Citizen Participation and Its Importance in Determining

New York City Subway Station Capital Improvements

by

Anthony Mannin Ng

Bachelor of Arts, Economics Bates College, 1994

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master in City Planning

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 1998

@ 1998 Anthony Mannin Ng. All Rights Reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

A uthor... ...

DepartmeAtof Urbat'is a Planning y 21, 1998

C ertified by ... ... . Ernesto Cortes, Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Professor ,.Thesis Advisor

Accepted by... Lawrnce .. ... .

Lawrence Bacow Professor of Law and Environmental Policy Chair, MCP Committee

kjI4?

Citizen Participation and Its Importance in Determining

New York City Subway Station Capital Improvements

by

Anthony Mannin Ng

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21, 1998 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of Master in City Planning

ABSTRACT

Due to the disinvestment in the NYC subway system during the 1970s, station conditions deteriorated just like other components of the subway system (e.g. subway cars, tracks). A capital program to reinvest in the system has been in place since 1982 and has restored the

general health of the system considerably. However, the focus of this capital program to date has been on the system's rolling stock and other subway infrastructure, and not so much subway

stations. As station conditions are a component of subway service aside from the subway ride itself and the condition of the subway car, poor station conditions can contribute to notions of a lack in service. A rational, "scientific" process has been designed by New York City Transit (NYCT) to select station rehabilitation projects. This thesis will demonstrate that this process is not as rational as NYCT considers it to be and the existence of such a selection process does not free NYCT from having to be accountable to citizens, local elected officials, and communities. The selection process is actually quite political and citizens can most effectively intervene in this process by understanding it and utilizing the practice of politics to amass citizen power in the form of groups, so as to affect the station rehabilitation projects to be undertaken. A case study of a community organizing effort surrounding the poor conditions of a subway shuttle line's stations, in a Brooklyn, New York community, will be the basis for illustrating this.

Thesis Advisor: Ernesto Cortes, Jr.

Acknowledgements

This thesis could not have been completed without knowing that I had the love, support, and hope of my family: Mom -- I have found much inspiration in the strength you have exhibited these past few years. Dad -- I know that you'll always be there somehow. Benny -- For holding it down back at home these past two years, I know it's been a little tough, but I think brighter days are near. Connie -- My booger head sister, keep your head up and college will be here sooner than you think. Nor could this thesis have been done without the camaraderie of my close friends and roommates, O-Dog, Big Boy aka Little Gil, and Dreds -- 440 YOU KNOW!!!!

I'd also like to thank and acknowledge the following people for their assistance in this endeavor: To Ernie Cortes, for his unfailing ability to provoke my thought about power, politics,

relationships, and interests. Phil Clay, for his diligence as my reader. Analia Penchaszadeh, for her insightful comments on organizing, and her experience with the Franklin Avenue Shuttle. Charles Planck, who gave me a lot of leads and information as I started researching this topic. Julie Wagner, for her contacts surrounding those who are committed to public involvement in transit issues. Tarry Hum, for your encouraging comments on my topic when it was still in its formative stages. Wells Chen, for being there with me at my thesis defense. Joe Rappaport, who provided key contacts, information, and access to his files about the Franklin Avenue Shuttle. Arlene Grauer, for your patience in answering my questions about the New York City Transit station rehabilitation selection process. Jonathan Sigall of PCAC. To those involved in saving the Franklin Avenue Shuttle -- Mable Boston, Connie Hall, Frances Byrd, Mauricia Baca --thank you for reflecting on your efforts with me. For emotional support in the last few days of putting this together, I'd like to thank Camille Tsao, Mona Fawaz, Maria Elosua, and Ketsia Colinet.

And lastly to Rebecca -- We've shared much in the past four and a half years, and while we are not together anymore, let's take this time to strive towards a better understanding of ourselves

Table of Contents

Introduction 5

1 Recent History of the New York City Subway System 11

2 The Social Impacts of the Station Selection System 22

and Its Effects on Issues of Equity

3 Effectiveness of Existing Mechanisms of Citizen Input

in Fostering A More Open Transportation Planning Process 33 4 Politics As A Means To Achieve Greater Citizen Participation 39

5 The Franklin Avenue Shuttle and the Communities of

Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Prospect Heights 50

Conclusion 76

Bibliography 79

Introduction

If someone were to ask a New York City (NYC) native like myself about the role that the

NYC subway system plays in one's daily life, I'd have to respond that its presence is integral.

The subway is used by NYC's residents to get to work, and school; access services; arrive at the

city's major commercial shopping areas and cultural institutions; and to travel throughout the

city to visit friends, and family.1 Not only does the subway help the local economy function and aids in the mobility of its residents, it also serves to instill a sense of tolerance amongst New

Yorkers. A ride on the NYC subway, will expose you to the diverse population of this city,

people of every conceivable race, ethnicity, and class. The need to share such close space for a few minutes a day forces New Yorkers to relate to those who have different backgrounds in a

unique way, even if it is on a cursory level.

The tone of the above description concerning the popular use of the subway system, and

its ancillary role as a social engineering lab probably would not have been as positive if one were

asked to describe the subway system as it emerged out of the 1970s. In the early 1980s, the

NYC subway system was in an utter state of disrepair. Subway fires and derailments were

commonplace, subway cars experienced breakdowns after barely 7,000 miles of service and were

strewn with graffiti, with some pieces serving as testaments to the beauty of this urban artform,

but the majority, being black magic marker tags (aliases) of graffiti writers.2 Subway stations

were antiquated and crumbling and depending on the neighborhood and time of day, not safe places to be.

1 Sixty-three percent of the 1.4 million people that work in Manhattan's central business district arrive by mass transit (Seeley, 1982 in Cohen, 1988: 371). Half of all shopping trips are taken by subway (Sandler, 1986 in Cohen, 1988: 371).

2 Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). MTA Capital Needs & Opportunities, 1992-2011 -published May 25,

The terrible state of the subway system convinced New York State legislators to heed

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Chairman Richard Ravitch's call in November

1980, to implement a capital program to restore the region's mass transit to a state of good repair. 3 In January 1981, the state legislature passed the Transportation Systems Assistance and Financing Act, which created new avenues of financing that would allow the MTA to raise funds

for a prolonged capital program. Two of the more important financing vehicles created by the

act was: 1) the authorization of the MTA to issue revenue bonds and other obligations backed

by the farebox revenues of the NYC subway, bus, and commuter rail system 2) the ability of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (currently known as MTA Bridges and Tunnels) to

borrow money for MTA mass transit projects. Since 1982, the MTA Capital Program has been

involved in making the needed capital improvements to rebuild the subway system and improve

service. Capital improvement projects are planned in five year intervals, which allow for greater

comprehensiveness in terms of the scope of the rebuilding projects and provides a more stable funding environment than if capital plans were approved annually.

The capital program has done much to return the system to respectability and good

service in the past 16 years. By 1990, the NYC subway system had seen marked improvement

-three quarters of the subway cars, were new or overhauled; two-thirds of the track in the subway

system had been replaced; subway cars ran an average of 30,000 miles between breakdowns, which was four times better than in 1982; ninety percent of the subway cars were

air-conditioned, and all were graffiti free.4 As of 1996, distance between breakdowns reached an all-time high of 78,842 miles, thru-put (the percentage of trains that actually pass through a

3 The MTA oversees the management of the New York Metropolitan region's subway, bus, and commuter railroad lines. More information about the structure of the MTA will appear in the pages to follow. Additionally, it should be noted that the MTA's buses and commuter railroads were in poor condition in the early 1980s as well.

station as scheduled) was at 94.7%, subway ridership levels were at 1.108 billion, which

represented the system's highest level since 1972, and was an increase of 1.4% over 1995; 1996 was also the fifth year in a row that ridership increased.

The original mandate of the capital program, which was to rebuild and improve service,

forestall a cycle of neglect by meeting the system's physical needs, and to position the network to meet the region's mobility requirements by the 2 1" century has since been refined to strive

towards the following: 1) the central goal of full restoration of the entire network to a state of

good repair 2) a program of continuing scheduled maintenance and normal replacement of critical elements 3) addressing and eliminating barriers to ridership growth, such as

overcrowding, capacity limitations, cumbersome fare collection, and antiquated stations.6

While its clear that initiatives to improve the subway system's rolling stock (buying new

subway cars and overhauling old ones), replace dilapidated track, update track signals, repair

tunnels, and retain better-equipped maintenance shops, have addressed goals one and two above,

it has only been in the early 1990s where elements of goal three have begun to be addressed (e.g.

installation of electronic fare readers for the transit system's MetroCard automated fare

collection system began in 1994). Based on a 1992 MTA report regarding capital needs and

opportunities for 1992-2011, the MTA has identified subway stations are a top investment

priority. The MTA understands that modernized stations with renovation and repair of original

surfaces, better passenger flow, better lighting and signs, and more secure fare collection areas

will play a big role in maintaining the satisfaction levels of current riders, and help attract new

riders.7 Similarly, New York City Transit's (NYCT) 1989-1991 operating budget proposal

stated "...to attract additional customers, the physical conditions of the stations - the point at

s MTA. 1996 Annual Report. p.22, 28, 30. 6 MTA (1990). Op.cit., p.4.

which we sell our product - must be improved."8 These sentiments are true, as station conditions

as the first of two indicators that a rider will use to gauge the health and service level of the subway system. The second indicator is the condition of the rolling stock and the nature of the

ride to one's destination. Therefore, it is difficult for one to claim that the subway service they

receive is satisfactory if the subway station that is used to access a ride on the transit system is

antiquated, drab, in need of repairs, is unsafe, or has poor lighting and signage.

Indeed, rehabilitating subway stations have not been the primary focus in the capital

programs to date. The poor physical condition of the subway cars and track in the early 1980s,

accounted for much of the poor subway service at the time. This warranted the concentration of

the first two capital programs on rolling stock and trackwork as a first step in rebuilding the

system. While these aspects of the system have gotten better, the majority of the system's stations are still in need of structural repairs, and modernization. Additionally, if the MTA is to

fulfill their task of rebuilding the entire subway system, station rehabilitation will need to be

pursued more vigorously. As of January 1998, only 97 stations were in a state of good repair.

91 stations have been fully rehabilitated, and six stations are brand new ones, which were

included in two line extensions (three on the Archer Avenue line in Queens, and three on the 6 3 rd

Street line from Manhattan to Queens) in the late 1980s.9

With the above in mind, the purpose of this thesis is concerned with looking at what

communities can do to bring about station improvements in a more timely manner. In a very real sense, it is the one aspect of the system that has probably improved the least, and taken the

longest to implement, since the MTA capital program has been in place. As stations have a

7 MTA (1990). Op.cit., p.3 1.

8 MTA Office of the Inspector General. Assessment of the New York City Transit Authority's Station Modernization, Restoration, and Upgrade Programs. Report MTA/IG 89-17, September 22, 1989, p.1.

9 Arlene Grauer, Deputy Director of Planning, Station Programs, NYCT Dept. of Capital Program Management, January

spatial dimension and are located in the neighborhoods of New York City, the selection of those stations that have been rehabilitated or will be rehabilitated is also a reflection of how sensitive

NYCT is to the social impacts of their station rehabilitation decisions. One major social impact is the notion of equity in ensuring that subway stations are in a state of good repair. In order to

ensure that station rehabilitation projects are chosen in an equitable manner, NYCT has a station

selection process that devises rankings of all 468 stations based on criteria such as station

structural conditions and passenger usage.10 Stations are chosen with this formal, "scientific" method. Other less scientific criteria such as whether each borough is receiving a nearly

equivalent amount of station rehabilitation projects, is considered as well, however, the NYCT is

quite mindful of using the rankings as the primary means to select station rehabilitation projects.

If a station has not been included based on the rankings, the consideration of the less scientific

criteria represents a point of intervention that citizens and communities can use to voice their

needs and concerns regarding their neighborhood subway station in an attempt to have it

included in a capital program. Additionally, as this is one point of intervention, are there other

ones that citizens and communities can use to give feedback and suggestions to NYCT about

subway station conditions? The presence of a forum or avenue which citizens can use to voice

their concerns, does not ensure that their input will be heard. This thesis will also examine

whether an understanding of politics, relationships, interests, and power can help citizen

participation be more effective, by building institutions and strengthening existing ones in order to obtain the power to affect decisions regarding which stations are chosen to receive

rehabilitation. Furthermore, is it possible that an organization called the Industrial Areas

Foundation (IAF), which conceives of organizing and power in this manner, have any principles

10 Until the closing of the Dean St. station in Brooklyn, in September, 1995, the NYC subway system consisted of 469

that may be applicable for citizens wishing to insure equity in the station rehabilitation process?

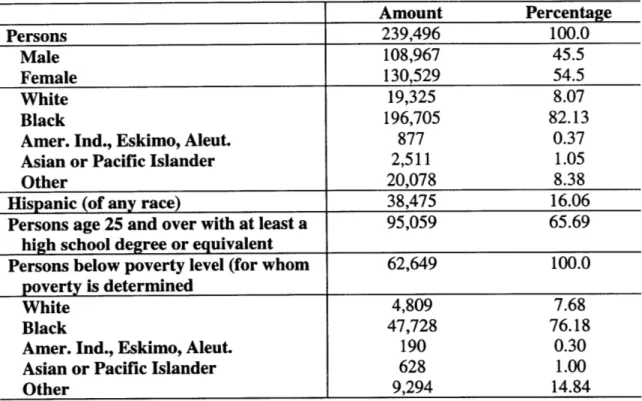

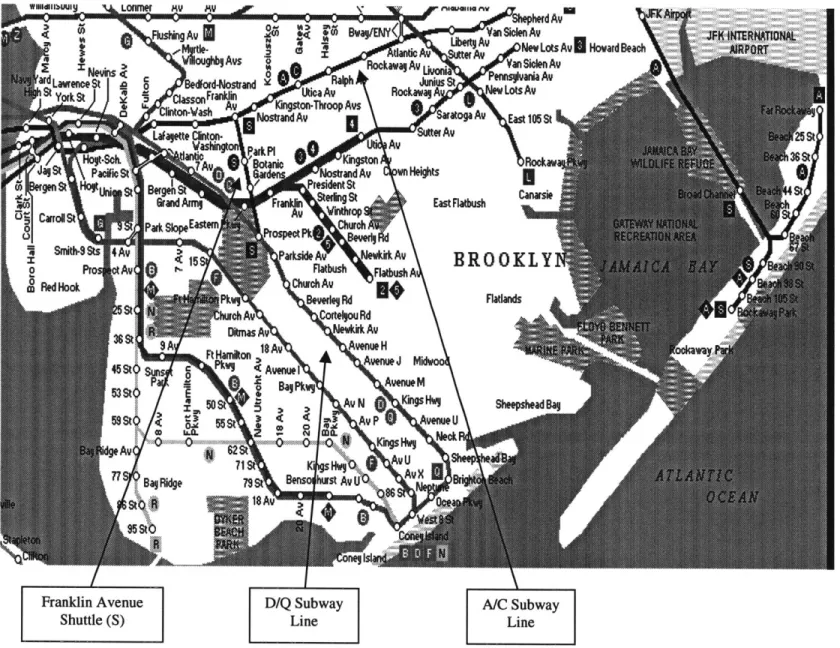

Utilizing a case study of how a predominantly African-American community in Brooklyn, New

York, struggled to obtain improvements for the subway stations of a shuttle line that runs

through their neighborhood, we will learn two things: 1) how power, politics, relationships, and

interests manifested itself in this struggle 2) whether any of IAF's organizing principles were

present or may have been applicable in this struggle.

En route to the case study, this thesis will progress in the following manner -- Chapter

one will provide us with a needed, but brief history of the NYC subway system and the current station rehabilitation selection process. Chapter two will discuss the social impacts of the station

selection process and how equitable it is. Chapter three will discuss the existing mechanisms

that allow citizens to give feedback in to the transit system subway service. Chapter four will

discuss how citizens must understand politics and power if they are to build groups and

institutions with the power to affect public policy decisions. Included in this chapter is a look at

how the IAF aids in the creation of such institutions. Chapter five will include the case study,

1

Recent History of the NYC Subway System

The entity responsible for the day-to-day maintenance and operation of the NYC subways

and buses is the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA). NYCTA is part of the

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the umbrella agency that oversees the respective

agencies that manage the bus, subway, commuter rail lines, and bridges and tunnels, that serve

the New York metropolitan region which includes NYC, Long Island, and several Lower

Hudson Valley counties. Within the MTA, Long Island Railroad (LIRR) and Metro-North

Commuter Railroad (MNCR) manage the metropolitan region's commuter rail lines; Long Island

Bus and MTA Bridges and Tunnels are self-explanatory. Each of these respective agencies can

be thought of as departments (or components) of the MTA. The MTA was created by New York

state legislation in 1965, with the mandate of continuing, developing, and improving public

transportation and to implement a unified public transportation policy in the New York

Metropolitan area." NYCTA solely managed the city's subways from 1954-1967, replacing the

Board of Transportation as the city's subway operator, who had held this role since 1940.

NYCTA officially merged with the MTA in 1968, and technically, is no longer an authority, as it

is the MTA that now has bonding power, and would issue bonds on behalf of NYCTA for any

projects they undertake. Therefore, its official name is MTA New York City Transit (NYCT) or simply NYCT.1 2

According to Cohen (1988), the decline of the system in the 1970s was due to the MTA's

increased emphasis in new subway route construction at the expense of maintaining existing

infrastructure and equipment between the years of 1968-80. Expansion of the system was made

possible during this time period due to increases in federal aid via the Urban Mass

Transportation Act of 1970 (and its subsequent amendments), and increases in state aid due to

the creation of the MTA. In fact, MTA expenditures between 1968-74 averaged $107.1 million

annually, whereas from 1975-1980, annual expenditures averaged $197.4 million (both in current

dollars). The increase in state and federal aid was funneled towards new route construction, and

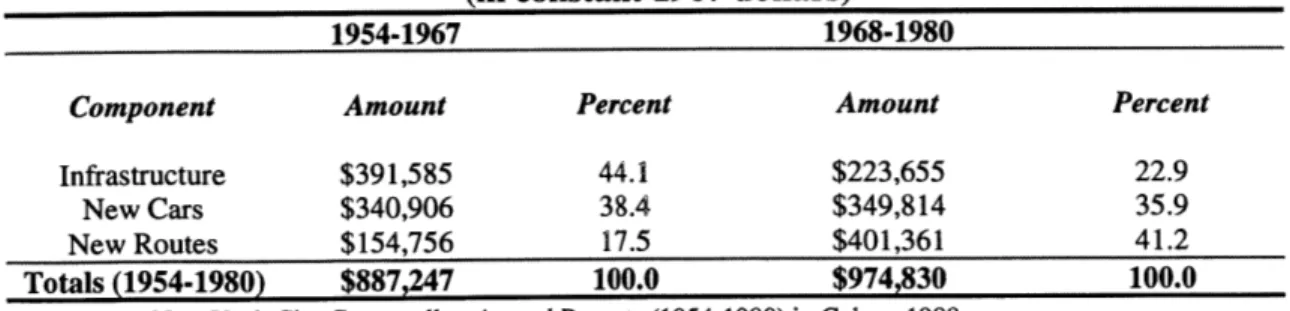

not investment in infrastructure maintenance. A look at the composition of capital expenditures

during NYCTA's management (1954-67) and the MTA's management between 1968-80, reveals

this shift in policy - from 1954-67, 44.1% of the capital budget was spent on infrastructure rehabilitation and renewal, and only 17.5% on new route construction. The remaining 38.4%

was allocated to the purchase of new subway cars. From 1968-80, 22.9% of the capital budget

was spent on modernizing existing infrastructure, 41.2% towards new route construction, and

nearly 36% on fleet renewal (see Table 1).

Table 1 -- Amount and Composition of Subway Capital Expenditures, 1954-1980 (in constant 1967 dollars)

1954-1967 1968-1980

Component Amount Percent Amount Percent

Infrastructure $391,585 44.1 $223,655 22.9

New Cars $340,906 38.4 $349,814 35.9

New Routes $154,756 17.5 $401,361 41.2

Totals (1954-1980) $887,247 100.0 $974,830 100.0

Source: New York City Comptroller, Annual Reports (1954-1980) in Cohen, 1988.

12 I will use MTA NYCT and NYCT interchangeably throughout the rest of the thesis, (after this section's brief

Another factor that made the time ripe for expansion was NYCTA's rebuilding of the

system's capital plant during their tenure as the manager of the NYC subway system. When the MTA incorporated the NYCTA into its operations in 1968, the system was in a state of good

repair, and did not require any major system rehabilitation. This freed up funds to be used for subway expansion efforts.

Cohen also mentions that the city's fiscal crisis of 1975 played a role in the decline of

subway service, but its impact was smaller than most would want to believe. In 1975, several

New York banks refused to finance the city's bonds. As a result, city funds originally earmarked as capital aid for subway improvements, were reallocated to the city's expense budget (e.g.

between 1975-77, this reallocation amounted to $210 million). The city's cuts in subway

funding were largely offset by the increase in state and federal aid, but still impacted NYCT's

operating budget, which ultimately led to the decision to defer maintenance on subway cars, and other infrastructure. This coupled with the fact that most of NYCT's experienced and best

skilled mechanics retired in large numbers in 1968 , explains the decline in service that would

characterize the system until the early 1980s. Additionally, the fiscal crisis was the deathknell

for the MTA's new routes program, as the city could not access capital funds from the bond

market. The fact that two state bond issues -- one each in 1971 and 1973 -- that would have allocated capital aid to the new routes program were defeated, did not help matters either. As a

result, expansion projects such as the Second Ave. line in Manhattan were discontinued.

History of NYCT's Station Rehabilitation Program

The fact that the first two MTA capital programs of the 1980s largely addressed the

The first capital program of 1982-86 called for the modernization of 50 stations at a cost of $227 million (current dollars). Modernization aimed to be comprehensive in its scope of work, and

included structural repairs, architectural work, better lighting and public information provisions, and in some cases improved station layouts.13 In 1983, it proposed adding another 20 stations to

the original list and announced its intention to start modernizing 200 stations by 1993. However,

by the end of 1988, modernization had only begun at 22 stations, and by June 30, 1989, 14 had

been completed. In May of 1989, four stations were dropped from the modernization list to

provide money for implementing MetroCard. In 1989, NYCT estimated that at the rate they were progressing, it would take more than 100 years to modernize the entire system.

Modernizations increased in cost, and were postponed or delayed for a variety of reasons, among them being poor performance by contractors and consultants, and the reluctance of NYCT to

hold them accountable for their mistakes; the use of obsolete (and in some cases, incorrect)

blueprints; unforeseen field conditions, changes in design and construction standards that the NYCT wants applied, and design errors and.14 The average completion delay as of March 1989

was 29 months.

Due to the poor results of the station modernization program, NYCT instituted a station

restoration program in 1987. The scope of work pursued in restoration was the same as

modernization, but did not include structural repairs, as these repairs were deemed to be too

costly and time consuming. Unfortunately, the restoration program ran into similar problems as

the modernization program, which primarily manifested itself in project cost overruns. By the

beginning of 1989, only seven stations out of the original list of thirty to be restored were

completed.

13 MTA Inspector General's Office (1989). Op.cit., p.1.

1 4

To complement the station restoration program, NYCT instituted a station upgrade

program in 1988. The scope of work in this program was the least daunting of the three, and focused on improving the appearance of 25 stations a year by removing abandoned fixtures,

unused wires, and other visual clutter, and by improving signs, advertising, and security; stations

were also painted if necessary.15 By the end of 1988, 25 station upgrades had been completed. The cost overruns and delays in completing station work justified an investigation by the

MTA Office of the Inspector General that was completed in 1989. (The Inspector General is an

autonomous agency within the MTA that is charged with investigating any poor practices in MTA operations and management that it deems worthy of scrutiny.) The negative tone of the

1989 report led NYCT to reconsider the way they rehabilitated stations. One of the major

reasons why costs increased so much in the station programs of the first two capital plans was

the lack of understanding of the true conditions at subway stations, which resulted in inaccurate

scoping of work to be done and poor initial cost estimates.

NYCT's lack of understanding of a station's true conditions manifested itself in the

emergency repair of the Nevins Street station in Brooklyn, which is a major transfer point for the system's 2, 3, 4, and 5 lines. The station was slated to be included in the restoration program for

1992, however, a comprehensive station structural condition survey conducted between late 1988

and October 1989 identified the station as one of 133 system-wide that had major structural

deficiencies, such as steel corrosion and crumbling concrete. In the summer of 1990, an NYCT

engineer who happened to be at the station discovered further structural flaws which required the use 12 x 12 timbers to support the station's sagging mezzanine floor. In September 1990, the

MTA Board approved a $10 million emergency contract to reconstruct the mezzanine floor at

Nevins Street. This crisis crystallized to the MTA, the need to consider structural concerns as

part of a station rehabilitation program, and that simply improving station appearance, which were the focus of the station restoration and upgrade programs, could not be considered adequate

station rehabilitation. Consequently, the first two capital plans were flawed in that they shied

away from the more time-consuming and costly work of structural repair.

As mentioned earlier, NYCT conducted its first comprehensive structural condition

survey of all 469 stations between late 1988 and October 1989 in order to better understand the full scope of work that it needed to perform at stations. The structural condition data was

combined with other criteria to create a balanced selection criteria ranking system that NYCT uses to prioritize which station will be next to receive a full station rehabilitation. Full station

rehabilitation is as comprehensive, and addresses the same concerns as the modernization

program. Recognizing that all stations will not be able to wait until their turn comes up to have

repairs made at their stations, NYCT has programs that specifically address lighting, signage,

communications, etc., in those stations that have deficiencies in these areas. Known as campaign

projects, they help to address station conditions in the interim time between when a station

commences modernization work and while its awaiting its turn. This also helps to decrease the

scope of work that may have to be done at a station when it is time for it to be rehabilitated.

Unless a station has been identified for a full station rehabilitation or campaign work, no

improvements or repairs of any type will be performed in a capital program, which is bound to

concern those stations that have capital improvement needs that arise in between capital

The balanced selection criteria system

1992-96 was the first capital program that used the balanced selection criteria. It was

used to determine the station rehabilitation projects for 1994, as those for 1992 and 1993 were chosen by utilizing other criteria. The balanced selection criteria system consists of a station

ranking system and the subsequent consideration of other more qualitative factors in determining the stations that will be rehabilitated in a capital program. Station rankings are determined by

assigning points to quantitative criteria such as structural conditions, usage (passenger flow),

felonies committed, and other miscellaneous criteria (which includes key stations) of a station.

Table 2 below describes how the points awarded.

Table 2 - Balanced Selection Criteria Point System, NYCT Station Rehabilitation Program

Structural condition: Up to 51 points for the worst condition. Stations receive

a structural rating between 1 and 5 (1 being the best, 5 being the worst). Each rating is equivalent to 10.25 points.

Usage: Up to 25 points for the highest number of customers. Usage includes the turnstile counts for a station and if the station is a transfer point between subway lines, any transfers from one subway line to another.

Felonies: Up to 8 points.

Miscellaneous criteria: Up to 2 points each can be awarded to a station if it

meets some of the following criteria - terminal station on a subway line; part of a transportation complex; an intermodal station; a handicapped accessible station with Americans with Disability Act (ADA) key station designation; AFC (automated fare collection) core station; has secured outside funding or potential developer funding; near a point of interest.

Source: NYCT, Station Selection Policy, Rehabilitation Program, 1993; Arlene Grauer and Janet Jenkins, NYCT Dept. of Capital Program Management.

Once the points are assigned to each station, some further analysis is done to finalize the

list of stations to be rehabilitated. The subsequent qualitative factors that are considered are the availability of funding for the work to be done; whether there are other planned NYCT

construction projects that would advance/delay a station rehabilitation; whether a station is part

of a station complex (if so, all the stations in the complex are rehabilitated at the same time); whether the station can be grouped with other stations on a subway line to be rehabilitated;

geographic distribution -- insuring that a relatively equivalent amount of stations is rehabilitated

in each borough, which is termed borough equity; the strategies needed to address the any

inconvenience that riders will be subjected to. Fifteen to twenty percent of stations chosen by

ranking according to the point system can be changed during this phase when other factors are considered.

The station rankings are compiled by the NYCT Dept. of Capital Program Management

(CPM), and it is CPM that takes the first cut at selecting what stations will be rehabilitated.

While usage figures are updated annually (primarily for information's sake), an actual re-ranking

of the stations based on the balanced selection criteria point system does not occur until NYCT

CPM is selecting the stations to be included in the next capital program. A re-ranking does not

need to occur every year, as passenger usage changes annually, and it's costly to conduct

structural conditions surveys annually. In fact, the structural conditions survey has only been

done once, back in the late 1980s. CPM continues to rely on these ratings, as they still represent

a good baseline assessment of each station and are aware of less structurally sound stations they

need to closely monitor. It's generally rare that criteria other than these two change and affect

the points assigned to a station.

Obtaining approval for the station rehabilitation projects within the MTA Capital Program Once NYCT CPM chooses the stations to be included in the next capital program, it

subway and bus system (e.g. rolling stock, automated fare collection system, trackwork). The

NYCT Capital Program Committee (CPC) which includes the president of the NYCT, approves

and signs off on the agency's portfolio of capital needs and projects. NYCT's list of capital

projects is then submitted to the MTA Board of Directors for review so as to be included in the

MTA capital program. The other agencies that manage the NY metropolitan region's commuter

railroads, bus, and bridges and tunnels, submit their capital needs to the MTA Board for review

as well.

The MTA Board of Directors consists of 17 members, from the government, corporate

and transit worlds of NYC. The Board is selected by the governor of New York state, Mayor of

the City of New York, and executives of the seven outlying New York state counties served by the MTA. There are two non-voting members on the Board -- 1) a representative from the MTA

Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee (PCAC), which provides a voice for users of the MTA

system 2) a representative from labor. Once the MTA approves the capital program, it needs to

be approved at the state level by the Capital Program Review Board (CPRB).

The CPRB was created in 1982 via public authorities law and is in charge of reviewing

and approving the MTA's five year capital plans. The CPRB is also in charge of monitoring the

expenditures made in each year of the capital plans to insure that the projects are being carried

out and completed on schedule and within budget. Performing these two functions help it fulfill

its statute in the public authorities law that dictates that the CPRB insures that the MTA capital

plan addresses the needs of all the communities and areas served by the MTA (NYS public

authorities law, section 1269-B, 15-282). The CPRB consists of four members, all appointed by

the Governor, but with one each coming by recommendation from the temporary president of the

of the City of New York. Two non-voting members are appointed as well, and are based upon

the recommendation of the minority leader of the state senate, and the minority leader of the state assembly. The current makeup of the CPRB is Cathy Nolan, the state assembly representative;

the state senate representative is currently vacant; state transportation commissioner Joseph

Boardman is the governor's own appointee and the NYC Dept. of Transportation commissioner

is generally the NYC mayor's representative. The NYC representative only votes on the portion

of the capital program related to NYC. In order for a capital program to be approved, the CPRB

must vote unanimously in favor of it.

Station Rehabilitation Program Approval Process as Points of Intervention

As the above description of the MTA capital program approval process illustrates, the

station rehabilitation program is "competing" for funding against other projects within NYCT

and with projects from the other MTA agencies. Essentially, the station rehabilitation element of

a MTA capital plan undergoes four levels of approval -- NYCT CPM, NYCT CPC, the MTA

Board of Directors, and the CPRB. Approval of the overall MTA capital plan implies approval

of the station rehabilitation projects, as this element is embedded in the MTA capital plan. (For

the remainder of the this thesis, we will continue to refer to it separately as the station

rehabilitation capital program/project approval process keeping in mind that it's embedded in the

approval of the overall MTA capital plan).

Each approval level can be considered as a point of intervention where citizens can

intervene to make claims for subway station improvements not included in a capital program. As

each level is cumulatively accountable to the one above them, each in turn holds greater power

the CPRB holding the greatest power in such decisions. While no direct accountability measures

(e.g. public hearings) to the public exist at each of these approval levels, theoretically, citizens looking to affect the list of station rehabilitation projects in a capital program can amass

themselves in a group and choose the approval level where they would intervene. The level at which to intervene depends on what stage of capital program formation the MTA is in. Other

considerations would be whether it is better to get in at the first approval level (NYCT CPM), or

directly contact the two levels that have greatest power, the MTA Board or the CPRB. This

latter consideration is tied to the nature of the subway station improvement desired - the greater the resistance to include it, the higher up the decisionmaking ladder one needs to go.

Recognition of this process and the power that each entity has in shaping the station

rehabilitation program (and other aspects of a capital program) is important if transit riders and

communities want to affect subway station capital investment decisions which impact the level

2

The Social Impacts of the Station Selection System and

its Effect on Issues of Equity

In devising the balanced selection criteria ranking system, NYCT greatly operationalized

and made their station selection process more rational. The rankings strive to be as scientific as

possible in the criteria it uses to assign points, yet some flexibility still exists to account for

things not easily quantifiable. The question that arises is whether such a selection process is fair as there is always the chance that a station can be included or removed from the capital program

despite its ranking. In the best case scenario, one can consider this as being attentive to

unexpected circumstances that may arise; in the worst case scenario, the flexibility of the

selection process can be abused, resulting in an inequitable outcome.

Interestingly enough, the flexibility of the process is not the only aspect that may lead

to inequities. Usage criteria and structural condition are heavily weighted in the ranking

process. This emphasis will undoubtedly choose older stations and those that are the most

used, the majority of which are in midtown and lower Manhattan, the two central business

districts of NYC.16 Even some of the miscellaneous criteria may ultimately end up favoring

stations in Manhattan, rather than those in the outer boroughs, as points of interest and the availability of developer funding are two that are more difficult to find in NYC's outer

boroughs.17 According to the balanced selection criteria point system alone , this would be

deemed a fair outcome, as the criteria have been properly applied. However CPM

understands that utilizing the rankings alone would lead to inequities of this sort, and upset the elected officials that represent those parts of the city where few stations were selected.'8

Not only would the elected officials of these neighborhoods be upset, but it's likely and

possible that residents, community groups, subway users, merchants, and institutions of the

same neighborhoods would express discontent as well. As there are all these competing

interests who have a stake in the rehabilitation of a neighborhood's subway station (and other

transportation policies for that matter), it becomes clear that:

"Transportation policy decisions become reflections of political power and products of complex political interactions aiming to achieve consensus among diverse interest groups. What may seem irrational or unfair according to one perspective can usually be explained as the result of a political process that had to recognize and respect other perspectives as well."19

Indeed, the fact that the station selection process looks at factors (e.g. availability of

funding for the work to be done; whether there are other planned NYCT construction projects

that would advance/delay a station rehabilitation; borough equity issues, etc.) outside of

simply the rankings is a testament to the NYCT's understanding of the political nature of

transportation policy decisions. One can view this as their responsiveness to the transit users

of the system as they have institutionalized and embedded the consideration of these factors in

their station selection procedures. This eliminates the time, cost, and loss of legitimacy as a

"7 Due to time constraints, I was not able to verify the definition with NYCT officials, yet I suspect the points of interest that the NYCT refer to are most probably based in Manhattan, and are of the tourist trap kind. As such, Manhattan stations will gain more points in the points of interest categories than outer borough stations.

18 Janet Jenkins. Janet also stated that when CPM devises their list of station rehabilitation projects, it does not discriminate against a station that has low ridership. For example, a station that has high ridership, and a structural rating of 3, does not necessarily get the nod ahead of a station with lower ridership and a structural rating of 4, as the latter station is a greater threat to public safety than the former.

transit agency that would surely arise if the diverse stakeholders of station rehabilitation

projects had to ask that these factors were reviewed each time a station was considered for

selection.

Reconciling the interests of diverse groups is a complex political process, which takes on

an added dimension of complexity when the group making the claim is of an ethnic and or racial minority and is low-income as well. Due to the systematic discrimination that has occurred in

this country against minorities, the issue of equity for these groups increases exponentially over

those who are non-minorities. Additionally, low-income minorities (and transportation

disadvantaged individuals - e.g. the disabled) disproportionately depend on transit for their urban

mobility.20 Therefore the simplest indicator of equity that is applied to racial minorities accounts for the quality of the infrastructure and service used by transit authorities in serving communities

of color compared with mostly white neighborhoods.

The indicator of equity described above falls under the rubric of service equity, which

considers what it means to have poor service. Transportation is an unusual public service in

that it is not consumed simply for its own sake, but its value depends primarily on how well it

provides access to other places.2 2 When one claims that they are getting poor service, are they

expressing their discontent about the quality and conditions of existing transit service, or are

they lamenting about the lack of existence of transit services at all? The latter scenario could

be the definition of poor service if one is living on the periphery of an urban area that is not

served by any type of mass transit, thereby making it difficult to get anywhere without an

19 Martin Wachs in Susan Hanson (editor). The Geography of Urban Transportation. New York: The Guilford Press, 2nd edition, p.270.

20 David C. Hodge in Susan Hanson (editor). The Geography of Urban Transportation. New York: The Guilford

Press, 2"d edition, p.370.

21 Ibid., p.371.

22Ibid.,

automobile. Measuring equity by quality of service implies that all are entitled to the same

levels of service regardless of the cost in providing that level of service.

Equity can also be measured using criteria that will discuss fiscal equity and financing

equity. Fiscal equity examines how fares are used to support operating expenses. Scrutiny

surrounds something called a user cross-subsidy, which is determined by calculating the

difference between the actual proportion of the cost of a trip paid by the fare and the average system proportion.2 3 If one is paying more than the system average, they are subsidizing

others who are paying a smaller proportion of their share of the operating costs. For example, let's say that the operating cost per mile of a subway ride in City X was $1.50. The fare is

$1.00, and in City X, 30% of the fare supports operating expenses, which makes the system

proportion 30 cents. Someone rides the train for half a mile, which amounts to an operating

cost of 75 cents. This rider has paid 45 cents (75-30) more than the system proportion, and is

subsidizing someone's ride that costs less than the system proportion of 30 cents. Policies

that have been put in place to address user cross-subsidy inequities are fare zones, and higher

fares for travel during peak hours. According to Hodge (1993), fiscal equity also looks at

how capital expenditures are allocated or declined, which in turn affect the existence, quality,

and or service that is provided or not.

Financing equity refers to what taxes are being used to help finance (subsidize) urban

transportation infrastructure and by implication, reveals who is "supporting" this public

transportation. Some taxes are user-oriented, such as a gas tax and motor vehicle excise tax,

and other taxes have no direct relationship to transportation, such as income, sales, and

property tax. Essentially, financing equity examines who is paying for public transportation,

and the impact of the taxes on the proportion of their income that is going towards supporting public transportation.

Despite the discussion about the three different measures of equity, the remainder of this thesis will focus on subway service issues and capital investment decisions as the

measures of equity. These two measures of equity are interrelated, as the lack of capital

investment impacts service levels. While our discussion in the previous section included

capital expenditures under fiscal equity, I have chosen to separate it for clarity's sake. In order

to illustrate the political nature of transportation decisions, the issue of equity with respect to

minority communities, and the difficulties that arise when a capital need surfaces between

capital programs, the next section in this chapter discusses how a station improvement

decision was made at the Grand Street station in Chinatown, Manhattan.

Grand Street Station

Located in Manhattan's Chinatown, this station experiences intense overcrowding. The

station only has two stairwells that are two people wide that allow users to ascend and descend to

the station below. Grand Street station has the 17t highest turnstile count during the week,

serving more than 17,000 riders each weekday, and the 9th highest turnstile count on the

weekends.24 This is rare, as turnstile counts for stations tend to be higher during the workweek

as opposed to the weekend. Additionally, the passenger flow within the station is impeded due

to the location of the token booth. During rush hours, lines for the token booth often back up

towards the entrance/exit of the station making it difficult to leave or enter the station. The

24Ellen Chen, Executive Director, Manhattan Neighborhood Renaissance Local Development Corporation; Jon R. Sorenson, "Green Light for $12B Transit Budget." New York Daily News. July 11, 1997.

overcrowding becomes more treacherous during inclement weather, when rain, ice, sleet, or

snow increases the chance that one may slip and fall when using the stairs.

In the spring of 1997, City Councilwoman Kathryn Freed, whose district includes

Chinatown, and members of some of Chinatown's community groups testified at an MTA Board

of Directors meeting about the conditions at Grand Street station. Freed and the community

members were told that the MTA had no money to add another stairwell, and that the population

boom and expansion of Chinatown is only temporary - once this ends, the overcrowding will

lessen.25 The was an unrealistic assumption, as Chinatown will always serve to be a social,

cultural, and economic destination for Chinese from all over NYC and the NY metropolitan

region. In fact, the D/Q subway line that serves Grand Street station is used by many Chinese who live in Brooklyn to get to Manhattan's Chinatown. Couple this with the many non-Chinese

that visit the neighborhood as well, and it ensures that Grand Street station will continue to be a

popular stop on the D/Q line for the foreseeable future. Therefore, there is little chance that turnstile counts will decrease.

Due to circumstances that will be explained later in this thesis, the CPRB was still in the

midst of approving the 1995-99 MTA capital program last spring as well. As Kathryn Freed is

one of the more powerful members of the city council, she managed to get State Assembly

Speaker Sheldon Silver, whose assembly district also includes Chinatown, involved in the

struggle to obtain a new stairwell for Grand Street station. Silver used his power as the state assembly speaker to say that he would urge the NY State Assembly to not approve the financing

for the 1995-99 capital program if it did not have a provision for adding a new stairwell to the

Grand Street station. No sooner did Silver utter these words, did the MTA manage to find $5

two existing stairwells. Once the Grand Street provision was included, the CPRB approved the

MTA's 1995-99 capital program in July 1997, which cleared the way for the state senate to

approve the financing need to back the capital program. Work on adding the new stairwell is slated to begin this summer, and will take a year to year and a half to complete.

This case is important, as it highlights the political nature of subway station

improvement decisions in NYC. If citizens, and or community groups can gain access to the

elected officials who are among the power brokers of the NYC transit world, it's likely that

the citizens will have an impact on a decision that is favorable to them. From Sheldon Silver,

to Kathryn Freed, to some of Chinatown's community groups, to the CPRB - one thing was apparent - each entity understood their relationships with each other, and possessed a strong

sense of their respective power and interests as well. This understanding made the

intervention at the two station rehabilitation program approval levels - MTA Board of

Directors and CPRB - more effective in obtaining a station improvement decision.

The ability to intervene at two of the station rehabilitation program approval levels I

discussed earlier, with the use of politics, has major implications for those communities that

want subway station improvements and rehabilitation, yet are not included in a capital

program. The Grand Street case is a perfect illustration of the difficulties presented to NYCT

when a capital need which arises in between capital programs, or while one was being

formulated, presents to NYCT. An implication of this is that the station rehabilitation

selection criteria is incomplete, as it was not able to identify the safety hazard at Grand Street

that was brought on by poor subway station conditions. As this is the case, can a more open

transportation planning process, that includes citizen input concerning station conditions be

better incorporated into the station selection process, so that station projects that are chosen

and designed for a capital plan truly represent an attempt to attain equitable levels of service

for all communities, especially communities of color? As citizen input was expressed via the

political power and organization of a few community groups in the Grand Street station case, are there other more formal, existing mechanisms of citizen input that exist?

Can more open transportation planning help address service inequities raised by poor subway station conditions?

What occurred in the Grand Street station was not only a display of how power, politics,

interests, and relationships, operates, but fragments of an open transportation planning process in

action, as local elected officials sided with the community they represented to obtain a needed

subway station improvement.

Subway station improvement decisions, and by implication, transportation planning,

stresses the importance of greater public involvement of those affected by plans as much as

other aspects of contemporary planning (U.S. Dept. of Transportation, 1996; Flyvbjerg,

1983). A transportation planning process that is more open aims to involve the public who will be most affected by a plan. 2 6 While this openness relies heavily on citizens, it also

includes public officials, political parties, interest groups, or the specific target population of a

program (i.e. the users); essentially transportation planning involves more than just

transportation planners.2 7 The primary value of input from citizens and other

non-transportation planners lies in the fact that it can make the process of arriving at non-transportation

planning decisions more democratic. In addition:

26 Flybjerg, 1983, defines open planning in three ways -- greater public involvement of those affected by plans;

greater openness to other types of planning; greater openness towards the effects of planning on general societal development (e.g. impacts on real income, energy policy, social values). Open planning is used in my thesis to refer to greater public involvement.

"The purpose of citizen participation is to see that the decisions of government reflect the preferences of the people. The basic intention of citizen

participation is to insure the responsiveness and accountability of government to the citizens. Secondary reasons for citizen participation are - it helps create better plans, it increases the likelihood of implementing the plan, and it

generates support for the agency.2 8

A more open transportation planning process helps to break down the expert/non-expert

dichotomy that is prevalent in transportation planning, as the technical data that can be

utilized to make decisions can be endless. Shattering this dichotomy is important in assisting a move away from a purely rational/economic perspective of transportation planning, which

values experts and top-down planning, towards transportation planning that is bottom-up, and

gives more emphasis to social impacts and equity issues. The rational/economic method of

transportation planning can't account for everything, which makes the inclusion of citizen

input potentially worthwhile, as they may be able to provide information based on their point

of view as a transit user and not a transit agency. Therefore, more information will result in plans that truly attend to ridership needs. Consideration of these factors allows for

accountability more so than the delivery of mass transit services based solely on rational

economic precepts such as revenue generated, and operating costs.

Ultimately though, a more open process that incorporates greater citizen input is a

reflection of citizen power, and according to Arnstein:

"is the means by which they (have-not citizens) can induce significant social reform which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society."29

27 Bent Flyvbjerg. Citizen Participation and Openness in Transportation Planning. Proceedings of the World Conference on Transport Research, Hamburg 1983, Vol. I, p.5.

28 D. Jordan in Flyvbjerg (1983), p.7.

29 S.R. Arnstein in Bent Flyvbjerg, 1983, p.4 .

As witnessed in the 1970s, citizens amassed such power in cities such as Boston and

NYC to stop the construction of major highways through inner city neighborhoods

(Gakenheimer, 1976; Moss, 1989) and halted the construction of highways that would have torn

up communities and forever altered the physical, social, and economic landscapes of these two cities.

The Grand Street station case and our discussion about the balanced selection criteria

station selection process illustrate two points of intervention that currently exist that allow those

other than transportation planners to be in the process of determining station improvement

decisions. One point of intervention is within the balanced station selection process, where an

individual, group, or community can intervene if their station is not included in the list of stations to be rehabilitated in a capital program by appealing to the portion of the selection process that

looks at more qualitative criteria. Yet the window of opportunity to intervene at this juncture is

limited in the sense that once NYCT CPC has approved their list of capital projects, it is up to the

MTA Board of Directors to approve NYCT's capital program. Those in the Grand Street case

utilized the second point of intervention, which are the different station rehabilitation project

approval levels, and had to intervene at the MTA Board of Directors approval level and the

CPRB approval level as they missed intervening at the initial NYCT CPM level, as the capital

need at Grand Street station arose in between the formation of the 1992-96 capital program and

the 1995-99 capital program.

As we have identified two points of intervention in the station rehabilitation selection

process where non-transportation planners can enter into the planning process, our next chapter, will examine the existing mechanisms of NYCT citizen input, and determine whether they are

use in its capital planning decisions as input from citizens via the points of intervention. It is

important to consider these existing mechanisms, as not every community has the access to

power via local elected officials, nor the social capital in the form of strong community groups and leaders, to affect station improvement decisions in the manner apparent with Grand Street

station. For the communities without such access to power, or social capital, the effectiveness of these mechanisms may be their primary means to insure equitable subway service and station

3

Effectiveness of Existing Mechanisms of Citizen Input

in Fostering a More Open Transportation Planning

Process

Existing mechanisms of citizen input

As fragments of a more open planning system were exhibited in Grand Street, could

what was achieved, been achieved if NYCT's mechanisms of soliciting citizen input were

utilized? If so, the manner in which citizen input was expressed may have been an inefficient

way to obtain a subway station capital improvement. If the existing mechanisms of citizen

input can foster a more open transportation planning process and use citizen input as an aid in

subway station rehabilitation project selection and design decisions, this will negate the need

for a community to expend precious political and social capital to obtain an equitable level of

service that they should be provided with as fare-paying transit riders. If these mechanisms

can't effectively foster more openness, our Grand Street case may be the "model" for obtaining station improvements that the NYCT fails to identify through their own capital

planning procedures. The NYCT mechanisms of citizen input that allow riders to provide

information, suggestions regarding service improvements, and any other feedback regarding

any aspect of subway service are as follows: NYCT Office of Government and Community

Relations (OGCR); MTA OGCR; the NY Transit Rider's Council which is part of the larger

MTA Permanent Citizen's Advisory Committee (PCAC), which also includes the Long Island

Customer Service; public hearings and MTA Board meetings; and outreach that occurs as part

of the final scope and design phase of a station rehabilitation project; transit advocacy groups like the Straphanger's Campaign.

NYCT OGCR: NYCT OGCR is essentially the "public relations arm" of NYCT and represents the

agency line (viewpoint) on all NYCT-related transit issues. It publicizes information about current NYCT initiatives, fare programs, route, service change, and repair information. NYCT OGCR has a staff of 10, with five acting as borough representatives. The OGCR is charged with dealing with elected officials, organized groups, and community boards. When subway and or bus riders have

an issue of concern regarding transit service in their neighborhood, OGCR is in charge of arranging a meeting between the local community board and appropriate transit officials to discuss these issues. OGCR's remaining roles include 1) setting up neighborhood task forces to monitor the progress and any inconveniences associated with large capital projects 2) performing the

community outreach needed to elicit suggestions over the work to be performed in the final scope and design phase of a neighborhood's station rehabilitation project.

MTA OGCR: The MTA OGCR works with elected officials at the city and state level to lobby for

legislation that will be favorable to the MTA. Such legislation could include appropriation bills, and public transportation regulations. In addition, it funnels correspondence it receives concerning the service of the MTA system to the appropriate MTA agency. The MTA OGCR is staffed by five people.

MTA Permanent Citizen's Advisory Committee (PCAC), NYC Transit Rider's Council: The

NYC Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) is part of the larger MTA PCAC, which was created by state legislation in 1981. The PCAC was originally formed in 1977 by the MTA Board of Directors, and consisted of 29 members. PCAC sought state enabling legislation in order to assure their autonomy. The legislation also mandated the creation of the two other commuter councils, who represent the interests of LIRR and Metro North riders. Collectively, the three rider councils make up the PCAC, whose role it is to be the voice of the users of MTA facilities, provide the MTA Board with suggestions on transportation policy, and to hold the MTA Board and senior management accountable to MTA riders. The PCAC has 35 members, with 15 coming from the NYCTRC, and

10 each from the LIRR and Metro North commuter councils. It receives an annual budget from the MTA to support its five-person staff and expenses. The composition of the NYCTRC consists of five members recommended by the Mayor of the City of New York, 5 by the NYC Public Advocate, and one each from the five borough presidents of NYC. Accountability is engendered when PCAC and NYCTRC offers its stance on transit issues at NYCT public hearings and MTA Board meetings,

and by its presence on the MTA Board of Directors as a non-voting member since 1995. The Transit Rider's Council also has monthly public meetings, and quarterly meetings with the

President of NYCT, who is currently Lawrence G. Reuter. PCAC and NYCTRC act as transit rider advocates when it produces position papers, and organizes public forums regarding NYC transit issues.

NYCT Customer Service: With a staff of eleven, NYCT Customer Service takes on the task of

responding to every letter and phone call it receives from an individual, concerning transit service provided by NYCT. (Letters from a group go to NYCT OGCR). In March, 1998, NYCT received 2,488 letters and phone calls, 1,514 of which are closed (been answered), and 974 are pending.34 The correspondence they receive include some about policy issues, service levels, or

commendation of transit workers. For March 1998, 48% consisted of transit delay verification for 30 Peggy Milstone, Manager of Correspondence Unit, NYCT Customer Service, 4/28/98. Peggy also noted that the