DESIGN FOR THE WORKPLACE: A NEW FACTORY By

Jenny Potter Scheu B.A. Middlebury College

1973

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of

Master of Architecture at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY January 1979

) Jenny Potter Scheu 1979

Signature of the Author .. ... ... ..-.. . . . ....

tmen of Arc ure, January 18, 1979

Certified by ...

Chester L. S 6rae, Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by ..

Imre Halasz, Chairperson Departmental Committee for Graduate Students ...,

t

The people I love best jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight. They seem to become natives of that element

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half submerged balls.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience

who strain in the mud and muck to move things forward who do what has to be done, again and again.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who stand in the line and haul in their places, who are not parlor generals and field deserters but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire be put out The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust. But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident. Greek amphoras for wine or oil

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry and a person for work that is real.

Marge Piercy "To Be of Use"

ABSTRACT

DESIGN FOR THE WORKPLACE: A NEW FACTORY By Jenny Potter Scheu

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 18, 1978 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Architecture

The production capacities of industry have enlarged greatly in this century. While this has meant a wider spread of material goods, this growth has occurred at the expense of those who have carried out this production. Worker control and participation in the shaping of the product and of the work environment has diminished.

The design of industrial buildings has not commonly been the domain of archi-tects. Industrial forms have largely been determined by characteristics of the production process, often at the expense of those who work in those processes.

The issues of the workplace are varied and extremely complex. They are political and social before they are physical. But there are ways in which physical organization and built conditions can have an impact on the quality of the work experience.

Worker dissatisfaction has in some cases forced changes in the organization and from of the work environment. Some architects have recently been involved in the design of forms to accommodate these changes. There has been some in-fluence by designers in the changing of the organization itself.

In this thesis I will argue that architects must be increasingly involved in designs for industry, and gain an understanding of the factors whichinfluence

industrial physical form. I have worked to apply these factors to a design for a specific site and industrial program. My intent was to gain a broad under-standing of the issues and evaluate my search.

Thesis Supervisor: Chester L. Sprague

Acknowledgements

My special thanks to Chet Sprague who has asked the best and the hardest questions from the beginning, and to my family for their unending support.

My thanks to the following persons who have shared invaluable experiences and information with me: Jack Myer at Arrowstreet and M.I.T.; David Noble at M.I.T. and General Electric; David Nygaard at Crosby Valve and Gage, Company; Joanie Parker at the Dudley St. Machinist Training Cbnter; Tony Platt at Anderson/Notter/Finegold; Robert Robillard at Morse Cutting Tools; Gary Swanson at the

Carlson Corporation; Linda Tuttle on her own; Waclaw Zalewski at M.I.T.; Barry Zevin at M.I.T.; Katherine at Ramsay Welding Research

Company; and Robert Hughes, who grew up in this neighborhood of North Cambridge.

And finally my gratitude to the following folks who have pro-vided supports from points near and far: Louisa Bateman, Len Charney, Lynn Converse, Sam Farrow, Andrea Giles, Gale Goldberg, Pat Gorai, Lynn Fry Hunting, Francie Joseph, Ron Joyce, Will Osborn, Happy Paffard, Rob Pefia, Peter Polhemus, Darleen Powers, Paul Pressman, Scott Reiner, and all the other thesis students.

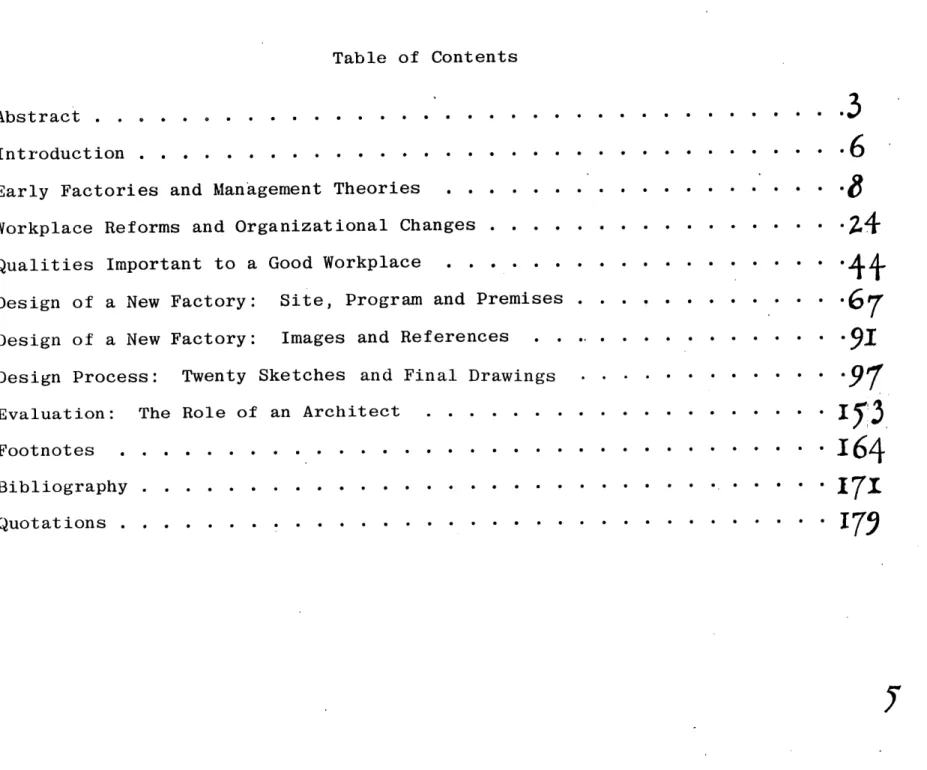

Table of Contents

Abstract .... ... . . .. . . . . - - - -. Introduction . . . . . .. . .. - - - -. - - ..-. Early Factories and Management Theories . .

Workplace Reforms and Organizational Changes . . . . Qualities Important to a Good Workplace . . . . . . Design of a New Factory: Site, Program and Premises Design of a New Factory: Images and References . . Design Process: Twenty Sketches and Final Drawings

Evaluation: The Role of an Architect . . . . . . . Footnotes . . . . . . . . . - - - -Bibliography . . . . . .. .. - - - -. Quotations . . . . . . . .. . . -. - - - -. - - - -3 .. 6

.24

-67

~9'.

0

97

.1

0 0 0 0 0

6 4

.17.1

.J79n

- - - -

1-

-- --INTRODUCTION

There are many factors which influence the physical form and organization of an industrial building. Among these are: the process and product, the needs of those who work there, the organizational philosophies, the exist-ing local context, site microclimate, and cost. The rank-ing-of their importance has varied over time and according to specific projects.

While they are all interconnected, theplanning and design of any industrial building requires careful atten-tion to each of these factors. With such a focus will

come some awareness of that which is of constant and under-lying importance beyond issues specific to certain

industries.

In our times, cost, process and product, and organiza-tional philosophies have generally been the primary deter-minants of physical form. Their importance is based upon the assumption that the goal of industry is the increase of productivity which leads to profit.

Philosophies ofmanagement and organization form the basis for all the factors which influence physical form. Some have led to a stronger focus on the process of produc-tion in its most raproduc-tional extreme. Others begin to recog-nize the needs of the people who are part of the process.

The kink in my back is gone. Yesterday's work did it.

There is a production game that is played between workers and their supervisor. The supervisor or foreman almost always wants the people he is responsible for to produce more. Most workers seem to know instinctively that

'more production' either leads to the challenging game of 'you want more but I don't want to work harder' or to a bottomless pit. The challenge of the game can be the most interesting part of the job.

Robert Schrank

Early Factories and

The first factories were narrow and long in plan to allow the natural light to illuminate the work space, as there was no electricity. These buildings were designed by architects with the express intent that the classical facade have an institutional, almost church-like quality. There was less thought given to the inside space.

Already by the 1840s came steam power, a technological innovation which changed the location of these factories. As coal could now be used to power factories and railroads, it was no longer necessary that they be located at the

sources of water power. More factories were built near population and trade centers, and rather than building the company housing around the factory, the housing of the workers was left to the towns and the private sector.

With the changed source of power also came changes in the machinery, and it was increasingly heavier. The famous Pemberton Mill, with its prize classical exterior collapsed under the weight of the new machinery. This catastrophe had ominous implications for the architects of the period. The insurance companies who covered these factories began to demand some involvement in the design of the factories. The insurance companies turned to engineers, not architects,

Previously most engineers had been civil engineers, involved in such public sector projects as bridges and dams. The design of factory buildings was the first incidence of engineers in the private sector. Their in-volvement minimized the physical appearance of the factory. These physical changes were supported by the factory owners who became increasingly interested in fast-built, cheap and functional structures. By the 1850 standard factory designs were published in books.

The earlier concern for beauty in the exterior was lost, and the notion that the interior be functional becomes increasingly important. The buildings become' proportionally lower and wider. The structural members which support the roof are many, and the debris collects around them making the attic space an incredible fire-trap. As with many things, it was not until after several

disastrous factory fires had occurred that innovations were developed to change the attic space and roof. In the

1860s a slow burning roof of heavier timbers was designed to make the attic more open, preventing the collection of flammable debris. The slope of the roof was less steep and the roof itself was lighter, which allowed the exterior bearing walls to be lighter, and large windows

Increasing attention was paid to the functional aspects of the interior, and as the machines became in-creasingly complex, attention was paid to the functioning of the "machine-like" work force as well. Engineers had more impact upon the work processes. With the importance of the smooth flow of production, the factory itself

becomes like a machine and increasingly distant from

earliest attempts to link the factory in a symbolic formal sense to non-industrial (church) institutions.

Much of this increasingly rational approach came

from the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor and his "Theories of Scientific Management" which were proposed in the 1670'. His ideas had an enormous impact on the production process.

Until that time factory production was determined by the skill of the individual craftspersons on the job. Knowledge of the skill was important and was handed down from generation to generation on the job.

According to historian David Montgomery, there was a strong moral code amongst these workers. The code em-phasized collective support and mutual assistance on the job. The rate of production was also determined in the factory. A worker who produced at a faster pace was con-sidered to be dishonorable, one who undermined the jobs of

others. Beyond this tacit moral code the collective group set work rules. For example, a group of window glass blowers rules included: No working from June 15 to September 15 (i.e., no working near hot furnaces during the summer heat); a standard size, based on the size that a person could blow, was set; similarly, there was a limit to the number blown each hour; quality work was expected and workers were fined for the mistakes they made.

There existed a sense of dignity and pride in the work done to such high standards. And there was a collec-tive direction which rejected both direccollec-tives from manage-ment as well as individualistic behavior.2

From his observations and research, Frederick Winslow Taylor concluded that most factories were very inefficient. He devised four "steps to scientific management" which

struck blows at- the traditional order.

First, each task should be developed as scientifically as'possible to replace the methods handed down in the tra-ditional ways. Second, train individual workers for

specific tasks. Previously workers were placed at jobs of their own choosing or randomly, and learned the tasks on the job. Third, do everything to make performance of each task as efficient as possible. Fourth, management should

take over all work for which they were more capable,

dividing work and responsibility equally between managers and workers. Previously workers had done most of the work and collectively held much of the responsibility.

Taylor felt that increased efficiency meant potential benefits to both the management and the work force. Taylor advocated the notion of the new "functional foreman,"

who achieved the position be being one who knew more than the others about a certain task or operation. Rather than rise in the factory hierarchy or represent some moral code, the "functional foremen" could be trained for their role. Foreman positions were established for each task, thereby

increasing specialization and establishing more positions between managers and workers.

Workers were separated from their individual methods of doing their task and from their individual tools.

Previously the workers had owned and maintained their own tools. With Taylor began the practice of having standard-ized tools provided by the factory in an attempt to

minimize product discrepancies which had resulted when workers used their own.

Taylor believed unabashedly in the notion of human perfectibility and upward mobility. He believed that the

rational perfection in work was possible when all the necessary assistance was provided. He established the idea of an incentive system in which workers were re-warded for performance excellence. Each worker's po-tential for upward mobility rested upon one's ability to perform better than those around one.3

One key word which describes the intent and influence of Taylor's ideas is flow. There was much interest in constructively channelling the energies of the worker. To this end Frank and Lillian Gilbreth (of "Cheaper by the Dozen" fame) developed their concept of time and mo-tion studies. The Gilbreths initially studied

brick-layers at work analyzing the physical motions of each task. They isolated eighteen separate motions and after further study suggested a new method which involved only two mo-tions. When trained in the "new" method, the average

bricklayer could lay 350 bricks per hour--an almost three-fold increase from the rate of work at the old "tradi-tional" method. New, lighter tools were invented to make the work easier and more efficient. The Gilbreths de-veloped flow charts, merit rating systems and other ways of analyzing efficiency of workers. They felt that com-munication between all parts of the factory was important,

especially between workers and mangement and advocated the use of simple but specific written instructions.

Clearly, the increased efficiency led to an increase of production. Taylor encouraged management to learn about factory processes and, in the way of the Gilbreths, consider changes which will increase the efficiency.

While he encouraged communication between managers and workers (through the foremen) he proposed that manage-ment move to a corner of the factory. In later times this separation of planning from production was carried further as management moved away from the factory to an office

4 "downtown."

The moral code which had (collectively) set standards and limits to work was seen as laziness by Taylor who did not believe that those doing physical work had much capacity for understanding. The notion that work is not creation but is production makes the process more important than the product. The power to make decisions about how the work is to be done is removed from those who do the work. The what? why? and how? of production are questions no

longer decided by the workers. Management is to set standards and judge merit. The number of managers increased.

Montgomery describes an early Ford assembly plant as a "perfect situation for scientific management." The company slogan for hiring was "No experience is preferred," and there were 14,000 unskilled assembly line workers to 200 highly skilled workers in machine tool production and repairs. There were as well many managers and supervisors. (A further example to illustrate the trend toward an in-crease in white-collar staff--In the 1890 coal mines there was one foreman for 100 miners. In 1970 coal mines there is one supervisor for every eight miners.)5

While there have been occasional "Algeresque" tales of "rags to riches" mobility, it is clear that the trans-formation of industry toward a national science did much to increase the workers' dependency upon industry, narrow-ing rather than broadennarrow-ing their skills.

The flaw of Taylor's theories was its disregard for humanity. (A proteg6 of Taylor's,Karl Barth, spoke of a day "when all the world would run to a single metronome.")6

The ideas of Taylor were acclaimed by many around the world (including Lenin in Russia). His theories brought

major change to industry everywhere but there was resistance from the start.

The Gilbreths did studies on the impact of fatigue to health and productivity. Others later urged management to be sensitive to the human nature of the worker by

stressing the need for simple encouragement beyond pay* incentives. Another engineer, James Hartness, wrote a book in 1921 which he called The Human Factor in Works Management. In this book he encouraged those who

de-signed machines to gain a more intimate knowledge of those workers who would be using those machines. He believed

that repetitious work freed the workers' minds to con-sider other ideas. (Perhaps an interest that human minds be -efficient at all points too.)

While these concerns represent some of the first involvement of psychological and social sciences in the workplace issues, these reforms were still directed toward the goal of increased productivity. The strongest

resistance came from the workers themselves.

The period of 1910 to 1930 was a time of worker struggle. There was widespread resistance to the

in-centive system's hourly rate plus a premium for extra work-for it broke down the moral code and collective tradition. Time clocks and time and motion studies were

abolition of these studies and in time the 8-hour day was set. Later depressions and periods of unemployment over-whelmed some resistance though organized union strength

.8 grew in time.

In his book America by Design Science, Technology and the Rise of Corporate Capitalism, David Noble points out that it is unclear how such resistance shaped

in-dustrial process. "The engineering and management of production rarely if ever involved simply the transfer of designs from drawing board to shop floor. New ap-proaches were introduced and abandoned, or endlessly

revised to better adapt them to the work situation, a context in which people with conflicting interests,

rather than mere considerations of elegance or efficiency, determined the final outcome. Without a precise descrip-tion of how this has happened, the history of technology must remain a one-sided and hence distorted account."9

In his book Designing for Industry, Grant Hildebrand speaks of the early 20th century and the growing awareness of the industrial landscape. The awareness manifested itself in two ways: first as a symbol for designers, and second as an "operational" and "economic" challenge.

Both ways were aware of management needs but not the needs

of the entire workplace community. The factory image and the efficiency of the production process were key determinants of form.

In the first way, the importance of the factory image spread beyond the industrial landscape. Ralph Bennett has described the superficiality of the Modern

Movement's concerns for the industrial aesthetic in the

following way: "I believe that the mechanistic

enthu-siasms of the modern movement, while enabling a clarified understanding of many architectural situations, prevented any constructive reformation of the workplace, especially the industrial workplace. It was precisely the confidence placed in industrialization as providing a better life to the users of its product which prevented any investiga-tion of the actual working situainvestiga-tion within the greatly admired factories. The factories themselves were

im-portant icons for their mechanistic and therefore truthful form, but not for the quality of environment provided

for their occupants."1 0

Hildebrand points out that the Modern Movement's

awareness of the industrial landscape involved few changes to the traditional design approach. "This view presumed the architect to be acting in his traditional artistic

guise as the conscious interpreter of the spirit of an age, and this was the way taken most notably by Peter Behrens and Walter Gropius. There was another way as well, however, that involved changing one's view of the architect's role, setting aside his traditional aesthetic concerns in order to concentrate almost exclusively on a more complete fulfillment of this building type's practical operational and economic needs. This was an at least equally fertile approach in that it held great promise for real operational solutions, from which new

formal patterns could be generated--patterns that had not been part of the original, conscious intent of the

designer.' 11

Of these two approaches, the latter was that of

the famous designer of industrial buildings, Albert Kahn (1869-1942). Practicing in Detroit, Kahn designed over two thousand factories in his career as well as many non-industrial structures. Albert Kahn was a very dif-ferent architect from those who glorified the industrial aesthetic. "His practice was not to be of the usual sort, and for his particular future he began with an

ideally open neutral attitude extraordinarily uncommitted to an expressive formal or compositional position. His

approach from the beginning was pragmatic and it con-tinued to be so throughout his career."1 2

The clients for whom Kahn did the most work were the automobile industries. le designed huge complexes for Ford, Chrysler, Chevrolet, Fisher, De Soto and General Motors. Kahn's office saw its task as putting an effi-cient economical enclosure around an industrial process. They left the process organization to the industry who in

their view was more capable in that area. The office was enormously successful, designing a huge volume of industrial work and numerous non-industrial projects which came

through contacts with top industry executives.

Hildebrand reveals a personal trait which may prove important to an understanding of the new role of architect as typified by Albert Kahn:

"All the evidence indicates that he had the prized quality of being a good listener. Men of humble beginnings often retain from early life a feeling that the other

fellow may know a great deal, that the rest of the world may harbor an unsuspected wealth of knowledge. In some men.this feeling is disguised by bluster and a false front;

in others it fosters the ability to really listen to what the other fellow has to say not just outof courtesy

but from a belief that his knowledge may be of great value. Whether this is the way it happened with Kahn or not, no one can say, but by all accounts he had this quality

to a remarkable degree. It lay behind two of his most important future assets--his ability to form and lead a genuine team and his ability to respond sensitively to

his clients' needs. In fact this ability to listen coupled with a mental attitude free of preconceptions may have

been the cornerstone of his unique career."1 3

Albert Kahn's designs for the many enormous industrial projects express a remarkable concern for process

ef-ficiency. The planning of these buildings, was done by management and not by those involved in the production process.

The extreme rationalism of Taylor and the tendency to separate planning from production is a keen political issue. At its core is the assumed democratic capitalistic intent

increasing efficiency and productivity for profit. Any marked change in this basic goal would involve some

fundamental systemic changes. Most attempts to reorganize the workplace have been based upon the goal of increased productivity. All reforms have been based upon this intent. And newer theories of management have been

developed to this end. While these theories are based

upon the goal of increased productivity, this has not meant that all advocate increasing the skills and power of

managers at the expense of the workers. The emphasis remains, as it does in our society, upon the individual rather than the collective experience.

I once told an audience of school children that the world would never change if they did not contradict their elders. I was chagrined to find next morning that this axiom outraged their parents. Yet it is the basis

for the scientific method. A man must see, do and think things for himself, in the face of those who are sure

that they have already been over that ground . . .

In-dependence, originality and therefore dissent: these words show the progress, they stamp the character of our

civilization . . . dissent is also native in any society

which is still growing. Has there ever been a society which has died of dissent? Several have died of

con-formity in our lifetime.

J. Bronowski

Workplace Reforms

and

While legislation advocating workplace improvements for safety and health standards (OSHA codes) has been enacted, other workplace changes have come through the union and collective bargaining. Understandably, the

issues of comfort in the workplace are generally not viewed in physical architectural terms. Comfort and control are initially discussed in terms of hours worked, rate of work, amount of overtime and health/safety issues. "When the younger workers in some General Motors plants began to talk about humanizing the assembly lines, the greatest resistance did not come from GM management. It came from the United Auto Workers leadership, which insisted on talking about money, pensions, hours off, coffee

breaks--and so on." 1 4

In his wonderful book about working life, Ten Thousand Working Days, Robert Schrank has discussed this

hesita-tion on the part of unions and workers to consider more major changes to the workplace setting. He describes a

gathering of "seasoned automobile workers" of whom he asks the question: "If you had the option of running your plant in some way other than what is now being done, or in any way you thought would be better for the people working there, how would you do it?"15

Initially those who responded to this question pro-posed minor changes in the existing setup. "Clean the place up," "reduce noise levels," "improve the ventila-tion," and "get rid of all the foremen, or at least some

of them."1 6

Schrank recounts his initial dismay when they "only 17

came up with more collective bargaining demands." He then proceeds to toss out strategies of team work instead of an assembly line and the group's general response was

"The company knows more about this than we do and if this was a good way of doing things wouldn't they do it this way?" "This company is in business to make money not to

run Mickey Mouse programs."1 8

Schrank realizes how difficult it is for us all to grasp concepts of participation and collective work when so.much of our experience (and motivation) has been

directed by individual achievement. Going beyond the

limits of one's experience and traditions can be difficult. After some discussion the group "agreed that there were alternative ways to run a plant but that there would have to be a major learning of new, more cooperative

attitudes in order to really achieve a more human work-place."19 The "lack of knowledge is based on a lack of

experience with anything that is not hierarchical by organization," and Schrank suggests that managers, be-havioral scientists, owners and workers all know very

little" and "suffer from a collective ignorance when it comes to this form of social action."20

While this remains the case, there has been an in-creasingly prevalent movement away from the Tayloristic views of management. In 1960 while at the MIT Sloan

School, Douglas MacGregor analyzed managements' attitudes toward the workplace, and the subsequent approaches, which he called THEORY X and THEORY Y.

The Theory X attitude assumes that people are un-motivated and lazy, performing only in reaction to orders

or rules imposed from above. Theory X assumes that

people do not want an understanding of their work nor do they seek responsibility for the work. This theory re-flects basic Tayloristic notions of general low hierarchy worker attitudes.2 1

The Theory Y attitude on the other hand assumes that people are motivated, seek outlets for creative expression and take responsibility for their own work.

MacGregor's work in this area initiated a period of interest in the workplace by behavioral science. Most

behaviorists interested in workplace reforms have em-phasized the Theory approach and have sought for ways to encourage satisfaction among workers. According to

MacGregor, "Management has, due to codes, provided for the physiological and safety needs. Unless there are opportunities at work to satisfy (these) higher level needs, people will be deprived and their behavior will reflect this deprivation."2 2

Worker dissatisfaction had, in some large industries, led to periods of lower productivity, so management was also interested in exploring changes which might impact worker satisfaction, thereby increasing productivity. Many described many conditions necessary to a satisfying

working environment.

A behaviorist, Abraham Maslow, proposed that there is a hierarchy of needs and these influence behavior. He ranked them as follows:

1. Physiological (food/shelter) needs 2. Safety needs

3. Social needs 4. Ego needs

5. Self-fulfillment needs

According to Maslow satiation of one level of need will cause behavior to be determined by the next higher

level of needs.2 3

Allen Pincus has described four "Dimensions of the Institutional Environment" which form a good basis for analyzing an existing environment for designing for a new one. His work was done in institutions for the elderly, but the concepts may be applicable to an industrial

setting.

First, there is a distinction between "public" and "private." He discusses the importance of a place which individuals can use which is not open to public view or use. Second, there is the issue of a "structured" or an "1unstructured" environment. Are there strict rules to which individuals may adjust or is there room for choice and personal initiative.? Third, the environment may be "resource sparse" or "resource rich." It is important to consider the extent to which there exists a range of op-portunities and activities. And also the importance of. allowing for social interaction in various work and

recreational settings. Fourth, there is the important. consideration of the extent to which the institution is

"isolated" from or "integrated" with the community in

which it is located. To be integrated with a larger community there must be opportunities for interaction with a range of people and in a range of settings.2 4

It is true that those who work in factories are dif-ferent from those in old age institutions in that they are only in the job setting for part of each day. It

is true that many find satisfaction, privacy, an un-structured and resource rich environment integrated with

family and friends within their own homes and outside activities. These people have seen home as an escape

from work.

However it is also true that there are some persons who may view work as a place to escape from an unsatisfy-ing home life. When so much time is spent on the job it should never be assumed that satisfaction not present at work will be found elsewhere. It is, of course, desirable for satisfaction to spread to all facets of a person's life.

In an impressive article on industrial space,

Gustave Fischer and Abraham Moles have characterized such space as being of a higher intensity than other types of use spaces. "In general as industrial density increases, the ancillaries (canals, railroads, highways, power lines)

increase in density, changing the pattern of the land-scape, replacing it with a total industrial scene. This scene can be said to predominate once 30% of the space is

*25 actually occupied by industrial facilities.

Fisher and Moles argue that the sense of industry intensity tends to be overwhelming. "Because industry

imposes a temporal and spatial constraint on its employees,. people feel that there is antagonism between the factory itself and industrial space on the one hand and 'human spaces' on the other."2 6

Of course, there is the issue of scale of operation.

E. F. Schumacher discusses the fact that in a very

strictly organized, hierarchical company of a small size there may be a sense of belonging which belies the strict hierarchy.27 This gives us a clue that the physical en-vironment does have a role to play in workplace comfort. But it is essential to remember that an industrial setting may seem to many to be more overwhelming than any other setting of comparable size. This is not an argument in favor of making industrial spaces less industrial as if to make them more "human." This does argue for the existence of human scale forms and human intervention and participation within the rich and

sometimes overwhelming industrial setting. It is very important to remember that what seems overwhelming to

some, is not always overwhelming to those who are familiar with it, who use it, and who may have built it.

The ability to have privacy within a public setting is based upon an ability to make choices. "The degree to which the individual can lay claim to and secure an area or an object, he (she) maximizes his (her) freedom

128

of choice to perform any behavior." This ability to claim space or an object, according to Michael Brill, is socially (not physically) determined. Two things which contributed to a social setting conducive to claiming space are, the length of time in the space, and second, whether individuality is recognized and encouraged.2 9

While it may be true that the social setting must allow for this, there are obvious physical clues as to whether or not it is possible and encouraged.

. In an old mill or workshop there is often an accumula-tion of addiaccumula-tions to the physical setting which have oc-curred over time. Some of the life of such places has been described by John and Mart Myer who wrote of the qualities in such a workplace. It is "abuilt environment which has been generated incrementally and periodically, as needed,

through deploying the locally made piece of dimension

lumber, gives one the understanding of how it got generated and even the sense of being able to have generated it

oneself or with a small group of others. This mill which has been incrementally achieved, has no fixed limit in its growth. Not only can one sense how it was built but also that he (she) or others could readily extend it, a quality most of our modern plants lack. Like the form itself, which has no association to completeness but rather to incremental initiative, one is not blocked in physical built form. Rather the mill is open to such initiative and even suggestive of it." 30

As Michael Brill and the Myers have suggested, part of the important ability to affect one's environment comes from personal confidence, sense of mastery of skills,

and a sense of being part of an ongoing potential for changes.

Pyschologists like Abraham Maslow and Frederick Herzberg speak of the need for jobs to allow individual autonomy and creativity and make a job challenging. To Herzberg this does not mean asking an employee to do more of the same or rotate doing similar jobs, but means an increase in responsibility and a chance to grow.

Herzberg cites six principal ways to job enrichment and the potential results from their implementation. 1) Remove some controls (responsibility and personal achievement), 2) Increasing the accountability of in-dividuals for their own work (responsibility and recogni-tion), 3) Giving a person a complete unit of work,

rather than piecework (responsibility, achievement,

recognition), 4) Grant additional authority to plan job/ time (responsibility, and recognition), 5) Introduce new and more difficult tasks (growth and learning), 6) Assign-ing specialized tasks which allow them to become experts

(responsibility, growth, advancement). 31

This need for individual autonomy or creativity should not exist at the expense of the small working groups.

Participation must occur at the group level to avoid the competition when workers are forced by incentives to be better than others often at the expense of others.

Schrank discusses the importance of maintaining the com-munity spirit in participation, and suggests that some

industries are more conducive to participation and job enrichment than others. "At the point of production, decision making is at its lowest level since all design and manufacturing issues are settled long before they

reach that stage. To participate in decisions that affect the organization beyond the point of production requires a broad knowledge of the organization that most people

have no access to. . . . Most manufacturing plants do

not lend themselves to the democratic model of worker participation in decision making, particularly if the finished product has a large number of parts or

sub-assemblies (like the automobile) that require considerable overall planning. Participation is much more feasible

in continuous-process operations . . . which can be highly

automated, where the major work task is equipment adjust-ment and maintenance for product control. While the

area of decision making here too is limited, there is a much greater potential for decentralizing control than in unit manufacture." 3 2

Participation in decisions of organization or produc-tion harks back to the pre-Taylor periods when such deci-sions (made collectively) were common. To be successful there must be a real sense of community and solidarity. This enhances an important sense of security important to

the early stages of experimentation with this "new" participation.

(Of course participation when carried out to its

and even ownership amongst workers and managers. It

would be naive to think that at such a level of participa-tion there would be no risk, or that no security (owner-ship) could ever be assumed.)

But such conditions in large-scale American industry are not imminent. There have been many experiments with increasing paritcipation in the workplace. The initial experiments took place in Europe and in time some of the concepts have spread to American industry. In Europe

labor has been more involved in changing the organization. In the U.S., the changes toward increasing participation have been generated and supported by management who have viewed improvements in work environment as a means toward increasing productivity.

In some cases, changes have meant rearranging the work schedule. In the mid-1960s European companies began

instituting programs of "Gleitzeit" or "gliding time." In the early seventies the idea began to have an impact in the U.S. whe'e it was known as "flexi-time." Basically it allows employees to have some control over the schedul-ing of their work hours, givschedul-ing flexibility to people who want to avoid rush hours, be at home when their children

return home from school, etc. The response to this innova-tion has been tremendously positive, offering social benefit

to the workers and economic benefits to the company. "Some managements reported up to a 12 percent increase in productivity, overtime, and short-term absenteeism

dropped by nearly one-half. . . . Most people happily

trade stolen hours for the freedom to set their own

hours. The ubiquitous appeal of this tradeoff may have to do with intangibles like human dignity."3 3

Beyond the changes of schedules (flexitime) there have been larger changes in the industrial process itself which have affected the physical form of the factories. Generally innovations in workplace organization have oc-curred within the largest industries. First, because it is the largest industries where the effects of the dis-satisfaction (which leads to absenteeism, sabotage and

lower productivity) are on such a scale as to really

be felt. Second, any organizational changes involve some risk and outlay of capital for an uncertain return. This becomes a cash problem for smaller industries, who

indi-cate they cannot afford the time lost in reorganization. This is less often the case with larger industries.

The cost issues are a prominent feature at all levels of workplace design. The cost of new facilities when

calculated over time (the life of the building) is minimal, relative to the other costs of materials and salaries.

(One figure I heard somewhere was in the order of merely 2%-5%.) Changing facilities, process or organization may mean some cash problems but the long run benefits

may far outweigh the temporary inconveniences and costs. In the largest companies temporary losses may be absorbed elsewhere. In the smallest companies there may well be an intimacy of scale and existing participation based on the clear understanding of each individual's capabilities.

The move toward Theory Y attitudes in organizations has been called "Industrial Democracy" by some. Its basic premises are that workers can take over increasing responsibility for their work with fewer orders from above. "Management decides on production goals and the workers decide how to accomplish the work as a group. Incentive

is no longer based on piecework, but on the number of

operations a worker can perform and the quantity and quality of the group effort. The system is based upon the workers' control of themselves as a group."34

The experiments in industrial democracy were initiated in Norway and Sweden. Tardiness, absenteeism, turnover, sabotage, theft, deliberate waste and other disruptions

impacted productivity enough so that Volvo and Saab and other companies reevaluated their assembly line operations and turned increasingly toward teamwork organization.

(Richard E. Walton suggested in an article in the Harvard Business Review that "violence against persons and property

in industry occurs more often than we would think," but that the "private sector tends to keep it quiet.") 3 5

The new teamwork reflects a "desire for more equality which tends to enhance cohesiveness," and in varying

degrees it leans away from "differential rewards for in-dividual merit, which may be more equitable, but can be divisive."36 Though there are many differences between Scandinavian society and labor and American systems, worker dissatisfaction is common to both societies.

Similar experiments in "industrial democracy" have been initiated by management for some American industries.

One example is the Volvo U.S. car manufacturing plant in Norfolk, Virginia. The new plant was designed by

Mitchell/Giurgola Architects. Romaldo Giurgola de-scribed the design process as a uniquely collaborative effort among process engineers, management and the

architects. While the management was responsible for.the changes in the basic process, Giurgola felt that there was room for substantial input from the architect who worked more as an advocate for those who worked there. Giurgola's concerns were that production efficiency be 37 accommodated, but not at the expense of the workers.

The innovations at Volvo involved setting up

worker teams to assemble a single car. Within each team there will be job rotation so that each person had an opportunity to work on all phases of the car assembly and not simply repeat a single task. One "innovative technique"38 was a trolley-like vehicle which will guide automobiles through the assembly process without the restrictions of the traditional assembly line. "This trolley or carrier can pivot the car on its side to allow a worker easy access to the underbody."3 9

The size of production teams apparently determined the size of each "shop." Giurgola described that his experience with other institutions had led him to feel

that 100 to 150 persons was the maximum group size beyond which easy communication was not possible. He felt that his experience was considered in the establishment of

a group size of 130 workers per shop.4 0

Each team has their own production shop, lounge, locker rooms, courtyard and entrance. There were assump-tions made that had implicaassump-tions for the form and materials building: 1. That the entire assembly process be

"visible to team members affording them a comprehensive understanding of their role in the completion of the

car."

2. That locker and lounger areas be convenient to work areas yet separate and "identifiable" having a domestic scale "to act as a transitional link between the home and work environments." 3. That there be "awareness of nature and presence of natural light "to enhance the

quality of the space" and provide relief.from the intensity of the work experience."4 1

The building seems to articulate these intentions in its visible, human scale entrances and lounges, its natural light, outdoor and indoor views. Though the architecture successfully respects and enhances the new process, there may be problems with the process in the face of which the architecture may be irrelevant.

-One ironic problem is that the workers for whom these changes were made had little or no input into them.

"Though the workers at the Volvo truck plant thought team assembly was OK, they did not feel it was theirs, they did not own it. The Saab team assemblers said this is OK, it's a job, the company set it up this way so we

32 will do it."

There is a story of an American automobile worker's comments on the "innovative technique" at Volvo (by

which the chassis is rotated for working on the underbody, which was aimed at replacing the pit situation common

to the assembly line, where the worker works under the car from the pit.)

The American worker spoke of preferring the pit to the new system, saying: "When I'm in the pit I have a certain amount of control and privacy. Management says it will take me 50 seconds to complete my task. But

actually it takes me twenty seconds and then I have thirty seconds to rest. No one sees me resting because I'm

in the pit. If I was up on the ground working on the tilted chassis they would make me work faster."4 3

Richard Walton analzyed a new food processing plant and arrived at some other problems with the industrial democracy system as well as some benefits.

Major problems lie with lower level supervisors and managers who feel their authority is stripped away

as more control is allowed the workers, or that the changes "implies they have been doing their jobs poorly." Some workers resist the increased responsibility or are un-comfortable with the participation and group decisions. And interestingly enough, "outsiders" (salesmen, etc.) are uncomfortable dealing with workers as the company's representatives."

There have been many benefits reported in terms of increased satisfaction and a sense of involvement and

47-cooperation. "People will help you; even the operations manager will pitch in to help you clean up a mess--he doesn't act like he is better than youare." 4 6

There are indications that productivity rises enor-mously as the new system begins to run smoothly. Not only is productivity an important management goal (which may have initiated the changes initially), but it is easy to measure over time. Richard Walton correctly points out that "we do not have equally effective means for assessing the quality of work life or measuring the as-sociated psychological costs and gains for workers."4 7

It is clear that in order for changes to work there must be a real commitment to the changes in organization by all members of the workplace community including

workers and management. Commitment to the openness and flexibility needed for job enrichment can be enhanced by physical changes. But all the physical changes will have no impact unless the attitudes behind them are

supportive of the change. As we have discussed earlier, people can put up with some unpleasant working conditions

if there is a strong sense of community. And conversely, the cleanest, most beautiful elegant setting matters only as an image if there are rigid (Theory X) attitudes

Men feel lonely when they do not do the one thing they ought to do. It is only when we fully exercise our capacities--when we grow--that we have roots in the world and feel at home in it.

Eric Hoffer

Qualities Important to a

Good Workplace

If we assume that strong Theory Y attitudes exist in an industrial setting what physical (built) things can be done to support (or at least not to detract) from

these attitudes. To get at this we must. define that which is part of a positive workplace. At the most general

level we are concerned with allowing for flexibility,

an understanding of the whole integrated community (rather than promoting a hierarchy), providing for physical safety, creating a range of environmental conditions and allowing for the personalization of space.

Schrank has a lot to say about the.sense of community so important to every workplace. He says "it is hard

for me to recall a workplace where older men were not protected by the younger. This is one of those unwritten concerns of men and women for their fellows that tends to grow in work communities and can make tough workplaces

like coal mines, foundries and steel mills far more human than they might appear to the casual observer. This is one. reason why behavioral science studies of workplaces tend to be tales of horror. When people who work there read the studies, they might respond with "Oh hell, it ain't that bad."4 8

Schrank speaks of some of the jobs he had where the organization did not allow for the sense of belonging to

a community to happen easily. He speaks of being forced to be more creative in his work so that he could work

more efficiently so that he would have time for "schmoozing" --"time to wander around the plant, visit and talk with

people in other departments and not be stuck in one spot doing the same thing." 4 9

It is the daily contact and "rituals" beyond the work which nurtures a community feeling in a workplace.

Accord-ing to Schrank these "rituals" include: greetings on arrival, coffee breaks, lunch, smoke breaks, teasing, in-jokes, endless talk about almost everything."50 Community

feeling is also promoted by union activities where working places are organized.

There are many things which contribute to an inte-grated community and a sense of the workings of the whole organization. Sharing of facilities by managers and

workers is important. There should be no separate en-trances or "preferred" parking and other facilities for management. Lockers, cafeterias, bathrooms, meeting

rooms can be used by the entire community. It is often the case in a factory setting that some offices may need

to be physically separated so that noise and grime of the plant are not permitted to enter. But this separation does not mean that there cannot be windows and doors which make access between office and plant easier. (There may be a few cases when fire codes will make such difficult.) Those in the office need to be able to connect with the plant and vice versa. The offices need not be all above the plant looking down in a symbolic "guarding" way.

Those in the plant should be able to look into the office and see the workings. And finally there should be some means of looking out over the whole operation, a high point perhaps from which to view production.

Understanding the workings of the whole may also be articulated in the building massing. It can be clear from the outside where production occurs, where there are large, important, and relatively unchanging equipment, views of production, where there are entrances, places to relax and where there are offices.

Beyond promoting ritual contact within the workplace community, contact with the outside is also important. One important suggestion Schrank makes is that there be easy access to phones in a factory. Like a view from a high place, a phone call would be another (aural) "view"

of the outside, an important contact which may ease the strains of a working day. This is not to advocate endless phone conversations but the ability to make the contacts with other facets of one's life and community outside that helps nurture those ties. This seems especially important in our times when men and women leave their families to work.

There should be an important physical connection with the surrounding community. Beyond the articulation which gives one some indication of what goes on inside, the

building mass should reflect the scale of its surroundings as much as possible. Impact of the whole industrial

process must be considered early on when a site is being chosen. Disruptive activities must be minimized (i.e., transport of materials) or if they will have too great a negative impact, a new site must be found.

While there must be an attempt to reflect the scale of the existing context, it may well be true that an in-dustrial building may contain huge spaces for the process which are very different from most spaces in buildings of the private sector. Their great scale (high ceilings,

long walls) have a more "public building" character, and their different scale adds variety to the surrounding

This brings up the question of sharing some facil-ities with the surrounding community, and with the workers and their families. Could industry provide facilities for recreation and childcare for collective use and share existing community facilities? There could be tradeoffs. For example, could an industry provide childcare facilities to its workers and to the area and in return have use of the local recreation facilities? "In 1974 a law was passed in Sweden whereby all firms making over $22,000 in profits were to place 20% of those profits in tax-free building funds. These funds were administered by joint management-labor committees for any improvements desired--swimming pools,-sauna baths, furniture, sound insulation, etc."5 1

Fischer and Moles decribe and categorize types of interior industrial space: working places, raw materials storage, finished product storage, "buffer" spaces for

semi-finished items, space for trash, circulation spaces, administrative spaces and interstitial spaces.

The first seven are fairly straightforward use spaces and the proportions and amounts of each space will vary according to the prdduct and process of each specific industry.

The "interstitial space" category covers all uses that do not fit into the other use space categories.

"For the architect these may be wasted spaces, for the president, forgotten spaces, and for the worker, breath-ing spaces."52 These are the least understood spaces in the industrial environment and their existence runs

counter to the very rationalist approach to factory planning where economics and process efficiency rule. However a

study by Proshansky has shown that these are precisely the spaces used by people who work in the factory and that

53 planned spaces are used less at breaks, etc.

Schrank discusses the importance of the bathrooms for social interaction in many industrial settings. They are often the private place to which one can be away from, rules (and the eyes) of foremen, places to "schmooze"

(Schrank's word for the talking and socializing in the workpalce whether it is sanctioned or not).

"It can be said that depending on their position in the hierarchy, human beings resist to their utmost the rationalism that is forced on them by the factory. They invent their own freedom out of the workplace depending on how much time and space they may have access to and depending on who far they can move without special

justifications."54 This is not to say that all workers are unhappy. As Fischer and Moles correctly state, "many people are loyal to and have a genuine interest

55

in the company's success." The ability to claim territory enhances these feelings.

There should be a range of spaces which offer some refuge from the pace of the factory. There should be spaces where individuals can claim space on a relatively permanent basis. On the other hand there might be some places which can be used on a temporary basis by a person or persons to rest or share an intimate conversation.

What are some important physical qualities of such spaces? Julie Moir has defined "four archetypal contemplative spaces" where one can have some control, yet distance

from a fast pace environment:

The first is a "water place." Water in all forms, a still pool, a bubbling fountain, a view of ocean waves or the expanse of sea is very soothing. Moving water is especially calming.

The second is an "open place," a place one can look over preferably from a position where one has one's

back to a wall. One has a sense of intimacy and security against the wall with an expansive looking out feeling from the openness ahead.

The third is an "enclosed place," which is not neces-sarily dark or light but has a variety of sun and

shade.

A sense of inhabiting a place and individual control can exist if there is a place where there is some ability to shut a door, or control an entrance in some way.The fourth archetype is a "high space." There is the importance of a new view of the world and a detachment from the activity of the ground.

In these contemplative spaces individual use is pos-sible. It should not be so remote from others so as to feel unsafe, and there is the possibility that it can also be used collectively. Though publicly owned and maintained, they are places where individuals can go to rest and be

renewed. 56

Other places should be able to be made personal in a more permanent way. Though it does not mean that there should be fixed and solid walls, "a place is- created to

"157

the extent that it is surrounded by surfaces. Parti-tions of wood and soft materials which can be added to

or to which personal things can be attached. "Installation of personal objects, having a personal semantic signifi-cance, allows private meanings to be imposed on the work-place (or the refuge work-place)--within the rational space

of work . . . the very fact of filling space with objects

which are seen to be useful only by the occupant of the space is one of the main elements of 'nest-building,'

58 of creating a 'place' out of a location."

In the factories I have visited there has not been much evidence of individual place making--which may not mean that it does not occur but only fails to be obvious to an outsider. But in some of the older factories where there was wood framing or detailing, there was evidence that photographs and personal items were attached. In the newer factories the wider spans make the distance to the edge greater and the harder (more durable, cheaper)

"modern" materials (concrete, steel, plastic) make attach-ing thattach-ings more difficult. Some low temporary

parti-tions in some areas have helped. (Steel frames to which material or homosote, etc., can be attached.) Bring an

"edge" closer to each worker when it is possible. It is not just having personal-like objects in a factory setting. Things that are soft or in any way different from the working spaces are important as a contrast. Similarly any changes in light, noise levels, temperature or scale which vary from the working spaces are important. But control over them is as important

Personaliztion of working space is more possible when there are some individual controls of ventilation, noise, light and all other environmental factors. There should be light sources at each work area. These are more effective than an overall overhead system though some overhead systems will be needed to supplement the natural lighting, and the "local" lighting.

Where there are concrete floors there should be

movable wooden pallets which can be moved to any work area where long hours of standing would be uncomfortable on the hard concrete. End grain (wood) floors may be con-sidered, though they are not much softer than concrete. Low partitions can be used to provide some display

surfaces and/or privacies.

The issue of flexibility is one of the most important issues of the workplace environment. While it cannot

be ascertained that growth will occur, it is a fundamental goal of industry. While growth of the whole may not occur, changes within the industry certainly will. Market

pressures may cause an industry to shift its focus away from production, toward assembly of parts that can be produced more cheaply somewhere else. This will mean certain sections of the company will grow while others