THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE

WEST AFRICAN MOSQUE

An Exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani Models

byAkel 1. Kahera Bachelor of Architecture

Pratt Institute Brooklyn, New York

1977

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1987

© Akel I. Kahera, 1987

The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author _ Akel I. Kahera Department of Architecture 13 May, 1987 Certified by Ronald B. Lewcock, Ph.D. Aga Khan Professor of Architecture and Design for Islamic Societies Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by ___

Pro ssor Julian Beinart, Chairman Departmental mmittee for Graduate Students

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITE OF TECHNOLOGY

MITLibraries

Document Services Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 Email: docs@mit.edu http://Iibraries.mit.edu/docsDISCLAIMER OF QUALITY

Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible.

Thank you.

The images contained in this document are of

the best quality available.

to my children

AZIZAH, ZAINAB

and to MY WIFE,

& HABIBAH

MUFEEDA H

The Architecture of the West African Mosque: An Exegesis of The Hausa and Fulani Models

by

Akel Ismail Kahera

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 13, 1987 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of

Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT

This thesis will examine two models of West African architecture -- the Mosque at Zaria, Nigeria and the Mosque at Dingueraye, Guinea. It will also attempt to illustrate implicit patterns of creative expression, both

literal and allegorical, in the space-making processes of the Hausa and Fulani peoples. In passing, some attention will also be given to the cultural and building traditions of the Mande people. The notion of space and place in much of sub-Suharan Africa oscillates in a realm which is neither absolutely rational nor ethereal. Culture, it could be argued, can offer us an opportunity to investigate an analytical taxonomy through which we can compare and discover particular

attributes of space and the phenomenological dimensions of built form. Culture, as a layered accumulation of historical events, visual vocabularies, and architectural expression, is subject at one time or another to an ethos which may have had a syncretic origin. Among the Hausa and Fulani, the image which exists within the architectural paradigm can be described as a language, or code or a method of explaining spatial concepts related to concrete space and traditional culture. The Hausa and Fulani spatial schemas are concerned with the nature of space as a context and metaphor for experience, inner and outer, hidden and manifest.

Thesis Supervisor: Ronald B. Lewcock, Ph.D. Title: Professor of Architecture

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe special thanks to my advisor Professor Ronald Lewcock, for his

encouragement and interest in the topic, and his valuable comments.

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Labelle Prussin for her

insightfulness and advise. I am also indepted to her for the use of her unpublished research of the Fulani Mosques in Guinea.

My thanks to Professor Alan H. Leary for the use of his Unpublished

M.A. Dissertation.

I am also thankful to my brother for his editorial assistance and his

thoughts on the structure of this essay.

Several people have also assisted me in the research and documentation process and to whom I am grateful: Merrill Smith, Kim Lyon, Omar Khalidi, Adil Seragaldin, Jamal Abed.

Great admiration and respect for Mohammed al-Mahdi of Kosti, Sudan, who often provided me with spiritual inspiration during our long moments together in Jeddah.

And finally to the Fosters, Joe, Frances, Rene, Kermit and Kareen, my extended Family, for their love, support, and understanding.

Al Hamdu lil-laah.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ii iii iv INTRODUCTION Ethno-Historic Context 1 The Mosque as Archetype 6 The Mande Mosque 13 Introductory Notes 22Chapter One:

FULANI SPATIAL PARADIGMS 26

A Primordial Space 28 Numbers, Patterns and Images 35 The Mosque at Dingueraye 41 Notes 51

Chapter Two:

THE HAUSA SPATIAL SCHEMA 53

Fields, Myths and Meanings 55 Forms of Dwelling 63 The Mosque at Zaria 74 Notes 90

Chapter Three:

DINGUERAYE & ZARIA

Image, Text and Form 92

Notes 98 CONCLUSION APPENDICIES Appendix I Appendix I1 Appendix III FIGURE CREDITS BIBLIOGRAPHY

West African Building Types Regional Maps The Sokoto Caliphate and Hausa Cities

iv 99 103 104 105 106 107

INTRODUCTION

ETHNO-HISTORIC CONTEXT

From the 8th century A.D. Muslim trading centers were set up in ancient Ghanal (8th-11th c. A.D.) subsequently influencing all West African empires that evolved, from the Mali Empire (13th to 14th c.), the Songhai Empire (Mid 15th c. A.D.), the Hausa States (11th to 18th c. A.D.) and the Hausa-Fulani, Sokoto Caliphate2 (early 19th c. A.D.). A cultural syncretism developed as a result of the political and economical structure of these empires, which played host to Muslim literary, philosophical, artistic and architectural tradition in sub-Saharan Africa for over a thousand years. Several notable personalities who greatly influenced the artistic, literary, and philosophical traditions of the region are today remembered by the evidence of their works. Buildings at Gao and Timbucktu were endowed by the legendary Mansa Kankan Musa, the 14th century ruler of Mali most

remembered for his hajj (pilgrimage) to Makkah in Arabia (1324-25).3 Upon his return to Mali, Mansa Musa brought an entourage of scholars from the Muslim world with him, among whom was an Andalusian architect and poet; Ibn Ishaq

As-Sahili (d. 1346 in Mali). Ibn Ishaq As-Sahili is reputed to have been innovative in introducing a 'Sudanese' style of architecture in West Africa through the commissions granted to him by Mansa Musa.4 His buildings which are no longer extant, included at least a palace and a mosque for Mansa Musa at both Gao and Timbucktu. Of equal importance was Muhammad Ibn Muhammad Al Fulani of Katsina (Northern Nigeria) an 18th century scholar, numerologist, astrologer and mathematician. 5 Another more recent figure, known for his leadership role in the Fulani jihad of the early 19th century, is Uthman Ibn Muhammad dan Fodio6, who was also of Northern Nigeria. Dan Fodio succeeded in setting up the Sokoto Caliphate after gaining control over most of Northern Nigeria. Remnants of the Caliphate structure are still discernable in the region today. There are many others who have made significant contributions to the development of the cultural and political tradition of sub-Saharan Islam.

West African traditions were readily accepting of other beliefs and as such an Islamic culture flourished affecting all else around it. A synergism in architectural and cultural concepts coupled with the elements of a progressive culture produced a "genesis" or architectural form. Among the most dynamic examples of this is the mosque which has been traditionally a focus of muslim architecture. The "genesis" therefore found a poignant expression in the architecture of the West African mosque. The elements of "time," "space," "being" and "becoming" implicit in the change from transhumance to a sedentary life, are evidence in a conjoining of the Islamic and West African ideas in their architectural dimensions.

Of particular importance and concern to us in this essay is the influence of Islam on the architecture of the Fulani and Hausa people (Figure 0.3). Among the many groups of people7 who inhabit the West African savannah, the Fulani and the Hausa were most affected by the ethno-cultural interaction brought on through the impact of the early 19th c. jihad movements.8

This thesis will examine two models of synergism in West African architecture, the early 19th. c. mosque at Dingueraye, Guinea and the mosque at Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Both buildings were constructed during the early part of the nineteenth century, a period which was witness to several West African jihad movements in the Futa Tora and the Futa Djalon, Guinea and Hausaland, Northern Nigeria. The essay will investigate the ethno-historic and the ethno-cultural elements implicit in the architecture of both buildings -- either connotative or denotative -- imagery and iconology.

We will address the issue of the mosque as an "archetype" and the factors which have influenced its cultural transformation as illustrated in the example of Dingueraye and Zaria. Among the many salient aspects of the architecture of both mosques is the liturgical spatial language and endemic ethno-cultural expression which we have termed "African Space." These features will be elucidated upon in the chapters that follow. What makes the Hausa and Fulani artistic environment essentially significant? The present analysis seeks to evaluate Fulani and Hausa

Fig. 0.3: Map showing the extent of the Fulani-speaking populations. The Hausa-speaking populations are concentrated in Sokoto, Bauchi, Dura, Kano, Zaria, Katsina, and most of Northern Nigeria.

spatial models, and in so doing will attempt to illustrate a theoretical construct implicit in the syncretic nature of built form.

Secondly, in a wider context it will suggest a re-thinking of West African mosque architecture; the elements of style, iconology, and innovation -- whether common or disparate to both the mosque at Dingueraye and Zaria.

Given the syncretic nature of Islam in the sub-Sahara region, it is significant that the cultural and creative genius of the Fulani9 and the Hausa1 0 people would

manifest itself in the Mosque at Zaria, and the Mosque at Dingueraye. The setting both at Zaria and Dingueraye is governed by two general features: an ethno-cultural character and secondly an artistic landscape of the sub-Saharan region in general, and the Hausa and Fulani spatial themes1 1 in particular --themes charged with specific cultural and iconographic meanings represented in

an aesthetic sense.12

Most studies on sub-Saharan Islam have been theological, historical, or socio-political in nature, while studies of the artistic traditions of the region are often isolated from their regional context. There are conceptual difficulties in bringing them altogether, but can one doubt that they are culturally symbiotic?

An authoritative study of the architectural and artistic traditions of the sub-Sahara region must consider both the contribution of Islam and the ethno-historic features inherent in the progressive nature of local culture and building traditions.

THE MOSQUE AS ARCHETYPE

Although the word masjid (Arabic, literally: place of prostration), is fairly common in the Qur'an it does not appear to refer 13 to a prescriptive type of building. The prototypical building used as a place of assembly for worship in Islam is derived from the example of the first masjid (mosque) at Madinah (200 kilometers north of Makkah), built by the prophet Muhammad and his companions after the Hijrah (migration) from Makkah, Arabia (622 A.D.). Some of its architectural features are described by Hassan bin Thabit in a poem written to mourn the death of the Prophet (d. 632-33 A.D.):

In Taybah (Madinah) there are still the traces and luminous abode of the Apostle though elsewhere traces disappear.

The marks of the sacred abode that holds the Minbar which the Guide (to the righteous) use to ascend will never be obliterated.

Plain are the traces and lasting the marks and an abode in which he has a Musalla and a Masjid.

And the Mosque which longs for his presence became desolate with only his Maqam (station) and Maq'ad (seat) remaining as memorials.1 4

The term masjid (mosque) and musalla (open or enclosed prayer space or hall) which occur in one of bin Thabit's verses carry a similar meaning to

jami

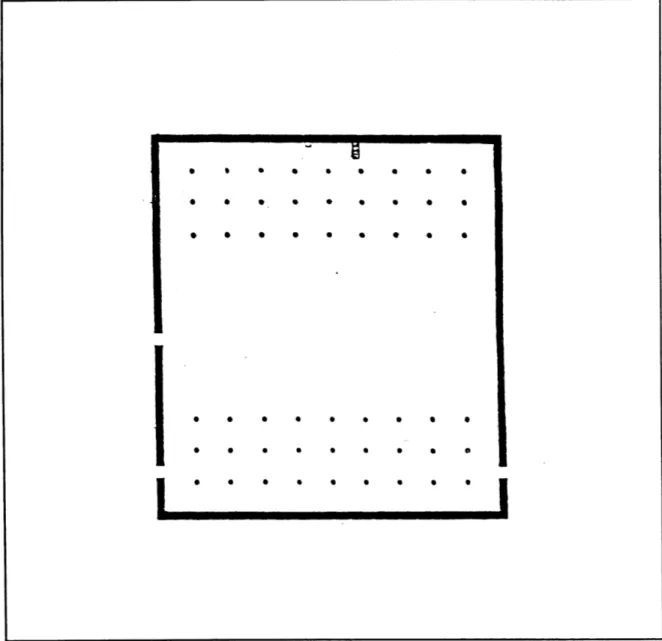

(lit. gathering), they all refer to a designated place of gathering for the purpose of congregational worship.The archetypal spatial form which is commonly called "the Hypostyle" congregational masjid owes its origin to the Prophets' masjid at Madinah which was adopted as a model for succeeding buildings (Fig. 0.4). According to G.l. Besheh (who relies on textual evidence of A. Fikri), the plan of the building at Madinah was a rectangular enclosure with doors pierced in the exterior walls. A portico of three colonnades, each consisting of nine columns was placed along

the qiblah wall (wall in which the Mihrab is placed). The Madinah mosque was

initially constructed1 5 as a walled enclosure measuring 63 cubits (30 m.) from east to west and 70 cubits (35 m.) from north to south. Palm trunks supported a 7 cubit (3.6 m.) high roof of palm leaves and clay. As simple as the Madinah model might have been it nevertheless contained features which can still be found in the architectural vocabulary of succeeding buildings: the mihrab, (a later formal development) a niche in the qiblah wall indicating the direction of the Kaabah at Makkah; the minbar, a rostrum originally of three steps upon which the prophet stood to address the faithful, the minbar which is located adjacent to the mihrab,

Fig. 0.4 The Prophets Mosque at Madinah,

continues to be used for similar purposes; the sahan, or courtyard open to the sky sharing a contiguous relationship with the musalla (covered hall), it is sometimes used when overcrowding occurs in the prayer hall, the musalla, is located immediately adjacent to the qiblah wall. Apparently no minaret or elevated tower existed in the time of the prophet, the adhan (call to prayer) was pronounced from the roof of the mosque or any elevated place, that would allow the voice to carry.

The earliest functional development of the hypostyle mosque outside of the Arabian peninsula (Fig. 0.5) occurred in Muslim settlements such as Basrah and Kufa in Iraq and Fustat in Egypt in the 7th. century A.D. Later mosques in north Africa and Iran all belong to the same generic type. The essential characteristic of the hypostyle mosque is a space that is defined by the placement of columns or piers at regular intervals or bays.

While the hypostyle hall is still employed as an organizing element in mosque architecture, a multiplicity of spatial and ethnic variations can also be identified. "The hypostyle mosque also often became the first type of mosque built wherever a new area entered the Dar al Islam, [abode of Islam] .... Most [early] African mosques of any size tend to the hypostyle. It is as though, at those moments and places when the important cultural objective was Islam...the hypostyle mosque was the architectural form through which the presence of the faith could most easily be expressed...But a more profound explanation is that the hypostyle form remained in the collective memory of the Muslims as the form of an early [architecture associated with Madinah]...."1 6 The cultural variety that exist in the plurality of styles and forms--a departure from the hypostyle form--is a question of adaptability and the creative genius exhibited by the Ummah (the community). "Islam is a civilization (madaniyah) which by its very nature and by its universality embraces a multitude of cultures and styles...It is the plurality of forms and styles that characterizes [Muslim] culture. It is not a culture that may be defined by [an architectural homogeneity or] its material products."1 7 The only consistent form of identification that remains common to mosque architecture everywhere is the orientation of the building towards the Kaabah at Makkah.

Fig. 0.5: An Early 8th Century Hypostyle Mosque at Kufa, Iraq

I

I

I

I

..

.:.1

As a liturgical requirement all mosques must face the Kaabah at Makkah --it is an axis of prayer, which employs the mihrab as --its symbol. Thus, the term

masjid is in essence prescribed by its orientation to the Kaabah, and not by any

physical definition per se. A pious traditional saying among Muslims further endorses this point: "The whole world is a mosque so wherever you may be at the time of prescribed prayer, it becomes a masjid" -- a place of prostration. By

definition then the mosque is at once a prescribed place which an individual Muslim appropriates for worship but at the same time an established place of assembly (jami) whose only liturgical requirement is its orientation -- its axis of prayer. Yet through its historical existence specific examples of a building typology have evolved over time in the development of Muslim art and architecture. "Perhaps the character[istics] of [mosque] architecture may be interpreted more accurately in terms of [its generic] interpretation .... From a purely religious viewpoint, one may even state that [since Muslims acknowledge] Allah [as] the source of all creation, there is no [creative source or] shape without his knowledge and there can be no specific shape that we mortals could define as more 'Islamic' than any other."1 8

The hypothesis presented in this essay is concerned with a search for a more meaningful definition and secondly, it is an attempt to present an argument that recognizes the existence of underlying elements which share a symbiotic relationship in the cultural transformation of an archetypal image.

-=R,

152 w (__41', '

Fig. 0.6: A Simple West-African Musalla defined by a rectilinear edge and a niche (mihrab).

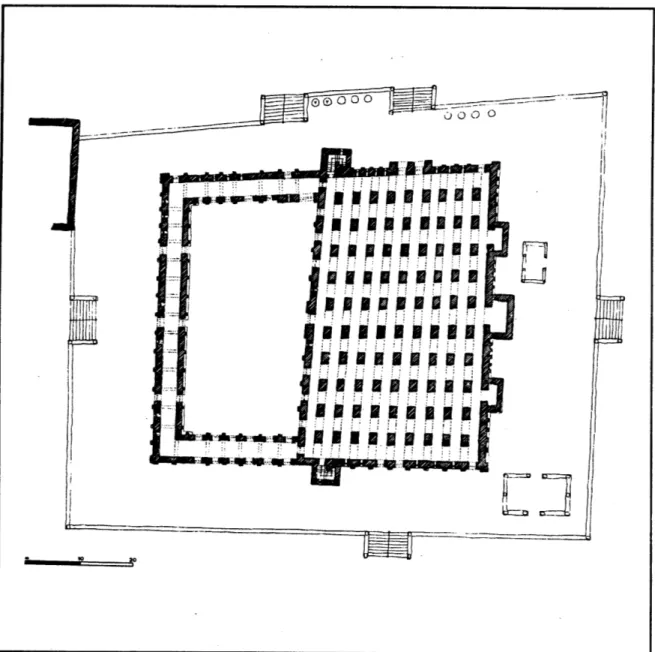

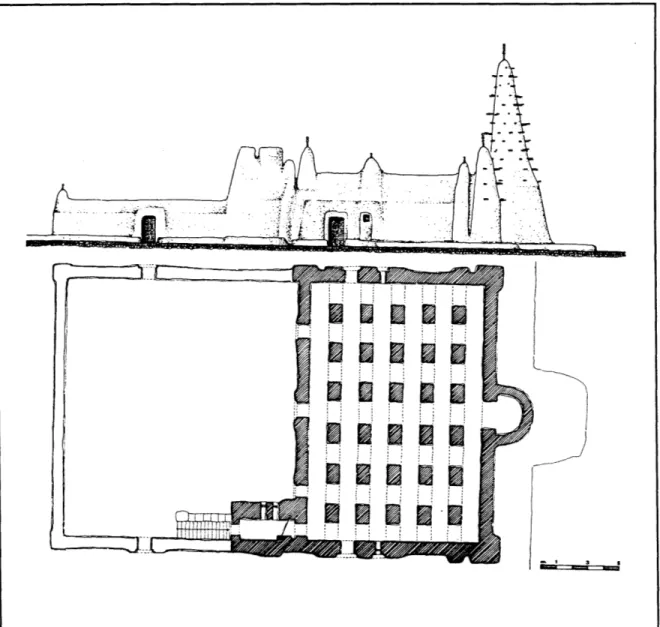

THE MANDE MOSQUE: A Vernacular Hypostyle

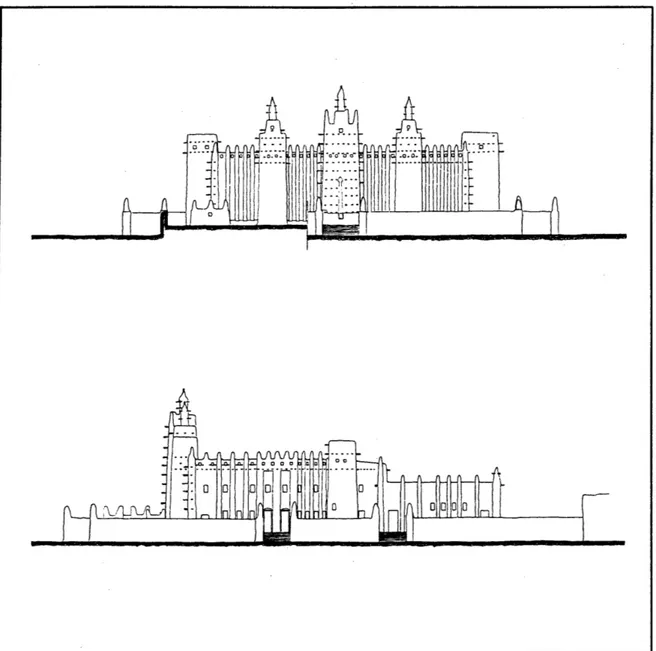

The typological features of the West African mosque are both a product of environment and a cultural imperative. Beneath a genre of stylistic features and visual themes lies an ingeniously syncretic model. Among the Mande19 the geometric grid of the hypostyle mosque assumes such a model in the form of a vernacular rendition commonly known as the "Sudanese" type.2 0 The Mande, in particular the Dyula" ... whose trading settlements ... [carried] the influence of Islam southward [from the northern savannah] to the forest verges during the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries ... [also carried] the basic forms of [the hypostyle] mosque design."2 1 Trading centers at Djenne, Mopti, and San (Mali);

Bobo Dialasso (Upper Volta); Kong and Kawara (Ivory Coast); and Larabanga (Northern Ghana), all contain attributes of a particular style of rectangular clay building, hypostyle in plan, and uniquely idiomatic in its exterior character (Figs. 0.7 - 0.10). The "formal modifications which take place in the mosque as it travels from north to south, [from Timbucktu to the Ivory Coast and Northern Ghana] pertain to size ... scale, structure ... construction details ... [and] deviations from the [hypostyle plan]."2 2 Mud is used consistently in the construction of these buildings, with their exterior walls reinforced with lateral timber members placed at regular intervals -- which also act as scaffolding -- and their roofs reinforced with wood joists. While mud permits great flexibility, it also has several limitations which influence the structural form and character of the building; in addition the facade of these buildings is in constant need of repair. The adaptation of a particular regional style using "mud technology" is therefore influenced by these factors, which in turn, act upon the buildings' aesthetic features. The stability and growth of the Mande trading centers made them capable of sustaining the local community and thus the promotion of architectural variations. "These variations group themselves into five categories: the Timbucktu, Djenne (Mali), Bobo Dioulasso (Upper Volta), Kong and Kawara (Ivory Coast) types (Fig. 0.11)."23 These types share a corresponding correlation with the structure and symbolism of the sculpture, and artistic traditions of the locale. Although a formal vocabulary

Fig. 0.7: Map showing the extent of the Mande-speaking populations.

which are grounded in a cultural and emotional involvement in the local building tradition still pervade. Some of these elements are: the pinacles on the roof paraphet, the triple minaret on the front facade, the buttressing of exterior walls and vertical exterior rib effect.

Because of the nature of the construction techniques, and the building size, walls which enclose the musalla may vary in height (20-25 feet high). The walls are therefore strengthened by buttressing or with engaged ribs or both -- for example, the mosque at Mopti. In most cases these ribs become a series of decorative crenelations of varying size as they terminate at the parapet. The

minarets are always engaged with the building facade and are heavily reinforced

with timber members. The use of domes or vaulted structures are non-existent in West African mosques except in the early 19th c. mosques of the Hausa and a few isolated examples in the Niger which are essentially Hausa influenced. Most mosques have flat roofs with openings for light and air that can be covered in the event of rain.

Courtyards (sahan) are quite small or virtually non-existent, the open space surrounding the mosque acts as a larger extension of the musalla. There are cases of courtyards, however, for example at Timbucktu, the Sankore and the Great Mosque, Djinguereber (jami al-Kabeer).

Rene Gardi and others have also made an analogy with the termite mounds and the ancestral pillars which also bear a peculiar similarity to the architectural elements of some Mande mosques. According to P.F. Stevens, the Dyula [Mande] distinguish three types of mosques, "the seritongo used by individuals or small groups of Muslims for daily prayers, is frequently no more than an area of ground

marked off by stones .... The misijidi (masjicd) or missiri or buru is used ... by Muslims from several households or from a "quarter" for their daily prayers or for Friday prayers if they have no access to a Friday mosque .... The

jamiu,

orjuma

or missiri-jamiu is ... used for Friday prayers and serves the requirements of thewhole "umma" (community) ..."24 In this way the Mande mosque shares a functional definition with the wider community of Islam. While this axiom is valid in

Fig. 0.8: The Mosque at Djenne, Mali-Hypostyle

PlanFig. 0.9: The Mosque at Djenne, Front and Side Elevations

]

---]---

]

]---

E

]-Fig. 0.10: The Mosque at Mopti Mali - Plan and Elevation

Mande Mosque Types

a. The Mosque at Bobo-Dioulasso, Upper Volta b. The Mosque at Kawara, Ivory Coast

c. The Mosque at Djenne, Mali

d. The Mosque at Safane, Upper Volta Fig. 0.11

like the Kawara mosque remain an anomaly (Fig. 0.11 .b). Kawara assumes none of the "formal" vocabulary that is common to the mosque at Djenne, San, Kong, Robo Diolasso or Mopti. Kawara is absolutely fluid and sculptural in its massing, rising out of the ground like great "teeth." "The use of the mosques' (Kawara) interior has been abandoned -- it no longer has an architectural function ... and Friday activities take place in a demarked open space adjoining the symbolic structure."2 5

From this brief discussion of the Mande Mosque, we may therefore assert that a "true" definition of sub-Saharan mosque architecture cannot be limited to an architectural taxonomy of periods or styles, even within a limited regional context, but rather it should acknowledge a more meaningful typology, fully cognizant of underlying elements -- which share a symbiotic relationship in the cultural transformation of the "archetypal" hypostyle image.

Fig. 0.12: The Mosque at Bla, Mali-Plan and Elevation. As seen in this building, the mihrab and the minaret become one -- a common feature of most Mande mosques. The flight of stairs from the Sahan leads to the actual minaret.

Introductory Notes

1. Ghana, literally the name of a king. The trading settlements were apparently located in several areas of the western Sudan between the 8th to the early 13th century, when Mali succeeded Ghana as an empire. AI-Bakri describes one such settlement (between 1067-68 A.D.) as inhabited by Muslims, having twelve mosques one of them a Jami, each had a Muadhin (caller of the Adhan),

Immam (appointed officiant), and Fuqahah (jurisconsult). In the course of Ghana's

long history the town and kings capital was moved from one place to another with the last capital believed to be at Kumbi Saleh (in the region of present day Mauritania).

2. The Sokoto Caliphatre was set up following the conclusion of the jihad (1804-1810), with its capital at Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. For further discussion see Murry Last, The Sokoto Caliphate, Humanities Press, New York, 1972, and J.A. Burdon, "The Fulani Emirates of Northern Nigeria." Geographical Journal 24. 1904, pp. 636-651, also H.A.S. Johnson, The Fulani Empire of Sokoto, Oxford University Press, London, 1967.

3. Mansa Musa spent some time in Cairo on his way to Makkah, he is reputed to have distributed so much gold as gifts, that his generosity resulted in the devaluation of Egyptian gold for almost a year following his departure. See D.T. Niane, Ed., General History of Africa, vol. iv. Heinemann, California, Unesco,

1984.

4. The extent of As-Sahili's influence on the "sudanese style" (West African) of architecture remains a matter of debate; cf., Tor Engestrom, "Origins of Pre-Islamic Architecture in West Africa." Ethnos 1-2, vol. 24, 1959, pp. 64-69.

5. Claudia Zaslavsky, Africa Counts, Lawrence Hill & Co. Westport, Connecticut, 1973, p. 139.

6. See Last, Op.cit., for a thorough discussion on the life of Uthman dan Fodio. 7. Other significant groups include the Dogon, the Nupe, the Mande et. al. The Mande have been significant in the development of a particular type of mosque architecture which differs considerably from the Fulani and Hausa style, e.g. the

Mosque at Mopti, Mali, the Mosque at Kawara, Ivory Coast.

8. The word jihad has been erroneously translated simply as "holy war" by most writers." Its generic meaning is to strive for justice, to be virtuous, to defend, to fight, in accordance with the Quranic injunctions -- it applies to both a community of Muslims or an individual. The literal translation of war is "harb," see N.S. Doniach Ed., The Oxford English-Arabic Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1972.

9. The Fulani also called, Fulbe, Peul, Fellata, Fula, (Bororo'en; bush Fulani, Fulbe Ladde; bush Fulani, Fulbe Na'i; cattle Fulani, Fulbe Mbalu; sheep Fulani, Toroobe: "aristocratic" Fulani, Fulbe Siire; town Fulani). They are scattered throughout West Africa, from Lake Chad to the Atlantic Ocean. They number about 6,000,000 (1970). They are predominantly Muslim, although large groups among them remain animist. The Fulani are principally concentrated in (order of size), Northern Nigeria, Mali, Guinea, Cameroon, Niger. Some of the Fulani continue to pursue a pastoral life although the majority of them have given up nomadic pursuits and have become sedentary. For further discussion see: H.R. Palmer, "The Fulas and their Language." Journal of the African Society, vol. XXII, no. XXXVI. January 1923, pp. 121-130, and C. Edward Hopen, "Fulani": Richard v. Weeks Ed. Muslim Peoples, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1978, pp. 133-139. 10. The Hausa are found mainly in Northern Nigeria and adjacent Southern Niger. They number about 9,000,000 (1961). The Hausa rulers (Habe) were engaged in fighting with the Fulani in the early 19th century

jihad,

led by Uthman dan Fodio a Fulani who was schooled in Sunni Islam. The Hausa-Fulani conflict remains controversial since members of both groups fought on both sides. The Hausa are predominantly Muslim, following the Maliki school of law. They engage in crafts, weaving, farming, pottery, smithery, animal husbandry. The Toroobe Fulani live among, and intermarry with the Hausa and for the most part speak the Hausa language, thus the use of the hyphenated ethnic identity, Hausa-Fulani. For further discussion of the Hausa see: Jerome H. Barkow, "Hausa" in Richard V. Weeks, Op.cit., pp. 151-162.11. For a summary of Hausa artistic themes see, David Heathcote, The Arts of

The Hausa. World of Islam Festival Publishing Co. Ltd., England, 1976.

12. Aesthetics as an intrinsic cultural paradigm, as opposed to "vogue" or a type of "kitsch".

13. Similar references occur in the Our'an, Chapter 9, verses 8-9 (masjid

at-Taqwa; a mosque built on piety) and Chapter 22, verses 40-41.

14. Bisheh quoting Hassan bin Thabit, see G.I. Besheh, "The Mosque of the Prophet at Madinah Throughout The First Century A.H." Unpublished Ph.D. Diss., The University of Michigan, 1979.

15. According to Bisheh, practically all the early Muslim sources which deal with the prophets mosque at Madinah, state that when it was built palm trunks were lined up parallel to the qiblah wall, the northern wall. sixteen or seventeen months after his migration, the prophet received revelation (Qur'an, Chap. 2, verses

136-147), to change the qiblah from Jerusalem to Makkah. The prophets mosque

was altered, a new shaded area of palm tree trunks and a thatched roof was placed along the south wall (the new Oiblah wall facing Makkah) with supports in each colonnade, to the right of the minbar and to the left.

16. Oleg Grabar, "The Iconography of Islamic Architecture," Aydin Germen Ed.,

Islamic Architecture and Urbanism, King Faisal University, Dammam, 1983, pp.

1-16.

17. Dogan Kuban, "The Geographical Bases of the Diversity of Muslim Architectural Styles," Aydin Germen Ed., Op. Cit. pp. 1-5.

18. Ibid.

19. The Mande, Manding, Mandingo, or Mandinka, refers to all the people who are linguistically related to the Soninke and Malinke. Under different names there are Mande speakers in Guinea, Upper Volta, Libera, Ivory Coast, Sirre Leon, and other areas of West Africa. Their expansion from a central nucleus (ancient Ghana?) took place from the 12th to the 19th c. A.D.

20. The term, "Sudanese style," is used in reference to all of sub-Sahara Africa, also referred to in the 12th and 13th century chronicles (Tarikhs) as Bilad as-Sudan, or the land of Black folk. It is commonly used with reference to West

Africa or Western Sudan. Not to be confused with The Republic of the Sudan (Eastern Sudan).

21. A.H. Leary, "The Development of Islamic Architecture in the Western Sudan."

Unpublished M.A.Dissertation, University of Birmingham, 1966, p. 22.

22. Labelle Prussin, "The Architecture of Islam in West Africa," African Arts, vol. 1., no. 2, 1968, pp. 33-74.

23. Ibid.

24. P.F. Stevens, Aspects of Muslim Architecture in the Dyula Region of the

Western Sudan, University of Ghana, Legion, 1968, p. 38.

Chapter One

SPATIAL PARADIGMS AMONG THE FULANI

"The earth becomes the house; the walls are made of clay, the very stuff of the earth. Cracked in myriad ways and weather worn, the mud is held together by finely chopped straw...Birds and wind complete the job. Abandoned, [the] house returns to the earth, and [another] mound is added to [the landscape]."1 This cyclical movement from earth to house to earth depicts the alteration of a "primordial" space, but it also matches the ephemeral nature of the pastoral and settled Fulani, who have adopted a building type to match both a transhumant and sedentary lifestyle.

For the majority of Fulani who inhabit the sub-Saharan savannah of West Africa, habitat ranges from a transient spatial pattern to more permanent compound for instance the Fulani of Mali and the Fulani of the Futa Djallon.

Exigencies of environment limit the geographical center, around which the Fulani lifestyle unfolds. Apart from fulfilling the need for protection against the elements, the Fulani dwelling relies on a way of social life which includes the concept of the extended family, and, or alliances of work to ensure cohesion. This cohesion makes of the dwelling a veritable self-contained unit of existence, with its own unique identity and implicit order, since the family size and consequently its structure also varies.

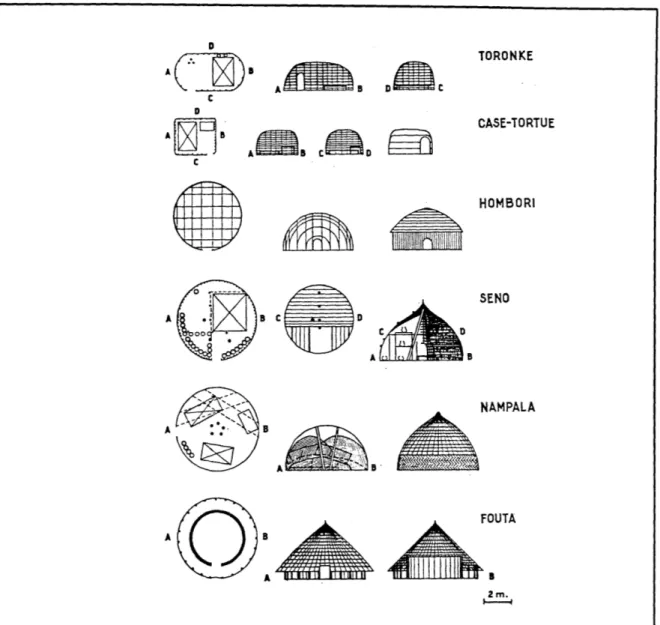

The Fulani dwelling is an ensemble of different types of sheltered constructions (Fig. 1.1). Two main types, the round mud hut with its conical straw roof and the less permanent transient armature tent type suggest regional and cultural variations.

Tent or hut both have a well circumscribed domain. At the same time they are in constant evolution and change, contingent on convenience of site, the climatic season, or contact with other differing ways of life. Historical and ethno-cultural factors also intervene; the movement of people, tribal conflicts, economics and so on, further add to the transformation of built form.

TORONKE A B D C A B C D CASE-TORTUE A D

A

C(B

AmB c SENO CflD AC DB NAMPALA FOUITA AC .B A B A a i2 m.Fig. 1.1: Some Fulani Building Types

HOMBORI

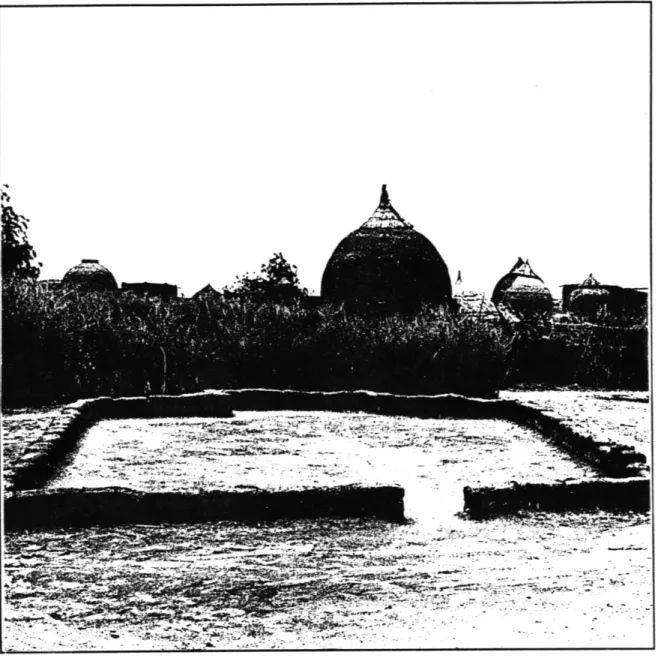

This layering makes the determination of a building typology by origin more problematic. The mosque of Dingueraye "the place where the cattle graze" falls within this category.2 In spite of these constraints, one can still attempt to decode patterns of conceptual and physical modes of architectural expression as well as a methodological and analytical taxonomy of Fulani spatial types.

As a liturgical model of West African architecture, the Dingueraye mosque3 reflects the influence of Islam in a wider context, but as a Fulani building, it is a powerful and revealing primordial space with hidden elements of an ethno-cultural aesthetic phenomenon.

According to C.E. Hopen, "The embracing of Islam [over time] has not led to the breakdown of ethnic boundaries [among the Fulani]...diversity in cultural and social affairs persist."4 If Hopen is right, and we are inclined to agree with his statement, then it would follow that the Fulani patterns of space-making would continue to play an intermediary role between "man" and his built environment, irrespective of another layer of forms having association with Islam and specifically the mosque. If we pursue this argument further, it may become apparent that the designation of a "primordial space" is applicable in the extrapolation of forms of settlement patterns among the Fulani, although, as we stated earlier problematic in the interpretation of their true meanings.

One possible way to approach this inquiry then, is to seek analogies from Fulani "community" settlement patterns, and then to test its validity, and appropriateness against a model, in our case the model would be the mosque at Dingueraye.

A PRIMORDIAL SPACE: The Fulani Compound

In dealing with the "domestic" pattern of the Fulani compound we are not limited to actual dwellings or physical space only, since "domestic" also takes in other forms associated with the "primary structure": of these patterns i.e., the kraal (wuru), the unit (suudu), the palisade, etc., all of these are allied with patterns of

domestic space both sedentary or transhumant. The Fulani domestic unit is in turn linked to a kinship structure, the family, that is responsive to a continual cycle of change (Figs. 1.2 - 1.3). In addition, the symbolic activities connected with this form of transhumance and sedentary lifestyle may vary so widely that it is not possible to offer a general explanation without running the risk of being redundant. However, some key elements should be noted since they are important to a distinction which draws upon the idea of "primary space," and its connection to the normative aspects of Fulani lifestyle. Among the Fulani various categories of activities and relationships exist, having different spatial implications: people/livestock, sleeping/walking, male/female, food preparation/food consumption. These all have to be catered for and are deeply relevant to accepted Fulani customs.

The Fulani compound is organized in different ways to handle the internal ordering of domestic space for these types of activities and relationships. The sedentary compound as an example "...comprises one or more huts (suudu) of daub, or post and matting construction with conical roofs that are enclosed within a post and matting fence in which there is a single entrance. The huts are generally round although...the rectangular form [can be found]."5

Internal divisions of the compound into smaller quarters articulated by fences or palisades are used to regulate access and serve as further definition of spaces and activities. Smaller units correspond to the need for personal space, i.e., single women, old women, wives, a bachelor (Fig. 1.4.b).6 The presence or absence of an entrance hut with an interior and exterior door used as the only means of egress to the compound is also likely, and can overlap as a bachelor's hut. "Guest entrance huts (suudu hobbe), and men's huts (worwordu) are rarer than other types.. .and may either be round or rectangular.... [E]ntrance huts are of little value for anybody except that [Imaam]...who instructs pupils in the Koran (Qur'an)."7 The settlement pattern illustrated above is a normative configuration of a rural sedentary Fulani compound in the West African savannah.

Parc

Par c

parc

(9

Fig. 1.2: A Pastoral Fulani Camp, Mali (near Yelimane)

- Parc : Cattle kraal (wuru)

- H, F, C, J, etc. : Kinship family units (suudu)

69

L~7

Fig. 1.3: A sedentary Fulani (suudu) Compound, Northern Cameroon. The compound was divided following the death of a senior male family member.

Earthen bed

7K,4"

The suudu in the Futa Djallon

a. A Fulani Woman of the Founta Djallon, Guinea

b. Plan of a Typical Sedentarized Fulani suudu at Timbo, Guinea c. The vegetation of the Futa Djallon, Guinea

d. A suudu, Futa Djallon, Guinea

granary above

Fig. 1.4:

Fig. 1.5: A Transhumant Fulani Family

-p

ap

Fig. 1.6: Central Pillars

a. Floor plan of the mosque at Dingueraye

b. Central pillar in a Hausa Unit, Upper Volta

c. Central pillar in a Fulani unit, Niger

In another case the transhumant kraal consists of structures which are relatively impermanent and contain a set of different variables and features.

The transhumant tradition is "...reflected in the ubiquitous fulfillment of the most minimal definition of.. .spaces...demarked by a [circular] tapade or palisade, sometimes by an acacia hedge, sometimes, depending upon the season by social behavior itself."8 (Figs. 1.5 - 1.6). The relationship of the enveloped circular domestic space in contrast to a public space circumscribed and defined as a

musalla is particular pertinent to the hypothesis of this essay. The transformation

of this spatial paradigm into a more formal"... Islamic context is best illustrated by the mosque prototype.. .to the uninitiated visitor [to Dingueraye] there is little to distinguish in the palisade wall of such a "mosque" from the tapade, [since it is so similar to the tapade] that encircles the family wuro."9 In essence, it is in indigenous expression of "space making" in a temporal setting. However transformed into a geometric "fit," it becomes a matter of cultural definition.

The validity of this argument further suggests an understanding of the configuration--of pattern and usage--implicit in the Fulani mosque at Dingueraye

and similar models that are common to the immediate region.

NUMBERS, PATTERNS, AND IMAGES

"To understand human ... creation we have to find where in experience [forms, patterns and images are] grasped or locked into place... Things are active -- they do not just exist."10 One of the 18th century Fulani scholars, Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Fulani1 1 developed a scientific theory of numbers and their composition, which he called /m al-Asrar (the science of secrets) (Fig. 1.7). /m al-Asrar is a science which deals with a creative use of patterns of numbers, to

obtain insight into esoteric knowledge. As a formula it deals with a rational construction of odd and even numbers, but by extension it could well be a scientific rotation about the axis of a square. In his writings, Muhammad Ibn

4 9 2 2 9 4 6 1 8 8 11 6 3 5 7 7 5 3 7 5 3 3 57 8 1 6 6 1 8 2 9. 4 492 1800 V2 AXIS A B C D 2 7 6 4 3 8 8 3 4 6 7 2 9 5 1 9 5 1 1 5 9 1 5 9 4 3 8 2 7 6 6 7 2 8 3 4 900 2700 E F G H

Fig. 1.7: Patterns of Numbers developed by Muhammad lbn Muhammad al-Fulani in his theory of /m al-Asrar (the science of secrets).

they do not just exist," then "how" are they so? How can we illustrate this by using the Fulani spatial paradigm as a valid construct of this hypothesis?

Many scholars1 3 purport the notion that differentiated spaces can in fact manifest more than one meaning from within, very much like the diagram in figure 1.7. It is a series of numbers, but it is also numbers with hidden meanings, and yet still patterns of meanings, since a pattern need not always agree with its meaning or in architectural terms the image need not always agree with the object.

These statements are concerned with axioms, our inquiry deals with pattern and image, apropos to the Fulani spatial ethos. By example we may examine three images which are analogous to our argument.

Image one (Fig. 1.8.a) is a diagram made by al Hajj Umar Tal for the Dingueraye mosque.

Unlike the actual plan of the building this diagram is directionless, which runs exactly counter to the importance of the mihrab --the directional niche on the

qiblah wall of all mosques, musallas and places of prostration. The absence of

some form of indication of a horizontal axis, makes the image read like a decorative pattern rather than an architectural diagram. Furthermore, it bears a striking resemblance to the embroidered design of a ... "tilbi -- a robe worn exclusively by older women in Oualata, Timbucktu and Djenne (Fig. 1.8.d)."1 4 One can argue that the tunic pattern has a stronger sense of direction that Umar's diagram. The second image is a close parallel to the diagrammatic plan made by Umar. This diagram is intended for use as a conjurant for good luck when filled with texts, it is also a more accurate representation of the Digueraye mosque plan and figure 1.8.a. In addition, "the concentric circles recall ... the perimeter ambulatory... tapade, or palisade fencing around the [wuuru]. Thus the square is enveloped and hidden within its ...concentric circles like the core of a suudu."15 The third image (Fig. 1.8.c) is quite identical to the regulated square pattern used for numerological ordering of patterns of numbers in Muhammad al-Fulanis' theory, which we discussed earlier. "The strong preoccupation with numerology in the sufi tradition in the Futa Djallon is evident in.. .[various] kinds of magic

Fullani Patterns

a. Diagram for the mosque at Dingueraye made by Al-Hajj Umar Tal

b.&c. A diagram used as a "conjurant" (charm) when filled with texts.

d. A Tilbi - embroiled design on a robe worn by

older women in Timbucktu and Djenne, Mali. Fig. 1.8:

But this image could very well be considered a "...close approximation of the framing plan of smaller West African mosques, in which transverse beams rest on a set of four pillars and on the square perimeter walls."17

All of the images considered implicitly convey an architectonic pattern. On one level these images, when read as text, are quite literal and denotative since they convey a message. On another level if they are read as diagrams they define a conceptual space, perhaps as an expression of a conscious association with a message.

We may choose to read them as a geometric template of numbers, or even as a form of structural imagery and Fulani iconography.

Fig. 1.9: The interior ceiling pattern of a Fulani

THE MOSQUE AT DINGUERAYE

Amidst the fervor of the 19th century jihad movement in the Fouta Djallon, Guinea, a unique idiom and expression of mosque architecture was born (Fig. 1.10). As a style it is quite remote in its physical attributes from the conventional themes played out in North African building types or the syncretic renditions of the Mande savannah mosques, or the building traditions which characterize Hausa architecture. As a product of a period that was influenced by the thinking and ideals of al Hajj Umar Tal, the proponent of the jihad, Dingueraye is a living reminder of a human event. Al Hajj Umar Tal, (his proper name: al Hajj Umar ibn Uthman al-Futi al-Turi al Kidiwi, b. 1794-d. 1864), was well grounded in Quranic teachings from an early age, under the tutelage of his father, a Muslim cleric. Attaching himself to the tariqah at Tijaniyah (Sufi Brotherhood) at a later age, he was responsible for spreading its teachings in the western Sudan. A panorama of events further shaped Umar's thinking. In combination, his interest and affiliation to the Brotherhood, theological teachings, and his quest for further knowledge, took Umar on a sojourn--1814 to the 1840s--from Guinea to the Fouta Djallon, Sokoto, Northern Nigeria, Egypt, Makkah and back to the Fouta Djallon and Dingueraye via Sokoto.

The jihad was linked to Umar's stay at Dingueraye 1849-53 "...it's function was at once spiritual... In this respect [Dingueraye] served one of the principal functions of a ribat, a place from which Dar al-Islam [abode of Islam] might expand..."1 8 The extent to which Umar's influence can be attributed to the

architecture of the Dingueraye mosque is sketchy. His diagram for the mosque, bears a very remote similarity to the actual plan of the building.

It is noteworthy, however, to consider Umar's travels as instructive in his conceptual ideas for a liturgical space, given the universality of the faith. The image that immediately comes to mind when reading Umar's diagram is the

Kaaba (lit. the cube). Apart from its universal significance in Islamic belief, it can

also effect an architectural model, a priori. The Kaaba (Fig. 1.11) in architectural terms, is capable of evoking a simple aesthetic, since it is not surreal, fantastic or

0 5 10 20 30 FEET

Fig. 1.12:

Mosques of Guinea

a. The mosque at Dingueraye, Guinea

b. The mosque at Kamale Sibi on the border of Mail and Guinea

c. Ambulatory of the Mosque at Dingueraye

d. The mosque at Sarebodio, Guinea

Schemtnattc Section nts.

0 5 10 20 30 FEET 0 5 10 20 30 FEET

Yet still it is a conscious reference to the past, Muslim prophetic tradition and escatology.

It is quite possible that Umar could have been inspired by the image of the

Kaaba during his extended stay at Makkah. But the Dingueraye mosque is not the

bold image that the Kaaba evokes. At Dingueraye the cube is hidden beneath the umbrella of the roof, the roof acting as a climatic device and not contingent with the language of the cube (mosque) per se.

The second possible definition is semantic in nature. The Dingueraye mosque may be regarded as historic-typological model, since its architectural language is partially rooted in a spatial language inspired by Fulani themes of the locale, while making use of a historical typology; that of a hypostyle hall with columns placed at regular intervals.

We may also argue that the building has a morphological appearance, its sloping roof being insignificant to the inner pre-ordained system -- which creates a fusion of "imitation and allegory" both evident and ambiguous. It is too tempting to reduce these aspects of the mosque's architecture to symbolic and allegorical meanings without considering the "nature of image" further.

Dingueraye has its roots in the attitudes of a complex world of the transhumant and sedentary Fulani, which we cannot ignore. "The Fulani jihad was the first instance in which nomadic sedentarization and hegemony occurred concurrently... .The visual imagery of the tent, ...the spatial organization of nomadic space lent itself with the greatest of ease to [a new mode] of spatial orientation [the mosque],"1 9

In considering the Fulani-inspired Dingueray mosque, two modes of spatial layering are evident. The first layer is an ambulatory space which circumambulates a cube, the actual mosque. The outer layering, the skin, is very much like the Fulani sedentary hut (Fig. 1.4.d), enclosed by a palisade wall which demarks an edge. In the nomadic tradition this circular space is quite evident. According to local custom at Digueraye this outer layer is changed every seven years, at which time an elaborate ceremony is held for the occasion.2 0

HRAB

U U

U

M N

FD1

Plan of the mosque at Dabola, Guinea U

U U

U

RETAINING WALL

POTERIE I

ABLUTION

S* S. 0.00

Fig. 1.15: Plan of the mosque at Mamou, Guinea

S 0 S

The second layer of space is "the cube itself [which] has heavy earthen walls and an earthen ceiling supported by ranks of columns."2 1 Three openings

in the wall of the cube are quite symmetrical except for the one opening on the qiblah wall. These openings are repeated again in the exterior skin of the roof structure approximately adjacent to the ones in the inner cube (Fig. 1.13). A central post supports the exterior roof structure from within the cube, like a great

big tree it radiates to its outer roof (Fig. 1.13). "But the central post, the perimeter columns, and the thatched roof dome are structurally separate from the earthen cube within"2 2

In the examination of similar buildings of the region; the mosque at Mamou and the mosque at Dabola, Guinea, the central post is retained (Fig. 1.14 and 1.15). The grid layout used for the post which supports the roof of the cube incorporates the central post. It appears also that posts in the outer ambulatory adjacent to the openings were carved.

Unlike Dingueraye, the mosque at Mamou and Dabola, inner cube have singular openings in the perimeter wall very much like the openings in Umar's sketch. The position of the central post at Dingueraye and Mamou also approximates the central element in Umar's diagram. More interesting is the placement of pottery jars (ablution vessels) at the entrance of the Mosque at Mamou. Are these patterns and the elements they employee and the image they convey simply visual metaphors or are they a concrete rendition of a Fulani spatial construct?

Our remarks and observations have addressed the "nature of image," and "the idea of space as a cultural metaphor" implicit in the architectural themes of Dingueraye. The question of the mosque as a culturally distinct model, a native rendition, both in its temporal and spiritual realm is without parallel.

In conclusion, we would therefore argue that the building is an orderly mix, it bespeaks a sense of imagination and perception and a practical understanding of built form, which further reflects a mode of thinking, equally relevant to those who created it and those who worship in it.

0-J

Chapter One Notes

1. Plesums Gantus, "Space and Structures In a Primordial Folkhouse."

Architecture vol 75, no. 10., October 1986, pp. 60-63.

2. "The place where the cattle graze," was obtained from a citizen of Dingueraye, Mr. Ibrahim Cherif.

3. There appears to be some discrepancy as to when the mosque was actually built according to Labelle Prussin it was built in 1883, by the family of al Hajj Umar Tal. Mr. Ibrahim Cherif claims that according to local oral tradition, Umar himself dug the holes for the building during his stay at Dingueraye.

4. C. Edward Hopen, "Fulani," in Richard V. Weeks, Ed., Muslim Peoples,

Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1978, p. 136.

5. David Nicholas, "The Fulani Compound and the Archaeologist." World Archeology vol. 3, no. 2, October 1971, pp. 111-131.

6. A bachelor whether son of the house or laborer, will invariably have or share with another a hut (jereeru) built near the circumference of the compound where his friends may visit him without penetrating into the women's quarters (Nicholas,

Loc. Cit. 1971).

7. Nicholas, Loc. Cit.

8. Labelle Prussin, "Islamic Architecture in West Africa: The Foulbe and Mande Models." V/A 51982, pp. 53-67, 106-107.

9. Ibid.

10. Abraham Edel and Jean Franckensen, "Form: The Philosophical Idea and Some of its Problems." VIA 51982, pp. 7-15.

11. His full name is Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Fulani al-Kishnawial-Sudan (from: Katsina, the Western Sudan), see A.D.H. Bivar and M. Hiskett, "Arabic Literature of Northern Nigeria Up to 1804." Bulletin of SOAS, (London U.) XXV:1, 1962, pp. 104-148.

12. Claudia Zalasky, Africa Counts, Lawrence Hill & Co., Westport, Connecticut. 1973, p. 139.

13. For example, see Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place, University of Minnesota Press, 1977, and Mircea Eliade, Images and Symbols, Harvill Press, 1961, et.al. 14. Labelle Prussin, Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa, University of

California Press, 1986, p. 147.

15. Ibid, p. 228.

16. Ibid.

17. Prussin 1982, Loc. Cit.

18. B.G. Martin, Muslin Brotherhoods in 19th Century Africa, Cambridge University Press, 1976, quoting J.R. Willis, "al-Hajj Umar b. Said al-Futi al-Turi (1794-1864) and the Doctrinal Basis of his Islamic Reform Movement in the Western Sudan." Unpublished Ph.D. Diss., London University, 1971, pp. 88-89. 19. Prussin 1986, Op. Cit., p. 231.

20. According to Ibrahim Cherif a native of Dingueraye. 21. Prussin 1986, Op. Cit., p. 228.

Chapter Two

THE HAUSA SPATIAL SCHEMA

"Before He created woman, says the legend, God made a hut, and He shut man up in it. God brought him out of the hut in order to show him his wife. The [mythical] hut, the image of the cosmos is found in [most] liturgies of initiation throughout Africa: [it gives] a liturgical significance to human habitation, which not only follows the laws of cosmic order, but also the individual and social structure of

man."1

For many scholars, unfortunately, African architecture stops short at the image of the "mythical hut"; where as it is something quite different. African architecture is among other things a communicative system, a means by which African folk "demonstrate" on earth; and in the process of conceptual space making, create meanings, values and a way of life.

The artistic character of building surfaces, workmanship, and iconology, employed in the Hausa building tradition, is "invested" with a common message that is invariably social. Furthermore, a house is not only a roof and four walls, it is a walled garden, a courtyard, a compound; where friends are received, where people dance and sing and where religious rites are held. Other arts of life spring to life there also, it is there too that one learns to speak, to cook, to venerate family

and ancestral ties.

In the first place, the architecture of the Hausa dwelling, the mosque, the palace etc., is consciously thought out. It responds to climate, security, function and the social mannerisms of its inhabitants and users. The choice of materials used in construction is further governed by indigenous means and a building tradition which lends itself again to the prevailing life-style of the immediate community. The Hausa compound like the village and city structure is an ordered hierarchy of spaces which adhere to an implicit cultural paradigm. If we extend our observation to include a study of the underlying social and belief structure (the deep structure), we would recognize "patterns" of spatial ordering, coupled with a

Fig. 2.1: The Layout of Hausa Fields

I-COMPOUND LAYOUT KQP3

GDK 0 K 0 F a Z K CITY PLANNINGthe city alike. This implies above all that the "Hausa schema" of space making is both temporal and ethereal; equally pertinent to the development of this hypotheses.

FIELDS, MYTHS AND MEANINGS

"In [pre-Islamic] traditional Hausa society the layout of fields, houses, granaries and towns are governed by an ancient cosmology which regulates numerous facets of daily life." (Fig. 2.1).2 Employing a spatial schema, defined by the cardinal points, geometric patterns are fixed where the axes of the points meet as seen in the examples used for setting out a field, sowing crops, defining a compound layout or in the layout or a city. This conceptual space and its constituent geometry is manifested in the axial layout of Zaria (Fig. 2.2). Ultimately, it responds to and is reinforced by a bi-annual procession, from the northern gate of the city around the city walls, to the south westerly gate and from there back to the palace along a north eastern route. The emir of Zaria is followed on horseback and on foot on this route by an entourage consisting of royalty and the residents of Zaria -- on the occasion of two festive Muslim holidays (Eid al-Fitr

and Eid al-Adha). Two days later yet another procession follows a north-south

axis to the southern gate of the city (main gate).

"[A]t the [center] of the spatial sequence in the city structure is the dendal a vast area in front of the emir's palace adjacent to the mosque.... It is interesting to note that the dendal in Zaria itself lies between the out crop or rock used for traditional dancing and the Friday mosque" (Fig. 2.3).3 The axial north-west-south-east and south-west-north-east is remarkably similar to the setting out of the Hausa fields, which are always rectilinear (square or rectangle), with an important axis facing north-west-south-east.

The Hausa mythic structure like the ordering of geometry in a field has a concomitant reference to architectural elements associated with the city, for instance its peripheral gates, the door to the house, and windows. One legend has it that the rise and fall of ruling Hausa dynasties are associated with the mythical peculiarities of certain palace gates and city gates.

P Palace

D Dandali

M Market K Kofar Madarkaci Hill KP Katsinawa

Prayer Ground

MP Mallawa

Prayer Ground

PROCESSIONAL ROUTES

Kuyamban 3 1..-At Sal la.Katsinawa Route

-2--- It If Mallawa '

NI''IC 3--..Two Days After Salla

K G a

Yan'+..-0 40. goo 100 %o. '20.0 M