented, supply conditions including gas rates, would be decided by negotiation

between gas companies and customers. In that sense, rate deregulation

can be interpreted as more flexible application of load adjustment contract. In addition to the rate reform, reconsideration of franchise, which allows gas supply beyond current supply area limited only to large

industrial customers, is also being debated.

KINDS OF CONTRACT i MAJOR PURMOSES MAJOR CUSTIMERS

Exclusive supply contract for I* to create huge scale and high imachinery industry. high load medium pressure gas load factor demnd throughout a year chtmical industry.

(Type 1. Type 2.) metal industry

Time-of-day contract (A) laundry

food maker _* to induce the load to midnight or

Time-of-day contract (B) dawn to ease the burden of peak-time food business

(Type .Type 2.) machinery industry. etc

achinery industry. Time-of-day contract (C) chemical industry,

metal industry Gas cooling contract ) to expand the demnd for gas-coolong in office. hotel etc. (Type 1.Type 2.Type 3) sanmer season. when load factor is lower

Air conditioning contract (A) office.hotel etc. (Type lTy*pe 2.Type 3)to expand the d nd for air-conditioning

Air conditioning contract (B) .which has high load factor throughout

a year

Small-scale air conditioning I ll and medium sized

(b)Major background of rate deregulation

A drastic change around gas utilities lies behind such a

deregulation trend as an important background. Especially, in big gas utilities, we can point out the big changes in both supply and demand side. In supply side, supply capacity of the gas pipelines has increased as a result that natural gas conversion was completed. In addition to that, supply has transformed from a local area operation to a wider one, because supply network of the pipelines has been well developed. In demand side, while annual growth rate for residential and commercial demand were 3.6% and 4.6% in 1980's respectively, in industrial sector it was 9.8%, more than the other. The proportion of industrial demand in total gas sales amount has also increased rapidly, which reached to

28.5% in 1991 (FIGURE 5). These changes are mainly because natural gas

has been highly valued as an industrial energy resource which has high energy efficiency and environmentally friendly aspects. Expanded area of utilization has also contributed to demand growth. Furthermore,

increasing competition in energy market among gas, electricity , oil has expanded the alternative choices to customers. Customers' diversified needs demanded more competition.

FIGURE 5.

SALES QUANTITIES BY CLASS OF SERVICE (PERCENTAGE) 9:^ 100 80 60 40 20 n 1965 70 75 80 85 90 91 FISCAL TEAR R

RESIDENTIAL 0 COUERCIAL E3 INDUSTRIAL

0

OTHER (SOURCE)JAPAN GAS ASSOCIATION.'HANDBOOK ON THE GAS BUSINESS'

IVV 80 60 40 20

n

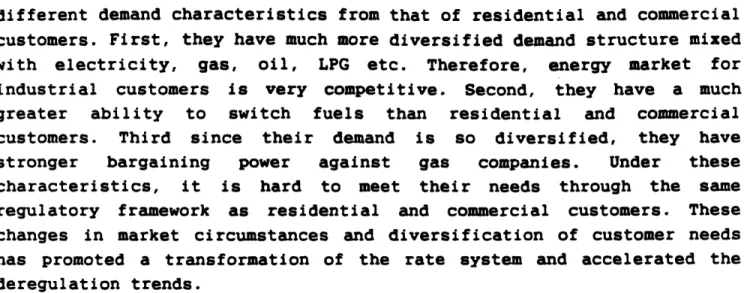

different demand characteristics from that of residential and commercial customers. First, they have much more diversified demand structure mixed with electricity, gas, oil, LPG etc. Therefore, energy market for industrial customers is very competitive. Second, they have a much

greater ability to switch fuels than residential and commercial

customers. Third since their demand is so diversified, they have

stronger bargaining power against gas companies. Under these

characteristics, it is hard to meet their needs through the same regulatory framework as residential and commercial customers. These changes in market circumstances and diversification of customer needs has promoted a transformation of the rate system and accelerated the deregulation trends.

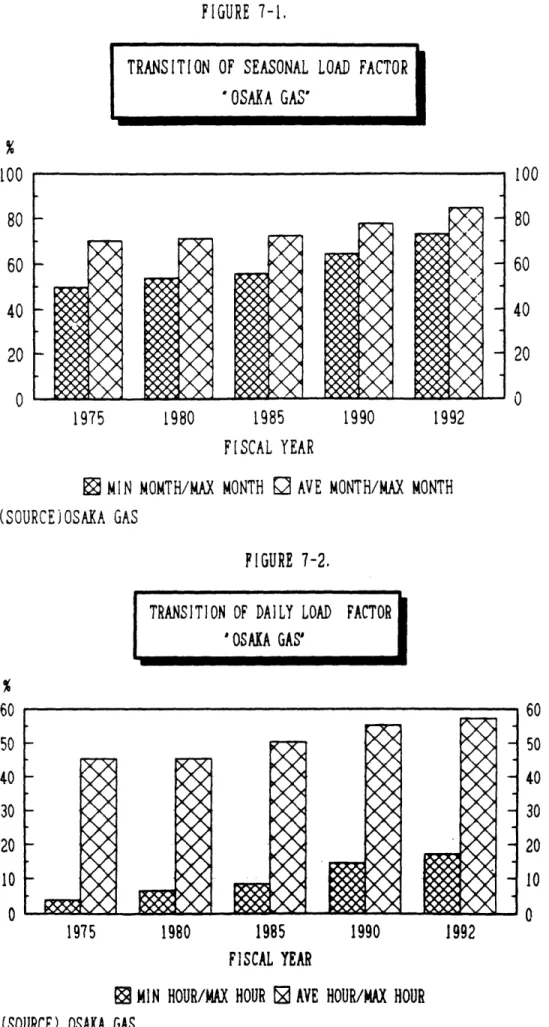

(c)Major advantages to deregulate gas rate for industrial customers Then, what kind of benefits can be expected as a result of rate deregulation for large industrial customers ? First, gas rate for large industrial customers can be lowered through the competition with other fuels. The second expected benefits is the improvement of the capacity utilization rate. Gas demand fluctuate very much seasonally and daily. FIGURE 6-1 and FIGURE 6-2, monthly and hourly sendout in OSAKA GAS, which is one of the big gas utility in Japan, show that gas demand in

summer season in 1970 used to drop less half than that in winter.

Similarly as to the hourly pattern, demand during midnight to dawn was less one tenth than that of evening. Expanding industrial customers in 1980's improve the capacity utilization rate and lower the average cost because their demand patterns are much more levelized throughout the year. According to FIGURE 7-1 and FIGURE 7-2, both seasonal and daily load factor (average consumption /maximum consumption(%)), which is one of the indicators of capacity utilization rate, has improved from 1970 to 1991 . At the same time, the ratio of off-peak-hour, off-peak-month

to peak-hour, peak-month have also improved . They rose especially in

late 1980's, because the economies of network scale began to penetrate into the market then. In addition to that, from the systematic aspect,

flexible application of load adjustment contract rate system

institutionally promoted to create the demand, which contributed a lot to improve load factor.

FIGURE 6-1. THOi•SANLD jB: NETER 065, 00 500, 000 400. 000 300. 000 20C. 000 100. 000 0, 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 NONTH 11 12 1 2 3

1975(FY) 1980 ) 1985F 1985(FY) 90(FY) 1992 FY)

0(SOURCE SAKA GAS

FIGURE 6-2.

THOUSANDS OF CUB]"C ETE

I, bUU 1, 400 1,200 1, 000 800 600 400 200

0

V 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 HOUR 2 3 4 5 6 71975(FY) 1980(FY) 1985(FY) 1990(FY) 1992(FY)

(SOURCE)OSAKA GAS

(NOTE)Above graphs are averases of the 10 largest sendout ;n each year.

.. ... . .. ... -.. -." -o 00. 000 500. 00 400. 01 C 300. 000 200. 000 100, 000 1.600 1, 400 1, 200 1, 000 800 600 400 200 0

FIGURE 7-1.

100

80

60

40

20

0

1975

1980

1985

1990

1992

FISCAL YEAR

M

MIN MOMTH/MAX MONTH

Q

AVE MONTH/MAX MONTH

(SOURCE)OSAKA GAS

FIGURE 7-2.

1975

1980

1985

1990

1992

FISCAL

YEAR

W9

MIN HOUR/MAX HOUR 2 AVE HOUR/WAX HOUR

(SOURCE) OSAKA GAS

100

80

60

40

20

0

Third, it's not only large industrial customers, but also

residential and small commercial customers who can benefit from the

rate deregulation from lowered average costs. Theoretically, the third point can be explained as follows. In FIGURE 8, when price is set based

on average cost, price would be Po and demand would be Xo0. At this

time, customers who can choose alternative cheaper fuels, would not demand gas. In case the price would be lowered to P. as a result of rate deregulation, new demand by large industrial customers, (X,-Xo), would be created. Accordingly total average cost would be lowered to P*. That

is; it is possible to lower the price for residential and small

commercial customers as well through raising allocation efficiency by setting the price for industrial customers closer to marginal cost. Besides, it's common to build a high-pressure or medium-pressure pipeline to meet increasing demand by large industrial customers. It would encourage formation of a gas pipeline network to increase supply

capability. This will secure supply stability for future demand. FIGURE 8. THE REDUCTION OF THE AVERAGE COST

P*

P1

'FMANn C~IIRVF

E COST CURVE

MARGINAL COST CURVE

..

Xo Xi

We can point out more benefits of deregulation. According to Uekusa [1991] (ENDNOTE 5), it can be generally expected a wider variety of rate menu, better quality of service through higher efficiency, wider choice for the customers through service diversification, reduction of the administration cost related to regulation. It is truly a big benefit to be able to provide wider rate menu and diversified service depending on supply conditions for customers because it is customer needs which is providing rate deregulation.

s

What we should note here is the importance of transfering benefits to customers. It's gas utilities which can benefit directly from improving capacity utilization rates or decreasing average costs. Deregulation policy should be considered as a great success when customers can benefit from lower rates, wider energy choices, and better quality of service.

(d)Significance of rate deregulation

As discussed above, the significance of rate deregulation for large industrial customers can be understood as follows. In terms of energy policy, rate deregulation means systematic improvement to expand natural gas use as we saw in Section 2. In terms of public regulation as we saw in Section 3, it means to reconsider traditional regulatory framework and to introduce a principle of competition in the public utility area even though it's just for large industrial customers at present. From the customers' standpoint, they can benefit from more flexible pricing and supply conditions, and expect lower prices. Moreover, in terms of the relation with other deregulation subjects, we can understand this as the beginning of an earnest deregulation process. It's very possible for other deregulation subjects to be promoted by rate deregulation, because franchise reconsideration, which may come next to rate reform, may require the introduction of common carriage and the expansion of natural gas use in decentralized power sites.

(3)Noted point about rate deregulation

Then, what is the point we should note in case of rate

deregulation ? The most likely problem is that in lowering rates for large industrial customers in the competitive energy market, gas companies may unfairly transfer their cost to small customers. In other words, it is feared that they may exclude competitors from the market by unfairly lowering the gas rate. As a result of it, gas rate for small customers may rise. Moreover, there is a certain gap in rate level between large customers and small customers even now. The disparity between them may be expanded. These likely disadvantages as a result of deregulation are against "equality-principle among customers" in the Gas

. Utility Industry Law. Some even point out it's also against Anti

Monopoly Law, which provides for fair competition. These anxieties are explained by the concept of cross-subsidization in economic theory. Cross-subsidization is defined as "the activity of enterprises which have plural demand sectors, to make up the deficit in one sector from

the surplus in profitable sector" (ENDNOTE 6). In case of gas rate deregulation, it means to transfer cost unfairly from large customers to small customers in order to be competitive and to beat the competitors in the market(ENDNOTE 7). To prevent unfair cross subsidization, it is necessary to examine if the rate for each customer class is fairly based

on cost. To that end, it is important to make a separate accounting for each customer class, but cost allocation to them can be arbitrary, because there are so many common facilities for residential, commercial, and industrial supplies.

Actually, it is reported that some industries such as petroleum and LPG industry are strongly opposing gas rate deregulation for large industrial customers, and requesting city gas utilities to prevent unfair cut-rate by disclosing each rate case in the debate in the Committee for Gas Policy Issues, which is considering desirable city gas supply system (ENDNOTE 8). It is also reported that some of them assert that gas utilities should be divided into different bodies by customer classes of service, because making a separate account is insufficient to prevent unfair cross subsidization.

Accordingly, regulatory authority will have a new regulatory mission to prevent unfair cross subsidization by supervising separate accounts. They are also supported to have new concerns to see the benefit or influence on small customers.

5.Deregulation in U.S. natural gas industry

(1)Regulatory structure and brief history of deregulation

Comparing the industrial structure and the circumstances between Japanese gas utilities and the U.S., it will be found that there are many differences between the two. First, there is abundant domestic

natural gas reserves in the U.S., but Japan is dependent on

approximately 95% on LNG import. Second, there is a big difference in

price advantage against oil. Historically, in the U.S. much of the

natural gas was collected as associated gas with oil exploitation, so natural gas price has been usually lower than oil price. On the other hand in Japan, LNG price is so closely linked with oil price that it's not really price competitive against oil basically. Third, we can point out the big differences in industrial structure. U.S. natural gas

industries are speciallized by three functions;production,

gasification, transportation and distribution are vertically integrated (ENDNOTE 9). In addition to them, there is also a big differences in supply infrastructure.

In the U.S., large gas wells were discovered in south-west area, mainly in Texas and Louisiana in 1930's. To connect these production areas and the North-east area, where demand had been rapidly increasing, interstate pipelines were built nationwide. In 1960's the current pipelines network was almost completed. It covered approximately 450 thousand kilometers. On the contrary in Japan, there doesn't exist

nationwide trunklines and whole length of the pipelines for

transportation is just 1300 kilometers long. As to the deregulation trend as well, the U.S. differs from that of Japan, because it started by wellhead price decontrol in the late 1970's and open-access in interstate pipelines followed. As to the rate deregulation, however, there's some similarities between the two. In the following, I would like to focus to see three points in the U.S. natural gas industries ;(l)brief sketch of regulatory structure and past deregulation policy, (2)deregulation trend in resale rate and some measures to prevent bad effect, (3)major changes and influences in the natural gas market.

Regulatory authorities of natural gas industries vary dependent on the stage from upstream to downstream. It is the Department of Energy (DOE) and The Economic Regulatory Administration (ERA) which are in charge of the export and import of natural gas. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC (ENDNOTE 10)) supervises production at the wellhead and interstate activities. It varies from state to state which

regulates intrastate pipelines and Local Distribution Companies

(LDCs);The department of Public Utilities (DPU) or Public Utility Commission (PUC) or Public Service Commission (PSC) etc. These dual regulatory structure, which means federal level and state level, is

characteristic of U.S. natural gas industries in administrative aspect.

TABLE 8 briefly summarizes the regulatory history of U.S. natural gas industries. FERC implemented Order 636 as a final rule to

complete a series of deregulation policies since late 1970's. The era before Order 636 can be divided into three periods. The first period was until 1978, when Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA) was implemented to solve the serious gas shortage problem. The second was so called "gas bubble era" since NGPA to mid 1980's. The third era was since mid 1980's to Order 636, when open-access was strongly pushed through Order 436, Order

TABLE 8. MAJOR TRANSITION OF DEREGULATION POLICIES IN U.S. NATURAL GAS INDUSTRIES

ACT, ORDER YEAR MAJOR CONETIES OF POLICIES MARKET CIRCUMSTANCE OR PURPOSES RESULT

NATURAL GAf1938.6 Construction. transportation and the rate of )interstate transaction increased.

ACT(NGA) interstate pipelines were regulated by Federal Zenacted to protect consumers

Power ComissionlFPC). from pipelines' exploitation.

PHILLIPS 1954.6 Regulartory coverage of FPC under NGA was extende Lawsuit was wide between Wisconsin 1well by well regulation didn' t work well.

DECISION to wellhead price control state and Phillips Petroleum over 2Area rate.national rate were developed.

wellhead price.

1978. 11 )natural gas was classified into 23 category. imed at solving supply shortage Ne exploitation was strongly developed.

NATURAL GAS high cost gas.old gas and new gas. in interstate natural gas market. Supply-deand situation was reversed to POLICY ACT )ellhead price control of high cost gas and Zaimed at mintaining natural gas gas bubble.

(NGPA) new gas were removed in Nov. 79. and Jan.85. price equivalent to oil.

(Control of old gas was also abolished in Jan.93.)

ORDER380 1984.5 Minimm commodity charge clause was abolished. )price surged due to deand decrease. tduced the advantage of pipeline companies

moinium comodity charge prevented against LDCs.conamers.

LDCs from procuring cheap gas. )piled up take or pay deficit in pipeline

cauqwnies.

ORDER436 i985. Il lopen access transportation )aimed at solving take or pay iauues. promted the functional chuge of

ORDER500 1987.8 Znon-discriminatory release )to respond expanded spot market. pipeline companies from sales to contract first-come first-served allocation principle )to secure flexibility of trasportation tram portation

Acontract demand adustment right by pushing comon carrTiage.

transportationrate was unbundled. to promote open access transportation )take or pay credit for producers ware obligated.

Ttake or pay cost can be passed on rate.

ga inventory charge was introduced.

ORDER636 1992.4 Dpipelines that offer fire and interruptible ffinal restructuring rule since 1978 Federal regulation gave a big impact on transportation service must unbundle services. Zto promte market competition maintaining state regulartory policies

pipelines that make bundled sales miust provide supply reliability

non-discriminsatory.non-notice transportation. (to widen the choices for purchasers f irm and interruptible service must be offered to levelize competition conditions amng

based on equality of service. sellers

)storage capacity of pipelines must be released. )receipt and Delivery point miet be flexibilized.

)SFY rate design mist be applied instead of WFV

for

interstate transportation service.

(SOURCE)PUBLIC UTILITY REPORIS.'THIE REGULATION OF PUBLIC UTILITIES'.

CATO INSTITUTE.' REGUILATION. WINIER 1993 -IHE NEW AGE OF NAlURAL GAS-'

The Natural Gas Act (NGA) started to regulate the interstate

pipeline business in 1938 and the 1954 Phillips Decision allowed the

federal government to control wellhead prices. As a result, the exploitation incentives were kept so low that market faced serious natural gas shortage in 1970's. After NGPA was implemented, the supply-demand situation in the market was reversed, entering into the gas bubble era. Though the gas bubble has been shrinking compared to the peak in 1985, it has been a basic feature through 1980's. Major goals of

the deregulation. policies in 1980's were how to deliver gas effectively and how to allocate risks related to natural gas transaction from wellhead to burnertip among producers, pipeline companies,LDCs and

consumers under gas bubble situation.

(2)Transition of rate deregulation

As described above, U.S. natural gas industries are specialzed by three functions;production, transportation and distribution. There are three kinds of gas prices according to each stage;wellhead price, city gate price and resale price. Wellhead prices had been under price-cap control of FPC or FERC since Phillips Decision in 1954. The control for high-cost gas and new gas, however, was abolished following NGPA in November 1979 and January 1985 respectively. Old gas as well was

released from regulation in January 1993 bu Natural Gas Wellhead

Decontrol Act of 1989. Transportation price had been regulated in terms

of consumer protection because interstate pipeline industries have been regarded as a typical natural monopolistic industries since NGA was formed. FERCethought their natural monopolistic feature as a big obstacle to make the market more effecient through competition. Then in mid 1980's, FERC pushed common carriage transportation through

non-discriminatory open access. As TABLE 9 shows, regulation on

transportation rate has changed about allocation of fixed cost and variable cost. At present, FERC adopted SFV (Straight Fixed Variable Cost) instead of MFV (Modified Fixed Variable cost) after Order 636.

As to resale price, flat rate was predominant until the beginning of this century, when natural gas was plentiful, cheap and transported short distances. Next in the 1920's, declining block rate, which promotes consumption, became popular as the natural gas industries began to face competition with electricity. Despite such transition in rate system, utility rate-making traditionally goes through same steps based on certain criteria as follows;(1)Determination of the acceptable level of costs to be applied to the rates, (2)Determination of a fair rate of

F[ABI 9. MAJOR CHANGE IN INIERSTATE PIPELINE RATE DESIGN Y.AR RATi DESIGN DEMAND CHARGE FIXED COST VALUABIE COST POI.ICY RATIONALE 1952 [tiAUAKfIC SEABOARD] ONE-PART DEMAND CHARGE

* 50% of fixed costs allocated

to deand charge

* 50% applied to commodity

charge

* Valuable costs allocated

totally to comodity charge.

(Later modified so that 100

of fixed production costs

were allocated to cAmmodity

chare.)

I)ltcb h cost. incurrence

with cost responsibility Enmsure just and reasonable

rates under the. NGA

1973 INITEHD]

ONE-PART DEMAND MCHARGE

* 25% of fixed costs allocated

to demnd charge

* 75% of fixed costs allocated

to demnd charge

* Valuable costs allocated to comodity charge.

)Conserve available gas

supplies

lMatch cost incurrence

with cost responsibility

)Ensure just and reasonable

rates under the NGA

1983

[(MODIFIED FIXED VALUABLE]

(MFV)

TWD-PART DEMAND CHAGE

50% of fixed costs (minus

the return on equity and related income taxes are

recovered through a

peak-day demad charge

* Valuable costs allocated

to coemodity charge.

In addition .the return on

equity and related taxes

are also recovered through the comodity chare.

1)Maximize pipeline throughput Enable gas to compete more effectively with alternatiw

fuels such as oil

.Ensure just and reasonable

rates under the NGA

1989A

[MWDIFIED FIXED VALUABLE

( fwrf 02 ARGE) ] (wV' )

ONE-PART DEMND ICHARGE

* All fixed costs except the

return on equity and related

income taxes are recovered

through a peak-dny demund charge

* Valuable costs allocated

to comodity charge. In addition .the return on

equity and related taxes

are also recovered through

the coedity dcharge.

DTramition period to open-access and the decontrol of

natural gs wellhead price

under the NGPA is over

ZDZ dcarge no longer needed

to soften the impact on

low load factor customers ol

the shift of fixed costs

from the commodity charge

to the demnd chdge

Enseure Just and reasonable

rates under the NGA

1992

tSZrIGfr FIXED VALUABLIE

(SFV)

ONE-PART DEMAOD IARGE

* All fixed costs are recovered

tUrough the peak-day dmnd

charge.This includes some

fixed costs such as return on

equity. related taxes. long-tera

debt which were previously recovered as a commdity chare

under MV

Valuable costs allocated

to caomdity charge.

DPrtmote competition at

the wellhead

)Facilitate creation of

national market for gas 3Promote nondistortionary

price signals

&Enoure just and reasonable

rates under the NGA

(NUIT) D2=ANNUAI. DEMAND IAR(;E

(SOURCE) DWPAIfhW•NT OF IFJINlGY/EJNERGY INFOIMATION AIMINISTRATION.' NA11URAL GAS 1992 -ISSUES AND TRENDS-' etc.

--d W I 1983---- ~ *

return on shareholder investment, (3)Allocation of costs to differ customer classes, (4)Development of rates from allocated costs and forecasted sales levels. In Massachusetts for example, DPU suggests several goals for utility rate;efficiency, simplicity, continuity, fairness and earning stability.

However, these traditional framework of resale rate regulation has faced competitive pressure from the drastic environmental change in the market. The collapse of the oil price in early 1980's pushed large industrial customers to shift from natural gas to alternative fuels, especially, oil. As a result, uniform regulatory system both small captive customers and large customers who can easily shift their fuel mix to alternatives had been unable to meet the new competitive market. These pressure required a competitive rate-making for large industrial customers. Furthermore, FERC propelled open access transportation so strongly that many of the large customers made contracts directly with producer, interstate pipelines companies (FIGURE 9). This also required LDCs to have more flexible and diversified rate-making to cope with competition.

(3)Competitive ratemaking in resale rate

Then, how was the competitive rate made concretely ? First, as TABLE 10 shows, customers are classified into three groups, residential, commercial, industrial according to demand characteristics, such as demand elasticity or distribution cost etc. Then, they are divided into core customers and non-core customers. Non-core customer are mainly constituted of large industrial customers and power generators. They usually have a capability to switch on short notice to alternative fuels, large scale demand per meter, and adjustable load factor. It is also a characteristics that they have a big bargaining power against LDCs. The basic concept of competitive rate-making is to subdivide the service and to set the gas rate according to each service variety. Particularly, non-core customers have energy needs so much more complex than core customers that the service for them are diversified into categories such as short-term contracts or long-term ones, firm

transportation or interruptible. Therefore, gas rates are also

diversified according to the service (ENDNOTE 11). From non-core

customers' standpoint, they can choose the combination of price and supply stability to meet their needs.

FIGURE 9.

GAS UTILITY INDUSTRY TOTAL SALES

AND TRANSPORTATION VOLUMES

ThILLION OF BTU

20, 000

15.000

10.000

5, 000

0

1975

1980

1985

1990

CALENDER YEAR

D

SALES El TRANSPORTATION

(SOURCE)AMERICAN GAS ASSICIATION.'GAS FACTS '92'

(NOTE)1990 is the first year 'TRANSPORTATION

VOLUMES" are reported.

TABLE 10. CUSTOMER REWUIREETS BY END-USE SECTIOR

IResidential Camercial Industrial Electric

native

tility

... . t....iv. ... s s : ... .. no .... ... • ... ... ... y ... .... ...y ...

Fuel-switc~ingiapi ity lonwph hi$.

Purchasin6 options

...

-

nodeate low hihiiI_.__oZ

Z II

. ... .... . . ... . ... ... ... .I ... .- ... ... . . .

Service reliability low low

Plannin horizon ... .. j.q te.. ju.l terU .sort-tew .sbort-term Uge Pattern seasonal sesonal yr-row d yea-round

Safet reliance LDC IC self self

(SOURCE) Exective Enterprise. Inc.." Natural Gas'