THE PRESENT STATE OF BOTANICAL KNOWLEDGE

IN CÔTE D’IVOIRE

K

OUAOJ

EANK

OFFI1*,

A

KOSSOUAF

AUSTINEK

OUASSI2,

C

ONSTANTY

VESA

DOUY

AO3,

A

DAMAB

AKAYOKO1,

I

POUJ

OSEPHI

POU2,

J

ANB

OGAERT41

University Nangui Abrogoua, UFR-SN, 02 B. P. 801 Abidjan 02, Côte d’Ivoire.

2Centre

National de Floristique (UFHB), 22 B. P. 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire.

3University Félix

Houphouët Boigny, UFR-BIOSCIENCES, 22 B. P. 1682 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire.

4

University of Liège, Biodiversity and Landscape Unit, Passage des Déportés 2, B 5030

Gembloux-Belgique. *Corresponding author: KOFFI Kouao Jean: kouaojean@yahoo.fr

Abstract.—The aim of this present study is to summarize the current state of research on the flora of theCôte d’Ivoire from the SIG IVOIRE database to better direct future collection efforts. Herbarium specimen data used for this study covered the period from 1894 to 2000, and were assembled by 226 collectors. This database comprises 15,228 samples, grouped in 3621 species, 1371 genera, and 198 families. A grid system was used to cover the Ivorian territory at spatial resolution of 0.75° x 0.75°. Indices of evenness and completeness were calculated to characterize sampling and identify floristically well-known regions. The exploration of the Ivorian territory is far from uniform, such that some areas were more densely surveyed, but others partially or not at all. The regions of Grands Ponts, Agnéby-Tiassa, Loh-Djiboua, part of Gbèkè, Boukani, San Pedro and Cavally were floristically well known; environmentally, the largest gaps in coverge were in the mountains in western Côte d'Ivoire.

Key words.—Côte d’Ivoire, flora, biodiversity, SIG IVOIRE, GIS, completeness. The forests of the tropical world are

characterized by particular community structures and specific floristic compositions. Floristic richness of tropical forest have been highlighted by numerous studies (Gentry 1988; Wright 2002). For Leigh et al. (2004), tropical forests are clearly museums of species diversity. The flora of tropical Africa has attracted the interest of many botanists, such as Auguste Chevalierie, André Aubréville, George Mangenot, and Ake Assi Laurent. These botanists, via several sum-maries (De Gouvenain and Silander 2003; Kelat-wang and Garzuglia 2005; Lehmann and Kioko 2005; Jørgensen 2006; Nair 2006; Kowero et al. 2006; Glenday 2008) have highlighted many of the details of the distribution and diversity of the African flora (Aké-Assi 2001, 2002).

In Côte d'Ivoire, many studies (Kouakou 1989; Corthay 1996; Kouamé 1998; Nusbaumer 2003; Adou Yao and N'Guessan 2005) have focused on the flora in general (Aké-Assi 2001, 2002). Work on botany in Côte d’Ivoire began early in the twentieth century, and is active continuing today, with many detailed studies. The flora of Côte d’Ivoire is rich; according to recent estimates, it includes 3677 species of vascular plants, divided between forests and savannas (Ake-Assi 1961, 1962, 1976, 1984, 1998, 2001, 2002). Several young researchers have launched botanical inventory studies in key

areas of Côte d'Ivoire as part of their theses or other research. Still, despite all these efforts, many areas are yet to be inventoried in detail and remain poorly known. These gaps underline the importance of increasing geographic knowledge of the flora of country to provide a solid base for development of future strategies for document-tation, understanding, conservation, and use of the biodiversity of the country.

It is in this perspective that, for many years, the Conservatory and Botanical Garden of Geneva (CJBG) and the National Floristic Center of the University of Abidjan, with the help of the Swiss Center for Scientific Research in Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), have conducted research on the flora and vegetation of the country (Bänninger 1995; Corthay 1996; Kouamé 1993, 1998; Dotty 1999; Bakayoko 1999; Menzies 2000). CJBG implemented a geographic information system (GIS) for Côte d'Ivoire, which includes rich botanical data, with diverse map information on the physical environments of the country. It combines a relational botanical database and a mapping environment (Gauthier et al. 1999); this system provides the base data for this study.

Biogeographic studies aim to understand how living organisms are distributed spatially, which factors influence those distributions, and how these patterns change over time (Brown and Lomolino 1998). Biodiversity databases are the

main source of information for such studies, specifically data that place particular species at georeferenced locations at specific points in time. Based on this information, spatial patterns can be investigated at scales ranging from local to global (Brown and Maurer 1989). Hence, biogeographic understanding depends heavily on the quality and completeness of information in biodiversity databases.

The present study aims to summarize the current state of knowledge of the flora of the Côte d’Ivoire as summarized in the SIG IVOIRE database. Specifically, study goals are (1) determine the frequency and distribution of botanical investigations across Côte d’Ivoire, (2) assess the intensity and completeness of these explorations, and (3) identify areas that remain poorly known in the country.

METHODS

Study data

The Republic of Côte d'Ivoire covers an area of 322,462 km2, limited to the north by Mali and

Burkina Faso, to the west by Liberia and Guinea, to the east by Ghana, and to the south by the Atlantic Ocean. The country has 22 million inhabitants, according to General Census of Population and Housing of 2014. Côte d'Ivoire covers parts of two climatic zones: equatorial and tropical (Eldin 1971), and as such has two rainy seasons and two dry seasons, although northern Côte d'Ivoire has only one rainy and one dry season.

The natural vegetation types across the country include dense humid evergreen forest, semi-deciduous rain forest, montane rainforest, and savannah (Guillaumet and Adjanohoun 1971). The terrain consists of plains, plateaus, and mountains, with Mount Nimba (1750 m) representing the high point in southwestern Côte d'Ivoire. Côte d'Ivoire is characterized by desaturated lateritic soils, ferruginous soils, eutrophic brown soils, hydromorphic soils, and pseudo-podzols. (Aubert and Segalen 1996).

Plant occurrence database

The database of herbarium specimens for Côte d'Ivoire has been developed at the Conser-vatory and Botanical Gardens of Geneva, and summarizes the Ivoirian specimen holdings of herbaria in Abidjan (CNF), Geneva (CJGB), Natural History Museum of Paris, and University of Wageningen (WUR). As each record in the database contains geographic coordinates, it is related to maps through a GIS called SIG

IVOIRE (Gautier et al. 1999). The data are managed in an Access database, and related to ecological and spatial data in raster formats using IDRISI (version 2.0) and ArcView (version 3.2). SIG IVORE thus integrates botanical information with environmental data through a geographic information system (Gautier et al. 1999), and aims marshal the best information to address conservation needs of overlooked species in the face of environmental degradation (Chatelain 2002).

Database completeness

Data were cleaned via an iterative series of inspections and explorations designed to detect and document inconsistencies. (1) We created lists of unique names in each dataset in Excel, and inspected them for repeated versions of the same taxonomic concepts: misspellings, name variants, different versions of authority infor-mation, etc. Such repeated name variants were flagged, checked via independent sources, and corrected to produce single scientific names that correctly referred to single taxa. (2) We checked for geographic coordinates that fell outside of the country, but that were referred to Côte d’Ivoire. (3) Within the country, we checked for consis-tency between textual descriptions of region and geographic coordinates. In each case, where possible, we corrected the data record; where no correction was clear, we discarded data, recording data losses at each step in the cleaning process. (4) We discarded data records for which information on year, month, or day of collection was lacking; we created a unique ‘stamp’ of time as year_month_day.

We then aggregated point-based occurrence data to 0.75° spatial resolution across Côte d’Ivoire. This spatial resolution was the product of a detailed analysis of balancing the benefits of aggregating data (i.e., larger sample sizes), versus the negative of loss of spatial resolution that can make important geographic features impercep-tible. Details of this procedure are provided in Ariño et al. (in prep.).

We produced shapefiles representing the 0.75° grid system in the vector grid module of QGIS, version 2.4. We added grid system identification codes to each individual occurrence datum, and aggregated each datum to the coarse-resolution aggregation squares. In Excel, we explored relationships between data on species identity, time, and aggregation square. We calculated total numbers of records available from each grid square (termed N); we reprojected

the aggregation grid to an Africa Albers Equal-area Conic Projection, measured the Equal-area of each grid square (taking into account the area of grid squares that overlapped the edge of the country), and calculated numbers of data records per unit area. Because data for plants of Côte d’Ivoire were not massively abundant, full development of completeness indices (Sousa-Baena et al. 2013) proved rather fruitless: very few aggrega-tion aquares could be termed well-known; as a consequence, we used a more crude criterion of a density of 15.2 occurrence data points/1000 km2 to establish which squares should be considered well-known.

Once we had established these criteria in QGIS, we linked the table of grid square statistics to the aggregation grid, and saved this file as a shapefile. We created a shapefile of well-sampled aggregation squares, which we in turn converted to raster (geotiff) format using custom scripts in R version 3.1.2 (Venables and Smith 2014). This raster coverage was the basis for our identifi-cation of coverage gaps, as follows.

We used the proximity (Raster Distance) function in QGIS to summarize geographic distances across the country to any well-sampled aggregation square. To create a parallel view of environmental difference from environments represented in well-sampled areas, we plotted 5000 random points across Côte d’Ivoire, and used the Point Sampling Tool in QGIS to extract values of each point to the geographic distance raster, and to raster coverages (2.5’ spatial resolution) summarizing annual mean tempera-ture and annual precipitation drawn from the WorldClim climate data archive (Hijmans et al. 2005).

We exported the attributes table associated with the random points, and analyzed further in Excel, as follows. We first standardized the values of each environmental variable to the overall range of the variable as : (xi – xmin) / (xmax - xmin), where xi is the particular observed value in question. We then created a matrix of Euclidean distances in the two-dimensional climate space, calculating distances for each of the points with a geographic distance >0 to all of the points with geographic distance of zero; the latter represent points falling in well-sampled regions, whereas the former are scattered across the entire country; points in well-sampled regions were assigned (by definition) environmental distances of zero. Finally, the environmental distances were imported back into QGIS, and linked to the random points shapefile.

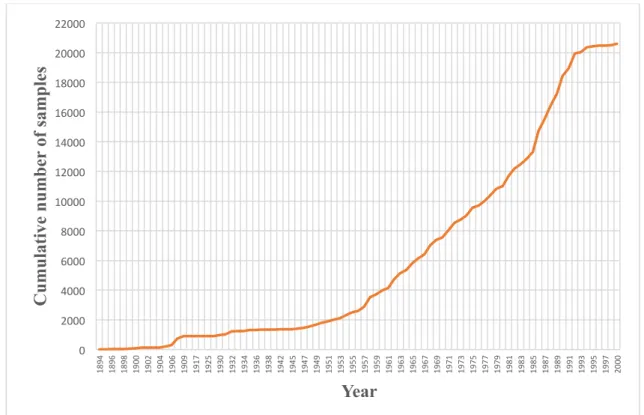

Then, a series of analyses was developed to explore patterns further. First, the whole country was considered; then it was partitioned into four cells, and then 16 cells (Table 1). At each resolution, samples were counted within the cells. All of this information was submitted to the EstimateS software version 9.1.0. (Colwell, 2013) to calculate a series of indices.

Table 1. Sizes and number of cells covering Côte d’Ivoire at different spatial resolutions.

Scales Cell area (km2) Number of cells with ≤1 record

C1 322,462 1

C4 80,615.5 4

C16 20,153.875 16

Ivorian territory was divided into 64 finer resolution (0.75°) cells. We counted numbers of data points in each cell using the “count points in polygon” function in QGIS. We used the index of evenness or regularity to describe the distribution of numbers of individuals between different cells (Wala et al. 2005). This index of evenness (Pielou 1975) is:

! = − !!Log(!!

!

!!! )

Log(!)

where pi is the proportional frequency of cell of each number and n is the number of subdivisions. The index ranges from 0 to 1, tending to 0 when one value dominates, and to 1 when values are, evenly distributed.

A quadrat method was used to characterize the spatial pattern with the index of dispersion !! = ! ! !! − ! 2

!!! /!, with ! = ! !! /!,

where ni is the proportional frequency of cells of each number and n is the number of subdivisions,

m is the number of cells contained entirely within

the territory and ! the mean. The test is two tailed: large values of !! indicate aggregation or

heterogeneity, whereas small values of !!

indicate regularity.

RESULTS

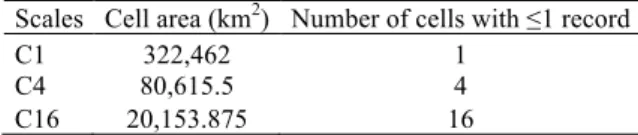

This study is based on herbarium data that cover the period 1894-2000, including work by 226 collectors. Oldest specimens were collected by Pobégui and Jolly, and the most recent were from 2000 (Jongkind, Hawthorne, Assi Jean, Aman Kadjo and others). In general, we observed three major periods (Figure 1). During 1894-1905, data accumulation was slow; it took off during 1906-1994, when it reached a plateau that lasted to the end of the database period in 2000.

!

Figure 1. Frequency of botanical investigations in Côte d’Ivoire over more than a century

shown as the cumulative number of specimens in the SIG IVOIRE database.

! ! ! !

!

Figure 2. Frequency of collection of the plants of Côte d’Ivoire by month of collection as

represented in the SIG IVOIRE database.

0! 2000! 4000! 6000! 8000! 10000! 12000! 14000! 16000! 18000! 20000! 22000! 1894! 1896! 1898! 1900! 1902! 1904! 1906! 1909! 1917! 1925! 1930! 1932! 1934! 1936! 1938! 1942! 1945! 1947! 1949! 1951! 1953! 1955! 1957! 1959! 1961! 1963! 1965! 1967! 1969! 1971! 1973! 1975! 1977! 1979! 1981! 1983! 1985! 1987! 1989! 1991! 1993! 1995! 1997! 2000!

C

u

mu

lati

ve

n

u

mb

er

of s

amp

le

s

Year

0! 1000! 2000! 3000! 1! 2! 3! 4! 5! 6! 7! 8! 9! 10! 11! 12!N

u

mb

er

of s

amp

le

s

Month of the year

Months when collection was most intense were October and November (Figure 2).

The database for this study comprised 15.2 records of 3621 species in 1371 genera and 198 families. Ten species were represented by 20-35 records, 31 species by 16-20 records, 197 species by 11-15 records, 718 species 6-10 records, and 2665 species by 1-5 records. The best represented species were Andropogon gayanus Kunth (Poaceae), Culcasia scandens P.Beauv. (Araceae), Rauvolfia vomitoria Afzel (Apocynaceae) and Voacanga africana Stapf ex Scott-Elliot (Apocynaceae). The best represented genera were Cyperus L. (Cyperaceae), Ficus L. (Moraceae) and Indigofera L. (Leguminosae); the best represented families were Leguminosae with 1610 records (10.6%), Poaceae with 1531 records (10.1%), Rubiaceae with 1166 records (7.7%), Cyperaceae with 771 records (5.1%) and Apocynaceae with 710 records (4.7%).

The sampling distribution map (Figure 3) shows botanical exploration across Côte d’Ivoire. Exploration of the Ivorian territory is not uniform. Some areas were more densely surveyed, while others have seen partial surveys only or none at all. The equitability index (E) had a value of 0.73, calculated across cells, confirming the irregularity of botanical explora-tion across Côte d’Ivoire. Also, the value of the index of dispersion (X2 = 41419; X2

m-1 = 44.99)

shows considerable aggregation. !

!

!

Figure 3. Intensity of botanical exploration across Côte d’Ivoire, showing points from which data records exist in the SIG IVOIRE database and the aggregation squares that cover the country.

!

Figure 4. Summary of floristically well-known areas across Côte d'Ivoire (in gray).

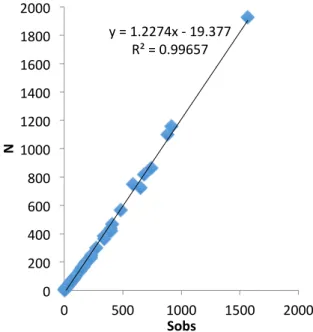

Because C values showed that few or no cells were completely inventoried, we used density of records instead. Here, the general pattern of only 10% of the cells could be called floristically well-known (Figure 4). These cells correspond to the regions of the Grands Ponts, Agnéby-Tiassa, Loh-Djiboua, Gbèkè and parts of Boukani, San Pedro, and Cavally. The best-known regions floristically were Grands Ponts and Agnéby-Tiassa. On the other hand, 90% of cells were not densely sampled. Figure 5 shows the relationship between sample size and number of species, showing that most grid squares hold only single records of a species. Figure 6 shows that ICE varies with spatial resolution, whereas the Chao index is constant regardless of spatial resolution and proves relatively invariant.

Geographically, the well-sampled regions were concentrated in the south-east. Geographic distance from these regions accumulated over space, and was highest in the Tomkpi region. Environmentally, difference from environments of well-sampled areas (Figure 7), was relatively low in the south-east and north-east, but the montane region in western Côte d'Ivoire, was quite different from well-sampled environments.

DISCUSSION

The flora of Côte d’Ivoire ranks among the best-known floras of West Africa (Aké-Assi 2001). Several studies in the country allow an idea of the degree of exploration achieved. Botanical investigations in Côte d'Ivoire began in 1882 (Aké-Assi 2001), and accumulated slowly

in the early years. Twentieth century botanical explorations reflect the beginning of penetration of Europeans into African forests (Schenel 1950).

!

!

Figure 5. Relationship between between sample size (N) and observed number of species in a grid square (Sobs).

The work of one of the explorers, Auguste Chevalier, provided the foundations of botanical knowledge of the country (Schenel 1950; Aké-Assi 2001). He worked in the country in 1906-1907 (Chevalier 1908). In 1932, Aubréville made important collections and new discoveries by visiting Tai at Tabou. In 1950, the team of Mangenot began important investigations in the south-west parts of the country, surveys that continued over succeding decades. Adjanohoun and Guillaumet realized important work on the flora and vegetation of the area (Adjanohoun and Guillaumet 1961; Guillaumet 1967; Guillaumet and Adjanohoun 1968, 1971), and in 1975, Ake Assi dreaw up a list of plants in Taï National Park (Aké-Assi and Pfeffer 1975). Except for

work by Van Rompaey (1993), botanical work in the country became less frequent after that point; a few inventories focused on forest fragmentation problems in the Taï area (Bakayoko 2005; Chatelain et al. 2010; Martin 2010).

Botanical exploration is not uniform across Ivorian territory, as some regions have been explored more than others. Regions where investigations were intense were concentrated along the coast, near activity centers, research institutions and universities, classified forests, natural parks, and reserves. Outside these areas, however, large and diverse areas of natural vegetation remain unexplored or are only partially documented. These findings are consis-tent with those of Hepper (1979) and Koffi (2008), who indicated that well-known areas are few across Africa, and that moderately and poorly known areas cover broad area. The most unique and unsampled environmental were concentrated in western Côte d'Ivoire. This area comprises one of the few true montane areas of West Africa, with Mount Nimba, which rises to an elevation of 1752 m above a panorama of undulating forested plains.

In sum, after more than a century of botanical research in Côte d'Ivoire, much effort is still needed. Certainly, the work of several prominent researchers has produced a view of the basic dimensions and characteristics of the flora and vegetation of Côte d’Ivoire. However, many regions of Côte d'Ivoire are not known floristically or remain only partially documented. This study provides detailed analyses and mapping efforts that should guide new botanical investigations in Côte d'Ivoire. This study also underlines the importance of continued systema-tic study of plant diversity as a priority in the botanical gardens, universities, and other research organizations.

Figure 6. Summary of diverse inventory statistics and their relationship to spatial resolution of the aggregation grid used across Côte d’Ivoire. y!=!1.2274x!0!19.377! R²!=!0.99657! 0! 200! 400! 600! 800! 1000! 1200! 1400! 1600! 1800! 2000! 0! 500! 1000! 1500! 2000! N" Sobs" 0! 5000! 10000! 15000! 20000! Individuals! S!(est)!analyAcal!S!mean!(runs)! ACE!mean!ICE!mean! Chao!1!mean! Chao!2!mean! Jack!1!mean! Jack!2!mean! Bootstrap!mean!Simpson!mean! C16! C4! C1!

!

Figure 7. Map of distances in environmental space to well-inventoried grid cells across Côte d'Ivoire.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the Swiss Center for Scientific Research in Côte d'Ivoire (CSRS) for the availability of the database for this study. Our thanks also go to the JRS Biodiversity Founda-tion for sponsoring our participaFounda-tion in Biodiver-sity Informatics Training Curriculum in Entebbe (Uganda), in January 2015.

REFERENCES

Adjanohoun, E. and J. L. Guillaumet. 1961. Etude botanique entre Bas-Sassandra et Bas-Cavally. ORSTOM, Adiopodoumé. Côte d’Ivoire.

Adou Yao, C.Y. and E. K. N'Guessan. 2005. Diversité botanique dans le sud du parc national de Taï, Côte d'Ivoire. Afrique Science, 1: 295 - 313.

Aké-Assi L. 1961. Contribution à l’étude floristique de la Côte d’Ivoire et des territoires limitrophes. Thèse unique. Paris. 205 pp.

Aké-Assi L. 1962. Contribution à l’étude floristique de la Côte d’ivoire et des territoires limitrophes. Vol

II : Les Monocotylédones et Ptéridophytes. Thèse unique. Paris. 147 pp.

Aké-Assi L. 1976. Esquisse de la flore générale de Côte d’Ivoire. Boissiera 24: 543-549.

Aké-Assi L. 1984. Flore de la Côte d’Ivoire: Étude descriptive et biogéographique avec quelques notes ethnobotaniques. Thèse de Doctorat d’État, Faculté de Sciences et Techniques, Université de Cocody, Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire), 1206 p.

Aké-Assi L. 1998. Impact de l'exploitation forestière et du développement agricole sur la conservation de la biodiversité biologique en Côte d'Ivoire. Le flamboyant, 46: 20-21.

Aké-Assi L. 2001. Flore de la Côte d’Ivoire 1, catalogue, systématique, biogéographie et écologie. Genève, Suisse: Conservatoire et Jardin Botanique de Genève (Suisse); Boisseria 57, 396 p.

Aké-Assi L. 2002. Flore de la Côte d’Ivoire 2, catalogue, systématique, biogéographie et écologie. Genève, Suisse: Conservatoire et Jardin

Botanique de Genève (Suisse); Boisseria 58, 441 p.

Aké Assi, L. and P. Pfeffer. 1975. Etude d'aménagement touristique du Parc National de Taï. Tome 2: Inventaire de la flore et de la faune. BDPA, Paris. France.

Aubert, G. and P. Segalen. 1966. Projet de classification des sols ferrallitiques. Cahiers ORSTOM-Pédologie, 4: 97-112.

Bakayoko, A. 1999. Comparaison de la composition floristique et de la structure forestière de parcelles de la forêt classée de Bossématié, dans l’est de la Côte d’Ivoire. Mémoire DEA., UFR Biosciences, Université de Cocody-Abidjan, 72 p.

Bakayoko, A. 2005. Influence de la fragmentation forestière sur la composition floristique et la structure végétale dans le Sud-Ouest de la Côte d'Ivoire. Thèse de Doctorat, Université d’Abidjan. Bänninger, V. 1995. Inventaire floristique des Dicotylédones de la Réserve de Lamto (V Baoulé) en Côte d’Ivoire central. Diplôme, Université de Genève, 110 p.

Brown, J. H. and B. A. Maurer. 1989. Mac-roecology: The division of food and space among species on continents. Science 243: 1145–1150.

Brown, J. H. and M. V. Lomolino. 1998. Biogeography. 2nd ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Massachusetts (Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers).

Chatelain, C., Kadjo, B., Koné, I. and J. Refisch. 2000. Relations faune - flore dans le Parc National de Taï: une étude bibliographique. Tropenbos Côte d’Ivoire.

Chatelain, C., Bakayoko, A., Martin, P. and L. Gautier. 2010. Monitoring tropical forest fragmentation in the Zagne-Tai area (west of Tai National Park, Cote d'Ivoire). Biodiversity and Conservation. 19: 2405–2420.

Chevalier, A. 1908. La Forêt vierge de la Côte d'Ivoire. La Géographie 17: 201-210.

Colwell, R. K. 2013. EstimateS: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 9. Persistent URL <purl.oclc.org/estimates>.

Corthay, R. 1996. Analyse floristique de la forêt sempervirente de Yapo (Côte d'Ivoire). Université de Genève.

De Gouvenain, R. C. and J. A. J. R. Silander. 2003. Do tropical storm regimes influence the structure of tropical lowland rain forests? Biotropica, 35:166 - 180.

Dotia, Y. P. 1999. Arbres, arbustes et lianes ligneuses de la commune de Kouto, nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. DEA, Université de Cocody-Abidjan.

Eldin, M. 1971. Le climat de la Côte d’Ivoire. Pp. 73-108 in Avenard J.M., Eldin E., Girard G., Sircoulon J., Touchebeuf P., Guillaumet J.L., Adjanohoun E. and A. Perraud. ed. 1971. Le milieu naturel de Côte d’Ivoire. Mémoires ORSTOM n° 50, Paris (France).

Gautier, L., Aké Assi, L., Chatelain, C. and R. Spichiger. 1999. Ivoire: a geographic information system for biodiversity managment in Ivory Coast. Pp. 183-194 in Timberlake, J. and S. Kativus. ed. African Plants: Biodiversity Taxonomy and uses. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Gentry, A. H. 1988. Tree species richness of upper Amazonian forests. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 85: 156-159.

Glenday, J. 2008. Carbon storage and carbon emission offset potential in an African riverine forest, the lower Tana River forests, Kenya. Journal of East African Natural History, 97: 207 - 223.

Guillaumet, J. L. 1967. Recherches sur la flore et la végétation du Bas-Cavally (Côte d'Ivoire). Mémoires ORSTOM n°20.

Guillaumet, J. L. and E. Adjanohoun. 1968. Carte de la végétation de la Côte d'Ivoire au 1/500.000. ORSTOM.

Guillaumet, J. L. and E. Adjanohoun. 1971. La végétation de la Cote d’Ivoire. Pp. 161-263 in Avenard J.M., Eldin E., Girard G., Sircoulon J., Touchebeuf P., Guillaumet J.L., Adjanohoun E. and A. Perraud. ed. Le milieu naturel de Côte d’Ivoire. Mémoires ORSTOM n° 50, Paris (France).

Hepper, N. F. 1979. Deuxième édition de la carte du degré d’exploration floristique de l’Afrique au sud du Sahara. Pp. 157-162 in G. Kunkel ed. Proceedings of the IXth plenary meeting of the Association pour l'Etude Taxonomique de la Flore d'Afrique Tropicale (AETFAT). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. and A. Jarvis. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 25: 1965-1978.

Jørgensen, I. 2006. Forestry in Africa: a role for donors? International Forestry Review, 8: 178 - 182.

Kelatwang, S. and M. Garzuglia. 2006. Changes in Forest Area in Africa 1990 - 2005. International Forestry Review, 8: 21 - 30.

Koffi, K. J., D. Champluvier, E. Robbrecht, M. El Bana, R. Rousseau and J. Bogaert. 2008. Acanthaceae species as potential indicators of phytogeographic territories in central Africa. In: A. Dupont & H. Jacobs (eds.) Landscape Ecology

Research Trends: 165-182. Nova Science

Publishers, ISBN 978-1-60456-672-7.

Kouakou, N. 1989. Contribution à l'étude de la régénération naturelle dans les trouées de l'exploitation en forêt de Taï (Côte d'Ivoire): approches écologiques et phytosociologiques. Faculté des Sciences et Technique. Université d’Abidjan.

Kouamé, N. F. 1993. Contribution au recensement des Monocotylédones de la Réserve de Lamto (Côte d’Ivoire Centrale) et à la connaissance de leur

place dans les différents faciès savaniens. Mémoire de DEA. Université de Cocody-Abidjan, 128 p.

Kouamé, N. F. 1998, Influence de l'exploitation forestière sur la végétation et la flore de la forêt classée du Haut Sassandra (Centre-Ouest de la Côte d'Ivoire). UFR Biosc., Univ. Cocody Abidjan.

Kowero, G., Kufakwandi, F. & Chipeta, M. 2006. Africa's capacity to manage its forests: an overview. International Forestry Review, 8: 110-117.

Lehmann, I. and E. Kioko. 2005. Lepidoptera diversity, floristic composition and structure of three Kaya forests on the south coast of Kenya. Journal of East African Natural History, 94: 121 - 163. Mangenot, G. 1956. Etude sur la forêt des plaines et

plateaux de Côte d'Ivoire. Etudes éburnéennes. IFAN, Dakar, 4: 55 - 67.

Martin, P. J. A. 2010. Influence de la fragmentation forestière sur la régénération des espèces arborées dans le Sud-Ouest de la Côte d'Ivoire. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Genève. 306 p.

Menzies, A. 2000. Structure et composition floristique de la forêt de la zone ouest du parc national de Taï (Côte d’Ivoire). Diplôme, Université de Génèse, 124 p.

Nair, C. T. S. 2006. What is the Future for African Forests and Forestry? International Forestry Review, 8: 4 - 13.

Nusbaumer, L. 2003. Structure et composition floristique de la Forêt Classée du Scio (Côte

d'Ivoire): étude descriptive et comparative. Université de Genève, Suisse. 150 p.

Pielou, E. C. 1975. Ecological diversity. New York, John Wiley & Sons. 165 p.

Mariane, S. S. B., Letıcia, C. G. and T. P. Andrew. 2013. Completeness of digital accessible knowledge of the plants of Brazil and priorities for survey and inventory. Diversity and Distributions, 20: 1-13.

Schnell, R. 1950. Etat actuel des recherches sur la végétation de l'Afrique intertropicale française. Vegetation, 1.2: 331-340.

Singh, K. D. 1993. L’évaluation des ressources forestières en 1990. Unsaylva 174 (44): 10-20. Van Rompaey, R. S. A. R. 1993. Forest gradients in

West Africa: A spatial gradient analysis. Thesis Wageningen. 142 p.

Venables, W. N. and D. M. Smith. 2014. An Introduction to R: A Programming Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics Version 3.2.2. The R Development Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, AU. U.R.L.: http://www.r-project.org/.

Wala, K., Sinsin, B., Guelly, K. A., Kokou, K. and K. Akpagana. 2005. Typologie et structure des parcs agroforestiers dans la préfecture de Doufelegou (Togo). Sécheresse, 16 (3): 209-216.

Whittaker, R. J., Araùjo, M. B., Paul, J., Ladle, R. J., Watson, J. E. M. and K. J. Willis. 2005. Conservation biogeography: assessment and prospect. Diversity and Distributions 11: 3–23.