Specific Tariff versus Ad valorem Tariff: Choice of a Policy

Instrument in Agricultural Trade Negotiations

Mémoire

Abdelaziz Tidjani Serpos

Maîtrise en économie rurale

Maître ès sciences (M.Sc.)

Québec, Canada

iii

Résumé

La conversion des tarifs spécifiques en leur équivalent ad valorem est un sujet d‟actualité en ce sens qu‟elle fait partie des priorités dans les discussions des membres de l‟Organisation Mondiale du Commerce (OMC). Peut-on mieux comprendre et anticiper les choix de tarifs par les pays dans un contexte de négociation commerciale? Le présent mémoire se propose d‟apporter une réponse à cette question. Nous avons utilisé un modèle à deux étapes. La première consiste au choix du type de tarif par les pays. La deuxième, quant à elle, est la phase de négociation. Le modèle est composé de deux pays et deux biens, des fonctions d‟utilité Cobb Douglas et des dotations comme fonctions de production (tel que développé par Kennan and Riezman (1988)). La détermination des équilibres de négociation a été possible grâce au produit de Nash (Nash, 1950). Nous avons trouvé que le petit pays a tendance à utiliser un tarif ad valorem et que le grand pays est indifférent entre un tarif spécifique et un tarif ad valorem lorsque celui-ci négocie avec un petit pays. Lorsque les deux pays sont de même taille, l‟équilibre de négociation est le libre-échange. L‟apport à la recherche scientifique dans le domaine est d‟une importance à préciser. Cette étude est la première à investiguer le choix des instruments de politique commerciale par un pays dans un contexte de négociation. En effet, jusque-là, très peu de travaux scientifiques se sont intéressés aux questions de modélisation des négociations commerciales. Le présent mémoire est donc une esquisse de compréhension des équilibres de négociation via une modélisation mathématique s‟inspirant de travaux précédents sur la guerre des tarifs.

v

Abstract

The conversion of specific tariff into its ad valorem equivalent is one of the key issues for current World Trade Organization (WTO) discussions. An important question this thesis addresses is whether we are able to anticipate and understand the choice between specific and ad valorem tariffs by a country in trade negotiations. We use a two-stage model to find the solutions for trade negotiations between two countries. In the first stage, countries choose between specific and ad

valorem tariffs. In the second stage, they negotiate over tariff rates. The model includes two

countries and two goods, Cobb Douglas utility functions and endowments as production functions as in Kennan and Riezman (1988). To find the negotiation solutions, we use the Nash bargaining solution (Nash, 1950). This thesis is the first to investigate the choice of policy instrument in trade negotiations. We find that a large country is indifferent between specific and ad valorem tariffs when negotiating with a small country. We also find that a small country prefers ad valorem tariff. Finally, when two countries are equal in size, the negotiation equilibrium is free trade.

vii

Table of Contents

Résumé ... iii

Abstract ... v

Table of Contents ... vii

Avant-Propos ... ix

List of Tables ... xi

List of Figures ... xiii

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 5

2.1. Previous studies on the equivalence between specific tariff and ad valorem

tariff ... 5

2.2. Optimal tariff argument and terms of trade manipulations... 6

2.3. Cooperative trade policy ... 8

2.4. Trade policy and non-economic determinants: a political-economy criterion 10

3. THEORETICAL MODEL ... 13

3.1. Ad valorem tariff game ... 14

3.2. Specific tariff game ... 19

3.3. Specific tariff vs. ad valorem tariff game ... 22

3.4. Ad valorem tariff vs. specific tariff game ... 26

4. GOVERNMENT CHOICE OF POLICY INSTRUMENT ... 31

4.1. Country A is large and has a comparative advantage in the production of good

1 ... 31

4.2. Country A and country B are equal size and country A has a comparative

advantage in the production of good 1 ... 33

4.3. Country A is strictly larger and has a comparative advantage in the

production of good 1 ... 34

4.4. Country A is strictly larger but does not have a comparative advantage in the

production of good 1 ... 36

5. DISCUSSION ... 39

6. CASE STUDY AND EVIDENCE: URUGUAY ROUND AND NORTH AMERICAN

FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (NAFTA) ... 41

7. CONCLUSION ... 45

References ... 47

ix

Avant-Propos

Je voudrais en premier lieu dédier le présent mémoire à ma feue mère Siaratou Essou Abogounrin à qui je dois tout ce que j‟ai accompli jusqu‟à présent. De plus, je dédie ce travail à mon père Ismail Tidjani Serpos, qui a donné à mes sœurs/frères et moi le goût du travail bien fait et de l‟excellence. Enfin, je dédie ce mémoire à mes frères, sœurs et à toute la famille Tidjani Serpos pour le soutien et les encouragements qu‟ils n‟ont cessé de me porter. Merci de croire en moi.

Ce mémoire n‟aurait pas vu le jour sans le financement de ma formation en Maîtrise d‟Agroéconomie à l‟Université Laval par la Banque Mondiale. Je lui témoigne ici toute ma gratitude.

Qu‟il me soit permis de remercier le Professeur Bruno Larue, mon directeur de recherche. Plus qu‟un simple encadreur, il est devenu un conseiller à qui l‟on peut poser toutes sortes de questions, mêmes les plus personnelles. En lui, je reconnais de grandes qualités intellectuelles et morales. Je témoigne ici de sa disponibilité sans limite. Le Professeur Larue a manifesté un soutien inconditionnel à mes travaux dès le premier jour où il m‟a rencontré et a stimulé ma volonté de faire un doctorat en économie agricole. C‟est aussi le moment de remercier le Professeur Larue pour sa volonté de faire de ses étudiants les meilleurs en mettant la barre très haute. Avec lui, j‟ai atteint un niveau intellectuel et critique dont je suis fier. Bruno, sincèrement, merci!

Je voudrais remercier le Professeur Sébastien Pouliot, mon co-directeur de recherche pour le suivi et la rigueur dans son travail. Malgré ses diverses activités, il a toujours du temps à consacrer à mes questions. Je me rappelle encore des discussions intéressantes que nous avons eues dans son bureau lorsque j‟avais des difficultés dans ma recherche. J‟ai beaucoup apprécié sa rigueur sur certains aspects de mon travail et cela m‟a amené à développer un esprit critique de ce que je fais comme travail scientifique. Sébastien, merci pour tout!

Bruno et Sébastien, merci de votre soutien moral et intellectuel pendant les moments difficiles! Je remercie tous mes amis du Centre de Recherche en Économie Agroalimentaire CREA (actuellement Centre de Recherche de l‟Économie Agroalimentaire, des Transports et de l‟Énergie (CREATE)) avec qui j‟ai développé une grande amitié. Des remerciements particuliers aux Professeurs Abdesalem Abbassi et Lota D. Tamini. Vous avez toujours été à mon écoute pour m‟encourager.

Je remercie ma fiancée Senandé Ramata-Laye Diane Savi pour l‟amour et le soutien qu‟elle n‟a cessé de me porter, mon ami Jelili Adégboyéga Adébiyi pour son amitié et enfin Elizabeth Ford pour son aide lors du formatage final du mémoire.

xi

List of Tables

Table 1: Tariffs solutions when country A is large and has a comparative advantage in the

production of good 1 (

0.75

and

0.6

) ... 32

Table 2: Payoffs for games where country A is large and has a comparative advantage in

the production of good 1 (

0.75

and

0.6

.) ... 32

Table 3: Export, import, world price, consumption in negotiation for

0.75and

0.6.

... 33

Table 4: Tariffs solutions when country A and country B are equal size and country A has a

comparative advantage in the production of good 1 (

0.6

and

0.6

)

... ………33

Table 5: Payoffs for games where country A is large and has a comparative advantage in

the production of good 1 (

0.6

and

0.6

) ... ……….34

Table 6: Export, import, world price, consumption in negotiation for

0.6and

0.6……… ... 34

Table 7: Tariffs solutions when country A is strictly larger and has a comparative

advantage in the production of good 1 (

0.75

and

0.4

) ... 35

Table 8: Payoffs for games where country A is strictly larger and has a comparative

advantage in the production of good 1 (

0.75

and

0.4

) ... 35

Table 9: Export, import, world price, consumption in negotiation for

0.75and

0.4... 36

Table 10: Percentage share of ad valorem and non-ad valorem tariffs on agricultural

xiii

List of Figures

Figure 1: Game tree for trade negotiation ... 13

Figure 2: Reaction functions for ad valorem tariff for imports by country A and ad valorem

tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 17

Figure 3: First order conditions for bargaining solutions for ad valorem tariff for imports by

country A and ad valorem tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 18

Figure 4: Reaction functions for specific tariff for imports by country A and specific tariff

for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 21

Figure 5: First order conditions for bargaining solutions for specific tariff for imports by

country A and specific tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 22

Figure 6: Reaction functions for specific tariff for imports by country A and ad valorem

tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 25

Figure 7: Bargaining solutions for specific tariff for imports by country A and ad valorem

tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 26

Figure 8: Reaction functions for ad valorem tariff for imports by country A and specific

tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 28

Figure 9: Bargaining solutions for ad valorem tariff for imports by country A and specific

tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

... 29

Figure 10: Share (in %) of specific and mixed tariffs in the total line tariff schedule for

1

1. INTRODUCTION

Agriculture has been at the core of the negotiations during the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). A key development was the tariffication of non-tariff barriers. Tariffication is the replacement of non-non-tariff trade barriers, such as quotas, by non-tariffs. This was undertaken to make trade policy more efficient, simpler and more transparent.1 Yet tariffs can be complex and not so transparent. This is why “tariff simplification” is among the 10 key outstanding issues identified by the Chairperson of the negotiating group on Agriculture that must be resolved if the on-going Doha Round is to be completed (WTO, 2012a).

An ad valorem tariff is a tax in percentage of the value of a shipment while a specific tariff is a per unit tax (e.g. $/kg, etc). Ad valorem and specific tariffs can be used as alternative for one another or in combination. The WTO defines a compound tariff as a combination of an “ad

valorem” duty and a “specific” duty, added together or one subtracted from the other. The term

composite tariff is sometime used to mean compound. A mixed tariff is expressed as a conditional combination of an “ad valorem” duty and a “specific” duty, one applying below a limit, and the other applying above it, WTO, 2012b). For instance, Canada‟s over-quota tariff on imports of frozen chicken parts is the maximum of 249% and $3.78/kg. Thus, when the world price is above (below) $1.52/kg, the ad valorem (specific tariff) applies. The revised modalities for agriculture call for either the conversion of all specific tariffs into ad valorem equivalents or that “no less than 90 percent of bound tariffs on products in a developed country Member‟s Schedule be expressed as simple ad valorem tariffs” (WTO, 2008c). The countries with the largest proportion of specific tariffs in their tariff schedule are Russia and the United States, with respectively 12.6% and 8.2% of their 2010 final bound tariffs (WTO, 2012c).

The protective margin provided by an ad valorem tariff is sensitive to prices and

exchange rates while a specific tariff is not. For instance, consider that one unit of a product

is worth $1,000 and that a country applies a $50 per unit tax. Equivalently, the country

could impose a 5% ad valorem tariff. If the price of the product drops to $500, the per unit

revenue from the specific tariff remains the same. However, for the ad valorem tariff, the

per unit revenue drops to $25. By the same token, the ad valorem equivalent of the $50/unit

tax increases from 5% to 10% when the world price falls from $1,000 to $500.

1 There is much evidence that tariffs dominate quotas in most situations. The classic reference on the subject

2

Chowdhury (2011) argues that specific tariffs used by rich countries discriminate

against low-income countries because these countries‟ export prices tend to be lower and

their export composition is heavily skewed toward agricultural products. Most countries

use ad valorem tariffs for most of their tariff lines, but specific tariffs are still used mainly

for agricultural products. Ad valorem tariffs are more transparent than their specific

counterparts and this is why the agriculture modalities are calling for the replacement of

many or all of the specific tariffs by ad valorem tariffs. This might have significant

implications for the trade in agricultural products.

When the tariffication of non-tariff barriers was first implemented, some WTO

members proposed prohibitive tariffs that would have curbed market access below

historical levels. Tangermann (1996) refers to the process that went on as “dirty

tariffication”. However, because the outcome of the Uruguay Round could not be trade

reductions, even for greater transparency, and because import quotas and variable levies

could no longer be used to preserve market access, tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) were created.

A TRQ consists of an in-quota tariff applied to a level of imports, the quota, and an

over-quota tariff applied on imports in excess of the over-quota. According to Gibson et al. (2001),

the average over-quota tariff was 128%, and for most countries, the average over-quota

tariff is several-fold the country‟s average agricultural tariff. Thus, the replacement of

import quotas and variable levies resulted in very high tariffs. Do we have the same

consequence for the replacement of specific tariffs by ad valorem tariffs? Could the

replacement of specific tariff by ad valorem tariffs cause a digression in trade

liberalization?

The objective of the thesis is to explore countries‟ preferences for ad valorem or

specific tariff in trade negotiations. Prior contributions show that a specific tariff is

equivalent to an ad valorem tariff under perfect competition, but non-equivalence is

possible under imperfect competition. The outcome of negotiation for countries of different

sizes is the focus of this study.

Our model features two countries with identical preferences and non-identical

production endowments. The model is a two-stage game in which countries choose the type

of tariff before the level or rate of their tariffs. The choice of tariff affects countries

bargaining position as it anchors their fall-back position if negotiations fail. Then in a

3

second stage, countries negotiate over the trade liberalization. We use the Nash bargaining

solution (Nash, 1950, 1953) to find the outcomes of trade negotiations between the

two countries.

Our specific objectives are:

1)

To derive non-cooperative Nash equilibrium for ad valorem and specific tariffs and to compare equilibrium quantities consumed and traded as well as world prices under the two tariff regimes;2) To derive cooperative Nash equilibrium tariffs given the fall-back positions from non-cooperative Nash equilibrium tariffs;

3) To evaluate the importance of country size and consumer preferences on tariff equilibria; 4) To endogenize the selection of the type of tariff used by countries.

The next section reviews related literature. Much of the discussion revolves around literature on the differences between specific and ad valorem tariffs and the choice of trade policy instrument. We then present a detailed description of the theoretical model, the results, and one example that supports our results.

5

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

We begin by reviewing the literature on the equivalence and non-equivalence of specific and ad valorem tariffs. Afterward, we discuss trade policy when the objective of governments is to maximize welfare. Because the main interest of this analysis is on the outcome of negotiations, we analyze the incidence of replacing specific tariffs by ad valorem ones on the Nash bargaining solution. Finally, we discuss another explanation for trade policy choice: the political-economy criterion.

2.1. Previous studies on the equivalence between specific tariff and ad valorem tariff

Many papers have investigated differences between tariffs and quotas since the seminal paper by Bhagwati (1971), but only a few have investigated the choice between specific and ad valorem tariffs in the context of trade negotiations. Specific and ad valorem tariffs are equivalent under perfect competition when countries do not cooperate (Suits and Musgrave, 1953). However, in a model of two countries and two tradable goods, Lockwood and Wong (2000) show that in a tariff war between two countries, a switch from specific tariffs to ad valorem tariffs makes at least one country better off. The result hinges on the effect of the tariffs on the curvature of offer curves. Conversely, some studies show that when the market structure changes, the equivalence of specific and ad valorem tariffs does not hold. For Wicksell (1959), when a country‟s market structure is a monopoly, the ad valorem tariff is superior to the specific tariff welfare-wise. Larue and Lapan (2002) find that the optimal specific tariff dominates the optimal ad valorem tariff when domestic production is monopolized because the residual demand is more elastic under the specific tariff. This result holds as well when illegal trade occurs. Larue et al. (2006) show similar results. Both Wicksell (1959) and Larue and Lapan (2002) consider a monopoly, but Larue and Lapan (2002) show that the specific tariff is better than the ad valorem one with or without smuggling. Shea and Shea (2006) find the same result in a quantity conjectural variation model.2 Similarly, Jorgensen

and Schroder (2005), using a monopolistic competition model, find that import reductions from a specific tariff generate more utility for consumers in the domestic country than the ones resulting from an ad valorem tariff.

Several studies show that the ranking of specific and ad valorem tariffs is sensitive to model assumptions. Kowalczyk and Skeath (1994) compare the two types of tariffs when a utility-maximizing country imports from a foreign monopolist. They conclude that there is no general

6

ranking between the two types of tariff in this particular case because the outcome of the model depends on the shape of the demand curve. Young and Anderson (1982) find non-equivalence under risk between quota and tariff. This is due to the fact that the quota dominates only under stringent conditions on risk aversion.

Overall, when there is market power in the domestic market, the residual demand is more elastic under a specific tariff than under an ad valorem tariff. Many comparisons are anchored on different variables (imports or domestic price, profits, etc) and this has an impact on the models results.

2.2. Optimal tariff argument and terms of trade manipulations

Economists often compare policy instruments assuming that governments seek to

maximize welfare. Bagwell and Staiger (2002), in their book about the WTO, contend that

terms of trade manipulation to maximize welfare is the main driver for government

intervention in trade. Empirical evidence about welfare maximization and terms of trade

considerations can be found in Broda and al. (2008) where it is shown that tariff rates are

conditioned by foreign export supply elasticities. More recently, Bagwell and Staiger

(2011) have shown that the pattern of negotiated tariff cuts by new WTO members fit the

predictions of a “terms of trade” theoretical model.

Welfare maximization is not the only motivation for trade policy. In fact, the

"Protection-for-Sale" model of Grossman and Helpman (1994) has inspired many

contributions. In essence, it assumes that the government is motivated by social welfare as

well as by contributions from lobbies. Some studies introduce non-economic objectives and

determine which policy instrument achieves the highest level of welfare while meeting a

given non economic objective. As such, the exercise is one of constrained

welfare-maximization. In that contexts, domestic policy instruments are often more efficient than

trade policy instruments. This is the case, for example when employment is taken into

account or there is a production target. The next section dwells on literatures in which

government chooses trade policy in order to maximize welfare or revenue.

2.2.1. Welfare and revenue maximization without retaliation

Some authors refer to the non-cooperative tariff as the orthodox optimal tariff. This terminology was first introduced by Bickerdike (1906). One result regarding non cooperative tariffs is that a “large” country can increase its welfare by imposing a tariff that optimizes the trade-off

7 between terms of trade improvements and reductions in the volume of trade. This optimal tariff assumes away possible retaliations on the part of the trade partners of the policy-active country. Johnson (1953) shows that the tariff that maximizes government revenues under perfect competition is at least as large as the one that maximizes welfare. Larue and Gervais (2002) compare the orthodox optimal tariff and the one that maximizes revenue in the presence of few domestic firms and three different hypotheses regarding the control of imports. They find that the welfare-maximizing tariff can be lower or higher than the revenue-welfare-maximizing tariff and that the specific tariff that maximizes welfare is never worse than its ad valorem counterpart.

Lin and Mai (1993) use a trade model between a country with a labor union and a capitalist country without a labor union to study the short and long term optimal policies of each country when firms are imperfectly competitive and constrained by organized labor. The authors argue that the greater the expansion elasticity of labor demand with respect to output in the labor exporting country, the greater the possibility of an optimal trade intervention in the capitalist importing country. Hatta and Ogawa (2007) study optimal tariffs in the presence of a constraint on government revenues and find that the optimal tariff is lower for imported goods that are close substitutes to exported goods.

Larue, Gervais and Pouliot (2008) show that the ranking of specific and ad valorem tariffs generating the same domestic prices when domestic production is monopolized is ambiguous, but that the specific tariff is better when the variable anchoring the comparison is the volume of imports.

Itagaki (1985) analyzes optimal tariff for small and large country under uncertain of terms of trade. The result is that the optimal tariff for the small country remains zero when policy makers take into account the change of producers/consumers behavior after observing market prices.

In summary, even if specific and ad valorem tariffs are equivalent in a competitive environment, there is no general or unambiguous ranking between the two types of tariff when markets are imperfectly competitive.

2.2.2. Welfare maximizing with retaliation (Tariff war)

Johnson (1953) showed that a country can improve its welfare by imposing a tariff even if its trade partner retaliates, but he pointed out that tariff wars are more likely to make all countries worse off. Tariff wars are usually analyzed using the concept of Nash equilibrium. This is the case with the model developed by Kennan and Riezman (1988). The authors develop a model of two countries with identical Cobb Douglas preferences. Countries have different endowments of tradable goods. Kennan and Riezman (1988) find that large countries win tariff wars when the big country has larger endowments of both goods or a lot more of one good and “enough” of the other

8

to be “big enough” to win a tariff war. Similarly, Syropoulos (2002), using the ratio of factor endowments between countries for their relative size, finds with a more general model that a country prefers a Nash non-cooperative equilibrium to free trade when it is relatively large.

Other studies have compared domestic and foreign trade policies. Tanaka (1992) concludes that, with integrated markets3, a small specific (ad valorem) tariff in the domestic country has the

same effect as a small specific (ad valorem) tariff in the foreign country provided the original equilibrium is free trade. Burbidge and Myers (2004) use a tariff war model to show that high revenue collection and redistribution costs by governments might lead to low non-cooperative tariffs. The authors also observe that there is a possibility for a government with low collection cost to win a tariff war.

Opp (2010), using a 2-country Ricardian model with a continuum of goods, find that countries tend to apply higher tariff rates when specialization gains from comparative advantage are high and transportation cost is low. A sufficiently large economy prefers the Nash tariffs equilibrium to free trade, but the required threshold size is increasing in comparative advantage. Ogawa (2012) analyzes the properties of Nash equilibrium tariffs when two countries trade a large number of goods. Uniform tariffs emerge when the elasticities with respect to the price of the numeraire good are equal across all non-numeraire goods in both countries. It is also shown that if the optimal intervention on a given good by the home country is an import subsidy, that of the foreign country is an export tax and the home subsidy cannot be higher than the foreign tax.

Finally, another strand of the literature studies optimal tariffs under uncertainty. For instance, Choi and Lapan (1991) study optimal trade policies for a developing country that relies on trade policy revenues to finance the supply of a public good under international price uncertainty. They find that the optimal specific tariff dominates the optimal quota when demands for private goods are independent of the public good, but the ranking between the two instruments generally depends on risk attitude and ordinal preferences.

2.3. Cooperative trade policy

The interest of this essay is in the outcomes of tariff negotiations, more specifically the endogenous choice between specific and ad valorem tariffs and the implications of constraining the choice. Nash (1950, 1953) formally explores the outcome of negotiation under what has become the concept of Nash bargaining solution. The solution derives from a set of axioms that defines the properties that the outcome of negotiations should have. It does not model the bargaining game, but it is often used as an approximation to a formal bargaining model like the alternating offer in

9 Rubinstein (1981) and Stahl (1972). The axioms are invariance to equivalent utility representations, Pareto efficiency, symmetry and independence of irrelevant alternatives4. In our context, the Nash

bargaining solution solves:

1 2, 2 2 1 1 . A Ath N B Bth N t t Max NP U t U t U t U t (1) In this formula, in the context of trade, UA

t2 is the utility of consumers in country A written as afunction of country A‟s tariff on good 2 (imported from country B). UB

t1 is the utility of consumers in country B which is a function of country B‟s tariff on good 1 (imported from Country A). UAth(t2N)is country A‟s consumer threat point utility (th superscript for threat) which isdefined as a function of country A‟s non cooperative tariff, t2N, and

1

( )

th N

B

U t is country B‟s consumer threat point utility that is expressed as a function of country B‟s non-cooperative tariff ,

1

N

t .

The intuition behind the Nash product is that the stakeholders must reach an agreement which improves their welfare in comparison to their respective threat points. Moreover, each country wants to be as far as possible to the threat point. Consequently, the solution of the negotiation game comes from the maximization of the Nash product. For asymmetric games, a parameter representing the bargaining power (

) could be used as in Beghin (1996) and Binmore et al. (1986). The formula becomes:

1 2 1 2 2 1 1 ,.

A Ath N B Bth N t tMax NP

U t

U

t

U t

U

t

(2)

The country which has a higher negotiation power has the greatest value between

1

and

. Copeland et al. (1989) show that in a bargaining game, the player endowed with the

most bargaining power prefers a tariff to a quota regardless of the strategy of its trade

partner. Assumptions about the functional forms for the utility and production function

often affect the outcome of the Nash bargaining solution. Indeed, Butler (2004) finds that a

linear utility function is not a good choice to generate meaningful Nash bargaining solution.

The author notes that quadratic utility functions are more appropriate in the Nash

bargaining game because the quadratic form allows for more compromise. For the

production function, many functional forms perform well. A common simplification, like in

Kennan and Riezman (1988) and Epifani and Vitaloni (2003), is to replace the production

4 For an insightful discussion of the axioms and the interpretation of the Nash bargaining solution, see

10

function by endowments. This simplifies the model and makes it easier to find analytical

solutions. It is also consistent with supply being perfectly inelastic in the short run, which is

a common assumption for agricultural production.

Mayer (1981) develops a theoretical framework to analyze outcomes of tariffs

negotiations. The author compares tariff negotiation outcomes with Nash non-cooperative

outcomes or free trade. The comparison with the retaliation outcomes makes it possible to

ascertain the extent by which negotiations improve a country‟s welfare. The

non-cooperative solution is used as a fall-back position when negotiations fail. The comparison

with free trade provides an assessment of the distortions embodied in bilateral trade

agreements. The tariff resulting from a negotiation game can be negative. In fact, Mayer

(1981) shows that a small country has incentives to subsidize imports in a negotiated tariff

agreement. Syropoulos (1994) discusses a case involving a negative tariff. The intuition

behind the negative tariff is that it is a mean to make one‟s trade partner less aggressive in

the setting of its tariff. Copeland et al. (1989) consider the possibility of lump sum

transfers to enlarge the set of possible solutions to the implicit negotiation game. When one

of the tariffs is negative, the country subsidizing removes the option of retaliation by the

other country. In our case, we assume that all tariffs are weakly positive. We posit that

import subsidies would not be sustainable politically as it would prove difficult for a

government to deflect accusations of being manipulated by foreign interests to the

detriment of domestic producers.

2.4. Trade policy and non-economic determinants: a political-economy criterion

According to Baldwin (1989), two main approaches are used to incorporate political influence in the determination of trade policy: one approach focuses on political agents‟ self-interest while the other approach revolves around social concerns of voters and public officials. For the same author, trade policy should include both self and social interests. As mentioned in a previous paragraph, Grossman and Helpman (1994) posit that there are motives other than welfare maximization to rationalize trade policies. For instance, powerful lobbies invest financial resources to influence trade policy. Grossman and Helpman (1995) find that government action in the international arena reflects domestic concerns. Traditionnally, studies on trade policy have considered governments as social welfare maximizers. Since the 1990s, a growing number of trade policy studies have allowed domestic and foreign lobbies to influence the policy process. Gawande et al. (2005), McCalman (2004) and Dutt and Mitra, (2005) have estimated the weight of social

11 welfare in the objective function of governments as a way to provide empirical support for the classic Grossman and Helpman (1994) model. In general, they find that relatively high weights are on social welfare. Facchini et al. (2006) empirical analysis reveals that the government is the stakeholder who captures most rent from trade policy through tariff revenue collection. The above studies dwell into the possibility of non-exclusivity of economic determinants of trade policy. The debate in this literature is on the empirical estimate of the weight on political contributions and welfare in the governments‟ objective function. Maggi and Rodríguez-Clare (2007) also state that apart from classical terms of trade, domestic lobbies influence trade agreements. They find that, in the presence of strong domestic lobbies, trade liberalization is deeper when the capital is more mobile across sectors.

Hillman and Ursprung (1988) use political support, proxied by producer support, as the main element in the objective function to optimize. They find that tariffs divide stakeholders, but that voluntary export restrictions conciliate the stakeholders‟ interests. Chang (2005) analyzes the impact of politics on trade policy under monopolistic competition. He finds that the endogenous optimal tariff is always a tariff and the welfare-maximizing import policy is a positive import tariff. Finally, Mitra (2002) uses a bargaining model with endogenous protection and fixed costs for political organization. He finds that low bargaining import competing lobby leads to free trade. When the cost of organizing the lobby is high, the government prefers free trade.

13

3. THEORETICAL MODEL

We investigate the choice of policy instrument in trade negotiations using a trade model of two countries and two goods. Country A and country B both produce goods 1 and 2. Consumers in the two countries have the same Cobb Douglas utility functions and production of goods is modeled using endowments as in Kennan and Riezman (1988). We assume that country A has a comparative advantage in the production of good 1 and country B a comparative advantage in the production of good 2. Countries impose tariff on their imports. Thus, country A imposes tariff on the imports of good 2 and country B imposes a tariff on the imports of good 1. Endowments are different such that trade is potentially welfare increasing for both countries. This simplification allows for more manageable expressions.

To find the type of tariff that each country chooses in trade negotiations, we use a two-stage approach. First, country A and country B simultaneously choose between specific and ad valorem tariffs. Second, countries negotiate tariffs. Figure 1 shows the two stages of the game along with each country‟s payoffs. The payoffs (a, b, c, d, e f, g, h) of the game in figure 1 are the consumer indirect utility function obtained by replacing the tariffs by their Nash bargaining solution values.

Negotiation

Figure 1: Game tree for trade negotiation

We will solve the model by backward induction. First, we will calculate welfare for each branch of the game in figure 1. That is, we will find values for a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h. Then, we will find what type of tariff countries choose and find the outcome of negotiations.

A Specific Ad valorem B B Specific Specific Ad valorem Ad valorem (e, f) (g, h) (c, d) (a, b)

14

3.1. Ad valorem tariff game

This section presents the solution for the case in which both countries use an ad valorem tariff. That is, we seek final values for a and b in figure 7. Recall from expression (2) that the outcome of negotiations depends on the threat point of each country. In our case, the threat points are the welfare in each country in a tariff war. This would constitute the outcome if negotiations were to fail. Thus, we first solve for solutions for the tariff war. Then we use those solutions to find the negotiation solutions using the Nash bargaining solution.

Let us first consider the outcome of tariff war for country A. The Cobb Douglas utility function of country A is: UAD D1A 2A

, where 1

A

D is country A‟s consumption of good 1 and 2

A

D

is country A‟s consumption of good 2. The Lagrangian of the maximization of country A‟s utility under its budget constraint is:

, 1 2 1 1

1

2 2 2 2 2 2 1 11

2 2 2.

A A A A A A

ad ad

L

D D

P X

P X

P M

PD

P D

(3) In this maximization problem,P

1 andP

2 are respectively the world prices for good 1 and 2,

1 and2

are respectively country B‟s ad valorem tariff on good 1 and country A‟s ad valorem tariff ongood 2. 1

A

X and 2

A

X are respectively country A‟s production of good 1 and country A‟s

production of good 2. The budget constraint is the difference between the total revenue of country A (given by the sum of the producers total revenue in good 1, the revenue from good 2 and the government revenue (which is the tariff times the total revenue from the imports of good 2) and its expenditures) and, the total expenditure (given by the sum of country A‟s expenditures on good 1 and the expenditures on good 2).

The ratio of the first order necessary conditions for utility maximization by country A for an interior solution is:

2 1 1 2 2.

1

A AD

P

D

P

(4)To express the ratio in (4) as a function of exports and imports, we write 1

A

D and 2

A

D as a function of good 1‟s import and export. Country A‟s production of good 1 (

1

A

X ) is replaced by its endowment (

) and country A‟s production of good 2 (X2A) is1

.1

E

is country A‟s exports of good 1 andM

2, country A‟s imports in good 2. Hence, 1A D and D2A are 1 1 1 1 A A D X E

E and 2A 2A 2 (1 2 D X M

M .15 Expression (4) becomes:

2 1 1 2 21

.

1

M

P

E

P

(5)We can replace the ratio

P P

1/

2 using the budget constraint in (5) and substitute for the expressionsfor D1A and

2

A

D . Then normalizing the price of good 2 to one, the price ratio is:

2 1 1 . M P E (6)

Then using (6) in (5), letting

P

21

, yields country A‟s implicit offer curve for good 1:

2

2 1 21

1

2

.

E

M

(7)For country B, we can derive an expression for the implicit offer curve using a similar procedure. After a few calculations, we can obtain country B‟s implicit offer curve for good 2 as:

1

1 2 11

1

2

.

M

E

(8)As in Kennan and Riezman (1988), expressions (7) and (8) define a system of equations that describes trade volumes as a function of ad valorem tariffs. Thus, solving (7) and (8) yields solutions for

E

1 andM

2.

2

1 2

1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 ; 2 1 1 2 E

(9)

2 1

2

2 2 1 21

1 1

1

.

1

2

1

2

M

(10)Using (9) and (10) in the first order necessary conditions for the utility maximization for the two countries, we can solve for the quantities demanded by both countries:

2

1 2

1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 ; 2 1 1 2 A D

(11)

2

1 2

2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 ; 2 1 1 2 A D

(12)16

2

1 2

1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 ; 2 1 1 2 B D

(13)

2

1 2

2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 . 2 1 1 2 B D

(14)Using these solutions in the utility functions of country A and country B yields indirect utility functions defined in term of tariffs and endowments of goods:

2

1 2

2

1

2

2 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ; 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 A T (15)

2

1 2

2

1

2

2 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 . 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 B T (16)The solutions in (15) and (16) are the threat points that enter into the Nash product.

The next step is to find the reaction functions

2( )

1 for country A and

1( )

2 for country B. The reaction function of a country is obtained by taking the first derivative of its utility with respect to its imports‟ tariff and by solving for this tariff as a function of the foreign country‟s tariff. The first order necessary conditions are: TA

2 TB

1 0.We will not write these expressions as they are too cumbersome to be insightful.

The reactions functions cross multiple times and therefore there are several solutions for the tariff war. However, we are interested in the nonnegative solutions which are:

0.5 1 1 / 1 / 1 1 N and 2

1

/

1

/ 1

0.5 1 N . Themodel uses the same assumptions as in Kennan and Riezman (1988) and thus yields the same solutions. Proposition 1 in Wong (2009) states that equilibrium uniqueness is assured if countries have identical CES utility functions. Since the Cobb-Douglas utility function is a special case of the CES utility function, equilibrium uniqueness follows.

Figure 2 shows an example of reaction functions for the ad valorem tariff game assuming

0.75

and

0.6

. The intersection of the reaction functions is the non cooperative equilibrium described in the previous paragraph. In this example, the reaction functions are downward sloping and convex. Tariffs are strategic substitutes as an increase in one tariff is matched by a decrease in the other. One implication is that both countries would prefer to be first-mover in a sequential game than playing simultaneously. Country A chooses a tariff rate of certain percentage and country B opts for a tariff rate of another percentage. The difference is due to the negotiation power of one country on the other and the fall-back position obtained with the threat point.17 Figure 2: Reaction functions for ad valorem tariff for imports by country A and ad valorem tariff

for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

From expression (1), the Nash product for negotiation when both countries use ad valorem tariffs is: ,

A AN

B B N

.

ad ad ad ad ad adNP

T

T

T

T

(17) ad AN T and ad N B Tare respectively the indirect utility functions for country A and country B under ad

valorem tariff war obtained by substituting for

1N and2 N

in (15) and (16).

2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 ad N N N N N N AN N N N N N N T (18)

2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 ad N N N N N N N N N N N N N B T (19)The Nash bargaining solutions are given by the first order necessary conditions for the maximization of the Nash products:

, , 1 2 0. ad ad ad ad NP NP (20)

Figure 3 shows a graph of the first order necessary conditions for the bargaining game in addition to the reaction functions for the tariff war for

0.75

and

0.6

.0 .0 0 .2 0 .4 0 .6 0 .8 1 .0 0 .0 0 .2 0 .4 0 .6 0 .8 1 .0 1N

2 1

1( )

2

2

2 N

1

18

Figure 3 illustrates two equilibria at the intersections of reaction functions: 1) an unconstrained equilibrium featuring a negative tariff, and 2) a constrained equilibrium with non-negative tariffs. The unconstrained equilibrium stems from the solution of the first order conditions. This is Mayer‟s (1981) classic result that points out that a small country prefers to subsidize imports rather than adopt a free trade policy when bargaining with a large country. We will limit our analysis to non-negative tariffs as imports subsidies are seldom used except under unusual circumstances like the 2008 food crisis (Throstle, 2008). This constrained solution will be dubbed by our tariff war solution. It is a solution because the threat point bounds the Nash product, but, it is not the bargaining solution that we seek as no country imposes its welfare at the bargaining solution.

Figure 3: First order conditions for bargaining solutions for ad valorem tariff for imports by country A and ad valorem tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

The solution for the bargaining game that we will use is given by the constraint on the non negativity of tariffs. The curve for the first order conditions for the bargaining solutions both cross the vertical axis in figure 3. In this case, a successful negotiation yields an equilibrium where 1= 0 and 2 > 0. The first order conditions for2, holds with the equality, NPad ad, 2 0.We use the

second solution to complete the game tree in figure 1.

0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 0.0 0.2 0.40. 6 0 1

2 1

1 2 * 2

1 2

2 1 * 19 3.2. Specific tariff game

This section considers that country A and country B use specific tariffs such that

0.75

and

0.6.

The method to find solutions is the same as in section 3.1. First, we can write the Lagrangian for the welfare maximization in country A when countries do not collaborate:

, 1A 2A 1 2 2

1

2 2 1 1A 2 2 2 2A.

sp sp

L

D D

P

P t

t M

PD

P t P D

(21) Maximizing (21) with respect to D1A and2

A

D , the ratio of the first order conditions for utility maximization by country A for an interior solution is:

2 1 1 2 2

.

A AD

P

D

P t

(22)Expression (22) is different from (4) because country A is now using a specific tariff. We write 1

A

D

and 2

A

D as a function of good 2 imports (M2) and good 1 export (E1): 1 1

A D

E and

2A 1 2 D

M . Expression (22) becomes:

2 1 1 2 21

.

M

P

E

P t

(23)We can replace the ratio

P P

1/

2 using the budget constraint in (23) and substitute for the expressionsfor 1A

D and 2A

D . Then normalizing the price of good 2 to one, the price ratio is as follows: 2 1 1 . M P E (24)

Then using (23) in (24), normalizing

P

21

, yields country A‟s implicit offer curve for good 1.

2

2 1 21

1

2

t

t

.

E

M

(25)For country B, we can derive an expression for the implicit offer curve using a similar procedure. After a few calculations, we find that country B‟s implicit offer curve for good 2 is:

1 1 2 1 21

1

2

t

E

.

M

E

M

(26)20

2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 ( 1) 3 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 ; 2 2 t t t t t t t t t t t E t t 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 4 2 2 2 1 1 4 6 6 3 4 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 . 2 2 1 2 t t t t t t t t t t t t t M t t Using these expressions for

E

1 andM

2in the first order conditions for the utility maximization for the two countries, we can solve for the quantities demanded by both countries:

2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 1 3 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 , 2 2 A t t t t t t t t t t t D t t

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 4 2 2 2 1 1 4 6 6 3 4 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 , 2 2 1 2 A t t t t t t t t t t t t t D t t

2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 3 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 , 2 2 B t t t t t t t t t t t D t t 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 4 2 2 2 1 1 4 6 6 3 4 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 . 2 2 1 2 B t t t t t t t t t t t t t D t t Using these solutions in the utility functions of country A and country B yields indirect utility functions. As the expressions are too cumbersome, we will not write them.

The next step is to find the reaction functions

t t

2 1( )

for country A andt t

1( )

2 for country B. We proceed exactly as in section 3.1. That is, the reaction function of a country is obtained by taking the first derivative of its utility with respect to its imports‟ tariff and by solving for this tariff as a function of the foreign country‟s tariff. The first order necessary conditions are:2 1 0.

A B

T t T t

As the expressions are difficult to interpret, we will not write them. Conversely to the case of ad valorem tariff game where we were able to find analytical expressions for the non cooperative ad valorem tariffs, it is difficult to find such expressions for the non cooperative specific tariff game. The derivation of the ad valorem tariffs in Kennan and Riezman‟s working paper is highly complex, even though it rests on several simplifying assumptions.

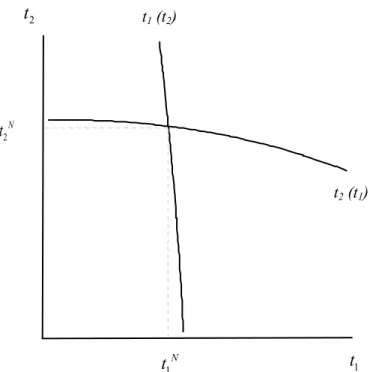

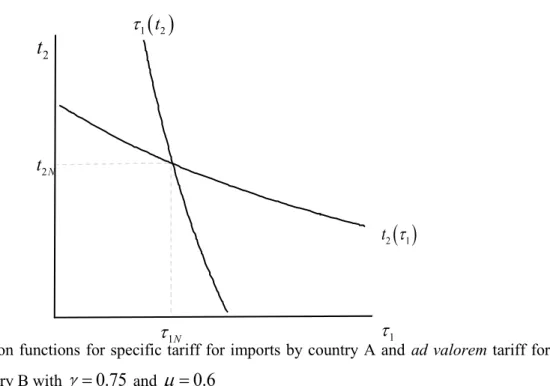

We instead rely on numerical examples. Let us show graphically the solutions for the specific tariffs. Figure 4 shows reaction functions for specific tariff war assuming

0.75

and0.6

. The reaction functions are downward-sloping and concave. As such, their curvature differs from the one associated with ad valorem tariffs. The intersection of the reaction functions is the non-cooperative equilibrium.21

t

2Figure 4: Reaction functions for specific tariff for imports by country A and specific tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

We can investigate the cooperative equilibrium. From expression (1), the Nash product for negotiation when both countries use specific tariffs is:

, sp.

A AN B BN sp sp sp sp spNP

T

T

T

T

sp ANT

and TspBN are respectively the indirect utility functions for country A and country B under specific tariff war, obtained by substituting for t1Nand t2N in TAN and TBN.Nash bargaining solutions are given by the first order necessary conditions for the maximization of the Nash products:

, , 1 2

0.

sp sp sp spNP

N

t

t

P

Figure 5 shows a graph of the first order necessary conditions for

0.75

and

0.6

. Note first that there is an equilibrium with negative tariffs, but again, we will limit ourselves to nonnegative tariffs. As in figure 2, there are two equilibria to the negotiations. The first is at the intersection of the tariff war solution and is therefore not the outcome of the negotiation that we are looking for. t1 (t2) t2 (t1) 1t

1 N t 2 N t22

Figure 5: First order conditions for bargaining solutions for specific tariff for imports by country A and specific tariff for imports by country B with

0.75

and

0.6

The second solution is given by the constraint on the non negativity of tariffs. The

curve for the first order conditions for the bargaining solutions both cross the vertical axis

in figure 5. In this case, it means that the second equilibrium is at t

1= 0 and t

2> 0. Thus, a

successful negotiation yields an equilibrium where t

1= 0 and t

2> 0.We use these solution as

the outcome of the negotiation if both countries use specific tariff as in the game tree in

figure 1.

3.3. Specific tariff vs. ad valorem tariff game

This section considers that country A uses a specific tariff and country B uses an ad valorem tariff. This will give us the solutions for e and f in figure 1. We use the same procedure as in the previous sections to find the trade negotiation outcome.

The Lagrangian for the maximization of the utility function of country A subject to its budget constraint is:

, 1 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2.

A A A A A A sp adL

D D

P X

P t X

t M

PD

P t P D

(27) This maximization problem is essentially the same as country A imposes a specific tariff on imports of good 2 from country B. 0. 2 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 0. 8 1. 0 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 0. 8 1. 0 1 t t2