The Baby (S)he Grows: Investigating the Causes of Gender

Differences in Entrepreneurial Quality

By

Lillian Sangeline Lakes

B.A. Economics and Management Information Systems Chatham College, 2002 M.B.A. Management Emory University, 20

11

MAMS STS INS71TUTE OF CHNOLOGYAPR 032017

LIBRARIES

SUBMITTED TO THE SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT RESEARCH at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

FEBRUARY 2017

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved.

Signature of Author: Certified by: Certified by: Accepted by:

Signature redacted

)ignature redacted

Department of Management January 20, 2017 Pierre Azoulay International Programs Professor of Management Professor of T chnologicalInnov

on, Entrepreneurship, and Strategic Management~udThesis Supervisor

N

Willia' ) Professor of EntrepreneurshipFiona E. MurrayProfessor of Technological Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Strategic Management

S ignatureThesis

Supervisor

Catherine E. Tucker Sloan Distinguished Professor of Management Professor of Marketing Chair, MIT Sloan PhD Program

The Baby (S)He Grows:

Investigating the Causes of Gender Differences in Entrepreneurial Quality

By

Lillian Sangeline Lakes

Submitted to the Sloan School of Management on January 20, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in

Management Research

ABSTRACT

Recent reports suggest that female entrepreneurs are increasingly relevant to business dynamism and economic growth, but it appears that they may be forming different types of businesses relative to male entrepreneurs. Using a homogeneous sample of MIT alumni, this study applies a novel methodology to assess these gender-based dynamics. Building upon the Guzman and Stern (2016b) methodology, I link alumni survey results to state business registration and USPTO administrative data to develop estimates of entrepreneurial quality. Next, I study the gender differences observed in entrepreneurial participation and build evidence regarding how entrepreneurial quality is intertwined with personal characteristics such as gender, parental status and age of children, controlling for human capital. I find that the presence of young children motivates the entrepreneurial entry of both parents, with a more salient relationship for mothers. Female graduates with young children are 4.2% more likely to found a for-profit firm than female graduates with older children. The equivalent increase for male graduates is only 1.8%. [ show that females lag their male counterparts in the probability of founding a firm with high growth potential particularly when they pursue entrepreneurship as parents of preschool age children. While preschool fathers are 0.5% more likely than those with older children to found a firm with high growth probability, there is no significant growth probability premium for mothers of young children.

Keywords: entrepreneurship, entry, growth, performance, gender, female, women, parents, children, age, preschool, work-family, conflict, alumni, public, policy

Thesis Supervisor: Pierre Azoulay

Title: International Programs Professor of Management

Thesis Supervisor: Fiona E. Murray

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am grateful for the tremendous and forthcoming guidance of Pierre Azoulay and Fiona Murray, especially since the Fall 2016 semester. This thesis would not have been possible without the leadership and insights of Fiona Murray and Edward Roberts, particularly regarding the 2014 MIT Alumni Survey. I truly appreciate the time and feedback of Emilio Castilla, Mercedes Delgado, Aleksandra Kacperczyk, Erin Kelly, Jason McKnight, Ray Reagans and Ezra Zuckerman. I would also like to thank Jorge Guzman, Daniel Kim, Samantha Zyontz and fellow students in the TIES Reading Group Seminar for their constructive comments and advice. Jointly, you give real credence to the ageless African proverb, "it

takes a village to raise a child", just as it takes an ecosystem to grow high quality entrepreneurial

ventures. In many ways, this thesis is my child. Thank you for being the village as I aspire to join the research side of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The usual disclaimer applies.

llakes(amit.edu.

Table of Contents

A b stract...2

A ckn ow ledgm ent...3

I. Introduction ... 6

II. Theoretical Background, Predictions and Hypotheses...9

1II. Data Setting, Sample Construction and Descriptive Statistics... 16

III. A. Using MIT Alumni Survey Data...16

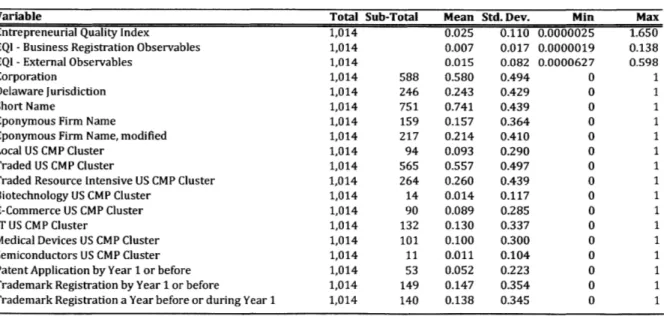

Il. B. Measuring Entrepreneurial Quality ... 18

III. C . Sam ple C onstruction ... 2 1 III.C. 1. Birth Place and Entrepreneurial Entry for Alumni with a Highest Undergraduate Degree... 21

III. C. 2. Place of Birth and Gender for Alumni with a Highest Undergraduate Degree... 22

III. C. 3. Educational Attainment and Entrepreneurial Entry for US-Born Alumni... 22

III. C. 4. Educational Attainment and Gender for US-Born Alumni... 23

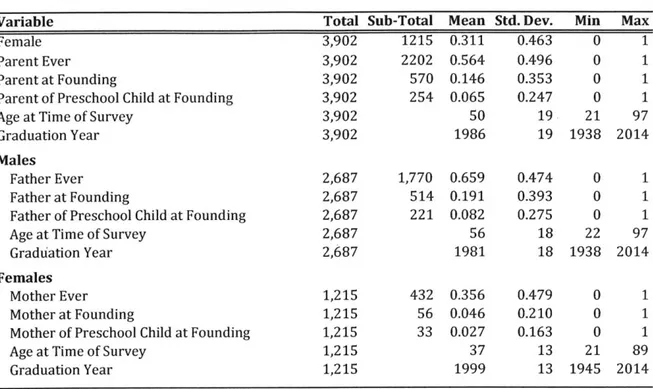

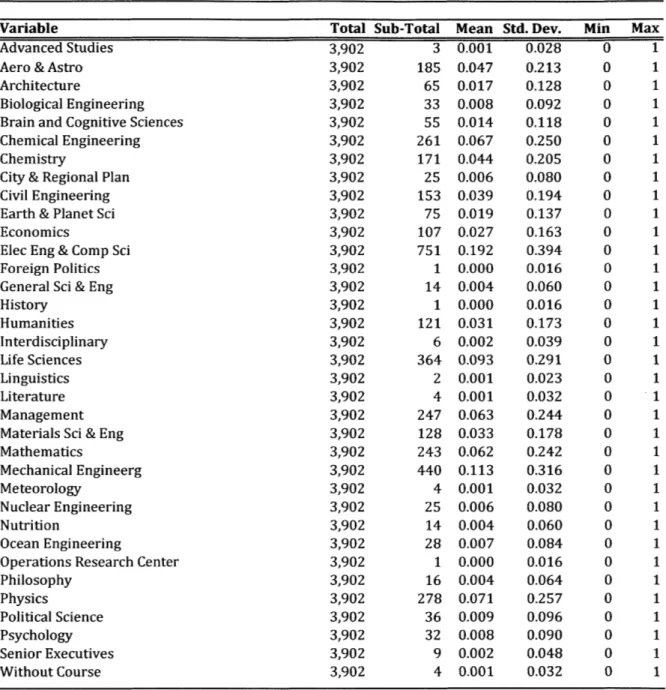

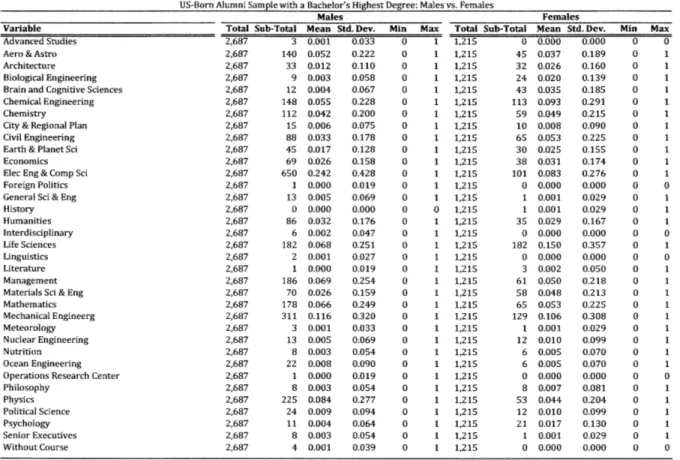

III. D. Variable Definitions and Summary Statistics... 23

IV . R esults... 2 8 IV. A. Empirical Strategy and Econometric Considerations ... 28

IV. A. 1. Discrete-Time Hazard Rate Model Estimation for Gender and Parental Status... 29

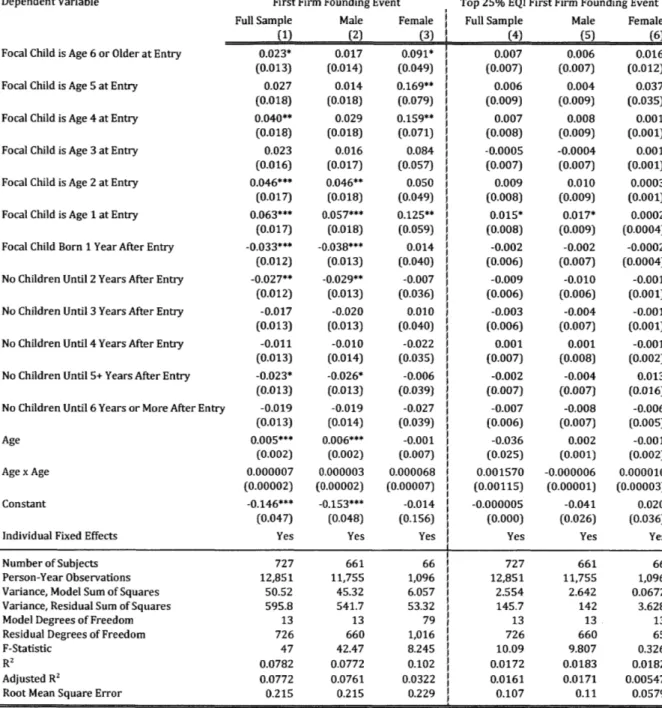

IV. A. 2. Fixed-Effects Linear Probability Model Estimation for Gender and Parental Stage... 30

IV . B . M ain E ffects... 3 1 IV. B. 1. Main Effect of Gender on Entrepreneurial Participation... 31

IV. B. 2. Main Effect of Gender on Entrepreneurial Growth Probability ... 32

IV. B. 3. Main Effect of Gender and Parental Status on Entrepreneurial Participation... 33

IV. B. 4. Main Effect of Gender and Parental Stage on Entrepreneurial Participation ... 33

IV. B. 5. Main Effect of Gender and Parental Stage on Entrepreneurial Growth Probability ... 35

IV. C. Heterogeneous Effects and Disentangling Mechanisms... 37

IV. C. 1. Heterogeneous Effects: Graduation Decade ... 37

IV. C. 2. Heterogeneous Effects: School and Department Affiliation... 38

IV. D. Robustness and Sensitivity Checks... 40

IV. D. 1. Alternate Parenting Specification: Number of Children... 40

IV. D. 2. Alternate High Growth Specification: Nowcasting Model... 41

IV. D. 3. Alternate High Growth Specification: Corporate Legal Form of Ownership ... 42

IV. D. 4. Alternate High Growth Specification: Broader Definition of High Growth Probability...43

IV. D. 5. Alternate Sample: Never-Parents Only ... 44

IV. D. 6. Alternate Sample: Entrepreneurs Only... 44

V . D iscussion and C onclusions...45

V. A. Discussion and Future Directions... 46

V. A. 1. Discussion and Future Directions -Entrepreneurial Participation and Transitions ... 46

V. A. 2. Discussion and Future Directions -Entrepreneurial Growth Probability and Causality... 47

V. A. 3. Discussion and Future Directions -Heterogeneous Effects and MIT Gender Disparities ... 49

V. A. 4. Discussion and Future Directions -Other Considerations ... 52

V . B . Policy Im plications...5 3 V. B. 1. Policy Implications and Caveats -Entrepreneurship Quality Distribution ... 53

V. B. 2. Policy Applications -Education, Ecosystems and Work-Family Conflict ... 55

R eferen ces ... 5 9

Section 1: M ain Descriptive Tables and Figures... 69

Section 2: M ain Regression Tables and Figures ... 93

Appendix A ... 103

Section A l: Descriptive Tables and Figures... 103

Section A

l

a: Variable Sources and Construction... 103Section A I b: Descriptive Statistics ... 103

Section A2: Additional Regression Tables...117

Section A3: Additional Figures... 166

Section A4: Snapshot of M IT Alumni Founded Firms... 190 Appendix B is unreported but available upon request

1. Introduction

Recent reports suggest that female entrepreneurs are increasingly relevant to business dynamism and economic growth, but it appears that they may be forming different types of businesses relative to their male counterparts. There are notable gender differences in employment (Fairlie & Miranda 2016), sales (SBO 2012), firm incorporation (Levine & Rubenstein 2016) and entrepreneurial financing (NVCA 2015), among others. Female entrepreneurs are roughly 10% less likely to own employer firms by the first, second and even seventh year of business survival relative to male entrepreneurs (Fairlie & Miranda 2016). Non-employer and employer firms often have very different performance outcomes. For example, while the average non-employer firm in 2012 had $46,914 in annual sales, the average employer firm had $6 million (SBO 2012). Females firms are more likely to be unincorporated. For instance, from the March Annual Demographic Survey Supplements of the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Bureau Labor of Statistics' National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), Levine and Rubenstein (2016) showed that even though females account for only 28% of incorporated businesses, they make up 41% of the unincorporated. Female-owned firms are also less likely to receive entrepreneurial financing. Only 7% of venture capital (VC) in the United States is invested in women founders (NVCA 2015). This is critical because VC backed firms tend to outperform their peers (Gornall & Strebulaev 2015; Harris et al 2014, 2016; Gompers et al 2016). Indeed, females are forming relatively different proportions of high growth firms and a careful assessment of these differential entrepreneurial patterns will help better understand their role in the economy.

Despite women founding firms with very different patterns of growth and financing, studies of gender and entrepreneurship often fail to account for this variation, instead lumping all young firms together and conflating self-employment with entrepreneurship of various types. In this thesis, I use novel entrepreneurship measures to understand the gender and family structure determinants of entrepreneurial entry and high growth (versus lower "quality") entrepreneurship amongst a sample of MIT graduates.

I

add to the understanding of gender, entrepreneurial participation and performance with the use of a new methodology (Guzman & Stern 2016b) to capture the variation in growth outcome probabilities of these young firms. Investigating the causes of gender variation in the distribution of firms will allow us to better understand the differences in entrepreneurial entry, employment, VC funding and related outcomes.Increasing attention to the growth distribution and the effect of young firms on labor market fluidity (Haltiwanger et al 2013) has sparked interest in the role of gender in observed patterns. Despite the National Women's Business Council announcing a major milestone of 10 million female-owned businesses nearly three decades following the passage of the Women's Business Ownership Act (NWBC

2015), it is evident that there are significant gendered distributional differences across firms. Multiple studies have examined these differences. Generally, they suggest that the gender differences in productivity, employment and growth rates persist (Fairlie & Robb 2009; Coleman & Robb 2009).

An emerging body of literature has begun to categorize and qualify start-ups to better predict those that are likely to be high growth firms (Henrekson 2007; Schoar 2010; Aulet & Murray 2013; Haltiwanger et al 2013; Fairlie & Miranda 2016; Guzman & Stern 2015, 2016a, 2016b; Levine & Rubenstein 2016). They indeed show that not all entrepreneurial ventures are the same. Some are high-growth start-ups with early identifiable intellectual property whereas others have little prospects for substantial growth outcomes. Guzman and Kacperczyk (2016) show that these distributional differences in high growth potential explain a large part of the funding differences between male and female firms. They find that ex-ante entrepreneurial quality, as measured in Guzman and Stern (2016b), explains almost two-thirds of the gap in access to external finance sources such as venture capital. I adopt a similar measure of entrepreneurial quality, but focus on the determinants that lead to varying quality estimates by gender.

This thesis explores the interactions of gender and parenting with entrepreneurial entry and the quality distribution of start-ups. In particular, I study a homogeneous sample of MIT alumni using the novel entrepreneurial quality framework to assess divergent gender relationships. Using the Guzman and Stem (2016b) methodology, I separate ventures into two groups; those with ex-ante high growth potential and those with lower prospects. Given that a broad literature suggests that women motivated towards entrepreneurship in part to resolve work-family conflict are more likely to own smaller, less growth-oriented firms (Buttner & Moore 1997; Cliff 1998; Morris et al 2006; Davis & Shaver 2012; Loscocco & Bird 2012; Th6baud 2015), 1 focus on gender and family variables to explore the degree to which they explain the different types of ex-ante entrepreneurial quality.

In contrast to studies that often survey only entrepreneurs, or specifically self-employed women, I capture how individual, family and background characteristics affect both the transition to entrepreneurship and distributional differences in ex-ante growth probability across gender lines. My study further differs from prior work as it enhances the richness of the survey results by carefully linking observations with administrative records to estimate early observable entrepreneurial quality. I explore the impact of being female on both the founding of a for-profit firm and the founding of a firm with high-growth potential. Next, I explore the effect of being a parent and the different effects of fatherhood and motherhood on both entrepreneurial participation and growth probability outcomes. Finally, I examine the influence of the age of children on the same outcomes, and how these influences differ by the gender of the parent.

Using the MIT alumni sample, I show that the presence of young children motivates the entrepreneurial entry of both parents, with a more salient relationship for mothers. Females with young children are 4.2% more likely to found a for-profit firm than females with older children. The equivalent increase for males is only 1.8%. These results support prior studies, which found that females lag their male counterparts in entrepreneurial propensity and pursue entrepreneurship as a channel to balance work-family conflict with the presence of children. However, I show that as a result of parental status, women found firms at the lower end of the quality distribution with a smaller probability of high growth. I also show that at stages where young children are present, results are even more noticeable. While preschool fathers are 0.5%

more likely than those with older children to found a firm with high growth probability, there is not a significant growth probability premium for mothers of young children. These findings offer insight into the choices that women make in founding high-growth start-ups and the stages where their choices are most prominent. In studying this area using MIT alumni data, I hope to better understand the evidence and inform policies regarding female business ownership with a specific focus on innovation-driven entrepreneurship.

Though differences in entrepreneurial quality account for a large part of the observed variation in outcomes, no studies have systematically analyzed the individual and background characteristics that sustain these differences. There is a gender story in why, when and how individuals select into entrepreneurship, whereby the often-gendered nature of the division of labor within the household shows up in entrepreneurial transitions, productivity and quality. I further explore this gender story to better understand where and at what point during the founding of a first for-profit firm different gender transitions and quality distributions may occur among founders. Put simply, the question of which baby (s)he grows - human and/or venture - and when can help understand the gender interactions between parenting children and founding ventures that results in discrepant entrepreneurial quality distributions.

This study joins the nascent empirical literature on categorizing and understanding the quality distribution of entrepreneurial ventures (Henrekson 2007; Schoar 2010; Aulet & Murray 2013; Haltiwanger et al 2013; Guzman & Stern 2015, 2016a, 2016b) as well as related work on the individual determinants that lie behind these differences (Fairlie & Miranda 2016; Levine & Rubenstein 2016). The current literature on the distribution of firms does not take into account individual-level and family structure determinants. The research on individual determinants does not fully capture the heterogeneity in firm growth probability. Other papers that investigate the career and family life cycles among graduates of elite educational institutions (Goldin 2008; Bertrand et al 2010; Herr & Wolfram 2012; Hersch 2013) are also

relevant. Whereas these economic studies have focused on employment outcomes and determinants of the wage gap, my thesis applies similar rigor to entrepreneurial outcomes. I add to these three distinct literature streams by focusing on both the distributional differences in firm growth probability and the disparate gender and family life cycle relationships using a rich, yet homogeneous sample of highly skilled university graduates.

This thesis delivers five interrelated insights: Even among a uniform sample of high skilled university graduates, females are less likely to become entrepreneurs. After taking the distribution of firms into account, females are even less likely to become high-growth entrepreneurs. Third, after the birth of a child, females are more than 1.4 times as likely to pursue entrepreneurial entry as their male counterparts. Among parents, although both fathers and mothers exhibit higher rates of entrepreneurial entry with preschool age children present, the female rate is more than twice that of males. Finally, among parents with preschool age children, while fathers experience a boost in the probability of a high growth start-up, mothers at this stage are not likely to experience a similar boost.

My thesis is organized as follows. Section 11 builds on background literature to develop hypotheses. Section III discusses the use of MIT alumni survey data, provides insight on the novel measure of entrepreneurial quality and describes my data and descriptive statistics. Section IV presents my empirical strategy and summarizes regression results. Section V concludes, discusses policy implications and lays out future directions for research building upon my findings. More details on the descriptive statistics, variable construction and alternate regression specifications are included in the appendices.

II.

Theoretical Background, Predictions and HypothesesA fairly large body of literature has helped advance our understanding of the interactions among gender, entrepreneurship and labor markets, leading to widespread debates on the topic. Evidently, women lag behind men when broadly examining entrepreneurial activities and related innovation-oriented activities (Hisrich 1984; Loscocco et al 1991, 1993; Hsu et al 2007; Roberts et al 2011; SBO 2012; Jennings & Brush 2013). To simplify a complex process and accordingly complex literature, it is useful to consider that gender sorting within entrepreneurship arises at several stages along the entrepreneurial pathway. It occurs before or during the initial decision whether to pursue entrepreneurial aspirations with an established employer or externally (Kacperczyk 2013), next in the type of venture formed (Buttner & Moore 1997; Cliff 1998; Morris et al 2006; Coleman & Robb 2009; Fairlie & Robb 2009; Davis &

Shaver 2012; Loscocco & Bird 2012; Guzman & Kacperzyk 2016) and finally in the opportunities for resources (Brooks et al 2014; Brush et al 2014; Abraham 2015; Thebaud & Sharkey 2016).

Kacperczyk (2013) finds that although women are less likely to leave their employers to become entrepreneurs, they are more likely to pursue alternative venturing routes available internally with their established employers. They also perform better venturing internally than externally. Kacperczyk suggests that female entrepreneurial participation and performance are much higher once corporate venturing is considered and attributes her findings to the family benefits associated with paid employment. Other preceding factors are also relevant, including education (Goldin 2008; Autor 2013, 2015), motivations for business entry (Buttner & Moore 1997; Cliff 1998; Morris et al 2006; Simard 2008; Davis & Shaver 2012; Loscocco & Bird 2012), and psychological makeup (Roberts 1991; Krause et al 2015; Kerr et al 2016). As the entrepreneurial pathway is pursued, rates of involvement in precursor or related activities also vary, for instance, patenting (Thursby & Thursby 2005; Ding et al 2006; Murray 2007; Hunt et al 2013), board participation (Stephan & El-Ganainy 2007; Ding et al 2013), and prior exposure to entrepreneurial experience (Roberts 1991). In this study, I show that although a unique homogeneous sample of highly skilled graduates from an elite academic institution, the MIT alumni

sample confirms the general consensus that females lag males in entrepreneurial participation.

Prediction 1: Even among highly skilled graduates

from

an elite university, females are less likely to become entrepreneurs.Despite increases in the rate at which women establish new businesses, women own less than 37% of all U.S. firms (SBO 2012). Without controlling for the type of business formed, women are disadvantaged as their businesses are typically smaller, grow more slowly, and are less profitable than those of their male counterparts (Hisrich 1984; Kalleberg & Leicht 1991; Bird & Sapp 2004; Jennings & Cash 2006; Kelley et al 2012). Female entrepreneurs also tend to segregate into sectors that are competitive, crowded, and less lucrative or likely to grow, such as retail, education, food service, and interpersonal care (Loscocco & Robinson 1991; Moore & Buttner, 1997; Sappleton 2009; Marlow & McAdam 2010).

MIT women lag men in entrepreneurial participation and this gap appears to be growing larger over time (Hsu et al 2007; Roberts et al 2011, 2015). Roberts et al (2011, 2015) suggest exploring the opportunity costs of entrepreneurial participation and the variation in firm formation across gender lines. In line with Hisrich's notion of heterogeneity in business ownership, research suggests that entrepreneurs are not all the same. Several researchers have attempted to describe these differences. Henrekson (2007)

distinguishes between "entrepreneurship" and "self-employment". Schoar (2010) uses the terms

"opportunity" versus "necessity", and "subsistence" versus "transformational". She finds that self-employment can act as a temporary transition for individuals in lieu of unself-employment. Aulet and Murray (2013) classify firms as either "innovation-driven enterprises" (ID.Es) or "small and medium enterprises" (SMEs). Generally, these researchers distinguish between start-ups with a high probability of growth, those that achieve an IPO or substantial acquisition outcome, and firms with lower likelihood of further growth outcomes. Aulet and Murray (2013) describe how two very different types of entrepreneurial firms, IDEs and SMEs, are formed with disparate motivations, have divergent effects on job creation, and vary on global orientation, types of jobs, ownership, risk and return, capital needs, successful exit potential (IPO and M&A), growth and profitability.

Guzman and Stem (2015) build on this research by estimating an index of entrepreneurial quality that links the probability of a growth outcome to start-up characteristics observable around the time of initial business registration. In subsequent work, Guzman and Kacperzyk (2016) share that female entrepreneurs tend to be better represented in the lower distribution of this index, more among SMEs than IDEs (2016). In this study, I therefore anticipate the MIT sample mirroring patterns within the broader population. I show that females are less likely to be represented near the top of the entrepreneurial quality distribution.

Prediction 2: Females are even less likely to become high-growth entrepreneurs.

Once businesses are formed, there is evidence that access to financial capital (Brooks et al 2014; Brush et al 2014; Th6baud & Sharkey 2016), tokenism and exclusion (Kanter 1977; Turco 2010), social networks (Fernandez 2000, 2005; Castilla 2005), network structure (Reagans 2003; Zuckerman 2006) and returns to social capital (Abraham 2015) are also key factors that share gender-based differences in outcomes. Women have lower success in gaining access to financial and social resources. When presenting similar business plans, women are disadvantaged in the opportunities for resources such as VC (Brooks et al 2014; Brush et al 2014; Thdbaud & Sharkey 2016). Abraham (2015) finds that anticipatory third party bias leads actors to disproportionately exchange resources with male network contacts. Consequently, female entrepreneurs have lower returns from the same access to social capital, a finding that is particularly salient in male-dominated occupations.

While research has uncovered gender differences along the entrepreneurial pathway, questions still remain with regard to the specific points in the pathway where they arise and the mechanisms that drive

them. A systemic study of the entrepreneurial lifecycle can better inform these questions. Anecdotal evidence supports research suggesting that women sometimes have different motivations for business entry. In an August 2009 practitioner workshop focused on women's career transitions from academic science and engineering to entrepreneurship (Didion 2012), MIT PhD alumni and former professor Lydia Villa-Komaroff, also the past CEO and current CSO of Cytonome, and key member on several government and scientific advisory boards, described factors that may help women to achieve greater success in STEM fields as training, support and personal characteristics. In the same workshop, Simard (2008) shared how gender differences in household characteristics and responsibilities affect participation, performance and outcomes of mid-level professionals in STEM. These findings echo Murray and Graham (2007), who find that concerns for balancing work and family limit how mid-career women socialize with men to build networks within commercial science. Simard attributed the gender gap in entrepreneurial participation to different perceptions of ability and skills necessary to succeed as entrepreneurs, differences in dual-career family configurations that create unequal structure of opportunity for women, and the perception that success is incompatible with family responsibilities. She also identified different motivations for entrepreneurship where women expressed a desire for self-fulfillment and work-family balance, which is perceived as incompatible with the growth and rapid scaling performance metrics of Silicon Valley high-tech VC firms (Simard 2008; Didion 2012).

The underlying practitioner concerns related to parenting and family structure are supported by research. Firestone (2003) argues that the biological sexual roles, particularly the division of labor in reproduction, are the root cause of almost all gender bias. Labor economics and employment relations' literature suggest a relationship between gender, human capital, family structure and labor market outcomes (Angrist 1998; Hundley 2001; Goldin et al 2008; Bertrand et al 2010; Herr & Wolfram 2012; Hersch 2013; Bertrand et al 2015). Often the parent with primary childrearing responsibility, women are more likely than their male peers to opt out of the workforce after having children. Angrist (1998) finds that while children lead to a reduction in female labor supply, fathers change their labor market behavior very little in response to a change in family size. Hundley (2001) suggests that marriage has a positive effect on the earnings of self-employed males and the burden of housework and childrearing limits the scope and earnings of self-employed females. Women who are graduates of elite institutions are more likely to opt out than graduates of less selective institutions as their households typically have higher earnings such that they can afford to forgo one income source (Goldin 2008; Herr & Wolfram 2012; Hersch 2013). Analyzing this trend, Goldin (2008) found that over time, women are increasingly electing to marry later in life and are more likely to space their children close together when they do marry in order to delay and reduce unemployment spells and related motherhood penalties. Goldin further found that though male

earnings strongly increase with family growth, females are penalized, especially those with three or more children.

Examining the causes and consequences of relative income within households, Bertrand et al (2015) found that most wives show aversion to earning more than half of their husband's income. This aversion affects labor force participation, income conditional on working, and the division of home production, among other things. In households where the female's potential income is likely to exceed the males, females tend to select roles providing lower compensation. When the female earns more than the male, she still has more responsibility for household chores and is more likely to divorce. Hence, women tend to pursue less demanding roles and forgo plausible income as they balance family responsibilities.

Organizational studies and entrepreneurship scholars often describe this notion of work-family conflict within organizations and households as a motivating force for the transition to entrepreneurship. Organizational practices in typical wage and salary employers tend to create more work-family conflict for women relative to their male peers (Hoffman 1985; Acker 1990; Boden 1996; Williams 2001; Jacobs & Gerson 2004; Castilla 2008) since as a cultural norm, women often have a greater share of household and family responsibilities (Blair-Loy 2003; Correll et al 2007). In comparison, business ownership can offer more autonomy and scheduling flexibility that female entrepreneurs with work-family conflict may find especially beneficial (Green & Cohen 1995; Arum 1997; Moore & Buttner 1997; Heilman & Chen 2003; Hughes 2003; Mattis 2004; Reynolds & Renzulli 2005; Maniero & Sullivan 2006; Thbbaud 2016). Despite most empirical tests of these theories finding support through a positive effect of parental status on women's self-employment, some studies have been mixed. For instance, examining the fertility histories of women in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), Taniguchi (2002) found that the number and ages of children, both which are time varying, to have a mixed effect on women's entry into self-employment. She did however find work experience and the presence of a spouse to encourage self-employment. Still, she could not confirm that self-employment allows working mothers to better combine their careers with household and caregiving responsibilities than does the wage and salary sector employment. Nevertheless, in line with the general view that work-family conflict is higher for mothers relative to fathers, I test the first hypothesis of whether entrepreneurial entry is disproportionately used as a means for female parents to resolve this conflict. However, the fact that results have been mixed suggests I may not have a strong prior. There are reasons to be believe it might go one way for certain types of entrepreneurs, for instance, those that limit venture growth in order to be more physically available for family obligations, relative to those focused on maximizing venture growth potential in order to perhaps financially provide and accumulate wealth.

Hypothesis 1: After the birth of a child, females are relativey more likely than males to pursue

entrepreneurial entry.

Several studies have explored not only parental status, but also specifically how parental stage, defined as the age of the youngest or prenatal child, affects entrepreneurial entry. In most cases, the outcome of interest is simply self-employment and the studies do not explore the resultant quality variation across ventures (Connelly 1992; Boden 1996). However, Carr (1996) does differentiate between incorporated and unincorporated businesses and finds a uniform family structure effect on self-employment in both. Using Census Public-Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) data, Carr (1996) finds being married, which enables self-employment and more risk-taking, and having young children, which limits women's workforce options, to be the two strongest predictors of women's self-employment. Compared to women with no children, mothers with only preschool children were 1.5 times as likely to be self-employed while women with both preschool and school-age children were nearly 1.7 times as likely to work for themselves. Interestingly, she found family structure variables to have a much lower impact on men than they do on women. Compared to men with no children, fathers with both preschool and school-age children (age 0-17 years) were 18% more likely than men with no children to be self-employed. In Carr's study, rather than family structure, human capital characteristics were the strongest predictors of male self-employment. Defining fertility as having at least one child under the age of six, Hoffman (1985) finds a negative fertility impact on female's hours worked whereas Boden (1996), using the same definition and the March Income Supplement of the Census's Current Population Survey (CPS), finds a positive fertility effect on selection into self-employment. Adopting a similar definition of fertility as Hoffman (1985) and Boden (1996), I test a second hypothesis on the effect of parental stage' on entrepreneurial entry. Although Carr (1996) found only a 1.18 increase for men compared to a 1.5 increase for women, I might expect closer gender effects on the MIT sample given alumni's uniquely high skillsets across gender.

Hypothesis 2: Among parents, both fathers and mothers exhibit higher rates of entrepreneurial entry with preschool age children present.

Another stream of literature has used survey data to explore the motivation for transitions to entrepreneurship (Buttner & Moore 1997; Cliff 1998; Morris et al 2006; Davis & Shaver 2012; Loscocco & Bird 2012). Generally, these studies survey only founders with no non-founder control group and have

focused on understanding growth intentions based on survey responses when work-family conflict is a concern. They find that women who transition to entrepreneurship in order to resolve work-family conflict are less interested in scaling and high growth. Instead, female business owners sought challenge, self-determination, absence of discrimination within organizations, and work-life balance (Buttner & Moore 1997). Relative to men, women were much less motivated by profits and business growth as a measure of success. Female entrepreneurs are much more likely to set maximum growth thresholds in order to manage work and family (Cliff 1998), be self-employed only part-time (Bertrand et al 2010), carefully consider various trade-offs (Morris et al 2006) and the amount of time and effort needed to grow their businesses (Loscocco & Bird 2012). Interestingly, Davis and Shaver (2012) found that whereas young men were most likely to express high growth motivations, mothers expressed high growth orientation more often than non-parent females. I build upon this literature by exploring the distributional differences in venture quality as well as understanding the individual and background characteristics of non-entrepreneurs relative to entrepreneurs that have a high-growth probability. Based on the labor economics and entrepreneurial motivation literature, my prior is that the presence of young children has a stronger incentive effect on males though the burden effect is stronger for females. From a methodological perspective, I believe using the novel entrepreneurial quality measure better captures the gender variation in the probability of growth outcomes than surveys regarding growth motivation as has been typical for studies of gender, entrepreneurial participation and performance.

Hypothesis 3: Among parents with preschool age children, while fathers experience a boost in the

probability of a high growth start-up, mothers at this stage are not likely to experience a similar boost.

A recent paper that attempts to disentangle the gender differences in entrepreneurial participation and performance does so at a high level of aggregation using country-level data. Thdbaud (2015) finds that in countries where institutional arrangements such as paid leave, subsidized childcare and flexible employment opportunities mitigate work-family conflict, females are less likely to pursue subsistence entrepreneurial opportunities. Her paper provides insight on the institutional and national policies that might reduce gender disparities thereby improving the performance odds of the innovation-driven ventures I study using individual-level MIT alumni data. In contrast to past studies,

I

test the relationship of parental stage on growth orientation using an index I form jointly from administrative records and individual-level survey data. There appears to be a gap in the literature without a systemic account for the differential gender effects across the full spectrum of firm outcomes. The implication of parental status and stage on the quality of entrepreneurial ventures is unclear. Children appear to have mixed effects on entrepreneurial motivations, quality and productivity that are particularly salient across gender lines. Thisis where I hope to contribute with a new methodological approach while filling gaps in the gender and entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship categorization and quality; and career and family lifecycle literature streams. The unique dataset that shows the whole distribution of firm quality along with individual lifecycle and family determinants enables such a contribution.

III.

Data Setting, Sample Construction and Descriptive StatisticsIll. A. Using MIT Alumni Survey Data

This thesis uses data from the 2014 MIT Alumni Survey. In the first study of its kind, MIT professor Edward Roberts along with then PhD student Charles Eesley undertook a survey in 2003 to explore the entrepreneurial activities of over 105,000 MIT alumni, and in particular the rate, location and success of their new enterprises (Roberts & Eesley 2011). The findings from the initial MIT research indicated that MIT alumni engaged considerably in new enterprise formation and growth, in particular, IDEs. However, they show extensive gender variation. Therefore, in 2014, Professors Roberts and Murray together with PhD student Danny Kim developed a new survey that expanded the scope of the instrument to include family structure data to better understand gender differences in entrepreneurship (Roberts et al 2015). The MIT alumni sample is particularly relevant and useful given the strong entrepreneurial impact that MIT alumni have had and a level of homogeneity that is unique for entrepreneurial studies. Roberts et al (2015) estimate that as of 2014, MIT alumni have launched 30,200 active ventures, employing close to 4.6 million people, and generating nearly $1.9 trillion in yearly revenues. This revenue figure falls between the world's ninth and tenth largest economy by GDP2.

In the 2015 report on entrepreneurship and innovation at MIT, Roberts et al (2015) study results from the 2014 alumni survey and share that the 12% overall rate of entrepreneurship among female MIT alumni survey respondents lags their male counterpart's 29% rate. Interestingly, studying entrepreneurship rates within five years of graduation by gender and graduation decade, they find that the gap appears to be increasing over time. These findings, although generally consistent with the proportion of firms by gender, are interesting given the broader trajectory of female firm ownership. While only 28.8% of nonfarm and privately held U.S. businesses were female-owned in 2007, by 2012, the proportion rose to 36.3% (NWBC 2013; SBO 2012). Yet, we do not see this pattern in the MIT alumni data. This further motivates the question on the trajectory and economic effects of the differential gender entrepreneurial quality distribution. If the proportion of female-owned firms is increasing nationally, but this increase is

2 According to the 2013 International Monetary Fund data, Russia produced $2.097 trillion in GDP, the ninth

largest, while India produced $1.877 trillion, the 1 0th largest (retrieved from

https:Lwww.iinf ora/external/country/indexahitm).

not substantial among high-skilled university alumni like those from MIT, this might suggest that the increase in female-owned firms may be coming from the lower end of the entrepreneurial quality distribution with women being pushed into entrepreneurship for subsistence reasons rather than transformational motivations. With all the strides that have been made through increased female post-secondary educational attainment and labor force participation, it is somewhat concerning if such progress is not translating to the trajectory of female-owned high growth firms.

The MIT alumni survey results suggest that alumni from leading universities play an important role in other areas related to the creation and growth of high growth entrepreneurial ventures. However, in the survey, females tend to lag men in these as well. For instance, rates of patenting by women alumnae are also lower, a result consistent with the work of Professor Pian Shu (2016). In terms of company exits, women-founded firms are relatively less likely to go public or become acquired. They are also less likely to fail. Overall, firms founded by female MIT alumni appear to be less volatile as a noticeably higher portion continues to operate as privately held firms. The exact mechanisms behind the differences in gender and company exits cannot be interpreted from the data without more careful linkage to novel measures of entrepreneurial quality at the time of firm founding and to measures that trace the entrepreneurial pathways pursued by MIT alumni.

The 2014 alumni survey provides a rich set of founder characteristics that enables the exploration of gender differences in the entrepreneurial activities of alumni; in particular, entrepreneurial participation and quality, and the stages where family and other background characteristics may sustain these differences. In this study, I use a new framework to assess these gender differences. First, I link the alumni survey results to state business registration and USPTO data to develop estimates of entrepreneurial quality. Next, I study the relationships behind the gender differences observed in entrepreneurial participation and build evidence regarding how entrepreneurial quality is intertwined with personal characteristics such as gender, parental status and stage, controlling for human capital. The use of a specific sample of high-skilled university alumni is particularly advantageous in understanding the individual characteristics and lifecycle stages where gender differences in entrepreneurship are particularly prominent. Although the first to study the effect of gender and parenting interactions using the novel approach of measuring early observable entrepreneurial quality distributions, my methodology in part follows a stream of studies that have used alumni survey data collection for entrepreneurship and innovation research (Burt 2001; Dobrev & Barnett 2005; Hsu et al 2007; Lazear 2004; Eesley 2011; Lerner & Malmendier 2013; Roberts et al 2014; Roberts et al 2015; Kim 2016; Shu 2016).

A key issue with surveying entrepreneurs across a broad sample is the non-trivial levels of heterogeneity amplified by gender lines. Some studies have shown that women are less likely to possess the human, social and financial capital or prior experience needed to recognize and effectively pursue high growth entrepreneurial opportunities. (Loscocco & Robinson 1991; Loscocco et al 1991; Renzulli et al 2000; Kim et al 2006). Others have shown that motherhood is a stronger predictor of non-professional women's transition into self-employment than professional women's, especially in contexts where supportive work-family policies are lacking. Relative to those trained professionally, nonprofessional women are less likely to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities with a high growth orientation (Budig 2006; Tonoyan et al 2010). In contrast to prior research in this area, I explore a very specific sample of university graduates with high levels of human capital over an advantageously long timespan that captures nearly the entire career of entrepreneurs. Studying a more simple population with specific skills helps to resolve the challenge of understanding the typically more heterogeneous samples in entrepreneurship studies.

II. B. Measuring Entrepreneurial Quality

Scholars have made significant strides in a variety of approaches that help to distinguish between the low end of entrepreneurial quality that is synonymous with subsistence self-employment and the high end that characterizes high growth ventures, particularly with early identifiable intellectual property (Henrekson 2007; Schoar 2010; Aulet & Murray 2013; Haltiwanger et al 2013; Fairlie & Miranda 2016; Guzman & Stern 2015, 2016a, 2016b; Levine & Rubenstein (2016)). For instance, focusing on a dichotomous outcome of employer versus non-employer firms to understand what predicts whether and when an entrepreneur hires the first employee, Fairlie and Miranda (2016) find that hiring is higher among incorporated and EIN businesses, and those with assets and intellectual property. Studying demographics, they show that female startups are less likely to hire than male-owned. In a similar vein, Levine and Rubenstein (2016) analyze demographics after separating the self-employed into incorporated entrepreneurs that are likely to be successful and earn more, and unincorporated business owners that are not as likely. They show that incorporated firm owners tend to be male and better educated. Motivated by a more distributional predictive analytics approach, Guzman and Kacperzyk (2016) measure whether and when female founded firms with otherwise similar levels of ex-ante quality are able to attract VC funding on the path to realizing growth outcomes. They find that a sizable amount of the gap in external financing is reflected in the distributional differences in entrepreneurial quality at the time of founding.

Given a preference for a distributional approach that captures the variation in growth probability before otherwise comparable ex-ante entrepreneurs are impacted by disproportionate opportunities for resources

(Brooks et al 2014; Brush et al 2014; Abraham 2015; Th6baud & Sharkey 2016), 1 choose to adopt the Guzman and Stem (2015, 2016a, 2016b) predictive analytics approach to measuring entrepreneurial quality. Their recent work provide the foundations necessary to link individual variables and firm features from the alumni survey data to state business registration and USPTO data to estimate the at-birth entrepreneurial quality of MIT alumni founded firms in an innovative way. Previously, although academics, politicians, and business leaders had long emphasized the importance of entrepreneurship in economic development (Knight 1921; Schumpeter 1942; Baumol 1968, 1990; Lucas 1978; Acs & Audrestch 1990; Baumol et al 2007; Gennaioli et al 2013), researchers had been unable to systematically connect the type of high-impact entrepreneurship found in regions such as Silicon Valley or Kendall Square with the overall incidence of entrepreneurship in the population (Fairlie 2014; Kappler & Guillen 2010; Amoros & Bosma 2014). Using a combination of business registration data to measure informative characteristics of each firm at or close to the time of registration ("start-up characteristics") and predictive analytics mapping start-up characteristics to growth outcomes observed with a lag, Guzman and Stern (2015, 2016a, 2016b) systematically characterize the growth potential of all firms within a given population and allow for the development of new tools for forecasting economic development through entrepreneurship in real-time. For my measure of high-growth, I adopt their Entrepreneurship Quality Index (EQI), which measures the average quality within any given group of firms, and allows for the calculation of the probability of a growth outcome for a firm within a specified population of start-ups.

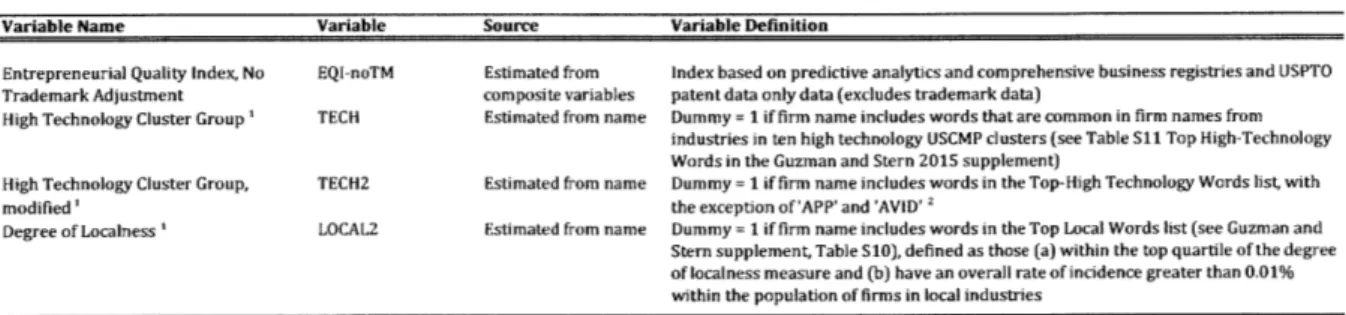

The methodology to estimate the key EQI dependent variable is specified in Table 3 of Guzman and Stern (2016b). EQI represents Model (5) of Table 3. Entrepreneurship Quality Index-Business Registration Observables (EQI-BR) represents Model (4) and Entrepreneurship Quality Index-External Observables (EQI-EXT) represents Model (3). The EQI-BR is a real-time "nowcasting" index that includes only information directly observable from the secretary of state's business registration site and therefore can be estimated as soon as firms register with the secretary of state. Guzman and Stem (2016b) use EQI-BR to estimate EQI for the more recent cohorts where USPTO data is not yet public. The EQI-EXT is a lagged index made up of external USPTO early-stage start-up milestones like the acquisition or grant of a patent or trademark within the first year after founding. This data can be linked from USPTO administrative records directly to the start-up to estimate EQI-EXT. Jointly, the EQI-BR and EQI-EXT predictors make up the informationally richer EQI.

I use the model (5) EQI measure as the main specification. Equations I to 3 below show how I estimate the EQI, EQI-BR and EQI-EXT specifications respectively as described in Table 3 of Guzman and Stem (2016).

(1) If either PATENT or DE is one, but not both:

EQI = (0.2 98EPONYMY2 x 2 4 7 8SHORT x 4.055CORP x 44 DE X 0.755LOCAL X 1.2 5 6TRADED X

1. 2 8 3TRADED RESOURCE INTENSIVE X 2 8 8 BIOTECH X 1.1 3 6 ECOMMERCE X 9 7I11T X 0.88 6 MEDICAL DEVICES

1.8 3 5SEMICONDUCTORS x 3 5.3 4PATENT X 5.014 TRADEMARK) x state fixed effects

If both PATENT and DE are one, there is a discounted interaction effect, such that:

EQI = (0.2 9 8EPOYMY2 x 2.4 7 8SHORT x 4.0 5 5CoRp x

0.

7 5 5LOCAL X 1.2 5 6TRADED X1.28-

TRADEDRESOURCE INTENSIVE x 2.288BIOTECH X 1.136ECOMMERCE X 1.971 X x.886MEDICAL DEVICES

1.8 3 5SEMICONDUCTORS X 19 6.4(DE x PATENT) x 5.014TRADEMARK) X state fixed effects

(2) EQI-BR = (0.27EPONYMY2 x 2.862SHORT X 0.705"C x 3.499TECH2 x 4.5 6 5COR x 40.37 DEX

1.145TRADED X 1.292TRADED RESOURCE INTENSVE x 3.1 3 9BIOTECH X 1.2 5 5ECOMMERCE x 2.401 X

1.1MEDICAL DEVICES X 3.025 SEMICONDUCTORS X state fixed effects

(3) EQI-EXT = (10.9 4TRADEMARK x 71.9 7PATENT) X state fixed effects

A key assumption in adopting the EQI predictive models generated by Guzman and Stem is that the process by which start-up characteristics affect growth remains stable over time, is fairly consistent across states not included in the (2016) state fixed effect adjustment3 and can be generalized to subsets of the population, such as MIT alumni. Therefore, the same model affects older and more recent MIT alumni founder cohorts similarly, as it does those in the thirty additional states and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Another assumption that Guzman and Kacperczyk (2016) confirm is that the process by which EQI predictors maps to equity event outcomes is similar for males and females. Section Al of the appendix provides more detail on the variable sources and construction, as well as variable definitions for alternate

EQl specifications.

3 State fixed effects are as described in Table 3 of Guznan and Stem (2016). The fifteen states accounted in Guzman and Stem's (2016) prediction model include AK, CA, FL, GA, ID, MA, MI, MO, NY, OK, OR, TX, VT, WA and WY. The MIT alumni data includes thirty additional states and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The five states not in the MIT alumni data are

IA,

MS, ND, SD and WV.III. C. Sample Construction

I

test my hypotheses using a sample of 3,902 undergraduate US-born MIT alumni that listed an undergraduate degree as their highest level of education. This corresponds to roughly 20.5% of the alumni survey respondents. To ensure the MIT alumni sample is well defined and homogeneous, I chose to limit observations to only US-born undergraduates and eliminate founders who started firms outside the US. In constructing the sample, several independent sample t-tests were conducted to compare entrepreneurial participation and female representation between the alumni observations included in the final sample and those dropped given place of birth and highest level of education.III. C.1. Birth Place and Entrepreneurial Entry for Alumni with a Highest Undergraduate Degree My empirical tests indicated that there were possible biases in response for international students as well as uncertainty regarding whether they naturalized later on. As part of the alumni survey, a key question asked was "Were you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident (held a permanent visa)

when

you attendedAMIT?" This question does not allow one to distinguish between US citizens and permanent residents. With complementary responses to questions regarding current citizenship status at the time of the survey, I can gauge those that were US citizens by their MIT graduation only if they were US-born, US naturalized with a naturalization year provided that was prior to their MIT graduation, or with less confidence those who responded to the above question since they could also just be permanent residents by graduation. Only 201 foreign-born citizens that provided a naturalization year on or before their graduation year could be confidently considered US citizens by their MIT graduation, along with US-born alumni. Given this uncertainty and possible response bias in those that provided naturalization years and those that did not, I limit the sample to only US-born alumni.

The independent sample t-tests run for place of birth and entrepreneurial participation for the 4,530 alumni respondents with undergraduate highest degrees provide further confidence in my decision to drop foreign-born alumni4. For this subsample, there is no significant difference in entrepreneurial participation between US-born and foreign-born alumni. However, those that were not US citizens by their graduation appear to be significantly more entrepreneurial than those that were at the 5% confidence level.

I

exclude foreign-born alumni as they may have different reasons for or against pursuing entrepreneurship based on their immigrant status and timing of US residency or citizenship. Interestingly, among those that were US citizens by their MIT graduation, US-born alumni are more entrepreneurial4 The empirical tests are unreported but available upon request via Appendix B.

than foreign-born alumni at the 1% significance level. This gives confidence in the decision to exclude foreign-born alumni for homogeneity reasons.

III. C. 2. Place of Birth and Gender for Alumni with a Highest Undergraduate Degree

T-test results by gender provide further confidence in the decision to drop foreign-born alumni from my analysis. There is evidence that including foreign-born alumni could conflate the effect of gender and parenting. Females are better represented among foreign-born alumni relative to US-born alumni at the 1% significance level. However, females are better represented among alumni that were US citizens by their MIT graduation relative to those that were not at the 10% significance level. Among those that were US citizens by their MIT graduation, females are better represented among foreign-born alumni. This is significant at the 1% level. The heterogeneity in timing of immigrant status and potential survey response bias related to citizenship may have a confounding effect on the gender and entrepreneurship results.

III. C. 3. Educational Attainment and Entrepreneurial Entry for US-Born Alumni

Given the heterogeneity in timing and length of advanced degrees, I limit the sample to only 3,902 alumni respondents with a highest undergraduate degree. I therefore exclude MIT undergraduates that went on to get an advanced degree as I cannot determine the timing and length of subsequent schooling and how the opportunity cost of the time spent in attaining the advanced degree affects their entrepreneurial propensity. T-test results by educational attainment provide further confidence in this decision.

Alumni with a highest master's degree are the most entrepreneurial subsample, followed by those with an undergraduate and then doctorate highest degree. The mean differences are statistically significant at the 1% level. While masters-level MIT alumni are significantly more entrepreneurial than undergraduate alumni at the 1% confidence level, there is no difference between MIT undergraduate and doctoral alumni's entrepreneurial propensity. When considering all MIT undergraduates, those that go on to get a masters-level advanced degree elsewhere are not significantly more entrepreneurial than those with no schooling beyond an undergraduate degree. This is true for all five MIT schools. However, those that go on to get a doctorate degree elsewhere are significantly less entrepreneurial at the 1% confidence level. This could partly be because they spend more time in school and thus have less time to start an entrepreneurial venture. I exclude all alumni with advanced masters and doctoral-level degrees for homogeneity. I cannot confidently distinguish the effect of the timing, length and opportunity cost of subsequent schooling from their entrepreneurial propensity.

Ill. C. 4. Educational Attainment and Gender for US-Born Alumni

Women are represented among MIT undergraduates in higher percentages relative to masters and doctoral-level alumni. Whereas 31.1% of the 3,902 sample with a highest undergraduate degree is female, only 25.5% of the equivalent 3,936 sample with a highest master's degree is female. For the 2,976 sample with a doctorate degree, females account for only 23.2%. Furthermore, among MIT undergraduates, there is no significant difference in female representation between those that go on to get advanced degrees and those that do not. However, the heterogeneity in timing and length of advanced degrees may conflate the effect of gender and parenting on entrepreneurial entry and growth probability. For these reasons, I remain confident in my decision to limit the sample to only 3,902 respondents with a highest undergraduate degree. T-test results by gender provide further confidence in the decision to drop advanced degree alumni and MIT undergraduates that attained advanced degrees elsewhere from my analysis. At the 1% significance level, alumni with highest undergraduate degrees have the highest percentage of women relative to those with advanced degrees. Not surprisingly, masters-level alumni appear to have a higher percentage of women than doctoral-level at the 5% confidence level. Similarly, MIT undergraduates regardless of additional schooling have the highest percentage of women relative to MIT masters and doctoral alumni, at the 1% significance level. Also, MIT masters-level alumni have a significantly higher percentage of women relative to doctoral-level alumni at the 5% confidence level. Among MIT undergraduate alumni, there is no significant difference in percentage of women between those that go on to get advanced degrees and those that do not. This is also true within all MIT schools except the School of Humanities, Arts and Social Science (HASS)5, where those that go on to pursue masters-level degrees have a significantly higher percentage of women than those with only an undergraduate degree at the

10%

confidence level. However, the subsample size of HASS undergraduate alumni that pursue masters-level degrees is only 73. The sample of MIT alumni with a highestundergraduate degree remains the most homogeneous without confounding from the opportunity cost of time dedicated towards advanced schooling. More detail on the sample construction is included in

Section Al in the appendix.

II. D. Variable Definitions and Summary Statistics

To estimate the entrepreneurial entry and quality outcome variables, I combined data from both the alumni survey and administrative records. For each firm founded by MIT alumni survey respondents,

I

S

MIT has five schools (the School of Engineering (established in 1932), the School of Science (established in 1932), the School of Architecture and Planning (SAP, established in 1932), the School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (HASS, established in 1950) and the Sloan School of Management (established in 1952)) and oneinterdisciplinary joint educational program, the Harvard-MIT Program of Health Sciences and Technology (HST,

established in 1970). Figure 5 and 6 provide a breakdown of entrepreneurs in my sample by school. More details

on MIT schools and academic departments are available at http//web.mit.ed/facts/acadenichtml.