O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 11178

To link to this article : doi:10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.013

URL :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.013

To cite this version : Simberloff, Daniel and Martin, Jean-Louis and

Genovesi, Piero and Maris, Virginie and Wardle, David A. and

Aronson, James and Courchamp, Franck and Galil, Bella and

García-Berthou, Emili and Pascal, Michel and Pyšek, Petr and Sousa, Ronaldo

and Tabacchi, Eric and Vilà, Montserrat Impacts of biological

invasions: what's what and the way forward. (2013) Trends in Ecology

& Evolution, vol. 28 (n° 1). pp. 58-66. ISSN 1872-8383

Any correspondance concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

Impacts

of

biological

invasions:

what’s

what

and

the

way

forward

Daniel

Simberloff

1,

Jean-Louis

Martin

2,

Piero

Genovesi

3,

Virginie

Maris

2,

David

A.

Wardle

4,

James

Aronson

2,5,

Franck

Courchamp

6,

Bella

Galil

7,

Emili

Garcı´a-Berthou

8,

Michel

Pascal

9,

Petr

Pysˇek

10,11,

Ronaldo

Sousa

12,13,

Eric

Tabacchi

14,

and

Montserrat

Vila`

15*1

DepartmentofEcologyandEvolutionaryBiology,UniversityofTennessee,Knoxville,TN37996,USA 2

CEFE-CNRSUMR5175,1919RoutedeMende,34293MontpellierCedex5,France 3

InstituteforEnvironmentalProtectionandResearchandIUCNISSG,ViaBrancati48,I-00144Rome,Italy 4

DepartmentofForestEcologyandManagement,SwedishUniversityofAgriculturalSciences,SE901-83Umea˚,Sweden 5

MissouriBotanicalGarden,4344ShawBoulevard,St.Louis,MO63110,USA 6

LaboratoireEcologie,Syste´matiqueetEvolution,UMRCNRS8079,Bat362,Universite´ParisSud,91405OrsayCedex,France 7

IOLR,POB8030,Haifa31080,Israel 8

InstituteofAquaticEcology,UniversityofGirona,E-17071Girona,Catalonia,Spain 9

INRA-UMR0985,CampusdeBeaulieu-Baˆtiment16,35000Rennes,France 10

InstituteofBotany,AcademyofSciencesoftheCzechRepublic,CZ-25243Pru˚honice,CzechRepublic 11

DepartmentofEcology,CharlesUniversityPrague,Vinicˇna´7,CZ-12844Prague,CzechRepublic 12

CMEB,CentreofMolecularandEnvironmentalBiology,DepartmentofBiology,UniversityofMinho,CampusdeGualtar, 4710-057Braga,Portugal

13

CIMAR-LA/CIIMAR–CentreofMarineandEnvironmentalResearch,LaboratoryofEcotoxicologyandEcology, RuadosBragas289,4050-123Porto,Portugal

14

Ecolab,UMR5245,CNRS-Universite´PaulSabatier,InstitutNationalPolytechnique,118,RoutedeNarbonne, 31062ToulouseCedex9,France

15

Estacio´nBiolo´gicadeDon˜ana,CentroSuperiordeInvestigacionesCientı´ficas(EBD-CSIC),C/Ame´ricoVespucios/n, IsladelaCartuja,E-41092Sevilla,Spain

Studyoftheimpactsofbiologicalinvasions,apervasive

componentofglobalchange,hasgeneratedremarkable

understandingofthemechanismsandconsequencesof

thespreadofintroducedpopulations.Thegrowingfield

ofinvasionscience,poisedatacrossroadswhere

ecolo-gy, social sciences, resource management, and public

perceptionmeet,isincreasinglyexposedtocritical

scru-tiny from several perspectives. Although the rate of

biologicalinvasions,elucidationoftheir consequences,

and knowledge about mitigation are growing rapidly,

theveryneedforinvasionscienceisdisputed.Here,we

highlight recent progress in understanding invasion

impacts and management, and discussthe challenges

that the disciplinefacesin itsscienceand interactions

withsociety.

Biological invasions:fromasset toburden

Biological invasions are a pervasive global change[1,2],

challenging the conservationof biodiversity andnatural

resources [3]. Recognition of this challenge fostered the

growth of a newfield (invasionscience [4]) dedicated to

detecting,understanding,andmitigatinginvasionimpacts

(seeGlossary).Invasionresearchhasshownthatthescope

and complexity of consequences greatly exceed earlier

perceptions. Research continues to spawn technological

improvements to deal with impacts [5,6], and invasion

science underpins national and international regulatory

frameworksprotectinghumanhealthandeconomies[7].

Poised at a crossroads where ecology, social sciences,

resourcemanagement,andeconomicsmeet,invasion

sci-encehasbeenscrutinizedfrommanyperspectives,leading

sometoquestiontheimportanceofinvasionimpactsand

need for invasion science [8]. The field has also been

challengedinitsabilitytointeractwithsociety,evenbeing

taggedas xenophobic [9]. Thesecriticisms have cultural

andhistoricalcontexts.

Publicperceptionofintroducedpopulations is

culture-andorganism-dependent[10].Polynesiansintroducedrats

forfood,butotherssawratsas ascourge onislands and

Glossary

Eradication:completeremovalofallindividualsofadistinctpopulation,not contiguouswithotherpopulations.

Extirpation:eliminationofalocalpopulation,butwithconspecificsremainingin contiguouspopulationsornearby.

Impact:anysignificantchange(increaseordecrease)ofanecologicalproperty orprocess,regardlessofperceivedvaluetohumans [16].

Introducedpopulation:populationthatarrivesatasitewithintentionalor accidentalhumanassistance [4].

Invasivepopulation:introducedpopulationthatspreadsandmaintainsitself withouthumanassistance [4].

Propagulepressure:thefrequencywithwhichaspeciesisintroducedtoasite, combinedwiththenumberofindividualsineachintroductionevent[82]. Correspondingauthor:Simberloff,D. (dsimberloff@utk.edu)

Keywords:biosecurity;communityandecosystemimpact;eradication;long-term management;societalperception.

*All authorsfully contributed tothe ideas andwritingofthe paper.Daniel SimberloffandJean-LouisMartininitiatedtheprojectandworkshopandcoordinated thewriting.

supported eradication programs. In Western societies,

fromthe greatexplorations untilthe early20thcentury,

non-nativespeciesintroducedbyacclimatizationsocieties

were considered‘exotic’ curiosities, oftenviewedas a

re-source[11].Today,somestillseemanyintroduced

popula-tionsasassets,becauseofaestheticproperties,popularity

asornamentalplantsandpets,oreconomicvalue.Certain

non-natives, such as Eucalyptus in California, are so

appreciatedthat theybecomeculturaliconsintheirnew

ranges[12].However,asbothintentionaland

unintention-al introductions increased throughout the 20th century,

biologistsgathered mountingevidenceof thethreatthat

someintroductionsposefornativespeciesandecosystems

and for human well-being. This led to the launching of

modern invasion science during the mid-1980s [13], a

developmentthatparalleledtheriseofmodern

conserva-tionbiologyandincreasingpublicconcernabout

biodiver-sity.Invasionscientists becameincreasingly predisposed

against non-natives not because they originated

else-where,butbecause theprobabilityofnegativeimpactby

non-nativesisfargreaterthanfornatives[14]andbecause

the frequency of invasions has increased exponentially

[15].This,ratherthandisplacedxenophobia,iswhyorigins

mattertoinvasionscientisits.

Here,weaimto:(i)depictthegrowingunderstandingof

invasionimpacts;(ii)showhowscientistshaveresponded

totheincreasedmanagementburdenthisunderstanding

imposes;(iii)discusschallengesposedbytheinteractionof

thefieldwithsociety;and(iv)suggestwaystoadvancethe

fieldandenhanceitsabilitytorespondtochallenges.

Arangeofimpacts:difficulttoevaluate,uncertain,

delayed,andpervasive

Difficulttoevaluate

Anecologicalimpactconsistsofanysignificantchangein

anecologicalpatternorprocess[16].Muchpopular

litera-ture and some scientific literature becloud invasion

impacts andresponsesofspecies,communities, and

eco-systemsin twoways.First isthepracticeofdesignating

native species as ‘good’ and introduced species as ‘bad.’

Speciesareneitherand,furthermore,invasionpertainsto

the populationlevel, not the specieslevel. Different

sta-keholderscanviewanintroducedpopulationas‘harmful’

or‘useful’[17].WhentheJapanesetigerprawn

Marsupe-naeusjaponicus,whichisnativetotheRed Sea,reached

the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal, fishermen

applauded, but it extirpated a native prawn (Melicertus

kerathurus), epitomizing ‘harmful’ for conservationists

[18]. Second, invasion impacts have been labeled ‘good’

or‘bad’dependingontheeffectonaparticularecosystem

service (e.g.,[19]). Animpact is‘good’ or ‘bad’ onlyfrom

certainperspectives.Schlaepferetal.[19]havepointedto

introducedpopulationsaidingconservation–forinstance,

introduced trees providing nesting habitat for birds.

However,anon-nativeplantpopulationperceivedas

ben-eficial can actually attract native birds for nesting but

ultimately decrease their survival or reproduction [20].

That nitrogen-fixing plants, disproportionately

repre-sented in non-nativefloras, enhance ecosystem nitrogen

input,soilfertility, andproductivity[21]isoftenseenas

positive, but in oligotrophic systems it is commonly

perceived as negative. Many casesof introduced

popula-tionsaidingconservationinvolvenegativeeffectsonother

species [22]. In several instances, an invader that has

replaced natives substitutes as aresource for remaining

natives.Forexample,introducedratsperformsome

polli-nationfunctionsoftheNewZealandbirdsthattheyhelped

eliminate[23].

Often, impacts usuallyseen asnegativefrom the

eco-systemperspectiveareperceivedaspositivebysome

soci-etal segments. Invasion by Pinaceae throughout the

southern hemisphere [24] usually reduces litter quality,

impairs decomposition, and depletes many soil species

[25],butthefast-growingtreessupporttimberindustries.

Manyinvasiveflammablegrassesmodifyfireregimesand

driveecosystemstoanalternativestablestate[26]butmay

benefitlivestockandsoranchers.Hence,thefullrangeof

ecological,economic,andsociologicalconsequencesshould

beconsideredwhenaninvasionimpactisevaluated.

Uncertainbutrealandoftendelayed

When a species is proposed for introduction or a recent

introduction is detected,invasion sciencesuggests cause

forconcern.InEurope,forexample,eventhoughonly11%

ofover10000non-nativepopulationsareknownsofarto

cause measurable ecological impacts [27], thisresults in

manyproblems.Amongestablishedaquaticspecies

intro-duced to six European countries, 69% have recognized

ecological impacts[28].Thesepercentagesare

underesti-mates,becausemanyimpactsaresubtleorininaccessible

habitatandsoarecharacterizedonlyafterintensivestudy.

Nativespeciescanalsosuddenlyspreadintonewhabitats,

but the risk of ecologically harmful impacts is greatly

elevated for non-natives: by a factor of 40 for plants of

theUSA,forexample[14].Furthermore,molecular

meth-ods increasingly reveal that whathad beenregarded as

‘invasion’mightinstead result from newgenotypesfrom

distant sources [29].Concern isalso heightenedbecause

many introduced populations remain innocuous for

extendedperiodsbeforespreadingandbecominginvasive

[30,31].Forinstance,Brazilianpepperremainedrestricted

inFloridaforacenturybeforerapidlyexpandingacrossa

widearea[30],whereasplantsintroducedtoEuropemight

take150–400yearstoreachtheirfullestarealextent[32].

Pervasivefrom thepopulationtothecommunityand

ecosystemlevels

Somepopulationeffectsareobvious.Introducedterrestrial

predators are often seen eating endemic island prey;

although population consequences require careful study,

we are unsurprised to learn these are dire. The same

appliestointroductionsofpredatoryfishtolakes,which

havecausedbothlocalextirpationsandglobalextinctions

ofnativefishandamphibians[33].Thegrowingrosterof

well-studiedcasesofsuchpopulationimpactsisenormous

(e.g.,[34]).

Arecentfindingisthatcertainextremelyconsequential

impacts,particularlyattheecosystemlevel,arenotreadily

detected.Anexampleisthemultipleeffectsofintroduced

nitrogen-fixersonecosystemfunctions[35].Althoughsome

impactsaffectingentirecommunitiesandecosystemshave

becomeapparentasinvasionsciencehasundergoneashift

fromaprimaryfocusonimpactsonparticularspecies(e.g.,

endemicislandbirdsdevastatedbyintroducedpredators)

tocumulativeimpactsonecosystems[21].

Increasing emphasis on community and ecosystem

impactshasrevealedimportant,sometimesunsuspected,

effectsofintroductionsfromallmajortrophicgroups.For

instance, many invasive plants transform ecosystems

both above- and belowground, particularly when they

differinfunctionaltraitsfromnativefloraandwhenthose

traitsdriveecosystemprocesses[36].Although invasive

plantsfrequentlyhavetraitsmoreassociatedwithrapid

resourceacquisitionthanthoseofnatives[37],literature

synthesesandmeta-analysesoftenfindnolargeor

consis-tent overall differences between native and introduced

plant populations in terms of functional traits [38] or

effectsonbelowgroundprocesses[39,40].Thisisbecause

invasive plant effects depend not only on the types

of invader, but also on characteristics of the invaded

ecosystem[16].

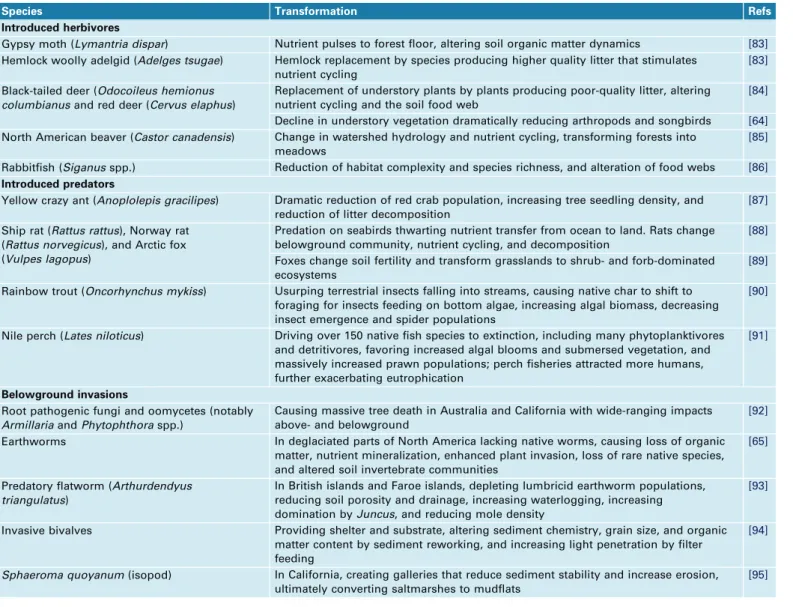

A growingnumberofstudiesshowsintroduced

consu-mers, such as herbivores, decomposers, and predators

(Table 1), transforming community composition and

ecosystempropertiesthroughtrophiccascadesand

chan-gednutrientcycling.Someinvasiveconsumersremoveor

add physical structures, altering erosion regimes and

changinghabitatsuitabilityforotherspecies[41].

Below-ground, severalinvasive consumers also radically

trans-formecosystems(Table1).

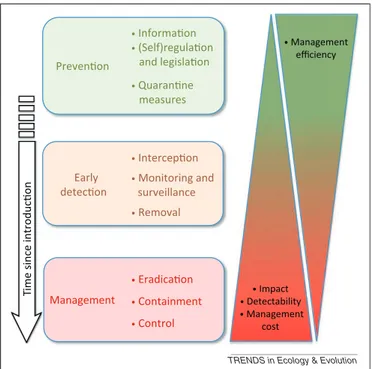

Arangeofactions:prevention,eradication,and

long-termmanagement

Fromcautiontoprevention

The litany ofnegative, far-reaching impactsof invasions

suggeststhatproposedintroductionswarrantgreatcaution.

Greatereffortsareneededtoscreenpathwaysandvectors

thatbringunintendedintroductionsandtodetectinvaders

quickly.Bythetimeimpactsarenoted,irreversiblechanges

mighthaveoccurred[42]orpalliativemeasuresmightbetoo

costly or impossible [43]. Guiding principles on invasive

speciesadoptedbytheConventiononBiologicalDiversity

(2002)reflectthesefindings:prevention isthepriority

re-sponse;earlydetection,rapidresponse,andpossible

eradi-cation should follow when prevention fails. Long-term

managementisthelastoption.Statisticsconfirmthe

validi-tyofthisapproach(Box1,Figure1).

Table1.Examplesofecosystemandcommunitytransformationsbyinvasiveconsumerpopulations

Species Transformation Refs

Introducedherbivores

Gypsymoth(Lymantriadispar) Nutrientpulsestoforestfloor,alteringsoilorganicmatterdynamics [83]

Hemlockwoollyadelgid(Adelgestsugae) Hemlockreplacementbyspeciesproducinghigherqualitylitterthatstimulates nutrientcycling

[83]

Black-taileddeer(Odocoileushemionus columbianusandreddeer(Cervuselaphus)

Replacementofunderstoryplantsbyplantsproducingpoor-qualitylitter,altering nutrientcyclingandthesoilfoodweb

[84]

Declineinunderstoryvegetationdramaticallyreducingarthropodsandsongbirds [64]

NorthAmericanbeaver(Castorcanadensis) Changeinwatershedhydrologyandnutrientcycling,transformingforestsinto meadows

[85]

Rabbitfish(Siganusspp.) Reductionofhabitatcomplexityandspeciesrichness,andalterationoffoodwebs [86]

Introducedpredators

Yellowcrazyant(Anoplolepisgracilipes) Dramaticreductionofredcrabpopulation,increasingtreeseedlingdensity,and reductionoflitterdecomposition

[87]

Shiprat(Rattusrattus),Norwayrat (Rattusnorvegicus),andArcticfox (Vulpeslagopus)

Predationonseabirdsthwartingnutrienttransferfromoceantoland.Ratschange belowgroundcommunity,nutrientcycling,anddecomposition

[88]

Foxeschangesoilfertilityandtransformgrasslandstoshrub-andforb-dominated ecosystems

[89]

Rainbowtrout(Oncorhynchusmykiss) Usurpingterrestrialinsectsfallingintostreams,causingnativechartoshiftto foragingforinsectsfeedingonbottomalgae,increasingalgalbiomass,decreasing insectemergenceandspiderpopulations

[90]

Nileperch(Latesniloticus) Drivingover150nativefishspeciestoextinction,includingmanyphytoplanktivores anddetritivores,favoringincreasedalgalbloomsandsubmersedvegetation,and massivelyincreasedprawnpopulations;perchfisheriesattractedmorehumans, furtherexacerbatingeutrophication

[91]

Belowgroundinvasions

Rootpathogenicfungiandoomycetes(notably ArmillariaandPhytophthoraspp.)

CausingmassivetreedeathinAustraliaandCaliforniawithwide-rangingimpacts above-andbelowground

[92]

Earthworms IndeglaciatedpartsofNorthAmericalackingnativeworms,causinglossoforganic matter,nutrientmineralization,enhancedplantinvasion,lossofrarenativespecies, andalteredsoilinvertebratecommunities

[65]

Predatoryflatworm(Arthurdendyus triangulatus)

InBritishislandsandFaroeislands,depletinglumbricidearthwormpopulations, reducingsoilporosityanddrainage,increasingwaterlogging,increasing dominationbyJuncus,andreducingmoledensity

[93]

Invasivebivalves Providingshelterandsubstrate,alteringsedimentchemistry,grainsize,andorganic mattercontentbysedimentreworking,andincreasinglightpenetrationbyfilter feeding

[94]

Sphaeromaquoyanum(isopod) InCalifornia,creatinggalleriesthatreducesedimentstabilityandincreaseerosion, ultimatelyconvertingsaltmarshestomudflats

Preventioncanoccur at different stages,such as

con-stricting pathways, intercepting movements at borders,

andassessingrisk forintentionalimports.Improved

bal-last water treatment exemplifies pathway constriction.

Mid-ocean ballast-water exchange for ships heading to

freshwaterports canreducefreshwaterzooplankton

con-centration in ship tanks by 99% [44]. Interception

pro-gramscanreducepropagulepressureofpotentialinvaders.

In Europe between 1995 and2004, over 80% of the 302

interceptednon-nativeinsectspecieswerenotestablished

inEurope [45].NewZealand hasinterceptedat least 27

non-nativemosquitospecies,includingimportantdisease

vectors[46].Stringentbiosecuritycanbringhugeeconomic

benefits(Box1).Forinstance,theAustralianplant

quar-antineprogramprovidessavingsbyscreeningoutputative

invaders.Evenafteraccountingforlostrevenuefromthe

few non-weeds that might be excluded, screening could

savetheAustralianeconomyUS$1.67billionover50years

[47].

Fromearlyactiontoeradication

Whatever the prevention effort, some species enter any

jurisdiction; it is important to detect them and respond

quicklyassuchactionsaredecisiveinpreventinginvasions

[48,49]. Early detection can be improved by innovative

tools, such as monitoring for environmental DNA [50].

Molecular approaches are increasingly used to monitor

invasionsinvulnerableenvironments[51].Earlydetection

allowsforcost-effectiveremoval.Forintroducedplantsin

NewZealand,earlyextirpationcostsonaverage40times

less than later attempts to extirpate widely established

populations [52]. The contrast intiming of management

betweeninvasionsoftheMediterraneanandCaliforniaby

thealgaCaulerpataxifoliaistelling(Box1).

Promptremovalisalsoecologicallylessriskythanlater

interventions. Eradicating well-established invaders can

cause surprises, such as release of another, previously

suppressed non-native [53]. Thus, substantial research

is required about the ecosystem role of a longstanding

invader beforeeradication isattempted. Thisprecaution

doesnotapplytopopulationsdetectedearly,whichwillnot

haveestablishedstrong interspecificrelationswithin the

invadedcommunity.

Eradication technologies have improved dramatically.

Ofmorethan1000attemptederadications,86%succeeded,

includingseverallong-standinginvasions[54].Avoidance

of non-target effectshas alsoimproved [53].Eradication

canbecheaperthanlong-termmanagement.Forinstance,

1yearofremovingcoypu(Myocastorcoypus)inItalywould

cost more than twice as much as the entire successful

Britisheradicationcampaign[55].Eradication

increasing-ly helpsthreatenedspecies recover. Ithas improved the

• Monitoring and surveillance • Intercepon Early detecon • Eradicaon • Quaranne measures Management • Control • Containment • Removal Prevenon • Informaon • (Self)regulaon and legislaon • Impact • Detectability • Management cost • Management efficiency T im e s in ce i n tr o d u c o n

TRENDS in Ecology & Evolution

Figure1.Managementstrategyagainstinvasivespecies.Theoptimalstrategy evolveswithtimesinceintroduction,withmanagementefficiencydecreasingand managementcostsincreasingwithtimesinceintroduction.

Box1.Costsandbenefits:lessonsfromstatistics

Reducingpropagulepressurepays:biosecurityinNewZealandand Australia

Stringentbiosecuritybasedonriskassessment,asappliedinNew Zealand and Australia, has significantly reduced the number of invasions.EuropeandNew Zealandhadsimilarinvasionratesof non-nativemammals throughthe19thcentury,butnoinvasions occurred in New Zealand after public perceptions shifted and biosecuritypolicieswereadopted(FigureI).

RapidresponseversusprocrastinationforaninvasivePacificalga In bothEuropeand California,theinvasivePacificalga, Caulerpa taxifolia, was quickly detected in small patches. In California, a US$7000000 eradication effort mounted within 6 months of discoverysucceededin2years[96].IntheMediterranean, procras-tinationforseveralyearsallowedthespeciestospreadtothousands ofhectaresoffthecoastsofSpain,France,Monaco,Italy,Croatia,and Tunisia[97],anditisnowineradicablewithcurrenttechnology. Misleadingheadcount:theHawaiianavifauna

TheHawaiianIslandshousedatleast114nativebirdspecies,almost allendemic,beforehumansarrivedapproximately1000yearsago. At least56 ofthesespecies arenow globally extinct [98].Of 53 introduced bird species from five continents that established populationsthere[99],almostallarecommonintheirnativeranges andmanyarewidelyestablished elsewhere.Although localavian speciesnumberisalmostunchanged,globalavianbiodiversityhas beensignificantlyreduced.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000

Number of non-nave mammal species

Year

Europe New Zealand

Key:

TRENDS in Ecology & Evolution

FigureI.Numbersofnon-nativemammalspeciesestablishedinEuropeand NewZealandovereightcenturies(compiledbyP.GenovesiandM.Clout).

RedListconservationstatusof11bird,fivemammal,and

oneamphibianspecies[56].However,reinvasionriskcan

remainhigh, necessitatingongoingmonitoringand

occa-sional intervention. Such costly programs might not be

deemed high priorities unless they are part of broader

programsaimedatmaintainingbiodiversityand

sustain-ableresourceuse(Box2).

From long-termmanagementtorestoration

Forcaseswhereeradicationfailsorisnotattempted,

long-term management has improved, with more ambitious

targetsthanameredecadeago.Newtechnologies

demon-stratethat long-termmanagementofinvaders isneither

futilenornecessarilydamagingtonon-targets.For

exam-ple, asyntheticlarvalpheromone attractinganadromous

adultsealampreysisreplacingbarriersandlampricidesin

parts of the GreatLakes [57]. A ‘Super Sucker’ vacuum

deviceenabledremovaloftwoinvasivealgaefrom

Hawai-iancoralreefs [58].‘BioBullets,’minutebeadscontaining

atomizedpotassiumchloridecoatedwithnon-ionic

surfac-tant, helpedremovezebramusselsfrom UKwater

facili-ties [59].

When non-nativepopulations havelongbeenpresent,

managementismorecomplicatedbecausecoststendtobe

greater, probability of success lower, and stakeholders

might favor maintaining the invader. Examples of the

complexities oftheirmanagement include shiprats that

affect seabirds of Mediterranean islands [60] and some

agricultural weeds [61]. Decisions on managing

long-standing populations must be case-specific and entail

the best information on invasion impact, likelihood of

successandrecovery,managementmethods,andpossible

non-target impacts.

Removingorreducinganinvaderoftendoesnotsuffice

tore-establishnativecommunitiesandecosystems,andso

activerestorationcanbecrucial[62].Themanyadvances

inrestorationsciencearebeyondthescopeofthispaper;

Box2providesanexampleintegratinginvasion

manage-mentwithrestoration.

Challengesposedbyhowsocietyperceivesinvasions

Anunresolvedissueformanaginginvasionsisarticulating

biodiversityconservationwithothersocialconcerns.Such

concernsdependonhowthepublicperceivesa

phenome-non, and perceptions are shaped by multiple factors of

whichscientific knowledge isonly one.Thisunderscores

the need for invasion scientists to transfer knowledge

effectively.

Perceptionofnon-nativespecies:amultifacetedprocess

Perceptions by society of introduced speciescan change.

For example, a century ago, citizens and government

agenciescollaboratedtointroducedeertotheHaidaGwaii

archipelago (British Columbia, Canada) as a source of

meat [63]. Today, government agencies consider deer a

problem, and the local community increasingly deplores

theimpactofdeeronvegetation[63,64].

Forthepublictoperceiveanimpact,avisibleeffectbya

visibleinvaderisusuallycritical.Impactsbelowgroundor

underwater are notas easilyrecognized as those

above-ground. Landscapes overwhelmed by kudzu vines are

striking,whereasdisruptionofsoilorganismsand

process-es by introduced earthworms did not attract significant

attentionuntilresearchrevealedtheycantransformNorth

Americanforests[65].Similarly,directthreatsto

endan-gered endemic or charismatic species attract attention,

whereas gradualchanges in abundanceanddistribution

of common species or ecological properties tend to pass

unnoticed.Invasionscientistsneedtoalertthepublicand

policymakerstosubtleornon-obviousimpacts.

The appearance and reputation of the invader also

matter, often independently of its impact. Plans tokill

introduced ungulates (e.g., feral domesticanimals such

as horses in the USA, camels in Australia, or deer on

islands) or charismatic species such as mute swans in

NorthAmericaorgraysquirrelsinEuropeoften

encoun-ter opposition from the public and from animal

defen-ders, whereas campaigns against invertebrates face no

such resistance.

Communicatingwithsociety:aneedforclarification

Newconcepts, sometimes producedbyscience, canalso

influencepublicperception.Forexample,thesuggestion

that local biodiversity can be maintained or even

enriched inthe faceofinvasions[66]imparts apositive

message thatcan lead to invasionsbeing seen more as

opportunitiesthanas problems.Sodoesthe proposition

that‘novelecosystems’includingnon-native speciescan

provideecosystemservicesequivalenttothoseof

native-dominated ecosystems [67]. The public does not

neces-sarilyperceivethatmaintenanceoflocalbiodiversityby

virtue of invasions is often at the expense of global

biodiversity (e.g., Box 1, Hawaiian avifauna) or that

criteria for designating an ecosystem ‘novel’ have not

Box2.Carefullyplannedrestorationimprovesinvasion management:TheZenaForestRestorationProgram

ZenaForest(WillametteValley,Oregon)exemplifiesrestorationin thePacificNorthwest,whereoakwoodlandsoccupyinteriorvalleys betweentheCoastandCascademountainranges.Oregonwhiteoak (Quercusgarryana)isfire-adaptedandgrowsinpurestandsorwith Douglasfir(Pseudotsugamenziesii),ponderosapine(Pinus ponder-osa),bigleafmaple(Acermacrophyllum),andothertreesdepending onsiteconditionsandpasttimberexploitation.Oregonwhiteoakis not shade-tolerant and, without fire, is overtopped by native Douglasfir andgrand fir (Abies grandis),as well asby various introducedplants[100].

PartofZenaForest(120ha)waspurchasedin2009byWillamette Universityfor restorationresearchandeducation.Torestore oak savanna,mostcompetingDouglasfirsareremovedorkilled(and left assnags). All non-nativecherry (Prunus spp.) are removed, along with other invaders (e.g., blackberry (Rubus sp.), scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) and English hawthorn (Crateagus laevigata)).Onegoalistoidentify‘legacy’oaksandclearcompeting trees,sothattheoaksbecomewidecrownedandhavemorewildlife valueowingtolargeracorncropsanddevelopmentofcavitiesfor smallmammalsandbirds[100].

Youngoakstandsarethinnedto100–125treesperha.Invasive brushspeciesaremechanicallyremovedortreatedwithherbicides. Heavymowingandprescribedburningreducefuelloadsandopen areas fornative grasses andwildflowers. Following reintroduced burning, seeds ofnative grasses and forbs are sown torestore native prairie. This is important because two butterfly species endangeredintheWillametteValleyneedtheseplantsforfoodand reproduction. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation make this a valuablepilotsiteforsimilarrestorationintheregion.

been provided, and quantification of services such

eco-systems providehas barelybegun [68].

Toconceptualizetheirresearchobjectsandto

commu-nicatewiththepublicandlandmanagers,invasion

scien-tists, as do other scientists [69], developed metaphors.

Theyhavebeenaccusedofrelyingonastronglynormative,

loaded vocabulary, borrowing military images [70] or

worse,usingxenophobicandracistexpressions[71].

How-ever, use of terms such as ‘invasion’ to emphasize the

spread of many phenomena considered harmful is

com-monplace(cf.metaphorsusedinpublichealthand

econom-ics).Ininvasionscience,asinothercontexts,researchers

talk about‘invasions’ because whatis observed reallyis

reminiscentofarmiesmoving.Mediareportsonbiological

invasions often attract readers’ attention with military

metaphors.However,invasionscientists,indeedall

scien-tists,shouldbewareofvalue-ladenvocabularytoavoidthe

riskofsterileideologicalarguments.

Thechargeofxenophobia,fearofstrangersbecauseof

theirorigins,isofadifferentnature.Asstated,populations

ofnon-nativespeciesarenotproblematicbecausetheyare

notnative perse, butbecause theyare morelikely than

nativestocauseecologicaldamage.Therecommendation

to prevent introductions and to beware of newly

estab-lished populations is consistent with the precautionary

principle, which has complex ethical and social

implica-tions. It comes with incentives to kill organisms solely

because ofthe ‘potential’ problemsthat they could pose.

These can be sentient beings for whichone might have

ethicalconcerns[72].Itreducespeople’sfreedomtokeep

non-native plants and animals. It also limits economic

activities that canrelease invaders (e.g., horticulture or

thepettrade).Thesecostsarethepricetobepaidtoavoid

further devastating impacts on ecosystems and human

well-being and increasing global homogenization of

eco-systems. The wish to maintain the global diversity of

nativecommunitiesandecosystemshasnothingtodowith

xenophobia. On the contrary, it stems from principles

similar to those that defend the right for every human

societytoretainitsculturaldistinctiveness,asproclaimed

bytheCouncilofEurope[73]andUNESCO[74].

Thewayforward

Fromtheobvioustothesubtleandpervasive

Asacross-disciplinaryfieldlinkingwithmanyotherfields

[6], invasion science will continue to provide important

insights into areas as diverse as conservation biology,

evolutionarybiology,populationecology,ecosystem

ecolo-gy,globalchangescience,andrestorationecology.

Howev-er, above all, invasion science will lead to improved

understandingofhowaddingasinglespeciestoa

commu-nitycangreatly modifybiodiversityandecosystem

func-tioning.

Invasionsciencemustdevelopbettermetricsfor

quan-tifyingandcategorizingimpacts[16,27]toimprove

priori-tizationofmanagementandriskassessments.Economists

require such quantified information for valuing impacts

andcoursesofactioninthecost–benefitanalysesof

indi-vidualspeciesthatareapillarofinvasioneconomics[75].

Attemptstomitigateinvasionimpactsonecosystemsand

services that they provide will have to account for the

entire range of impacts and complexity of interspecific

interactions. This will require invasion science to focus

notonlyonlossofcharismaticspeciesglobally,orchanges

in populations locally, but also on the consequences of

invasions for regional diversity. These often pertain to

the distribution and abundance of obscure community

members,tochanges introphic networksthat canaffect

ecosystem functioning,andtoconcepts such as diversity

homogenizationatthelandscapescale.Fewstudieshave

focused on these subjects despite their potential

impor-tance to biodiversity conservation. This comprehensive

approachremainsthecoreofunderstandingand

mitigat-ingtheconsequences ofbiotichomogenization[76].

Fromprinciplestoapplications:bridgingthegaps

Biosecuritypoliciesandstrategiesmustbeupdated

regu-larlytoreflectnewfindings[6].Policiesoninvasionsarein

factsolidlybasedonscience.TheConventiononBiological

Diversity(decisionVI/23)incorporatedfindingsofinvasion

sciencetodefineitsguidingprinciplesoninvaders,ranking

prevention,earlydetectionandrapidresponse,and

eradi-cation as noted above. The same principles were again

stressedbytheG8EnvironmentintheCharterofSyracuse

of2009andbyleaders ofthemostinfluential world

con-servationorganizations[77],whocalledforstrengthening,

notweakening,thestruggleagainstinvasions.

However,whereaskeyprinciplesonhowtorespondto

invasions are well advanced, their application remains

limited. Formanagement, thekey challengeis tobridge

the gap between growing scientific understanding of

impactsandmanagementaction.Thiswillrequirebetter

integrationofecologicalperspectivesandknowledgewith

socioeconomic considerations and human perceptions of

invasions.Forinstance,mostcost–benefitanalysessimply

attempttodetailcostsandbenefitsofparticularinvasions

post facto.Therefore, theydo not encompassprevention,

the preferredmanagement strategy[75];neither dothey

addresstheongoingcostsandbenefitsofdifferentpossible

policydecisionsregardinginvasionsingeneral(CourtoisP.

Mulier C., and Salles, J-M. personal communication).

Economistscannotadvanceinthisdirectionwithout

infor-mation frominvasion scientistsonthegamut ofimpacts

and possible strategies to deal with them. With such

knowledge,economistscouldtheninformthepublicabout

economicconsequencesofvariouscoursesofaction,justas

ecologistsinformthemaboutecologicalconsequences,but

it is the public and its policymakers who must define

societalobjectivesanddecidehowtoachievethem.

Fromcollidingworldviewstopracticalsolutions

Somecontroversiesaboutinvasionmanagementarerooted

indivergent ethicalframeworks.Three main worldviews

collide in a ‘triangular affair’ [78]. Ecocentrists focus on

ecological entities or processes. Theyreadily admit that

invasionsshouldbeavoidedandthat,whenitisfeasible,

invaders should be eradicated to protect biodiversity.

Anthropocentrists believe only humans deserve direct

moral consideration. Theydo not worry about ecological

impacts ofinvasions unlessthese alsodrive economic or

socialdamages.Zoocentristsaccordequalmoral

interests of individual animals for the sake of human

interests or biodiversity per seand have often opposed

eradicationplans.Thistrianglecanbe‘squared’byadding

afourthcorner,surelyunder-represented,ofbiocentrists,

whocareforeveryindividuallivingbeing,sentientornot.

Itwouldbevainforscientiststotrytosettlesuchadebate,

butanyoneengagedininvasionmanagementshouldpay

attentiontotheseunderlyingethicalissues[72].

Onewaytoproceedtowardsconsensusandsocial

agree-ment would be to acknowledge the legitimacy of these

different ethical commitments and to try to overcome

theoretical disagreements through collective search for

practicalsolutionstoproblemsrelatedtospecificinvasions

[79].Indeed,whatissharedbythethree(orfour)cornersof

the affairisakindofabsolutismregardingmoral

princi-ples.However,realpeopleinreallifeusuallycompromise

amongthesepolesdependingonthespecificsofsituations.

Moralconcernsaremoreacollectiveelaborationofnorms

fromthegroundupthanpurelydeductiveapplicationsof

theoreticalprinciples.Byhonestlyandrespectfully

engag-inginthisdebate,scientistsandmanagersmightnotonly

influencepublicperceptionsbutalsotestandimprovetheir

ownmoralpositions.

Understandinginvasionsinachangingworld

Finally,twomajorchallengesmustbeovercomerelatedto

howscientistsandthepublicperceiveintroduced

popula-tions,theirconsequences,andtheirmanagement.Firstis

theneedtoshiftattentionfurtherfromdominantfocuson

thepropertiesofinvadingorganismstohow

anthropogen-icchangesin ecosystemsfacilitatemanyinvasions(e.g.,

[62,80]butsee[81]).Suchashiftcanleadtonewwaysto

preventinvasionsortomitigateconsequencesofongoing

ones,forexamplethroughgrazingorwatermanagement

policies.Secondistheneedtoconveyinformationtothe

public about the range,scope,and consequences ofless

obvious effectsof invasions,suchas those affecting

eco-system processes. Scientists are also well positioned to

elucidate the complexities of invasions and to explore

realistic management options. Although most invasion

scientistsendorseanormativecommitmenttowards

bio-diversity,theirproperroleasscientists,intermsofpublic

discourse, is to educate citizens in a way that informs

debatewithinsocietyabouthowtothinkaboutand

man-ageinvasions.

Acknowledgments

TheworkshopthatspawnedthispaperwassponsoredbyCEFE-CNRS, the University of Montpellier (UM2) and the Re´gion Languedoc Roussillon. P.P. was supported by grant no. P504/11/1028 (Czech Science Foundation),long-term researchdevelopmentproject no.RVO 67985939 (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic), institutional resources of Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic,andacknowledgesthesupportbyPraemiumAcademiaeaward from the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. D.A.W. was supported by a Wallenberg Scholars award, E.G.B. by the Spanish Ministry of Science (projects CGL2009-12877-C02-01 and CSD2009-00065),M.V.bytheSpanishMinistryofScienceprojectsCGL2009-7515 andCSD2008-00040andtheJuntadeAndalucı´aRNM-4031,andF.C.by the French ANR (2009 PEXT 010 01). We thank three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments, Jean-Michel Salles, Pierre Courtois, and Chloe´ Mulier for discussion, and Be´renge`re Merlot for assistancewithreferences.

References

1 NationalResearchCouncil(USA)(2000)GlobalChangeEcosystems Research,NationalAcademyPress

2 MillenniumEcosystemAssessment(2005)EcosystemsandHuman Well-Being:CurrentStateandTrends:FindingsoftheConditionand TrendsWorkingGroup,IslandPress

3 TEEB (2010) The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: EcologicalandEconomicFoundations,Earthscan

4 Richardson,D.M.(2011)Invasionscience.Theroadstravelledandthe roadsahead.InFiftyYearsofInvasionEcology:TheLegacyofCharles Elton(Richardson,D.M.,ed.),pp.397–401,BlackwellPublishing 5 Asner,G.P.etal.(2008)Invasiveplantstransformthethree-dimensional

structureofrainforests.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.105,4519–4523 6 Pysˇek,P.andRichardson,D.M.(2010)Invasivespecies,environmental

changeandmanagement,andhealth.Annu.Rev.Environ.Resour.35, 25–55

7 Hulme,P.E.etal.(2008)Graspingattheroutesofbiologicalinvasions: aframeworkforintegratingpathwaysintopolicy.J.Appl.Ecol.45, 403–414

8 Davis,M.A.etal.(2011)Don’tjudgespeciesontheirorigins.Nature

474,153–154

9 Young,A.M.andLarson,B.M.H.(2011)Clarifyingdebatesininvasion biology:asurveyofinvasionbiologists.Environ.Res.111,893–898 10Coates,P.(2007)AmericanPerceptionsofImmigrantandInvasive

Species:StrangersontheLand,UniversityofCaliforniaPress 11Gruvel,A.(1936)Contributiona` l’e´tudedelabionomiege´ne´raleetde

l’exploitationdelafauneduCanaldeSuez.Me´m.Inst.d’E´ gypte29,1– 229(inFrench)

12Nun˜ez, M.A. and Simberloff, D. (2005) Invasive species and the culturalkeystoneconcept.Ecol.Soc.10,r4

13Simberloff,D.(2011)CharlesElton:neitherfoundernorsiren,but prophet.InFiftyYearsofInvasionEcology:TheLegacyofCharles Elton(Richardson,D.M.,ed.),pp.11–24,BlackwellPublishing 14Simberloff,D.etal.(2012)Thenativesarerestless,butnotoftenand

mostlywhendisturbed.Ecology93,598–607

15Hulme, P.E. et al., eds (2009) Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe (DAISIE) Handbook of Alien Species in Europe,Springer

16Pysˇek,P.etal.(2012)Aglobalassessmentofalieninvasiveplant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: the interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment.GlobalChangeBiol.18,1725–1737

17Duffy,J.E.(2009)Whybiodiversityisimportanttothefunctioningof real-worldecosystems.Front.Ecol.Environ.7,437–444

18Galil,B.S.(2007)Lossorgain?Invasivealiensandbiodiversityinthe MediterraneanSea.Mar.Pollut.Bull.55,314–322

19Schlaepfer,M.A.etal.(2011)Thepotentialconservationvalueof non-nativespecies.Conserv.Biol.25,428–437

20Rodewald,A.D.(2012)Spreadingmessagesaboutinvasives.Divers. Distrib.18,97–99

21Ehrenfeld, J.G. (2011) Ecosystem consequences of biological invasions.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Evol.Syst.41,59–80

22Vitule,J.R.S.etal.Revisitingtheconservationvalueofnon-native species.Cons.Biol.(inpress)

23Pattemore,D.E.andWilcove,D.S.(2012)Invasiveratsandrecent colonist birds partiallycompensate for the loss of endemic New Zealandpollinators.Proc.R.Soc.B79,1597–1605

24Richardson, D.M. (2006) Pinus:a model groupfor unlocking the secretsofalienplantinvasions?Preslia78,375–388

25Dehlin,H.etal.(2008)Treeseedlingperformanceandbelowground propertiesinstandsofinvasiveandnativetreespecies.N.Z.J.Ecol.32, 67–79

26Mack,M.C.andD’Antonio,C.M.(1998)Impactsofbiologicalinvasions ondisturbanceregimes.TrendsEcol.Evol.13,195–198

27Vila`,M.etal.(2010)Howwelldoweunderstandtheimpactsofalien species on ecosystem services? A pan-European, cross-taxa assessment.Front.Ecol.Environ.8,135–144

28Garcı´a-Berthou, E. et al. (2005) Introduction pathways and establishmentratesofinvasiveaquaticspeciesinEurope. Can.J. Fish.Aquat.Sci.62,453–463

29Lavergne,S.andMolofsky,J.(2007)Increasedgeneticvariationand evolutionarypotentialdrivethesuccessofaninvasivegrass.Proc. Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.104,3883–3888

30 Crooks,J.A.(2011)Lagtimes.InEncyclopediaofBiologicalInvasions

(Simberloff,D.andRejma´nek,M.,eds),pp.404–410,Universityof CaliforniaPress

31 Essl,F.etal.(2011)Socioeconomiclegacyyieldsaninvasiondebt.

Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.108,203–207

32 Gasso´,N.etal.(2010)Spreadingtoalimit:thetimerequiredfora neophytetoreachitsmaximumage.Divers.Distrib.16,310–311 33 Vitule,J.R.S.etal.(2009)Introductionofnon-nativefreshwaterfish

cancertainlybebad.FishFish.10,98–108

34 Simberloff,D.and Rejma´nek,M.,eds(2011)EncyclopediaofBiological Invasions,UniversityofCaliforniaPress

35 Vitousek,P.M.etal.(1987)BiologicalinvasionbyMyricafayaalters ecosystemdevelopmentinHawaii.Science238,802–804

36 Wardle,D.A.etal.(2011)Terrestrialecosystemresponsestospecies gainsandlosses.Science332,1273–1277

37 Bardgett,R.D.andWardle,D.A.(2010)Aboveground–Belowground Interactions: BioticInteractions, EcosystemProperties and Global Change,OxfordUniversityPress

38 Ordon˜ez,A.etal.(2010)Functionaldifferencesbetweennativeand alienspecies:aglobal-scalecomparison.Funct.Ecol.24,1353–1361 39 Ehrenfeld,J.G.(2003)Effectsofexoticplantinvasionsonsoilnutrient

cyclingprocesses.Ecosystems6,503–523

40 Liao,C.Z.etal.(2008)Alteredecosystemcarbonandnitrogencycles byplantinvasion:ameta-analysis.NewPhytologist117,706–714 41 Simberloff,D.(2011)Howcommonareinvasion-inducedecosystem

impacts?Biol.Invasions13,1255–1268

42 Vila`,M.etal.(2011)Ecologicalimpactsofinvasivealienplants:a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems.Ecol.Lett.14,702–708

43 Rejma´nek,M.andPitcairn,M.J.(2002)Wheniseradicationofexotic pestplantsarealisticgoal?InTurningtheTide:theEradicationof InvasiveSpecies(Veitch,C.R. andClout,M.N.,eds),pp.249–253, IUCNSSCInvasiveSpeciesSpecialistGroup

44 Gray,D.K.etal.(2007)Efficacyofopen-oceanballastwaterexchange asameansofpreventinginvertebrateinvasionsbetweenfreshwater ports.Limnol.Oceanogr.52,2386–2397

45 Roques,A.andAuger-Rozenberg,M-A.(2006)Tentativeanalysisof theinterceptionsofnon-indigenousorganismsinEurope1995–2004.

Bull.OEPP/EPPOBull.36,490–496

46 Derraik,J.G.B.(2004)Asurveyofthemosquito(Diptera:Culicidae) faunaoftheAucklandZoologicalPark.N.Z.Entomol.27,51–55 47 Keller,R.P.etal.(2007)Riskassessmentforinvasivespeciesproduces

netbioeconomicbenefits.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.104,203–207 48 Jarrad, F.C.etal. (2011)Improved design methodfor biosecurity surveillanceandearlydetectionofnon-indigenousrats.N.Z.J.Ecol.

35,132–144

49 Kaiser,B.A.andBurnett,K.M.(2010)Spatialeconomicanalysisof earlydetectionandrapidresponsestrategiesforaninvasivespecies.

Resour.EnergyEcon.32,566–585

50 Ficetola, G.F. etal.(2008) Species detectionusing environmental DNAfromwatersamples.Biol.Lett.4,423–425

51 Chown,S.etal.(2008)DNAbarcodingandthedocumentationofalien speciesestablishmentonsub-AntarcticMarionIsland.PolarBiol.31, 651–655

52 Harris,S.andTimmins,S.M.(2009)EstimatingtheBenefitofEarly ControlofallNewlyNaturalisedPlants(ScienceforConservation:Vol. 292),NewZealandDepartmentofConservation

53 Caut, S.etal.(2009)AvoidingsurpriseeffectsonSurpriseIsland: alien species control in a multi-trophic level perspective. Biol. Invasions11,1689–1703

54 Genovesi,P.(2011)Areweturningthetide?Eradicationsintimesof crisis:howtheglobalcommunityisrespondingtobiologicalinvasions. InIslandInvasives:EradicationandManagement(Veitch,C.R.etal., eds),pp.5–8,IUCN

55 Panzacchi, M.etal.(2007)Population controlofcoypuMyocastor coypusinItalycomparedtoeradicationinUK:acost–benefitanalysis.

Wildl.Biol.13,159–171

56 McGeoch,M.A.etal.(2010)Globalindicatorsofbiologicalinvasion: species numbers,biodiversityimpactand policyresponses. Divers. Distrib.16,95–108

57 Fine,J.M.andSorensen,P.W.(2008)Isolationandbiologicalactivity ofthemulti-componentsealampreymigratorypheromoneandnew informationinitspotency.J.Chem.Ecol.34,1259–1267

58 Pala,C.(2008)Invasionbiologistssuckitup.Front.Ecol.Environ.6, 63

59 Aldridge,D.C. etal. (2006)MicroencapsulatedBioBulletsfor the controlofbiofoulingzebramussels.Environ.Sci.Technol.40,975– 979

60 Martin,J.L.etal.(2000)Blackrats,islandcharacteristicsandcolonial nesting birds in the Mediterranean: current consequences of an ancientintroduction.Conserv.Biol.14,1452–1466

61 Williamson,M.(1998) Measuringtheimpact ofplant invaders in Britain. In Plant Invasions: Ecological Mechanisms and Human Responses(Starfinger,U.etal.,eds),pp.57–68,BackhuysPublishers 62 Gaertner, M.et al. (2012) Insights into invasion and restoration

ecology: time tocollaboratetowards aholistic approach to tackle biologicalinvasions.NeoBiota12,57–76

63 Golumbia,T.etal.(2008)Historyandcurrentstatusofintroduced vertebratesonHaidaGwaii.InLessonsfromtheIslands:Introduced SpeciesandWhatTheyTellUsAboutHowEcosystemsWork(Gaston, A.J.etal.,eds),pp.8–31,CanadianWildlifeService

64 Martin,J.L.etal.(2010)Top-downandbottom-upconsequencesof unchecked ungulate browsing on plant and animal diversity in temperateforests:lessonsfromadeerintroduction.Biol.Invasions

12,353–371

65 Hendrix,P.F.etal.(2008)Pandora’sBoxcontainedbait:theglobal problem of introduced earthworms. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 39, 593–613

66 Sax,D.F.andGaines,S.D.(2008)Speciesinvasionsandextinction: thefutureofnativebiodiversityonislands.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci. U.S.A.105,11490–11497

67 Hobbs, R.J. et al. (2009) Novel ecosystems: implications for conservationandrestoration.TrendsEcol.Evol.24,599–605 68 Mascaro,J.etal.(2012)Novelforestsmaintainecosystemprocesses

afterthedeclineofnativetreespecies.Ecol.Monogr.82,221–228 69 Nagel,T.(1961)TheStructureofScience–ProblemsintheLogicof

ScientificExplanation,ColumbiaUniversityPress

70 Larson,B.M.H.(2011)MetaphorsforEnvironmentalSustainability: RedefiningOurRelationshipwithNature,YaleUniversityPress 71 Pauly,P.J.(1996)Thebeautyand menaceoftheJapanesecherry

trees:conflictingvisionsofAmericanecologicalindependence.Isis87, 51–73

72 Perry,D.andPerry,G.(2008)Improvinginteractionsbetweenanimal rightsgroupsandconservationbiologists.Conserv.Biol.22,27–35 73 CouncilofEurope(2000)DeclarationonCulturalDiversity,Councilof

Europe

74 UNESCO (2001) UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity,UNESCO

75 Born,W.etal.(2005)Economicevaluationofbiologicalinvasions:a survey.Ecol.Econ.55,321–336

76 Ville´ger, S. et al. (2011) Homogenization patterns of theworld’s freshwaterfishfaunas.Proc. Natl.Acad.Sci. U.S.A. 108,18003– 18008

77 Lambertini,M.etal.(2011)Invasives:amajorconservationthreat.

Science6041,404–405

78 Callicott,J.B.(1980)AnimalLiberation:atriangularaffair.Environ. Ethics4,311–338

79 Maris, V. and Be´chet, A. (2010) From adaptive management to adjustivemanagement:apragmaticaccountofbiodiversityvalues.

Conserv.Biol.24,966–973

80 MacDougall,A.S.andTurkington,R.(2005)Areinvasivespeciesthe driversorpassengersofchangeindegradedecosystems?Ecology86, 42–55

81 Martin,P.H.etal.(2009)Whyforestsappearresistanttoexoticplant invasions:intentionalintroductions,standdynamics,andtheroleof shadetolerance.Front.Ecol.Environ.7,142–149

82 Simberloff,D.(2009) Theroleof propagule pressureinbiological invasions.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Evol.Syst.40,81–102

83 Lovett, G.M. et al. (2006) Forest ecosystem responses to exotic pests and pathogens in eastern North America. BioScience 56, 395–405

84 Wardle,D.A.etal.(2001)Impactsofintroducedbrowsingmammalsin NewZealandforests ondecomposercommunities,soilbiodiversity andecosystemproperties.Ecol.Monogr.71,587–614

85 Anderson,C.B.etal.(2006)TheeffectsofinvasiveNorthAmerican beaversonriparianplantcommunitiesinCapeHorn,Chile:doexotic

beavers engineer differently in sub-Antarctic ecosystems? Biol. Conserv.128,467–474

86 Sala,E.etal.(2011)Alienmarinefishesdepletealgalbiomassinthe easternMediterranean.PLoSONE6,e17356

87 O’Dowd,D.J.andGreen,P.T.(2010)Invasionalmeltdown:doinvasive antsfacilitatesecondaryinvasions?InAntEcology(Lach,L.etal., eds),pp.271–272,OxfordUniversityPress

88 Fukami, T. et al. (2006) Above- and below-ground impacts of introducedpredatorsinseabird-dominatedislandecosystems.Ecol. Lett.9,1299–1307

89 Croll,D.A.et al.(2005) Introducedpredators transform subarctic islandsfromgrasslandtotundra.Science307,1959–1961

90Baxter,C.V.etal. (2004)Fishinvasionrestructuresstreamand forestfoodwebsbyinterruptingreciprocalpreysubsidies.Ecology

85,2656–2663

91 Pringle, R.M. (2011) Nile Perch. In Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions (Simberloff, D. and Rejma´nek, M., eds), p. 484, UniversityofCaliforniaPress

92 Loo,J.A.(2009)Ecologicalimpactsofnon-indigenousinvasivefungi asforestpathogens.Biol.Invasions11,81–96

93Boag,B.andNeilson,R.(2006)ImpactofNewZealandflatwormon agricultureandwildlifeinScotland.Proc.CropProt.NorthernBr.

2006,51–55

94Sousa,R.etal.(2009)Non-indigenousinvasivebivalvesasecosystem engineers.Biol.Invasions11,2367–2385

95Talley, T.S.etal.(2001) Habitatutilizationand alterationbythe burrowingisopod,Sphaeromaquoyanum,inCaliforniasaltmarshes.

Mar.Biol.138,561–573

96Woodfield,R.etal.(2006)FinalReportontheEradicationoftheInvasive SeaweedCaulerpataxifoliafrom AguaHedionda Lagoon andHuntington Harbour,California,SouthernCaliforniaCaulerpaActionTeam 97Meinesz,A.(2001)KillerAlgae,UniversityofChicagoPress 98Boyer,A.(2008)ExtinctionpatternsintheavifaunaoftheHawaiian

islands.Divers.Distrib.14,509–517

99Rodriguez-Cabal,M.A.etal.(inpress)Theestablishmentsuccessof non-nativebirdsinHawaiiandBritain.Biol.Invasions

100Apostol,D.and Shlisky, A.(2012) Restoringtemperateforests, a North American perspective, In Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier(2ndedn)(VanAndel,J. and Aronson,J.,eds),pp.161– 172,Wiley-Blackwell