O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 16587

To link to this article : DOI:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.08.001

URL :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.08.001

To cite this version :

Marder, Rachel and Estournès, Claude and

Chevallier, Geoffroy and Chaim, Rachman Spark and plasma in

spark plasma sintering of rigid ceramic nanoparticles: A model

system of YAG. (2014) Journal of the European Ceramic Society,

vol. 35 (n° 1). pp. 211-218. ISSN 0955-2219

Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

Spark

and

plasma

in

spark

plasma

sintering

of

rigid

ceramic

nanoparticles:

A

model

system

of

YAG

R.

Marder

a,∗,

C.

Estournès

b,c,

G.

Chevallier

b,c,

R.

Chaim

a aDepartmentofMaterialsScienceandEngineering,Technion–IsraelInstituteofTechnology,Haifa32000,Israel bUniversitédeToulouse,UPS,INP,InstitutCarnotCirimat,118,routedeNarbonne,F-31062ToulouseCedex9,FrancecCNRS,InstitutCarnotCirimat,F-31062Toulouse,France

Abstract

Yttriumaluminumgarnet(YAG)nano-particlesweresparkplasmasinteredbetween1100◦Cand1400◦Cunder2–100MPapressurewithout isothermaltreatments.Thespanofrelativedensitybetween48%and99%enabledmicrostructuralexaminationatdifferentstagesofthedensification. Electronmicroscopyexaminationshowedmaterialjetswithamorphouscharacterconnectingbetweenthesphericalnano-particles,whichwere relatedtosurfacemelting.Alignednano-particleswithinthenano-clusters,apparentlyaffectedbyhighlocalelectricfields,wereobservedin thepartiallydensemicrostructure.Rapiddensificationfrom1200◦Cwasrelatedtodensificationbynano-particleslidingandrotationassisted bysurfacesoftening.TheobservedmicrostructuralfeatureswerediscussedwithrespecttosparkingandplasmaformationduringtheSPS.The occurrenceofplasmawasexplainedbymeansoftheplasmaformation-plasticdeformationdiagram.

©2014ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Keywords:Plasma;Sparkplasmasintering;Densification;Powderconsolidation;YAG

1. Introduction

Sparkplasmasintering(SPS)andotherelectricfieldassisted sinteringtechniquesbecomemorewidespreadforrapid fabrica-tionofsimple-andcomplex-shapeceramicparts(seereview1). Thisisevidenced bythemany patentsregisteredinthisfield inrecentyears.2 Therefore,correct application of these tech-niques for efficient fabrication of the ceramic articles with controlledmicrostructureandpropertiesbecomehighpriority. Thisnecessitatesdeterminationofthesinteringand densifica-tion mechanisms active during the SPS, with respect to the composition and microstructure of the ceramic powder and theprocessparameters.Severaldifferentatomisticmechanisms wereproposedfortherapidsintering,densification,andgrain

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+97248294290;fax:+97248295677.

E-mailaddresses:rachelma@technion.ac.il,rachel.marder@gmail.com

(R.Marder).

growth (orits inhibition)innano-ceramic powders.3–9 Tokita was among the first to point out that spark andplasma can alsobeactiveinnon-conductingceramics.6,10Thedebateabout thepresenceorlackofsparkingandplasmainnon-conducting ceramiccompactshasbeenchallengedbythelocalmeltingand materialjetsreportedinseveraldifferentceramicssubjectedto SPS.11–13 Recently,asimplemodelfor dischargeandplasma formationduringtheSPSwasputforward,usingthe percola-tivenatureofthe electriccurrent inthegranulardielectrics.14 Twoonsettemperaturesforactivationofeitherplastic deforma-tionorenhanceddiffusionviaparticlesurfacemelting/softening duetoplasma,weredetermined;thelowertemperatureamong the two determinesthe densification mechanism to be active first.TheenhancedshrinkageinLiFmicrocrystalsatpressures below the yieldstress was consistentwiththeseexpectations for spark dischargeand plasma heating atlow pressuresand temperatures.15

ThepresentpaperreportsthedensificationofYAGasarigid modelsystemfornano-particlecompactssubjectedtoSPSwith

Table1

TheSPSconditionsandspecimensfinaldensities.

nc-YAGpowder SPStemperature[◦C] Pressure[MPa] Finalrelativedensity[%] Grainsize[nm]

Asreceived(AR) 1100 2 45.5 1100 32 51.8 1100 64 54.6 1100 100 60.1 90±33 1200 2 43.7 1200 100 61.9 92±43 1250 100 67.7 96±38 1300 100 73.9 115±34 1350 100 87.7 138±41 1400 2 70.8 1400 100 99.0 325±121 Heattreated(HT) 1100 2 46.1 1100 100 50.8

clear microstructureevidencefor surfacemeltingvia plasma. Theoccurrenceofdischargesparkfollowedbyplasmaheating wasanalyzedfollowingapercolativecurrentmodelingranular dielectriccompacts.

2. Experimental

Purecommercialnano-crystallineYttriumAluminumGarnet (nc-YAG)powder(Nanocerox,USA)withspherical morphol-ogy andameancrystallitesize (diameter)of 70±50nmwas used.Thepowderwasusedintheas-receivedform(AR-powder) andafterheattreatment(HT-powder)for2hinairat1000◦C.

Discs of 8mm in diameter werefabricated using the SPS unit(Dr.Sinter,SPS2080)attheNationaleCNRSdeFrittage FlashPNF2/CNRSinToulouse.Forallthesinteringexperiments thepowderswerepouredintothegraphitediewithoutfurther pressing,thusthegreendensityisclosetothetapdensityofthe powders.Thegreencompactwasisolatedfromthediewalland thepunchesusinggraphitefoils(Grafoil).

The SPS experiments were conducted at different tem-peratures (between 1100◦C and 1400◦C) and pressures (2–100MPa) using the AR and the HT powders. The vari-oussintering conditionsandthe resultantfinaldensities were summarized inTable 1. The startingtemperature for all SPS experimentswas600◦C;whenthistemperaturewasstabilized

(∼3minafterturningontheSPScurrent–voltage) thedesired uniaxialpressurewasapplied.Thetemperaturewasraisedunder maximalloadataconstantheatingrateof100◦Cmin−1tothe

finalSPStemperature.TheprocesswasstoppedatthefinalSPS temperature byreleasingthe pressureandcoolingthesystem (byturningoffthecurrent–voltage),withoutisothermalholding timeatthefinalSPStemperature.Pulsedurationof3.3msanda vacuumlevelof2–3Pawereused.TheSPSparameterssuchas voltage, current,temperature,pressure,ramdisplacementand ramdisplacementratewererecordedduringtheprocess.

Inordertoconfirmordismisssignificantdiffusionprocesses atthestartingtemperatureof600◦Cthreegreennc-YAG spec-imens were prepared by cold isostatic pressing (CIP) under 210MPa pressure,followed by heat treatments for 1h inair at500◦C,600◦C,and700◦C.

The finaldensities were measured byweighing andusing theArchimedesmethodwithdistilledwatermedium.Thelinear shrinkageandtemporaryrelativedensityofthecompactswere calculatedusingthedimensionanddensitiesofthespecimens aftertheSPSprocessandaccordingtotheram displacement. Theeffects of the graphitedieassemblyon thedisplacement wasconsideredandtreatedaccordingtotheproceduredescribed elsewhere.16

The microstructure of the powder and the specimens was characterized using high resolution scanning electron micro-scope(HRSEM,ZeissUltraPlusFEGSEMequippedwithEDS) operatedat2–4kV,andtransmissionelectronmicroscope(TEM, FEITecnaiG2 T20)operated at200kV.Specimensfor TEM werepreparedbyconventionalthinninganddimpling,followed byAr-ionmillingtoelectrontransparency.Athincarbon coat-ingwasappliedtomostofthespecimenstominimizecharging effectsinSEMandTEM.Thegrainsizewasdeterminedfrom HRSEM images, whereatleast 200 grainswere counted for eachspecimen.Thepowdersparticlesizewasmeasuredusing theTEMimages.X-raydiffraction(XRD)wasusedfor struc-ture analysis using X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku SmartLab) equippedwithmonochromatedCuKaradiation,andoperatedat 40kVand40mA;ascanningspeedof0.015◦s−1wasused. Dif-ferentialscanningcalorimeter– DSC(Labsys1600,Setaram) wasused tocharacterizethe thermalbehaviorof the powder, usingtheheatingrateof10◦Cmin−1.

3. Results

TheYAGnano-powderswerecharacterizedusingXRDand electronmicroscopy.TheXRDspectrumoftheas-received(AR) powder showed peaks of the Yttrium Aluminum Perovskite –YAlO3(YAP)phase(JCPDS-00-54-0621)(Fig.1).Asmall

peakat30.5◦correspondingeithertohexagonalY2O3

(JCPDS-00-020-1412) or anew YAGphase17 is present, probably as residueof the powder manufacturingprocessby liquidflame spray pyrolysis. However,the fraction of thisimpurity phase wasestimatedtobeless than3.5vol%.Heattreatmentof the as-receivedpowder for2h inairat1000◦Cresultedincubic

Fig.1.XRDoftheas-received(AR)andheattreated(HT)powder.Heat

treat-mentledtophasetransformationofthePerovskitephaseofyttriumaluminum

oxide(YAP)intothecubicgarnetphase(YAG).ThesmallpeaksintheAR

powderrefertotheresidualcubicYAG.

transformationwentalmosttocompletion.TheARpowderhad a particlesize 70±50nm, measured using the TEMimages (Fig.2a).Partoftheparticlesrevealedanamorphouscharacter, usingtiltingexperimentsinTEM.Somechangeswereobserved intheparticlesizeaftertheheattreatment,especiallythe small-estparticlesdisappeared.However,welldevelopedneckswere foundbetweentheindividualparticles(Fig.2b).DSCoftheAR powder(notshownhere)revealedexothermicpeaksat894◦C,

1087◦Cand1241◦C.Thefirstpeakat894◦Ccorrespondsto

thecrystallizationofcubicYAG18,19whilethesecondpeakat 1087◦CisrelatedtophasetransformationofYAPintoYAG.19,20 Thepeakat1241◦CwasalsoreportedbyheatingofpureYAG butitsoriginisunknown.21

ThedensityandtemperaturechangesduringtheSPS heat-ingoftheARpowderto1400◦Cat2and100MPapressures wereshown inFig.3a. The shrinkage profilesof these spec-imensarerepresentativefor allthespecimensfabricatedwith theARpowder,sinceallexperiencedsimilarheatingand pres-sureapplicationregimes,albeitwithdifferentfinaltemperatures. Applicationof100MPapressureledtotheimmediate shrink-age. Thisfirst shrinkage inthe still un-sintered powder most probablyoccursbyrearrangementprocessesonly,without plas-ticdeformation,duetothehighyieldstressofYAG.Thelower pressureof2MPa,whichispracticallytheholdingpressure dur-ingtheSPS,ledtoalmostnoshrinkagebycompaction.Further increaseindensitywasobservedattemperaturesaround950◦C (i.e.370s),howeverthisshrinkageceasedaround1060◦C(i.e. 480s).Thisfurthershrinkagewas hindered between1060◦C and1200◦CduetophasetransformationofYAPtoYAGphase, whichwasaccompaniedbyavolumeincreaseof∼17%that bal-ancedfurtherdensification.Duringthistransformationasmall increase inthe pressure was recorded for all specimens (red dash-dottedcurvesinFig.3a).

At1200◦C(i.e.560s)theshrinkagecontinuedagain, irre-spective of the applied pressure. The highest shrinkage rate wasnotedbetween1200◦Cand1400◦C,wherethechangein

Fig.2.BrightfieldTEMimagesofthe(a)ARand(b)HTpowder.Necking

betweenthenano-particlesintheHTpowderwasobserved.

the specimen density was almost 40% for the specimen sin-teredat100MPa,and25%forthespecimensinteredat2MPa. The maximal shrinkage rateof 7.9×10−1s−1 was measured around1380◦Candwasidenticalatbothpressures.Thisrapid shrinkagemayberelatedtotheenhanceddiffusionalprocesses atthe particlesurfaces,aswill beexplainedinthe discussion below.Density curvesversustheSPSparametersfor ARand HTpowdercompactsat100MPaupto1100◦Cwereshownin Fig.3b.It shouldbementioned that novisiblechanges were observed in the particle size and shape after heating experi-mentsat 500◦C,600◦Cand700◦Cfor 1hinair.Therefore,

Fig.3.Density,temperatureandpressureversusSPSprocesstimefor(a)heating

oftheARpowderto1400◦Cat2MPa(blackdashedcurve)and100MPa(black

solidcurve)pressure.(b)HeatingoftheAR(blacksolidcurve)andHT(black

dashedcurve)powdersto1100◦Cat100MPa.Temperatureandpressureare

shownbythebluedottedlineandthereddashed-dotlines,respectively.(For

interpretationofthereferencestocolorinthistext,thereaderisreferredtothe

webversionofthearticle.)

SPS start(which was at 600◦C),before the start of the SPS heating, can be neglected. The shrinkage recorded for both powders at the beginningof the heating was associated with thepressureapplication,henceparticlerearrangement.TheHT powderdidnotexhibitanyshrinkageduringtheheatingupto 1100◦Canduntilthepressurewasreleased(dashed-linecurve inFig.3b).

The final densities of the AR powder sintered at 2 and 100MPapressuresversusSPStemperatureareshowninFig.4a. Asexpected,thehigherpressureusedduringheatingbySPSto 1400◦C,resultedindenserspecimen,i.e.71%versus99%for 2and100MPapressure,respectively.Itwasapparentthat sig-nificantdensification startsabove1200◦C,irrespectiveof the

appliedpressure(Fig.4a).Thegreenandthefinalrelative den-sities of the compacts heated to1100◦C bySPS at different

pressures(2,32,64and100MPa),wereshowninFig.4b.The greendensityisthe densityafterpressureapplicationpriorto heating,andmeasuredat600◦C(filledcirclesinFig.4b).Both densities (greenandfinal)showed comparablelinear depend-ence with the applied pressure, which indicates that similar densification mechanisms occur between these temperatures, irrespectiveoftheappliedpressure.Thisfurtherindicatesthat theincreaseindensitybelow1100◦Cismainlyduetothe par-ticle rearrangementcaused bythe pressure increase(∼14%), ratherthanbytemperatureincrease(∼7%).

HRSEMimagesfromthefracturesurfacesofthespecimens sinteredtodifferentfinaltemperaturesallowedtheinvestigation

Fig.4.(a)FinaldensitiesoftheARpowderspecimensversusSPStemperature

at2and100MPa.(b)Green(circles)andfinal(triangles)relativedensitiesof

thespecimensheatedbySPSto1100◦Cshowlineardependencewithpressure.

Densityincreasedby14%and7%duetothepressureandtemperatureincrease,

respectively.(Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolorinthefigurelegend,

thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthearticle.)

of the microstructure evolution duringthe SPS. The sintered microstructurewashomogeneous,wheretheparticle morphol-ogy changedwiththe temperature increasefrom spherical to polyhedralgrainshape(Fig.5a–c).At1200◦Cmanyrod-like featuresbridgingoverthegapsbetweentheparticles/grainswere observed(insertsinFig.5a). Thesefeatures resembled mate-rialjetsbetweenthegrains,mostprobablyformedbythelocal spark; they were absent at 1300◦C and 1400◦C treatments. An increase inthe grainsize withSPS temperature increase wasalso observed(Table1). Thesolid frameof thepartially sinteredcompactswithwell-developedneckswasobservedin TEM(Fig.6a). Furthermore, unusual features were observed within the microstructure of the partially sintered compacts below1200◦C,inbothTEMandHRSEMimages.Thesewere

characterizedby narrowrod-shaped amorphous material jets, connectingbetweenthemuchlargeradjacentparticlesaround acavity (arrowed inFig. 6a andb, respectively). The amor-phous nature of the material jets was confirmed by tilting experimentsinTEM,wherenocontrastchangeswereobserved inthematerialjets,whilesignificantchangeswereobservedin thecrystallineparticlesconnectingthesejets.Theserodsdonot representconventionalneckssincetheyconnectbetween adja-centgrainswhicharefarapart;theycanbeclearlydistinguished fromtheconventional necks,bytheirunusual largemeniscus whichdoesnotshowanyfaceting.Thelargemeniscus geom-etryof therod-shape jetmaterial connectingbetweendistant particlescanbe thereforeassociatedwiththemodel ofliquid phasesintering.22Theserodsaremostprobablytheremnantof

Fig.5.HRSEMimagesofthefracturesurfaceofYAGspecimensdensifiedbySPSat(a)1200◦C,(b)1300◦Cand(c)1400◦C.Severalrod-likefeaturesbridging

overthegapsbetweenthegrains/particlesareshownbyinsertsin(a).

sintering.Assuchfeaturesmaypossiblybeanartifactdueto theionmillingforTEMpreparation,theirpresenceintheSEM images(Fig.6b)negatesthispossibility.Itshouldbementioned thattheserod-shapematerialjetswerealsoobservedinHRSEM specimenswithoutcarboncoating;therefore,theycannotbea residueoranartifactofthecarboncoating.EDSpointanalysisin HRSEM,takenatseverallociatthebrokenspecimensurfaces, showedpeaksforY,Al,OandC(fromthecarboncoating)where noimpuritieswerefound.

In addition,the denser specimens sintered at1250◦C and

1300◦Cexhibitedseveralpartiallydensenano-clusters,within whichalignedandwell-organizedindividualoriginalparticles werepreservedatthefracturesurfaces(i.e.Fig.6c).Suchparticle alignmentmaybetheremnantofthestronglocalelectricfield duringtheSPSprocess.Thisobservedmicrostructureevolution andtheoveralldensificationbehaviorwillbediscussedbelow, withrespecttoparticlesurfacesofteningduetoplasmaandthe intensifiedlocalelectricfield.

4. Discussion

Aswasshownabove,theinitialshrinkageanddensification ofthenc-YAGcompactsstartedduetothepressureapplication at∼600◦C,after thejumptothistemperature wasstabilized (Fig.3).Shrinkageceasedonce the applied pressurereached itsmaximumvalue,irrespectiveoftemperature.Further shrink-agewasobservedonlyat∼950◦CintheARpowder,andthe shrinkage rate increased withtemperature. At first, a similar

shrinkageleadingto∼7%increaseindensitywasobservedat allpressures(Fig.4b),whichindicatesthatsimilardensification mechanisms occurred between600◦C and1100◦C. Between 1060◦Cand1200◦Ctheshrinkageexperienceddiscontinuity, again irrespectiveof theappliedpressure.FollowingtheDSC results,theshrinkageat∼950◦Ccanberelatedto crystalliza-tion/nucleationofthecubicYAGphase.18–20Thistemperatureis

alittlehigherthanmeasuredintheDSC(895◦C);however,the

temperaturesduringtheSPSprocessaremeasuredatthegraphite die, andmaybe higherbyseveraldegrees fromthe tempera-ture insidethenon-conductive compact.Therefore,apossible scenariofor theshrinkage startmaybe asthe following:The particlespackatthebeginningoftheprocessbyrearrangement duetotheapplied pressure,andgetjammed duetofrictional forcesbetweenthem.Increaseintheappliedpressureovercomes thefrictionalforces,hencealinearincreaseinthedensity(upto 14%).ThispersistsuntilcrystallizationofthecubicYAGoccurs, whichreleasesthejambysupplyingexothermicenergytothe particlesurfaces,andenablesfurthershrinkageofthespecimen underthepressure.

The discontinuity in the shrinkage between 1060◦C and 1200◦C should be related tothe Perovskite toGarnet phase

transformation,whichisaccompaniedby17%volume expan-sion,henceopposingtheramdisplacementandleadingtothe small oscillations recorded in the pressure. When the phase transition wenttocompletionfurtherfast shrinkageoccurred, whereby the shrinkage rate increased between 1200◦C and 1400◦C.Thehighestshrinkageratewasobservedat1380◦C,

Fig.6.(a)BrightFieldTEMand(b)HRSEMimagesfromthespecimensfabricatedat1100◦Cand1200◦C,respectively,showingthematerial-jetsconnecting

adjacentparticlesoverthegapsinthepartiallysinteredcompactafterSPSat100MPa.(c)Alignednano-particlesinpartiallydenseclustersleftat1300◦Cand

100MPaSPStreatment.

similartoanotherSPSstudyofnano-YAG,wherethemaximal ratewasrecorded at1400◦C.23 However,atthistemperature,

rod-shape amorphous materialjetswere absent.The material jets manifest that liquid was formedduring the process. The highshrinkagerateabove1200◦Ccanberelatedtotheviscous sliding/rotationofthenano-particles,theircoalescenceinto sub-grainclusters,followedbyhierarchicalcoalescenceandgrowth oftheclusters.7Inthisrespect,thehighdensificationrateshould beassociatedwithparticlesurfacesofteningduetotheplasma formation atthe cavities.Analysis of thegrain growth kinet-icsinnc-YAG wasconsistentwithdiffusionthrough aliquid layer.7Moreover,theactivationenergyshowedaclosevalueto theenthalpyoffusionofYAG,whichisequivalenttothe activa-tionenergyformaintainingtheliquidandiscomparabletothe activationenergyforgraingrowththroughaliquidlayer.7The tendencyfor nano-grainscoalescence byrotation/sliding dur-ingSPSwasobservedforg-Al2O324andsphericala-Al2O325

powders, and for SPS of SrTiO3 nano-powders with cubical

morphology.26Above1350◦CsignificantgraingrowthofYAG nano-particlesstarted,thekineticsofwhichdidnotfollow nor-malgraingrowthbehavior.7ThiswasconsistentwithotherSPS studiesonnano-YAGatthecorrespondingtemperaturerange.27 Thefactthatthemaximumshrinkageratewasat1380◦C,where thespecimensareverydense(above90%)maybeduetotheeasy super-coolednatureofliquidYAGbelowitsmeltingpoint.28,29 Therefore,theliquidformedatthelowertemperaturehasbeen preservedmetastableyathighertemperatures.

Recently, LiF particle compacts subjected to SPS exhib-itedmicrostructurewithpartiallymeltedgrainsandsignificant materialjets,confirmingthe existenceofspark andplasma.13 Similarmicrostructuralevidenceswerereportedfor TiB2,Cu

andTi-TiB2mixture.30Apreliminarymodel,developedforthe

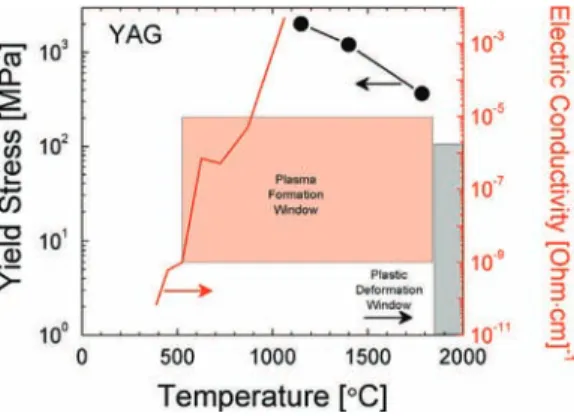

evaluationoftheplasmaconditionsindielectricceramics,14was used toestimate the temperature range for plasma formation under100MPa appliedpressure inYAG (Fig.7). When suf-ficient surface conductivity is gained, spark andplasma may format the cavitiesbetween the particlesduetosurface dis-charges,aslongas themicrostructureisnotcontinuous, thus, as long as no plastic deformation has occurred. Since YAG crystalsareveryhardtodeformplastically,theonsettemperature forplasticdeformationunder100MPaissetaround1850◦C.31

Thisleavesthetemperaturerangewindowforplasmaformation todominateatlowertemperatures as lowas 500◦C(Fig.7).

Althoughtheplasma windowboundariesweredeterminedby thecriterionof10−9–10−5−1cm−1conductivity(Fig.7and Ref.[14]),its uppertemperature boundaryis limitedonlyby thelowertemperatureoftheplasticdeformationwindow. Con-sequently, plasma may be active also at temperatures above 900◦Cinthissystemprovidedinterparticlegapsexist. There-fore, YAG is one of the oxide candidates for which plasma formationis most probable before the densification proceeds bytheplastic deformation.Thisexplainsthe existenceof the observedamorphousmaterial-jetsbetweennano-particlesinthe partially dense microstructure, formed from surface melting

Fig.7.Plasticyield–plasmawindowsdiagramcalculatedforYAGpowderat

100MPa.

aftersparkingandplasmaformation.However,thelowerextent andfrequencytofind materialjetsinYAG, suchas the ones shownin Fig.6b compared toLiF,13 may be referred tothe highmeltingtemperatureofYAG(1970◦C)anditshighmelt

viscosity32 relative toLiF, as well as its nano-size particles. In thisrespect,severaldifferentinvestigations onSPSof alu-minarevealeddense microstructureswithnotracesof liquid. However,SEMimagesfromfracturesurfacesofa-alumina, sin-teredby one-steppressurelessSPS,exhibited atomicterraces atthegrainsurfacesexposedwithinthecavities,characteristic of the evaporation–condensationmechanism.33 The electrical resistivityandtheyieldstressofAl2O3andtheirchangewith

temperature,significantly dependonthe compositionandthe polymorphcontent.FollowingthedatausedforpureAl2O3,the

SPStemperaturewindowwasestimatedtostartat900◦Catthe pressureof100MPa.14

The well-organized particle clustersfound in the partially denseregionsintheotherwisedensecompacts(Fig.6c) empha-size the strong effect of the applied electric fieldin SPS. It appearsthat the electric fieldasserts forceswhichare strong enoughtorestrict thearrangementofawholegroupof nano-particles.Yet,suchanalignmentnecessitatessufficientmobility oftheindividualnano-particles.Thisispossibleduetosurface pre-meltingandthe presence of aviscouslayer atwhichthe nano-particlescanslideandrotatetofindtheirposition,while thefrictionalstressesrelax.

Finally,the necksformed inthe heattreated(HT)powder hinder significant rearrangement and sliding of the particles comparedtotheARpowder.Furthermore,increaseinthe par-ticle connectivity is expected to decrease the probability for surfacedischargesandplasmaformationduetothepresenceofa continuousandrigidskeleton.Thisinturnprovidesacontinuous pathfortheelectriccurrenttransfer;charginganddischargeat theparticlesurfaces,whicharenecessaryforsparkandplasma, arebarelyfeasibleinsuchamicrostructure.Thelackof corre-spondinghightemperatureshrinkageinHTpowderseemstobe amanifestationofthisphenomenon.

5. Conclusions

DensificationofYAGnano-powdersbytheSPSmethodwas investigated at differenttemperature andpressure conditions.

Densification first takes place by particle rearrangement due tothepressureappliedat600◦C.Aftercompaction,shrinkage startsintheARpowderduetocrystallizationandnucleationof amorphousYAGat950◦C,thoughitstagnatesduringthephase transformationofYAPtoYAGbetween1060◦Cand1200◦C. Therapiddensificationobservedabove1200◦Cwasrelatedto thedensificationbynano-particleslidingandrotation,assisted bysurfacesofteningduetotheplasma.Materialjets connect-ingovergapsbetweenthesphericalnano-particlesareevidence forliquidformationandtheprooffortheexistenceofsparking andplasma.Theoccurrenceofplasmawasexplainedbymeans of plasmaformation–plasticdeformationdiagram.Clustersof alignednano-particlespreservedinpartiallydenseregions,in theotherwisedensespecimens,revealedtheelectricfieldeffect duringtheprocess.Theliquidformedinthepartiallydense com-pactsmaybemetastableyretainedathighertemperaturesand assisttheenhanceddensification.Themorerigidskeletonand connectedmicrostructureoftheHTpowderleavesless possi-bilitiesforsurfacecharginganddischarging,andthereforethe effectsoftheplasmadonotoccur.

Acknowledgement

R.Marderacknowledgesthesupportofthefellowshipfrom theWomeninScienceprogramoftheIsraelMinistryofScience andTechnology.

References

1.MunirZA,QuachDV,OhyanagiM.Electriccurrentactivationofsintering: areviewofthepulsedelectriccurrentsinteringprocess.JAmCeramSoc

2011;94:1–19.

2.GrassoS,SakkaY,MaizzaG.Electriccurrentactivated/assisted sinter-ing (ECAS): a review of patents 1906–2008. SciTechnol Adv Mater

2009;10:053001.

3.YoshidaH,MoritaK,KimBN,HiragaK,KodoM,SogaK,Yamamoto T.Densificationofnanocrystallineyttriabylowtemperaturesparkplasma sintering.JAmCeramSoc2008;91:1707–10.

4.ColognaM,RashkovaB,RajR.Flashsinteringofnanograinzirconiain <5sat850◦C.JAmCeramSoc2010;93:3556–9.

5.ConradH,WangJ.EquivalenceofACandDCelectricfieldonretarding graingrowthinyttria-stabilizedzirconia.ScrMater2014;72–73:33–4.

6.TamariN,TanakaT,TanakaK,KondohI,KawaharaM,TokitaM.Effectof sparkplasmasinteringondensificationandmechanicalpropertiesofsilicon carbide.JCeramSocJpn1995;103:740–2.

7.ChaimR,Marder-JeackelR,ShenJZ.TransparentYAGceramicsby sur-facesofteningofnanoparticlesinsparkplasmasintering.MaterSciEngA

2006;429:74–8.

8.WuYJ,LiJ,ChenXM,KakegawaK.Densificationandmicrostructure ofPbTiO3ceramicspreparedbysparkplasmasintering.MaterSciEngA

2010;527:5157–60.

9.NarayanJ.Graingrowthmodelforelectricfield-assistedprocessingand flashsinteringofmaterials.ScrMater2013;68:785–8.

10.TokitaM.Mechanismofsparkplasmasinteringanditsapplicationto ceram-ics.NewCeram1997;10:43–53[inJapanese].

11.KumedaK,NakamuraY,TakataA,IshizakiK.Surfaceobservationofpulsed electriccurrentsinteredaluminaballs.JCeramSocJpn1999;107:187–9.

12.SteilMC,MarinhaD,AmanY,GomesJRC,KleitzM.Fromconventional acflash-sinteringofYSZtohyper-flashanddoubleflash.JEurCeramSoc

2013;33:2093–101.

13.MarderR,EstournèsC,ChevallierG,ChaimR.Plasmainsparkplasma sinteringofceramicparticlecompacts.ScrMater2014;82:57–60.

14.ChaimR.Electricfieldeffectsduringsparkplasmasinteringofceramic nanoparticles.JMaterSci2013;48:502–10.

15.MarderR, EstournesC,Chevallier G,KalabukhovS,Chaim R.Spark plasmasinteringofductileceramicparticles:studyofLiF.JMaterSci

2014;49:5237–45.

16.MarderR,ChaimR,ChevallierG,EstournesC.Effectof1wt%LiF addi-tiveonthedensificationofnanocrystallineY2O3ceramicsbysparkplasma

sintering.JEurCeramSoc2011;31:1057–66.

17.Laine RM,MarchalJ, SunH,PanXQ. A newY3Al5O12 phase

pro-ducedbyliquid-feedflamespraypyrolysis(LF-FSP).AdvMater2005;17: 830–3.

18.LiX,LiuH,WangJ,ZhangX,CuiH.Preparation and propertiesof YAGnano-sized powderfrom differentprecipitating agent. Opt Mater

2004;25:407–12.

19.RuY,JieQ,MinL,GuoqiangL.Synthesisofyttriumaluminumgarnet (YAG)powderbyhomogeneousprecipitationcombinedwithsupercritical carbondioxideorethanolfluiddrying.JEurCeramSoc2008;28:2903–14.

20.YamaguchiO,TakeokaK,HirotaK,TakanoH,HayashidaA.Formationof alkoxy-derivedyttriumaluminiumoxides.JMaterSci1992;27:1261–4.

21.AzisRS,HollandD,SmithME,HowesA,HashimM,ZakariaA, Has-sanJ,SaidenNM,IkhwanMK.DTA/TG,XRD,and27AlMASNMRof

yttriumaluminiumgarnet,Y3Al5O12bysol–gelsynthesis.JAustCeram

Soc2013;49:74–80.

22.KangSL.Sintering-densification,graingrowthandmicrostructure.Oxford: Elsevier;2005.

23.SuárezM,FernándezA,MenéndezJL,TorrecillasR.Transparentyttrium aluminiumgarnetobtainedbysparkplasmasinteringoflyophilizedgels.J Nanomater2009;2009:1–5.

24.ShenZ,XiongY,HöcheT,SalamonD,FuZ,BelovaL.Orderedcoalescence ofnanocrystals:apathtostrongmacroporousnanoceramics. Nanotechnol-ogy2010;21:205602.

25.Morales-RodríguezA,PoyatoR,Gallardo-LópezA,Mu˜nozA, Domínguez-RodríguezA.Evidenceofnanograinclustercoalescenceinsparkplasma sintereda-Al2O3.ScrMater2013;69:529–32.

26.HuJ,ShenZ.Graingrowthbymultipleorderedcoalescenceof nanocrys-talsduringsparkplasmasinteringofSrTiO3 nanopowders.ActaMater

2012;60:6405–12.

27.PalmeroP,BonelliB,FantozziG,SpinaG,BonnefontG,MontanaroL, ChevalierJ.Surfaceandmechanicalpropertiesoftransparentpolycrystalline YAGfabricatedbySPS.MaterResBull2013;48:2589–97.

28.NordinePC,WeberJKR,AbadieJG.Propertiesofhightemperaturemelts usinglevitation.PureApplChem2000;72:2127–36.

29.TangemanJA,PhillipsBL,NordinePC,WeberJKR.Thermodynamicsand structureofsingle-andtwo-phaseyttria–aluminaglasses.JPhysChemB

2004;108:10663–71.

30.ZhangZ,LiuZF,LuJF,ShenXB,WangFC,WangYD.Thesintering mech-anisminsparkplasmasintering–proofoftheexistenceofsparkdischarge.

ScrMater2014;81:56–9.

31.ChaimR,MarderR,EstournésC,ShenZ.Densificationandpreservation ofceramicnanocrystallinecharacterbysparkplasmasintering.AdvAppl Ceram2012;111:280–5.

32.Weber RJK, Felten JJ, Cho B, Nordine PC. Glass fibres of pure and erbium-orneodymium-doped yttria–aluminacompositions.Nature

1998;393:769–71.

33.SalamonD,ShenZ.Pressure-lesssparkplasmasinteringofalumina.Mater SciEngA2008;475:105–7.