THE APPLICATION OF MUSIC IN INDUSTRY AND ITS EFFECT UPON THE MORALE AND EFFICIENCY OF THE WORKER

by

John H. ScottJr. W. Scott Libbey

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Bachelor of Science Degree

from the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

1 9 4 3

r

Name brLJ D .tt,. .Jr.

9 Te Appic.ato.n .. fMusc-in jrtduztxy-azcjJtsEffec. upan-_thLe M-rale-and-Eficlenay .of-the-Worker

This is your authority to proceed with the thesis investi-gation as outlined in your preliminary report. Please return this sheet with the original copy of the finished thesis.

Signature of the Advisor, indicating completion of a

sat--isfactory preliminary report.

Advisor

Signature of the Supervisor, indicating proper registration fo- redit, and generally satisfactory progress.

M. I. T. Graduate House Cambridge, Massachusetts January 11, 1943

Professor George W. Swett Secretary of the Faculty

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts

Dear Sir:

In accordance with the requirements for graduation, we herewith submit a thesis entitled, The Application of Music in Industry and its Effect upon the Morale

and Efficiency of the Worker. We wish to express our gratitude to Professor Douglas McGregor, who has been extremely helpful in the organization of our material.

Sincerely yours,

QJ

John H. Scott, Jr.

W. Scott Libbey

Scope 3

Method 4

history 5

Sumiary 7

The Effects of Music 12

Psychology of Music 13 Rhythm 14 Morale 15 Fatigue 22 Physiological Fatigue 22 Psychological Fatigue 24

Decreased Capacity for Doing Wvork 26

Fatigue and the Production Curve 26

Stimulation 29

1Noise 29

Production 31

how Morale and Fatigue influence Cost 31

How Music Saves Time 32

Obtaining Reliable Data 33

Daily Production Curves 36

Possibility of No Effect on Production 38 Scientific Experiments on the Effect of Music

on Production Rate 39

The Operadio Experiment 55

Further Evidence of 1viusic's Effect

on Production Rate 56

Waste and Quality 57

Safety and health 61

The Application of Music 63

Conditions Under Which hiusic Can be Used 64 Physical Conditions 4hich Must Be Considered 65 Characterjstics of the Work and Worker 68

The Music Installation 75

Ways of Obtaining the Music 7b

Equipment 78

Availability of Equipment 81

The Psychology of installation and Operation 82

The Operation of the System 83

Times and Types of Music 85

The Time to play Music 86

The Type of Music 95

The Music Program: Times and Types

in Combination 107

109

-I

Further Uses for the P.A. System 110 Difficulties iihich May Be Encountered 112

Conclusions 114

Recommendations for the Future 116

Appendices 118

A, Employer's Attitudes 119

B, Reported Effects on Production 123

C, The Music at Work Program

of Radio Otation WNYC 126

D, Record Lists 128

E, Case Histories 134

F, Views of the £vanagements of

British Industrial Companies 142

2

PURPOSE

The purpose of this thesis is to prepare a report which will set before a manufacturer considering the use of music the facts relative to its application and its effects upon the morale and efficiency of the worker. It is our hope that all of our major premises will be carefully weighed by the manufacturer in view of today's existing knowledge, but we must first pass out the warning that so little scientific work has been carried on in

this phase of industrial welfare, that no sure-fire

answer has been found for every question. Our presenta-tion attempts to correlate all available informapresenta-tion as of the present date. Although we are undoubtedly preju-diced toward the use of music, we shall try to maintain a spirit of impartiality.

place in the industrial organization. Instances of in-creases in milk production by the use of music in barns has come to our attention, but we feel that the limita-tions of our work will exclude the study of music on the farm. We have also placed restrictions upon the method

of transmission of music to workers. All glee clubs and band concerts, participated in by the worker, are elimi-nated. Our sole concern is with the use of music played to the worker, no matter how it is presented.

Although music played during working hours is our chief interest, rest period and lunch hour music will also be considered. The factory worker receives most of our attention, but the effect of music on the clerical

4

IMTHOD

For the gathering of our information, all available literature for the past twenty years was first searched. We were thus able to obtain about two hundred names of persons, organizations, and companies displaying interest in music in industry. The main body of our material

has come mostly from our contacts with these two hundred corresoondents.

For centuries music has been playing a significant role in man's work life. Old sea chanteys of the sailors and the use of music in the building of the pyramids are evidence of music's early prominence in history.

The first recorded case of the use of music in the modern age is probably Thomas Edison's attempt to use

phonographs in a cigar factory. The failure resulted from too much noise which could not be overcome by the weak volume of the phonograph. The necessity of good

electrical reproduction was the temporary fly in the ointment. In 1925, Westinghouse Electric Co. at its Newark plant, successfully introduced the playing of

records over its loud speakers, but the idea remained rather dormant until the advent of the British studies in 1937. Studies of industrial music were made due to the activities of equipment producers and the interests of the British Industrial Health Research Board. A great impetus was given to music in industry in 1940

by the desire to improve morale and increase production

for the benefit of the war effort. Foilowing the British lead, manufacturers in the U.S. are just awakening to the potential value of music in industry. The timeliness of our investigation may be shown by the estimate that last April only 500 plants employed music, while in July, the

6

number had risen to almost 3,000.1

1. Antrim, Doron K., "IMusic for All-Out Production,"

8

kusic has two psychological effects. A spirited melody brings a feeling of gaiety, while a melancholy one produces listlessness and somberness. By the application

of the known effects of music, it is possible to use music to advantage in the improvement of the morale and efficiency of the industrial worker.

Morale denotes the worker's will to work and satis-faction in his job. Because music provides a genial atmos-phere and indicates to the worker that management is inter-ested in the welfare of its employees, the worker feels happy in his job and way of life. Poorly chosen music will not have beneficial effects, but good music, properly reproduced will help form a bond of friendship between workers and management.

The repetition of one task will soon result in fatigue. Whether the fatigue be caused by physical inability or men-tal tiredness, a decrease in production will result.

Numerous scientific investigations have shown music's effect upon us mentally and physically. 6tudy of these findings in conjunction with an analysis of the periods of highest fatigue lead to the choice of the most opoortune hours to play music.

Management's ultimate interest in the value of music usually concerns its effect upon production. 'The easiest way to effect a production increase is to improve the morale

and reduce the fatigue of the worker. Any study of music's effects on production entails the necessity that all other working conditions remain constant. Only two tests under controlled conditions have been made: (1) by Wyatt and

Langdon of the Industrial Health Research Board, Great

Britain, and (2) by Prof. Burris-Meyer of Stevens Institute

of Technology. In both instances, the use of music has brought about an increase in production, while its elim-ination has been followed by a production decrease. It must not be assumed that music will always increase production, however.

The application of music warrants a great deal of consideration. For maximum results music requires that there be not too much noise, a concentration of workers, and monotonous work. Individual variances among employees, such as musical training, proportion of men to women, age, and nationality influence the type of music. Employee requests should be used if in accordance with the general program of music.

Music in the industrial plant may be obtained in numerous ways. The Viuzak Corporation specializes in "piped in" music while R.C-A. Manufacturing Company

puts installations in plants. However, a number of com-panies prefer to make their own installations. WNYC has a noon hour program for radio-equipped plants in the New York area. Operating costs under any of these

10

set-ups is insignificant. Present shortages of Olectrical reproduction equipment raise difficulties in obtaining a music installation, but the feat is far from impossible.

Workers sometimes get the idea that the music is being introduced to cause them to work faster; this impression should be discouraged.

Almost anyone can operate the music system. This task often falls to the telephone operator. The record library grows larger as it is kept alive with new tunes furnished by the company, and additions sometimes made

by the employees. Control of the entire music program

and installation should be under the supervision of the Industrial Relations Department.

Probably the most unexplored field in industrial music concerns the times and types of music which should

be played. Rules are few and conflicting, and are of doubt-ful quality. Yet, usually any music is better than none.

The worker is not interested in having music at the times and in the amounts which will do him the most good. But our main consideration is to give the worker what is best for him. One must not use more than one or two hours of music a day. One should preferably schedule music

only after ascertaining one's own production curve, and determining where the music will do the most good.

A careful study of the characteristics of the

work-ers in the plant is the first necessity in determining the type of music to be pieyed. Several "comimoln denom-inator" types can be discovered which will suit almost

anyone in the plant. There are a number of characteristics of particular types of music which must be kept in mind in order to use these types to best advantage.

Particular music periods require particular types of music. One's final program is obtained by determining

both the times at which Lusic is to be played and the music which is to be played at each of these times.

12

TBE EFFECTS OF MUSIC

Music has a psychology of its own. While it is one

of the least tangible arts that affect our sense organs,

it is also one of the most effective. Everyone knows that when certain pieces are played, old experiences are recalled, emotions which were felt when the song was first heart become attached to the melody of the song, and an emotional surge is brought forth by the musical strains.

1.

As we look at the effects that music may play upon our mental-being, two changes of mood can be detected. First, if a slow, lilting and rich melody is heard, the tendency will be for a calming effect upon our nerves and senses. A feeling of peacefulness will overcome our minds. On the other hand, a fast, highly spirited tune will awaken our emotions to the point of gaiety and possibly bellicos-ity. As we proceed to expand our thesis, the ways the

2.

above knowledge may be put to practical use may become clear.

1. Crane, G. W.,"Psychology, Applied,"p. 347.

2. Scott, Cyril,"Ginger Up Your Brains With Music, Etude, November 1931, p. 773.

14

RHYTHMA

Strangely enough, the first thing that we are going to discuss about music is something which music does not normally do. There seems to be a rather prevalent miscon-ception that the main reason for the use of music in

industry is to increase the speed of the worker by forcing

the rhythm of his operation to become faster. This is supposed to be accomplished by picking music with a rhythm slightly

faster than the operation rhythm, and playing this music to the worker. And the worker is then supposed to speed up so he can keep in time with the music.

A few cases have been found where music has operated on

the worker in this way. But look at the difficulties which would face the arranger of the program. It would mean

that all the music played would have to have precisely the same rhythmic speed. The music so picked would probably be

adapted to only one type of operation in the factory. And this system could be used only where the operations were of a one-two or one-two-three nature, which is seldom

the case.

In the following pages we are going to point out the real reasons for the use of music.

MORALE

Morale is an idea that can not be properly defined or measured. One person will say that it is the general spirit of mind and feeling expressed by the worker, while another will argue that morale denotes the worker's atti-tude towards his employer and job after economic reasons have been put aside. If the worker enjoys doing his job, his morale is high; if he hates his job, his morale is

considered low. As David Sarnoff of RCA Manufacturing

Co. Inc., has said, "morale is a state of mind."1 Morale

typifies the mood of the employee's thoughts. Unfortu-nately, morale is so intangible that no simple index can be used to measure it. Almost all conclusions must be based on personal opinions, the exactness of which is open to question.

The factors that may affect morale usually include rank of employees, success of employee, supervision, earnings and working conditions. It is under working conditions that music is included. Music becomes part of the atmosphere and surroundings that influence either positively or negatively the employee attitude. If music can help to change tangible and measureable items of em-ployee efficiency, it must be conceded that morale has

1. "Building Morale for Increased War Production," E. C. Morse, R.C.A. Manufacturing Co., 1942

16

been influenced.

Professor Burris-Meyer's recent tests1 . show that the early departure of piece-work employees, free to leave when they please, dropped from 22.75% to 2.85% when music was introduced. A graph of this is illustrated in Fig. 1. Manufacturers have claimed that since music has been used the rate of turnover and absenteeism has taken a definite drop. Monday morning absenteeism was decidedly cut by the use of music in the test just mentioned. Fig. II shows the results. Due to many possible changes of other condi-tions and unknowns some skepticism is warranted. Conse-quently the desire to work must now be stronger than previous to music--morale is higher.

To bear out our point that morale must be measured more by opinions than by figures (except in above cases) a few statements and facts are presented. In one company, an employee in a non-music department asked to be trans-ferred to a music department because he considered music essential to the happiness of his job. Several companies have granted employees' requests to bring in their own radios. Music installation at Westinghouse's East Pitts-burg plant was made to fulfill the desire of employees. At Botany-Worsted, 97-99% of employees voted after in-stallation that they liked the music,

1. "Music in Industry " Prof. Harold Burris-Meyer,

Stevens Inst. of ±ech., an address before the

up.Tt

I

T

'

.4 4ItHkviti

-r-

4 -:1--H

13 -4 - .1. 4-2 ~ 4W ~ 1~ -h I I I 7 -I . I H- ~---1--

--L 1 :111:: 2 Ii: 2:24.1:4:4 --- F----. -77--t -. 1 -- 4 t742l <I I<-v--

~H

~.- -- I - - H - ,--. I I~

I

±V

+

-4 ---.-- - .~1~

4<

-4 --.4---

I727 i7;7117

rr I T7T:

T~

Jh17

17-17'7jHid

F;<L

-i

F- L-LL El 71 F r II Li4~ <I .-1 i-H-U 27.7FF> - --4-it-al i-i---4-h 7 ---L.1 -1 -If

-..t

jT

4><T F -1t I-h ____

- ;1,1- jl t.±-7

{-

T-~~Y_p.

.t1'~ xfbi i-i-It

}r

I Ith JililF Hi-p F-~~ ~~'' ~F-

-_

1V-2

VjK

T-1 -F

21!-i-

7

"i

4111 t 3 -~H

-

.1 - - tWTtT7--: .4 -: I ---.-1. -I- -t 4!:: ILLL.7 414 t f 4 ,

''"i± 'T'

I I I{

~ .-1-T

TI --77 _7,.*<7~~~

J __ 4 -jt1-j

I I' 4t a5.I

-' ~ 7l lipL ~1I 477 77I ---f I 117 iti .* <-j~ ._7

I

1

1>L

7i

1'117

i

V--

LI V

1JI

4S4~Ii-i

-H+ -T_1

2

h-v

I-

I-

17

#w:

-L__ J---41 L Li

The following reactions are typical. "Produces bright and cheerful atmosphere." 'Brings general good feeling between workers and management." "I didn't mind coming back from vacation, because of music." "Music makes time seem to go faster." "Music is essential to

our war effort' says Air Vice-Marshall Sir David Munro. Horace E. Baker, Assistant to Plant Manager of Bristol-Myers sums up music's morale effect as follows: "Music,

in my opinion, is just another intangible asset like a pat on the back from your boss, when you do a good job, or like the cheerful smile with which someone greets you in the morning."

The Reuben H. Donnelley Corp. considers music to be one of the factors which make the better type of employee prefer to work for them rather than for competitors. The other factors are courteous treatment by supervisors, clean orderly rest rooms, immaculate dressing rooms, scientifically planned ventilation and lighting and venetian blinds. Of all the items mentioned as contributing towards improved morale, music is rated last, and would be the first to go if it were ever necessary to eliminate any of these things. This seems reasonable enough.

Granted that the worker's task is more pleasant, do we have sufficient reason to make another investment? How will the union feel about this new idea? Will labor think that this is just another method of management to crack the whip for more production. Let us consider the questions.

20

In return for the general increase in morale, the almost negligible cost is put into the background. Music is known to have attracted more and a better type of worker to plants which experienced excessive labor troubles before music. The explanation is simple. Workers sought a better

place to work.

Music has been heartily endorsed by most labor unions; others have neglected to comment. Probably the most widely known interpretation of labor's attitude was issued by

A. F. of L. President, William Green, when he said, "A

friend of labor for it lightens the task by refreshing the nerves and spirit of the workers." Music is viewed

as another way in which management may provide for the welfare of the employee. Whenever music is installed in

a plant, management is careful to explain that the desire for higher morale is the reason for the decision. However, we can not neglect the fact that an increase in morale will

tend to increase production and reduce costs and labor troubles.

Not always does music divorce itself from labor problems. The abolition of music brought a recent sit-down strike in a cigar factory. Sometimes when music is not played at the regularly scheduled hour, employee com-plaints are quick to follow. Sylvania Electric Products,

Inc. of Danvers, Mass., had one employee remark, "If the music is turned on again, you will have better workers." Poorly reproduced music will be nerve wracking and will

properly reproduced should inspire more will to work and improve morale.

22

FATIGUE

Today's industrial tempo, which features machines and a specialization of labor, has made possible great increases in the speed of the worker. Incentives further augment the cause for greater output and resultant higher pay, but because of improper management or the peculiari-ties of the task the worker experiences excessive and un-necessary fatigue.

Before any study may be made of the effects of music on fatigue, the nature of fatigue must be discussed. In-dustrial fatigue may be classified into three related phenomena:

1.

(1) A physiological change

(2) A feeling of tiredness

(3) A decreased capacity for doing work.

To determine how fatigue could be brought on and combatted it is necessary that each element be carefully explained.

Physiological Fatigue

The first consideration of industrial fatigue re-volves around changes in the physiology of the body. The human body may be thought of as a machine, since fuel and

energy must be stored up before the body will function.

A lactic acid accumulation due to an insufficient

quan-tity of oxygen will produce local fatigue. Fatigue also produces changes in the blood, in the endocrine glands, and in the nervous system, as well as transformations in blood cells and chemistry and variations in pulse and blood pressure. Therefore, if music is going to reduce this phase of fatigue, music must alter the conditions under which fatigue is fostered.

With the use of a Moss dynamo-meter, Dr. J. Tarchanoff found that a person could lift more than usual when spirited music is played; and with melancholy music there is a

de-crease in lifting power'2. Numerous other studies have given rise to many conclusions that may be drawn as to the influence of music on the human body. The work of Tarchan-off and Dutton shows that music increases metabolism. Fere, Tarchanoff, and Scripture indicate that music increases or decreases muscular energy. It accelerates respiration and decreases its regularity, as demonstrated by Binet, Weed, and Giulbaud. A marked but variable effect is also pro-duced on pulse and blood pressure. The researches of

Cannon have shown that Zausic influences the internal secre-tions.3. A good example of music's physiological effect

1. Viteles, M.6., "Industrial Psychology", p. 450.

2. Dardes, Earl, "Music'. How Its strains Inspire Us", Musician, Sept., 1936, p. 136

3. "How Music Affects the Human body," Musician,

24

can be illustrated by the fact that in a six-day bicycle race in Madison Square Garden the average speed under the

influence of music increased from 16 to 17 miles per hour.

As a result of the many physiological ohanges produced

by music, care must be taken in its choice or else the

music will adversely affect the fatigue instead of help-ing to reduce it. Tarchanoff's experiment is a good ex-ample of this.

When music of a lively type is brought to our ears, physio-motor reactions compel muscular tension. This ten-sion of the muscles tries to release itself in bodily acti-vity.' We realize this in the desire to spend our pent-up

energy. When we have followed this urge, a sense of satis-faction and relief is experienced. If when hearing music, you tap your feet or clap your hands, you give evidence of true physio-motor reactions.

Psychological Fatigue

The second aspect of fatigue deals with a feeling of tiredness and boredom. Since it is subjective in nature,

the extent of tiredness cannot be determined. This feeling of fatigue normally acts as a protective device in prevent-ing exhaustion, but often there is little correlation with phsiological fatigue. A person may feel tired and yet he

may work as efficiently as ever, or he may feel normal, and yet he may be actually working at a low rate because of physiological fatigue. Particularly in mental work, the feeling of fatigue may be experienced when the fig-ures of production show no amount of fatigue.

All psychological fatigue results from boredom and

the monotony of repetitive work. As the boredom is in-tensified the worker resorts to day-dreaming and talking with fellow employees, and his production drops off. This

type of day-dreaming usually concerns the unpleasantness of the job and the wish for a better one. It must be pointed out that this day-dreaming is unlike that caused

by the thoughts of pleasant days brought back by the

hear-ing of a familiar song. In the case of intelligent workers the problem is most acute. In every instance management should endeavor to keep the worker's mind on his job. Since this approaches the impossible, a substitute for mind wandering and relaxation of attention to the work

should be provided. Music can fulfill the task of afford-ing a diversion from the monotony of a repetitive cycle, but, at the same time, work in such an unnoticeable manner

that the worker fails to realize the passing of his un-pleasant job in favor of the delightful conditions under which he has the opportunity to be employed.1 . Since any

26

diversion of the eye will tend to affect production, and because music causes reaction upon the part of tne ear and not the eye, the worker's complete physical activity may be devoted to his work.

Decreased Capacity For Doing Work

In addition to physiological and psychological fatigue the industrial psychologist recognizes a third concept; this one deals with the output of the employee. Since the de-creased capacity for doing work results from the effects of physiological and psychological fatigue, the quantity of output is used as the most practical measure of fatigue.

Of course, the manufacturer is concerned only in the changes

in production, and not in the degree of fatigue. If we can accurately judge the causes of the fluctuations in the pro-duction, we shall have progressed a long way towards answer-ing the question, "When can music be used most effectively?"

Fatigue and the Production Curve

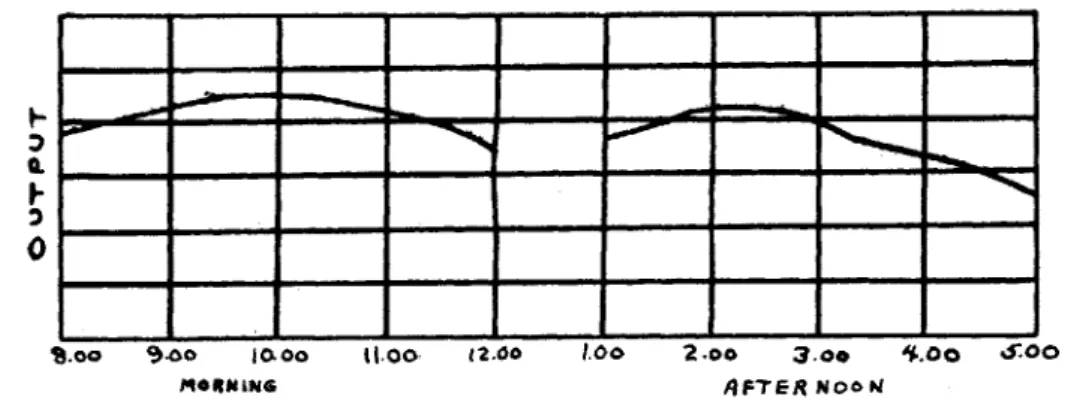

Fig.IM shows a typical production curve for an operation where muscular movement is vital to production. An

auto-1.

matic machine's production should not be affected by fatigue on the part of the attendant. An operation requiring only

slight use of the muscles will have a more smooth curve

than the following, since the physical fatigue will be less.

0

1.oo 9.oo 10o .00 12.60 1.Oo 2.oo 3.0. ' .0o %.00

MORMiNG AFTER NOOW

Fig. m Typical daily production curve for heavy muscular work.

From BarnesR.k.,Motion and Time Study,p. 138.

Our typical production curve has several important charac-teristics which will bear study in order that we may know what are the most opportune times to use music.

When the worker arrives in the morning his production will be low for a short period until he gets back into the rhythm of the operation. In defense of our logic we must say that this initial inertia is due to a lack of practice while any production drop at the end or middle of the work period must be attributed to fatigue. Following the period of "warming up" to the job there is a steady increase in production until a leveling off period occurs. Usually about one hour is required to attain the maximum output period which has a duration of a similar length of time. It is at this point that a steady rate of decrease sets in. Whether this be for the morning or afternoon session, there is no essential difference in the general tendencies.

Slightly less time is required for attaining maximum productiveness in the afternoon, but this is more than

28

offset by the afternoon's faster rate of decline. It can not be emphasized too much that Fig.D= is only a typical curve of production output. In cases where the hours or working conditions are different, our curve will not necessarily hold true. On piece-work operations not infrequently does the production increase just before a rest period or the end of the day. Maybe the worker sud-denly realizes the lag in production and puts on a last spurt. Only from experiment can the production curve of the individual company, and sometimes even the department, be ascertained. Only in this manner may the best times to use music for the relieving of fatigue be determined.

As the production curve is studied, the theoretical times to use music become rather clear. When the workers first come on the job, peppy or martial music should go a long way towards eliminating the initial inertia. Since our production has now supposedly reached its peak level at a quicker rate, care must be taken that the decline in production does not set in sooner than usual. To handle this situation music is played at the pre-fatigue period just before the production begins to drop. By the process of experimentation the number of times that a musical

series of lifts need be given can be obtained. In a later section the actual times and types of music that have

Besides causing a decline in the over-all fatigue, music can produce a stimulation. A displacement of

fatigue, such as is the effect of coffee, is the evidence of stimulation. Although the worker may be psychologically influenced to work harder, his physical body may not be changed by music. He is, therefore, confronted with a temporary lift which will hold him until he gets home. However, there seems to be little of this effect. If we can believe what workers say (we have no other choice

here, since no tests have been made), the fatigue reduc-tion of music while at the factory is not a mere displace-ment of fatigue, since workers claim a permanently less

tired feeling and more joyful spirit than before music was used in their plants.

Noise

Noise is credited with doing a lot of harm to em-ployee efficiency by causing greater fatigue. It is hardly expected that noise in a steel mill can be elim-inated, but there is no need to augment the noise and consequent inefficiency and fatigue by the use of poor reproduction facilities. Many companies have found from sad experience that music which blares and screeches is more of a liability than an asset. Not only does it actually increase fatigue, but it is a source of

30

irritation which may anger the employee. It is therefore of utmost importance that the music be clear and distinct if an efficient organization is to be maintained and labor trouble to be avoided.

PRODUCTION

How Morale and Fatigue Influence Cost

The manufacturer is guided in almost all of his deci-sions by the one primary purpose of turning out a greater amount of goods at a lower total cost. In other words, he is trying to (1) produce more goods with his present

facilities, (2) cut down the costs below his present costs. The ability of music to influence morale and fatigue

--and perhaps to have a rhythmic effect--has been demonstrated. Now, how can these effects of music help the industrialist out his unit cost?

It has been explained how the industrial psychologist has shown that as mental and physiological fatigue increases, the individual's production rate decreases. In fact, the production rate is used as a convenient way of measuring the degree of fatigue. So we will argue no further the point that lower fatigue means higher production.

How can better morale cut the unit product cost? In the first place, it is fairly obvious that the worker who

is happy can produce faster; that the worker who is on friendly terms with his employers vill not hold himself back, either purposely or subconsciously. Most employers claim that they use music to aid morale, and they are undoubtedly sincere in this statement. But when we look

at the situation realistically, it is clear that their subconscious, indirect purpose is to aid production and cut costs by means of a higher degree of morale. Not only can better morale increase output, but it can also decrease the cost of operations, since (1) less supervisory and administrative work will be necessary with content workers, (2) it has been demonstrated (by Houser, e. g.) that

high morale results in less demands for increased wages.

In the present section, we will not consider the lower total cost aspect further. Music's effect here is

indirect, and has never been measured. So music's effect on production will be discussed from now on. No attempt will be made to differentiate between production increases resulting from lower fatigue, stimulation, rhythmic effects, or morale; rather, the over-all effects on production will be investigated. Actual controlled tests of music's

ability along this line will be cited.

How Music Saves Time

Though the increase in production rate is the main contribution of music to higher daily production, there is another way in which it is effective in achieving this latter objective. We refer to the ability of music to keep the worker on the job for the full daily work period.

Mr. John C. Chevalier, general manager of the Palace

Laundry in Washington, D. C., describes their experience, "We found that the get-together in the morning in the var-ious departments was slowing and that there was lost motion in production starting time, so a morning program of

marches, etc. was inaugurated, and this had a satisfactory effect." Workers often find various pretexts to cease work, so as to talk with neighbors, watch visitors, etc. Music has been found to cut down this non-productive time.

Obtaining Reliable Data

Before discussing the actual production results which have been obtained with music, let us consider some of the difficulties which are faced in measuring these output changes. This will make it clear why no figures on this

subject are perfectly reliable, and why any figures obtained

by any means other than scientifically controlled

exper-iments are particularly open to suspicion. We do not mean to imply that such figures do not prove what they pretend to prove, but rather that it must be borne in mind that they may possibly be erroneous, quantitatively at least.

In making comparisons between production rates with and without music, it is necessary to hold constant a large number of factors which might influence the

produc-34

tion rate, either upward or downward, and make the apparent results false. Most comparisons fail in this respect,

allowing some of these causative factors to vary. A change in the group of workers being tested is a good

example. If a new worker took the place of an experienced worker, and music were tried shortly thereafter, the pro-duction rate figures with music would be misleadingly low, .relative to the non-music figures obtained while the

exper-ienced worker was on the job. Other variable conditions would be: pay rate, light, temperature, humidity,

venti-lation, noise, weather, quality of materials, number of machine breakdowns, etc. Also, obviously, changes in

pro-cess, product and machinery would invalidate results.

Employer-employee difficulties would cause erratic ouiGput.

Another factor to bear in mind is that if music is taken away from workers who are used to it, there may be much more of a drop in.production at first than can be

expected after the shock of their loss has worn off. Like-wise, when music is played to workers for the first time, the pleasant surprise may produce temporary results

greater than will be obtained in the long run. Therefore, test periods must be of sufficient duration. But the

longer the test period, the greater the changes in variable conditions. A dilemma is faced.

If the subjects of the experiment realize that a test is being made, and if they are told that music is expected to increase their output they may subconsciously drive themselves to greater efforts while the music is being

played. Morale: disguise the experiment as somethIng else.

The experimenuir is clvarly faced by a numour of

difficulties, and error in his results is almost something to be expected. Errors are, therefore, not to his dis-credit if he makes a reasonable attempt to conduct a signi-ficant test. He has the further problem of choosing a unit of measurement of production. In a shipyard, for example, this is almost impossible. In cases such as this, pure opinion has had to be resorted to in judging relative pro-duction rates. Too often, however, this type of guesswork is used to avoid the trouble of making a serious test. Wherever someone's opinion as to production changes is

given, it must be treated as such, and its degree of relia-bility borne in mind.

-~nI

-36

Daily Production Curves

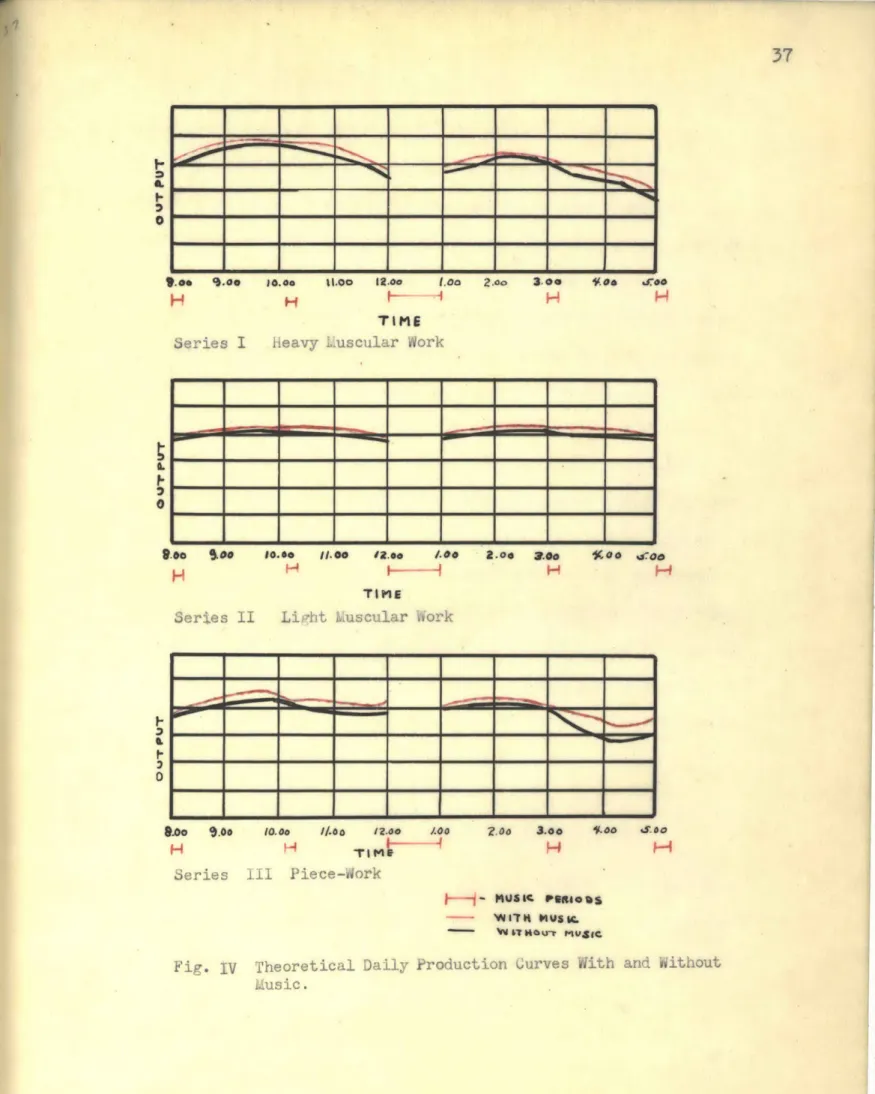

The manner in which fatigue affects the daily pro-duction curve has been explained. The way in which

music affects the curve must now be discussed. Figure IV shows a series of daily production curves. Series I is the curve of a worker doing work requiring considerable muscular effort and being paid by time.1 Series II is

that of a worker performing an operation where less effort is necessary, pay still being by time. It is flatter than the first one. Series III shows how a worker produces when he is on piece work. Toward the end of the morning and of the afternoon he puts on a last spurt of speed, and his curve acts accordingly.2 It must be emphasized

that these curves are theoretical curves only. Seldom do workers have smooth curves; usually they are quite jagged; but when the fluctuations are smoothed out the resultant curves are like those shown.

The placing and duration of music periods follow no standard model. This aspect of the problem will be con-sidered later in this report. One of the most common schedules, for an 8:00 to 5:00 day with no rest periods

1. Barnes, Ralph M., "Motion and Time Study", p. 138

2. Anderson, A. G., "A Study of Human Fatigue in Industry", an abstract of a thesis, pp. 20-22, University of

Illinois, 1931.

H I,.,. H 11.00 . H TIME

Series I Heavy Luscular Work

- m - - - -

-- - - - -t.#@ ~Le. H H T-M TIME /#ee 1.00 Ise. -i HS3eries II Li-ht Luscular Work

IO.Oe JI.Oo /2.00 A06

H sTIM

Z.0 . ..o"

1-4

Series iIl Piece-Work

k-I-

9MUs PgBolas-- wt" Owsm.

nV 4Gu-r mIPag(.

Fig. IV Theoretical Daily Production Curves With and Without

uUsic. a, H 0 'KO, iiCOG H 0 9.o0 9.0. H J eo H mmmmmommmm" mmmmmmmmmv 3-0* mve 00 X" .00 2.00

38

except noon hour, supplies music thus: 8:00 to 8:15; 10:45 to 11:10; lunch period; 3:20 to 3:45; 5:00 to 5:15

(this latter period covers the start of the next shift, and the clock punching of the first shift). These periods of music give the worker a "lift", much the same way a

short nap would, and act accordingly on production. When the music schedule mentioned is used, the result is shown approximately by the red curve in each series. Of course, the reaction of every worker is not the same, but this represents a typical one. Note the quicker pick-up in the morning and the slowing of the downward trend in late morning and afternoon. The objective, of course, is to make the area under the final production curve as great as possible. The playing of music at any given time will result in a spurt of output at that time; but the placing of these music periods during the fatigue periods adds more area under the production curve than as if they were placed at the high point of the curve.

Possibili. y of No Effect on Production

Under certain conditions, music may not increase the

production of the worker--even assuming accurate measure-ment. There are four possible reasons for this (the first

three will be taken up in detail later): (1) poor music

system or program, i.e., reproduction, time, or type of music; (2) work of such a type that no increase is

pos-applied to workers for whom it is not adapted, e.g., those who must mentally concentrate on their work;

(4) work artificially held down by the workers. This last situation may be caused by workerst fear that a piece rate will be changed, or it may be the result of poor labor relations, wherein the employees are purposely slowing down. If the workers believe that the music is being introduced to cause them to work faster, they may

take this latter course.

In none of these cases can industrial music be blamed for its failure. Proper study of the situation, proper choice of method, and good labor relations come first. There is still the likelihood that the music will aid morale, just the same.

Scientific Experiments on the Effect of Music on Production Rate

Having discussed several theoretical aspects of the effect of music on production, let us investigate the actual scientific, controlled experiments that have been made to discover the influence which music has on produc-tion rate.

Only the results of tests dctually made in the factory, rather than in the laboratory, can be taken as conclusive proof of music's effect on the worker.

40

We know of only two such series of experiments that can be classified as truly scientific. In other words, the experimenters have seriously attempted to control the various variable factors previously mentioned, and have taken other precautions to make the results valid. Because of their importance, these two experiments will be discussed in some detail. The first of these was performed in 1937 in Great Britain by S. Wyatt and J. N. Langdon of the Industrial Health Research Board. It is reported as a section of "Fatigue and Boredom in Repeti-tive Work", Report #77.1 The second series of experiments were performed in 1942 by Professor Harold Burris-Meyer of Stevens Institute of Technology under a Rockefeller Foundation grant. He was assisted by Mr. R. L. Cardinell. Though a final report of their investigations has not

yet been made, enough has now been announced to show that it is a comprehensive study.2

It must be borne in mind that what is found true for one type of worker in one type of industry is not necessarily true for another type of worker or another type of industry. In the British study, the subjects

l. Wyatt and Langdon, "Fatigue and Boredom in Repetitive Work", pp. 30-42.

2. Harold, Burris-Meyer, "Music in Industry", an address before the A. S. M. E, October 15, 1942.

were 68 girls, aged 14 to 35. Twelve were selected for intensive study. They were engaged in making crackers

(party favors which explode when you pull them apart), a repetitive operation. They were paid by piece-work and were working on the day shift.

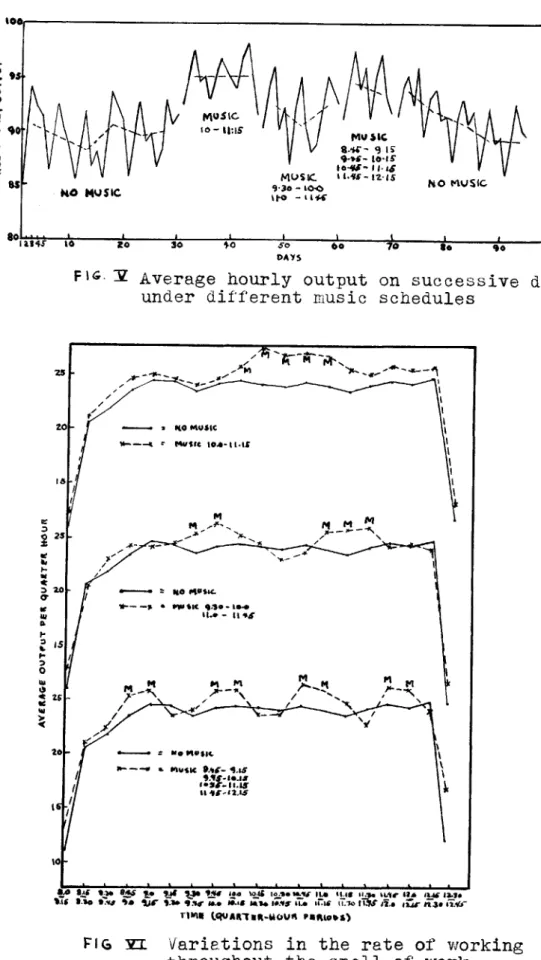

Music was played to the workers between one and two hours a day. For the first six weeks, there was no music, but production records were kept. For the next three weeks, music was played on a certain schedule; for another three weeks, on a slightly different schedule; and for two more weeks, on a third schedule. Then for five weeks, music was not played. Each of these groups of from two to six weeks is known as a "period".

Two parts of this investigation are significant from the production point-of-view: (1) music's effect on

the average hourly output over a long period, (2) variations in output within the daily spell of work. Figure V is a graph of the average hourly output during

the experiment. The average hourly output with music is clearly higher than that without music. When music was discontinued, the average hourly output did not immediately fall back to the old level, but rather tthe decrease was gradual and suggested a progressive change in attitude towards the changed conditions of work". Hence the

'51 -..-- - . -- 4 JlI-9-14- S1-15 1.4- 1 .i musi ".4s- 2 s s is -iIc* ** g94 , 0 DAYS

F 1 Average hourly output on successive day under different music schedules

&01 9.20 *wu "S* 'AI !L46 "a9 Me 4 !-.a 1 *.20. 11A. e i-s 41Th 1 3 At a 4

rTMiQ (.qUARTaR-Moult 'antows)

FIG vI Variations in the rate of working throughout the spell of work

IV I 42 1-0 Xj dc s 23 a * 20 I-0 20 t6 to -O MUSIC --- k M Sfe jo.$-tj.j$ IM IL 01e'.9t 'II -i

average hourly output during this period should not be compared with the average hourly output during the rausic periods. The A. H. 0. (average hourly output) during the period before music was installed can, however, be safely compared with the A. h. 0. during each of the three different music periods. The A. H. 0. under each type of music schedule was different. The

A. H. 0. for each of these periods was compared with

the A. H. 0. before music was installed. The results found were:

The average increase over the original, non-music period was 6.Oo for the first non-music period.

The increase was 2.6yo during the second music period.

The increase was 4.4a during the third music period.

These results are statistically significant. They really prove that the introduction of music does increase Droduction, for these particular workers on this particular operation. The efIect of the music may not have been precisely that indicated by tlLe

figures, but the qualitative effect of the music is undeniable.

The second significant result of this investigation is the findings concerning variations in output within the spell of work. Figure VI shows this graphically.

44

no-music day. This was a composite of the daily pro-duction curves of each of the days in the original

period before music was tried. Then a similar composite curve was obtained for each of the three music periods. Each of these three curves represented a typical, average

production curve for a day in that period. These curves of the three typical musical days were superimposed on the curve of the typical no-music day. It is obvious at a glance that the music had a definite effect on the production. A. H. 0. climbs rapidly when the music is

turned on in every case, and drops when it is turned off. The increase in output during the minutes while the music is actually being played over the output during these

same minutes on a no-music day was calculated. The lowest increase during any music period (where we are now using "music period" to mean the thirty or forty-five minutes during which music is played) was found to be 6.2%; the highest increase, 11.3%.

We must keep in mind that these figures indicate just one thing: that while the music was actually being played there were production increases of 6.2 to 11.3%. We must beware lest we jump to the conclusion that music

can give us production increases of 6.2 to 11.3% per day. While the music was off, the production curve

dropped. It is the total gain for the day that really counts. And the gain for the day was considerably less

than 6.2 or 11.3%. In fact, if we assume their figures to be accurate, the daily gain was precisely 6.0%,

2.6%, or 4.4%, depending on the type of music schedule.

These latter figures are the really significant and important ones in this experiment. Probably the first thought that would come to mind would be that by playing music all day long the 6.2 to 11.3% increase could be

realized for the whole day. But for reasons which will be explained later, one to two hours per day is about

all the music that can safely be played. So our 6.2 to

11.3% figures help strengthen our theory as to the effects

of music on production rate, but they prove nothing as

regards the quantity of over-all gain that may be obtained.

The second series of significant experiments were those carried out by Professor Burris-Meyer of Stevens. His results are particularly valuable in that he worked with a number of different types of workers, in a number of different industries. Though complete data on his experimental set-ups is not yet public,1 the results are available.2 Five of his tests are important from the production point-of-view.

The results of the first test, as shown in Figure VII,

1. A complete report is scheduled to appear in Jan., 1943. 2. Op. cit., Burris-Meyer.

:HI E 171 -LLIL I T] I +4 f-ii-- I I IV 4T-FT I--I-H+H-H 11±1 +111 +HI±H+I+H±I-H-H4+ T tl -i- 1, 1-i -1 i11 7- F1 -L A- * j -+ I TIT + I + I flk .1 .14-1--h-14H i- - - I - LIT T- t- THt E I -A[I I f -UTTI-IT 411 ur -T-r 41- T q- ++ +F + T- -- 41 t # f+l 7 -TI I r T -tPE +T T T-rf L -- T HA- L + 1 4- - 44 44 44-4 FLF ii . -, I_ TIT, M ill -.:I, 4-4 1 -- l- Tll -RJT F F -lip T T-T- T- Tf 47 -1 it + I I I I T -p- 4 -T- -4- 4 1 17 Tl- TF -1T--T --i --T -I--- -- T tT l ll -1 -r- T T T! -T- M 4 -4,1+ 4-41 -14- -!- T- J- T t-1 t 711 -T-T-,--T r"T t T- 4:14- T I T -1+1 T- IT -t -I-T- LL --.- -1 -I -T- i, -;, " 7 1-1 T TIF, iT- A-1 L! -I . i J- T i 4 4- -T 11 --H" I 4 r I J-: -T-T - T: , -- -! -1, i+ T Ti, F7T -T -;J, + Orr -44- = 1 -:7 i I-tj t IT T.Fi L T T --i -, 1- -T- : -T 1 Y4 --T 17 A-1 al-j-AT -4- -t 1 7" j IT 7 -T -1-1 V LJ T-; A tit- I -t 'T-T T 4 , 14 I-T T-JA + -4, TP4 1-T r- Au -T T-' ijTPI t-1 T, ie- O t T T7 -7 T H -HIT l . . -1 14 1 f It T -474 LT I T7 T T t T TT I ,

T

- .-, -4- T- 1, : T, - - -T I T- - t I- I- I IT :TILF fl Pi Lai -T -"T 7f7 T I T L i7 7 T + T4 --4 -i , [ ---[ -, -- i , . . .7 . . --1 . T T- -lll f r --4 7 T T j-, t-t 1- -T -T t T Tl : -j -L- T I r t T + LT -T-T --T J: T il H i 4P, I . 1 1 f , , . ; L ---- . i " j I i T T T -- I -', i- - - -1 -1 7 A'Al H t F T+ +r f i I T _, _ - 1- -, 7! -T- j+ + T I I T , i -f I H + t LL-LT -- T T I T j t -T- T- H ±77 i ! i 11 L H t2t!H 1-1 -1-show the unit output rate (average of the group tested, of course) of an individual on an afternoon when music was played superimposed on the output rate of an after-noon without music. Though both curves are very erratic, the output curve of the afternoon with music is clearly the higher. The average output for the entire afternoon, in units per employee per quarter-hour, is:

Without music, 46.5 units With music, 49.6 units

Music has raised the afternoon's total production 6.25%.

The results of the second test (Figure VIII) show the output per 100 man-hours on each day of a typical five day week with music, this curve being superimposed on that of a typical week without music. Again it is clear that output with music is far above that without it. The average production for the whole week, in output per 100 man-hours, is:

Without music, 301.2 With music, 335.6

11.4% more units were turned out during the music week than during the no-music week.

The third test (Figure IX) shows how weekly output changes when music is installed. Average production per

100 man-hours was calculated for an entire week without

I I-I ii j Iii:] iiyL.LI.zl-i-.tk 1-H-I-1-H-11 -I±{-- 111H± 1+H-4-I .:t--ri itI 1-4L4 ~ L {2'~ L ' P~~~ -TIT- -1 - ifi T fil v T

-t-f_ 44+7

-- --- -- I: T L I -1 { 7 f41- TT'IVrT_- -~ -i - 4----I~~~ r4T T2

b 71 4 -1p t -r -v-Vt r l t Ih ~ 4 -t It T47 7- 7- -7- 1"T F4 -F _ f -I-11- -if11 T_ T~ 2. 4.4- j4 i i-,iJVT

It'

j-r TIfI

K-+1i 5w''I7~I

V-t

f41+1

.4'' Yr-i rr, -I-

t<-'

LvI

-~~hL~2 i

T , T H --Vml

HHHHHH.11.1111 IIII

;-j I d-' JLT F T J;---I f- 44 __; _ _E

It

TIT

_i7K~ltuzim

7n

4

tt

1<

I tb1

diTli 7-7 H7-m

4 j L t itnIi_

Ftj-

4 ~ TP

L -{ M T1 I tt VI I I L It i4 j -i F: -t _-+ 1T I

-Li-jA$

I

_L I A 1- 411 Ah tWNP I- 1-tIYP'Vf4 tv-I 111111111111tt H+ +HTH++44 t+ M I I , rr-I -17---f++ 11 1 1 _1111 I-_-F50

weeks, music being played during these eight weeks. In only one of these eight weeks was production lower than during the no-music week; it was considerably higher in the other seven. The production decline during the third week is undoubtedly attributable to some subtle variation in one of the conditions of work, the experimenters being unaware of the change. Because of the fact that data was obtained for only one week without music, and since it is fairly obvious that this test was of such duration that all variable conditions of work were not held constant, it should probably be given less weight than the others in the series.

The fourth test (Figure X) is very similar to the third test. The experiment was performed in another fac-tory, however. It is of greater significance than test

#3 in that the production rate without music was observed

for three weeks. Furthermore, the music was tested for only three weeks, thus giving the variables less chance to change drastically. The average output per man hour was:

Before music, 270 After music, 281

The output was 4.07% higher while the music was used.

The results of the last test concerning output are illustrated in Figures XI and XII. The dotted curve of

-, __ r I 1 41

LI

5 1t

1

-r

4k I 4 22 #-i 44f 4- i 77 b -IVA L V -4 i TT; -7 r -- - - -- ' - ._7_-h _- - r.- J-- tl I+HI

Ti: T' III _____4 I_ I_ IF I 1 ~ ~ r11: tH _ +HHHH HHHF V4- i i i i i i i " FPP 11111111 :t]IU i--4-- 4T i-i-I; -- L 7 ( I - 7--4, 7 7-1- P 7 47, 27 4 r~~ ~ ~ ~

>7

+- I II I1 7 I~~ I t I 1 1-T -iT-A-i-i-.1 J-1-_ -t~

-T-- -H T

--1-4-4

---It; 't' 4 ~t 47 'it 1tt41411 FtTIlIi4iLtUA I 2t1124t41 4z! It 44P" 4Tt L- 1- rum-4224 ~ ~ L j17n-Ff4-1: i4144714r7i414T i17' 7 I III -II P -, I , I I I

-I -] . I . I . I I.! -A 17 7 I I I I :11 , 'jtTi_ 7 -1 [ L T 7 1 4+ -H-i -T-1 + 1 14- j_++ LIttA~±t4 4 [1, 1 1 . : T : I-21 1LU4 ~4K4 --hi I-hI MItIl1 11j1tv 1-2 FT~hFm ~ 47 711., 1 1 1 -H TT F-1

-<22 W41 I-Fi i A t III "-- -- T _Hn -I-t1t

Ii f

hkiIf

-t-j'-

t-T

Mlt -7-1J--1

71-T3717

1 1 .... I' I I -I- I,,,- I ' .1-171 44 [_I I-4=,

1-7iI-Trri

t _: 4-t+--j T 17 -1Y7 2 I'ThtTh

t Ml~t~4 IL ?"TIr-I ' I I T I I I I I I I I I I I I I~-1~ ~

5.4

Figure XI shows the afternoon production curve of a typical individual in a certain factory before music was installed. The solid curve shows what happened when music was added. When a slightly different music schedule was tried in

the same factory an even higher production curve resulted. This is shown in Figure XII. The average for either of the curves obtained with music is higher than the average before music. The efficiency of the worker for the after-noon averaged:

Without music . . 72%

Music schedule shown in Figure XI . . 80% Music schedule shown in Figure XII . . 86.80

Under the first music schedule output is 11.1% (of the no-music output) higher than it is without music; under the second schedule, 20.6, higher.

Professor Burris-Meyer makes one other statement which carries considerable import, though he has not yet offered figures to substantiate it. In referring to tests

such as his first one he says, "In more than 75% of the measurements of this sort in all the factories studied, we have found the area under the curve, or total produc-tion, to be greater when music was used than when it was not used."1

From a study of the experiments of the British

Industrial Health Research Board and of Professor Burris-Meyer, there can be no denying the fact that music can

be utilized to increase the productivity of the worker.

It must be emphasized again that findings in one indus-try are not necessarily transferable to another. But the types of workers which have now been studied are varied enough, and the findings are general enough so that there is every reason to believe that music could be profitably used in a large percentage of the

manu-facturing establishments of this country.

The Ogeradio Experiment

The two series of experiments which have just been discussed are the only truly scientific studies of which we know. There is, however, one other experiment which appears to have been carried out under fairly well con-trolled conditions, and which should, therefore, give reliable results. The work has been carried on on pro-duction line of the Operadio Manufacturing Company of St. Charles, Illinois, and tests are still continuing

at this time. The music was introduced gradually, so there would be no question of "forcing" production, and so the music would not be too much of a surprise to the workers. Let us quote from a letter received from Mr. F. D. Wilson