Containing the Opposition:

Selective Representation

inJordan and Turkey

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTEBy

JUL 16 2009

Raffaela Lisette Wakeman

Submitted to the Department of Political Science

LIBRARIES

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster of Science and Bachelor of Science in Political Science at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2009

© 2009 Raffaela Wakeman All rights reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or

hereafter created.

A uthor: ... ... ... Department of Political Science

May 22, 2009 Certified by: ... ... ... . ... Orit Kedar Associate Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor Certified by: ...

- - arles H. Stewart, III Professor of Political Science Second Reader

Accepted by: ... ... ... ... ... Roger D. Petersen

Chairman, Graduate Program Committee Accepted by: ... ...

Proiies H. Stewart, III Professor and Head, Department of Political Science

ARCHIVES

2 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 2 ._=: -. -- -- _ ' - '... ...Abstract

How does elite manipulation of election mechanisms affect the representation of political regime opponents? While the spread of elections has reached all the continents, the number of

actual democracies has not increased at a comparable rate. If anything, observers have learned that the presence of elections in a country does not necessarily mean that it is also a democracy.

This thesis addresses an underexplored topic in the study of electoral politics: the manipulation of election systems in order to achieve selective representation.

I focus on the experience of opposition parties in two cases, Jordan and Turkey, an autocracy and a democracy, to analyze the impact of engineered election mechanisms on their representation. I contend that parties in power exploit the rules of the electoral game to contain their opposition. This is done by different mechanisms, depending on the makeup of the country

and the options available to the manipulators. Mechanisms of electoral systems are used to reduce the representation of groups that are considered a threat, and to amplify the representation

of those groups that the regime would like to strengthen. Analyzing the effect of malapportioned seats and the use of a single non-transferable voting system in Jordan on the Islamic Action Front Party (IAF), the main political rival to traditional tribal politicians, I expose the power of these targeted electoral mechanisms for control. Examining how the 10% national election threshold

in Turkey affects representation of the Islamist political parties in the Grand National Assembly uncovers the distorting effect of this universal mechanism on representation.

I analyze the election results for the 1993, 1997, and 2003 parliamentary elections in Jordan, measuring malapportionment and the variation in turnout. While the motivations for the Hashemite regime are to maintain stability and power in their country, I show that there are unintended consequences for this manipulation through an analysis of turnout and a policy study

of honor crimes, the cause of the majority of Jordanian women's deaths every year.

I examine Turkey's elections since 1961, calculating the difference between vote share and seat share, which uncovers an increase in the disparity between votes and seats since the installation of the election threshold. I conduct a counterfactual analysis, using a set of districts and reallocating the seats in each district using a 5% national election threshold instead of the current 10% threshold. Even by lowering the threshold this much, there is a much more equal representation of votes in the parliament.

Electoral systems are engineered to suit the country in question. While the characteristics of states and election mechanisms used in each country are without a doubt different and specific to each case, the concept of representation is universal to all systems. In both Jordan and Turkey, the end goal of containing the opposition has not necessarily been reached: the Hashemite regime and its tribal loyalists don't see eye to eye on all issues, while in Turkey the AKP, a conservative Islamist political party, has overcome the obstacles to become the beneficiary of the threshold.

Table of Contents

Abstract 3

Figures 5

Tables 6

1. Engineering the Opposition Out 7

2. Universal and Targeted Mechanisms for Control 16 3. A Model for Authoritarians: Votes without Seats 42 4. Targeted Control of Islamists: Jordan and Malapportionment 58

5. Turkey's Struggle With Democracy 86

5. Universal Control in Turkey: The Election Threshold 109

7. The Implications of Manipulation 140

8. Containing the Opposition 152

Appendix A 158

Appendix B 161

Appendix C 164

Figures

3-1: Govemorates of Jordan 42

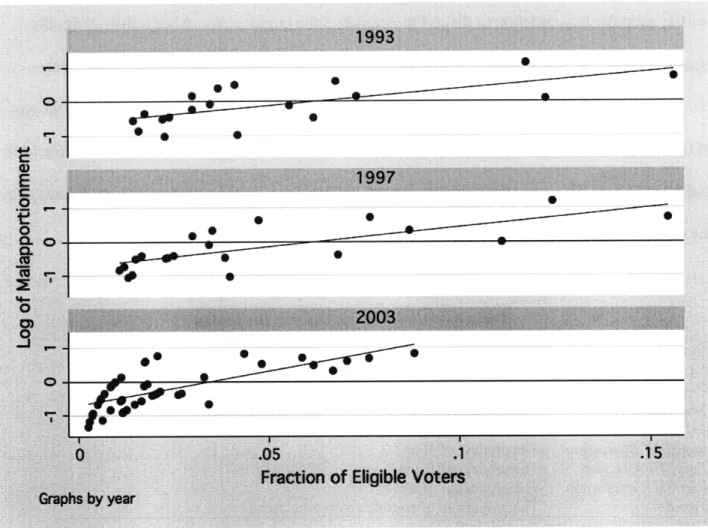

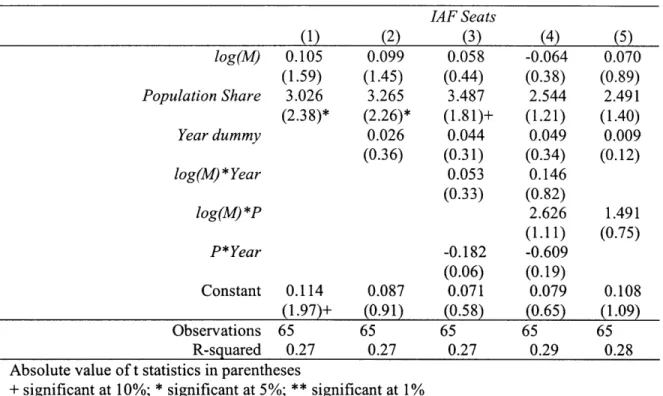

4-1: Malapportionment in Jordan 66

4-2: Population Size and Malapportionment 67

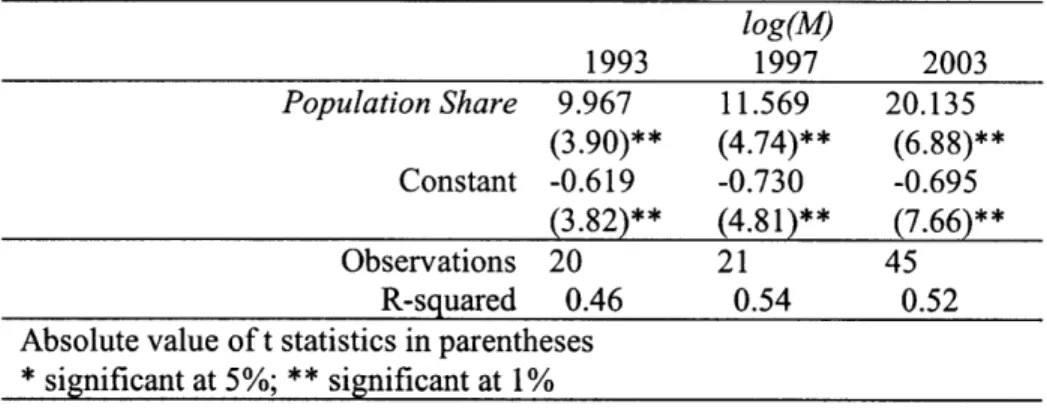

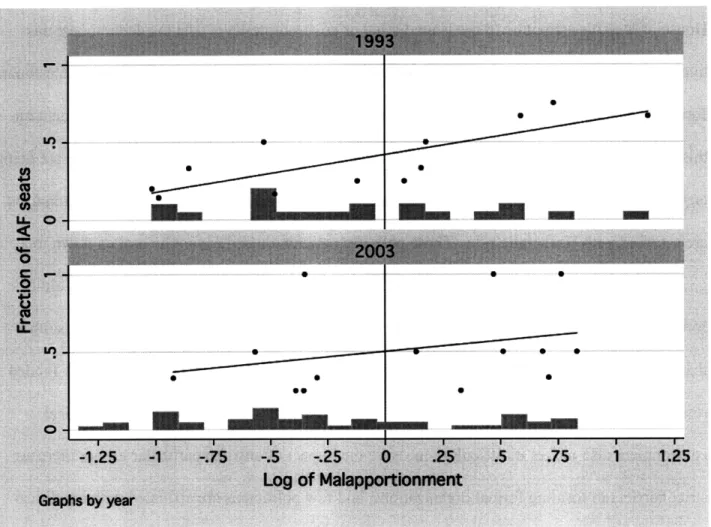

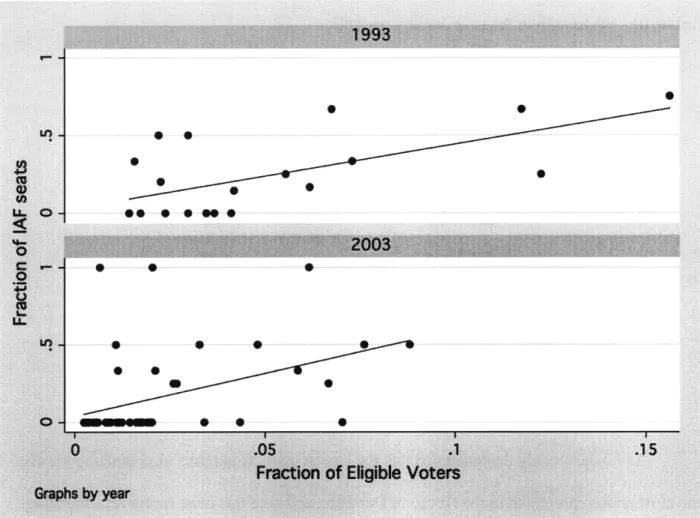

4-3: 1993 and 2003 Malapportionment and IAF Success 72 4-4: Aggregate IAF success as a function of Malapportionment 74

4-5: Population and IAF Success 76

4-6: 1993- 2003 Malapportionment and 2007 IAF results 80 4-7: Malapportionment and Turnout in Jordan's elections 81 4-8: Participation and proportion of Jordan's Population 82 4-9: Causal Relationship of Targeted Mechanisms 84

5-1: Turkey's Administrative Divisions 101

5-2: Evolution of Turkish Parties 104

6-1: Islamist Parties' Province-level Results 117 6-2: District-level seat-vote disproportionality for the Islamist party 120

6-3: From Votes to Seats: 1973-2007 124

6-4: Vote-Seat shares for winning parties 127 6-5: 1961-1977 Vote and Seat Share for Select Districts, T=O 132

6-6: 10% Threshold- 1983-2007 134

6-7: 1983-2007 Results with 5% Election Threshold 135

Tables

2-1: Fitting Characteristics of Democratic Systems to Jordan and Turkey 35

3-1: The Evolution of Jordan's Electoral System 52

3-2: Distribution of Seats by Governorate, 2003-present 53

4-1: Mean Vote Share for Winners 61

4-2: Vote Distribution for Winners: By Governorate 62

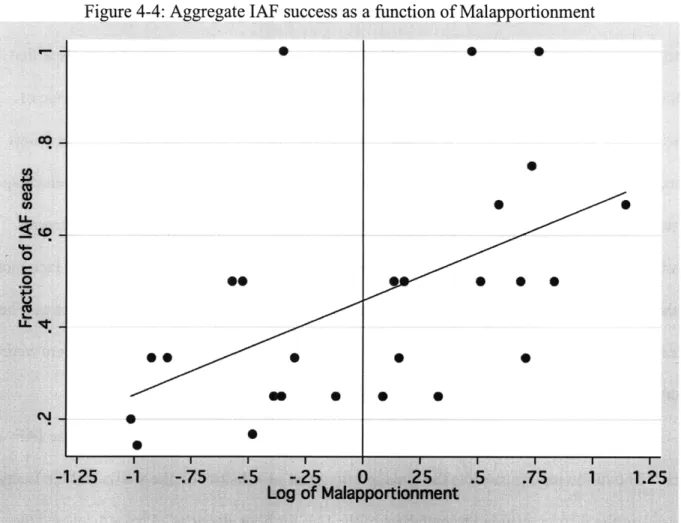

4-3: Governorate malapportionment and population distribution 65

4-4: Variables in Analysis for Jordan 68

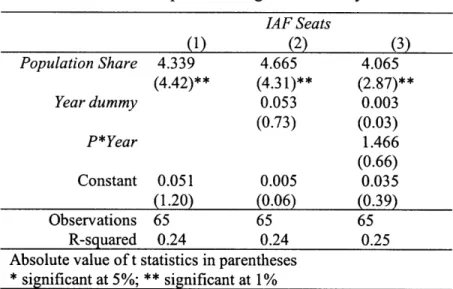

4-5: Regression Analysis of Population and Malapportionment 69

4-6: Quotas and Minorities in Jordan 70

4-7: IAF Seats and Malapportionment 75

4-8: Population Regression Analysis 77

4-9: Multivariate regression analysis on IAF success 78

4-10: Explaining the Variation in Turnout 83

5-1: Constitutional Court Design across democracies 98

5-2: Turkey's Political Parties 103

5-3: Evolution of the Turkish Electoral System 106

5-4: Islamist Performance, 1973-2007 108

6-1: The Turkish Electoral System since 1961: Institutionalized Repression 113 6-2: Nationwide Disproportionality in Turkey's Elections 115 6-3: Islamist party election results in select provinces 119

6-4: Islamist Party Results Based on District Size 122

6-5: D'Hondt Method: Kayseri 1995 130

6-6: Representation in Select Districts in Turkey 138

7-1: Number of Parties in the Grand National Assembly 149 B-1: The 1993 House of Deputies Election- Turnout and Malapportionment 161 B-2: The 1997 House of Deputies Election- Turnout and Malapportionment 162 B-3: The 2003 House of Deputies Election- Turnout and Malapportionment 163

C-1: Turkey 1961-1977 Elections 164

Chapter 1

Engineering the Opposition Out

How does elite manipulation of election mechanisms affect the representation of political regime opponents? This thesis addresses an underexplored topic in the study of electoral politics: the manipulation of election systems in order to achieve selective representation.

Although multitudes of questions about elections have been answered by equally numerous studies of electoral systems, a new set of issues has yet to be addressed due to the "third wave" of democratization and the resulting diffusion of elections across the globe; from elections in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein to South Africans going to the ballot box, to the King of Morocco incorporating popularly elected legislatures into his government, voting has become almost as ubiquitous as Coca-Cola or McDonalds (Huntington 1991). While the spread of elections has reached all the continents, however, the number of actual democracies has not increased at a comparable rate. Some leaders new to elections have exploited the iconic image of "Election Day" to meet their particular needs (i.e. to stay in power), and others have simply ignored the process while simultaneously endorsing their elections as "free and fair." If anything, observers have learned from this "third wave" that the presence of does not necessarily mean that it is also a democracy. Indeed, several leaders have taken advantage of some electoral

mechanisms to maintain their power or simply to prevent their opponents from ever gaining government representation. While these issues have arisen recently, few, if any of them, have been addressed. In addition, the typical measures by which to judge an electoral system do not necessarily fit these unconventional systems. Whereas many established democracies were

popular movements for representative government, in many cases these newcomers are approaching the process from the top down.

Over all, the world has welcomed the advent of elections to these countries. Justifying the means by the ends has been the general rule of thumb for the states providing economic aid, military support, and legitimacy to these governments. Individual cases, however, of

malapportionment or vote buying, just two of the many methods available, have contaminated the pristine picture of elections we have in our minds.

Another trend related to the onset of "third wave" elections is the rise of a different type of politics. Whether they are religious, cult-like, or separatist, these new political organizations pose unfamiliar threats to the governments in power. Some scholars point to these approaches to politics as the catalyst behind electoral engineering in the first place, while others contend that by

including these groups in policymaking, their positions will moderate, essentially removing the necessity for electoral manipulation.

Recently, Islamist political parties have been gaining public attention in both Jordan and Turkey: the AKP, or Justice and Development Party has controlled a super majority of seats in the 550-seat Turkish Grand National Assembly since 2002, reducing the other parties in Turkey to minority status, while the Jordanian Islamic Action Front Party has experienced a significant decline in its seat share in the House of Deputies. In Turkey, the AKP was brought to the

Constitutional Court in the summer of 2008, and just barely escaped being banned from politics. In Jordan, the IAF attributes its recent losses to the electoral system: a single non transferable vote system (or SNTV), in which voters in multimember districts are only given one vote, combined with system-wide malapportionment caused their defeat in the 2007 elections.

This study addresses the experience of opposition parties in these two cases, an autocracy and a democracy, to analyze the effect of engineered election mechanisms on their

representation. How representative is Jordan's House of Deputies? Besides the absence of the "one person, one vote" principle (despite assurances from the monarchy that their system does fulfill this principle), does this mechanism have additional effects on elections? What about Turkey- how much is the abnormally high threshold influencing representation? Are these mechanisms deliberately built into the system to contain the regimes' rivals?

Both Turkey and Jordan are dependent on their American and European allies for military support and economic support. For Jordan, its close relationship with the West has pressured the ruling Hashemite monarchy to reinstitute elections; while from the outside these elections appear to be "democratic," the mechanisms in place work to repress citizens' votes. In fact, the only election results that are ever made public are the winning candidates' vote shares and turnout.

For Turkey, its relationship to the West has another dimension: Turkey is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and is currently in negotiations to become a full member of the European Union (EU). Turkey's human rights record, conflict with the separatist Kurds, and repeated

election interference by unelected government officials are all issues that must be resolved before its membership in the EU is finalized. Statements from the EU regarding a future Turkish membership cite the abnormally high election threshold as another source of controversy.

Argument

This study argues that parties in power exploit the rules of the electoral game to contain their opposition. This is done by exploiting different mechanisms, depending on the makeup of the country and the options available to the manipulators. Mechanisms of electoral systems are used to reduce the representation of groups that are considered a threat, and to amplify the representation of those groups that the regime would like to strengthen.

In the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, for instance, while there have been both reapportionment and election law reform recently, critics claim that these changes are being made to maintain the status quo, not to enhance democracy. Jordan is not technically considered one of the "third wave" countries, but the recent return of elections provides a strong basis for questioning the merits of its electoral system. Widespread malapportionment in Jordan,

especially the drastic underrepresentation of the most densely populated regions of the country, profoundly distorts the people's voice. The SNTV system also compromises the level of representation by limiting voters to one vote, despite their district being represented by several MPs. This misrepresentation has reverberating effects throughout the system. Focusing on

Election Day effects, the underrepresented districts turn out to vote at much lower rates than in the overrepresented regions. Through the policy analysis of honor crimes, I also speculate on the relationship between malapportionment and the refusal of the House of Deputies to increase the penalty for committing an honor killing.

In some more established democracies, elections have existed for quite some time, but with meddling by unelected officials. Turkey's experience with popularly elected legislatures is almost a century long, but the frequent intervention by non-elected officers (whether it be the military establishment through military coups or the Constitutional Court with political party

bans) has also raised questions as to what "free and fair" actually means in Turkey. Turkey's long history with elections places it out of the category of "third wave" countries, but frequent interventions by unelected political elites and an exceptionally high national election threshold place large barriers to political parties seeking seats in the Grand National Assembly. By requiring parties to win the 10% of the votes, Turkey's system keeps smaller parties out of the government. I discuss the strength of these mechanisms in advancing the political agenda of the regime.

Case Selection: Jordan and Turkey

Turkey and Jordan were chosen as the case studies for this research for several reasons. In both countries, the regime has used strict definitions of nationalism to create a specific national identity for its citizens- while permitting all of its inhabitants, regardless of ethnicity or religion, to become citizens, even separatist ethnic groups (in Turkey the Kurds are in this position, while in Jordan it is the Palestinians), the regime represses expression of alternative identities. In addition, both countries are in the midst of a debate over the role of Islam in politics.

In Turkey, the ruling AKP has roots in previous banned Islamic political parties, and was almost the target of another Constitutional Court banning in 2008. In Jordan, the Islamic Action Front has suffered declining seat shares in the House of Deputies since its formation. In both countries, however, there is little danger of domestic religious terrorism and internal threats, despite Muslim majority populations, proximity to other conflicts, and close relationships with Western countries and Israel. Turkey and Jordan are also unique in that religious-oriented

as the separation of church and state frequently steers modern states' courses towards democracy.

There are a number of differences between these two countries that should also be discussed. Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, with ultimate power vested in the King and the council of ministers (who are all appointed by the king). Jordan can best be characterized as an authoritarian regime transitioning to democracy. Turkey, on the other hand, is a constitutional republic, with strict separation of powers and a long history with democratically elected governments. Jordan is an Arab Muslim-majority country, while Turkey is a state without an Arab-majority (but the majority of Turks are Muslim). The electoral systems in Jordan and Turkey are also quite different: Turkey has a party-list proportional representation (PR) with multi-member electoral districts, while Jordan uses a single non transferable voting (SNTV) system, in which voters can vote for one candidate to represent them in multi member districts. Turkey has a history of political parties, and Jordanians do not generally affiliate with political parties; instead, Jordanians tend to vote for a tribal or familial candidate. The mechanisms for control are different as well, targeting specific stages in the election process, but ultimately end up affection the representation of votes.

Plan

This research will examine the effect of electoral mechanisms on representation in Jordan and Turkey. In Chapter 2, I discuss the theory and relevant literature regarding Jordan's

liberalization path, Turkey's electoral politics, general democratization and election systems. I focus on features of electoral systems, including malapportionment (deliberately allocating government representation that are not distributed according to population) and election

thresholds (a minimum vote requirement that political parties must reach in order to win any seats in the legislature). I probe the variation in electoral systems, and discuss majority-rule two party systems and proportional representation systems (PR). PR systems are organized in two forms: either voters choose their preferred party, and all party candidates are arranged in a list, or individual candidates run in each election (supported typically by a party), and voters select their preferred candidate. Single non-transferable voting systems fit fully under neither majoritarian nor consensual systems: voters can vote for one candidate despite the fact that the districts have multiple representatives.

I examine the literature on regimes transitioning to democracy, the role of unelected officials in elections, and the effects of electoral reform on party systems. Are there visible consequences of installing these mechanisms into election systems? One of the motivations behind pursuing integrating electoral systems into governments, at least in the cases of Jordan and Turkey, is to continue receiving aid from their powerful Western allies. The domestic

pressures on both governments, especially policies regarding the activity of ethnic minorities and religious political parties, seem to be pushing the regime toward manipulation.

In Chapter 3 I provide historical sketches of Jordan. In Jordan, the concept of defensive democratization, best articulated by Robinson (1999), characterizes the method of governance exercised by the Hashemite regime. Much of Jordan's domestic policy is heavily influenced by the Arab-Israeli conflict and the status of Palestinians in the West Bank. Jordan's past experience with elections and its relationship with the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood and its political arm, the Islamic Action Front, provide perspectives on reasoning behind the current electoral system.

In Chapter 4, I analyze Jordan's electoral results from 1993, 1997, and 2003. Despite the severe data limitations, there are significant findings on the variation in turnout as well as

evidence to explain the declining success of the Islamic Action Front, the main Islamist political party in Jordan. Jordan's malapportionment not only skews the balance of power in the House of Deputies from the most populous districts to the strongest traditional rural allies, but also impacts the rate at which citizens turn out on Election Day.

Chapter 5 discusses the evolution of Turkey's electoral system and relevant history. Turkey's history with popularly elected governments reaches back almost to its independence in 1923, but this lengthy experience is slightly misleading: several interventions by the military as well as party bans by the Constitutional Court prevent Turkey from being a full-fledged

democracy. Turkey's secular, centralized outlook on government and nationalism has resulted in repression of organized movements for ethnic or religious identity.

In Chapter 6, I study Turkey's elections from 1961 to 2007. The large amount of data allow me to analyze the evolution of Turkey's electoral system, with a special focus on the effects of the 10% national election threshold used since 1983. The 10% election threshold poses a very high barrier to entrance into government. There is a great deal of variation on district magnitude (DM), with districts with as few as three representatives to as many as sixty. By aggregating results from 1961 to 2007, I show that the Grand National Assembly today is much less representative of voters' preferences than before the threshold was imposed. I study the results in several districts specifically to illustrate the impact of the threshold with a stronger lens. I also propose a counterfactual analysis in Turkey: by lowering the national threshold to

5%, how would representation in the Grand National Assembly been different?

In Chapter 7, I discuss the effect of the electoral system mechanisms on both countries: in Jordan, the legal and social problems created by its incredibly high rate of honor crimes place both the regime and elected politicians in quite surprising positions. Honor crimes, or the killing

of a family member (usually a woman) for bringing shame upon the family's name, are prevalent in Jordan. These crimes receive lesser punishments in many several countries (and are not

limited to Muslim countries). In 2004, King Abdallah II and the upper house of parliament proposed changes to its laws, in an attempt to increase punishment of honor killings to be comparable to other forms of murder. When the law was brought to the House of Deputies, however, it was voted down. As the roll call vote for this and other legislation is unavailable, I review the arguments on either side of this debate, and speculate as to whom voted against the bills. In Turkey, the universality of the election threshold as a mechanism has resulted in the rise to power of military opponents. The AKP's popularity and success at the polls served to help the party overcome the barrier posed by the election threshold and win large pluralities in the last two elections.

I conclude my research in Chapter 8 with a summary of my findings and discussion on the implication of my research. The approach taken in this project can be extended to other countries, and research on Turkey can now be focused on examining the effects of these

mechanisms on legislation and law. The status of Jordan's 'democratization' can now be put into perspective. The experience of each country demonstrates that despite a regime's efforts to maintain the control over election results, with the proper support from the public, the opposition can overcome and in some cases, reap the rewards of these mechanisms to the detriment of the ruling regime.

Chapter 2

Universal and Targeted Mechanisms for Control

Politics in Turkey and Jordan have generated a great deal of research and discussion. A prominent approach is postulating on the impact of politics and elections on ethnic out-groups in each country- the Palestinians and Kurds. Because of the governments' refusal to report the ethnic makeup of their countries, however, it is difficult to make more than suppositions on this subject. A large focus in both countries is on the role of Islamist political parties and leaders in government and policymaking. In Jordan the power assigned to these leaders has been limited, so scholars have instead focused on the evolution and internal functions of Islamist political parties there. A frequent angle in discussions of Turkey's experience with Islamist parties is studying the reaction of the military and Constitutional Court to them.

The role of the "clash of civilizations" has produced a new body of research focused on cultural "exceptionalism," the idea that certain groups are resistant to adopting democracy in their countries. While many state the problems of the Turkish and Jordanian electoral systems in passing, there is still a remaining question: how have the mechanisms in each system affected representation in each country's legislature?

In this chapter, I discuss the literature related to Jordan's democratization and Turkey's electoral politics. Then I review electoral system design, electoral engineering and the systems in Jordan and Turkey. I discuss the concept of representation and propose hypotheses for each country on the effects of specific electoral mechanisms on representation of its citizens.

The Current Focus: Ethnic Minorities and Islamists

Scholars have approached the study of election reform in Jordan from several angles: examining the effect of malapportionment on the Palestinian population, conducting historical analyses of Islamic political parties, studying the role of political parties in the political system, and speculating on the motivation for electoral reform. A frequently discussed controversy regarding democratization in Jordan is that although Palestinians are offered full citizenship with voting rights, they are underrepresented in the Parliament as well as in the rest of the state

machinery (Lust-Okar 2007). While the Hashemite government will not release the official population breakdown of Palestinians and Jordanians, many explain the underrepresentation of urban areas like Amman and Zarqa by pointing out the large concentration of Palestinians there.

The history of elections in Turkey is plagued with interventions by the military and unelected Constitutional Courts. This interference with democracy poses a threat to Turkey's EU bid. The recent failure of the Constitutional Court to ban the ruling AKP and the persistence of Prime Minister Erdogan in standing up to military threats indicate at least a temporary change of course. In this section, I also discuss previous approaches to the study of Turkey's elections, and note the gaps in the literature on this topic.

Elections and democracy in Turkey have been approached in several ways. Scholars have considered Turkey's Muslim heritage and the presence of democracy as a sign that it is an exception to the rule of the incompatibility of these two ideas. Another dimension of analysis has been to measure the effect of Turkey's elections on the Kurds; examining voting patterns has, however, been difficult, as Turkey does not collect ethnic or religious data in its censuses. Finally, academics have also studied the intersection of Muslim law and Turkish politics by examining Constitutional Court decisions and political debates related to religious practice.

Muslim/Arab/Cultural Exceptionalism

Overshadowing a great deal of work on elections in developing and young democracies is the theory of "exceptionalism:" the idea that certain cultures and religions are especially resistant to democratic governance. Stepan and Robertson (2003) first examine electoral competition (using Polity IV, Freedom House scores and GDP) across Muslim-majority countries, finding that non-Arab Muslim states have been more electorally competitive that Arab Muslim states. While they are hesitant to equate electoral competitiveness with democracy, their evidence seems to revise the theory of Muslim exceptionalism to be include only Arab countries. One significant point that takes away from their conclusion is that many of these states are either developing countries (Jordan, Libya, Morocco), or significant allies of Western countries (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait). Developing countries are, regardless of ethnic or religious composition, overall less "free" and electorally competitive than developed countries. The other classification of many of these countries, U.S. allies, may be at lower levels of freedom and democracy than others because U.S. support and aid is keeping the authoritarian regime in power.

To provide further justification for the use of Arab exceptionalism over Muslim

exceptionalism, Angrist (2004) examines the number of parties, the level of polarization, and the presence (or absence) of mobilization asymmetry across Muslim countries to explain the

presence of competitive political institutions in Turkey. Although the newly independent Turkish state started out on its democratization path at the same time and under similar outer conditions as other Muslim countries, the establishment of a two party system instead of a single or multi party system and the lack of occupying power (after the Ottoman Empire collapsed) were the determining factors in explaining Turkey's successful path to democracy (Angrist

2004). Ultimately Turkey adopted a PR system, which resulted in the creation of a multi party system and depolarization of politics.

Ghalioun (2004) and Lakoff (2004) debate the theory of Arab exceptionalism (and specifically the results from Stepan and Robertson (2003)), with Ghalioun turning the focus to the persistence of authoritarianism in Arab countries. Lakoff (2004) counters Stepan and Robertson's (2003) analyses: Lakoff (2004) finds that using GDP and electoral competitiveness ignores the abundance of cases of undemocratic non-Arab Muslim majority countries of Central Asia (the "stans," as he refers to them) and Iran. In a later paper, Stepan and Robertson (2004) discuss the lack of well-developed responses to those arguments. Harik (2006) counters the theory generated by Freedom House studies of Arab and Muslim countries finding that they are exceptionally resistant to democracy. Harik (2006) finds that the measurement scale has been improperly applied to developing countries, which include many Arab and Muslim countries, and that the finding of "exceptionalism" is based on misinterpretations of fact and misuse of the Freedom House scale.

Inglehart and Norris (2003) examine public opinion data from Muslim countries,

suggesting that the "cultural fault line that divides the West and the Muslim World" is related to sex, not democracy. While Muslims around the world support democracy as much as

Westerners, they do not hold the same attitudes about marriage, women's rights, and sexual freedom as Americans (Inglehart and Norris 2003). While the disparity between Western and Muslim public opinion on these topics is quite large, I hesitate to say that Westerners hold remarkably different views about marriage, gender equality and sexuality from Muslims: abortion, for example, is a highly controversial topic in the Western world (only 48% believe that it can always be justified) as well as in the Muslim world (25% believe that abortion can

always be justified). The presence of a large disparity in public opinion does not necessarily mean that there is a "clash of civilizations," as Inglehart and Norris (2003) contend.

Mazrui (2004) traces the history of the relationship between the United States and

Muslim countries, organizing them into four phases. The post-9/11 phase is characterized by the exploitation of fear by the Bush administration to wage the war on terrorism. He notes that despite the administration's contentions that the war is not on Islam, it has been Muslims who've paid the price for Al Qaeda's actions, which has strained U.S. relations with Muslim countries (Mazrui 2004).

Volpi (2004) examines the institutional mechanisms in Muslim countries that are preventing full democratization. He shies away from the traditional binary classification of democracies and autocracies, and promotes a third middle ground of pseudo-democratic regimes using the struggle between liberalism, republicanism, and Islamism in these countries as a basis for his categorization. Volpi (2004) notes that Western conceptions of democracy coincide with liberal practices and norms, which conflict with the state of policies and opinions in the Muslim world, which tend to be more conservative and less progressive (at least with regards to civil liberties and women's rights). He criticizes the requirement that democracies must produce liberal policies.

With regard to republicanism, Volpi (2004) criticizes the application of it to Muslim countries, suggesting that civil society and group dynamics in the Muslim world have a view of republicanism distinct from the Western model, combining the principles of republicanism with what he calls asabiyya, an organizational system centered around tribes and communities rather than political parties. Former asabiyya models were used as the bases for a monarchic system,

whereas the new model aims to legitimate limited democratic rule because it supports nationalist and economic development agendas (Volpi 2004).

A serious issue in the study of Jordan's politics is that it continuously refers to the lack of political parties as a reason for the faux democratization Robinson (1997), Schwedler (1998) and other point out. In addition, Lust-Okar (2007) and others treat the Islamic Action Front as a powerful player in Jordanian politics, simply because it is the only formal political organization (at least according to Western standards) to win seats in the House of Deputies. As appealing explanations as these may be, they do not accurately explain politics in Jordan. Jordanians vote for candidates based upon the candidates' mutual affiliation with a tribe or other social

organization. Consistently, however, scholars point to the failure of the election of the

"opposition" to be a prime reason why Jordan's liberalization path is inadequate (Ryan 1998). There have been numerous political parties competing in Jordan's elections, but few have

succeeded in winning seats in the House of Deputies. The only political party to consistently win multiple seats in elections is the Islamic Action Front Party.

What is often overlooked is that Jordanians themselves either do not know or are not concerned about the success of political parties (CSS Public Opinion Survey 2006). Indeed, polling data indicates that the most representative political party was the Islamic Action Front, which 4.2% of respondents chose as representative. When asked which of the current political parties in Jordan were qualified to form a government, 90.4% of the respondents said "none." The majority of respondents (65.8%) consider a political party to be "a political organization that seeks to participate in the political process without assuming power." If Jordanians do not even see political parties as central players in politics, how can they be expected to form them or join them? Jordanians largely do not recognize the names of political parties: 47.4% knew the name

of the Islamic Action Front and 25.1% recognized the National Constitutional Party. Jordanian political parties clearly have failed to reach out to citizens to garner support. For this reason, Volpi's (2004) model fits the political space in Jordan much better than the political party system organization suggested by others.

Volpi's (2004) modification of the democracy-authoritarianism spectrum to include a middle ground status provides space to consider democratizing Muslim countries separately, not quite at a state of established democracy like Turkey, and yet not truly in the "authoritarian" category either. While in Western democracies the concept of separation of church and state plays a major role in understanding the concept of representative government, it is not necessarily the case in Muslim countries.

While Angrist's (2004) argument explains Turkey's early history, it virtually ignores the fact that the military has frequently intervened in the political process and frozen representative government for years at a time. An outstanding question on Turkey's seemingly unusual status is how the regime's emphasis since independence has been on the strict separation of religion and politics. Religion-oriented parties are banned, and religious expression is virtually banned in public. Perhaps Turkey's legacy as a secular government, with a Muslim identity that is

secondary its national identity, plays a stronger role than the literature is willing to suggest.

Islamist political parties

Questions surrounding the recent participation in both countries by religion-oriented political organizations have resulted in research on the intersection between Islam and politics. In

Turkey, the Constitutional Court has stepped in frequently to remove religious parties from politics until very recently, with the rise of the Justice and Development (AKP) Party, a

conservative, Islamist political party. In Jordan, the decreasing popularity of the Islamic Action Front Party have raised questions as to the fairness of Jordan's apportionment and the goals of the IAF.

In her study of the history of Jordanian political parties, Lust-Okar (2001) examines the political party system through two lenses: party strength and party-system strengths. She points to the Islamic Action Front as the "single strongest party in the kingdom." This statement, however, is misleading: political parties in Jordan garner very little power or popularity in the political system: the power rests in the regime-loyalists and ultimately the regime itself. Independent candidates win the majority of the seats in the House of Deputies (84.6% in the 2003 elections). Tribal constituencies usually support these independent candidates. Lust-Okar (2001) also postulates that candidates in Jordan do not fight for power, but instead for patronage of the Hashemites.

In studying Islamists and/or political parties, scholars assume that the state and Islamist groups are not only two separate entities, but also that they have two choices in dealing with each other: cooperation or conflict. The relationship between political organizations and the state tends to be examined on a continuum; this is also the case for the study of Islamist parties. Langohr (2001) proposes a third option: that Islamists have, as well-educated citizens, been successful in placing themselves in government positions which then allow them to better pursue their agenda. This consideration helps understand why Islamist movements decide to pursue more moderate political agendas and stances when included in politics (Langohr 2001).

Indeed, Schwedler (1998) finds that Islamist parties are not scheming to take over their governments, but instead as they are forced to work in a pluralist system, their positions actually moderate. "The real question is not whether Islamists pose a threat, but what political agendas

are served by continuing to paint Islamists as a monolithic, antidemocratic mob" (Schwedler 1998). She also criticizes others for ignoring the regimes that are manipulating the outcomes of elections and instead focusing on the Islamists (Schwedler 1998). Robinson (1997) points out that the inclusion of Islamists in the political process in Jordan led to the "creation of an integrated, establishment-oriented and moderate Islamist movement. Jordan's Islamists have proved themselves to be capable democrats, obeying the rules of the political game while parlaying their strength in society into a parliamentary plurality." Lust-Okar (2001) sees

international forces as a reason for the strengthening of Islamist parties in Jordan (and throughout the region).

Ahmad (1988) discusses the Turkish regime's reactions to perceived Islamic threats after the 1980 military coup. He finds that the number of cases brought to court and persons

implicated rose greatly between 1984 and 1987. He notes that 70% of these cases were dismissed, but warns that these trends are signs of the "reassertion of its Islamic identity" (Ahmad 1988). He traces Islamic politics throughout Turkey's history, finding it peaked in popularity in the 1970s, with parties across the political spectrum infusing their platforms with pro-Islamic rhetoric and the creation of explicitly Islamic political parties (although he points out that the Islamic MSP did not succeed in winning many seats in those elections) (Ahmad 1988). Ahmad (1988) presents his findings to predict the future of Islamic politics after the 1987

elections, finding that it was on the downturn, which turned out to be an inaccurate prediction. Ahmad's (1988) study provides indications of the perception of the Islamic threat to the military

and centrist-wings of Turkish politics through the 1980s. His study, however, does not provide an understanding of the public's feelings towards these Islamic "threats;" if in future elections

support for Islam-oriented parties improves, does the inclusion of fairly elected Islamic parties translate into a threat to Turkey's stability?

Giilalp (1995) traces the history of the Islamic RP, the ruling party at the time. He discusses their views on politics and the economy, including policies with regard to the Kurdish population and Constitutional reform. He finds that since the Kurds are not allowed to organize politically, that the RP was the party they would most likely support (Giilalp 1995). His article outlines the success of the RP, and finds that the source of its success was public support for change, but does not delve into the influence of electoral mechanisms. Similarly, Yavuz (1997) also examines the 1995 election results, and the roots of the RP's successful campaign. He identifies the strict secularism inherent in Kemal's vision of the Turkish state and contends that originally, "secular" was intended to unite the diverse ethnic and religious groups in Turkey, but today "secularism" is interpreted to mean the absence of religion in politics.

Neither Yavuz (1997) nor Giilalp (1995) study the electoral mechanisms that might have influenced the RP's results in 1995. Instead, they find that these results are indicative of a shift in the Turkish public's opinion regarding the intersection of religion and politics. Mecham (2004) examines the 2002 elections and the AKP's rise to power in a similar way. He determines the institutional factors that led to the rise of an Islamic political party to power in the secular Turkish state. He points to three changes: greater freedom in political organization, which has led to the introduction of greater diversity of political ideology, the imposition of constraints on civil life on the Islamist movement, more interaction between Islamist politicians, constituencies and the state leading to greater information sharing and greater appeal for Islamist politics (Mecham 2004). In discussing the election results for Islamist parties, Mecham's (2004) analysis

notes the improvement in election returns between 1999 and 2002, but does not go further than a top-level analysis.

Previous research on Turkey and Jordan has emphasized the evolution of Islamic politics, and governmental policies regarding Kurds and Palestinians. Some scholars have found that including Islamist political parties in government moderates their platforms, in addition to postulating on the effect of laws and various aspects of the electoral system on Islamist parties. In this light, examining approaches to the study of electoral reform could be a useful tool for studying how regimes themselves manipulate the law in their favor. Posusney also calls for a scholarly effort in examining the mechanisms of electoral manipulation by regimes like those in Jordan (Posusney 1998).

Although Schwedler's work focuses on reactions to reforms in civil rights, inclusion of her work in the body of knowledge surrounding Islamist reactions to regime oppression is important. She looked at the reaction of Islamic political parties to government, specifically through public demonstrations and boycotts (Schwedler 2003). She points to the Hashemite regime's restrictions on publications and the press in 1997 as well as the 1993 elections law as the motivation for the IAF's boycott of elections that year. While the temporary law suspending these freedoms was found unconstitutional by the Higher Court of Justice in 1998, the absence of opposition members in the Parliament as a result of their boycott allowed amendments that were even more restrictive than those previously found unconstitutional. Studies like Schwedler's (2003) implicitly show that the inclusion of Islamists in the political process could force both the regime-loyalists and the radicals to moderate their positions.

Other scholars afford the Hashemites a more mild treatment by focusing on the efforts of the regime to maintain a liberal atmosphere, and build an institutionalized democratic structure

(Abu Jaber 2003). He also points out that the Hashemites emphasized steady change over a rapid switch from authoritarianism to liberal democracy, which allows the Islamists parties to

participate in democracy (Abu Jaber 2003). Abu Jaber (2003) criticizes the Western criteria that are used on Muslim countries to determine the level of democratization, much like Harik (2006) and Tessler (2005). He claims that Jordan's democratization has stood out among Arab countries because of its non-violent, liberal style (Abu Jaber 2003). The Islamist movement has been permitted to exist continuously, even during the ban on political parties. He also points to opposition candidates' entrance into elections as a sign that Jordan is unique in its approach to democratization.

According to Khoury (1981), there has been a history of Hashemite regime oppression of political opposition. The National Consultative Council, the predecessor to the Parliament, was a prime example of the regime's efforts to silence debate and prevent the opposition from

acquiring power. As it was a council appointed by King Hussein, the only powers it held were the ability to debate and to recommend the regime certain actions (Khoury 1981).

Lucas (2003), much like Khoury (1981) and Libdeh (2005), is pessimistic about the prospects for deliberalization in Jordan. He explains the change in tracks from deliberalization back to liberalization: when it is profitable for the regime to pursue democratization (i.e. when loyalists are in power in the legislature) and when it refers back to deliberalization (i.e., when the opposition is threatening the loyalists' hold on the legislature). By approaching the regime's strategies in this way, he tends to ignore the pace at which liberalization is pursued, which is considered to be an important factor in democratization in authoritarian countries. Because, as Taagepera and Shugart (1989) point out, exploiting electoral systems is the easiest way for a

regime to manipulate policy, this disagreement about the regime's willingness to allow opposition politicians to take part in political discourse will be important.

Yegim Arat (1998) examines the effect of women on Turkish politics between the late 1980s and the end of the twentieth century, finding greater emphasis on equal rights. She warns, however, that the inheritance of a patriarchal system from the Islamic tradition prevents Turkish feminists from making greater progress in their struggle (Arat 1998). She divides women in politics into two groups: those who organized against domestic violence (feminists) and those who joined the Islamist movement. The feminists fought for equal rights based on the Turkish constitution, while Muslim women fought against the secular foundation of the Turkish state to be permitted to identify themselves as Muslim (through the use of headscarves, for example). Both groups' successes were fairly limited, and Arat (1998) does not predict the future of women's rights in Turkey, but instead examines these groups from a historical point of view.

Hussain Haqqani (2003) examines the impact of the current war in Iraq on Turkey, Pakistan, and Indonesia, three non-Arab Muslim-majority states. Turkish opposition to the war has two foundations: Islamic solidarity against the U.S. and fears of Turkish Kurds demands growing in response to a federal Iraq. He warns that U.S. failure could lead to pressure on Prime Minister Erdogan to pursue more Islamist policies (which could lead to another military

intervention in Turkey's democracy) (Haqqani 2003).

Several studies note Turkey's 10% threshold as a significant barrier to gaining

representation in the Grand National Assembly (see Cosar and Ozman 2004, Yavus 1997, Bacik 2004), but do not take the next step in examining the effect of this threshold on representation levels. Esmer and Sayari calculate vote-seat disproportionality with a variety of different

formulas, but only use the results for parties successful in winning seats to perform their calculations (Esmer and Sayari 2002).

The study of political reform in Jordan focuses on several areas: the impact of reform and elections on the Palestinian population, the Hashemite motivations of democratization and electoral reform, and the role of political parties in Jordan. Oftentimes in these studies, scholars overstate the role of political parties in Jordanian politics- it is the tribes, not the political parties, who garner the strength and power in the system. In addition, it is difficult to speculate on the motivations of the Hashemite regime in pursuing political reform. Scholars spend much of their time predicting the motivations of political elites, which is difficult, while the study of the effect of electoral reform in Jordan is under explored. Indeed, an in-depth study on the effect of electoral reform, a truly measurable variable, would provide insight into not only the dynamics of electoral reform in Jordan specifically, but would also indicate trends in democratization in authoritarian regimes.

In many established democracies, systematic studies of the transformation of votes into seats, whether by examining apportionment (the distribution of all seats) or proportionality (votes for parties translating into representation), have led to more in-depth research on median voter theory, the impact of citizen opinion on bills and legislators' votes, and general legislature functionality. In Jordan's case, however, a systematic analysis of malapportionment does not exist, and severe data limitations prevent these more specific studies. For example, there is no public record of the roll call vote of members of the House of Deputies, on any issue. For

Turkey, on the other hand, individual studies on specific elections and issues, citizen vote choice, as well as the rise of Islamist parties, have dominated the study of Turkey's elections.

By examining the individual experiences of electoral reform in Turkey and Jordan, this study provides important case studies on the effects of specific election mechanisms. A great deal of past work on electoral systems is multiple country studies to compare and contrast broad questions of electoral design. What is lacking is explaining how votes are mechanically

converted into seats (or not), especially in cases where there is direct manipulation. With these two case studies specifically, the literature widely acknowledges the effect of mechanisms for control, but to my knowledge does not examine their effects on representation.

Representation- The Missing Story

The literature surrounding Jordan's electoral reform seems to be silent on two specific areas: explanation of the variation in turnout rates in the rural and urban areas and an analysis of representation. Lust-Okar (2007), Posusney (1998) and others claim that the Jordanian system does not produce a representative legislature, but their efforts have been limited to focusing on Jordan's shortcomings with respect to its Palestinian population. In addition, Lust-Okar (2007, 2001), Langohr (2001), Schwedler (1998), and Robinson (1997) discuss electoral reforms in a broader discussion of other issues (the Palestinian issue, Islamist political parties, the Hashemite regime's slow democratization). One of the reasons for this is the lack of reliable census, tribal, and religious data for electoral districts, as well as complete election returns. While all of the data is not readily available, there is enough to begin to study the impact of electoral mechanisms on representation.

While Turkey has experimented with a variety of different electoral systems, and has undergone several military coups, one of which rewrote the Constitution and abolished the electoral system and its existing parties completely, several conditions have remained constant.

The focus of the government on maintaining a strict secular treatment of policy and public life has successfully consumed virtually all political debate in the modem Turkish state. Military

coups have served to realign the political system to preempt movements toward a new Turkish identity by those whose interests don't align with Mustafa Kemal's image of Turkey. The Constitutional Court has, since the 1980 military coup, decided the constitutionality of political parties and has banned many from elections.

Authoritarianism and Democracy

It is well understood that authoritarian regimes do usually not preemptively pursue political liberalization. Arab-majority countries, in particular, have begun to move toward democratization after being confronted with citizen protest due to poor economic conditions, government corruption, and human rights abuses (Tessler 2005). While Tessler's (2005) finding is focused on Arab countries, this democratization trend has not only occurred in these countries; states in Latin America, Africa, and Eastern Europe have also pursued liberalization measures. Those initial reforms were mainly used to appease the public and strengthen governmental legitimacy. A principle strategy of liberalization has been, in many cases, to institute elections for legislatures. While images of previously silent publics in places like Jordan and Morocco heading to the polls on Election Day conjures up the image of a "proper" representative government, specific mechanisms built into their systems repress the translation of votes into seats. Jordan, for instance, opted for a rare electoral system to replace its previous system (with first past the post rules but multi-member districts, without the proportionality), in addition to refraining from distributing seats according to population. At the same time, other states with well-established histories with free and fair elections have recently come under scrutiny for

similarly questionable policies. Turkey, for example, has been cited in many studies of electoral mechanisms for its extraordinarily high election threshold and for the intrusion of unelected officials into the system.

Within the literature regarding electoral systems, there are a multitude of topics that address the particularities in Jordan and Turkey. First and foremost is electoral engineering, the concept that by deliberately selecting specific mechanisms based on state characteristics like

economic development, education, social cleavages, and colonial legacy, one can steer a state toward a certain system. In many cases, the "engineering" of systems is meant to give an

impression of deliberate, overt molding of an electoral system to best approach the most salient issues facing a state. Typically the system is "engineered" by state builders, whether they are occupying powers or elected representatives.

Recently, however, this term has come to have a more negative connotation, instead intimating that governing regimes manipulate their electoral systems to maintain their dominance in a state instead of suiting the nation's needs at large. In the cases of democratizing countries, the overt manipulation of electoral mechanisms by the regime has overshadowed the bright prospect to becoming full democracies. For Jordan, manipulation by the ruling regime has maintained overrepresentation of the rural, desert population, while compromising the large urban populations of Amman and Irbid.

At the same time, however, Jordan is arguably the safest and most stable country in the Middle East: it maintains positive and strong relations with the United States, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, while also being the only country to permit and encourage Palestinian

refugees to become citizens. Jordan has no domestic terrorism problems, and with the exception of the 2005 suicide bombings, it has been free of terrorist attacks for many years. In contrast to

states like Egypt, where Islamist politics is repressed, Jordan has a history of Islamist political parties, and the Hashemite monarchy has a productive and overall positive relationship with the Islamic Action Front, the only significant political party in Jordan. Since reestablishing elections

in 1989, the monarchy has altered Jordan's electoral system to a rare single non-transferable voting system.

While the concept of electoral engineering has not been directly applied to Turkey (most studies of electoral engineering cover state building or long-established democracies, and Turkey does not really fit in either of these categories), several preliminary findings imply that there is elite manipulation inherently through electoral mechanisms: the high election threshold, frequent interventions by the military, party banning by the Constitutional Court, and ongoing friction between "free and fair" elections and exclusion of certain policies from political discourse all provide significant evidence of manipulation.

Electoral engineering

Norris (2004) examines the consequences of electoral rules and modernization for political representation and voting. She studies patterns of party competition, social cleavages and party loyalty, turnout levels, and diversity of parliaments, and determines from her study that the formal rules of electoral institutions do matter when it comes to shaping social norms and human behavior. Her study can be extended to studying countries transitioning to democracy. When political elites or authoritarians engineer voting systems to work in their favor, they are forcing elections one way or another.

Pippa Norris' study on electoral engineering presents and analyzes the arguments related to electoral system design. She focuses on the dynamics between political party systems and

electoral systems, and notes that it is not just new democracies that are designing electoral systems to meet a specific need; established democracies like Italy, New Zealand, and Japan have reformed their electoral systems in the last 15 years (Norris 2004). She divides the effects of electoral system design into two categories: mechanical effects (the translation of votes into seats, for example) and psychological effects. Her analysis of electoral engineering is based on two different theories about electoral system design: rational choice and modernization theory; for the purposes of my study, her use of rational choice theory is most useful to me. Rational choice theory, as applied to electoral system design, assumes that formal electoral rules shape the incentives that political actors face, and that political actors seek to maximize their vote share by utilizing electoral incentives inherent in the electoral system (Norris 2004, pp. 7).

Arend Lijphart's (1999) seminal work examines democratic institutions in 36 countries from 1940 to the present. Beginning with a simple definition of the term "democracy," which is "government by and for the people," he next raises the question of "who will do the governing, and to whose interests should the government be responsive when the people are in disagreement and have divergent preferences?" (Lijphart 1999 pp. 1). He focuses on measuring the level to which the institutions are majoritarian or consensual, a contrast that is consistently used to examine democracies. In majoritarian democracies, the answer to the question of "who governs" is simply the majority of the people, while in consensual democracies the response is "as many people as possible" (Lijphart 1999 pp. 2).

Lijphart also breaks down the differences between majoritarian and consensual

democracies into 10 characteristics along the executive-parties dimension and the federal-unity dimension; these characteristics are organized in Table 2-1. The first dimension, executive-parties, provides insight into how the political system is organized; characteristics like the type

of party system, distribution of power among parties, electoral system, and type of system installed for interest groups. The second, federal-unity, explains how centralized the federal government is, and how consolidated individual branches of the government are; the number of houses in the legislature, the degree of constitutional flexibility, level of judicial review, and independence of the central bank.

Table 2-1: Fitting Characteristics of Description Executive-parties Concentration of power Balance of power Party system Majoritarian v. PR Interest group systems Centralization of government Number of houses in legislature Constitution flexibility Judicial review Independence of central bank

Single-party majorities v.Single-party majorities v. multiparty coalitions Dominant executive v. equal power between executive and legislative Two-party v. multiparty systems

First past the post v. proportional representation free-for-all competition v. compromise Federal-unity Unitary centralized v. federal decentralized systems Unicameral v. multicameral (division of power) Amendments by simple majority v. super majority Legislatures get the final word v. courts reviewing the constitutionality of laws Dependent on the executive v. independent central banks

Democratic Systems to Jordan Royal Family, tribal

alliances

Dominant Executives

No organized system Multi member districts with 1 st past the post rules

Tightly controlled civil society

Centralized

Multicameral

Super majority, or by king

King has final word

Independent

Jordan and Turkey Turkey Multiparty coalitions Equal Power Multiparty PR with election threshold

Controlled civil society

Centralized Unicameral 2/3 majority, referendum (proposed by MPs) Constitutional Court Independent

It is unclear from this model whether Turkey's system is a majoritarian or consensual system. With respect to Jordan, it is not by any means a democracy, but the presence of an elected legislature does make this model applicable. Turkey has a proportional representation election system, which is assigned to consensual systems, but the presence of a unicameral

legislature indicates that it is a majoritarian system. The balance of power in Jordan's

government is heavily in favor of the monarch and the upper house of parliament (majoritarian), but multiple parties are permitted to participate in elections (consensual). In Jordan's case, the mere fact that it is a constitutional monarchy with a great deal of power vested in the king is

enough to prevent it from being called a "democracy," but does the presence of elections and signs that the government is liberalizing the system present enough evidence that Jordan is "democratizing"?

Lijphart (1999 pp. 6-8) criticizes those who have focused on identifying only majoritarian systems as democracies, which is the less common of the two types of electoral systems. He argues that consensual systems more closely fit the idea of a democracy than majoritarian systems, and that to exclude consensual democracies from the discussion would retract greatly from the study of representative governments (Lijphart 1999 pp. 31-33). Applying Lijphart's terminology to Turkey and Jordan provides helpful indications on how best to examine each system. Turkey falls best under the consensual democracy model with regard to its legislature, while Jordan falls somewhere in between for the purposes of my study.

Electoral Systems

A study of the relationship between colonial legacy and electoral system shows that most former British colonies and two-thirds of former French colonies now use majoritarian systems, while three-quarters of former Portuguese colonies, two-thirds of former Spanish colonies, and former Dutch colonies use proportional representation (Norris 2004 pp. 59). Former communist countries tend to choose majoritarian systems.

There are a variety of different types of electoral systems, and most break these down into two types: consensual and adversarial (Norris 2004 pp. 69). The first type, consensual democracy, is identified by the presence of an elected legislature whose seats are assigned proportionally with regards to the population. The theory behind consensual democracy is to

maximize electoral choice, fairly translate votes into seats, and to be socially inclusive (Norris 2004 pp. 69). PR systems are preferred in ethnically divided societies, although critiques of PR systems indicate that it may serve to reinforce ethnic cleavages. Majoritarian, or adversarial, systems are typically characterized by winner-take-all elections in single member districts. While in PR systems the goal is for both minorities and majorities to have representation, in majoritarian systems this does not tend to be the case. Lijphart (1999 pp. 143- 144) clearly has a preference for PR systems, as he points out that in majority or plurality systems the winning party is always overrepresented in comparison to the votes it received.

Norris (2004 pp. 51) discusses PR systems, which are considered by most to be consensual systems. Turkey's PR system uses the D'Hondt method for allocating seats in the Grand National Assembly. Through a series of quotients, parties with the highest average vote share, are assigned seats. Since 1983, the 10% national election threshold has posed an additional barrier to parties- only those parties that win 10% of the nationwide votes in the legislative

elections are eligible for seats. After those parties are determined, the seats are then allocated within each electoral district.

Representation

The essence of democratic governance is the concept that citizens choose representatives to act on their behalf. In a true democracy, all citizens are assigned equal power to choose their