ETUDE PHYSIOLOGIQUE ET METABOLIQUE DE

LA PRODUCTION DE LA FLOCCULOSINE CHEZ

PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA

Thèse présentée

à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Laval dans le cadre du programme de doctorat en biologie végétale

pour l'obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph. D.)

DEPARTEMENT DE PHYTOLOGIE

FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES DE L'AGRICULTURE ET DE L'ALIMENTATION UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL

QUÉBEC

2010

En quij 'ai toujours cru En qui je croirai toujours

A ma famille, Symbole de tous les sacrifices

A ma femme, Symbole d'amour et de sacrifice inconditionnels

A ma fille Nour

A mes professeurs, Pour le savoir qu 'ils m'ont transmis Pour leur générosité et leur confiance

Vous avez fait de moi un être fort et heureux

« Il y a dans la création des cieux et de la terre et dans la succession de la nuit et du jour, des signes pour ceux qui sont doués d'intelligence ».

Le champignon Pseudozyma flocculosa a été particulièrement étudié pour son activité biologique contre le blanc (Érysiphales). Par génie génétique, un glycolipide à activité antifongique, la flocculosine, a été isolé et caractérisé. Bien que le spectre d'activité de cette molécule ait été identifié, les conditions in vitro et in vivo dans lesquelles ce composé est synthétisé ne sont pas encore élucidées.

La première partie de ce travail consistait à déterminer les besoins nutritionnels de P. flocculosa ainsi que les paramètres jouant un rôle primordial dans la synthèse de la flocculosine. Suite à cette étude, nous avons pu atteindre une productivité de 15 g/1 de flocculosine et définir certains éléments influençant la synthèse de la molécule. En bref, la disponibilité d'une source de carbone et l'ajout de l'extrait de levure sont apparus comme les deux principaux facteurs ayant un impact majeur sur la synthèse du glycolipide.

Dans la deuxième partie de ce projet, nous nous sommes intéressés à l'investigation des changements métaboliques corrélés à la synthèse de la flocculosine. Pour ce faire, nous avons effectué une étude protéomique dans deux conditions de production différentes (inductrice et répressive). La comparaison des deux profils protéomiques a montré une diminution drastique du nombre total des protéines suggérant que le champignon produit cette molécule pour contourner le déséquilibre métabolique provoqué par la condition de stress.

Enfin, nous avons tenté de déterminer le rôle exact de la flocculosine dans le cadre de la relation tritrophique plante-agent pathogène-P. flocculosa. Nous avons suivi en particulier l'expression du gène cypl, impliqué dans la synthèse de cette molécule, lorsque P. flocculosa était soumis à différentes conditions environnementales. Cette étude nous a permis de conclure que P. flocculosa synthétisait la flocculosine in vivo en réponse aux disponibilités variables des substrats à la surface de la feuille.

AVANT-PROPOS

La réalisation de ce projet de doctorat a été parsemée de défis personnels et professionnels. La rédaction de cette thèse marque la fin d'une bien belle époque et le début d'une autre. Bien que le « bonheur soit en nous », plusieurs personnes ont marqué de façon positive cette période de ma vie.

Les travaux de cette thèse ont été réalisés dans le cadre d'un projet de recherche financé par le Conseil de la recherche en sciences naturelles et génie du Canada (CRSNG). Cette thèse a été réalisée à l'Université Laval, au sein du Centre de recherche en horticulture à Québec sous la direction de M. Richard Bélanger, professeur à la Faculté des sciences de l'agriculture et de l'alimentation et titulaire de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en phytoprotection.

Ces travaux portaient sur l'étude physiologique et métabolique de la synthèse de la flocculosine par l'agent de lutte biologique Pseudozyma flocculosa. Les résultats sont présentés sous la forme de trois articles scientifiques qui font l'objet des chapitres 2, 3, et 4 de la thèse. Le premier chapitre est une courte revue de littérature afin de fournir une idée sur les données bibliographiques sous-jacentes aux objectifs de ce travail.

Les trois chapitres suivants ont été rédigés en anglais sous forme d'articles qui ont été publiés ou soumis dans des revues scientifiques. Le premier chapitre porte sur l'étude de la production de la flocculosine par P. flocculosa. Le deuxième correspond à la première étude protéomique de P. flocculosa afin de déterminer son comportement métabolique lors de la synthèse de la flocculosine. Le troisième chapitre concerne les travaux de PCR quantitative pour étudier le comportement différentiel entre P. flocculosa et Ustilago maydis permettant de déterminer le rôle écologique potentiel de la flocculosine.

Enfin, une discussion générale et les conclusions de ce travail sont présentées dans le cadre du cinquième chapitre.

Les références citées dans l'introduction et les conclusions générales se retrouvent à la fin de chaque partie, tandis que celles citées dans les manuscrits se trouvent à la fin de ces derniers.

En dernier lieu, une annexe présente un article scientifique auquel le rédacteur de cette thèse a participé.

REMERCIEMENTS

Tout d'abord, je tiens à exprimer toute ma gratitude et mes sincères remerciements à mon directeur, Dr Richard Bélanger. Depuis le début, il m'a accordé sa confiance, me permettant ainsi de mener à bien ce projet. Les nombreuses discussions que nous avons eues m'ont beaucoup aidé à comprendre les résultats obtenus. Dr Bélanger, par sa grande rigueur scientifique et ses grandes qualités humaines, m'a offert un excellent environnement de travail et un encadrement de très grande qualité. Je tiens à le remercier de m'avoir inculqué les principes qui sont à la base de toute démarche scientifique: la curiosité, la rigueur, la ténacité et l'humilité. Qu'il soit assuré ici de ma plus sincère reconnaissance.

Nul remerciement ne pourrait exprimer ma profonde reconnaissance et gratitude particulière à Mme Caroline Labbé, pour ses conseils scientifiques judicieux, sa disponibilité exceptionnelle, son support technique incomparable et ses nombreuses qualités personnelles.

Je remercie Dr Dominique Michaud pour m'avoir aidé à réaliser la deuxième partie de ce travail et d'avoir accepté de faire partie de mon jury. Je remercie également Dr Marc Ongena d'avoir accepté d'agir à titre d'évaluateur externe de ma thèse et Dr Russell Tweddell d'avoir accepté de faire partie de mon jury.

Ma reconnaissance à tous mes collègues qui m'ont permis de réaliser mes travaux de recherche dans une ambiance amicale très agréable. Je resterai toujours marqué par le milieu de vie extraordinaire et la belle ambiance du laboratoire de biocontrôle du Centre de recherche en horticulture. La qualité exceptionnelle des rapports entre les professeurs, le personnel administratif, les professionnels et les étudiants est un exemple à saluer. Dans le domaine du savoir et de la recherche, ce climat est très favorable à l'épanouissement de tous.

(CRSNG) pour la bourse doctorale qu'il m'a octroyée.

Merci à toi, Dieu, autant de fois qu'il y a de particules dans l'univers, d'eau dans la mer et de vies sur terre de m'avoir octroyé la chance de réaliser cette thèse au sein d'une ambiance familiale et conviviale. Je n'aurais jamais pu surmonter les épreuves de ma nouvelle aventure à Québec et être celui que je suis aujourd'hui sans ta bienveillance. Dieu, Fais-moi profiter de ce que tu m'as fait connaître et Fais-moi connaître ce qui m'est utile.

TABLE DES MATIERES

RESUME I AVANT-PROPOS II

REMERCIEMENTS IV TABLE DES MATIÈRES VI LISTE DES TABLEAUX X LISTE DES FIGURES XI

CHAPITRE 1 1 REVUE DE LITTÉRATURE 1

1. PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA COMME AGENT DE LUTTE BIOLOGIQUE 2

2. LES GLYCOLIPIDES 3 2.1. Généralités 3 2.2. La flocculosine 4

2.3. Production des glycolipides par fermentation 4 2.3.1. Rôle de la source de carbone sur la synthèse des glycolipides 5

2.3.2. L'importance du stress sur l'induction de la synthèse des glycolipides 5

3. BIOSYNTHÈSE ET IDENTIFICATION DE LA FLOCCULOSINE 6 3.1. Identification des gènes impliqués dans la synthèse de la flocculosine 6

3.2. Identification des voies métaboliques via la technique des gels 2-D 7

4. SYSTÈME ÉCOLOGIQUE 8

4.1. Généralités 8 4.2. Système écologique de Pseudozyma flocculosa 8

5. HYPOTHÈSE ET OBJECTIFS DE RECHERCHE 9

CHAPITRE 2 14 NUTRITIONAL REGULATION AND KINETICS OF FLOCCULOSIN SYNTHESIS BY

PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA 14

RÉSUMÉ 16 ABSTRACT 17

1. INTRODUCTION 18 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 19

2.1. Fungal material 19 2.2. Preparation of fungal cells for flocculosin production 20

2.3. Density of start-up inoculum 20 2.4. Effect of carbon (C) content 20 2.5. Nitrogen source and concentration effect 21

2.6. Dosage of flocculosin 21

2.6.1. Sample preparation 21 2.6.2. Preparation of flocculosin standard 21

2.6.3. HPLC analyses 22 2.7. Determination of cell dry weight 22

3. RESULTS 22 3.1. Density of start-up inoculum and effect of carbon content 22

3.2. Effect of nitrogen concentration 23

3.3. Effect of yeast extract 23

4. DISCUSSION 24 5. REFERENCES 28

CHAPITRE 3 36 PROTEOMIC ANALYSIS OF METABOLIC ADAPTATION OF THE BIOCONTROL

AGENT PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA LEADING TO GLYCOLIPID PRODUCTION .36

RÉSUMÉ 38 ABSTRACT 39

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 41

2.1 Fungal material 41 2.2 Culture conditions 42 2.3 Protein extraction 42

2.4 2-DE 43 2.5 Image analysis and protein identification 43

2.5.1 P. flocculosa genome sequencing 43

2.5.2 Protein identification 44

3. RESULTS 45 3.1 Culture conditions 45

3.2 Protein extraction and 2-DE 45 3.3 Protein identification 45

4. DISCUSSION 46 5. CONCLUSION 50 6. REFERENCES 51

CHAPITRE 4 59 THE ECOLOGICAL BASIS OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN PSEUDOZYMA

FLOCCULOSA AND POWDERY MILDEW FUNGI 59

RÉSUMÉ 61 ABSTRACT 62 1. INTRODUCTION 63

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 64

2.1 Fungal material 64 2.2 Infection 65 2.3 In situ bioassays with Pseudozyma flocculosa and Ustilago maydis 65

2.4 Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of

cypl expression 66 2.5 Fluorescence microscopy observations 66

2.6 Analysis of yeast extract fractions on P. flocculosa growth 67 2.7 Development of P. flocculosa on cucumber leaves treated with zinc and

manganese solution 69

3. RESULTS 69 3.1 Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qPCR) analysis of cypl expression 69

3.2 Fluorescence microscopy observations 69 3.3 Analysis of yeast extract fractions on Pseudozyma flocculosa growth 70

3.4 Development of Pseudozyma flocculosa on cucumber leaves treated with zinc

and manganese solution 70

4. DISCUSSION 71 5. REFERENCES 75 CHAPITRE 5 82 CONCLUSION GÉNÉRALE 82 RÉFÉRENCES 88 ANNEXE 90 IDENTIFICATION OF GENES POTENTIALLY INVOLVED IN THE BIOCONTROL

Chapitre 3

Table 1. Comparative analysis of proteins regulated in a control culture medium or in a stress medium

inducing flocculosin synthesis in Pseudozyma flocculosa cells 56

Chapitre 4

Table. 1. Effect of yeast nitrogen base, its different fractions, and micro-elements solutions on Pseudozyma

LISTE DES FIGURES

Chapitre 1

Figure 1. Plasmolyse du mycélium de Podosphaera xanthii suite à son contact avec P. flocculosa 3

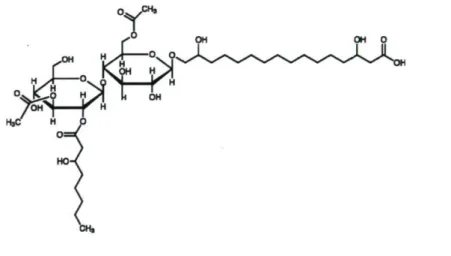

Figure 2. Structure chimique de la flocculosine 4

Chapitre 2

Figure 1. Effect of inoculum size on flocculosin production and on sugar consumption by Pseudozyma

flocculosa cultured on citrate-buffered MOD medium 31 Figure 2. Sucrose (glucose and fructose) consumption and biomass production during flocculosin synthesis

by Pseudozyma flocculosa with 0.4 g dry cell/1 inoculum in buffered MOD medium 32 Figure 3. Effect of a sucrose fedbatch after its depletion on flocculosin synthesis by

Pseudozyma flocculosa 32 Figure 4. Influence of nitrogen concentration on flocculosin synthesis by Pseudozyma flocculosa over time 33

Figure 5. Effect of yeast extract when added at tO to the buffered MOD medium on biomass production, sucrose (glucose and fructose) consumption and flocculosin synthesis by Pseudozyma

flocculosa culture 33 Figure 6. Morphological changes of Pseudozyma flocculosa cells and flocculosin production into the buffered

MOD medium amended or not with YE at time 24 h during 96 h culture 34 Figure 7. Influence of yeast extract amendment and nitrogen source availability on physiological changes of

Pseudozyma flocculosa when grown in presence of a non-limiting carbon source 35

Chapitre 3

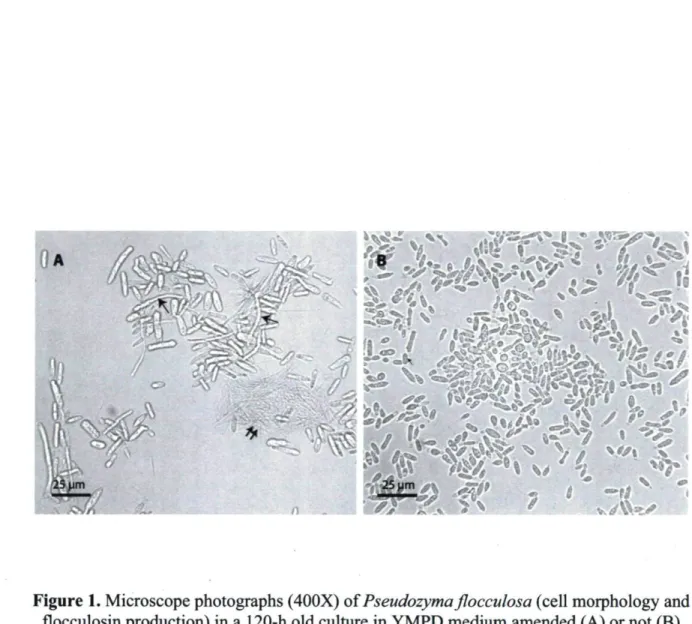

Figure 1. Microscope photographs of Pseudozyma flocculosa in a 120-h old culture in YMPD medium

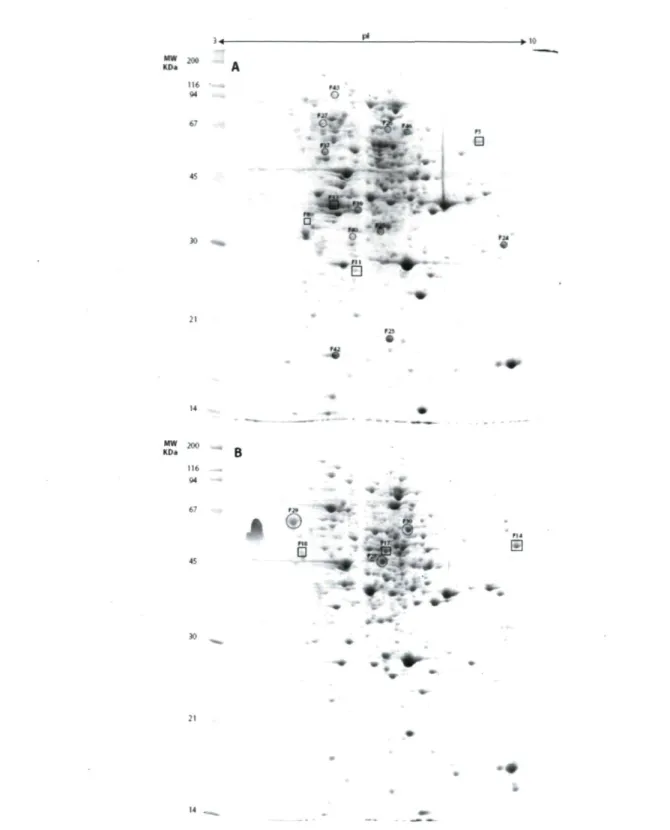

amended or not with sucrose after 72 h , 53 Figure 2. 2-D gels for (A) the proteome of Pseudozyma flocculosa under stress conditions leading to

Figure 3. Volume of selected proteins in protein extracts from Pseudozyma flocculosa cells grown under stress and control conditions. Each of the 21 spots was analyzed in three 2-DE replicate gels 55

Chapitre 4

Figure 1. Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis of Pseudozyma flocculosa actin-normalized cypl expression after inundative applications of conidia on healthy cucumber plant; powdery

mildew-infected cucumber plant; healthy tomato plant and Botrytis cinerea mildew-infected tomato plant 77 Figure 2. Fluorescence microscopy observations of cucumber and tomato leaves 24 h after being sprayed

with a spore suspension of GFP-transformed Pseudozyma flocculosa or Ustilago maydis strains 78 Figure 3. Light microscopy observations of 48 h-old Pseudozyma flocculosa cultures grown in control

medium; CM amended with yeast nitrogen base ; CM amended with micro-elements and CM amended

with ZnS04 and MnS04 79

Figure 4. SEM observations of Pseudozyma flocculosa development on cucumber leaves sprayed with water

1. PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA COMME AGENT DE LUTTE

BIOLOGIQUE

L'utilisation massive de pesticides chimiques a attiré l'attention de l'opinion publique en termes de pollution de l'environnement et de toxicité vis-à-vis de l'homme et des animaux. C'est pourquoi des alternatives plus écologiques sont recherchées depuis plusieurs années et la lutte biologique fait partie de tout programme de réduction de pesticides chimiques. Elle emploie notamment des produits facilement biodégradables et spécifiques aux agents pathogènes ciblés. Ces produits, les biopesticides, peuvent être d'origine virale, bactérienne ou fongique.

Pseudozyma flocculosa est un champignon levuroïde appartenant à la classe des basidiomycètes dont le potentiel en lutte biologique est reconnu depuis longtemps. Il fut d'abord identifié comme un ascomycète et nommé Sporothrix flocculosa (Traquair et al., 1988). Ce n'est que suite à des analyses d'ADN ribosomique qu'il fut décrit comme un basidiomycète de l'ordre des Ustilaginales (Begerow et ai, 2000). Son activité antagoniste a été particulièrement associée au blanc des cultures (Hajlaoui et Bélanger 1991, 1993). Son mode d'action a été proposé comme étant l'antibiose, puisque P. flocculosa ne semble pas nécessiter un contact direct avec le blanc pour causer la plasmolyse des chaînes de conidies produites par les Erysiphales (Fig. 1; Hajlaoui et Bélanger 1993). Quelques années plus tard, suite à des analyses de mutagénèse insertionnelle chez P. flocculosa, Cheng et collaborateurs (2003) ont montré que la molécule responsable de l'activité antifongique du champignon était un glycolipide (cellobiose lipide) de 854 Da nommé flocculosine. Ce composé s'insère dans la vaste classe chimique des biosurfactants. L'activité antagoniste de P. flocculosa a été mise à profit en formulant le biofongicide Sporodex™ à partir de spores du champignon. Ce biofongicide a reçu une homologation temporaire au Canada et aux États-Unis en 2002 pour son utilisation contre le blanc des cultures en serres (Bélanger, 2006).

2. LES GLYCOLIPIDES

2.1. Généralités

Les glycolipides, dont la flocculosine fait partie, constituent la classe de surfactants microbiens les plus répandus et les plus étudiés. Ils attirent l'attention surtout par leur utilisation dans des applications pharmaceutiques, cosmétiques et agroalimentaires (Brown, 1991; Shigeta et Yamashita., 1997). Les glycolipides se composent de glucides (monosaccharides, disaccharides et oligosaccharides) combinés avec des acides aliphatiques à longue chaîne. Ils sont des composés de faible poids moléculaire (<1500 g mol-1) dont on peut distinguer sept sous-groupes : les mannosylérythritol lipides, les sophorolipides, les trehaloses lipides, les rhamnolipides, les succinoyl trehalose lipides, les oligosaccharide lipides et les cellobiose lipides (Lang, 2002).

La flocculosine a été découverte à partir de filtrats de culture du champignon (Cheng et al., 2003). Il s'agit d'une molécule de 854 Da constituée d'un disaccharide (cellobiose) et de deux chaînes d'acides gras (Fig. 1.2). Dérivée d'un agent de lutte biologique, la flocculosine a montré une activité antimicrobienne non seulement contre des agents pathogènes de plantes, mais aussi contre des microorganismes d'importance médicale (Mimée et al, 2005). En effet, la flocculosine a montré des effets délétères très rapides contre une vaste gamme de levures et de champignons filamenteux pathogènes. Elle permet d'inhiber également la croissance de certaines bactéries Gram-i- (Mimée et al, 2005). En plus, elle réduit le risque de toxicité et améliore l'efficacité de l'amphotéricine B (Mimée et al., 2005), la molécule antifongique la plus utilisée dans le traitement des mycoses humaines (et parfois la seule efficace) (Deray, 2002).

Figure 2. Structure chimique de la flocculosine 2.3. Production des glycolipides par fermentation

La plupart des microorganismes exigent pour leur croissance une source de carbone, d'azote, d'oxygène et, à un moindre niveau, de soufre et de phosphore (Reisman,

1988). Toutes ces composantes sont disponibles sous plusieurs formes mais le choix à faire est très important pour aboutir à une procédure de production économique de la molécule d'intérêt, un facteur qui s'avère être limitant pour la commercialisation des biosurfactants malgré leurs nombreux avantages par rapport à leurs analogues chimiques. Les études

limitant cette production (paramètres physiques, formulation du milieu) dans le but de l'optimiser mais sans avoir recours à un produit bon marché. Un des substrats majeurs qui conditionnent la production de flocculosine est la qualité et la quantité du carbone.

2.3.1. Rôle de la source de carbone sur la synthèse des glycolipides

Toutes les études portant sur la production des molécules tensio-actives montrent l'importance du choix de la source de carbone, que ce soit un hydrocarbure, un glucide ou une huile végétale. La source de carbone joue un rôle déterminant dans le taux de production ainsi que sur le choix de la molécule synthétisée. Par exemple, Ustilago maydis est un champignon producteur de deux types de molécules tensio-actives : l'acide ustilagique et le mannosylérythritol lipide (MEL) (Haskins et al., 1955). Il synthétise préférentiellement la molécule cellobiosique en présence de glucose.

De plus, un phénomène de répression catabolique a été détecté chez plusieurs micro-organismes produisant des biosurfactants. Par exemple, les travaux de Hauser et Karnovsky (1954; 1958) ont montré une réduction drastique de la synthèse des rhamnolipides chez U. maydis par l'addition de glucose, d'acétate ou d'acide tricarboxylique durant la culture, montrant le phénomène de répression catabolique. La même observation a été notée quand la concentration de glucose dépassait une certaine concentration critique lors de la production de l'acide ustilagique par Ustilago zeae (Roxburgh et al, 1954).

2.3.2. L'importance du stress sur l'induction de la synthèse des glycolipides

Généralement, la production des biosurfactants est associée à un phénomène de stress causée par une limitation d'un composant essentiel à la croissance de la cellule microbienne tel que l'azote, le phosphate et le magnésium, ou par le changement d'un paramètre physique comme le pH ou la température. Le facteur limitant le plus décrit dans la littérature comme étant la clé pour la synthèse des glycolipides est l'azote. Cet élément, est essentiel à la croissance des microorganismes et son épuisement dans le milieu de culture peut jouer un rôle prépondérant dans la production des biosurfactants. Un stress en

à produire les glycolipides sous limitation d'azote, condition atteinte après une première phase de multiplication cellulaire. Dans la deuxième procédure, ce stress est établi en transférant la biomasse cellulaire déjà cultivée dans un nouveau milieu dépourvu d'azote, après une étape de centrifugation et de lavage des cellules. Cette dernière méthode se montre plus avantageuse et bénéfique que la première lors de la production des rhamnolipides de Pseudomonas sp. DSM 2874 (Syldatk et al, 1984) et des glycolipides cellobiosiques chez U. maydis (Frautz et al, 1986). En effet, il est plus facile de contrôler les paramètres physico-chimiques tels le pH, la température, l'oxygénation, etc, de façon à promouvoir la synthèse de glycolipides dans le deuxième cas. De ce fait l'étape de transfert permet d'induire la synthèse de ce metabolite secondaire dans les conditions optimales de production. Pour ces raisons, ce procédé de biosynthèse a été choisi pour l'étude des paramètres physico-chimiques impliqués dans la production de la flocculosine (ces travaux font l'objet du premier volet de cette thèse).

3. BIOSYNTHÈSE ET IDENTIFICATION DE LA

FLOCCULOSINE

3.1. Identification des gènes impliqués dans la synthèse de la flocculosine

Au laboratoire de bio-contrôle de l'Université Laval, des mutants de la souche sauvage de P. flocculosa ont été obtenus par mutagenèse insertionnelle aléatoire suite à la mise au point d'un protocole de transformation chimique de protoplastes (Cheng et al, 2001). Bien que les transformants obtenus aient démontré une activité antagoniste inférieure à celle de la souche sauvage, les résultats de cette approche sont demeurés non concluants en raison du grand nombre d'insertions au sein du même transformant. Par la suite, Marchand et collaborateurs (2009) ont plutôt tenté d'identifier des gènes impliqués dans la synthèse de la flocculosine par recherche d'homologues trouvés chez U. maydis étant donné que ce dernier produit l'acide ustilagique, une molécule de structure chimique très similaire à celle de la flocculosine. Les travaux de Hewald et collaborateurs (2005) avaient d'abord permis d'identifier le gène cypl qui code pour une mono-oxygénase impliquée dans l'hydroxylation terminale de la chaîne d'acide gras de 16 carbones de l'acide

et codant théoriquement pour l'ensemble des enzymes nécessaires à la synthèse de l'acide ustilagique a été mis en évidence chez U. maydis (Teichmann et al, 2007). Toutes ces données ont ensuite permis la découverte de deux gènes chez P. flocculosa, cypl et uatl, potentiellement impliqués dans la synthèse de la flocculosine et ayant une forte similarité de séquence avec leurs homologues chez U. maydis (Marchand et al, 2009). Durant ces travaux de recherche, les seules séquences génétiques disponibles pour P. flocculosa et les espèces apparentées étaient les séquences d'ARN ribosomique (Avis et al, 2001) et la séquence du gène cypl (Marchand et al, 2009). Afin de compenser le manque d'information sur le génome de P. flocculosa, nous avons eu recours à la technique des gels 2-D pour étudier son comportement métabolique lors de la production de la flocculosine.

3.2. Identification des voies métaboliques via la technique des gels 2-D

L'électrophorèse 2-D est la méthode de choix pour séparer les protéines puisqu'elle permet de séparer simultanément plusieurs milliers de polypeptides d'un mélange complexe en fonction de deux propriétés différentes : la charge électrique et le poids moléculaire. Cette technique est considérée comme une méthode plus fiable que l'étude transcriptomique pour la caractérisation des sentiers métaboliques régulés une fois que la cellule est exposée à une condition environnementale particulière. En effet, plusieurs auteurs ont montré que la relation entre le niveau de l'expression transcriptomique (ARNm) et la protéine synthétisée d'un gène n'est pas corrélée suite aux processus de régulation post-transcriptionnelle ou post-traductionnelle (Gygi et al, 1999). Chez U. maydis cette technique a été utilisée pour l'étude des changements morphologiques du champignon de la forme sporidienne à la forme filamenteuse (Bôhmer et al, 2007). De même, l'identification des facteurs de virulence chez Botrytis cinerea a été effectuée par une étude comparative des profils protéiques sous deux conditions de cultures différentes (Fernandez-Acero et al, 2006).

4.1. Généralités

L'environnement des microorganismes est complexe et en perpétuel changement. De ce fait, une cellule microbienne doit être capable de répondre efficacement à des modifications de l'environnement : elle doit modifier son activité biosynthétique en réponse aux disponibilités variables des aliments. Généralement, la loi de Liebig est observée, selon laquelle la biomasse totale d'un organisme sera déterminée par l'élément nutritif présent en moindre quantité par rapport aux exigences de l'organisme.

4.2. Système écologique de Pseudozyma flocculosa

Les espèces de Pseudozyma sont pour la plupart des epiphytes. Ces champignons se développent en utilisant d'autres champignons ou plantes comme support. Il ne s'agit pas de champignons parasites car ils ne prélèvent pas de nourriture en affectant leurs hôtes. Ils occupent une niche écologique limitée et croissent habituellement dans les zones humides, à proximité des nervures et à la base des trichomes d'une feuille (Jarvis et al, 1989). Des études récentes réalisées avec la technologie Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) ont montré que le développement de P. flocculosa était favorisé par des conditions écologiques particulières. Il semble que la croissance de ce champignon à la surface des feuilles de différentes espèces végétales soit liée à la présence ou non de colonies du blanc (Neveu et al, 2007). En association avec le blanc, P. flocculosa semble pouvoir se développer abondamment, et ce, indépendamment de l'hôte végétal sur lequel le blanc se retrouve (Clément-Mathieu et al, 2008). Cependant, l'étude de l'expression du gène cypl chez P. flocculosa à la surface de feuilles infectées par le blanc a montré une répression de ce gène, suggérant ainsi que la flocculosine est synthétisée principalement au début du processus de recherche d'un nouveau substrat de croissance (Marchand et al, 2009). La compréhension du rôle écologique plausible de la flocculosine serait donc possible par le suivi de l'expression du gène cypl une fois le champignon soumis à différentes conditions environnementales. Une étude comparative avec U. maydis pourrait à cet égard être un choix judicieux.

L'hypothèse principale de ce projet de recherche était la suivante :

Il est possible de comprendre le mécanisme de production in vitro et in vivo de la flocculosine par Pseudozyma flocculosa par l'étude des facteurs et des paramètres impliqués dans le processus de sa biosynthèse.

Pour répondre à cette hypothèse, nous avons établi les objectifs suivants : Objectif 1 :

Identification des paramètres de culture qui influencent la production de la flocculosine et mise au point d'un protocole optimal pour la production de flocculosine à l'échelle expérimentale.

Objectif 2 :

Étude des changements métaboliques corrélés à la production de la flocculosine via la technique des gels 2-D.

Objectif 3 :

Détermination du rôle écologique plausible de la flocculosine via l'étude de l'expression du gène cypl.

jr c

6. REFERENCES

1. Avis, T. J., Bélanger, R. R. (2002). Mechanisms and means of detection of biocontrol activity of Pseudozyma yeasts against plant-pathogenic fungi FEMS Yeast Res 2: 5-8.

2. Avis, T. J., Caron, S. J. Boekhout, T. Hamelin, R. C. and Bélanger, R. R. (2001). Molecular and physiological analysis of the powdery mildew antagonist Pseudozyma flocculosa and related fungi. Phytopathology 91: 249-254.

3. Begerow, D., Bauer, R. Boekhout, T. (2000). Phylogenetic placements of ustilaginomycetou anamorphs as deduced from nuclear LSU rDNA sequences. Mycol Res

104: 53-60.

4. Bélanger, R. R., (2006). Controlling diseases without fungicides: A new chemical warfare. Can J Plant Pathol 28: 233-238.

5. Bôhmer, M., Colby, T. Bôhmer, C. Brautigam, A. Schmidt, J. and Bôlker, M. (2007). Proteomic analysis of dimorphic transition in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Proteomics 7: 675-685.

6. Brown, M. J., (1991). Biosurfactants for cosmetic applications. Int J Cosmet Sci 13: 61-64.

7. Cheng, Y. L., Belzile, F. Tanguay, P. Bernier, L. and Bélanger, R. R. (2001). Establishment of a gene transfer System for Pseudozyma flocculosa, an antagonistic fungus of powdery mildew fungi. Mol Gen Genom 266: 96-102.

8. Cheng, Y. L. Me, Nally, D. J. Labbé, C. Voyer, N. Belzile, F. and Bélanger R. R. (2003). Insertional mutagenesis of fungal biocontrol agent led to discovery of a rare cellobiose lipid with antifungal activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 2595-2602.

9. Clément-Mathieu, G, Chain, F. Marchand, G and Bélanger, R. R. (2008). Leaf and powdery mildew colonization by glycolipid-producing Pseudozyma species. Fung Ecol 1 : 69-77.

10. Deray, G., (2002). Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity. J Antimicrob Chemother 49: Suppl. SI, 37-41.

11. Fernandez-Acero, F. J., Jorge, I. Calvo, E. Vallejo, I. Carbu, M. Camafeita, E. Lopez, J. A. Cantoral, J. M. and Jorrin, J. (2006). Two-dimensional electrophoresis protein profile of the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Proteomics 6: 88-96.

12. Frautz, B., Lang, S. and Wagner, F. (1986). Formation of cellobiose lipids by growing and resting cells of Ustilago maydis. Biochim Lett 8: 757-762.

13. Gygi, S. P., Rochon, Y. Franza, B. R. and Aebersold, R. (1999). Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1720-1730.

14. Hajlaoui, M. R., and Bélanger, R. R. (1993). Antagonism of the yeat-lie phylloplante fungus sporothrix flocculosa against Erysiphe graminis var tritici. Biocont Sci Technol 3: 427-434.

15. Hajlaoui, M. R., and Bélanger, R. R. (1991). Comparative effects of temperature and humidity on the activity of three potential antagonists of rose powdery mildew. Neth J Plant Pathol 97: 203-208.

16. Haskins, R. H., Thorn, J. A. and Boothroyd, B. (1955). Biochemistry of the Ustilaginales. XI. Metabolic products of Ustilago zeae in submerged culture. Can J Microbiol 1:749-756.

17. Hauser, G and M. L. Karnovsky. (1954). Studies on the production of glycolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 68 : 645-654.

18. Hauser, G and M. L. Karnovsky. (1958). Studies on the biosynthesis of L-rhamnose. J Biol Chem 233:287:291.

19. Hewald, S., Josephs, K. and Bôlker, M. (2005). Genetic analysis of biosurfactant production in Ustilago maydis. Appl Environ Microbiol 171: 3033-3040.

20. Jarvis. W. R., Shaw, L. A. and Traquair, J. A. (1989). Factors affecting antagonism of cucumber powdery mildew by Stephanoascus flocculosa and S. rugulous. Mycol Res 92:

162-165.

21. Lang, S., (2002). Biological amphiphiles (microbial biosurfactants). Curr Opin Colloid Interf Sci 7:12-20.

22. Marchand, G , Rémus-Borel, W. Chain, F. Hammami, W. Belzile, F. and Bélanger, R. R. (2009). Identification of genes potentially involved in the biocontrol activity of Pseudozyma flocculosa. Phytopathology 99:1142-1149.

23. Mimée, B., Labbé, C. Pelletier, R. and Bélanger, R. R. (2005). Antifungal activity of flocculosin, a novel glycolipid isolated from Pseudozyma flocculosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemoth49: 1597-1599.

24. Neveu, B., Labbé, C. and Bélanger, R. R. (2007). GFP technology for the study of biocontrol agents in tritrophic interactions: a case study with Pseudozyma flocculosa. J Microbiol Meth 68: 275-281

25. Reisman, H., (1988), Economic Analysis of Fermentation Processes. 235 Pp. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

26. Roxburgh, J. M., Spencer, J. F. T. and Sallans, H. R. (1954). Factors affecting the production of ustilagic acid by Ustilago zeae. Subm Cult Ferm 2: 1121-1124.

27. Shigeta, A., and Yamashita, A. (1997). Modification of wheat flour products. Japanese Patent, Kao Corp., Japan, Japanese Kokai Tokyo Koho. JKXXAF, JP 61205450 A2 860911 Showa, JP 85-45850 850308.

28. Syldatck, C , Matulovic, U. and Wagner, F. (1984). Biotenside - Neue Verfahren zur mikobiellen Herstellung grenzfliichenaktiver, anionischer Glycolipide. Biotech Forum

29. Teichmann, B., Linné, U. Hewald, S. Marahiel, M. A. and Bolker, M. (2007). A biosynthetic gene cluster for a secreted cellobiose lipid with antifungal activity from Ustilago maydis. Mol Microbiol 66: 525-533.

30. Traquair, J. A., Shaw, L. A. and Jarvis, W. R. (1988). New species of Stephanoascus with Sporothrix anamorphs. Can J Bot 66: 926-933

NUTRITIONAL REGULATION AND KINETICS OF

FLOCCULOSIN SYNTHESIS BY PSEUDOZYMA

Nutritional regulation and kinetics of flocculosin synthesis by

Pseudozyma flocculosa

This article has been published in Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, volume 80 (2008), pp. 307-315.

The authors are Walid Hammami1, Caroline Labbé1, Florian Chain1, Benjamin

Mimee1 and Richard R. Bélanger2

(1) Centre de recherche en horticulture, Université Laval, Québec, Canada

(2) Département de Phytologie, Centre de recherche en horticulture, Université Laval, Québec, Canada, GI V 0A6.

RÉSUMÉ

Cette étude avait pour objectif d'identifier les conditions de culture qui affectent la production de la flocculosine, un glycolipide doté d'une activité antifongique et synthétisé par l'agent de lutte biologique Pseudozyma flocculosa. Afin d'atteindre cet objectif, plusieurs paramètres théoriquement impliqués dans la production des glycolipides par d'autres champignons ont été testés. La concentration de l'inoculum de départ a joué un rôle majeur dans la production de la flocculosine, permettant ainsi d'augmenter le niveau de production d'un facteur 10. La disponibilité d'une source de carbone ainsi que la source de l'azote (organique versus inorganique) ont également influencé le métabolisme de P. flocculosa conduisant à la synthèse de la flocculosine. En général, la disponibilité d'une source de carbone semble être le seul facteur limitant après le démarrage de cette production. D'autre part, suite à l'addition d'extrait de levure au milieu de culture, le champignon a repris la production de biomasse au détriment de la synthèse de flocculosine. Contrairement à ce qui a été décrit chez d'autres champignons producteurs de glycolipides, une limitation d'azote inorganique n'a pas entraîné la production de flocculosine. La relation entre les facteurs influençant cette production in vitro et les conditions affectant la synthèse de la molécule par P. flocculosa dans son habitat naturel semble être associée à une disponibilité de nutriments appropriés pour l'agent de lutte biologique au sein de la phyllosphère.

ABSTRACT

This study sought to identify the factors and conditions that affected production of the antifungal glycolipid flocculosin by the biocontrol agent Pseudozyma flocculosa. For this purpose, different parameters known or reported to influence glycolipid release in fungi were tested. Concentration of the start-up inoculum was found to play an important role in flocculosin production as the optimal level increased productivity by as much as 10-fold. Carbon availability and nitrogen source (i.e. organic vs inorganic) both had a direct influence on the metabolism of P. flocculosa leading to flocculosin synthesis. In general, if conditions were conducive for production of the glycolipid, carbon availability appeared to be the only limiting factor. On the other hand, if yeast extract was supplied as nitrogen source, fungal biomass was immediately stimulated to the detriment of flocculosin synthesis. Unlike other reports of glycolipid release by yeast-like fungi, inorganic nitrogen starvation did not trigger production of flocculosin. The relationship between the factors influencing flocculosin production in vitro and the conditions affecting the release of the molecule by P. flocculosa in its natural habitat appears to be linked to the availability of a suitable and plentiful food source for the biocontrol agent.

1. INTRODUCTION

The fungus Pseudozyma flocculosa (Traquair, Shaw, and Jarvis) Boekhout and Traquair is known for its biocontrol activity against many powdery mildew species (Bélanger and Labbé 2002). While antibiosis was initially suggested as its mode of action (Hajlaoui et al, 1994), it took several years to identify a molecule responsible, at least in part, for this activity. A new cellobiose-lipid, named flocculosin, was purified from solid culture medium of P. flocculosa and was shown to possess an important antifungal activity in vitro (Cheng et al, 2003). The structure of flocculosin was found to be closely related to one of the glycolipids produced by Ustilago maydis; ustilagic acid (Mimée et al, 2005).

Flocculosin, as well as ustilagic acids, are part of a well-characterized class of natural products called biosurfactants. There is a wide range of industrial applications for biosurfactants and they have potential uses in several fields including medicine, bioremediation of soils, etc. (Desai and Desai 1993; Mimée et al, 2005). Though glycolipids produced by microorganisms are fairly common in nature (Rosenberg 1986), cellobiose lipids are rather unusual. Recently, a metabolic pathway of ustilagic acid production by U. maydis was proposed (Teichmann et al, 2007). These authors associated several genes to different metabolic activities such as hydroxylation of palmitic acid, acylation, and acetylation of cellobiose for instance, all activities essential for the proper synthesis of the different ustilagic acids found in U. maydis. They showed that these genes were part of a cluster and suggested that they were induced by nitrogen (N) stress based on the depletion of the element in the medium (Teichmann et al, 2007). Reiser et al. (1989) had previously reported that glycolipid synthesis was observed under conditions of N limitation in U. maydis and N. erythropolis. In P. aphidis, it was shown that mannosylerythritol lipids (MELs) production could only occur after nitrate limitation and that this induction was not reversed by nitrate addition (Rau et al, 2005). Furthermore, Frautz et al, (1986) found that glycolipid production could begin only after complete utilization of urea i.e. under N-limitation. On the other hand, Syldatk and Wagner (1987) suggested that N limitation was not specific but rather coincidental with the depletion of other essential elements in the medium (e.g. Fe, Mg, Ca) that induced glycolipid production.

Among other factors reported to modify glycolipid synthesis, the carbon source has been mentioned (Davila et al, 1997). For example, ustilagic acid production by U. maydis is presumably dependent on the presence of glucose in the medium, while fatty acids (sunflower oil) will lead to production of MELs (Spoeckner et al, 1999). The cellular stage of the culture, i.e. resting cells vs growing cells, also has been suggested to greatly influence the capacity of the organism to synthesize secondary metabolites such as glycolipids. In previous studies with Ustilaginales, better glycolipid production rates were obtained with resting cells fed with carbohydrates (Syldatk and Wagner 1987; Kitamoto et al, 1992).

The previous literature exemplifies our limited understanding of glycolipid production in fungi in general and in P. flocculosa in particular. Since flocculosin is very similar in structure to ustilagic acids, and P. flocculosa is closely related genetically to U. maydis, we hypothesized that flocculosin production would be influenced by the same factors reported for ustilagic acids. To verify this, the objective of the present work was to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the factors potentially important in glycolipid production in P. flocculosa. In addition, we surmised that the impact of those factors would provide insights into the ecological role of flocculosin and its link to the biocontrol activity of P. flocculosa in its natural habitat.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Fungal material

P. flocculosa (DAOM 196992) was used throughout this study. Stock cultures were conidia lyophilized in maltose (20%) and kept at -80°C as aliquots of ca. 1 X 106 cells.

Mother cultures were obtained by inoculating 100 ml YMPD medium (yeast extract 3 g/1, malt extract 3 g/1, peptone water 5 g/1 and dextrose 10 g/1) in a 500 ml baffled flask with one bottle of lyophilized culture previously hydrated with 3 ml of sterile water. All culture media ingredients were supplied by Difco (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Seed cultures were prepared by inoculating 100 ml of YMPD medium with 5 ml of a 3-day-old mother culture. The seed cultures were maintained on a rotary shaker set at 150

rev/min at room temperature and were transferred in fresh medium every three days for a maximum period of 30 days.

2.2. Preparation of fungal cells for flocculosin production

From 3-day old seed cultures, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5300g for 5 min and washed with saline (0.9% NaCl). After a second centrifugation (5300g for 5 min) washed cells were transferred into 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks equipped with baffles and containing 100 ml of medium. A basic culture medium (MOD medium), previously developed in our laboratory (Mimée et a l 2005) was used as a starting medium for all experiments. Briefly, it contained 35 g/1 sucrose, 1 g/1 (NH4)2 S04, 1 g/1 KH2P04, 0.5 g/1 MgS04-7H20, 0.01 g/1 FeS04.7H20 added to 50 mM citrate buffer consisting of 12.85 g/1 sodium citrate dihydrate and 1.21 g/1 citric acid to maintain the pH at 6.0. The pH was monitored every 24 h. Flasks were incubated in a controlled temperature chamber (28°C) and shaken at 150 rpm on rotary shakers.

2.3. Density of start-up inoculum

The effect of inoculum density on flocculosin production was evaluated by testing different start-up concentrations (between 0.2 g/1 and 1.4 g/1 dry cell weight) in a buffered MOD medium. Flocculosin concentration was measured every 24 h. Residual sugars were recorded every 24 h for five days by HPLC as described below.

2.4. Effect of carbon (C) content

Concentrated solutions of sucrose (70%) were sterilized separately and used to study the effect of carbon addition on flocculosin production. This concentrated solution was supplied to 5-day-old cultures to obtain 14 g/1 sucrose. The addition of this component was carried out by the substitution of a volume of the culture by an equal volume of the concentrated solution in order to preserve a constant cell concentration of culture. One-ml aliquots from cultures were collected when needed and immediately centrifuged at 5300g for 5 min. Supernatants were kept at -20°C prior to analyses. Residual C (glucose and fructose) was analyzed by HPLC (Waters Model 600) on a Waters Sugar-Pac-I column (Waters Ltd Mississauga, On, Canada) coupled to a refractometer (LKB Model 2142).

Elution was performed isocratically with a solution of EDTA (50 mg/1) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min at 90°C for 30 min.

2.5. Nitrogen source and concentration effect

Both the source and concentration of N were evaluated for their impact on flocculosin production. (NH4)2S04 was used as inorganic N source. In the first step, two concentrations were compared: 1 g/1 and 2 g/1. Residual ammonium was measured according to the Kjeldahl method (Nkonge and Balance 1982). Yeast extract (YE; 10.9% N content) was chosen as organic N source. Two concentrations were tested (0.5 g/1 and 2 g/1). Moreover, to study the effect of YE addition on flocculosin synthesis, concentrated solutions of YE (20%) were sterilized separately and used in a fed-batch experiment on 24-h-old cultures in buffered MOD medium.

2.6. Dosage of flocculosin 2.6.1. Sample preparation

One-ml aliquots from P. flocculosa cultures were collected when needed and immediately centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min. The supernatants were removed and 1 ml of CH30H was added to the pellets. Tubes were vortexed and centrifuged at 10,000g for an additional 5 min. Supernatants were kept at -20°C prior to HPLC analyses.

2.6.2. Preparation of flocculosin standard

Purified flocculosin was obtained according to Mimée et al, (2005). Briefly, a 3-day-old culture of P. flocculosa grown in MOD medium was acidified to pH 2 with HC1 37%, and filtered with a Buchner funnel. Flocculosin, not soluble in water, was retained in the filter paper (Whatman no 1) with the fungal cells. This filtrate cake was rinsed thoroughly with distilled water to remove hydrophilic compounds and acid traces. Then, CH30H (ca. 300 ml) was used to solubilize and elute flocculosin from the cell material. Fifty ml of deionized water were added to the methanol filtrate and this preparation was roto-evaporated to remove all traces of solvent. The resulting aqueous fraction was then

lyophilized into a white powder containing purified flocculosin (95%+). Methanolic aliquots from 0.5 to 2.5 g/1 were used to define the standard curve.

2.6.3. HPLC analyses

A HPLC (Agilent, 1100 series) coupled with an ELSD detector (Sedere, Sedex 75, France) was used for flocculosin quantification. Flocculosin was eluted on a C8 column (ZORBAX, Eclipse XDB-C8; 4.6 x 150 mm) with the following linear gradient: 40:60 CH30H:water to 80:20 CH30H:water at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min for 20 ran. Under those conditions, flocculosin was eluted at ca. 13 mn.

2.7. Determination of cell dry weight

To quantify precisely the amount of biomass (dry) used to inoculate the culture medium, 5 ml of seed culture were harvested by centrifugation at 5300g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were mixed with 2.5 ml sterilized water. The dry biomass was measured with a halogen drying balance (Mettler Toledo, Model HR 83, VWR Canada). To determine cell dry weight (c.d.w.) during flocculosin production, an additional step of washing/centrifugation with CH30H was added prior to the final wash with water to eliminate flocculosin from dry matter.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Density of start-up inoculum and effect of carbon content

In order to determine the effect of start-up inoculum on the production of flocculosin, different concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1.4 g (c.d.w)/l were tested (Figure la). The highest production was obtained with an initial inoculum weight of 0.4 g/1. Beyond that level, flocculosin production stopped rapidly and its concentration even started to drop after 48 h to completely disappear after 120 h with 1.4 g (c.d.w.) II.

Total sugar analyses revealed expectedly that the highest concentration of start-up inoculum consumed sugars at a faster rate and that flocculosin production was linked with C availability (Figure lb). Treatments with 0.2 and 0.4 g/1 revealed plump mycelial

fragments with needle-like structures typical of flocculosin presence. By contrast, total C consumption after 96 h in the treatments 0.8 and 1.4 g (c.d.w.)/l, yielded a mixture of conidia and pseudomycelium. This coincided with a reduction in flocculosin concentration and a pH increase to 7.2 and 7.8, respectively. Based on these results, the start-up inoculum concentration was set at 0.4 g (c.d.w.)/l in the next experiments.

Carbohydrate consumption showed that sucrose was first quickly hydrolyzed into glucose and fructose within the first 24 h and that glucose was used preferentially throughout the experiment (Figure 2). A similar pattern of C consumption was observed with different start-up inocula (not shown). Fungal biomass appeared to be inversely proportional with glucose concentration in the medium. Fructose presence did not seem to have any impact on biomass production (Figure 2). In the same manner, flocculosin production slowed down as glucose became depleted. On the other hand, the addition of 14 g/1 of sucrose after 5 days of culture resumed flocculosin production, which reached ca. 15 g/1 after 168 h of culture (Figure 3).

3.2. Effect of nitrogen concentration

Inorganic N concentration was recorded along with flocculosin production in order to analyze its potential effect on flocculosin synthesis (Figure 4). With 1 g/1, ammonium was nearly totally used up by P. flocculosa within 24 h. With 2 g/1, there was a rapid consumption of ammonium within the first 24 h and the concentration remained fairly stable thereafter. Surprisingly, cell growth and flocculosin production were not influenced by the two different concentrations of ammonium used in the medium as it progressed similarly under the two regimes even with residual presence of ammonium with a start-up concentration of 2 g/1.

3.3. Effect of yeast extract

When YE (2 g/1) was added to the medium, C consumption followed exactly the same pattern as observed with a YE-free medium. Glucose was used up in less than 48 h (Figure 5). Also, fungal biomass exceeded 10 g/1, a 30% increase compared to the control medium. However, the presence of YE inhibited the production of flocculosin over the

experimental period (Figure 5). If YE was added as a fedbatch at t24h, microscopy observations indicated that a shift in fungal morphology occurred (Figure 6, a-d); the hyphae became thinner and shorter than those of the controls as early as 24 h after YE fedbatch. Additionally, in cultures receiving YE, we also observed a gradual disappearance of the needle-like structures (see arrows) typical of flocculosin presence (Figure 6). By 96 h, the biomass was nearly exclusively composed of conidia without flocculosin (Figure 6, d). By contrast, plump mycelial fragments, accompanied by needle-like structures characterized cultures free of YE (Figure 6, g). When yeast nitrogen base, i.e. w/o amino acids and ammonium sulfate, was used in order to determine if organic N was the factor responsible for the shift, we obtained the same exact results as those obtained with yeast extract (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

Results from this study have highlighted the importance of several parameters in the production of flocculosin by the biocontrol agent P. flocculosa, a molecule of important microbiological and medical interest because of its putative role in the antagonistic properties oi P. flocculosa and its reported antimicrobial activity. Taken together these data could facilitate commercial production of the molecule and help define the ecological conditions triggering the release of flocculosin for the benefit of P. flocculosa.

Study of inoculum density showed expectedly that sugar consumption was proportional to cell density. In contrast, the relation between inoculum density and flocculosin production was not directly proportional. It was observed that 0.4 g/1 was the optimal start-up inoculum size for flocculosin production under our conditions. Below that level, it was reduced while above that level, it not only stopped but it started to decrease rapidly. This suggests that P. flocculosa must first reach a specific physiological state prior to start producing flocculosin, a highly demanding energetic requirement that was not fulfilled at higher cell density under our experimental parameters. Of additional importance, these results showed that the fungus appeared to degrade its own secondary metabolites when no other C source was available. While no enzymes capable of degrading flocculosin have been reported yet, Eveleigh et al, (1964) described the release of enzymes

capable of degrading ustilagic acid by fungi such as Fusarium species. The authors surmised that those fungi avoided the deleterious effect of cellobiose lipids in an effort to maintain their ecological niche. This could thus explain why flocculosin has no adverse effect against P. flocculosa itself.

Studies of C source revealed that glucose was preferentially consumed by P. flocculosa for production of both flocculosin and biomass. Thereafter, the fructose fraction

was seemingly used mostly for flocculosin production. In addition, when sucrose was re-supplied after its exhaustion (see Figure 3), flocculosin production resumed and reached as much 15.4 g/1. This phenomenon showed that the activity of the cells (having reached the specific physiological state for flocculosin production) remained high enough for the production of flocculosin when the C source was available in the medium. Moreover, the depletion of the C source over time led to the decrease of flocculosin concentration. This further supports the hypothesis raised earlier that flocculosin could be utilized as a C source for further metabolic activities of the fungi. This phenomenon was described for other fungi which excrete enzymes to degrade their secondary metabolites after the exhaustion of C in the medium (Steiner et al, 1993). According to our results, it appears that the presence of carbohydrates has an impact on both induction and yield of flocculosin synthesis. Yamouchi et a l , (1983) showed that fungal cells required the exhaustion of various elements in the medium to allow the excess C to be channeled into lipids. This result could be helpful to understand the biosynthetic route of flocculosin which contains long fatty acid chains. Indeed, Granger et al, (1993) showed that the exhaustion of the limiting medium element as N, phosphorus, zinc or iron resulted in an enhancement of both the fatty acid cell content and the corresponding productivity in the oleaginous yeast.

Our results, showing that the addition of N did not influence flocculosin synthesis, are somewhat surprising. It is well known that N availability has a profound impact on the biology and environmental persistence of fungi (Lengeler et al, 2000). Previous studies also indicated that the production of glycolipids was induced by N stress (Reiser et al

1989). More specifically, the production in vitro of ustilagic acid by U. maydis has been associated with N depletion (Frautz et a l , 1986; Hewald et al, 2005). Accordingly, by doubling the N (ammonium sulfate) concentration in the medium, we expected that

flocculosin production would be delayed or inhibited, which was not the case (see Figure 4). However, N consumption came to halt after 48 h even with residual presence in the medium. This could mean that, when the enzymatic machinery is in place, the fungus no longer requires N for producing flocculosin. Therefore, production would be more dictated by a physiological condition than by N stress, events that coincided in previous reports.

Under our experimental conditions, the addition of YE to the medium led to a complete inhibition of flocculosin synthesis to the profit of biomass. YE is a good source of free amino acids (lysine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, threonine and phenylalanine), nucleotides and vitamins (Dimmling and Nesemann 1985) and thus supplies all the minimal requirements for growth. This addition was also accompanied with a change in cell morphology. Moreover, it was interesting to note that the process of flocculosin production was reversible as soon as YE was added. We therefore hypothesized that organic N instead of inorganic N was the factor that could act as a switch between flocculosin production and cell growth. However, the utilization of YE nitrogen base (N-free) gave the same results thus suggesting that the answer lied at another level. We can surmise that the metabolic pathways supporting the production of the biomass are activated in the presence of a factor from YE, thus leading to the rapid production of conidia rather than flocculosin. When growth is blocked by a stress, i.e. the absence of that factor, flocculosin excretion might constitute an overflow metabolism for the yeast, which regulates the intracellular energy level. This hypothesis was proposed for sophorose lipid production by Candida bombicola (Davila et al, 1997). So the limited formation of flocculosin, which has high energy content, appears to be related to the lower energetic level of the cell.

Based on results obtained in this study, a summary of factors influencing flocculosin production is proposed in Figure 7. As a first step, P. flocculosa needs sugars and N to change its morphology either for flocculosin production or cellular growth. This explains why a high inoculum density failed to produce more flocculosin since sugars are first required to make the morphological change. As a second step, if P. flocculosa is provided with more sugars, regardless of the presence of N, flocculosin synthesis is switched on and will continue until sugar depletion. However, if YE is supplied with sugars, cellular growth

is favored over flocculosin. From a practical perspective, inferences can be made linking our observations with the ecological behaviour of P. flocculosa. This fungus is known as an epiphyte and found in very low concentrations in leaf veins of certain plant species (Traquair et al, 1988; Avis and Bélanger 2002). However, when measured in presence of powdery mildew infected plants, Dik et al, (1998) showed that the population density of P. flocculosa was always higher. More recently, Neveu et al, (2007) demonstrated that the

presence of a GFP-expressing strain of P. flocculosa was closely associated and quantitatively enhanced with powdery mildew colonies. In absence of the pathogen, P. flocculosa was barely visible, which would indicate that a growth factor from powdery

mildew fungi, similar to the one in YE, stimulates the development of P. flocculosa. Given that flocculosin synthesis is enhanced in conditions of stress it is likely that flocculosin production occurs when P. flocculosa is within .its limited epiphytic habitat, production which in turn would be sufficient to prevent invasion of its ecological niche by competitors such as powdery mildew fungi. Release of nutrients from the damaged fungi can thus constitute a feeding source for P. flocculosa, thus shifting the metabolism towards the production of biomass allowing a population density to increase until the disappearance of the pathogen. This coincides with a morphological change from the filamentous form to the yeast-like form as observed in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Canada Research Chairs Program to R.R. Bélanger.

5. REFERENCES

1. Avis TJ, Bélanger RR (2002) Mechanisms and means of detection of biocontrol activity of Pseudozyma yeasts against plant-pathogenic fungi. FEMS Yeast Res 2: 5-8 2. Bélanger RR, Labbé C (2002) Control of powdery mildews without chemicals: prophylactic and biological alternatives for horticultural crops. Bélanger RR, Bushnell WR, Dik AJ, Carver TLW (eds). In: The Powdery Mildews: A comprehensive treatise. APS Press, St. Paul, Minnesota pp 256-267

3. Cheng Y, McNally DJ, Labbé C, Voyer N, Belzile F, Bélanger RR (2003) Insertional mutagenesis of a fungal biocontrol agent led to discovery of a rare cellobiose lipid with antifungal activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 2595-2602

4. Desai J, Desai AJ (1993) Production of biosurfactants. In Kosaric N (ed) Biosurfactant Production Properties Applications. Marcel Dekker, Inc. New York, pp 66-92 5. Davila AM, Marchai R, Vandecasteele JP (1997) Sophorose lipid fermentation with diffentiated substrate supply for growth and production phase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 47: 496-501

6. Dik AJ, Verhaar MA, Bélanger RR (1998) Comparison of three biological control agents against cucumber powdery mildew (Sphaeroteca fuligined) in semi-commercial-scale glasshouse trials. Eur J Plant Pathol 104: 413-423

7. Dimmling W, Nesemann G (1985) Critical assessment of feedstocks for biotechnology. CRC Critical Rev Biotechnol 2: 233-285

8. Eveleigh DE, Dateo GP, Reese ET (1964) Fungal metabolism of complex glycosides: Ustilagic Acid. J Bio Chem 239: 839-844

9. Frautz B, Lang S, Wagner F (1986) Formation of cellobiose lipids by growing and resting cells of Ustilago maydis. Biotechnol Lett 8: 757-762

10. Granger LM, Perlot P, Goma G, Pareilleux A (1993) Effect of various nutrient limitations on fatty acid production by Rhodotorula glutinis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 38: 784-789

11. Hajlaoui MR, Traquair JA, Jarvis WR, Bélanger RR (1994) Antifungal activity of extracellular metabolites produced by Sporothrix flocculosa. Biocontrol Sci Technol 4:229-237

12. Hewald S, Josephs K, Bôlker M (2005) Genetic analyses of biosurfactant production in Ustilago maydis. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 3033-3040

13. Lengeler K, Davidson R, D'Souza R, Harashima T, Shen W, Wang P, Pan X, Waugh M, Heutman J (2000) Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol 64: 746-785

14. Mimée B, Labbé C, Pelletier R, Bélanger RR (2005) Antifungal activity of flocculosin, a novel glycolipid isolated from Pseudozyma flocculosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1597-1599

15. Neveu B, Labbé C, Bélanger RR (2007) GFP technology for the study of biocontrol agents in tritrophic interactions: A case study with Pseudozyma flocculosa. J Microbiol Meth 68: 275-281

16. Nkonge C, Balance GM (1982) A sensitive colorimetric procedure for nitrogen determination in micro Kjeldahl digest. J Agric Food Chem 30: 416-420

17. Rau UL, Nguyen A, Roeper H, Koch H, Lang S (2005) Fed-batch bioreactor production of mannosylerythritol lipids secreted by Pseudozyma aphidis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68: 607-613

18. Reiser J, Koch AK, Jenny K, Kappeli O (1989) Structure, properties, and biosurfactants. In Orbringer JW, Tillinghast HS (eds) Biotechnology for Aerospace Applications vol 3, Portfolio Publishing Company, The Woodlands, Tex, pp 85-97

20. Spoeckner S, Wray V, Nimtz M, Lang S (1999) Glycolipids of the smut fungus Ustilago maydis from cultivation on renewable resources. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 51: 33-39

21. Steiner W, Haltrich D, Lafferty RM (1993) Production, properties and pratical applications of fungal polysaccharides. In: Kosaric N (ed) Biosurfactant Production. Properties. Applications. Marcel Dekker, Inc. New York, pp 176-199

22. Syldatk T, Wagner F (1987) Production of biosurfactants. In: Kosaric N, Cairns WL, Gray CC (eds) Biosurfactant and Biotechnology, Surfactant Science Series. Vol 25, Marcel Dekker, Inc. New York, pp 89-120

23. Traquair JA, Shaw LA, Jarvis WR (1988) New species of Stephanoascus with Sporothrix Anamorphs. Can J Bot 66: 926-933

24. Teichmann B, Linné U, Hewald S, Marahiel MA, Bôlker M (2007) A biosynthetic gene cluster for a secreted cellobiose lipid with antifungal activity from Ustilago maydis. Mol Microbiol 66: 525-533

25. Yamouchi H, Mori H, Kobayashi T, Shimizu S (1983) Mass production of lipids by Lipomyces starkeyi in microcomputer-aided fed-batch culture. J Ferment Technol 61: 275-280

60 80

Time (h)

Figure 1. Effect of inoculum size on (a) flocculosin production and (b) on sugar consumption by Pseudozyma flocculosa cultured on citrate-buffered MOD medium.

—♦-(0.2 g d.m./l), -m- (0.4 g d.m./l), - * - (0.8 g d.m./l) and - • - (1.4 g d.m./l). Each value represents the average of three replicates ± standard error.

«50 80

Time (h)

Figure 2. Sucrose (glucose and fructose) consumption and biomass production during flocculosin synthesis by Pseudozyma flocculosa with 0.4 g dry cell/1 inoculum in buffered

MOD medium. Each value represents the average of three replicates ± standard error.

16-14- q

I -

\ ^ 0 ^l/

j-j.10 \ ^ CJ) \ \ s * ~~" 8 - \ . »N O 6 - X ^ ^ I \ _J > S \ U ^ F \ i \ë

4 y ^ i t i I 1 / N 1 N. 2 N ^ D 0 - r>- = ~ 4 30 33 n 25 £. Q. c OJ c 15 Si 10 3 5 a i 20 40 80 80 100 120 140 160 180 Time (h)Figure 3. Effect of a sucrose fedbatch (14 g/1) (arrow) after its depletion (120 h old culture) on flocculosin synthesis by Pseudozyma flocculosa.

10-r 9 8 ^ 7 5? 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 o 3 u u O A (NH4)2S04 (1 g/1) . (NH4)2S04 (2 g/1) 48 72 Time (h) 120 0.6 33 a> VI o.5 5; c BL 0.4 û» 3 3 0.3 O c' 0.2 3 ^-. 0.1 V

Figure 4. Influence of nitrogen concentration ((NH4)2S04) on flocculosin synthesis by Pseudozyma flocculosa over time. Each value represents the average of three replicates ±

standard error. Cd.w. Flocculosin Residual glucose Residual fructose 96 120

Figure 5. Effect of yeast extract when added at tO to the buffered MOD medium on biomass production, sucrose (glucose and fructose) consumption and flocculosin synthesis

by Pseudozyma flocculosa culture. Each value represents the average of three replicates; standard error bars are smaller than 0.15.

y ' y ? '

mA

' / * ■. . . , Lj-i. -

NFigure 6. Morphological changes ofPseudozyma flocculosa cells and flocculosin production into the buffered MOD medium amended (b, d, f) or not (c, e, g) with YE at

^ I,

Nitrogen source (organic or inorganic)

w or w/o nitrogen source

Mycelial fragments with budding conidia that are associated with

flocculosin production

«Jte>

*i

wot w/o nitrogen source « ï £ YE or YE nitrogen base + nitrogen source YE or YE nitrogen base + nitrogen source FlocculosinFigure 7. Influence of yeast extract (YE) amendment and nitrogen source availability on physiological changes ofPseudozyma flocculosa when grown in presence of a non-limiting

carbon source (sucrose, glucose or fructose). Large short arrows indicate a fed-batch addition. Boxes enclose descriptive comments.

PROTEOMIC ANALYSIS OF METABOLIC

ADAPTATION OF THE BIOCONTROL AGENT

PSEUDOZYMA FLOCCULOSA LEADING TO GLYCOLIPID

PRODUCTION

Proteomic analysis of metabolic transition in flocculosin synthesis by the

biocontrol agent Pseudozyma flocculosa

This article has been published in Proteome Science, Volume 8 (2010). The authors are Walid Hammami, Florian Chain, Dominique Michaud and Richard R. Bélanger*.

Centre de recherche en horticulture, Université Laval, Québec, Canada

Corresponding author.

Mailing address : Département de Phytologie, Centre de recherche en horticulture, Université Laval, Québec, Canada G1V 0A6. Phone : (418) 656-2758.

Fax:(418)656-7871.

E-mail : richard.belanger@fsaa.ulaval.ca

RÉSUMÉ

Le champignon levuroïde Pseudozyma flocculosa est reconnu pour synthétiser la flocculosine, un glycolipide à activité antifongique probablement impliqué dans l'activité antagoniste du champignon à l'égard de la maladie du blanc. En conditions de culture, la production de flocculosine est fonction de la disponibilité ou non de certains nutriments. Dans le but de comprendre et de caractériser les changements métaboliques corrélés à la synthèse de la flocculosine, nous avons effectué une analyse protéomique 2-D afin de comparer les profils protéomiques du champignon cultivé en conditions favorisant sa croissance (témoin) ou la synthèse de la flocculosine (stress). Comparativement au milieu témoin, où un grand nombre de spots protéiques ont été identifiés sur les gels (771), seulement 435 spots ont été détectés à partir du milieu de synthèse de la flocculosine. Ce résultat suggère ainsi une réorganisation métabolique des cellules sécrétant cette molécule. Nous avons pu identifier 21 protéines qui étaient soit spécifiques à ce milieu de culture ou soit sur-exprimées d'au moins un facteur 2. L'identification de la plupart de ces protéines a été possible grâce à leur homologie de séquences entre les cadres de lecture ouverts (ORF) prédits du génome nouvellement séquence de P. flocculosa et ceux annotés du génome a.'Ustilago maydis. Ces protéines étaient pour la plupart associées au métabolisme du carbone et des acides gras. Quelques-unes étaient également liées au changement morphologique filamenteux de P. flocculosa, qui précède la synthèse de la flocculosine. Cette première analyse du protéome de P. flocculosa suggère que la synthèse de la flocculosine est induite en réponse à des stress ou lors de conditions limitantes spécifiques.

ABSTRACT

The yeast-like epiphytic fungus Pseudozyma flocculosa, is known to antagonize powdery mildew fungi through proliferation on colonies presumably preceded by the release of an antifungal glycolipid (flocculosin). In culture conditions, P. flocculosa can be induced to produce or not flocculosin through manipulation of the culture medium nutrients. In order to characterize and understand the metabolic changes in P. flocculosa linked to glycolipid production, we conducted a 2-DE proteomic analysis and compared the proteomic profile of P. flocculosa growing under conditions favoring the development of the fungus (control) or conducive to flocculosin synthesis (stress). A large number of protein spots (771) were detected in protein extracts of the control treatment compared to only 435 matched protein spots in extracts of the stress cultures, which clearly suggests an important metabolic reorganization in slow-growing cells producing flocculosin. From the latter treatment, we were able to identify 21 protein spots that were either specific to the treatment or up-regulated significantly (2-fold increase). All of them were identified based on similarity between predicted ORE of the newly sequenced genome of P. flocculosa with Ustilago maydis ' available annotated sequences. These proteins were associated with the carbon and fatty acid metabolism, and also with the filamentous change of the fungus leading to flocculosin production. This first look into the proteome of P. flocculosa suggests that flocculosin synthesis is elicited in response to specific stress or limiting conditions.