HAL Id: dumas-01730954

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01730954

Submitted on 13 Mar 2018HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Neural correlates of post stroke depression

Fanny Riggi

To cite this version:

Fanny Riggi. Neural correlates of post stroke depression. Human health and pathology. 2018. �dumas-01730954�

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le

jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la

communauté universitaire élargie.

Il n’a pas été réévalué depuis la date de soutenance.

Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci

implique une obligation de citation et de référencement

lors de l’utilisation de ce document.

D’autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite

encourt une poursuite pénale.

Contact au SID de Grenoble :

bump-theses@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

LIENS

LIENS

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10

http://www.cfcopies.com/juridique/droit-auteur

Année : 2018 N°

NEURAL CORRELATES OF POST STROKE DEPRESSION

CORRELATS NEURONAUX DE LA DEPRESSION APRES UN

ACCIDENT VASCULAIRE CEREBRAL

THÈSE

PRÉSENTÉE POUR L’OBTENTION DU TITRE DE DOCTEUR EN MÉDECINE DIPLÔME D’ÉTAT

Fanny RIGGI

Thèse soutenue publiquement à la faculté de médecine de Grenoble le 09/03/2018 devant le jury composé de : Président : Assesseurs : Directrice de thèse : Pr. Marc HOMMEL Pr Mircea POLOSAN Dr Olivier DETANTE Dr Isabelle FAVRE-WIKI Dr. Assia JAILLARD

L’UFR de Médecine de Grenoble n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les thèses ; ces opinions sont considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs.

UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES UFR DE MÉDECINE DE GRENOBLE

Remerciements

A mon jury,

A Monsieur le Professeur Marc HOMMEL,

Vous me faites l’honneur de présider ce jury, veuillez trouver ici l’expression de mes sincères remerciements et de mon respect.

A Monsieur le Professeur Mircea POLOSAN,

Je vous remercie de me faire l’honneur de juger ce travail. Merci pour votre enseignement au cours de mon semestre en psychiatrie, pour vos conseils et votre soutien. Merci pour votre bonne humeur lors de nos matinées partagées au bloc à faire des ECTs.

A Monsieur le docteur Olivier DETANTE,

Je suis honorée que tu aies accepté de faire partie de mon jury de thèse. Merci pour ton humanité, ta disponibilité, tes grandes leçons de neurologie vasculaire et de philosophie. Pour ta sincérité aussi, et pour m’avoir aidé à trouver en moi les réponses sur mon avenir.

A Madame le docteur Isabelle FAVRE-WIKI,

Je te remercie d’avoir accepté de participer à ce jury. Merci pour m’avoir guidée dans mes 1ers pas d’interne, pour m’avoir appris la rigueur. Merci aussi pour tous tes conseils, ta motivation, tes débriefs, ton dynamisme. Bien sûr merci pour tout ce que tu m’as appris et que tu

m’apprends encore. C’est probablement à toi que je dois en partie mon gout pour la neurologie vasculaire.

A Madame le docteur Assia JAILLARD, la source de ce travail. Merci pour toutes les longues heures que vous m’avez accordées tout au long de ces 2 années, pour votre grande disponibilité, merci pour tous les cafés et les douceurs chocolatées. Grâce à vous j’ai pu entrevoir ce qu’était la recherche, que d’ascenseurs émotionnels. Merci pour ce que vous m’avez appris en neurologie, en anatomie, en statistiques et en logiciels divers et variés. Pour tout ce que cette aventure professionnelle m’aura appris sur moi-même, et pour toutes nos conversations informelles qui m’auront aidé à savoir ce que je voulais faire de ma future carrière.

A mes collègues, mes maitres, tous ceux qui m’ont entouré et encadré au cours de mon internat,

A Katia, merci pour ta bonne humeur malgré les innombrables bips de certaines journées interminables. Pour tout ce que tu m’as appris, et que tu m’apprends encore. Pour tes conseils et pour avoir toujours été une oreille bienveillante. Merci pour ton soutien précieux dans les moments plus difficiles.

A Anne-Sophie, merci pour ta super pédagogie, ton dynamisme et ta disponibilité. Tu auras représenté un modèle au cours de mon internat. La crème qui fait tout le gout des épinards. A Mathieu, merci pour être toujours là pour répondre à mes questions, pour ton soutien, tes conseils, ta réassurance.

A Olivier Casez, le papa de la neurologie et surtout des internes, merci pour ton enthousiasme et ta motivation.

Au Dr Besson, pour sa générosité.

A Hannah, grâce à toi la recherche de K-complexes, spindles et le moyennage rétrograde devenaient amusants, malgré l’absence de fenêtre. Merci pour ta bonne humeur et les bons moments partagé.

A Tarek, merci pour avoir partagé tes 1er pas de chefs avec mes 1eres heures d’interne, mes histoires de natrémie et de tiques. Merci pour les cafés !

Merci à ceux qui me supportent ce semestre, pour vos conseils, votre disponibilité et enseignements précieux dans la bonne humeur et la bienveillance. Philippe, questions épilepsie ou techniques de lestage dans l’Isère je m’enrichis chaque jour. Lorella, pour ton tiramisu fabuleux, et ton efficacité. Une pensée pour Murielle, j’aurai eu la chance de profiter de ton organisation au poil et ta bonne humeur pendant 1 an et demi.

A tous les séniors de la neurologie grenobloise et annecienne, aux équipes de

neuroradiologie et de psychiatrie, pour votre enseignement, vos conseils et votre temps.

A Maryse, le rayon de soleil de la neurovasculaire, toujours un plaisir de te croiser en garde. A Nadia, merci pour ton soutien et ta motivation lors de mon 1er semestre.

A mes mamans du 4em, Delphine, Martines, Aline, Armelle, Anne, merci pour ces 6 mois géniaux, sans vous le 4em n’aurait pas laissé le même souvenir.

A tous les technicien(ne)s, infirmier(ère)s, ASH, aides soignant(e)s, kinés, orthophonistes,

A mes amis,

A Maya, avec qui j’ai partagé mes premiers pas en médecine, mais aussi les souvenirs les plus forts d’une vie. Pour ton regard bienveillant et motivant tout au long de ces années. Pour être là toujours là, malgré la distance. Avec une pensée pour sœur Annie… .

A Estelle bien-sûre, les piliers, les hippies, les skateuses, les gymnastes, les cuistots, les danseuses, les randonneuses et tant encore... Quelques mots ainsi écris suffisent à m’accrocher un sourire pour tous les souvenirs que cela évoque, et des années après

m’entrainer toujours dans de grands fous rires. Quelques lignes ne suffiront pas, il faudrait un roman.

A Quentin, un ami au combien précieux, toujours présent et depuis toujours. Ce n’était pas gagné, et qui sait peut être un jour quand même l’IUFM.

A Marine, toujours là, déjà 16 ans, en collants à fleur ou en congrès de neurologie. Merci pour ton soutien, ton aide, tes conseils, ta droiture. Une amie comme on en a peu. Des professeurs aux pantalons trop relevés, des attentes de résultats, en passant par nos vacances, les WE d’intégrations et les annales bien sûre! Et cette route partagée lors de notre migration du nord au sud, je te revois encore sur l’aire d’autoroute. Merci pour tout ce qu’on a déjà partagé, pour tout ce qu’on partage et vivement la suite !

A Anne T, un brevet, un bac, maintenant une thèse et Taizé attend toujours…mais heureusement, il est des amitiés qui survivent à tous les kilomètres.

A Laura, merci de m’expliquer inlassablement l’ECG, pour ton gout de la découverte, pour avoir toujours été motivée à me suivre dans mes expériences et m’avoir entrainé dans les tiennes. A nos longues heures de révisons, qui ont valu le coup. A nos carrés de chocolat et finalement la tablette, à nos films à l’eau de rose, à notre parfaite oreille musicale, à nos concerts en voiture, à nos fous rires. Pour être toujours là, moralement et physiquement, bien que tu aies posé tes valises en Haut de France ! Une pensée pour Carlos, alias Titi.

A Simon, Bouzy, Bouzette. Pour avoir été et être toujours là pour répondre à mes questions existentielles sur les TCA, pharmacocinétique et autres choses du genre. Pour ton oreille attentive, sans jugement, pour nos confidences partagées, pour ta confiance. Pour faire que les choses soient toujours pareilles, même avec la distance. Pour être un ami précieux. Merci aussi pour m’avoir fait découvrir le Bento, une valeur sûre !

A Justine, la Rousse, un rayon de soleil au foyer, mon binôme sur les bancs de la fac et à la BU, et surtout une amie précieuse. La boucle est presque bouclée et tu auras tout partagé. A Claudine, pleine d’idées originales ou carrément farfelues. Une amie en or, toujours présente. Merci pour toutes ces années, et pour toutes les futures.

A Mathieu et Angélique, une de mes plus belle rencontre sur les bancs de la fac. Je ne n’oublierai pas ce qu’on a partagé et ce que vous avez fait pour moi. Pour être un peu ma famille Ardennaise. Merci Angélique pour tes conseils cuisine, ta philosophie de vie

tellement apaisante. Mathieu, à nos gardes, nos repos de garde, nos soirées, nos terrasses, nos vins chauds, nos ballades, nos innombrables conversations, nos pâtes mille fromages, et tous les souvenirs qui en découlent. Merci pour ta présence à mes cotés dans les bons et les mauvais moments durant ces 10 dernières années. Une tendre pensée pour Philomène.

A Aline, Amélie, Morgan, Elo, Natho, Vincent, Mathilde, Bouli, Max, Jéjé, Mathieu,

Leslie, Freddy, Virgile, Florian, Anne-Sophie…et à tous les copains de fac, pour nos bons

moments.

A la team des copines de 1er semestre, et finalement beaucoup plus. A Alison, ma pédiatre préférée, merci pour ton soutien inébranlable, ta droiture et ta générosité. A Marie, pour tous nos bons souvenirs à la colloc’, pour nos consultations vertiges à deux cerveaux, pour m’avoir fait découvrir le théâtre et partager tous ces bons moments avec moi. A Camille TV, présente dans toutes les circonstances, même les plus incongrues sur un parking dans la montagne, pour avoir été une colloc’ bordélique mais formidable. A Wassima, pleine de vie et de bonne humeur, footing ou sortie, toujours un plaisir. Merci pour notre complicité et vivement la suite !

A Joris, une magnifique rencontre Grenobloise, merci pour ta tolérance, ta bonne humeur, ton ouverture d’esprit !

A Giovanni, co-interne, mais surtout ami. Merci pour tous tes bons conseils, en tout genre et sur tous les sujets ;) . Pour être une oreille attentive, et ma calculette, pour nos fous rires. Merci pour ton soutien durant la rédaction de ce travail et tout au long de notre internat. A Anne, co-interne de choc en premier semestre, et finalement amie. Merci de toujours veiller à mon estomac avec tes petits plats, pour toutes tes attentions si gentilles, ta générosité, et ton soutien dans la rédaction de ce travail et au cours de notre internat.

A Gérald et Vera, les acolytes de la team « DV forever », pour avoir rendu ce semestre d’été 2017 inoubliable. Pour tester avec moi ma liste des restaurants de Grenoble, et pour tous nos cafés-potins, pourvu que ça dure !

A tous les copains d’internats, à Lisa, Davy, Eliott, Camille, Sarah, Arthur S et A, Yohan,

Marine B, Morgane, Fred, Julien, Marion, Laurent, Romain, Cécile, Adèle, Anne, Hubert, Jean-Charles, Albane. Pour notre 1er semestre de folie, pour tous les autres et pour toutes nos soirées, Merci à Céline ;) .

A mes supers co-internes de neurologie. Sébastien, la force tranquille, c’est grâce à toi que j’ai fais mes valises pour Grenoble, merci ! Pauline, merci pour ton soutien, les heures de révisions et les recettes partagées. Jérémie avec qui j’aurais bien rigolé. Nastasia, pour ta sincérité et ta force de caractère, admirable. Marie pour nos soirées escalades, avec le spécialiste ! Hélène pour ta générosité et ta bonne humeur. Guillaume le hippie en peignoir toujours souriant. Thomas, acolyte de ma pause du jeudi, toujours sympathique. Sarah, la rêveuse. Lucie pour les bons moments partagés. Hugo, on attend toujours la soirée galette !

Loïc, calme mais efficace, qui reprend gentiment la casquette de délégué de classe. Et aux

plus jeunes Inès, Florent et Gauthier (ou Guillaume) qui écrieront la suite.

A Anaïs, co-interne d’un semestre, mais pas des moindre ! Sans oublier le Pr Bailleul, soutien précieux. A Eléa et Louise, des résidentes en or. Une mention spéciale pour Clémentine, il me tarde de choisir notre peinture et notre machine à café, à un futur prometteur.

A ma famille bien sûr,

Maman, chose promise chose due. Mon modèle de vie, ma bonne étoile, mon ange gardien.

C’est à toi tout particulièrement qu’est dédiée cette thèse, pour tout ce qu’elle représente. Avec ton mon amour.

A Philippe. Merci papa, merci pour tout. Comme à chaque point clé de mon parcours je me

tourne vers toi et te témoigne ma reconnaissance pour ton soutien, tes conseils et ta présence tout au long de mon chemin personnel et professionnel quelques soient les difficultés

rencontrés. Merci pour m’avoir appris les maths, la physique, les stats, la montagne, la vie. Merci d’avoir toujours témoigné un intérêt pour mes projets. Merci pour tous ceux que tu as partagé. A nos longues heures à chercher notre chemin, aux kilomètres de course parcourus ensemble, à tous nos sommets gravis, aux dégaines perdues, à tous nos souvenirs passés, en attendant tous les futurs.

A mes grands parents. Merci à Mamie et Papi, sans qui ma vie aurait été différente. Merci de tout ce que vous avez fait pour moi, de ce que vous avez sacrifié. Merci d’avoir toujours été là pour faire qu’on ne manque de rien, et surtout pas d’amour. Une tendre pensée pour Mamie, ma deuxième maman, tu avais prévu être là aujourd’hui, malheureusement tu t’es envolée vers d’autres aventures. A mes deux petites abeilles, que j’ai quotidiennement dans mes pensées. Merci à Mamilou, pour nos longues heures de conversations philosophiques, pour nos confidences, pour tes conseils, précieux dans ma vie, pour me rappeler l’importance des relations humaines dans mon métier, et pour avoir toujours su prendre du recul, tu es pour moi un modèle de vie. A la mémoire de Papilou.

A Vincent, parmi l’un de ceux qui comptent le plus, pour tous nos souvenirs fraternels, nos grandes aventures, et les moments forts partagés. « Inférieur à trois ».

A Anne, une cousine extraordinaire, ma petite sœur de cœur. Merci pour ta relecture attentive, in English bien sûre. A nos expériences, à nos voyages. Merci d’avoir toujours été une oreille attentive et le coffre fort de mes confidences.

A Martine et Philippe, pour avoir toujours été là, et m’avoir traité comme leur fille, vous faites parti de ce que j’ai de plus cher. Pour tous nos bons moments passés aux Etats-Unis. A Marie –Hélène, pour avoir suivi de loin ce projet, et avoir toujours été persuadée que j’y arriverai. La chambre d’amie t’attend toujours.

Aux Courtois-Ratti, et Marc pour tous les bons moments partagés, pour toutes nos aventures durant ces 2 dernières années, gâteaux caramel ou banane et tartes aux prunes. Merci pour toutes les bouffés d’air très précieuses passés en votre compagnie à Nantes, Lovagny, Rumilly, Albens, Paris, Avallon, la Réunion. En espérant qu’il y en ait plein d’autres.

Bien évidement à Gautier, ma plus belle rencontre. Je te remercie infiniment pour ta patience tout au long de ce travail, ta compréhension aussi. Pour son soutient dans ma vie

professionnelle et personnelle. Merci pour tout ce que l’on construit ensemble et qui rend la vie plus belle. Merci d’être mon GPS, ma mémoire, mon radiateur… ma moitié. Merci de partager ton chemin avec le mien, à notre futur et tous nos projets.

Table of contents

Remerciements ... 5 Table of contents... 10 ABSTRACT ... 11 1 INTRODUCTION... 12 1.1 Background ... 12 1.2 Risk factors of PSD ... 13 1.3 Pathophysiology of PSD ... 15 2 OBJECTIVES... 183 MATERIAL AND METHODS... 19

3.1 Participants ... 19

3.2 Depression assessment ... 21

3.3 Imaging procedures ... 22

3.4 Voxel-Based Lesion–Symptom Mapping ... 24

3.5 Resting state functional MRI study (rs-fMRI) ... 26

3.6 Statistical analysis ... 28

4 RESULTS... 30

4.1 Patient characteristics... 30

4.2 VSLM... 33

4.3 Logistic regression model ... 37

4.4 Resting state connectivity of the PSD lesion ... 38

5 DISCUSSION ... 42

5.1 Patient characterization ... 42

5.2 VSLM... 44

5.3 Logistic regression model ... 44

5.4 Caudate nucleus and depression... 45

5.5 PSD and corticostriatal circuits ... 47

5.6 The medial-dorsolateral caudate as a strategic region for PSD ... 54

5.7 Lesion side and depression... 56

5.8 Methodological considerations ... 57

5.9 General considerations and perspectives... 60

6 CONCLUSION... 62

ABSTRACT

Post stroke depression (PSD) occurs in one third of patients and increases the

socio-professional reintegration challenge. There are two majors aetiology: reactional and biological theory with PSD as consequence of the brain lesion itself. Several locations were found with controversial results. We assume that neural substrates of PSD belonging to frontal–

subcortical circuits relevant for cognition and behaviour. Our aim was to determine PSD neural correlates in young patients, 3 to 18 months after a first ever stroke demonstrating in MRI. First we characterized the profile of PSD patients. Second, we analyse the statistical relationship between tissue damage and PSD using a voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Third, we modelled PSD to determine independent predictors. Fourth, we explored the

networks connected with the PSD lesion using a resting state functional MRI (rs-fMRI). Forty six percent of our 59 patients were classified as depressed using the Beck Depression

Inventory Fast-Screen ≥4. PSD was significantly more frequent in patients with formal house helpers, social adaptation impairment, work and social dysfunction and trouble in

instrumental activities of daily living. PSD was significantly associated with a lesion within right dorsal caudate overlapping the lateral part of the medial and the ventral part of the lateral regions (ml-rDC) that is the only one significant independent factor and was connected to the 3 emotion-related fronto–subcortical circuits in rs-fMRI. The ml-rDC appears as a key region in the upward spiral model of limbic, cognitive and motor circuits, leading to impair the cognitive contextual reappraisal of data from limbic structures.

Key-word:depression, stroke, caudate, fronto-striatal circuits, VSLM, resting state.

RESUME

Après un accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) la dépression (PSD) survient chez un tiers des patients altérant la réintégration socio-professionnelle. Il y a 2 grandes étiologies :

réactionnelle et biologique où la PSD est une conséquence de la lésion cérébrale. Plusieurs localisations ont été mises en évidence avec des résultats contradictoires. Nous supposons que le substrat neuronal de la PSD se situe dans les circuits frontaux-sous corticaux (FSC)

impliqués dans la cognition et le comportement. Notre objectif était de déterminer les corrélats neuronaux de la PSD chez de jeunes patients, 3 à 18 mois après un premier AVC confirmé par une IRM. Nous avons étudié le profil des patients PSD, puis analysé la relation statistique entre les lésions ischémiques et la PSD en utilisant une technique de cartographie par voxel. Ensuite nous avons modélisé la PSD pour déterminer les facteurs prédictifs et explorer les réseaux connectés avec la lésion relative à la PSD en IRM fonctionnelle (IRM f). Quarante six pourcent de nos 59 patients étaient déprimés sur l’échelle de Beck «

Fast-screen ». La PSD était significativement plus fréquente chez les patients ayant des dysfonctions sociales et des altérations des activités de la vie quotidienne. La PSD était significativement associée à une lésion dans le caudé dorsal droit, chevauchant la partie latérale du segment médial et la partie ventrale du segment latéral (ml-rDC), qui était le seul facteur prédictif indépendant, connecté aux 3 circuits FSC. Le ml-rDC apparaît comme une région clé dans la spirale liant les circuits limbique, cognitif et moteur, menant à une altération de la contextualisation cognitive des données émotionnelles.

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

Background

Stroke is a common and serious illness. Annual incidence in France is estimated at 150 000 (Lecoffre et al., 2017). On average, 1 out of 5 women and 1 out of 6 men have a stroke in their lifetime (Seshadri and Wolf, 2007) and 6 million people die of a stroke annually in the world. Stroke is the first cause of handicap acquired during adulthood, the second cause of dementia and the third cause of death after cardiovascular disease and cancer. During the acute phase, the severity of the disease is related to cardiac failure, brain stem lesion, and cerebral oedema. During the chronic phase, stroke severity is related to handicap. Post-stroke neurological recovery, based on angiogenesis, neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, is often insufficient to achieve full recovery and up to 50 % of victims are left with motor and/or cognitive impairments after stroke (Lecoffre et al., 2017). Motor, sensitive and sensorial deficits are often brought to the forefront when evaluating handicap, but cognitive, mood, behavioural impairments and social adaptation impairments are also commonly observed after stroke (Hommel et al., 2009; Jaillard et al., 2009).

Among above troubles, post stroke depression (PSD) is a common feature occurring in about one third of patients (Hackett et al., 2005). PSD is observed from a few days up to several years after stroke onset (Dennis et al., 2000) with a prevalence peak between three and six months (Whyte and Mulsant, 2002). Patients with PSD usually suffer from mild depressive syndrome (Herrmann et al., 1998).

1.2

Risk factors of PSD

While stroke is mostly related to cardiovascular risk factors and thus occurs mainly in the elderly, 25% of patients are under 65 years of age (Leys et al., 2002; Marini et al., 1999). The prevalence is increasing in this group of age all around the world (Tibaek et al., 2016) (Rosengren et al., 2013). In this active part of the population, the consequences of disability are more severe, in particular for socio-professional reintegration. Indeed, PSD is associated with poor motor recovery, cognitive dysfunction and low quality of life (Guiraud et al., 2016) as well as with a higher mortality rate (Robinson and Jorge, 2016).

A number of factors are correlated with the occurrence of PSD (for details, see Table 1). Their respective implication on PSD varies across studies. Overall, reviews on PSD have showed that neurological severity, physical disability, social support, female gender and stroke or depression history are the strongest predictors of PSD (Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009). Otherwise, white matter lesions, cerebral microbleeds and cortical atrophy are also reported as predictors of PSD. As these factors are frequent in most of the studied populations, because stroke patients are often in their second half period of life, they could be considered as confounding factors of PSD (Robinson et al., 1987).

Table 1: Factors correlated with the occurrence of PSD.

Factors References

Stroke neurological severity evaluated by the National Institute of Health Stroke Score (NIHSS)

(Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2014; Vataja et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2016).

Degrees of physical handicap measured by the Barthel Index or the Rankin score

(Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Parikh et al., 1987; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; Vataja et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2016). Quality of the environment and social

support (Parikh et al., 1987; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009). Alteration of daily activities (Parikh et al., 1987)

Previous negative life stories and marital

status (Herrmann et al., 1998)

Stroke history, recent negative life events (Santos et al., 2009) Chronic comorbidity (Shi et al., 2014) Active smoking at the time of stroke (Shi et al., 2015)

Ethnic origin (Goldmann et al., 2016)

Age

(Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015; Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Parikh et al., 1987; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009)

Gender (Female)

(Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2014)

Sleep disturbance (Santos et al., 2009)

Cognitive handicap

(Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015; Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2014)

Depression antecedent

(Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; Schottke and Giabbiconi, 2015; Shi et al., 2014)

Alteration of white matter

(Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015; Vataja et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016)

In contrast, PSD may occur in isolation, as highlighted in a case report (Biran and Chatterjee, 2003) describing an 80 years-old man who suddenly became apathetic, irritable and sad, with anosognosia. His troubled behaviour was just reported by his family. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) examination led to reveal a cerebral infarction in the internal capsule. In that case, depression was the only symptom of stroke. Moreover mice models with PSD (created

by local injection of vasoconstrictor peptides in the prefrontal cortex) become depressed and anxious without any motor or other somatic deficit (Vahid-Ansari et al., 2016). Of note, anosognosia doesn’t protect from PSD (Carota et al., 2005). And depression is more significantly higher after stroke than after others diseases with comparable disability (Burvill et al., 1997). All these findings suggest that depression may be the consequence of brain lesions and that stroke location should be considered.

1.3

Pathophysiology of PSD

PSD pathogenesis is based on two theoretical models that are the "biological" model related to lesion location and the "reactionary" model related to psychosocial vulnerability occurring in reaction to the stress induced by disability and related to the degree of handicap (Burvill et al., 1997; Dennis et al., 2000; Desmond et al., 2003). Others support a bio-socio-psychological model, mixing the biological and reactionary theories (Whyte and Mulsant, 2002). While no correlation between lesion location and PSD was found in several studies (Carson et al., 2000; Desmond et al., 2003; Herrmann et al., 1998; Paolucci et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2015), various lesion locations have been related to PSD as a consequence of the interruption of functional networks implicated in mood and emotional regulation, including the following cerebral structures:

Frontal lobes (Metoki et al., 2016; Parikh et al., 1987; Shi et al., 2014), Internal capsule (Shi et al., 2014; Vataja et al., 2001),

Right and left caudate nucleus (Metoki et al., 2016; Vataja et al., 2001), Amygdala (Vataja et al., 2001),

Right temporal lobe(Metoki et al., 2016), Putamen (Metoki et al., 2016),

Meta-analyses have also showed contradictory features. While one found no support for linking the lesion location and PSD (Carson et al., 2000), another recent meta-analyse found that frontal and basal ganglia lesions are risk factors of PSD, but only at the subacute phase of stroke (Douven et al., 2017). However, methodologies are heterogeneous in terms of sample (hospitalized or outpatients, inclusion and exclusion criteria), evaluation of time after stroke, depression scales, lesion location identification (MRI or computerized tomography scan), stroke type and prevalence of depression (range 17 to 79% in literature), leading to controversial results.

For some authors, acute PSD could be a transient reaction to the stroke, with higher rate of recovery than chronic PSD, which may reflect neuropathological changes secondary to the stroke (Robinson et al., 1987). Stroke survivors who have depression onset seven weeks or later after stroke have a lower rate of spontaneous recovery (Andersen et al., 1995). Therefore, studying chronic stroke is more relevant to determinate PSD correlates. However, data on chronic PSD is lacking.

In the view of the biological model theory, the cerebral regions listed above belong to the fronto-cortico-basal ganglia circuits that play a key role in cognitive and affective behaviours (Gunaydin and Kreitzer, 2016). According to the classical multiple parallel frontal-sub cortical circuit models proposed by Alexander and al. (Alexander et al., 1986), these regions belong to the three loops that are relevant for cognition and behaviour: the limbic or ventrostriatal circuit, the lateral orbitofrontal circuit and the dorsolateral prefrontal circuit. Vataja et al. in a large-scale MRI study of PSD in 275 hospital-based ischemic stroke survivors, found that the pallidum was an independent predictor of PSD, supporting the hypothesis that prefrontal-sub cortical circuit disruption is associated with PSD (Vataja et al.,

2004). The latter theory is also supported by Tang et al. (Tang et al., 2011), although no specific structure was identified in their study.

To our knowledge, no study has evaluated neural substrates of PSD, at the chronic stage of stroke, in a young and active population excluding confounding factors such as white matter lesions and cortical atrophy. In this work, we hypothesized that neural substrates of PSD are lying in the cortico-basal ganglia circuit. Furthermore, we investigated the loops that are involved in PSD and whether specific regions within these loops play a key role in PSD.

2

OBJECTIVES

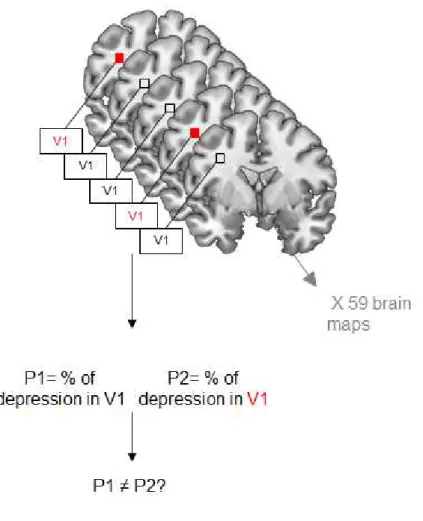

The aim of this study was to determine neural correlates of PSD in active and young patients with a first stroke using voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VSLM) method. We used VSLM because it is a method based on a voxelwise approach with an independent test computed for every voxel of the whole brain. Compared to predefined anatomical regions of interest commonly used in other studies, VSLM offers the advantage of a better spatial resolution and is typically better suited when there is not a strong a priori prediction regarding the spatial location of the critical lesion (Rorden et al., 2007).

To determine the anatomical structures associated with PSD, we proceeded in four steps.

• First, we characterized the profile of PSD patients in our population.

• Second, we used VSLM method to analyse the relationship between tissue damage and PSD.

• Third, to determine the predictive role of anatomical lesion in PSD, we modelled PSD using a linear regression analysis with anatomical regions provided by the VSLM analysis and risk factors of PSD as cofactors.

• Finally, we explored the networks connected with the PSD lesion using a resting state functional MRI study based on a ROI-based approach in 66 healthy participants.

To limit biases related to PSD, patients with major clinical risk factors of PSD such as residual neurological deficit, physical disability, prior stroke, cognitive impairment, white matter lesions, and history of major depression, were excluded. We included non-demented actives patients with a first ever stroke resulting in mild neurological deficit and under 65 years of age. To avoid the effect of reactional depression observed during the acute phase of stroke, patients were included after a delay of 3 months after stroke onset.

3

MATERIAL AND

METHODS

3.1

Participants

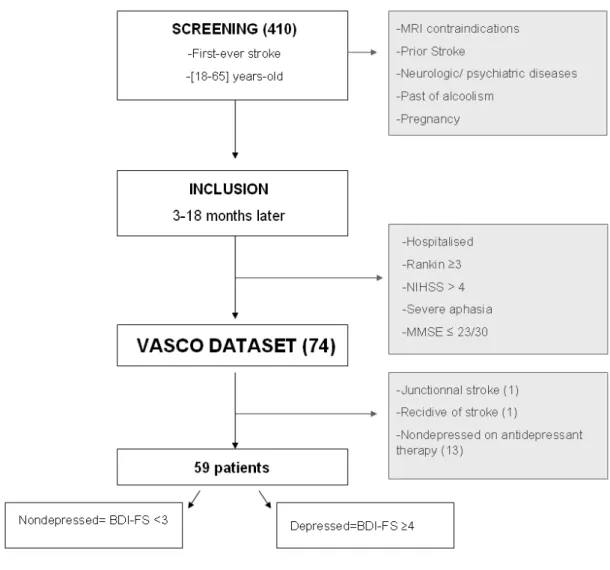

We selected our sample from the “evaluation of the social cognition after stroke or herpetic encephalitis” study (VASCO) (Hommel et al., 2009). In this study, 74 patients with chronic stroke were prospectively enrolled. The VASCO study was conducted in the university health centre (CHU) of Grenoble-Alpes from January 2005 to May 2006. Patients were screened if they fulfilled the following criteria: first-ever stroke demonstrated on MRI, age 18-65 (corresponding to working age). Patients with MRI contraindication, prior stroke defined as symptomatic or silent stroke, and leukoaraiosis or brain atrophy on imaging, other neurological disease, psychiatric disorder, past of alcoholism, and pregnancy were excluded. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (NIHSS) was used to assess neurological severity at the screening and follow-up visits (Brott et al., 1989). At the screening visit 3 to 18 months after their strokes, patients exhibiting a NIHSS >4, NIHSS subscore ≥ 2 for aphasia, a modified Rankin scale (van Swieten et al., 1988) ≥ 3 and a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) score ≤ 23/30 were excluded. Participants who could not perform the tests because of illiteracy or visual impairment were also excluded. The remaining population constituted the VASCO dataset.

The follow-up visit was performed 3 to 18 months after stroke for all patients. Personal, demographic and social characteristics (age, sex, manual laterality, school level, professional and marital status), need of home helpers and prescription of rehabilitation, anxiolytic and antidepressant therapies were collected. Social readaptation was subjectively recorded by the

neurologist with a 3-level score: none, moderate, and severe dysfunction. Autonomy was estimated through the instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADLs) (Lawton and Brody, 1969), including eight binary rated items: use of phone, shopping, cooking, housework, laundry, transportation type, medication and finances management. A score of 8 indicates normal activity. Self-evaluation of work and social dysfunction scale (WSAS) was administered to assess return to work, home management, social leisure, private leisure and ability to form and maintain close relationships with others. WSAS score ranges from 0, normal functioning, to 40. Anxiety was assessed with the subscore of hospital anxiety and depression scale (HAD) (Seshadri and Wolf; Zigmond and Snaith, 1983), normal score under 7, maximal score is 21. Executive function was evaluated with the Trail Making Test (TMT) part A for attention and part B for executive control (Reitan, 1955), alphabetical fluency (P letter), Stroop test, Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) London tower test . Spatial and working memory was evaluated with the CANTAB Owen spatial working memory test (Owen et al., 1990) and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test ( PASAT )( see (Jaillard et al., 2009) for details).

Importantly, among the VASCO participants, non-depressed patients treated with antidepressant were eventually excluded, because they could not be ranked as either depressed or not depressed. Anti-depressant was given to promote motor recovery (Chollet et al., 2011), and patients typically received fluoxetine at a dose of 20 mg per day. The remaining participants constituted the target population in which this work was performed (Figure 1).

The Medical Ethics Committee (CCPRB) of the institution approved the study. All participants have given their consent.

Figure 1: Flow chart.

3.2

Depression assessment

The assessment of depression was performed at the chronic stage of the disease to be remote from the reactional depression related to the subacute phase of stroke, and to evaluate mood when patients return to their social habits. Several tools are used to measure PSD (Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015). We used the Second Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), a popular scale that was used in more than 7000 publications (Wang and Gorenstein, 2013) and is validated in stroke (Turner et al., 2012). This self-administered questionnaire, consisting of 21 questions

scored from 0 to 3, covers all diagnostic criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) for characterized depressive disorder. Its sensibility is high (from 72% to 100%) and it is a reliable indicator of the severity of symptoms and suicidal thoughts. Four depressive symptom clusters derived from the BDI have been conceptualized as negative cognitions, psychomotor- anhedonia, vegetative, and somatic symptoms (Dunn et al., 2002).

Here we selected a subscale, the Beck Depression Inventory Fast-Screen ( BDI-FS), which aims to reduce the number of false positives by excluding symptoms that are not specifically related to PSD, such as fatigue that is commonly observed after stroke (Vahid-Ansari et al., 2016). BDI-FS consists of items 1 to 4 and 7 to 9 of the BDI-II: sadness, pessimism, past failure, loss of pleasure, negative feelings, critical attitude towards oneself and suicidal ideas. The maximum score is 21. The manual suggests that scores ranged 0-3 indicate minimal depression; 4-6 indicate slight depression; 7-9 indicate moderate depression; 10-21 indicate severe depression(Metoki et al., 2016). To use a binary variable, the validated cut-off score of 4 is recommended due to the high sensibility and specificity (0.7) and the good convergence with DSM-4 evaluation (0.66, P < 0.001)(44). Accordingly, patients were divided into two groups: depressed (BDI-FS ≥4) and non-depressed (BDI-FS <3).

3.3

Imaging procedures

MRI was performed on a Philips 1.5 Tesla magnet with an 8-channel head coil within the first week following stroke and before screening time. Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion-weighted images, were collected in all participants to confirm the occurrence of a recent stroke and to exclude patients with previous stroke or with

leukoaraiosis. We excluded patient with leukoaraiosis if the total score of Schelten exceeded six (Scheltens et al., 1993).

The stroke lesion delineation was manually delineated in MRIcron (package Version 6. 2013 http://www.mricro.com) (Durelli et al.) by a stroke neurologist (M.H.) with neuroimaging expertise and unaware of the clinical findings. For ischemic stroke, FLAIR was used: 24 axial slices in the anterior commissure - posterior commissure line (AC-PC) orientation with the following parameters: Repetition Time (TR) =11.000ms; Echo Time (TE)=110msec, Inversion delay=2600 ms, thickness=5mm, no gap, Matrix=256x256. For hemorrhagic strokes, the lesion boundary was delineated using T2-Fast Field Echo (T2-FFE) images acquired using the same axial orientation, thickness and gap as the FLAIR images. Oedema around hematoma was not included in the lesion volume, as it resolves within a few weeks after stroke. For each patient, the lesion mask was superimposed on a coregistered T1 template in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using SPM12 (http://fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). As there is some evidence that cognitive and emotional processing might be lateralized (Beraha et al., 2012; Bruder et al., 2017), lesion masks were not flipped. For each patient, the mapping of the stroke lesion was visually checked by the rater M.H. to ensure that the contour of the lesion on the template images was identical to the lesion shown in the native space. Lesion volume was computed using normalized masks for each patient using the MRIcron ‘Statistics’ tool.

3.4

Voxel-Based Lesion–Symptom Mapping

VSLM analysis performed with MRIcron included three steps. First, an overlay of all lesion masks was created in MRIcron. It’s a map showing, for each voxel, the number of patients who had a stroke lesion in that voxel. Second, we computed an overlay map of all lesions in the PSD group and another one of all lesions in no-PSD group. The overlay of the 2 maps on a colour-coded map permits to compare damaged voxels in patients with and without PSD. Third, the statistical contribution of lesion location to PSD was tested using VSLM analysis, using the NPM (Non-Parametric Mapping) software implemented in MRIcron. VSLM technique statistically computes the proportion of damaged versus non-damaged tissue in each voxel and each group. Then, it compares the probability of PSD between the 2 groups for each voxel. The lesion is entered as an independent variable predicting behaviour. As a result, each voxel is assigned the value of the statistical test, the z-score, representing the probability that a lesion in the considered voxel is associated with PSD. Only the voxels that were damaged in at least 10% of the patients in each group, i.e. 6 patients per group, were included in the analysis. The resulting statistical map of the whole brain shows the voxels associated with PSD (Bates et al., 2003).

PSD is characterized by mild depression, resulting in a negative binomial distribution of the depression scores. In this case, using the Beck score as a continuous variable that implies the use of the linear model based on Gaussian distribution would be inappropriate. Moreover, the aim of this work was to compare depressed with non-depressed patients, without taking the degree of depression into account. Therefore, we used a binary variable to test the effect of lesion on PSD. In the VSLM analysis, to determine relationships between PSD and the location of stroke, we used the Liebermeister test, which is more sensitive than the chi-square test, as recommended in Rorden et al. (Rorden et al., 2007)

Figure 2: General principle of VSLM.

VSLM technique is a voxel-based approach requiring correction for multiple comparisons. However, because of the inherent spatial coherence of lesion maps, lesions tend to be formed of contiguous voxels, and the lesion status of a voxel is well predicted by that of its neighbouring voxels. Therefore, instead of Bonferroni correction, we used a nonparametric resampling approach that does not rely on assumptions about the spatial distribution of the dataset, as recommended in Kimberg et al. Here, to correct for multiple comparisons, we used a 5% family-wise error (FWE) threshold with 4000 permutations (Kimberg et al., 2007).

3.5

Resting state functional MRI study (rs-fMRI)

Sixty four healthy participants (age range 18 to 65 years; 41 males; all right-handed) were included in this study. All participants were right-handed (Edinburgh Handedness Inventory; Oldfield, 1971), had no general cognitive impairment, psychiatric or neurological disorder. All Participants provided written informed consent of participation in the context of the ISIS-HERMES (N=40; N° idRCB: 2007-A00853-50) and the ADV study (N=24; CPP N°: 2014-A00569-38).

For the details of the acquisition, preprocessing and processing steps, see Irina Gornuschkina’s dissertation (Gornuschkina, 2017). Briefly, MRI experiments were performed on a whole-body 3Tesla MRI (Philips Achieva) with 40mT/m gradient strength and a 32 channel head coil at CHU Grenoble-Alpes (Plateforme IRMaGe). The resting state sequence ( Echo Planar Image T2, EPI) lasted 13 min 40sec (400 volumes). The participants were instructed to relax but also to lie as motionless as possible, to keep the eyes open while fixating on a cross that was displayed on a screen outside the scanner and was visible for the participant using a mirror attached to the receiver coil. We used the following parameters: 36 axial slices (3.5 -mm-thickness with 0.25 mm gap) parallel to the bi-commissural plane (ascending order), 3*3*3.75 voxel size; echo-time = 30ms; repetition time = 2sec; field of view = 192 × 192 x 138.25mm. For the anatomical sequences, a T1-weighted high-resolution three-dimensional anatomical volume was acquired, by using a 3D sequence (TR = 9.9 ms; TE = 4.6 ms; field of view=256×224×176 mm; resolution: 1.333×1.750×1.375 mm; acquisition matrix: 192×128×128 pixels; reconstruction matrix: 256× 128×128 pixels).

Temporal and spatial preprocessing was performed using SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) implemented in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). All volumes were realigned to the mean volume to correct for head motion, by using a rigid body transformation. T1-weighted anatomical volume was co-registered to functional mean images created by the realignment procedure and was normalized into the MNI space. Each functional volume was smoothed by a Gaussian kernel of 8-mm FWHM (Full Width at Half Maximum). Finally, time series for each voxel were high-pass filtered (1/128 Hz cut-off) to remove low-frequency noise and signal drift. We used the seed-based correlation method with Connectivity toolbox (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto Castanon, 2012, http://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn, version 17a). As implemented in the connectivity toolbox, our analysis used a component-based noise correction method (aCompCor) which allowed removing physiological noise in the resting state signal. This method enhances the specificity and the sensitivity to positive correlations and avoids artifactual anti-correlations without global signal removal (Chai et al., 2012). Components of the signal from the white matter and cerebral spinal fluid were removed using an explicit mask together. Movement-related components and outliers identified using the Artifact Detection Tool (ART) toolbox were also removed. Functional images were then temporally band-pass filtered (0.01 < f < 0.1 Hz). For each participant we conducted a quality assessment at the denoising step by ensuring that all denoising histogram were centred to zero and showed normal Gaussian curves. We also visual inspected that movement parameters did not explained all the variance of signal measured at rest.

At the first-level analysis, correlations maps were calculated for each participant by extracting the mean signal time course from the seed and computing Pearson’s correlations coefficients with the time course of all other voxels of the brain. Those correlation coefficients were co

nverted to normally distributed z-scores using the Fisher transformation to allow for the second-level General Linear Model analyses. At the second-level analysis, we used a ROI (region of interest) to ROI analysis with the PSD lesion as the seed and the regions of the regions of the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas as the targets. A ROI to voxels analysis was also performed with the PSD lesion as the seed for graphical representation. From a conservative perspective, the statistical threshold was set at p=0.05 FWE to confirm evidence strong connections with the PSD lesion and at the usual p=0.05 false discovery rate (FDR) from an exploratory perspective.

3.6

Statistical analysis

Patient with and without PSD were compared with respect to stroke side, lesion volume, sex, manual laterality, education level, profession, NIHSS at admission and follow-up visit, Rankin score, rehabilitation, antidepressant and anxiolytic therapy, presence of house helpers, marital status, relationship issues, marital status before and after stroke, return to work after one year, anxiety, social adaptation trouble, IADLs, WSAS, TMT score, alphabetical fluency, Stroop test, CANTAB London tower test, CANTAB Owen spatial working memory test, PASAT and MMSE scores. Our variables distributions were studied using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and demonstrated abnormal distributions. The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were applied for compared categorical data, and the Mann-Whitney test was used for compared continuous data. The characteristics were considered different between two groups with a p < 0, 05.

Then, PSD was modelled using a logistic regression analysis to determine the independent predictors of PSD. The variables associated with PSD in bivariate comparisons at p < 0.20 were introduced in the model using a stepwise approach. We selected the most parsimonious

and efficient model, based on the number of factors, the efficiency of the model and the Nagelkerke R² coefficient of determination. We also checked for internal inconsistencies by examining the distribution of the residuals and looking for outliers. Finally, the internal validation of the model was tested using bootstrapping with 1000 replications (Steyerberg et al., 2010). The statistics were analyzed with IBM® SPSS® statistics release 20.0.0.

4

RESULTS

Among all 74 patients included in the VASCO study, 15 patients were excluded: one patient with a junctional stroke resulting in multiple lesions and one with a recurrent stroke between screening and inclusion time. We also excluded 13 patients who were not diagnosed as depressed under antidepressant. As a result, our studying population consisted of 59 patients, among which 27 (45, 8%) were depressed (BDI-FS ≥ 4) and 32 (54, 2%) were non-depressed (BDI-FS<4).

4.1

Patient characteristics

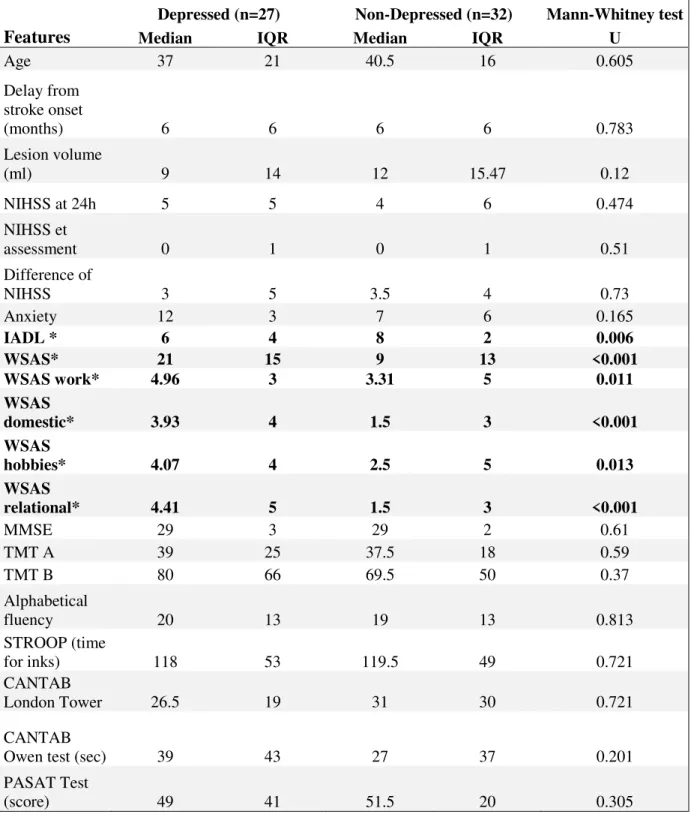

The median BDI-FS score in the population was 3, corresponding to minimal depression. Antidepressant was given to 18 (30.5%) patients and antidepressant therapy was significantly associated with PSD, which is self-evident because all patients receiving antidepressant were depressed. Patients’ characteristics bivariate comparisons are presented in Tables 1A (categorical data) and 1B (continuous data). PSD was significantly more frequent in patients with formal house helpers, social adaptation impairment, high WSAS (indicating work and social dysfunction) and low IADL scores (indicating trouble in instrumental activities of daily living). There was no significant difference regarding stroke side and subtype, delay from stroke onset to depression evaluation, sex, manual laterally, education level, occupation, lesion volume, acute and chronic NIHSS (and difference between them), the Rankin score, the anxiety scores, cognitive scores, rehabilitation, anxiolytic therapy, formal house helpers, single status before and after stroke, marital status before and after stroke, marital problems, anxiety, and return to work after one year.

Table 1A: Comparison of characteristics in depressed and non-depressed patients, categorical

data.

Characteristics Depressed(n=27) Non depressed (n=32) Fisher tests Chi²/Exact

n % n % p Male 13 59.4 19 48.1 0.388 Right-handed 25 92.6 28 87.5 0.678 Bachelor/University 15 50 16 55.6 0.670 Occupations subtype 0.115 Tradesmen/ Storekeeper/Business owner/Exempt/ Superior occupations 5 18.5 1 3.1 Associate professional/Employed/ Workers 16 59.3 25 78.1 No professional activity 6 22.2 6 18.8 Rehabilitation treatment 13 48.1 12 37.5 0.410 Rankin score R0/R1/R2 02/06/19 7.4/22.2/70.4 0/10/17 15.6/31.2/53.1 0.166 Anxiolytic treatment 4 80 1 20 0.173

Formal house helpers* 4 14.8 0 0 0,039

Formal house helpers 8 29.6 6 18.8 0.328

Single before stroke 1 3.7 6 18.8 0.112

Single after stroke 2 7.4 5 15.6 0.437

Marital status change 2 7.4 0 0 0.205

Marital problems 10 40 6 22.2 0.165

Social adaptation difficulties:

No/Moderate/Severe* 7/18/2 25.9/66.7/7.4 20/10/2 62.5/31.2/6.3 0.011

Right-sided stroke lesion 16 59 16 51 0.279

Return to work at 1 year 0.349

No prior activity 3 11.1 3 9.4

No return to work 14 51.9 10 31.2

Partial 3 11.1 3 9.4

Another work 0 0 1 3.1

Return to same work 7 25.9 15 46.9

Stroke subtype: ischemic/

Table 1B: Comparison of characteristics for depressed and non-depressed patients,

continuous data. IADL= instrumental activities of daily living scale; WSAS= Self-evaluation of work and social dysfunction scale; TMT= Trail making Test , A for attention and B for executive control; PASAT= Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; CANTAB= Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery; IQR indicates interquartile range.

Depressed (n=27) Non-Depressed (n=32) Mann-Whitney test

Features Median IQR Median IQR U

Age 37 21 40.5 16 0.605 Delay from stroke onset (months) 6 6 6 6 0.783 Lesion volume (ml) 9 14 12 15.47 0.12 NIHSS at 24h 5 5 4 6 0.474 NIHSS et assessment 0 1 0 1 0.51 Difference of NIHSS 3 5 3.5 4 0.73 Anxiety 12 3 7 6 0.165 IADL * 6 4 8 2 0.006 WSAS* 21 15 9 13 <0.001 WSAS work* 4.96 3 3.31 5 0.011 WSAS domestic* 3.93 4 1.5 3 <0.001 WSAS hobbies* 4.07 4 2.5 5 0.013 WSAS relational* 4.41 5 1.5 3 <0.001 MMSE 29 3 29 2 0.61 TMT A 39 25 37.5 18 0.59 TMT B 80 66 69.5 50 0.37 Alphabetical fluency 20 13 19 13 0.813 STROOP (time for inks) 118 53 119.5 49 0.721 CANTAB London Tower 26.5 19 31 30 0.721 CANTAB

Owen test (sec) 39 43 27 37 0.201

PASAT Test

(score) 49 41 51.5 20 0.305

4.2

VSLM

The lesion overlaying map for the whole group of 59 patients showed a maximum overlap in the right insula, temporal and occipital regions and striatum, within the Middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery territories (Figure 2).

The overlay maps for PSD and non-PSD patients are displayed in Figure 3. PSD patients’ lesions were more frequent in the bilateral posterior cingulate, precuneus and occipital cortex, and in the right head of the caudate nucleus, right medial thalamus and right amygdala. The results are summarized in a color-coded map on the MNI template brain using MRIcron software.

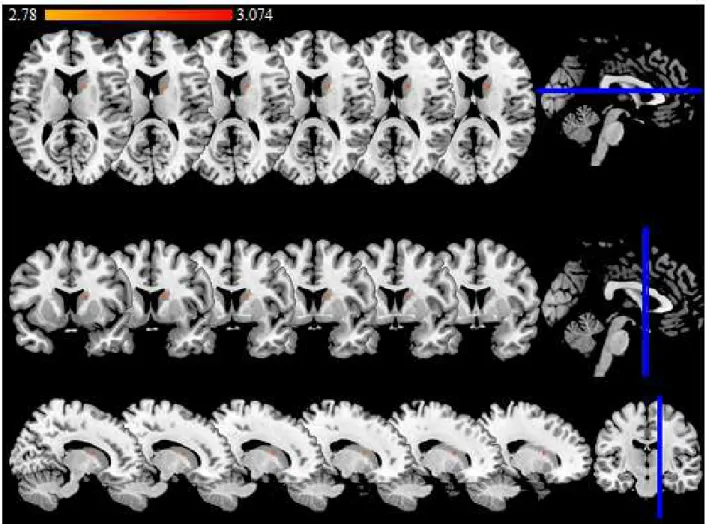

VLSM analysis showed that PSD was significantly associated with a lesion in the head of the right caudate nucleus (Z=2.78, 4000 permutations FWE, P=0.05). Using the May and Paxinos atlas (Hackett et al., 2005), the PSD-related lesion is located within the right dorsal caudate (volume 160 mm3), overlapping the lateral part of the medial (4 slices) and the ventral part of the lateral (2 slices) regions (Figure. 4).

Figure 2: Axial slices showing lesion overlapping map of 59 patients. Purple colour indicates the least number of overlap and red colour indicates the highest overlap. The right side of the brain corresponds to the right hemisphere (anatomical convention). Axial slices are presented in an ascending order according to MRIcron z coordinates: 0 ;60; 70;1 00; 120; 130; 140; 150; 170; 180; 190; 200; 210.

Figure 3: Overlap maps for depressed and non-depressed patients. Blue= Depressed; Red= nondepressed; Pink = Intersection between depressed and nondepressed. The right side of the brain corresponds to the right hemisphere (anatomical convention). Axial slices are presented in an ascending order according to MRIcron z coordinates (mm): 70; 105; 115; 135; 140; 155; 160; 170; 175; 186; 215; 235.

Figure 4: Significant lesion associated with PSD (BDI-FS≥4). The color scale indicates the Z

score. The threshold for statistical significance was Z=2.78 (4000 permutations FWE, P=0.05), and the maximum voxel value was Z=3.074. The right side of the brain corresponds to the right hemisphere (anatomical convention). Six axial slices (upper row), coronal slices (middle row) and sagittal slices (bottom row) are presented in an ascending order according to MNI (x; y; z) coordinates: (x=13;y=5;z=12), (x=14;y=6;z=13), (x=15;y=7;z=14), (x=16;y=8;z=15), (x=17;y=9;z=16), (x=18;y=10;z=17).

4.3

Logistic regression model

To determine whether clinical, anatomical and social factors are associated with PSD in our population, we run a logistic regression analysis with PSD as the dependent variable.

First, to detect significant predictors of PSD, a forward likelihood ratio (LR) method was used, with covariates that were associated with PSD with p value <0.20. We introduced the following covariates: right medial caudate damage the presence of formal house helpers, social adaptation impairment, IADL and WSAS scores, stroke subtype, lesion volume, profession, single status before stroke, marital status change after stroke, and marital problems, anxiety score of HAD, Rankin score, anxiolytic medication, CANTAB Owen test score. The effects of age and gender were also tested.

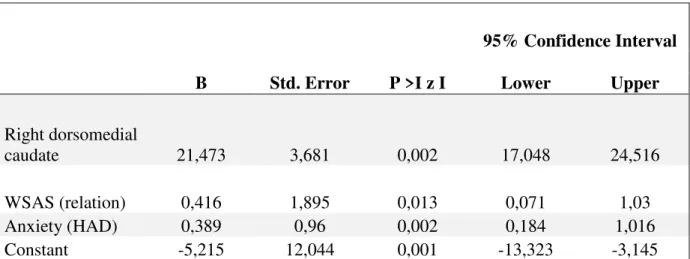

The resulting model identified the right medial caudate, the anxiety sub-score of HAD scale and the fifth item of the WSAS named ‘relationships with others’, as independent predictors of PSD, each accounting for 15.6%, 42.3% and 6.7% of the model variance respectively. The model explained 64.6% of the total variance using the Nagelkerke R2 (Cox and Snell R2 =0.484), with an efficiency of 79.66%. The residual curve showed a Gaussian distribution and there were no outliers. When testing our multivariate model with bootstrapping, the same predictors remained significant although the confidence intervals of B for the WSAS and anxiety exceeded 1.00 (Table 2). The right ‘PSD-lesion’ remained the only significant independent factor predicting PSD. The B values with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and significance (p values) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Multiple logistic regression, based on 1000 bootstrap samples.

95% Confidence Interval

B Std. Error P >I z I Lower Upper

Right dorsomedial

caudate 21,473 3,681 0,002 17,048 24,516 WSAS (relation) 0,416 1,895 0,013 0,071 1,03 Anxiety (HAD) 0,389 0,96 0,002 0,184 1,016 Constant -5,215 12,044 0,001 -13,323 -3,145

4.4

Resting state connectivity of the PSD lesion

Table 3 shows the list of the ROIs connected with the PSD-lesion seed at p< 0.05 FDR corrected. In bold, we indicated ROIs connected with PSD-lesion seed at p< 0.05 FWE ( t≥4.8), in a conservative perspective. In the ROI to ROI analysis, the PSD-lesion seed showed significant connections with the bilateral dorsolateral, dorsomedial and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate and the inferior orbitofrontal cortices, putamen, pallidum, thalamus, accumbens nucleus and amygdala. Positive connections were also significant at p<0.05 FDR corrected with the orbitofrontal, temporo-insular and posterior parietal regions, as well with the supplementary motor area and posterior cingulum. The map of the regions connected to the PSD-lesion (Figure 5), shows significant functional connectivity with the three emotion-related loops. The PSD-lesion was negatively correlated with the sensorimotor regions at p<0.05 FDR.

Table 3: List of the ROIs significantly connected with the lesion seed at p< 0.05 FDR

corrected. BA= Brodmann area.

Targets Beta (t) p-FDR

Thalamus ventral Anterior Left 0,11 11,9 <0,000001

Putamen Left 0,08 10,44 <0,000001

Putamen Right 0,09 10,03 <0,000001

Pallidum Left 0,1 9,43 <0,000001

Thalamus Prefrontal Right 0,07 8,91 <0,000001

Thalamus Right 0,07 8,83 <0,000001

Pallidum Right 0,1 8,72 <0,000001

Thalamus Prefrontal Left 0,05 7,76 <0,000001

Thalamus Left 0,05 8,06 <0,000001

Paracingulate Left 0,07 9,65 <0,000001

BA 47 Left 0,08 8,01 <0,000001

Paracingulate Right 0,09 7,94 <0,000001

Amygdala Right 0,08 7,76 <0,000001

Frontal Inferior Orbitary cortex Right 0,08 7,74 <0,000001

BA 47 Right 0,07 7,74 <0,000001

Frontal Inferior Operculum Right 0,08 7,6 <0,000001

BA 09 Right 0,06 7,53 <0,000001

BA 09 Left 0,07 7,52 <0,000001

Frontal Superior Med Left 0,09 7,21 <0,000001

Frontal Middle Left 0,07 7,11 <0,000001

Frontal Inferior Orbitary Left 0,08 7,08 <0,000001

Frontal Orbital Cortex left 0,07 6,99 <0,000001

Frontal Superior Med Right 0,1 6,98 <0,000001

Amygdala Left 0,09 6,89 <0,000001

Cingulum Ant Left 0,06 6,88 <0,000001

Cingulum Ant Right 0,07 6,82 <0,000001

Frontal Orbital Cortex Right 0,06 6,73 <0,000001

Frontal Middle Right 0,06 6,65 <0,000001

Frontal Superior Left 0,06 6,39 <0,000001

Frontal Pole Right 0,07 6,33 <0,000001

Frontal Pole Left 0,06 6,27 <0,000001

Frontal Inferior Triangularis Right 0,07 6,23 0,000001

Frontal Superior Right 0,05 6,05 0,000001

Accumbens Left 0,09 5,9 0,000001

Angular Left 0,09 5,64 0,000002

Frontal Inferior Operculum Left 0,06 5,64 0,000002

Accumbens Right 0,07 5,58 0,000003

BA 46 Right 0,07 5,44 0,000004

Frontal Inferior Triangularis Left 0,06 5,37 0,000005

Angular Right 0,07 5,35 0,000006

Amygdala Right 0,1 5,26 0,000008

Suplementary Motor Area Left 0,04 4,94 0,000025

Cerebelum Crus2 0,07 4,88 0,00003

Default Mode Network.Medial prefrontal cortex 0,09 4,8 0,000038

Accumbens Left 0,07 4,75 0,000045

Temporal Pole Superior Left 0,06 4,63 0,000063

Insula anterior Left 0,04 4,49 0,000104

Default Mode Network.LLP 0,09 4,47 0,000108

Temporal Pole Superior Right

Cerebellum Crus2 Right 0,06 4,32 0,000171

Thalamus Parietal Left 0,02 4,14 0,0003

BA 46 Left 0,05 3,9 0,000634

thalamus motor Right 0,04 3,84 0,000764

Cingulate Gyrus, anterior 0,03 3,46 0,002352

Cingulum Post Right 0,04 3,45 0,002417

Amygdala SF Right 0,09 3,45 0,00241

Cingulum Post Left 0,03 3,44 0,002444

Thalamus VP Left 0,02 3,44 0,002417

Frontal Med Orbitary Right 0,06 3,43 0,002475

Default Mode Network.RLP 0,06 3,42 0,002567

Cerebellum 7b Right 0,04 3,32 0,003322

Orbital frontal Cortex Fo3 Right 0,04 3,2 0,004678

Frontal Middle Orbitary Left 0,05 3,05 0,006938

Temporal Middle Right 0,02 3,03 0,007377

Temporal Middle Left 0,02 3,02 0,007586

Thalamus motor Left 0,03 2,91 0,009912

Temporal Pole Left 0,04 2,85 0,011645

Olfactory Left 0,02 2,84 0,011859

Frontal Medial Orbitary Left 0,04 2,81 0,012865

Frontal Middle Orbitary Right 0,06 2,81 0,012712

Thalamus Somatosensory Left 0,03 2,66 0,018164

Insula Right 0,02 2,53 0,024119

Figure 5: Axial slices (A upper rows) and coronal slices (B lower rows) showing the

ventro-dorsomedial, ventro-dorsolateral prefrontal and lateral orbitofrontal areas connections with the PSD-lesion at p≤0.05 FWE corrected (t ≥4.80) using ROI to voxel analysis. The crosshair indicates the center of mass of the lesion with the xyz coordinates = 16; 08; 14mm). The right hemisphere is on the right side of the figure.

5

DISCUSSION

5.1

Patient characterization

We characterized the profile of PSD patients in our population. PSD prevalence reached 45% in 59 non-demented patients under 65 years with a first stroke resulting in low residual disability. This rate lying in the upper range of the 25-79% (Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015) prevalence rates reported in the literature, is higher than the prevalence peak of 33% (Dennis et al., 2000) and the 24% rate of the 251 French stroke survivors enrolled in the DEPRESS study (Guiraud et al., 2016). A lower rate could be expected, considering the low disability rate of our population (Robinson and Jorge, 2016) .Our relative high rates could be explained by the scale that was used for the diagnosis of PSD (Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015). Or it could be explain by the young age of enrolled patients (Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015). In this study, even though the rate of depressed patients is higher than in others studies, the intensity of depression is mild, as indicated by the median BDI- FS score of 3 in the whole population and of 7/21 in the depressed group, which is in line with others studies (Paolucci et al., 2006).

Using bivariate comparisons, PSD was associated with low IADL score, indicating a poor autonomy for daily living activity . There was no autonomy alteration in the no-PSD group (8/8), and a mild alteration in the PSD group (6/8), in line with the low residual disability. PSD was also associated with high work and social dysfunction, as reflected the high WSAS score. A median score above 20 in PSD group suggests moderately severe or worst psychopathology (Mundt et al., 2002). The highest difference is for the relational subscore. Depression was also associated with social adaptation impairment and with the need for formal house helpers, highlighting the importance of social support and environment in PSD (Parikh et al., 1987; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009; van de Port et al., 2007).

We think that the association between formal house helpers, poor autonomy and PSD may reflect the difficulty to deal with handicap and loss of independence and correspond to the psychosocial vulnerability related to the reactionary model of PSD.

In this study, PSD was not associated with age and sex, a finding that is not in line with systematic review of PSD risk factors (Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Robinson and Jorge, 2016; Santos et al., 2009). This could be explained by the age range of our population that was lower than in other studies since patients were under 65 of age. PSD was not associated with cognitive impairment as reported in some works (Shi et al., 2015), but not other (Esparrago Llorca et al., 2015; Kutlubaev and Hackett, 2014; Santos et al., 2009). We selected non demented patients, with a high MMSE score, which may explain the low rate of cognitive impairment. Furthermore, executive function and the working memory that are usually altered in subacute stroke (Jaillard et al., 2009), may have recovered at the chronic stage in this young population. Similarly, because of the inclusion criteria excluding patients with neurological severity, high physical disability, previous stroke or depression history, PSD was not associated with the usual risks factors PSD listed in table 1.

We found that right-sided lesions were more frequent in PSD than in non-PSD patients, which is in agreement with previous studies (Dam, 2001; Wei et al., 2015), and may be related to the exclusion of aphasic patients who are commonly depressed. However the difference between right and left sided lesions was not significant, nor is the lesion volume and delay from stroke onset to inclusion linked to PSD.