Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Technical Paper (National Research Council of Canada. Division of Building

Research), 1963-09-01

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC : https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=fd608ca0-1f5d-4f43-9b18-c69e1b4b2de3 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=fd608ca0-1f5d-4f43-9b18-c69e1b4b2de3

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/20359053

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Manpower utilization in the Canadian construction industry: a pilot

study

Ser TH]. N2t-t2 - - / n l . r ) o e . 2 BI,DG

lilltiltilil

22uiliuuuru|uu

lillru||lu

b*WTe'

NATIONAT RESEARCH COUNCIL

CANADA

DIVISION OF BUILDING RESEARCH

MANPO\T/ER UTILIZATION IN THE

CANADIAN CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

(A Pilot Study)

by

DAVID C. AIRD ANALY7ED

Division of Industrial Administration Universitv of British Columbia

Technical Paper No. 156 of the

Division of Building Research

Ottawa, September

1963

FORE\T/ORD

The Division of Building Research of the National Research Council is pleased to publish this report by Professor David Aird of the University of British Columbia on the application of work-study techniques to the construction industry.

Efficiency on construction jobs has been a continuing matter of interest and concern to the Division of Building Research since its earliest days. A good deal of information on this important practical aspect of building research has been accumulated and the Division is in touch with actual research work in this field in other countries. Owing to lack of the necessary staff it has not yet been possible, however, for the Division to embark upon any work of its own in this important field.

It is for this reason, and also because of its obvious importance to all contractors, general and trade, throughout Canada, that the Division is glad to have the opportunity of publishing this record of Professor Aird's work. The report presents a useful introduction to the concept of work-study, a helpful bibliography, and an excellent example of the results that can be obtained by the careful applica-tion of the method on a variety of small construcapplica-tion operaapplica-tions. The Division as-sisted Professor Aird with his preliminary studies and in the completion of his report but the contents and conclusions of the report are his own.

The Division looks forward to embarking upon work in this field just as soon as it has the necessary staff. It anticipates making full use of the pioneer work of Professor Aird and his associates. It is hoped that the report will be similarly useful to contractors in Canada who are anxious to improve the efficiency of their own site operations.

If there is one lesson above all to which this report points clearly, it is the vital importance of proper training in the elements of good management for foremen and supervisors on construction contracts. The best and most carefully prepared over-all plans for construction work can be of only partial avail unless the immediate supervisors of labour on the job have a proper conception of their own responsibility for job management and for the elimination of waste on the job, as is so clearly brought out by this report.

It may, therefore, be helpful to mention in conclusion that the Canadian Construction Association, through its Committee on Research and Education, has under active consideration as this report goes to press the development of proper training courses for job foremen and supervisors. The Division hopes that the publication of this report will make some contribution towards this desirable nationwide effort to improve still further the efficiency of building in Canada.

Ottawa

September 1963.

R. F. Irgget, Director, DBR/NRC.

ACKNO\TLEDGEMENT

This study has only been possible because of the interest, support, and co-operation demonstrated by the scores of persons with whom the writer has been associated during the course of this research.

First of all, the financial support of the following organizations is gratefully acknowledged, for without this the project could not possibly have been under-taken in the form and scope which has been realized:

1. The Institute of Industrial Relations, University of British Columbia. 2. The Leon and Thea Koerner Foundation (Vancouver).

3. The School of Business, Queen's University. 4. The Department of Labour, Ottawa. 5. The Canadian Construction Association.

In addition, the Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration (U.B.C.) and the Division of Building Research, National Research Council both provided aid and co-operation which has made possible the publication of this research study. Thanks are due, as well, to friends and colleagues within these and other institutions who have been particularly helpful; outstanding of the many so included are Professor H. C. Wilkinson, Mr. C. R. Crocker, Dr. W. D. Wood, Dr. F. D. Barrett, Mr. Peter Stevens, Professor J. A. Sarjeant, Dr. T. Montague, Prof. A. W. R. Carrothers, and Professor L. G. Macpherson. Many student assistants have also been involved and particular thanks are due to Mr. Hershey Porte and Mr. Peter P. Ferlejowski for their contributions. Others have also been of substantial help, and to all of these unnamed associates is extended the writer's appreciation.

To the forty-odd persons associated with the Construction industry - in management, labour, and service relationships - who provided the stimulus of their thoughts, suggestions, and informative advice through countless hours of interview, the writer directs special thanks; their collective contributions are the heart of the study.

Approximately one-hundred other construction executives and trade union officials co-operated in supplying information which has been incorporated into this research. They are herewith thanked for their co-operation and interest in answering the rather long questionnaires sent to them.

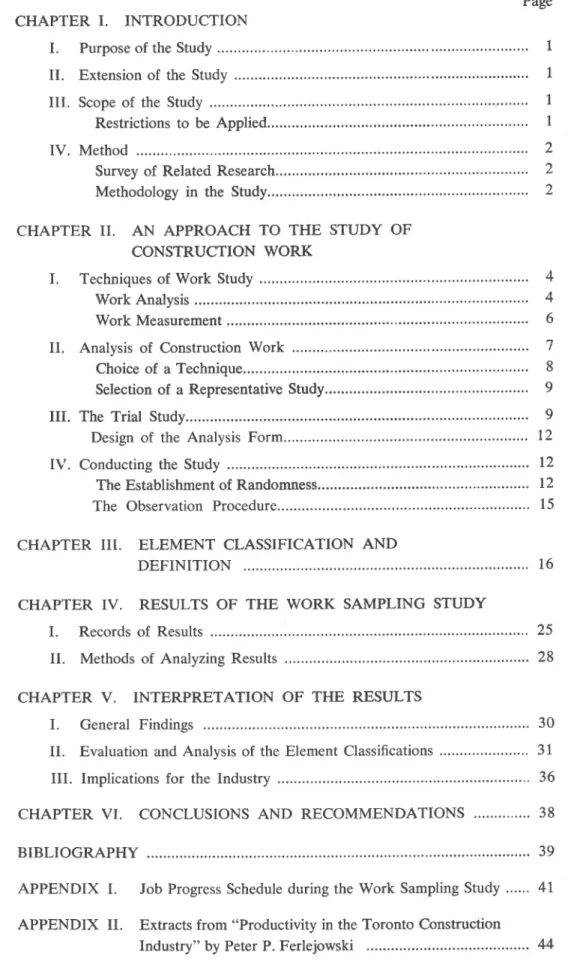

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION I. Purpose of the Study II. Extension of the Study III. Scope of the Study ...

Restrictions to be Applied... lV. Method

Survey of Related Research... Methodology in the Study

CHAPTER II. AN APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF CONSTRUCTION WORK

I. Techniques of Work Study ... Work Analysis ... Work Measurement

II. Analysis of Construction Work

Choice of a Technique... Selection of a Representative Study... III. The Trial Study.

Design of the Analysis Form... IV. Conducting the Study ...

The Establishment of Randomness... The Observation Procedure...

APPENDIX APPENDIX Page 1 1 1 I 2 2 2 4 4 6 7 8 9 9 l 2 t 2 t 2 1 5 CHAPTER IIT. ELEMENT CLASSIFICATION AND

DEFINITION ... 16

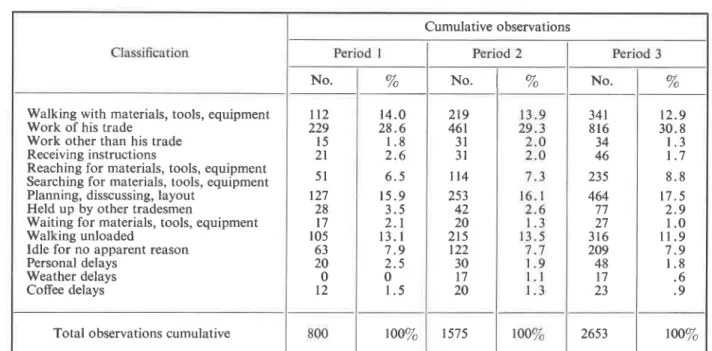

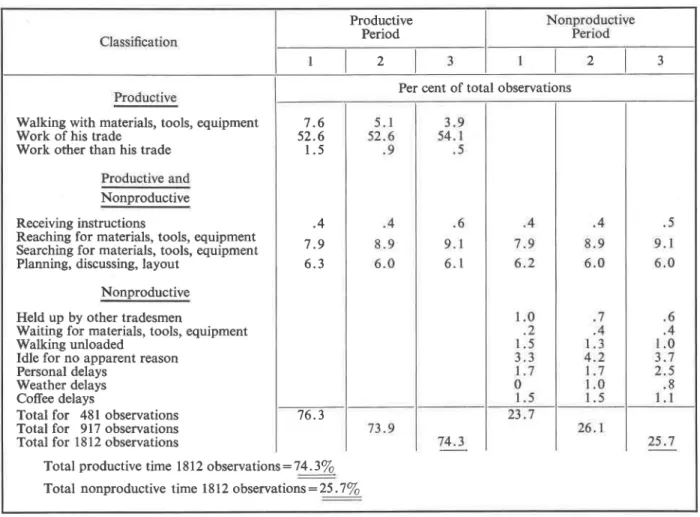

CHAPTER IV. RESULTS OF THE WORK SAMPLING STUDY

I. Records of Results ... 25 II. Methods of Analyzing Results ...'...'...'... 28 CHAPTER V. INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS

I. General Findings

II. Evaluation and Analysis of the Element Classifications ... III. Implications for the Industry

CHAPTER VI. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY

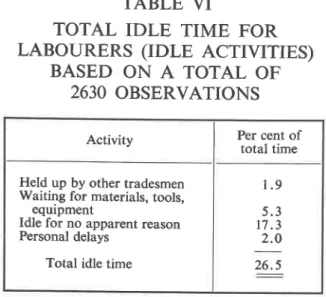

Job Progress Schedule during the Work Sampling Study ... Extracts from "Productivity in the Toronto Construction Industry" by Peter P. Ferlejowski

30 3 I 3 6 3 9 4 l I . II. 44

CHAPTER I

I. PURPOSE OF THE STUDY An investigation into effective utilization of labour in the construction industry was initially envisaged in 1959. The staff of the Department of Industrial Administration, University of British Columbia, became interested in this subject large-ly as a result of the widelarge-ly-publicized industrial disputes which took place in the Province during the previous year.

Construction appears to be of special import-ance in an economy such as that of British Colum-bia which has witnessed vast new projects develop-ing in the past decade. The fact that the Industry has sometimes been subject to cyclical influences and too often to seasonal effects of very great magnitude is obvious to most observers. Oft-quoted reports of make-work practices, high wages, jurisdictional disputes, and similar phenom-ena appeared to be in contrast (to a layman) to the wonderful and awe-inspiring accomplishments of engineering and contemporarily designed struc-tures.

What was the true situation in the construction industry? With curiosity aroused, and the air filled with allegations and counter-charges, the writer and his colleagues turned their attention to an attempted determination of the underlying facts. It quickly became apparent that little definitive information was available on the Cana-dian construction industry.

Interest was primarily in the direction of con-struction work, and what that involved. We wanted to learn, for example, what skills are in-volved; how were the workmen managed; what processes were used in planning these projects and how did each individual know exactly what his job was; how hard did the craftsman work, and for how long; did his income reflect what appeared to be high wages, and was it proportion-al to his efforts?

At the time we had two resources available which would enable us to undertake investigations which might lead to some of the answers which we sought. The first of these was a relatively new form of work analysis technique known as "Work Sampling". This method appeared to be highly

appropriate to permit the gathering of a signifi-cantly large body of information about construc-tion work in a relatively limited period of time. The second available resource was a small group of able and interested student assistants who shared enthusiasm for the studv.

INTRODUCTION

II. EXTENSION OF THE STUDY The core of this report is comprised of the findings from the pilot study which was under-taken in Vancouver. This series incorporated four actual investigations (abbreviated results of the other three are included later in this report). Upon release of some of the tentative results in June of 1962, considerable interest was produced among members of the Toronto Construction Association and staff of the School of Business of the Universi-ty of Toronto. From this, a further series of studies were conducted in the Toronto area during the period from June to September 1962' A summary of these results is given in Appendix II.

III. SCOPE OF THE STUDY The investigations reported upon in the follow-ing chapters are of a basic nature. The immediate purposes of the study were: (1) to establish au-thenticated facts concerning work in construction, and (2) to suggest the direction of further research and study. The definition of problems along with their future implications is therefore the goal of the present investigation.

Construction is a term with very broad con-notations covering many sub-industries extending from home repairs and alterations through to heavy engineering work such as dams and bridges. In between lie the areas of house-building, com-mercial, industrial and institutional construction, road-building, and heavy construction to mention only the major divisions.

It is clearly a practical impossibility to include, in one study, an analysis of considerations aftect-ing all aspects of the total industry. It is equally apparent that one study cannot adequately cover even one facet for the industry as a whole. Any useful study in depth must therefore be contained within artificially-imposed restrictive limits. The term artificially-imposed is used to indicate at the outset that although the effects of outside influen-ces may not be discussed in the study at hand, this is not to imply that they are of no consequence or l"rave been ignored.

RESTRTCTIONS TO BE APPLIED

Limitations upon the scope of a study such as this are three dimensional in nature. First of all, the writer must restrict the subject for analysis to narrow confines within the subject of construction operations so that he may, in the time available, carry out a penetrating worthwhile study. Second-ly, in this instance, it was necessary to focus upon certain sectors of the construction industrv which

might be considered to best represent or be typical of the industry as a whole. And lastly, due to the vastness of Canada, it was impossible to avoid compromise in an attempt to investigate and por-tray a geographical section representative of the industry at large.

The Subject From the outset the concern was to analyse the factors bearing on "work" in construc-tion. In this respect the emphasis was on manual work as performed by employees in the operation-al end of construction enterprises. Inherently this work is directly aftected by such influences as tools and equipment, materials, and supervision or management. As a consequence these factors were to be the subject of investigation as well, but only as they affected the work of employees.

The process of analysing the efficiency and effectiveness of manpower or labour utilization can be begun by asking a number of basic and obvious questions such as: How is the work being done? How long does it take? Where is it being done? Why is it being done? Who is doing the work? In the final analysis the answers to these and other questions lead almost inevitably to the discovery of more efiective methods of doing the work and resulting savings. If the output from useful labour can be improved then there can be increased efficiency from the labour resource. "Work", "manpower utilization", and "labour efficiency" are related terms, and serve to act as the subject for analysis and investigation in this study.

Sectors ol the Industry. In the previous section the subject of similarities and differences in work were mentioned. In the context of the construction industry itself, with its numerous subdivisions, the comparisons of work may be extended still further. The various sectors of the industry are different in terms of the amount of engineering involved, extent of equipment requirements, types of materials handled, and other matters. but in the restricted consideration of "work" all sectors are essentially similar in their environments, type of labour, and general conditions. Thus, although approaches and emphasis will depend upon the sector of the industry considered, discoveries and conclusions in one sector are implicitly of signifi-cance and relevance to all others.

Although the research studies, surveys, and interviews were largely concentrated in the com-mercial -industrial - institutioilal sector of the industry, representatives from all sectors of con-struction were consulted. These included manage-ment, union officials, and other persons involved in prime contracting, sub-contracting, materials supply, equipment, and other service functions. 2

It is thought that the study fairly represents the construction industry, and so may be of interest to all its members.

Geographical Representation. lt was not possible to obtain equivalent information from all geo-graphical regions due to the difficulties imposed by time and travel. As a consequence the results may be biased to some degree but not (it is thought) to diminish significantly the validity of the general conclusions developed in this study.

IV. METHOD

SURVEY OF RELATED RESEARCH

Despite the signiflcant role which construction plays in the Canadian scene there is a notable absence of any substantive research investigation into the management and operation of the indus-try. The report prepared for the Gordon Commis-sion by the Royal Bank of Canada, plus several unrelated briefs (compiled, for the most part, by the Canadian Construction Association - the in-dustry's official management body) constitute essentially all the published data on these features of the industry.

Much the same situation exists in the United States where, with few exceptions, the last major writings in the field were those of Frank G. Gil-breth, produced between 1908 and 19171. In recent years two significant contributions have been produced which are concerned with matters of labour productivity and management methods2. A number of recent papers indicate a growing awareness of, and interest in, this field.

On the other hand substantial research has been reported from several countries of Western Eu-rope, largely under the auspices of the European Productivity Agency. Some important literature has emanated from this source3.

METHODOLOGY IN THE STUDY

An introductory study such as this must com-mence by ascertaining the nature and extent of the problem from first hand observation. This study therefore rests heavily upon empirical ob-servations of construction work and analysis of the views of people connected with construction as determined by survey and personal interviews. No other approach was deemed feasible in view of the lack of published factual data.

lFrank G. Gilbreth, Motion.Srzdy (New York; D. Van Nostrand, 1911).

zUnited States Department of Labor, Cost Savings through S tandardization, Simplifications, Specialization, in the Buildins Industry, (Paris; O.E.E.C., 1954). Also see William Haber and Harold M. Levinson. Labour Relations and Productivity in the Building Trades (Ann Arbor; Bureau of Industrial Relations, University of Michigan, 1956).

The sequence of approach was as follows: 1. A series of four direct observation studies (one of which is reported upon in some detail herein) was conducted of construction workers on the job, in Vancouver. Each job thus analysed was broken into its elements which were then defined, with an emphasis on whether it was "productive" or "non-productive', work.

2. A similar study, covering twelve job sites, was undertaken in Toronto. Essentially the same approach and procedures were used as in Van-couver; a minor variation which proved to be of insignificant consequence was adopted in light of an apparent difference in conditionsa.

3. Following this, personal interviews were un-dertaken with forty-four representatives from management, unions, and the associated fields of construction, such as architects, owners, associa-tions. The interviews were held with representa-tives of all sectors of the industry, from coast-to_ coast,

4. Finally, all available related published ma-terials bearing on the subject were perused, and relevant information extracted.

The study is discussed in succeeding chapters as

follows:-In the second chapter the various available techniques of work study are considered. Work sampling, the method chosen, is related to alter-native possibilities, following which the specific problems of observing construction work are discussed. Finally, the pilot study is described.

The third chapter presents a breakdown of construction work into its elements. Each element is classified and defined, and supporting reasons are given in each case.

Chapter IV comprises a discussion of the work sampling studies, and interprets the implications found therein.

In Chapter V related knowledge is integrated with the results to establish hypotheses with res-pect to the means of improving the level of efficiency in construction work.

The final chapter summarizes the conclusions reached in this study, and makes recommendations for further research studies and analvses.

aMajor extracts_of the report ,.productivity in the Toronto Lonstructton Industry", including detailed findings, will be tound rn Appendix II of this report.

CHAPTER II

AN APPROACH TO THE

STUDY OF CONSTRUCTION \TORK

r. TECHNIQUES OF \rORK STUDY

Work study encompasses all facets of studying people at their jobs as well as the consideration of all factors affecting those jobs, such as ma-terials, tools and equipment, and working condi-tions. The term "work study" is somewhat

syn-major function of work studY.

The techniques of analysis comprising work study can be classified under two headings' The first of these is known as "work analysis" and the other as "work measurement". The common techniques of each, and especially those most appropriate to the study of construction work, will be briefly surveyed.

WORK ANALYSIS

Work Simplification. The study of job content must first of all consider what is "work", and just what it is that comprises the duties contained in the job. Some clarification of terms is first neces-sary in order to establish a common ground of understandin g: A iob is a collection of duties regularly assigned to an individual according to a well-established and easily-recognized pattern' Several people may simultaneously be employed at the same "job"; a common example would be the job of carpenter. A duty (or "task") is a specific portion of a job with its own character-istics which are easily identifiable. It is possible to break down a job into separate duties each of which could become the sole working function of a specialist. Sawing or hammering are duties that comprise part of the carpenter's job. A work element is, in turn, a further breakdown of a duty. The scope of definition for an "element" can vary broadly depending upon the type and nature of the analysis being undertaken' In the case of a carpenter, an element might be as large as a "search, reach, grasp and position wall panel", or as small as a single stroke of a hand-saw.

It is readily apparent that little difficulty would arise in re-arranging the duties which comprise any job, and in effect create or substitute new jobs for old. The analysis necessary prior to such action is obvious and easily accomplished by any supervisor. Some jobs may be improved or ad-justed in order to accommodate to specific

con-4

ditions at any time by just such means' This is somewhat arbitrary, however, as no attempt is made to analyze what goes into the various duties or tasks; that is, what elements comprise the duty, in rvhat order they happen, and how they are accomplished. It is in this more refined area that the sijnificant discoveries are to be found, and in order to pursue such an analysis some skill in the analysis technique is essential.

Work simplification, as the phrase implies, is the systematic determination of the elements contained in job tasks; the elimination of wasted effort, extra effort, or mis-directed efiort; and the re-arrangement of needed elements in their most advantageous order.

Until fairly recent times (circa 1900) the general consensus held that it was the right, expectation, and function of each individual worker to de-termine how he, personally, could best do his job' Management, by objective means or by intuitive judgment, simply assessed whether the individual was performing at a satisfactory level of output and ii he was deemed unsatisfactory in this regard the necessary disciplinary action was taken' Parti-cularly in the case of the "skilled" labourers it ,""-.d to be foreign to management to consider instructing a worker in better methods of perform-ing his job.

Research by F. G. Taylor, F. B' Gilbreth and Lillian M. Gi'lbreth, and others brought forward clear evidence of the ineffective working methods commonllt used by labour and of the great waste and extra effort involved in work performed in this manner. Although many of the concepts of the "scientific management" era are no longer acceptable, progressive organizations realize that worli methods are properly in the domain of management's interests. It is clear that often the improvements which can be incorporated into utry 1oU are not obvious until an analysis has been undirtaken by skilled specialists. Even sincere and intelligent workers with years of experierlce cannot be expected to have this analytical ability (although it would be quite wrong to assume that they are unable to contribute to methods im-provement). In short, management would be *tong to assume that any worker, without com-peteni analytical help' will naturally be able to perform "to the best of his ability".

Motion Analysis. The analysis of work elements is largely the study of body movements of human workers. The motions of the limbs as well as the

eyes, and their inter-related co-ordination must be observed and tabulated for analytical examination in order to determine better methods (i.e., work methods which result in greater output with less efiort and less fatigue). The first definitive work done in the field of motion analysis, or motion study, was carried out by the Gilbreths on the operations of the construction company which they owned. Studies were made of all types of work, but bricklaying and concrete work came in for special attention.

The Gilbreths' most important contribution to work study was concerned with their conception of universal elements of work. They reasoned that a detailed break-down of jcbs (comprising manual labour) would reveal a limited number of elements which would be found to be common to all jobs or tasks. Conversely, any task could be synthesized by combining, in a specific order, selected ele-ments chosen from a restricted variety of basic work units. These basic units of work were named "therbligs". There are, according to the Gilbreths, seventeen of them, such as grasp, transport empty, transport loaded, search, select, and hold, to name only a few. Thus in finding that any and all jobs or tasks could be described in terms of one or more of seventeen basic motions, it became a reasonably simple matter to analyze work. The procedure is merely one of (1) observing the job or task to be analyzed; (2) recording the basic motions or therbligs; (3) examination of each therblig according to an approach which was devised for each of the seventeen; (4) assessment of the relevance of each therblig to the task as a whole (considering not only the "work" but ma-terials, tools and working conditions as well); (5) elimination of any unnecessary therbligs; and (6) re-arrangement of the remainder into an im-proved method. The result of such a thorough analysis is a new work method which constitutes the "one best way" to perform the job.

Despite some shortcomings, this type of analysis has been adapted as a basic work study technique with outstanding success. The amount of detail may be extensive (justified under conditions of short-cycle, highly repetitive operations), or an abbreviated, broader analysis may be undertaken where applicable. The method of observation is of considerable importance inasmuch as the motions, if detailed break-downs are desired, are too brief for successful observation by the human eye accompanied by manual recording of the details. The Gilbreths introduced the use of the motion picture camera as a medium for observa-tion (micro-moobserva-tion analysis). In this way, a film

may be observed frame-by-frame for detailed interpretation; this has the added advantage that where gangs or teams of workers are involved, simultaneous observation is possible to enable analysis of coordination.

Since most construction work consists of longer cycle tasks of either semi-repetitive or non-repe-titive nature, the cost of movie film may become excessive. To solve this, intermittent exposure of the film (memo-motion analysis or time-lapse photography) at the rate of 50 or 60 exposures or sometimes fewer per minute permits considerable economy with satisfactory results. It is fairly obvi-ous to most observers that, for the most part, less detail is justified or desirable in analysing con-struction work than would usually be true under factory conditions. In specific instances, however, a minute and specific inquiry may be demanded, particularly where either the work is highly repe-titive (e.g., bricklaying) or a designated problem occurs.

Flow Process Analysis. ln addition to the deter-mination of the body movements of workers at their individual places of work, any thorough examination should incorporate an analysis of the flow of materials to the men at their work stations, or alternatively the flow of men moving between successive work stations. This type of study is known as "flow process analysis".

If such an analysis is directed toward the flow of materials, the activity or condition of the material involved can be described under one of five headings:

i. Operation: where the material is transformed or otherwise subject to change in form, appear-ance or nature.

ii. Transportation: involves the movement of the material.

iii. Delay (or temporary storage): includes the condition where the material is not subject to any operation, nor under controlled storage, but merely awaiting action.

iv. Storage (or permanent storage): exists where the material is subject to inventory control and, normally, some form of security.

v. Inspection: involves visual and/or other means of checking. Where the flow is that of workers moving about in the performance of their jobs other, but analogous, terms and descriptions are substituted. The procedure of the analyst con-sists of recording the flow on a specially-designed form incorporating symbols for use in later inter-pretation. Necessary details in the form of distances involved, rough tirnes (for delays and

storages), number and weight of units, and other commentary are also includedl.

The flow process chart often is supplemented by a "flow diagram" which is simply a layout sketch of the site with the lines of flow suPer-imposed thereon. By the combined use of flow process charts, with their related data, and the flow diagrams, the skilled analyst can pick out flaws in the layout and planning of the job loca-tion. He can determine inferior routes being utilized, sources of congestion and delay, and redundant inventory of materials.

WORK MEASUREMENT

The mere determination and classification of body movements. or of the flow of materials and people about the work place, is usually insufficient in ascertaining all the necessary information of concern in work study. Over and above this basic analysis is the need for objective measurement of the length of time required to perform the work as detailed. This measurement (of the time which should be taken to complete a unit of work) then becomes a "standard" which can be used in planning the work, analysing alternative methods, scheduling production, provision of a basis of incentive payment of wages, and in cost analysis and control. Work measurement originally was introduced by F. G. Taylor in the Bethlehem Steel Company over seventy years ago and has since been widely adopted. Although the earlier abuses of work measurement have subjected this procedure to substantial controversy, resulting in limited acceptance of many of its uses and advan-tages, it still serves an important and worthwhile function. The evolution and refinement of tech-niques has caused work measurement to become more flexible and hence more easily applied to various conditions of work.

Time Study. The original form of measurement, and still the most frequently used, is stop-watch time study. The procedure consists of having an observer record continuously the times taken to perform each of the elements included in the job. One observer can normally watch only one worker at a time, as the procedure also includes notation of the times and an evaluation of the effort rating. The job or task is usually observed through several cycles over an extended period of time in order to ensure that a representative set of time values are obtained.

Upon completion of the study the time values

lFor detailed information about any of the work study techniques, including the use of forms, equipment, etc., the reader is referred to any of the several textbooks on Motion and Time Study. See also: H. B. Maynard, Ed., Industrial Engineering Handbook, (New York; Mc-Graw-Hill, 1956).

6

for each element of the job are adjusted (levelled) according to the estimate of "effort" exerted by the operator during the period of observation. Where the work was performed at a relatively fast pace, the allowed "normal" time will equal the observed time increased proportionately by the effort rating. If the observed pace was relatively slow, the opposite levelling factor would be applied. The element times are then averaged, following which the total of the combined element times is obtained. This "total normal time" is modffied by appropriate allowances for rest, personal needs' and process factors to provide a final "total stand-ard time" for the job. This standstand-ard time is used as the basis for all estimating and costing purposes with respect to the labour factor of the job.

Stop-watch time study, when carried out by competently-trained personnel, will provide accu-rate data (to a tolerance of 1/100 of a minute if desired) over a broad range of typical work situ-ations. It is a moderately expensive technique inasmuch as trained observers are essential and one observer can only study one job at a time. It is the most satisfactory procedure' however, where detailed information of a job is requested (e.g., in trouble-shooting), where only a few oper-, ators are involved in the work being studied, or where the work is largely of a non-repetitive nature. Stop-watch time study is the foundation of all work measurement.

Predetermined Times and Derived Systems. Two separate approaches have been made to economize on work measurement in those in-stances where the work contained in several jobs is repetitive with small variations, or otherwise similar. The first approach has been to collect the basic elemental information obtained through stop-watch observations and compile it in a man-ner to facilitate the synthesis of standards for new jobs, without having to repeat the actual time study procedure. The times are usually plotted on charts and graphs, or condensed into formulae' and are known as standard data. Once obtained' standard data can be manipulated by lowerskilled -often clerical - labour in the creation of new time standards.

The second approach is to establish time values, under laboratory or actual conditions (or both), for basic motions such as the therbligs discussed earlier. If consistent times can be obtained for these minute motions, it is reasoned that work measurement should merely consist of identifying each of the basic motions of a job, extending each by the appropriate time value, and totalling the time values to obtain a standard time. Several such predetermined time (PDT) systems are in

use. By the expedient combination of commonly-grouped basic motions, PDT systems can be made particularly appropriate for special purposes such as office work, maintenance, and construction. These derived systems provide time values which are equivalent to those obtained by standard data. Such work measurement procedures, where appropriate, have two advantages over stop-watch time study in addition to their cost saving features. They do not require continuous direct observation of the worker on the job (a consideration which is generally over-emphasized but which can be of significance on occasion). Further, they do not require individual estimates of the efiort rating (for levelling purposes), a procedure which comes under considerable questioning where stop-watch time study is used. Against these advantages, PDT requires greater skills on the part of observers and therefore can only be deemed to be econom-ical under specified conditions.

llork Sampling. Work sampling, or t}te ratio-delay study, is a random sampling method of obtaining facts about machines and/or human activities. The theory of work sampling is

. . . that the number of times a man or machine is observed idle, working, or in any other condition, tends to equal the percentage of time in that state. Over a sufficiently long study, this holds true whether the occurrences are very short or extremely long, regular or irregular, many or few. It should be pointed out that the study can be as detailed as you care to make it; but the more detailed it is, the more are the observations necessary to get the degree of accuracy that might be desired for all the elements2.

Work sampling is based on the law of probability:

A sample taken at random from a large group tends to have the same pattern of dis-tribution as the large group or universe. If the sample is large enough the characteristics of the sample will differ but little from the characteristics of the group.s

Unlike previously-described techniques, in work sampling several operators (up to thirty or more) may be observed on a partial or sampling basis. These workers may perform varied tasks and be located over scattered areas, conditions which are typical of construction site operations, for exam-ple. The observations are carried out according 2L. H. C. Tippett, The Journal ol the Textile Institute

Transactions, February 1935, p. 53.

3!4ph tnl. Barnes, Motion and Time Srzdy, (New York; Wiley, 1958), p. 498.

to a carefully devised and preconceived plan based upon sound statistical precepts.

Work sampling is a measurement tech-nique for the quantitative analysis, in terms of time, of the activity of men, machines, or any observable state or condition of operation. Work sampling is particularly useful in the analysis of non-repetitive or irregularly oc-curring activity, where no complete methods and frequency distribution is availablea. The exact degree of accuracy of a work sam-pling study can be regulated very simply by varying the number of observations made. Fun-damentally, the accuracy required of any study is dependent upon the end use to which the study will be put.

By its nature, work sampling does not lend itself to the same preciseness or detail as the other methods of work measurement. The elements chosen will probably be more general and the possibilities for close analysis will be correspond-ingly decreased. Work sampling however does afford the advantages of wider coverage and more rapid determination of the essentials of work content and character than do the other methods. The costs of this method are also very much less, partly due to the broader coverage possible, but also due in part to the fact that the observers do not require a high degree of skill in order to do a satisfactory study.

Work sampling is basically a procedure of work analysis; it can be likened, in a sense, to memo-motion analysis without the use of a camera. Carried one step further (viz., by the relating of production data to the observed results) it be-comes a procedure for work measurement. The question arises as to whether the effort ratings of observed workers should be included as modifiers of the final results. Depending upon the purpose of the study a levelling procedure may or may not be necessary.

II. ANALYSIS OF CONSTRUCTION

\U7ORK

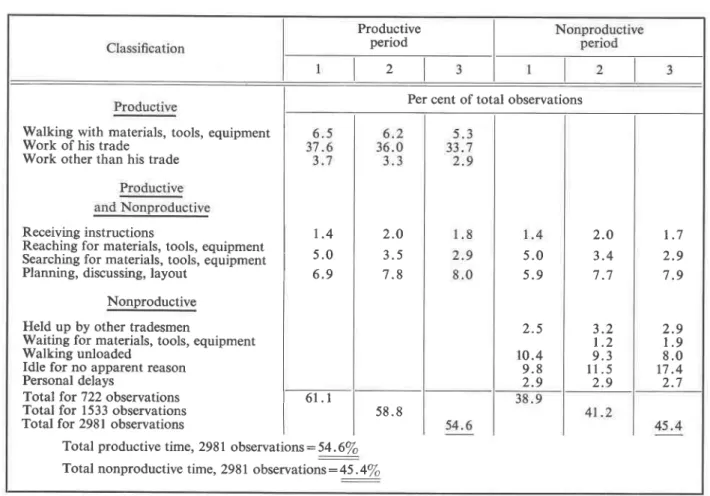

The preceding section outlines briefly a few of the procedures of work study most likely to be considered in any detailed analysis of construction work. In the study undertaken, work sampling was used in order to obtain basic information as to the content of typical jobs representative of construction work, with particular emphasis on determining the extent of productive and non-productive time spent on the job.

aRobert E. Heiland and Wallace J. Richardson. Work Sampling (New York; McGraw-Hill, 1957), p. l.

CHOICE OF A TECHNIQUE

Objective. In discussions with those expert in construction, it was continually emphasized that the keys to success in the industry were labour, and the ability to "control" one's labour force. Materials and subcontract prices are very largely fixed and non-controllable items generally with equal effect on all contractors. On the other hand, a company's methods of operations and its

utili-zation of labour are the controlling factors directly influencing a firm's ability to bid successfully con-sistently against competitors' tenderss.

The purpose of this study was not to investigate bidding procedures and estimating methods. It is clear that these matters, in themselves, may well afiect success in competitive bidding but such considerations are outside the immediate scope of this investigation. In the final analysis, estimates and bids depend upon accurate costing informa-tion. Cost estimates can only be effective under conditions where exact labour requirements are known, the labour is effectively utilized, and a continual check is made to assure control of labour. These basic requirements demand more detailed and specific knowledge of labour and productivity than is generally available to most construction firms at the present time.

One purpose of the study at hand, therefore, was to ascertain the nature of construction work. This involved a determination of the elements of work which comprise the common tasks and jobs in construction, how these elements are performed, which of the elements are of a purposeful or useful character, which elements are nonproductive, how much of the latter is idle time, and how the ele-ments are inter-related and coordinated.

In addition to the foregoing fact-determination, the study should provide analysis of factors affect-ing the work elements. Hence there is need to observe and record all related environmental factors such as supervision, materials, tools and equipment, facilities, and working conditions.

The final results of the study should indicate clearly the pattern of construction work as ob-served on the site, along with suitable explanations of reasons for the pattern.

Limitqtions. The intermittent nature of construc-tion operaconstruc-tions and the lack of informaconstruc-tion present methodological difficulties in a study such as this. Further difficulties arise from the fact that per-sonnel in the industry tend to avoid direct meas-urement of the work of labour, particularly when carried out by strangers. It was thus essential that a method of determining labour utilization be

chosen which would minimize animosity of the workers toward the observers and yet, at the same time, permit accuracy of observation and meas-urement.

Another part of the problem was to select a measurement technique which would give the broadest possible coverage in a limited period of time. The coverage was essential in that this study was of a type not previously employed in the industry in Canada so that validation of results implicitly demanded the observation of as large a group of workers as possible. The time limitations resulted from practical problems of the observers' curtailed schedules, and the progression of work on the job sites themselves.

The choice of a method of measurement, there-fore, was restricted to one which was neither too time-consuming nor too detailed at the outset. The problem had to be approached in a total perspec-tive rather than a narrow one of specific tasks or operations; the narrowest conlines for observation would seemingly include a trade.

The work measurement procedure chosen had further to open up areas to which additional study could be directed. This is an added reason why a narrow study of a specialized operation or task would be unsuitable. Neither would it have per-mitted any reasonable assessment of management techniques or characteristics as these bear on the work performed.

With all the considerations discussed above given their due weight, work sampling appeared clearly to be the most appropriate work study procedure.

Advantages ol Work Sampling. The reasons for the selection of work sampling as the preferred technique in this study have been already indicated. At this point a summary of advantages and uses of this work study procedure is provided to indi-cate its merits and the range of potential uses to which it may be put:

(1) Work sampling is the practical compro-mise between the extremes of purely subjective opinion and the "certainty" of continuous observation and detailed study6. (2) A few random observations giving the

desired degree of accuracy can be done economically, usually as a collateral duty of supervision, while other detailed meth= ods of appraisal are more expensive and may require the full-time services of a group of specialists?.

(3) The exact degree of accuracy of a work

6Heiland and Richardson, op. cit., p. 6. 7 Ibid.

sampling study can be regulated very simply by varying the number of obser-vations made.

(4) Work sampling may be used to measure activities and delays.

(5) Work sampling, under certain circum-stances, may be used to measure manual tasks; that is, to establish a true standard for an operation.

(6) The results of the study serve to direct attention on areas where other work simplification or motion study techniques can be applied. Those activities involving the most time can be analyzed for sim-plification.

(7) Work sampling serves as a quick method of evaluating established standards. (8) Work sampling gives management reliable

information, by giving it the tools for finding out what is done by operatives performing non-repetitive work.

(9) It serves to point out areas in which train-ing might be necessary, both with respect to operators and supervisors.

(10) It helps to determine "skill utilization" for groups of workers, or for individuals hired because of their acquired possession of specified skills. With this information re-garding proportionate amounts of time for various activities it is possible to reor-garize duties, responsibilities, and activities to utilize more efficiently the skills of those able to undertake given classes of work.

SELECTION OF A REPRESENTATIVE STUDY

For the purposes of this report it is necessary to present, in detail, only one of the four work sampling studies which were carried out. The procedures used throughout were carefully check-ed (particularly in the first study) for their accu-racy and reliability, and led to a decision to continue their use throughout the series8. Since the first study to be carried out contained much of a theoretical nature, outside the range of this report, its inclusion was not considered desirable. Study number two covered house-building and number four concerned road-building; they were passed over in favour of study number three which took place on an institutional project similar to the bulk of commercial/industrial type construc-tion projects.

A detailed account of this third of the four work sampling studies is presented in order to depict and illustrate the thoroughness and objec-tivity of work sampling procedures. This detailed account will serve also to describe the specific work elements which comprise construction jobs. Explanations will be given as to why these par-ticular elements of construction tasks were selected. The account will also convey to the reader a picture of the entire methodology, pur-poses, and limitations of work sampling as it was carried out in this instance.

It should be borne in mind that much of the procedure and precepts incorporated into this one study (for example, definitions of work elements) is the result of extensive evaluation carried on over the project as a whole. All four studies used common procedures, terminology, and conceptual frameworks. Thus the study which is described in detail is but one of four segments of the total research effort supporting this report and its conclusions.

III. THE TRIAL STUDY

Before beginning a full-scale work sampling, a trial study was deemed useful because it would give an opportunity to determine how the final study should be approached and which elements should be studied to reveal and illustrate in the best way the efficiency with which labour re-sources were being utilized. The method of under-taking the study, its uses, and application were first explained to the project manager. An analysis of the work force was made to determine which trades would best throw some light upon the management techniques being used. Then the trial study was undertaken.

In a study of this nature, one is dealing with the human element. Thus it is important to determine the probable reaction of the men and to decide what adjustment should be made in order to obtain a true picture of activities, methods, and pace. A trial study also enables the observer to familiarize himself with the work situation.

In selecting the elements into which the work is grouped, one must bear in mind that after a fine breakdown study has been completed, it is possible to combine many of the observations but it will not be possible to subdivide a gross break-down after observations have once been obtained. The trial study must also include a study of the site layout considering locations of the struc-ture, materials storage, and tool storage facilities. This is illustrated in Figure 1. When this study was undertaken the structure was not at the stage illustrated in the diagram. (Reference may be

8Alexander James Curror, "A Work Sampling Study of Building ConsJruction Labourers and Carpeiters" (un-pupliqhe_d _undergraduate's thesis, The University' of British Columbia, 1959).

SITE LAYOUT MATERIAL STORAGE / \

/

l'"1\

\ | t l \ A S S E M B L Y / fl-,0* LI I A I E R I A L STORAGE AREA I - ) = ,orrflir rro, EASEilENT UNOER THIS S E C T I O Nmade to Appendix I for a description of opera-tions during the period under study.)

O F F I C E W I N G ( U N O E R C O N S l R U C T I O N )

FIGURE I

SKETCH DIAGRAM OF BUILDING SITE ILLUSTRATING: STRUCTURE, FACILITIES AND

MATERIAL STORAGE AREAS UNDER STUDY Site Management. A study of organization must be undertaken as part of the trial study. Only by knowing the makeup of management on the site, within the firm itself, and the authority and responsibility of each, is one able to evaluate the results of the study in relation to management and their techniques.

Figure 2 illustrates the organizational structure, and the lines of authority of this particular management group. The project manager on the

FIGURE 2

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

Illustrated is the formal line of relationship on the site. It was noted that even with the existence of this formal organization structure informality was more typically practiced.

job was responsible to the head office in

Van-couver. The main office tenders a iob based on 1 0

its estimate and if the tender is accepted, the firm will normally receive the job. A project manager is then appointed, and the office will provide him with the detailed estimate, stating allowable sums for each segment of the operation. The estimate, plans, and specifications serve as the basis for planning the work.

The project manager will plan his own job, and schedule the time based on how he thinks it is best to do each section of the work. At all times he keeps in mind the cost estimate. A master schedule is charted for each major section of the work. This is based primari$ on the start and completion dates of specific operations such as excavation work, formwork, etc.; each is shown as a separate item on the schedule of operations. This schedule is based mainly on the project manager's experience of how long each section of work should take.

The manager is entirely responsible for his job and would make purchases for the job; head office would only purchase when there is an op-portunity of receiving quantity discounts. It is the responsibility of the manager to plan the work, and maintain costs within the estimate'

The manager has no written plan of work other than the schedule. The details are "in his head". He is usually one month ahead of actual opera-tions in his planning. The general foreman is one week ahead, and each foreman is one day ahead of operations. This means that in their own minds these men have planned out what is necessary to fit within the scheduled time allotted by the project manager for each section of the work'

Head office serves as the estimating and paying source. It estimates jobs and pays all bills. This office keeps track of each job by the use of a general superintendent who travels to each job, and checks on the progress of the job and methods of operation. At stated intervals the actual costs are compared with the estimated costs. By this method the office is able to record progress on a cost basis.

The project manager on the job under study has three men directly under him. The general foreman issues orders to the two carpenter foremen, and very often it was noted that he issued orders to the labour foreman. Each car-penter foreman in turn issued orders to the men under him.

The structure being constructed was built in two sections: the office wing and the classroom wing (Figure 1). One carpenter foreman was in charge of each section. Each carpenter foreman had between ten and fifteen men working under

H E A D O F F I C E P R O J E C T M A N A G E R O F E A C H J O B C H I E F L A B O U R F O R E M A N O F F I C E C L E R K C A R P E N T E R F O R E M A N LA BOUR FOREMAN C O N C R E T E CARP ENTER F O R E M A N

him, though this number varied considerably because of weather conditions and the rate of progress of each section. Each carpenter foreman was responsible for his particular section of work. The office clerk (who also served in the capacity of first aid man) recorded labour times and ordered materials as required. Any of the three foremen could write out a requisition for materials, and order these through the office clerk. The project manager would frequently check pur-chases, at all times considering actual costs in relation to estimated costs.

The chief labour foreman was responsible for the activities of the labourers over the complete job site. Included were: labourers, carpenters' helpers, and the concrete crew. It was noted that an interchange of activities between labourers existed. This enabled the firm to shift the men from one job to another, as the work presented itself.

The labour foreman for concrete was respon-sible for the concrete-placing crew but much informality existed, as was noted throughout the organizational setup. The relationships were not fixed. There was a great deal of interchange of ac-tivity between the foreman and the superintendent. The organization structure was not rigidly adhered to. It served as a guide which proved to be very flexible; the interchange of ideas and orders would often go across the chart rather

than up and down. The crew fluctuated in size during the study, ranging from approximately twenty men to fifty men. The average number was approximately eighteen to twenty labourers, which includes labourers per se, carpenters'helpers, and the concrete placing crew. The carpenter crew averaged from twenty to twenty-five men.

Within each crew of workers "lead hands" were appointed. The project manager stated that generally there was one lead hand for about each five workers. The foreman would transmit orders to the lead hand, who in turn issued orders to the men under him. This system served to reduce the span of control for each foreman.

Importance ol the Trial Study. The trial study in-dicated that a detailed study of labourers and carpenters would provide a reasonably clear picture of efficiency in this firm. The company stated that it was representative of at least twenty-five per cent of the contractors in Canada, and therefore management practices observed in this firm would probably be representative of at least twenty-five per cent of the construction firms.

A trial study should provide a knowledge of the operations, site layout, and company organiza-tion. It should then be possible to state and define the classifications to be examined within the main study, and the method of setting up the study.

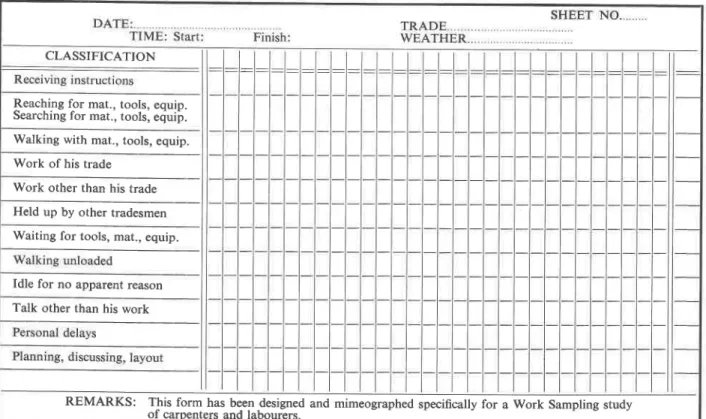

FIGURE 3. WORK SAMPLINC ANALYSIS FORM

REMARKS: This form has beendesigned and mimeographed specifically for a Work Sampling study of carpenters and labourers.

CLASSIFICATION

Reaching f-or mat., tools, equip. Searching for mat., tools, eq'uiir. Walking with mat., tools, equip. Work of his trade

Work other than his trade Held up by other tradesmen Waiting for tools, mat., equip.

Idle for no apparent reason Talk other than his work

DESIGN OF THE ANALYSIS FORM

Element Classification Work sampling is a study of the relationship of productive to nonproductive work. Bearing this in mind one should define the classifications so that they may be considered as either productive or nonproductive. Certain items are most difficult to classify as either, and because of this are classed as a combination of productive and nonproductive activities.

In designing the work sampling analysis form (Figure 3), one must bear in mind the objective of the study: in this case it was an attempt to determine the utilization of the labour force. To do this adequately notation must be made of unusual conditions, such as the weather, the time of observation, and the trade being observed. These points must be considered when designing the form. If conclusions are to be drawn and reasons for the conclusions established, it must be possible to relate the final results to the con-ditions affecting these results.

Selection ol the Elements under Study. Gilbreth has defined the variables of the worker and the variables of the surroundings, equipment, and toolso. Continuation of his study and examination of techniques used by bricklayers enabled him to define the variables of motion. There were certain subdivisions or events which he thought common to all kinds of manual work. He coined the word "therblig" (as explained earlier) as a term of reference for the seventeen elementary subdivisions of a cycle of motions. Observing the therbligs closely, it will be seen that they correspond to the motions listed and studied on the work sampling analysis form.

The therbligs named by Gilbreth are: search, select, grasp, transport empty, transport loaded, hold, release load, position, preposition, inspect, assemble, disassemble, use, unavoidable delay, avoidable delay, plan, and rest for overcoming fatigue. These motions were originally applied-'to a study of hand movements but it became evident during the trial study that the items to be studied would be a ramification of Gilbreth's seventeen basic motions.

Gilbreth discussed variables of the worker, these being: anatomy; brawn, contentment, creed, earn-ing power, experience, fatigue, habits, health, mode of living, nutrition, size of the man, skill, temperament, and training. He also considered the variables of the workers' surroundings, equip-ment. and tools. The variables considered were:

oFrank G. Gilbreth, Motion Srzdy (New York. D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1911).

appliances, clothes, colours, entertainment, venti-lation, lighting, quality of material, reward and punishment, size of unit moved, special fatigue-eliminating devices, surroundings, tools, union rules, and weight of unit moved.

These variables became evident as the trial study was undertaken. The variables considered by Gilbreth are present in construction and provi-sion must be made on a work sampling analysis form to record these variables if they unduly affect the worklo. The trial study enables one to envision the factors which are constant' and these are considered when the analysis items are defined and listed.

IV. CONDUCTING THE STUDY

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF "RANDOMNESS''"Randomness" is an important facet of work sampling and must be carefully considered. The study undertaken presented peculiar problems of obtaining an unbiased sample leading to presenta-tion of truly accurate results.

Assurance of randomness and a minimum of bias are necessary, and the sampling procedure was designed bearing these points in mind. The method chosen to assure randomness and mini-mize bias, or to eliminate the bias in the sampling process, will be detailed below. Each part com-prising the total must have as much chance as any other of being drawn11. The method chosen is similar to that defined in the Work Sampling text by Heiland and Richardson'

Sometimes the assignment of observation times is expedient, especially when dealing with operations such as widely scattered maintenance or construction work, . . . when the foreman is the observer. In these cases a method should be provided for the observer to record the times when observations were made, by intervals used as the periods within which randomness is desiredl2.

Selection ol Observation Time. A form shown as Figure 4 was designed. The day was divided into eight one-hour periods, and in turn these were divided into four fifteen-minute periods. A total of thirty-two fifteen-minute periods were listed on the left-hand side of the chart. lt was estimated from the trial study that fifteen minutes would be the required time to mn a samplel3. The degree

loFrank G. Gilbreth, op. cit., p. 6'7 '

llHeiland and Richardson, op. cit., p. 114-115. tzlbid., p. 14.

rsDurins the course of the study there were samples which-took more than fifteen minutes. In these cases thJ fifteen-minute interval during which the sample was first undertaken was recorded as the sample time.

FIGURE 4

RECORD CHART FOR RECORDING TIME INTERVALS DURING WHICH SAMPLES OF CARPENTERS AND LABOURERS WERE UNDERTAKEN

8 l e l t o l r r l t z l r r l r u l r s x x x x x x x x 1 3

of accuracy expected was stated, and the number of observations and samples required was indicated on the chart by a heavy line.

The degree of accuracy required was stated as plus or minus 5 per cent. It was assumed that the nonproductive factor would be approximately 40 per cent. This figure was chosen because of the results obtained by a previous study of a similar naturela. The number of observations for labour-ers and carpentlabour-ers required to give the degree of accuracy based on the approximation of 40 per cent nonproductive time, was taken from a chart in a work sampling text15. It is possible to cal-culate the required number of observations by formula, but the chart is as reliable, and much the more simple of the two methods.

The required number of observations to give the desired degree of accuracy determines the number of samples required. Assuming average employment of 20 carpenters and 20 labourers, the required number of samples was determined to be at least 120.

The approximate length of time lapse between the beginning and termination of the study had to be selected. The observer was then able to deter-mine the approximate number of samples to be taken each day. "The objective is to have each day of the study as representative as possible for all other days. As the observer proceeds during the study period he is able to 'keep score' himself, and thus be sure that each fifteen-minute time interval is adequately covered"16.

During the evening preceding each day's study, the observer selected, at random, time intervals during which the observations would be taken. The selection of time intervals was governed by hours available to the observer, and those inter-vals which had already been studied. It was the responsibility of the observer to prevent a pattern of observations which would introduce bias.

After an observation trip, an X was placed in the time period row corresponding to the time the trip was taken, beginning at the left-hand side of the chart. When a time period had already been used (marked with an X) and was to be used again, an X was marked next to the previous X. Thus the chart was built from left to right, as the study progressed. As the study progressed the observer had a visual record of progress, and at any time attention could be directed toward those time periods that had the least number of X's. r4Curror, op. cit.

lbRalph M. Barnes, Work Sampling (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.. 1957), p. 30-3 l.

r6Heiland and Richardson, op. cit., p. 114-115.

Bias may be minimized by randomly selecting the intervals within the available time, but still maintaining an even distribution of observations or samples within the available time intervals-Under this method the use of random numbers has been eliminated. By selecting the time periods carefully, however, one is able to prevent a regular pattern of observations, and should be able to assure adequate representation of each time interval over the duration of the study. If each time interval progresses evenly in relation to the others, and a pattern of preselection of times does not form, the possibility of bias is minimized. Randomness Assured by Activities ol the Worker. Randomness and the elimination of bias are further guaranteed by the nature of the study undertaken. The job under study was extensive in size and area, and the men were scattered over the complete area of the site. During the study it was found that carpenters, and most particulaily labourers. were seldom at the same work station for a long period of time. During an 8-hour day one to eight samples of labourers and carpenters were usually taken. These samples were scattered over the day with never more than two in any one hour.

Randomness was found to exist within the men themselves, by the very nature of their tasks. The man generally goes to the material, and thus is seldom at exactly the same work station during any two samples. In many cases the men may, in the course of a day, find themselves scattered over many areas of the site, further assuring randomness within the sample.

During the course of study the activities of two men, a labourer and a carpenter, were noted in detail to determine whether randomness did exist within the men and their activities. The five sam-ples of that day were noted, and the particular positions of these two men recorded. It was found that neither the labourer nor the carpenter were to be found in the same spot for any two of the observations during the course of that day. Throughout the study the fact that the men were seldom in the same spot, and often hundreds of feet from their position at the time of the previous sample, verified the fact that randomness existed within the actions of the men themselves.

Further assurance of randomness was obtained by the manner of recording observations. The observer attempted to start each sample at a spot different from that for the preceding sample. In this manner no fixed pattern of route was established.