HAL Id: hal-02952087

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02952087

Submitted on 29 Sep 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Review of composite sandwich structure in aeronautic

applications

Bruno Castanié, Christophe Bouvet, Malo Ginot

To cite this version:

Bruno Castanié, Christophe Bouvet, Malo Ginot.

Review of composite sandwich

struc-ture in aeronautic applications.

Composites Part C: Open Access, Elsevier, 2020, 1, pp.0.

an author's

https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/26733

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100004

Castanié, Bruno and Bouvet, Christophe and Ginot, Malo Review of composite sandwich structure in aeronautic

applications. (2020) Composites Part C: Open Access, 1. ISSN 2666-6820

Review

of

composite

sandwich

structure

in

aeronautic

applications

Bruno

CASTANIE

a,∗,

Christophe

BOUVET

a,

Malo

Ginot

a,ba Institut Clément Ader (ICA), Université de Toulouse, CNRS UMR 5312, INSA, ISAE Supaéro, IMT Mines Albi, UPS, Toulouse, France b Elixir Aircraft, Batiment D1 - 6 rue Aristide Bergès, 17180 Périgny, France

Keywords:

Composite Sandwich structures Aeronautic

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thispaperpresentsareviewoftheissuesconcerningsandwichstructuresforaeronauticalapplications.Themain questionsraisedbydesignersarefirstrecalledandthecomplexityofsandwichstructuredesignforaeronautics ishighlighted.Thena reviewofapplicationsispresented,startingwithearlyexamplesfromthe1930sand theSecondWorldWar.Thegrowthintheuseofsandwichmaterialsincivilandmilitaryapplicationsisthen developed.Recentresearchandinnovationsconcludethepaper.

1. Fundamentalsofsandwichstructuresforaircraftapplications

1.1. Definition,symmetricandasymmetricsandwiches

“Thecharacteristicfeatureofthesandwichconstructionistheuse ofamultilayerskinconsistingofoneormorehigh-strengthouterlayers (faces)andoneormorelow-densityinnerlayers(core)”.This defini-tion,proposedbyHoff andMautnerinoneofthefirstarticlesdevoted tosandwichconstruction,in 1944[1],remainscurrentandhasbeen takenupinvariousformsintheworksdevotedtothistypeofstructure

[2–7]. Greatnumbersofcombinationsof materialsandarchitectures arepossibletoday,bothforthecoreandfortheskins[8].However,for aeronauticalapplications,certificationgreatlyrestrictsthepossibilities. Today,onlyhoneycombcoresmadeofNomex,aluminiumalloyora limitednumberoftechnicalfoamsofverygoodqualityareused. Sim-ilarly,forskins,wemainlyfindaluminiumalloysandlaminatesbased onglass,carbonorKevlarfibres.AccordingtoGuedra-Degeorges[9], andalsointhecaseofsomestackingdescribedin[10](seealsoFig.22), foraeronauticalapplications,theskinshaveathicknessoflessthan2 mm.Sandwichesfallintotwocategories.Symmetricalsandwiches,such astheoneillustratedinFig.1,areusedmainlyfortheirresistanceto bucklingandtheirbendingstiffness.Thistypeofsandwichisperfectly suitedtopressurizedstructuresorthosesubjectedtoanaerodynamic loadand,generallyspeaking,itisbyfarthemostwidelyused.

Another,somewhatlesspopular,typeof sandwichis alsousedin aircraftconstruction:the asymmetricalsandwich(seeFig. 2). Asfor theclassicfuselagescomposedofathin skinstabilizedbystiffeners, anasymmetricalsandwichismadeupofafirstskinincarbonlaminate calledthe“WorkingSkin”,whichtakesmostofthemembranestresses fromthestructure.Thebucklingresistanceofthisskinisprovidedbya

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:bruno.castanie@insa-toulouse.fr(B.CASTANIE).

coreandasecondskindesignedattheminimumallowedandconsisting ofoneortwopliesofcarbonorKevlar,calledthe“StabilizingSkin”.

Inadditiontoitsparticularlyhighmechanicalcharacteristics,this solutionhastheadvantageofitsjunctionzonesbeingsituatedinpure laminateareas,thuscircumventingthedelicateproblemofthepassage oflocalizedforcestothetwoskinsbyinserts.Ontheotherhand,its useislimitedtonon-pressurizedandmoderatelyloadedstructuresof thehelicopter,lightaircraftordronetype. Anotherfundamental dif-ferenceisthegeometricnon-linearbehaviourduetotheoffsetofthe neutralline(inbeamtheory)withrespecttotheloadinglinelocatedin themiddleoftheworkingskin.Thisoffsetinducesabendingmoment thatisallthegreaterwhenthedeflectionishigh.Therefore,aforce/ displacementcouplingoccurs,whichgeneratesatypicalgeometric non-linearresponseandrequiresanadaptedapproach[11–14].Accordingto theexperienceoftheauthors,thistypeofstructureisoptimalfromthe masspointofviewfornon-pressurizedstructuressubjectedtolowloads. Ithasbeenappliedinmilitaryandcivilhelicopters[16]anddrones,and hasbeenstudiedfortheSolarImpulseplanes[17].

1.2. Basicmechanicsandsizingissues Linearstaticehaviour

Theideabehindsandwichconstructionistoincreasetheflexion in-ertiawithoutincreasingthemasstoomuch,asshownbyD.Gay[7]in asimplenumericalapplicationof3-pointbendingonastainlesssteel beamandthenusingthesamebeamwitha20mmthickhoneycomb sandwichcore(seeFig.3).Themassaddedisverylow(20%),whilethe deflectionunderbendingisdividedby22(Eq2ofFig.3).Itwouldhave beendividedby90(𝛿skins)ifthedisplacementduetotransverseshear

hadnotbecomepreponderantbecauseoftheweaknessofthemodulus ofthecore(Gcore=46MPa).Here,wearetouchingonthesubtletyof sandwichstructures,wheretheexpectedbenefitsareoffsetbythe

Fig.1. Sandwichconstruction.

Fig.2. Asymmetricsandwichstructures.

Fig.3. Bendingcalculationofasandwichbeam.

plexitiesgeneratedbyalightcore.Allcasesoflinearcalculationsunder simplestaticstresseshavebeenwidelydevelopedintheliterature[2–7], enablingsizingoftheskinsandthecore.

Thecorerequiresspecialattentionbecausetheallowablesarevery low,oftheorderofoneMPa,whereastheskinsgenerallysupportloads ofseveralhundredMPa.Therefore,therelativeorderofmagnitudeof thestressesinthecoreis1%orless.Thisphenomenonisparticularly sensitivein thecase ofcurvedsandwiches,e.g.forthetailboomsof helicoptersorincurvedfuselages[18–20],andalsofortaperedareas.

Globalandlocalbuckling

Asafirstapproximation,theincreaseinthebendingstiffness[EI] promisesaproportionalincreaseinthecriticalloadforbucklingifwe re-fertoEuler’sformula:FcEuler=𝜋2EI/L2forasimplysupportedbeam(L

isthelengthofthebeam).But,hereagain,theinfluenceofthecorehas tobetakenintoaccountandtheformulabecomesFCSandwich=FcEuler

/(1+FcEuler/tc.Gc),whereGcisthetransverseshearmodulusofthe

coreandtcisthethicknessofthecore.Thissignificantlyreduces buck-lingresistanceasshownbyKassapoglou[5].Inaddition,thepresence ofalightcorealsogenerateslocalbucklingmodesoftheskin (wrin-kling)orglobalbucklingmodescontrolledbythecore(shearcrimping). Thesemodesareoftencriticalandcanbethecauseofprematurefailure iftheyarenotgivenproperconsideration.Theymustimperativelybe theobjectofin-depthinvestigationevenifthisinvolves3Dfinite ele-mentmodelling.Forpre-sizing[4–6],aformula(Eq.1)resultingfrom arudimentaryanalyticaltheorywithrestrictiveassumptionsdeveloped byHoff andMautnerin1945[21]is usedforthecaseofwrinkling. Althoughthisformulagivesthetrendscorrectly,theresultsitprovides canprovetobeveryfarfromthoseofexperimentaltestsandasafety factorisrequired.Zenkerts[4]proposesreplacing0.91by0.5 accord-ingtohisexperienceinthenavalindustry.Kassapoglou[5]discusses therelevanceofthisformulavsfiniteelementmodellinginthecaseof compositeskinsandtests,andalsoproposesknockdownfactors.In

aero-Fig.4. Non-linearin-planecompressionresponseof symmet-ricsandwichstructures.

nautics,itiscommontotakeasafetyfactorof3toallowfortheintrinsic limitationsoftheformulaandtheeffectofinitialshapeimperfections

[22].

𝜎𝐶𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙=0.91√3𝐸𝑆𝑘𝑖𝑛⋅ 𝐸𝐶𝑜𝑟𝑒⋅ 𝐺𝐶𝑜𝑟𝑒 (1) Eventhoughitsage,itssimplicityanditsrelativerelevancecause thisformulatoremainthemostused,manyotherapproacheshavebeen developedrecently[23–30],forexample)andwoulddeservemore ex-perimentalandnumericalevaluation.Moreover,thesizingof aeronau-ticalstructurescurrentlyusesaGFEM(GlobalFiniteElementModel) thatdoesnotcapturelocalbuckling.Thereforestrategiesofglobal/ lo-calcalculations[31]orapproachesusinganalyticalcriteriaremainto bedefined.Notealsothatcertainenvironmentaleffects,suchas tem-perature,cansignificantlyreducethecriticalstressoflocalbucklingin thecaseofasandwichwithafoamcore[32],whichcanbecriticalfor thestrengthoflightstructuressuchasglidersorprivateplanes.

Nonlinearstaticbehaviour

Ingeneral,nonlinearcalculationofsandwichesisnotnecessary be-causetheyaresubjecttobendingandtheirhighstiffnessmeansthat thestructureremainsundertheassumptionofsmalldisplacementsand strains.However,foraeronauticalstructures,inparticularthosethatare notpressurized,membraneloadsaredominant.Thisisparticularlythe caseforasymmetricalsandwichstructuresloadedbytheworkingskin, whichnaturallyhavethisbehaviour[11–15].Forexample,whenthe workingskinisloadedincompression,thestabilizingskinmaybreak intension.Ontheotherhand,itislessknownthatevensymmetrical sandwichstructurescanexhibitnon-linearbehaviourincompression, whichcanstronglyinfluencethedesign[13,33,34].Thiscaseisshown inFig.4,wherethesoftwaredevelopedin[11–13]wasusedtocompute thecompressionresponseofanasymmetricallyloadedsandwichbeam withadistributionoftheforceintheskinshavingtheratios49-51%or 48-52%.Thestrainsweretakenatthecentreofeachofthetwoskinsand typicaltulip-shapedcurveswerefound.Thesecurvesarealsoobtained undercompressiontestsonbeamsorsandwichplates.Thisphenomenon hadbeenidentifiedveryearlybyHoff andMautner[1],whoattributed thenonlinearresponseintheteststotheloadingoftheskinsnotbeing strictlyidentical.Thisseemstobeconfirmedbythepresent computa-tion.Hoff andMautnerperformedacheckofdissymmetryofthestrains intheskinsupto5timesbeforecarryingoutatesttofailure.Forthis reason,grindingofthefacesofthetestpiecesisrecommendedbefore performingthistypeoftest.Someauthorshaveattributedthisnonlinear responsetoanimperfectinitialshape[35]whichmayalsohave

con-tributedtothephenomenon.Inpractice,thereareseveralotherpossible causes,suchasvariationsinmanufacturingduetosmallstackingerrors, ordifferencesinfibrevolumeand/orsurfacefinishduetothe manufac-turingmethod.Itisalsopossiblethatdifferencesinloadingbetweenthe skinswillappearifataperedareaisused.

Thetulipcurvesareboundedbythecriticalforceofthestructure. ItisclassicaltouselinearassumptionstosizethesandwichattheUL designpoint(UL:Ultimateload).InFig.4,thispointcanbefoundatthe intersectionbetweenthelinearresponse,inblack,andthecriticalforce (verticalline).Sizingisgenerallydonewithadamagetolerancepolicy (seenextsubsection)insuchawaythat,atthispoint,thestraindoes notexceedanallowablevalue(forexample,about6000μstrainhere). However,witha nonlinearcalculationasproposed,itcanbe shown that thisvaluemaybe reachedmuchearlier,at around500N/mm, wellbeforethecriticalload.Thereforeadesignthatdidnottakethis behaviourintoaccountwouldbewrong.Thisphenomenonis,however, lessnoticeableforplatesthanforbeamsandnaturallydecreaseswith thebendingstiffnessofthesandwich[33].

1.3. Damagetolerance

Lowspeed/low energyimpacts,duetohandlingoperations dur-ingmanufacturingortodroppedtoolsduringmaintenanceoperations, aregenerallyconsidered.Aeronauticalsandwichstructuresaccordingto theGuedra-Degeorgesdefinition[9]areverysensitivetoimpact,asare laminatedstructures.Theimpactgeneratesavarietyofdamageinthe coreandtheskins,andtheresidualstrengthcanbegreatlyreduced.So adamagetolerancepolicymustbefollowed(seeFig.5and[10]),which dependsontheaircrafttype(FARorEASAfrom23to29).Giventhe securitychallenges,itmustbepragmaticandconservative.Themethod wasinitiallydevelopedforthefirstcertifiedprimarystructure:theATR 72compositewingbox[36]andisnowwidelyused[10,37].Theidea istodistinguishundetectabledamagefromdetectabledamage.Forthe former,thestructuremustbetoleranttodamagefromthepristinestate andis thereforecertifiedtoultimateloads(UL).Forthesecond,the damagemustberepaired,butadistinctionismadebetweendamage thatrequiresathoroughinspectiontobedetected(loadsofthedesign structurewithdamage:LimitLoad)andthoseimmediatelydetectable (often0.85LL).Thedetectabilitythreshold,calledBVID(BarelyVisible ImpactDamage),isdeterminedbybenchmarkswithpreciseinspection times.Foradetailedinspection,Airbushassetitat0.3mmand,fora quickinspection,at1.3mm[38].

Fig.5. Damagetolerancepolicy(reproducedfrom[10]).

Fig.6. CompressionAfterImpactapparatuswithanti-bucklingknives.

Theallowablescorrespondingtothevariouscasesareobtainedin CompressionAfterImpact(CAI).Thedeterminationisaboveall exper-imentalinordertosatisfytherequirementsofthecertificationand de-terminethevaluesAorB.AtestsetupasshowninFig.6isusedwith aspecimenofdimensions100×150mm2.Thespecimenisimpacted

initscentreaccordingtointernalAirbusorBoeingstandardsoralso ASTM. Theallowable thencorresponds tothemaximum strain𝜀Max

measuredduringthetest.Thesizingwithrespecttodamagetolerance isthereforesimplyreducedatallpointsofthestructuretotherelation: 𝜀Structurecompression<𝜀Max.

Inthiscontextposedbyaeronautics,numerousstudieshavebeen carriedoutinordertobetterunderstandandmodelthephenomena in-volved.Onlyafewarementionedhere-inparticularthesummarywork oftheFAAorNASA[39–43].Whenanaeronauticalsandwichstructure receivesanimpact,thedamagetotheskinsissimilartothaton compos-itelaminatesbutthecoreiscrushedlocally(seeFig.7).Thecrushingof Nomexhoneycombstructuresisverycomplex,withwrinkling,tearing anddamagetothephenolicresinlayer[46].Thiscomplexbehaviour canbemodelledaccordingtovariousstrategies[40,44]:detailedmodel

[45],discretestrategiesbased onnonlinearsprings[46–50]or dam-agemechanicsusinganorthotropiccontinuum[51,53].Whendamage afterimpactiswellcaptured,itisrelativelyeasytodevelopefficient modelsforcompressionafterimpact.Thecriteriaforfailurearemost oftenmaximum straincriteriaon theskin[51]orthemore original

Fig.7. Impactdamageonanaeronautic sandwichforseveral energylevels (reproducedfrom[9]).

corecrushcriterion[52].Thebehaviourincompressionafterimpact iswellunderstood.Itisacombinationof3non-linearities:ageometric non-linearcouplingwiththeindentedzone,whichwillcauselocal bend-ingandcompressthehoneycomb;anon-linearresponsetothecrushing ofthehoneycomb;and,finally,thedamagedbehaviourwithinthe com-positeskinsortheplasticityofmetallicskins.Unlikerigidbodies,which tendtocreateadentshapesimilartotheimpactor,softbodiescreate analmostuniformcorecrushundertheimpactzone.Thistypeof im-pactseemstobemoresevereforthestructuralstrengthofthesandwich panel[54].

1.4. Joiningsandwiches

Although,forcompositestructuresingeneral,itissaidthat"thebest wayofjoiningisnojoining", inpractice,makingjointsis inevitable. ThefirsttypeofjointconsideredhereissandwichtosandwichwithT,L oredgetoedgejoints[55–62]forexample).Therearenumerous tech-nologicalpossibilities,whichmustbeexaminedbeforedeterminingan optimuminagivencontext.Feldhusenetal.([57]andFig.8)analysed 783initialsolutionsbeforeconvergingononly18"promisingconcepts" accordingtothefollowingcriteria:

• Theconnectionmustbeabletotransmitallforcesandmomentsthat occur.

Fig.8. Edgejunctions(from[57]).

• Thedimensionsofthejointshallbeassmallaspossibleyetaslarge asnecessary.

• Elasticdeformationsthatwilloccurunderloadmustnotbecomeso largeastoharmthejoint.

• Theprincipleofuniformstrengthshallbe appliedtosandwich el-ementsandjoint.Thefatiguelifeofallpartsinvolvedshallbethe same.

• Thejointshallbeaslightweightaspossible.

• Theintersectionareabetweensandwichandjointshallbedesigned insuchawaythatsharpdeflectionsoftheforceflowlinesorstrong changesintheirdensityareavoided.

Anotherinterestingstudyworth mentioningis thatoftheRobust CompositeSandwichStructure(RCSS)programmecarried outin the USAin the late1990sfor thedesign of anF22 fighter plane struc-ture.Thedesigncriteriawere:loadtransfer,producibility,durability, repairabilityandfuelsealing[56].

Anotherveryeffectivewaytoachievethejunctionsistodesigna skintolaminatetransition.Thejoinisoffsetintoalaminate,whichis simplertodesignandmorerobust(seeFig.2andFig.9,solution12,

[63–68]).AlthoughnotchosenfortheRCSSprogramme,thistypeof so-lutioniswidelyusedinhelicoptersorconvertibles[11,16,65]forboth symmetricalandasymmetricalsandwiches.Despiteitsinterest,thistype ofsolutionhasbeenlittlestudiedbecauseitgeneratesadditional com-plexitieswithnumerousnonlinearcouplingsthatcangenerate prema-turefailures.Inaddition,itisanareathattransfersloadsandmustbe sizedaccordingly,especiallyinthepresenceofreinforcingplies[34].

Themostcommonlyusedjoiningmethodforsandwiches,whether foraeronauticsorspace,is theuse ofinserts[69–83].Aninsertisa localreinforcementofthecorethatmakesitpossibletotolerate con-centratedforces,mostoftenviabolts.Insertscanbeusedeithertojoin sandwichestogether,tojoinasandwichparttotherestofthestructure (highlyworkinginserts)ortofixsystems,cablesorhydraulicpipes(low workinginserts).Theirstudyisstilllargelysemi-empirical,beingbased eitheronexperimentalresultsgivenbysuppliersoronanalytical mod-els[69–71]thataresometimesveryefficient[72–73].Theseapproaches havethemaindrawbackofremaininglinearandthereforeveryfarfrom

thecomplexfailurescenariosidentifiedintheliterature[74–77]: buck-ling,postbucklingandtearingofNomexHoneycombcores,compression andcrushingofthepotting,punchingoftheskins,localdebonding(see

Fig.10).Thesephenomenaarealsodifficulttotacklebecausethereis astrongdispersionlinkedtothemanufacturingmethods,which gener-atenumerousdefects[78–80].Intherarerecentpapers,twomodelling strategiesareemployed:refinedhoneycombmodels[81]orevenlighter modelsusingdamagemechanicsandvolumicelements[82],which al-lowthecreationoffailuremodemaps[83].Itisinterestingtonotethat, accordingtoMezeixetal.[84],thepull-outbehaviourafterimpactof theinsertsisverygood,withlimitedreductionoftheorderof10-15%. 1.5. Manufacturingandcontrol,repairs,moistureandotherissues

Manufacturing

Therearethreeusualwaysofmakingsandwichstructuresinan au-toclavetoensureaeronauticalquality:

• Co-curing:bothskinsfreshandbondedtothecore,withorwithout anadhesivefilm,duringcuring(Onecuring).

• Co-bondingprocess:oneskincured,anotherfreshbondedtothecore whilecuring(Twocurings).

• Secondarybonding: thetwo skinsare curedseparately andthen bondedtothecorewithanadhesivefilm(Threecurings).

Usually,thecuringpressureinthepresenceofNomexhoneycombis limitedto3barstoavoidcorecrush,especiallyintherampdownarea

[85].Despitetheimportanceofthesubjectinpractice,alimitednumber ofstudieshavebeenpublished,probablybecause,eventoday,the man-ufactureofcompositestructuresreliesheavilyonindustrialknow-how, whichisjealouslyguarded.In1997,KarlssonandAstrom[86]presented andmadeaqualitativecomparisonofthemaintechnologiesavailable tomakesandwichstructures,inparticularinthenavaland aeronau-ticalindustries.D.A.Crumpetal.[87]comparedthemethodsinand outsideautoclaveforthemanufactureofsecondarystructuresandfound thatthemethodoutsideautoclave(ResinFilmInfusion)offeredthebest economicequation.Theproblemoftheairtrappedintheclosedcellsof

Fig.9. Robustcompositesandwichstructures(reproducedfrom[56]).

Fig.10. Failurepatternofanaeronauticinsertusedfor land-inggeardoorunderpull-outloading(reproducedfrom[76]).

thehoneycombwasalsostudiedandmodelled,payingparticular atten-tiontostudyingtheevolutionofthepressureduringcuring[88–92].In arecentstudy,Andersetal.[93]showedspectacularfilmsofthe poly-merizationoftheadhesivefilmaccordingtotheparametersofcuring andthegoodorbadrealizationofthemenisci,thusconfirmingthe em-piricalfindingsoftheindustry.Unlikethesituationforlaminate[94], thereisnoadvancedthermokinetic,thermochemicalor thermomechan-icalmodelofthecuringofaeronauticalsandwichesthatcanbeusedto predictshapedefectsafterspring-back[95]orspring-in[96].The avail-ablestudiesareessentiallythermomechanicalandanalytical[97–100]. Anothercommonmanufacturingdefectiscalled“telegraphing”.Itisa shapedefectinvolvinglocalundulationwithrespecttothehoneycomb cells.However,aeronauticalstructuresarelessconcernedthanspace structuresbecausethetechnologicalminimaareatleasttwopliesfor theskinsandthecellsizesaresmall.

Despite the necessarily limited extent of this bibliographical overview,itisclearthat,giventhecurrentstateoftheartinthe mod-ellingoflaminatecuring,muchresearchremainstobedonewithregard tothemanufactureofsandwichstructures.Thisactioncouldalso pro-motetheirdevelopmentbysecuringindustrialization.

Non-destructivetesting

Inaeronautics,allstructuralpartsmustbecheckedtoensuretheir initial quality. Inthecertification processof theBeechcraftStarship

[10],itisstated:“Acceptancecriteriawereestablishedforstructurewith porosity,voids,anddisbondstoaccountforinitialquality(flaws) devel-opedduringthemanufacturingprocess.Damagemodessuchasporosity, voids,anddisbondsweresubjectedtospecifiedacceptancecriteria.This initialqualityisintrinsictothemanufacturingprocessandthe inspec-tionstandardsandrepresentstheas-deliveredstate,andtherefore,the structuremustbecapableofmeetingallrequirementsofstrength,

stiff-Fig.11. Schematicofa scarfrepair appliedtoa sandwich component.Top:topview,bottom:sectionview(Reproduced from[103]).

ness,safety,andlongevitywiththisinitialquality”.Today’sinspection methodsinanindustrialcontextaremainly:visualinspection, ultra-sonicandX-rayinspection,[101,102].TheManualTapTest,Automated TapTest,MechanicalImpedanceAnalysisandC-Scanhavebeen com-pared[103]and,accordingtotheauthors,“Themoresophisticatedthe method,themoreaccurateitwasindeterminingthesizeofthe dam-age”.Theacousticmethodsaremainlyusedtodeterminethe manufac-turingqualityoftheskinsortodetectskin/coreseparation.These meth-odsaregenerallydifficulttoimplementinthecaseofsandwichesand requiregoodknow-how.Othersexist,suchasinfraredorholographic methods[104],butarelessinuseinindustry.

Repair

Inlinewiththedamagetolerancepolicy(seeFig.5and[10]),assoon asdamageisdetected,itmustberepaired.Repairinstructionsaccording tothetypeofdamagearegivenintheSRM(StructuralRepairManual) ofthevariousmanufacturers.Theprinciplesofrepairareexplainedin

[103–107]accordingtowhetherthedamageisminorormajoranda typicalrepairisshowninFig.11.Althoughtherepairprinciplesmaybe simple,thesizingoftheserepairsiscomplexandconcernsthescientific problemsofbondedjointswithcomplexgeometries[103–112].Despite everything,ifcorrectlycarriedout,repairsallowmorethan90%ofthe initialresistancetoberecovered,eveninthecaseofrepeatedimpacts

[109].Thus,forgliders,thelifetimecanreach50yearswithrepairs. Moistureingression

Sandwich structures have a bad reputation because a number of problems or incidents have been reported in the open literature

[113]andprobablymanymore byrumour.Theproblemismost of-tenlinkedtoclosedhoneycombcellsthattrapmoisture.Thehumidity canthencausepatchesofcorrosiononthemetallichoneycombcores, decreasesintheresistanceofthebondedjointbetweentheskinandthe core,ordegradationoftheNomexduringthefreeze-thawcyclesthat accompanychangesinexternaltemperaturesduringflights[113–118]. Thecausesofmoisturediffusioncanbelinkedtotheverynatureof hydrophilicepoxyresins[116],topoordesignofthecoreclosure,to

poorsealingafterarepair,oreventoimpactsbelowtheBVID[114]. From[151],theUSNavybannedtheuseofaluminiumhoneycombon theV22 andF/A 18programmes. However,asthenumberof flying sandwichstructures shows,these problemsareperfectly manageable

[114].Onemethodistodesigntheskinswithaminimumnumberof pliesoffabriconthesandwichtoensureagoodseal.Forcertification authorities,WaterIngressionTestswererequiredforthecertificationof theBeechcraftStarship[10]:

“Twelve-inch-squarepanelswithinflictedpuncturesofonefacesheetwere immersedinwatertoallowwaterintothecoreinthepuncturedregions.They werethensubjectedtofreeze/thawcycleswithvacuumappliedduringfreeze tosimulatehighaltitudeflightandtheninspectedtoensurethatwaterdid notpropagatebeyondthepuncturedregions.”

1.6. Summary

Inthissection,themainproblemsspecifictothedesignof aeronau-ticsandwichstructureshavebeenbrieflypresented.Others,like light-ningstrikesorcertificationtests,havevoluntarilynotbeentreated be-causetheyaregenerallyhandledinasimilarwaytothoseonlaminated structures[10].Itisclearthatthepotentialgainofferedbysandwich structuresisverylargebuttheircomplexityisgreaterandtheymustbe approachedwithprudenceandhumilityand,ifpossible,bycapitalizing onexperiencetoguarantee success.Inthefollowinghistorical devel-opments,wewillgraspthiscomplexitythroughanumberofexamples. Fromtheresearcher’spointofview,itisinterestingtonotethatmany areas,fromcalculationtomanufacturingandenvironmentaleffects, re-maintobestudiedandimproved.

2. Theverybeginning:Woodconstruction

AccordingtoProfessorHGAllen[119],civilengineeringhasused sandwichconstruction (called“doubleskin” at thetime)since1849 andseveralsourcesclaim thatapatentmayhavebeentakenout in 1915byHugoJunkers(ProfessoratAachenuniversityandthefuture

Fig.12. Gliderwoodsandwichconstruction(reproducedfrom[123]).

fatheroftheJu-52)forasandwichstructurewithhoneycombcore. How-ever,asfarastheauthorsknow,heneverwentontoexploititforhis ownaircraft[120]. In1924,apatentfora gliderfuselagewasfiled byTheodoreVonKarmanhimselfandP.Stock[121]andis citedin thepapersofNicholasJ.Hoff[1,122,123].AccordingtoHoff,“It in-dicatesthattheglidingsocietyofthePolytechnicInstituteofAachen musthaveplanned,ifnotbuilt,afuselage havingasandwichskin”. Thus,gliders wereprobably thefirst flying structurestohave afull sandwichconstruction.Therequiredcriteriawere:aerodynamic refine-ment,lightweight,inexpensiveproduction,sturdinessandeaseof re-pair,andalsomanufacturingabilitytomakedoublecurvedstructures. Themanufacturingprocessusedawoodenmouldandalargenumber of clamps.Themouldwas linedwithmetalresistanceheatingpads, thetemperatureof whichwascontrolledbyathermostat. Auniform pressurewasmaintainedbymeansofavacuumbagtocurethe ther-mosettingphenol-formaldehydegluethatwasused.Itisimportantto noteherethatthefirstdevelopmentofawoodsandwichstructurewas rootedintheapplicationofefficientgluesforbondingwoods.The urea-formaldehydeadhesiveknownbythecommercialnameof“Aerolite” wasdevelopedbyDeBruyne[124],whowouldlaterinventtheRedux films.

AsandwichD-Sparandatypicalfuselage ofa gliderofthetime areshownFig.12.Itisremarkablethattheadvantagesofsandwichor compositestructures,suchasthesimplificationofthedesignandthe reductioninthenumberofparts,werealreadyhighlightedasindicated bythesleekdesignoftheD-Spar.AccordingtoHoff andMautner“an interestingdesignfeatureisthelocalreinforcementofthestructureto

with-standtheconcentratedloadsimposedbytowingandlanding.Backoftowing hookAandaboveskidCintheregionmarkedB,thecoreofthesandwich skinisspruce.Thedensityofthisspruceinsertischangedthroughthe appli-cationofcompressionduringthemanufacturingprocessinsuchawaythat thespecificweightis1.2nearhookAwhileitdecreasesgraduallyto0.5near bulkheadD.Elsewherethecoreisbalsawithitsthicknessdecreasingfromthe highlystressedbottomportionofthefuselagetowardthelightlystressedtop portion.ThewingisattachedtothetwomainframesDandEofthefuselage. BetweentheframestwobeamsFarearrangedtosupportthelandingwheel”. Itshouldbenotedthattheexamplegivenin[123]andreproducedhere isnotdatedandisprobablyrelatedtoSecond-World-Warorearlier glid-ers.Today’sgliderstructuresarestillmadewiththinsandwichbutthe coresareoffoamandtheskinsofglassorcarbon.

Someparts of aircraftwerepunctuallymanufacturedwith wood-basedsandwichstructuresinthenineteen-thirties.Hoff[122]reported pontoonsoftheSundstedtplanedevelopedintheUSAin1919,the Sky-dineaileronin1939,thefuselageoftheDeHavillandComet(DH88) in1934andDeHavillandAlbatrosin1938andthewingsofaFrench airplanedevelopedbySE.Mautnerin1938.TheDeHavillandAlbatros DH91wasafour-enginetransatlanticmailplaneabletocarry22 pas-sengers,whichmadeitsfirstflightin1937(seeFig.14(a)).The sand-wichwasdesignedwithplywoodskinsandabalsacore.FortheFrench aircraft,aFrenchpatent,“theBrodeauprocess”,datingfrom1934is de-tailedin[125](seeFig.13).Thesandwichismadeupof2plywoodskins andacorkcoredrilledwithholestooptimizethemass.Thisprocessis believedtohavebeenappliedtoaLignelaircraftin1938.

ItisnotwellknownthattheMorane-Saulnier406(seeFig.14(b)), asingle-seatinterceptorfighterbuiltFrance,whichfirstflewonAugust 8th,1935,wasdesignedwithawingmadeof“Plymax”.Thisisa

sand-wichstructurewithaluminiumskinsandanOukoumé plywoodcore. However,thistechnologicalchoicewascomplexfromamanufacturing pointofviewandpenalizedtheramp-upinproductionoftheaircraft. Inaddition,thisaircraftprovedtobeinferiortotheMesserschmittBf 109intheBattleofFrancein1940.Thistypeofplywood/aluminium structurehasalsobeenrediscoveredrecentlyandshowsverygood me-chanicalqualities[126]incompressionandcompressionafterimpact

[127].

Theplanethatismostfamousandmostcitedforitsplywoodskin andbalsacoresandwichstructuresisthedeHavilland“Mosquito” DH 98(seeFig.14(c)).Itturnedouttobeoneofthebestplanesofthe Sec-ondWorldWar,bothforitspureperformanceandfortheextraordinary missionsitachieved.AsProfessorHGAllennotesin[119],itisoften wrongly presented asthefirstplanewithprimary partsin sandwich structures.However,itsdesigncomesfromtheexperienceacquiredby deHavillandwiththeDH88andDH91.ItisverysimilartotheDH88, whichhadbeenproposedtotheBritishWarMinistryinalightbomber versionbutrefused.However,deHavillandpersistedandshowed fore-sightinanticipatingthealuminiumshortagethatoccurredduringthe SecondWorldWar.

The detailed design of the structure is perfectly explained in

[128]andreproducedhere:“LiketheCometandAlbatrossmainplanes,de HavillandconstructedMosquitomainplanesoutofshapedpiecesofwoodand plywoodcementedtogetherwithCaseinglue.Approximately30,000small, brasswoodscrewsalsoreinforcedthegluejointsinsideaMosquitomainplane (another20,000orsoscrewsreinforcedgluejointsinthefuselageand em-pennage).Theinternalmainplanestructureconsistedofplywoodboxspars foreandaft.Plywoodribsandstringersbracedthegapsbetweenthespars withspaceleftoverforfueltanksandengineandflightcontrols.Plywood ribsandskinsalsoformedthemainplaneleadingedgesandflapsbutde Hav-illandframed-uptheaileronsfromaluminiumalloyandcoveredthemwith fabric.Sheetmetalskinsenclosedtheenginesandmetaldoorsclosedover themainwheelwellswhenthepilotretractedthelandinggear.Tocoverthe mainplanestructureandaddstrength,deHavillandwoodworkersbuilttwo topmainplaneskinsandonebottomskinusingbirchplywood.Thetopskins hadtocarrytheheaviestloadsothedesignersalsobeefedthemupwithbirch orDouglasfirstringerscutintofinestripsandgluedandscrewedbetweenthe

Fig.13. "Brodeau"process,1934[125].

Fig.14. Picturesofsomeaircraftwithsandwichstructures(a)deHavilland88"Albatros",(b)MoraneSaulnier406,(c)deHavilland98"Mosquito",(d)Sandwich typemouldedfuselage(Pictures(a),(b),(c)fromWikipedia,(d)from[122]).

twoskins.Thebottomskinwasalsoreinforcedwithstringers.Togetherthe topandbottomskinsmultipliedthestrengthoftheinternalsparsandribs.A Mosquitomainplanecouldwithstandrigorouscombatmanoeuvringathigh G-loadswhentheaircraftoftencarriedthousandsofadditionalpoundsof fuelandweapons.Tomaintainstrength,trimweight,andspeedfabrication time,theentiremainplaneandsparwasfinishedasasinglepiece,wingtipto wingtip,withnobreakwherethewingbisectedthefuselage.Afinishedand paintedmainplanewaslightandstrongwithasmoothsurfaceunblemished bydrag-inducingnailorrivetheads.”

Itis quiteremarkabletosee thattheconstructionwas really op-timizedintermsof“stacking” according totheareasof theaircraft, withasimplebirchplywoodskinfortheundersideofthewingand asandwichconstructionfortheupperside.Manufacturingwasa one-shotprocess,whichisnowsoughtbymanufacturerstoreducecosts(see

Fig.14(d)).Therearealsoglued/boltedjointsthatarestillused to-dayincertainstructuresofmilitaryhelicoptersandarethesubjectof activeresearchtoreducethenumberoffastenersandbringdowncosts ([129,130]forexample).Forthesereasons,beyondjustsandwich struc-tures,theMosquitoisoneofthemostimportantprecursorsofmodern, composite-structureplanes.

3. SandwichhoneycombstructuresforMACH2andMACH3

aircraft

Inthe1950sand1960stheColdWarragedonandauthorizedthe developmentofextraordinaryaircraftprogrammesintheUnitedStates (andprobablyalsointheUSSR,buttheauthorhasnoinformationon Sovietaircraft).Thefirstthatcaughttheattentioninthisarticleisthe

Convair B-58bomber,which madeitsfirstflight onNovember11th,

1956andwhichcouldreachMach2.4.OnehundredandsixteenB-58s werebuiltbeforethebomberwaswithdrawnfromoperationalservice in1969.Thestructurewasextremelylight,makinguponly0.24per centoftheaircraft’sgrossweight,anexceptionallylowfigureforthe era[56].Itwaslighterthanlateraircraft(F16:0.328,F14:0.422,F15: 0.361).Thedetailofitsstructureisexplainedin[131].Thewingsurface consistedofasandwichstructurewithaluminiumskinsandaphenolic resinfiberglassclothhoneycombcore.Theuseofthistypeofsandwich allowedsealing,thusreducingthenumberofsparsinthewingwhile enablingoperationbetween-55°Cand+126°C.Aspecificadhesivethat couldcreateameniscuswasdevelopedtomakethissandwich.Forthe fuselage,thistypeofstructurewasalsoused,exceptforthehottestparts, whichweremadewithasandwichhavingstainlesssteelskinanda hon-eycombcore.

The XB-70“Valkyrie” wasa MACH3supersonic bomber studied andmanufactured(inonlytwoprototypes)byNorthAmerican Avia-tion(NAA),seeFig.15.ThefirstflightwasonSeptember21st,1964. DuetoitsMACH3speed,theskintemperaturesrangedfrom246°Cto 332°C.Toavoidusingrareandexpensivetitanium,NAAusedastainless steelhoneycombsandwichskin(seeFig.15),whichprovedtobevery efficient,notonlyfromastructuralpointofviewbutalsoforthermal insulation(especiallyforfueltanks)athighspeedwithalowweight penalty[133].Itwasalsointerestingforaerodynamicsmoothnessand acousticfatigueintheinlet.Itcoveredasurfaceareaof2000m2,68% oftheairframe[134].Thesandwichusedwasallstainlesssteelandthe skins werebrazedtothehoneycombinthesamealloyfollowingthe explanationsprovidedin[135]:

Fig.15. (a)and(b):PicturesoftheXB70from[136],(c)typicalsandwichconstructionfrom[135],(d):improveddesignforsealingfrom[134]and[137].

Fig.16. CompositeHoneycombareasoftheSR71,shownin black(from[139]and[140]).

1) preparingthebasiccomponents(core,skins,brazingfoil,closeout edgememberifany)

2) Assemblingtheseelementsundersurgicallycleanconditions 3) Placingtheassemblyinanairtightsteelcontainer,calledaretort,

whichisthenevacuatedandsubsequentlyfilledwithaninertgas, suchasargon.

4) Placingtheretortcontainingthepanelinaheatsourcefortheactual brazingprocess.

Afterdifferenttrials,theelectricblanketbrazingmethodwas pre-ferred.Ittookabout15minutesforapanelandthetemperaturereached about950°Ctomaketheweld.Thenthetemperaturewascarefully re-ducedandasecondcurewascarriedoutformetaltreatment.

However, the process was not immediately efficient and some skins became detached in flight, fortunately without causing ir-reparabledamage.Similarly,improvements totheprocesswere sub-sequently implemented to guarantee the sealing of the tanks (see

Fig. 15). The complete history of this aircraft can be found in

[132].

Despitetheprogrammebeingdowngradedtoaresearchprogramme, probablybecauseofitscostandthearrivalofintercontinentalmissiles, theaircraftsatisfiedtheinitialrequirements,andthetechnologiesfor makingthesandwiches,whichtook5yearstodevelop,havespreadto manyotherprogrammes(727,C141,ApolloandtheSaturnspace ve-hicle)andcreatednumerousspinoffs.Forexample,thebrazingalloy waslaterusedtoattachcarbideandtungstencarbidetoolfaces[135]. Laterstudieswerecarriedoutontitaniumsandwichesbrazedfora su-personic transportplanewerecarriedout...buttheresults werenot usedin practicebecauseof thewithdrawal oftheprogramme[138]. Concorde,whichflewforthefirsttimein1968andreachedMACH2.2, alsousedaluminiumsandwichesforitsrudder[132]andcarbonskin sandwichesforailerons.Thetotalmassofcompositesfortheaircraft alreadyreached500kg[162].

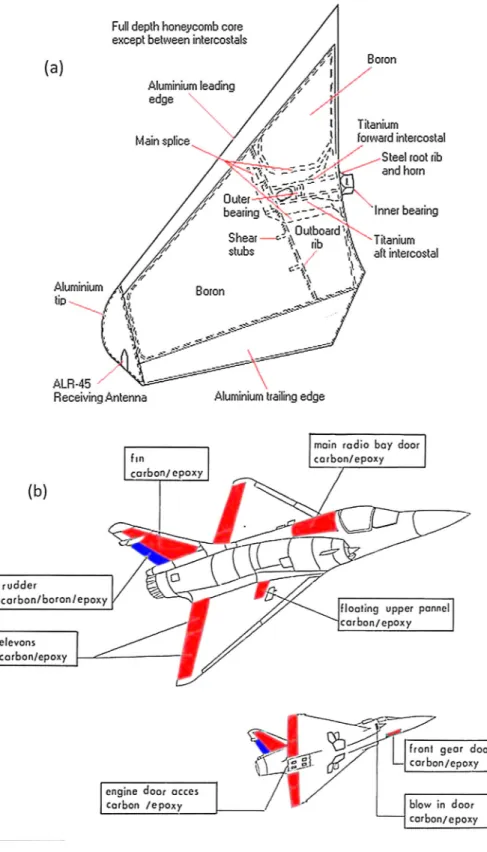

Fig.17. (a)HorizontalstabilizerofF14 madewith boron/epoxy skin andaluminium honeycomb core, (b) DassaultMirage F1carbonandboronsandwich structureoverview.

Itisnotpossibletogiveevenarapidoverviewofthisperiodand thistypeofaircraftwithoutmentioningthefamousSR71“Blackbird”

[141].Despitetheextremelyhighsurfacetemperatures,whichmeant thatthestructurewasmainlymadeoftitanium(unwittinglyprovided bytheRussians),somepartsof theSR71weremadeofasandwich composedofasbestosskins/fiberglass,aluminumnidacore (accord-ingto [140]). These parts werenon-structural butdesigned to pro-videstealth functionsasshown by thetriangularshapes in Fig.16. Afterthefirsttitaniumversions,thismaterialwasalsousedforthe2 rudders.

4. Secondarycompositesandwichstructures

Safetybeingoneofthemainconstraintsinaeronautics,the introduc-tionof sandwichmaterialswithcompositeskinswasperformedvery graduallyin civilaviation,starting withthenon-structuralpartslike interiorparts,sidewalls,bagracks,andgalleys,orflooring(whichis stillinusetoday[81]).Thesewerefollowedbysecondarystructures likespoilers,rudders,ailerons,andflaps,andfinallytheprimary struc-tures, which willbe discussedin thenextsection[142,143]. Inthis sense,militaryprogrammesservedasprecursors,andcomposite

sand-Fig.18. B747overviewofsandwichstructures.

wichstructureshavebeensuccessfullyapplied inmanymilitary pro-grammesaroundtheworldsincethe1960s,whenfibresofboronand carbonbegantobeavailable.Intheannexof[146],acomprehensive reviewofcompositepartsmadeforresearchorproductionisprovided but,mostofthetime,itisnotstatedwhetherthedesignisinsandwich ornot.However,plane-by-planeresearchhasrevealedthatsecondary structuressuchasthelandinggeardoor,speedbrake,flaps,andrudder, werebuiltinaluminiumhoneycomb/boron-epoxyskinandwere ap-pliedtoprogrammesliketheMcDonnelF4,NorthropF5,DouglasA4, GeneralDynamicsF111,GrummanF14(seeFig.17)andmanyothers. InFrance,theDassaultMirageF1horizontalstabilizerswerealso madewithboronepoxyskinsandaluminiumhoneycombcore,for ex-ample.Infact,untilthemid-1970s,boronfibrewasindeedcheaperand moreavailablethancarbonfibre.However,carbonfibreveryquickly supplanteditandmanycarbonsandwichapplicationsstarted,asonthe Mirage2000(firstflightMarch10th,1978).InFig.17(b),thefin,

rud-derandaileronaremadeofsandwichstructureswithaluminium hon-eycomb.However,fromtheMirage4000onwards,thefinwasbuiltin monolithicself-stiffenedlaminatemadeofT300-914carbon-epoxyplies

[147].

Asfaraslargecivilaircraftareconcerned,theBoeing747(firstflight February9th,1969)isdesignedwithalargeproportionofsandwich(see

Fig.18).Ithasabouthalfthesurfaceofthewing,includingtheleading andtrailingedges,madeofglassfibreandNomexhoneycomb,which isalsousedforthelargebellyfairing.Mostoftheflapsaremadewith thesamesandwichbutaluminiumhoneycombandskinsarealsoused. However,thewingbox,theverticaltailboxandthefuselagearestill madeofaluminiumstiffenedpanels.

Theuseofcompositeshassinceincreasedsignificantlywith,in par-ticular,theATR72(firstflightonOctober27th,1988),whichwasthe

firstcivilaircrafttohaveacarbonprimarystructure(thewingbox) cer-tified[36].Italsoincorporatesmanycompositesandwichstructuresfor secondarystructuresbutwithawidevarietyofskins:glass,Kevlarand carbon(seeFig.19).

ThesesolutionshavealsobeenappliedintheA320,A330andA340 programmes. However,in themost recent programmes, the propor-tionofsandwichmaterialsinsecondary structureshasbeen decreas-ing,as shown in Fig.20. Forthe A380,theBoeing 787 or the Air-busA350 only thebellyfairing, thenacelles,the frontlandinggear doors,someaileronsandtherudderarestillmadewithsandwich struc-tures[144,145].Theotherpartsareself-stiffenedmonolithicstructures, whichcertainlypresentaneconomicadvantagetoday.

5. Primarycompositesandwichstructures

Themost famous aircraftinsandwich structureis theBeechcraft Starship,whichmadeitsfirstflightonFebruary15th,1986[10,149– 152].Itwasthefirstinitscategoryandithasgreatlyhelpedtoreclaim thefieldandcontributedvaluableexperience,whichhasbeenbeneficial

notonlytoBeechcraftbutalsototheentireaeronauticalindustry.As KevinRetzpointsout[152]:“Only53Starshipswereproducedbefore productionendedin1995.Thiscouldnotbeconsideredafinancially productiveprogrambutitgaveRaytheon/Beechaverysound founda-tiontobuildon.BeechusedthistowinC17contracts,andonitsother aircraft.ForRaytheontheStarshipprovedtobeabonanzaof knowl-edge”.TheStarshipconfigurationwasoriginallyconceivedin1982by BurtRutanandwentintoproductionin1988[151].Itwascertifiedon June14th,1988andwasthefirst“allcomposite” aircraftcertifiedbythe FAA,fouryearslaterthanoriginallyscheduled.About72%ofthemass ofitsstructurewasintheformofcompositematerial,mainlyepoxy car-bonskinsandNomexhoneycombcoresinHEX,OXorFLEXforms.The densitywas48kg/m3butitcouldreach72,90or144kg/m3locally. Thefuselagewasmadeupoftwomanuallydrapedhalf-shells,whilethe wingcoverswere16mlongone-shotpieces.Itisinterestingtoseethe numberofteststhatwerenecessarytocertifythisaircraft[149]:

•Fullscalestatictests...99

•Environmentaleffects,fullscaleandcomponents...29

•Damage tolerance, full scale and components (9 × 2 lifetime)... 360000h •Residualstrengthafterfatigue...18

•Jointstesting...335 •Parts...20 •Bucklingpanels...39 •Delaminationpanels...72 •Impactpanels...160 •Solareffect...47 •Couponlevel...8000 Thenumberoftests,andthusthecostofcertification,wasveryhigh. Moredetailsonthesecertificationtestsaregivenin[10].Inthispaper,a typicalstackingtechniquemergingunidirectionaltapeandplainwave is shown(seealsoFig.22).Notealsothepresenceofacoppermesh onthesurfaceforlightningstrikes.Thecertificationprocessisalmost thesametodaywithseveraltensof thousandsoftests fortheA350. ThedevelopmentwasdifficultbecausetheFAAregulationsondamage toleranceevolvedduringtheprogramme,generatingdelays.Inaddition, aprematurefailureoccurredduringstructuraltestingandthestructure thereforehadtobemodifiedindepth.Theentiremanufacturingprocess alsohadtobecertified[151].

However,manylessonswerelearnedfromthisexperienceandled tothesuccessoftheRaytheonPremier.Thefuselageissimilartothat of theStarship(see, forexample,twotypicalstackingsequencesfor thesetwoplanesinFig.22[10]) but,fortheRaytheonPremier,itis obtainedbyAdvancedFibrePlacement(AFP).Inaddition,the manu-facturingmethodwasstudiedwellbeforethecertificationprocessby combiningtheexperiencegainedontheStarshipandthatoftheAFP ma-chinemanufacturer(Cincinnati).AccordingtoKevinRetz[152]:“The entirefuselageismadeintwopiecesandweighslessthan600lbs(272kg); thisisaweightsavingofover20%whencomparedwithametallicaircraft.

Fig.19. ATR72compositematerials.

Fig.21. Left:BeechcraftStarshipNC51infligth,Right:Fuselageunderconstruction(from[150]).

Fig.22. Typicalstackingsequenceforpressurizedfuselage: (a)forBeechcraftStarship(b)forRaytheonPremier (repro-ducedfrom[10]).

Withthecombinationofadvancedfibreplacementandlargehand layed-upparts,thePremierIhasreducedthepartscountfrom16000partsdown toaround6000partsfortheentireaircraft,areductionofover60%.By usingfibreplacement,materialscraperateisbelow5%comparedto50% fora hand-lay-upfuselage...production costswerereducedby 30% for

thefuselage.Toseethisfactorclearly,ittakes4technicianslessthanone weektoproducetheentirefuselage”.However,thewingofthePremier remainsinaluminium.Otheraircrafthavefollowedthisexample,such astheADAMAircraftA500&A700,theCIRRUSSR20&SR22,which arealsobusinessjets.Theseprogrammeshavebenefitedfromthedata

Fig.23. Transportaircraftwide-bodyfuselage (Repro-ducedfrom[156]).

bankofmaterialscertifiedbytheFAAthroughanAGATE(Advanced GeneralAviationTransportExperiments)programme.Otherplanesof thesamekindhaveprobablybeendevelopedaroundtheworld.In Eu-rope,aresearchprogrammecalledFUBACOMB(FUllBArrelCOMPosite) tookplaceintheearly2000sandstudiedacompositesandwich fuse-lageproducedbyAFPforbusinessjets[153,154].Theobjectivesofthe programmewere:

• TodevelopfibreplacementknowledgeandcapabilityinEurope • Tovalidate innovativeconceptsforcompositefuselage structures

withhighintegrationandautomatizationthroughfibreplacement technology

• Todemonstrateaffordable,large,complexcompositetooling • Todevelopinprocessmonitoringandvisualizationtechniquesfor

fibreplacement

Theresultwasafullyintegrated,fullcompositesandwich,front fuse-lage,inparticularthecanopy(firstofitskindinEurope).However,to thebestoftheauthors’knowledge,therehasbeennopractical appli-cationofthisprogrammesince,unlikeRaytheon,somemanufacturers believethatgreatermasssavingsarepossiblewithcompositewings.

Theintroductionofsandwichstructuresforprimarystructureson largeaircrafthasnotprogressedbeyondtheframeworkofAmerican re-searchprogrammes.TheACT(AdvancedCompositeTechnology,[155– 158])programmestudiedaciviltransportaircraftfuselagetypeinthe 1990s.A“fourshellconcept” structurewasstudiedand,accordingto thecriteriaofthetime,theresultwasaskin/stringerconfigurationfor thecrownquadrantandasandwichconstructionforthekeelandside quadrants(seeFig.23).Itshouldbenotedthatthesestudiesdidnotlead

toapracticalapplication;thefuselagesoftheA350andB787arenotin sandwichconstruction(seeFig.20).Otherstudiescarriedoutunderthe HSR(HighSpeedResearch)programme[158]inthe1990sincludeda fuselageandawingofasupersoniccivilsandwichaircraftusingskins inIM-7/PETI-5.PETI-5isaNASA-patentedpolyimideresin.

Sandwich technology and its advantages have finally spread to lightaviationwiththeaircraftmanufacturerElixirAircraftbasedinLa Rochelle(France),whichreceivedEASACS23certificationonMarch 20th,2020foritstwo-seatercarbonaircraftcalledthe“Elixir"[159].The

Elixirwasdevelopedaroundsandwichtechnologyappliedtothe One-Shotproductionmethod.Thistechniqueconsistsofdesigningand man-ufacturingcomplexelements(suchasawing)inonepartandone oper-ationwithoutcomplexstructuralassemblies.TheOne-Shottechnology usedherewastakenfromcompetitivesailing,whereithasbeeninuse formorethan15years.Thedevelopment,couplingsandwich technol-ogywithOne-Shotandtheinfluenceofcompetitivesailingdesign,has allowedthegeneralizationofmonoblockstructuresinthisaircraft(see

Fig.24).Innovativedefinitionslimitingthenumberofassemblieshave beenintroduced,andbreakwiththetraditional“blackmetal” widely usedinaviationcompositedesign.Forexample,thewingoftheElixir ismadewithoutribsorspars.Traditionalmechanicalassembly meth-ods,suchasscrewing,rivetingandgluingareeliminated.Thecomplete wing(fullspan)isentirelyinOne-Shotandmonoblock.Thefuselage, canopyarchandcontrolsurfaces(ailerons,flapsandverticalstabilizer) arealsomadeinOne-Shot.Themainadvantageofsuchanapproachis thedrasticreductioninthenumberofelements.Asaresult,theaircraft consistsofonly600parts,againstmorethan10,000withconventional light aircraftmetallicconstruction.Fewerpartsandfewerassemblies

Fig.24. (a)The"Elixir",(b)One-Shotfuselage,(c)CrosssectionalviewoftheOne-Shotwing.

meanfewerpotentialfailures.Thus,safetyisenhancedbythe simplic-ityofthestructureandperformanceisimprovedbythereducedweight. ElixirAircraftpresenttheElixirastheOne-Shotcarbon4thgeneration oflightaviation,after1stwoodandcanvas,2ndaluminiumandrivets, and3rdcompositesandaluminium[160].

Forthepast25years,ScaledCompositesInc.,ledbyBurtRutan,has beeninvolvedinthedesignandfabricationofmanyall-composite proof-of-conceptandcompetitionaircraft.Theseaircraft,whicharemadein CFRP/foamsandwichconstruction,arenotincludedinthisreport.They includetheVoyager,whichwasthefirstplanetoflyaroundtheworld withoutrefuelling,thePondRacer,theNASAAD-1obliquewing re-searchaircraft,thescaledemonstrationT-46,andtheStarship[151].

In conclusion, sandwich structures are now well established as primary structures for business aircraft thanks to their excellent cost/reliability/weightratio.Thissolutionisalsostartingtospreadin generalaviation. However, theshare of sandwichstructureshas de-creasedonthecommercialaircraftandstiffened compositesolutions arepreferred.

6. Thecaseofhelicopters

Helicoptersmustbetreatedseparatelybecausethestressesactingon thefuselagesareoftheorderofahundredN/mm,whereastheyare10 timeshigherforbusinessjetsandhelicoptersarenotpressurized.Onthe otherhand,thevibratoryconstraintsontheblades,theeconomic con-straintsforcivilhelicoptersortheoperationalconstraintsformilitary helicoptersledtocompositematerialsbeingadoptedveryearly,with ratesalmostat100%sincethe1990s.

Thefirstapplicationwasrotorbladesmadeofhoneycomborfoam coreswithfiberglassskins.ForVosteenetal.[151],thefirstcomposite sandwichbladesweretestedontheXCH-47byVERTOLin1959then, followingresearchprogrammes,allthe4,130steelbladesofthese he-licoptershadbeenreplacedbycompositebladesbythemid-1970s.For J.Cinquin[164],thelifespanofacompositehelicopterbladeislonger thanthelifespanofthehelicopter.Inaddition,thepossibilityof pro-ducingoptimizedaerodynamicshapes(camberedandtwistedsections) bymouldingmakesitpossibletoincreasethetake-off weightand re-ducefuelconsumption.Forexample,onanAS330,thetake-off weight isincreasedby400kg(+6%)andthegainincruisingflight by ap-proximately6%.Theuseofoptimizedstackingsequencesalsoallows thefrequenciesofthebladestobeclearlyseparated.Finally,thesaving inmanufacturingcostismorethan20%comparedtothecostpriceof thesameblademadeofmetallicmaterial.Therefore,inFrance,thefirst

compositebladesbroughtintoserviceinserieswereontheGazelle he-licopterproducedbyAerospatiale(nowAirbusHelicopter)whosefirst flighttookplaceonApril7th,1967(seeFig.25).Thistechnologywas

thenappliedtoallthefollowingprogrammes.

Asstatedin[162],thistechnology,incombinationwith STARFLEX-typecompositerotors(see[8])hassignificantlyreducedoperatingcosts (13% for thePUMAhelicopter). Inaddition,compositetechnologies havealsoreducedthecostofowningandmanufacturinghelicopters, openingthemuptothecivilianmarketfromthe1970swith,in partic-ular,theEcureuil(firstflightonJune27th,1974),whichwasdesigned

withautomobiletechniquestoreducecostsandwhichalready incorpo-rated25%ofitsmassincomposite.Anotheradvantageofthese compos-itebladeswastheirtolerancetodamage,whichhadbeenemphasized sincetheirintroductioninthe1970s.Thenewdesignsmakeitpossible toabsorbhardprojectileslaunchedat150m/s,whetherinfrontalor razingimpact.Theyarealsoresistanttothedetachmentoficeblocks fromthefuselageintheeventofflightsinicingconditions[165–167]. Today,researchismovingtowardslessnoisy“BlueEdge” typeblades, which havethestructuralcharacteristicof havingtwointernalspars

[168–170].

Therelativeproportionofcompositehasincreasedrapidlyin heli-copterstructures,withamajorityofsandwichstructures.TheEC135, broughtintoservicein1990alreadyincorporated50%compositeand theEC155“Dauphin” broughtintoservicein1997hadaround60%of itsstructureincomposite.ThemainpartofthestructurewasinNomex honeycomb/metallicskinsandwichstructures(inyellow,Fig.26) be-causethissolutioniseconomicalandhasbettervibratoryqualities, es-peciallyforthetailboom.Wecanalsonotethatthefloorwasmadeof honeycombwithaluminiumskinsbecauseitisalsoamore economi-calsolution.Theweightsavingwithacarbon/Nomexhoneycombfloor wouldbe20%butthecostwouldbeincreasedby70%.Ingeneral,the introductionofsandwichandcompositepartsintohelicopterstructures hasresultedinweightreductionsof15to55%andcostreductionsof 30to80%[164].InthelatestAirbusHelicopterprogramme,theentire structurewasmadeofcompositematerials.

ThemostinnovativecompositestructureiscertainlythatoftheTiger combat helicopter(firstflight,April27th, 1991).TheTigerwas the firstall-compositehelicopterdevelopedinEurope.Composite materi-alsareusedfor90-95%ofitsstructure[163],alargeproportionbeing inNomexhoneycombcorewithcarbonskins.Thisneedforlightness is duetooperational requirements,inparticulargreat manoeuvrabil-ityandahighrateofclimb.TheTigercanwithstand+4/-1g,which makesitoneoftherarehelicopterstobeabletoflyloops.Thestructure

Fig.25. Left:photoofhistoricalblades(thesmaller:Gazellehelicopter,thelarger:Pumahelicopter),from[161,162];Right:typicalsectionofablademanufactured atInstitutClémentAderwithafrontsparusedforimpactresearch[158–160].

Fig.26. StructureoftheEC155"Dauphin",reproducedfrom

[163].

weight/maximumtake-off weightratioisexceptionalevenifitcannot begivenhere.TheAH-64Apachehelicopterisareferenceinthisfield andtheTigerweighs40%less[171].

Despitethisextremelightness,theTigerwascertifiedwithfatigue testsonanewstructurethathaddeliberatelybeengivendamage (im-pactsandmanufacturingdefects)correspondingtoseveraltimesthe ser-vicelife,thenastatictestatextremeloadwasconductedonthesame structureandfinallyacrashtestwasperformed,againonthesame struc-ture.Intheeventofacrash,thehelicoptermustensurethesurvivalof thecrew,whichithasdoneinoperationalconditionsseveraltimes.The crashcalculationoncompositestructureswasextremelynewinthelate 80sandearly90s,yetthechallengewastakenupbyengineersofthe time.TigertechnologieshavealsobeenappliedtotheNH90transport helicopter,whichhasaslightlylowerrateofcomposites[163].

7. Futureofaeronauticsandwichstructures

Researchismainlyfocusedonstructuralimprovement,the integra-tionoffunctionsandthemultifunctionalityofsandwichstructures.

Re-gardingstructuralimprovement,manyinnovativecoreshavebeen de-velopedorrediscoveredinrecentyears.Abrief,non-exhaustivereview ofmanysandwichcorescanbefoundin [8]:foams,balsa,cork, ply-wood, honeycomb,andothershapes, latticecores(Kagome, tetrahe-dral,pyramidalorother),corrugated,folded,X-Cor,Hierarchical,Nap Core,Entangledcarbon fibresamongprobableothers.Only afewof thesepossibilitiescouldbeinterestingtoreplaceNomexoraluminium honeycombs,whichareveryefficient.Ullahetal.[172]studieda tita-niumkagomecorethatoutperformedtraditionalhoneycombsinshear andcompression.Thissolutionisproposedforailerons(seeFig.27). Italsohastheadvantageofbeingventilated,whicheliminatesthe po-tentialproblemsofmoistureingression.Areviewofthedifferent possi-bilitiesofthistypeofcore,inparticularfromthemultifunctionalpoint of view,wasmadebyHanetal.[176]. Foldedcores havealsobeen widelystudiedinrecentyears,especiallyintheVeSCo(VentableShear Core,[145,173])programme.Theyhavethemajoradvantageofbeing ventilatedbuttheycanalsobeoptimizedtoimprovethemanufacturing andtheskin/corebondingstrength[174],seeFig.27.These origami-typestructuresofferawidevarietyofmaterialsandpossiblepatterns

Fig.27. Top,kagomecoreforanaileron(reproducedfrom

[172]);bottom,foldedcoresolution(reproducedfrom[174]).

Fig.28. Definitionofamultifunctionalmaterialorstructure(from[184]).

[175].Theyhavealsobeenoptimizedforsoundabsorption,innacelles inparticular[174,177].Notethathoneycombcoreshavelongbeenused asaHelmholtzresonatorforsoundabsorption.However,todate,the foldedcorehasnotfoundapplicationsasfarastheauthorsknow, prob-ablyduetoamasspenalty.NASAX-Corcorehasinterestingmechanical characteristicsbutseemstobemainlyintendedforspaceapplications

[178,179].It isalsopossible tooptimize thedampingof astructure byaddingverydampingcore,suchasentangledcores,atkeylocations

[180].

Itisinterestingtorecallthedefinitionofamulti-functional struc-turegivenbyFerreiraetal.[184](seeFig.28):“Amultifunctional ma-terialsystemshouldintegrateinitselfthefunctionsoftwoormoredifferent componentsand/orcomposites/materials/structuresincreasingthetotal sys-tem’sefficiency”.Inthissense,manyofthesandwichstructurespresented in the previous sections are multifunctional in that, generally, they naturallyintegrate 2physical functionspassively:mechanics + ther-malinsulation(seeSection3);mechanics+stealth(seeFig.16); me-chanical+moistureingression,mechanical+acousticabsorption, me-chanical+vibrationdamping.Hermannetal.[145]andSascheetal.

[173]emphasizeanotherimportantfunctionthatsandwichstructures couldprovide:damagetolerance.Ofcourse,amoreresistantcorecanbe usedbutthissolutionisoftenalsoheavier.Anotherwayistooptimize thedesignofthecoresothatitcanactasacrackarrestor.Thisfunction hasbeenstudiedformarinestructures,forexample,in[181–183].The internalribofthebladeshowninFig.25actsasadamagearrestorin caseofhighvelocityimpact[165–167].

Inthepreviousexamples,theintrinsicpropertiesofthecoresorlocal designsareusedformultiphysicalapplicationslimitedtothe conjunc-tionoftwofactorsratherthanbeingmultifunctionalinthesystemsense. There areultimatelyfewreal multifunctionalapplicationswherethe sandwichisdesignedaprioritofulfilawidevarietyoffunctions.Rion etal.[17]studiedthepossibilityofusingsolarcellsasworkingskins fortheSolarImpulseproject(seeFig.29(a)).Smyers[185]presentsa droneapplicationofasandwichwhosecoreisanRFantennain addi-tiontoplayingastructuralrole.Boermans[186]presentsasandwich allowingsuctionoftheboundarylayerforaglider(seeFig.29(b)).The suctionisprovidedbyapumpandthefoldedsandwichisperforated.It shouldbenotedthat,inmanyotherareas,sandwichstructuresserveas mechanicalsupportsforotherfunctions:energyharvesting[187],heat exchange[188],microwaveabsorption[189,190],integratedelectronic device[192],batteryintegration[193–195],dampingwithresonator in-tegration[191],fireprotection[196],or(typicallyBalsacorefornaval militarystructures),crash[197].

Aspartofthe“SUGAR” (forSubsonicUltraGreenAircraftResearch) programmetheGeneralElectric,GeorgiaTech,Cessnateamproposed theconceptof“protectiveskin” showninFig.30[198].Thesolution isanasymmetricsandwichfromthefunctionalandmechanicalpoint ofview.Theinnerskinplaysthestructuralrole,thecoreandtheouter skinintegratealargenumberoffunctions,including:aerodynamic opti-mization,acousticandthermalinsulation,protectionagainstlightning strikes,moistureinsulation,damageprotection,andinstallationofice protectionsystems,wires,antennasorothersensors.

Inconclusion, arealisticprospecton fuselagesis proposed byA. Tropisin[199]:“...,thenextgenerationoffuselagesmustcombinethe2 pre-viousdomains(“loadcarryingstructureplusdamagetolerance/robustness”) plusa“multifunctionalcapability” i.e.electricalconductivity,...In conclu-sion,todefineafullyoptimizedfuselage,multifunctionalmaterialsmustbe

Fig.29. Twoexamplesofmultifunctionalsandwichstructures (a)from[17]and(b)from[186].

Fig.30. GE/GeorgiaTech/CessnaProtectiveskin con-ceptintheSUGARProgramme(from[198]).

furtherdevelopedcombinedwithimproveddamagetolerance/largedamage capabilitiesproperties.Itwillbethechallengeofthenextdecade”.

8. Conclusions

Fromthe1920sandTheodoreVonKarman’spatent,uptothepresent day,sandwichstructureshavebeenpresentinaeronauticsforalmost 100years.Despitetheirundeniablequalities,theircomplexityfroma mechanicalpointofview,togetherwiththechallengesofmanufacturing andcontrol,sloweddowntheirintroduction,whichwasdoneina care-ful,gradualmanner.Thedifficultiesencounteredincertainprogrammes allowedengineerstolearnalotandthenbouncebacksuccessfullywith

newapplications.Today,sandwichstructures,mainlywithcomposite skinsandNomexhoneycombs,dominatelighthelicopterstructuresand havesomeapplicationsinbusinessjetswithoutbeinggeneralized. De-spitethedifficultiesofcertifyingasandwichstructure,smallinnovative companies,suchasElixirAircraft,produceall-sandwichpassenger air-craftinOne-Shot.Incontrasttheiruseistendingtodecreasein single-ordouble-aislecivilaircraft,whereitislimitedtosomesecondary struc-turesandcommercialequipment.

Thedesign ofa sandwichcompositestructureis partof the gen-eral difficultyof designingcomposite structuresdetailedin theGAP (acronymofGeometry,Architecture,Process)method[8].In particu-lar,thechoice,notonlyofmaterialsbutalsoofarchitectures,isvery

vastandnorealmethodologyhasbeenestablished.However,this “hy-perchoiceof materialsandarchitectures” canprovetobe an advan-tageintheintegrationoffunctions,whichwillbethefutureof compos-iteaeronauticalstructures.Beyondmulti-physicalsolutions,sandwich structurescouldenablearealintegrationofsystemstobeachieved,as isbeginningtobeanalysedinthespacedomain[200]andproposedin theSUGARprogramme.Thiswillrequireadaptationoftheindustrial organization.Thelaunchofnewresearchprogrammescanprovideand experiencethisnewparadigmandencouragelearninganddialogue be-tweenspecialistsinsystemsandstructures.

DeclarationofCompetingInterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompetingfinancial interestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedtoinfluence theworkreportedinthispaper.

Acknowledgements

Thispaperisaresultof25yearsofexperienceinthefieldof aero-nauticcompositestructuresattheInstitutClementAder,Toulouse,and strongrelationshipswiththeAircraftIndustry.Thefirstauthorwishes tothankmorespeciallyhisformeradvisorsduringhisPhDwith Euro-copter:Jean-PierreJaouen(Nowretired)andAlainCrouzet(now Da-her).TheauthorsalsothanktheirPhDstudentswhohavecontributed totheknowledgeofsandwichstructures:JaimeRivera(FuerzaAerade Chile),YulfianAminanda(nowUniversitiTeknologiBrunei), Phachara-pornBunyawanichakul(KasetsartUniversity,Thailand),LaurentMezeix (BuraphaUniversity,Thailand),JohnSusaisnathan(Universityof Ne-brija,Spain)andJuandeDiosRodriguezRamirez.SpecialthankstoJ. Leibacher(WebmasterofSoaringMagazinearchiveandprofessoratthe UniversityofTucson)andNicolasMahuet(HeadofengineeringofElixir Aircraft)fortheirhelp.

References

[1] N.J. Hoff, S.E. Mautner , Sandwich construction, Aeronaut. Eng. Rev. 3 (1944) 1–7 .

[2] H.G. Allen, Analysis and Design of Structural Sandwich Panels. Pergamon Press, Oxford 1969

[3] F.G. Plantema , Sandwich Construction, John Wiley & Sons, New-York, 1966 .

[4] D. Zenkerts, The Handbook of Sanwdich Construction. E-MAS Publishing, London 1997

[5] C. Kassapoglou , Design and Analysis of Composite Structures (with application to aerospace structures), Wiley, Chichester UK, 2010 .

[6] L.A. Carlsson , G.A. Kardomateas , Structural and Failure Mechanics of Sandwich Composites, Springer, Dordrecht NL, 2011 .

[7] D. Gay , Composite Materials Design and Applications, CRC press, Boca Raton FL, 2015 .

[8] F. Neveu, B. Castanié, P. Olivier, The GAP methodology: A new way to design composite structure Mater. Des. 172, 107755, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107755 .

[9] D. Guedra-Degeorges , P. Thevenet , S. Maison , Damage Tolerance of Aeronauti- cal Sandwich Structures, in: A. Vautrin (Ed.), Mechanics of Sandwich Structures, Kluwer Academic Publisher, 1998, pp. 29–36 .

[10] J. Tomblin, T. Lacy, B. Smith, S. Hooper, A. Vizzini, S. Lee, Review of damage tolerance for composite sandwich airframe structures, FAA Report DOT/FAA/AR- 99/49, 1999.

[11] B. Castanié, J.-J. Barrau, J.-P. Jaouen, Theoretical and experimental anal- ysis of asymmetric sandwich structures, Comp. Struct. 55 (2002) 295–306, doi: 10.1016/S0263-8223(01)00156-8 .

[12] B. Castanié, J.-J. Barrau, J.-P. Jaouen, S. Rivallant, Combined shear/compression structural testing of asymmetric sandwich structures, Exp. Mech 44 (2004) 461– 472, doi: 10.1007/BF02427957 .

[13] B. Castanié, Contribution à l’étude des structures sandwichs dissymétriques, PhD Supaéro 2000. http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/4282/ .

[14] J. Zhang, Q. Qin, X. Han, W. Ai, The initial plastic failure of fully clamped geo- metrical asymmetric metal foam core sandwich beams, Comp. Part B 87 (2016) 233–244, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.10.027 .

[15] J. Deng, A. Peng, W. Chen, G. Zhou, X. Wang, On stability and damage behavior of asymmetric sandwich panels under uniaxial compression, J. Sandwich Struct. Mater. On line (Feb 2020), doi: 10.1177/1099636220905778 .

[16] A. Fink, C. Einzmann, Discrete tailored asymmetric sandwich structures, Comp. Struct. 238 (2020) 111990, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.111990 .

[17] J. Rion, Y. Leterrier, J.-A.E. Månson, J.-M. Blairon, Ultra-light asymmet- ric photovoltaic sandwich structures, Comp. Part A 40 (2009) 1167–1173, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.05.015 .

[18] K.E. Evans, The design of doubly curved sandwich panels with honeycomb core, Comp. Struct. 17 (1991) 95–111, doi: 10.1016/0263-8223(91)90064-6 . [19] S. Smidt, Bending of curved sandwich beams, a numerical approach, Comp. Struct.

34 (1996) 279–290, doi: 10.1016/0263-8223(95)00149-2 .

[20] O.T. Thomsen, J.R. Vinson, Conceptual design principles for non-circular pressurized sandwich fuselage sections – a design study based on a high- order sandwich theory formula-tion, J. Comp. Mater. 36 (2002) 313–345, doi: 10.1177/0021998302036003468 .

[21] N.J. Hoff, S.E. Mautner, The buckling of sandwich type model, J. Aeronaut. Sci. 12 (July 1945), doi: 10.2514/8.11246 .

[22] L. Fagerberg, D. Zenkert, Imperfection-induced wrinkling material fail- ure in sandwich panels, J. Sand. Struct. Mat. 7 (2005) 195–219, doi: 10.1177/1099636205048526 .

[23] E.E. Gdoutos, I.M. Daniel, K.A. Wang, Compression facing wrinkling of composite sandwich structures, Mech. Mater. 35 (2003) 511–522, doi: 10.1016/S0167-6636(02)00267-3 .

[24] L. Fagerberg, D. Zenkert, Effects of Anisotropy and Multi-axial Loading on the Wrinkling of Sandwich Panels, J. Sand. Struct. Mater. 7 (2005) 177–194, doi: 10.1177/109963205048525 .

[25] B.K. Hadi, F.L. Matthews, Development of Benson-Mayers theory on the wrin- kling of anisotropic sandwich panels, Comp. Struct. 49 (2000) 425–434, doi: 10.1016/S0263-8223(00)00077-5 .

[26] R. Vescovini, M. D’Ottavio, L. Dozio, O. Polit, Buckling and wrinkling of anisotropic sandwich plates International, J.Eng. Sci. 130 (2018) 136–156, doi: 10.1016/j.ijengsci.2018.05.010 .

[27] K. Niu, R. Talreja, Modeling of wrinkling in sandwich pan- els under compression, J. Eng. Mech. 125 (1999) 875–883, doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(1999)125:8(875) .

[28] K. Yu, H. Hu, S. Chen, S. Belouettar, M. Potier-Ferry, Multi-scale techniques to analyze instabilities in sandwich structures, Comp. Struct. 96 (2013) 751–762, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2012.10.007 .

[29] M.A. Douville, P. Le Grognec, Exact analytical solutions for the local and global buckling of sandwich beam-columns under various loadings, Int. J. Sol. Struct. 50 (2013) 2597–2609, doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2013.04.013 .

[30] L. Léotoing, S. Drapier, A. Vautrin, Nonlinear interaction of geometrical and mate- rial properties in sandwich beam instabilities, Int. J. Sol. Struct. 39 (2002) 3717– 3739, doi: 10.1016/S0020-7683(02)00181-6 .

[31] J. Bertolini, B. Castanié, J.J. Barrau, J.P. Navarro, C. Petiot, Multi-level experimental and numerical analysis of composite stiffener debonding. Part 2: Element and panel level, Comp. Struct. 90 (2009) 392–403, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.002 .

[32] S. Zhang, J.M. Dulieu-Barton, O.T. Thomsen, The effect of temperature on the fail- ure modes of polymer foam cored sandwich structures, Comp. Struct. 121 (2015) 104–113, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.10.032 .

[33] B. Castanié, J-F. Ferrero , Nonlinear response of symmetric sandwich structures sub- jected to in-plane loads, in: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Sandwich Structures ICSS, Nantes, France, 2012, pp. 27–29. August 2012 .

[34] B. Castanié, J.-J. Barrau , J.-F. Ferrero , J.-P. Jaouen , Analyse non linéaire et struc- turale des poutres sandwichs dissymétriques, Revue des Composites et des Materi- aux Avances 10 (2000) .

[35] P. Minguet, J. Dugundji, P.A Lagace, Bucking and failure of sandwich plates with graphite-Epoxy face and various core, in: Proceedings of the 28th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Confer- ence, 6-8 April 1987 Paper AIAA-87-07, doi: 10.2514/3.45573 .

[36] A. Tropis , M. Thomas , J.L. Bounie , P. Lafon , Certification of the composite outer wing of the ATR72, J. Aerospace Eng. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G 209 (1994) 327–339 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1995_209_307_02 .

[37] J. Rouchon , Certification of Large Aircraft Composite Structures, in: Proceedings of the 17th ICAS, Recent Progress and New Trends in Compliance Philosophy, Stock- holm, Sweden, 1990 .

[38] E. Morteau, C. Fualdes. Composites @ Airbus, damage tolerance methodology. FAA Work-shop for Composite Damage Tolerance and Maintenance, Chicago IL, 2006.

https://www.niar.wichita.edu/niarworkshops/Portals/0/Airbus%20Composites %20-%20Damage%20Tolerance%20Methodolgy%20-%20Fualdes.pdf?ver = 2007- 05-31-095449-530 Accessed 05/26/2020

[39] J.B. Chang, V.K. Goyal, J.C. Klug, J.I. Rome, Composite Structures Damage Toler- ance Analysis Methodologies. NASA/CR-2012-217347

[40] T.D. McQuigg. Compression After Impact Experiments and Analysis on Honeycomb Core Sandwich Panels with Thin Facesheets. NASA/CR–2011-217157.

[41] J.S Tomblin, K.S. Raju, J. Liew, B.L Smith. Impact Damage Characterization Damage Tolerance of Composite Sandwich Airframe Structures. FAA Report DOT/FAA/AR-00/44, 2000.

[42] J.S Tomblin, K.S. Raju, J.F. Acosta, B.L. Smith, N.A. Romine, Impact Damage Char- acterization And Damage Tolerance Of Composite Sandwich Airframe Structures- phase II. FAA Report DOT/FAA/AR-02/80, 2002.

[43] J.S Tomblin, K.S. Raju, G. Arosteguy. Damage Resistance and Tolerance of Com- posite Sand-wich Panels —scaling Effects. FAA Report DOT/FAA/AR-03/75, 2003. [44] Serge Abrate , Bruno Castanié, DS Yapa , Rajapakse, Dynamic failure of composite

and sandwich structures, Springer, Dordrecht NL, 2012 .

[45] S. Heimbs, Virtual testing of sandwich core structures using dynamic finite element simulations, Comput Mater Sci 45 (2009) 205–216, doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2008.09.017 .

[46] Y. Aminanda, B. Castanié, J.-J. Barrau, P. Thevenet, Experimental analysis and modeling of the crushing of honeycomb cores, App. Comp. Mat. 12 (2005) 213– 217, doi: 10.1007/s10443-005-1125-3 .

![Fig. 5. Damage tolerance policy (reproduced from [10] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/6.892.58.505.88.678/fig-damage-tolerance-policy-reproduced.webp)

![Fig. 8. Edge junctions (from [57] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/7.892.63.525.84.502/fig-edge-junctions-from.webp)

![Fig. 10. Failure pattern of an aeronautic insert used for land- land-ing gear door under pull-out loading (reproduced from [76] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/8.892.72.525.566.808/fig-failure-pattern-aeronautic-insert-used-loading-reproduced.webp)

![Fig. 11. Schematic of a scarf repair applied to a sandwich component. Top: top view, bottom: section view (Reproduced from [103] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/9.892.59.529.82.537/schematic-scarf-repair-applied-sandwich-component-section-reproduced.webp)

![Fig. 12. Glider wood sandwich construction (reproduced from [123] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/10.892.67.422.82.638/fig-glider-wood-sandwich-construction-reproduced.webp)

![Fig. 13. "Brodeau" process, 1934 [125] .](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/11.892.57.745.82.606/fig-brodeau-process.webp)

![Fig. 16. Composite Honeycomb areas of the SR 71, shown in black (from [139] and [140] ).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/11616959.303901/12.892.56.518.452.822/fig-composite-honeycomb-areas-sr-shown-black.webp)