HAL Id: hal-01269201

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01269201

Submitted on 27 May 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

A long photoperiod relaxes energy management in

[i]Arabidopsis[/i] leaf six

Katja Baerenfaller, Catherine Massonnet, Lars Hennig, Doris Russenberger,

Ronan Sulpice, Sean Walsh, Mark Stitt, Christine Granier, Wilhelm Gruissem

To cite this version:

Katja Baerenfaller, Catherine Massonnet, Lars Hennig, Doris Russenberger, Ronan Sulpice, et al..

A long photoperiod relaxes energy management in [i]Arabidopsis[/i] leaf six. Current Plant Biology,

Elsevier, 2015, 2, pp.34-45. �10.1016/j.cpb.2015.07.001�. �hal-01269201�

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Current

Plant

Biology

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c p b

A

long

photoperiod

relaxes

energy

management

in

Arabidopsis

leaf

six

Katja

Baerenfaller

a,∗,

Catherine

Massonnet

b,1,2,

Lars

Hennig

a,c,

Doris

Russenberger

a,

Ronan

Sulpice

d,3,

Sean

Walsh

a,4,

Mark

Stitt

d,

Christine

Granier

b,

Wilhelm

Gruissem

a,∗aDepartmentofBiology,ETHZurich,CH-8092Zurich,Switzerland

bLaboratoired’EcophysiologiedesPlantessousStressEnvironnementaux(LEPSE),INRA-AGRO-M,F-34060MontpellierCedex1,France cDepartmentofPlantBiology,SwedishUniversityofAgriculturalSciencesandLinneanCenterforPlantBiology,SE-75007Uppsala,Sweden dMaxPlanckInstituteofMolecularPlantPhysiology,D-14476Golm,Germany

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received18February2015 Receivedinrevisedform7May2015 Accepted10July2015 Keywords: Photoperiod Arabidopsisthaliana Leafgrowth Proteomics iTRAQ Transcriptomics Tilingarray Phenotyping

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Plantsadapttotheprevailingphotoperiodbyadjustinggrowthandfloweringtotheavailabilityofenergy. Tounderstandthemolecularchangesinvolvedinadaptationtoalong-dayconditionwecomprehensively profiledleafsixattheendofthedayandtheendofthenightatfourdevelopmentalstagesonArabidopsis thalianaplantsgrownina16hphotoperiod,andcomparedtheprofilestothosefromleaf6ofplants grownina8hphotoperiod.WhenArabidopsisisgrowninalong-dayphotoperiodindividualleafgrowth isacceleratedbutwholeplantleafareaisdecreasedbecausetotalnumberofrosetteleavesisrestricted bytherapidtransitiontoflowering.Carbohydratemeasurementsinlong-andshort-dayphotoperiods revealedthatalongphotoperioddecreasestheextentofdiurnalturnoverofcarbonreservesatallleaf stages.Atthetranscriptlevelwefoundthatthelong-dayconditionhassignificantlyreduceddiurnal tran-scriptlevelchangesthaninshort-daycondition,andthatsometranscriptsshifttheirdiurnalexpression pattern.Functionalcategorisationofthetranscriptswithsignificantlydifferentlevelsinshortandlong dayconditionsrevealedphotoperiod-dependentdifferencesinRNAprocessingandlightandhormone signalling,increasedabundanceoftranscriptsforbioticstressresponseandflavonoidmetabolisminlong photoperiods,andforphotosynthesisandsugartransportinshortphotoperiods.Furthermore,wefound transcriptlevelchangesconsistentwithanearlyreleaseoffloweringrepressioninthelong-day condi-tion.Differencesinproteinlevelsbetweenlongandshortphotoperiodsmainlyreflectanadjustmentto thefastergrowthinlongphotoperiods.Insummary,theobserveddifferencesinthemolecularprofilesof leafsixgrowninlong-andshort-dayphotoperiodsrevealchangesintheregulationofmetabolismthat allowplantstoadjusttheirmetabolismtotheavailablelight.Thedataalsosuggestthatenergy manage-mentisinthetwophotoperiodsfundamentallydifferentasaconsequenceofphotoperiod-dependent energyconstraints.

©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Contents

1. Introduction...35

2. Materialandmethods...35

2.1. Plantmaterial,leaf6androsettegrowthmeasurements...35

2.2. Carbohydratedeterminations...36

2.3. TilingarraytranscriptdataandquantitativeiTRAQproteomicsdata...36

2.4. Statisticalanalysesoftheproteinandtranscriptchanges ... 36

2.5. GOfunctionalclassification...36

∗ Correspondingauthorsat:ETHZurich,LFWE18,Universitaetstrasse2,8092Zurich,Switzerland. E-mailaddresses:kbaerenfaller@ethz.ch(K.Baerenfaller),wgruissem@ethz.ch(W.Gruissem).

1 Currentaddress:INRA,UMREcologieetEcophysiologieForestière,F-54280Champenoux,France.

2 Currentaddress:UniversitédeLorraine,UMREcologieetEcophysiologieForestière,BP239,F-54506Vandoeuvre,France.

3 Currentaddress:NUIGalway,PlantSystemsBiologyLab,PlantandAgriBiosciencesResearchCentre,BotanyandPlantScience,Galway,Ireland. 4 Currentaddress:Albert-Ludwigs-UniversityofFreiburg,FacultyofBiology,D-79104Freiburg,Germany.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpb.2015.07.001

3. Resultsanddiscussion...36

3.1. LDacceleratesArabidopsisgrowthandincreasesindividualleafareabutdecreasesrosettearea...36

3.2. Successivecellularstagesofleaf6developmentareafunctionofphotoperiod...36

3.3. Photoperiodaffectsindividualleafexpansioninthecontextofwholerosettedevelopment...37

3.4. Experimentaldesignforassessingmolecularchangesduringleafdevelopment...37

3.5. Photoperiodaffectstheamountanddiurnalturnoverofcarbonreserves...37

3.6. DiurnaltranscriptlevelchangesarelesspronouncedinaLDphotoperiod...38

3.7. DiurnaltranscriptfluctuationsareshiftedinLDandmostpronouncedforstressresponse...38

3.8. Photoperiodandgrowthbehaviourhavespecifictranscriptsignatures...40

3.9. Transcriptsregulatedbyphotoperiodbelongtospecificfunctionalcategories...40

3.9.1. RNAprocessingmechanismsdifferdependingonphotoperiodlength...41

3.9.2. FlavonebiosynthesisisenhancedintheLDphotoperiod...41

3.9.3. LightandhormonesignallingdifferbetweenSDandLD...41

3.9.4. SDincreasestranscriptlevelsforsugartransportandphotosystemproteins...42

3.10. ProteinsthatdifferbetweenSDandLDcanmainlybeattributedtodifferencesingrowth...42

3.11. Floweringgeneshavephotoperiod-specifictranscriptsignaturesinleaves...42

3.12. AtGRP7protein,butnottranscript,ismorehighlyexpressedinLD...43

4. Conclusions...43

Conflictsofinterest...43

Acknowledgements ... 43

AppendixA. Supplementarydata...43

References...43

1. Introduction

Plantsaslight-dependent,autotrophicorganismshaveadapted

totheregularlight–darkcyclesresultingfromtherotationofthe

earth.Thelengthofthelightperiod,orphotoperiod,dependson

thelatitudeandtime oftheyear.Plantsmustadjusttochanges

inday-lengthtooptimizegrowthinvaryingphotoperiodlengths.

Althoughthisrequirestightcontrolofphysiologicalandmolecular

processes,theunderlyingregulatorymechanismsarestillpoorly

understood.It is now wellestablished that thecircadian clock

synchronizesmetabolismwiththechangingphotoperiods[1–4].

Photoperiodlength affects netdaily photosynthesis and starch

metabolism[5,6]andadjustsseasonalgrowth[7–9].However,the

molecularintegrationofphotoperiod,clockandmetaboliccontrol

duringleafdevelopmentremainsachallengingproblem.

Arabidopsis is a facultative long-day plant whose flowering

iscontrolledbythephotoperiodpathway[7,8,10,11]inconcert

withmolecular,hormonalandenvironmentalsignals[10].

Interac-tionsbetweenthecircadianclockandphotoperiodlengthduring

vegetative growthaffectleaf number and size,as wellas their

morphologicalandcellularproperties[12–16].Plantsinwhichthe

vegetativetofloralgrowthtransitionisacceleratedbyincreasing

day-lengthor repressionofregulatorygeneshave fewerleaves,

increasedsingleleafareas,anda higherepidermal cellnumber

inindividualleavescomparedtolatefloweringplants[12,15,16].

Whiletheseadaptationstophotoperiodarewelldocumentedat

thephenotypiclevel,littleisknownabouthowconcerted

regula-tionofphotoperiod-dependentgeneexpressionandproteinlevels

isachieved duringdiurnal cyclesandat differentstages ofleaf

development.

We therefore asked how phenotypic changes are related to

molecularprofilesinasingleleafofArabidopsisplantsgrowingin

along-day(LD;16hlight,8hdark)orshort-day(SD;8hlight,16h

dark)condition.Thesetwophotoperiodscauseconsistent

pheno-typicchangesinthenumberandmorphologyofsuccessiveleaves

ontherosette[12,16].Becausesizeandshapeofsuccessiveleaves

varyduringArabidopsisdevelopment[17]wedecidedtofocusthe

analysisonleafnumber6,whichisthefirstadultleafofthe

Ara-bidopsis(Col-4)rosetteinshort-dayconditions.Leaf6wasused

previouslytogeneratemoleculardataforArabidopsisgrowninSD

[18].Togain insightsintothemolecularpatternunderlyingthe

phenotypicchangesbetweenphotoperiods,wethereforeanalyzed

transcriptandproteinlevelsofleafnumber6growninLDatfour

developmentalstages,bothattheendoftheday(EOD)andendof

thenight(EON).Wethencomparedthedatawiththe

correspond-ingpreviouslyestablishedmoleculardataforleaf6ofArabidopsis

growninSDeitherunderoptimalwatering(SOW)ora40%water

deficit(SWD)[18].Integrationand comparativeanalysesof the

quantitative proteomicsand transcriptomics datarevealed that

fewergeneshavesignificantdiurnaltranscriptlevelfluctuations

inLDthanSD.Transcriptsandproteinswithsignificantlydifferent

levelsinSDandLDvalidatethehypothesisthatashort

photope-riodrequiresatightenergymanagement,whichisrelaxedinalong

photoperiod.

2. Materialandmethods

2.1. Plantmaterial,leaf6androsettegrowthmeasurements

ArabidopsisthalianaaccessionCol-4(N933)plantsweregrown

inagrowthchamberequippedwiththePHENOPSISautomaton[19]

asdescribedpreviously[18]withtheexceptionthatdaylengthin

thegrowthchamberwasfixedat16h.Inbrief,seedsweresownin

potsfilledwithamixture(1:1,v/v)ofaloamysoilandorganic

com-postatasoilwatercontentof0.3gwater/gdrysoilandjustbefore

sowing10mlofamodifiedone-tenth-strengthHoaglandsolution

wereaddedtothepotsurface.After2daysinthedark,daylength

inthegrowthchamberwasadjustedto16hat∼220mol/m2/s

incidentlightintensityatthecanopy.Plantsweregrownatanair

temperatureof21.1◦Cduringthelightperiodand20.5◦Cduring

thedarkperiodwithconstant70%humidity.Duringthe

germina-tionphasewater wassprayed onthesoiltomaintainsufficient

humidityatthesurface.Beginningatplantgermination,eachpost

wasweighedtwiceadaytocalculatethesoilwatercontent,which

wasadjustedto0.4gwater/gdry soilbytheadditionof

appro-priatevolumesofnutrientsolution.Theexperimentwasrepeated

independentlythreetimesandeachleaf6samplewaspreparedby

bulkingmaterialfromnumerousplants.Thefrozenplantmaterial

wassenttotheMPIinGolm,whereitwasgroundandaliquotted

usingacryogenicgrinder(GermanPatentNo.8146.0025U1).

Growth-relatedtraitsofleaf6atsingleleafandcellularscales

weremeasuredas described [20]. Fiverosettes wereharvested

anddissectedevery2–3daysduringeachexperiment.Leaf6area

(×160)glassforleavessmallerthan2mm2orwithascannerfor

largerones.Anegativefilmoftheadaxialepidermisofthesameleaf

6astheonemeasuredinsurfacewasobtainedafterevaporationof

avarnishspreadonitssurface.Theseimprintswereanalyzedusing

amicroscope(LeitzDMRB;Leica)supportedbytheimage-analysis

softwareOptimas.Meanepidermalcelldensity[cellsmm−2]was

estimatedbycountingthenumberofepidermalcellsintwozones

(atthetipandbase)ofeachleaf.Totalepidermalcellnumberinthe

leafwasestimatedfromepidermalcelldensityandleafarea.Mean

epidermalcellarea[m2]wasmeasuredfrom25epidermalcells

intwozones(atthetipandbase)ofeachleaf.

Forrosettegrowthmeasurements,ateachdateofharvestall

leaveswithanarealargerthan 2mm2 fromfive rosetteswere

imagedwithascanner.Thenumberofleaveswascountedandtotal

rosetteareawascalculatedasthesumofeachindividualleafarea

measuredonthescanwiththeImageJsoftware.

2.2. Carbohydratedeterminations

Starch,glucose,fructoseandsucrosecontentweredetermined

byenzymaticassaysinethanolextractsof20mgfrozenplant

mate-rialasdescribedinCrossetal.[21].Chemicalswerepurchasedas

inGibonetal.[22].Assayswereperformedin96wellmicroplates

usingaJanuspipettingrobot(PerkinElmer,Zaventem,Belgium).

AbsorbancesweredeterminedusingaSynergymicroplatereader

(Bio-Tek,BadFriedrichshall,Germany).Foralltheassays,two

tech-nicalreplicatesweredeterminedperbiologicalreplicate.

2.3. TilingarraytranscriptdataandquantitativeiTRAQ

proteomicsdata

Geneexpressioninleavesofthefourdevelopmentalstagesand

atthetwodiurnaltimepointsinthelongdayoptimalwater(LD)

experimentandinareferencemixedrosettesamplewasprofiled

asdescribedpreviously[18]usingAGRONOMICS1microarrays[23]

andanalyzedusinga TAIR10CDFfile[24].Alllog2-transformed

sample/referenceratios without p-value filtering were used in

theanalyses.Microarrayrawandprocesseddataareavailablevia

ArrayExpress(E-MTAB-2480).

Proteins in the same sampleswere quantified using the

8-plexiTRAQisobarictaggingreagent[25,26]asdescribedindetail

previously [18] according to the labelling scheme in

Support-ing Table S5. The resulting spectra were searched against the

TAIR10proteindatabase[27]withconcatenateddecoydatabase

andsupplementedwithcommoncontaminantswithMascot

(Mas-cotScience,London,UK).Thepeptidespectrumassignmentswere

filteredforpeptideunambiguityinthepep2prodatabase[28,29].

Acceptingonlyunambiguouspeptideswithanionscoregreater

than 24 and an expect value smallerthan 0.05 resulted in 70

979assignedspectraataspectrumfalsediscoveryrate(FDR)of

0.07%.Quantitative information for all reporter ionswas

avail-ablein50 947of thesespectraleadingtothequantification of

1788proteinsbasedon6178distinctpeptides(SupportingTable

S6).Themassspectrometryproteomicsdatahavebeendeposited

to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.

proteomexchange.org)viathePRIDEpartnerrepository[30]with

thedatasetidentifierPXD000908 and DOI10.6019/PXD000908.

The data are also available in the pep2pro database at www.

pep2pro.ethz.ch

Allproteomeandtranscriptomeabundancemeasuresforthe

LDexperimentwereintegratedwithintheexistingAGRON-OMICS

database (LeafDB) [18]. A searchable web-interface containing

theseintegrateddatasetsisavailableathttps://www.agronomics.

ethz.ch/

2.4. Statisticalanalysesoftheproteinandtranscriptchanges

Thestatisticalanalyticalmethodswereperformedasdescribed

previously[18]subjectingthelog2-transformedsample/reference

ratios to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) treating stage (S)

and day-time(ND) asmain effects followedby correctionwith

Benjamini-Hochberg[31].TranscriptsandproteinswithapGlobal

(p-value for an overall global change)<0.05 and a maximum

fold-change>log2(1.5) were considered to change significantly

(SupportingTablesS7andS8).Forasignificantdifferencebetween

EODandEONweadditionallyrequiredpND(p-valueforthediurnal

change)<0.05.Thecomparisonoftheproteinandtranscriptlevels

betweentheLD andthetwoshortday(SOWandSWD)

exper-imentsreportedpreviously wasperformedwitha pairedt-test

comparingthevaluesforthe8time-pointsbetweentwo

experi-mentscorrectedwithBenjamini-Hochberg[31]takingintoaccount

allnon-plastidencodedtranscriptswithoutp-valuefiltering.All

statisticalanalyseswereperformedusingR[32].

2.5. GOfunctionalclassification

Assignmentofproteinandtranscriptfunctionalcategorieswas

basedontheTAIRGOcategoriesfromaspectbiologicalprocess

(ATH GO GOSLIM20130731.txt)asdescribedpreviously[18].

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. LDacceleratesArabidopsisgrowthandincreasesindividual

leafareabutdecreasesrosettearea

Whenplottedagainsttimefromleafinitiationtofullexpansion,

leaf6areaincreasedmorerapidlyandreacheditsfinalsize

ear-lierandwas50%largerinLDthaninSD(Fig.1A).Thedynamicsof

cellproductionandexpansionintheupperepidermisofleaf6

indi-catesthatbothcellnumberandcellsizeincreasedmorerapidlyand

reachedtheirfinalvaluesearlierinLDthaninSD(Fig.1B,C).Thus,

photoperiodhasapronouncedeffectonthetimingofleaf

develop-mentbecausecelldivision,cellexpansionandleafexpansionwere

fasterinLDthanSDandceasedearlier.

Similartothefastergrowthofleaf6thewholerosetteleafarea

andleafnumberinitiallyincreasedfasterinLDthanSD(Fig.2A,B).

However,laterindevelopmentanddespitetheincreasedindividual

leafsizeatthefullyexpandedstage(Fig.1A),thewholerosettearea

wassmallerinLDthaninSD.Thiswastheresultofasmallerfinal

numberofrosetteleavesthatwereproduced(Fig.2A).

3.2. Successivecellularstagesofleaf6developmentarea

functionofphotoperiod

Becauseleaf6growthwasacceleratedinthelongphotoperiod

andstages2–4ofleafdevelopmentwerereachedearlierthanin

theshortphotoperiod(Fig.1), biologicalsamplesofleaf6were

harvestedatfourdevelopmentstagescorrespondingtotransitions

associatedwithwell-definedcellularprocesses[18].Thestage1

leafhasmaximum relative areaand thickness expansionrates,

stage2and3leaveshavemaximumanddecreasingabsolutearea

andthicknessexpansionrates,respectively,andinthestage4leaf

expansionends[18].Samplingatdefinedstagesallowsarobust

leafscalecomparisonofphotoperiodeffectsonleafdevelopment

despitedifferentgrowthratesindifferentexperiments.Wefound

thatstage1correspondstothephaseofrapidcelldivisionaround

day7or8afterleafinitiationinbothphotoperiods.Mostofcell

divisionhadceasedatstage2,whichwasaroundday11afterleaf

initiationinLDandday14inSD.Stage3isthephaseofdecreasing

cellexpansionratearound14daysafterleafinitiationinLDandday

Fig.1. KinematicexpansionphenotypesofleavesharvestedforprofilingintheSD (blue)andLD(red)experiments.Changesovertimeinleaf6area(A),meancell numberinleaf6adaxialepidermis(B)andmeancellareainleaf6adaxialepidermis (C).DataaremeanandSDvalues,n=5.Theincreaseofleafarea,cellnumberand cellareaaredescribedbysigmoidcurvesfollowingtheequations:y=A/[1+e (-(X-X0)/B)].Themediandateofthe4harvesttimesarepresentedbyverticallinesfor theSD(bluedotted)andLD(reddot-dashed)experiments.Leaf6initiationoccurred ataroundday12aftersowinginSDandday10inLD.

correspondingtoaroundday21afterleaf6initiationinLDandday

30inSD.

3.3. Photoperiodaffectsindividualleafexpansioninthecontext

ofwholerosettedevelopment

Becausephotoperiodlengthaffectedboth theprogression of

individualleafstagesandwholeplantdevelopment,thefourleaf6

developmentalstagesdidnothavethesamestatuswithregardto

wholerosettedevelopmentinLDandSDplants.Leaf6expansion

inSDwascompletebeforethefinalnumberofrosetteleaveswas

reached,whereasinLDmorethan50%ofleaf6expansionoccurred

afterbolting.Thefloraltransitionattheshootapexoccursseveral

daysbeforebolting,typicallyat10–12daysaftergerminationin

LD[33].Leaf6wasinitiatedat10daysaftersowing,andtherefore

almostallitsgrowthoccurredafterthefloraltransitionattheshoot

apex.

Atstage1inLD,leaf6arearepresentedapproximately5%ofthe

wholerosettearea.Thisproportionincreasedto12–15%during

stages2and3andatstage4declinedtoaround10%.Incontrast,

theproportionofleaf6areacomparedtowholerosetteareaat

Fig.2. Kinematicexpansionphenotypesofwholerosetteleafgrowthofplants har-vestedforleaf6profilingintheSD(blue)andLD(red)experiments.Changesover timeinthenumberofrosetteleaves(A)andwholerosettearea(B).Changesover timeoftheproportionofwholerosetteareacoveredbyleaf6areaispresentedin (C).Theindicatedtrendlinesrepresentpredictionsfromalocalpolynomial regres-sionfitting(loess).The4datesofharvestarepresentedbyverticallinesfortheSD (bluedotted)andLD(reddot-dashed)experiments.

stage4waslessthan5%inSD,confirmingthatleaf6reachesits

smallerfinalsizeinSDbeforewholerosetteexpansionwas

com-plete(Fig.2C).

3.4. Experimentaldesignforassessingmolecularchangesduring

leafdevelopment

Toquantitateproteinandtranscriptlevelsduringthegrowth

ofasingleArabidopsisleafweharvestedleaf6fromplantsgrown

inLDattheendoftheday(EOD)andendofthenight(EON)at

thefoursuccessivestagesofdevelopmentdefinedabove.Proteome

andtranscriptomeprofilingdata,aswellastheamountsofstarch

andsolublesugarswereobtainedfrompooledsamplesofleaf6of

threeindependentbiologicalexperiments.Wethenassessedhow

themolecularprofilesinsingleleavesatprecisestagesof

devel-opmentfromplantsgrowninLDdifferfromleaf6growninSDby

comparingthemtotheSDoptimalwatering(SOW)and40%water

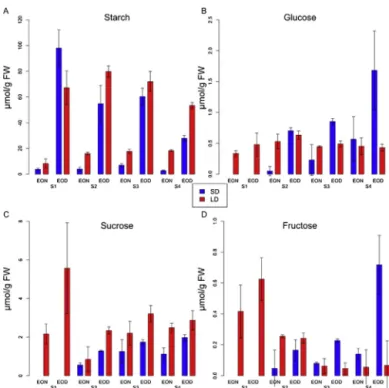

Fig.3.Theamountsof(A)starchandthesolublesugars(B)glucose,(C)sucroseand (D)fructoseing/gFWandtheirstandarddeviationsatEONandEODatthefour leaf6developmentalstagesinSD(blue)andLD(red).

3.5. Photoperiodaffectstheamountanddiurnalturnoverof

carbonreserves

Starchisthemaincarbonreserveforenergyrequirements

dur-ingthenightinArabidopsisandrepresentedabout80–93%ofthe

carbohydratesmeasuredatEODinLDandSD(Fig.3).InLD-grown

plants,theamountofstarchatEODwassimilaratallfour

devel-opmentstages.Althoughstarchalsodecreasedduringthenight

inLDplants,considerablylargeramountsofstarchremainedat

EON,especiallyatstages2,3and4(Fig.3A).InSDadifferent

pat-ternwasfound.ThehighestamountofstarchatEODwasfound

forstage1,withlowerlevelsinstages2,3and,especially,stage

4.Further,inSD,mostofthestarchthataccumulatedatEODwas

consumedduringthenightatalldevelopmentalstages.InLD,the

levelsofglucose,sucroseandfructoseweresimilaratEODandEON

foralldevelopmentalstages,withtheexceptionofstages1and2

forsucrose,wherethelevelswerehigheratEODthanEON.Glucose

levelsinLDweresimilaratalldevelopmentalstages,butfructose

andsucrosewerehighestforstage1.Incontrast,majordifferences

werefoundinSD.First,glucose,fructoseandsucroselevelsinSD

wereconsistentlyhigheratEODthanEON,aspreviouslyreported

forfullrosettes[6].Second,thehighestlevelsofglucose,fructose

andtosomeextentsucroseweredeterminedforstage4atEOD.

Third,sucroselevelsforalldevelopmentalstagesandharvesttimes

wereconsistentlylowerinSDthanLD,aspreviouslyreportedfor

fullrosettes[6](Fig.3B–D).Together,thedatarevealthatin

Ara-bidopsisphotoperiodlengthhasamajorinfluenceonthemetabolic

statusoftheleafduringbothdevelopmentandthediurnalcycle.

3.6. DiurnaltranscriptlevelchangesarelesspronouncedinaLD

photoperiod

Toaccountfortheobservedphenotypicandmetabolic

differ-encesbetweenSDandLDweanalyzedquantitativeproteinand

transcriptdataindetail.WefirstperformedaPrincipal

Compo-nentAnalysis(PCA)toestimatethemainfactorsthatdetermine

changesintranscriptandproteinlevelsinLD.Themain

contribu-tiontothevarianceinthetranscriptdatainthefirsttwoprincipal

componentsisthedifferencebetweenstage1andthelaterstages

2–4,whichaccountedforover60%ofthetotalvariance(Fig.4A).

TheEODandEONsamplesareseparatedonlyinthethird

princi-palcomponent,whichaccountedforabout8%ofthetotalvariance

(Fig.4B).ThisisincontrasttoaPCAofthetranscriptsinSD

condi-tions,wherethetimeofharvestwasthemaincontributiontothe

variationinthedatainthefirstandsecondprincipalcomponents

[18].AssessingthedifferenceintranscriptlevelsbetweenEONand

EONrevealedthatinLDonly21.2%ofalltranscriptsshowed

signifi-cantdiurnaltranscriptlevelfluctuations,incontrastto50.3%inthe

SOWand43.1%intheSWDconditions.Thus,inadditionto

metabo-litechanges,theLDphotoperiodalsohasaconsiderableimpacton

diurnalmRNAexpressionpatterns.Fortheproteindata,the

dif-ferencebetweenthedevelopmentalstagescontributesmosttothe

variationinthedata(Fig.4C),asobservedpreviouslyinSD[18].

3.7. DiurnaltranscriptfluctuationsareshiftedinLDandmost

pronouncedforstressresponse

TranscriptsthatchangedsimilarlybetweenEODandEONboth

inLDandSDincludedthoseencodingthecentralclockproteins

Fig.4.PrincipalComponentAnalysisoftranscriptandproteinprofilesinleaf6growninLD.(A)Firstandsecondprincipalcomponentand(B)firstandthirdprincipal componentinthetranscriptdata,and(C)firstandsecondprincipalcomponentintheproteindata.Thenumbersindicatethegrowthstages1to4andareinblueforthe EONsamplesandinredfortheEODsamples.

Fig.5.(A)ThenumberoftranscriptswithdifferentialdiurnalfluctuationsbetweenSDandLD.(B)ForallthetranscriptswithdifferentialdiurnalfluctuationsbetweenSDand LD,and(C-H)forthetranscriptsinthedifferentsub-categoriesdepictedin(A),thehistogramsrepresentthefrequencyofthenumberoftranscriptswithanexpressionpeak atagivenZTasdeterminedinEdwardsetal.[34].TheZTherecorrespondstothetimeincontinuouslightsincethelastdawnafterplantshadbeenentrainedto12h/12h light/darkcyclesfollowedbyonedayincontinuouslight,andtheexpectedlightanddarkperiodsareindicatedbywhiteandblackbars,respectively.

LATEELONGATEDHYPOCOTYL 1(LHY,AT1G01060),CIRCADIAN

CLOCK ASSOCIATED1 (CCA1, AT2G46830)and TIMING OF CAB

EXPRESSION1(TOC1,AT5G61380).However,asexpectedfromthe

resultsofthePCAanalysis,manymoretranscriptsshoweda

signif-icantchangebetweenEODandEONinSDthaninLD.Wedefined

transcriptstochangeonlyinSDwhentheyhadsignificantly

dif-ferentlevelsbetweenEODandEONinSOWandSWD,butnotin

LD(5238transcripts),andtranscriptstochangeonlyinLDwhen

theyhadsignificantlydifferentlevelsbetweenEODandEONinLD,

butnotinSOWorSWD(835transcripts)(Fig.5A;SupportingTable

S1).Tofurtherexaminethedifferencesinthediurnalfluctuations

betweenSDandLDweusedEONasreferencepointcorresponding

toZeitgeberTime(ZT,hoursafterdawn)–1inbothexperiments.We

thenassessedwhichtranscriptsweresignificantlyhigherorlower

attherespectiveEODcomparedtothereferencepointonlyinSD,

oronlyinLD(Fig.5,SupportingTableS1).Foralltranscriptswith

differentialdiurnalfluctuationsbetweenSDandLDweexamined

whethertheyscoredrhythmicbyCOSOPTinthefree-runningstudy

conductedbyEdwardsetal.[34].Forthosethatwererhythmicwe

plottedtheZeitgeberTime(ZT)peaksdeterminedinEdwardsetal.

[34](Fig.5B–H).TheZTpeaksoftherhythmictranscriptsthatare

loweratEODonlyinSDandhigheratEODonlyinLDpeakinthe

secondhalfofthesubjectivenightaroundZT43-44.Transcriptsthat

arehigheratEODonlyinSDpeakaroundZT33–37corresponding

tothesubjectivedusk,whilethosethatareloweratEODonlyinLD

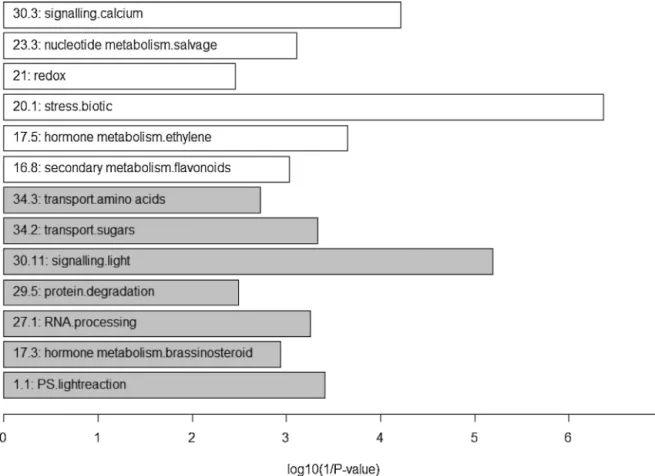

Fig.6.MapMancategoriesthatareover-representedinLD(white)orSD(grey).TheMapManbinswithP-value<0.01areindicatedandthelengthofthebarcorrespondsto thelog-transformedMapMancategoriesthatareover-representedinLD(white)orSD(grey).TheMapManbinswithP-value<0.01areindicatedandthelengthofthebar correspondstothelog-transformedp-value−1.

harvestattherespectiveEODinSDandLDphotoperiodscanaffect

therelativeabundancedifferencebetweenEODandEONfor

tran-scriptspeakingduringthenight,thisisnotthecasefortranscripts

withZTpeaksintheafternoonorearlynight(SupportingFig.S1).

Thedifferentpatternofthesetranscriptsthereforesuggestsashift

intheirdiurnalexpression.Thefunctionalcategorisationagainst

GOBiologicalProcessofthetranscriptshigheratEONonlyinLD

gaveasthetopcategoryresponsetochitin(p-value<1−30).Thelist

of23transcriptsthataccountforthisover-representationcontains

14transcriptionfactorsaccordingtotheAGRISwebsite[35]

(Sup-portingTableS2),andfourofthemarescoredrhythmicwithZT

peaksinthelateafternoon.Together,thissuggeststhatthe

expres-sionpatternsofspecifictranscripts,especiallyfortranscriptslinked

tobioticstressresponse,arechangedinresponsetolightandthe

expectedlengthofthenight.

3.8. Photoperiodandgrowthbehaviourhavespecifictranscript

signatures

Thedifferencesinthediurnaltranscriptaccumulationbetween

SDandLDpromptedustofurtherexaminethetranscriptsthatare

differentiallyexpressedbetweenLDandSD.Weconsideredthose

transcriptstochangeinaphotoperiod-specificmannerthatwere

significantlydifferent(p-value<0.05inapairedt-test,average

fold-change>1.5)intheLDexperimentcomparedtoboththeSOWand

SWDexperiments.Atotalof3469transcriptsfulfilledthesecriteria

with1954beinghigherinLDand1515higherinSD(Supporting

TableS3).

AsplantsgrowfasterinLDthanSOWandSWDconditions,itcan

beexpectedthatsomeofthedifferencesbetweenthetwo

photope-riodswillbeduetotheirdifferentgrowthbehaviours.Comparing

thetwoSDexperimentswehadalreadyfoundthatthetranscript

levelsofproteinsassignedtoGOcategorydefenceresponseto

fun-gusandthosesupportingfastgrowth,suchasproteinsinvolved

inribosomebiogenesisandtranslation, arereduced inleaf6by

waterdeficit[18].Todistinguishbetweeneffectscausedby

dif-ferentgrowthratesandthosespecificforlongdayconditions,we

definedsetsofgrowth-specifictranscriptsbasedonthegradual

increaseingrowthratefromSWDtoSOWandtheLDexperiment.

Wehypothesisedthattranscripts,whichaccumulatetodifferent

levelsbetweenSDandLDandalsoshowasignificantdifferencein

accumulationbetweentheSWDandSOWconditions,arelikelyto

berelatedtogrowth.Applyingthesecriteriawefound134

tran-scriptsthataremosthighlyexpressedinLDand38transcriptsthat

arehighestinSWDconditions(SupportingTableS3).Transcripts

thatarehighestinLDandthereforemightbeassociatedwithfaster

growthareover-representedinvariousresponsepathways,with

responsetochitin,defenceresponsetofungusandresponseto

mechan-icalstimulusasthetopthreecategories.TheGOprocessesthatare

over-representedinthetranscriptshighestintheSWDplantsare

nitrileandprolinebiosyntheticprocess,aswellasphotosynthesis,

con-sistentwithatightenergymanagementinashortphotoperiodand

reducedwatercondition.

3.9. Transcriptsregulatedbyphotoperiodbelongtospecific

functionalcategories

TranscriptsthatweresignificantlyhigherinSDorLD

(Support-ingTableS3) werecategorisedusingMapMan [36]and TAIR10

mapping (AthAGILOCUSTAIR10Aug2012). Over- and

under-representationwasassessedseparatelyforthetranscriptshigherin

Table1

ProteinswithasignificantchangebetweentheLDexperimentandSOW.ProteinsthatwereinadditionsignificantlyincreasedordecreasedintheLDexperimentcompared toSWDareinbold.

Proteinssignificantlyhigherinlongdayconditions

AT1G75040 pathogenesis-relatedgene5,PR5

AT1G75750 GAST1proteinhomolog1

AT2G19730 RibosomalL28eproteinfamily

AT2G21660 cold,circadianrhythm,andrnabinding2,CCR2,GRP7 AT2G29350 senescence-associatedgene13

AT2G45790 phosphomannomutase,PMM

AT3G57260 beta-1,3-glucanase2,ATBG2,ATPR2,BGL2,PR2 AT3G59760 O-acetylserine(thiol)lyaseisoformC

AT4G17830 PeptidaseM20/M25/M40familyprotein AT4G22670 HSP70-interactingprotein1

AT4G32915 FUNCTIONSIN:molecularfunctionunknown;INVOLVEDIN:regulationoftranslationalfidelity AT4G36810 geranylgeranylpyrophosphatesynthase1,GGPS1,GGPPS11

AT5G39570 FUNCTIONSIN:molecular functionunknown;INVOLVEDIN:biologicalprocessunknown;LOCATEDIN:cytososol Proteinssignificantlylowerinlongdayconditions

AT1G54010 GDSL-likeLipase/Acylhydrolasesuperfamilyprotein AT1G76100 plastocyanin1,PETE1

AT2G22230 Thioesterasesuperfamilyprotein AT2G42530 coldregulated15b,COR15B AT2G42540 cold-regulated15a,COR15A AT3G09260 Glycosylhydrolasesuperfamilyprotein AT4G29680 Alkaline-phosphatase-likefamilyprotein AT5G10540 Zincin-likemetalloproteasesfamilyprotein

AT5G15970 stress-responsiveprotein(KIN2)/stress-inducedprotein(KIN2)/cold-responsiveprotein(COR6.6) AT5G51720 2iron,2sulfurclusterbinding

AT5G54160 O-methyltransferase1

ofmeasuredtranscriptswiththenumberthatwouldbeexpected bychance.Fig.6showstheMapManbinswithp-value<0.01and

theAGIsofthegenesinthesecategoriesarelistedinSupporting

TableS4.

3.9.1. RNAprocessingmechanismsdifferdependingon

photoperiodlength

Among the genes for transcripts that have different levels

betweenSD andLDwefoundfewerthanexpectedthatencode

proteinsfortranslation(bin29.2)(p<2.05e−11inaFisher’sexact

test).Thisisinagreementwiththefindingthatribosome

abun-dance does not change between SD and LD grown plants [6].

However,genesinvolvedinRNAprocessingareover-represented

inSD(Fig.6),whilegenesforsmallnucleolarRNAs(snoRNAs)are

over-representedinLD(4.25e−6inaFisher’sexacttest)because

14of45snoRNAsrepresentedonthetilingarrayaresignificantly

more highly expressedin LD. snoRNAsassociate with proteins

toformfunctionalsmallnucleolarribonucleoproteincomplexes

(snoRNPs),whichareinvolvedintheprocessingofprecursorrRNAs

inthenucleolusrequiringexo-andendonucleolyticcleavagesas

wellasmodifications.Thesemodificationsarethoughttoinfluence

ribosomefunction[37].ThedifferentialexpressionofsnoRNAsin

SDandLDconditionsmightreflectaspecificbutcurrentlyunknown

mechanismofadjustingtranslationtotheprevalentphotoperiod

conditions.

3.9.2. FlavonebiosynthesisisenhancedintheLDphotoperiod

Transcriptsthat arehigher inLD areoverrepresented in bin

secondarymetabolism.flavonoids(Fig.6).Flavonoidsareplant

sec-ondary metabolites withbroad physiological functions [38]. Of

thegenesinthiscategory,fiveencodeenzymesintheKEGG[39]

pathway flavonoid biosynthesis, namely TRANSPARENTTESTA 4

(CHS/TT4,AT5G13930),TT5(AT3G55120),F3H/TT6(AT3G51240),

TT7 (AT5G07990) and FLAVONOL SYNTHASE (FLS, AT5G08640)

(SupportingFig.S2).Theseenzymesarerequiredforthe

biosyn-thesis of the three major flavonols quercetin, kaempferol and

myricetin,althoughtheenzymecatalysingthelaststepofmyricetin

productionhasnotyetbeenidentifiedinArabidopsis(Supporting

Fig.S3).Thetranscriptlevelsfortheseenzymesareallincreasedin

LDascomparedtoSDbutgenerallydecreaseduringleaf6

develop-ment(SupportingFig.S4).TT5andTT6/F3Hproteinsweredetected

inLD.TT5proteinlevelsdecreasesignificantlyduringdevelopment

inLDbuttheproteinwasdetectedinallthreeexperimental

condi-tions(SOW,SWDandLD).Transcriptlevelsofflavonoidpathway

geneswerereportedtobeup-regulatedinleavesofsweetpotato

grown inLD that have highconcentrations ofkaempferol [40].

Kaempferolfunctionsasanantioxidantinchloroplasts[41].Higher

transcriptlevelsfortheenzymesintheflavonolbiosynthesis

path-wayinLDthereforecorrelatewellwiththeover-representationof

thebinredoxinLD.Thetranscriptlevelsforenzymesinflavonoid

biosynthesispathwaysinvolvedinresponsetoexcessUVlightor

highlightstress,suchasanthocyaninbiosynthesis,arenothigher

inLDascomparedtoSD.Thisconfirmsthatunderour

experimen-talconditionstheLDphotoperiodisnottriggeringastressresponse

thatwouldrequireenhancedphotoprotection.

3.9.3. LightandhormonesignallingdifferbetweenSDandLD

Plant hormones coordinate developmental processes and

growth through converging pathways [42,43]. We therefore

expectedthatseveralofthegeneswhosetranscriptsaccumulate

todifferentlevelsbetweenSDandLDencodeproteinsinvolvedin

hormonemetabolismandsignalling(SupportingFig.S5).Thebin

hormonemetabolism.ethyleneisover-representedinLDandthelist

ofgenesannotatedtothisbinthathaveincreasedtranscriptlevels

inLDincludes10genesencodingdifferentETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE

ELEMENTBINDINGFACTOR(ERF)proteins.ERFsfunctionindefence

responseandregulatechitinsignalling[44,45].TwooftheseERFs,

DREBANDEARMOTIFPROTEIN1(DEAR1;AT3G50260)andERF6

(AT4G17490),belongtothetranscriptionfactorsthathavehigher

transcriptlevelsatEONonlyinLDandareassignedtoresponseto

chitin(SupportingTableS2).

Ethylenebiosynthesisisrestrictedbythephotoreceptor

phy-tochromeB(PHYB;AT2G18790)[46].PHYBtranscriptlevelsare

decreasedinLDascomparedtoSD,whichcorrelateswithincreased

ethylenebiosynthesisinLD.InadditiontoPHYB,othergenes

encod-ingphytochromessuchasPHYA(AT1G09570)andgenesencoding

proteinsaremorehighlyexpressedinSD,resultinginthe

over-representationofbinsignalling.light(SupportingTableS4).

Photoperiod can be integrated with growth and time to

flowering through regulation of the brassinosteroid hormone

pathway [47]. It was therefore unexpected that bin hormone

metabolism.brassinosteroidwasover-representedinSD,asplants

inSDgrowmoreslowlyandflowerlater.However,themRNAs

withhigherlevelsinSDassignedtothisbinalsoincludethemRNA

forcytochromeP450CYP734A1(AT2G26710).CYP734A1converts

activebrassinosteroidsintotheirinactiveforms[48]andtherefore

actsasanegativeregulatorofbrassinosteroidsignalling.Thus,the

over-representationofthebinhormonemetabolism.brassinosteroid

doesnotimplyincreasedbrassinosteroidsignalling.Infact,theonly

brassinosteroidsignalling-relatedmRNAwithhigherlevelsinLD

encodesBES1/BZR1-LIKEPROTEIN3(BEH3,AT4G18890),whichis

atranscriptionfactorthatishomologoustoBES1/BZR1,apositive

regulatorofbrassinosteroidsignalling[49].

3.9.4. SDincreasestranscriptlevelsforsugartransportand

photosystemproteins

TranscriptsthataresignificantlyhigherinSDthanLDencode

twelvemembersofthemonosaccharidetransporter(MST)(-like)

genefamily[50]andtheSUCROSE-PROTONSYMPORTER9(SUC9,

AT5G06170). Accordingly, the bin sugar.transport is

overrepre-sentedin SD(Fig.6,SupportingTableS4).The membersofthe

MST(-like) gene family are classified into seven distinct

sub-familiesandhaverolesinbothlong-distancesugarpartitioningand

sub-cellularsugar distribution[50].POLYOL/MONOSACCHARIDE

TRANSPORTER2(PMT2,AT2G16130)andSUGARTRANSPORTER

1(STP1, AT1G11260)arelocatedin theplasma membrane and

weresuggestedtoimportmonosaccharidesintoguardcells

dur-ingthenightandfunctioninosmoregulationduringtheday[51].

TheMST(-like)genefamilymembersinvolvedinsub-cellularsugar

distributionincludetheplastid-localisedPLASTIDICGLC

TRANSLO-CATOR(PGLCT,AT5G16150),which contributestotheexportof

themainstarchdegradationproductsmaltose andglucosefrom

chloroplasts[52], and six proteinsencoded by theAtERD6-like

genesub-familythatarelocatedinthevacuolemembrane.AtERD6

homologs are thought to export sugars from the vacuole

dur-ingconditionswhenre-allocationofcarbohydratesisimportant,

includingsenescence,wounding,pathogenattack,C/Nstarvation

anddiurnalchangesintransientstorageofsugarsinthevacuole

[50].Theincreasedtranscriptexpressionofgenesforvarioussugar

transportersinSDisconsistentwiththedifferentamountand

diur-nalturnoverofsugarlevelsinSDascomparedtoLD(Fig.3)and

indicatesthatlong-distanceandsub-cellularsugarpartitioningis

increasedinshorterilluminationperiods.

ThebinPS.lightreactionissignificantlydifferentbetweenSDand

LDandoverrepresentedinSD(Fig.6;SupportingFigs.S5andS6).

MostofthetranscriptsassignedtothisbinthatareincreasedinSD

encodephotosystemIorIIproteins(SupportingTableS4).Someof

theirgenesseemtobelinkedtoreducedgrowth,nevertheless,the

SDcomparedtotheLDphotoperiodapparentlyincreases

photo-systemabundance.Thislikelyincreasestherateofphotosynthesis

tousethelightoftheshorterilluminationperiodmostefficiently.

3.10. ProteinsthatdifferbetweenSDandLDcanmainlybe

attributedtodifferencesingrowth

Wenextexaminedtheproteinsthataredifferentiallyexpressed

intheLDandSOWplants(p-value<0.05inapairedt-test,average

fold-change>1.5).Atotalof24proteinsfulfilledthestrictcut-off

criteriathatwerealsoappliedtothetranscriptdata.Ofthe13

pro-teinsthatwerehigherinLD,5werealsoincreasedinLDcompared

toSWD,andofthe11thatwerelowerinLD,4werealso

signifi-cantlydecreasedinLDcomparedtoSWD.Theseproteinstherefore

showasignificantdifferencebetweenLDandbothSDconditions

(Table1).

ThelistofproteinsthataremoreabundantinLDthaninSD

includesPATHOGENESIS-RELATEDPROTEIN5(PR5,AT1G75040),

PR2(AT3G57260)andribosomalL28efamilyprotein(AT2G19730).

Thisisconsistentwithourpreviousfindingsthatmostofthe

pro-teinsthataccumulatedtohigherlevelsinthefastergrowingSOW

leavesthanintheSWDleavesmainlycomprisedproteinsinvolved

intranslationandthattranscriptswithhigherlevelsintheSOW

leavesareover-represented forGOcategories ribosome

biogene-sis,translation anddefenceresponsetofungus[18].Furthermore,

MapManbinstress.bioticwasover-representedfortranscriptsthat

havehigherlevelsinLD.Thelistofproteinsthataccumulateto

significantlyhigherlevelsinLDalsoincludes

PHOSPHOMANNO-MUTASE(PMM,AT2G45790),whichisinvolvedinthesynthesisof

GDP-mannoseandisthereforerequiredforascorbicacid

biosyn-thesisandN-glycosylation.Interestingly,thepmmmutanthasa

temperature-sensitivephenotypethat was attributedtoa

defi-ciencyinproteinglycosylation[53].Thedifferentabundancelevels

of PMM of in LD and SD might therefore suggest differential

post-translationalmodificationsinLDandSD.GERANYLGERANYL

PYROPHOSPHATESYNTHASE1(GGPPS11,AT4G36810),whichis

requiredforthebiosynthesisofgeranylgeranyldiphosphate(GGPP)

[54],alsoaccumulatestohigherlevelsinleaf6growninLDas

com-paredtoSOWconditions.InArabidopsis,thechloroplast-localized

GGPPS11istheGGPPSisoformwiththehighesttranscriptlevel

inrosetteleavesandmainlyresponsiblefor thebiosynthesis of

GGPP-derived isoprenoidmetabolitesincluding chlorophylland

carotenoids[54].ThehigherproteinlevelofGGPPS11inLDthanin

SDthereforesuggeststheincreasedproductionofthese

metabo-litesinLD.

TheproteinsthataresignificantlymoreabundantinSDthan

in LD are PLASTOCYANIN 1 (PETE1,AT1G76100)and the three

cold response (COR) proteins COR15A (AT2G42540), COR15B

(AT2G42530)andCOR6.6(AT5G15970)(Table1).Although

plasto-cyaninshavebeenimplicatedinphotosyntheticelectrontransport,

theirconcentration is not limiting for electronflow in optimal

growthconditionswith11hlight[55].TheincreasedPETE1

pro-tein levelin SDmight thereforeindicate aspecificrole for this

proteininshortphotoperiods.TheCORproteinsarealso

signifi-cantlymoreabundantinleaf6growninSWDascomparedtoSOW

conditionsandhavebeenimplicatedintheadaptationresponse

tothecontinuous40%waterdeficitcondition[18].However,the

LDdatasuggestthattheaccumulationofthethreeCORproteins

mayalsoberelatedtogrowth.Wedidnotclassifytranscriptsfor

theseproteinsas photoperiod-specificbecausetheyare

signifi-cantlydifferentbetweenSWDandLDbutnotbetweenSOWandLD.

Acrosstalkbetweencoldresponseandfloweringtimeregulation

hasbeenproposedpreviously,withSOC1functioningasanegative

regulatorofCBFsthatbindtotheCORpromoters[56].Here,the

sit-uationisdifferent,becauseSOC1andCBF1(AT4G25490)transcript

levelsarehigherinLDascomparedtoSDandtheCORtranscripts

showadifferentbehaviour.Therefore,thelevelsoftheCOR

pro-teinsseemtoberegulateddifferentlyandrelatedtothegrowth

rateoftheleaves.

3.11. Floweringgeneshavephotoperiod-specifictranscript

signaturesinleaves

LD photoperiods that are characteristic of spring and early

summerinduceflowering in LD plants. Thecore photoperiodic

floweringpathwaycomprisesGIGANTEA(GI,AT1G22770),

FLOW-ERINGLOCUST(FT,AT1G65480)andCONSTANS(CO,AT5G15840)

[57,58].CircadianclockregulationofCOtranscriptlevelandprotein

stabilityiskeytomonitoringchangesinphotoperiodlength,and

[57].ThemRNAlevelsfortheCOtargetFTwerehigherinLD

com-paredtoSDandincreasedduringdevelopment(SupportingFig.S7).

DownstreamofFT,theMADS-boxtranscriptionfactors

AGAMOUS-LIKE20/SUPPRESSOROFCONSTANS1(SOC1,AT2G45660),AGL24

(AT4G24540),FRUITFULL(FUL,AT5G60910)andSHORT

VEGETA-TIVEPHASE(SVP,AT2G22540)functionasfloralintegratorgenes

duringthetransitionoftheshootapicalmeristem(SAM)tothe

flo-ralmeristem[59].Notably,AGL24andFULtranscriptlevelswere

significantlyhigherinLDalsoinleaf6.SOC1transcriptlevelswere

onlyhigherinLDatearlyleaf6developmentalstages,andSVP

tran-scriptlevelswerenotsignificantlydifferentbetweenLDandSD

(SupportingFig.S7).Incontrast,themRNAlevelsforFLOWERING

LOCUSC(FLC,AT5G10140),whichisakeyrepressorofflowering

[60],weresignificantlylowerinLDascomparedtoSD(Supporting

Fig.S7).FLCandSVPformheterodimersduringvegetativegrowth

torepresstranscriptionofFTinleavesandSOC1intheSAM[61].The

reducedlevelsofFLCtranscriptsinLDtogetherwiththeincreased

levelsofFTtranscriptsarethereforeconsistentwithanearlyrelease

offloweringrepressioninLD.

SOC1belongstothegroupofgenesthathaveadiurnal

expres-sionpeakintheafternoon,withSOC1transcriptlevelsbeinghigher

atEODinSD,buthigheratEONinLD(Fig.5).Interestingly,this

patternwasalsofoundfortranscriptlevelsofthepotentialnatural

antisenseRNAgeneAT1G69572,whosegenomicregionoverlaps

withthat of CDF5.Accordingtodata reportedby Bläsinget al.

[62],SOC1transcriptlevelswerehighestintheafternoon(ZT8)ina

12h/12hphotoperiod.Whencomparedtofree-runningconditions

ofcontinuouswhitelight[63],SOC1transcriptlevelswerehighest

atZT8duringthefirstdaybutnosubsequentcircadianoscillation

wasdetectable.SOC1thereforebelongstothegroupgeneswhose

transcriptlevelsarenotregulatedbythecircadianclockbutdirectly

byphotoperiod.

3.12. AtGRP7protein,butnottranscript,ismorehighlyexpressed

inLD

Theglycine-richRNA-bindingproteinAtGRP7(AT2G21660)has

animportantroleinflowering.ExpressionofAtGRP7isdirectly

con-trolledbyCCA1andLHY,anditstranscriptlevelsoscillatewitha

peakintheevening[64].AtGRP7regulatestheamplitudeofthe

circadianoscillationofitsmRNAthroughalternativesplicing.

Ara-bidopsisplantsthatconstitutivelyover-expressAtGRP7producea

short-livedmRNAspliceform,whichdampensAtGRP7transcript

oscillationsandinfluencestheaccumulationofothertranscripts

includingAtGRP8 (AT4G39260)[65].Astheresult, AtGRP7

pro-motesflowering,withamorepronouncedeffectinSDthaninLD

[66].InLDweindeedobservedadampeningofbothAtGRP7and

AtGRP8diurnaltranscriptlevelchangesatallleaf6development

stages,butthetranscriptlevelsofAtGRP7didnotchange

signifi-cantlyduringdevelopment(SupportingFig.S8).Incontrast,AtGRP7

proteinlevelsweresignificantlyhigherintheLDexperimentas

comparedtoSOW(Table1),didnotdisplaydiurnallevelchanges,

anddecreasedduringdevelopmentbothinSDandLD(Supporting

Fig.S8).ThehigherAtGRP7proteinlevelsinLDascomparedtoSD

provideanexplanationforearlierobservationsthattheeffectof

AtGRP7overexpressionontimetofloweringisstrongerinSDthan

inLD.

4. Conclusions

Inadditiontophotoperiod,whichmayactatmultiplepoints

inthecircadianclock[67–69],therhythmic,diurnalendogenous

sugarsignalscanentraincircadianrhythmsinArabidopsis[70].

Fur-thermore,inan18hphotoperiodconsiderableamountsofstarch

remainatEONwhiletherateofphotosynthesisisdecreased

com-paredtoa4-,6-,8-,and12-hphotoperiod.Consequently,inlong

photoperiodsgrowthis notlongerlimitedbytheavailabilityof

carbonandthecarbonconversionefficiencydecreases[6].By

sys-tematicallyinvestigatingthemolecularchangesinasingleleafthat

areinvolvedintheadaptationtodifferentphotoperiodsinhighly

controlledconditionswedemonstratedthatfewertranscripts

dis-playsignificantchangesbetweenEODandEONinLDthaninSD.We

previouslydiscussedthatdifferentmRNAlevelsatspecifictimes

duringthediurnalcyclemightberequiredforthetime-dependent

regulationofthecellularenergystatusinprevailingenvironmental

conditions[18].Ifdiurnaltranscriptlevelfluctuationsareindeed

requiredforefficientresourceallocation,thismightexplainwhy

plantsgrowninlongdaysdonotdependonastrictdiurnal

regula-tionoftranscriptiontotightlyeconomisetheirenergybudget.We

alsoestablishedthattranscriptsregulatedbyphotoperiodbelong

to specificfunctional categories that areimportant for

adapta-tiontotheprevailingphotoperiodcondition.Incontrast,identified

proteinsthatdiffersignificantlybetweenphotoperiodsaremainly

relatedtothedifferentgrowthratesofleaf6.Together,changesin

thecomplexmolecularpatternunderlyingleafgrowthindifferent

photoperiodsaretightlylinkedtotheavailableenergy.

Conflictsofinterest

none.

Acknowledgements

WethanktheFunctionalGenomicsCenterZurich(FGCZ)for

pro-vidinginfrastructureandtechnicalsupport,PascalSchläpferand

JohannesFütterer(ETHZurich)forhelpfuldiscussionsandcritical

readingofthemanuscript.We thankNicoleKrohnandBeatrice

Encke(MPIMP)formetaboliteanalyses.Thisworkwassupported

bytheAGRON-OMICSintegratedprojectfundedintheEuropean

FrameworkProgramme6(LSHG-CT-2006-037704).TheUMREEF

issupportedbytheFrenchNationalResearchAgencythroughthe

LaboratoryofExcellenceARBRE(ANR-12-LABXARBRE-01).

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in

theonlineversion,athttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpb.2015.07.001

References

[1]A.N.Dodd,N.Salathia,A.Hall,E.Kévei,R.Tóth,F.Nagy,etal.,Plantcircadian clocksincreasephotosynthesis,growth,survival,andcompetitiveadvantage, Science309(2005)630–633,http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1115581

[2]C.Troein,J.C.W.Locke,M.S.Turner,A.J.Millar,Weatherandseasonstogether demandcomplexbiologicalclocks,Curr.Biol.19(2009)1961–1964,http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.024

[3]E.M.Farré,S.E.Weise,Theinteractionsbetweenthecircadianclockand primarymetabolism,Curr.Opin.PlantBiol.15(2012)293–300,http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.pbi.2012.01.013

[4]B.Y.Chow,S.A.Kay,Globalapproachesfortellingtime:Omicsandthe Arabidopsiscircadianclock,Semin.CellDev.Biol.24(2013)383–392,http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.02.005

[5]A.Graf,A.M.Smith,Starchandtheclock:thedarksideofplantproductivity, TrendsPlantSci.16(2011)169–175,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010. 12.003

[6]R.Sulpice,A.Flis,A.aIvakov,F.Apelt,N.Krohn,B.Encke,etal.,Arabidopsis coordinatesthediurnalregulationofcarbonallocationandgrowthacrossa widerangeofphotoperiods,Mol.Plant7(2014)137–155,http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/mp/sst127

[7]R.Hayama,G.Coupland,Sheddinglightonthecircadianclockandthe photoperiodiccontrolofflowering,Curr.Opin.PlantBiol.6(2003)13–19,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1369-5266

[8]F.Andrés,G.Coupland,Thegeneticbasisoffloweringresponsestoseasonal cues,Nat.Rev.Genet.13(2012)627–639,http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrg3291

[9]H.A.Kinmonth-Schultz,G.S.Golembeski,T.Imaizumi,Circadian

CellDev.Biol.24(2013)407–413,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2013. 02.006

[10]A.Srikanth,M.Schmid,Regulationoffloweringtime:allroadsleadtoRome, Cell.Mol.LifeSci.68(2011)2013–2037, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00018-011-0673-y

[11]K.S.Sandhu,K.Hagely,M.M.Neff,Geneticinteractionsbetween

brassinosteroid-inactivatingP450sandphotomorphogenicphotoreceptorsin Arabidopsisthaliana,G32(2012)1585–1593,http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/g3. 112.004580

[12]S.J.Cookson,K.Chenu,C.Granier,Daylengthaffectsthedynamicsofleaf expansionandcellulardevelopmentinArabidopsisthalianapartiallythrough floraltransitiontiming,Ann.Bot.99(2007)703–711,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1093/aob/mcm005

[13]T.Usami,G.Horiguchi,S.Yano,H.Tsukaya,Themoreandsmallercells mutantsofArabidopsisthalianaidentifynovelrolesforSQUAMOSA PROMOTERBINDINGPROTEIN-LIKEgenesinthecontrolofheteroblasty, Development136(2009)955–964,http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.028613

[14]R.S.Poethig,Thepast,present,andfutureofvegetativephasechange,Plant Physiol.154(2010)541–544,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.161620

[15]M.R.Willmann,R.S.Poethig,TheeffectofthefloralrepressorFLConthe timingandprogressionofvegetativephasechangeinArabidopsis, Development138(2011)677–685,http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.057448

[16]N.Wuyts,C.Massonnet,M.Dauzat,C.Granier,Structuralassessmentofthe impactofenvironmentalconstraintsonArabidopsisleafgrowth:a3D approach,PlantCellEnv.35(2012)1631–1646,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.

1365-3040.2012.02514.x

[17]A.Telfer,K.M.Bollman,R.S.Poethig,Phasechangeandtheregulationof trichomedistributioninArabidopsisthaliana,Development124(1997) 645–654.

[18]K.Baerenfaller,C.Massonnet,S.Walsh,S.Baginsky,P.Bühlmann,L.Hennig, etal.,Systems-basedanalysisofArabidopsisleafgrowthrevealsadaptationto waterdeficit,Mol.Syst.Biol.8(2012),http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/msb.2012.39

[19]C.Granier,L.Aguirrezabal,K.Chenu,S.J.Cookson,M.Dauzat,P.Hamard,etal., PHENOPSIS,anautomatedplatformforreproduciblephenotypingofplant responsestosoilwaterdeficitinArabidopsisthalianapermittedthe identificationofanaccessionwithlowsensitivitytosoilwaterdeficit,New Phytol.169(2006)623–635,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005. 01609.x

[20]C.Massonnet,D.Vile,J.Fabre,M.A.Hannah,C.Caldana,J.Lisec,etal.,Probing thereproducibilityofleafgrowthandmolecularphenotypes:acomparisonof threeArabidopsisaccessionscultivatedintenlaboratories,PlantPhysiol.152 (2010)2142–2157,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.148338

[21]J.M.Cross,M.vonKorff,T.Altmann,L.Bartzetko,R.Sulpice,Y.Gibon,etal., Variationofenzymeactivitiesandmetabolitelevelsin24Arabidopsis accessionsgrowingincarbon-limitedconditions,PlantPhysiol.142(2006) 1574–1588,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.086629

[22]Y.Gibon,O.E.Blaesing,J.Hannemann,P.Carillo,M.Höhne,J.H.M.Hendriks, etal.,ARobot-basedplatformtomeasuremultipleenzymeactivitiesin Arabidopsisusingasetofcyclingassays:comparisonofchangesofenzyme activitiesandtranscriptlevelsduringdiurnalcyclesandinprolonged darkness,PlantCell16(2004)3304–3325,http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.104. 025973

[23]H.Rehrauer,C.Aquino,W.Gruissem,S.R.Henz,P.Hilson,S.Laubinger,etal., AGRONOMICS1:anewresourceforArabidopsistranscriptomeprofiling,Plant Physiol.152(2010)487–499,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.150185

[24]M.Müller,A.Patrignani,H.Rehrauer,W.Gruissem,L.Hennig,Evaluationof alternativeRNAlabelingprotocolsfortranscriptprofilingwithArabidopsis AGRONOMICS1tilingarrays,PlantMet.8(2012)18,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1186/1746-4811-8-18

[25]P.L.Ross,Y.N.Huang,J.N.Marchese,B.Williamson,K.Parker,S.Hattan,etal., MultiplexedproteinquantitationinSaccharomycescerevisiaeusing amine-reactiveisobarictaggingreagents,Mol.CellProteomics3(2004) 1154–1169.

[26]A.Pierce,R.D.Unwin,C.A.Evans,S.Griffiths,L.Carney,L.Zhang,etal., Eight-channeliTRAQenablescomparisonoftheactivityofsixleukemogenic tyrosinekinases,Mol.CellProteomics7(2008)853–863.

[27]P.Lamesch,T.Z.Berardini,D.Li,D.Swarbreck,C.Wilks,R.Sasidharan,etal., TheArabidopsisInformationResource(TAIR):improvedgeneannotationand newtools,NucleicAcidsRes.40(2012)D1202–D1210,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1093/nar/gkr1090

[28]K.Baerenfaller,M.Hirsch-Hoffmann,J.Svozil,R.Hull,D.Russenberger,S. Bischof,etal.,pep2pro:anewtoolforcomprehensiveproteomedataanalysis torevealinformationaboutorgan-specificproteomesinArabidopsisthaliana, Integr.Biol.(Camb)3(2011)225–237,http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0ib00078g

[29]M.Hirsch-Hoffmann,W.Gruissem,K.Baerenfaller,pep2pro:the

high-throughputproteomicsdataprocessing,analysis,andvisualizationtool, Front.PlantSci.3(2012),http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2012.00123

[30]J.A.Vizcaíno,R.G.Côté,A.Csordas,J.A.Dianes,A.Fabregat,J.M.Foster,etal., ThePRoteomicsIDEntifications(PRIDE)databaseandassociatedtools:status in2013,NucleicAcidsRes.41(2013)D1063–D1069,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1093/nar/gks1262

[31]Y.Benjamini,Y.Hochberg,Controllingthefalsediscoveryrate:apracticaland powerfulapproachtomultipletesting,J.R.Stat.Soc.Ser.B57(1995)289–300.

[32]RCoreTeam,R.A.languageandenvironmentforstatisticalcomputing,2012.

http://www.r-project.org

[33]V.Wahl,J.Ponnu,A.Schlereth,S.Arrivault,T.Langenecker,A.Franke,etal., Regulationoffloweringbytrehalose-6-phosphatesignalinginArabidopsis thaliana,Science339(2013)704–707,http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science. 1230406

[34]K.D.Edwards,P.E.Anderson,A.Hall,N.S.Salathia,J.C.W.Locke,J.R.Lynn,etal., FLOWERINGLOCUSCmediatesnaturalvariationinthehigh-temperature responseoftheArabidopsiscircadianclock,PlantCell18(2006)639–650,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.038315

[35]A.Yilmaz,M.K.Mejia-Guerra,K.Kurz,X.Liang,L.Welch,E.Grotewold,AGRIS: theArabidopsisGeneregulatoryinformationserver,anupdate,NucleicAcids Res.39(2010)D1118–D1122,http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq1120

[36]O.Thimm,O.Bläsing,Y.Gibon,A.Nagel,S.Meyer,P.Krüger,etal.,MAPMAN: auser-driventooltodisplaygenomicsdatasetsontodiagramsofmetabolic pathwaysandotherbiologicalprocesses,PlantJ.37(2004)914–939.

[37]W.A.Decatur,M.J.Fournier,rRNAmodificationsandribosomefunction, TrendsBiochem.Sci.27(2002)344–351.

[38]J.B.Harborne,C.A.Williams,Advancesinflavonoidresearchsince1992, Phytochemistry55(2000)481–504.

[39]M.Kanehisa,S.Goto,Y.Sato,M.Furumichi,M.Tanabe,KEGGforintegration andinterpretationoflarge-scalemoleculardatasets,NucleicAcidsRes.40 (2012)D109–D114,http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr988

[40]I.S.Carvalho,T.Cavaco,L.M.Carvalho,P.Duque,Effectofphotoperiodon flavonoidpathwayactivityinsweetpotato(Iopmeabatatas(L.)Lam.)leaves, FoodChem.118(2010)384–390.

[41]U.Takahama,RedoxReactionsbetweenkaempferolandilluminated chloroplasts,PlantPhysiol.71(1983)598–601.

[42]G.Krouk,S.Ruffel,R.A.Gutiérrez,A.Gojon,N.M.Crawford,G.M.Coruzzi,etal., Aframeworkintegratingplantgrowthwithhormonesandnutrients,Trends PlantSci.16(2011)178–182,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2011.02.004

[43]M.Vanstraelen,E.Benková,Hormonalinteractionsintheregulationofplant development,AnnuRevCellDevBiol.28(2012)463–487,http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155741

[44]K.C.McGrath,B.Dombrecht,J.M.Manners,P.M.Schenk,C.I.Edgar,D.J. Maclean,etal.,Repressor-andactivator-typeethyleneresponsefactors functioninginjasmonatesignalinganddiseaseresistanceidentifiedviaa genome-widescreenofArabidopsistranscriptionfactorgeneexpression, PlantPhysiol.139(2005)949–959,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.068544

[45]G.H.Son,J.Wan,H.J.Kim,X.C.Nguyen,W.S.Chung,J.C.Hong,etal., Ethylene-responsiveelement-bindingfactor5,ERF5,isinvolvedin chitin-inducedinnateimmunityresponse,Mol.PlantMicrobe.Interact25 (2012)48–60,http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/-06-11-0165

[46]R.Bours,M.vanZanten,R.Pierik,H.Bouwmeester,A.vanderKrol,Antiphase lightandtemperaturecyclesaffectPHYTOCHROMEB-controlledethylene sensitivityandbiosynthesis,limitingleafmovementandgrowthof Arabidopsis,PlantPhysiol.163(2013)882–895,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp. 113.221648

[47]E.M.Turk,S.Fujioka,H.Seto,Y.Shimada,S.Takatsuto,S.Yoshida,etal.,BAS1 andSOB7actredundantlytomodulateArabidopsisphotomorphogenesisvia uniquebrassinosteroidinactivationmechanisms,PlantJ.42(2005)23–34, 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05093.x.

[48]E.M.Turk,S.Fujioka,H.Seto,Y.Shimada,S.Takatsuto,S.Yoshida,etal., CYP72B1inactivatesbrassinosteroidhormones:anintersectionbetween photomorphogenesisandplantsteroidsignaltransduction,PlantPhysiol.133 (2003)1643–1653,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.103.030882

[49]Y.Yin,D.Vafeados,Y.Tao,S.Yoshida,T.Asami,J.Chory,Anewclassof transcriptionfactorsmediatesbrassinosteroid-regulatedgeneexpressionin Arabidopsis,Cell120(2005)249–259,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004. 11.044

[50]M.Büttner,Themonosaccharidetransporter(-like)genefamilyin Arabidopsis,FEBSLett.581(2007)2318–2324,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. febslet.2007.03.016

[51]R.Stadler,M.Büttner,P.Ache,R.Hedrich,N.Ivashikina,M.Melzer,etal., Diurnalandlight-regulatedexpressionofAtSTP1inguardcellsofArabidopsis, PlantPhysiol.133(2003)528–537,http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.103.024240

[52]M.H.Cho,H.Lim,D.H.Shin,J.S.Jeon,S.H.Bhoo,Y.IlPark,etal.,Roleofthe plastidicglucosetranslocatorintheexportofstarchdegradationproducts fromthechloroplastsinArabidopsisthaliana,NewPhytol.190(2011) 101–112,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03580.x

[53]F.A.Hoeberichts,E.Vaeck,G.Kiddle,E.Coppens,B.vandeCotte,A. Adamantidis,etal.,ATemperature-sensitivemutationintheArabidopsis thalianaphosphomannomutasegenedisruptsproteinglycosylationand triggerscelldeath,J.Biol.Chem.283(2008)5708–5718,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1074/jbc.M704991200

[54]G.Beck,D.Coman,E.Herren,M.A.Ruiz-Sola,M.Rodríguez-Concepción,W. Gruissem,etal.,CharacterizationoftheGGPPsynthasegenefamilyin Arabidopsisthaliana,PlantMol.Biol.82(2013)393–416,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1007/s11103-013-0070-z

[55]P.Pesaresi,M.Scharfenberg,M.Weigel,I.Granlund,W.P.Schröder,G.Finazzi, etal.,Mutants,overexpressors,andinteractorsofArabidopsisplastocyanin isoforms:revisedrolesofplastocyanininphotosyntheticelectronflowand thylakoidredoxstate,Mol.Plant2(2009)236–248,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1093/mp/ssn041

[56]E.Seo,H.Lee,J.Jeon,H.Park,J.Kim,Y.-S.Noh,etal.,Crosstalkbetweencold responseandfloweringinArabidopsisismediatedthroughthe

flowering-timegeneSOC1anditsupstreamnegativeregulatorFLC,PlantCell 21(2009)3185–3197,http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.063883

[57]Y.Kobayashi,D.Weigel,Moveonup,it’stimeforchange-mobilesignals controllingphotoperiod-dependentflowering,GenesDev.21(2007) 2371–2384,http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1589007

[58]F.Turck,F.Fornara,G.Coupland,Regulationandidentityofflorigen: FLOWERINGLOCUSTmovescenterstage,Annu.Rev.PlantBiol.59(2008) 573–594,http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092755

[59]S.Torti,F.Fornara,AGL24actsinconcertwithSOC1andFULduring Arabidopsisfloraltransition,PlantSignalBehav.7(2012)1251–1254,http:// dx.doi.org/10.4161/psb.21552

[60]S.D.Michaels,R.M.Amasino,FLOWERINGLOCUSCencodesanovelMADS domainproteinthatactsasarepressorofflowering,PlantCell11(1999) 949–956.

[61]D.Li,C.Liu,L.Shen,Y.Wu,H.Chen,M.Robertson,etal.,ARepressorComplex GovernstheIntegrationofFloweringSignalsinArabidopsis,Dev.Cell15 (2008)110–120,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.002

[62]O.E.Bläsing,Y.Gibon,M.Günther,M.Höhne,R.Morcuende,D.Osuna,etal., Sugarsandcircadianregulationmakemajorcontributionstotheglobal regulationofdiurnalgeneexpressioninArabidopsis,PlantCell17(2005) 3257–3281,http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.035261

[63]M.F.Covington,J.N.Maloof,M.Straume,S.A.Kay,S.L.Harmer,Global transcriptomeanalysisrevealscircadianregulationofkeypathwaysinplant growthanddevelopment,GenomeBiol.9(2008)R130,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1186/gb-2008-9-8-r130

[64]C.Heintzen,M.Nater,K.Apel,D.Staiger,AtGRP7,anuclearRNA-binding proteinasacomponentofacircadian-regulatednegativefeedbackloopin Arabidopsisthaliana,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.94(1997)8515–8520,USA.

[65]D.Staiger,L.Zecca,D.A.WieczorekKirk,K.Apel,L.Eckstein,Thecircadian clockregulatedRNA-bindingproteinAtGRP7autoregulatesitsexpressionby influencingalternativesplicingofitsownpre-mRNA,PlantJ.33(2003) 361–371.

[66]C.Streitner,S.Danisman,F.Wehrle,J.C.Schöning,J.R.Alfano,D.Staiger,The smallglycine-richRNAbindingproteinAtGRP7promotesfloraltransitionin Arabidopsisthaliana,PlantJ.56(2008)239–250,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j. 1365-313X,2008.03591.x.

[67]A.J.Millar,Inputsignalstotheplantcircadianclock,J.Exp.Bot.55(2004) 277–283,http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh034

[68]A.Pokhilko,A.P.Fernández,K.D.Edwards,M.M.Southern,K.J.Halliday,A.J. Millar,TheclockgenecircuitinArabidopsisincludesarepressilatorwith additionalfeedbackloops,Mol.Syst.Biol.8(2012)574,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1038/msb.2012.6

[69]M.L.Rugnone,A.Faig,S.E.Sanchez,R.G.Schlaen,C.E.Hernando,K.Danelle, etal.,LNKgenesintegratelightandclocksignalingnetworksatthecoreofthe Arabidopsisoscillator,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A110(2013)12120–12125,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1302170110

[70]M.J.Haydon,O.Mielczarek,F.C.Robertson,K.E.Hubbard,A.A.R.Webb, PhotosyntheticentrainmentoftheArabidopsisthalianacircadianclock, Nature502(2013)689–692,http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12603.