HD28

.M414

no.WORKING

PAPER

ALFRED

P.SLOAN

SCHOOL

OF

MANAGEMENT

Bridging

theBoundary:

External

Process

and

Performance

inOrganizational

Teams

Deborah

G.Ancona,

617/253-0568MIT

Sloan SchoolofManagement

andDavid

F. Caldwell, 408/554-4114Leavev

School ofBusinessWorking

PaperBPS-3305-91-BPS

June, 1991MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE

OF

TECHNOLOGY

50

MEMORIAL

DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE,

MASSACHUSETTS

02139

^^..i'-Bridyiny

theBoundary:

External Process

and

Performance

inOrganizational

Teams

Deborah

G.Ancona,

617/253-0568MIT

Slo:in School ofManagement

andDavid

F. Caldwell,408/554-41 14Leavey

School ofBusinessAbstract

The

natureoftheexternalactivities in which groups engagewas

investigated using asampleof45

new

productdevelopmentteams. Three broad types ofactivitieswere identified.The

levelsofthese activitiesratherthan simply thefrequency ofteammembers'

communicationwithoutsiders

was

related toindependentratingsofteam

performance. In addition,patterns of theseactivitieswere monitored in the teams and fourstrategies toward theenvironmentwere

derived.Overview

Although groups have always been an important tool foraccomplishingorganizational goals, the

form

and use ofgroupsis changingrapidly. In responseto the acceleratingpaceof technologicaland marketchange, organizations arefrequentlydelegatingmore

responsibilitytotemporary' teamsthan they havein thepast. Furthermore, organizationalunits oftenhave tobe

more

closely coupled than in the past, sometimes evenworking in parallel tocomplete assignments spanning traditional organizational units (Clark&

Fujimoto, 1987;Henderson

&

Clark, 1990).Thus

work

groupmembers

must

frequently interactextensivelywithnon-teammembers

tocomplete their assignments.

As

this trendcontinues,organizational groups can notbeviewed

asbounded

units: ratherthey must be viewed asopen

systems interacting with othergroups orindividuals in theorganizational environment. Despitethe importanceofsuchexternallydependent

teams, relatively littlereseiu"ch has explored

how

they interact with othergroups andhow

those interactions can facilitate the accomplishmentoftheirassigned tasks.Over

the past halfcenturysocial psychologistshave devotedsubstantial attention tothe fine-grained analysis ofbehaviorwithin groups.Many

frameworks

exist forthat analysis includingmodels

ofgroup decisionmaking

(Bourgeois&

Eisenhardt, 1988; Isenberg, 1986;Nemeth,

1986), task and maintenance activities (Bales, 1983;Benne

&

Sheats, 1948; Schein,1988) ,

norm

development

(Bettenhausen&

Murnighan, 1985),andevolution (Gersick, 1988,1989) to

name

afew.The

emphasisinprevious researchon what

goeson

within the grouphasbeen so strong thatdefinitions ofgroupprocess havedescribed it solely interms oftheinteractions

among

groupmembers

that transform resourcesinto a product(Goodman,

1986;Hackman

&

Morris, 1975). Gladstein (1984) found, however, that groupprocessentailed both internal groupprocess and boundary

managment.

Both internal andexternalcomponents

are thoughttobenecessary topredict the perfomiance tothese

new

organization teams.The

purpose ofthisresearch istoexamine

the relativelyunknown

pattern ofgroups' external activities withessential others. Specifically,we

describetherange ofactivitiesteammembers

use to interactwith outsiders andform

atypology;we

testhow

external activities relate to teamperformance, andwe

examine

how

naturallyoccurring groups aggregatemember

activityinto strategies fordealing with others.

Literature

Review

Although themajor emphasis in group theoryhasbeen oninternal

team dynamics

there hasbeensome

attention paid toexternal interaction. Thiswork

has typicallyfocused on theamount

of information thattheteam

acquiresfrom

itsenvironment (c.f. Galbraith, 1977;Lawrence

&

Lorsch, 1967;Thompson,

1967). This information processing approach isnormative; positingthat groups must

match

theirinformation processing capability tothe information processingdemands

oftheexternalenvironment(Tushman

&

Nadler, 1990). Supportforthis approachcomes from

studiesshowing

thatteamscarrying outcomplex

tasksin uncertain environmentsneedhigh levels ofexternal interaction to be high performing

(Ancona

&

Caldwell, 1991; Gresov, 1988;Tushman,

1977, 1979). For example, inresearch anddevelopment

teams, frequencyofcommunication

within theteamsshows

norelationtoperformancewhile increasedcommunication

betweenthe teams andother parts ofthe laboratorywas

strongly related toprojectperformance(Allen, 1984). High-performing teamsalso

showed

higher frequencies ofcomunication with organizational colleagues outside ofR

& D

than theirlow-performing counterparts.However,

byfocusing primarily on thefrequency ofcommunication, these studieshave notaddressed the broader questions ofthepurpose and natureofthose communications.

In direct contrasttothe information processingtheorists,researchers examining

particularorganizational

phenomena

haveconcentratedonspecific activitiesenactedby

groups.For example, those studying innovation have focused on boundary spanning andthe transferof technicalinformation across

team

boundaries (Allen, 1984; Aldrich&

Herker, 1977;Quinn

&

Mueller, 1963; Katz

&

Tushman,

1979), those studying interdependence havefocusedon

have focused on political orpersuasive activities withexternal constituents (Dean, 1988; Pfeffer,

1981). Because they were studying specific organizarional

phenomena

theseresearchers did not usethe groupas a focal unit.As

such, theyhavenot tried tomap

thefull range ofexternalactivitiesused

by

groups todeal with abroad setofenvironmental demands.A

recent qualitativestudy offive consultingteamsdidexamine team

strategies towardthe environment (Ancona, 1990). Three strategies

were

identified: informing, parading, andprobing. Infomiing teams remain relativelyisolated from theirenvironment; paradingteams have

high levelsof passive observation oftheenvironment; and probing teams activelyengage

outsiders. f*robing teamsrevise their

knowledge

oftheenvironment throughexternal contact, seek outside feedbackon

theirideas, and promote theirteams'achievements within theirorganization.Probing teams

were

rated thehighestperformersone

yearafterformation. Althoughthisresearch specificallyexamines

team-environmentrelations, itdoes so usinga small sample anda non-profitorganization.

As

such, theauthorwas

unable to statistically testhow

external activitiesclusterandrelatetoperformance.

The

generalizability tootherkinds of organizationsisalso unclear.To

lookat external activitiesin isolation, however,istoforget thatacomplete theory of organization teamsmust

look at both internal andexternal activities. Previous research hasbeenequivocal about theextentto

which

a particular externalmode

of operationinterferswith—

orfacilitates

—

the developmentofeffective internal operations. Certainevidencesuggests a negative relationship.The

internal cohesion that exists underconditions of groupthink (Janis, 1982, 1985)promotes external stereotyping and avoidance ofexternalinformation thatinterfereswithcurrent

group consensus.

The

intergroupliterature also suggests anegativerealationship between internalandexternal activities.

Groups

oftenbecome

underbounded-havingmany

external ties but aninability tocoalesce and motivate

members

to pull theirexternalknowledge

together— oroverbounded-where

there is greatinternal loyaltyand acomplex

setofinternaldynamics

butaninability toreach outto the external world (Alderfer, 1976; Sherif, 1966). Finally, the conflict

outsiders withdifferent goals,cognitivestyles, and attitudes (Schmidt

&

Kochan,

1972;Shaw,

1971).

Yetnotall studies indicatesuch a negativerelationship. In a study ofeight taskforces

Gersick (1988) foundthatgroups undergo amid-point change

where

they fundamentally shift theirbasic operatingprocedures.

The

study suggeststhatteamsmay

deal with internal and externaldemands

sequentially,first actingon

initial informationfrom

theenvironmentinisolation, thenemergingtoget furtherfeedbackand updatedinformationfi-om outsiders.

A

timingeffectwas

alsofound in a study offive consultingteams

where

Ancona

(1990)foundthat teams thatwere initiallyexternally active but internally dissatisfied

came

tobe cohesiveas external interaction translated into higherperformance.This Study

This study attempts tofill

some

ofthegaps leftfrom previous research. Itis anexploratory study thatdescribes thenature ofexternalactivities, theirlink toperformance, and the

ways

inwhich

realorganizational teamsdeal with bothexternal andinternaldemands.The

Natureof External Activities. Beforeacompletetheoryoforganization groups can bedevelopedwe

needtoknow

more

aboutthenature oftheexternal activitiesthese groupsundertake. Priorto hypothesis testing, oreven hypothesisgenerating,

comes

the stage ofdescription andclassification(Gladstein

&

Quinn, 1985).We

need toknow

what

theseteamsdo

in orderto ascertaintherelevant variables for such amodel.

The

firstgoal ofthis research istodocument

and classify therangeofexternal activities thatone typeof highly interdependentorganizational group portrays.We

want

toknow

notonlyhow much

communication

takesplace betweenagroup and itsorganizational context, but also the nature ofthatcommunication.We

do

notonly want toknow

how

agroup transfers technical information, butalsoother typesofcommunication

thatmay

beused todealwitha broadrange ofExternal Activitiesand Performance.

While

descriptionandclassificationcan beseen asends in themselves, our secondgoal is to

examine

therelationshipbetween externalactivities andperformance.

Teams

areformed

inorganizations tomeet

theneedsofindividuals andto carryoutsome

assignedtask. Therefore, itseems

importanttounderstand whetherexternalactivities facilitate thoseoutcomes. Ifthey do,we

can begin to speculateon

theunderlying causal factors linking external activitiesand performance.Then

models ofteam performance can be generatedthatinclude both theirinternal andexternal components. In terms ofapplication,

we

may

then be betterable to suggesthow

organization teams can improve theirperformance.Unlikethose researchers in theinformation processing school,

we

examine

the relationship betweendifferent t\'pes ofexternalactivity andperformance. Yetinformation processing research has alreadyshown

some

link between theamount

ofexternal activity and performance. Thus,we

alsoexamine

the linkbetween frequencyofcommunication

and performance toascertain whetherourability topredictperformanceisimproved

throughtheadditionofthisdescriptive, content-based,approach.

Strategies.

The

thirdgoal ofthisresearch istoexamine

how

organization teamsorganize themselves tocarryout externalactivity. In otherwords,

which

combinations orpackages ofactivitesoccurnaturally? For example,

do

some

teamsseem

to specialize inone setofactivities, whileothers are generalists?

Do

some

teamsnotengageinexternal activitiesatall?While

in the firstpartofthis researchwe

examine

therange ofexternal activitiesteammembers

mightundertake, notallgroups havethecapacity or willingnessto exhibit the full rangeofactivity. In thispartofthe researchwe

look forpatterns to see ifteamstend tofollowparticularsubsets ofactivity. Then,

we

examine

how

these patterns are relatedtootheraspects ofteam

functioningsuchas internal task

work

and cohesiveness.Such

an approach hasanalogues atthe individual andorganization levels.At

the individual level,literiilly hundreds oftraitshave been identified.A

person can be introverted or extrovened, have an internalorexternal locusofcontrol, orbedominant

or submissive. Butmuch

people. Thus, aparanoid personalityis

made

upofdifferent sets oftraitsthan acompulsivepersonality, and eachrepresents a very different approach toward the external world.

At

the organization level, strategyresearchers havelongbeen interested inclassification schemes.Several typologiesexist, including thatof Milesand

Snow

(1978)—defenders, analyzers,prospectors—and Porter(1980)—cost leadership, differentiation,focus.

We

followthesame

logic atthegroup levelaswe

seektodetermine theexternal strategies thatgroupswithin organizations use.A

typology ofstrategies will allow ustocategorize groupsin ordertodifferentiate theirforms and the implicationsofthose forms. Just as

we

have learned alotfrom

categorizing individuals asparanoid orcompulsive, and organizations asanalyzersor defenders, so toomay

we

be ableto understandmore

aboutgroups through thisapproach.

We

usethe term strategyto label the patternsofexternal activity thatarefound. Thisisnottosuggestthat such patterns are necessarilyintentional. Ratherthey representthesubset of

activitiesa

team

hasdemonstrated for agiven periodoftime. In contrasttotheAncona

(1990) study, these strategiesare derived statistically and arebasedon

a largersample.Summary'.

While

the suidyof small groups hasbeendominated by an internal focus the natureofteamsinorganizationstodaycallsforamore

external approach. In trying tobuild theorythat

combines

the external and internal approachesitis firstnecessary todocument

and classify external activitiessothattherelevant variablescanbediscerned. Afterwe

identify a setofexternalactivities

we

examine

their impacton team

effectiveness toanswertwo

questions. First,do

external initiativesmake

a differencetoteam

outcomes? Second, doesknowing

thetype of external activityimproveprediction overthetraditional information processing techniquethatexamines

frequencyofexternal activity? Finally,we

exploretheways

inwhich

on-goingorganizational teams approachtheirenvironment, and

what

effectthathason

otheraspects ofteamfunctioning. In short,

we

explorehow

teams,which do

not have the necessary information andresources within theirboundariestocomplete their tasks, approachtheirenvironment andjuggle

these external

demands

with theirinternalones.METHODS

Description of

Groups

This studyinvolvedproduct

development

teamsin fivecorporationsin thecomputer,analyticinstrumentation, and photographic industries. Alloftheteams

were

responsiblefordeveloping a protot>'pe

new

product (not basic research)and transferingit to theirfirm'smanufacturing and marketinggroups. Allthe projects used

new

orevolvingtechnologies. For example, oneproduct automatedthe samplingprocess inliquidchromatography; anothercombined

photographic and computer imagingprocesses.Alloftheteamswere

temporary; theywere formed

todevelopa specific prototypeand disbanded oncethe taskwas

complete.Each was

formally headed

by

a projectteam

leader.Team

members

nomially have specificfunctional or technical skills; this assignmentwas

typically the individual'sprimaryresponsibility atwork.Each

organizationprovidedaccessto asetofteamsthathad thefollowingcharacteristics: (1)all theteams hadtobe developing anew

product (definedas a majorextension toan existing product lineor the stan ofanew

productline); (2) toensuresome

broadconsistency inthecomplexity ofthe products, all productshad adevelopmentcycleofone andone-halfto three years; (3)forcomparabilityinperformanceevaluations, all theteamshad tobe located within a single division; and (4) teams ranged inperfomiance; however,

company

executives did notrevealhow

teamswere initiallyclassified untilall otherdatahad been collected.Team

membership was

determinedfrom

company

recordsandverifiedwithteam leaders; averagesizewas

approximately10 (s.d. 6.2).

Data and

Sample

This study usedseveral sourcesofdata. Interviewsand logs

were

used to generatealist ofdifferent, and larger, set ofteamstodetermine theextent towhich they believed it

was

theirresponsibility to

cany

outeach type ofactivity,the frequency ofexternal activity, the stateofinternalprocesses, and assessmentsof

team

performance. Interviews withthe leaders oftheteams that filled outthequestionnaires were

done

toget asecond assessmentofteam

performance and to getbackground

information on theteams.To

identify the setofactionsgroupmembers

mighttake in dealing with others,interviewswere conductedwith 38 experiencednew-product-team

managers

(Ancona

&

Caldwell, 1987).During these semi-structured interviews,

managers

were

asked todecsribethe interactions thatthey,or

members

oftheirteam, had with otherindividuals outsidethenew

product team.We

askedthese

team

leaders tobe asinclusive aspossibleintheirdescriptions andtoincludeall formsof

communication

including meetings, telephonecalls, andcomputer

messages.These

interviewswere

taped andtranscribed. In addition tothe interviews,members

oftwo

new

product teamswere

asked tokeeplogs ofall theirexternal activitiesoveratwo-week

period.The

interview transcriptsand logswere

reviewed by fourindividuals (thetwo

authorsand two

graduate students)toidentify anexhaustivelistofactions team

members

and leaderstookin dealingwithindividuals outsidetheteam.These

actionsbecame

the basis forquestionnaire itemsmeasuringtype ofexternal activity.

Questionnaireswere distributed toassess external activities, internal processes, and

performance.

The

questionnaires were distributed toteamsthatdid nottake partin theprevious interviewandlog datacollection.A

total of450

questionnaires were distributedto teammembers

and leadersof47 teams. Since

many

oftheitems includedin thequestionnairerelated toperceptions oftheteam, thequestionnaires distributedtoeach

team

included alist ofteam

members

toensurethatindividualshad acommon

referent.Completed

questionnaireswere

returnedby 409

individuals,yielding aresponserateofapproximately 89percent.Response

rateswere

approximatelyequal across the fivecompanies; totalresponses per

company

variedfrom 39 to129. Because

much

ofthe analysiswas

conducted atthegroup level,teamswere

includedin thefinal sample only ifat least three-fourths oftheir

members

responded. This reducedthenumber

ofteamsinthefinal sample to45.

The

average ageofthe individualsinthe samplewas

38.6 years; 88 percentwere

male; and 75 percentpossessed atleasta four-year college degree. Approximately 77 percentoftherespondents

were

employed

intheengineering orresearchand development functionsoftheircompanies; theremaining 23 percentwereprimarily

from

themanufacturingormarketingfunctions.

Measures

Types

ofBoundary

Activity.The

analysisoftheinterviewandlog data yieldedatotal of24items including actions such as persuadingothers to supporttheteam, attempting toacquire resourcesfor theteam, and bringing technicalinformation intothe group.

The

24

boundaryactivitieswere

convertedtoquestionnaire itemsby

asking respondentsto indicateon

five-pointLiken

scales the extent towhich

they felteach oftheitemswas

partoftheirresponsibilityindealing with people outside the team.

The

complete setoftheseitems isshown

inTable 1.

Amount

ofBoundar>' Activity.Team

members

were askedhow

often theycommunicated

with non-team individuals in the marketing, manufacturing, engineering and product

management

functions during theprevious

two

week

period.They

respondedon

6-point scales anchored by 1=

Not

atalland 6=

Several times per day. Sincethese functional groupshaddifferentnames

in thecompanies, thequestionnaires were modifiedtoconform

tocompany-specificterminology.Becausethesefourgroupsrepresented every

one

withwhom

team

members

would

normallycommunicate

in theirwork, theseresponseswere

averaged.Team

scoreswere computed

byaveraging the individual scores

(X

=

2.54, s.d.=

.78).There hasbeen adebate in theliterature as towhetherorganization

members

canaccurately assesscommunication

patterns. Bernard and colleagues (1980, 1985) claimthatasking peoplehow

much

they talk to othersproduces inaccurate results. Individuals forgetsome

communications and over countothers. Otherresearchershave counteredthiscriticismby

showing

thatorganizationmembers

may

notreproduce exactlythecommunications

thathavejust occurred, buttheirbiasisin thedirection of long-term patterns ofcommunication

(Freeman,Romney,

&

Freeman,

1987).So

respondents arenotactually answeringthe question"Who

did Ispeakto in thelast

two weeks"

but "In a typicaltwo-week

period, withwhom

am

Ihkely tohavespoken." Since our focus

was

thismore

general pattern ofcommunication, the broadmeasure ofcommunication

frequencywe

usedis appropriate.Internal processes.

As

Goodman,

Ravlin, andSchminke

(1987) have noted, task-orientedgroupprocesses

may

bemore

directly related toperformancethanmore

traditional affect-basedmeasures of group process.

Members'

perceptionsofthe teams' work-relatedgroup process wereassessedwiththree items. Individuals usedfivepoint Likert scales to indicate the team'sability to

develop workable plans, define goals, and prioritize work; high scores defined betterperceived processes (see

Hackman,

1983). Since a principalcomponent

analysis yielded a singleunderlyingfactor,these threeitems

were

averagedtoform

a single scale(alpha=

.86).A

scorewas

thencomputed

foreachofthe45

teams byaveraging theindividual scoresofthemembers

oftheteam

(X =

3.69, s.d.=

.43).Many

ofthearguments suggesting anegative linkbetween externalactivitiesandinternalprocess usecohesiveness asan indicatorofprocess. This

more

traditional affect-based measurewas

assessed using Seashore's (1954) four items.These

fouritemswere

averaged tofomi

a single scale (alpha=

.91).A

scorewas

thencomputed

foreach ofthe forty-five teams by averaging the individual scoresofthemembers

oftheteam (X =

3.7,s.d.=

.81).Team

Performance. Following the stakeholderview oforganiztions, team perfomiancecannot be seenas a simple, uni-dimensional,construct. First,as

Goodman,

Ravlin, andSchminke

(1987) argue, group measuresofperformance

must

be both fine-grained andrelatedto thetask.For example, ifagroup isresponsible forcompleting an innovative

new

product, thenperformance measures should include the group's innovativeness notjust general

member

satisfaction. Second, Gladstein (1984) found thatevaluations ofgroup performancediffer

depending

upon

whether groupmembers

ormanagers

aredoingthe rating. Thissupports Tsui's (1984) contention thatdifferentconstituencies often havedifferent definitionsofperformance andsuggests thatratings

from

thesevariousconstituenciesbe included in astudy ofgroup performance. Finally, groupresearchershave found a lag effectbetween groupprocessand performance (Ancona. 1990; Bettenhausen&

Mumighan,

1985; Gladstein, 1984). This suggeststhatprocesses exhibited at time 1,ma>' impact performanceattime 1 or time 2.

Going

onestepfurther,certain processes

may

have a positive effectin theshort-term but turnout tobenegativeovertime. Thus, thisresearch

examines

theimpactofexternal groupprocesseson

severalmeasuresofperformance, asrated b)' both group

members

and topmanagement,

inthe short-termand atprojectcompletion.

Performancedata

were

collected attwo

pointsintime.The

firstcoincided withother data collectionfrom team

members

(time 1) and the secondwas

approximatelytwo

yearslater,when

teams had completed theirprojectsor werein thefinalstages (time2).

Top

divisionmanagers

were

asked toassess the teams in theircompany. Using

fivepoint Likert scales,theyrated eachteam's efficiency, qualityoftechnical innovations, adherenceto schedules, adherence to budgets,

and abilitytoresolveconflicts. Although thesample size

was

small, the performanceitemsateachtime

were

subjected to a principalcomponents

analysis toidentifyunderlying patterns. Usingthe data collectedat time 1,two

factors emerged.One

factorwas

definedby theadherence to budgetsand adherence to schedules questions.

We

averaged thosetwo

items toform

a single variablewe

call budgets and schedules.

The

remaining threeitemsloaded onthe secondfactor;we

averagedthem

tocreate a variablewe

call efficiencyof innovation .A

different factor structureemerged

when

the performancemeasurescollectedattime2were

analyzed.One

factor,which

we

label innovationwas

defined solelyby

the single qualityof technicalinnovationsproduceditem.The

second,

which

we

labelteam

operationswas

defined bytheremainingfouritems,which

were averaged toform

a scale score.To

assure comparabilityoftheperformance ratingsacrosscompanies, individual scoresforeach

team

were adjusted by subtracting themean

ofthe scoresassigned to teamswithin that

company.

Thus

the performancescoreswere

adjustedforcompany

and the overallmeans

set to zero.One

additional performance measurewas

collected attime 1.Team

members

were askedinthequestionnaireto rate theperformance oftheirteams

on

six dimensionsincludingefficiency, quality,technical innovation, adherence to schedules, adherencetobudgets, andwork

excellence.These

itemswere completed by all individuals,allowing a principalcomponents

analysisofthe itemswas

conducted.The

analysis yielded a singlefactor.A

score,which

we

call team ratingwas

assigned to each

team

byaveraging the individualmembers'

scores(alpha=

.83)(X =

3.63, s.d.=

.38).

Analysis

The

analysismoves

through three stages: factor analysis,regression analysis, and Q-factor analysis. First, the409

individual responses to the 24 boundaryactions are factoranalyzed torepresent the underlying structure. Factoranalysis allows ustodescribe external activitiesina

more

succinctand non-overlappingmanner

than ispermittedwiththeunwieldy24

items. Factor scores are then calculated foreach individual and averagedtoform

groupscores.'' Factoranalysis yields severalindependentactivity sets

made

upof highlyrelatedexternal actions. Next, regressionanalysisis usedtodetermine the relationshipsbetween both frequencyand

typeofactivityand performance. Thisregression allows ustoevaluate theusefulness ofactivity types,

overand above theinformation processing model,in predictingperformance.

Finally, Q-factoranalysis is used toidentify clustersofteams usingthe

same

pattern of external activities. Q-factoranalysis issimilartoclusteranalysisinthatitcanproduceataxonomy

ofexternal strategiesindicating

how

external activitieswork

incombinations.While

regression"•Note:

modes

of aggregation other than averaging were tested to examine different assumptionsabout

how

groups represent all individualmember

contributions. For example,we

summed

individual scores under the assumption that a team's external activity is simply thesum

of individual contributions.Changes

in aggregation procedures did not significantly affect results.analysis statistically isolates the independenteffectsofeach activity set, such a technique does not

tellus

which

combinationsorgestalts naturallyoccurand towhat

effect (Hambrick, 1983). Q-factor analysis groupstogether thoseteams thatsharecommon

approaches to theenvironment, andthesegroupings can tlien be

compared

along otherdimensions such as internal process.RESULTS

Types

ofBoundary

ActivityIndividuals' ratings ofthe extent to

which

theyassumed

responsibility foreach ofthe24

boundary

actionswere

analyzedwith a principalcomponent

analysisandavarimaxrotation. Fourfactorswith eigenvalues greaterthan 1.0explained

60

percentoftotalvariance. InspectionoftheScree plot supported thefourfactor solution. Table 1

summarizes

this analysisandshows

the itemloadings greaterthan .35.

INSERT

TABLE

1ABOUT HERE

Factors aredescribed byitems with loadings greaterthan .50.

The

firstfactorcontains 12 itemsthat reflect both buffering andrepresentational activities.Examples

of buffering includedsuch things as protecting the

team

andabsorbing outsidepressure. Representational activitiesincludedpersuadingothers to supportthe

team

and lobbyingfor resources. Since theseactivitiesrepresent bothprotective andpersuasivegoals,

we

labelthem

asambassador

activities.The

secondfactorwas

definedbyfiveitemsthatrepresent interactionsaimed

atcoordinating technical ordesign issues.

Examples

ofactivities in this set include discussing designproblems with others, obtaining feedbackon theproductdesign, coordinatingand negotiating with outsiders.

We

label these taskcoordinatoractivities.The

third factorwas

made

up

of four items describing behaviors thatinvolve general scanning for ideasand information about thecompetition, themarket, or thetechnology.We

labelthis factorscout activity. Theseitemsdiffer

from

theprevious itemsinthatthey relate to generalscanningas

opposed

tohandling specific coordinationissues.The

fourth setofactivitiesrepresent actionsthatavoidreleasing information.We

labelthethree itemsthatdefine thisfactor guardactivities. Since these activitiesdiffer

from

theotherthreein thatthey

do

notrepresent initiativestoward theenvironment, but rather internalactivitiestokeepthings

from

theenvironment,we

do

not include guard activities in subsequent analyses.Factorscores were

computed

foreach individual and then averagedtoform

scores foreach group. Althoughorthogonal atthe individual level,

when

theindividual scoreswere

averagedtofomi group scores

some

intercorrelation emerged. Table2shows

means, standarddeviations,andcorrelations

among

all variables.Ambassador

activities are positively correlated with task coordinatoractivities and negativelywith scoutactivities. Frequency ofcommunication

was

not significantly related toany ofthe activity setsat thegroup level. There weresome

relationshipsbetween theseexternally-orientedactivitiesand internalgroup process. Frequency of

communication

was

significantlyrelated onlytocohesiveness, and the relationshipis negative.Groups

with high levelsofambassador activitiesreported higherratings ofinternalprocess andmarginally higherratings of cohesiveness than groupswith

low

levelsofthisactivity.An

opposite patternwas

observed forscoutactivities.The

levelofthatexternal activityshowed

small negative relationships withinternalprocess and cohesiveness.Boundary

Activitiesand ProductTeam

PerformanceThe

correlational analysis indicatessome

significant relationshipsamong

performancemeasures, and between boundaryactivities and performance.

Not

surprisinglysome

performance measures are alsointerrelated. Recallthatthemanagement

ratingsofperformance are adjusted bya subtractionofthecompany mean

toinsure comparability acrosscompanies.The

two

time 1management

ratingsofperformancewere positively relatedand werebothrelated to thetime 2measure

ofinnovation.The

teams'own

ratings ofperformancewere

unrelatedtomanagement's

ratingsofperformance.

Of

central interest are the correlationsbetween theboundaryactivitiesandperformance.Ambassador boundary

activitieswere

positively associated withmanagements'

ratings of teams'abilityto

meet

budgets and schedules (time 1) and ofteam members'

ratingsoftheirown

performance (time 1). Thereisalso

some

relationshipwithmanagement

ratingsof innovation (time2). Higherlevelsoftask coordinatoractivitieswere

associated with higherratings (twosignificantat p

<

.05;two

marginalat p<

.10)on

all fourmanagement

provided performance measures (time 1 and time 2).An

opposite patternwas

truefor scout activities,which were

negatively associated with ratings

on

the time 1 measures ofbudgets and schedulesand innovationefficiency and thetime2

measure

ofinnovation as well asteam

ratingsofperformance. Frequency ofcommunication

was

marginally associated with time 1 meeting budgets and schedules andefficiencyofinnovation, and highly negativelyrelated to

team

ratingsofperformance.INSERT

TABLE

2ABOUT HERE

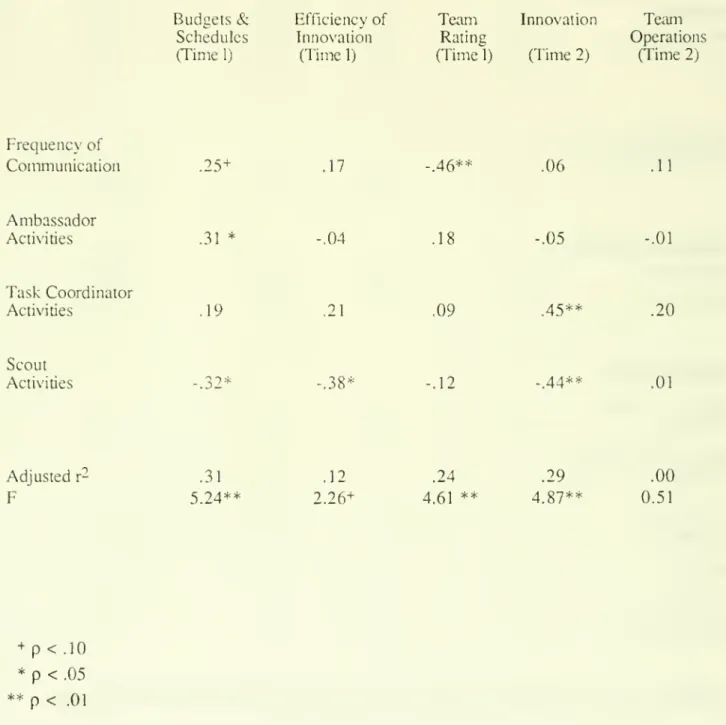

Table 3 reports regressionequationsforeachofthe fiveperformance measures.

The

results are straightforward.

Adherence

to budgets andschedules (time 1)was

positively related tofi-equencyof

communications

and ambassadoractivities and negativelyrelatedto scoutactivities.Efficiencyofinnovation (time 1)

was

negatively related toscoutactivities.Task

coordinatoractivity is

no

longerrelated totime 1 managment-ratedperformance, perhapsdue to multi-collinearity.The

teams' ratingsoftheirown

performance(time 1)was

negativelyrelated tofrequencyof

communication

with others.The

finalratings,obtained aftertheprojects werecompleted

were

somewhat

different. Innovation (time2)was

positively related totask coordinatoractivitiesand negativelyrelated toscout activities.

Team

operations (time 2)which

includedadherenceto both budgetsand schedules

was

not predicted bytheexternalactivities.INSERT

TABLE

3ABOUT HERE

Group

Strategies forBoundary

Management

The

relationshipsamong

thegroup-levelmeasures ofboundaryactivities suggest thatteamsmay

use consistent strategies todeal withoutsiders. Inotherwords, teamsmay

make

clearchoices(whetherintentionallyor not) toundertake certain boundaryactivities and notothers.

To

identify these strategies,Q-factoranalysiswas

used. Incontrast tomore

conventional R-factoranalysis, Q-factoranalysis is basedon

therespondents,rather than the variables, and seekstocombine

orcondense respondents intodistinctly differentgroups within thepopulation. Q-factor analysis differs

from

clusteranalysisin thatthegroupings are basedon

intercorrelations betweenmeans

andstandard deviations oftherespondents ratherthan

on

theabsolutedistancesbetweenthe respondei.ts' scores. Thus, Q-factor analysismay

bemore

sensitive to patternsamong

the variablesthan absolutedifferencesin magnitude.A

Q-factor analysis withavarimaxrotationwas

performedon the45

groups usingthegroupscores

on

theambassador

,task coordinator, and scout variables. Thisanalysis identifiedfourdistinct sets ofgroups thataredepicted in Table4.

The

firstpartofTable 4shows

theresultsofthree

one-way

analysesof variance (with group size asa covariate) using groupscoreson

theambassador

, taskcoordinator, and scoutvariables asdependent variables.The

Q-factoranalysis identified fourstrategies.The

first concentrateson ambassador

activitiesand very littleelse. In otherwords, team

members'

outside activitiesareprimarily asambassadors.

As

suchwe

label this strategyambassadorial.The

second strategycombines

scout activities withsome

taskcoordination. Sincethis setofteamsis scanningtheenvironmentfor technical data ratherthan persuadingtopmanagement

ofitsachievementsit is labeled technical scouting.The

third setofteams is relativelylow on

all dimensions, although thereissome

minimalscoutactivity.

We

label this strategy isolationism. Finally,the fourth setofgroups havemembers

feelingresponsibleforboth ambassador and task coordination activities,butlittlescouting. This strategy avoids general scanning;it focuseson external interaction to both persuade others thatits

work

isimportant, and tocoordinate, negotiate,and obtain feedbackfrom

outside groups.We

label this strategy comprehensive.Table 4provides data illustratingproperties ofteamsfollowingdifferent strategies. There

were

significantdifferences incommunication

patterns across strategies.Those

teamsfollowing theambassadorial strategy and theisolationism strategyhavethelowest frequency ofcommunication

withoutsiders and althoughnot shown,members

ofthese teams spend the lowest percentage oftheirtime withoutsiders(12%

and10%

respectively). In contrast, technical scoutingand comprehensive teams havethehighest frequency ofexternal interactionand spendthehighest percentage oftheir time with outsiders

(18%

and16%

respectively).More

in-depth analysisshows

thatambassador

activity (found in teamsusing ambassadorial and comprehensivestrategies)may

show

low

levelsofexternalcommunication

because individualshavehigh levelsofcommunication

with topdivisionand top corporatemanagement.

Tliisconcentratedconimunication requires a lowerfrequency ofinteraction than the

more

diffusecommunication

patterns found withstrategiesinvolving scoutandtaskcoordinatoractivity.The

latter involvehigh levelsofinteractionacross manufacturing, marketing, andR&D.

The

external strategies haveimplicationsfor internal processesas well. Ambassadorial teamsshow

themost

effective taskprocesses andhighestcohesiveness. Thisform

ofexternal interaction eitherpromotesuseful internal interaction,oreffective internal interactionallowsforthislegitimating externalactivity. Thus, whileingeneral high levelsofexternalactivity are relatedto

poorinternal processes, certain types ofexternal activityfacilitate, orare facilitatedby, effective internal processes.

The

various strategiesshow

differentrelationships toperformance.While

bothambassadorial and comprehensivestrategiesare related toachieving budgets and schedulesin the shortterm(time 1), only thecomprehensive strategy is positively relatedtoperformance over time (innovation,time2).

Both

the technical scouting teamsand theisolationism teams have poorperfoimanceacrossperformanceindicatorsovertime (seeTable 4).

INSERT

TABLE

4ABOUT HERE

DISCUSSION

The

increasingrelianceon

teams todevelop products and processesrequires thatteamsspan traditional organizational boundaries. Funhermore,as levelsofmiddle

management

disappearteams aregiven increasingresponsibility todefine, market, carryout, and transfertlieir

work. These

new

responsibilities requireextensiveexternal interaction with organizationalmembers

outside the groups' boundaries. This study has exploredthe natureof those externalactivities and theirrelationships tootherkey groupvariables. Results

show

new

models

ofgroupprocess,

new

understandings ofthefactors related to group performance, anda typologyof groupstrategies toward theenvironment.

Group

Process RevisedThis studyidentifies fouractivity sets labeledambassador, task coordinator, scout, and guardactivities.

Ambassador

activitiesreflect primarily buffering,e.g. absorbing pressures andprotecting theteam, and representational activities, e.g. persuadingothersto supportthe

team

andlobbying forresources.

Task

coordinatoractivitiesareaimed

atcoordinationaround specific technical issues such asobtainingfeedbackon

theproduct designon negotiating deliverydeadlines with outsiders. Scout activities entailmore

general scanning forideasandinformation than thespecific,focused taskcoordination. Finally, as theexistenceofguardactivities indicates,these external activitiesare

combined

withinternalactivitiestodetermine thepermeabilityofagroup'sboundary.

Extemal

initiatives appe;irtoallow the group to accesskeyresources in theenvironment.Ambassadorial activitiesprovide access to the

power

structure oftheorganization; they areaimed

atmanaging

vertical dependence. These activitiesprotectthe team fromexcessive interferencefrom

the top, and facilitate the group'slegitimacy and survival byidentifying key threats, securing resources, and promoting theimage

oftheteam.Task

coordinatoractivitiesprovide access tothework

flow structure; theyareaimed

atmanaging

horizontal dependence.These

activitiesprobablyfill in

many

ofthe gapsleftby

formal integrating systems.Through

coordination, negotiation, andfeedback, theseactivitiesallowfortightercoupling with other organizationalunits

who

also contributeto thegroup's final output. Scoutactivitiesprovide accessto theinformation structure;they are

aimed

at adding tothe expertise ofthe group.These

activitiesallow the group toupdateitsinformation base,providing

new

ideas and signalingchangesin technologies andmarkets.Thisresearch suggests thatextemal activitiescan be effectively

combined

with internalprocesses.

While

frequency ofcommunication

alone and scoutactivities are negativelyrelated tocohesiveness andintemalprocesses, ambassadoractivitiesarepositively related tointernal

measures. Thus,teams appeartobe able tocoalesceifthey havespecific, focused extemalactivity

aimed

atinfluencingpowerful outsiders. Continuous high levels ofactivityaimed

atobtainingmore

general information about theenvironmentinterfereswiththeteam'sabilityto setgoalsand develop supportamong

members.

Since this ambassadorialactivity appearstoimprove

performance,while scout activity

dampens

performance, it appearsthattheextemal activities thatare associatedwith

good

intemal processesalso are associated with performance.Although

allkinds of organization groups (e.g. task forces, salesteams, innovating teams,and even top

management

teams) faceextemal dependencethese activitieshavenot beenincorporated intoour

models

ofgroupprocess. This research suggests that extemal boundaryactivitiesbeadded totaskand maintenance activitiesinorderto

more

fully represent the fullrange ofwhat

groupmembers

do. Clearly, inorganizational settingsmany

groupsdo

notwork

inthe isolationcharacteristic ofartificial groups thatpreviouslyhave been studied. Real groups needtomanage

their boundariesandadapt totheorganizational environment.An

enlargedmodel would

also helpmanagers tostructure team activities tomeet internal and external objectives.PredictingPerformance

As

theresultsindicate, the pattern ofexternalactivities aremore

important than simply thefrequency ofcommunication. Frequentcommunication

ismarginally related tomanagement

ratingsof performanceat time 1 but notattime 2.The

activity sets aremore

strongly related tomanagement

ratings ofperformance, than frequency. In addition,theactivity sets relatedtothe differentperfonnancemeasures in singularways.Ambassador

activitieswere

related totime 1management

ratingsofthe teams'adherenceto budgetsand schedules.Task

coordinationactivities, however,

were

positively relatedtomanagement

ratingsofinnovation attime 2. Incontrast to thispattern, very generalintelligence gathering

-

definedby ahigh level ofscoutactivity

-

was

associatedlow

managerialratingsofperformanceatboth time 1 andtime2.Analyzing

team

strategiesprovides alittlemore

insight into long-term performance.While

ambassadorialactivitiesseem

to be akeytoperformance, theireffectoverthelong-termseems

tohold only in combination with taskcoordinatoractivities. Pure ambassadorial teams andcomprehensive teams

move

alongon

budget andschedule attime 1.At

time2,however, the ambassadorial teamsarepooratinnovationandteam

operations, whilethecomprehensive teamscontinueto bethe highestperformers. This suggeststhat while

managing

thepower

structure alonemay

work

in theshort-term teams thatmanage

both thepower

structure and thework-flowstructuremaintain perfomance overtime. This findingissimilar tothatreportedby Zurger and

Maidique

(1990). Furthermore, notall task related activityiseffective.Too much

scoutactivityisrelatedto

low

performanceratings. Itmay

be that suchteams constandyreacttogeneralenvironmentaldata and

become

unable tocommit

toproducinga specific endproductata specific pointintime. Or, itmay

be thathighlevelsofscout activitysomehow

reduces theeffortsteam

members

put into themore

performance-relevantexternal activitiesorintobuildingeffective internal processes.A

verydifferent pattern emergeswhen

theteam

ratesitsown

performance.Teams

feel that they performwellwhen

they concentrate theirefforts internally; theyrevealperceptionsofperformancethatarenegativelyrelated tofrequency of

communication

and positively related tocleargoals andpriorities and high cohesiveness. Thus,predictorsof

management

ratedandteam-rated performancearevery different.

Team

members

may

well have followed an attributionprocess similarto thatdescribedby

Staw

(1975), Calder(1977) andGladstein (1984). For example, Calder arguedthat individualshave implicittheories ofwhat

makes

a leader.When

they seeall oreven afew

ofthese behaviors they attribute leadershipstatus to that person. Similarly, Gladstein foundthat groupmembers

label theirgroup as high performingwhen

theyexhibit processcharacteristics (e.g. highlevelsofintra-group coordination and strong internalprocess) thoughtto be linked toperformance. This activation ofimplicit theories then guides the interpretation ofsubsequentbehaviors.

Group

StrategiesThis studyidentifiedfour strategiesthatgroups usetoward theirenvironment. In one set

ofgroups

members

concentrated solelyon

ambassadoractivities, sowe

label theirstrategy ambassadrial.The

second setof groups hadmembers

concentrateon

scoutactivities sowe

labeltheirstrategy general scouting.

The

third setofgroups had relativelylow

scoreson

all activity setsso theirstrategyis labeled isolationism. Finally,the last setofgroupsincluded

members

engaged

inbothambassador

andtaskcoordinatoractivities. This setofteams approached abroad setofexternal constituentswitha broad rangeofactivities and theirstrategyisthuslabeled

comprehensive.

The

group strategiesobservedin this study arevery similarto thosefound byAncona

(1990)despite having been derived

from

averydifferent setof teams, incompanies from

differentindustries, and using a ver>'differentmethodology.

Ancona

found one setofteamsthatremainedrelativelyisolated from key external constituents,and anotherthatengaged inextensivescanningor "parading" withintheenvironment with no specific agenda.

A

third setofgroupshad high levels ofinteraction bothvertically and horizontally with theenvironment, andengaged

inbothself-promotion and idea testing with outsiders.

However,

inAncona's study there wereno

groupsexclusivelyfollowingthe political persuasion strategy.

These

two

studies togetherprovide supportfor the validity ofthese strategies asrepresentingrealpatterns found inorganizational teamstoday. In addition, this

taxonomy

provides abasisforcategorizinggroups anddifferentiating theirformsandthe implicationsof those forms.These

strategiesalsoillustrate thecontributionofa content, ratherthan a frequency-based,approach toexternal interaction. If

we

were to look at external frequency alone,teams following an isolationism andambassadorial strategywould

be groupedtogetheraslow

frequencycommunicators

and teams followingageneral scouting and comprehensive strategywould

be grouped togetheras high frequencycommunicators. Yet such a classificationwould

mask

great within groupvariance.Funhermore,

given theuncertainty and complexityofthehigh-technology,new

productteam

environment, onewould

predictthathighfrequency teamswould

bebetter performers.As

shown, this is not always the case.Finally, while

some

strategiesappeartobemore

related toperformancethanothersthesestrategiesarenotautomatically followed.

The

coalition formation strategywas

betterlinked toallperformanceratings thanother strategiesbutonly 10 outof

45

teams followed this strategy.Othersfollowed onlyparts ofthe strategy,e.g. ambassadorial teams, or strategies notatall linked

toperformance e.g. general scouting teams. Future research isneededto ascertain whether groups

do

not follow optimal strategies becausetheydo

notknow

what these strategiesare, or theyknow

them

butdo

not havetheresourcestoimplementthem, oriforganizational ortask variablespromptlessoptimalexternal actions.

Limitations

This study has

some

inherentweaknessesthat limitthegeneralizabilityofthe findingsandthe validity of the results.

The

studywas done

in high-technologyindustriesusing teams with high levelsofexternaldependence

andcoordinationdemands.While

this allowed ustomap

awide domain

ofexternal activities,the findingsmay

notapply tomore

isolated,self-contained teams. Indeed,we

argue thatthe internal perspective withitsemphasis on internaldynamics

may

well predict performance inT-groups, laboratory groups, andautonomous

work

groups-itjustdoes not

do

wellfor thenew,more

externally-tied organization groups. Obviously, theinversemay

hold too, limiting theexternal perspective toorganizational groups such asnew

product teams, salesteams, or cross-functional task forces.In addition, the study utilized subjective ratingsofperformance,albeit

from

multiple sources.While

more

objective ratings such as percentoverbudget or actual saleshave beensuggested, (Clark

&

Fujimoto, 1987) itwas

ourexperience thatthesenumbers were

often interpreted through subjective lenses,were

influenced bynumerous

otherexternal factors notunder the controlofthe team. (e.g. an

economic

recession) andwere

lessimportant thanmanagerial ratings indetermining promotions, futurejobassignments, and performance

evaluations. Nonetheless, subjective ratings arejust perceptions and

we

may

bemapping

performance onto distortedperceptions. Finally, theuseofself-reportmeasures raises thequestion of

how much

oftheexplained variance iscommon-method

varianceandhow much

is true variance. This isparticularlyproblematicin investigating thelink between team-ratedprocessand performance.Despite these limitations thestudydoes representone ofthe

few

large-scaleempirical studiesofgroups within organizations. Itdemonstrates thatwhilethedominant

internal perspectivehas stressed internal group processes, the externalperspective illuminates thewide rangeofexternalactivities thatmany

organizational groupsexhibit.Ambassador,

task coordinator,and scout activitiesrepresentan added dimension of group process.

These

dimensionsareconfigured in particularpatterns within thegroups studied here.

Some

groups concentrateon

ambassadorial activities (ambassadorial strategy), others

on

scouting(technical scouting strategy),others not

on

anything (isolationist strategy) and othersonbothambassador

andtaskcoordinatoractivities (comprehensive strategy).

While

thestudy illustratesa strongerrelationship betweenexternal activitiesand managerially-rated performance than forinternalprocesses andperformance, notall external strategiesareequally successful and higherfrequency ofexternal activity aloneis not

enough

to sustainperformance.Key

activities areambassador

andtaskcoordinator. Yet the former, alone, onlyworks

in the short-term. Persuasion and political influence withoutbackup

of technical innovation anda solid product, isfound outovertime.Therefore, this study hasgreatly

expanded

ourknowledge

ofthe external perspective. Ithas

expanded

oursampleofgroups toinclude intact teamsin organizationsand usedthose teams to shiftourmodels

of process and performance. There is supportformoving

the group-research lensfrom

a position looking solelywithin thegroup, toone

thatrotatesfrom

an inwardto an outwardperspective. Perhapsonly then can

we

learn toreconcile the alternativemodels

ofteam

members

andmanagers

in terms oftheprecursors ofgroup performance, andleam

to understandthenew

kind ofgroupthatisso prevalent inthecorporatearena.

REFERENCES

Alderfer, C.P. 1976.

Boundan'

relations andorganizational diagnosis. InM.

Meltzerand F.Wickert

(Eds.),Humanizing

organizational behavior, 142-175. Springfield, IL:Charles C.

Thomas.

Aldrich, H.E.,

&

Herker, D. 1977.Boundary

spanningroles and organization structure.Academy

of

Management

Review,

2: 217-230.Allen, T.J. 1984.

Managing

theflow of

technology:Technology

transferand

thedissemination

of

technologicalinformation

within theR&D

organization.Cambridge,

MA:

The

M.I.T. Press.Ancona.

D.G. 1990. Outw^ird bound: Strategies forteam

survival in theorganization.Academy

of

Management

Journal, 33(2): 334-365.Ancona,

D.G.&

Caldwell,D.F. 1987.Management

issues facingnew-product teamsin hightechnology companies. In D. Lewin, D. Lipsky, and D. Sokel (Eds.),

Advances

inIndustrial

and

Labor

Relations, 4: 199-221,Greenwich,

Ct:JAI

Press.Ancona, D.G.

&

Caldwell,D.F. 1991Demography

and design: Predictors ofnew

productteam

performance.Organization

Science, forthcoming.Bales, R.F. 1983.

SYMLOG:

A

practical approach to the study ofgroups. In H. H. Blumberg,A.

P. Hare, V.Kent

&

M.F.

Davies (Eds.),Small groups

and

social interaction, 2:499-523.

Benne, K.,

&

Sheats, P. 1948. Functional roles ofgroupmembers.

Journal of

Social Issues, 2: 42-47.Bernard, H.R., Killworth, P.D., Kronenfeld, D.

&

Sailer, L. 1985.On

the validityofretrospective data:The

problem

ofinformant accuracy.Annual

Review

inAnthropology.

Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.Bernard, H.R., Killworth, P.D.

&

Sailer, L. 1980. Informant accuracy in social networkdata, IV:A

comparison ofclique-level structurein behavioral and cognitivedata. SocialNetworks,

2: 191-218.Bettenhausen, K.

&

Mumighan,

J.K. 1985.The

emergence

ofnorms

in competitivedecision-making

groups. AdministrativeScience

Quarterly, 30: 350-372.Bourgeois, L.J.

&

Eisenhardt.,K.M.

1988. Strategic decision processesin high velocityenvironments:

Four

cases in themicrocomputer

industry.Management

Science, (34)1:816-835.

Calder, R.J. 1977.

An

attribution theory ofleadership. InB.M. Staw

and G. R. Salancik (Eds.),New

directions in organizational behavior, 179-204. Chicago: St. Clair. Clark, K.B.&

Fujimoto, T. 1987.Overlapping

problem

solving inproduct

development.

Working

Paper 87-048, HarvardUniversity Graduate School of BusinessAdministration, Cambridge,

MA.

Dean,

J.W., Jr. 1987.Deciding

to innovate:Decision

processes in theadoption of

advanced

technology.Cambridge,

Masss.: Ballinger PublishingCompany.

Freeman,

L.,Romney,

A.K.

&

Freeman,

S.E. 1987. Cognitive structureand informantaccuracy.

American

Anthropologist, 89: 310-325.Galbraith, J.R. 1977. Organization Design. Reading,

MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Gersick, C.J.C. 1988.

Time

and transition inwork

teams:Toward

anew

model

ofgroup development.Academy

of

Management

Journal, 31(1): 9-41.Gersick, C.J.C. 1989.

Marking

time: Predictable transitions in task groups..Academy

of

Management

Journal, 32(2), 274-309.Gladstein, D. 1984.

Groups

incontext:A

model

oftask group effectiveness. AdministrativeScience

Quarterly, 29: 499-517.Gladstein,D.

&

Quinn,J.B. 1985.Making

decisions and producing action:The

two

facesof strategy. In H. Pennings (Ed.), Organizational strategyand

change:

198-216.San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goodman,

p. 1986.The

impact oftask and technologyon

group performance. In P.Goodman

(Ed.),

Designing

effectivework

groups: 198-216.San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Goodman,

P.S., Ravlin, E.,&

Schminke,

M.

1987. Understanding groups in organizations. InL.L.

Cummings

&

B.M.

Staw

(Eds.),Research In

Organizational Behavior, 9: 1-71.Gresov, C. 1989 Exploring fit and misfit with multiple contingencies. Administrative

Science

Quarterly. 34; 431-453.Hackman,

J. R.,&

Morris, C. G. 1975.Group

tasks, group interaction process and group performance effectiveness.A

review and proposed integration. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.),Advances

inexperimental

social psychology, 8: 45-99.New

York:Academic

Press.

Henderson, R.M., and Clark,K.B. 1990. Architectural innovation:

The

reconfiguration ofexistingproduct technologies and the failureofestablishedfirms. Administrative

Science

Quarterly, 35: 9-30.Hambrick,

D.C. 1983.Some

testsoftheeffectiveness andfunctional attributes ofMilesandSnow's

strategic types.Academy

of

Management

Journal, 26(1): 5-26.Isenberg, D.J. 1986.

Group

polarization:A

critical review and meta-analysis.Journal of

Personalityand

SocialPsychology,

50: 1141-1151.Janis, I.L. 1982.

Groupthink.

Boston,MA:

Houghton

Mifflin.Janis, I.L. 1985. Sources oferror in strategic decision making. In Johannes

M.

Pennings and Associates (Eds.), 157-197. Organizational strategyand

change,

Jossey-Bass,San

Francisco,

CA.

Katz, R.

&

Tushman,

M.

1979.Communication

patterns, projectperformance,and taskcharacteristics:

An

empirical evaluation andintegration inanR&D

setting.Organizational

Behavior

and

Human

Performance,

23: 139-162.Lawrence,

P.R.,&

Lorsch, J.W. 1967. Organizationand

environment:

Managing

differentiationand

integration.Homewood,

IL: Richard Irwin.Malone,

T.W.

1987.Modeling

coordination in organizations and markets.Management

Science, 23: 1317-1332.

Miles, R.E.

&

Snow,

C.C. 1978.Organizational

strategy, structureand

processes.New

York: McGraw-Hill.Nemeth,

C.J. 1986. Differential contributions ofmajority and minority influence. PsychologicalReview,

93: 23-32.Nadler,

D.A.

&

Tushman,

M.L.

1988. Strategic organization design: Concepts, tools,and

processes. Glenview, Illinois: Scott,Foresman

andCompany.

Pfeffer, J. 1981.

Power

in organizations. Marshfield, Mass.: Pitman.Porter,

M.E.

1980. Competitive strategy.New

York: Free Press.Quinn, J.B. and Mueller, J.A. 1963. Transferring research results to operations.

Harvard

Business Review,

4\ (January-February): 44-87.Schein, E.H. 1988.

Process

consultation: its role in organizationdevelopment,

(Vol.1). Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Schmidt, S.M., and

Kochan,

T. 1972.The

concept ofconflict:Toward

conceptualclarity.Administrative

Science

Quarterly. 17: 359-370.Seashore, S. 1954.

Group

cohesiveness in the industrialwork

group. Institute for Social Research, University ofMichigan.Shaw,

M.

1971.Group

dynamics:

The

psychology of small

group

behavior.New

York: McGraw-Hill.Sherif,

M.

1966. Incommon

predicament:

socialpsychology of

intergroup conflictand

cooperation. Boston,MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Staw,

B.M.

1975. Attribution ofthe'causes'ofperformance:A

general alternative interpretationof cross-sectional research

on

organizations. OrganizationalBehavior

and

Human

Performance,

13: 414-432.Thompson,

J.D. 1967.Organizations

in action.: Social science basesof

administration therapyNew

York:McGraw-Hill

Book Company.

Tsui, A.S. 1984.

A

role set analysis of managerial reputation. OrganizationalBehavior

and

Human

Performance,

34: 64-96.Tushman, M.L.

1977. Specialboundary

roles in the innovation process. AdministrativeScience

Quarterly, 22: 587-605.Tushman, M.L.

1979.Work

characteristics and subunitcommunication

structure:A

contingencyanalysis. Administrative

Science

Quarterly, 24: 82-98.Zurger, B.J. and Maidique,

M.A.

1990.A

model

ofnew

productdevelopment:An

empirical test.Management

Science, 36: 876-888.TABLE

1VARIMAX

FACTORY

LOADINGS FOR

BOUNDARY

MANAGEMENT

DIMENSIONS

n=409

Absorb

outside pressuresfor theteam

so itcan

work

freeofinterference.Protect the

team from

outsideinterference. Prevent outsidersfrom

"overloading" theteam with too

much

information ortoomany

requests.Persuade otherindividualsthat theteam's

activitiesare important.

Scan the environmentinsideyourorganization for threats to theproduct team.

"Talk up"the

team

tooutsiders.Persuade othersto support the team'sdecisions

Acquire resources (e.g.

money,

new

members,

equipment) fortheteam.

Reportthe progressofthe team to a higher organizational level.

Findoutwhetherothersin the

company

support oroppose yourteam's activities.Findout information on your company's

strategy orpohtical situation that

may

affectthe project.Keep

other groups in thecompany

infonnedofyourteam's activities.

Resolvedesign problems with external groups.

Coordinate activities withexternal groups. Procure things

which

theteam

needsfrom

othergroupsorindividuals inthe

company.

.785 .740 .719 .654 .636 .602 .592 .587 .553 .551 .549 .519 .417 .416 .417 .403 .449 .430 .421 .776 .660 .657

Negotiate with others fordeliver)'deadlines.

Review

productdesign with outsiders.Findout

what

competingfirms orgroups aredoingon similar projects.

Scan theenvironment, inside or outside the orgiuiization formarketing ideas/expertise. Collect technical information/ideasfrom

individualsoutside oftheteam.

Scan theenvironmentinside or outside the organization fortechnical ideas/expertise.

Keep

news

abouttheteam

secret from othersinthe

company

until the appropriatetime.Avoid

releasinginformation to others in thecompany

toprotect the team'simage

or product itisworking

on.Control thereleaseof infomiation

from

the team in an effort topresentthe profile

we

want

to show..618 .515 .404 .791 .719 .424 .645 .491 .587 .823 .817 .592

TABLE

3-REGRESSION RESULTS,

Budgets

&

EfficiencyofTeam

InnovationTeam

Schedules Innovation Rating Operations

(Time 1) (Time 1) (Time 1)

(Time

2) (Time 2)Frequency of