HAL Id: halshs-01100137

https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01100137

Submitted on 6 Jan 2015HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

ENCLITIC IN PUREPECHA: VARIATION AND SLIT

LOCALIZATION

Claudine Chamoreau

To cite this version:

Claudine Chamoreau. ENCLITIC IN PUREPECHA: VARIATION AND SLIT LOCALIZATION. J.L. Léonard & A. Kihm (eds). Patterns in Meso-American Morphology, Michel Houdiard Editeurs, pp.119-143, 2014, 978-2-35692-120-8. �halshs-01100137�

Chamoreau, C. 2014. Enclitics in Purepecha: Variation and split localization. J.L. Léonard & A. Kihm (eds). Patterns in Meso-American Morphology. Paris: Michel Houdiard éditeur. 119-143.

ENCLITIC IN PUREPECHA: VARIATION AND SLIT LOCALIZATION

Claudine Chamoreau

CNRS (SEDYL/CELIA)

1. INTRODUCTION

A clitic is generally defined as a grammatical word that lacks independent stress and must attach itself to another element, called the host. It is not restricted to any particular host but chooses a specialized position. The second position or Wackernagel position is the most common: that is, the clitic appears after the first constituent of a clause. This is a fixed position, but a clitic may also have a floating position when it is positioned close to the constituent it modifies (Aikhenvald 2003, Anderson 1993, Bickel and Nichols 2007, Dixon 2004, Siewierska 2004, Zwicky 1985, Zwicky and Pullum 1983). A clitic may possess different orientations, either preceding (proclitic) or following (enclitic) its host.

The aim of this paper is to categorize the clitics of Purepecha. This language possesses only enclitics and combines different types – fixed and floating, pronominal and non-pronominal. Pronominal enclitics are illustrated by example (1) and discursive non-pronominal enclitics by example (2). Both are fixed second-position enclitics; by contrast, adverbial non-pronominal enclitics have a floating position, as in example (3).1

(1) ka=kxï ikya-pa-rini wanto-nts-kwarhe-pa-ntha-ni and=1PL get.angry-CENTRIF-PART.PA tell-IT-MID-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF

xa-rha-x-p-ka

be.there-FT-AOR-PAST-ASS1/2

‘…and, getting angry, we discussed.’ (IH10: 128)2

(2) no=chk’a=ni xwina-x-ka ugo-ni jupi-ka-ni juchi kawayu-ni

NEG=certainly=1 allow-AOR-ASS1/2 Hugo-OBJ take-FT-NF POS1 horse-OBJ

‘I do not allow Hugo to take my horse.’ (JR10: 2)

(3) ajta jiniani ire-ka-s-ti, chari tata jingoni=t’u, as far as there live-FT-AOR-ASS3 POS2PL father COM=too

primu-e-s-ti ima=t’u cousin-PRED-AOR-ASS3 DEM=too

‘He lived up there, with your father too, he is also a cousin.’ (AR1: 10)

1 This research was made possible through financial support from the French Center for American Indigenous Language Studies, CELIA (CNRS-INALCO-IRD), the French Center for the Structure and Dynamics of Languages, SEDYL (CNRS-INALCO-IRD), the French Center for Mexican and Central American Studies, CEMCA (CNRS-MAEE), and the National Institute for Indigenous Languages of Mexico (INALI). Aid from these institutions is greatly appreciated. This research would not have been possible without the support of Teresa Ascencio Domínguez, Puki Lucas Hernández, Celia Tapia, and all our Purepecha hosts. Part of this investigation has been conducted in cooperation with F. Villavicencio (Chamoreau and Villavicencio in press). 2

The examples of Purepecha come from my own fieldwork data. The first letters correspond to the pueblo, here IH; then there appears the file identifier, here 10, and finally the reference of the recording, here 128.

In the sixteenth century, these positions were obligatory: pronominal and discursive non-pronominal enclitics had a fixed position and adverbial non-non-pronominal enclitics a floating position. Today, the fixed position shows some signs of weakening. Non-pronominal enclitics keep their position, while pronominal enclitics show variation, tending to move to the right position in the clause, and may encliticize to the predicate itself or to the last constituent before the predicate. This enclitic is called the predicate enclitic, as illustrated by example (4). Pronominal agreement is also frequently found: that is, an enclitic and a pronoun (or a noun) referring to the same argument are allowed to occur together in the same clause, as illustrated by example (5).

(4) peru noampe exe-x-ka=ni but nothing see-AOR-ASS1/2=1 ‘... but I saw nothing.’ (UR2: 28)

(5) pawani=kxïni jucha ma kantela íntsï-mpi-a-ka=kxï

tomorrow=2PL.OBJ 1PL.IND a candle give-ASSOC-FUT-ASS1/2=1PL

‘Tomorrow, we will offer you a candle.’ (JR2: 24) Today, Purepecha has three types of enclitics:

Table 1. The three types of enclitics in Purepecha

Host Enclitics

Type 1 second position non-pronominal pronominal Type 2 end of the element or end of NP that

contains the element modified by the enclitic

non-pronominal Type 3 predicate (head) of the clause. pronominal

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces some basic typological properties of Purepecha; section 3 describes second-position fixed enclitics; section 4 deals with floating enclitics; section 5 shows the recent development of the new predicate enclitic. The discussion in section 6 looks at current tendencies and variations in Purepecha, highlighting diachronic and contact-induced change explanations.

2. BASIC TYPOLOGICAL PROPERTIES IN PUREPECHA

Purepecha (formerly known as Tarascan) is classified as a language isolate, and is spoken in the state of Michoacán by approximately 110,000 people (Chamoreau 2009, 2012a, 2012b). The classification of Purepecha as a Meso-American language is still debated, but generally it is not classified as a Meso-American language (Campbell et al. 1986, Smith 1994).

Purepecha is an agglutinative and synthetic language, and is almost exclusively suffixing. It has an elaborate derivational verbal system. Although bare stems exist, there is a very productive derivational system in which a basic stem can take voice, causative, locative, positional, directional, and adverbial derivative suffixes. Inflectional suffixes follow the stem to mark aspect, tense, mood, and person (Chamoreau 2009).

Purepecha has nominative-accusative alignment, and is a case-marking language in which the nominal subject has no overt marker. The object is generally marked by the objective case marker -ni. This morpheme encodes the object of a transitive verb, such as misitu-ni ‘the cat,’ in (6), and both objects of a ditransitive verb, such as inte-ni wantantskwa-ni and Puki-ni, in (7). The object is generally marked by the objective case marker -ni. This morpheme encodes

the object of a transitive verb, and both objects of a ditransitive verb. The presence or absence of the object case marker depends on different hierarchies: (i) the inherent semantic properties of the referent (human, animate); (ii) properties related to grammatical features (definite, count noun vs. mass noun, generic vs. specific, etc.); and (iii) pragmatic strategies (topic, focus) (Chamoreau 2009).

(6) xo Selia ata-x-ti imeri misitu-ni yes Celia beat-AOR-ASS3 POS3 cat-OBJ

‘Yes, Celia beat her cat.’ (JR-A25: 94)

(7) Selia arhi-x-ti inte-ni wantantskwa-ni Puki-ni Celia tell-AOR-ASS3 DEM-OBJ story-OBJ Puki-OBJ

‘Celia told Puki a story.’ (JR-A25: 36)

Subject and object pronouns are expressed by second-position enclitics. Purepecha displays predominance of dependent-marking, for example the pronominal enclitic, as in (1) and (2), and the genitive case, as illustrated in (8).

(8) jinte-s-ti wámpa Maria-eri be-AOR-ASS3 husband María-GEN

‘He is Maria’s husband.’ (JR7: 90)

Purepecha is basically a SV and SVO constituent order language, as illustrated by examples (6) and (7). This order, that is, the one that is pragmatically unmarked, is the basic order in the region of Lake Patzcuaro (Capistrán 2002, Chamoreau 2009: 55-58, 2012c). Other orders indicate specific pragmatic properties. Studies of constituent order in the other regions do not as yet exist (Chamoreau 2009). However, Purepecha exhibits some traits of a SOV language: (i) tense, aspect, and modal markers following the verb; (ii) postpositions; (iii) only suffixes; (iv) only enclitics; (v) case markers; and (vi) main verbs preceding inflected auxiliaries. SVO and SOV constituent orders are attested in the sixteenth century, and the former has gradually increased since then. The change is probably due to areal contact. Spanish has been the principal contact language for many centuries; however, prior to the Conquest there were speakers of other languages in this territory, mostly from Nahuatl (Uto-Aztecan family) and Otomi (Otopamean family), two languages with verb-initial structure. The change probably began under the influence of these languages; Spanish, a SVO language, continued the process, for example by introducing prepositions (Chamoreau 2007).

Purepecha has accented independent pronouns (see the paradigm in table 2). In the singular, subject pronouns are the simple form, and in the plural, the plural marker -cha is suffixed to the singular form. Nevertheless, pronouns are considered as lexicalized forms. Object pronouns are complex entities constituted by three elements now considered to be lexicalized, that is, subject pronoun plus objective case marker and objective pronominal enclitic (see table 3): for example, in the case of the second person, t’u-ni=kini. They are used to introduce and to emphasize a referent, as illustrated in example (9).

Table 2. Independent pronouns

Subject Object

1 ji jintini

2 t’u t’unkini

2PL t’ucha / cha chankxïni

(9) jucha isï=sï mi-te-s-p-ka ima tshirakwa jimpo 1PL.IND thus=FOC know-face-AOR-PAST-ASS1/2 ART.DEF cold INST

‘We, thus, knew it for the cold.’ (TM9: 10-14)

Purepecha has three exophoric demonstrative pronouns (i, inte, ima in the singular and tsï, tsïmi, tsïma (imaecha / imaksï), in the plural). The distal invisible demonstrative pronouns, ima and tsïma (imaecha / imaksï), have been recruited for the use of the anaphoric (endophoric) pronoun.

3. SECOND-POSITION ENCLITICS

3.1. PRONOMINAL AND DISCURSIVE NON-PRONOMINAL ENCLITICS 3.1.1. Pronominal enclitics

For pronominal and discursive non-pronominal enclitics, the second position is the unmarked and more frequent position. Enclitics do not depend on the grammatical class of their host. The pronominal enclitic is used to indicate the referent’s functioning either as the subject of a clause, as illustrated by =ksï in (10) in an independent clause, or as the object of a clause, as illustrated by =kini in (11) in a dependent clause, whatever the valency of the verb (Chamoreau 2009).

(10) no=taru=ksï ima-echa-ni jatsi-a-s-ka

NEG=other=1PL DEM-PL-OBJ have-3PL.OBJ-AOR-ASS1/2

‘We no more had them (papers).’ (AR1: 43)

(11) xu jano-s-ti [eki=kini juchi watsi jwa-kurhi-ka] here arrive-AOR-ASS3 when=2OBJ POS1 son bring-REF-SUBJ

‘He arrived here when my son brought you ...’ (AR2: 102)

In table 3, we may observe the two paradigms of pronominal enclitics, namely the subject and object enclitics. Subject enclitics are simple forms whereas object enclitics are complex forms composed of a simple form and the objective case –ni.

Table 3. Pronominal enclitics in Purepecha

Subject Object

1 ø / =ni =reni(=rini) / =ts’ïni3 2 =re (=ri) =kini / =kxïni4

3 ø Ø

1PL =ch’e (=ch’i) / =kxï5 =ts’ïni

2PL =ts’ï =kxïni

3PL =kxï =kxïni

3 =ts’ïni is used when the subject is plural. 4 =kxïni is used when the subject is plural.

5 The difference between =ch’e and =kxï (or =ksï) today shows a dialect variation (Chamoreau 2009: 64) that reveals a diachronic change: in the sixteenth century only =kuch’e (the marker that has been grammaticalized in ch’e) was used. The second marker, =kxï, seems to come from the third person plural.

(13) a. kara-sïn-ka / kara-sïn-ka=ni write-HAB-ASS1/2=1

‘I write ...’ (JR4: 257) b. kara-sïn-ka=ri

write-HAB-ASS1/2=2

‘You (sg.) write ...’ (JR4: 260) c. kara-sïn-ka=ksï

write-HAB-ASS1/2=1PL

‘We write ...’ (IH45: 67) d. kara-sïn-ka=ts´ï

write-HAB-ASS1/2=2PL

‘You (pl.) write ...’ (IH3: 861) 3.1.2. Discursive non-pronominal enclitics

Only four non-pronominal enclitics appear in the second position, as shown in table 4. They have a discursive meaning, as illustrated by the focus =xï in (14) or the certainty marker =chk’a in (15).

Table 4. Second-position non-pronominal enclitics in Purepecha =sï / =xï focus

=xaru probability =chk’a certainly, well =na / =nha Evidential

(14) tsïma-ni k’orhunta-echa-ni=xï lola-ni ewa-a-a-ka=ni

DEM.PL-OBJ tamal-PL-OBJ=FOC Lola-OBJ take-3OBJ.PL-FUT-ASS1/2=1 ‘These are the tamales that I will bring to Lola.’ (IH1: 89)

(15) sonku=chk’a jimini jucha tatan-kurhi-sïn-ka, wiría-ni=ch’e rapidly=certainly there 1PL.IND gather-REF-HAB-ASS1/2 run-NF=1PL

‘Rapidly, we gather there, we run.’ (CH3: 20)

3.2. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE SECOND POSITION

The second position or Wackernagel’s position is generally the most frequent position for the enclitic (Aikhenvald 2002, Siewierska 2004, inter alia). This is a fixed position that may be classified according to two principles: (i) phonological position regardless of the grammatical class of the host, and (ii) position depending on the grammatical class of the host. In Purepecha, the second-position fixed enclitics are chosen regardless of the grammatical class of the host.

In main clauses and in dependent and independent clauses, the second-position enclitics occur after the first constituent of the clause: the host may be a simple element, such as wariti ‘woman’, in (16), or a noun phrase, such as juchi tata ‘my father’, illustrated by example (17). A large number of elements function as hosts (see section 3.3.). One of the functions of a second-position enclitic is to delimit the beginning of a clause – an independent clause as in (16) and (17), and a dependent clause as illustrated by =kxï in (18)

(16) wariti=na ma ja-ra-ni jima, woman=EV a be.there-FT-NF there ‘They said that a woman was there, ...’ (TN5: 24)

(17) juchi tata=rini kwane -xïn-ti xiwatsï k’éri-ni

POS1 father=1OBJ lend-HAB-ASS3 coyote old-OBJ

‘My father lends me to the old coyote ....’ (CC11: 92)

(18) Pacanda anapu-echa=na wanta-x-p-ti [éxki=kxï pa-pirin-ka] Pacanda ORIG-PL=EV tell-AOR-PAST-ASS3 SUB=3PL take-COND-SUBJ

‘Those from Pacanda had told that they should carry it.’ (PC2: 65) 3.2.2. Two types of exception

There are two clear exceptions to the second position: the first is with interjective markers, the second with coordinating conjunctions. In the first exception, interjective markers, such as jo in example (19), are considered to be outside the clause: a clear argument for this is the pause (transcribed as a comma) attested between the interjection and the beginning of the clause. So the pronominal enclitic appears after the first constituent of the clause, Selia in this example. (19) jo, Selia=rini arhi-x-ti inte-ni wantantskwa-ni

yes Celia=1OBJ tell-AOR-ASS3 DEM-OBJ story-OBJ

‘Yes, Celia told me a story.’ (JR25: 36)

In the second exception (after coordinating conjunctions), some variations exist: in some examples, the pronominal enclitic appears after the conjunction, as illustrated with ka ‘and’ in example (20a) and peru ‘but’ in example (21a). In other examples, the conjunction is considered to be a clausal connector that occurs outside the clauses it links. Thus, the enclitic appears after the constituent that follows the connector, which is considered to be the first constituent of the clause, as in (20b) and (21b).

(20)a.ka=kxï ikya-pa-rini wanto-nts-kwarhe-pa-ntha-ni and=1PL get.angry-CENTRIF-PART.PA tell-IT-MID-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF

xa-rha-x-p-ka

be.there-FT-AOR-PAST-ASS1/2

‘...and getting angry, we discussed.’ (IH10: 128)

(20)b. ka, jini=nha ni-ra-ni jurimpitkwa, tioxïo incha-ni, and there=EV go-FT-NF straight ahead church enter-NF

‘and, they said that there he has gone straight ahead, he has entered the church.’

(21)a.sani khe-ni ka, no=teru=chk’a anta-nku-ni little grow-NF and NEG=other=certainly gain-INTS-NF

peru=ch’e arhi marhua-ta-xa-ka

but=1PL DEM employ-CAUS-PROG-ASS1/2

‘He grows a little, and, this is not sufficient, but we continue to use it.’ (TN2: 55) (21b) mí-ti-xïn-ka=ni kará-ni peru no=ni ú-xïn-ka

know-face-HAB-ASS1/2=1 write-NF but NEG=1 may-HAB-ASS1/2

jimpoka no jatsi-ø-ka ma lapixï because NEG have-AOR-SUBJ a pencil

‘I know how to write but I cannot because I do not have a pencil.’ (ZP3: 118)

In the majority of situations, as illustrated in (20), the strategy is transparent, because a pause codified as a comma is expressed in (20b). In this example, ka ‘and’ is a discursive connector that links two clauses; it is considered to occur between the two clauses and therefore outside them. In the situation illustrated by the examples in (21), the choice is not so clear, because in (21a) there is no pause and the referent is the same in the two clauses. These two criteria indicate a greater degree of continuity between the two clauses; generally in this situation the enclitic should appear after the conjunction, but this is not the case in (21a). In my corpus, there are a number of examples, including (21a), which are not easy to explain in terms of discursive relevance. The explanation has to be connected with the position of those enclitics which have exhibited some variation over five centuries. In the sixteenth century, coordinating conjunctions were considered to be the first position of the clause, as in (22a), although a few occurrences of coordinating conjunctions outside the clause are attested, as in (22b). In the sixteenth century coordinating conjunctions were most frequently considered to be inside the clause; today the opposite is the case, and coordinating conjunctions represent the least frequent host for pronominal enclitics (see table 5).

(22)a. caquini ma quere

ka=kini ma kére-ø and=2OBJ one join-INT

‘And you, does someone join you?’ (Lagunas (1983 [1574]: 423) (22)b. ca yquirengua ma naranja exesirahaca

ka iki=re=nkwa ma naranja exe-sira-ja-ka and SUB=2=order one orange see-HAB-PRES-SUBJ

‘And if you see one orange ...’ (Medina Plaza 1998 [1575]: 36)

3.3. HOSTS

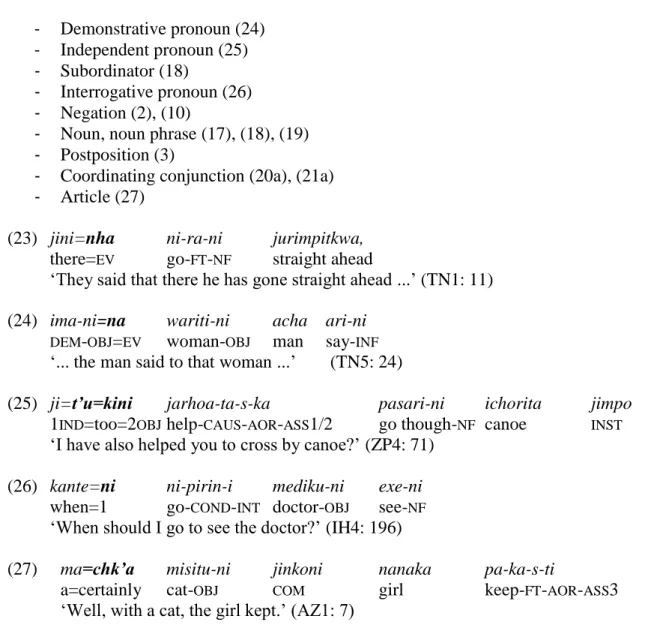

In Purepecha, second-position enclitics have a fixed position within a clause regardless of the grammatical class of their host. A great variety of hosts are attested; the list below is organized by frequency of the element that functions as host for second-position enclitics. This is an average of the frequencies for pronominal enclitics (see table 5) and non-pronominal fixed enclitics (see table 6).

- Adverb (5), (15) - Deictic marker (23) - Verb (13), (15), (21b)

- Demonstrative pronoun (24) - Independent pronoun (25) - Subordinator (18)

- Interrogative pronoun (26) - Negation (2), (10)

- Noun, noun phrase (17), (18), (19) - Postposition (3)

- Coordinating conjunction (20a), (21a) - Article (27)

(23) jini=nha ni-ra-ni jurimpitkwa, there=EV go-FT-NF straight ahead

‘They said that there he has gone straight ahead ...’ (TN1: 11) (24) ima-ni=na wariti-ni acha ari-ni

DEM-OBJ=EV woman-OBJ man say-INF

‘... the man said to that woman ...’ (TN5: 24)

(25) ji=t’u=kini jarhoa-ta-s-ka pasari-ni ichorita jimpo 1IND=too=2OBJ help-CAUS-AOR-ASS1/2 go though-NF canoe INST

‘I have also helped you to cross by canoe?’ (ZP4: 71) (26) kante=ni ni-pirin-i mediku-ni exe-ni

when=1 go-COND-INT doctor-OBJ see-NF

‘When should I go to see the doctor?’ (IH4: 196)

(27) ma=chk’a misitu-ni jinkoni nanaka pa-ka-s-ti

a=certainly cat-OBJ COM girl keep-FT-AOR-ASS3

‘Well, with a cat, the girl kept.’ (AZ1: 7)

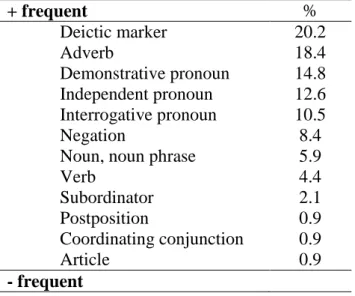

The frequencies for pronominal fixed enclitics (see table 5) and non-pronominal fixed enclitics (see table 6) are not exactly identical. Twelve constituents represent the possible hosts for the second-position fixed enclitic. In the corpus, pronominal enclitics are not attached after articles that are always the hosts for non-pronominal enclitics, so only eleven constituents appear with pronominal second-position enclitics, as illustrated by table 4. Adverbs, subordinators, and verbs constitute the three most frequent constituents that function as hosts for second-position pronominal enclitics. The high frequency of the subordinator as host shows that in dependent clauses, pronominal enclitics almost always attach after this element. At the bottom of this list, postposition and coordinating conjunctions almost never function as possible hosts.

Table 5. Frequency of the constituents in first position to which pronominal enclitics are attached + frequent % Adverb 19.8 Subordinator 17.6 Verb 17.5 Deictic marker 10.8 Demonstrative pronoun 9.8 Independent pronoun 8.1

Interrogative pronoun 5.6

Negation 5.5

Noun, noun phrase 2.8 Postposition 1.4 Coordinating conjunction 1.1

- frequent

Deictic markers and adverbs are the two constituents that occur most frequently as hosts for second-position non-pronominal enclitics. The selection of these constituents seems to be related to the meaning of non-pronominal discursive enclitics. At the bottom of this list, postpositions, coordinating conjunctions, and articles almost never function as possible hosts.

Table 6. Frequency of the constituents in first position to which non-pronominal enclitics are attached + frequent % Deictic marker 20.2 Adverb 18.4 Demonstrative pronoun 14.8 Independent pronoun 12.6 Interrogative pronoun 10.5 Negation 8.4

Noun, noun phrase 5.9

Verb 4.4 Subordinator 2.1 Postposition 0.9 Coordinating conjunction 0.9 Article 0.9 - frequent

The comparison of the two tables above shows that adverbs are the most frequent hosts. This is not surprising, as adverbs and deictic markers are frequently the first constituent in clauses. By contrast, postpositions and coordinating conjunctions are the least frequent hosts. Three types of elements – deictic markers, verbs, and subordinators – exhibit clear differences: the first is frequent in the case of non-pronominal enclitics and less common for pronominal enclitics, whereas the opposite holds for the other two.

Figure 1. Comparison of the frequency of elements in first position to which enclitics are attached

3.4. ENCLITIC STRINGS

3.4.1. Ordering in enclitic strings

Different enclitic strings, also known as enclitic clustering, are possible in Purepecha: - two non-pronominal enclitics, as in (21a) and (28)

- one non-pronominal and one pronominal enclitic, as in (2) and (25)

- two non-pronominal enclitics and one pronominal enclitic, as in (29) and (30) (28) jima=k’u=sï anta-ra-ni General Lázaro Cárdenas,

there=only=FOC appear-CAUS-NF General Lázaro Cardenas ka isï=k’u=nha wana-na-cha-ni yapuru,

and thus=only=EV go across-internal-neck-NF wherever

‘It was only there that General Cárdenas appeared and they said that he was moving here and there.’ (TN1: 9)

(29) jini=chk’a=ri=sï mi-ti-a-ka arhi-s-ti tempa there=certainly=2=FOC know-face-FUT-ASS1/2 tell-AOR-ASS3 wife.KPOS3 ‘“It is there that you will recognize him”, said his wife.’ (PU7: 98)

(30) pawani=t’u=chk’a=ri ni-a-ka

tomorrow=too=certainly=2 go-FUT-ASS1/2

‘Also tomorrow, you will go.’ (JR66: 7)

It is impossible to find two pronominal enclitics in second position; generally only the object is expressed, as in (11), or independent pronouns are used, as in (5) and (25) (see section 5.2.2).

Aikhenvald (2002: 52-53) observes that clitics “tend to attach to their host in an idiosyncratic order.” This is the case in Purepecha, in which enclitic strings have a strict order: the non-pronominal floating enclitic precedes the non-non-pronominal fixed enclitic, then generally the pronominal enclitic appears at the end of the string, as illustrated in (30). The canonical order within the string is:

=non-pronominal (floating) = non-pronominal (fixed) = pronominal

However, the two non-pronominal fixed enclitics, =sï and =na, generally appear at the end of the string. This is always the case for the evidential =na, as illustrated in (31). The focus =sï

generally appears at the end of the string, as in (32), although some occurrences of =sï in the canonical position, that is, before the pronominal enclitic, are attested, as illustrated by examples (33a) and (33b).

(31) xasï=ksï=nha kustakwa jinkoni pa-s-ti, next=3PL=EV music COM take-AOR-ASS3

jikwa-ra-ni=ksï=nha ya, ka ampa-tsi-ku-ni=ksï=nha ya bath-CAUS-NF=3PL=EV now and be.clean-Z.SUP-3APP-NF=3PL=EV now

‘They said that then they took her with music, they said that they bathed her, and they combed her.’ (TN2: 47)

(32) ka, xini=ri=s warha-s-ka

and there=2=FOC dance-AOR-ASS1/2

‘And, there is where you danced.’ (TD1: 35) (33)a.ixú=sï=ni ire-ka-ni

here=FOC=1 reside-FT-NF

‘Here is where I am living.’ (JR73: 95) b. ampe=sï=ri u-ni ja-ki jimini

what=FOC=2 do-NF be.there-INT there ‘What are you doing there?’ (JR39: 827) 3.4.2. Diachronic comments

In the sixteenth century, the order was in reverse, that is, =pronominal =non-pronominal, as illustrated by example (34).

(34) care ma ambeta, noretero vingapequa exèra

ka=re ma ampeta-ø no=re=tero vingapequa exera-ø and=2 one seduce-INT NEG=2=other force show-INT

‘and you, haven’t you seduced or forced someone?’ (confesionario 2, 13)

One exception exists for the first-person enclitic, which exhibited the same order as at present, =non-pronominal =ni, as illustrated by example (35).

(35) andiquiteroni ne vandan hurendahpepiringa

anti-ki=tero=ni ne wanta-ni juren-ta-p’e-pirin-ka

por qué-REL=other=1 someone tell-NF know-CAUS-ANTIP-COND-SUBJ

‘If only I would teach someone.’ Gilberti 1987 [1558]: 31)

Two hypotheses are possible: either the first person enclitic had a specific behavior, and then by analogy the other enclitics modified their position, or else the change of position reveals a change that began before the sixteenth century with the first person and has continued since then (Chamoreau and Villavicencio in press).

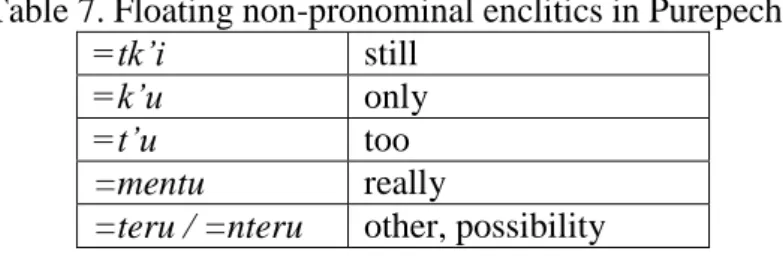

Floating enclitics have no fixed position; they are attached to a particular constituent under a special discourse condition. In Purepecha, floating enclitics have adverbial meaning and are positioned close to a constituent that is modified by the enclitic (Aikhenvald 2002: 46-47). 4.1. NON-PRONOMINAL FLOATING ENCLITICS

Some non-pronominal enclitics in floating position are found in my corpus; all have a specific adverbial meaning, as illustrated by table 7.

Table 7. Floating non-pronominal enclitics in Purepecha =tk’i still

=k’u only =t’u too =mentu really

=teru / =nteru other, possibility

Three of the non-pronominal enclitics are frequent, namely =k’u, =teru (or =nteru), and =t’u, as illustrated by example (37). Only a few occurrences of the other two are found in the corpus, and it seems that these elements are in disuse nowadays. In the sixteenth century, Gilberti (1987 [1558]: 197-199) and Lagunas (1983 [1574]: 88-92) described seventeen elements that we can classify as non-pronominal enclitics (second-position and floating). Today, both categories have nine elements (four second-position enclitics and five floating enclitics), meaning that almost half of the elements have been lost.

(36) kara-sïn-ka=ksï i=t’u ma=teru enka xu=k’u ire-ka-ni write-HAB-ASS1/2=1PL DEM=too a=other SUB here=only reside-FT-NF

ja-ka inte=t’u kara-sïn-ti ka ima=t’u ma=teru jiniani, be.there-SUBJ DEM=too write-HAB-ASS3 and DEM=too a=other there ‘We write, this other one (writes) too that he lives only here, this one also writes and that other one also (writes) there.’ (AR1: 25-26)

4.2. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE FLOATING POSITION

It is not easy to describe the floating position, because by definition it is not fixed and depends on the localization of the element modified by the enclitics. Nevertheless, two places are preferred: enclitics may be encliticized to the element or to the end of the noun phrase modified by the adverbial category codified by the enclitic. In this context, it seems to occur in any position within the clause, as illustrated by example (36).

At the same time, the element modified by the non-pronominal enclitic may occur in the first position of the clause, with the enclitic in second position, as in (37):

(37) né=teru, enka táte-mpa-ni jinkuni who=other SUB father-KPOS3-OBJ COM

wanto-nts-kuarhe-pa-nt’a-ni ja-ka talk-IT-REF-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF be.there-SUBJ

‘Who else? (This is) the one who is talking with his father.’ (IH53: 529)

These non-pronominal enclitics generally are attracted to the second position in order to combine with other enclitics, as illustrated by examples (28) and (30). Non-pronominal enclitics modify the elements attached to them.

4.3. HOSTS

Non-pronominal floating enclitics have a large variety of hosts. The comparison between the list below and the hosts of second-position enclitics (in section 3.3) shows that the hosts are the same whatever the type of enclitic. The differences reside in the frequency with which each element is used as host, according to the type of enclitic. The hosts in the list below are listed according to their frequencies, from the most to the least frequent (see table 8).

- Demonstrative pronoun (36) - Independent pronoun (38) - Deictic marker (36) - Article (36) - Negation (39) - Interrogative pronoun (37) - Adverb (40)

- Noun, noun phrase (41) - Subordinator (42) - Verb (43)

- Coordinating conjunction (44) - Postposition (45)

(38) ka xaxa ji=t’u=ni t’arhepi-ni wena-ni and after 1IND=too=1 be.old-NF begin-NF

‘and, after, I also begin to grow old.’ (AR2: 198) (39) no=taru=ksï ima-echa-ni jatsi-a-s-ka

NEG=other=1PL DEM-PL-OBJ have-3PL.OBJ-AOR-ASS1/2 ‘We no more had them (papers).’ (AR1: 43)

(40) iasï=mintu eki=ni xani sesi nitama-kwarhe-ni ja-ka

now=really SUB=1 very well live-REF-NF be.there-SUBJ

‘Just now (it is) when I am living very well.’ (JR55: 103)

(41) tiósio kampanu-echa=t’u ú-nt’a-s-ti uá-mu-ku-ni

church bell-PL=too start-IT-AOR-ASS3 hit-mouth-TRANSLOC-NF

‘In the church, also the bells started ringing’ (IH53: 209) (42) nonema mí-te-s-ti na enka=mentu já-p-ka

NEG know-face-AOR-ASS3 how SUB=really be.there-AOR.PAST-SUBJ

‘He never knew how really it has occurred.’

(43) anti=ri=sï no ni-ra-ki=t’u t’upuri japu ata-ra-nt’a-ni jini why=2=FOC NEG go-FT-INT=too dust nixtamal sell-CAUS-IT-NF there

‘Why don’t you go also there in order to sell ashes?’ (IH24: 106)

(44) peru=t’u=chk’a, k’o, botella-icha, peta-nha-ni but=too=certainly yes bottle-PL request-PAS-NF

(45) ajta jiniani ire-ka-s-ti, chari tata jingoni=t’u, as far as there live-FT-AOR-ASS3 POS2PL father COM=too primu-e-s-ti ima=t’u

cousin-PRED-AOR-ASS3 DEM=too

‘He lived up there, with your father too, he is also a cousin.’ (AR1: 10)

Four constituents – demonstrative pronouns, independent pronouns, deictic markers, and articles – are the most frequent hosts for floating enclitics (see table 8). The high frequency of the article ma ‘a’ is due to the grammaticalization of the numeral ma ‘one’ in the indefinite article (Chamoreau 2012a) and the use of ma with =nteru or =teru and =k’u. The first constituents, ma=nteru or ma=teru, mean ‘other, another’ while ma=k’u means ‘only.’ These three constituents are so frequent, especially the former, that we may hypothesize that they are lexicalized or in course of being lexicalized (46).

(46) ma=teru xas sentavu-e-s-p-ti

a=other type money-PRED-AOR-PAS-ASS3

‘This was another type of money.’ (SF1: 23)

Table 8. Frequency of the constituents to which non-pronominal floating enclitics are attached

+ frequent % Demonstrative pronoun 19.2 Independent pronoun 17.6 Deictic marker 17.6 Article 17.6 Negation 7.9 Interrogative pronoun 6.2 Adverb 5.2

Noun, noun phrase 4.8 Subordinator 1.2 Verb 1.2 Coordinating conjunction 0.9 Postposition 0.9 - frequent 4.4. ENCLITIC STRINGS

Non-pronominal floating enclitics appear in the first position in the string of enclitics. Three possibilities are attested:

=non-pronominal (floating) =non-pronominal (fixed) (47) =non-pronominal (floating) =pronominal (48)

=non-pronominal (floating) =non-pronominal (fixed) =pronominal (49)

(47) no=teru=chk’a anta-nku-ni

NEG=other=certainly gain-INTS-NF

(48) ji=t’u=kini jarhoa-ta-s-ka pasari-ni ichorita jimpo 1IND=too=2OBJ help-CAUS-AOR-ASS1/2 go though-NF canoe INST

‘I have also helped you to cross by canoe?’ (ZP4: 71) (49) t’u=t’u=chk’a=ri ni-a-ka

2IND=too=certainly=2 go-FUT-ASS1/2

‘You too will go.’ (JR37: 119)

As I showed in section 3.4., this is a new position, as in the sixteenth century the opposite position was attested. The order at that time was =pronominal =non-pronominal except for the first person non-pronominal enclitic.

5. PREDICATE ENCLITICS

In this position, the enclitics are associated with words that function as the syntactic predicate of the clause.

5.1. Predicate enclitics versus verbs in first position as hosts for second-position enclitics In Purepecha, pronominal enclitics have recently begun to appear in a new position, depending on the type of their grammatical host, that is, the enclitics are associated with words that function as the syntactic predicate of the clause. For methodological reasons, I treat predicate enclitics as different from verbs in first position that are hosts for second-position pronominal enclitics. This is relevant because in Purepecha verbs are the category that most frequently functions as a predicate. In this section and the following, I will discuss the relation between the two positions.

Enclitics are attached to the end of the predicate after the tense-aspect-mood markers. This is also a fixed position, but what has changed is that predicates do not have to appear in the first position of the clause but can appear in any position, generally after the subject. This movement to the right from second-position enclitic to predicate enclitic only occurs with pronominal enclitics. The host is chosen for its syntactic and pragmatic properties, and is frequently the predicate itself, as illustrated by example (50), or in a few cases, the last element before the predicate when it is an adverb or a negation, as in (51).

(50) ka yontki anapu ima-nki ire-kwari-p-ka=ksï Chao and before origin DEM-SUB reside-REF-AOR.PAST-SUBJ=3PL Chao

‘and since before they lived in Chao.’ (TM1: 16)

(51) xani arhi-a-xïn-ka=ni éxki no=kxï itsu-ta-ø-ka

much say-3PL.OBJ-HAB-ASS1/2=1 SUB NEG=3PL absorb-CAUS-AOR-SUBJ

‘I always ask them not to smoke.’ (IH4: 91)

Before we analyze the characteristics of this new position, it will be useful to ascertain the frequency of occurrence of the verbs that appear in first position as the hosts of second-position pronominal enclitics (see table 5), in order to evaluate the frequency of occurrence of the predicate in this position. The aim is to determine whether this new position is a consequence of a morphosyntactic feature of Purepecha, namely that the predicate is a grammatical constituent attracting the pronominal enclitic.

In table 5 above, verbs are one of the three most frequent constituents functioning as the host of second-position pronominal enclitics with adverbs and subordinators. This is not a surprise in the case of verbs, as it is a well-known feature cross-linguistically (Givón 2011: 182, Heine and Song 2011). But it is new in Purepecha: in the sixteenth century, verbs were generally never positioned at the beginning of a clause (Chamoreau and Villavicencio in press). The high frequency of verbs as hosts of second-position enclitics is significant in two types of text. The first type of text is a narrative with a lot of chain-medial clauses, which contain non-finite clauses with referential continuity; these chain-medial clauses are only constituted by predicates that express a succession of events or indicate overlapping events (Chamoreau in press, for a detailed study of these clauses), as illustrated by example (52). In this context, generally only the pronominal enclitic that functions as subject is expressed.

(52)a.ka tsïma anima-icha wanta-pa-ntha-ni, and DEM.PL soul-PL tell-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF

‘and these souls were telling, b. tsipi-pa-ntha-ni=kxï,

be.happy-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF=3PL

they were happy,

c. tere-kurhi-pa-ntha-ni=kxï,

laugh-MID-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF=3PL

they were laughing, d. piri-pa-ntha-ni=kxï,

sing-CENTRIF-CENTRIF-NF=3PL

they were singing ...’ (JR2-4.10)

Here the second position is perhaps due to a change in first position. The coordinating conjunctions are no longer treated as being in first position in the clause. Generally, in my corpus, the constituent that appears after the coordinating conjunction is the verb, as illustrated by example (53), above all when referent continuity is attested. Thus, the verb occurs more frequently in first position, and becomes a “frequent candidate to host second-position clitics” (Givón 2011: 190).

(53)a.xasï=ksï=nha kustakwa jinkoni acheti-echa pa-s-ti, next=3PL=EV music COM man-PL take-AOR-ASS3

‘They said that then the men took her with music, b. ka, jikwa-ra-ni=ksï=nha ya,

and bathe-CAUS-NF=3PL=EV now

and, they said that they bathed her,

c. ka, ampa-tsi-ku-ni=ksï=nha ya. and be.clean-Z.SUP-3APP-NF=3PL=EV now and, they said that they combed her.’ (TN2-47)

The second type of text was narrated by bilingual speakers who use Spanish as a communicative language. These texts also exhibit a high frequency of predicate verbs (which

are not in first position in the clause); this is perhaps a consequence of the contact with Spanish, a language in which referents occur close to the predicate (see sections 5.3. and 6). 5.2. MORPHOSYNTACTIC POSSIBILITIES FOR THE PREDICATE ENCLITIC

5.2.1. New possibilities

Five new morphosyntactic possibilities have been identified. Going from the most frequent strategy to the least frequent, these are:

1. After the predicate: this is more frequent for the subject, as in (50), than for the object, as in (54).

2. Pronominal agreement: independent pronoun and enclitic after the predicate, as in (55a), or noun phrase and enclitic after the predicate, as in (56). This strategy is very infrequent for the object because independent pronouns are used. I have found only one occurrence, as illustrated in (55b).

3. Repetition of the enclitic functioning as the subject (in the same clause): the second-position enclitic and after the predicate (57). For the object, this strategy has not been found to occur.

4. Pronominal agreement: independent pronoun, second-position enclitic, and enclitic after the predicate, as in (58). This strategy has been found for the subject, never for the object.

5. After an element that occurs before the predicate: generally negation, (51), but there are two examples with an adverb (59). This strategy has been found for the subject, never for the object.

1. After the predicate

(54) jima pia-chi-a-ti=kini, eki=rini xe-ka there buy-1/2APP-FUT-ASS3=2OBJ SUB=1OBJ see-SUBJ

‘There, he will buy (something) for you when he will see me.’ (OC2: 21-23) 2a. Pronominal agreement: independent pronoun and enclitic after predicate (55)a.ka t’u tata generali-i-x-ki=ri a no

and 2IND sir general-PRED-AOR-INT=2 ah NEG

‘and, YOU are the general, aren’t you?’ (TN1: 13)

b. juchants’ïni, nanti ari-sïam-p-ti=ts’ïni 1PL.IND.OBJ mother tell-HAB-PAST-3ASS=1PL.OBJ

‘To US, my mother has said to us ...’ (PC2: 59)

2b. Pronominal agreement: noun phrase and enclitic after the predicate

(56) iontki jima inte-ni ireta-ni jimpo kw’íripu-echa before there DEM-OBJ village-OBJ LOC person-PL

janhwa-ri-nt’a-sïren-ti=ksï anchekwareta ú-ni strengthen-body-IT-HAB.PAST-ASS3=3PL work do-NF

‘Before, there, in this village, the persons tried very hard to work.’ (TN1: 1)

3. Repetition of the enclitic

because=1 before=too begin-AOR-SUBJ=1 divide-MID-NF

‘because before I also began to drink.’ (OC5: 167)

4. Pronominal agreement: independent pronoun, second-position enclitic, and enclitic after predicate

(58) eki=ni ji ni-nt’a-s-p-ka=ni

when=1 1IND go-CENTRIF-AOR-PAST-SUBJ=1

‘When I came back ...’ (JR29: 193)

5. After an element that occurs before the predicate

(59) tepekwa-icha nanaka-icha-iri sési=kxï ja-rha-x-ti

braid-PL girl-PL-GEN well=3PL be.there-FT-AOR-ASS3 ‘The girls’ braids are beautiful.’ (JR3: 144)

5.2.2. Two pronominal enclitics (subject and object) in the same clause

The five new possibilities shown above increase the probability that two pronominal enclitics will occur in the same clause, the one functioning as subject and the other as object. It is impossible to find both together in the second position (see section 3.4.1.). Three strategies exist for expressing both referents in the same clause.

The most common strategy respects the rule that prevailed in the sixteenth century, that is, only the enclitic that functions as object is codified, as illustrated by example (60). This is a well-known feature cross-linguistically for the transitive verb (Givón 2011: 172). The presence of the assertive mood that expresses the first and second persons, –ka, permits of a single reading: that is, if the overt object is the second person singular, then the covert subject is the first person singular, as illustrated by example (60a). The converse is shown in example (60b), in which the overt object is the first person singular, so that the covert subject must be the second person singular. In order to lay stress on the participant who functions as the subject, or to avoid possible ambiguity, the independent pronoun is used, as in (61).

(60)a.no=reni kurha-nku-xïn-ka

NEG=1OBJ listen-INTS-HAB-ASS1/2

‘You do not pay attention to me.’ (CN56: 124) b. witsintikwa=kini jwa-chi-x-ka xáni

yesterday=2OBJ bring-1/2APP-AOR-ASS1/2 much ‘Yesterday I brought you so much.’ (JR589: 337)

(61) ji=t’u=kini jarhoa-ta-s-ka pasari-ni ichorita jimpo 1IND=too=2OBJ help-CAUS-AOR-ASS1/2 go though-NF canoe INST

‘I have also helped you to cross by canoe?’ (ZP4: 71)

Today, two new strategies are present, both exhibiting the overt presence of two pronominal enclitics in the same clause (an impossibility in the sixteenth century). The first new strategy generally appears to avoid possible ambiguities, as illustrated by example (62) with the interrogative mood –ki (which does not distinguish person). The subject is expressed in the second-position enclitic =ni, and the object appears in a position between the first constituent of the clause and the predicate. The order of the pronominal enclitics is always the same: the subject appears in the second position. This strategy generally creates, as in (62), a pronominal agreement for the subject.

(62) no=chk’a=ni ji=t’u=kini jarhoa-ta-s-ki p’iku-nt’a-ni

NEG=certainly=1 1IND=too=2OBJ help-CAUS-AOR-INT harvest-IT-NF

‘Well, had I not also helped you to harvest?’ (JR89: 343)

The second new strategy is used only when the clause has two constituents that constitute the two hosts, as illustrated in (63). In this situation, the object pronominal enclitic is attached to the first constituent, =rini, and the pronominal enclitic that functions as the subject appears after the predicate, =ri. Generally only the first pronominal enclitic, the one that has the object function, is attested, as illustrated by example (60). So the presence of an overt pronominal enclitic that functions as the subject is redundant and participates in the referential continuity (see section 5.4.).

(63) yasï=rini ikya-ta-s-ka=ri

now=1OBJ angry-CAUS-AOR-ASS1/2=2

‘Now, you make me angry.’ (JN25: 388) 5.3 QUANTITATIVE DATA

Quantitative data are highly relevant to proving that the predicate enclitic ought to be considered as a new strategy that is marked and infrequent. I have gathered a corpus of 123 texts (narrative and conversation) in which I count 4182 pronominal enclitics: 3710 function as the subject and 472 as the object. This result shows that the majority of the clauses are intransitive or transitive with a third-person object (one that has a covert marker, see table 3). In this corpus, only 228 pronominal enclitics, or 5.5%, were not found in the second position. This result shows that the predicate enclitic is very infrequent: 209 of these enclitics function as the subject and 19 as the object. Another finding is that 216 enclitics occur in main clauses, 12 in dependent clauses. In dependent clauses, the referent frequently attaches after the subordinator (see section 3.3. and table 5).

Table 9 displays the different strategies for codifying referents (outside the nominal codification). They are generally expressed by a pronominal enclitic, and only very infrequently by an independent pronoun (line g). The non-predicate enclitic position accounts for 94.5% of the occurrences in only three types of position, (a), (e), and (g). Conversely, the predicate enclitic only accounts for 5.5%, and in five types of position, (b), (c), (d), (f), and (h). Table 9 also shows the current variation in the codification of referents in particular as enclitics. The development of the predicate enclitic explains this variation. Another consequence is an increase in the contexts in which independent pronouns are used. In the sixteenth century, independent pronouns were infrequent (Chamoreau and Villavicencio in press).

Table 9. Frequency of ways to codify grammatical participants

a. Second position

b. After the predicate (not in second position) c. Independent pronoun + after the predicate d. Second position + after the predicate e. Independent pronoun + second position

f. Independent pronoun + second position + after the predicate g. Independent pronoun

h. After an element that occurs before the predicate

93.8 2.9 1.6 0.5 0.5 0.3 0.2 0.2 – frequent

The analysis of the corpus identifies some specific texts in which the use of predicate enclitics (not in second position) is more frequent. These texts display two types of pragmatic and sociolinguistic characteristic. On the one hand, there are autobiographical stories or narratives with only one or two referents, that is, narratives in which the main referent has a very prominent role and exhibits high continuity. On the other hand, texts with a frequent use of predicate enclitics are narrated by bilingual speakers who have had at least an intermediate-level school education or who use Spanish more than Purepecha in everyday communication. There are four representative texts. The first two are autobiographical stories told by Purepecha speakers (from Cuanajo and Jarácuaro) who use Purepecha in everyday communication (Chamoreau 2012a, 2012b, and 2012c for more details). Predicate enclitics represent respectively 10% and 18% of total enclitic occurrences. The third story is told by a man from Arantepacua who has studied in Morelia and has responsibilities in his village; he uses Spanish more than Purepecha. In his account of a traditional legend, 14% of the occurrences are predicate enclitics. The fourth example is an autobiographical story by a woman who lives in Mexico City (Capistrán 2004). In this text, 36% of the occurrences are predicate enclitics.

A comparison between the types of context for predicate position and the types in which the verbs are in first position as hosts for second-position enclitics (see section 5.1.) brings out two relevant types of context and gives some clues to explaining both strategies. They are linked on the one hand to referential continuity in discourse, in autobiographical stories, and in chain-medial clauses in narratives, and on the other hand to contact with Spanish, a language in which referents are codified close to the verb, in particular with tense-aspect-mood markers at the end of the predicate (see section 6).

5.4. DISCURSIVE EXPLANATION

Second-position pronominal enclitics are unmarked and are the most frequent: that is, they are used by default both for referential continuity, as illustrated above by examples (52) and (53), and for switch reference, as illustrated by example (64). In examples (53b) and (53c), the enclitics attach after the verb because the coordinating conjunction is not considered to form part of the clause.

Pronominal enclitics that appear after an element positioned before the predicate behave in the same way. Although they are very infrequent (see table 9), they may appear both for the same reference, as in (59), and in the context of switch reference, as in (51).

Switch reference

SUB=2 come.back-IT-NF be.there-AOR.PAST-SUBJ NEG=3PL

sési ixe-pa-ntsha-s-p-ti

well see-CENTRIF-IT-AOR-PAST-ASS3

‘When you came back, they didn’t see well.’ (TR59: 291)

Pronominal enclitics attached after the predicate and repetition of the enclitics in the same clause (in the second position and after the predicate) are used for referential continuity, as illustrated by example (65).

Referential continuity (same subject)

(65)a.tsípku urhu-sïaan-ti=ksï japu daybreak grind-HAB.PAST-ASS3=3PL nixtamal ‘In the morning, they were grinding nixtamal,

b. ka inchaterhu trigu urhu-ni=ksï and afternoon wheat grind-NF=3PL

and in the afternoon, they were grinding wheat.’ (TR8: 73)

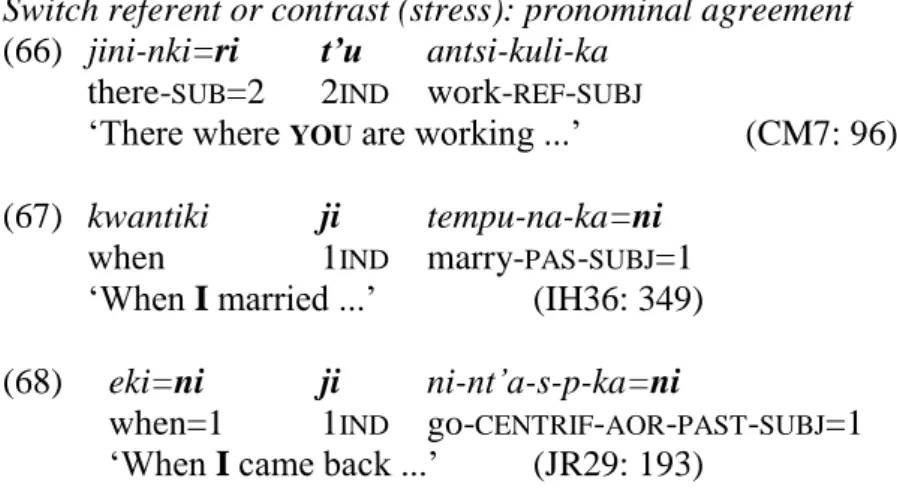

Pronominal agreement is used for the introduction or the re-introduction of a referent and in order to underline a contrast of referents, that is, to indicate a switch referent, as illustrated by examples (66) and (67). Pronominal agreement with three elements (independent pronoun + second position + after the predicate) is used in cases of strong stress and contrast, as shown by example (68).

Switch referent or contrast (stress): pronominal agreement (66) jini-nki=ri t’u antsi-kuli-ka

there-SUB=2 2IND work-REF-SUBJ

‘There where YOU are working ...’ (CM7: 96)

(67) kwantiki ji tempu-na-ka=ni when 1IND marry-PAS-SUBJ=1

‘When I married ...’ (IH36: 349) (68) eki=ni ji ni-nt’a-s-p-ka=ni

when=1 1IND go-CENTRIF-AOR-PAST-SUBJ=1

‘When I came back ...’ (JR29: 193)

The eight possible positions may be divided into two types as illustrated in table 10: one includes the positions that are independent of referential continuity and may appear in contexts of referential continuity or switch reference (a and b). The other includes the positions that are sensitive to the continuum of referential continuity, from same referent (c and d) to switch referent in different contexts of referent introduction, stress, and contrast (e, f, g, and h).

Table 10. Pragmatic tendencies for using enclitics and a pronoun

a. Second position b. After an element occurring before the

predicate

c. After the predicate

d. Second position + after the predicate e. Independent pronoun + second position f. Independent pronoun

g. Independent pronoun + after the predicate

h. Independent pronoun + second position + after the predicate

– referential continuity (switch referent)

The relative sensitivity and dependence on referential continuity is new and still developing in Purepecha, whereas it is well-known in other languages (Givón 2011: 189; Hill 2005, 2011).

6. FINAL THOUGHTS

To sum up, Purepecha exhibits a combination of three types of enclitics, listed in table 11. Table 11. The three types of enclitics in Purepecha

Host Enclitics

Type 1 second position non-pronominal pronominal Type 2 end of the element or end of NP that

contains the element modified by the enclitic

non-pronominal Type 3 predicate (head) of the clause. pronominal

In the sixteenth century, only the first two types were attested, while today the third one is developing. Non-pronominal enclitics are stable in position and decreasing in number of elements (from seventeen in the sixteenth century to nine at present). In contrast, pronominal enclitics display variation in position and stability in number.

How has change in predicate position been possible? Three related hypotheses may be advanced to answer this important question. The first hypothesis for explaining change in predicate position and its restriction to pronominal enclitics is that pronominal enclitics choose their hosts because of their syntactic and discursive properties, exhibiting a head-attraction (see Haig 2008 for Western Iranian languages). Syntactic predicates generally express the main information. Cases of head-attraction for pronominal enclitics are described in the literature for Iranian languages (Haig 2008) and Romance languages (Vincent 2001). In earlier stages, ancient Iranian and Latin possessed pronominal second-position clitics. Today, Persian and Romance languages have pronominal markers placed close to the verb, usually within the verb phrase. This shift was analyzed by Haig (2008) as a case of attraction to the verb, that is, to the head that governs pronominal markers.

In Purepecha, the process began centuries ago when the pronominal enclitics moved to the end of the second-position enclitic string (see 3.4.). This process allowed the pronominal enclitics to move to the last position and to gain more freedom to move. The change is parallel to another change in first position: the coordinating conjunctions are no longer treated as first position in the clause. The verb occurs increasingly in first position, thus becoming a “frequent candidate to host second-position clitics” (Givón 2011: 190). Heine and Song (2011: 590) observe that “The majority of the languages of the world show person marking on the verb.” As a consequence of the increase of predicate position, distribution is restricted and enclitics no longer mark the limit of the clause.

The second hypothesis proposed is based on the analysis of discursive contexts in which predicate position is used: Purepecha is developing a discursive contrast for codifying the relation to referential continuity. Each position is specialized, that is, each position has a different referential function. The second position (except for verbs) is the unmarked position,

the predicate position and verbs as first position are used for referential continuity, while independent pronouns and pronominal agreement are clearly employed to introduce either a referent or stress and contrast, and generally for switch reference. In consequence, the use of independent pronouns is increasing, generally through pronominal agreement.

The third hypothesis is based on the analysis of characteristics of the speakers who narrated the texts with more frequent predicate positions: Spanish grammatical constructions may influence the change of position of pronominal enclitics in Purepecha (Chamoreau 2007, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). Spanish expresses the referents close to the verb as clitics or in the flexion associated with tense-aspect-mood (Vincent 2001). Almost all Purepecha speakers are bilingual, speaking at least Purepecha and Spanish. Spanish is the language of prestige, linked to education, a better standard of living, oral and written media, religion, administration, commerce, and work. The speakers who narrated these texts use Spanish more frequently in everyday conversation.

These three hypotheses propose different accounts of the first steps of contact-induced grammaticalization of pronominal enclitics. Purepecha exhibits changes in position, distribution (predicate), frequency (increase in pronominal enclitics attached to the verb), grammatical function (from clause delimitation to marking the predicate in whatever position), and referential function (specialization for each type of pronominal enclitic). The pronominal enclitic is extended to occupy a “new” position, suggesting a new and specialized meaning (Heine and Song 2011).

ABBREVIATIONS AOR=aorist APP=applicative ASS=assertive ASSOC=associative CAUS=causative CENTRIF=centrifuge COM=comitative COND=conditional DEM=demonstrative EV=evidential FOC=focus FT=formative FUT=future GEN=genitive HAB=habitual IND=independent INST=instrumental INT=interrogative INTS=intensive IT=iterative

KPOS=kinship possessive LOC=locative MID=middle NEG=negation NF=non-finite OBJ=object ORIG=origine

PART.PA=past active participle

PAS=passive PAST=past PL=plural POS=possessive PRED=predicativizer PROG=progressive REF=reflexive

SUB=subordinating conj. SUBJ= subjunctive TRANSLOC=translocative

Z.SUP=superior zone

Aikhenvald, A. 2002. Typological parameters for the study of clitics, with special reference to Tariana. In Word: A cross-linguistic typology, B. Dixon and A. Aikhenvald (eds.), 42-78. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, S. 1993. Wackernagel's revenge: clitics, morphology, and the syntax of second position. Language 69 (1): 68-98.

Bickel, B. and Nichols, J. 2007. Inflectional morphology. In Language typology and syntactic description, T. Shopen (ed.), 169-240. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, L., Kaufman, T., and Smith, T. 1986. Meso-America as a linguistic area. Language 62 (3): 530-570.

Capistrán, A. 2004. Wantántskwa ma warhíiti p’orhépecha, ‘Narración de una mujer p’orhépecha’. Tlalocan 14: 61-93.

Chamoreau, C. 2007. Grammatical borrowing in Purepecha. In Grammatical borrowing in cross-linguistic perspective, Y. Matras and J. Sakel (eds.), 465-480. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chamoreau, C. 2009. Hablemos purepecha, Wanté juchari anapu. Morelia: Universidad Intercultural Indígenas de Michoacán / IIH-UMSNH / IRD / CCC-IFAL / Grupo Kw’anískuyar(a simple or independent root or a dependent root marked by formative morpheme) hani de Estudiosos del Pueblo Purépecha.

Chamoreau, C. 2012a. Dialectology, typology, diachrony and contact linguistics. A multi-layered perspective in Purepecha. Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung (STUF - Language Typology and Universals) 65, 1: 6-25.

Chamoreau, C. 2012b. The geographical distribution of typologically diverse comparative constructions of superiority in Purepecha. Dialectology and Geolinguistics 20: 37-62. Chamoreau, C. 2012c. Contact-induced change as an innovation. In Dynamics of

contact-induced language change, C. Chamoreau and I. Léglise (eds.), 53-76. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chamoreau, C. in press. Non-finite clauses in Purepecha. In Finiteness and nominalization, C. Chamoreau and Z. Estrada Fernández (eds.). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Chamoreau, C. and Villavicencio, F. in press. Atracción hacia el núcleo en purépecha: los clíticos pronominales. Estudios lingüísticos.

Cutler, A., Hawkins, J., and Gilligan, G. 1985. The suffixing preference: A processing explanation. Linguistics 23: 723-758.

Dixon, R. 2004. Australian languages, their nature and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilberti, M. 1987 [1558]. Arte de la lengua de Michuacan. Morelia: Fimax.

Givón, T. 2011. Ute reference grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Greenberg, J. 1966. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of

meaningful elements. In Universals of language, J. Greenberg (ed.), 73-113. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Haig, G. 2008. Alignment change in Iranian languages: A construction grammar approach. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.

Heine, B. and Song, K.-A. 2011. On the grammaticalization of personal pronouns. J. Linguistics 47: 587-630.

Hill, J. 2005. A grammar of Cupeño. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press. Hill, J. 2011. Pronouns in the Cupan languages. Talk at the Seminario de Complejidad

Sintáctica, Hermosillo, November.

Lagunas, J. B. de. 1983 [1574]. Arte y Dictionario con otras Obras en lengua Michuacana. Morelia: Fimax.

Smith, T. 1994. Mesoamerican calques. In Investigaciones lingüísticas en Mesoamérica, C. Mackay and V. Vázquez (eds.), 15-50. Mexico City: IIF-UNAM.

Vincent, N. 2001. Latin. In The Romance languages, M. Harris and N. Vincent (eds.), 26-78. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zwicky, A. 1985. Clitics and particles. Language 61 (2): 283-305.

Zwicky, A. and Pullum, G. 1983. Cliticization vs. inflection: English n’t. Language 59 (3): 502-513.