Economic Integration of Immigrants to Canada

And Foreign Credential Recognition

Magali Girard Department of Sociology McGill University, Montréal

October 2010

A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

iii ABSTRACT

The lack of foreign credential recognition by Canadian employers and professional associations is often cited as one of the explanations for the increasing earnings gap between Canadian workers and immigrant workers. The main objective of my dissertation is to look at different aspects of economic integration of immigrants to Canada, and more specifically at issues related to credential recognition.

The objective of the first analysis is to examine the extent to which, after arrival, immigrants find jobs in the same occupations in which they were employed in their home countries. I also examine the effect on earnings of a match between the pre- and post-immigration occupations. Our results suggest that most recent immigrants move into a new occupation when they arrive in Canada and that those whose pre- and

post-immigration occupations match tend to earn more.

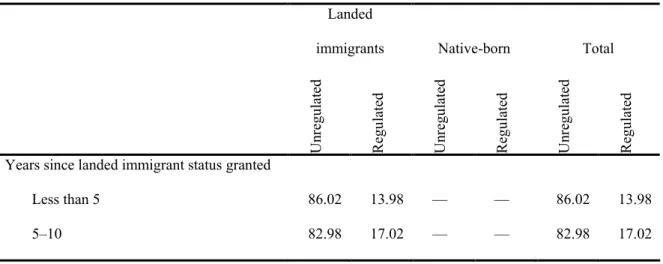

In the second analysis, I determine how many immigrants work in regulated and unregulated occupations and look at how education is associated with the likelihood of working in a regulated occupation. In aggregate, immigrants are slightly less likely to work in a regulated occupation. Immigrants educated in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean prove to be much less likely to secure access to a regulated occupation than either the native-born or other immigrants.

iv

The objective of the third analysis is to understand the transition between immigrants’ premigration education and their educational trajectories once in Canada, and the return on investment in postmigration education in terms of employment status and earnings. A third of new immigrants with postsecondary training pursue their education during their early years in Canada. Those who enrol do not see an immediate benefit in terms of their earnings and employment status.

In the last chapter, I examine foreign credential recognition processes in Canada and recent public investments to address this issue. Gaining foreign credential recognition from a regulatory body is not usually a matter of simply submitting transcripts; there are often examinations, Canadian work experience requirements, and language tests. Most investments related to foreign credential recognition in the past 5 to 10 years use the Web to provide information to prospective immigrants and to make self-assessment tools available.

v RÉSUMÉ

Le manque de reconnaissance des titres de compétences acquis à l’étranger est l’une des causes souvent citées pour expliquer l’augmentation de la disparité salariale entre immigrants et non-immigrants au Canada. Le principal objectif de ma thèse est d'examiner différents aspects de l'intégration économique des immigrants au Canada, et plus particulièrement ceux liés à la reconnaissance des titres de compétences étrangers.

Le but de la première étude est d’analyser le lien entre le domaine de l’emploi principal occupé par les immigrants avant leur arrivée et les emplois qu’ils ont occupés en début d’établissement, ainsi que l’effet net d’une adéquation des emplois sur le revenu des immigrants récents. Les résultats suggèrent que la plupart de ces immigrants ne se trouvent pas un emploi dans leur domaine; par ailleurs, ceux qui y parviennent ont un salaire plus élevé.

Dans la deuxième analyse, je détermine combien d’immigrants travaillent dans des professions réglementées et non réglementées. J’examine comment l'éducation est associée à la probabilité de travailler dans une profession réglementée et, dans l'ensemble, les immigrants sont un peu moins susceptibles de travailler dans de telles professions. Les immigrants formés en Asie, en Amérique latine et dans les Caraïbes ont beaucoup moins de chances d’occuper une profession réglementée que les autres immigrants et les non-immigrants.

vi

L'objectif de la troisième analyse est de comprendre la transition entre l'éducation pre-migratoire et les trajectoires d’éducation au Canada, et les effets de l’investissement en éducation post-migratoire sur l’employabilité et le revenu. Un tiers des nouveaux immigrants ayant une formation postsecondaire poursuivent leurs études pendant leurs premières années au Canada. Ceux qui s'inscrivent à un programme de formation ne voient pas un bénéfice immédiat sur leur revenu et les chances d’être en emploi.

Dans le dernier chapitre, j’examine les étapes que les immigrants doivent prendre afin de faire reconnaître leurs diplômes étrangers et les récents investissements publics mis de l’avant pour les aider. Afin d’obtenir la reconnaissance de diplômes acquis à l’étranger, il ne suffit généralement pas de présenter les relevés de notes; il y a souvent des examens et des tests de langue à passer, ainsi que des stages à faire. La plupart des investissements liés à la reconnaissance des titres de compétences étrangers depuis les 5 à 10 dernières années utilisent Internet pour fournir des informations aux immigrants potentiels et des outils d'auto-évaluation des compétences.

vii TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT... iii RÉSUMÉ ...v CONTRIBUTION OF AUTHORS...xi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... xiii INTRODUCTION ...1 CHAPTER 1. Economic Integration of New Immigrants: Match between Main Fields of Employment before and After Immigration to Quebec ...13

Hypotheses, Data and Method ...18

Results ...21

Time Spent Finding Work in Field...24

Factors Influencing Match Between Main Fields of Employment Before and After Immigration to Quebec...32

Occupational Match and Weekly Earnings ...38

Conclusion...41

References ...43

viii

2. Working In a Regulated Occupation in Canada: An Immigrant–Native-Born

Comparison ...51

Research Question and Hypotheses ...56

Data and Analysis ...57

Results ...59

Discussion ...77

Conclusion...78

References ...81

Appendix: List of Regulated Occupations in Canada, By Province ...86

LINKING SECTION ...89

3. Match Between Pre- and Postmigration Education among New Immigrants: Determinants and Payoffs ...91

Literature Review...91

Research Question and Hypotheses ...97

Data ...99

Method ...102

Results ...103

Descriptive Results...103

Determinants of Enrolments...108

Returns to Postmigration Education...111

References ...121

ix

4. How Immigrants Obtain Recognition of Their Foreign Credentials and What

Governments and Regulatory Bodies Do to Help...127

Obtaining Recognition of a Foreign Certificate, Diploma, or Degree ...129

Government and Regulatory Body Initiatives...135

Providing Information and Self-Assessment Tools Through the Web ....136

Bridging Programs and Mentorship Programs...138

Subsidized Work Experience and Employment Assistance Services ...139

Government Legislation and Agreements...141

Conclusion...143 References ...146 CONCLUSION...153 Summary of Findings...154 Discussion ...157 Future Research...158 REFERENCES ...161

xi

CONTRIBUTION OF AUTHORS

Chapter 1 of this dissertation was coauthored with Michael Smith and Jean Renaud and published in the Canadian Journal of Sociology (2008, vol. 33, no. 4) under the title “Intégration économique des nouveaux immigrants: adéquation entre l’emploi occupé avant l’arrivée au Québec et les emplois occupés depuis l’immigration.” As first author, I formulated the idea for the analysis, conducted the analysis, and wrote the chapter myself. Professor Smith assisted in determining the structure of the paper and provided invaluable comments and guidance throughout the writing process. Professor Renaud helped with the methodology and gave me a better understanding of the data structure.

Chapter 2 was coauthored with Michael Smith and has been submitted to the Journal of International Migration and Integration. As for Chapter 1, I formulated the idea for the analysis, conducted the analysis, and wrote the chapter myself. Professor Smith assisted in determining the structure of the paper and provided invaluable comments and guidance throughout the writing process.

xiii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My friend Hanna jokes that submitting a doctoral dissertation is almost like giving birth, the main difference being that morning sickness doesn’t happen in the first

trimester, but rather at the end of the journey. Being both at the end of my PhD program and a month away from giving birth to my second child, I must admit the analogy is not bad. There are a number of people who have made my stay at McGill enjoyable and helped reduce the minor complaints of dissertation writing.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Michael Smith for responding to my

questions and queries so promptly. His availability and sound advice were invaluable to the development, improvement, and outcome of this research project. I am also grateful to Amélie Quesnel-Vallée and Jean Renaud for helping with the methodology in chapters 1 and 3.

A big thank you to Karin Montin for her excellent work in editing my dissertation and Yolande Lemay for editing the French version of the first chapter, which was

published in the Canadian Journal of Sociology.

Thanks to the thousands of respondents to the surveys used in this dissertation. By patiently answering Statistics Canada’s questions, they enable us academics to conduct research that will potentially have some impact on social policy and thus immigrants’ lives.

xiv

I have been very fortunate to receive financial support from the Fonds de recherche sur la société et la culture, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Quebec Inter-University Centre for Social Statistics. My thanks also go to Statistics Canada, for giving me access to their data through the Québec

Inter-University Centre for Social Statistics.

Last, I would like to express my gratitude to my family: my partner, Pierre-André, for his constant support and for taking our son to Mexico for a week so I could finish writing and submit on time; my son Léo, with whom I have so much fun, for making me forget about my dissertation for a little while every day; and baby no. 2, who has been patiently waiting in the comfort of the womb until this dissertation is submitted.

INTRODUCTION

New immigrants to Canada have higher levels of education than Canadian-born workers and previous cohorts of immigrants. Over 50% of immigrants who arrived

between 2001 and 2006 held a university degree, as opposed to only 20% of the Canadian-born population and 28% of immigrants who arrived before 2001 (Statistics Canada, 2008). The high proportion of skilled immigrants is a direct consequence of the point system designed for that purpose, which applies to economic immigrants, the largest category. About 60% of new immigrants enter Canada through the economic category (skilled workers and business immigrants), as opposed to the family reunification and refugee categories (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2010).

Principal applicants in the skilled workers category are judged on the point system, which was introduced in 1967 and has been modified a number of times. Currently, to be considered for an interview, principal applicants in the economic category must get at least 67 out of 100 points. The point system allows up to 25 points for education and up to 21 for work experience. It also assigns 10 points to candidates with prearranged employment. Since 1991, Quebec has selected its own skilled workers. Here, the point system is similar to the one used in the rest of Canada, but allocates more points for the ability to understand and speak French.

After a public consultation process in 1993, the federal government changed its point system to put less emphasis on intended occupation and more on education,

2

experience, and language skills. “The underlying rationale was that at a time of rapid structural change in the Canadian economy it was better to focus on generic skills” (Birrell & McIsaac, 2006, p. 103). The federal point system does not reward skills in demand in Canada, but Québec does give additional points, based on a list of areas of training (Ministère de l’immigration et des communautés culturelles, 2010).

There is now a substantial literature documenting the deterioration of immigrants’ situation in the Canadian job market over the past two decades (Li, 2000; Reitz, 2001; Richmond, 1992), and their disadvantage on the labour market compared to

nonimmigrants, despite higher levels of education (Li, 2001; Alboim, Finnie, & Meng, 2005; Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001). They earn less than Canadian-born workers (Boudarbat & Boulet, 2007; Picot, 2004; Alboim et al., 2005; Li, 2000), and are more likely to be unemployed (Thomas & Rappak, 1998).

Most social scientists agree on the possible causes of the deterioration of labour market outcomes of recent immigrants to Canada, such as human capital characteristics, discrimination, and macroeconomic factors. Human capital theorists see education expenditure, work experience, computer training, etc., as an investment in human capital (Becker, 1975). Those skills and work capacities increase productivity and that

productivity is likely to increase the pay someone can command in the labour market. The return on investment can be defined as the gain in wages resulting from investment in human capital. Studies on immigration often use human capital theory to study the performance of immigrants on the labour market. The most commonly used measures of human capital, when it comes to immigrants, include education level, place, and field, work experience, and official language proficiency.

3

It appears that one of the causes of immigrants’ disadvantage is that a degree earned abroad has less value on the labour market, so that immigrants generally have a lower return on investment than nonimmigrants. Premigration work experience results in negligible gains in earnings (Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001; Alboim et al., 2005).

Regardless of ethnic background and sex, annual earnings are higher when training and experience is gained in Canada. Visible-minority immigrants, and particularly women, are the most disadvantaged in terms of annual earnings (Li, 2001; Alboim et al., 2005; Anisef, Sweet, & Frempong, 2003).

Racial and ethnic discrimination are often cited as an explanation for the disparities and are said to have a major negative impact on the position of immigrants (and visible minorities generally) on the labour market. Allport (1979) distinguishes between prejudices and discrimination: prejudices are preconceived ideas; discrimination is a behaviour resulting from prejudice. One of the most persistent prejudices concerning the immigrant population in Canada is the negative impact of immigration on employment and wages (Kelley & Trebilcock, 1998). Another important bias regards training and work experience for newcomers. Although Canadian employers and the public are in favour of immigration, many remain sceptical about the skills of immigrants (Reitz, 2005).

Racial and ethnic discrimination are both cause and consequence of the position of immigrants on the labour market. Reitz (2005) notes that with the deterioration of the position of immigrants on the labour market, the public perception of immigrants as social problems can be expected to grow. Mensah (2002) provides a diagram of the vicious cycle of ethnic and racial discrimination: stereotypes and prejudices lead to discrimination, which leads to socioeconomic disadvantage, which leads the general population to believe

4

that the target group is inferior and responsible for their own plight, which in turn leads to stereotypes and prejudices.

Changes in Canadian immigration policy in the late 1960s (when the point system was introduced to select principal applicants in the skilled workers category) have led to a significant decrease in the number of immigrants from Western Europe and an increase in the number of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Picot, 2004; Pendakur, 2000), thus increasing the number of visible minority members in Canada (Mensah, 2002). Picot (2004) suggests that increasing the number of visible minority members among new arrivals may have led to an increase in racial and ethnic discrimination in the workplace.

Some scholars argue that the economic situation of immigrants shortly after their arrival (Picot, 2004) and institutional changes on the labour market (Reitz, 2005;

Pendakur, 2000) have a long-term impact on the position of immigrants on the labour market. The educational levels of Canadians have increased, along with women’s

participation rate in the labour market, thereby increasing competition in the labour market for new immigrants (Reitz, 1998; Picot, 2004). Additionally, when the local economy is in bad shape, tensions between immigrants and nonimmigrants may increase, because of increased competition for fewer available jobs, which can lead to greater discrimination against immigrants.

Finally, poor knowledge of the rules of the labour market of the host country can have a negative impact on the ability to find employment. Even skilled immigrants seem to have difficulty in accessing skilled jobs (those requiring a university degree), in part as a result of changes in recruitment practices and hiring (Reitz, 2005). These rules, concerning the format of a resumé, thank-you letters sent after an interview, job interviews, and so on,

5

are one of the significant barriers to the integration of immigrants in the labour market (Bauder, 2005). Also, with lack of adequate information about wages and working conditions, immigrants may have unrealistic expectations about their careers, or accept employment for which they are overqualified (Bonacich, 1972).

Canadian employers’ and regulatory bodies’ lack of recognition of credentials earned abroad is one of the reasons often advanced by immigrants and government

authorities alike to explain the wage gap between immigrants and Canadian-born workers. Foreign credential recognition is the process by which internationally-trained individuals, most likely immigrants, get their credentials (education and work experience) recognized by employers, regulatory bodies, government agencies or postsecondary institutions. As a result of poor recognition of foreign credentials, immigrants trained outside Canada may not secure employment in their fields and that requires their skill levels.

Whereas some link the failure to recognize credentials acquired overseas in terms of human capital theory, others see it as an expression of discrimination. A foreign degree may have the same name as a Canadian degree, but be deemed inferior: in this case human capital is considered to be less than perfect. Sweetman (2003) looked at the effect of the quality of education in each immigrant’s source country, measured by standardized international test scores in math and science, on the return on education of immigrants to Canada. “Those from source countries with lower quality average educational test scores receive a lower average return for their years of schooling” (Sweetman, 2003, p. 6). De Silva (1997) believes that what is often taken for discrimination in the labour market is actually a lower quality of education acquired abroad. The author comes to this conclusion after observing that skin colour differences are associated with smaller earning differences

6

between people who received a similar quality education (Canadian-born visible minority members and Canadian-born whites) than between immigrants and native-born Canadians.

The second issue is related to statistical discrimination by employers. The issue is that there is a proportion, possibly small, of immigrants whose education did not translated into skills comparable to those receiving equivalent education in Canada. Partly owing to their lack of familiarity with foreign qualifications, employers tend to generalize the qualifications of those immigrants to all immigrants, deeming their work experience and educational background to be inferior. It has been estimated that Canada loses somewhere between $2 and $5.9 billion a year because immigrants’ skills are underutilized (Reitz, 2001; Watt & Bloom, 2001). “Although the problem with recognition of immigrants’ foreign qualifications generally has not been articulated as one of racial discrimination, racial discrimination definitely is one cause of skill underutilization” (Reitz, 2005, p. 12). According to Goldberg (2007), the discourse that focuses on immigrant professionals as “foreign-trained” devalues their skills and experience. Unfamiliarity with foreign credentials, which are seen as not up to Canadian standards, serves to bolster racism against internationally trained immigrants.

The objective of my dissertation is to look at different aspects of economic integration of immigrants to Canada, and more specifically at issues related to credential recognition.

Surveys show that the issue of foreign credential recognition is a major barrier to the successful economic integration of immigrants to Canada. The Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada shows that 62% of newly arrived economic immigrants between 25 and 44 years of age encounter problems in the job-finding process during their first four

7

years in Canada (Schellenberg & Maheux, 2007). Of all the main obstacles, poor foreign credential recognition and the lack of Canadian work experience were among the problems most often cited by immigrants: 37% mentioned the lack of recognition of their foreign work experience and 35% mentioned the lack of recognition of their foreign-acquired skills.

Employers seem ill equipped to properly assess skills acquired abroad. A survey conducted by the Canadian Labour and Business Centre (2001) showed that business managers find language, along with problems assessing foreign training and work experience, to be the key hurdles encountered when trying to hire new immigrants. The underutilization of immigrants’ skills shows just how unprepared employers are to assess the qualifications of potential employees (Li, 2000; Reitz, 2001).

Foreign credential recognition depends on whether the occupation is regulated in the host country or not. About 20% of Canadian jobs are in regulated occupations (Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials, 2010). An occupation is regulated if a licence from a professional association or a government agency is required to practise or, in some cases, to have a reserved title. In Canada, licensure is a provincial responsibility; it is provincial associations or agencies that grant licenses. Examples of regulated occupations are doctors, nurses, engineers, and some trades. In general, regulated occupations are likely to be distinguished by the high level of education and/or training they require. This is one of the reasons why, on average, they might be expected to provide higher pay. The other reason is that the regulations governing access tend to restrict

8

occupations would tend to lower the overall earnings of immigrants and, in particular, the return on their education.

The literature on foreign credential recognition has focussed mainly on earnings of immigrants and the return on investment of foreign education and foreign work experience (Li, 2001; Anisef et al., 2003; Picot, 2004; Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001; Wanner & Ambrose, 2003). Some research has been conducted on specific regulated occupations, such as engineering (Boyd & Thomas, 2002; Girard & Bauder, 2007), and nursing and medicine (Hawthorne, 2006; Boyd & Schellenberg, 2007). Also, policy papers written a few years ago have documented “who does what” in foreign credential recognition (Fernandez, 2008; Owen, 2007; Hawthorne, 2002; Construction Sector Council, 2005). Even if foreign credential recognition is a major policy concern, many aspects of the issue remain unexplored.

With my dissertation, I contribute to a better understanding of the issue of foreign credential recognition in Canada by looking at the link between foreign credentials (education and work experience) and those earned in Canada, by studying regulated occupations and by researching foreign credential processes taken by immigrants and recent initiatives developed by governments and regulatory bodies to help immigrants have their credentials recognized.

First, few studies have looked at the link between premigration and postmigration work experience. Yet, knowing whether immigrants work in the same field as in their homelands is one way of determining if their premigration work experience is recognized in the same way as locally acquired work experience. It can also be supposed that

9

immigrants working in their fields see their income increase because their work experience and skills are not underutilized.

Second, no studies have determined the number of immigrants working in a regulated occupation. Yet, access to regulated occupation by immigrants is seen as a key element in addressing the issue of foreign credential recognition. By selecting 15

educational programs that usually lead to a regulated occupation, a recent Statistics Canada publication shows that, relatively speaking, more immigrants than native-born Canadians are trained for regulated occupations, but fewer actually work in them (Zietsma, 2010). A major contribution to the literature and toward a better understanding of the access of immigrants to regulated occupations would be to determine the proportion of immigrants who work in regulated occupations. Given that the regulation of occupations is a provincial jurisdiction and that the list of regulated occupations varies significantly by province, this can be a challenge. Also, the existing literature suggests that immigrants are disadvantaged in their inability to gain access to regulated occupations to the extent that their high level of education warrants. Once the number of immigrants and nonimmigrants working in regulated occupations is determined, we can assess the scope of the association between education (level, field, and place) and working in regulated occupations.

Third, most studies on postmigration investment in education use data from the U.S. (Borjas, 1982; Khan, 1997; Bratsberg & Ragan, 2002), Australia (Chiswick & Miller, 1994), the Netherlands (Van Tubergen & Van de Werfhorst, 2007), Israel (Friedberg, 2000), and Spain (Sanroma, Ramos, & Simon, 2008). Few studies have examined the association between pre- and postmigration education, and, except for Anisef, Sweet and Adamuti-Trache (2008), none has looked at the association between the fields of pre- and

10

postmigration study. Yet, knowing whether immigrants enrol in an educational program and whether they enrol in the same field as their premigration education are ways of determining to what extent foreign education is of lower value than local education.

Fourth, lack of information about available programs and services, along with lack of employer contacts, has been identified as one of the main barriers to receiving an informed, accurate, and fair assessment of foreign qualifications and experience for applicants to Canada (Canadian Alliance of Education and Training Organizations, 2003). This being said, there have been recent investments from the federal and provincial governments aiming to help newcomers have their certificates, diplomas, or degrees recognized and find jobs up to their skill levels. Recent initiatives provide accurate

information to prospective and new immigrants. There is a need for an updated outlook on what is being done to help immigrants get their foreign credentials recognized.

My dissertation touches on both aspects of credential recognition—foreign work experience and foreign education—and how they are linked to postmigration work experience and education, as well as dealing with regulated occupations and describing how immigrants obtain recognition of their foreign credentials and what governments and regulatory bodies do to help. In the first chapter, I examine the effect of foreign work experience on occupational match. This chapter was published as a paper, coauthored with Michael Smith and Jean Renaud, in the Canadian Journal of Sociology (2008). Knowing to what extent new immigrants secure employment in their field is one way of ascertaining whether their work experience is recognized in Canada. Linked to occupational fields is the idea that working in an occupation that is regulated in Canada is dependent on

11

in regulated and unregulated occupations. This paper, coauthored with Michael Smith, has been submitted to the Journal of International Migration and Integration. In general, regulated occupations require a higher level of education than unregulated occupations, and provide higher pay. As it will be shown in the second chapter, immigrants are slightly less likely to work in regulated occupations, despite their higher level of education than native-born Canadians. In order to better understand the role of education in labour market outcomes of immigrants, in the third chapter, I look at the determinants and payoffs of a match between pre-and postmigration education. This paper has been accepted for publication in the Canadian Journal of Higher Education. Finally, the fourth chapter summarizes foreign credential recognition processes in Canada and recent public investments to address this issue.

I analysed data from two longitudinal surveys, as well as the Canadian census. For Chapter 1, on occupational match, I focussed on Quebec immigrants and used data from the longitudinal survey of new immigrants to Quebec (ENI). The advantage of the ENI is that it follows a cohort of new immigrants for a long time (10 years).

For Chapter 2, on regulated occupations, I used the 2006 Canadian census. Because the objective of this chapter is to determine the proportion of Canadians working in

regulated occupations, the 2006 census data was the most appropriate and complete dataset. One of the key variables in this paper is place of education, which was included in the census for the first time in 2006.

For Chapter 3, on postmigration education, I used data from Statistics Canada’s Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, which follows a cohort of new immigrants

12

over a four-year period. The advantage of using the LSIC is that the immigrants in the sample come from all over Canada.

Finally, for Chapter 4, on the foreign credential recognition process, I relied on academic and policy papers, as well as information from government and regulatory bodies’ Web sites.

13

CHAPTER ONE

Economic Integration of New Immigrants: Match between Main Fields of Employment before and After Immigration to Quebec

Labour market outcomes of immigrants to Canada have been deteriorating for the last 25 years, whether compared with previous cohorts of immigrants or native-born workers. Despite a significant increase in education levels, the earnings differential

between new immigrants and native-born Canadians widened from the 1970s to the 1990s (Picot, 2004; Li, 2003). Among recent immigrants, men working full time saw their real income decrease by an average of 7% from 1980 to 2000 (Frenette & Morrisette, 2003). In 1980, newly arrived immigrant men earned 80% of native-born Canadian men’s income; in 1996, this figure was only 60% (Reitz, 2005).

Immigration almost always entails a labour market transition1. Such transitions can have either negative or positive effects, depending on their nature. For example, a

transition from employment to unemployment often affects career development adversely (see, for instance, Eliason & Storrie, 2006), while the transition from one job to another is more likely to be an improvement. Other factors that affect whether a transition is positive or negative are initial occupational situation, industry, and age (Spilerman, 1977). It could also be said that their position on the job market depends on whether the transition is the

1

14

result of immigration. Immigrants face three key issues: (1) they are less familiar with the local job market than are native-born Canadians, (2) their qualifications—education and training—may not be recognized or may be undervalued by potential employers, and (3) they may experience discrimination when looking for work.

The reluctance of Canadian employers to recognize foreign credentials is often cited as one of the key causes of the earnings gap between immigrants and native-born Canadians. The declining return on investment in foreign human capital, namely years of schooling and premigration work experience, is of major concern to government

authorities. There are two main issues. The first has to do with human capital being considered to be inadequate (De Voretz, 2005); a foreign degree is deemed of lesser value than a Canadian one (Thompson, 2000). The second has to do with statistical

discrimination by employers. Partly owing to their lack of familiarity with foreign qualifications, employers tend to generalize the qualifications of certain immigrants, deeming their work experience and educational background to be inferior, and so they are less likely to hire immigrants. The direct consequence of such discrimination is the underutilization of immigrants’ human capital (Thompson, 2000), which results in an estimated loss to Canada of somewhere between $2 and $5.9 billion dollars a year (Reitz, 2001a; Watt & Bloom, 2001).

Employers seem ill equipped to properly assess skills acquired abroad. A survey conducted by the Canadian Labour and Business Centre (2001) showed that business managers find language, along with problems assessing foreign training and work experience, to be the key hurdles encountered when trying to hire new immigrants. The

15

underutilization of immigrants’ skills shows just how unprepared employers are to assess the qualifications of potential employees (Li, 2000; Reitz, 2001a).

Foreign credential recognition depends on whether the occupation is regulated in the host country or not. Only about 20% of Canadian jobs are in regulated occupations (Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials, 2007). Quebec’s Professional Code defines two types of regulated occupations: those with reserved titles and those with reserved titles and the exclusive right to practise. Reserved titles may be used only by members of a professional order (governing body). In professions with the exclusive right to practise, only licensed members are permitted to perform certain acts. Professions with the exclusive right to practise require immigrants to gain accreditation in the province where they intend to practise. Some regulated occupations are governed by bodies other than professional orders. For instance, jobs in the construction industry are regulated by the Commission de la Construction du Quebec [building commission] (CCQ), and the department of education, recreation and sports is responsible for licensing teachers (except psychoeducators).

In the case of unregulated occupations, it is up to employers to evaluate qualifications. Quebec, like other provinces, offers a service that determines the

equivalence of training received outside of Quebec to that offered in the province, but few immigrants make use of it (Reitz, 2005).

The average pay premium associated with education is lower for immigrants than for the native born (Li, 2001; Alboim et al., 2005; Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001). Premigration work experience results in negligible gains in earnings (Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001; Alboim et al., 2005). Regardless of ethnic background and sex, annual

16

earnings are higher when training and experience is gained in Canada (Li, 2001; Alboim et al. 2005; Anisef et al., 2003). Net earnings (considering metropolitan region of residence, area of study, occupation, field of employment, language, level of education, work experience, and hours worked) of native-born Canadians, both men and women, visible minorities and white, who earned their degrees in Canada is higher than that of immigrants who earned their degrees outside of Canada (Li, 2001). Visible-minority immigrants, and particularly women, are the most disadvantaged in terms of annual earnings (Li, 2001; Alboim et al., 2005; Anisef et al., 2003).

It could be argued that if the premigration work experience of immigrants were recognized in the same way as locally acquired experience, immigrants would be better off; their incomes would increase because their work experience and skills would not be underutilized. A quick way to ascertain whether or not immigrants’ premigration

experience and training is recognized in Canada is to see whether they are working in the same fields as in their homelands. Nevertheless, most studies do not focus on the match between premigration work experience and jobs held in the host country, but rather on immigrants’ earnings (Li, 2001; Anisef et al., 2003; Picot, 2004; Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001; Wanner & Ambrose, 2003). There are some exceptions, such as Boyd and Thomas (2002), Crespo (1994), and Renaud and Cayn (2006).

Boyd and Thomas (2002) studied the occupational status of immigrant engineers and concluded that men trained outside of Canada are less likely to hold a managerial or engineering post. They also observed differences that depended on the engineers’

homelands: immigrants from Latin America, the Philippines, and Eastern Europe (except Romania and Yugoslavia) are less likely to be employed in their fields, while immigrants

17

from Great Britain, the United States, Europe (except Eastern Europe), and Oceania were more likely to obtain positions as engineers or managers.

Like Boyd and Thomas (2002), several other authors rely on census data, and, due to a lack of information on where a degree was obtained, make a guess based on the

person’s age at immigration (Li, 2001; Schaafsma & Sweetman, 2001; Anisef et al., 2003). These authors include all immigrants in their model, both recent immigrants and those that have been in Canada for more than 20 years. The problem with using age in this way is that it is not clear what is really being measured. Is it the place where the degree was obtained or knowledge of the local culture and labour market? Considering all immigrants, without taking into account cohorts, runs the risk of confounding economic situation and immigrant selection processes. It is quite likely that the recognition of qualifications was different (simpler or more complex) 30 years ago than today.

Crespo (1994) and Renaud and Cayn (2006) did not have to estimate country of education. They used longitudinal data that followed a group of recent immigrants and had information on where they had been educated. They measured the match between

occupational and socioeconomic status pre- and postmigration (Crespo, 1994), as well as access to jobs requiring a level of education equal or superior to their level of education completed prior to immigration (Renaud & Cayne, 2006).

By using the data from the longitudinal survey of new immigrants (ENI), Crespo observed that in the first 3 years after arrival, approximately 50% of immigrants in Quebec were at the same socioeconomic level as before immigrating. As well, the higher their socioeconomic status before immigration, the greater the probability that their

18

socioeconomic level would be lower in Quebec, suggesting that the more complex their work, the more difficult it is for them to become acculturated and obtain accreditation.

Renaud and Cayn (2006) used the data from a retrospective longitudinal study that surveyed 1,541 immigrants to Quebec in the selected skilled workers class. Five years after their arrival, 69% of those immigrants had found jobs requiring educational levels equal to or higher than their level of education completed prior to arrival in Quebec. They also observed that the odds of finding employment requiring the educational level attained before immigration depended partly on the country of origin (although for some regions, the effect is only temporary), level of education, completion of a French course since arrival, and whether the immigrants had found jobs before arriving.

In short, key factors that influence immigrants’ earnings and occupational match before and after immigration include visible minority status, region of origin, education level before immigration, sex, premigration socioeconomic status, and completion of a language course since arrival.

The objective of this study is to analyse the link between the main fields of

employment of recent immigrants in their homelands and their jobs in the host country, as well as the net effect of an occupational match on earnings.

Hypotheses, Data and Method

Based on the literature, we put forth the following hypotheses:

1. The literature suggests that the situation of immigrants is deteriorating and that the recognition of foreign qualifications can lead to a better position in the labour market. A significant proportion of immigrants does not find employment in their fields, or find it only after a long time.

19

2. Some individual factors, in particular those connected to human capital, such as knowledge of French or English, prearranged employment in the host country, and a degree earned in the host country, increase the probability of a match between main field of employment before and after immigration.

3. Other individual factors, connected to advanced qualifications (number of years of premigration work experience and education), reduce the chances of an occupational match.

4. Occupational match is also influenced by region of origin; immigrants from some regions are more likely to find similar jobs after immigration, while those from other regions are less likely to do so.

5. An occupational match leads to higher income.

Like Crespo (1994), we used data from the ENI, a 10-year survey of 1,000

immigrants who settled in Quebec in 1989. It lists all jobs, housing, and courses followed, in chronological order from first to last, with start and end dates. The data also include country of origin, educational level on arrival, and main field of employment before immigration.

The sample consists of immigrants aged 18 years or older of the independent, family, and refugee categories who arrived with a visa and intended to settle in Quebec. Between the middle of June and November of 1989, all potential respondents who arrived at any point of entry to Quebec were given a survey form. Invitations were sent to all potential respondents who applied to immigrate from outside the country. By this method of sampling, all immigrants arriving in Quebec with a visa obtained outside of Canada

20

were invited to take part in the study. However, asylum seekers who claimed refugee status at one of the Canadian borders or once arriving in Canada were excluded.

Respondents were interviewed after 1, 2, 3 and 10 years in Quebec. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 1,000 immigrants a year after their arrival. Two years after their arrival, interviews were held with 729 respondents. The third round, 3 years after arrival, was completed with 508 respondents. Ten years after their settlement, 426 people were interviewed. The decreased respondent pool is typical of longitudinal surveys of this scale; it is not due to interprovincial mobility, as “75% had a valid Quebec address 10 years after arrival, corresponding to a retention rate of 76%” (Renaud et al., 2003: 169). Rather, it is due in part to respondents’ refusals to continue, lack of response, missed appointments, or respondents’ death. “Comparison of the sample that responded in the first and last rounds reveals no significant differences in basic characteristics” (Renaud et al., 2001: 185). Also, some respondents who had not taken part in the second or third round of the study were found and participated in the fourth round. In round four, there were 426 respondents, which is a similar size sample to that in the third round (Godin & Renaud, 2005).

Our analysis employs two methods, survival analysis (survival curve and Cox regression) and multiple regressions. Survival analysis is a study of the occurrence or nonoccurrence of an event in a given data period. Initially only people who are at risk of experiencing the event are included (Morgan & Teachman, 1998). As time passes, people are removed from the population at risk: that is, those who have experienced the event (and so are no longer at risk of experiencing it) and those who have not experienced it because of a concurrent or disruptive event, or because the observation period ended

21

(censored cases). Here, the population at risk is defined as immigrants who had jobs before immigration. The dependent variable is the likelihood of finding a job in the same field in the host country.

Cox regression, used in multivariate analysis, is a considered a semiparametric model, because it models the effects of covariables on the hazard function, but does not specify the form of the hazard function (Luke, 1993). It is said to be a proportional-hazards model because for two given individuals, at any given time, the risk ratio is constant (Cox, 1972, cited by Luke, 1993: 224; Allison, 1991). In the case of a continuous independent variable, the coefficient indicates whether, for each additional unit of this variable, the chances of a rapid transition increase or decrease. In the case of a dichotomous or

categorical independent variable, the coefficient indicates whether the chances increase or decrease in relation to the reference category.

Results

Survival analysis was used to (a) describe the time taken to find a job in the same field as before immigrating (Kaplan-Meier survival curves), and (b) study the factors that influence access to employment in the same field (Cox’s regression model). Multiple regression was used to observe the net effect of relative match between pre- and postmigration jobs, on weekly earnings 1, 2, and 3 years after arrival in Quebec.

All immigrant cohorts are unique, as they reflect, at a given time, on one hand, global political and economic issues and, on the other, the state of the host society and economy. In this case, the key issues may be the Lebanon conflict and the transfer to Quebec of control over the selection and integration of immigrants. Although these factors

22

may cause variation in cohort composition, there is nothing to suggest that they affect the social rules or the factors under analysis.

Table 1

Numbers and Proportions of Immigrants, by Socioeconomic Characteristics, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Characteristics n % Sex Male 472 60.4 Female 310 39.6 Age on arrival 18–29 246 31.5 30–39 310 39.7 40–49 139 17.8 50–59 52 6.7 60 and older 33 4.2 Immigration category Independent 557 72.4 Family 126 16.4 Refugee 86 11.2 Region of origin

South America, Caribbean, and Central America 98 12.6

Western Europe and North America 123 15.8

Eastern Europe 45 5.8

North Africa and Middle East 333 42.7

Sub-Saharan Africa 34 4.4

23

Characteristics n %

Knowledge of French or English on arrival in Quebec 516 70.5

Education level on arrival in Quebec

Elementary or none 62 8.1

Secondary 214 27.8

Postsecondary 150 19.5

University 344 44.7

Average work experience (years) 16

Field of principle employment before immigration

Management 120 15.7

Natural and applied sciences 110 14.3

Health 45 5.9

Social science, education, government 80 10.4

Art, culture, recreation, sport 27 3.5

Clerical work 71 9.3

Sales and service 149 19.4

Trades, transport, equipment operators 48 6.3

Primary industry 18 2.4

Manufacturing 99 12.9

Notes. n=782. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

Respondents were found to have very high skill levels, as can be seen in Table 1. Most have a university degree (45%), while many have significant work experience (on average 16 years) and knowledge of French or English (71%). The majority of the respondents are independent immigrants (72%), and a significant proportion comes from North Africa and the Middle East (43%). Over 15% of survey participants held

24

management positions before immigrating, more than 14% held jobs in the natural and applied sciences, and approximately 20% worked in sales and service.

It should be pointed out that 126 (not shown in tables) of the immigrants who had worked before immigrating were in occupations governed in Quebec by professional orders with the exclusive right to practise (e.g., engineers, nurses, chemists). A further 29 had been elementary or high school teachers (the provincial department of education, recreation, and sports is responsible for granting teaching licenses), and 24 had worked in trades regulated here by the CCQ.

Time Spent Finding Work in Field

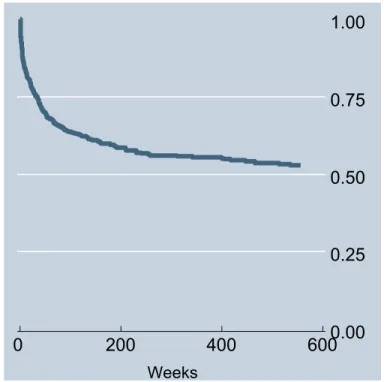

We first present a survival curve showing all entries into employment in the same category as main field of employment before immigration (Figure 1). We then look at the transition rate according to various individual and occupational characteristics, such as educational level on arrival, region of origin, knowledge of French or English, sex, immigration category, and field of employment.

A correlation curve is relatively simple to read. The x-axis represents the number of weeks before entering an initial period of employment. The y-axis indicates the percentage of respondents at risk of experiencing that event at a given time. All respondents who may potentially get their first job (postmigration) are found at the starting point (0). Gradually, people get jobs and from then on are no longer considered at risk.

In total, a little under half (47%) of the population at risk experienced the event, namely getting a job in the same field as the one held before immigration. The vast majority of people who find employment in their fields do so within the first few years (200 weeks, or approximately 4 years). This is a smaller percentage than found by Renaud

25

and Cayn (2006), who studied the time required to find a job calling for the level of education completed before immigration.

These different findings may perhaps be explained by the populations studied: Renaud and Cayn looked at principal applicants in the economic immigration category only (selected for their human capital, which is considered advantageous to the local labour market), while our analysis includes all three categories of immigrants. Renaud and Cayn also emphasize the fact that, due to the nature of the data used, they had to group all jobs requiring a university degree together in a single category, which may have had the effect of overvaluing requalification.

Figure 1.Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of

Employment Before Immigration, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=767. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks

26

These results partially support our first hypothesis. A little under half of

immigrants find employment in their desired fields. Contrary to what we expected, most of them do so in the early stages of settlement, not after a long time in the country.

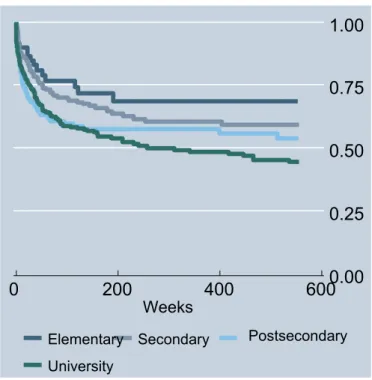

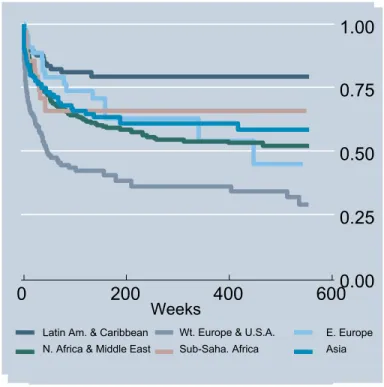

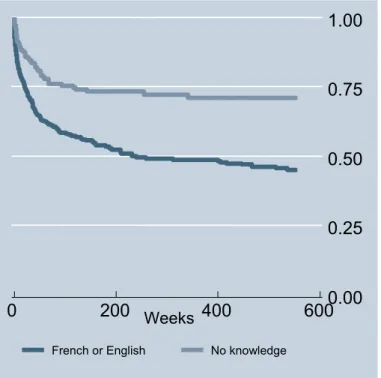

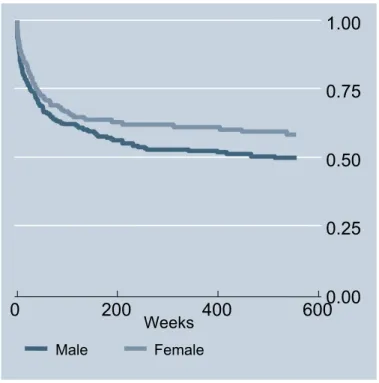

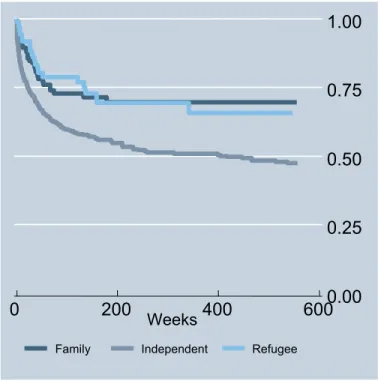

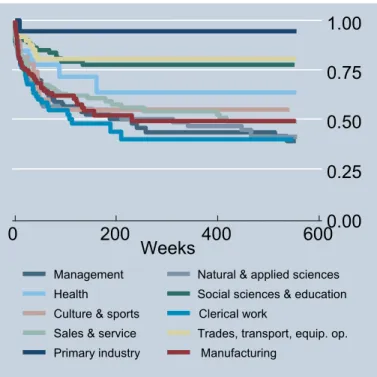

Figures 2 to 7 illustrate the gross differences, based on certain individual and occupational characteristics. Immigrants with high educational levels gain faster access to employment in their field than those without. We can also see a difference between people from Western Europe or the United States and those from other parts of the world: about 70% of the former are employed in their fields, while fewer than 20% of immigrants from South America, the Caribbean, and Central America are employed in their respective fields within 10 years of arrival. People with knowledge of one of the official languages, men, and independent immigrants were also found to gain faster access to employment in their fields.

These results reflect what the literature says about the existing disparities between men and women and about the variation across immigration categories, countries of origin, education levels, and knowledge of official languages. Fewer immigrants having worked in primary industry, health, social science, education or government, trades, or operating equipment find jobs in their fields than those who have worked in management, natural and applied sciences, sales and service, or manufacturing.

27

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of Employment Before Immigration, by Educational Level on Arrival, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=755. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks

Elementary Secondary Postsecondary

28

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of Employment Before Immigration, by Region of Origin, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=765. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks

Latin Am. & Caribbean Wt. Europe & U.S.A. E. Europe N. Africa & Middle East Sub-Saha. Africa Asia

29

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of Employment Before Immigration, by Knowledge of French or English on Arrival, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=721. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 Weeks 400 600

30

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of Employment Before Immigration, by Sex, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=767. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks Male Female

31

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of

Employment Before Immigration, by Immigration category, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=754. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks

32

Figure 7. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Immigrants who Begin a Job That Matches Main Field of Employment Before Immigration, by Field, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Notes. n=767. Source: Longitudinal survey of new immigrants.

Factors Influencing Match Between Main Fields of Employment Before and After Immigration to Quebec

Table 2 shows the results of three Cox regression models. The first model includes individual characteristics of immigrants on arrival in Quebec. In the second model, factors connected to activities that had taken place since their arrival were added, and the third model includes the field of employment in which they worked before immigrating. A

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0 200 400 600 Weeks

Management Natural & applied sciences Health Social sciences & education Culture & sports Clerical work

Sales & service Trades, transport, equip. op. Primary industry Manufacturing

33

negative coefficient indicates that the chances of the transition occurring rapidly decrease; a positive coefficient indicates that the chances increase.

When we look at individual characteristics, including human capital (education level, premigration work experience2, and knowledge of French or English), we note that men are more likely than women to find jobs in their fields. The differences between men and women persist even when postmigration activities and field of employment are taken into account.

All other things being equal, immigrants from Western Europe and the United States are more likely to find work in their fields than those from South America, the Caribbean, Central America, North Africa, and the Middle East. It is not clear whether these differences are the result of discrimination or whether training from the latter areas is actually of lesser value.

The three variables linked to human capital do not have the same effect on the dependent variable. Once other characteristics are taken into consideration, level of education is shown to have no effect, while knowledge of French or English increases the immigrants’ chances of finding employment in their fields. In addition, premigration work experience decreases access, if we take into account postmigration activities and field of employment. This demonstrates how little effect premigration education level and work experience have on an immigrant’s career path in Quebec.

2

Premigration work experience was calculated as age on arrival minus years of schooling minus six (presumed age when schooling began). This estimate is used because the ENI study does not have a direct measure for premigration work experience, and this occurs regularly in the literature (Li, 2000; Pendukar & Pendukar, 1998; Reitz, 2001a).

34

Table 2

Coefficients from Cox Regressions on Likelihood of Working in a Job That Matches Main Field of

Employment Before Immigration, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

Variable Reference category Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Female Sex Male .303 * .561 *** .529 *** Independent Family -.171 -.217 -.217 Immigration category Refugee -.200 -.377 -.274

Western Europe and N. America *** *** ***

South America, Caribbean, and Central America

-1.045 *** -.980 *** -1.015 ***

Eastern Europe -.556 -.497 -.420

North Africa and Middle East -.626 *** -.796 *** -.831 ***

Sub-Saharan Africa -.661 -.971 ** -1.076 **

Region of origin

Asia and Oceania -.431 * -.416 -.457 *

University

Elementary or none -.169 .072 -.045

Secondary -.204 -.006 -.307

Educational level on arrival in Quebec

Postsecondary -.127 .094 -.140

Premigration work experience (number of years) -.124 -.029 *** -.029 ***

Knowledge of French or English on arrival in Quebec

Yes .415 * .395 * .399 *

35

Variable Reference category Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Working in field other than that of job held before immigration

Yes -2.414 *** -2.397 ***

Not attending course *

Primary or secondary education -.376 -.384

Postsecondary training -.553 * -.585 *

Taking course since arrival in Quebec

COFI or other language courses -.636 * -.628

Not earning degree/diploma

Primary or secondary education -.027 .001

Postsecondary training .220 .185

Earning degree/diploma in Quebec

COFI or other language course -.068 -.062

Health ***

Management .704 *

Natural and applied sciences .588

Social sciences, education, gov. -.300

Art, culture, recreation, sport .569

Clerical work 1.023 **

Sales and service .793 *

Trades, transport, equipment operators

-.021

Primary industry -1.200

Main field of employment before immigration

36

n 698 698 698

Log-likelihood ratio of model -1721.628 -1631.099 -1609.788

Chi square of model (sig.) (.000) (.000) (.000)

Notes. For every model, posttests were conducted for each of the polydichotomous variables in order to learn the relative contribution of these independent variables to explaining the dependent variable. The results, when significant, are indicated on the line of the reference variable. Adapted from ENI–10 years.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

In models 2 and 3, it can be seen that working in Quebec in a different field considerably lowers immigrants’ chances of finding jobs in their field. Can we therefore conclude that local experience affects employability more than past experience and that new experience can change a career path? Taking a course in Quebec has little effect on the dependent variable; at best it may have a negative effect, due to the fact that, while taking a course, an immigrant is not looking for a job. The fact that a diploma obtained in Quebec has no effect on the dependent variable may mean that immigrants are changing career paths. If local degrees or diplomas have little effect on immigrants’ chances of finding work in their own fields, this may be due to the fact that a local degree or diploma, like local working experience, may very well lead to another career.

These results partially support our second, third, and fourth hypotheses: that occupational match is partially determined by individual factors such as those related to human capital, high skill level, and region of origin. Knowledge of French or English, prearranged employment, premigration work experience, country of origin, sex, and work

37

experience in another field in Quebec partially explain the dependent variable. All other things being equal, other variables, such as immigration category, educational level on arrival, and a degree or diploma obtained in Quebec, have no influence on access to employment in the same field.

The results of the likelihood ratio3 tests indicate that we can reject the null hypothesis that all three models fit the data equally well. The third model is a better fit than the other two, as the last regression model demonstrates that people who work in certain fields before immigration are more likely to find employment in the same field afterwards. All other things being equal, immigrants who worked in management, clerical jobs, sales and services, or manufacturing are more likely to find jobs in their fields than those in health occupations.

There seems to be a difference between regulated and unregulated occupations. Many occupations in health care and the natural and applied sciences are regulated and licensed professionals have the exclusive right to practise; the trades are largely governed by the CCQ. We found no difference between those fields. Most occupations in sales and service, clerical work, manufacturing, and management are not regulated. We also found significant differences between these fields and that of health occupations.

The third hypothesis was not confirmed. We expected the dependent variable to be connected to skill level, that is, that it would be difficult to find a highly skilled job, such as one in management. Although it is easier to find jobs in fields requiring lower skill levels (such as clerical work, sales and service, and manufacturing) than in the health

3

Likelihood ratio tests comparing Model 1 to Model 3: chi square = 223.68***. Likelihood ratio tests comparing Model 2 to Model 3: chi square = 42.62***.

38

sector, it is easier to find a job in management, which requires a high skill level.4 The results lead us to believe that there is a difference between regulated and unregulated occupations.

Occupational Match and Weekly Earnings

Here we tested the net effect of a match between pre- and postmigration fields of employment on weekly earnings soon after arrival in Quebec. To do this, we performed a series of multiple regressions, where the dependent variables were weekly earnings 1 , 2, and 3 years after arrival. These intervals were considered because they are close to the times when respondents were interviewed; this allows us to avoid problems of estimation at specific points in a long interval. To allow us to determine the net effect, the regression models include a series of control variables, which correspond to the individual

characteristics and fields of employment used in the Cox regressions of Table 2. Each period includes two regression models, the first with the control variables only and the second with the match variable added. We wanted to see whether, aside from individual characteristics and field of employment, a match between occupation before and after immigration contributes significantly to an increase in weekly earnings.

Table 3 demonstrates that, all other things being equal, finding a job in one’s field increases weekly earnings even after 3 years in the host country; the increase varies between $226.94 and $306.34. This finding supports the idea that recognition of premigration experience leads to a higher income. Sex significantly explains weekly

4

In the ENI survey, the 1980 Canadian Classification and Dictionary of Occupations (CCDO) was used to codify jobs held in Quebec and main field of employment before immigration. An approximate level of education is attributed to each code in the CCDO, which was used to evaluate the level of skills required in the various fields.

39

earnings disparities, but only 1 year after arrival. Taking into account human capital and other characteristics, wage disparities based on region of origin are present 1 year after settlement, but tend to disappear after 2 and 3 years. This finding is similar to that of Cayn and Renaud (2006), who also observed a temporary effect based on country of origin.

Table 3

Coefficients from Multiple Regressions Models Regressing Weekly Earnings One, Two, and Three Years After Arrival on Socioeconomic Characteristics, Immigrants with Premigration Work Experience who settled in Quebec in 1989

1 year 2 years 3 years

Model 1a Model 1b Model 2a Model 2b Model 3a Model 3b

Male 106.30*** 87.50** 127.23 97.22 16.20 -9.63

Immigration category (independent)

Family 29.81 31.98 -140.51 -142.96 -244.33* -257.14*

Refugee 24.34 18.89 -322.44* -289.95* -351.31* -338.54*

Region of origin

(Western Europe and North America) South America,

Caribbean, and Central America

-183.86*** -118.82* -307.08* -207.93 -196.94 -117.82

Eastern Europe -142.20* -86.40 -67.39 2.89 -89.20 -26.28

North Africa and Middle East

-284.74*** -231.00*** -357.30*** -278.63 ** -223.57* -158.81

Sub-Saharan Africa -353.87*** -300.04*** -220.80 -151.29 -57.70 -14.86

Asia and Oceania -242.09*** -193.92*** 53.32 104.26 62.66 112.82

Educational level on arrival in Quebec (university)

Elementary or none -4.08 7.30 -58.92 -47.66 -31.57 -41.83

40

1 year 2 years 3 years

Model 1a Model 1b Model 2a Model 2b Model 3a Model 3b

Postsecondary 20.49 19.45 -59.09 -38.34 -51.42 -45.60

Prearranged employment 92.75* 72.24* -101.61 -123.31 -25.57 -29.19

Work experience before immigrating (years)

-3.43** -2.40* 3.92 4.54 3.63 3.73

Knowledge of French or English on arrival

93.42** 70.90* -69.40 -99.57 -144.11 -166.97

Field of employment before immigration (sales and service)

Management 116.91** 126.03** 480.61*** 458.40*** 537.34*** 510.00***

Natural and applied sciences

178.88*** 185.01*** 224.51 222.94* 313.03* 307.63*

Health -20.67 16.80 30.38 49.86 -.35 -3.79

Social science, education, government

67.04 116.34* 161.99 208.14 184.91 210.35

Art, culture, recreation, sport 45.66 72.34 -84.27 -94.09 161.03 137.43 Clerical work -11.05 -26.98 133.10 71.83 67.95 10.69 Trades, transport, equipment operators 114.15* 150.40** 83.56 130.94 181.61 219.48 Primary industry -3.75 41.14 -196.62 -125.49 -93.24 -35.49 Manufacturing 56.90 40.03 103.01 65.78 124.61 85.02

Finding work in one’s field 226.94*** 306.34*** 231.01**

TOTAL 660 660 485 485 335 335

R2 0.228*** 0.316*** 0.130*** 0.171*** 0.112* 0.136**

Note. Adapted from ENI–10 years.

Having arranged a job before settling in Quebec and knowledge of French or English leads to higher weekly earnings, but only 1 year after settlement. Every additional

41

year of premigration work experience tends to slightly decrease weekly earnings 1 year after settlement, but has no effects on earnings after 2 and 3 years. This is consistent with the literature, which reports no gains in earnings attributable to premigration experience.

There are also earnings differentials according to field of employment before migration. We found that immigrants who worked in management and in the natural and applied sciences had higher weekly earnings than immigrants who worked in sales and service, 1, 2, and 3 years after arrival.

R2 is an indication of the proportion of total variance explained by the variables in the equation (see bottom of Table 3). Hierarchical regression analysis allows us to

determine whether finding a job in the same field as before immigration contributes, outside of the sociodemographic variables and field of employment, to an explanation of observed disparities in weekly earnings. Sociodemographic variables and field of

employment explain 22.8% of variance in weekly earnings 1 year after settlement, 13% after 2 years, and 11.2% after 3 years. Occupational match adds 8.8% [R2 of Model 1a (31.6%) - R2 of Model 1b (22.8%)] to the explanation of variance after 1 year, 4.1% after 2 years, and 2.4% after 3 years.

Conclusion

Our analysis focused on three key objectives: (a) to demonstrate the rate of access to employment in the main field of employment prior to immigration, (b) to identify factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of finding a job in the same field, and (c) to determine whether finding a job in the same field brings with it earnings benefits 1, 2, and 3 years after settlement.