1

This project is funded by the European Union under the 7th Research Framework Programme (theme SSH) Grant agreement nr 290752. The views expressed in this press release do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Working Paper n°23

Formalization and social cohesion: Evidence

from rural Rwanda

Ombeline De Bock

UNamur

Formalization and social cohesion: Evidence from rural

Rwanda

Ombeline De Bock*

April 15, 2015

Abstract . *FNRS Research Fellow CRED, University of NamurFaculte des Sciences Economiques, Sociales et de Gestion Rempart de la Vierge 8, 5000 Namur, Belgium

Tel: +32(0)81725326 Fax: +32(0)81724840 Email: ombeline.debock@unamur.be

The survey and experiment upon which this analysis is based was funded by the World Bank. I am grateful to Catherine Guirkinger and Jean-Philippe Platteau for their supervision, encour-agement and helpful discussions. An earlier version of this paper has been presented at the CSAE conference (Oxford) and at seminars in Namur and Louvain-la-Neuve. I would like to thank Marcel Fafchamps and Imane Chaara for very useful comments and all seminar participants for helpful feedback. Finally, I am extremely grateful to the whole team of enumerators and the kind and patient respondents.

Contents

1 Introduction 4

2 Data and sampling frame 7

3 Measures of formalism and social connectedness 8

3.1 Measure of formalism . . . 8 3.2 Measure of social connectedness . . . 9

4 Limited commitment issues within groups 11

5 Can formalism help to overcome limited commitment issues? 13

6 An alternative measure for Social Connectedness : Heterogeneity in origin 16 6.1 Link between social connectedness and place of birth . . . 17 6.2 Formalization and heterogeneity in origin . . . 18

7 Discussion and concluding remarks 20

1 Introduction

In many developing countries, where the judicial system is typically weak and where contracts are not legally protected against defaulting, there exists a multitude of membership-based organisations aiming at providing financial services to their members alongside more formal alternatives to access financial services1. If these informal organisations persist despite the enforcement constraints they

face, we are tempted to ask how those financial groups overcome commitment issues and sustain cooperation?

Individuals may have both intrinsic and extrinsic motives to commit and cooperate in groups. Greif and Tabellini (2012) acknowledge, on the one hand, that individuals might identify with the social group in which they participate, thus creating moral obligations and cooperative behaviour. But, on the other hand, they point out that punishments or material rewards provided by formal or informal institutions also influence incentives to cooperate (Greif and Tabellini (2012), p3). In this respect, Hayo and Vollan (2012) provide experimental evidence showing that well-defined rules can take on this role of coordination of beliefs and lead to cooperation in the context of South-Africa and Namibia. In the same line, Anderson et al. (2009) find that opting for fixed roscas rather than random ones (in which the order of the turns is gambled) can contribute to reduce enforcement problems. Hence, by designing the appropriate institutional structure and rules, expectations of cooperation are improved.

Does the implementation of formal rules rather act as a complement for social cohesion by disciplining closely related members, or does the degree of formality used in groups compensate for a lack of social connectedness through explicit coordination mechanisms? If so, participants would not need to trust the other group members, they would only need to trust that the rules will be actually enforced so that other members act in the way congruent with their own interests. The literature has not reached a consensus so far on this. Indeed, a first strand of the literature argues that rules and interpersonal relations within informal groups act as substitutes (Zucker (1986); Ring and Van de Ven (1994); Uzzi (1997); Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001); Zaheer and Venkatraman (2007); Schelling (1960)). For instance, Bowles and Gintis (2004) claim that culturally homogeneous networks can be successful in sustaining a cooperative equilibrium precisely because they have the capacity to promote trust among members, which enables them to enforce informal contracts. In line with this school of thoughts, roscas in which social cohesion is strong were found to display more flexible contractual arrangements (Handa and Kirton (1999)). Analogously, Sitkin and Roth (1993) note that many organizations adopt control mechanisms such as contracts, bureaucratic procedures, or legal requirements to make up for low levels of inter-personal trust between management and

1For instance, it is interesting to note that, in Rwanda, a distinction was already made according to the level

of formalization of the groups in the late 80s (Nzisabira (1992)). While cooperatives were articulated around a written contractual basis and had been going through an administrative registration, roscas were spontaneous popular associations without holdings in common. In practice, however, a third of all existing roscas in 1987 were registered at the local level.

employees. The same idea translates in the context of informal financial institutions, as illustrated by Anderson et al. (2010)’s model, in which social pressure and formality act as substitutes in roscas. According to the authors, members of roscas that are difficult to enforce are the most susceptible to social pressure. More closely related to our work, in a paper describing the functioning of funeral associations in Tanzania and Ethiopia, Dercon et al. (2006) allude to the presumable importance of rules and regulations in heterogeneous groups, stating that “these more formal organizations [funeral associations] can afford to allow people from a more diverse background to become members, presumably since clear rules and regulations can compensate for some of the informational and enforcement advantages of social and geographical proximity” (Dercon et al. (2006), p21).

In particular, the lack of mutual confidence inhibiting cooperation may encourage individuals to strategically join informal groups in which their interest will be better protected thanks to rules (Aghion et al. (2010); Claibourn and Martin (2000); Sitkin and Roth (1993)). Note that the causality is not clear since, on the one hand, distrust is expected to drive the demand for regulation but, on the other hand, (de-)regulation influences the level of interpersonal trust2. A large body of

the literature bring empirical evidence, often through experimental settings, that rules are needed to compensate for the absence of trust-building mechanisms (Bowles and Gintis (1998), Falk and Kosfeld (2006) and Fehr and Rockenbach (2003), Vollan (2008), Rietz et al. (2012), and Bénabou and Tirole (2005))3.

Another strand of the literature presents rules and interpersonal relations within informal groups as mutually reinforcing. In a field experiment testing the changes in level of commitment and infor-mation available, Barr and Genicot (2008) observe that players are more likely to form risk sharing groups when the arrangements are externally enforced by the experimenter. Surprisingly, when social sanctions are facilitated by making defections public, the likelihood to pool risk decreases. According to the authors, this results either from an excessive discounting of future sanctions which leads individuals not to participate in order to avoid the temptation of defecting in the future (and incur the costly sanction), or simply from the fact that sanctions are costly to inflict. The most relevant result of Barr and Genicot (2008)’s research is that grouping with relatives tends to take place only in the presence of strong enforcement mechanisms. When enforcement solely relies on intrinsic motivation, relatives tend to distrust each other.

Similarly, Anderson and Francois (2008) observe that ethnically homogeneous self-sustaining groups in a Kenyan slum seem to choose more formal structures of governance than heterogeneous groups. In a seminal attempt to formalize this intuition, they develop a model to investigate which

2See Malhotra and Murnighan (2002) for an in-depth discussion

3More generally, a parallel can be established with Greif and Tabellini (2012)’s work entitled “The clan and the

City” comparing social organizations and the different development paths in China and Europe. In their paper, they pinpoint that cooperation in clans, in which no rules are formally enforced, rely on strong moral obligations but are limited in scope, as they apply only toward kin. Conversely, the authors state that in more heterogeneous communities or cities, though generalized towards all citizens, moral obligations are weaker and social interactions are regulated through formal institutions.

types of groups choose formalization procedures. The major innovation of their model is to take into account the non-pecuniary costs on the punisher when a sanction has to be imposed on delinquent group members. According to their rationale, these social costs are higher when kinship ties are strong. This is due to problems of enforcement and credibility of punishment and difficulties in disciplining family members. In response to these extra costs, the model conjectures that groups of homogeneous ethnic structure react either by imposing a membership fee or by implementing a significant number of rules and sanctions that codify the actions to be taken in case of non-compliance with the social norms.

Additionally, Bold and Dercon (2014) develop a model in which they posit a positive correlation between social cohesion and enforcement constraints. The aim of their model is to understand why formal and informal risk-sharing institutions coexist despite the pareto superiority in terms of consumption smoothing of the former organisational form. They confirm the complementarity between social cohesion (as measured by the percentage of relatives in the group and trust) and the ability to enforce contracts by means of a data set on funeral insurance groups in Ethiopia.

This chapter provides new evidence on the relationship between the stringency of formaliza-tion and the intensity of social connectedness using a unique dataset on informal groups in rural Rwanda. A strength of our analysis is that it relies on precise measures of social connectedness across group members. We find a complex relationship between average social connectedness and the degree of formalism. Indeed, we find non-linearities that may reconcile previous findings and nuance the reasoning. Moreover, our analysis raises the awareness that informal groups have to be distinguished in order to discuss their incentives to establish written rules and procedures to discourage opportunistic behaviour. Indeed, we show that the positive relationship between average social connectedness and formalism is especially relevant inside groups offering insurance services.

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows. Section two presents the types of groups considered and describes their functionning. Section three details the variables used to measure formalism and social connectedness. Section four looks whether the scope of social connectedness in financial groups influences the occurence of commitment problems. In Section five, we explore empirically the role of formalism to overcome commitment problems. The relevance of using the place of origin as a proxy for social connectedness is discussed in Section six. Finally, the po-tential mechanisms driving the results are discussed in Section seven and concluding remarks are formulated.

2 Data and sampling frame

Like in the third chapter, this work is based on first-hand survey data collected in rural Rwanda between May and July 2011 and including a specifically designed questionnaire on participation in financial groups. The overall sample of this study consists of 402 individuals spread over 50 villages in two districts of the Eastern Province, Rwamagana and Ngoma. Nonetheless, we take a slightly different approach than in chapter three since the main unit of analysis used in the present chapter is the informal financial group. For the purpose of this chapter, we define the “informal” groups as initiatives of a group of individuals who decide to meet in order to save, borrow or insure each other and agree upon rules whose enforcement is typically executed by members of the group themselves, without legal recourse.

We have seen in the previous chapter that the incidence of informal groups offering either credit, savings or insurance is relatively high in rural Rwanda. Indeed, the participation rate in the studied area, regardless of the services offered, is 59%4. More precisely, participation in rotating savings

and credit associations (roscas) reaches 40% and 29% in groups offering insurance services. In total, detailed data has been collected on 267 groups offering at least one of the above mentioned financial services. However, we focus on 203 groups for which we have systematic information on every group member, collected through interviews of the respondent belonging to the group.

A specifically designed module of the questionnaire gathered general information about past and current participation in all types of groups and associations. Then, group members had to answer a specific module for each type of service offered (insurance, credit and savings). In these specific modules, questions on governance, mode of operation, enforcement rules, amount of contributions, use of the money and perceptions were asked. Moreover, a very detailed module has been devoted to the composition of the group and the intensity of familiarity between the respondent and each member of the group. The analysis of the present chapter is largely based on this original and extremely detailed module.

We refer to Section 3.4.2 in the previous chapter for a detailed description of the functioning of informal groups active in rural Rwanda. In that Section, rotating savings and credit associations (roscas) and groups offering insurance services are systematically presented, their specificities are defined and their way of functioning explained. The reason to focus on these two types of informal groups is that they are particularly vulnerable to commitment problems. Indeed, non compliance with the functionning of the group (drop outs before the end of the cycle,...) can have devastating consequences for the other group members, jeopardizing the survival of the group.

Of particular relevance for the current research question are the differences in the modes of

4Other studies find 13% participation in Tanzania (Narayan and Pritchett (1999); La Ferrara (2002)), 27% in

Uganda (Peterlechner (2009)), 30% in Kenya and South Africa (Haddad and Maluccio (2003)) and 53% in rural Kenya (Jakiela and Ozier (2012)) and 57% for roscas in a Kenyan slum (Anderson et al. (2009)). One exception achieves almost a comprehensive coverage, namely burial societies (the so-called “iddir”) in Ethiopia with 80% membership (Dercon et al. (2006)).

operation between both types of groups. While roscas have a relatively well-established way of functioning, namely the rotative access to a common pot, insurance groups have more room for manoeuvre when defining their internal mode of operation. Note also that membership in the mutual assistance groups is a commitment in the longer run (on average more than 4 years) than what is common for an ibimina (less than 2 years on average).

3 Measures of formalism and social connectedness

The aim of this section is to present, in turn, how the measures of formalism and of social con-nectedness used in order to test the substitution hypothesis between rules and social concon-nectedness within groups have been constructed.

3.1 Measure of formalism

Following Anderson and Francois (2008)’s logic, we define formalism as the set of rules agreed upon that prevents relying on discretionary power of the decision makers in case of contingencies. As mentionned above, the auhors test their model’s predictions using data from Kibera, a Kenyan slum, where participation in informal groups is widespread. To do so, they compute an index of formalism based on five binary measures of formalism, using principal component analysis. The first binary variable indicates whether the group is registered and hence subject to external oversight. Having written rules and keeping minutes of the group’s meetings are two other variables considered in their index of formalism. Groups having a bank account is an additional indication of formalism. Finally, having formal penalties is also included in the index. A group is classified as “highly formalized” only when the five conditions are fulfilled (which is the case for 30% of their groups).

In our case, in order to remain as close as possible to their definition of formalism with the available data, three possible measures of formalism can be used to compute the high formalism index. More specifically, we construct a variable taking value 1 if the group fulfills at least two of the three following criteria: having written rules and statutes, imposing sanctions for delay and/or absence and having a bank account.

Among these three variables, written rules is the broadest one. Indeed, these written rules define, among others, the frequency of the group meetings, membership procedures, the order of allocation of the pot (in roscas), payout schedules, contributions and measures to be taken in case of non-compliance such as the foreclosure of the collateral, the imposition of fines, etc. Written rules are thus largely encompassing whereas the two other variables are only partial indicators of formalism. As a matter of fact, “sanctions” mostly consist of a set of fines for absence to the group’s meetings (roughly around 10% of the monthly contribution) rather than a systematic punishment for non-payment of contributions. Finally, when groups place the commonly held money on a deposit

account in a financial institution, the bank account variable takes value 1. Yet, deposits on bank accounts are useless in roscas since there is a rotative allocation of the pot to the group members. Hence, the bank account variable provides only partial information on the level of formalism, as its relevance is limited to insurance groups.

3.2 Measure of social connectedness

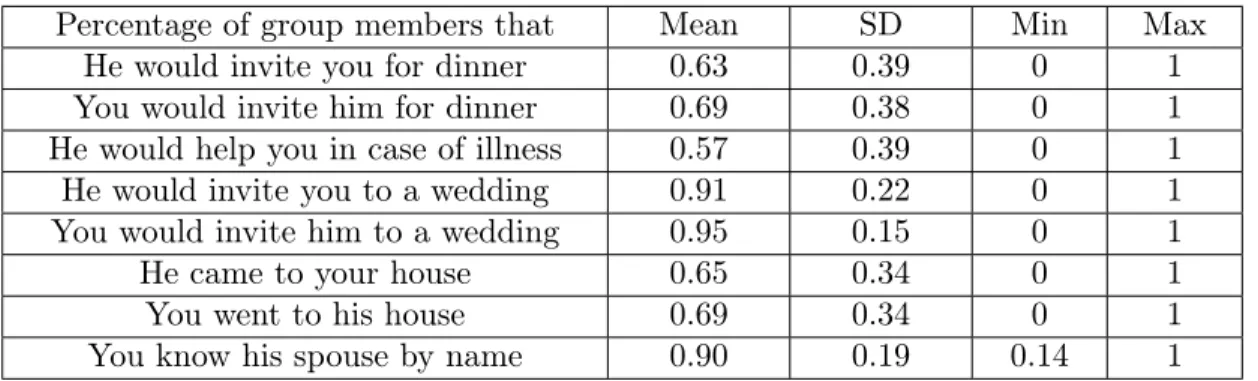

As mentioned earlier, Anderson and Francois (2008)’s main assumption is that groups of eth-nically homogeneous structure are presumably rich in social ties and inter-individual connections. One original feature of our paper is to exploit a novel and more direct measure of social connected-ness. Indeed, we have asked to every respondent to answer a set of questions about the frequency and the type of relationship he maintains with every co-group member. Table 1 presents several variables measuring social connectedness among members. The first column shows the average proportions of members who answered positively to a set of binary questions. In the third column, we report the minimum percentage among the 203 groups for which we have information while the maximum is reported in column four.

After listing all group members individually, respondents were asked specific questions for each and every other member, including six questions meant to assess how close the respondent is to the other member. A first set of hypothetical questions ask how he or she would react to a hardship experienced by each other member. The symmetric question on how the respondent would act has also been asked. For instance, in the first column, group members think, on average, that 63% of members would share their meal with them in case of hardship. Similarly, those respondents would invite their needy co-member for dinner in 69% of the cases, on average. Note that this practice is far from common in the Rwandan context and was almost non-existent in the pre-genocidal context, when “local inhabitants would forbid their children to go into the house of some neighbours or relatives for fear that they could be poisoned” (André and Platteau (1998)). This is especially true in the surveyed region, where several poisoning cases have been reported. To some extent, this set of questions measures the willingness to ask for help. Then, a set of factual questions have been asked, such as whether the respondent had ever visited every specific co-member. Hence, we can see from the first column that an average of 69% of group members have already visited the other members at home.

In order to ensure enough variation in the social connectedness variable, we do not include the variables whose means are equal or above 90%, namely indications on wedding invitations and for every group member, knowledge of the name of the spouse. Indeed, such practices seem to be very common within all groups. Among the five remaining variables, redundancies are found when the question and its symmetric counterpart are asked. Therefore, we keep only the other member’s behaviour with regard to home visits and meal sharing.

Table 1: Social Connectedness variables

Percentage of group members that

Mean

SD

Min

Max

He would invite you for dinner

0.63

0.39

0

1

You would invite him for dinner

0.69

0.38

0

1

He would help you in case of illness

0.57

0.39

0

1

He would invite you to a wedding

0.91

0.22

0

1

You would invite him to a wedding

0.95

0.15

0

1

He came to your house

0.65

0.34

0

1

You went to his house

0.69

0.34

0

1

You know his spouse by name

0.90

0.19

0.14

1

Hence, the definition of social connectedness used for the main specification is based on indica-tions on home visits, meal sharing and aid in times of need. More specifically, we construct a social connectedness variable (denoted SC) between the respondent and each member of the group taking value 1 if and only if those three criteria are fulfilled5. Then, we compute the average social

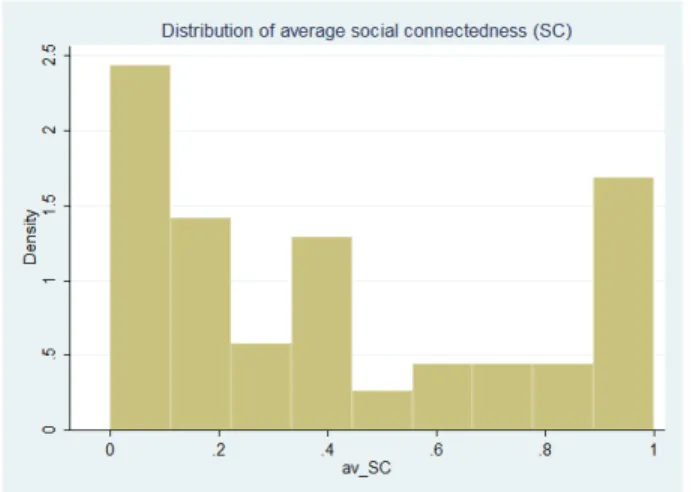

con-nectedness within each group by taking the average of those individual SC measures. This variable thus measures the scope of the intensity of familiarity among group members. It takes a high value if most members are closely linked whereas groups in which many participants have few contacts with each other will display a low score of average social connectedness. At the one extreme, when nobody knows any other group member personally in the group, the average social connectedness variable equals 0. At the other extreme, when all participants maintain close relations with every other group member, the variable is equal to 1. Between these extreme values, groups are hetero-geneous in their average social connectedness level in the sense that some group members maintain close relationships with others while being unfamiliar to the rest of the group. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the average social connectedness variable, ranging from 0 to 1, used in the main specification.

However, we construct four alternative social connectedness variables to test the robustness of the results to a change in the definition. A first alternative measure replaces, in the previous definition, the questions on home visits and meal sharing by the symmetric side of the question (namely considers the respondent’s behaviour rather than the other member’s one). It thus takes value 1 if and only if the respondent would invite the other member for dinner in case of need and if he visited the other member at home and if he would help him in case of illness. We denote this alternative Social Connectedness variable SC1.

A second alternative measure, SC2, keeps both sides of the symmetric question. This measure then takes value 1 if and only if the five questions are positively answered for each group member.

5It thus takes value 1 if and only if the other member would invite the respondent for dinner in case of need and

Figure 1: Distribution of Average SC

The third alternative measure of social connectedness, denoted SC3, includes all the variables presented in Table 1, regardless of their mean. Finally, the last alternative measure of social connectedness, denoted SC4, takes value 1 if at least one of the symmetric questions is positively answered. The distributions of these alternative variables can be found in Figure 3 in the appendix. In addition, Section six presents a proxy for social connectedness and familiarity among group members, that is recurrently found in the literature. More specifically, we consider the place of birth of the group members, since local people are reckoned to be embedded in a dense social network (Bonleu (2014)). To do so, we construct the percentage of men who were born in the village where they currently live, by dividing native male members by the total number of men in the group. This variable ranges between 0 and 1 and is denoted “percentage male natives”. Note that the sample is restricted to 179 groups since 24 groups are exclusively composed of female members. We then replicate the regressions using this variable instead of our direct measure of social connectedness in order to test the relevance of this proxy.

4 Limited commitment issues within groups

More than one third of the groups have been exposed to problems. These arise from irregularities of payment (44%), attendance (17%), management and fraud (29%), or interpersonal conflicts (4%). As noted in the introduction, we have found the following ambiguity in the literature: while a large literature suggests that coordination capacity and enforcement ability are positively linked with the strength of social cohesion (e.g. Bold and Dercon (2014); Durlauf and Fafchamps (2005)), some authors argue that it is precisely more difficult to discipline closely related group members (e.g. Anderson and Francois (2008)). Indeed, when there is a high level of social connectedness,

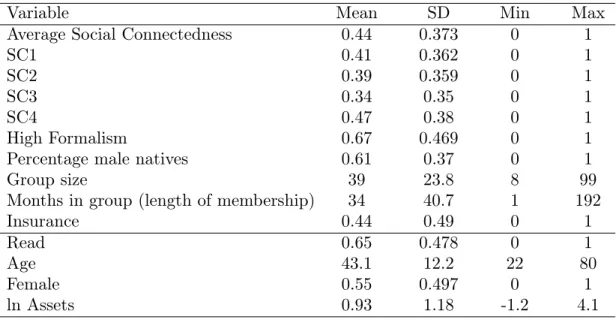

Table 2: Summary statistics, group-level data

Variable

Mean

SD

Min

Max

Average Social Connectedness

0.44

0.373

0

1

SC1

0.41

0.362

0

1

SC2

0.39

0.359

0

1

SC3

0.34

0.35

0

1

SC4

0.47

0.38

0

1

High Formalism

0.67

0.469

0

1

Percentage male natives

0.61

0.37

0

1

Group size

39

23.8

8

99

Months in group (length of membership)

34

40.7

1

192

Insurance

0.44

0.49

0

1

Read

0.65

0.478

0

1

Age

43.1

12.2

22

80

Female

0.55

0.497

0

1

ln Assets

0.93

1.18

-1.2

4.1

group members can impose a higher pressure such that fewer people are tempted to renege. Yet, the cost of punishment to the abiding group members may also debilitate threats of sanctions and exclusion when a member deviates from the agreed-upon rules. In other words, the two effects work in opposite directions and it is not obvious which effect will dominate. The question whether rules, sanctions and peer pressure can effectively discourage opportunistic behaviour in close-knitted groups thus remains open.

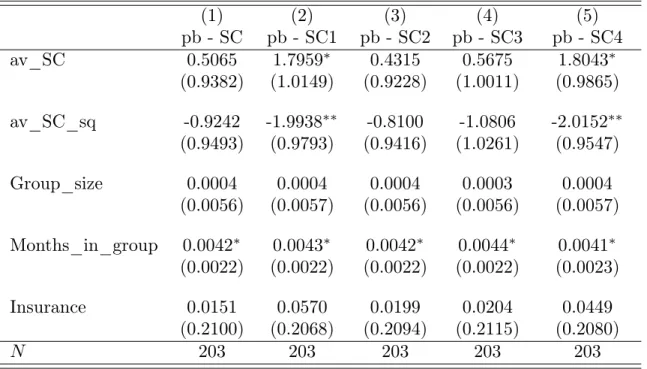

As a first look into this issue, we investigate whether the strength of average social cohesion is correlated with the experience of enforceability problems within financial groups. Table 3 shows the relationship between average social cohesion within groups and a dummy equal to 1 if the group has experienced internal problems in the past 12 months. Columns 1 to 5 of Table 3 report the results for every definition of Social Connectedness. The quadratic term of social connectedness is included in all specifications in order to allow for a curvilinear relationship between both variables. Moreover, standard errors are systematically clustered at the village level. In columns 2 and 5, the coefficients for the average social connectedness variable are positively correlated to the occurence of problems in the group, in line with the argument that disciplining closely knitted members is not trivial. However, this relationship is not linear and we observe an inverted U-shape. In other words, starting from low levels of familiarity between group members, an increase in average social connectedness is related to an increase in the number of groups reporting internal problems. Yet, as soon as the average SC reaches a minimum threshold (above 0.45), the number of groups reporting problems in the past 12 months decreases. This might indicate a more complex relationship that

Table 3: Average SC and problems within groups

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

pb - SC

pb - SC1 pb - SC2 pb - SC3

pb - SC4

av_SC

0.5065

1.7959

⇤0.4315

0.5675

1.8043

⇤(0.9382)

(1.0149)

(0.9228)

(1.0011)

(0.9865)

av_SC_sq

-0.9242

-1.9938

⇤⇤-0.8100

-1.0806

-2.0152

⇤⇤(0.9493)

(0.9793)

(0.9416)

(1.0261)

(0.9547)

Group_size

0.0004

0.0004

0.0004

0.0003

0.0004

(0.0056)

(0.0057)

(0.0056)

(0.0056)

(0.0057)

Months_in_group

0.0042

⇤0.0043

⇤0.0042

⇤0.0044

⇤0.0041

⇤(0.0022)

(0.0022)

(0.0022)

(0.0022)

(0.0023)

Insurance

0.0151

0.0570

0.0199

0.0204

0.0449

(0.2100)

(0.2068)

(0.2094)

(0.2115)

(0.2080)

N

203

203

203

203

203

Marginal effects; Standard errors, clustered at the village level, in parentheses

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1. ⇤ p < 0.10, ⇤⇤ p < 0.05, ⇤⇤⇤ p < 0.01

deserves further investigation. In Section 4.7, we propose an explanation for this finding.

5 Can formalism help to overcome limited commitment

is-sues?

This sub-section investigates how informal groups overcome the limited commitment problems they are exposed to. To do so, we exploit group variations in the scope and intensity of social connectedness among group members. In particular, we run the following OLS regression (1) using group-level data6 :

HF = ↵0+ ↵1Average SC + ↵2Average SC squared + G

0

+ X0+ "i (1)

where the dependent variable (HF) is a dummy taking value 1 if the financial group is highly formalized, that is if the group fulfills at least two of the three following criteria: having written rules, imposing sanctions for delay and/or absence, and having a bank account, and 0 otherwise.

Results are presented in Table 4. Average social connectedness is the main regressor of interest. We add its squared term to test the quadratic relationship between average social cohesion and formalization. Other regressors at the group level (vector G) include the size of the group, the length of affiliation and the main function of the group (insurance or rosca). In column 2, we add a set of individual characteristics (vector X) that are known to affect group membership: age, sex, ability to read and durable goods. A table of summary statistics of the control variables used in the regressions can be found in Table 2. In column 3 to 6 of Table 4, we change the measure of the average social connectedness variable according to the four alternative definitions (SC1, SC2, SC3 and SC4) presented in section 3.2. Standard errors are systematically clustered at the village level in all specifications.

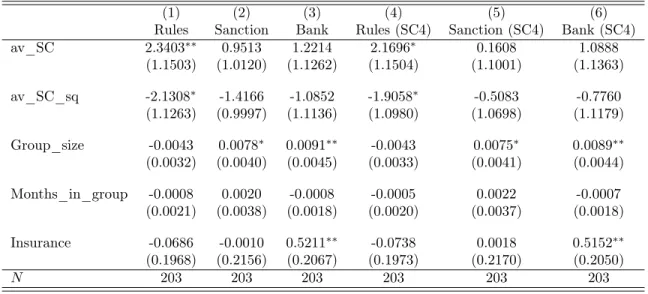

If Anderson and Francois (2008)’s claim is true, we should observe a higher degree of formal-ization within groups displaying strong average social connectedness. As can be seen in Table 4,

Table 4: High formalism and average SC: ME after Probit

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) HF HF HF (SC1) HF (SC2) HF (SC3) HF (SC4) av_SC 2.4338⇤⇤ 2.6185⇤⇤ 2.1458⇤⇤ 2.0888⇤⇤ 1.8450⇤ 2.3597⇤⇤ (1.0753) (1.0756) (1.0374) (0.9368) (0.9787) (1.1984) av_SC_sq -2.6643⇤⇤ -2.7691⇤⇤⇤ -2.2155⇤⇤ -2.3697⇤⇤ -2.1561⇤⇤ -2.3733⇤⇤ (1.0664) (1.0596) (1.0243) (0.9415) (0.9853) (1.1621) Group_size 0.0047 0.0045 0.0045 0.0044 0.0044 0.0046 (0.0032) (0.0034) (0.0032) (0.0032) (0.0032) (0.0032) Months_in_group 0.0005 0.0005 0.0010 0.0008 0.0008 0.0008 (0.0024) (0.0025) (0.0024) (0.0024) (0.0024) (0.0024) Insurance -0.2240 -0.2830 -0.2476 -0.2238 -0.2174 -0.2441 (0.1988) (0.2041) (0.1962) (0.1960) (0.1919) (0.1981)

Individual Controls NO YES NO NO NO NO

N 203 203 203 203 203 203

Marginal effects; Standard errors, clustered at the village level, in parentheses Individual Controls include Able to read, Age, Sex, log of assets

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1.⇤p < 0.10,⇤⇤ p < 0.05,⇤⇤⇤p < 0.01

although all variables of social connectedness are positively correlated with formalism, there is a nonlinear and non-monotonic relationship between both variables. Indeed, Figure 2 plots the aver-age social connectedness function as reported in column 1 of Table 4, with an exponential quadratic specification. It indicates a clear inverted U-shape pattern as the level of formalization is near 0 at the extremes, and significantly positive (reaching a maximum of almost 0.55) near the middle. In other words, the stringency of formalism is the highest for intermediate values of average social

Figure 2: Inverted U-shape of SC

cohesion, that is, when a moderate fraction of people know each other well but is less connected with the rest of the group. One plausible explanation for this result is that, when average social connectedness is intermediate, indicating that some group members maintain close relations with each other while being unfamiliar to the rest of the group, there is a serious risk of favouritism or opportunism on the part of the members who are interpersonally connected. This reasoning will be thoroughly discussed in the last Section.

Table 5: Distinct measures of formalism and average SC: ME after Probit

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Rules Sanction Bank Rules (SC4) Sanction (SC4) Bank (SC4)

av_SC 2.3403⇤⇤ 0.9513 1.2214 2.1696⇤ 0.1608 1.0888 (1.1503) (1.0120) (1.1262) (1.1504) (1.1001) (1.1363) av_SC_sq -2.1308⇤ -1.4166 -1.0852 -1.9058⇤ -0.5083 -0.7760 (1.1263) (0.9997) (1.1136) (1.0980) (1.0698) (1.1179) Group_size -0.0043 0.0078⇤ 0.0091⇤⇤ -0.0043 0.0075⇤ 0.0089⇤⇤ (0.0032) (0.0040) (0.0045) (0.0033) (0.0041) (0.0044) Months_in_group -0.0008 0.0020 -0.0008 -0.0005 0.0022 -0.0007 (0.0021) (0.0038) (0.0018) (0.0020) (0.0037) (0.0018) Insurance -0.0686 -0.0010 0.5211⇤⇤ -0.0738 0.0018 0.5152⇤⇤ (0.1968) (0.2156) (0.2067) (0.1973) (0.2170) (0.2050) N 203 203 203 203 203 203

Marginal effects; Standard errors, clustered at the village level, in parentheses

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1. ⇤p < 0.10,⇤⇤p < 0.05,⇤⇤⇤p < 0.01

To better understand this result, Table 5 further decomposes formalization by type of formal rules. The dependent variables are now dummies equal to 1 respectively if the group has written rules (columns 1 and 4), if it imposes sanctions in case of delay and/or absence (columns 2 and 5),

or if the group has a bank account (columns 3 and 6). Regressors are identical to those of regression (1), average social connectedness reported in columns 1 to 3 is measured according to our basic definition, and we relax the definition of social connectedness to SC4 in columns 4 to 67.

The key finding is that written rules seem to be driving the previous results. The absence of significant coefficients for sanctions and bank accounts is not surprising due to the aforementioned shortcomings of these indicators of formalism. Recall that sanctions indicate whether there is a fine in case of delay or absenteism whereas we would have liked to capture sanctions in case of non-payment of the due contributions. Similarly, we pointed out that bank accounts are closely related to the type of group considered. Indeed, almost no rosca uses such facility since the pot is systematically held by one of its members. In other words, the distinction between groups that deposit the communal money on a bank account and the other is only relevant for insurance groups. Therefore, we are not surprised to see no effect from social connectedness when both types of groups are taken together. Instead, the content of written rules encompasses those different dimensions of formalism and is therefore the most appropriate component of the index of formalism.

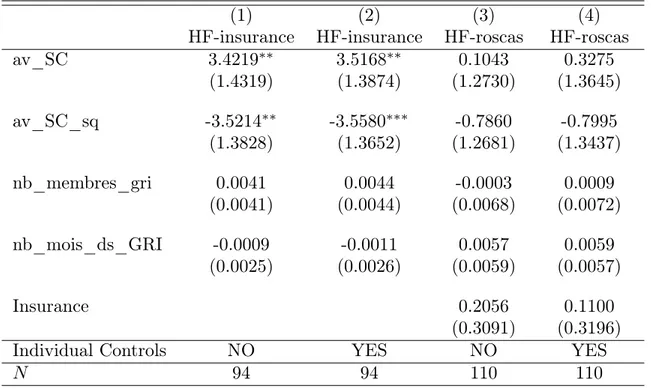

In addition, Table 6 distinguishes groups by the main function they offer: roscas (110 groups) or insurance services (94 groups). This distinction allows us to observe a significant influence of the average social connectedness on formalization only for groups offering insurance services.

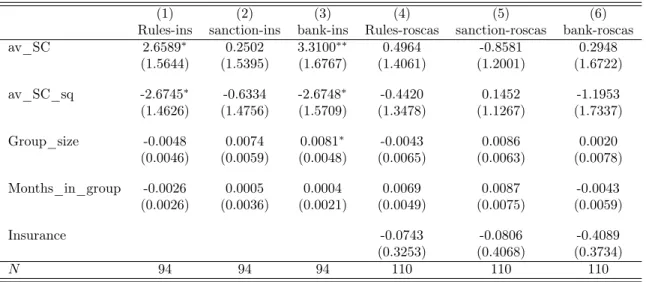

Finally, in Table 7 , high formalism is decomposed by type of rule and we continue to differenti-ate insurance groups and roscas. Here again, the strength of social connectedness among members significantly influences the level of formalization applied in the group only for groups offering in-surance services, through rules and the deposits on a bank account. Recall that the distinction between groups with or without a bank account makes sense for insurance groups only. As will be discussed in details in the last Section, we argue that the difference observed by type of group is linked to the greater risk of factional opportunism in insurance groups, where the mode of operation is more discretional.

6 An alternative measure for Social Connectedness :

Hetero-geneity in origin

In the absence of precise measures of the relationships between group members, empirical studies typically rely on indicators of homogeneity in origin to measure social connectedness. For instance, in their study of various US localities, it has been argued by Alesina and La Ferrara (2000b) that “more homogeneous communities have a higher level of social interactions leading to more social capital”. Similarly, Bold and Dercon (2014) note that “Households with stronger ties in the community, stronger ties in the group, and less mobility are more likely to make reliable members

7Note that results are similar for the alternative measures of social connectedness SC1, SC2 and SC3 (not reported

Table 6: High formalism by type of group: ME after Probit

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

HF-insurance HF-insurance HF-roscas

HF-roscas

av_SC

3.4219

⇤⇤3.5168

⇤⇤0.1043

0.3275

(1.4319)

(1.3874)

(1.2730)

(1.3645)

av_SC_sq

-3.5214

⇤⇤-3.5580

⇤⇤⇤-0.7860

-0.7995

(1.3828)

(1.3652)

(1.2681)

(1.3437)

nb_membres_gri

0.0041

0.0044

-0.0003

0.0009

(0.0041)

(0.0044)

(0.0068)

(0.0072)

nb_mois_ds_GRI

-0.0009

-0.0011

0.0057

0.0059

(0.0025)

(0.0026)

(0.0059)

(0.0057)

Insurance

0.2056

0.1100

(0.3091)

(0.3196)

Individual Controls

NO

YES

NO

YES

N

94

94

110

110

Marginal effects; SE clustered at the village level in parentheses Individual Controls include Able to read, Age, Sex, log of assets

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1. ⇤ p < 0.10, ⇤⇤ p < 0.05, ⇤⇤⇤ p < 0.01

of insurance arrangements because they are more amenable to social and reputational pressure. Conversely, such members may also find it easier to enforce contract rules against others who do not comply.” Therefore, we test, in this section, the robustness of our results to the use of homogeneous groups in terms of origin as a proxy for social connectedness between individuals8.

6.1 Link between social connectedness and place of birth

Prior to the replication of the regressions exploring the relationship between formalization and place of birth, we briefly focus on statistics describing the link between social connectedness and

8Note that a lot of previous works have looked at heterogeneity in ethnicity (Anderson and Francois (2008);

Stolle et al. (2008); La Ferrara (2002); Alesina and La Ferrara (2000b)). We can not replicate these results since we were not allowed to ask the respondent’s ethnicity in the aftermath of the genocide. Similarly, trust is commonly used as a way to proxy social connectedness (Haddad and Maluccio (2003); Alesina and La Ferrara (2000a); Knack and Keefer (1997)). Though we have both survey and experimental data on trust, it concerns only the respondent and not all group members. Because of this data limitation, we were not able to construct an average level of trust within groups to explore the validity of this variable.

Table 7: Distinct measures of formalism by type of group: ME after Probit

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Rules-ins sanction-ins bank-ins Rules-roscas sanction-roscas bank-roscas

av_SC 2.6589⇤ 0.2502 3.3100⇤⇤ 0.4964 -0.8581 0.2948 (1.5644) (1.5395) (1.6767) (1.4061) (1.2001) (1.6722) av_SC_sq -2.6745⇤ -0.6334 -2.6748⇤ -0.4420 0.1452 -1.1953 (1.4626) (1.4756) (1.5709) (1.3478) (1.1267) (1.7337) Group_size -0.0048 0.0074 0.0081⇤ -0.0043 0.0086 0.0020 (0.0046) (0.0059) (0.0048) (0.0065) (0.0063) (0.0078) Months_in_group -0.0026 0.0005 0.0004 0.0069 0.0087 -0.0043 (0.0026) (0.0036) (0.0021) (0.0049) (0.0075) (0.0059) Insurance -0.0743 -0.0806 -0.4089 (0.3253) (0.4068) (0.3734) N 94 94 94 110 110 110

Marginal effects; Standard errors, clustered at the village level, in parentheses

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1.⇤p < 0.10,⇤⇤p < 0.05,⇤⇤⇤p < 0.01

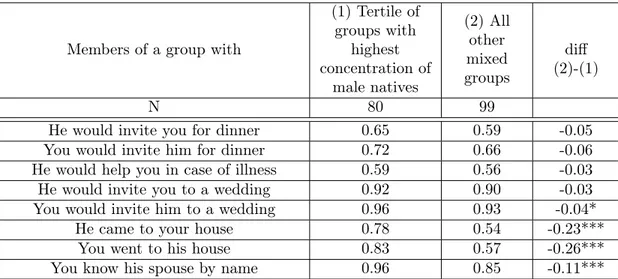

the place of birth of the different group members. Table 8 compares the social connectedness variables for the upper tertile of groups composed predominantly of male natives9, with the average

proportions for the 75% of mixed groups 10 with the lowest concentration of native men. The

differences between both groups are computed in column three.

Interestingly, Table 8 reveals only a few significant differences between groups mostly formed by male natives and those formed predominantly by non-natives. Indeed, apart from the lower percentage of members that have already visited each others at home in groups with a majority of non-native male members and the slightly better knowledge of the name of the other members’ close relatives, Table 8 indicates no significant difference in social connectedness between both types of groups11. In short, based on the descriptive statistics, it is not clear whether place of birth is an

appropriate proxy for social connectedness. Note however that, at this point, we do not control for confounding factors. That will be dealt with in the next section.

6.2 Formalization and heterogeneity in origin

We now explore whether the functioning of those groups significantly differs, and, in particular, if the rules are stronger than in the groups hosting a majority of village natives.

9Since it is the custom for Rwandan women to follow their husband after the marriage, being a non-native women

is thus very common and confounding both effects would be complex to interprete.

1024 observations have been deleted since those groups were exclusively composed of female members 11Results are qualitatively similar when other cut-offs are considered: quartiles, median.

Table 8: Average SC and place of birth

Members of a group with

(1) Tertile of groups with highest concentration of male natives (2) All other mixed groups diff (2)-(1) N 80 99

He would invite you for dinner 0.65 0.59 -0.05

You would invite him for dinner 0.72 0.66 -0.06

He would help you in case of illness 0.59 0.56 -0.03

He would invite you to a wedding 0.92 0.90 -0.03

You would invite him to a wedding 0.96 0.93 -0.04*

He came to your house 0.78 0.54 -0.23***

You went to his house 0.83 0.57 -0.26***

You know his spouse by name 0.96 0.85 -0.11***

In columns one to three of Table 9, groups are sorted according to the percentage of native men and column 1 presents the upper tertile of this classification12. The figures reported in column three

thus compare the level of formalization between groups predominantly composed of male natives with more heterogeneous groups in terms of origin. We observe that groups with the highest concentration of male natives are significantly more likely to accept new members (76% vs 58%) and, at the same time, fewer applicants are refused (23% vs 32%). In addition, the amount of entry fees is higher, though less often required, than in heterogeneous groups.

Overall, it seems that groups hosting a majority of male natives tend to set up less barriers to entry in the group. Nonetheless, the comparison of means reported in Table 9 does not highlight any significant differences in terms ofwritten rules and sanctions. Hence, the descriptive statistics is inconclusive regarding the potential presence of complementary features between the homogeneity in place of birth and the degree of formalization applied in the groups.

In order to control for potential confounding factors, we now formally run a regression, replacing the social connectedness variable of our main specification with the percentage of male natives in the group.

HF = ↵0+ ↵1P ct male native + ↵2P ct male native squared + G

0

+ X0+ "i (2)

As already mentionned, we restrict the natives to men only as it is the tradition in Rwanda for women to follow their husband once married. Being a non-native women is thus very common and confounding both effects would be complex to interprete. The variable Pct male native is

Table 9: Formalism and place of birth: descriptive statistics

Members of a group

with

(1) Upper Tertile

concentration of

male natives

(2) All other

mixed

groups

diff

(2)-(1)

N

80

99

Entry fees (dummy)

0.25

0.34

0.09*

Amount entry fees

3128

1270

-1857*

Discussion about

newcomer

0.41

0.38

-0.03

Refusal new member

0.23

0.32

0.10*

Entry new members

0.76

0.58

-0.19***

Exclusion of a member

0.19

0.18

-0.01

Written rules

0.69

0.68

-0.01

Sanction for absence

0.83

0.76

-0.07

Bank account

0.31

0.29

-0.02

constructed by dividing the number of male members who were born in the village by the total number of men in that group. Results are reported in Table 10. As in regression (1), we add the quadratic term in the even columns (2 and 4) to control for non linearities. Control variables at the group level (vector G) include group size, length of membership and function of the group. In column 3 and 4 of Table 10, additional personal characteristics (vector X) are included in the regression. Standard errors are clustered at the village level.

The signs of the coefficients ↵1 and ↵2, reported in specifications (2) and (4), are consistent

with the results obtained through the use of the average social connectedness variable (see Table 4). However, the absence of statistical significance for the coefficients of interest indicates that the observed relationship between the stringency of formalism and the average social connectedness would not have been detected using the place of birth as a proxy for social connectedness. As we argued above, homogeneity in origin is a very rough proxy of social connectedness within group members. Overall, this points to the need for a more detailed measure of interpersonal links within groups.

7 Discussion and concluding remarks

One of the key questions for the formation and management of financial groups in an environment of limited commitment is whether to impose rules and sanctions or trust in the cooperative behaviour of all group members (Das and Teng (1998)).

Table 10: Formalism and Place of birth: ME after Probit (1) (2) (3) (4) HF HF HF HF pct_male_native -0.0841 1.5656 -0.1048 1.5877 (0.2478) (1.0842) (0.2561) (1.1014) pct_male_native_sq -1.5664 -1.5965 (1.0398) (1.0402) Group_size 0.0079⇤⇤ 0.0088⇤⇤ 0.0086⇤⇤ 0.0094⇤⇤ (0.0038) (0.0039) (0.0040) (0.0041) Months_in_group -0.0010 -0.0013 -0.0009 -0.0012 (0.0025) (0.0025) (0.0024) (0.0024) Insurance -0.1532 -0.1692 -0.1759 -0.1879 (0.2248) (0.2190) (0.2298) (0.2266)

Individual Controls NO NO YES YES

N 179 179 179 179

Marginal effects; Standard errors, clustered at the village level, in parentheses Individual Controls include Able to read, Age, Sex, log of assets

(d) for discrete change of dummy variable from 0 to 1

⇤p < 0.10,⇤⇤ p < 0.05,⇤⇤⇤p < 0.01

In their seminal paper, Anderson and Francois (2008) develop a model to analyse the conditions under which formalism is used to help govern the relationships within the group. According to their model’s predictions, social cohesion among members of the same ethnicity should increase the degree of formalism applied in the group. Their findings contrast with most of the existing literature on this point and disclose a negative side of social capital. The underlying mechanism is that, when people know each other well, they are difficult to discipline and the cost of conflict resolution is high. Indeed, they model punishment as representing a loss not only to the recalcitrant member but also to the other members of the financial group. The authors posit that without a minimum level of formalism, it is extremely difficult to commit to the punishment of deviant members in very cohesive groups and, hence, to induce cooperative behaviour and reach efficient conflict resolution in groups with strong kinship ties. In other words, formalism can be used as a way to credibly enforce punishment. They confirm their theoretical prediction using data from Kibera slum (Kenya), but it is noteworthy that the way they measure social connectedness is through the use of an ethnic variable. Their assumption is, indeed, that groups of homogeneous ethnic structure are presumably rich in social ties.

When these social ties are measured more directly, by means of a composite variable depict-ing social familiarity, we observe a more complex relationship between social connectedness and

formalization level. The existence of a monotonic and linear increase in formalism along with the strength of social cohesion is rejected and, instead, we find an inverted-U relationship. Yet, in order to interpret the role of social connectedness, it is important to stress that average social connect-edness is also an indicator of homogeneity in the group. It is, indeed, a measure of the scope of interpersonal connections within the group. At the one extreme, when nobody knows any other group member personally in the group, the average social connectedness variable equals 0. At the other extreme, when all participants maintain close relations with every other group member, the variable is equal to 1. Between these extreme values, groups are heterogeneous in their average social connectedness level in the sense that some group members maintain close relationships with others while being unfamiliar to the rest of the group. Our evidence therefore suggests that formal-ism may be a response to situations in which some members of the group have strong interpersonal connections while others do not. In other words, it is in intermediate situations that formalization is most commonly observed.

A plausible explanation of this finding is that, when social connectedness is fragmented or polarized, there is a serious risk of favouritism or opportunism on the part of the members who are interpersonally connected. They would thus behave as a faction or coalition bent upon defending the interests of the other members regardless of the interests of the whole group. Hence, the need to control for this risk by establishing rules that apply uniformly to all members. Among these rules are, for instance, compulsory ex-ante payments in the shape of insurance premiums. On the contrary, when all members are on an equal footing, either because they all know and frequent each other or because they are relatively unrelated to each other, there is no such need for disciplining rules.

But our results also show that the inverted U shape of the relationship between high formalism and average social connectedness is clearly observed only for insurance groups. In roscas, by con-trast, no such relationship is discernible. The apparent reason for the difference is the following: while, by definition, roscas follow procedures and rules - the mechanism of rotatory access to a common pot, in particular - that even if they are not written are well known and well accepted by all those who wish to participate, insurance groups function according to more loosely defined principles and are therefore more vulnerable to opportunistic behaviour. As a consequence, it is in the latter groups that rules are more particularly required to make up for flexible principles of operation, at least if trust is not well established among members. And if group-level trust is espe-cially weak when social connectedness is polarized, giving rise to the risk of factional opportunism, it is then that formalism should be expected to be most important.

Though our discussion on the specific role endorsed by informal groups should provide a useful starting point, we believe it would be worthwhile to deeper investigate the mechanisms through which heterogeneity in intensity of social connectedness influences the degree of formalism within groups. This would, however, require a detailed and rigorous qualitative analysis for which

References

Aghion, P., Algan, Y., and Cahuc, P., A. S. (2010). Regulation and distrust. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3):1015–1049.

Alesina, A. and La Ferrara, E. (2000a). The determinants of trust. NBER Working Papers. Alesina, A. and La Ferrara, E. (2000b). Participation in heterogeneous communities. The quarterly

journal of economics, 115(3):847–904.

Anderson, S. and Baland, J. (2002). The economics of roscas and intrahousehold resource allocation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3):963–995.

Anderson, S., Baland, J.-M., and Moene, K. O. (2009). Enforcement in informal saving groups. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1):14–23.

Anderson, S., Baland, J.-M., and Moene, K. O. (2010). Sustainability and organizational design in informal groups, with some evidence from kenyan roscas. Technical report, Technical Report 17, Department of Economics, University of Oslo.

Anderson, S. and Francois, P. (2008). Formalizing informal institutions: Theory and evidence from a kenyan slum. Institutions and Economic Growth, pages 409–451.

André, C. and Platteau, J. (1998). Land relations under unbearable stress: Rwanda caught in the malthusian trap. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 34(1):1–47.

Ardington, C. and Leibbrandt, M. (2004). Financial services and the informal economy. CSSR and SALDRU.

Barr, A. and Genicot, G. (2008). Risk sharing, commitment, and information: an experimental analysis. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(6):1151–1185.

Bénabou, R. and Tirole, J. (2005). Incentives and prosocial behavior. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Berg, E. (2014). The puzzle of funeral insurance.

Bold, T. and Dercon, S. (2014). Insurance companies of the poor.

Bonleu, A. (2014). Procedural formalism and social networks in the housing market.

Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (1998). The moral economy of communities: Structured populations and the evolution of pro-social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19(1):3–25.

Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (2004). Persistent parochialism: trust and exclusion in ethnic networks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(1):1–23.

Claibourn, M. and Martin, P. (2000). Trusting and joining? an empirical test of the reciprocal nature of social capital. Political Behavior, 22(4):267–291.

Dagnelie, O. and Lemay-Boucher, P. (2012). Rosca participation in benin: A commitment issue*. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 74(2):235–252.

Das, T. and Teng, B. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooper-ation in alliances. Academy of management review, pages 491–512.

Dercon, S., De Weerdt, J., Bold, T., and Pankhurst, A. (2006). Group-based funeral insurance in ethiopia and tanzania. World Development, 34(4):685–703.

Dercon, S., Hoddinott, J., Krishnan, P., and Woldehanna, T. (2008). Collective action and vulner-ability: Burial societies in rural ethiopia.

Durlauf, S. N. and Fafchamps, M. (2005). Social capital. Handbook of economic growth, 1:1639–1699. Falk, A. and Kosfeld, M. (2006). The hidden costs of control. The American economic review,

pages 1611–1630.

Fehr, E. and Rockenbach, B. (2003). Detrimental effects of sanctions on human altruism. Nature, 422(6928):137–140.

Godquin, M. and Quisumbing, A. (2006). Groups, networks, and social capital in the philippine communities. CAPRi working papers.

Greif, A. and Tabellini, G. (2012). The clan and the city: Sustaining cooperation in china and europe. Available at SSRN 2101460.

Gugerty, M. K. (2007). You can not save alone: Commitment in rotating savings and credit associations in kenya. Economic Development and cultural change, 55(2):251–282.

Guseva, A. and Rona-Tas, A. (2001). Uncertainty, risk, and trust: Russian and american credit card markets compared. American Sociological Review, pages 623–646.

Haddad, L. and Maluccio, J. (2003). Trust, membership in groups, and household welfare: Evidence from kwazulu-natal, south africa*. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51(3):573–601. Handa, S. and Kirton, C. (1999). The economics of rotating savings and credit associations: evidence

Hayo, B. and Vollan, B. (2012). Group interaction, heterogeneity, rules, and co-operative behaviour: Evidence from a common-pool resource experiment in south africa and namibia. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(1):9–28.

Jakiela, P. and Ozier, O. (2012). Does africa need a rotten kin theorem? experimental evidence from village economies.

Jalan, J. and Ravallion, M. (1999). Are the poor less well insured? evidence on vulnerability to income risk in rural china. Journal of development economics, 58(1):61–81.

Kedir, A. M. and Ibrahim, G. (2011). Roscas in urban ethiopia: Are the characteristics of the institutions more important than those of members? Journal of Development Studies, 47(7):998– 1016.

Kimuyu, P. K. (1999). Rotating saving and credit associations in rural east africa. World Develop-ment, 27(7):1299–1308.

Knack, S. and Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? a cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112(4):1251–1288.

La Ferrara, E. (2002). Inequality and group participation: theory and evidence from rural tanzania. Journal of Public Economics, 85(2):235–273.

Levenson, A. R. and Besley, T. (1996). The anatomy of an informal financial market: Rosca participation in taiwan. Journal of Development economics, 51(1):45–68.

Malhotra, D. and Murnighan, J. (2002). The effects of contracts on interpersonal trust. Adminis-trative Science Quarterly, 47(3):534–559.

Narayan, D. and Pritchett, L. (1999). Cents and sociability: Household income and social capital in rural tanzania. Economic development and cultural change, 47(4):871–897.

Nguyen, Q. (2009). Present biased and rosca participation: Evidence from field exper-iment and household survey data in vietnam. Workshop Lyon-Toulouse BBE (Behav-ioral?and?Experimental?Economics).

Nzisabira, J. (1992). Les organisations populaires du rwanda: leur émergence, leur nature et leur évolution. Bulletin de l’APAD, (4).

Peterlechner, L. (2009). Roscas in uganda-beyond economic rationality?-. African Review of Money Finance and Banking, pages 109–140.

Rietz, T., Schniter, E., Sheremeta, R., and Shields, T. (2012). Trust, reciprocity and rules. Available at SSRN 1923831.

Ring, P. and Van de Ven, A. (1994). Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Academy of management review, pages 90–118.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, Mass.

Sitkin, S. and Roth, N. (1993). Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic remedies for trust/distrust. Organization science, 4b(3):367–392.

Stolle, D., Soroka, S., and Johnston, R. (2008). When does diversity erode trust? neighborhood diversity, interpersonal trust and the mediating effect of social interactions. Political Studies, 56(1):57–75.

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embed-dedness. Administrative science quarterly, pages 35–67.

Vollan, B. (2008). Socio-ecological explanations for crowding-out effects from economic field exper-iments in southern africa. Ecological Economics, 67(4):560–573.

Zaheer, A. and Venkatraman, N. (2007). Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strategic management journal, 16(5):373–392.

Zucker, L. (1986). Production of trust: Institutional sources of economic structure, 1840–1920. Research in organizational behavior.

Table 11: Review of the effect of income/wealth on membership

Dependent

variable Explanatory variable Coefficient Paper Country Non FG Log of real income 0.074 Alesina and

La Ferrara (2000b) US Food

consumption Income percentile Jalan and Ravallion(1999) China

ROSCA Income + Kedir and Ibrahim

(2011) Ethiopia ROSCA Individual income, expenditures

on non-durable goods 0.008, + Lemay-Boucher (2012)Dagnelie and Benin ROSCA Per capita expenditures in t-1 + Haddad and Maluccio

(2003) South Africa ROSCA Iron sheet roof/salaried job 0.73 Gugerty (2007) Kenya Fixed rosca Relative income (less present

biased) and income (not ***) +1.51*,0.002 Nguyen (2009) Vietnam ROSCA Total income (female share of

income), food expenditures + Anderson and Baland(2002) Kenya ROSCA Percentile rank of the hh’s

income + Levenson and Besley(1996) Taiwan ROSCA Log of expenditures + Kimuyu (1999) Tanzania &

Kenya Burial

society Assets and expected income shapedhump- Berg (2014) South Africa Burial

society Log income + butsmall Leibbrandt (2004)Ardington and South Africa Burial

society Landholdings and livestockunits + butsmall Dercon et al. (2008) Ethiopia Burial

society Assets-rich + Quisumbing (2006)Godquin and Philippines Income Participation in groups + Haddad and Maluccio

(2003) South Afric