HAL Id: tel-01668404

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01668404

Submitted on 20 Dec 2017HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Les structures spatiales de l’Inde au temps de la

globalisation : une approche inductive à partir de

données

Joan Perez

To cite this version:

Joan Perez. Les structures spatiales de l’Inde au temps de la globalisation : une approche inductive à partir de données. Histoire. Université d’Avignon, 2015. Français. �NNT : 2015AVIG1151�. �tel-01668404�

M. Giovanni FUSCO, Chargé de recherche CNRS, UMR Espace, Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis Codirecteur

M. Jean GREBERT, Expert, DE-IRM, Renault, Paris Examinateur

M. Jean-Paul HUBERT, Directeur de recherche, IFSTTAR, AME-DEST, Champs-sur-Marne Rapporteur M. François MORICONI-EBRARD, Directeur de recherche CNRS, UMR Espace, Université d’Avignon Codirecteur M. Sébastien OLIVEAU, Maître de conférences HDR, UMR Espace, Aix-Marseille Université Examinateur M. Joel RUET, Chargé de recherche CNRS, CEPN, Université Paris Nord

Rapporteur M. Jean-Claude THILL, Knight Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina, Charlotte Examinateur Composition du jury

Spatial Structures in India

in the Age of Globalisation

A Data-Driven Approach

ACADÉMIE D’AIX-MARSEILLE

UNIVERSITÉ d’AVIGNON

ET DES PAYS DE VAUCLUSE

UFR ip Sciences Humaines et Sociales

Département de Géographie

THÈSE

présentée par Joan PEREZ

pour l’obtention du titre de Docteur en Géographie

de l’Université d’Avignon et des Pays de Vaucluse

École Doctorale 537 « Culture et Patrimoine »

soutenue publiquement le 17 décembre 2015

ii

Remerciements

Je tiens à adresser en premier lieu, de sincères remerciements à Monsieur Giovanni Fusco, pour son suivi constant et sa rigueur notamment en matière de conceptualisation et de modélisation spatiale. Ses exigences m'ont permis de progresser considérablement et ont indubitablement élevé la qualité de ce travail de recherche. Dans un même mouvement, je remercie Monsieur François Moriconi-Ebrard, pour sa vision transversale, sa prise de recul et son regard critique. Ses nombreuses connaissances sur les systèmes de peuplements m'ont permis, dès le début de cette thèse, d'adopter une perspective globale et élargie sur les enjeux de ce travail. Je remercie également l'entreprise Renault, qui, au travers d'une convention CIFRE, a financé ce travail de recherche dans son intégralité.

Ma gratitude va plus particulièrement à Monsieur Jean Grebert, qui, d'un point de vue opérationnel, a piloté cette thèse et son évolution dans l'entreprise. Nombre de nos voyages, missions et échanges trouvent leurs échos dans ce manuscrit. J'espère sincèrement, qu'au delà de cette thèse, d'autres opportunités de collaboration se dessineront.

Au sein de la société Renault, j'exprime aussi toute ma gratitude à Mme. Armelle Guerrin ancienne directrice du plan de Renault India et à M. Marc Nassif, ancien directeur de Renault India, pour nos nombreux échanges, lors de réunions à Chennai, sur le potentiel de marché des pays émergents. J'associe à ces remerciements M. Jean-Marc David, directeur du service DE-IRM, Mme Dominique Levant, directrice de la DREAM Renault ; ainsi que à Mme Pascale Perron et à Mme Michelle Godefroid pour leur aide dans les méandres administratifs de l'entreprise.

J'adresse un remerciement tout particulier à Monsieur Jean-Paul Hubert, Monsieur Sébastien Oliveau, Monsieur Joël Ruet et Monsieur Jean-Claude Thill pour l'intérêt qu'ils portent à l'égard de mon travail, leur disponibilité et ainsi, leur participation à mon jury de thèse.

Je remercie bien sûr l'ensemble des membres de mon laboratoire, l'UMR 7300 Espace, et plus spécifiquement : M. Loïc Grasland, directeur de l'antenne d'Avignon et Mme Nathalie Brachet responsable de publication, pour leur soutien logistique tout au long de ces années.

L'Institut Français de Pondichéry m'a ouvert ses portes durant la première année de ce travail de recherche où j'ai rejoint le département de sciences sociales. Je remercie bien sûr l'ensemble du personnel de l'IFP pour leur accueil chaleureux mais aussi plus particulièrement Mme Kamala Marius-Gnanou, M. Eric Denis et bien sûr Venkatasubramanian pour nos échanges fructueux sur l'Inde et sur mes terrains. Enfin, un grand merci à Antony pour ces nombreux jours (voir nuits !) passés ensemble à traiter les données du recensement Indien.

J'aimerais aussi adresser une reconnaissance toute particulière à mon ancien directeur de mémoire, M. Frédéric Audard, mais aussi à M. Sébastien Oliveau et à feu M. Jean-Luc Bonnefoy. Ces derniers m'ont finalement donné goût à la géographie quantitative bien avant le début de cette thèse.

Je me dois de remercier profondément les membres de ma famille pour leur soutien immuable. Tout d'abord mes parents, Linda et Alain, qui, en toute objectivité sont à l'origine de ce travail il y a maintenant 29 ans de cela. Je remercie aussi l'ensemble de mes proches et notamment Kévin, Micheline et Marco.

Merci aux chercheurs et doctorants rencontrés en France et à l'étranger avec qui j'ai passé de nombreux moments inoubliables : Mythri Prasad, Jules Morel, Cyril Pivano, Salima El Mokthari, Davayani Khare, Selma Fortin, Ravi Kiran, Lizhu Dhai, Léa Wester, Marion Borderon, Joel Quiercy, Yoan Doignon, Julien Bordagi, Romain Ronceray, Elfie Swerts, Akil Amirali, Rémi de Bercegol, Gaelle Lesteven et Charlotte Carlota.

Merci à mon ami Brussais pour le travail d'orfèvre qu'il a réalisé pour la couverture de cette thèse, et, je remercie chaleureusement Eléanore et Marie pour les longues heures qu'elles ont consacrées à relire la langue de Shakespeare.

Merci à tous ceux que je ne prends pas le temps de citer ici car la liste serait trop longue : amis, colocataires... Pour finir, j'adresse un remerciement tout particulier à toi, Amaga, qui m'as soutenu dans toutes ces épreuves, du début à la fin sans jamais fléchir.

iii

Abstract

Countries that have experienced a delayed entry within the world economy have usually sustained an enhanced and faster globalisation process. This is the case for BRIC countries which are, compared to other emerging countries, organised on large economies and thus provide a stronger potential market. From this perspective, India appears to be the perfect case study with an economic growth expected to overcome China's growth in the near future. However, the "clichés" are persistent within a country mostly depicted as bipolar. On the one hand, it is considered as a new eldorado, the "Shining India", a place where multinationals aim to implement themselves due to the substantial increase of the consumer market. At the same time, India is also characterised by overcrowding, the major presence of slum areas and mass poverty, both in urban and rural areas. It is indeed possible that some areas will accommodate a bigger and bigger share of the growing middle class, while others will accentuate economic and social inequalities. Yet, can these extremes be truly representative of the diversity of such a large country? In fact, in some urban oriented spaces, the evolution of the tertiary sector is not strong enough to maintain a high level of employment while in rural spaces; an intensive farming model contributes to gradually reducing the number of labourers and landowners. As a result, the increase of the standard of living related to both economic and demographic growth is not homogeneously distributed over a territory where socio-economic divisions are already made worse by a tight caste system. With evidence dating back to 2400 BCE, it must be remembered that India is a country of old urbanisation. This has given rise to a rich and complex history and India is now home to a variety of languages, religions, castes, communities, tribes, traditions, urbanisation patterns and, more recently, globalisation-related dynamics. Perhaps no other country in the world seems to be characterised by such a great diversity. This begs the following questions: how is it possible to quantify and visualise the spatial gap of such a complex and subcontinent sized country? What are the main drivers affecting this spatial gap? It would indeed be simplistic to study India only through macro-economic indicators such as GDP. To deal with this complexity, a conceptualisation has been performed to strictly select 55 criteria that can affect the transformation sustained by the Indian territory in this age of enhanced globalisation. These selected factors have fed a multi-critera database characterised by aspects coming from economy, geography, sociology, culture etc. at the district scale level (640 spatial units) and on a ten-year timeframe (2001-2011). The assumption is as follows: each Indian district can be driven by different factors. The human capacity to understand a complex issue has been reached here since we cannot take into account and at the same time the behaviour of a large

iv

number of elements influencing one another. AI Based Algorithm methods (Bayesian and Neural Networks) have thus been resorted to as a good alternative to process a large number of factors. In order to be as accurate as possible and to keep a transversal point of view, the methodology is divided into a robust procedure including fieldwork steps. The results of the models show that the 55 factors interact, bringing the emergence of unobservable factors representative of broader concepts, which find consistency only in the case of India. It also shows that the Indian territory can be segmented into a multitude of subspaces. Some of these profiles are close to the caricatured India. However, in most cases, results show a heterogeneous country with subspaces possessing a logic of their own and far away from any cliché.

Keywords: India, globalisation, urbanisation, middle classes, spatial segmentation, AI

v

Table of Contents

Remerciements ... ii

Abstract ... iii

List of Illustrations ... vii

List of Tables ... ix

List of Abbreviations ... x

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

PART ONE: GLOBALISATION, EMERGING COUNTRIES AND INDIA CHAPTER 2 HUMAN SOCIETIES AND URBANISATION IN THE AGES OF GLOBALISATION 2.1 The Roots of Globalisation: Complexity, Interdependence and Integrated World... 9

2.2 Emerging Countries and Spatial Disparities in the Age of Globalisation ... 29

CHAPTER 3 INDIA, FROM OLD URBANISATION PATTERNS TO MODERN GLOBALISATION PROCESSES 3.1 A Complex and Multilayered History of Urbanisation ... 49

3.2 Strong Economic Growth, Socio-cultural Disparities and Urbanisation Patterns ... 77

PART TWO: DATA COLLECTION AND MODELING CHAPTER 4 DATA COLLECTION PROCESS: INDICATOR SELECTIONS AND CONCEPTIONS 4.1 Systemic Analysis, Inductive Reasoning and Data-Driven Approaches: A Transversal Perspective ... 99

4.2 Dataset Constitution: Data Collection and Creation ... 110

vi

CHAPTER 5

CLUSTERING INDIAN SPACE: METHODOLOGICAL PROTOCOLS

5.1 Bayesian Reasoning and Bayesian Clustering ... 160

5.2 Neural Networks and Clustering ... 169

5.3 Applications of the Bayesian Protocols ... 180

5.4 Applications of the Self-Organizing Maps and Super-Organizing Maps Protocols ... 194

PART THREE: GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS AND FIELDWORK CHAPTER 6 CLUSTERING RESULTS AND GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS 6.1 Bayesian Networks and SOM/superSOM Clustering: Similarities and Differences ... 210

6.2 Description and Interpretation of the Clusters ... 214

6.3 Overview of India in the Age of Globalisation ... 241

CHAPTER 7 FIELDWORKS: METROPOLITAN AREAS, DYNAMIC MID-SIZED CITY AND NON-URBAN WELL-OFF INDIA 7.1 Metropolitan India: the Land of Extremes ... 250

7.2 Hubli-Dharwad: A Dynamic District ... 262

7.3 Non-Urban Well-Off India ... 271

CHAPTER 8 CONCLUSION ... 281

REFERENCES ... 289

APPENDICES ... 307

A. R Source Codes ... 308

B. Census of India: Official Maps and Definitions ... 319

C. District Borders GIS Reconstitution ... 324

D. Additional information about the e-Geopolis Research Program ... 325

E. Additional information about the Bayesian Experiment 6 ... 326

F. Additional information about the Fieldworks ... 343

vii

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: Intensity of International Travels through Sailing Ships leaving the European

Nations from 1662 to 1855 ... 12

Figure 2: The Global Situation at the Dawn of World War I in 1900 ... 16

Figure 3: 1970, the World Situation at the Dawn of the Financial Deregulation ... 20

Figure 4: Share (in red) and flows (in green) of Bilateral International Trade from 1996 to 2000 ... 22

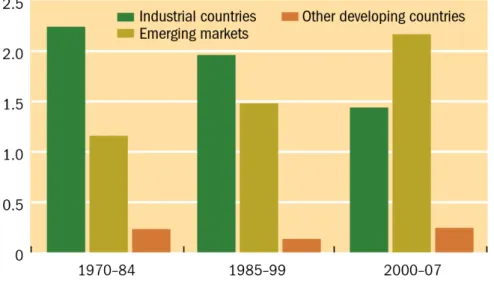

Figure 5: Contributions to Global Growth, at PPP Exchange Rates, Period Averages in Percent. ... 30

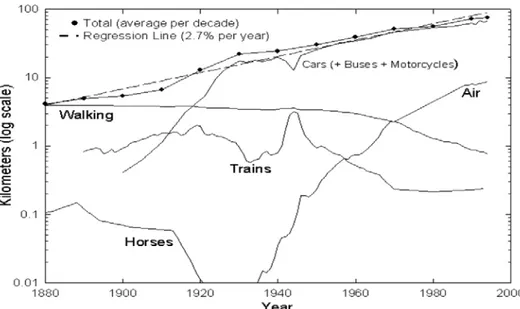

Figure 6: US Citizens Travelled Distances per day for all Modes (per person) 40

Figure 7: The Second Rise of Urbanisation; the Mauryan Empire at its Greatest Extent in the North and the Tamil Dynasties in the South during the Sangam Period ... 53

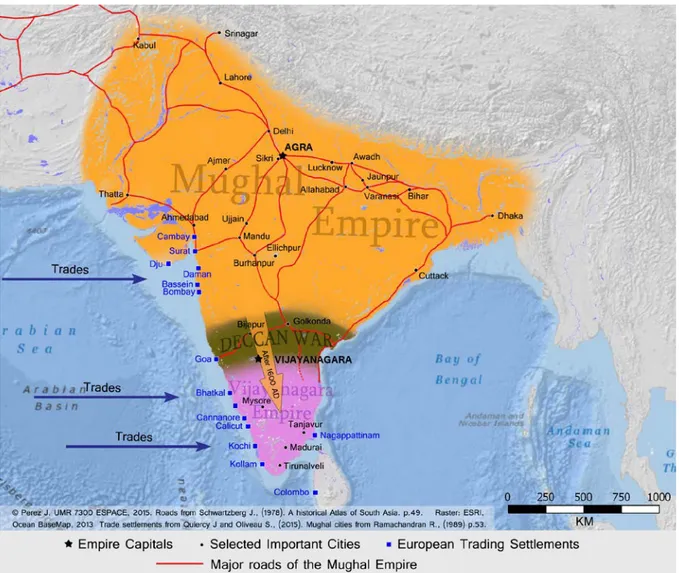

Figure 8: The Third Rise of Urbanisation; Mughal and Vijayanagara Empires, the Indian Situation during the 16th Century ... 59

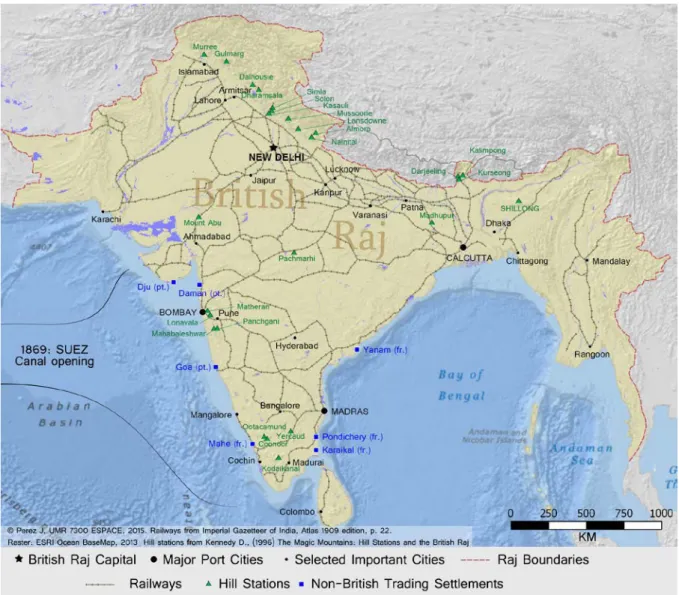

Figure 9: Structural Adjustments Made over the Urban System, the Situation of the Indian Subcontinent under the British Occupation in 1910 ... 68

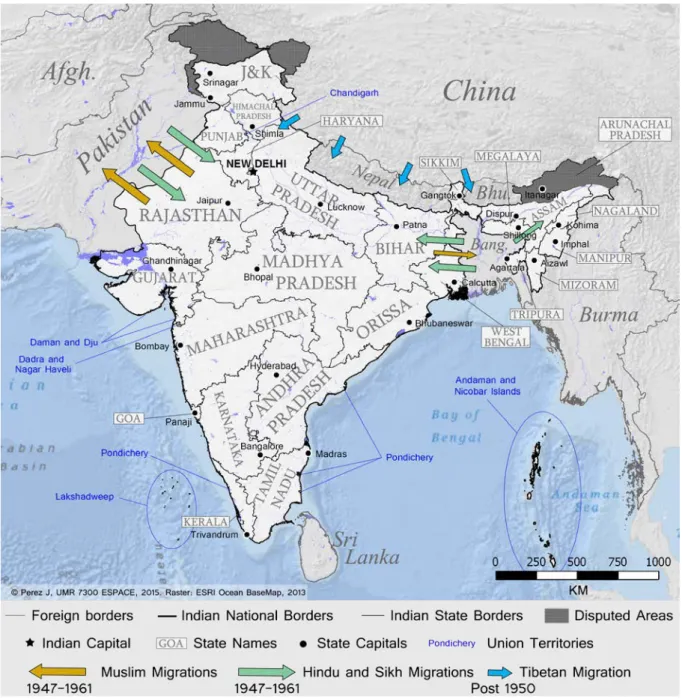

Figure 10: Post-independence Migrations, Disputed Areas and Indian Administrative Divisions in 1975... 73

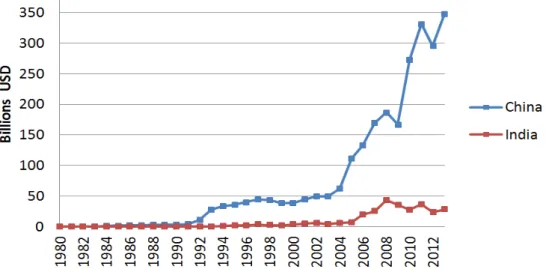

Figure 11: Foreign Direct Investment, A Comparison between India and China ... 81

Figure 12: Evolution of a standard Indian Urban Centre ... 90

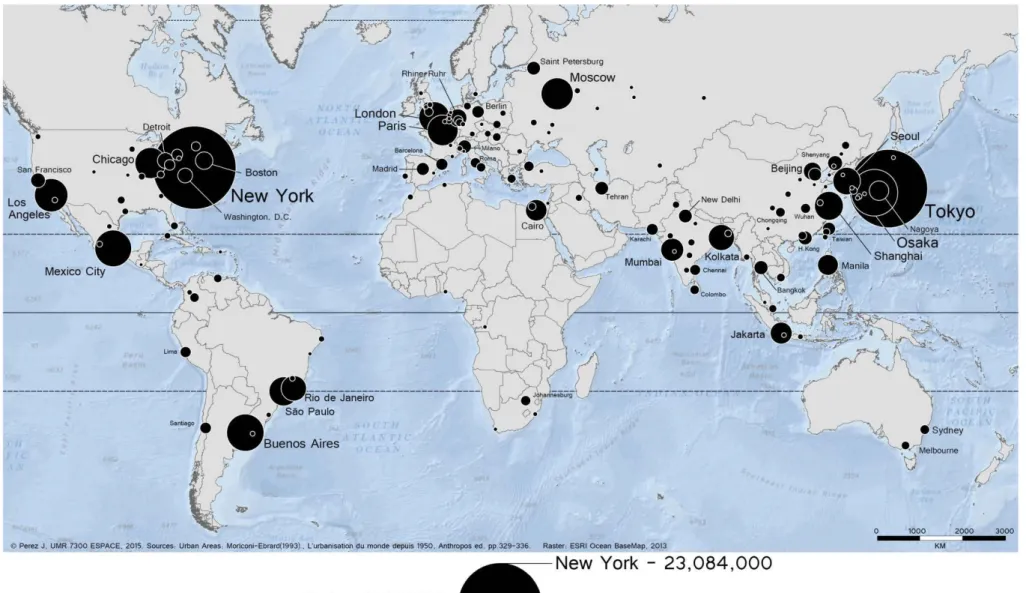

Figure 13: Population of the Continuous Built-up Areas above 10.000 inhabitants in 1981, 1991,2001 and 2011. ... 93

Figure 14: Von Thunen Model: "The Isolated State", One of the First Economic Models taking into account Space ... 103

Figure 15: A Conceptual Model used as a Guideline for Data Collection ... 108

Figure 16: Overview of the 640 Indian Districts in 2011 ... 111

Figure 17: The Aggregative process of Official Settlements within an e-Geopolis Built-up Area; Aligarh Urban Area example... 115

Figure 18: Share of Scheduled Castes per District in 2011 ... 119

Figure 19: Share of Children of Less than Seven Years Old in 2011 ... 121

Figure 20: Share of Secondary and Tertiary Workers among the Working Population in 2011... 123

Figure 21: Evolution of the Share of Secondary and Tertiary Workers between 2001 and 2011 ... 124

Figure 22: Share of Big Households (more than 6 persons) in 2011 ... 126

Figure 23: Share of Households possessing at least One Car in 2011 ... 129

Figure 24: Share of Households possessing No Assets in 2011 ... 131

Figure 25: Number of Dwelling units (rooms) in the Census of India. 133

Figure 26: Residential Welfare in 2011 ... 134

Figure 27: Residential Welfare Evolution between 2001 and 2011 ... 135

Figure 28: The Main Metropolitan Areas in India ordered by Rank ... 140

Figure 29: Distance to Rank 1 Metropolitan Area from each Indian District ... 141

Figure 30: Distance to Rank 1 Metropolitan Area from each Indian District ... 143

Figure 31: The Macro-Structures related to the Seven Rank 1 Metropolitan Areas ... 145

Figure 32: Distance to Four-lane National Highways from the Indian Districts ... 150

viii

Figure 34: A Bayesian Network Example. Source: Mitchell (1997) p. 186 ... 162

Figure 35: The Structural Learning of a Bayesian Network over the Iterations using Taboo Learning in BayesiaLab. ... 167

Figure 36: A 4x4 SOM and superSOM Network with their Input Space... 172

Figure 37: Rectangular and Hexagonal Fashion of a 4×4 SOM Grid (Output Space) ... 174

Figure 38: The Ever-Shrinking Radius on a 4x4 Grid Example ... 176

Figure 39: The Neighbourhood Influence on a 4x4 Grid following a Regular or a Toroidal Pattern 178 Figure 40: The Bayesian Network Learned from the India Dataset after 10 Taboo Order, a Fixation of the most Robust Arcs and a final Tabu Search ... 182

Figure 41: Variable Groups of the first HCA (coloured nodes) and Variable Combinations Frequency Graph after a k-fold Cross Validation for ten HCA ... 184

Figure 42: Variable Groups of the Rearranged Structure (coloured nodes) and Variable Combinations Frequency Graph after a new k-fold Cross Validation for ten HCA... 185

Figure 43: A BN Naïve Architecture Determining Latent Factors ... 186

Figure 44: Identification and Segmentation of the New Non-Observable Factor ... 189

Figure 45: Characterisation of the New Non-Observable Factor ... 193

Figure 46: Boxplots of FM Similarity Index values for 20 model initialisations... 203

Figure 47: District Clustering and Codebook Quality for the Three Models ... 204

Figure 48: Layer Optimisation: Mean Distance from Layers to the Closest Unit for Model 2 and Model 3 ... 206

Figure 49: Cluster Neighbourhoods, Cluster Sizes and Family Groupings Left: Bayesian Networks Experiment 6. Right: SOM/superSOM Model 3 ... 212

Figure 50: The Urban Family ... 215

Figure 51: Characteristic of the Urban Family from a Selected Range of Indicators ... 216

Figure 52: Clustering Location Comparison with the Kerala-Tamil Nadu Corridors Macro-Structure... 218

Figure 53: The Rural Family ... 222

Figure 54: Characteristic of the Rural Family from a Selected Range of Indicators ... 223

Figure 55: The Traditional Family ... 228

Figure 56: Characteristic of the Traditional Family from a Selected Range of Indicators... 229

Figure 57: Clustering Location Comparison with the Kolkata-Bihar Macro-Structure ... 230

Figure 58: The Last Family ... 235

Figure 59: Characteristic of the Last Family from a Selected Range of Indicators ... 236

Figure 60: Urban Structure Comparison: Left: Kerala; Right: Punjab. ... 237

Figure 61: Clustering Location Comparison with Delhi Macro-Structure ... 238

Figure 62: Clustering Classification according to Selected Dimensions ... 242

Figure 63: India in the Age of Globalisation ... 245

Figure 64: Map of Dharavi ... 252

Figure 65: Set of Picture from Dharavi. ... 253

Figure 66: Set of Picture from Dharavi, Bangalore and New Delhi. ... 257

Figure 67: Set of Pictures from Bangalore. ... 261

Figure 68: Hubli-Dharwad Conceptual Mapping ... 263

Figure 69: Hubli-Dharwad Picture Set 1. ... 266

Figure 70: Hubli-Dharwad Picture Set 2 ... 270

Figure 71: Kullu District Conceptual Mapping ... 272

Figure 72: Kullu District Picture Set 1. ... 275

ix

List of Tables

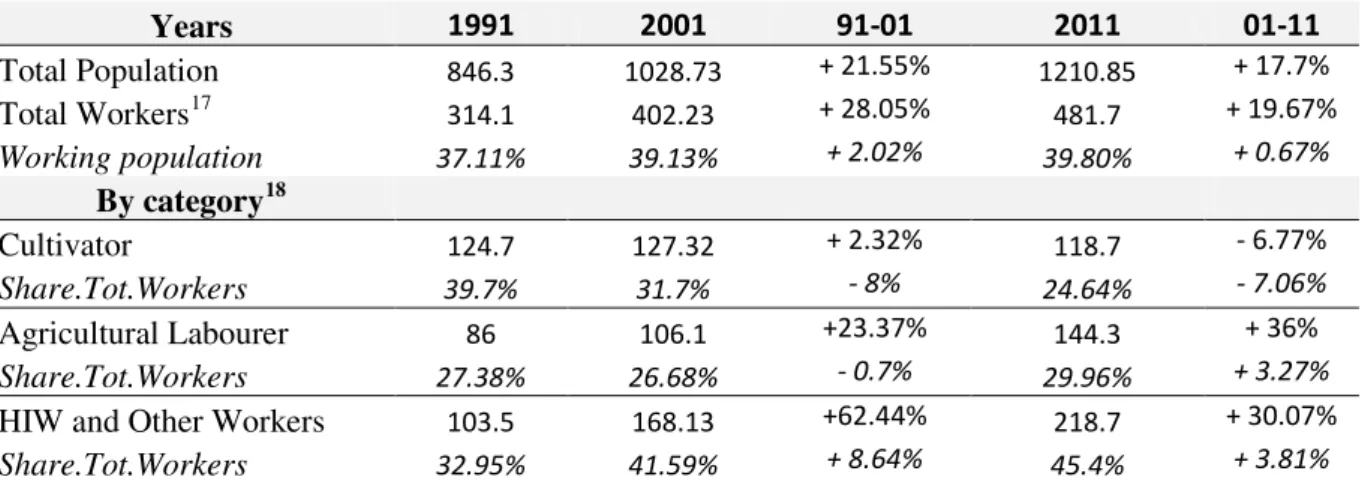

Table 1: Evolution of the Indian Workforce Structure (in millions) . 84

Table 2: Disparities between Men and Women ... 87

Table 3: Disparities between Men and Women: focus on Scheduled Castes (in millions) . 88

Table 4: Thresholds of Required Numbers of Rooms by Number of People in the Household... 133

Table 5: District characterisation by UA of more than 200.000 inhabitants ... 137

Table 6: Size of the Macro-Structures Related to Rank 1 Metropolitan Areas ... 145

Table 7: Inner Features of the three Biggest Macro-structures ... 146

Table 8: List of the 55 Collected Indicators that will be used as Inputs for the Clustering of Indian Districts ... 153

Table 9: Results of the Experiments ... 190

Table 10: Node Significance over the Target Node (Geographical Cluster) of Experiment 6 ... 191

Table 11: Bayesian and SOM/superSOM Models: Indicator Significances ... 210

x

List of Abbreviations

AI: Artificial Intelligence ANN: Artificial Neural Network ANOVA: Analysis of variance BCE: Before the Common Era BLI: Better Life Index

BMU: Best Matching Unit BN: Bayesian Networks

BRIC: Brazil, Russia, India and China

BRIC's: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

BSOM: Bayesian Self-Organizing Maps CE: Common Era

CIVET: Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt and Turkey

CNIS: National Council for Statistical Information (French agency)

DBMS: Database Management System EUA: Extended Urban Areas (footprint) EV: Electric Vehicle

FDI: Foreign Direct Investment

FERA: Foreign Exchange Regulation Act F-M: Fowlkes-Mallows similarity index GDP: Gross Domestic Product

GPS: Global Positioning System GSDP: Gross State Domestic Product GIS: Geographic information system GNH: Gross National Happiness GSCF: Gross Fixed Capital Formation GST: General Systems Theory

HDI: Human Development Index HCA: Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm HHLDS: Households

ICT: Information and Communications

Technology

INSEE: National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (French agency)

IPR: Industrial Policy Resolution IMF: International Monetary Found JK: Jackknife resampling

MRTP: Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act

N/A: not applicable (in table) NAM: Non-Aligned Movement NEG: New Economy Geography

NCTD: National Capital Territory of Delhi NN: Neural Networks

NSS: National Sample Survey

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OOP: Object-oriented programming OSM: OpenStreetMap

PPP: Purchasing power parity Rs: Indian Rupee

SC: Scheduled Castes

SEZ: Special Economic Zone SOM: Self-Organizing Maps

superSOM: Super-Organizing Maps SRA: Slum Rehabilitation Authority SRNN: Self-Reflexive Neural Networks ST: Scheduled Tribes

UN: United Nations

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UA: Urban Area or Urban Agglomeration VOC: Dutch East India Company

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

"Toutes les démarches du chercheur doivent pouvoir être explicitées, expliquées, justifiées, même quand il s'agit de l'intuition"1

Mialaret Gaston (2004)

I was told by senior researchers in India that the first months of a thesis are always the less productive ones. According to them, India was a country so complex that a young researcher not familiar with it should get used to starting off in several wrong directions. Looking back, I can't but agree with them. Basically, when I arrived in India, I got stung by almost everything. I am not referring to the well-known cliché of a traveller setting foot in India and experiencing for the first time a little bit of culture shock and seeing chaos everywhere. Of course, it is difficult to go against some clichés (especially in large cities) such as traffic jam which is associated with constant sounds of horns, people everywhere riding rickshaws, motorcycles, trunks, bicycles, vendors of all kinds walking through the traffic, pollution, overcrowding, etc. Yet, I spent some time in Africa and South America studying the self-organised transportation systems when I was an undergraduate student. All in all, seeing order in chaos was what I have been trained for but yet, I could not have felt less prepared for "handling India" as something seemed indeed very different about this country.

With the benefit of hindsight, I realise now that India is the very definition of a complex country. India is one of the most multi-faceted countries in the world and really is a mix of everything you can find around the world plus some specificities (such as the caste system). This country as it is today is the outcome of various civilisations that followed one another and is home now to a variety of languages, religions, castes, communities, tribes, traditions, etc., thereby increasing the degree of complexity of any topic you choose to address. During the first year of this research, I was indeed not aware of this complexity which is also reflected in the ways in which people interact. For example, there is a simple noncommittal nod that exists only in India and means neither "yes" nor "no". It is widely used for any topic of discussion and by all the strata of the population. You can for example order

2

some food in a restaurant and the waiter will give you that nod. What you must understand is that the waiter does not know if the food you just ordered is available in the kitchen and that he will check for you later.

Most of the time, when you ask an Indian what are his thoughts about the caste system he will tell you that "castes" are now a thing of the past and that there are no more caste problems in India. One day, a new director had been appointed in an institute in which I worked. The new director was a foreigner and during the welcome drink, he decided to shake hands with all the staff. Unwittingly, the first person he shook hands with was a dalit2 of the cleaning staff. Immediately after that, all the other people backed off and refused the handshake since the hand was now "impure". It is only later that I realised that the people with whom you interact the most as a foreigner are people speaking English fluently and most of these people are from upper castes at the top of the social ladder. They are not fooling themselves when they state that there are no more caste problems in India. The Indian society is fragmented and most of the people live and work within their community and/or within their caste. For the groups at the top of the social ladder, the inequalities related to the caste system are not reflected at all in their day-to-day routine.

To a Westerner, India turns out to be a country full of surprises on many occasions. I remember a friend of mine coming to my place in order to celebrate the fact that he was going to get married in the coming months. I congratulated him and asked how he met his bride. He gave me a strange look and told me that he hadn't met her yet and that he was waiting for his parents to introduce her to him. If arranged weddings are still common in India we should nonetheless be careful not to make any generalisation.

You may wonder why I am starting with these stories instead of introducing the research topic. The answer is quite simple; I think that these events have deeply affected my work. Even if the first months of this research were less productive than those which followed; they were at the same time the most decisive ones. Indeed, it quickly became apparent that the first thing you learn about India is that you cannot fully understand how it works. Diversity is so great in India that any generalisation becomes irrelevant. I therefore thought that if India was so complex, the best way to address it was to adopt a holistic point of view combining analytic and systemic approaches.

For a full year, I was welcomed within the Social Science department of the French Institute of Pondicherry which is an institution supervised by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development (MAEDI) and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). Most of my co-workers were not geographers and if they were,

3

they were not interested in spatial modelling. They often asked me when I was going to select my case studies. Actually, instead of going into the field, I spent the first year gathering data, making contacts and travelling through Indian megacities for various projects in collaboration with other researchers or with Renault. India is seen by multinational corporations as an emerging country full of opportunities. In this context, this research was funded by Renault and the geo-marketing applications derived from the analysis have been used for market penetration in India. Finally, I consider that this first period spent in India was a kind of immersion that allowed me to get a first glimpse of India and see the issues at stake in this research with new eyes. When I came back to France, I had gathered enough hindsight to consider a new approach consistent with the complexity displayed by Indian geographic space. My laboratory ESPACE, organised in three different French universities (Nice, Avignon and Aix-en-Provence) and specialised in spatial analysis and modelling gave me all the means to carry out this research in the best conditions.

Initially, the aim of this research was to evaluate the economic and development potential of the Indian mid-sized cities. The geographical literature indeed highlights the fact that megacities are becoming more and more saturated and that most of the potential for development may be located in mid-sized cities in a near future. However, it soon became apparent that the issues at stake in this research went much beyond the scope of the Indian mid-sized cities or even beyond the scope of India. In my opinion, a mid-sized city or any kind of human settlement could not be disconnected from its environment. But today more than ever, the problem lies in the identification of these environments. In this age of globalisation, is the area of influence of a city enough to define its environment? Moreover, this raises a question concerning these areas of influence since they can be multiple and varied (spatial, financial, cultural, etc.) and dependent upon a wide range of processes. Mid-sized cities can indeed be integrated into the daily functioning of a metropolitan area. In such cases, ignoring megacities would definitely be an error. Indian economy has been growing unabatedly for the last two decades but most of this economic growth is still absorbed and/or generated by megacities. From this perspective, these clusters of high development must also be considered as connected to the global economy and thus to an international context that goes beyond India.

The subject and the perspective of this research evolved accordingly in order to adopt a coherent approach able to take into account all at once the dynamics related to modern globalisation, the diversity and the complexity of Indian space. A main assumption has nonetheless been retained: it is highly plausible that urbanisation acts as a catalyst of development and Indian modernity, with the conviction that the role of urbanisation cannot be unique and unequivocal all across the Indian space. India is often caricatured as a country with two extremes only. On the one hand, it is considered as the new Eldorado, the "Shining India" and on the other hand and at the same time India is also characterised by overcrowding,

4

the major presence of slums and mass poverty, both in urban and rural areas. But, are these extremes truly representative of the diversity of the Indian space?

On the one hand, the urban population is steadily rising, a dynamic that leads to a strong increase of the urban middle classes. Yet, increases of standards of living and economic growth cannot be distributed in a homogeneous way within a territory where segregation is already worsened by a hermetic caste system. From this perspective, it should be possible to identify coherent spatial structures inductively from their different features and characteristics. Identification of relevant spatial structures may then allow questioning the role of the main drivers bringing these spatial differences. These spatial differences can subsequently provide useful information about the different living standards found throughout India. Finally, the issues at stake in this research have been expanded in order to answer a simple question: what does India look like from a spatial perspective in the age of globalisation?

From a methodological point of view, the approach should be purely inductive with no prior assumptions of wider subspaces within the Indian subcontinent. It should also take into account the share of uncertainty related to the diversity of the Indian space, the aim being to overcome the complexity of the Indian space in order to extract and analyse spatial tendencies. From this perspective, the protocol that will be developed during this research should: a) Address the whole Indian space. b) Be multi-criteria in order to reflect the different aspects of globalisation without ignoring the local specificities of the Indian territory. c) Take into account global and local phenomena in a balanced manner and simultaneously. This begs the following questions: how can aggregate measures of socioeconomic development, urbanisation and well-being be exploited to grasp, quantify and visualise the complexity of spatial differences within the Indian sub-continent? What is the best scale of analysis in order to obtain coherent spatial structures?

The research falls into three main sections with each section containing two chapters. The first section addresses the global context in order to provide a deep understanding of the issues at stake in this research. In chapter 2, India is temporarily set aside in order to chronicle the events that led to modern globalisation as we know it. It also provides an overview of the urbanisation patterns and dynamics under the light of the modern globalisation processes. In chapter 3, India is reintroduced and compared from a historical perspective to the different globalisation periods defined in the previous chapter. This chapter also reviews the specificities of India with a particular focus on economic policies, socio-demographic and cultural disparities and urbanisation dynamics.

The second section is about the data collection process and the methodological protocols developed especially for this research. Chapter 4 addresses the question of the philosophy behind this research and leads to the conception of a conceptual model used as a

5

guideline for data collection. The data collection process itself is then presented with indicators which were gathered from official sources and additional indicators which were designed specifically for this study, presented one by one. The final dataset made of 55 indicators is finally presented in the last section of this chapter. Chapter 5 is the methodological chapter of this research. First, it provides an overview of Bayesian and Artificial Neural Network reasoning when used for clustering purposes i.e. identifying groups of object. Two protocols developed especially for this research are then presented and their statistical results analysed. In the first protocol, Bayesian Networks are first used in order to extract latent factors and to cluster administrative districts within the Indian space. The second protocol follows the same logic but uses a specific kind of neural network (Self-Organising maps).

The last section provides an overview of the results obtained by the clusterings and by the fieldworks. Chapter 6 explores the statistical similarities/dissimilarities between the two models (Bayesian and SOM). It also provides a geographical analysis of each cluster profile according to the average values of the whole of India. The two clustering applications result in remarkably consistent (although sometimes slightly different) regionalisations of Indian space. In the last part of this chapter, the information obtained through the spatial analysis of the profiles are summarised in order to propose a sketch map of India in the age of globalisation. To conclude, some case studies have been selected according to the clustering results and are presented in chapter 7. The first case study is related to the forerunners of the Indian metropolitan modernity and covers some researches made in Bangalore, Mumbai and New Delhi. The second case study, the Hubli district is considered as a district possessing a very dynamic mid-sized city. The last case study focuses on the living standards of a district located within the Himalayas and far away from any "cliché".

In Chapter 8, thematic and methodological conclusions are presented and some further research perspectives are envisaged.

PART ONE:

GLOBALISATION, EMERGING COUNTRIES

AND INDIA

7

CHAPTER 2

HUMAN SOCIETIES AND URBANISATION IN THE

AGES OF GLOBALISATION

"Quoi de plus remarquable et de plus important que cet inventaire, cette distribution et cet enchaînement des parties du globe ? Leurs effets sont déjà immenses"3

Paul Valéry, Regards sur le monde actuel (1931, p. 17)

All around the world, people are living in a society that could not even have been imagined a century earlier, a society often described as integrated and connected at a worldwide scale. Men are indeed living in a world where the flows of both materialised and dematerialised goods, as well as the flows of people, increase and move faster. Everywhere, people are thus feeling the effects of this global world. Perhaps even more important and significant is the feeling that these processes are increasing and accelerating over time. For some authors, these processes are related to the "globalisation" phenomenon. Globalisation is a multifaceted term: the process of the processes for researchers daring to address such a complex issue, a good excuse for the corporations relocating their activities, an opportunity for the emerging countries, a sealed fate for the non-skilled workers of the old industrialised countries, etc. What if globalisation was just a catch-all term used to describe something that, taken as a whole, goes beyond the limits of understanding?

If we stick to the facts, it is easy to notice that people now live in a society where everything is changing very rapidly, more rapidly than in any previous civilisation. Some aspects of this society are hyper-mediatised thus enhancing the belief that we all live in a global and single society. In this "global society", the economic and governmental systems seem somewhat interdependent and remarkably similar from one country to another. This global system has indeed extended at a tremendous speed and now characterises most countries in the world while alternative models, such as communism, declined. Yet, is this global system really in the interest of all? In other words, are the globalisation processes

3 What is more remarkable than the different parts of the world, their distributions and their concatenations? their effects are already substantial.

8

acting for the "greater good"? As a matter of fact, the freedom of the financial flows seems to be historically what has given rise to the core of the globalisation concept. However, today more than ever, reducing globalisation to the financial sphere only is short-sighted. It is indeed true that from a financial point of view, economic liberalisation policies that started around the 1980s gradually brought down the worldwide financial barriers. Subsequently, the following decade saw the rapid development and growth of the Asian markets, starting in a very impressive way with China.

Today, this situation is enhanced by a specific context: in the modern world, more than half the population live in cities. Indeed, the increase of urban population usually goes hand in hand with economic growth and leads to a pattern in which both production and efficiency of production increase. Cities also provide an environment that encourages innovations of all kinds. These innovations are then gradually spread over the territory following complex patterns. Thus, one can legitimately wonder whether the model that brought down the worldwide barriers dividing human societies can be extended to further dimensions than the financial sector only. In other words, are these modern globalisation processes leading to a homogenisation of the world in all of its aspects? As we shall discuss, the concept of a single world society put forward by several authors remains purely ideological especially in terms of spatial homogeneity. Furthermore, it would even seem that the dynamics related to this modern era of rapid changes are far from simplifying the way in which geographical space is structured. It is even possible that the spatial heterogeneity of space is but a reflection of the societal inequalities in this age of enhanced globalisation. If so, perhaps globalisation will enhance the spatial inequalities rather than erase them.

This chapter is divided into two sections. The first one describes the regional background which allowed for a progressive set up of an interdependent world and depicts an overview of the modern world through globalisation processes. The second one addresses the disparities and the rapid transformations from a spatial point of view arising from the rapid globalisation of the world. It is concluded by the stand point adopted within this research in order to understand the specific geographical situations arising from this modern era of rapid changes.

9

2.1 The Roots of Globalisation:

Complexity,

Interdependence and Integrated World

2.1.1 Ages of Globalisation, the Roads that Lead to the Modern World

According to most researchers, identifying the starting date of globalisation processes is a complex issue. One can mention the Silk Road as an example of the complexity of such an issue. Indeed, by connecting regional blocs as early as 200 BCE, can this old trade market be considered as a premise of globalisation? One thing is certain; globalisation is made of the word "global" thus etymologically referring to something that encompass the whole of something else. Our planet, the physical support of the globalisation processes is a globe and, geographically speaking, it is interesting to note that this globe no longer has any secrets for mankind. As Paul Valéry stated, "the time of the finite world has come"4

. For example, there

are no more unknown locations to find new resources. However, it was not always that simple. In order to obtain a better understanding of today's world, it is necessary to make a leap back in time to understand how the main regional blocs have been linked together. Moreover, as we shall discuss later, globalisation may just be a catch-all term used to describe a wide variety of phenomena. Then, before studying the world under the light of the modern globalisation, it is more relevant to focus on the key points and main periods of history that have led to the international integration of various and heterogeneous locations around the world.

In terms of financial globalisation, Obstfeld and Taylor (2003, pp. 123-125) identified the following four periods: a) 1870-1st World War: a market dominated by England; b) the inter-war period: decline and great depression; c) 1945-71: an attempt to rebuild global economy and d) the post-70s period characterised by an increase of capital mobility. From a more geographical point of view, Ferrier (1993, p. 252) identified three main periods by questioning the very foundations that define the contemporary world. The first one corresponds to the European expansion waves that resulted in colonisation (approximately from the late 14th century to the end of the 19th century). The second one describes the following decades of the First World War: a world characterised by the tyranny of speed. The last period is a more responsible post-crisis world following for example the 1968

10

protestations against the assembly lines or the 1973 first oil crisis. The historian Hobsbawm also identified four main periods, with titles for each period that speak for themselves: The

Age of Revolution: 1789-1848 (1962), The Age of Capital: 1848-1875 (1975), The Age of Empire: 1875-1914 (1987) and The Age of Extremes: 1914-1991 (1994).

Following the same logic as the works stated above, the coming sections will search to define the main historical periods that lead to this modern era of enhanced globalisation. The following periodisation is thus focused on how men gradually became interconnected, what the main processes characterising these periods are and what may be considered as a transition between each period. In order to prevent any neologism concerning the use of "globalisation", this term will deliberately not be used within this first section. As we shall discuss, the evolution of the regional blocs is strongly linked to colonialism, colonial wars between European nations, technical and technological progresses and to the progressive implementation of free trade policies around the world up to the post-World War II financial deregulation period.

A. First Period - Trading Posts and Colonisation: the First Steps of a Connected World

As a matter of fact, trade between civilisations has always been a characteristic of human societies since the premise of urbanisation. Indeed, it is a well-known fact that without the trade surplus generated by agriculture, building cities would not even have been possible (Bairoch, 1985). As early as 500 BCE, a major commercial gravity centre of particular significance is found in Ancient Greece. This civilisation had set up a noteworthy trading network composed of several colonies along the Mediterranean coasts. Even earlier, the Phoenicians had built substantial trading routes on the southern part of the Mediterranean area whereas even oldest traces of trade related to the Mesopotamian civilisations around the Fertile Crescent can be found. The Silk Road may also be cited as an example of a major trade route that connected major regional blocs on an even larger scale around 100 BCE. However, the ancient times being another debate, we will directly focus on the very first period of history that connected all the continents on a permanent basis. As we shall discuss, this period is located far further in the history of human societies. Since the exact chronological limits of historical periods are often open to debate, we are not going to refer to well-defined beginnings and ends. However, the period which is being discussed here roughly matches the historical Early Modern Period (1500-1800 AD).

In short, the Age of Discovery can be considered as the initial impulse of this period. During this stage, the Portuguese promptly followed by other European nations established direct contacts through the oceans with far away continents such as the Americas, Asia and Africa. Subsequently, a large number of settlements were established in these places by the

11

main nations dominating this era. The global exploration was soon followed by a process of expansion which benefited from the improvement of navigation and mapping techniques during the European Renaissance.

After the exploration race, these settlements were used as entry points in these foreign lands. At first basic implantations, they quickly evolved into trading posts providing the basic needs to the constitution of major colonial empires. The colonisers established an unquestionable domination on the native peoples due to their superiority acquired through a particular chain of developments over time (e.g. Diamond, 1997). Yet, the major factor that allowed this domination was the imbalance in terms of technology between Europeans and local civilisations. It led to a pattern in which the number of overseas colonies quickly rose while prominent seaways used to trade with the European homelands soon covered five continents. These seaways were principally established toward the eastern coastline of the Americas, Africa, South Asia, and South-East Asia. The most noteworthy empires of this era were the Spanish, the Portuguese, the British, the French colonial Empire and the Dutch Republic.

In any case, a recurring pattern of this period is that each kind of implemented overseas settlement amounted to specific advantages and benefits headed toward the coloniser homelands (Brunschwig, 1949; as discussed in Balandier, 1951, p. 53). By oversimplifying the complex reality of the processes of colonisation, it is possible to sum up the aims of this colonial model with the following points:

- Access and exploitation of resources in order to export goods to Europe and to respond to a growing demand from the European consumer society.

- The benefit of a strategic location, the aim being to set up an optimal network in order to trade in the most efficient way with the respective homelands.

12

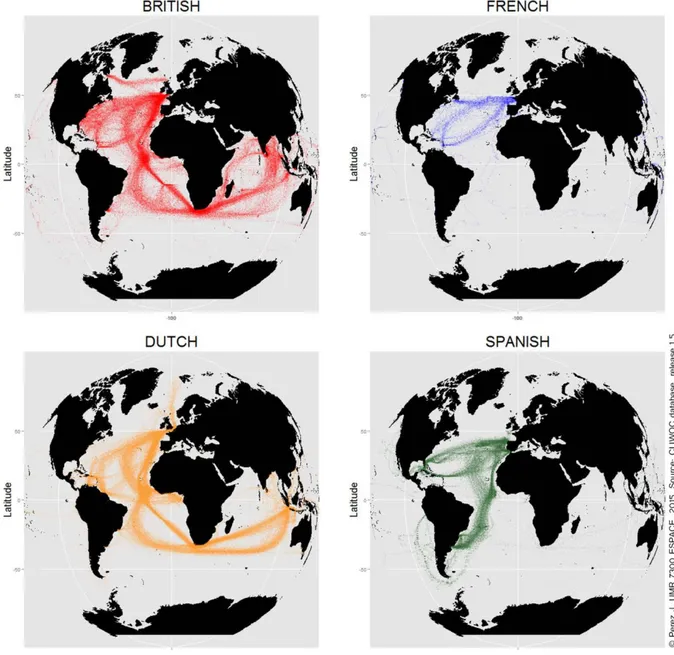

Figure 1: Intensity of International Travels through Sailing Ships leaving the European Nations from

1662 to 18555

As displayed in Figure 1, this period is marked by the kick off of dynamic trade between the trading posts and the homelands. One of the most famous trade patterns of this period is the triangular trade (goods, slaves etc. between the Americas, Africa and Europe). From a spatial point of view, the configuration of trade in Europe has evolved with a gravity centre in the northern part of the old continent and no more around the Mesopotamia /

5 Figure 1 has been created using the CLIWOC database. It has to be pointed out that due to loss of materials

(mostly fires and natural disasters) the travels made by the Portuguese vessels are not available within the CLIWOC database. Nevertheless, this database contains the travels made during the lifetime of 1.624 vessels that have been extracted through old ships logbooks (Herrera et al., 2003, p. 9). Figure 1 has been realised using R, the source code is available in Appendix A.

13

Mediterranean Sea like it used to be during the ancient times. Figure 1 shows the journeys made by British, French, Dutch and Spanish ships and thus highlights the major international maritime shipping routes of this era. It is important to note that this period is marked by mercantilist policies. This economic model is characterised by the capacity of a country to accumulate and trade surplus at the expense of the other nations. In other words, the aim was to generate earning from distribution and taxation rather than production. As pointed out by Weber (1905), mercantilism puts forwards the state as a political power by increasing the taxpaying power of the population. Historically, such policies led to trade restrictions since the colonies were often ordered to trade with the homeland only. Indeed, Figure 1 also reveals privileged geographical areas for each European nation. For example, the Spanish took a very early interest in South America whereas, overall, the British and the Dutch were the better established nations globally. They were indeed covering grounds in most parts of the globe with a remarkable presence in Asia compared to the Spanish and French empires. Over time, mercantilism motivated both wars between the European nations and colonial expansions.

To conclude on this period, as pointed out by Stein (2005), a recurring pattern is the rapid divergence between the interests and agendas of the homelands and the colonies themselves. These divergences led to the independence of some colonies like the United States from the British Empire in 1776. From a geographical point of view, this first period can be summarised by a gradual anchorage of the European power around the world, each of these settlements being part of a potential network connecting the world together for the very first time.

B. Second Period - Free Trade and Industrialisation: the British Domination

At the end of the 18th century, major changes took place in the dominant economic policies of the time. It gradually led to a fundamental reorganisation of the worldwide trade system. To begin with, it is important to keep in mind that a series of wars between the European Empires (mainly due to the mercantilist policies) left the British Empire as the main dominant power of this era. Thanks to its victories, the British Empire took a significant lead compared to the other empires in terms of technology and manufacturing. After the fall of Napoleonic France around 1815, the British Empire was free to prosper and thus remained one step ahead of its neighbours. Two important events marked the beginning of this new era: the First Industrial Revolution and the introduction of free trade policies.

Historically, free trade policies were not planned nor desired. Following the ongoing rebellions on the American colonies, the British government implemented a measure called the 1775 Prohibitory Act. The aim of this Act was to forbid trade with the American colonies

14

in order to put pressure on them and destroy their economy. Paradoxically, this Act had the opposite effect. Indeed, the former American colonies were forced to open their ports to foreign vessels in order to keep trading thus speeding up the independence process. Nonetheless, the British Empire, in the long term, appears to be the country that benefited most from these free trade policies that were finally officially implemented in 1840. As seen in the previous section, being the winner of the previous mercantile system left the British Empire one step ahead of its European rivals. This advance was decisive during the first stages of the industrial revolution.

As for many historical periods, the beginning of the first industrial revolution differs according to the studied literature. We will retain a period of major changes from 1789 to 1848 described by Hobsbawm in the Age of Revolution (1962) as the confluence of industrial revolution and French revolution. In this research, the kick off of the industrial revolution is estimated around 1780 in Britain while in Continental Europe it is estimated a few decades later. In short, this period is characterised by the transition from handmade products to automated manufacturing. Innovations and industrial revolution reinforced each other thus bringing a global increase of both production and productivity. Some of these innovations can be considered as disruptive i.e. a technology that replaces a previous one (Bower and Christensen, 1995), one of the most famous examples of this era being the replacement of sailing ships by steam-powered ones resulting in an increase of trade on rivers through the use of paddle-wheel steamboats. This innovation was a factor (among others like the transcontinental railroads for example) that led to a rapid development of settlements initially located far away from the coastline. For countries like the United States, this period is characterised by the progressive establishment of an urban system out of nothing. For example, the famous American Frontier period is from a spatial point of view marked by an outer line of settlements moving steadily westward until the end of the 19th century. As we shall discuss later, some countries like India already had a viable urban system long before European colonisation.

The Austrian economist Ludwig Von Mises argued that the mentality of the pre-capitalistic era would not have been capable of the industrial revolution. According to this author, free trade and the industrial revolution must be considered as two sides of a same coin (as discussed in Ashworth, 2014, p. 179). During this period, two major English-speaking classical economists paved the way for the concept of economic liberalism. They had a major impact on the way in which trade was handled within the British Empire. The first one, Adam Smith, exposed his main theories about economic prosperity in The Wealth of Nations (1776). In short, Adam Smith put forward the fact that the economic freedom of the actors of all the social classes could lead to the prosperity of a nation as a whole. Each actor needs to possess a specific competence in order to trade or sell his knowledge within a liberalised market. The

15

second one, David Ricardo, argued that all nations could benefit from free trade. He advocated in On The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) that a country exporting the goods for which it has a comparative advantage will automatically lead to economic growth. After the division of labour of Adam Smith which was referring to working specialisation, the comparative advantage of David Ricardo was by contrast focused toward an economic specialisation within geographical space. The models described in these theories increase the inability of a person (for Smith) or of a given territory (for Ricardo) to survive outside of an interdependent system consisting of spatially fragmented and industrially specialised components.

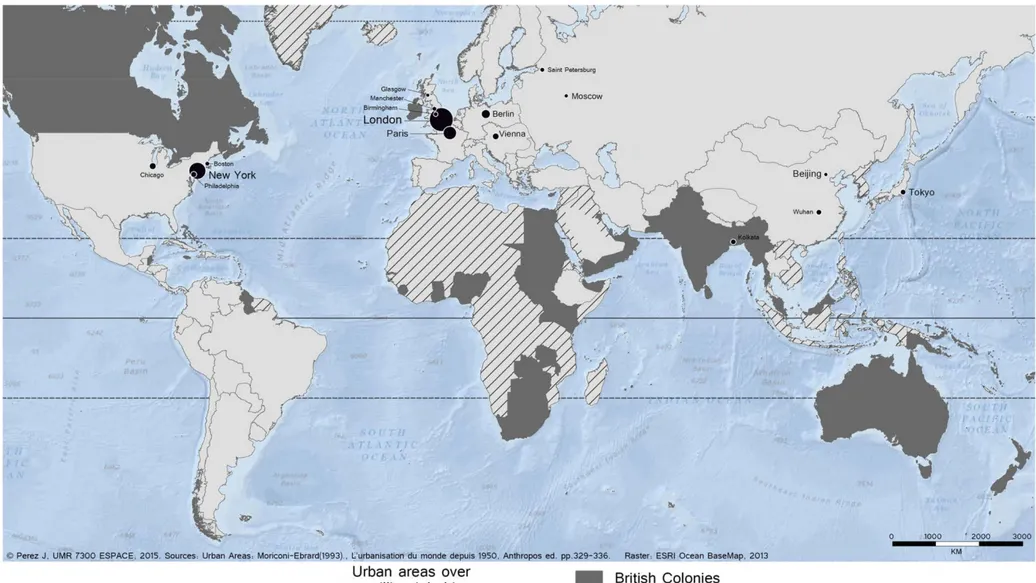

Using these strategies and the advance accumulated during the first industrial revolution, the British Empire used the merchant sea-lanes efficiently and dominated worldwide trade for nearly a full century. From this perspective, it is interesting to note that Hobsbawm (1975) described Latin America, India and China as being already the main losers of this Age of Capital. Furthermore, thanks to the success of the British model, wages in England remained high while other European economies experienced several falls (Allen, 2006, p. 3). During this stage, England gathered forces and produced a so-called empire of machines (Cox, 1960, p. 269). Figure 2 summarises the situation of the world before World War I in 1900. In this figure, the population mapped is the urban population living in continuous urban areas of over 1 million inhabitants (Moriconi-Ebrard, 1993, pp. 329-336) with absolutely no regard given to administrative boundaries (e-Geopolis research program as discussed in chapter 4,§4.2.1). It shows a world in which London is the biggest urban area in the world and in which most of the overseas colonies are British. Moreover, Kolkata, a city created by the British was at this stage of history the only city over 1 million inhabitants within colonised territories.

17

The industrial revolution quickly radiated out from Great Britain with other nations following in its wake. Ultimately, the British Empire would be caught up, matched and eventually surpassed in terms of manufacturing production by its former colony, the United States and by Germany around the end of the 19th century. Germany sustained a spectacular demographic growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries thanks notably to the dynamic industrialisation of the Rhine-Ruhr geographical area. It is finally through the rapid industrialisation of this area that Germany would have the adequate means to trigger the two upcoming world wars. To a lesser extent, the manufacturing capacities of France and Japan were also important. With two cities over 1 million inhabitants (Beijing and Wuhan), the advance in terms of urbanisation taken by China must also be highlighted. Indeed, if we put aside the countries of old industrialisation (Europe, the U.S and Japan), China was the only sovereign country possessing such important cities (even if the sovereignty status of China needs to be discussed, chapter 3, § 3.1.4). Under the impulse of its European neighbours, the

Russian Empire caught up the delay accumulated in terms of industrialisation at the end of the

19th century. New policies then attracted foreign investments to the industrial sector and led to the development of important cities such as Saint Petersburg. However, the Russian civil war (1917 - 1922) ended with the constitution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), a new regime characterised by the closing of their domestic markets to foreign countries and the complete nationalisation of industries, banks, etc.

To conclude, this period can be characterised by capital accumulation, investment and development of the existing industries. The interaction of all of these processes led to a constant increase of both production and productivity thus giving momentum to a mass production model. From a geographical point of view, this second period can be summarised by a gradual and worldwide establishment of the urban activities through the interstices of a world mostly dominated by agriculture. Moreover, the industrial revolution brought a new generation of specialised towns with a specific urban morphology (such as the ones described in Alexandersson, 1956). As pointed out by Pumain (1995), these new towns affected and transformed the structure of the urban systems that were already established.

C. Third Period - Financial Deregulation and Market Opening: a post World-War II World

The end of the previous period is strongly associated with the employment of assembly lines. They were an important feature of this era that led to a standardised pattern of mass production sometimes referred to as "Fordism". Indeed, the most famous example is the production of the Model T, a car that was developed by the American Ford Motor Company. The implementation of assembly lines allowed reducing by nearly four times the selling price of this model (Ford Mediacenter, 2012). But Fordism was not just about assembly lines. It also referred to a new norm since when production increased, unit price was lowered and

18

workers received better wages. This new system was based on a bet made by Henry Ford6, who believed in standardising the workforce rather than standardising the production alone. By raising wages, this new system indeed attracted motivated workers and led to an increase of global productivity. As a result, an industrial middle class emerged and had more and more access to affordable technologies. More than a reinforcement of middle class purchasing power, this period can be characterised by the democratisation of mass consumption. A parallel with Say's law (1801) stating that "the more men can produce, the more they will

purchase" seems quite suitable. The quintessential feature of this model is indeed a necessary

link between mass consumption and mass production (e.g. Aglietta, 1976; Pietrykowski, 1995) in order to generate a capitalised surplus value. Ferrier (1993, p. 252) described this period between the First World War and the first Oil Crisis quite clearly and unambiguously as a world dominated by the tyranny of speed. However, the focus of this study is the connection between the different parts of the world rather than the different modernity waves. As a result, I do consider the mass production / mass consumption couple as the logical climax and outcome of the previous industrialisation / free trade couple while the transition leading to the third period described below is characterised by a new geopolitical reality and important structural changes in the worldwide economy.

After the destruction engendered during World War II, the priority was to take advantage of the post-war boom by rebuilding cities as fast as possible. Thus, the middle class paradigm (within the Marxist meaning of the term) where the workers sell their labour capacity within a system where wages are market determined will evolve. We are indeed in the "post-war boom" (known in French as "les Trente Glorieuses"), period that saw the economic growth of most of the developed countries and led to an increase of both productivity and worker wages as it had happened forty years earlier in the U.S with Fordism. These decades of economic prosperity were also characterised by an important increase of the urbanisation rate. It is worth recalling that the middle class is a contemporary concept born in urban oriented spaces since in traditional and rural societies, the group of people in the middle of the social hierarchy can not constitute a majority of the population. Given the fact that urbanisation and economy both grew, the middle classes were strengthened as never before during this period. However, the technological progresses and the emergence of new markets around the world will soon reduce the post-war boom to a transition toward a new period characterised by a shift of the priorities for the industrialised countries from manufacturing to finance.

The beginning of this third period is marked by a geopolitical turning point. Indeed, after World War II, colonialism as practised by European powers for over three centuries

19

came to an end. A succession of decolonisation waves mostly from the 1950s to the 1980s gave sovereignty to most of the former European colonies. The process of emancipation of the former colonies differs according to the studied country. Sometimes, it was desired by both colonised and colonisers and came about gradually and peacefully, like in the case of most French colonies in Central Africa. However, when there was no alternative, a rebellion from the native peoples could occur. These rebellions could be non-violent like the Indian

Independence Movement, or unfortunately, they could have to go through a war like in the

case of the Algerian Revolution. Nonetheless, a recurring pattern of the 20th century decolonisation waves is that unlike the previous decolonisation waves (the United States for example), these ones would benefit the native peoples rather than the colonisers. The decolonisation pattern spread among all the former European possessions as reflected in the creation in 1961 of a Special Committee on Decolonisation (SDC) by the United Nations.

From a structural point of view, the economic system running during the premise of this period is mainly dominated by top-down regulations with strong interventions of the states on the trade policies. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), the British economist John Maynard Keynes demonstrated that the modern economic system of this period was more and more complex and thus cannot be self-regulated (discussed in detail in § 4.1). As a result, an economy in a state of crisis could remain frozen indefinitely. This new perspective demonstrated that to be able to modify to internal characteristics of a local economy, actors should play on external factors at a wider scale. The

Great Depression of 1929 gave a large credibility to his work and subsequently, the

Keynesian model served as the standard economic model for many decades. From this perspective, the Bretton Woods system designed to control capital movements between countries was set up and ratified by most of the developed economies in 1945. After World War II, the priority was to rebuild the nations through a strong world monetary organisation. This new system was going to be built around the U.S Dollar since after World War II, the U.S were in a powerful position to negotiate. Subsequently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank international institutions were created in order to regulate the financial sphere.

21

The post-World War II world was in motion more than ever especially as the decolonisation processes were engaged. As a result, famous economists would firmly and strongly oppose the Keynesian theories and have a major influence within the modern economic system. Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), in The Road to Serfdom (1944) strongly criticised the role of the states. According to this author, within a world characterised by the emergence of new markets, the economic system has to be free. Milton Friedman in

Capitalism and Freedom (1962) promoted a system in which the political and economic

spheres should be independent in order to bring the perfect conditions for the development of a free market. They both respectively advised the Thatcher government (1979-1990) and the Reagan administration (1981-1989). With such reflexions aimed at making the financial sphere freer, a reject of the Keynesian economics and a new kind of doctrine appeared: economic liberalism. In short, the new policy was to reach an economic optimum by removing state regulations. From this perspective, the Bretton Woods System blew apart by the late 1960s in a context of increasing trades and capital flow movements across borders (e.g. Obstfeld and Taylor, 2003; Fischer et al., 2012). However, it should be pointed out that under this new global economic trend, most of the newly independent nations followed at first a defensive political line concerning the opening up of their domestic markets. It is quite understandable since these countries accumulated a considerable delay in terms of industrialisation due to the former colonial policies. These measures were for example aimed at limiting the increasing returns made by multinationals in order to protect domestic producers in a context of nascent industry. Indeed, in a global and interconnected world, the prospect of unequal exchanges between countries at different stages of development is increasingly relevant. It is a well-known fact that in some cases and with these development gaps between emerging and advanced economies, financial deregulation and the gradual fading out of customs taxes may hamper a country's potential for development (Robinson, 1979). The last decades have witnessed the dismantling of most of the remaining trade barriers. For example, the successive agreements of the World Trade Organization (WTC) aiming at lowering global trade barriers have been ratified by a majority of countries in the world.

Therefore, is it really the deregulation policies put in place during the Reagan-Thatcher administrations that have brought and enhanced economic liberalism? Or, is it the urgent need to fundamentally rethink the role and purpose of the states within a world made of the gradual emergence of new markets? To illustrate this point, Figure 3 displays the major urban areas of more than one million inhabitants in 1970. The contrast with the previous

Figure 2 is striking. Major cities had emerged in nearly every continent, major cities that

began to be regarded as key players within the organisation of international economy. It is interesting to note that in 1950, the Asian continent was already home to 32% of the urban population of the world (United Nations, World Urbanisation Prospects, 2007, p. 7). The