Co-Opting Sustainabilities: The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’s National Solid Waste Policy

By Talia Mestel Fox B.A. in Linguistics Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts (2013)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018

© 2018 Talia Mestel Fox. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or

hereafter created.

Author________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning

May 24, 2018 Certified by____________________________________________________________________

Assistant Professor Gabriella Y. Carolini Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by___________________________________________________________________

Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell

Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Co-Opting Sustainabilities: The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’s National Solid Waste Policy

By Talia Mestel Fox

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning

Abstract

Growing levels of global solid waste production implore society to identify the actors

responsible for preventing, reducing, and disposing of wasted material in a sustainable manner. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are policy frameworks that hold accountable the manufacturers of goods that create post-consumer waste. National and state governments typically prescribe EPR through market mechanisms,

performance standards, and disclosure requirements. CSR relies largely on voluntary programs that international bodies and corporations themselves establish to prevent or remediate socially and environmentally destructive behaviors. Responding to a paucity of research regarding adaptations of EPR to the global South, this thesis traces the origins and outcomes of the 2010 National Solid Waste Policy of Brazil (PNRS), which mandates EPR. I focus on a provision of the PNRS that prescribes CSR in fulfillment of EPR through partnerships between corporations and cooperatives of wastepickers: collectively-organized, self-employed individuals who separate, sort, and sell recyclable materials. Guiding this inquiry is a question regarding the implications of the interactions between the transnational sustainability frameworks of

corporations and laborers. Through an analysis of the histories and realities of these interactions, I interrogate the dynamics that shape the structures of CSR programs and their evaluative tools under the PNRS, from the perspective of wastepickers. I assert that these CSR programs, while sources of technical and financial support for wastepickers, by design cannot actualize the concept of EPR because they fail to remunerate wastepickers as market actors. Furthermore, I demonstrate that by controlling the processes that assign and assess responsibility for waste management in Brazil, corporations have co-opted a sustainability discourse of labor that is intended to advance wastepickers’ own fight for fair pay, rights, and recognition.

Key Words

Waste management; municipal solid waste; sustainability; extended producer responsibility, Brazil, waste picker; corporate social responsibility, labor, evidence-based policy.

Thesis Supervisor: Gabriella Carolini Title: Assistant Professor

Acknowledgments

Quando a gente põe o pé no lixo, a gente não sai nunca mais. “Once we stick a foot in waste, we never leave again.”

I am enthusiastically accepting of the fact that this popular saying among Brazilian waste researchers and advocates may in fact apply to me. I never would have stepped into any of this, however, if not for the encouragement and support of the many people mentioned and

unmentioned on this page. Thank you:

to Gabriella Carolini, an advisor, teacher, and mentor, for your thoughtful and comprehensive guidance, whole-hearted commitment to students’ development, and humanity, which enhances learning by grounding it in the experience of living; to Libby McDonald, for imparting on me your passion for the humans of waste, opening the doors that would lead to this research in the fall of 2016, boldly throwing me into the challenge of fieldwork; and trusting me to navigate my way through the political, social, and linguistic complexities that accompany it; to Sonia Maria Dias and Ana Carolina Ogando, for receiving me in Belo Horizonte and orienting me to the struggles and triumphs of informal economies in Brazil, facilitating crucial conversations, and reminding me to give back to the communities that give to us;

to Guilherme Fonseca, for entertaining my many requests to explain the solidarity economy, wastepicker networks, rotating funds, and copious gíria; to the staff of INSEA, for your insights into the role of the advocate researcher in Brazil’s waste system, and for letting me camp out in your offices intermittently; to the staff of Novo Ciclo, for accompanying a person you had never met on long drives to various cities, sharing your honest opinions, and pursuing improvements to lives through your work; to Gina Rizpah Besen, for a single illuminating conversation that helped frame my critique; to the many individuals I spoke with, particularly wastepickers, for sharing your wisdom, time, trust, patience with my Portuguese, and unwavering spirit; to my friends in Belo Horizonte, for welcoming me into your circles and exploring the city with me, and showing me that Brazil could feel like more than a thing that happened to me that one time. to Rosabelli Coelho-Keyssar, for cheerful conversations in Portuguese and the flexibility that enabled me to craft the ideal summer for an indecisive mind; to MISTI Brazil and the PKG Public Service Center, for funding my travel to Brazil; to Kate Mytty and Jenny Hiser, waste gurus and instructors of the fall 2016 iteration of D-Lab Waste, for providing my introduction to the multifaceted world of waste through the eyes of planners and enabling me to connect it to my love for Brazil; to Foster Brown and Vera Reis, for solidifying my love for Brazil, for inviting me into your lives in a remote Amazonian city in the center of the universe in 2013; for building a home that became my sanctuary; for showing me how to confront the jaguars of life; and for preparing me to take care of others;

to my fellow DUSPers, for contributing to many transformative and joyful months; to Rebecca Margolies, for your loyalty and wit, and for inspiring me to act on my values; to Tamara Knox, Laura Krull, and Martin the parrot, for creating a “nice soft home with good friends” that rejuvenates, comforts, and lifts me; to my family—Mom, Dad, Leora, Sam, Ari, and Ned, for staying close and carrying me, always; and to Eric Huntley, for a growing list of reasons.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract ... 2

Key Words ... 2

Acknowledgments ... 3

Acronyms ... 6

1. INTRODUCTION: DREAMS, DEMANDS, AND DOUBTS... 9

Multiplicative Sustainabilities ... 10

Research Goals and Questions ... 11

Thesis Statement ... 12

Organization... 12

Waste Governance: Who is Responsible? ... 13

Wastepickers ... 13

Municipalities ... 15

Corporations ... 16

Case Selection ... 18

Analytical Framework: Transnational Alliances ... 18

Methodology ... 20

Limitations ... 23

2. ALLIED SUSTAINABILITIES ... 25

Labor and Sustainability ... 26

CSR and Sustainability ... 27

Constructed Sustainabilities ... 30

3. CONTEXT FOR BRAZIL’S WASTE REGIME ... 33

Transnational Sustainability Movements in Brazil ... 34

Labor in Brazil ... 34

CSR in Brazil ... 36

Waste in Brazil: Wastepickers ... 38

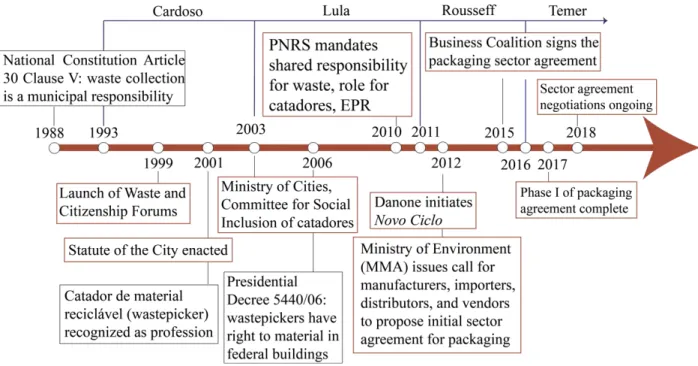

The National Solid Waste Policy ... 40

The Packaging Sector Agreement ... 41

4. PNRS POLITICS AND PRESCRIPTIONS ... 46

Lulalaying the Groundwork ... 47

Improving the Dialogue ... 49

Businesses In, Cities Out ... 50

Developing the Packaging Sector Agreement ... 52

Motivations for Municipal Exclusion ... 54

Bounding What Binds ... 56

5. PACKAGING SECTOR AGREEMENT ORIGINS AND OUTCOMES ... 60

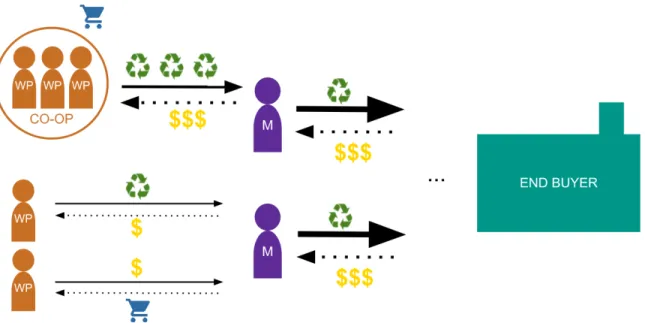

From Social Responsibility to Reverse Logistics ... 60

Sharing, or Shirking, Responsibility? ... 64

Data, Data, Data ... 65

Value Deprived, Derived, and Contrived ... 68

In Service of Sustainability? CSR Program Impacts ... 71

Danone: Novo Ciclo ... 72

Achievements, Aspirations, Allegations ... 74

6. “A LABORATORY OF CONFRONTATION” ... 85

EPRs…and Are Nots ... 85

Co-Opted Sustainabilities ... 87

Final Thoughts, Further Inquiry ... 89

Appendix 1: List of Transcribed Interviews (June-July 2017) ... 91

Appendix 2: List of Meetings/Rallies Attended (June-July 2017) ... 92

Appendix 3: List of Novo Ciclo Interviews/Meetings (January 2017) ... 93

Acronyms

ABIHPEC Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Higiene Pessoal, Perfumaria e Cosméticos (Brazilian Association of Personal Hygiene, Perfumery, and Cosmetics Industries) ABRE Associação Brasileira de Embalagem (Brazilian Packaging Association)

ANAP Associação Nacional dos Aparistas de Papel (National Association of Paper Wholesalers)

ANCAT Associação Nacional dos Carroceiros e Catadores de Materiais Recicláveis (National Association of Carters and Collectors of Recyclable Material) CBO Classificação Brasileira de Ocupações (Brazilian Occupation Classification) CDM Kyoto Protocol Clean Development Mechanism

CEMPRE Compromisso Empresarial para Reciclagem (Corporate Recycling Commitment) CIISC Comitê Interministerial de Inclusão Social de Catadores (Inter-ministerial

Committee for Social Inclusion of Wastepickers)

CMRR Centro Mineiro de Referência em Resíduos (Reference Center on Solid Waste of Minas Gerais)

CNC Confederação Nacional do Comércio de Bens, Serviços e Turismo (National Confederation of the Trades of Goods, Services, and Tourism)

CNPJ Cadastro Nacional da Pessoa Jurídica (National Registry of Legal Entities) CPR Collective producer responsibility

CSR Corporate social responsibility

CUT Central Única dos Trabalhadores (Unified Workers’ Central) DfE Design for environment

EJ Environmental justice

EU European Union

FNRU Fórum Nacional de Reforma Urbana (National Forum for Urban Reform) GRI Global Reporting Initiative

GTA Grupo Técnico de Assessoramento (Technical Support Group) HDPE High density polyethylene

IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)

IDB Inter-American Development Bank IMF International Monetary Fund

INESFA Instituto Nacional das Empresas de Preparação de Sucata Não Ferrosa e de Ferro e Aço (National Institute of Non-Ferrous Scrap and Iron and Steel Processors)

INSEA Instituto Nenuca de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (Nenuca Institute for Sustainable Development)

IPEA Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada (Institute of Applied Economic Research)

IPR Individual producer responsibility

ISO International Organization for Standardization LDPE Low density polyethylene

MBO Membership-based organization (wastepicker cooperatives and associations) MDS Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome (Ministry of Social

Development and Fight Against Hunger)

MISTI Massachusetts Institute of Technology International Science and Technology Initiatives

MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MMA Ministério do Meio Ambiente (Ministry of Environment) MNC Multinational corporation

MNCR Movimento Nacional dos Catadores e Catadoras de Materiais Recicláveis (National Movement of Collectors of Recyclable Material)

MNRU Movimento Nacional de Reforma Urbana (National Movement for Urban Reform)

MPF Ministério Público Federal (Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office)

MPFSP Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo (Public Prosecutor’s Office of the State of São Paulo)

MST Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Rural Workers’ Movement)

MSW Municipal solid waste

MTE Ministério do Trabalho e Emprego (Ministry of Work and Employment) NGO Non-governmental organization

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OPNRS Observatório da Política Nacional de Resíduos Sólidos (Observatory of the National Solid Waste Policy)

ORIS Observatório da Reciclagem Inclusiva e Solidária (Observatory for Inclusive Solidary Recycling)

PP Polypropylene

PS Polystyrene

PVC Polyvinyl chloride

PKG MIT Priscilla King Gray Public Service Center

PNRS Política Nacional de Resíduos Sólidos (National Solid Waste Policy) PPP Public private partnership

PSDB Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Brazilian Social Democracy Party) PT Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party)

SENAES Secretaria Nacional de Economia Solidária (Secretariat of Solidarity Economy) SINIR Sistema Nacional de Informações Sobre a Gestão dos Resíduos Sólidos (National

Information System for Waste Management)

SLU Superintendência de Limpeza Urbana (Superintendency of Urban Cleaning of Belo Horizonte)

TSMO Transnational social movement organization

UN United Nations

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

WIEGO Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing WSF World Social Forum

1. INTRODUCTION: DREAMS, DEMANDS, AND DOUBTS

In 2003, newly elected President of Brazil, Luis Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula”), celebrated Christmas with wastepickers of the Baixada do Glicério neighborhood, historically home to the working poor and homeless populations of São Paulo. The festivities were imbued with

expectation. The symbolic and commemorative gesture, to which Lula would commit each of the eight Christmases of his presidency, was a deliberate nod to the laborers who had carried him and the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) to power. Lula had made promises, specifically to leadership of the National Commission of the Movimento Nacional dos Catadores e Catadoras de Materiais Recicláveis (National Movement of Collectors of Recyclable Material, MNCR), that could provide continuity to the wastepickers’ decades-long fight for basic rights, recognition, and political representation.

“The National Commission cannot go easy on us,” he said. “You have to hold the government accountable, because if not, it will put things off and put things off…you need to hold it accountable, so that we can do that which is the dream and great demand of yours” (MNCR 2011).

Nearly 14 years later, with their most powerful advocate sentenced to ten years in prison for presumed money laundering involving multinational corporate actors (Londoño 2017), Brazil’s wastepickers are still fighting.

***

I did not fully understand the relevance of these histories when I arrived in São Paulo in January of 2017, funded by multinational corporation (MNC) Danone to research a potential mobile phone application to improve communication among wastepicker cooperatives and associations in the southeastern states of Brazil. Overwhelmed with the deluge of new waste-related concepts and vocabulary that dozens of wastepickers and Danone staff generously shared, I fumbled my way through hours of interviews in rusty Portuguese. Among the conversations and questions

about recycling operations, cooperative structures, collection routes, finances, and technologies, I found myself questioning the circumstances of my visit.

I knew that corporate social responsibility (CSR) could encourage private actors to channel the rhetoric, if not the action, of other movements that unite social, economic, and environmental causes under the sustainability umbrella. The result of environmental sustainability as a component of CSR can be a phenomenon popularly referred to as “greenwash” (Tokar 1997). Under this framework, corporations make amends for harmful actions with commitments to “sustainable jobs,” resource conservation, and proper waste treatment and disposal (Aluchna 2017), without fundamentally altering destructive business models or reaching supposed beneficiaries (Ashman 2001). In the context of waste, these grievances feel particularly

hypocritical: the occupational health and safety concerns associated with factory effluents, waste disposal, and facilities siting are central to the histories of the labor and environmental justice (EJ) movements (Obach 2004; Bullard 2007).

It was from these perspectives that I doubted the motivations of corporate entities working with wastepickers in Brazil. Not only did Danone’s efforts transcend the typical CSR program, they also seemed to be supporting wastepickers, effectively preserving their autonomy. So why was a multinational like Danone bothering to strengthen networks of waste laborers in Brazil?

Wastepickers finally had a seat at the table, but from where they were sitting, what was in it for the corporations?

Multiplicative Sustainabilities

The proliferation of the concept of global sustainability provokes shifting responsibilities for the natural, social, and built environments. In the past three decades, the practice and performance of sustainability has evolved from “[meeting] the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED 1987, l. 27)” to implicate new actions, actors, and sectors. Indeed, the community to which those needs and those generations belong can vastly change what sustainability means. Because they explicitly invoke

environment, economy, and civil society (Munasinghe 1993), sustainability efforts provide space for alliance-building among seemingly disparate movements. These alliances, in turn, may grant leverage to transnational movements working to build momentum toward place-based political or social goals (Smith and Bandy 2005).

In Brazil, for example, the PT’s rise followed the party’s successful embrace of both its labor origins and businesses’ inclinations toward socially and environmentally sustainable practices at the end of the 20th century (Peña and Davies 2014). This strategy permeated Lula’s programs and policies, including Brazil’s 2010 Política Nacional de Resíduos Sólidos (National Solid Waste Policy, PNRS). The PNRS demands that all members of society—corporations,

consumers, government officials, and waste workers alike—contribute to waste management, a burden that historically has not been shared equally. Because of a decades-long history of power shifts on Brazil’s political stage, the country’s approach to waste management is an opportunity to interrogate the provisions of the PNRS that attempt to redistribute these burdens.

I offer labor’s account of Brazil’s ongoing attempts to hold corporations responsible for the disposal of post-consumer waste from their products and packaging. The argument that simultaneously guides and has emerged from this narrative is a product of my journey to understand wastepickers’ experience of the policy processes and sustainability programs designed to support them.

Research Goals and Questions

The goal of this inquiry is therefore to represent wastepickers’ perspectives on the

implementation of participatory mechanisms embedded within the provision of the PNRS that mandates a sustainability concept known as extended producer responsibility (EPR). These mechanisms include the bidding and negotiations processes surrounding an agreement among corporate producers of disposable packaging, and those corporations’ subsequent adaptation of CSR programs in order to fulfill EPR. While these CSR programs provide significant benefits to wastepickers, the programs also benefit the corporations that designed them, necessarily so.

In the context of these processes, laborers and corporations represent transnational movements that have organized historically around conceptions of sustainability in order to achieve

particular goals. My research questions evolved, along with my understanding of the complexity of the interactions between these movements that the PNRS provokes. The following questions ultimately guided my narrative and critique:

• Under what conditions does the grounded interaction of transnational movements enable these movements to leverage particular sustainability frameworks?

• Where this leveraging occurs, whose framework legislates sustainability in practice—that of labor, or that of corporations—and what are the consequences for the labor movement, specifically, with regard to achievement of its goals?

Thesis Statement

I argue that, from the perspective of wastepickers, the participatory mechanisms that the PNRS prescribes have enabled corporations to co-opt and benefit from the sustainability framework that the labor movement itself has constructed for decades. I contend that this co-optation weakens wastepickers’ efforts, both to earn fair compensation for their work, and to hold corporations and government accountable through democratic processes.

Organization

In the remaining pages of this introduction, I review the relevant sectors historically responsible for waste production, disposal, and reuse. I expand upon the importance of my inquiry for its illumination of Brazil as a case study in the adaptation of EPR to the global South. I then discuss my analytical framework, methodology, and limitations.

In Chapter Two, I expand upon the motivations for alliances that the CSR and labor movements forge with one another and with the environmental movement. I also explore the construction of

sustainability and other transnational movement frameworks. In Chapter Three, I situate the discussion of alliance-building within the volatile politics of 20th century Brazil. Chapter Four introduces the PNRS in the context of Brazil’s waste management history. Finally, in Chapters Five and Six, I offer an analysis and a critique of the development of the PNRS and resulting processes, concluding with opportunities for further inquiry.

Waste Governance: Who is Responsible?1

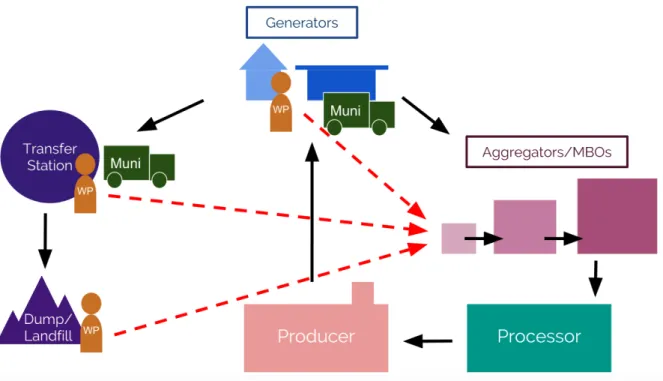

The following groups feature prominently in this research’s exploration of the PNRS and its associated regulatory processes: wastepickers, municipalities, and corporations.

Wastepickers

Wastepickers assume primary responsibility for the recycling of valuable material streams in many cities around the world, although they are not often acknowledged or compensated for their work (Dias and Samson 2016). An estimated 80% of waste workers are categorized as “informal,” or unregulated (International Labour Office 2013). While these waste workers are the same protagonists I will reference continually, I will not necessarily refer to wastepickers representing the informal sector. The activities of wastepickers, particularly those interacting with corporations under the PNRS in Brazil, often blur the formal-informal dichotomy. For the purposes of this research, I use a definition of wastepickers that encompasses both formal and informal: self-employed individuals who, through the collection, sorting, resale, and repurposing of discarded materials, earn an income while contributing to local economies and reducing solid waste. Additional benefits to society include improved sanitation and public health and reduced costs to municipalities through diversion of large quantities of materials (WIEGO 2013).

In recent years, wastepickers have achieved rights through self-organization, activism, and lobbying for regulatory change (WIEGO 2011a). The global community of wastepickers,

1 This chapter adapts sections of a final paper submitted by the author for course 11.475, Navigating the Politics of Water and Sanitation Planning, in the spring of 2017 in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

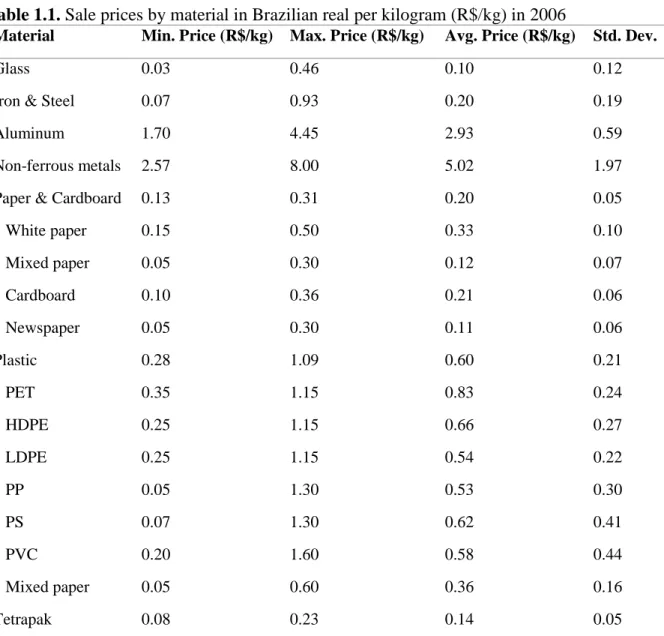

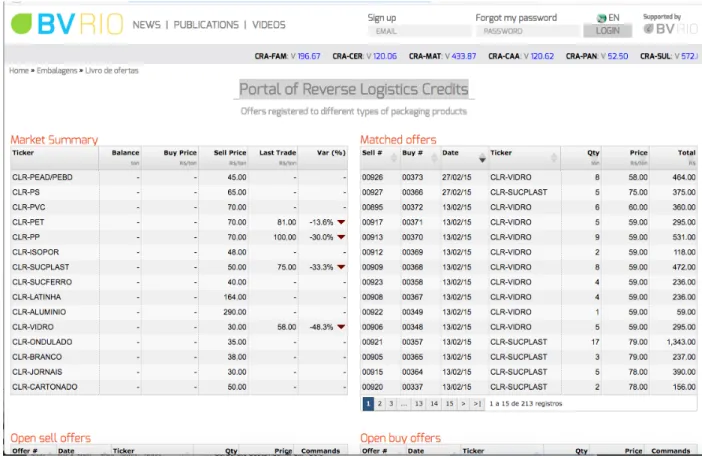

however, still suffers from a lack of resources and infrastructure to agglomerate and handle waste collection and sorting; occupational health risks; limited to no access to the market value of materials; dependence on middlemen or intermediaries who take advantage of information asymmetries to earn higher profits; and social stigma, among other challenges (Wilson, Velis, and Cheeseman 2006). Because wastepickers earn incomes in most places from the daily sale of materials, for example, fluctuating material markets (see Table 1.1) and availability of material streams directly impact the liquid capital available to them for basic living expenses.

Table 1.1. Sale prices by material in Brazilian real per kilogram (R$/kg) in 2006

Material Min. Price (R$/kg) Max. Price (R$/kg) Avg. Price (R$/kg) Std. Dev.

Glass 0.03 0.46 0.10 0.12

Iron & Steel 0.07 0.93 0.20 0.19

Aluminum 1.70 4.45 2.93 0.59

Non-ferrous metals 2.57 8.00 5.02 1.97

Paper & Cardboard 0.13 0.31 0.20 0.05

White paper 0.15 0.50 0.33 0.10 Mixed paper 0.05 0.30 0.12 0.07 Cardboard 0.10 0.36 0.21 0.06 Newspaper 0.05 0.30 0.11 0.06 Plastic 0.28 1.09 0.60 0.21 PET 0.35 1.15 0.83 0.24 HDPE 0.25 1.15 0.66 0.27 LDPE 0.25 1.15 0.54 0.22 PP 0.05 1.30 0.53 0.30 PS 0.07 1.30 0.62 0.41 PVC 0.20 1.60 0.58 0.44 Mixed paper 0.05 0.60 0.36 0.16 Tetrapak 0.08 0.23 0.14 0.05

Glass, for example, an abundant product that at once is bulky and dangerous to process and offers relatively few economic and environmental benefits, has low market value compared to materials like aluminum (S.P. Silva, Goes, and Alvarez 2013). Within the categories of plastics and paper, a variety of sub-categories of material results in a wide range of prices (DIRUR 2010).

Furthermore, many policies are designed explicitly to eliminate unregulated or arguably illegitimate actions in waste management, barring wastepickers’ access to materials or waste collection facilities, with the justification that informality is counterproductive to the

modernization and job potential of waste systems. Wilson et al. argue that such policies attack systems that can in fact be quite efficient and provide the sole means of subsistence for

populations that the formal sector excludes, including individuals with physical disabilities or little to no education. These marginalized actors seize the opportunity to invent alternative systems for waste collection and recycling, often because publicly-funded municipal solid waste (MSW) management systems, developed in the urban hubs of the industrial revolution, may fall short in emerging economies (Wilson, Velis, and Cheeseman 2006).

Municipalities

Municipal-scale, organized infrastructure for waste removal (as it is commonly understood today) arose in response to concerns around health and sanitation in mid-late 19th century industrial cities (Louis 2004). Municipalities introduced water provision, sanitation services, and later, refuse collection, either directly or through contracts with private entities. The expectation of public sector responsibility for waste management has persisted in many cities for the last century, with varying degrees of private sector involvement.

With the proliferation of disposable containers and packages in the mid-to-late 20th century, the burden on municipalities and taxpayers for removing waste from mass consumption increased dramatically. While cities faced costs for waste disposal of approximately 300 million dollars per year in 1940, by 1960, that statistic had increased to one billion dollars, and by 1980, four billion dollars (Melosi 1981). The influx of paper, plastics, and other synthetic goods during this time exemplifies the dynamic nature of waste stream composition. Since the 1970s, however, this

influx has also provoked questions of responsibility for the final disposal of materials derived from commercial products.

Today, many cities have instituted recycling programs in response to the changing makeup of waste, requiring source-separation by the residential sector. Some of these programs, however, are the result of corporate lobbyists’ efforts to oppose regulations that more directly target the original source of these products (MacBride 2012): the corporations themselves.

Corporations

Corporate waste consciousness generally concerns resource conservation. Several practices on the part of companies may contribute to waste-related CSR efforts, but I choose to focus on EPR, also referred to as end-of-life management or product stewardship, because of its direct relevance to my analysis. EPR addresses the post-consumer waste stemming from the production and sale of manufactured goods (OECD 2001). EPR attributes responsibility for the final disposal of packaging and other discarded materials to the manufacturer, rather than to the consumers that purchase products or to the municipalities that collect those products through organized waste management systems (and the taxpayers that finance them). This idea echoes the concept of cradle to grave product management, often part of a circular or closed-loop economy model that promotes reuse and recycling (Geissdoerfer et al. 2017).

Various implementation structures for EPR exist (see Box 1.1). Some invoke responsibility through end-of-life management funds to which manufacturers and producers contribute, while others require product takeback by individual manufacturers (Kaffine and O’Reilly 2013). As such, the literature distinguishes between individual producer responsibility (IPR) and collective producer responsibility (CPR) schemes (OECD 2015). In the first case, single producers must meet certain quotas or are charged fees to encourage closed-loop production and vertical integration. In the second case, producers within a single industry respond to take-back

requirements by establishing or contracting producer responsibility organizations (PROs). PROs coordinate the logistics of meeting the collective quotas of the producers that contract them, as well as all communication with the various entities involved in recycling processes for a particular product or group of products (Mayers and Butler 2013).

The majority of EPR policies and schemes address end-of-life procedures for electronic waste and automobiles, largely in North America and the European Union (EU) (OECD 2016). These policies have been criticized for failing to promote behavior change, allowing companies instead to support existing systems for recycling (Lifset, Atasu, and Tojo 2013; OECD 2004).

Furthermore, translating EPR policies that evolved in developed economies to the developing context, where waste systems may differ significantly, presents significant socio-cultural, political, and economic challenges (Tong and Yan 2013).

Indeed, given that the basis for EPR policies is those established in the EU and other OECD nations, simply replicating policies may not be appropriate for distinct contexts (Demajorovic et al. 2014). EPR policies see more involvement from larger companies, which suggests that EPR may work to the disadvantage of smaller companies unable to handle the costs (Neto and Van Wassenhove 2013). Finally, EPR policies may not in fact be necessary in countries where the value of waste is already captured by unregulated players like “backyard recyclers” in India (Manomaivibool 2009).

Box 1.1. EPR Categories

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) Extended Producer Responsibility: Updated Guidance for Efficient Waste Management report identifies four main categories of EPR policies:

1. product take-back requirements: collection quotas for producers, often achieved through consumer product return at designated recycling stations;

2. economic and market-based instruments: a range of taxes, fees, subsidies, refunds, and other monetary incentives levied on consumers or on producers to encourage the reuse of post-consumer materials over virgin materials in the design and production phases; 3. regulations and performance standards: mandated industry or jurisdiction-level targets

related to the materials used in production, like “minimum recycled content”; and 4. information-based instruments: public disclosure or transparency requirements

regarding manufacturing processes or product components, often achieved through labels or other education campaigns.

These policies are not mutually exclusive; in combination, in fact, they can provide further incentives for more efficient and less wasteful product design (referred to as design for environment, or DfE), resource conservation, and more equitably distributed disposal costs, in addition to other environmental, social, and economic benefits (OECD 2016).

Examples of collaboration between private and unregulated actors do exist, notably in Colombia, where private companies have organized to form a nonprofit membership organization that works to promote more socially responsible recycling practices (WIEGO 2016). These channels of collaboration are seldom made explicit in the EPR laws themselves.

Case Selection

The PNRS contains an EPR provision that not only recognizes the role of wastepickers and wastepicker cooperatives; it also requires corporations to engage with their existing efforts to collect, sort, and sell recyclable material. This framework for EPR under the PNRS is the product of political and historical conditions in Brazil that have reinforced a dynamic political economy fluctuating between elite and popular control of policy development and implementation. By exploring the individual and organizational alliances that shaped the law, I respond to the paucity of research on models for adapting EPR to non-OECD countries.

I present a narrative of the formation of the PNRS and its resulting policy processes through the eyes of the actors involved, with the goal of understanding the consequences of the ways in which their conceptualizations of sustainability ascribe roles and responsibilities. I focused my study in the city of Belo Horizonte, capital of the state of Minas Gerais, because of its historic recognition of wastepickers through policy mechanisms that provide technical and financial support, upon which I elaborate in Chapter 3. First, I introduce the theoretical lenses that inform this narrative.

Analytical Framework: Transnational Alliances

Through the introduction of shared responsibility for waste management, the PNRS provokes interactions among political, corporate, and popular groups. These groups’ development of sustainability frameworks reproduces a phenomenon of national and transnational movement-building at the intersection of social causes (Smith and Bandy 2005).

International environmental governance bodies, policy-makers, and scholars promote the green economy concept, for example, emphasizing the economic pillar of sustainable development in order to respond to the presumed economy-environment dichotomy2 in a post-recession world (Ehresman and Okereke 2015; Geissdoerfer et al. 2017). Another example, the circular economy framework for sustainability, emphasizes natural resource conservation by questioning the traditionally linear model of consumption (Geissdoerfer et al. 2017). Both of these sustainability concepts also address the labor movement’s concern for occupational health and safety, fair pay, and inclusion (Obach 2004).

In specific instances, the labor movement’s own uptake of environmental issues has allowed it to forge partnerships with major international environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) via alliances with the EJ movement (itself the union of six separate social movements), which explicitly confronts the systemic discrimination that causes low-income and minority populations to bear the burden of environmental harms (Faber 2005). Having undergone a related awakening, the environmental movement has become more anthropocentric, as concepts like just sustainability introduce equity more explicitly into environmental concerns (Agyeman and Evans 2004) and conversations around resilience reference the disproportionate impacts of climate change (Schlosberg and Collins 2014).

For the CSR movement, motivations for assuming a sustainable approach to business include the desire to comply with international standards, avoid legal liability for accidents, appease

shareholders, and reduce costs (Berry and Rondinelli 1998). A mere discourse of sustainability, on the other hand, can allow businesses simply to appear compliant, achieving the desired outcomes while avoiding the associated efforts (Tokar 1997). Whether or not sustainability is a legitimate goal, these examples demonstrate that many strategic reasons exist for movements to craft their own versions of sustainability with both distinct and shared elements.

I am most interested in theories that suggest that under specific political, social, and economic conditions in the global South, the definitions of sustainability that these movements create

2 In his 1996 work Beyond Growth, Daly contests the idea that environmental protection threatens economic growth (Daly 1996).

position them on opposite sides of a power struggle. Faber, for example, asserts that

sustainability offers an additional avenue for organized labor to oppose corporate employers that exploit a discourse they do not act on (Faber 2005). Cole contends that corporations’ blurring of sustainability and CSR programs under the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) threatens civil society’s initial goals to hold corporations accountable for their

environmentally and socially damaging behavior (Cole 2012).

These ideas echo concerns regarding the privatization of waste and sanitation systems in the global South. Critics assert that the financialization of these systems through international lenders and contracts with MNCs does not fix problems of service provision; rather, it distracts from the underlying issues that lead to poor service provision in the first place: lack of political will, corruption, and dismissal of small-scale service providers (Budds and McGranahan 2003). Local, participatory solutions to infrastructure funding in the global South may be little more than “balm-like reforms” in the face of national policy (Carolini 2017), though we can simultaneously acknowledge their transformational capacity. To Carolini’s suggestion, we should “examine how national economic and local political ‘development’ rationales interact on the ground” (Carolini 2017, 131) to understand further why attempts at inclusive sustainable development are not bearing the fruits we expect.

The case I explore in Brazil presents an opportunity to draw insights from the intersection of the two movements, scales (local, national, and global), and various theories in question, in the face of an ambitious and contested policy process that attempts at once to address environmental problems, corporate responsibility, equity and labor issues, and waste management funding.

Methodology

This thesis focuses on the implementation of the PNRS in a particular moment in time—2012 through 2017—while placing the law in the context of Brazil’s political history. I use a single-unit case study approach, the single-unit being the EPR provision within the PNRS, which I understand to be one of a larger class of EPR policies. The rationale for the single-unit case study approach

is its usefulness for achieving analytical depth, identifying causal mechanisms, and constructing theories in order to fill gaps in existing research (Gerring 2004; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

The qualitative methods I employ are grounded in an idea of meaning-making that falls slightly left of center on the spectrum of subjective to objective ontologies. I take a view of the world in which “knowledge, understanding, and explanations of social affairs must take account of how social order is fashioned by human beings in ways that are meaningful to them,” (Morgan and Smircich 1980). Simultaneously, I acknowledge the existence of like activities” and “rule-like actions” that operate according to patterns that individuals and groups define (Morgan and Smircich 1980, 494). Therefore, while I considered incorporating quantitative analysis into my research to assess the impacts of particular CSR programs, I remained skeptical, not of the ability of data itself to represent a reality, but rather of the potential for the actors defining what counts as evidence to confound my conclusions in this particular circumstance. Fittingly, this thesis demonstrates the dangers of relying too heavily on a particular type of data as an objective means of measuring outcomes in the context of a policy.

Intuition, prior experience working and living in Brazil, and discussions with colleagues in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Department of Urban Studies and Planning and MIT D-Lab encouraged me to adopt techniques that Leech borrows from the fields of

anthropology and journalism (Leech 2002). Under this framework, the researcher builds a rapport with the interviewee, intentionally ordering a mix of narrow to general “grand tour” (Spradley 1979) questions. Upon gaining a basic understanding of an interviewee’s positions, where appropriate, I introduced arguably presumptive questions, framed cautiously and deliberately in ways that reflected my own opinions and curiosities. Despite claims that these types of questions draw out false perspectives, these questions may not be categorically

problematic; the acknowledgment of my own positionality facilitates an approach in which the individuals with whom I am conversing are free to entertain opinions and doubts regarding the nature of my interest in the information they are providing (Pawson 1996).

The primary sources for my research were 16 semi-structured interviews with representatives of wastepicker cooperatives and associations, municipal and state government, industry, academia,

private foundations, and nonprofits involved in work related to waste during seven weeks in June and July of 2017 (see Appendix 1 for a complete list of locations and dates). I observed

participants of several meetings and events (see Appendix 2), and had follow-up conversations and email exchanges with researchers closely following the process, particularly members of the Observatory of the PNRS (OPNRS) and the Observatory for Inclusive Solidary Recycling (ORIS), based in São Paulo and Belo Horizonte, Brazil, respectively.

The majority of interviews occurred in the city of Belo Horizonte, with the exception of four interviews I conducted through Skype or WhatsApp with individuals residing in the cities of Poços de Caldas, São Paulo, and Porto Alegre. The MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) Brazil program funded my travel to Belo Horizonte for an internship with the nonprofit Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), whose staff helped to connect me with potential interviewees. Due to initially limited access to experts on the somewhat controversial topic of the PNRS’s EPR processes, as well as concerns around trust that socially vulnerable populations like wastepickers may have toward outsiders, I largely took a snowball approach to selecting interviewees (Atkinson and Flint 2001).

I asked consent to record conversations, take handwritten notes of individual conversations, and reference interviewees in my written product. I do not identify interviewees by name in this document, rather referring to them by their sector or assigned number. I conducted interviews primarily in Portuguese. I used the transcription services of Chico Araujo, after which point I interpreted the Portuguese transcripts. During my analysis stage, I identified themes into which I slotted conversation segments and triangulated interviews with literature, reports, and news articles and other popular sources.

Importantly, my first foray into waste-related CSR projects in Brazil was through work I

performed with Danone. Through an initiative out of the Inclusive Recycling Working Group at MIT D-Lab, I became involved with a project to assess the potential efficacy of a mobile

application to aid networks of wastepicker cooperatives. I traveled to Brazil for approximately three weeks in January of 2017 for this purpose, funded by Danone and MIT’s Priscilla King Gray (PKG) Public Service Center. During this trip, I interviewed 34 members and leaders of

eight wastepicker cooperatives and associations in southeast Brazil (see Appendix 3). These visits provided me with a crucial understanding of waste systems in Brazil, wastepicker cooperative and association functions and leadership, and challenges and successes within the wastepicker community. The cooperatives I visited were all current or prospective participants of Danone’s Novo Ciclo program, which addresses Brazil’s PNRS. My visits lent me insight into the scope of the project and relationships between project staff and wastepickers. Importantly, they provided a crucial grounding for the fieldwork I would perform the following summer for my thesis research.

Limitations

It helps me to think of this thesis as a section, if a section of a process were possible. Just as I might choose to take a section that best represents a unique geography, neighborhood, or street, I carefully chose the particular site, angle, and length of this section in order to represent the perspective of organized wastepickers. To that end, while this document captures perspectives of many actors involved—nonprofits, corporations, academics, government officials, wastepickers, and others—my data primarily reflect wastepickers’ understanding of the situation, rather than corporations’. I did not speak with a wide range of corporate actors and government officials involved at higher levels of negotiations, although I did speak to several leaders of the MNCR involved in those same negotiations. On a related note, the wastepickers I interviewed in June and July of 2017 are all active leaders of the MNCR, who spend less time sorting and processing recyclables than many of the wastepickers I interviewed in January.

I purposefully do not cite interviews that I conducted while working with Danone and partners in January, however, for two reasons. The first is the uncomfortable nature of a research inquiry that adopts a critical perspective on the company that directly supported its origins. Components of this thesis, in particular those that discuss the impact of the Novo Ciclo program, necessarily channel information I gathered during this time period. Moreover, having established

relationships and formed a mental picture of the landscape, I was able to ask more targeted questions and access key interviewees upon my return to Brazil during the summer.

The second is the recognition of my own positionality as a result of time conducting research with Danone in January. Novo Ciclo was my first introduction to CSR programs under the PNRS. Danone controlled my itinerary—the cities and cooperatives I visited and, to an extent, the individuals I consulted. The interviewees understood that despite being introduced as an independent student researcher from MIT, I was affiliated with Danone. Because the information I accumulated during this time was orchestrated, I acknowledge its potential to impact the results of this thesis.

Importantly, while my command of Portuguese is near fluent, having spent over a year living and doing research in Brazil for prior academic and professional pursuits (operating entirely in

Portuguese after studying intensively), Portuguese is not my native language. I acknowledge that I may have misinterpreted interviewees’ words on occasion. I have done my best to represent them accurately and confirm with English-speaking Brazilians familiar with the PNRS proceedings, where possible.

I wish also to recognize the limitations of perspective that accompany a literature review

comprising largely native English speakers, Western thought-leaders, and male voices (Mott and Cockayne 2017). I endeavored to achieve a more balanced representation of women and Latin American researchers, as well as scholars from the global South whose valuable academic work often goes uncited.

A final thought for my readers: While I remain critical of CSR efforts in Brazil and elsewhere, the goal of this research is not to vilify private actors working to implement the PNRS. I recognize that this work is young, messy, and courageous. Rather, in light of global solid waste production approaching 2.2 billion metric tons by 2025 (Bhada-Tata and Hoornweg 2012), I hope to inform and to improve future iterations of these process in Brazil; to encourage context-appropriate adaptations of waste management policies, particularly in the global South; and to push society to illuminate, unpack, and confront the formidable struggle that is identifying the actors responsible for preventing, transporting, financing, and disposing of waste.

2. ALLIED SUSTAINABILITIES

The formation of alliances within and among related causes is well documented in the literature on global change-making and social mobilization (Khagram, Riker, and Sikkink 2002; Keck and Sikkink 1998; Smith, Chatfield, and Pagnucco 1997). Alliances emerge in the form of networks, coalitions, and movements—in order of increasing degrees of formality, organization, and temporal duration—to unite actors at local, national, and international levels toward a common goal (Smith and Bandy 2005). Transnational social movement organizations (TSMOs) are entities that emerge out of the network and coalition-building processes to further campaigns or change processes across political borders (Smith and Bandy 2005). TSMOs can promote

improved transparency of private or public decision-making processes or provoke governments to take action on social issues (Smith, Pagnucco, and Chatfield 1997).

Environmental TSMOs in particular have helped to introduce issues like climate change and biodiversity on national and international agendas through organized participation in conferences or in the construction of formal commitments (Smith 1997). With the support of advocates and social groups that TSMOs often comprise, transnational rule-making bodies hold their

subscribers to sustainability commitments, like the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI’s) Sustainability Reporting Guidelines or the Forest Stewardship Council’s certification process (Dingwerth and Pattberg 2009). A survey by researchers Smith and Bandy demonstrates that between 1973 and 2000, environmentally-related TSMOs actually grew in popularity relative to other kinds of TSMOs, especially in the 1980s, second only to human rights TSMOs (Smith and Bandy 2005).

Over the three decades of the researchers’ study, TSMOs were also increasingly likely to involve multiple issues, in recognition of the fact that framing issues through alliances is an increasingly important means of fueling a movement’s evolution (Smith and Bandy 2005). TSMOs can serve to build consensus around the nature of an issue and strategies to confront it (Smith, Pagnucco, and Chatfield 1997). For this reason, of interest to researchers are alliances that form across movements with histories of difference or antagonism, such as the labor and environmental

movements (Waterman 2005) or the corporate and civic globalization movements, the union of which produced the World Social Forum (WSF) (Peña and Davies 2014).

This chapter explores why and how the labor and CSR movements have sought alliances to craft sustainability frameworks. In addition to understanding the substantive benefits directly related to stated goals, I investigate the indirect benefits to entities (public and private) that adopt sustainability and other frameworks.

Labor and Sustainability

Legitimate reasons exist for labor to share the traditional concerns of the environmental movement. Deforestation or loss of biodiversity can threaten an industry resource base (Keck 1995), while pollution from production facilities directly impacts the well-being of employees (Obach 2004). I am more interested, however, in what motivates organized labor to adopt sustainability for strategic purposes, in light of research suggesting that policies protecting the environment can threaten industrial workers’ jobs or wage rates (Obach 2004, chap. 2).

Alliances may allow organized labor to access processes that directly address its environmental concerns. The “green jobs” agenda, for example, brings workers into dialogue with prominent organizations and international bodies discussing climate change, resilience, and improved resource management (Ehresman and Okereke 2015; International Labour Office 2013). The EJ movement, whose origins link it directly to labor,3 aspires to unlock participatory channels for low-income and minority communities that have fewer resources to prevent environmental harms via political processes (Agyeman and Evans 2004). Reframing labor issues through environmental alliances can also facilitate the legitimacy, visibility, and financial sustainability of a political or social campaign. The Brazilian rubber tappers’ movement of the 1980s (Keck 1995) and the anti-oil and indigenous lands movements in Ecuador in the 1990s (Sawyer 2004)

3 Daniel Faber explains that the EJ movement arose out of the intersection of six separate

movements: civil rights; occupational health and safety; indigenous lands; environmental health; community-based, social and economic justice; and human rights (Faber 2005).

both capitalized on connections to international environmental NGOs based in Washington, DC, galvanizing swaths of donors at once to support labor and indigenous rights and conserve the Amazon rainforest.

The positioning of the EJ movement in the global South may encourage its labor constituents to solicit the support of more “traditional environmental organizations” when faced with lack of resources and capacity, more so than in the global North (Faber 2005, 50). While EJ in the North grew out of fights against illegal dumping of toxic waste in African American communities in the US (Bullard 2007), in the global South, EJ issues converge around exploitation of the working class in post-socialist regimes (Faber 2005, 46). Because, Faber explains, the EJ movement in the global South emphasizes class more than race, the labor movement in the global South is more likely to leverage connections with sustainability than its counterparts in the global North. These connections facilitate an opposition to socially and environmentally harmful corporate activities. Indeed, the labor movement and its environmental allies are often those prompting corporate entities to adopt the more stringent labor and environmental standards that are the basis of CSR and corporate sustainability programs (Georgallis 2017).

CSR and Sustainability

CSR responds to the profit-maximizing actions of MNCs that may be detrimental to employees, consumers, and the environment. Carroll’s corporate social performance model traces the origins of CSR back to thinkers and businessmen in the 1950s and 1960s, who debated the reach and merits of social responsibility (Carroll 1979). In Carroll’s framework, businesses have, in order of priority, economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary (voluntary) social responsibilities. These responsibilities ground a range of responses to fluctuating topical concerns, like occupational health and safety, environment, and discrimination.

Serious calls for corporations to take responsibility for destructive behaviors arose in the final decades of the 20thcentury, as publicity around environmental accidents and abuses of power informed the growing global conscience for threats like climate change, displacement, and

human rights violations (Idowu and Leal Filho 2009). Incentives for corporations to adopt CSR initiatives include adherence to global principles, national laws, or voluntary standards (Aluchna 2017), as well as competitive advantage, societal expectations, and shareholder and investor demands (Collier and Wanderley 2005).

Assuming a profit-driven business model, corporations will adopt CSR only if it carries a financial incentive.4 Orlitzky et al. analyze 30 years of accumulated research on CSR and corporate financial performance, concluding that the two are positively correlated (Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynes 2003). The analysis distinguishes between the effects of improvements to internal processes as a result of CSR programs, versus external perceptions of the company, determining that perception of CSR leads to greater financial gains than process improvements. Hill confirms that companies that are socially responsible (based on socially responsible mutual fund holdings) are more attractive to investors in North America and Europe, particularly over longer time horizons (Hill et al. 2007).

Environmental sustainability in the context of CSR could refer to efforts to minimize the use of raw materials and the production of pollution, promote environmental education, or project an environmentally friendly image (Aluchna 2017, 13). To pursue environmental sustainability, companies may engage in partnership with conservation nonprofits, or sponsor environmental education and clean-up initiatives (Cappellin and Giuliani 2004). Companies may also establish special departments, institutions, or foundations to formalize sustainability initiatives or to insulate them from the companies’ profit-driven activities (Cole 2012).

Motivations for a company to pursue environmental responsibility include many of the same CSR incentives mentioned above (e.g., shareholder expectations and public image), in addition to more direct links between environmental sustainability and product quality or financial performance. To this last point, Hart argues that three pillars of environmental strategies—

4 A primary opponent of CSR on this basis is Milton Friedman; his comments in Capitalism and Freedom disparage CSR for its “subversive” nature. Friedman maintains that CSR is antithetical and harmful to the pursuit of economic gain on the part of businesses (Friedman and Friedman 2002).

pollution abatement, product stewardship, and sustainable development—actually contribute to the economic prosperity of a firm (Hart 1995). Extending a resource-based model of business strategy (Barney 1991) explicitly to natural resources, for example, it follows that if production materials are valuable or rare, companies in fact may want to protect crucial raw materials or land to maintain a competitive advantage.5

Companies may nevertheless choose socially responsible activities that do not directly benefit the environment. Research suggests that firms’ demonstration of environmental responsibility correlates less strongly with financial performance than demonstration of social responsibility alone (Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynes 2003). Furthermore, a company may eschew reductions in waste production or the reuse of materials if undertaking those activities lowers profits.

Recycling, for example, may prove costlier than using raw materials, particularly when those raw materials are cheap, or when markets for certain recyclable materials are poor as a result of political or economic conditions (Profita and Burns 2017). Indeed, “the most constructive question is not whether CSR ‘pays,’ but instead when or under what circumstances” (Orlitzky, Siegel, and Waldman 2011, 9).

The lack of certainty regarding when exactly CSR might prove lucrative creates an incentive for businesses to advertise a false CSR agenda. Advocates and scholars have criticized corporations for seeking the financial benefits of overblown or ineffective responsibility efforts: Osuji

emphasizes the distinction between CSR that reflects regulatory compliance and CSR that is merely “instrumental,” or financially-driven (Osuji 2011). Ashman writes that even in the case of community-driven CSR programs that unite corporate and local actors, the ultimate beneficiaries or extent of the benefits do not always match those promised (Ashman 2001). For the

environmentally-inclined corporate do-gooder, whether intentional or not, Tokar asserts that the result of environmental sustainability as a component of CSR may very well be “greenwash”: a “cynical mixture of anti-environmental lobbying and environmentally friendly imagemaking” (Tokar 1997, 34).

5 Diamond mining operations in southern Africa provide an example of the socially exploitative potential of profit-driven defenses of natural resources (Hamann and Kapelus 2004).

Control of the architecture of CSR, then, could provide businesses the opportunity to develop standards that serve particular communities as much as private interests. Legally-driven CSR activities might on this basis produce more reliable results than voluntary monitoring efforts that allow private entities to craft and enforce their own codes of conduct (Seidman 2005). Through a case study of the Sullivan Principles, social responsibility standards that enabled MNCs to maintain good standing with shareholders despite continued presence in apartheid-era South Africa, Seidman concludes that voluntary efforts offer mixed results. There are indeed positive changes to internal corporate culture. The external beneficiaries, however, highly depend on who designs and enforces the efforts. To promote systemic, measurable change, Seidman calls for movements to “[bring] the state back in” to the processes that develop such standards (Seidman 2005, 178).

Reintroducing the state, however, assumes that public bodies are able to control effectively the processes that determine what is sustainable. CSR may in fact allocate power and opportunity for corporations to leverage loopholes in the very systems meant to regulate them (Aluchna 2017; Cole 2012). As the Brazilian case I present demonstrates, this power affects the public sector’s ability to control how sustainability-related laws translate on the ground.

Constructed Sustainabilities

Drawing from Gramsci’s concept of hegemony (Gramsci and Hoare 1985), Levy and Newell argue that the potential for businesses to exert influence over other entities in negotiation processes necessitates the application of a political economy framework to the analysis of environmental governance.

The development of each environmental regime is shaped by micro-processes of bottom-up bargaining and constrained by existing macro-structures of production relations and ideological formations. These structures, which themselves are the outcome of historical conflicts and compromises, ensure that the bargaining process is not a pluralistic contest among equals, but rather is embedded within broader relations of power. (Levy and Newell 2002, 84)

Levy and Newell’s framework facilitates connections among the discussions of transnational sustainability alliances, CSR, and public services infrastructure. The global movement for public private partnerships (PPPs) in the management of water, sanitation, and waste infrastructure, specifically, provokes similar concerns about government capacity to control private sector influence.

PPPs between governments and MNCs as mechanisms for managing water (Bakker 2007) and sanitation (Budds and McGranahan 2003) systems in the global South, as well as in

industrialized nations like the US (Baum Pollans 2017), gained popularity in the final decades of the 20th century. Proponents of PPPs hold aspirations about the relative efficiency of the private sector to address problems in existing, publicly-managed systems, although privately-managed infrastructure systems face many of the same challenges with regard to financial stability, political viability, and local suitability (Prasad 2006).

Akin to skepticism toward CSR, critics of PPPs in the global South point out discrepancies between what private actors profess they will achieve and the realities on the ground, in terms of the distribution of risks and benefits of infrastructure projects (Franco, Mehta, and Veldwisch 2013). Ahmed and Ali highlight the challenges that PPPs face to incorporate unregulated actors into waste management schemes, particularly in the global South, where the introduction of for-profit firms in waste systems threatens to drive out existing systems and actors (Ahmed and Ali 2004). As Budds and McGranahan note, the failure of the private sector to address problems in existing systems occurs because PPPs avoid solving those problems, not because of the nature of the PPPs themselves. In this way, the critiques of privatization of water and sanitation are

“missing the point” (Budds and McGranahan 2003). More collaborative processes for financing and developing these systems, some researchers suggest (as Seidman does for CSR programs), might address those problems.

Carolini offers an account of interactions between local efforts at participatory budgeting and external funding for large-scale public infrastructure in Maputo, Mozambique. She discusses a recurring challenge in cities driving economic growth in post-socialist countries in the global South (Carolini 2017, 127), whereby a participatory process meant to promote democracy is in

fact “premature,” a mere “light bandage” (Carolini 2017, 131) in the face of national and international neoliberal forces. Carolini argues that such a process “presents the illusion of democratic reform at the surface, while remaining insufficient as a transformative reform that heals the deeper gouge of undemocratic decision making governing the larger percentage of the public purse, which instead serves elite purposes…” (Carolini 2017, 131).

As I argue in this thesis, this phenomenon of “illusory” democratic reform exists in the context of Brazil’s sustainability politics, specifically implicating waste management reforms. To achieve deeper democratic transformations, we must therefore understand the contexts for the construction of processes that may perpetuate the problems they set out to correct.

3. CONTEXT FOR BRAZIL’S WASTE REGIME

Brazil’s political history is an important backdrop to the modern alliances among labor, state, and corporate interests that play out in the country. The authoritarian industrialist regimes in the post-war period featured state-supported growth and strong government-business relationships (Colistete 2007). As economist Renato Colistete explains, the developmentalist stance of the government, as well as the gap between profits and wages, contributed to strained relationships between labor and government in the early 1950s. Despite the recovery of labor unions and coalitions in the mid-late 1950s during the presidency of Juscelino Kubitscheck (1956-1961), organized labor suffered at the expense of firms’ profits in the late 1950s, into the early 1960s. Tension between the labor movement and authoritarian industry-backers persisted through the post-war decades and primed Brazil for subsequent military rule (1964-1985), during which the techno-bureaucratic military dictatorship severely, often violently, restricted organized labor and politics broadly.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Worker’s Party (PT) of later president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula”) united the demands of organized labor, along with other socialist-leaning and

progressive causes (Keck 1992). The dissolution of the dictatorship and emergence of an open state-society relationship, backed by the 1988 constitution, encouraged participatory processes. The emergence of what Avritzer calls “participatory institutions” ensured more formal structures for civic involvement, simultaneous with the rise of the PT (Avritzer 2009).

Military rule did not, however, transform the fabric of Brazilian politics, which continued to swing between the influences of a more traditional elite and a strong populist movement

(Hagopian 1996). The contrast between the neoliberal agenda (including significant increases in foreign investment, decentralization of services, and currency stabilization) of the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Brazilian Social Democracy Party, PSDB) of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (president of Brazil from 1994-2002), and the rise of the political left and the PT, exemplifies this political volatility. This contrast is in some ways overstated, however; the influence of business and international financing remained strong during the Lula government,

which maintained many of the Cardoso-era policies (Griesse 2007; Mollo and Saad-Filho 2006). These same political shifts and social divisions permeate the environmental space in Brazil.

Transnational Sustainability Movements in Brazil

Hochstetler and Keck explain that Brazil’s particular brand of “socio-environmentalism”

emerged out of the historical and political circumstances in the final decades of the 20th century, specifically the resurgence of democracy following the dictatorship, a strong federalist system, and the “continuous interplay of the formal and the informal” (Hochstetler and Keck 2007, 10). The result, they argue, is an environmental movement whose central tenets are social justice and bottom-up processes, a “sustainable development for poor people” (Hochstetler and Keck 2007, 13), situated in Faber’s class-motivated framing of EJ movements in the global South (Faber 2005).

At the same time, frequent, often scandalous, changes to environmental leadership, centers of power, and even laws, exemplify a lack of clarity on the part of Brazilian society and

government as to the framing of environmental problems. “This constant reshuffling tells an important part of the story of Brazilian national environmental administration since the transition to civilian rule…a profound uncertainty about the definition of environmental issues: Are they basically urban? About natural resource development—or their conservation?” (Hochstetler and Keck 2007, 39). Under such uncertain circumstances, we see an unsurprising amount of room for advocates, lobbyists, and citizens alike to weave their own definitions of sustainability into the implementation of regulation in Brazil.

Labor in Brazil

Political circumstances post-dictatorship gave rise to an environmentalism in Brazil that more strongly incorporated Marxist ideologies than environmental movements in North America and Europe, which by that time had developed critiques of the various manifestations of leftism that had emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. Timing was therefore a major factor shaping Brazil’s socio-environmentalism; the resurgence of the left and the development of environmentalism