Effects

of

multiple

interventions

for

reducing

vocal

stereotypy:

Developing

a

sequential

intervention

model

Marc

J.

Lanovaz

a,*

,

John

T.

Rapp

b,

Isabella

Maciw

a,

E´milie

Pre´gent-Pelletier

a,

Catherine

Dorion

a,

Ste´phanie

Ferguson

a,

Sabine

Saade

aa

E´coledepsychoe´ducation,Universite´ deMontre´al,C.P.6128,succ.Centre-Ville,Montre´al,QC,H3C3J7Canada

bDepartmentofPsychology,AuburnUniversity,229CaryHall,Auburn,AL36849-5214,UnitedStates

1. Introduction

Individualswithautismspectrumdisordersoftenengageinvariousformsofvocalstereotypy(e.g.,repeatingpreviously heardwords,producingmeaninglesssounds),whichmaybedisruptivetoothersandinterferewithsocialinclusion(Lanovaz & Sladeczek, 2012; MacDonald et al., 2007; Matson,Dempsey, & Fodstad, 2009; Mayes & Calhoun, 2011). Response interruptionandredirection(RIRD;e.g.,Ahearn,Clark,MacDonald,&Chung,2007;Schumacher&Rapp,2011),responsecost (e.g.,Falcomata,Roane,Hovanetz,Kettering,&Keeney,2004;Watkins&Rapp,2014),noncontingentmusic(e.g.,Lanovaz& Sladeczek,2011;Saylor,Sidener,Reeve,Fetherston,&Progar,2012),anddifferentialreinforcementofotherbehavior(DRO;

Rozenblat,Brown,Brown,Reeve,&Reeve,2009;Taylor,Hoch,&Weissman,2005)areexamplesofinterventionsthathave amassedvaryinglevelsofempiricalsupportforthetreatmentofvocalstereotypyintheresearchliterature.Despitethe availabilityofseveralinterventions,fewstudieshavecomparedtwoormoreinterventionstogether(Shabani&Lam,2013).

ARTICLE INFO

Articlehistory:

Received30October2013

Receivedinrevisedform23January2014 Accepted28January2014 Keywords: Differentialreinforcement Interventionmodel Music Prompting Stereotypy ABSTRACT

Despitetheavailabilityofseveralinterventionsdesignedtoreduceengagementinvocal stereotypy,fewstudieshavecomparedtwoormoreinterventionstogether.Consequently, practitionershavelimitedamountofdatatomakeinformeddecisionsonwhetheran interventionmaybemoresuitablethananothertobegintreatingvocalstereotypy.The purposeofthestudywastoaddressthislimitationbyexaminingthedirectandcollateral effectsofmultipleinterventionsin12individualswithautismandotherdevelopmental disabilitiesinordertoguidethedevelopmentofasequentialinterventionmodel.Using single-case experimentaldesigns, we conducted aseries of four experiments which showedthat(a)noncontingentmusicgenerallyproducedmoredesirableoutcomesthan differentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior,(b)differentialreinforcementofother behaviorreducedvocalstereotypyintwoparticipantsforwhomnoncontingentmusichad failedtodoso,(c)theadditionofsimplepromptingproceduresmayenhancetheeffectsof theinterventions,and(d)theeffectsofnoncontingentmusicmaypersistduringsessions withextendeddurations.Basedontheseresults,weproposeasequentialintervention modeltofacilitatetheinitialandsubsequentselectionofaninterventionmostlikelyto reducevocalstereotypywhileproducingdesiredcollateraloutcomes.

ß2014TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.

* Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+15143436111x81774. E-mailaddress:marc.lanovaz@umontreal.ca(M.J.Lanovaz).

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Research

in

Autism

Spectrum

Disorders

J ou rna l hom e pa ge : h tt p: / / e e s . e l se v i e r . com / R AS D / de f a ul t . a s p

1750-9467ß2014TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.01.009

Open access under CC BY license.

Consequently,practitionershavelimitedamountofdatatomakeinformeddecisionsonwhetheraninterventionmaybe moresuitablethananothertobegintreatingvocalstereotypy.

Inanotableexception,Love,Miguel,Fernand,andLaBrie(2012)comparedtheeffectsofRIRDandnoncontingentaccess totoysthatproduceauditorystimulationonengagementinvocalstereotypyandappropriatevocalizationsintwo school-agedboyswithautism.Theirresultsindicatedthatbothinterventionsreducedvocalstereotypytosimilarlevels,butthat RIRDproducedlargerincreasesinappropriatevocalizations.Oneofthemainstrengthsofthestudywasthattheresearchers measuredtheeffectsoftheinterventiononotherbehavior.Measuringvocalstereotypyalonewouldhaveindicatedthatboth interventionswereequallyeffectivewhereasconsideringtheappropriatevocalizationssuggestedthatRIRDproduceda moredesirable outcome. In somesettings,individualswithdevelopmentaldisabilities maybeexpected toengage in alternativebehaviorotherthanappropriatevocalizations.Forexample,thevocalizationsmaybedisruptivetoothers(e.g., classmates,colleagues)orinterferewithotheralternativebehavior(e.g.,completingatask).Thenagain,otherindividuals maybeunavailabletorespondtotheappropriatevocalizations.PractitionersshouldalsonotethatRIRDoftenrequiresthe ongoingimplementationofapunishmentcontingency(e.g.,Carroll&Kodak,inpress;Cassella,Sidener,Sidener,&Progar, 2011),whichmaybechallengingincertainsettingsorwhenthecontingentdemandsevokeaggressivebehavior.

Two interventions that may be appropriate alternatives in such settings are noncontingent access to music and differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA). Noncontingent music involves playing preferred music continuouslythroughexternalspeakersorheadphones(e.g.,Lanovaz&Sladeczek,2011;Sayloretal.,2012).Themain advantageofnoncontingentmusicisthatitisarguablythesimplestinterventiontoimplementforvocalstereotypy.The practitioneronlyneedstoturnonpreferredmusic,whichallowshertoattendtoothertasksduringthistime.Moreover,the interventionmaynotbedisruptivetootherswhenheadphonesareusedtoprovidethemusic.Whethernoncontingentmusic willinterferewithaperson’sownappropriatebehaviorremainsunclearintheresearchliterature.Burleson,Center,and Reeves(1989)foundthatbackgroundmusicincreasedtaskaccuracyinchildrenwithautism.Inanotherstudy,Lanovaz, Sladeczek,andRapp(2012)reportedmixedresultsonthefunctionalplayoffourchildren:musicincreasedfunctionalplayin one participant,reduced functional play in another, and produced no effecton thesame behavior of theremaining participants.

Asecondconcernisthatplayingnoncontingentmusicmayincreaseengagementinuntargetedformsofmotorstereotypy (Rapp,2005;Rappetal.,2013). Froma clinicalstandpoint,reducing oneformofstereotypywithaninterventionthat increasesa secondformwouldbecounterproductive.Aneffectiveinterventionshouldreduce,oratleastnotincrease, untargetedmotorformsof stereotypy.Finally,researchershavegenerallyassessedtheeffects ofnoncontingentmusic during5-to10-minbriefsessions(e.g.,Rappetal.,2013;Sayloretal.,2012).Resultsofastudyconductedusingitemsthat weremanipulatedbyparticipantsindicatedthattheeffectsofnoncontingentaccessmaynotcontinueduringextended sessionsbecauseindividualsmaystoptoengagewiththeitemsfollowingrepeatedexposure(Lindberg,Iwata,Roscoe, Worsdell,&Hanley,2003).Thatsaid,theeffectsofextendedapplicationofmusicmaydifferbecausetheindividualdoesnot needtoengageinaresponsetoaccesstheauditorystimulation;themusicplaysthroughouttheentiresessionregardlessof theindividual’sbehavior.

AnotherpotentialtreatmentisDRA,whichisoneofthebehavioralinterventionswiththemostempiricalsupportto reduceengagementinstereotypy(DiGennaroReed,Hirst,&Hyman,2012;Rapp&Vollmer,2005).Themainadvantageof DRAisthattheinterventionmaysimultaneouslystrengthenanappropriatebehavior,minimizingtheprobabilitythatitwill bereplacedbyanotherformofstereotypy(Lanovaz,Robertson,Soerono,&Watkins,2013).However,mostpriorstudieshave examinedtheeffectsofDRAonmotorstereotypy.Giventhatengagementinvocalstereotypyisnotnecessarilyincompatible withmanyalternativebehavior(e.g.,playing,completingatask),theeffectsofDRAmaydifferfromthoseobservedwith motorformsofthebehavior.Inarecentexception,Lanovaz,Rapp,andFerguson(2013)foundthatreinforcinganappropriate behaviorassociated withlow levelsof vocalstereotypy (i.e.,sitting) producedreductions in vocalstereotypyfor one participant.Inappliedsettings,thealternativebehaviortargetedforincreasemaynotnecessarilybeassociatedwithlow levels of stereotypy. Assuch, it remains unclear whether strengthening an appropriate behavior, independent of its associationwithlowlevelsofvocalstereotypy,wouldalsoproducedesirableoutcomes.

Basedonthepreviouslimitations,themainpurposeofthestudywastoinvestigatethedirectandcollateraloutcomesof multipleinterventionsinindividualswithautismandotherdevelopmentaldisabilitiesinordertoguidethedevelopmentof asequentialinterventionmodelforvocalstereotypy.WefirstexaminedtheeffectsofnoncontingentmusicandDRAon engagementinvocalstereotypy,motorstereotypy,andappropriatealternativebehavior.Thestudyalsoaimedtoidentify potentialmodificationswhentheinterventionsdidnotreduceengagementinvocalstereotypy,orproducedoneormore undesirablecollateraleffects.Lastly,weexaminedpotentiallimitationsinordertoassistpractitionersinmakinginformed decisionswhenselectinganinterventiontoreduceengagementinvocalstereotypy.

2. Generalmethod

2.1. Participants,datacollection,responsedefinitions,andinterobserveragreement

Twelveindividualswithautismandotherdevelopmentaldisabilitiesparticipatedinoneortwoexperiments.Fourofthe participants(i.e.,David,Eric,FredandGreg)hadbeeninvolvedinotherexperimentsontheassessmentandtreatmentof stereotypyconductedbythefirsttwoauthors(seeLanovaz,Rapp,&Ferguson,2012;Rappetal.,2013).Eachparticipant

engagedinvocalstereotypyandfiveparticipantsalsoengagedinoneormoreformsofmotorstereotypy.Basedonthe environmentin whichtheinterventionsweretobeimplemented,wealsotargetedoneappropriatebehaviorforeach participantduringthestudy.Table1presentseachparticipant’sage,diagnosis,andresponseforms.Weonlyreportmotor formsofstereotypywhenthemeanpercentageofengagementwasatleast10%duringbaselinesessions.

Trainedresearchassistantsvideotapedeachsessionandsubsequentlyscoredthedurationofeachformofstereotypyand appropriatebehavior.Table2presentsthedefinitionusedtomeasureeachresponseform.Weuseda2-soffsetcriterionto measurevocalstereotypyforeachparticipant.ForJacob,wemeasuredtheproductofhisappropriatebehavior(i.e.,task completion)ratherthanthedurationbycountingthenumberofitemsthathehadtransferredfromonecontainertoanother attheendofthesession.Asecondresearchassistantmeasuredinterobserveragreement(IOA)forapproximately35%of sessionsforeachparticipantusingtheblock-by-blockmethodwith10-sintervals.ThemeanIOAscoresandrangesforeach participantarepresentedinTable1.

Table1

Characteristicsoftheparticipants.

Participant Age Diagnosis ResponseForms IOAscores Nicholas 12 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Pacing On-taskbehavior M=87%(range:83–94%) M=93%(range:82–99%) M=91%(range:83–97%) Zoe 36 ProfoundID DownSyndrome VocalStereotypy Rocking Fingerwiggling Facetouching Objectmanipulation M=91%(range:80–98%) M=93%(range:86–100%) M=87%(range:78–95%) M=90%(range:85–93%) M=93%(range:83–100%) Kyle 4 Autism Vocalstereotypy

On-taskbehavior M=90%(range:83–95%) M=91%(range:83–100%) Morgan 6 GDD Languagedisorder Vocalstereotypy On-taskbehavior M=93%(range:88–99%) M=90%(range:84–96%) Lucas 37 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Magazineviewing

M=90%(range:80–100%) M=93%(range:88–97%) Ryan 7 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Functionalplay

M=88%(range:71–93%) M=97%(range:94–100%) Yasmine 63 ProfoundID Vocalstereotypy

On-taskbehavior

M=74%(range:65–79%) M=96%(range:87–100%) David 6 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Functionalplay

M=96%(range:93–98%) M=93%(range:83–100%) Jacob 5 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Mouthing Objecttapping Taskcompletion M=86%(range:82–91%) M=95%(range:93–100%) M=93%(range:87–98%) N/A

Eric 4 Autism Vocalstereotypy Mouthing Functionalplay

M=95%(range:91–100%) M=98%(range:97–100%) M=76%(range:66–83%) Fred 9 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Objecttapping Functionalplay

M=93%(range:87–98%) M=89%(range:85–92%) M=86%(range:81–91%) Greg 6 Autism Vocalstereotypy

Functionalplay

M=90%(range:86–94%) M=90%(range:82–94%) Notes:GDD,globaldevelopmentaldelay;ID,intellectualdisability;IOA,interobserveragreement.

Table2

Responsedefinitions.

Responseform Definition

Vocalstereotypy Acontextualsoundsorwordsproducedbythevocalapparatus Pacing Walkinginacircularmotion

Bodyrocking Twoormoreforwardandbackwardtorsomovements

Fingermoving Backandforthmotionoffingerswithorwithoutholdinganobject Facetouching Contactbetweenthefingersandfaceorneck

Mouthing Insertionofabodypartornon-edibleobjectpasttheplaceofthemouth Objecttapping Twoormoremovementsofthefingerorhandmakingcontactwithasurface On-taskbehavior Usingtaskmaterialsinamannerconsistentwiththeirintendedfunction Objectmanipulation Holdinganobjectinoneorbothhands

Magazineviewing Lookingatapageofamagazineforatleast3swithoutturningthepageorlookingelsewhere Functionalplay Usingplaymaterialsinamannerconsistentwiththeirintendedfunction

2.2. Preliminaryassessments

2.2.1. Seriesofno-interactionconditions

Priortothestartofthecurrentstudy,weconductedaseriesof8–21no-interactionconditionstoexaminewhethereach participant’srepetitivevocalizationspersistedintheabsenceofsocialconsequences.Duringeach5-mincondition,the participantshadtheopportunitytoengageinthetargetappropriatebehaviorthatwouldbemeasuredinthesubsequent experiments(e.g., playing, completinga task),but we providedno social consequences. Persistence of the repetitive vocalizationsacrosstheconditionsindicatedthatthebehaviorwasatleastpartlyautomaticallyreinforced(Querimetal., 2013).Weexcludedparticipantswhoserepetitivevocalizationsdidnotpersistacrosstheseriesofno-interactionconditions orthatdidnotoccurforatleast15%ofthetime.Assuch,thevocalstereotypyofallparticipantsinthecurrentstudypersisted duringtheseriesofno-interactionconditions.Thedetailedresultsoftheassessmentarepublishedelsewhereforsome participants(Lanovaz,Rapp,etal.,2012)andavailablefromthefirstauthorfortheothers.

2.2.2. Stimuluspreferenceassessment

Dependingonthetypeofstimuliinvolvedintheirinterventions,eachindividualparticipatedinpreferenceassessments foredibles,music,orboth.Theresearchassistantselectedfivetoeightstimulipresentedduringeachpreferenceassessment incollaborationwiththeindividual’scaregiver.Toassesspreferenceforedibleitems,weusedthepaired-choicestimulus preferenceassessment (Fisheret al.,1992). For music, weconducteda modified paired-choicepreference assessment (Horrocks&Higbee,2008;Lanovaz,Rapp,etal.,2013).Thestimulusselectedthemostoftenduringeachassessmentwas usedasthereinforcerorpreferredstimulusduringtheinterventions.ForJacob,theexperimenterselectedthemusical stimulusincollaborationwiththecaregiverbecausehisresultsindicated thatheselectedsongsregardlessof musical preference(i.e.,basedonthesideofpresentation).

3. Experiment1:directandcollateraleffectsofnoncontingentmusicanddifferentialreinforcementofalternative behavior

3.1. Participants,materials,andsettings

Nicholas,Zoe,Kyle,Morgan,Lucas,Ryan,andYasmineparticipatedinthefirstexperiment.Weconductedthesessionsin settingsinwhichtheparticipantstypicallyengagedintheirappropriatetargetbehavior.Duringtheirsessions,Nicholas, Kyle,andMorgan,hadaccesstomaterialstocompletefinemotoractivities(e.g.,puzzles,beadsandthreads,pushpins, tracing)whereas Yasmine had clothesto fold. We selectedthesetasks because theparticipantscould performthem independentlyandcompletethemwithinthedurationofthesession.Theotherparticipantsengagedinobjectmanipulation orfunctionalplay:Zoehadcontinuousaccesstoitemsthatprovidedsensorystimulation,Lucastomagazines,andRyanto age-appropriatetoys.

3.2. Procedures

Tocomparetheeffectsofthetwointerventions,wealternatedbaseline,noncontingentmusic,andDRAconditionswithin amultielementdesign.WiththeexceptionofYasminewhosesessionswere15mininduration,wemeasuredeachresponse formfor10minduringandfor10minaftertheintervention.Forindividualsengagingintasks,thesessionwasterminatedif theindividualfinishedhisorherseriesoftasksbeforetheendofthe10-minsession.Thepost-interventionsessionswerethe sameasbaseline(seebelow),regardlessoftheprecedingintervention.Wedidnotmeasurepost-interventioneffectsfor Yasminebecausehertaskalreadylasted15minandshehadlimitedavailabilities.

Atthestartofeachbaselinesession,theparticipantswerepromptedtoengageintheirappropriatebehavior(e.g.,the researchassistantsaid,‘‘doyourtask’’or‘‘youcanplaynow’’).Nofurtherconsequenceswereprovidedduringtheentire durationofthesession.Thenoncontingentmusicconditionwassimilartobaselinewiththeexceptionthattheparticipant’s mostpreferredsongplayedcontinuouslyforthedurationofthesessionthroughexternalspeakersinthebackground.During theDRAcondition,weprovidedareinforceronavariable-interval(VI)schedulecontingentonengagementinthetarget appropriatebehavior.Initially,thedurationoftheintervalwas8sforMorgan.ForLucas,wehadinitiallystartedwith15s andchangedto8s,whichallowedustoexaminewhetherthedenserscheduleproducedmoredesirableoutcomes.Our preliminarydataindicatedthatthedenseschedulesmayhaveinterruptedengagementinappropriatebehaviorandbe unpracticaltoimplementinappliedsetting;asaresult,weonlyused15-sintervalsfortheotherparticipants.Weprovided edibleitemsasreinforcersforallparticipantsexceptNicholasbecausehedidnotselectasingleedibleitemduringthe preferenceassessment.Instead,weusedmusicasareinforcer,whichweprovidedona15-sVIschedule.WhenNicholasmet thereinforcementschedulerequirement,weturnedonthemusicuntiltheendoftheongoinginterval.

3.3. Resultsanddiscussion

Foreachexperiment,wepresenttheimmediateeffectsoftheinterventionsforeachparticipantinagraphicalformat. However,thegraphsdepictingthesubsequenteffectswerepresentedonlywhentheinterventionproducedbothimmediate

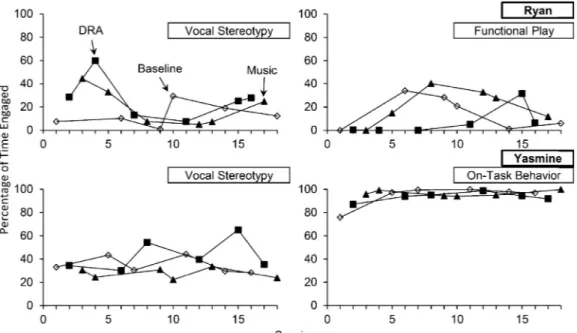

andsubsequentchangesinatleastoneresponseform.Otherwise,wereportthemeansandrangesintables.Notethatthe subsequentgraphsthatwerenotincludedinthecurrentpaperareavailablefromthefirstauthor.Table3presentsthemeans andrangesforeachparticipant’sresponseforms.Fig.1showsthepercentageoftimeNicholas(threeupperpanels)andZoe (fivelowerpanels)engagedinstereotypyandappropriatebehaviorduringtheinterventions.ForNicholas,noncontingent musicreducedvocalstereotypyandpacingwhileincreasingon-taskbehaviorwhereasDRAdidnotproduceconsistent effectswhencomparedtobaseline.Incontrast,DRAreducedvocalstereotypy(thoughnottoclinicallysignificantlevels), body rockingand fingermoving,and marginallyincreasedobjectmanipulation for Zoe.Noncontingent music didnot produceclearchangesinherresponseforms.Forbothparticipants,post-interventionlevelsofeachresponseformremained similaracrossconditions(datanotdepicted).

Fig.2showstheresultsoftheanalysesforKyle(fourupperpanels),Morgan(twolowermiddlepanels),andLucas(two lowerpanels).ForKyle,noncontingentmusicreducedimmediateengagementinvocalstereotypyandmaintainedhigher levels of on-taskbehavior than theother conditions.The intervention alsoreduced subsequent engagementin vocal stereotypy,buttheeffectsappearedtofadeovertime.Incontrast,DRAdidnotproducesystematicchangesineithervocal stereotypyoron-taskbehavior.ForMorgan,bothinterventionsdecreasedengagementinvocalstereotypycomparedto

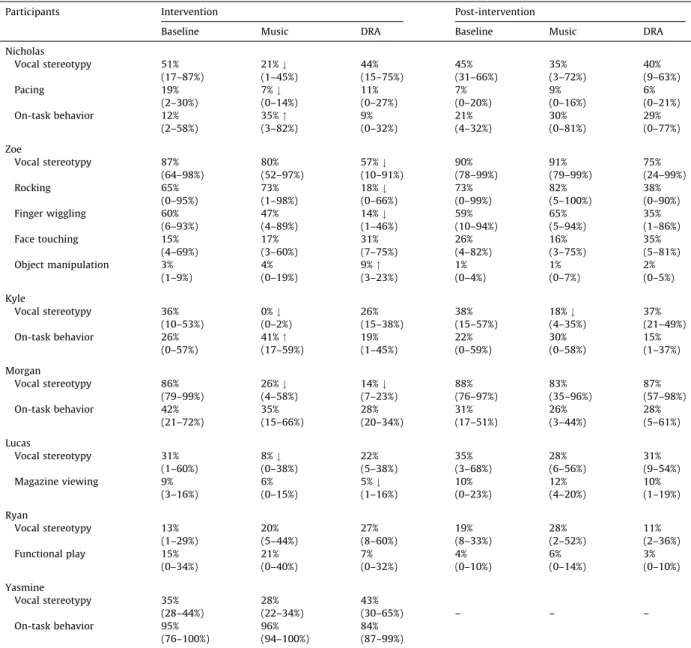

Table3

MeansandrangesforeachparticipantacrossconditionsforExperiment1.

Participants Intervention Post-intervention

Baseline Music DRA Baseline Music DRA Nicholas Vocalstereotypy 51% 21%# 44% 45% 35% 40% (17–87%) (1–45%) (15–75%) (31–66%) (3–72%) (9–63%) Pacing 19% 7%# 11% 7% 9% 6% (2–30%) (0–14%) (0–27%) (0–20%) (0–16%) (0–21%) On-taskbehavior 12% 35%" 9% 21% 30% 29% (2–58%) (3–82%) (0–32%) (4–32%) (0–81%) (0–77%) Zoe Vocalstereotypy 87% 80% 57%# 90% 91% 75% (64–98%) (52–97%) (10–91%) (78–99%) (79–99%) (24–99%) Rocking 65% 73% 18%# 73% 82% 38% (0–95%) (1–98%) (0–66%) (0–99%) (5–100%) (0–90%) Fingerwiggling 60% 47% 14%# 59% 65% 35% (6–93%) (4–89%) (1–46%) (10–94%) (5–94%) (1–86%) Facetouching 15% 17% 31% 26% 16% 35% (4–69%) (3–60%) (7–75%) (4–82%) (3–75%) (5–81%) Objectmanipulation 3% 4% 9%" 1% 1% 2% (1–9%) (0–19%) (3–23%) (0–4%) (0–7%) (0–5%) Kyle Vocalstereotypy 36% 0%# 26% 38% 18%# 37% (10–53%) (0–2%) (15–38%) (15–57%) (4–35%) (21–49%) On-taskbehavior 26% 41%" 19% 22% 30% 15% (0–57%) (17–59%) (1–45%) (0–59%) (0–58%) (1–37%) Morgan Vocalstereotypy 86% 26%# 14%# 88% 83% 87% (79–99%) (4–58%) (7–23%) (76–97%) (35–96%) (57–98%) On-taskbehavior 42% 35% 28% 31% 26% 28% (21–72%) (15–66%) (20–34%) (17–51%) (3–44%) (5–61%) Lucas Vocalstereotypy 31% 8%# 22% 35% 28% 31% (1–60%) (0–38%) (5–38%) (3–68%) (6–56%) (9–54%) Magazineviewing 9% 6% 5%# 10% 12% 10% (3–16%) (0–15%) (1–16%) (0–23%) (4–20%) (1–19%) Ryan Vocalstereotypy 13% 20% 27% 19% 28% 11% (1–29%) (5–44%) (8–60%) (8–33%) (2–52%) (2–36%) Functionalplay 15% 21% 7% 4% 6% 3% (0–34%) (0–40%) (0–32%) (0–10%) (0–14%) (0–10%) Yasmine Vocalstereotypy 35% 28% 43% (28–44%) (22–34%) (30–65%) – – – On-taskbehavior 95% 96% 84% (76–100%) (94–100%) (87–99%)

Notes:DRA:differentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior,":increasecomparedtobaseline(basedonvisualinspectionofmultielementgraph),#: reductioncomparedtobaseline.

baseline,butDRAproducedalargermeanreduction.Theinterventionsdidnotincreaseengagementinon-taskbehavior. Post-interventionlevelsalsoremainedsimilaracrossconditions(datanotdepicted).NoncontingentmusicreducedLucas’ vocalstereotypyanddidnotinterferewithmagazineviewing.Contrarily,DRAdidnotsystematicallyalterengagementinhis vocalstereotypy,butdecreasedengagementinmagazineviewing.Wedidnotobserve anyconsistentchangesin post-interventionlevelsforbothresponseforms(datanotdepicted).Fig.3showsthatthetwointerventionsfailedtoproduce systematicchangesinstereotypyandappropriatebehaviorforRyanandYasmine.

Atleast one of thetwo interventionsreduced immediate engagementin vocal stereotypy for 5 of7 participants. Noncontingent music reduced immediate engagement in vocal stereotypyin fourparticipants, increasedappropriate behaviorintwoofthem,andalsoreducedcollateralmotorformsofstereotypyinoneparticipant.Ontheotherhand,DRA reduced immediate engagement in vocal stereotypy in two participants, motor stereotypy in one participant, and appropriatebehaviorinoneparticipant.Fortwooftheparticipants,bothinterventionsfailedtoproducedesirableoutcomes, underliningtheimportanceofexaminingotheralternatives.

4. Experiment2:directandcollateraleffectsofdifferentialreinforcementofotherbehavior

ResearchershaveshownthatDROmaybeaneffectiveinterventiontoreduceengagementinvocalstereotypy(e.g.,

Rozenblatetal.,2009;Tayloretal.,2005).Whenthefirstinterventionfailstoreduceengagementinvocalstereotypy,DRO maythusbeasuitablealternativeinasequentialinterventionmodel.Similarlytootherinterventions,theuseofDROis

Fig.1.PercentageoftimeNicholas(threeupperpanels)andZoe(fivelowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypy,motorstereotypy,andappropriatebehavior duringbaseline,noncontingentmusic,anddifferentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)sessions.

limitedinsofarasitseffectsonappropriatebehaviorhavenotbeenthoroughlydocumentedbyresearchers.Thepurposeof thesecondexperimentwastoexaminethedirectandcollateraleffectsofimplementingDROtoreduceengagementinvocal stereotypy.

4.1. Participantsandsettings

RyanandYasmineparticipatedinthisexperimentbecausebothnoncontingentmusicandDRAhadfailedtoreducetheir engagementinstereotypyduringthefirstexperiment.WealsoincludedDavidforwhomnoncontingentmusicdidnot reducevocalstereotypyinapreviousstudy(Lanovaz,Rapp,etal.,2012).ForRyanandYasmine,thesettingsandmaterials werethesameasExperiment1.Davidhadnoncontingentaccesstoage-appropriatetoys.

4.2. Procedures

TheexperimentaldesignanddataanalyseswerethesameasinExperiment1withthefollowingexceptions.Weusedan ABdesignforYasminetoreducethenumberofsessionsconductedwithherduetoherlimitedavailabilities.Giventhather resultsshowedthattheinterventionclearlyincreasedengagementinvocalstereotypy,wedidnotconductareturnto baseline.ThebaselineconditionswerethesameasinExperiment1.DuringDRO,theparticipantreceivedaccesstothe

Fig.2.PercentageoftimeKyle(fourupperpanels),Morgan(twolowermiddlepanels),andLucas(twolowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypyand appropriatebehaviorduringandfollowingbaseline,noncontingentmusic,anddifferentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)sessions.

reinforcerwhenheorshehadnotengagedinvocalstereotypyduringtheentireinterval.Iftheparticipantengagedinvocal stereotypyatanypointintime,theintervalwasreset.RyanandYasminereceivedediblereinforcerswhereasDavidreceived accesstothemusicforaperiodequivalenttothedurationoftheinterval.ForDavid,westartedwithafixed-duration8-s interval,butthinneditupto30s.Weusedafixed-duration10-sintervalforRyanandYasmine.

4.3. Resultsanddiscussion

Table4presentsthemeansandrangesoftheresponseformsforthethreeparticipants.Fig.4displaysthemultielementgraphs foreachparticipant.ForDavid,DROreducedbothimmediateandsubsequentengagementinvocalstereotypy,butimmediateand subsequentlevelsoffunctionalplayremainedconsistentlylow.ForRyan,DROalsoreducedimmediateengagementinvocal stereotypy,butproducedmarginalpost-interventionincreasesintheresponseform.Wedidnotobservesystematicchangesin functionalplay.ForYasmine,DROneitherreducedvocalstereotypynorincreasedappropriatebehavior,whichwasalreadynear 100%duringbaseline.OurresultssuggestthatDROmayreducevocalstereotypywhenotherinterventionshavefailedtodoso,but thattheinterventiondoesnotnecessarilyevoke,orproducereallocationtoward,appropriatebehavior.

Table4

MeansandrangesforeachparticipantacrossconditionsforExperiment2.

Intervention Post-intervention

Participants Baseline DRO Baseline DRO

David Vocalstereotypy 39% 6%# 47% 32%# (1–60%) (0–38%) (23–61%) (12–45%) Functionalplay 7% 11% 8% 12% (0–23%) (0–76%) (0–46%) (0–96%) Ryan Vocalstereotypy 35% 18%# 19% 31%" (11–68%) (4–46%) (10–49%) (19–85%) Functionalplay 14% 5% 18% 15% (0–41%) (0–15%) (0–67%) (0–45%) Yasmine Vocalstereotypy 35% 57%" (28–44%) (42–74%) – – On-taskbehavior 95% 98% (76–100%) (95–100%)

Notes:DRO:differentialreinforcementofotherbehavior,":increasecomparedtobaseline(basedonvisualinspectionofgraph),#:reductioncomparedto baseline.

Fig.3.PercentageoftimeRyan(twoupperpanels)andYasmine(twolowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypyandappropriatebehaviorduringbaseline, noncontingentmusic,anddifferentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)sessions.

5. Experiment3:addingpromptstoincreaseappropriatebehavior

Priorresearchandourpreviousexperimentssuggestthatinterventionsthatreducestereotypymayfailtoproduce desirableeffectsoncollateralbehavior.Forexample,Rappetal.(2013)havefoundthatwhileprovidingnoncontingent accesstoauditorystimulationmayreduceengagementinvocalstereotypy,theinterventionmayalsoincreaseuntargeted motorformsofstereotypyforsomeindividuals.In ourcurrentstudy,wealsoobservedthatreducingvocalandmotor

Fig.4.PercentageoftimeDavid(fourupperpanels),Ryan(fourmiddlepanels),andYasmine(twolowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypyand appropriatebehaviorduringandfollowingbaselineanddifferentialreinforcementofotherbehavior(DRO)sessions.

stereotypydoesnotnecessarilyproduceresponsereallocationtowardappropriatealternativebehavior(e.g.,Zoe,Morgan). Tothisend,oneofthesimplestinterventionstoincreasealternativebehavioristoprovidepromptingwhenthepersonisnot engagingintheappropriatebehavior(e.g.,Britton,Carr,Landaburu,&Romick,2002;Singh&Millichamp,1987).Moreover, someresearchershavefoundthatpromptingalonemayreduceengagementinmotorformsofstereotypy(Symons&Davis, 1994).Thepurposeofthethirdexperimentwastoexaminethedirectandcollateraleffectsofinterventionswithprompts. 5.1. Participantsandsettings

Zoe,Morgan,Jacob,Eric,Fred,andGregparticipatedinthethirdexperiment.ZoeandMorganwereincludedbecauseboth participantswerestillavailablefollowingExperiment1andlevelsofappropriatebehaviorremainedlowdespitereductions instereotypy.Thesettingoftheirinterventionremainedthesame.WeinvitedJacobtoparticipateinthestudybecausewe hadbeeninformedbyhiseducatorthathewasunabletoengageinindependenttasksunlesshewasprompted.Jacob completedasimpletaskoftransferringitemsfromonecontainertoanotherduringthesessions.Finally,ourresultsfrom previousstudiessuggestedthatnoncontingentmusicalonefailedtoincreasefunctionalplay,increasedmotorstereotypy,or bothforEric,Fred,andGreg(Lanovaz,Rapp,etal.,2012;Rappetal.,2013).Thesethreeparticipantshadaccessto age-appropriatetoysduringtheirsessions.Theparticipantswerefamiliarwiththetoys,hadthenecessaryskillstointeractwith them,butrarelydidsoindependently.

5.2. Procedures

Thedesign,procedures,andinterventionsremainedthesameasinExperiments1and2withtheinclusionofafewminor changes.BecauseJacobwasonlyavailableonceperweekandwehadtoconductmanysessionsinthesameday,hissessions lastedonly5minandwedidnotmeasurepost-interventioneffects.HisDRAconsistedofa continuousreinforcement schedule(i.e.,fixedratio1)eachtimehetransferredanitemfromonecontainertoanother.Wealsomadesomechangesto theDRAinterventionforGreg.Heonlyreceivedhisreinforcerifhewasengaginginfunctionalplaywhentheintervalended (andnotforthefirstoccurrencefollowingtheendoftheintervalasinatypicalintervalschedule)anditsdurationwasfixed. Thischangewastofacilitatethesubsequentimplementationbyhisparent.ForZoe,weonlyassessedDRAwithpromptingas DRAwastheinterventionthathadproducedthemostdesirableoutcomesonstereotypyinExperiment1.SimilarlyforEric and Fred, we focused exclusively on noncontingent music with prompting as previous studies had shown that the interventionfailedtoproducedesirablecollateraleffectsfortheseparticipants(Lanovaz,Rapp,etal.,2012;Rappetal.,2013). Finally,wecombinednoncontingentmusicwithDRAforGreginordertoexaminetheuniquecontributionofthelatter. Forallparticipants,weaddedapromptingprocedureacrossallconditions(i.e.,baseline,noncontingentmusic,andDRA). ForJacob,Eric,Fred,andGreg,thepromptingprocedureinvolvedprovidingaphysicalpromptevery15sifthechildwasnot engagingintheappropriatebehavior.ForMorgan,weimplementedaleast-to-mostpromptingproceduretoengagein on-taskbehaviorcontingentontheoccurrenceoftargeteddisruptivebehavior(i.e.,playingwithmaterials,standingup,and rockingthechair)becauseourobservationssuggestedthatthesebehaviorsinterferedwithtaskengagement.Duringthe least-to-mostpromptingsequence,theresearchassistantbeganwithaverbalprompt.Iftheparticipantdidnotcomplywith theverbalpromptwithin5s,theresearchassistantaddedagesturalprompt.IfMorganstilldidnotcomplywiththeverbal plusgesturalprompt,theresearchassistantsubsequentlyaddedaphysicalprompt.Finally,theresearchassistantsnoted thatZoeengagedinhigherlevelsofengagementwhenhereducatorplacedaniteminherhands.Thus,theprompting procedureinvolvedgivingheranitemthatprovidedsensorystimulationassoonasshehadnotmanipulatedanitemfor2s. 5.3. Resultsanddiscussion

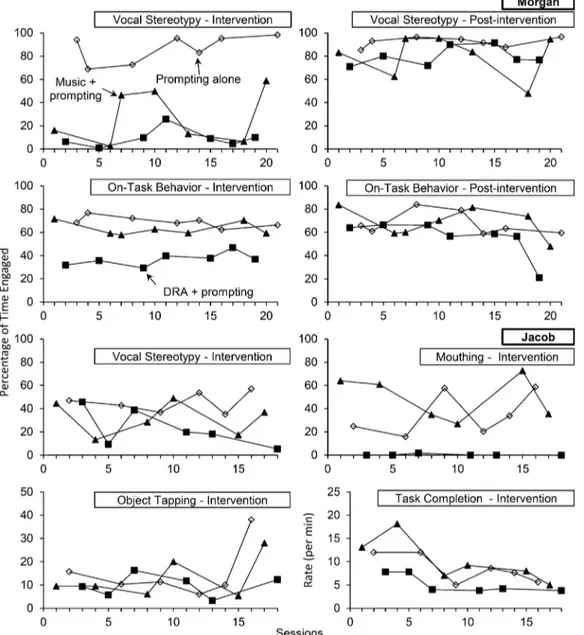

Table5displaysthemeansandrangesforeachparticipantacrossconditions.Fig.5showstheimmediate(upperfivepanels) andsubsequenteffects(lowerfivepanels)ofDRAforZoe.ResultssuggestthatcombiningDRAwithpromptingcontinuedto produceimmediatereductionsin vocalstereotypy,bodyrocking,and fingermoving,but alsomarginallyincreasedface touching.LevelsofobjectmanipulationremainedsimilaracrossthepromptingandDRAwithpromptingconditions,butwere considerablyhigher thanlevels observed in Experiment 1. Moreover, DRAwith prompting respectively decreasedand increasedsubsequentengagementinfingermovingandfacetouching.Fig.6showstheimmediateandsubsequentresultsof implementingpromptingwithnoncontingentmusicandDRAforMorgan(upperfourpanels)andJacob(lowerfourpanels). Comparedwithpromptingalone,DRAwithpromptingreducedimmediateandsubsequentengagementinvocalstereotypyfor Morgan,butalsoreducedimmediateengagementinon-taskbehavior.Theonlyconsistenteffectofnoncontingentmusicwith promptingwastoreduceimmediateengagementinvocalstereotypy,albeittoalesserextentthanDRA.ForJacob,combining DRAwith prompting reduced engagement in vocal stereotypy and mouthingas well as the rate of task completion. Noncontingentmusicalsoreducedvocalstereotypy,butmeanlevelsremainedhigherthanforDRA.

Fig.7showsthepercentageoftimeEric,Fred,andGregengagedinstereotypyandappropriatebehaviorduringthe interventionsthatinvolvedprompting.ForEric,noncontingentmusicwithpromptingreducedvocalstereotypy,produced noconsistentchangesinmouthing,andincreasedfunctionalplay. ForFred,noncontingentmusicwithpromptingonly producedreductionsinvocalstereotypy.ForGreg,DRAwithpromptingreducedengagementinvocalstereotypy,butthe additionofnoncontingentmusicproducedevenlargerreductions.Nevertheless,thesereductionsdidnotappeartoproduce

reallocationtowardfunctionalplay.Wedidnotobservesystematicpost-interventionchangesacrossconditionsforanyof thethreeparticipants(datanotdepicted).Theresultssuggestthatpromptingdidnotinterferewiththeeffectivenessofthe interventionsinreducingstereotypy.Furthermore,noncontingentmusicincreasedfunctionalplayinoneparticipantand didnotappeartointerferewithengagementinappropriatebehaviorfortheothers.

6. Experiment4:effectsofextendedexposure

Ourpreviousexperimentsindicatethatusingnoncontingentmusicaloneorincombinationwithpromptingmaybea suitablefirstinterventionforasequentialinterventionmodel.Inadditiontoreducingengagementinvocalstereotypy,the interventionneverincreasedmotorformsofstereotypy,norinterferedwithengagementinappropriatebehavior.Moreover, noncontingentmusicsometimesincreasedengagementinappropriatebehavior.Giventhatweassessedtheeffectsofmusic

Table5

MeansandrangesforeachparticipantacrossconditionsforExperiment3.

Intervention Post-intervention Participants Baseline Musica

DRA Baseline Musica

DRA Zoe Vocalstereotypy 97% 63%# 98% 88% (92–100%) (28–93%) (96–100%) (62–98%) Rocking 90% 34%# 90% 71% (77–98%) (1–80%) (84–96%) (23–97%) Fingerwiggling 65% 20%# 66% 43%# (51–81%) (1–59%) (39–80%) (2–72%) Facetouching 7% 12%" 7% 15%" (5–12%) (7–25%) (3–11%) (5–39%) Objectmanipulation 25% 25% 23% 29% (17–35%) (17–34%) (12–35%) (18–41%) Morgan Vocalstereotypy 87% 28%# 9%# 92% 80% 80%# (69–98%) (3–59%) (1–26%) (85–97%) (48–95%) (71–91%) On-taskbehavior 69% 63% 37%# 67% 68% 56%# (62–77%) (58–72%) (29–47%) (59–84%) (48–84%) (21–66%) Jacob Vocalstereotypy 45% 31%# 23%# (35–57%) (13–49%) (5–46%) – – – Mouthing 35% 49% 0%# (16–59%) (27–73%) (0–2%) Objecttapping 15% 13% 10% (6–38%) (5–28%) (3–16%) Taskrate(permin) 8 10 5#

(5–12) (5–18) (4–8) Eric Vocalstereotypy 10% 1%# – 17% 8% (0–17%) (0–4%) (4–40%) (3–17%) Mouthing 13% 7% 20% 12% – (0–72%) (0–28%) (0–40%) (0–50%) Functionalplay 21% 39%" 19% 22% (9–38%) (13–73%) (6–29%) (9–51%) Fred Vocalstereotypy 55% 21%# 41% 51% (9–84%) (5–62%) (22–54%) (15–76%) Objecttapping 15% 12% – 11% 12% – (4–21%) (11–17%) (2–17%) (6–25%) Functionalplay 23% 28% 26% 32% (16–36%) (14–51%) (16–40%) (16–44%) Greg Vocalstereotypy 47% 5%# 28%# 47% 49% 42% (28–65%) (1–11%) (14–46%) (31–59%) (40–65%) (25–53%) Functionalplay 33% 38% 49% 9% 13% 6% (10–66%) (30–52%) (30–77%) (0–26%) (2–61%) (1–11%) Notes:DRA:differentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior,":increasecomparedtobaseline(basedonvisualinspectionofmultielementgraph),#: reductioncomparedtobaseline.

onlyduringbrief10-minsessions,weexaminedwhetherthepositiveoutcomewouldpersistforsessionsoflongerduration toextendthepotentialutilityoftheresultsofthecurrentstudy.

6.1. Participantsandprocedures

WeinvitedEricandFredtoparticipateinthefourthexperiment.Ericparticipatedinthree90-minsessionsandFredin four50-to60-minsessions.SessiondurationswereshorterforFredbecauseheengagedinelopementwhenhestayedinthe sameroomforextendedperiodsoftime.Bothparticipantshadaccesstothesameage-appropriatetoysasduringExperiment 3andweprovidednosocialconsequencesforengaginginvocalstereotypyorfunctionalplay.Duringtheseperiods,the participantswerefreetoplaywiththetoysandmovearoundtheroom.Ericinitiallyparticipatedintwo90-minsessions

Fig.5.PercentageoftimeZoeengagedinvocalstereotypy,motorstereotypy,andobjectmanipulationduring(fiveupperpanels)andfollowing(fivelower panels)promptingaloneanddifferentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)withpromptingsessions.

duringwhichhispreferredsongplayedcontinuouslyinaloopandtheninone90-minsessionduringwhichthechildren’s songsvaried.Fredparticipatedinabriefreversal:thefirsttwosessionsinvolvedthesamepreferredsongplayinginaloop, thethirdsessiondidnotincludemusic,andthelastsessionreturnedtothesamepreferredsonginaloop.

6.2. Resultsanddiscussion

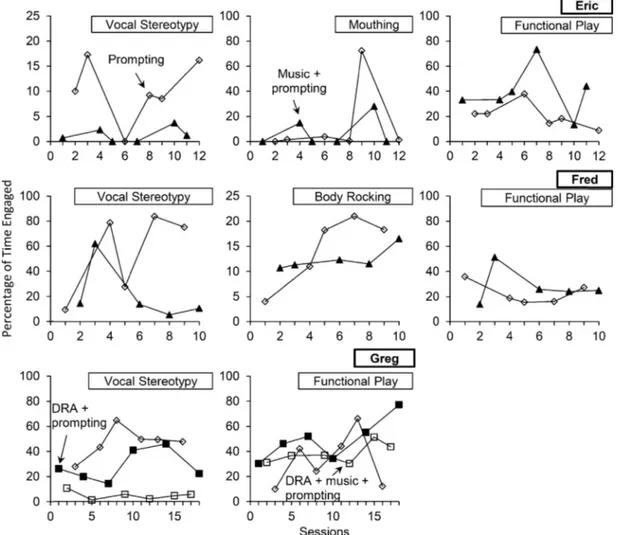

Fig.8presentsthepercentageoftimeEricandFredengagedinvocalstereotypyduring50-to90-minsessions.Thedata weredividedin10-minintervalstofacilitatecomparisonswiththeotherexperimentsandalsotoexaminetrendsoverthe extendedsessions.Eric(upperpanel)maintainedlowandstablelevelsofvocalstereotypy(M=10%)duringthefirst90-min sessionwiththesamesongplayinginaloop(i.e.,constantmusic),butlevelsincreasedfollowing30minintothesecond 90-minsession(M=33%).Whenweintroducedvariedmusic,engagementinvocalstereotypyreturnedtolowlevelsduringthe entire90-minsession(M=7%).ThefirstsessionforFred(lowerpanel)onlylasted50minbecausehemadeseveralattempts toleavetheroom.Levelsofvocalstereotypywhenhispreferredsongplayedcontinuouslyinaloopweregenerallylow,but showedaslightincreasingtrendacrossthelast30minofthesession(M=8%).Duringthesecondsession,Fredalsodisplayed generallylowlevelsofvocalstereotypy(M=12%).Thewithdrawalofmusicforanentire60-minsessionproducedincreases

Fig.6.PercentageoftimeandrateMorgan(fourupperpanels)andJacob(fourlowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypy,motorstereotypy,andappropriate behaviorduringandfollowingpromptingalone,noncontingentmusicwithprompting,anddifferentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)with promptingsessions.

inengagementinvocalstereotypy(M=63%)whencomparedtotheconstantmusicsessions.Thereintroductionofthe preferredsongforafinal60-minsessionclearlyreplicatedthereductionsinvocalstereotypy(M=8%)observedinthetwo initialsessions.Theresultssuggestthattheeffectsofmusicmaycontinueacrosslongsessiondurations,butthatitmaybe importanttovarythesongforsomeindividuals.

7. Generaldiscussion

Insum,thefirstexperimentindicatedthatnoncontingentmusicgenerallyproducedbetteroutcomesthanDRA.The subsequentimplementationofDROinthesecondexperimentreducedstereotypyintwoofthreeparticipantsforwhom otherinterventionsdidnot.Inthethirdexperiment,theadditionofpromptsdidnotinterferewiththereductionsinvocal stereotypy produced by theinterventions while maintainingmotor forms of stereotypy and appropriate behavior at desirablelevels.Finally,thefourthexperimentshowedthattheeffectsofnoncontingentmusicmaypersistduringsessions withextendeddurations.

Overall, at least one intervention reduced engagement in vocal stereotypy for 11 of 12 participants. Specifically, noncontingentmusicaloneorwithpromptsreducedimmediateengagementinvocalstereotypyin8of11participantswith whomtheinterventionwasimplemented.Whennoncontingentmusicreducedimmediateengagementinvocalstereotypy, we alsoobserved immediate increases in appropriate behavior in three participants, immediate reductions in motor stereotypyinoneparticipant,andsubsequentdecreasesinvocalstereotypyinoneparticipant.Incontrast,DRAaloneorin combination with promptsreduced vocal stereotypy in fourof nine participants.Furthermore, theintervention was associatedwithreductionsinmotorstereotypyintwoparticipants.Theinterventionalsoreducedappropriatebehaviorin two participantsfor whomthe intervention had reduced immediateengagement in vocalstereotypy and marginally increasedappropriatebehaviorinonlyoneparticipant.

Fig.7.PercentageoftimeEric(threeupperpanels)andFred(threemiddlepanels)engagedinstereotypyandfunctionalplayduringpromptingaloneand noncontingentmusicwithpromptingsessions.PercentageoftimeGreg(twolowerpanels)engagedinvocalstereotypyandfunctionalplayduring promptingalone,differentialreinforcementofalternativebehavior(DRA)withprompting,andDRAplusnoncontingentmusicwithpromptingsessions.

The mainimplication of theresultsis that noncontingentmusicmay bemoreeffective thanDRAtoreduce vocal stereotypy. Notably,noncontingentmusic reduced vocalstereotypyfor 73% of participantswhereasDRAreduced the behaviorfor45%ofparticipants,suggestingthatitmaybepreferabletobeginthesequentialinterventionmodelusing noncontingentmusic.Thecollateraleffectsofnoncontingentmusicwerealsoclinicallydesirable:theinterventionincreased appropriatebehaviorinthreeparticipants,neverinterferedwithappropriatebehaviorintheremainingparticipants,and never increasedimmediate or subsequent motor stereotypy. Noncontingent music alsoreduced vocal stereotypyfor sessionswithextendeddurations,butitwasnecessarytovarythesongforoneparticipant.Ourresultsalsosuggestthat practitioners shouldconsidersupplementing noncontingentmusicwithprompts,which mayhinderengagementwith motorformsofstereotypywhilestrengtheningorincreasingengagementinappropriatebehavior.

Whennoncontingentmusicfailstoreducestereotypy,DROappearstobeamoreadequatealternativethanDRAasit reducedstereotypyinalargerproportionofparticipants.Thatsaid,addingpromptsmayalsobeimportantforDROasthe interventiondidnotincreaseappropriatebehaviorifitwasnotalreadyoccurringathighlevelsduringbaselinesessions.For oneparticipant(Yasmine),DROincreasedengagementinvocalstereotypy.Herresultssuggestthatanotherintervention shouldbeplannedaspartofthesequentialinterventionmodelwhenbothpreviousinterventionsdonotproducethedesired outcomes.TheresearchliteraturesuggeststhatresponsecostmaybeasuitablecandidatetofollowDRO(Falcomataetal., 2004;Watkins&Rapp,2014),butstudiesshouldbeconductedtoconfirmthishypothesis.Ouranalysesthussuggestthata potentiallyefficientsequentialinterventionmodelwouldinvolvetheimplementationofnoncontingentmusicfirst,DRO second,andresponsecostlastifbothpreviousinterventionsfailedtoproducedesirableeffects.

Unexpectedly,DRAincreasedthetargetappropriatebehaviorforonlyoneofnineparticipants.Onepotentialexplanation isthattheschedulesofreinforcementwerenotdenseenoughtoincreasetheappropriatebehavior.Thatsaid,wedidnot observe more desirable outcomesin the participantswith denser schedules and any added benefitsof using denser scheduleswouldprobablyhavebeenoffsetbythechallengesassociatedwiththeirimplementationinappliedsettings. AnotherexplanationisthattheselectionoftheappropriatebehaviormayhavecontributedtohoweffectivetheDRAwasat strengtheningcollateralbehavior.Thatis,usingdifferentalternativebehaviormayhaveproduceddifferentresultsand shouldbeinvestigatedinthefuture.ThereductionsobservedinappropriatebehaviorduringDRAprovidefurthersupportfor researchsuggestingthatdenseschedulesusingediblesmaydisruptengagementinotherbehavior(Frank-Crawfordetal., 2012). Namely,thetimespentconsumingediblesmayconsiderablyreducetheamountoftimeavailable toengagein appropriatebehavior,whichwouldexplaintheresults.

Altogether,thefourexperimentsextendtheresearchliteratureonthetreatmentofvocalstereotypyinseveralways.First, ourstudyisthefirsttosystematicallycomparetheeffectsofnoncontingentmusicandDRAonvocalstereotypy,motor stereotypy,andappropriatebehavior.Comparingtreatmentstogetherisimportantaspractitionersrelyontheseresults whenselectingbehavioralinterventionstoimplementinappliedsettings(Shabani&Lam,2013).Second,ourresultsextend previous research by showingthat noncontingentmusic never interfered withongoing appropriate behavior. On the contrary,noncontingentmusicwasevenassociatedwithincreasesinappropriatebehaviorforsomeparticipants,afinding thatisconsistentwithatleastonepriorstudy(Burlesonetal.,1989).Hence,ourresultsminimizeaclinicalconcernthat

Fig.8.PercentageoftimeEric(upperpanel)andFred(lowerpanel)engagedinvocalstereotypyacross10-minintervalsduring50-to90-minsessionswith nomusic,constantmusic,andvariedmusic.Thearrowsidentifythefirst10-minintervalforeachextendedsession.

noncontingentmusicmayinterferewithotherimportantbehavior(Lanovaz&Sladeczek,2012).Theobservedchangesin vocalstereotypyarealsoconsistentwiththose ofpriorstudieswhich showedthat musicreducedengagementinthe behavior(e.g.,Lanovaz&Sladeczek,2011;Sayloretal.,2012).

Third,ourresultsreplicatethefindingsofotherstudiesthathaveusedDROandhaveshownthattheschedulemaybe thinnedovertimetomakeiteasiertoimplementinappliedsettings(Rozenblatetal.,2009;Tayloretal.,2005).Fourth,the thirdexperimentindicatesthataddingpromptsdoesnotinterferewiththeeffectivenessofotherbehavioralinterventions andmayevenenhancetheireffects.Forexample,wehadshowninapreviousstudythatnoncontingentmusicincreased motorstereotypyforEricandGreg(Rappetal.,2013).Bycontrast,suchincreasesinmotorstereotypyinthepresenceof promptswerenotobservedinthisstudy.Finally,thefourthexperimentreplicatedandextendedthestudywithlonger sessiondurationsconductedbyLindbergetal.(2003)usingnoncontingentreinforcementwithtangibleitems.Weshowed thattheeffectsofnoncontingentmusicmaycontinueduringextendedapplicationandthatvaryingmusicmaybeeffective whenapreferredsongnolongerreducesengagementinvocalstereotypy.

Somelimitationsshouldbeconsideredwheninterpretingtheresultsofthecurrentstudy.Theresultsofthecomparison betweennoncontingentmusicandDRAislimitedinsofaraswechosetouseediblesratherthanmusicasreinforcersduring DRAforallbutoneparticipantbecausetheformeraremorepracticaltodeliverinappliedsettings.Thedifferentialeffects mayhavethusbeentheresultsofthedifferentstimuli.TheclinicalrelevanceofusingDRAwithmusicwouldbelimitedgiven the complexity of its implementation. We thus preferred comparing two interventions which could be realistically implementedbyeducatorsandparentsinappliedsettings.Similarly,weselectedthedensestschedulesofreinforcement thatcouldbepracticallyappliedintheparticipants’environments.Selectingdenserschedulesmayhaveproducedmore desirableeffects,butwouldhavebeenchallengingtoimplementforcaregivers.Inthethirdexperiment,wedidnotconducta no-promptingbaseline,whichlimited theanalysisoftheuniquecontributionofprompting.Althougha comparisonof resultsacrossexperimentsandstudiessuggestthataddingpromptshadbeneficialeffects,thelackofanexperimentaldesign precludesdefiniteconclusions.Tominimizeconfoundingeffectsassociatedwithwearingheadphones,weplayedthemusic throughexternalspeakers,whichmaybedisruptivetoothers.Inclinicalpractice,wewouldrecommendthattheindividual wearsheadphonesinstead(Sayloretal.,2012).

Futureresearchshouldreplicateourstudybyevaluatingtheeffectsoftheproposedsequentialinterventionmodelwitha groupofparticipants.Examiningtheuniquecontributionofprompting onstereotypy andappropriate behaviorwhen noncontingentmusicorDROproducesundesirablecollateraleffectsmayalsoextendresearchwhilepotentiallyimproving treatment.Researchersshouldalsoconsiderconductingstudiesinwhicheducatorsandcaregiversapplytheproceduresand measuringsocialvalidity. Largerscale studiescomparing thecosteffectiveness aswellastheeffects ofinterventions designedtoreducevocalstereotypywhenappliedbyindividualswhoarenottrainedinbehavioranalysismayalsobecrucial inthelongterm.Intheend,programsthatfacilitatetheselectionandimplementationofinterventionsbypractitionerswith differenttrainingbackgroundsmayproducethelargestimpactonthetreatmentstereotypyinindividualswithautismand otherdevelopmentaldisabilities.

Acknowledgments

ThestudywassupportedinpartbyanexperimentationgrantfromtheOfficedespersonneshandicape´esduQue´bec (#2361-09-51).WethanktheCentredere´adaptationdel’OuestdeMontre´alfortheircollaborationaswellasJulieDuquette, FannyJuneauandCyrielL’Hommefortheirassistancewithconductingthestudy.

References

Ahearn,W.H.,Clark,K.M.,MacDonald,R.P.,&Chung,B.I.(2007).Assessingandtreatingvocalstereotypyinchildrenwithautism.JournalofAppliedBehavior Analysis,40,263–275.

Britton,L.N.,Carr,J.E.,Landaburu,H.J.,&Romick,K.S.(2002).Theefficacyofnoncontingentreinforcementastreatmentforautomaticallyreinforcedstereotypy. BehavioralInterventions,17,93–103.

Burleson,S.J.,Center,D.B.,&Reeves,H.(1989).Theeffectofbackgroundmusicontaskperformanceinpsychoticchildren.JournalofMusicTherapy,26,198–205.

Carroll,R.A.,&Kodak,T.K.(inpress).Anevaluationofinterruptedanduninterruptedmeasurementofvocalstereotypyonperceivedtreatmentoutcomes.Journal ofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis.(inpress).

Cassella,M.D.,Sidener,T.M.,Sidener,D.W.,&Progar,P.R.(2011).Responseinterruptionandredirectionforvocalstereotypyinchildrenwithautism:A systematicreplication.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,44,169–173.

DiGennaroReed,F.D.,Hirst,J.M.,&Hyman,S.R.(2012).Assessmentandtreatmentofstereotypicbehaviorinchildrenwithautismandotherdevelopmental disabilities:Athirtyyearreview.ResearchinAutismSpectrumDisorders,6,422–430.

Falcomata,T.S.,Roane,H.S.,Hovanetz,A.N.,Kettering,T.L.,&Keeney,K.M.(2004).Anevaluationofresponsecostinthetreatmentofinappropriatevocalizations maintainedbyautomaticreinforcement.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,37,83–87.

Fisher,W.,Piazza,C.C.,Bowman,L.G.,Hagopian,L.P.,Owens,J.C.,&Slevin,I.(1992).Acomparisonoftwoapproachesforidentifyingreinforcersforpersonswith severeandprofounddisabilities.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,25,491–498.

Frank-Crawford,M.A.,Borrero,J.C.,Nguyen,L.,Leon-Enriquez,Y.,Carreau-Webster,A.B.,&DeLeon,I.G.(2012).Disruptiveeffectsofcontingentfoodon high-probabilitybehavior.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,45,143–148.

Horrocks,E.,&Higbee,T.S.(2008).Anevaluationofastimuluspreferenceassessmentofauditorystimuliforadolescentswithdevelopmentaldisabilities.Research inDevelopmentalDisabilities,29,11–20.

Lanovaz,M.J.,Rapp,J.T.,&Ferguson,S.(2012a).Theutilityofassessingmusicalpreferencebeforeimplementationofnoncontingentmusictoreducevocal stereotypy.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,45,845–851.

Lanovaz,M.J.,Rapp,J.T.,&Ferguson,S.(2013a).Assessmentandtreatmentofvocalstereotypyassociatedwithtelevision:Apilotstudy.JournalofAppliedBehavior Analysis,42,544–548.

Lanovaz,M.J.,Robertson,K.,Soerono,K.,&Watkins,N.(2013).Effectsofreducingstereotypyonotherbehaviors:Asystematicreview.ResearchinAutismSpectrum Disorders,7,1234–1243.

Lanovaz,M.J.,&Sladeczek,I.E.(2011).Vocalstereotypyinchildrenwithautism:Structuralcharacteristics,variability,andeffectsofauditorystimulation. ResearchinAutismSpectrumDisorders,5,1159–1168.

Lanovaz,M.J.,&Sladeczek,I.E.(2012).Vocalstereotypyinchildrenwithautismspectrumdisorders:Areviewofbehavioralinterventions.BehaviorModification, 36,146–164.

Lanovaz,M.J.,Sladeczek,I.E.,&Rapp,J.T.(2012).Effectsofnoncontingentmusiconvocalstereotypyandtoymanipulationinchildrenwithautismspectrum disorders.BehavioralInterventions,27,207–223.

Lindberg,J.S.,Iwata,B.A.,Roscoe,E.M.,Worsdell,A.S.,&Hanley,G.P.(2003).Treatmentefficacyofnoncontingentreinforcementduringbriefandextended application.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,36,1–19.

Love,J.J.,Miguel,C.F.,Fernand,J.K.,&LaBrie,J.K.(2012).Theeffectsofmatchedstimulationandresponseinterruptionandredirectiononvocalstereotypy. JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,45,549–564.

MacDonald,R.,Green,G.,Mansfield,R.,Geckeler,A.,Gardenier,N.,Anderson,J.,etal.(2007).Stereotypyinyoungchildrenwithautismandtypicallydeveloping children.ResearchinDevelopmentalDisabilities,28,266–277.

Matson,J.L.,Dempsey,T.,&Fodstad,J.C.(2009).Stereotypiesandrepetitive/restrictivebehavioursininfantswithautismandpervasivedevelopmentaldisorder. DevelopmentalNeurorehabilitation,12,122–127.

Mayes,S.D.,&Calhoun,S.L.(2011).ImpactofIQ,age,SES,gender,andraceonautisticsymptoms.ResearchinAutismSpectrumDisorders,5,749–757.

Querim,A.C.,Iwata,B.A.,Roscoe,E.M.,Schlichenmeyer,K.J.,Ortega,J.V.,&Hurl,K.E.(2013).Functionalanalysisscreeningforproblembehaviormaintainedby automaticreinforcement.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,46,47–60.

Rapp,J.T.(2005).Someeffectsofaudioandvisualstimulationonmultipleformsofstereotypy.BehavioralInterventions,20,255–272.

Rapp,J.T.,Swanson,G.,Sheridan,S.,Enloe,K.,Maltese,D., Sennott,L.,etal.(2013).Immediateandsubsequenteffectsofmatchedandunmatchedstimulion targetedvocalstereotypyanduntargetedmotorstereotypy.BehaviorModification,37,543–567.

Rapp,J.T.,&Vollmer,T.R.(2005).StereotypyI:Areviewofbehavioralassessmentandtreatment.ResearchinDevelopmentalDisabilities,26,527–547.

Rozenblat,E.,Brown,J.L.,Brown,A.K.,Reeve,S.A.,&Reeve,K.F.(2009).EffectsofadjustingDROschedulesonthereductionofstereotypicvocalizationsin childrenwithautism.BehavioralInterventions,24,1–15.

Saylor,S.,Sidener,T.M.,Reeve,S.A.,Fetherston,A.,&Progar,P.R.(2012).Effectsofthreetypesofnoncontingentauditorystimulationonvocalstereotypyin childrenwithautism.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,45,185–190.

Schumacher,B.I.,&Rapp,J.T.(2011).Evaluationoftheimmediateandsubsequenteffectsofresponseinterruptionandredirectiononvocalstereotypy.Journalof AppliedBehaviorAnalysis,44,681–685.

Shabani,D.B.,&Lam,W.Y.(2013).Areviewofcomparisonstudiesinappliedbehavioranalysis.BehavioralInterventions,28,158–183.

Singh,N.N.,&Millichamp,C.J.(1987).Independentandsocialplayamongprofoundlymentallyretardedadults:Training,maintenance,generalization,and long-termfollow-up.JournalofAppliedBehaviorAnalysis,20,23–34.

Symons,F.,&Davis,M.(1994).Instructionalconditionsandstereotypedbehavior:Thefunctionofprompts.JournalofBehaviorTherapyandExperimental Psychiatry,25,317–324.

Taylor,B.A.,Hoch,H.,&Weissman,M.(2005).Theanalysisandtreatmentofvocalstereotypyinachildwithautism.BehavioralInterventions,20,239–253.

Watkins,N.,&Rapp,J.T.(2014).Environmentalenrichmentandresponsecost:Immediateandsubsequenteffectsonstereotypy.JournalofAppliedBehavior Analysishttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jaba.97.(advancedonlinepublication)