*

/

\

*

LIBRARIES

^oSTtf^

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

HB31

DEWEY

.M415

1.1

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

AGGREGATE

VOLATILITY

IN

MODERN

LATIN

AMERICA: CAUSES

AND

CURES

Ricardo

J.Caballero

Working

Paper

00-11

June

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection

atMASSACHUSETTSINSTITUTE

OFTECHNOLOGY

OCT

2

5 2000

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

AGGREGATE

VOLATILITY

IN

MODERN

LATIN

AMERICA:

CAUSES

AND

CURES

Ricardo

J.Caballero

Working

Paper

00-11

June

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

atAggregate

Volatility

in

Modern

Latin

America:

Causes

and

Cures

By

Ricardo

J.Caballero

2May

31,

2000

I.

Introduction

Latin

America

hasexperienceddeep

transformationsduring the 1990s. Inmany

countries of the region traditional imbalanceshave

been

largely abated, privatizations are widespread,openness

of both tradeand

financial accounts hasbeen

largely accomplished, supervisoryand enforcement

institutions are steadily improving, pension systemshave been

modernized,and

so on.Symptoms

of successabound.An

important exception to this rosyscenario is theuntamed and widespread

volatility of realand

financial variables.3 In afew

countries, this volatility is still explainedby

thetraditional maladies that plagued Latin

America

in earlier decades—

namely,

chronic fiscal imbalancesand

political instability—

perhapsdue

to also chronicincome

inequality— lackof export diversification,

and

failedpolicyexperiments.However,

those countriesthathave

largelytamed

these traditionalproblems

arestillaffectedby

volatility,although

now

of amore

subtle financial origin, not unlike that recently affecting East Asia.These

financial factors are oftencompounded

by

leftoverweaknesses

resultingfrom

themismatch between

the dramatic increase in financial activity "required"by

the post-Brady era,and

theshortage ofinstitutionaland

human

capital infrastructure createdby

nearly adecade

ofpost-debt-crisisturmoiland

financial repression.While

some

ofthese financial factors areundoubtedly

apart ofthenew

globaleconomy

--inparticularthe greaterflexibility

and

options forcapitalas well as thehighly-leveraged1FirstDraftMarch29,2000.PreparedfortheWorldBank'sLCRFY00flagshipreport"DealingwithEconomicInsecurity

inLatinAmerica."

2MITandNBER.IthankAdamAshcraftforoutstanding researchassistance,and IndermitGill,WilliamMaloneyandLuis

nature of

many

ofthese investors—

a significantcomponent

oftheproblems

associated withthem

can be attributed to domesticweaknesses

present ineven

themost advanced

economies

of the region. It is theseweaknesses

that I attempt to identify here, as theymost

likelyrepresent the primary LatinAmerican

challenge in the nearfuture.With

this objective, the bulk ofthe evidence presented here corresponds to the recent experiences ofArgentina, Chile,and Mexico,

threeofthemost advanced economies

inthe region.Rather than attempting to characterize every possible

shock

and

amplificationmechanism,

this paperoffers a parsimonious account ofvolatility in countries thathave

already

tamed most

of the traditional sources ofmacroeconomic

instability in Latin America. It buildson

two

widelyobserved weaknesses: (i)weak

links with internationalfinancial markets,

and

(ii)underdeveloped

domestic financial markets.Once

interacting,these

two

ingredients not onlyexplain the observedvolatilitybut theyalsogenerate clearexternalities that require policy intervention. This

framework

thus provides a clear foundation for policy analysis.Most

other shocksand

deficiencies are leveraged-

even

made

possible-

by

thesetwo

factors.Moreover,

to the frustration of highlycompetent

policymakers,the

environment

becomes

intolerantofpolicy mistakes.II.

Diagnostic

and

Analysis

In thissectionIprovideaconceptual

framework,

hopefully flexibleenough

tobe

adapted to a broad set ofcircumstances, albeit preciseenough

to speculateon

policy issues.The

firstand

main

part ofthis sectionpresents theessenceoftheframework,

while thesecond

partdiscusses a

few

canonical shocksand

their impact within the outlinedenvironment.4 Irefer tothese parts as "thecore" (of the analysis)and

"the periphery," respectively.3SeeIPES(1995)foranexcellentandforcefulexposition

ofLatinAmerica'svolatilityproblem.

4Theessenceoftheconceptualframework

isanadaptationofthat inCaballeroand Krishnamurthy(1999, 2000). The

examplesandapplicationsaremostlyfromCaballero(1999a,b,c). Allofthesepapers can bedownloaded from http://web.mit.edu/caball/www.

11.1

The

Core

The

IngredientsEmerging

economies

are distinctly characterizedby

two

fundamental weaknesses: (i) aweak

link to international financial markets,and

(ii)underdeveloped

domestic financial markets.One

can think ofthesetwo

ingredients as the core, in the sense thateven

after addressingthetraditional imbalances theyremain

presentand

readytocauseand

leverage crises. Iprovidesome

evidenceforeach

ofthesekey

ingredientsbelow.A.

Weak

international financial links.These

are simply financial constraints, possibly time-varying, that limit the publicand

private internationalborrowing

(broadly understood) ofemerging

countries.Weak

links to international financial markets limitthe

smoothing

of shocks over timeand

are themselves a source of shocks, creating excessivevolatilityintherealeconomy.

The

evidence for this is substantial. Just to highlight afew dimensions

of this problem, consider:i) Quantities.

An

immediate

piece of evidence is that LatinAmerican

economies, unlikeOECDs,

typically exhibit pro-cyclical fiscal deficits.As

standardmacroeconomic

stabilizationarguments

indicate that these deficits ought to be counter-cyclical, this pattern hasbeen

interpreted as a seriously sub-optimal policy,and most

likely the result of the financial constraints facedby

thegovernments

themselves. Additional evidence is presentin theverylow

levelsof currentaccount deficitswhen

compared

to a neoclassicalbenchmark,

or the large swingsincapitalflowsthatbearlittlerelation-

atleastinterms ofmagnitude

-

tochanges

infundamentals.ii) Prices.

There

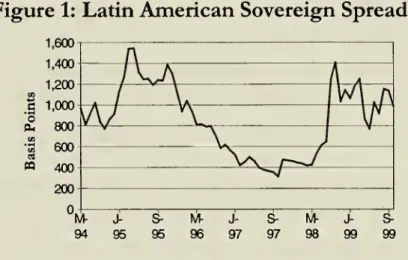

is alsoevidence offinancial constraints in the price data. Figure 1 illustrates the path of an index of sovereign spreads for LatinAmerica's

largesteconomies

over thesecond

half of the 90s.The

large surge in these spreads aroundtheMexican

and

Russian crises, starkly illustrates themassive

withdrawal ofmuch-needed

foreignsupportforLatinAmerican

assets.Figure

1:Latin

American

Sovereign

Spreads

1,600

Note:thetimeseriesisanaverage ofArgentina,Brazil,Mexico,andVenezuela.

iii) (Self-fulfilling?) Volatility

premium.

Moreover,

while less thanprime

corporateassets in the U.S. also suffered during the Asian

and

Russian crises, the rise in theirpremia

was

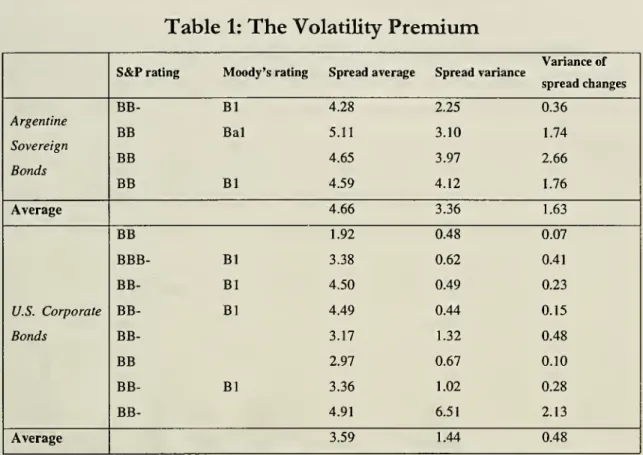

substantially smaller. This difference can also be appreciated over longer time intervals. Table 1, for example,compares

theperformance

of several Argentine sovereignbonds

with that ofseveral U.S. corporatebonds

of equivalentrating.The

tablereports the average spreads oftheseinstruments over U.S. Treasury instruments, as well as the variance of these spreadsand

that of theirchanges.The

evidenceillustrates that, relative toU.S. corporate bonds, LatinAmerican bonds pay

a higher spreadand

their returns are substantiallymore

volatile.

Moreover,

thespread-premium

is probably a result of this "excess volatility" that mostlycomes

from

episodeswhen

financial markets tighten foremerging

markets. LatinAmerican

bonds

look "illiquid"from

the point ofview

of spreads

and

volatility, despite the fact that theirvolume

is oftenmuch

largerthat thatofthe specificU.S. corporate

bonds

describedin thetable.7Table

1:The

Volatility

Premium

S&P

rating Moody'srating Spread average SpreadvarianceVarianceof spread changes BB- Bl 4.28 2.25 0.36 Argentine Sovereign Bonds

BB

BB

BB

Bal Bl 5.11 4.65 4.59 3.10 3.97 4.12 1.74 2.66 1.76 Average 4.66 3.36 1.63BB

1.92 0.48 0.07BBB-

Bl 3.38 0.62 0.41 BB- Bl 4.50 0.49 0.23 U.S. Corporate BB- Bl 4.49 0.44 0.15 Bonds BB- 3.17 1.32 0.48BB

2.97 0.67 0.10 BB- Bl 3.36 1.02 0.28 BB- 4.91 6.51 2.13 Average 3.59 1.44 0.48Notes: Spreadaveragemeansaverage overbondlifetime (or startingat earliestdateavailableinDatastream).ArgentineSovereign

Bonds:ARGENTINA-PARG/R93-23,ARGENTINA113/8%97-17,ARGENTINA 11%96-06,ARGENTINA83/8%93-03.

U.S.Corporate Bonds:FRUITOFTHE

LOOM

7%81-11,MAXUS ENERGYCORP.DEB81/2%89-08,SEACONTAINERS121/2%93-04(B),SEACONTAINERS12

%%

92-04(A),AKSTEELHOLDINGCORP.103/4%94-04,CLARKOILREFINING9 1/2%92-04,BETHLEHEMSTLCORP.DEB8.45%86-05,TRSP.MARIT1MAMEXICO91/4%93-03.

Source:BonddatafromDatastream.

B.

Underdeveloped domestic

financial markets.Turning

to thesecond

ingredient, thedevelopment

of domestic financial markets is instrumental not only in fostering investmentand

growth, but also in aggregating resources during distress.Underdeveloped

financial markets limit theprompt

reallocation of resources, creating wasteful contractions in those marketsmost

affectedby

shocks or lessplugged

into thefinancial system.

On

the otherhand, asfinancialdevelopment

rises so does leverage,and

with it the vulnerability of the financial system to shocks also increases.

Many

Latin7Theconclusionsmustbeinterpretedcautiously,since

American

economies

have

suffered at both ends: chronic financial repressionand

underdevelopment

and,when

moving

away

from

that, large collapse of thebanking

system.

Most

significantly, following Caballeroand Krishnamurthy

(1999, 2000), I will arguebelow

that it is this domesticunderdevelopment

that naturally creates externalities that justifymacroeconomic

policiesaimed

atimproving

the country's international liquiditymanagement.

Later

on

Idiscuss "shocks" tothedomestic financial sector,while hereI simply highlight thelow

level ofdevelopment

ofmost

LatinAmerican

financial markets.For

this,consider

two

basic featuresofthesemarkets:Figure

2:Latin

America's Level

Problem

(a)LatinAmerica

125

100

Argentin Brazil Chile Mexico

SM3 "ClaimsonPrivateSector DStockMarket

Capitalization

(c)Stockmarketcapitalizationand

turnoverratio

120

Australia Chile Portugal Norway U.S. StockMarket

Capitalization

8 Turnover Ratio

(b)Developed economies

Australia Chile Portugal Norway U.S.

8M3 ClaimsonPrivateSector StockMarket

Capitalization

(d)niiquidity

(coeff.regressionofabs.pricechangesontrade)

Australia Norway

i)

Low

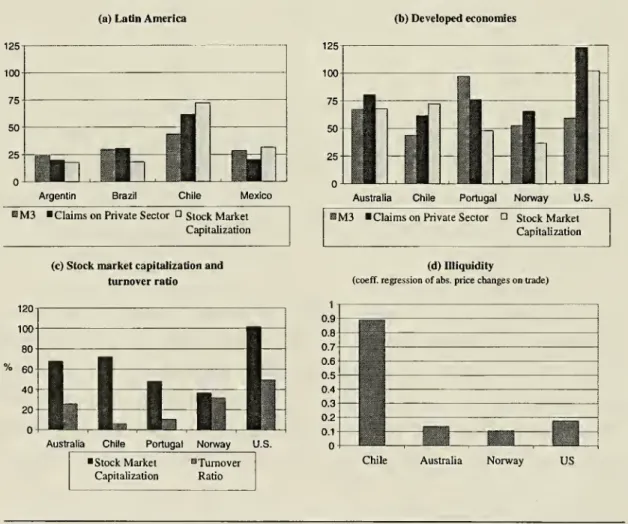

levels. Figure2

highlights LatinAmerica's

"level problem." Regardless ofhow

it is measured,and

despite significantimprovements

over the last decade, LatinAmerica's

financial marketsand

level of financial intermediation are sub-standard. In panels (a)and

(b) it is clear thatM3,

loans,and

stockmarket

capitalization, each relative to

GDP,

fare poorly with respect toOECD

economies.ii) Illiquidity.

Even

when

the standardmeasures

offinancial depth are atworld

class levels, there is always evidence of underdevelopment.The

dark bars in panel (c)confirm that in terms ofstock

market

capitalization values, Chile is an outlier intheregion

and

fares wellcompared

tomore

advanced

economies.The

light bars, oon

the otherhand, reflectthatChile has avery substandard turnoverratio. Panel (d)reports theresultsof runningasimpleregression ofthe absolutevalue ofdaily pricechanges

(ameasure

of volatility)on

thechange

in the fraction of total capitalization traded. Literally interpreted, it revealsthaton

average an increase in thevolume

traded, in terms oftotal capitalization value, is associated with an increase inprice volatility thatis aboutten timeslarger in Chile than in countries withpresumably

betterdeveloped

financial markets.A

SimpleModel

With

the help ofafew

diagrams, in this section Ioutline a structure to think through themacroeconomic

consequences

-

and

later on, the policy implications-

ofthetwo

core-ingredientshighlightedabove.It is not too farfetched to think about an

emerging economy's

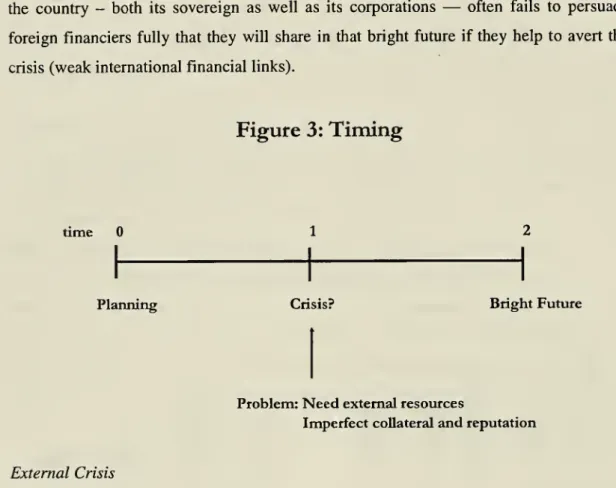

timeline in the terms described in Figure 3.Date

corresponds to"normal"

times,when

investment, planning8Whileexcessivechurn canbewasteful,

itishighly unlikelythatChile'sdepressedlevelsareenoughtosupportasolid

infrastructureof market makersable toprovide optimallevelsof immediacy andliquidity.Moreover,onecould arguethat

thewastes associated withnormal churnare acostworthpayingtoreducethe extentofsystemicliquiditycriseswhenthese

arise.Thisisathemeworthresearching furtherinthecontextof emerging economies.

and

prevention are all very relevant.A

significant part of this planning has todo

with anticipatingand

preventing acrisisin theperhaps not too distantfutureat date 1.Date

2

represents the future, alwaysbrighterthan the present, buta significant obstacle is thatthe country

-

both its sovereign as well as its corporations—

often fails to persuade foreign financiers fully that they will share in thatbright future ifthey help to avert thecrisis

(weak

international financial links).Figure

3:Timing

time

Planning Crisis? BrightFuture

Problem:

Need

external resourcesImperfectcollateral

and

reputationExternal Crisis

Figure

4

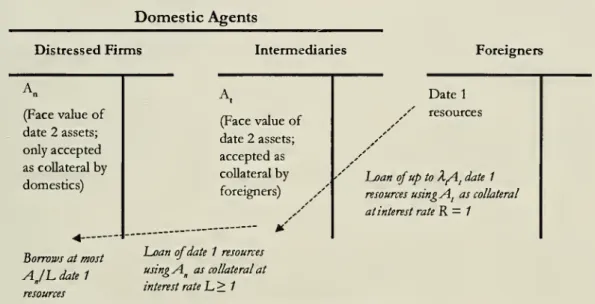

describes the elements creating a crisis driven entirelyby

insufficient external resources, butwith a perfectly functioningdomestic financialsystem

-

thatis,when

only the first ingredient is present.We

can think ofa crisis as a timewhen,

(a) a significantfraction of firms or

economic

agents are inneed

of financing to either repay debt orimplement

new

investmentsneeded

to save high return projects,and

(b)on

net, theeconomy

as awhole

needs substantial externalresources butdoes

nothave

enough

assetsand

commitment

to obtain them. Loosely, I refer to these assetsand

commitment

as"collateral,"

which

needsnotbe

interpretedliterally as pledged assetsbutasthe resourcesthat are likely to

be recouped

by

a lender. In order tomake

things as stark as possible,imagine thatdistressedfirms

have no

assetsof value to foreigners, butthatthe high date2

returnon

their investment if successfully maintained,A

n, is fully pledgeable to otherdomestic agents.

To

be concrete, think ofA

n as the value of a building (nontradeable)delivered atdate 2,

and assume

thatabsent a crisis the discount offutureflows is simply zero, the internationaldiscountrate.The mass

ofthese projectsisone.Figure

4:

Equilibrium

in

Domestic

Financial

Markets

Domestic

Agents

DistressedFirms Intermediaries Foreigners

(Face valueof date2assets; onlyaccepted as collateralby domestics) (Face valueof date2assets; acceptedas collateralby foreigners) Datel resources Loanofupto

^

lA

l date1 resourcesusingA

: ascollateral atinterestrateR

=

/ BorrowsatmostAJL

date 1 resourcesLoanofdate1 resources

usingA. ascollateralat

interestrate

L

>

1•Distressedfirmshaveprofitableprojectsbutneeddate1 resources

•Foreignersrequirecollateral

when

lendingdate 1 resourcesatthe internationalinterest rate•Onlydomesticintermediaries

own

internationally-acceptedcollateralOther domestic firms

and

investors (orforeign specialists)have

assets,A

t , that are"good

collateral" toforeigners.

For

example, U.S. T-bills, the presentvalue of exportsas well as other domestic assets —liketelecoms—

thatmay

bedeemed more

transparentand

trustable

by

foreign investors.As

is highly unlikely that foreignerswould

be willing to providefinancing equivalenttothe full valueoftheseassets-due

toa sovereign problem,for

example—

assume

thatone

unit ofA

t only secures a loan of A< date 1 resources.Much

of the policy discussion lateron

has todo

with increasing the value of thisparameter.

L

A.

Figure

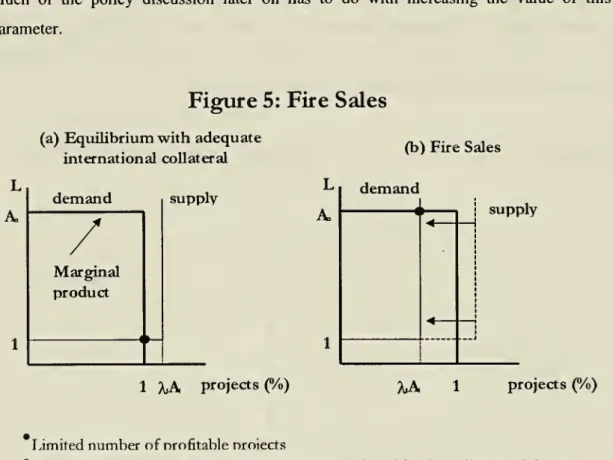

5:

Fire Sales

(a)

Equilibrium

with adequate

international collateral

demand

Marginal

product

supply

1XA

projects(%)

(b) FireSalesL

demand

A,supply

kA

1 projects(%

Limited

number

ofprofitablenroiects"Scarcityofinternationalcollaterallimitsthetransfer

of

fundstodistressed firms•

A

decline inthequality ofacountry'sinternationalcollateral can cause a firesaleDomestic

financialmarkets are essentially the placewhere up

toXtA

tdatel resources aremade

availableto the distressedfirms,who

have

date2

assetsA

nto pledgein exchange.When

theeconomy's

pledgeable resources are greater than the needs ofdistressed firms, arbitrage keeps the internal cost of fundsL

equal to the international interest rate (normalizedtoone

here), all distressedfirms are abletoborrow

funds,and

onlya fraction ofdomesticcollateralA

nneeds tobe pledged. Thisis thecaseinpanel(a) of Figure5. Inthis simple example,

where

all projectshave

thesame

highreturn, the domesticdemand

for international liquidity

by

distressedfirmsis flatup

tothe pointwhere

all projects arefully refinanced.

The

supply,on

the other hand, is flat at the international interest rate1'Thus,

inaddition tobindingmicroeconomicincentiveproblems,theremaybesovereignriskassociated tomanyofthese

assets,especially intheeventofcrises.Thelatteraffectsforeigners'valuationoftheseassetsevenwhenthey acquire the

until international collateral A^At runs out,

where

itbecomes

vertical.12When

the aggregate needs of distressed firms are greater than pledgeable resources, competitionamong

distressedfirmstransfersalloftheirprivate surplus (returnabove

the internationalinterest rate) to the domestic suppliers ofinternationalliquidity. Panel (b) illustrates this fire sale ofdomestic assets.

The

fraction ofprojects financed isAtA

t<1,and

the discountof domesticcollateral

jumps

from

one, the internationallevel, toL

=

A

n>1

.

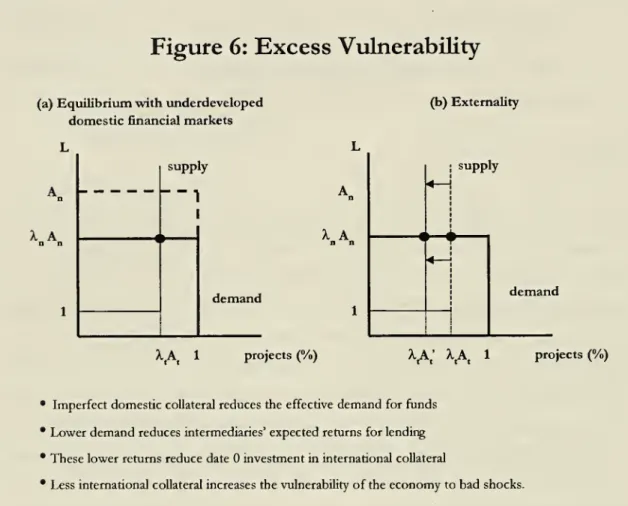

Externality

and

PolicyProblems

Under-provision.

While

the scenario describedabove

can indeed represent a greatsource ofuncertaintyand

volatility for a country, it is not clear that there is a role for policy,aside

from

structural ones (see section III). Since domestic providers of international liquidityare transferred allofthe surplusduring crises,they are given therightincentivesto supply this liquidity. It is here

where

thesecond

ingredienthighlightedabove

plays acentral role.

When

domestic financial markets are imperfect in the sense that distressed firms without direct access to international financial marketsdo

nothave

themeans

to fullypledge theirreturns to otherdomestics orinformed

investors, the ex-ante incentiveto

hoard

and

supply international liquidity isweakened.

Market-making

is not a great businessin amarket

withconstraineddemands.

Imperfectdomestic financial markets are capturedhereby

the assumptionthatonly a fraction \n<\ ofa distressed firm's value canbe

pledged.Panel(a) in Figure

6

illustratesthe scenariojustdescribed.Given

thedate allocations, a decline in A„reduces the effectivedemand

(payment

capacity) ofinternational liquidity.While

the marginal product curveremainsunchanged

(dashed line), the effectivedemand

curve (solid line) shiftsdown

as themaximum

payment

per unit of investment is onlyprivatecontrolrights

12These abrupt changesinslopesareonlymeantto captureas clearly aspossiblethefactthatthereareregionswheremost

firmscansatisfytheirfinancialneedsandthe costofcreditisdeterminedbyinternationalconditions,andotherswhereits

thedomesticavailabilityofinternational assets thatdeterminessuchcost.

A„An.

As

long as pledgeable assets are greater than the opportunity cost of funds (the international interestrate),however,

domestic providers willmake

theseloans.Figure

6:

Excess

Vulnerability

(a)Equilibrium with underdeveloped domesticfinancialmarkets

(b)Externality X

A

supply " -1demand

XA

i supply 14—

I 1 1 1 1 1 • 1 1T

demand

|lA

t 1 projects(%) A.A,' A. (A

t 1 projects(%)• Imperfectdomesticcollateralreduces theeffectivedemandforfunds •Lowerdemandreducesintermediaries'expectedreturnsforlending

•Theselowerreturnsreducedate investmentin international collateral

•Lessinternational collateralincreasesthevulnerabilityoftheeconomytobadshocks.

But

domestic availability of international collateral will notremain unchanged.

In this environment, frictions in themarket

for domestic assets distort the private returns of holding domesticand

international collateral.The

ex-ante equilibrium response to such distortion atdate is capturedinpanel (b), with aninward

shiftin the ex-ante supply of international liquidity/collateral. Since domestic financial constraints limit the returns receivedby

international liquidity providersbelow

the full return ofdistressed projects,the incentive to provide such liquidity declines. In so doing, the

economy

experiencesmore

frequentfire salesand

more

severe distress inthe event of an international squeezeon

the country.The economy

is in theend

made

too vulnerable to external shocks asNotethatadeclinein

L

does notnecessarilyimplythatthedomesticinterest ratefallsrelative tothecase withbetterdeveloped domesticfinancialmarkets(forgiveninternationalliquidity).Itmay

implyinsteadthata largershareofthedomestic "loan"becomesuncolletaralized.

domestic investors

do

notvalueinternational liquidity enough, creatingless internationalcollateral thanissociallyoptimal.

Distorted External Maturity Structure

and

Currency Denomination.

A

similar situation arises with respect to short versus long term debt,and

with respect to the currencydenomination

of external debt.Long

term

debt is like short-term debt plus rollover insurance.When

domestic financial marketsareunderdeveloped,thereis lessincentivetobuy

the insurance thanis socially optimal since the holders ofthat insurance thatdo

not experience distressand

financial needs at date 1do

not receive the full social return of their guaranteed debt-rollover. Similarly,denominating

external debt in domestic currencyamounts

to adding ahedge

against depreciations.For

the reasonsexposed

above,this

hedge

willbe

undervaluedby

thedomestic private sector aswell. Iwillreturntothese issues inthepolicysection.

To

summarize,

Ihave

portrayed the core ofanadvanced emerging

economy

in terms oftwo

basic features. First, it frequently finds itself near the limit of its capacity for international financing (stocks or flows). In such a position, intertemporalsmoothing

islimited

and changes

inexternal or domestic conditionscan

have

potentiallylarge effectson

domestic activity. Second, domestic transfers of value are limitedby underdeveloped

financial markets

and

the institutions that supportthem

(see policy section).As

a result,the incentivetoreducethe vulnerability brought about

by

the firstfeature is undervaluedby

the private sector. Thus, the decentralized equilibrium is excessively volatile. In the next section I discuss shocks within thisframework

and

in section III I discuss appropriate policy responses to deal with the excess volatilityproblems

given the structure(theA.s)as well asmeasures

toimprove

thestructure.11.2

Shocks and

thePeriphery

Continuing with a minimalist approach, I argue here that

once

in theenvironment

described above, the bulk of the volatility observed in

advanced

LatinAmerican

economies

canbe

described usingjusttwo

canonical external shocks.Sometimes

itis thedirecteffect oftheseshocks thatcreates volatility, while in others it is simply the fearof

them

thatleads the authorities to createprecautionary recessions, or the private sectortospeculate

on

theirpotential arrival.Canonical

Shocks

Externalfinancial shocks.

The

most

directshock

conducive to a fire saleand

crisis isindeed a

sudden

loss in the international appeal ofacountry's assets. This can bedue

tocountry-specific factors as well as to

changes

and

shocks inthesegments

ofinternational financial marketsrelevant for the country.The

turmoil afterthe Russian crisisinOctober

1998, as well as the debt crises that followed U.S. interest tightening during the early 1980s, are

two

prototypicalexamples

ofthelatter.A

shock

ofthis nature canbe

capturedin themodel

as a deterioration inthe quality of anemerging

economy's

international collateral,A*, that shiftsthe supply curve tothe left as the country's capacitytoborrow

abroadisreduced.As

the spreadbetween

the domesticand

international interest rates rises, there is a fire sale of domestic assets because the domestic opportunity cost of holding these assets is highwhen

credit is scarce.14The

counterpartofthefire saleisthe limitedreinvestment

and

costlyterminationofdistressed high netpresentvalueprojects.14Foreigners or non-specialistsareunabletocapture these high returnsbecause

attimesofcrisestheyonlyholdand

arbitrageclaimsbackedbyinternational collateral. Whiletheirarbitrageduringnormaltimeskeepsthe international spread

atzero,itisimmaterialwhenthe internationalcollateralconstraint binds. Thatis,theinterest parityconditionshirtsuntil

domesticequilibrium, rather thaninternational arbitrage, holds.

Figure

7:Excess

Sensitivity

and

Chile

(a)Growthand copperprice

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1998 1997 1998 1999

c

09

s

(b)Present valueeffectofternsof tradeshocks

"flcj

1987 1988 1989 II

|—yowtHd^fccmrrraH

—

PV«n»jSources:growthfromIFS,copperprices(LondonMetalExchange)fromDatastream.

Terms

oftrade shocks.Shocks need

notcome

directlyfrom

external financial factors to reflecttheweakness

offinancial links. Panel (a) in Figure 7 plots the paths ofthe spot priceof copperfrom

theLondon

MetalExchange

and

Chile's quarterlyGDP

growth.The

resemblanceis stark, with the only important exceptionbeingthe

1990 growth

slowdown

and

its recovery episodewhich had

a purely domestic origin. Panel (b)documents

the excessive sensitivity of Chile'sGDP

response to copper pricesby

plotting the annuity value ofthe expected presentvalue impact ofthe declinein copper prices, as a share ofGDP.

15 It is apparentfrom

this figure (the different scales in the axes, in particular) thatfluctuations in

GDP

are an order ofmagnitude

larger than asmoothing

model

would

dictate 16

15Thepresent valueeffectiscomputedassuming anAR(4)processforthespotpriceofcopper,aconstantgrowthratefor

copper production (7%) anda fixeddiscountrate(7.5%).

Thepriceofcopperhas trendsandcyclesatdifferent frequencies,someofwhicharepersistent (seeMarshallandSilva

1998).Butthereseemstobenodoubtthatthesharp declineinthe priceof copperduring the currentcrisiswasmosdythe

resultofatransitorydemandshock brought aboutbytheAsiancrisis.Asthelattereconomies havebegunrecovering,so

has the priceofcopper.Iwouldarguethatconditionalonthe informationthatthecurrentshockwasa transitorydemand

shock, the univariateprocess usedto estimate the present valueimpactofthe decline in the priceof copperin figure3,

overestimates the extentofthisdecline.Thelowerdeclineinfuturepricesisconsistentwiththisview.Thevarianceofthe

spot priceis 6times the varianceof 15-months-ahead future prices. Moreover,theexpectationscomputed fromthe

AR

process track reasonably well the expectationsimplicit infuture marketsbutatthevery end ofthe period,whenliquidity

premiaconsiderationsmayhavecomeintoplay.

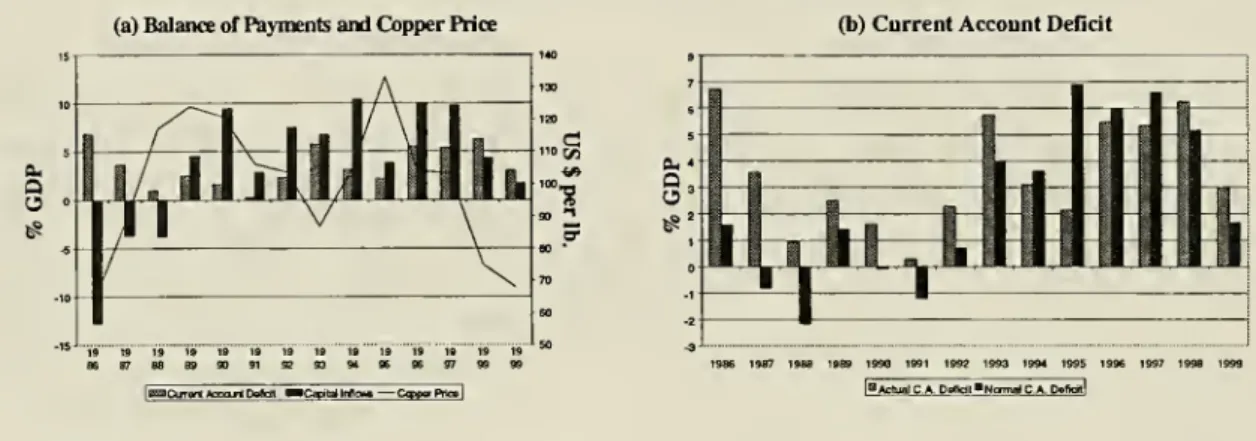

Figure

8:Copper

Prices

and

Chile's

Current

Account

(a)Balance ofPaymentsandCopperPrice (b)CurrentAccountDeficit

ntDsftdl MCiT-lailrftai*—C<QpaPnce]

|HAcmdC.ADritolNtrmalC.A. Dnfidtl

Source:INEandBancoCentraldeChile.

The

view

portrayed in thispaper identifiesthefundamentalproblem

asone

ofweak

linksto international financial markets. Panel (a) of Figure 8 reinforces this conclusion,

illustrating the positive correlation

between

the current account deficitand

the price of copper, opposite towhat one

would

predictfrom

standardsmoothing

arguments.The

"tequila"crisisof

1995

appears tobe

theexceptionthatprovesthe rule as thehigh copper pricegave

the Chileaneconomy

enough

"liquidity" to ride through the crisisand

experiencefast domestic

growth

despitethe large international credit crunch experienced1n

by emerging

economies. Thisisconfirmed

inpanel (b),which

demonstrates that Chile used a large fraction of the "liquidity" givenby

the high price of copper to offset the decline in capital inflows as the current account deficit atnormal

prices reached itshighest level duringthatyear.

Most

importantly, exactly the oppositeoccurred during the1998-99

crisisas the price ofcopper

plummeted

(erasingChile's liquidity) at the precise timethatinternational financial marketstightened.1817Capitalflowswerehighmatchingthehigh

copperprice,butthe currentaccountwasnot.Theotherexceptionreflectsa

domesticallyinducedrecession,asitresultedfromthemonetarytighteningimplementedatthebeginningofthenew

governmenttooffsettheinflationarypressuresoftheprecedingpoliticalcycle.Capital flowsremainedhighbutultimately

ledtotheaccumulation ofinternational reserves rather than financingacurrentaccountdeficit. 18

Notethattermsoftradewerealsobadin1993 andthat,consistently,growth sloweddownthatyearaswell(see figure1).

However,internationalfinancialmarketswere buoyantatthetime sothisdeclinedidnotcometogetherwith a severecredit

crunch.

Inordertoplacethis scenariointhe context ofthe

model

above,assume

thatinternational collateral is constituted only oftradablegoods

while domestic collateral represents non-tradedgoods.An

adverse terms oftradeshock

is simplyadeclineinthe value oftraded goods,A

t ,which

reduces the country'sborrowing

capacity and shifts the supply curvetothe left in a

manner

similar to the financial shocks above.A

sufficiently large orsufficiently long

sequence

ofterms of trade shocks can significantly reduce a country's internationalliquidity, causing afire saleand

correspondingreal decline.Needless to say,the extentto

which

this is likely tohappen depends

criticallyon

the tightness ofexternal financialmarkets.A

pprehension

In isolation, these canonical shocks are not always large

enough

tojustify the observed aggregate volatility createdby

a crisis,and

at times crises occureven

without their apparent presence.These

features are not in contradiction to the basic premise, for both theirpresence as well as ahigh likelihood ofthem becoming

a factor in the near future typicallysuffice to triggerpublicand

privateresponses withrecessionaryconsequences.Monetary

Policy "Shocks".The

case of Chile during its1998

recessionstarklyillustratesa precautionary recession.

The

mandate

of the CentralBank

of Chile hastwo

basiccomponents:

tomeet

a declining inflation target,and

to prevent the current account deficit (at"normal"

terms of trade)from

going toomuch

beyond

four percent-

it obviouslybecomes more

sensitivetoward

the latterwhen

external financial conditionstighten.

The

lattercomponent

ofthemandate

is clearly an institutional reflection ofthe country'sconcern withexternalcrises.Under

thismandate, the1998

scenariorepresented the CentralBanks's

"worst nightmare."The

sharp decline in terms oftrade putpressure"Theinternationaleconomicsliteraturehaslong recognizedtheimportance ofinternational collateralanditsrelationwith

acountry's tradeablesector. SeeSimonson(1985). Formal models ofsovereigndebt renegotiationare builtaroundthe

questionofwhatinternationallenderscanthreatensovereign countries withintheeventofdefault. Inthis literature,

international collateralistypicallytaken tobesomefractionofexports. SeeEaton andGersovitz (1981) orBulowand Rogoff(1989). Cash revenuesfromexportscanbeseizedbefore theymakeitbackintothe country. Thisfeaturewasused byMexicoduring the94-95crisiswhenitsoilrevenuesweremadepartofthecollateralbackingtheliquiditypackageit

received.

20Ofcourse, theseresponsesmayindeed preventlarger crises inthenearfuture.

21There

isanextensivedebateinChileon whetherthiswasindeed the Centra]Bank'smandateorwhether itwassimplyan

inadequate interpretationofit.Thisdistinctionisirrelevant forthepointmadehere.

on

the peso,and hence

on

inflation,and

directlyworsened

the current account via itsincome

effect. All of thishappened

in themiddle

of a very difficult external financial markets scenario. Itwas

inthemandate

-

optimal or not-

todo what

the CentralBank

did;a sharptighteningof

monetary

policywas

theoutcome.

SpeculativeAttacks

and

CredibilityProblems.At

times, as indeedwas

thecase of Chile in the episode described above, the private sector also anticipates the potential external bottleneck. In doing so, it typically runs against the currencyand

domestic assets, exacerbatingtheirfire saleand

the centralbank's precautionarytightening. Itis important tonote, nonetheless, thatabsentthepotential external constraint these attackshave

avery diminishedchance

of succeeding,and

that a fragile domestic financialsystem

makes

these attacks

more

likelyand

more

costly (seebelow).Conversely, the

much-needed

adjustment of the realexchange

rate during times of external crises-an

adjustment that is mostly requiredby

the limited availability of external financing— issometimes

hampered by

the lack of credibility of domesticmonetary

policy.The

case ofMexico

during the Russian crisismakes

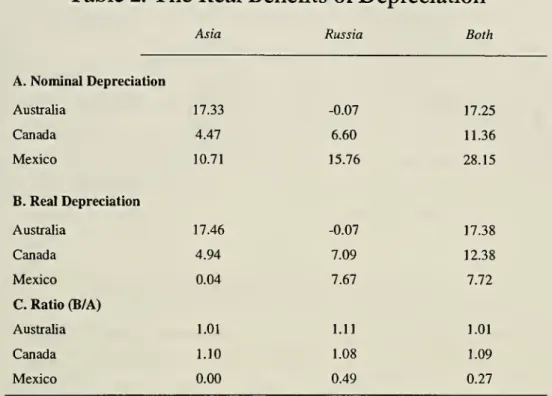

the point. Table2

compares

the experience ofMexico

to that ofmore

advanced economies

with flexibleexchange

rate systems: Australiaand Canada.

It is apparentfrom

the table that while allthese countries experienced large

and comparable nominal

depreciations during thisperiod,

Mexico

had

much

less toshow

for it in terms of a real-devaluation as inflation eroded a large part of thenominal

depreciation. Rather mechanically,one

can interpret thisin terms ofavery highpass-through.My

view

is thattheproblem

resultsfrom

alack ofa crediblemonetary

anchor thatdrives both theexchange

rateand

domestic inflationup

atthe firstsightoftrouble.22This claimdoesnotdeny

thatthereare timeswhenattacksarebasedpurelyonthe anticipationofamonetarypolicythat

isinconsistentwith theexistingnominal exchangerateratherthan the anticipationofasharp shortageofrealexternal

resources.

Table

2:The

Real

Benefits

of

Depreciation

Asia Russia Both

A.NominalDepreciation Australia 17.33 Canada 4.47 Mexico 10.71 -0.07 17.25 6.60 11.36 15.76 28.15 B.RealDepreciation Australia 17.46 -0.07 17.38 Canada 4.94 7.09 12.38 Mexico 0.04 7.67 7.72 C. Ratio(B/A) Australia 1.01 1.11 1.01 Canada 1.10 1.08 1.09 Mexico 0.00 0.49 0.27

Notes:January1997isthebase yearineachpanel. Nominalexchangeratesarerelative to theUnitedStates.

Real exchangeratesare constructed usingtheConsumerPriceIndexandarerelative to theUnitedStates. Asia

includes thedepreciationfrom97:3to98:2 whileRussiaincludesdepreciationfrom98:2to98:4. Dataarefrom

the IFS.

Domestic

FinancialSystem

Shocks

and

Amplification: CreditCrunches

and

Runs.The

description oflevels inFigure 2hidesimportant

dynamic and

cyclicalaspectsoffinancial markets,and

ofbanks

in particular.These

play important roles as amplificationand

causes of external crises. Panel (a) of Figure 9 illustrates the severe

Mexican

credit crunch that followed the "tequila" crisis. Loans,and

in particularnew

loans,imploded

early

on

during the crisis, especially as the currencywent

into free falland dragged

the alreadyweak

balance sheets ofMexican

banks

with it.There

isno

doubt that the severe creditcrunch significantlyleveraged the94-95

crisisand

that the collapse in thebanking

system

willimpose

costson

theeconomy

and

the public accounts formany

years tocome.

Figure

9:Credit

Crunches

(a)Memo)

(b)Argentina

9494M«9G9GS6SSSGgESGSS97S797S79SSBSB9e9ese

rxposts Loans Deposits Loans

The

Argentine case during thesame

episode startedfrom

the other side of the banks' balance sheets. Panel (b)ofFigure 9illustrates thepath ofdepositsand

loans,indicating that itwas

notthe valueoftheloans thatimploded

—

perhaps because the exchange rate did not collapse—

but that depositors ran for their deposits in orderto convertthem

into dollars asthey expected that the tight external conditions

would

make

the convertibility system unsustainable.The

basicmodel

is easilyextendedtoinclude abanking

sectorthatreplaces the domestic credit chains discussed above.For

example, in order to capture a Mexican-style creditcrunch, let

banks

make

loansto firmsfunded

at dateby

issuing debt to foreigners.At

date 1, domestic holders ofinternational assets

mortgage

them

and

deposit the proceedsin the banking systemthatinturn intermediates

new

loans todistressed firms.Banks

are subjectto capitaladequacy

standards such that the ratio ofthemarket

valueofcapital toloans

must be

at least a.When

banks

are unconstrained, theeconomy

is equivalent to that describedabove

with perfect domestic financial marketsand

weak

financial links.Once

adequacy

standards bind,however,

the supply curve for internal fundsbecomes

backward

bending asbank

capital is erodedby

higher interest rates that in turnlower

asset prices.

Panel (a) of Figure 10 illustrates that this fire sale of assets

may

sharply reduce thebanking

sector'slendingcapacity,creatingacreditcrunch. Frictionsinthebanking

sectorare actually

more

serious than those described inundeveloped

financial markets above. Constrainedbanks

become

a financial bottleneck as excess domestic resources are not properly channeled to distressed firms, wasting otherwisegood

international collateral.While

the contraction in loan supply causesthe increase in interest rates, the collapse inasset prices amplifies the impact ofthe crisis

by deepening

the credit crunch causedby

distressedbanks' balance sheets. Panel (b) demonstrates thatthe feedback

between

asset pricesand

feasible intermediation can easily bring about the possibility of multipleequilibria.

Figure

10:

Bank

Capital

Crunches

(a)Equilibrium withbinding

leveragestandards

supply

demand

(b)Multipleequilibriawithbinding

leverage standards .supply

\\

1 projects(%)demand

1 X.A, projects(%)

Banks must

hold sufficient capital againstdate 1 loans todistressed firms*Higherinterestratesreduce thevalueof date loans,increasingmarketleverage * Bindingleveragestandardsrequirebanks toreduce date

1 lendingasinterest rates

Further Amplification

Mechanisms:

Crowding

outand Labor

Market

RigiditiesTraditional sources of

macroeconomic

problems

become more

troublesome in the financiallyfragileenvironment

thataffects LatinAmerican

economies.Crowding

outby

the government.When

financingfrom

foreigners evaporates, LatinAmerican

governments

frequently turn to domestic markets for financing,crowding

out private sectorinvestment. Thisis costly, sinceone

ofthemain

features offinancial crisesis that funds lose their fungibility

-

it isno

longerirrelevantwhere

thegovernment

getsits funding from.

Moreover,

it is thegovernment

thatnormally has themost

opportunity to access international financial markets. Thus, thegovernment

should shift its financingaway

from

domestic markets.The

Argentine case during the "tequila crisis" illustratesthe lack ofsuch adjustment. Panel (a) in Figure 1 1

shows

that during that episode therewas

a sharp increasein the shareofloansby

domesticbanks

going to the government.The

slow

recovery ofloans to the private sector relative todeposits describedabove

canbe

partlyattributed to this shift.Figure

11:Crowding

Out

(a) ArgentineNetPublicBorrowing fromDomesticBanks

—~Xp Ju OcJa Ap Ju 3c Ja Xp Ju OcJa Ap Ju OcJa 94 94 94 94 95 95 95 95 96 96 96 96 97 97 97 97 SB

Ap Ju OcJa Sp 98 98 9S 99 99

(b)Chilean Costs ofBorrowing

"*

JuJuSTs*6c No D« JaSM Ap'My'JiiJu Mi S«Oc'No'D*Ja'Pa ~M ApM' Ju

97979797979797989898989898989898989898999999999999

—Interna](loomrateInUF) Abroad(prime krana rata *»praad) Abroad(prime loonorain » jgfaad *rjgvj

This

mechanism

shouldbe

distinguishedfrom

thatwhen

it is the sovereign itselfthat isperceived as the source of the problem.

Whether

such perception is justified or not is23DuringtherecentcrisistheArgentinegovernmentresorted todomestic

financingagain; thistimebysellingbondstothe

pension fundsratherthanby borrowing fromthebankingsystem.

more

or less analogous to the issues behind the private sector's 7^ (that in turnmay

be

partly

due

toproblems

ofthe sovereign). In such a case, tightening fiscal accountsmay

be an unavoidable responseratherthanone

ofsmoothing

acrossdomestic margins.Crowding

outby

largefirms-

the cost of sharp interest rate reductions.As

external financing tightens for large firms, they too turn to domestic markets as preferred customers, facilitating the "flight-to-quality"demand

by

domestic financiers.The

socialcost of this strategy is that small firms generally

do

nothave

access to internationalfinancial markets, regardless of price.

To make

matters worse, this not onlyhappens

duringthe crisis butit

may

also extend tothe recovery phase.Some

evidence ofthis canbe found

during the recent Chilean recession.As

the perception that the worst of thecrisis

had

passedand

that the contractionwas more

severe than expectedbegan

to emerge, interestrateswere lowered

sharply, somuch

so that largefirmsmay

have found

it advantageous to turn to domestic financial markets to obtain financing

which

was

stilldifficult abroad. Panel (b) in Figure 11 illustrates approximate

measures

of the cost of international versus domesticborrowing

for aprime

Chilean firm.The

line inbetween

represents the cost of

borrowing

in dollars. It is apparent that while before the crisisborrowing

abroadwas

probably cheaper for these firms (especially given the realappreciationofthe peso), theoppositeholdsafterthecrisis.

Labor

rigiditiesand

inflexibility. Lastly,exchange

rateand

real rigiditiesareonce

again amore

serious source of concern in anenvironment

oflimited financial resources.Absent

the latter constraint

—

and

asidefrom

medium

term levelproblems

—

short-term lack of adjustment in prices shouldhave

limited impacton

long term investmentsand

projects. Present these,on

the other hand, short-termproblems

also affect these long-term decisions.24ThefigurecomparestheU.S.primerate,plus ameasureoftheinternationalspreadonChilean corporatedebtandtwo differentmeasuresofthe peso'srealdevaluation.

25Withtime,ifthesituation persists, localbankswillprobablyborrowabroadtolend tothesmallfirms.Butintheshort

run,given uncertaintyandthe conservativeattitudeofbanks,thismechanismislimited.Infact,onemaythinkofthe

crowding outmechanismin reverse:itisthe sharp increaseinthe banks' appetitefor quality thatlowers the equilibriumrate

andexacerbates the rationingmechanism.

Argentina is the regional prototype here, with its strict convertibility

law and European

style labor markets.

While

the credit crunch experiencedby

the Argentineeconomy

during

1995

could probably nothave

been

avertedby

amore

flexible realwage,

it isprobably true that in the still unraveling recession such rigidity

enhanced

the crisisby

generating a "collateral squeeze," that is a decline in the appeal of the firm's outlook

from

the point ofview

of the banks.26Firms

are severelysqueezed

from

two

complementary

ends:financialand

labormarkets.Moreover,

the relative rigidity ofwages

in Argentina during crises underestimates the extent oftherelative rigidity ofthe Argentine system.On

one

hand, countries withmore

flexible

exchange

rate systemsmay

choose

not to utilize this flexibility asmuch

in the midstofacrisis,when

controlled devaluationsareriskytoplaywith.On

the otherhand,and

more

significantly, the lack ofrealexchange

rate adjustment todaycomes

together with a lack of adjustment in the near future as well.The

perceived present value of overvaluations relative to crisis-overvaluations is likely to be higher in the Argentine system thaninmore

flexibleones.III.

Policy

Recommendations

The

goal ofthe organizingframework

was

to highlightand

understand the nature ofthe policyproblem

createdby what

I perceive as the fundamental sources ofmodern

LatinAmerica's

volatility. LatinAmerican

economies, includingthemost advanced

ones, lack alongtwo

central dimensions: links withinternational financialmarketsand

development

of domesticfinancial markets.

As

most

primitiveforms

ofmacroeconomic

volatilityhave

been

tamed by deep

reforms, it isthesetwo

ingredients, either directly orby

leveraging a variety of standard shocks, thatprobably account formuch

offluctuationsand

crises inmodern

LatinAmerica.

While

conventional advice for conventional maladies remains,26Ofcourse,onecould arguethatwith

realwageflexibility,particularlythroughexchangerateflexibility,therunon

depositsandtheensuingcreditcrunchwouldhavebeen avoidedaltogether.

27SeeHausmannet

al.(1999)forpreliminarybutsuggestiveevidenceondevaluation "refrainment."

28Thisconcept

isdifficulttomeasure, althoughsomeinformation canbeobtainedfrompeso-dollar spreads, stock markets,

andrealactivity.InCaballero (1999a)Ireferredtothisphenomenonas"claustrophobia"andreportedevidenceonitscosts

andonhowitchangesthe interpretationofmovementsininterest rates.

focusing

on

thesetwo

primitiveand

ingrained features offers a clearand

potentially rewardingpolicytarget.With

this target in mind, Ihave

arranged themain

policy discussion intotwo

groups:macroeconomic and

contingent (secondbest),on one

side,and

structural (first best),on

the other. In principle, the former takes the core deficiencies as given

and

points atpolicies

aimed

at reducing volatility within that environment.The

latter,on

the other hand, is aboutchanging

the core environment, amore

long-term goal. In practice, thisdistinction is less clear since volatility itself is probably an important factor behind the pervasiveness ofthe coreingredients.

What

followscombines

a list of policy suggestionsaimed

at ameliorating theproblems

discussed above, as well as a series of caveats

on

conventional advice raisedby

the perspectiveadoptedinthispaper.Macroeconomic

and

ContingentPoliciesTaking

the structure as given, there are essentiallytwo

policy problems: preventionand

crisis

management.

As

discussed above,underdeveloped

domestic financial markets typically lead to a situation where, ex-ante, international liquidity provision isundervalued. Thus, the goal of

macroeconomic

policy is to reallocate international liquidity useand

availabilityfrom

booms

to crises.During

the latter, the goal is toreallocate it to those

economic

agents thatneed

it the most, but thismust be done

with care not to affect significantlyand

perversely ex-ante incentives to hoardand

create international liquidity. Ideally, these policies shouldbe

made

contingent in order to reduce speculative behaviordue

to policy uncertainty.Moreover,

to the extent that it is feasible, a significantcomponent

of the aggregate risk associated with external shocks shouldbe

insuredaway

(seebelow).Macroeconomic

PolicyMonetary

Policy.The

quintessentialmonetary

policy to deal with this internationalliquidity

management

problem, is a sterilized intervention-

essentially, the centralbank

sells public

bonds

for international reserves-

during the capital flowsboom.

The

counterpart ought to be the selling

back

of these reserves during external crises. Experienceand

theory suggestthatthe firsthalfofthis policy, thesterilizedintervention,is hard

and

expensive toimplement

forprolonged

periods,and

itmay

even

backfire as the private sector reacts perversely to the quasi-fiscal deficit, appreciation,and

reserves accumulation at the central bank. Thus, this is probably not an instrument that canbe

usedfor

medium

term

prevention.Banks

inMonetary

Policy.A

closely relatedmeasure

thatworks

mostly through controlling internationalliquidity aggregationwithin thecountryis activemanagement

ofbank

reservesand

capitaladequacy

ratios,and

possibly international liquidity ratios.The

model

sketchedabove

hints thattheleveloftheseratiosshouldbe

increasing withrespecttothe degree of

underdevelopment

offinancial markets. In principle, these requirements alsoneed

to bemade

procyclical.There

arehowever

two

practicalproblems

with such arecommendation.

First, for those countrieswhere

the health of thebanking

system

issuspect,

weakening

standardsmay

make

a runmore

likely-

thiswas

a concern in Argentina during the recent crisis. Second, in other cases, especiallywhen

the participation offoreignbanks

is large, the policymay

be

ineffective during crises since the constraintmay

notbe

binding. Figure 12shows

the capitaladequacy

ratios fordifferent

segments

of the Chileanbanking

sector; it is apparent that foreignbanks

voluntarily withdrew.

While

there isno

doubt

that fostering the arrival of solid internationalbanks

is amust, itis alsoimportanttounderstand the implicationstheymay

have

for aggregateliquiditymanagement.

29SeeCalvo(1991)andCaballeroand Krishnamurthy

(2000).

Figure

12:

Risk

Capital Ratios

of Chilean

Banks

—

Foreign Banks—

Banco del Estado-Domestic Private Banks -Financial Soc.

Capitalcontrols can

supplement

sterilization or, in principle,slow

down

capital inflows (perhapsofa targeted maturity)by

themselves.But

there arefour caveatstothem.i)

At

the very least they shouldbe

made

contingenton

the availability of external flows,loweringthem

duringexternal crises.ii) Since an important part of the volatility in capital flows

seems

tobe

causedby

suppliers'

problems

(e.g.hedge

funds), itmay

be worth

considering requiring liquidity-ratiosfrom

them

aswell.iii) Also, the domestic "under-insurance" externality is likely to be

more

pronounced

atthe short

end

ofthe spectrum. Thus, controls shouldbe

biasedtoward

reducing short-term capital flows.Having

said this, Imust

admit concern with theemerging

"consensus" that developingeconomies

have

excessive short-termborrowing

relative to their international reserves.At

some

level the claim istrivially right -it is impossible to

have

a liquiditycrisis ifthe country holdsmore

reserves than short-term debt

and

renewals.At

another, figure 13shows

thatemerging economies

aremuch

more

prudent than developed ones along this margin.Running

aneconomy

with all the precautions that "well-behaved"emerging

economies

do

is extremely expensive.Borrowing

only long-term30Thisargument

isdifferentfromthatwhichseestheproblemon"noisy" speculatorswhoconcentrateonshortterm

capitalflows(seebelow).

31Thefigurehas tobeinterpretedwith caution, nonetheless, sincean importantdifferencebetween developed and developingeconomiesisthatthelatteroften havetoissue a largershareoftheirdebtinforeign currency.

iv)

(expensive)

and

holding largeamount

of reserveswould

most

likely be considered verypoor

management

of an average U.S. corporation.What

isimportanthereis todetermine

how

largethis ratioisrelative towhat

the country'sinstitutions

and

financial markets can support. Putting allemerging

markets, regardlessoffinancial development, inthesame

bag

is likely tobe

unnecessarilyburdensome

forthemost developed

oftheseeconomies

Most

importantly, while the controlsdescribedabove

may

be

justifiable in terms ofstatic second-bestarguments, they arelikely tohurtinthemedium-run

once

theendogenous

arrival of internationalmarket

makers and

corporategovernance

improvements

are considered (see the discussionon

integration for further discussionofthisissue).Figure

13:

Precautionary Reserves

(a)Reservesover imports(%) (b)Reservesoverexternaldebt(%)

Aioanflna CNto Mexico Auahala Canada Norway U.S.

Notes:Data for1997,exceptNorwaydatainpanel(b) (1993).External debt for developedcountries:BPS(IMF).Externaldebt for

emergingeconomiesisthesumof debtsecuritiesissuedabroad,Bradybonds,bankloans, tradecreditandmultilateral claims.

Externaldebt for developedcountriesisthesumof debtsecuritiesandother investment(including loans,depositsandtradecredits)

accordingtotheIMFclassification.Sources:ReservesandImports:1FS.ExternalDebtfor developingcountries:joint BIS,IMF,

OECD,World BankStatistics.

Caveats

on

theExchange

Rate

System.Aside from

the standard considerations,and

the contingent aspectofitthatIdiscussin the next subsection, theperspective highlightedin thispaperpoints atthree additional onesinrelation to sterilization:i) Sincethe optimal policyis

one

ofreallocationofinternational reservesfrom

high tolow

capital flow states, it clearly has anelement

of realexchange

rate stabilization.Reserve

management

must be

activeand

transparent.ii)

While

Mundell-Fleming

type considerations give anedge

to flexibleexchange

rate systems if sterilization is to

be

tried, it can beshown

that this advantage, ifsystematically utilized, can

be

non-Paretoand

may

eventually reduce the incentives to supply international liquidity.32 In other words, if sterilization succeedsby

choking

intermediation duringbooms,

it also represents a taxon

savers

and

liquidityprovidersin general.iii)

On

the other hand, a fixedexchange

rate system probably requires that a very large share ofthe country's international liquidity be heldby

the centralbank

(ormandated on

the private sector)ifit isto succeedintheimproving

the use ofthis liquidity.Unconditionally, I

would

probably advocate aflexibleexchange

ratesystem

coupled with a very active—

but explicitand

contingent (see below)-

reservemanagement

strategyand

a nontradeables inflation target. Ifcredibilityproblems

are ofthe essence, fixedmay

be

theway

togo

while still preserving the reservemanagement

strategy,which

in thiscase

may

require potentially costlymandatory

international liquidityrequirements and/or taxeson

capitalflows.A

closeeyemust

be kepton

theconsequences

ofthese policiesforprivate sector'sincentivetohoard

and

produce

internationalliquidity.Labor

Markets.Most

countriesin theregion are inneed

ofamodern

labor code,and

the pervasiveincome

inequalityproblem

that affectsthem

adds a series of additional complications to this task.But

for the purpose of this section, themain

point toemphasize

is the fact that—

leveragedby

financialproblems

—

LatinAmerican

economies

areexposed

tomuch

larger short-term adjustment needs.These

are highly unlikely tobeaccommodated

fully—

and

toadifferentdegree in different countries—by

exchange

ratemovements.

Thus

thenew

laborcode

must

allow for amore

or less automatic recession/crisis-package. I believe, for example, that following the advice of thosethat argue thattemporary contractshave

notbeen

effectiveinEurope, as Argentina32Anadditionalpoint against afullyflexibleexchangeratesystemisthattheitmaynotbepossibleforanindividual

country to allow thedevelopment ofsufficiendydeepcurrency-riskhedginginstruments.Investorsmayusethemtohedge

theriskon neighbors' currencies,ifthesedonothavetheirowndeep hedgingmarkets.ThiswasaproblemforMexico

aroundtheBrazilianturmoilduring 1998-99,andit isa particularly seriousconcernifthecountry'sfinancialmarketsare

notdeep enough.