CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

AND ITS ROLE IN LEBANESE ECONOMY

by

Nicolas Elie Chammas

B.E., American University of Beirut June 1985

SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE

DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY December 1986

O

Nicolas E. Chammas 1986The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author:

-Department of Civil Engineering December 10, 1986

Certified by:

F*kd Moavenzadeh Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by:

Ole Madsen, Chairman Civil Engineering Departmental Committee

ARCHIVES

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

_ _

"More than ever before, Lebanon stands ready to face all challenges."

President Amin Gemayel Baabda Palace

CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

AND ITS ROLE IN LEBANESE ECONOMY by

NICOLAS ELIE CHAMMAS

Submitted to the Department of Civil Engineering

on December 10, 1986 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in

Civil Engineering

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of the

construction sector and its main participants in the Lebanese economy. It comes at a time when the country as a whole is torn into bits and pieces and when, following eleven years of war, the economy is in shambles: the industrial sector is virtually crippled, the wheels of commerce are slowly grinding to a halt, and the national currency is fast becoming worthless.

In this tormented context, the construction sector, as will become apparent in the following pages, has incredibly maintained its

resilience.

Thesis Supervisor: Fred Moavenzadeh

Title: Professor of Civil Engineering Director, Center for Construction

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I offer my sincere thanks to His Excellence Cheikh Amin Gemayel, President of the Republic of Lebanon, for his moral support and warm encouragements.

I extend my gratitude to:

His Excellence Mr. Victor Cassir, Minister of Economy and Commerce, Industry and Petroleum

His Excellence Mr. Khatchig Babikian, Former Minister and President

of the Parliament's Commission for the Reconstruction Mr. Mitri Nammar, Administrator of the City of Beirut

Dr. Fouad Abi Saleh, President of the Association of the Lebanese Industrialists

Mr. Bahaeddine Bsat, Former Minister and President of the Syndicate of Engineers

Cheikh Fouad El-Khazen, President of the Association of the Lebanese Contractors

Dr. George Frayha, Director of the American University of Beirut Off-Campus Program.

I wish especially to thank Professor Fred Moavenzadeh for his guidance and invaluable advice.

I also appreciate and acknowledge the participation and information provided by several individuals and organizations, which made this work possible.

I am endebted to my sister Tina for her patient typing. My deepest thanks go to my family. Their love and support contributed greatly in the achievement of my academic endeavours.

35 O3 36I ,Halbs Al Min -. GTripoli _N~h' Si -.

~

ASH SHAMA .*Amyun Ouma e * "-I~~

NY -3400'--Mec Ad Dlmui dd Din~j'

*Bar]a AL I BIOA 8aabk '-I lb*-* Al Oullylsh,2

K

'-' 'Jubb Jannin i·/,~ ·f-~51 'fr i r -3030'--Aci an /-~i.

·

UNDOf / , Zone .Baniyias GOLAN HEIGHTS (Israeli occupied) Al Ounaviirah" An Nbqurah' /" sRAEL35'35030' jliZ 36'000 As $Snamayn, A; S r$ h a; SughP1not nocssua.fjy bolfo'tofl.' 36030'

I I Al Oubayvil Al Hirmal .

/

Al[O-I

/ -5, , NahArlyyA 33"00oI

;harri,/i/i.

'2-35030'

I--

Al U.--h 36"3C z. 1, .,BIBs-110- 1

! / / 4 "a

uslool

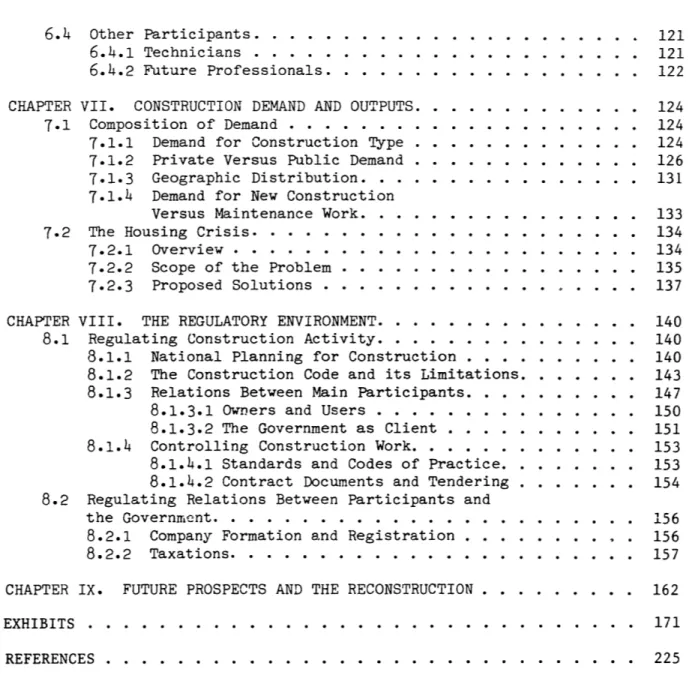

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PAGE .*... ... 1 ABSTRACT ... ... ... ... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... .. 4 MAP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... ... . 6 LIST OF EXHIBITS ... .. 9 INTRODUCTION ... .... 12 CHAPTER I. GEOGPAPHY ... 14

CHAPTER II. PEOPLE ... 17

2.1 Ethnic and Linguistic Groups ... 17

2.2 Religious Groups ... 18

2.3 Demography ... 19

CHAPTER III. ECONOMY ... ... ... .. 22

3.1 General ... .. 22

3.2 Impact of the War on the Lebanese Economy .... 27

3.3 Industry . . . . . . . . . . . ... 31

3.4 Commerce and Services ... . 36

3.5 Banking ... .. 39

3.6 Agriculture ... 41

3.7 Transportation ... 44

3.8 Work Force ... ... .. 45

3.9 Foreign Firms in Lebanon ... 47

CHAPTER IV. THE ROLE OF CONSTRUCTION IN ECONOMIC. DEVELOPMENT. .. ... 51

4.1 The Construction Industry in the Middle-East . . 51

4.2 Construction's Role in the Economy ... 53

4.3 Construction's Contribution to Employment . . . . 55

4.4 Other Contributions ... 56

4.5

The Nature of Construction ... 564.6 The Structure of the Construction Sector .... 58

CHAPTER V. CONSTRUCTION INPUTS ... ... .. 60

5.1 Demand for Resources ... 61

5.2 Building Materials ... 63

5.2.1 Contribution of Building Materials to Economic Growth. .. ... 63

5.2.2 Success Criteria for the Production of Building Materials ... 64

5.2.3 'lypes of Material Inputs. .. ... . 65

5.2-3.1 Cement. .. ... 66

Table of Contents (continued)

5.2.3.3 Iron, Steel and Aluminium. 5,2.3.4 Wood . . . . . . . . . . .

5.2.3.5 Water...

5.2.4 Construction Materials Prices.

5.3 Labor 5.3.1 Labor Supply . . . . . . . . . . . 5.3.2 Labor Demand... 5.3.3 Labor Wages ... 5.3.4 Labor Training ... 5.4 Equipment ... 5.5 Finance ... 5.5.1 Owner's Perspective . . . . . . . . 5.5.2 Constructor's Financing. . . . . .

5-5.3 Commercial Banks Financing .

5.5.4 Public Financing . . . . . . . . . 5.6 Land ...

VI. CONSTRUCTION PARTICIPANTS ...

Overview

The Professional Sector . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Consulting and Contracting Firms . . . . . . . .

6.3.1 Consulting Firms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.3.1.1 Dar Al-Handasah Shair and Partners 6.3.1.2 Dar Al-Handasah Nazih Taleb ... 6.3.1.3 Associated Consulting Engineers.

6.3.1.4 Rafik El-Khoury and Partners . . . . 6.3.1.5 Typical Roles and Fees

of a Lebanese CEDO. *... 6.3.1.5.1 Roles... 6.3.1.5.2 Remuneration . . . . . . . 6.3.2 Contracting ... 6.3.2.1 Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.3.2.2 Tendering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.3.2.2.1 Tendering Methods . . . . . 6.3.2.2.2 Bonds... 6.3.2.2.3 Tender Documents . . . . . 6.3.2.2.4 Subcontracting . . . . . .

6.3.2.3 Major Contracting Firms . . . . . . .

6.3.2.3.1 Contracting and Trading

Co. (CAT) . . . ...

6.3.2.3.2 Consolidated Contractors

Co. (CCC). ...

6.3.2.3-3 Kettaneh Freres . . . . . .

6.3.2.3.4 Fares-Minefa, Hariri-Oger,

Mokbel-Wayss and Freitag.

6.3.2.3.5 Zakhem International S.A.

6.3.2.3.6 Almabani ... 6.3.2.3.7 Societe Nationale d'Entreprise (SNE) ... 6.3.2.3.8 Alfred Matta-Enterprise. .. . . 84 .. . . 84 . . . . . 85 . . . . . 88 . . . . . 89 . . . 90 . . . . 92 . . . 93 ... . 93 .... *. 94 . . . 94 . . . 96 . . . 97 . . . 97 ... .. 100 .. . . .100 .. . . .102 ... .. 103 ... .. 105 ... .. 106 ... .. 106 . . . 110 . . . 112 . . . . 113 .... . 115 . . . 118 . . . . 120 .. . .. 120 -7-CHAPTER 6.1 6.2

6.3

PageTable of Contents (continued)

6.4 Other Participants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

. 6.4.1 Technicians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

6.4.2 Future Professionals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

. CHAPTER VII. CONSTRUCTION DEMAND AND OUTPUTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.1 Composition of Demand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

7.1.1 Demand for Construction Type . . . . . . . . . . . ..

7.1.2 Private Versus Public Demand . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

7.1.3 Geographic Distribution . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

. 7.1.4 Demand for New ConstructionVersus Maintenance Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.2 The Housing Crisis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.2.1 Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.2.2 Scope of the Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.2.3 Proposed Solutions .... . . . . . . . . . . . . . CHAPTER VIII. THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.1 Regulating Construction Activity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.1.1 National Planning for Construction . . . . . . . . . . 8.1.2 The Construction Code and its Limitations. ... 8.1.3 Relations Between Main Participants . . . . . . . . . .

8.1.3.1 Owners and Users . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.1.3.2 The Government as Client . . . . . . . . . . . 8.1.4 Controlling Construction Work . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.1.4.1 Standards and Codes of Practice . . . . . . . . 8.1.4.2 Contract Documents and Tendering ... 8.2 Regulating Relations Between Participants and

the Government . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.2.1 Company Formation and Registration . . . . . . . . . . 8.2.2 Taxations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . CHAPTER IX. FUTURE PROSPECTS AND THE RECONSTRUCTION . . . . . . . . . EXHIBITS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Page 121 121 122 124 124 124 126 131 133 134 134 135 137 140 140 140 143 147 150 151 153 153 154 156 156 157 162 171 225

Exhibit Number 1.1 2.1 2.2 2.3 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 4.1 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5-7

5.8

5.9 LIST OF EXHIBITS CaptionLebanon's Principal Ethnic Groups . . . . . Religious Composition of Lebanon . . . . . Projections of the Religious Composition

of Lebanon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Evolution of the Lebanese Population . . . Deficit of the Ministry of Oil . . . . . . Oil Production and Consumption . . . . . . Geographical Distribution of

Industrial Concerns . . . . . . . . . . . Industrial Production and Export ... Transfers of Lebanese Working Abroad . . . Repartition of the Country's GDP ... Evolution of the US Dollar, 1975-84 . . .

Evolution of the US Dollar, 1985 ... The Construction Sector: Interrelated

Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Input Factors for Typical Construction

Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Typical Consumption Coefficients . . . . . Criteria for Building Materials Production Cement Production and Consumption . .... Increase in Materials Price, 1974-77 . . . Increase in Materials Price, 1984-85 . . . Indices for Construction Inputs

--Individual Formulae . . . . . . . . . . . Indices for Construction Inputs

--General Formula . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Industrial Labor Force . . . . . . . .

Page

171 172 173 174 175 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191List of Exhibits (continued)

6.1 Construction Participants and their

Arrival Times . . . . . ... 192

6.2 State of the Non-System of Arab Construction ... . . . 193

6.3 Evolution of the Number of Engineers .. ... 194

6.4 Dar Al-Handasah Shair and Partners --Major Projects ... . . . ... 195

6.5 Projects Undertaken by Dar Al-Handasah Taleb ... 199

6.6 Major Projects Undertaken by Rafik El-Khoury and Partners .. ... 200

6.7 Specifications According to US and UK Standards . ... ... . . 201

6.8 Profitability of a Contract from the Contractor's Perspective ... 202

6.9 CAT -- List of Key Staff ... 203

6.10 CAT -- Schedule of Construction Equipment ... .. 204

6.11 Multiplier Factors for Updated Values of Contracts . . . ... 206

6.12 CAT -- Operation Profile ... 207

6.13 CAT -- Major Projects. ... . 208

6.14 Kettaneh Freres -- Major Projects . ... 210

6.15 Oger Liban -- Manpower Distribution ... 211

6.16 Oger Liban -- Schedule of Equipment and Major Projects ... 212

6.17 Zakhem International -- Selected Clients and Financial Performance ... 213

6.18 Almabani -- Selected Projects and Financial Performance . . . . . . . . ... 214

6.19 Societe Nationale d'Entreprise --Major Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ... 215

6.20 Student Enrollment in Schools of Architecture . . . . . . . . ... 216

List of Exhibits (continued)

7.1 Model for Disaggregating Construction. ... 217

7.2 Major Public Projects, 1960-1975 . . . . . . . . . . . 218

7.3 Average Prices of Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

9.1 Beirut Rehabilitation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 220

9.2 The Reconstruction Expenditure Program . . . . . . . . 221

9.3 The Tunis Pledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of the

construction sector and its main participants in the Lebanese economy. It comes at a time when the country as a whole is torn into bits and pieces and when, following eleven years of war, the economy is in

shambles: the industrial sector is virtually crippled, the wheels of commerce are slowly grinding to a halt, and the national currency is fast becoming worthless.

In this tormented context, the construction sector has maintained its resilience, and all its components are present in Lebanon: local construction materials industries, professionals, contractors,

consultants, clients, financing institutions, the legal system, and the specifications and classification systems.

This work is subdivided into nine chapters. The first two chapters constitute an approach to Lebanon and its people. The third chapter covers in detail each sector of the Lebanese economy, including industry. The role of construction in economic development is then reviewed. This is followed by a chapter on construction inputs, including materials, labor, and finance. Chapter VI covers the wid- range of construction participants and gives a detailed account of the major Lebanese

consulting and contracting firms. Demand and outputs are then examined, with particular attention to the housing problem. Chapter VIII is

concerned with such issues as building codes, specifications, and

taxation. And the final chapter is devoted to the reconstruction and to future prospects of the construction sector in Lebanon.

U.S. official. The following pages will hopefully succeed in confirming this statement.

I. GEOGRAPHY

The republic of Lebanon is an independent state located on the

eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Consisting of a narrow strip of land about 135 miles long (215 kilometers) from north to south and 20 to 55 miles wide (30 to 90 kilometers) from east to west, it is bounded to the north and east by Syria and to the south by Israel (34).

With an area of 3,950 square miles (10,452 square kilometers), Lebanon is one of the world's smaller sovereign states, and yet its physical geography is extremely complex and varied.

Four different physiographic regions may be distinguished: a narrow coastal plain along the Mediterranean Sea, the Lebanon Mountains (Jabal Loubnan), al Biqa (Beqaa) Valley, and the Anti-Lebanon and Hermon ranges running parallel to the coastal mountains. In parallel, the country encompasses three major types of historic communities: the Mediterranean coastal cities, the villages and towns of the mountains of the Lebanon range, the settlements of the flat farmlands of the eastern Beqaa Valley, and the northern plain of Akkar. The Mediterranean communities have consistently enjoyed close trade relations with other cities along the coast while the mountain villages and towns always provided a myriad of refuges for political and theological dissidents. Writing of the

Lebanese mountains, Gilmour (82), quoting a famous historian, remarked that "the steepest places have been at all times the asylum of liberty." The Beqaa and Akkar, in turn, have long maintained close links with the inland cities of Syria as well as with the coastal areas and the

of peoples. The Phoenicians first made the coastal cities famous. Then the Persians and the Romans, successively, settled in the coastal plain and the Beqaa Valley. As Christianity spread, the local pagan beliefs were gradually overtaken by allegiances to the Patriarchs. The military forces of Islam defeated Byzantine rule in the early 7th century, thereby binding the existing Semitic communities to the Arab world and promoting

eastward-looking links which survive to this day. Over the following centuries the coastal cities, whose links with the surrounding Islamic empire were all-important, tended to house the orthodox -- whether the Orthodox Sunnis of Islam or the Orthodox Christians. From the 7th century onward, the mountains attracted both heterodox Muslims of the Shia sect (together with the followers of the closed Druze religion) and the heterodox Maronite Christians. In the 13th century, this latter group was distinguished by its attempts to forge links with Rome and Catholic France, ties which remain today. Today, Lebanon still serves as a refuge. However, this time it was the burgeoning cities of the coast rather than the remote mountain areas which attracted successive waves of political refugees: the Christian Armenians and Assyrians who have now been partially absorbed and granted nationality; the Muslim Kurds; and the Palestinians whose massive presence here has come to constitute a major factor in the country's politics (123).

The areas of concentration of Lebanon's principal ethnic and

religious groups are identified in Exhibit 1.1 (132). Now, the country's major cities are (cf. map): the capital, Beirut (population 1.1

million); Tripoli (240,000); Sidon (110,000); Tyre (60,000), and Zahlah

(55,000) (157).

century the Greater-Beirut would have gained such gigantic proportions as to absorb the totality of the country, ultimately transforming it into what he called a h'ige "Libanville."

Minister Babikian (13), for his part, realized that the creation of these "belts of misery" around the major cities, and especially around Beirut, provided a huge human reservoir from which most fighters were recruited.

In this context, it is essential to note that Lebanon's geographic location has, nearly always throughout history, constituted a "de-facto" handicap for the country.

Right now it lies between Israel and Syria, and there has always existed a suspicion that Israel, on one hand, coveted the lands of the south and the waters of the Litani River, and that Syria, on the other, wished to maintain whole parts of the country under its sway.

Historically, Lebanon has been shaped by its location as the junction of the desert and the sea, of Asia and the Mediterranean, of Muslim East and Christian West, of Istambul and the influence of Western powers, of French and British interests. It is not some remote mountaintop deep in an inaccessible jungle: it straddles routes of major persisting

II. PEOPLE

Lebanon has a heterogeneous society composed of numerous ethnic, religious, regional, and kinship groups. Primordial attachments and local communalism antedate the creation of the present territorial and political entity and continue to survive with remarkable tenacity. To this effect, Gilmour (82) notes that "In Lebanon, a man's loyalty goes

first to his community. If he had to choose between that and the state, it is the state that generally loses."

2.1 Ethnic and Linguistic Groups

Ethnically, the Lebanese compose a heterogeneous group in which Phoenician, Greek, Byzantine, Crusader, and Arab elements are

discernible. From the 7th century onward, there has been an influx of tribes from the Arabian Desert. While the dominant strain in the mountains is related to the Armenians of Asia Minor and the Caucasus, inhabitants of the coastal towns and the Beqaa Valley are descended from inhabitants of the hinterlands of Syria, Palestine, and Arabia (34). Arabic is the national language, but French and English are widely spoken, and many Lebanese are trilingual. About 5 percent of the

population is Armenian-speaking, and the Syriac is used in the liturgies of some of the churches of the Maronites (Roman Catholics following an Eastern rite).

is considered to be the highest in the Arab world, reaching 90 percent in the city of Beirut (69). Since the second half of the 19th century, intensive intellectual activity has flourished in Lebanon. Foreign missionaries established schools throughout the country. Beirut became the center of this renaissance with the American University of Beirut, founded in 1886, and the French St. Joseph's University, founded in 1875. Meanwhile, the formation of an intellectual guild gave a new life to Arabic literature after a period of lethargy under the Ottoman Empire. The new intellectual era was also marked by the appearance of numerous publications and by highly prolific press activity.

2.2 Religious Groups

In those instances where religious representation is

institutionalized in the political system, it is of the utmost importance to know the size and other demographic features of the various religious groups (162). Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Lebanon's social

structure is its varied religious composition. For many, this

characteristic explains much of the country's tormented history. Others, such as Cobban (48), argue that if there were no sects, there would be no Lebanon. Both arguments, rparadoxically, seem to hold. Historically, Lebanon has always served as a refuge for persecuted Christian and Muslim sects. From the mid-llth century onwards, five communities (Maronites, Shiites, Druze, Sunni Muslims, and Greek Christians) have been entrenched within the area of present-day Lebanon. Successive outside invaders came and went. Only these five major communities stayed on forever, with their relative strengths rising and falling according to changes in

demographic, social, and regional realities and the geographic boundaries between their spheres of influence shifting with "the winds of history"

(48).

During the French Mandate preceding Lebanese independence, the French conducted two censuses, in 1922 and 1932, respectively. Since then, no official census has been conducted by the Lebanese government. The omission has not been an accident. As Murray (124) notes: "A result which exposed the present structure as built upon premises no longer valid could set up irresistable pressure for changes."

As a consequence, the religious composition of the Lebanese

population was never ascertained. Indeed, the question of how to define the Lebanese population continues to be unresolved. The possibilities range from counting only those Lebanese citizens who reside permanently in Lebanon to counting all Lebanese citizens and their descendants

regardless of place of residence (162). The Lebanese living abroad tend to be disproportionately Maronite and it has been estimated that there are close to 5 million Lebanese living abroad, compared to a maximum of 3 million persons in Lebanon itself (45).

In any case, fragmentary evidence suggests that Muslims now outnumber Christians; several past estimates, together with projections of the future religious composition of Lebanon, are provided in Exhibits 2.1 and 2.2.

2.3 Demography

As stated above, there has been no full census since 1932.

Demography Yearbook (153)), give only an approximate picture of the

reality of the Lebanese demography (population living in Lebanon). Note: all population figures are given in millions.

1962 = 2.11 1970 = 2.47 1977 = 2.76 1963 = 2.15 1971 = 2.54 1978 = 2.73 1964 = 2.18 1972 = 2.60 1979 = 2.70 1965 = 2.21 1973 = 2.66 1980 = 2.67 1966 = 2.24 1974 = 2.74 1981 = 2.65 1967 = 2.27 1975 = 2.77 1982 = 2.64 1968 = 2.34 1976 = 2.76 1983 = 2.64 1969 = 2.40

From 1962 to 1967, the population increased by approximately 30,000 people per year. Between 1967 and 1974, a particularly prosperous period

for the country, there was a population increase of about 65,000 persons per annum. Finally, from 1975 (when the war started) onwards, the

population has been declining, partly because many Lebanese were killed and partly because many others left the country (the 1983 annual growth rate was approximately -0.3 percent). Although no official figures are available, fragmentary evidence suggests that more than 100,000 Lebanese have been killed and that approximately 600,000 persons have fled the country during the strife. For the sake of illustration, a graph showing the evolution of the population residing in Lebanon between 1975 and 1981 is provided in Exhibit 2.3 (26).

Not surprisingly therefore, an important brain drain has emptied the country of its human resources; this sensitive question will be dealt

with in greater detail in later chapters of this thesis.

Now, one of the most salient demographic features of Lebanon is the uneven distribution of its population. While the country has an overall density of more than 800 persons per square mile (or about 300 per square kilometer), density soars to about 69,000 per square mile (27,000 per square kilometer) in the Greater Beirut (34). Since the 1930s, the population of Beirut has increased ten-fold. By 1970, Beirut was one of the most overcrowded cities in the world, outside eastern Asia (82). This could be explained by the vast internal migration, of which

two-thirds had been toward Beirut. Now, if the 1975-76 civil war led to a substantial return of people to their villages, the renewed fighting in the 1980s threw hundreds of thousands of persons out of their homes. As a result, an informed source (17) states that more than one-third of the Lebanese population is being relocated, Christians and Muslims being grouped into distinct zones.

III. ECONOMY

"There is a common belief, even among respected authorities, that the Lebanese economy defies all statistics and forecasts...." (12)

3.1 General

This chapter has two broad aims: the first is to describe the

record of postwar economic development in Lebanon up to 1974, i,.e., prior to the civil war of 1975-76, outlining some of its basic achievements and flows; and the second is to cast a look at the future in the aftermath of the war. Indeed, the two objectives are closely related, in that past performance should act as a guide for the future.

Until the starting of the clashes in 1975, Lebanon occupied a unique position as the de facto financial and commercial capital of the

Middle-East. As briefed by Minister Cassir (41), the Lebanese economy rests on six supports:

1. Freedom of foreign-exchange transactions and secrecy of bank accounts

2. Geographical location of Lebanon

3. Private initiative

4. Friendly and commercial relations with most countries

5. Oriental and Occidental culture of the Lebanese

6. Entrepreneurship and experience of the Lebanese people.

Arab heritage of risk and adventure, Lebanon was once regarded as a bridge between the West and Near-East. At that time, people would describe the country as the Switzerland of the Middle-East and would speak of the Lebanese miracle. Pragmatically, Azhari (12) notes that the miracle wouldn't have occurred had considerable funds not been available due to extraordinary circumstances in the region.

First, World War II left the Middle-Eastern peoples with large

amounts of savings due to excessive spending by the Allies. A major part of these savings was either spent in Lebanon or channeled through

Lebanese middlemen.

Second, after the Israeli occupation of Palestine in 1948, Lebanon benefited from the shift of activity from the port of Haifa to Beirut and

from a newly-acquired role as a petroleum terminal. Also, Lebanon benefited from an inflow of a great number of educated and experienced

Palestinians (those were preceded by the Armenians earlier in the

century). The Lebanese economy then benefited from the blockade of the Suez Canal from 1967 to 1974 which enhanced the position of Beirut as a transit port for the Middle-Eastern hinterland. In the period from 1963 to 1972, transit traffic already represented nearly nine-tenths of the country's foreign trade.

Third, the breakup in 1950 of the Lebanese-Syrian Custom Union widened the geographical basis and nature of the Lebanese trade from a limited bilateral relation with Syria to a multilateral relation with European and other countries.

Fourth, the expansion of the petroleum industry in the Arab

Peninsula at the beginning of the fifties, and the increasing returns to Arab countries, created a large capital inflow which was mainly directed

to Lebanon for saving and investment in real estate, trade, tourism, and other services. The freedom of repatriating capital and profit

contributed to place Lebanon in a favorable position vis-a-vis other Arab countries.

Fifth, a series of revolutions in the Arab world started in 1949 and caused a flight of funds out of these countries. The growth of Lebanon's deservedly renc.wned service sector grew largely out of the country's attractiveness as a safe and financially liberal refuge for capital fleeing political and economic chaos reigning in the Middle-East during the 50s and 60s. In 1954, Lebanon's position in this respect was

enhanced by the abrogation of all restrictions on foreign currency operations (Government policy is to permit free exchange of currencies, precious metals, and monetary instruments domestically and in foreign trade). In 1956, a bank secrecy law was enacted which further stimulted the inflow of Arab capital (54, 123).

Finally, it is essential to note that the most important factor in Lebanon's impressive economic expansion remains a large supply of skilled entrepreneurs (see also: Work Force), a tradition embedded in the

country's history and manifested among the largely succcessful Lebanese expatriate communities in many parts of the world (146).

Looking at the period 1950-1974 as a whole, the country's economic performance proves to be admirable. Instead of going out after business, noted the editor' of the Engineering-News Record (69), Lebanon is

attracting business to itself. More recently (February 1983), US

Ambassador Dillon (54) described the country's market as being one of the most liberal in the world.

rate of growth in real terms averaged over seven percent per annum (82). In the 1960s and 1970s, the financial performance had been more

impressive than in the 50s but the average rate of growth in real terms dropped, averaging about five to six percent annually in real terms. Further, Makdisi (106) notes that, viewed in the context of the

performance of other developing countries, Lebanon's rates of growth, although decreasing in real terms, are considered highly satisfactory.

Another indicator of the country's prosperity is its high national income per person. It grew from approximately $250 in 1974 (34) to $1,200 in 1979 (58). To this effect, Gilmour (82) notes that Lebanon's per capita income was higher than that of every Asian country with the exception of Kuwait, Israel, Singapore, and Japan, and of every African country except South Africa and oil-rich Libya.

This was on the credit side of the picture.

Now, Azhari (12) identifies the two leading "strategies" of the Lebanese economy: the "laissez-faire" under its most archaic form on one side (this was a reflection of the country's traditional political pragmatism and democratic openness to its regional environment (64)), and a bunch of "providential" laws on the other. As a consequence, the

Lebanese government, without adequate forecasting or planning policies, was always without strategies when a crisis would appear. Also, it was always blamed for ill-managing its resources and inefficiently using its assets. For example, there are too many government employees by far, notes Azar (11), and few of these really perform. Thus, Lebanon has one teacher for every seven students, a very high ratio. No one knows how many of these teachers teach, however. Some officials (81) went a step

Lebanon liberalism meant anarchy.

As an example, according to one economist, private business was evading three-quarters of its taxes while the men of liberal professions were paying as little as a tenth of the money due from them (92).

Another strain on the finances of the country is the non-collection of custom duties and the non-payment of bills (water, electricity). As far as power is concerned, the State loses 1.25 Lebanese pound per kilowatt produced. In 1985, the production was 3.25 billion kwh, or in other words, a loss of 4 billion Lebanese pounds (61).

Another striking example of the prevailing anarchy: According to the Dean of Engineering at the American University of Beirut, only five percent of the architects putting up the new buildings are properly

qualified (83).

A further drawback of the Lebanese economy is that the country's development is marked by widening disparities among income groups, geographical regions, and economic sectors. This uneven pattern of economic development was first highlighted in the IRFED survey (89) conducted in the early sixties.

Thus, according to one source (85), Lebanon's laissez-faire economy brought in a great deal of capital that never reached the poorest

elements of society. Slowly, the country became an economic pyramid, with large gaps separating the few wealthy at the top from the many poor at the bottom.

To this effect, Professor P. Khoury (101) noted that in 1970, 50 percent of the GNP was distributed over only 5 percent of the population.

Added to this dismal picture were high inflation in the early 70s (approximately 25 percent (157)) and wages that did not keep pace. After

1973, when oil prices climbed, petro-dollars came pouring into Beirut, adding to the upward pressure on prices. For a poor Lebanese, or one on a fixed salary, the situation became quickly intolerable. In 1974, the disenchantment materialized in labor disputes -- fifty strikes in one thirty-day period (85).

3.2. Impact of the War on the Lebanese Economy

In attempting to assess the economic impact of the war, one major constraint is the non-availability of reliable estimates of the damage which was sustained by the Lebanese economy. Moreover, by the time this paper is read, renewed fighting would have resulted in additional

destruction of housing, infrastructure, and industrial and commercial establishments in most areas of the country.

Nonetheless, the drawing up of a meaningful picture of the effects of the war can still be undertaken. These have manifested themselves in many interconnected areas and in various tangible and intangible forms which might be categorized as follows (106):

1. Severe and widespread damages to physical assets, and therefore, existing capacity of production, e.g. damage to factories, farms, business establishments, public utilities, etc. In 1984, US Ambassador Bartholomew (14) estimated the damage at about $33.2 billion (cf. Reconstruction).

2. Drop in national income owing to (a) damage of physical capacity, (b) disruption of the transportation network of domestic and foreign

trade channels, (c) departure of business firms and capital (cf. Foreign Firms in Lebanon), (d) reduced governmental and private expenditures.

As a result, a World Bank publication (165) gives the following figures:

GDP (Average Annual Real Growth Rate, in Percent)

1950-60 1960-70 1970-early 80s

2.6 4.6 -5.4

The negative entry in the table is explained by the above factors. At the eve of civil war (1975), the GDP was about $3.2 billion (58). In 1977, it dropped to $2.6 billion (157).

In 1983, a general mood of optimism was enhanced by the unusually assertive Western support for the peace process in Lebanon, which generated greater corfidence in the country's future and thus in its economic recovery. As a consequence, the GDP for 1983 again reached $3 billion (158). However, the GDP, although not accurately quantified, was reckoned to be decreasing ever since (41).

3. Drop in the level of employment and exodus from Lebanon of the labor force (cf. Work Force).

4. Adverse intangibles -- in particular: (a) loss of confidence on the part of the private sector, (b) loss of human resources, and (c) changed distribution of asset holdings as a result of physical distruction and/or pillage.

5.

Adverse financial developments manifested in (a) in the reduction of central banking activity to a minimum level, (b) temporary closure of a number of banks, and (c) increased inflationary pressures (discussed below).6. The rupture of administrative set up, ministries and public bodies ceasing to function as unified organs.

Nonetheless, El-Khazen (64) notes that the economic situation could have been worse were it not for the flexibility of the Lebanese economy to adjust to changing market forces, and, more importantly, to various socio-economic dislocations provoked by the war since 1975. Were it not for that element of economic flexibility, a decade of instability would have resulted in even more devastating consequences than the ones that have already taken place.

However, the picture changed drastically in early 1984 when the war shifted from the political and military fronts to the socio-economic fronts. Today, Lebanon's economy is showing unprecedented signs of

strain, and the country's performance in many ways approximates that of a classical Third World country (high unemployment rate, increasing

inflation, large deficit, and depressed exports) (64).

to be around 70 percent (before the war it was typically around 2.5 percent (164)). The deficit of the balance of payments, in turn,

amounted in 1985 to $1.5 billion, and many economists suggest this figure be multiplied by a factor of 10. Finally, the "Direction Centrale de la Statistique" blew the whistle when comparing an average salary in Lebanon (7,000 Lebanese pounds or $400 at November 1985 rate, and $180 at June 1986 rate) to the $1,000 an unqualified worker earns in the United States

(136).

As it can be seen, the economic situation seems to be deteriorating daily. For the first time since World War I, the population is showing unprecedented signs of strain in coping with the prevailing situation. Thus far, the government's action seems completely crippled by a host of external constraints and internal dissensions.

Corrective measures, when taken at all, would come too late, which magnified the problems and made the task of economic recovery extremely difficult. Among these measures was the decision to lift the fuel price subsidy. To this effect, sources (41) and (78) noted that this unpopular measure was aimed basically at limiting the drain on public foreign

exchanges reserves which, in 1985, reached an equivalent of 8 billion Lebanese pounds (Exhibit 3.1). The decision stems from a will to restore real prices and reduce wasteful consumption of fuels, which became all the more imperative after the depreciation of the Lebanese pound which inflated the LL value of the fuel import bill ($700 million for 1985).

Higher fuel prices were understandably resented by consumers but the measure was meant to reduce fuel imports and domestic consumption. There are two ways of reducing the country's oil bill: an energy-saving

adopt or enforce an energy-saving policy. Therefore, raising fuel prices seemed the only possible alternative.

Cancelling the fuel price subsidy was an unpopular measure indeed, but the need to rescue the Lebanese economy calls for painful choices. These choices would still have to be made even if the war came to an end; they would then be somehow less painful. If peace were restored, the

country would still have to deal with either the economic or the social crisis. Without peace the nation stands to confront both crises

simultaneously.

As a consequence, while waiting for better days to come, Lebanese are learning to adapt to a poorer life.

In the following paragraphs, each economic sector will be reviewed separately. However, as noted by Tasso (151), the general picture of the Lebanese economy cannot be obtained by simply combining the "shares" of its various sectors, since there are so many "invisibles" and other side effects that can never be quantified. The analysis that follows should therefore be viewed in that spirit.

3.3. Industry

In most countries, developed or developing, industry performance falls short of the expectations of government and of society in general (63). This fact is particularly true in Lebanon where the safe, fast, and sizeable returns of the commerce and services sectors diverted most funds from the inherently "risky" industrial sector.

The development of industry in Lebanon is fairly recent. The introduction of large quantities of foreign products in the Middle-East

-31-during the 19th century had actually curbed down the activities of a flourishing Lebanese handicraft industry. Thus, only in the past forty years has the country experienced conditions favorable to industrial development.

The creation of an economic union between Lebanon and Syria in 1922 is considered to be the starting point of the Lebanese industry. The outbreak of World War II and the ensuing close of all maritime channels effectively stimulated the Lebanese industrial community. All imports came to a halt, hence the population needs combined with large orders sent by the armies stationed in the country ensured a full capacity of industrial work with substantial gains. These profits contributed to the enlargement of existing industries and the creation of new ones:

petroleum refineries, industrial machinery, foodstuff, textile, and glass industries. The growth of the industrial sector continued at a fast rate after the end of the war. Today industry fills the second place in the Lebanese economy, behind the services and trade sector. The most

important industries are: foodstuff, textiles, cement, metallic minerals, wood and metal products, and oil refining (111, 123).

But an important gap remains in the field of industrial management. Perhaps the most significant obstacles to long-run economic and social progress are the lack of effective administrative and planning

institutions.

Thus far, the government has paid little attention to the industrial sector, and corrective measures, when taken at all, would come too late, magnifying the problems and making the task of economic management in later years extremely difficult.

Lebanese Industrialists, in March 1971 a five-year plan was approved by the government. Also, by virtue of decree 2351 dated December 10, 1971, a National Bank for the Industrial and Touristic Development was created. Its main goal was to sustain the development of these two sectors (38). Both these actions remained largely insufficient, and Lebanese industry has literally had to survive by itself. Its role in the economy was always subservient to commerce, partly because of a shortage of raw materials and partly because the free trade policy which suited

commercial life effectively prevented many industrial ventures from getting off the ground. The Industrialists' Association fought hard for higher tariffs, but was invariably defeated by the far stronger

commercial lobby. If there is a market for something in Lebanon, then it is imported, irrespective of the fact that Lebanese industrialists might be trying to manufacture and market a similar product (82).

The industrial sector is also facing problems related to the population and the size of the country. The small Lebanese population implies a limited domestic market, which means that industrialists cannot take advantage of any economies of scale unless they are primarily

export-oriented. The size factor therefore dictates to a large degree what type of economic development is possible, and means that, in the absence of any regional economic integration, heavy industry for example would seldom be a viable proposition. Instead, light industries, with their low overhead costs, appear to be a more appropriate alternative, as the least cost unit of output can be manufactured on a small production run (123).

However, the refining of imported crude oil seems to be the exception to the rule, since it constitutes a major portion of the

Lebanese industry. Because of the country's advantageous geographical location, two pipeline systems connect Lebanon to the oil-rich Arab hinterland: (a) The pipeline system from the Kirkuk fields in Irak via Homs to the terminal at Tripoli in Lebanon (and Banias in Syria) consists of three separate pipelines with a total annual capacity of about 55 million tons. Throughput in 1975, the last full year of operation,

amounted to 48.4 million tons to Homs and from there 27 million tons to Banias and 19 million tons to Tripoli. (b) The Trans Arabian Pipeline Company (Tapline) from the Abu Hadriya fields in Saudi Arabia to the terminal at Saida in Lebanon consists of one pipeline with annual

capacity of approximately 25 million tons; throughput in 1974, the last full year of operation before the Lebanese civil war, amounted to 11 million tons.

The reduction in local production led, as expected, to substantial oil imports (Exhibit 3.2) at high costs, which created the dramatic crisis discussed above.

In this context, it is worth noting that in April 1975, the Ministry of Industry and Oil announced that commercially workable oil reserves had been discovered in the Akkar plain, the western region of the Al-Beqaa Valley, and in the Mayruba area near the central coast. Bids for concessions were posted pending the end of the war (34).

Typically, between 1960 and 1975, the industry mobilized about 25 percent of the work force:

Industry as % of Work Force (source 165)

1960 1965 1970 1975

As discussed above, the industry was steadily expanding until the start of the clashes in 1975. As naturally expected, the industrial sector was hit very hard by the war. The Lebanese Industrialists' Association estimates that 80 percent of factories and workshops which

are still operating -- perhaps more than 3,000 establishments -- have

dismissed more than half their employees (14). The combined effect of this huge dismissal and the voluntary exodus of tens of thousands of workers was a drop of about 60 percent in the industrial work force (28). Another source (54) discloses equally alarming figures whereby the number of industrial workers is believed to have dropped from a peak of 125,000

in 1975 to 50,000 by 1978-79.

Now the destruction of most industrial areas, especially in the Greater Beirut where about 70 percent of the industrial concerns are located (Exhibit 3.3) had a dramatic impact on the national economy. In all, production is reported to have dropped by 70 percent (14).

The situation of the Lebanese industry has somewhat changed after late 1984 when the Lebanese pound depreciated drastically vis-a-vis the US dollar and other foreign currencies (see Banking). The only positive effect of this depreciation was, as noted by the Minister of Economy (41), an increase in the industrial exports, since the price of Lebanese products was becoming more and more competitive.

Thus, as noted by Babikian (13), the industry benefited from an indirect and substantial subsidy. This new element had an immediate impact on the share of the industry in the Gross Domestic Product of the country. Until 1983, it was typically around 15 percent (41, 99, 157). Today, due to the above factor and to the erosion of other sectors

(commerce, services, and agriculture), Khayat (99) estimates it at approximately 40 percent and considers that industry in Lebanon is finally about to assume its role as a dynamic and leading sector of the economy. Exhibit 3.4 shows the value of production and effective export between 1974 and 1984.

3.4. Commerce and Services

The country has a centuries-old tradition as a trading nation. At one time it was considered the commercial center of the Arab world. Until 1974, trade continued to reflect the mercantile character of the Lebanese economy. Almost anything for sale anywhere could have been purchased in Beirut. An enormous propensity to consume generated a huge trade deficit (see below), which was covered partly by "invisible" items such as foreign remittances and transit and tourist services.

Also, trade has been encouraged by generally low tariffs, by various facilities offered by foreign (US and European) exporters (2), and by free port area, which accommodates a large volume of duty-free transit trade and provides facilities for the warehousing and processing of imported goods before their shipment to final destination (7). As mentioned above, one major weakness of the Lebanese economy is the permanent deficit of the balance of trade, which was continuously

sustained by remittances from Lebanese working abroad, principally in the Arab states. Exhibit 3.5 shows the transfers of Lebanese working abroad up to 1982. Except for the period of the civil war (1975-76) and for the renewed fighting in 1978, the transfers have been increasing steadily. In 1983, Azar (11) estimated that 200,000 Lebanese were working in the

Arab countries, and they remitted to Lebanon approximately $150-200 million a month. Since then, due to the general slump in the Arab

economy on the one hand and loss of confidence in the country's future on the other, this major source of income dried up rapidly (Sarkis (144) estimates that drop to be as serious as 80 percent). As a result, the deficit of the balance of payments (for the second time since

independence, the first time being 1984 (41)) amounted in 1985 to $1.5 billion and many economists suggest this figure to be multiplied by a factor of ten (136).

In the early 70s, the exports "covered" only a third of the imports (112). The gap further widened during the last several years, and recent IMF statistics (88) show that in 1983, the imports amounted to Lebanese pounds 17.7 billion whereas exports amounted to only Lebanese pounds 3.9 billion. In the same context, Lissan-ul Hal (105) published statistics

(October 1985) whereby the exchanges between Lebanon and Turkey, for example, are in a ratio of 1 to 100.

The sharp decrease in Lebanese exports is due mainly to a general decline in the economic activity in the country and to the loss of much of Lebanon's traditional market, particularly Saudi Arabia and Irak. US Ambassador Bartholomew (14) notes that exports to Saudi Arabia decreased as a result of the restriction on the import of goods from or via Lebanon for fear that they may have been generated in Israel. Moreover, the Kingdom restricted its imports from Lebanon to the products of only 177 factories, out of a total of more than 4,000 Lebanese industrial

concerns.

As far as work force is concerned, various sources (e.g. 7, 41, 112) agree that about one-fourth of the Lebanese work force is involved in

trade.

In the sixties and seventies, trade and services contributed to more than two-thirds of the country's GDP, or in other words generated more than twice the yield of all other economic sectors combined (Exhibit 3.6; sources 7, 41). This situation remained almost unchanged during the war since the country has literally survived from its imports. However, because of the erosion of the Lebanese pound vis-a-vis other currencies and the subsequent major role played by the industry in the Lebanese economy (this zero-sum game between trade and industry was discussed also in previous sections), the share of the trade and services sector in the GDP (1985) was only about 40 percent (41).

In the same context, other factors tend to indicate that the

merchant class might lose its dominant position. For example, there is the stiffening opposition that the Lebanese trading middleman is meeting in many Arab countries. The Arab world is finding it can live more and more without Beirut. As a city of commerce and entertainment, it once outclassed on all levels any other center in the region. But its rule in the 60s and early 70s might not be repeated in the 80s. One alternative, Bahrain, is already boasting one of the largest offshore banking centers in the world. The Gulf, as the focal point of oil interests, is learning to serve itself, with accommodation, communications, and commercial

services. Even the entertainments are improving there. Business is moving east. Finally, serious efforts are made to divert the

import-export and transit trade from the Beirut port to Lattakia in Syria and Akaba in Jordan (123).

A last drawback, as far as internal trade is concerned, was identified by Abi-Saleh (2). More than ever before, competition is

(counter-intuitively) tending to increase prices. This is so because reduced sales and higher fixed costs, given a desired profit margin, naturally dictated higher selling prices.

3-5. Banking

Various factors have combined to make Beirut the financial center of the Middle-East and one of the largest free foreign-exchange markets in the world. Fundamental to Beirut's appeal as a financial center has been the stability and convertibility of the Lebanese pound and the absolute

freedom in foreign exchange transactions. Lebanese banks accept deposits in practically any currency, and no problems are involved in moving funds into and out of the country.

The total secrecy of bank accounts is strictly enforced.

Theoretically and legally money from the outside can seek refuge in Lebanon regardless of what its sources, be they legitimate or unethical. Another attraction that creates confidence in Lebanese financial

transactions is the great extent to which banks live up to the

commitments they make to their customers. Added to this are the very few demands made on incoming foreign capital in terms of taxes and other tolls, along with the concurrent high interest rates offered (125).

Until 1964, banks were totally unregulated. There was no special banking law, no central bank, and no restriction whatsoever on the

opening of new banks. No rules governed minimum reserve ratios and banks were not even asked to produce regular balance sheets. This situation led to the creation of many small banks (in 1951 there were five banks in Beirut -- fifteen years later there were 93 as well as a large number of

branches of foreign banks (87)).

Together with Hong Kong, Lebanon can claim the largest number of separate banks per capita in the world (7). In October 1966, a banking crisis was precipitated by the collapse of the largest Lebanese-owned bank, the Intra Bank, which accounted for about 40 percent of deposits with Lebanese-owned banks. This crisis led to the adoption of a number of laws designated to deal with the situation and to provide the legal basis for banking reform. As a consequence, the number of registered banks was limited to 92 (94).

The resilience of the Lebanese banking system has, after ten years, amazed many observers. (As an example, the consolidated balance sheet of banks in Lebanon increased eight-fold between 1978 and 1984. Even though the effect of inflation and depreciation is taken into consideration, this increase remains, in real terms, substantial (94). Also, in 1981, the ratio of the consolidated balance sheet of Lebanese banks to the Gross Domestic Product was egq-l to 231 percent as compared to 40 percent in France, 54 percent in the USA, and 120 percent in Switzerland (22).) Its disintegration today will surprise few. Exhibits 3.7 and 3.8 show the evolution of the US dollar on the Lebanese market between 1975 and

1985. Except for 1982 when a general mood of optimism generated greater confidence in the country's future, the Lebanese pound has been declining and then sharply dropping against all major currencies. The causes of this rapid deterioration in the value of the currency are not difficult to identify. In addition to the chronic political instability and

general economic slowdown, one can name: excessive government spending, irresponsible monetary policy, increasing national debt, growing

to obtain a new (or even the already promised) foreign aid, government policy arbitrarily favoring one sector of the economy (commerce and

services) to the detriment of others (industry and agriculture), etc. As stated by Sarkis (144), today should have been better prepared yesterday. Confidence in the national currency was further undercut in reaction to the Central Bank's loss of credibility in the last two years. As explained by its governor (126), the Central Bank's (dualistic) policy is to maintain the parity of the pound on one hand (which means the

selling of some of its reserves) and to preserve precisely these reserves for worse days, on the other.

On the credit side of the picture, Chaib (44) notes that continuing instability in Lebanon has created strong incentives for Lebanese bankers to expand abroad. Thus, by 1983, thirty Lebanese banks were established abroad. This helps sustain the profitability of banks, while enhancing general confidence in the banking system. It also facilitates the return of capital from foreign sources to Lebanon once the reconstruction

process begins.

3.6. Agriculture

Roughly a quarter of the country's land area of approximately 4,000 square miles is suitable for agriculture (7). Much of this agricultural land consists of man-made terraces on the steep slopes of the Lebanon mountains. About half the farm acreage is located within the Beqaa

Province in the semi-arid valley between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges. Soils are generally poor, and a long dry summer season makes irrigation imperative for intensive cultivation.

As far as output is concerned, the combination of topography, climate, and irrigation has made possible the production of a wide variety of crops, of which the most important by value are fruits and vegetables. A large portion of this output is exported, primarily to Arab countries.

Aware of the unfavorable situation confronting many farmers and of the need to raise agricultural productivity and output, the government has gradually modified its laissez-faire attitude. Its most important

realization is the formulation of a "Green Plan" (1964) to restore neglected land and to promote reforestation. In addition to the aid of international agencies, such as the United Nations Development Program and the Food and Agriculture Organization, Lebanon has undertaken a number of projects involving land reclamation, irrigation, and the introduction of new crops and better farming methods. It has also promoted the formation of farmers' cooperatives, instituted some farm price supports, and helped finance the sale of some products abroad.

As a result, between 1965 and 1985, 22,000 hectares of land were improved, reservoirs with a capacity of 5.5 million cubic meters and roads with a total length of 950 kilometers were constructed (9).

Still, performance falls short of expectations. The share of agriculture in both the work force (WF) and the GDP has been declining steadily.